Abstract

The U.S. government funds integrated care demonstration projects to decrease health disparities for individuals with serious mental illness. Drawing on the Exploration Preparation Implementation Sustainability (EPIS) implementation framework, this case study of a community mental health clinic describes implementation barriers and sustainability challenges with grant-funded integrated care. Findings demonstrate that integrated care practices evolve during implementation and the following factors influenced sustainability: workforce rigidity, intervention clarity, policy and funding congruence between the agency and state/federal regulations, on-going support and training in practice application, and professional institutions. Implementation strategies for primary care integration within CMHCs include creating a flexible workforce, shared definition of integrated care, policy and funding congruence, and on-going support and training.

Keywords: Integrated Care, Community Mental Health, Case Study, Sustainability

Introduction

Adults with serious mental illness have inadequate access to primary care services1 and die, on average, from treatable health conditions 25 years earlier than those without such illness.2 For example, even though adults with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have higher rates of chronic health conditions, such as diabetes and respiratory disease,2–3 the literature demonstrates that they have less access to preventative primary care services.3 Integrated care is an approach that aims to tear down silos between physical health, mental health and substance abuse treatment providers through communication, collaboration, quality measurement and improvement strategies, health information technology, and patient-centered care.4 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)5 promotes integrated care through funding initiatives through multiple federal departments, including the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). Although grant-funded integrated care initiatives are subject to evaluation during the funding period, the long-term efficacy of programs are yet unknown.

While the integrated care research and practice literature typically describe adding behavioral health services to primary care clinics,6–7 there is growing support for adding primary care providers to specialty behavioral health clinics serving individuals with serious mental illness.8–9 Studies focusing on primary care integration with behavioral health care have demonstrated promising results from adding specific care components, like nursing care management, within outpatient mental health services.9–10 However, these studies do not discuss the agency-wide practice changes required to implement and sustain primary care integrated practice within community mental health clinics (CMHCs).8–10

To advance the implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) within the public service sector, Aarons et al.11 created the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework. The EPIS framework provides a structure that CMHCs could use to design, develop, and implement the integration of primary care within their agency.11 Applying the EPIS sustainability framework to the integration of primary care programming implementation, this case study contributes to the understanding of contextual factors that have been pivotal to implementing and sustaining integrated care within a behavioral health setting.

Background

The United States has long struggled with high health care costs that do not result in high-quality care.12 The ACA was designed to reorganize the healthcare system through the “triple aim:” improving health outcomes and patient experiences while simultaneously decreasing costs.12 The legislation defines healthcare delivery standards and payment methodologies which encourage care coordination and communication across service systems.13–14 As these strategies are new to the United States health care marketplace, the ACA also funded mechanisms for continuous health care innovation,14 primarily the CMMI.14

Through the ACA, the CMMI is allocated $10 billion every ten years to experiment with new or underdeveloped healthcare delivery and payment strategies.14 In 2011, the CMMI requested cost-effective proposals that would create new models of workforce development and enhance infrastructure support.15 The first round of CMMI’s Health Care Innovation grants awarded $1 billion to 107 agencies.15 During the three-year award period, CMMI provided technical assistance to grantees with an external vendor which included program evaluation. Funded projects ranged from implementing patient engagement and shared decision making to creating patient-centered medical homes.

Current literature on collocated integrated primary care within mental health settings demonstrates positive effects on preventative and chronic disease care.16 Clinical trials show that adults with serious mental illness receiving collocated integration of primary care at their mental health center were more likely than their treatment-as-usual peers, who receive healthcare services at separate clinic locations with minimal coordination, to utilize preventative services and to have seen their primary care provider within the last year.8–9 Interventions that educate and train behavioral health clinicians to promote and track physical health outcomes and behaviors, demonstrate reduced emergency department utilization, increased outpatient primary care visits, and improved quality of life.10, 17 However, there remains a gap in the literature describing the implementation process of integrated primary care practices in community mental health settings.

The lack of knowledge concerning the implementation process is compounded by the limited financial support for integrated care models, especially after grant funding ends.12 Health researchers have voiced concerns about the financial sustainability of grant-funded integrated care for programs in a fee-for-service (FFS) payment healthcare marketplace without major Medicaid payment reform.12, 18 With few states changing Medicaid funding to support integrated care efforts,19 it is unclear how clinics can sustain uncompensated collaborative care practices.12, 18 Despite the investment in various types of integrated care programming, details are lacking that elucidate on-the-ground experiences of how mental health practitioners implement and deliver integrated care and how services can be sustained financially in the long-term after grant’s end.

