Abstract

PURPOSE

This retrospective study sought to determine the type, burden, and pattern of cancer deaths in public hospitals in Tanzania from 2006 to 2015.

METHODS

This study analyzed data on cancer mortality in 39 hospitals in Tanzania. Data on the age and sex of the deceased and type of cancer were extracted from hospital death registers and report forms. Cancer types were grouped according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Age-standardized mortality rates and cancer mortality patterns were analyzed. A χ2 test was used to examine the association between common cancers and selected covariates.

RESULTS

A total of 12,621 cancer-related deaths occurred during the 10-year period, which translates to an age-standardized hospital-based mortality rate of 47.8 per 100,000 population. Overall, the number of deaths was notably higher (56.5%) among individuals in the 15- to 59-year-old age category and disproportionately higher among females than males (P = .0017). Cancers of the cervix, esophagus, and liver were the 3 major causes of death across all study hospitals in Tanzania. Cancers of the cervix, esophagus, and liver were the largest contributors to mortality burden among females. Among males, cancers of the esophagus, liver, and prostate were the leading cause of mortality.

CONCLUSION

There is an increasing trend in cancer mortality over recent years in Tanzania, which differs with respect to age, sex, and geographic zones. These findings provide a basis for additional studies to ascertain incidence rates and survival probabilities, and highlight the need to strengthen awareness campaigns for early detection, access to care, and improved diagnostic capabilities.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer has become a major and increasing global public health problem in recent years. An estimated 14.1 million new patients were diagnosed with cancer and 8.2 million cancer deaths occurred in 2012 worldwide.1 In 2015, cancer was the second leading cause of mortality worldwide, claiming about 8.8 million lives.2 The majority (70%) of these deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with Africa disproportionately burdened.3 Although statistics indicate that mortality rates from cancers are declining in many high-income countries (HICs), they are increasing in LMICs.4 Available statistics predict that the burden of cancer is expected to increase to more than 22 million new patients each year, and 13 million cancer deaths are expected globally by 2030.1 The trend has been attributed to a rapid change in lifestyle, behavioral patterns, and geographic and environmental risk factors, as well as a high burden of infection-related cancers.4,5

Cancer is an emerging public health threat in LMICs and has received low priority for health care services. This is because in most LMICs, there is inadequate and reliable data on the burden of cancer. For instance, by 2015, only 1 in 5 LMICs had the necessary data to drive cancer policy.6 The challenge is exacerbated by the overwhelming burden of communicable diseases, a shortage of both oncologists and facilities with capacity for cancer care, and management.7 Despite the recognition of cancer as a serious public health challenge, data on cancer mortality in sub-Saharan countries are particularly scarce. Only about 10.5% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa is covered by population-based cancer registries.8 Although some data from cancer registries in sub-Saharan Africa have been published, only 11 registries met high standards and were included in the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Volume XI report of 2017.9 In place of no valid alternative source of information, registries and other sources of death registrations are likely to provide valuable data on the epidemiology of cancer and, hence, evidence for planning cancer control strategies.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To determine the type, patterns, and trends of cancer mortality in Tanzanian hospitals, 2006-2015.

Knowledge Generated

Cancer deaths account for 5.1% of all in-hospital deaths in Tanzania during 2006-2015. An age-standardized hospital-based mortality rate due to cancer was 47.8 per 100,000 populations. Total number of deaths was notably higher among individuals in the 15-59 years age category. Cancers of the cervix, esophagus, and liver were the three major causes of deaths across all study hospitals in Tanzania. Significant regional variations were observed in the mortality rate of cancer in Tanzania.

Relevance

In limited resources countries, hospital-based records could be an alternative means to identify priority cancers upon which awareness campaigns for early detection and access to care could be based.

Studies on cancer mortality are few in Tanzania. A recent facility-based study indicated that cancers rank as the seventh overall leading cause of death in Tanzanian hospitals.10 However, a recent population-based study in northeastern Tanzania listed cancers as the third leading cause of death among individuals 15-59 years of age.11 In Tanzania, most reviews of cancer mortality are largely based on study of a single cancer, rather than the relative contributions of the various cancers to the overall burden of cancer mortality.12-14 This could be because of the nonfunctioning of both population-based and hospital-based cancer registries. Hospital-based data constitute an indispensable source of information on cancer patterns where incidence and mortality data are unavailable. This retrospective study was therefore performed to determine the type, patterns, and trends of cancer death in Tanzanian hospitals during the 10-year period from 2006 to 2015 (Data Supplement).

