Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Uveal schwannoma is a rare benign neoplastic proliferation of pure Schwann cells. The purpose of this study was to describe MR imaging features of uveal schwannoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: MR images in 6 female patients with uveal schwannoma confirmed by pathologic examination were retrospectively reviewed. MR imaging was performed in all 6 patients, with postcontrast T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) completed in all 6 patients and dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging, in 5. MR imaging findings of the tumor were evaluated with emphasis on the location, size, shape, margin, signal intensity, and pattern of enhancement.

RESULTS: The lesions appeared as solitary well-defined ovoid masses in the ciliochoroidal region in 5 patients and in the choroid in 1. With respect to the vitreous body, uveal schwannoma was hyperintense on T1WI spin-echo (SE) images in all 6 patients. The tumors were hypointense to the vitreous body on fast SE (FSE) T2-weighted images (T2WI) in 4 patients and isointense in 1. However, with respect to the brain, uveal schwannoma demonstrated isointensity on T1WI SE images in all 6 patients, isointensity on FSE T2WI images in 5 patients, and hyperintensity on T2WI SE images in 1. On postcontrast T1WI images, 3 patients showed markedly heterogeneous enhancement, and 3 showed markedly homogeneous enhancement.

CONCLUSIONS: Uveal schwannoma should be included in the differential diagnosis when an oval isointense mass relative to brain is seen in the ciliochoroidal region.

Schwannoma is a slowly growing solitary tumor that occurs sporadically and preferentially involves the head, neck, and extremities.1 Schwannomas also arise frequently in the orbit, where they account for approximately 0.5%–1% of orbital tumors.2,3 However, schwannoma of the uveal tract is a rarely encountered disease entity.4–16 In 2 large histopathologic studies that reviewed a total of 955 globes enucleated for uveal melanoma or pseudomelanoma, only 1 uveal schwannoma (0.1%) was found.17,18 Fewer than 20 cases with uveal schwannoma have been reported in the English literature.4–16

The clinical findings of the uveal schwannoma have been well documented in the literature.4–16 The tumor appears as a solitary amelanotic lesion usually of the ciliary body and/or choroid.4–16 The diagnosis of uveal tumor is usually possible by ophthalmoscopy, fluorescein angiography, or sonography and does not always require further imaging studies such as CT or MR imaging. The uveal schwannoma, nevertheless, is often misdiagnosed as a malignant melanoma, resulting in unnecessary enucleation in clinical practice, particularly when opaque medium or a vitreous hemorrhage precludes direct visualization of the lesion.4–16 The ophthalmoscopic, fluorescein angiographic, and ultrasonographic findings are not helpful in differentiating uveal schwannoma from uveal melanoma. Differential diagnosis of a uveal space-occupying lesions can be supported by MR imaging.19 Melanoma has short T1 and T2 values, a finding that has been attributed to paramagnetic proton relaxation by stable radicals in the melanin.19–21 Amelanotic melanoma does not show the shortened T1 values. However, most uveal schwannomas were misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma in the previously published literature.4–16 MR imaging findings of uveal schwannomas were mentioned in only a few case reports in the English literature, without a detailed description,6,9,10,15 and to our knowledge, systematic analysis of the imaging features of uveal schwannoma has seldom been reported in the radiologic literature. The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristic MR imaging findings of 6 cases with uveal schwannoma confirmed by pathology.

Materials and Methods

Between 1996 and 2008, review of medical records based on the electronic data base of our institution, approved by our institutional review board, revealed 6 patients with uveal schwannoma confirmed by pathologic examination. All 6 patients were women, ranging in age from 19 to 63 years (Table).

MR imaging findings in 6 patients with uveal schwannoma

| No./Age (yr)* | Location | Shape | Bulge of Globe Wall | Displacement of Lens and Iris | Size | Margin | Signal Intensity on MR Imaging |

Enhancement | Other Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative to Vitreus |