To address the gaps in the literature on the process of implementing and sustaining grant-funded primary care integration within community mental health settings,7, 12 a partnership with a CMHC in the Pacific Northwest (henceforth referred to as Orcas Behavioral Health or OBH) was created to gather data for this case study. The purpose of this case study was to describe implementation barriers that influence program sustainability and provide strategies for future community mental health and primary care integrated care program development. This case study sought to answer the following questions:

What are barriers to implementing grant-funded integration of primary care within behavioral health programming? and

What are the challenges to sustaining the integration of primary care within behavioral health settings without federal financial support?

Study Context

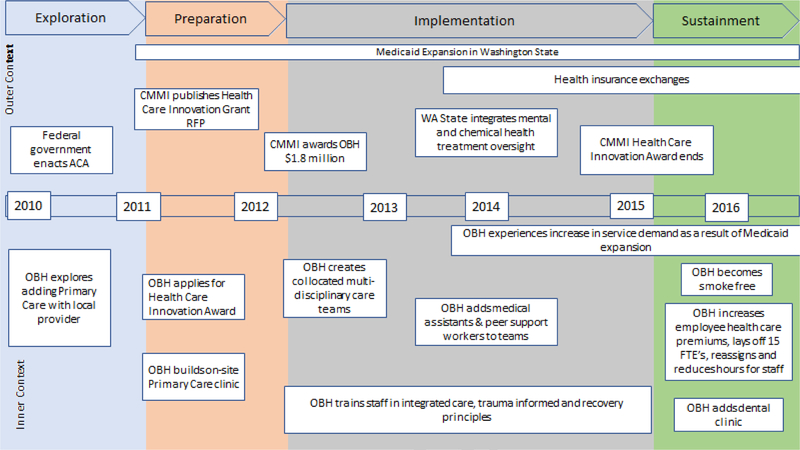

Facilitated through a combination of leadership passion and a three-year $1.8 million CMMI grant, Orcas Behavioral Health (OBH) implemented a collocated primary care and behavioral health integrated care model. The motivation for service innovation stemmed from the executive team’s personal and professional desire for whole person care. Multiple participants stated that the agency was going to commit to this model regardless of the grant because it was the type of work that was needed; clients were dying preventable deaths. However, like so many other primary care and behavioral health agencies across the country, OBH began the transition to integrated care with grant funding. There were multiple stages to OBH’s implementation of integrating primary care into their behavioral health clinic (Figure 1), which were shaped by internal agency events, as well as state and federal policies.

Figure 1:

Timeline of Integrated Care at Orcas Behavioral Health

OBH is a publicly funded community mental health center serving a mixed rural and urban population and is the primary mental health and substance used disorder (SUD) treatment provider for a county of approximately 250,000 residents in the Pacific Northwest. OBH has approximately 450 paid staff members and an annual budget of about $31 million. It serves over 7,000 clients per year. The agency provides community-based outpatient and inpatient mental health and SUD services. The majority of client population is low income and is a recipient of Medicaid or Medicare. Stemming from a waiver agreement in the 1980s, a state-managed oversight entity contracts with OBH to provide care through a per-member-per-month sub-capitated Medicaid payment system. This arrangement shields the agency from having to engage in FFS billing; it also allows them to be flexible with funds for program development and staffing allocations, which were apparent during data collection for this case study.

Data collection occurred approximately one year after the grant period ended; at that time, OBH was preparing the next fiscal year’s budget and subsequently laid off 15 full-time equivalents, re-assigned 14 individuals, reduced hours for ten staff members, and determined not to fill 12 open positions. Besides staffing, there were substantial changes to the staff members’ family health care premiums, paid time off, and disability leave. Workers reported low morale, struggles to maintain higher caseloads, and constant searching through job ads. Throughout the layoffs, reassignments, and financial difficulties, middle and executive leadership voiced a strong commitment to preserving and expanding integrated health programming at the agency by adding dental care to their array of collocated services. Funds that could have been utilized to preserve staff, decrease caseloads, or maintain health benefits for employees were instead allocated for building renovations and dental services for clients. These factors contributed to the inner and outer context of OBH’s integration of primary care within their behavioral health clinic implementation process.