METHODS

Study Sites and Design

This retrospective study was performed from July to December 2016 and involved 39 hospitals in Tanzania. The hospitals included 1 national hospital (Muhimbili), 3 zonal referral hospitals (Bugando Medical Centre, Mbeya Referral Hospital, and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre), 4 special hospitals (Muhimbili Orthopedic Institute, Ocean Road Cancer Institute, Mirembe Mental Hospital, and Kibong’oto Infectious Disease Hospital), and 20 regional referral hospitals (Temeke, Kagera, Kitete [Tabora], Morogoro, Maweni [Kigoma], Dodoma, Bombo-Tanga, Mara, Mount Meru-Arusha, Shinyanga, Manyara, Ruvuma, Singida, Geita, Ligula-Mtwara, Tumbi-Pwani, Rukwa, Iringa, Sokoine-Lindi, and Njombe) and 11 district hospitals (Sengerema, Ukerewe, Mpanda, Kyela, Chunya, Biharamulo, Nzega, Kilosa, Kibondo, Lushoto, and Maswa).

National, zonal referral and special hospitals were included conveniently. To select sites from regions and districts, a multistage sampling technique with a set of guiding inclusion criteria was used. All regions were included to ensure that geographic representation was captured. Epidemiologic profile of diseases with high morbidity and main causes of death and ecologic, population, human resources coverage, and other spatial variations were considered to decide on the number of hospitals to be included within regions to obtain a national representative sample. In regions or districts where zonal referral hospitals were located, the respective region/district hospitals were not included.

Data Collection

Data were collected using customized paper-based collection tools. The research team and data collectors were trained on the use of data collection tools, how to review hospital registers and reporting forms, types of data required, and the data extraction process. Data collected included the name and level of the hospital and the deceased’s age, sex, and underlying cause and date of death. Sources of data included death registers, inpatient registers, and International Classification of Diseases (10th revision; ICD-10) report forms.

A thorough search, guided by hospital staff, of the tools (registers, forms) used to record mortality data was conducted in all hospitals. The extraction process started with the source having the largest number of records, based on discussion with the key members of the hospital management team and a review of what had been compiled. A checklist was created to mark data completeness status for each source. The next source was then used to fill time periods where no data were found from the previous one. This iterative process was performed until all identified sources were fully assessed and reviewed.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into a database developed in EpiData software version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense M, Denmark). A quality check was performed by taking a proportion of entered data and comparing it with original data. This was done for 1% of the data, then increased to 2% up to 3%, where necessary. After entry, all data were migrated to STATA version 13 (STATA, College Station, TX) for additional processing and analysis. Data for this study comprise a subset of deaths where the underlying cause of death was recorded as cancer of any type. Tanzanian population data for the year 2012, stratified by 5-year intervals, and sex were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics database.15 Age-standardized rates were calculated according to the global standard population.16 Descriptive statistics were obtained by summarizing continuous variables into mean and standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were analyzed by proportions and graphic presentations. Analysis was performed for the top 17 most common cancers in Tanzanian hospitals. The χ2 test was applied to determine associations and was considered significant when the P value was less than .05.

Cancer types were grouped according to ICD-10: esophagus (C15), stomach (C16), colon and rectum (including anus; C18-21), liver (C22), pancreas (C25), lung (including trachea; C33-34), Kaposi sarcoma (C46), female breast (C50), cervix uteri (C53), ovary (C56), prostate (C61), kidney (including renal pelvis and ureter; C64-66), bladder (C67), brain and CNS (C70-72), Hodgkin lymphoma (C81), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (C82-85, C96), leukemia (C91-95), and all cancers combined.

Ethics

This study received ethical approval from the Medical Research Coordinating Committee of the National Institute for Medical Research (Ref. No. NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/2230). Permission to access hospital registers and reporting documents was sought from the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children and the respective Regional Administrative Secretaries and Hospital Authorities. No informed consent was required in view of the retrospective nature of this study.