Relative to Brain |

|||||||||||

| T1WI | T2WI | T1WI | T2WI | |||||||||

| 1/37 | Right temporal ciliochoroidal region | Oval | No | Yes | 21 × 15 × 12 mm | Well-defined | Hyper, homo | Mixed hypo, iso | Iso, homo | Mixed iso, hyper | Hetero | RD |

| 2/19 | Left nasal ciliochoroidal region | Oval | Yes | Yes | 15 × 13 × 12 mm | Well-defined | Hyper, homo | Hypo, homo | Iso, homo | Iso, homo | Homo | |

| 3/22 | Right nasal ciliochoroidal region | Oval | Yes | Yes | 16 × 13 × 11 mm | Well-defined | Hyper, homo | Hypo, homo | Iso, homo | Iso, homo | Hetero | |

| 4/36 | Left temporal choroid | Oval | Yes | No | 13 × 10 × 9 mm | Well-defined | Hyper, homo | Mixed hypo, iso | Iso, homo | Mixed iso, hyper | Homo | RD, schwann of extremities |

| 5/38 | Right nasal ciliochoroidal region | Round | No | Yes | 10 × 10 × 10 mm | Well-defined | Hyper, homo | Mixed hypo, iso | Iso, homo | Mixed hyper, iso | Hetero | RD |

| 6/63 | Left inferior ciliary body | Oval | No | Yes | 8 × 6 × 6 mm | Well-defined | Hyper, homo | Hypo, homo | Iso, homo | Iso, homo | Homo | |

Note:—Hyper indicates hyperintense; hypo, hypointense; iso, isointense; homo, homogeneous; hetero, heterogeneous; RD, retinal detachment; schwann, schwannomas; T1WI, T1-weighted imaging; T2WI, T2-weighted imaging.

All female sex.

Four patients presented with visual loss, and 2 patients presented with slowly progressive blurred vision. Ophthalmoscopic examination revealed a solitary brownish mass of the ciliary body and/or choroid in 6 patients. One patient with uveal schwannoma was associated with multiple schwannomas of the extremities excised several years ago. The tumor could not be readily differentiated from malignant melanoma clinically, so it was treated with local resection in 5 patients, and 1 patient underwent enucleation.

In 5 patients, MR imaging with an 8-channel head coil was performed on a 1.5T Signa TwinSpeed scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wis), in which a 7.62-cm (3-inch) dual surface coil was used additionally in 2 patients. MR imaging with a head coil was completed on a 0.5T Flexart (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) scanner in 1 patient. Routine spin-echo (SE) T1-weighted images (T1WI) with imaging parameters of 600 ms/11.1 ms/2 (TR/TE/NEX), a section thickness of 3–4 mm, a matrix of 288 × 224 pixels, and an FOV of 180 × 180 mm (FOV of 100 × 100 mm with a surface coil) and fast SE (FSE) T2-weighted images (T2WI) with imaging parameters of 3000 ms/120 ms/3 (TR/TE/NEX), a section thickness of 3–4 mm, a matrix of 288 × 224 pixels, and an FOV of 180 × 180 mm (FOV of 100 × 100 mm with a surface coil) were acquired in the axial section. Additional T1WI and T2WI coronal and/or sagittal images were acquired with the same sequence. Images were obtained in at least 2 planes with 3- to 4-mm section thickness and 0.3- to 0.5-mm intersection gap.

The dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging (DCE-MR imaging) covering the whole tumor was performed in 5 patients with 12 consecutive scans at 12-second intervals (acquisition time of 13 seconds for every scan and an interval of 12 seconds between the 2 scans with 288-second acquisition time of the total DCE-MR imaging sequence) in the axial section with 3D fast-spoiled gradient-echo sequences on a 1.5T Signa TwinSpeed scanner. The imaging parameters were as follows: TR, 8.4 ms; TE, 4 ms; flip angle, 15°; 3.2-mm effective thickness; 220 × 220 mm FOV; and 256 × 160 matrix. Gadolinium-diethylene-triamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA, 0.2 mL/kg) was administered at a rate of 2.0 mL/s through a 21-gauge intravenous line with a power injector. The beginning of the first scanning was designated as time 0 while administration of Gd-DTPA was started simultaneously. After DCE-MR imaging, a Gd-enhanced T1WI with a frequency-selective fat-suppression technique was performed with the same parameters as the nonenhanced T1WI before administration of Gd-DTPA. Gd-enhanced T1WI without DCE-MR imaging was completed in only 1 of 6 patients on a 0.5T scanner.

MR imaging findings of the tumor were evaluated with emphasis on the location, size, shape, margin, signal intensity, and pattern of enhancement. The signal intensity of the tumor was evaluated compared with the vitreous body and brain, respectively. The signal intensity within the tumor was classified as homogeneous or inhomogeneous. DCE-MR imaging of the tumor was evaluated by using an AW 4.2 workstation (GE Healthcare). Data analysis of contrast enhancement on dynamic images was performed with a region-of-interest technique. A region of interest was drawn manually for signal-intensity measurement to avoid the vessels and cystic parts of the tumors and was approximately 3–4 mm in diameter in each case. The contrast index (CI) was calculated from the following: CI = [signal intensity (postcontrast) − signal intensity (precontrast)]/signal intensity (precontrast). The CI was plotted on a time course to obtain the CI curves.