Inner and Outer Context

The EPIS framework highlights both the agency’s internal and external processes of implementation throughout the exploration, preparation, implementation and sustainment.11 The inner and outer context factors describe opportunities and challenges for agencies as they implement innovative practices within public service sectors.11 These factors include, but are not limited to, sociopolitical, funding, organizational culture, and fidelity monitoring.11 The combination and weight of each factor evolve throughout implementation based on phase, leadership practices, agency environment, and organizational culture.11 In addition to an ebb and flow in the strategic importance of each contextual factor throughout the EPIS stages, implementation efforts may not occur linearly.11, 20

The EPIS conceptual framework can be applied to an agency’s overall implementation of innovative practice or provide a more focused analysis at one stage. In this case study, the primary focus is on the sustainability phase of the EPIS conceptual framework; however, because some program components lacked development in previous stages, the contextual factors were not solely limited to those in the sustainability phase. Within sustainability, outer contextual factors include sociopolitical (e.g., leadership, state, local, and federal policies.), funding, and public-academic collaboration.11 Inner contextual factors include organizational characteristics (leadership, embedded EBP culture, a critical mass of EBP provision, and social network support), fidelity monitoring and accompanying support (EBP role clarity, fidelity support system, and supportive coaching), and staffing.11 The growing literature around program or intervention sustainability has demonstrated that service environment, inter-organizational environment, consumer support/advocacy, intra-organizational characteristics, and individual adopter characteristics can impede or facilitate programming.11

Studies using the EPIS framework to investigate EBP sustainability in community mental health settings have shown that several factors can affect on-going use of interventions: e.g., financial barriers (uncompensated care and cost-cutting), 21–22 workforce turnover,21 policy changes,22 and difficulty maintaining the intervention after the implementation period.21 There is a growing effort to explore how implementation frameworks can be utilized not just with EBP implementation but in public health interventions and policy planning.23–24 Including such frameworks with policy implementation may facilitate new understandings and theory development.25 Because integrated care is an approach that utilizes an interdisciplinary team (nurses, physicians, SUD, and mental health clinicians) and lacks standardized components that EBPs typically include, this type of program implementation provides a unique application of the EPIS conceptual framework and allows for additional development of inner and outer contextual factors. Considering most health research describing on-going implementation needs for integrated care has focused on financing and health insurance payment structures,12, 18 applying the EPIS framework to OBH’s situation will provide insight to agency and system infrastructure needs when community mental health settings develop new grant-funded programming.

Methods

Case studies are appropriate to investigate how or why a phenomenon occurs within a real-life context,26–27 when the subject of an investigation is highly applicable to practice situations,27–28 and for analyzing sustainability and implementation factors within public health programs.24 The design for this case study utilized multiple data sources, such as semi-structured interviews, staff observations, and agency documents, to investigate this policy initiative. This study also employs various sampling and data analysis techniques to complement data triangulation,27 which are described below.

Sample

The primary unit of analysis, OBH, was purposefully selected using a critical case sampling design.29–30 Critical cases are those that are both information-rich and can generate knowledge development;31 items that are observed in the case used can occur in similar settings, thus demonstrating a potential pattern.30 OBH, like so many other CMHCs, began its integrated care program through a federal ACA grant fund.12, 32 OBH was selected for this case study because it had used a systematic process to explore, plan, and implement an integrated care model through grant funding, and any difficulties that they experience in sustaining the model would be like those of others who were similarly grant funded.

Interviews with key informants, observations of an outpatient clinical team, and agency documents informed this case study analysis. Ten key informant individual interviews with the integrated care leadership team were conducted for this case study. The inclusion of an individual as a key informant was based on the individual having a role in implementing, designing, and sustaining the integrated care policy and grant program. Key informants were directors, coordinators, and project managers working at the agency or contracted with during the grant period; all participants identified as European American. Nine of the ten key informants were female. OBH’s integrated care leadership team partnered in the research process to identify appropriate key informants with substantial knowledge on the development and implementation of their integrated care programming. Each person who was asked to participate in this component of the study consented to an interview; because practitioners at this agency have a productivity requirement which, if unmet could result in disciplinary action, employee direct service time for interviews was not diverted.

Although direct service employees were not interviewed, one outpatient team was selected by agency leadership for in-depth observation based on their successful participation in the grant-funded programming. Recruitment of the outpatient clinical team took multiple steps. First, the supervisor was recruited. After the supervisor approved her team’s involvement, the study recruiter spoke with the team at a daily huddle meeting. Follow up meetings with individual team members who were not present at the team meeting were then conducted. The team included an Advanced Practice Registered Nurse, two master’s prepared outpatient therapists, a medical assistant, two peer-support workers, four bachelors prepared care coordinators, an administrative support worker, a substance abuse specialist, and a clinical supervisor. Part-time employees, those who were on vacation for a significant time (1 to 2 weeks) during the observation period, and team members who, during the observations, discussed job searching activities, were more likely to decline participation. Observations were conducted within their team space and during huddles during regular business hours. Of the 13 individuals on the outpatient team, seven consented to participate in the study; all seven participants identified as European American and six out of the seven were female. Informed consent was obtained from all interview participants and a selection of the outpatient team. The Human Subjects Division within the University of Washington approved this study #50280.