RESULTS

A total of 247,976 deaths were reported in 39 hospitals during the 2006-2015 period. Of these, 12,621 (5.1%) were due to cancers. Cancer was the sixth leading cause of hospital deaths. The male-to-female ratio was 1:1.03. The median age at death due to cancer was 53 (interquartile range [IQR], 35-68) years for males and 50 (IQR, 36-62) years for females. Irrespective of sex, mortality was notably higher in the middle-age category (15-59 years) than among children (< 15 years) and older individuals (≥ 60 years). The burden of cancer varied considerably across the country. However, the eastern zone accounted for about two thirds (65.7%) of the total cancer-related mortality. The lowest mortality was reported in the southern zone (0.9%; Table 1). The age-standardized hospital-based mortality rate was 47.8 cancer-associated deaths per 100,000 population over the 10-year period. In terms of type, cervical, esophageal, and liver cancers were among the top 3 causes of deaths in Tanzania (Fig 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Individuals Who Died as a Result of Cancer in Tanzanian Hospitals, 2006-2015

FIG 1.

Age-standardized mortality rates.

Cancers of the cervix, esophagus, and liver were the largest contributors to the cancer-associated mortality burden among females. Esophageal, liver, and prostate cancers were the leading cause of mortality among males (Table 2). The profile of cancer also differed by geographic zones of the country. Cancer of the liver, esophagus, cervix, and prostate were the most common and largest contributors to cancer mortality in all zones. However, the northern zone accounted for a significant share of cervical cancer (26.1%), followed closely by the southern highlands (24%). The Lake Victoria zone presented a unique pattern of cancer, with cancer of the liver accounting for the largest proportion (13.7%) of deaths and lymphoma being among the top 5 cancers. Most of the deaths due to Kaposi sarcomas were reported in the southern highlands (14.8%) and southwest (12.8%) zones (Fig 2). Deaths due to lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, leukemia, and cancer of the esophagus, liver, bladder, brain, and trachea/lungs were more common among males than females (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Types of Cancer Causing Death Coded Using ICD-10 by Sex in Tanzanian Hospitals, 2006-2015

FIG 2.

Cancer rates according to region.

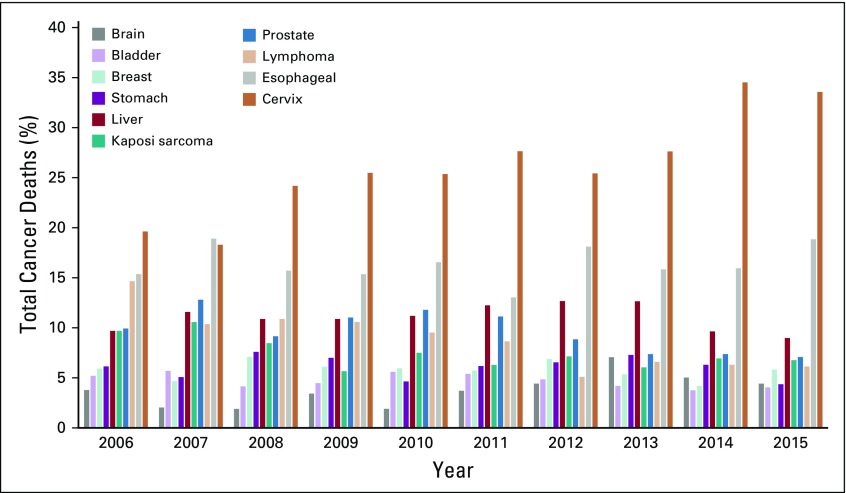

When age was categorized into 5-year age groups, the cancer profile varied considerably among age brackets (Fig 3). Lymphoma resulted in the death of more young adults younger than 29 years of age. Deaths due to cancer of the brain and stomach were also common in this age group. The spectrum of cancers commonly seen among children and adolescents changed as age increased. Deaths due to cancer of the prostate gland, bladder, esophagus, and cervix were the most common in the adulthood. Deaths due to prostate cancer markedly increased from the age of 55 years and older. Kaposi sarcoma accounted for the most deaths that affected patients in the 25- to 44-year-old age group, which gradually decreased with increasing age. A significant increase in age-standardized mortality rate was observed for cancer of the cervix and esophagus. Other cancer types showed only a slight change over the 10-year period. The death patterns for some cancers remained stable over the period of 10 years. However, there was an increasing trend in deaths due to cancer of the cervix, more markedly from 2013 (Fig 4).

FIG 3.

Percentage of cancer deaths by cancer type and stratified by age.

FIG 4.