The MR images were interpreted by 2 radiologists (J.X. and Z.W.) with >15 years in practice and >10 years in training head and neck imaging.

Results

The MR imaging features of 6 patients with uveal schwannoma are summarized in the Table. A solitary well-defined ovoid mass was observed in all patients with crescent-shaped retinal detachment found in 3 (Figs 1 and 2). The tumor was located in the nasal ciliochoroidal region in 3 patients, in the temporal ciliochoroidal region in 1, in the temporal choroid in 1, and in the inferior ciliary body in 1. Displacement of the lens and iris was seen in 5 patients. In no case was there a significant extraocular growth of the tumor, though bulge of the globe wall was observed on MR imaging in 3 patients (Fig 1). With respect to the vitreous body, uveal schwannoma was hyperintense on SE T1WI in all 6 patients, hypointense in 3 patients, and mixed hypointense and isointense in 3 on SE T2WI images (Figs 1 and 2). However, with respect to the brain, uveal schwannoma demonstrated isointensity on SE T1WI images in all 6 patients, isointensity in 3 patients, and mixed isointensity and hyperintensity in 3 on FSE T2WI (Figs 1 and 2).

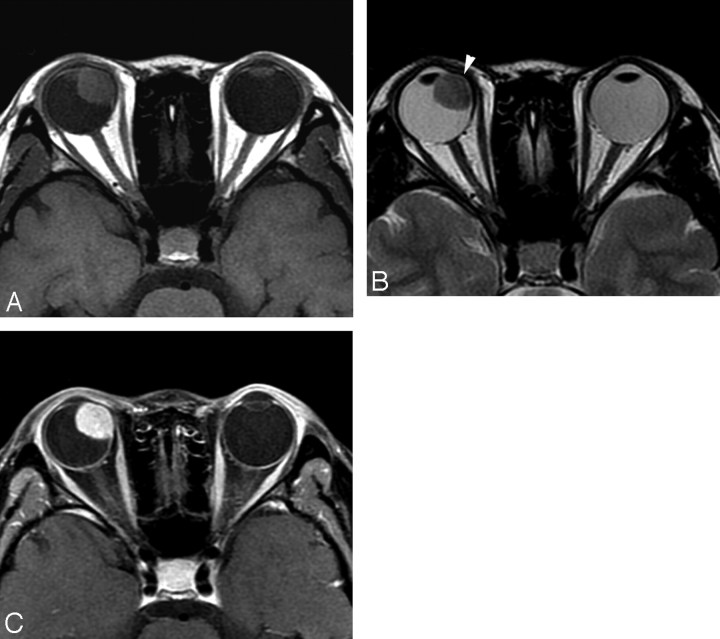

Fig 1.

Case 3. Schwannoma in the right nasal ciliochoroidal region in a 22-year-old woman. Compared with the brain, the tumor demonstrates isointensity on SE T1WI (A), isointensity on FSE T2WI (B), and markedly heterogeneous enhancement on postcontrast SE T1WI (C). Displacement of the right lens is seen.

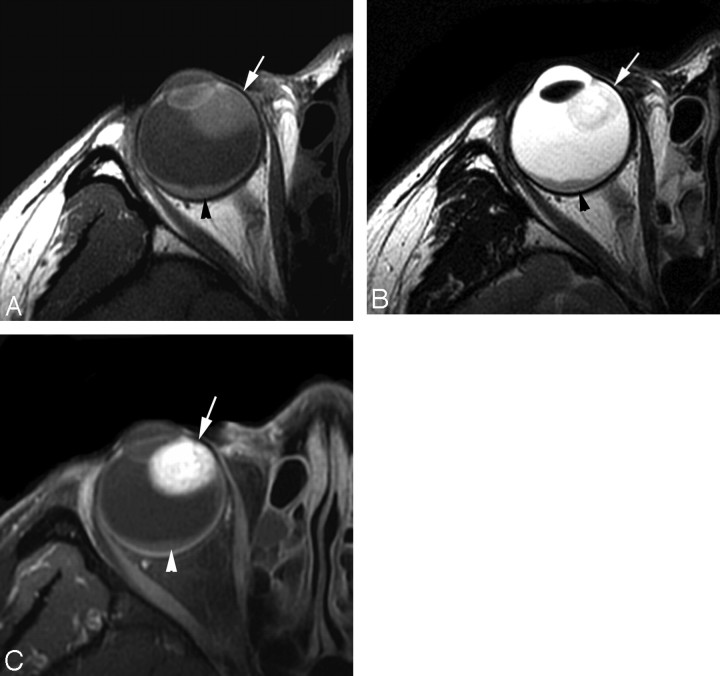

Fig 2.