Percentage of total cancer deaths by year.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate a significant heterogeneity in cancer mortality rates with regard to age, sex, and geographic distribution in Tanzania. Overall, cancers accounted for about 5% of all deaths that occurred in hospitals during the 10-year period. Similar findings have been reported from studies in Nigeria17 and Ghana.18 The cancer death rate in this study reflects only those deaths that occurred in hospitals, but was, however, much lower than the worldwide cancer mortality rate of 12%.19 The average age at death among males was slightly older (50.5 years) than that of females (48.3 years). Significantly, more females than males died of cancer, and the majority of deaths in this study were observed in the 15- to 59-year-old age category.

Generally, the age-standardized hospital-based mortality rate was 47.8 per 100,000 population over a 10-year period. This rate is lower than that previously reported for Eastern Africa (106.5), Northern Africa (86.8), Central Africa (81.2), Southern Africa (112.5), and West Africa (71.6).2 Estimating cancer mortality that occurred in the hospital setting in the current study is likely to have resulted in the observed lower rate because some patients could have died at home or been misdiagnosed. Like elsewhere in the world, lymphoma resulted in the death of more young adults younger than 29 years of age than in other age groups. In general, the incidence of lymphoma is low in Africa, with the exception of some East African countries, because of the high incidence of Burkitt’s lymphoma among children.20 The fact that deaths due to cancer were concentrated more among young adults could indicate either the age profile of the Tanzanian population or the actual differences in mortality rates, which calls for immediate and appropriate actions. There is therefore need to strengthen awareness, diagnostic capacities, and early treatment of cancers to prevent these premature deaths. The fact that cancers in the current study were responsible for the deaths of more females than males has also been reported recently.21 The reason for this female preponderance is probably due to the high prevalence and mortality of cervical cancer among women.19

Among males and females combined, the major contributor to cancer mortality was cancer of the cervix, esophagus, liver, prostate, and breast, as well as Kaposi sarcoma and lymphomas. When sex was considered, cancer of the cervix, esophagus, and liver contributed to more deaths among females, whereas males died more often as a result of prostate, esophagus, and liver cancers. Similar cancer profiles have been reported in other LMICs. A study in China revealed cancer of the lung, stomach, esophagus, and liver as the leading causes of mortality.22 In a study in Ghana, the most frequent causes of cancer death among females were malignancies of the breast, hematopoietic organs, liver, and cervix.18

In terms of types, cervical, esophageal, and liver cancers were among the top 5 cancer causes of death across all zones in Tanzania. Cancers of the bladder, brain, trachea/lungs, lymphoma, and leukemia were more common among males than females. Globally, lung and breast cancer are the most frequently diagnosed cancers and the leading causes of cancer death in men and women, respectively, both overall and in low-income countries.2 In HICs, however, prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among men, whereas lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among women.2 As in our study, other frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide include those of the liver, stomach, and colorectum among males and those of the stomach, cervix uteri, and colorectum among females.19,23 In another recent study in Tanzania, colorectal cancer incidence was reported to have increased 6 times during the past decade, affecting mainly the Dar es Salaam, Pwani, Kilimanjaro, Arusha, and Morogoro regions. The study indicated that diet, obesity, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and sedentary behavior play potential roles in the rising trend of colorectal cancer in the country.23 In the current study, cancer of the esophagus was the leading cause of death among men. Although breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths among females worldwide, it only accounted for 7.8% of all deaths due to cancer in this study. The global variation in breast cancer incidence rates reflects differences in the availability of early detection as well as risk factors.

Deaths due to cancer of the esophagus and stomach in our study were relatively higher among males than females. In low-income countries, liver and stomach cancer among men are the second and third most frequently diagnosed cancers, respectively, and leading causes of cancer death.3 Globally, liver cancer in men is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second most frequent cause of cancer death.5 Previous studies have reported a high prevalence of stomach cancer in areas of volcanic mountains in East Africa, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania.24 Generally, stomach cancer rates worldwide are about twice as high in males than in females.5 The differences in dietary patterns and alcohol and smoking habits are possible attributes. Alcohol and cigarette smoking were reported to increase the odds of developing gastric cancer in a study in Zambia.25 Patients with cancer of the esophagus were found to be common in 2 hospitals in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.12 Studies in Eastern Africa have reported a high incidence of esophageal cancers, and HIV/AIDS has been described to be an important comorbidity in these populations.23

In a study in Uganda, the most common cancers among males were prostate cancer and Kaposi sarcoma.15 Similarly, the most frequent cancer among females was cancer of the cervix uteri. Likewise, in an 18-year study in Mozambique, the most common cancers were prostate cancer, Kaposi sarcoma, and liver cancer.26 Interestingly, cervical cancer is not only the leading cause of death among females nationwide but it has shown a remarkable increasing trend. Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women worldwide and is the major cause of mortality.27 The cancer is strongly linked to human papillomavirus (HPV).28,29 Global statistics estimate a cervical cancer mortality rate of 37.5 per 100,000 women in Tanzania, which is the highest in East Africa.19 Given the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS among women, screening programs for HPV and cervical cancer among patients with HIV/AIDS need to be strengthened.

Significant regional variations were observed in the mortality rate of cancer in this study. It has been stated that geographic disparity in cancer incidence primarily reflects differences in cancer profiles and/or the availability of treatment. The largest proportion of cancer death reported from the eastern zone is likely to have been attributed to the location of the Ocean Road Cancer Institute in Dar es Salaam, reflecting accessibility. However, the epidemiologic profile of Tanzania is likely to explain the higher rates of lymphoma, bladder cancer, and Kaposi sarcoma in different areas of the country. Bladder cancer deaths were common in the western, central, and southern zones of Tanzania. In a study on urinary bladder cancer in the Lake Victoria area, about 45% of the cancers were associated with schistosomiasis.30 In our study, higher proportions of death associated with Kaposi sarcoma were observed in the southern highlands and southwestern highlands. These regions are characterized by a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS far above the national average.30 The association of Kaposi sarcoma with HIV/AIDS in Tanzania has been established in previous studies.31 The variations in mortality patterns between regions are likely to reflect differences in the prevalence and distribution of the major risk factors, detection practices, and/or the availability and use of treatment services.5

In conclusion, cervix, esophagus, liver, and prostate cancer were the largest contributors to mortality in hospitals in Tanzania. When assessed with geographic distribution, cancer of the liver, esophagus, cervix, and prostate were the most common in all zones, with the northern zone accounting for a significant share of cervical cancer. A growing trend in cancer mortality has been shown in Tanzania, which also differs with respect to geographic zones, sex, and age categories. These variations in common cancers provide a basis for additional studies to ascertain cancer incidence rates and survival probabilities. The patterns observed from this study highlight the types of cancer and cancer mortality patterns in Tanzania. The findings also call for the need to support an awareness campaign for early detection, access to care, and improved diagnostic capabilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the assistance of Avit Kapinga, Nicholaus Lubange, Amani Wilfred, Maua Kikari, David Kiwera, Emiliana Ekon, Leilath Mtui, Joyce William, Mseya Mbeye, John Ng’imba, Neema Lauwo, Dickson Bigundu, Jesca Massawe, Paulo Lutobeka, Emmanuel Chagoha, Osyth Massawe, Tumaniel Macha, Khadija Kigoto, Lydia Mwaga, Mercy Mmanyi, Alfred Chibwae, Togolai Mbilu, Enock Anderson, and Kisaka Mhando for transcribing data from source documents to paper-based questionnaires. We thank Fagason Mduma, Marco Komba, Rodger Msangi, and Jackline Mbishi for excellent data entry. We also thank all Medical Officers In-Charge, Hospital Directors, and Regional and District Administrative Secretaries for permission to access and extract the mortality data from their respective hospitals.

SUPPORT

Supported by the Global Funds for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria through the Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Susan F. Rumisha, Leonard E.G. Mboera

Administrative support: Susan F. Rumisha, Mercy G. Chiduo

Provision of study materials or patients: Irene R. Mremi, Lucas E. Matemba

Collection and assembly of data: Susan F. Rumisha, Irene R. Mremi, Chacha D. Mangu, Coleman Kishamawe, Mercy G. Chiduo, Lucas E. Matemba, Veneranda M. Bwana, Isolide S. Massawe, Leonard E.G. Mboera

Data analysis and interpretation: Emanuel P. Lyimo, Susan F. Rumisha, Irene R. Mremi, Coleman Kishamawe, Mercy G. Chiduo, Lucas E. Matemba, Leonard E.G. Mboera

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . Cancer fact sheets. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2016. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busolo DS, Woodgate RL. Cancer prevention in Africa: A review of the literature. Glob Health Promot Educ. 2015;22:31–39. doi: 10.1177/1757975914537094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, et al. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends—An update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.2015. Fray F, Znaor A, Cueva P, et al: Planning and Developing Population-Based Cancer Registration in Low- and Middle-Income Settings: IARC Technical Publication 43. Lyon, France, IARC.