Case 5. Schwannoma in the right nasal ciliochoroidal region in a 38-year-old woman. With respect to the brain, the tumor (arrow) shows isointensity on SE T1WI (A), mixed hyperintensity and isointensity on FSE T2WI (B), and markedly heterogeneous enhancement on postcontrast SE T1WI (C). Crescent-shaped retinal detachment (arrowhead) without enhancement after contrast administration is found.

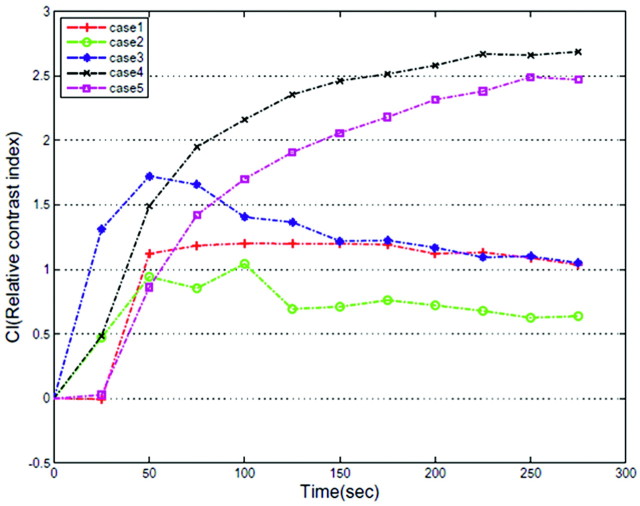

On postcontrast T1WI, 3 patients showed heterogeneous enhancement and 3 showed homogeneous enhancement. CI curves, which were calculated from a dynamic series, are shown in Fig 3. Two of 5 CI curves of uveal schwannoma increased gradually. One increased rapidly and decreased gradually. One increased rapidly, reached a plateau, sustained the plateau to 175 seconds, and decreased gradually. One increased gradually and then decreased gradually thereafter.

Fig 3.

Dynamic contrast-enhancement curve shows patterns of enhancement in 5 cases of uveal schwannoma.

Discussion

Schwannoma is a benign slowly growing neoplastic proliferation of pure Schwann cells, which occurs sporadically.1 The head, neck, extremities, spinal nerve roots, and sympathetic, cervical, and vagus nerves are most commonly affected by schwannoma.1 Smaller tumors do not cause pain or other neurologic symptoms. Approximately 10% of cases of schwannomas are associated with multisystem disorders such as neurofibromatosis,7,22 schwannomatosis,23 multiple meningiomas, and Carney complex.24 The hallmark of neurofibromatosis type 2 is vestibular schwannoma.25 Schwannomas arising in regions other than the internal auditory canal are rarely associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.23 Schwannomatosis manifesting as multiple schwannomas arising in regions other than the internal auditory canal is now considered to be a genetically distinct entity.23 The Carney complex is an association of melanotic schwannoma with myxomas spotty skin pigmentation and endocrine tumors, which is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait.24 In this study, only 1 of 6 patients with uveal schwannoma was associated with multiple schwannomas of the extremities excised several years ago, which suggested schwannoma in the choroid confirmed by pathology in this case.

Slowly progressive impairment of visual acuity caused by uveal schwannoma with tumor enlargement can be explained by displacement of the lens and progression of an anterior subcapsular cataract.15 Rapid visual loss may be due to retinal detachment secondary to uveal schwannoma.

Most interesting, the 6 patients in this study were women. However, uveal schwannoma can be seen in both men and women, with most patients being women in the published English literature.4–16

On gross examination, uveal schwannoma usually appears as an oval mass, whereas uveal melanoma typically shows a mushroom-shaped tumor due to the destruction of the Bruch membrane. Therefore, mushroom shape favors uveal melanoma, and oval shape favors uveal schwannoma. However, some uveal melanomas may appear as an oval mass,19–21 which may be similar to uveal schwannomas. In this circumstance, the shape of the tumor cannot distinguish uveal schwannoma from oval uveal melanoma.

The histologic diagnosis of schwannoma is usually straightforward.4–16 Uveal schwannoma is partially surrounded by a pseudocapsule and composed of spindle cells with rather small oval nuclei, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and small cytoplasmic extensions.4–16 The tumor is composed of some areas appearing solid with a densely packed fascicular arrangement of tumor cells (Antoni A pattern) and other areas with a loose myxoid arrangement of tumor cells and extracellular mucoid substances (Antoni B pattern).4–16 The tumor cells are uniform, and mitoses or nuclear anomalies were absent in our patients.

Most primary and metastatic ocular neoplasms involve the uvea.19 Malignant melanoma is the most common tumor to involve the uvea. Choroidal hemangioma, choroidal nevi, choroidal detachment, choroidal cysts, uveal neurofibroma, uveal schwannoma, uveal leiomyoma, ciliary body adenoma, medulloepithelioma, and metastatic tumors are some of the benign and malignant lesions.19 Although ophthalmologic examination is usually accurate in a diagnosis of uveal melanoma, clinical differentiation from uveal schwannoma may be difficult, especially in cases of amelanotic melanoma.19 When an opaque medium or a vitreous hemorrhage precludes direct visualization of the lesion, it is impossible to differentiate uveal schwannoma from malignant uveal melanoma and other lesions on clinical grounds.

The MR imaging appearance of uveal schwannoma was mentioned in only a few reports in the ophthalmologic literature, without a detailed description of MR imaging appearances.6,9,10,15 The published reports demonstrated a well-defined lesion giving a high signal intensity with respect to the vitreous body on SE T1WI and marked enhancement after contrast administration.6,9,10,15 To our knowledge, MR imaging appearances on SE T2WI were not reported in the literature. Our results showed that with respect to the vitreous body, uveal schwannoma was hyperintense on SE T1WI in all 6 patients and hypointense in 3 patients and mixed hypointense and isointense in 3 on SE T2WI. With respect to the brain, uveal schwannoma demonstrated isointensity on SE T1WI in all 6 patients, isointensity in 3, and mixed isointensity and hyperintensity in 3 on FSE T2WI. In the literature, MR imaging of uveal melanoma showed, in most, hyperintensity on SE T1WI and hypointensity on FSE T2WI with respect to the vitreous body.19

Unlike uveal schwannoma, uveal melanoma still demonstrated hyperintensity on SE T1WI and hypointensity on FSE T2WI with respect to the brain. On the basis of our experience, the difference in signal intensity with respect to the brain between uveal schwannoma and uveal melanoma might distinguish them. The brain as a reference of the signal intensity of the uveal tumor is better than the vitreous body or the orbital fat. Therefore, the difference in signal intensity of the tumor with respect to the brain may be the feature to differentiate uveal schwannoma from uveal melanoma. De Potter et al20 reported that, in a small fraction of patients (<5%) with uveal melanoma, the tumor appeared hypointense on SE T1WI and isointense on SE T2WI with respect to the vitreous body on the basis of a study of 43 patients. However, it is still impossible to differentiate uveal schwannoma from uveal amelanotic melanoma on the basis of the signal intensity of the tumor on MR imaging.

Uveal schwannoma usually affects the ciliary body and peripheral choroids rather than the posterior choroid. By contrast, uveal melanomas are less likely to occur in the peripheral choroid or ciliary body.19,20 In addition, extraocular growth detected by MR imaging is identified in 10%–15% of all cases of uveal melanoma,19,20 whereas extraocular growth of a uveal schwannoma should not be seen. These findings may be helpful in the differentiation of uveal schwannoma from uveal melanoma. However, a bulge of the ciliary body and/or choroid on MR imaging observed in 3 patients with uveal schwannoma in our study may be misdiagnosed as extraocular growth of the tumor.

The pattern of enhancement of uveal schwannoma was uncertain because of limited cases of uveal schwannoma. It needs to be further evaluated after collection of enhancement data from more patients with uveal schwannoma. To our knowledge, no data on the usual curves with melanoma were found in the literature.

MR imaging features of uveal schwannoma may contribute to the differentiation of uveal schwannoma from other benign and malignant uveal lesions. Choroidal hemangioma in a solitary circumscribed form is isointense or hyperintense on FSE T2WI relative to vitreous matter and is mainly located in the posterior choroids.26 Choroidal metastasis is usually seen with a disklike or “lentiform” shape in the choroid, posterior to the equator of the globe. A primary tumor is usually obvious.19 A uveal nevus is the most frequently seen in the posterior third of the choroid with a flat lesion; it is, for the most part, <5 mm in basal diameter.27 Choroidal osteoma appears as a platelike calcified thickening of the posterior choroid, typically in the juxtapapillary region, which can be readily depicted on CT.28 Nevertheless, other uveal tumors including leiomyoma, neurofibroma, medulloepithelioma, or even amelanotic melanoma cannot be differentiated from uveal schwannoma by either clinical or imaging examinations.