- 7.Rubagumya F, Greenberg L, Manirakiza A, et al. Increasing global access to cancer care: Models of care with non-oncologists as primary providers. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1000–1002. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30519-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gakunga R, Parkin DM. Cancer registries in Africa 2014: A survey of operational features and uses in cancer control planning. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:2045–2052. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bray F, Colombet M, Mery L, et al: Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. XI: IARC CancerBase No. 14. Lyon, France, IARC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mboera LEG, Rumisha SF, Lyimo EP, et al. Cause-specific mortality patterns among hospital deaths in Tanzania, 2006-2015. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0205833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Challe DP, Kamugisha ML, Mmbando BP, et al. Pattern of all-causes and cause-specific mortality in an area with progressively declining malaria burden in Korogwe district, north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2018;17:97. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2240-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mmbaga E, Deardorrf K, Mushi B, et al. A case-control study to evaluate the etiology of esophageal cancer in Tanzania. J Glob Oncol. 2016;2(suppl; abstr 75) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burson AM, Soliman AS, Ngoma TA, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic profile of breast cancer in Tanzania. Breast Dis. 2010;31:33–41. doi: 10.3233/BD-2009-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalya PL, Simbila S, Rambau PF. Ten-year experience with testicular cancer at a tertiary care hospital in a resource-limited setting: A single centre experience in Tanzania. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:356. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. United Republic of Tanzania, National Bureau of Statistics: 2012 Population and Housing Census. http://www.tzdpg.or.tz/fileadmin/documents/dpg_internal/dpg_working_groups_clusters/cluster_2/water/WSDP/Background_information/2012_Census_General_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Institutes of Health: World (WHO 2000-2025) standard. https://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/world.who.html.

- 17. Akinde OR, Phillips AA, Oguntunde OA, et al: Cancer mortality pattern in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. J Cancer Epidemiol . , 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiredu EK, Armah HB. Cancer mortality patterns in Ghana: A 10-year review of autopsies and hospital mortality. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferlay J, Shin H, Bray F, et al: Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. IARC Cancer Base 2008. https://www.iarc.fr/news-events/globocan-2008-cancer-incidence-and-mortality-worldwide.

- 20.Walusansa V, Okuku F, Orem J. Burkitt lymphoma in Uganda, the legacy of Denis Burkitt and an update on the disease status. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:757–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20-39 years worldwide in 2012: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Deng Y, Tang W, et al. Urban-rural disparity in cancer incidence, mortality, and survivals in Shanghai, China, during 2002 and 2015. Front Oncol. 2018;8:579. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katalambula L, Petrucka P, Buza J, et al. Colorectal cancer epidemiology in Tanzania: Patterns in relation to dietary and lifestyle factors. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4(suppl 2) [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cook P, Burkitt DP: An epidemiological study of seven malignant tumours in East Africa. Cyclostyled booklet. Medical Research Council, 1970.

- 25.Kayamba V, Asombang AW, Mudenda V, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma in Zambia: A case-control study of HIV, lifestyle risk factors, and biomarkers of pathogenesis. S Afr Med J. 2013;103:255–259. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.6159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenzoni C, Vilajeliu A, Carrilho C, et al. Trends in cancer incidence in Maputo, Mozambique, 1991-2008. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng ML, Zhang L, Borok M, et al. The incidence of oesophageal cancer in Eastern Africa: Identification of a new geographic hot spot? Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:1–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rambau PF, Chalya PL, Jackson K. Schistosomiasis and urinary bladder cancer in North Western Tanzania: A retrospective review of 185 patients. Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.THMIS : Tanzania HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey 2011-12. TACAIDS, ZAC, NBS, OCGS and ICF International, March 2013. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AIS11/AIS11.pdf

- 31.Koski L, Ngoma T, Mwaiselage J, et al. Changes in the pattern of Kaposi’s sarcoma at Ocean Road Cancer Institute in Tanzania (2006-2011) Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26:470–478. doi: 10.1177/0956462414544724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]