Conclusions

Uveal schwannoma tends to occur in the ciliochoroidal region and to appear as an oval isointense mass with respect to brain on T1WI and T2WI. Therefore, uveal schwannoma should be included in the differential diagnosis when an oval isointense mass relative to brain is seen in the ciliochoroidal region.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hugh Curtin for his advice in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Both Junfang Xian and Xiaolin Xu are first authors.

This work was supported in part by a grant (2004-B-31) from New Star of Beijing Science and Technology Committee, China, and grants (7062019, 7082026) from Beijing Nature and Science, China.

References

- 1.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, eds. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft-Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby;2003. :1171–73

- 2.Kennedy RE. An evaluation of 820 orbital cases. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1984;82:134–57 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergin DJ, Parmley V. Orbital neurilemoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106:414–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan BF. Neurilemoma of the ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol 1956;55:672–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosso R, Colombo R, Ricevuti G. Neurilemmoma of the ciliary body: report of a case. Br J Ophthalmol 1983;67:585–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith PA, Damato BE, Ko MK, et al. Anterior uveal neurilemmoma: a rare neoplasm simulating malignant melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1987;71:34–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman SF, Elner VM, Donev I, et al. Intraocular neurilemmoma arising from the posterior ciliary nerve in neurofibromatosis: pathologic findings. Ophthalmology 1988;95:1559–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Küchle M, Holbach L, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, et al. Schwannoma of the ciliary body treated by block excision. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:397–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan JT, Campbell RJ, Robertson DM. A survey of intraocular schwannoma with a case report. Can J Ophthalmol 1995;30:37–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pineda R 2nd, Urban RC Jr, Bellows AR, et al. Ciliary body neurilemoma: unusual clinical findings intimating the diagnosis. Ophthalmology 1995;102:918–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shields JA, Hamada A, Shields CL, et al. Ciliochoroidal nerve sheath tumor simulating a malignant melanoma. Retina 1997;17:459–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thaller VT, Perinti A, Perinti A. Benign schwannoma simulating a ciliary body melanoma. Eye 1998;12 (pt 1):158–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim IT, Chang SD. Ciliary body schwannoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1999;77:462–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Hong JS, Choi JH, et al. Choroidal schwannoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2005;83:754–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goto H, Mori H, Shirato S, et al. Ciliary body schwannoma successfully treated by local resection. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2006;50:543–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saavedra E, Singh AD, Sears JE, et al. Plexiform pigmented schwannoma of the uvea. Surv Ophthalmol 2006;51:162–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferry AP. Lesions mistaken for malignant melanoma of the posterior uvea. Arch Ophthalmol 1964;72:463–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shields JA. Lesions simulating malignant melanoma of the posterior uvea. Arch Ophthalmol 1973;89:466–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mafee MF. Uveal melanoma, choroidal hemangioma, and simulating lesions: role of MR imaging. Radiol Clin North Am 1998;36:1083–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Potter P, Flanders AE, Shields JA, et al. The role of fat-suppression technique and gadopentetate dimeglumine in magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of intraocular tumors and simulating lesions. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:340–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mafee MF, Peyman GA, Grisolano JE, et al. Malignant uveal melanoma and simulating lesions: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology 1986;160:773–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reith JD, Goldblum JR. Multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas: report of a case and review of the literature with particular reference to the association with types 1 and 2 neurofibromatosis and schwannomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996;120:399–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacCollin M, Willett C, Heinrich B, et al. Familial schwannomatosis: exclusion of the NF2 locus as the germline event. Neurology 2003;60:1968–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carney JA. Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma: a distinctive, heritable tumor with special associations, including cardiac myxoma and the Cushing syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:206–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans DG. Neurofibromatosis type 2: genetic and clinical features Ear Nose Throat J 1999;78:97–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stroszczynski C, Hosten N, Bornfeld N. Choroidal hemangioma: MR findings and differentiation from uveal melanoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:1441–47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mafee MF. The eye. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, eds. Head and Neck Imaging. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby;2003. :508

- 28.Bryan RN, Lewis RA, Miller SL. Choroidal osteoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1983;4:491–94 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]