Data Collection

Interviews

The primary author conducted all interviews, observations, and data analyses. These were semistructured interviews lasting approximately one hour. By the last interviews, participants were repeating similar information, demonstrating data saturation. These interviews provided in-depth knowledge about the effects of context on the agency’s implementation process.33 Interview questions were developed and then reviewed by a supervisory committee relying on implementation theory, specifically the literature on agency characteristics, sustainability, leadership, and model design.11, 20, 34–41 Interviewees were asked to describe a) the agency before, during and after grant implementation, b) the motivation process and staff interactions during and after implementation, c) the integrated care model of the organization, and d) processes designed and used for sustaining integrated practice. The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and then checked for accuracy.

Documents

Documents were collected from internal and external sources. Items were selected if they addressed the agency’s integrated care philosophy, implementation techniques, staff practices, employee roles, and the maintenance or discontinuation of integrated care programming at the agency. Internal documents include Annual Reports from 2009–2015, staff produced presentations about integrated care programming, all-staff email correspondences from June to September of 2016, agency new-hire paperwork, client intake forms, posted announcements on agency bulletin boards, and training documents. External sources include publicly available legislation, presentations, and contracts describing state and federal regulations, as well as relevant policy initiatives.

Observations

Employees of OBH were observed over four months in trainings, shared spaces, daily huddles, and around the main campus of the agency. Field notes included both descriptions of verbal and non-verbal events as well as observer comments interspersed within the notes, which were documented as such.42 Documents were indexed according to date, type, source, and purpose within NVivo 11.43

Data Analysis

The first cycle of coding utilized provisional and process methods simultaneously.43–44 The case study data were coded using provisional codes43–44 that were taken from the EPIS framework11 regarding the necessary components, characteristics, and contextual factors for sustainability. Additionally, the transcripts, field notes, and study documents were coded using the process method of coding.43–44 After the first cycle of coding, code mapping was utilized to reorganize the codes into categories and condense them into central themes or concepts.43–44 The second cycle of coding involved pattern coding, which allowed explanatory or inferential codes to arise that could generate emergent themes.43–44 Memo writing was used throughout the process to take note of ideas and themes that required attention and reflection, and this also served to document the research process.42, 44 As noted, multiple sources of data from various aspects of the case study were used, to develop ideas of replication and convergence.28, 30 Together, these produced a logical chain of evidence to support the created constructs.43 These categories have been synthesized into main themes that are described in the Findings.28

Findings

In this study, the information provided by key informant interviews, agency documents, and staff observations demonstrate that during and after the grant funding ended the agency’s leadership maintained great passion for integrated care and a continued desire to enhance services, while at the same time agency staff described struggles to provide day-to-day care amongst budget cuts and higher caseloads (Table 1). The interviews, observations, and document analysis generated four themes: (1) integrated care as a journey, (2) everything and nothing, (3) system barriers, and (4) change is difficult. Integrated Care as a Journey describes the evolution of OBH’s conceptualization of integrated care as the grant program period progressed. Everything and Nothing details OBH’s attempts to fit so many training components into the grant program that learnings were not retained and outcome measures were not maintained one year after grant’s end. The first outer context theme describes how System Barriers, such as Medicaid payment methodology and conflicting federal laws governing SUD and mental health treatment, created challenges to integrated practice. Lastly, Change is Difficult, describes the role of professional identities and the lingering social hierarchies they create within integrated care teams. The following sections include further descriptions of the themes, along with quotations from participants. Some of the participants’ words were modified to enhance readability by eliminating filler phrases, sounds or words (e.g., um, you know and like). Since all but two of the participants were women, respondents are not referred to by gender; likewise, great care was taken to ensure individuals were not identified by role or position.

Table 1:

OBH Challenges and Successes with Primary Care Integration

| Challenges | Successes | |

|---|---|---|

| Inner Context | • Lack of universal definition for “integrated care” • High turnover at the agency • Budget shortfall (e.g. change in health insurance premiums, layoffs, unfilled positions) • Lack of insurance/coding knowledge • Lack of data collection and fidelity monitoring for EBPs |

• Strong commitment by leadership and staff • Strong community partnerships with area primary care and dental clinics • Flexible funding mechanisms • Organizational commitment to training and learning |

| Outer Context | • Separate SUD and mental health funding and treatment requirements • Data privacy regulations (e.g., 42 CFR) • Professional discipline social hierarchy and rigidity |

• Federal and state policy promotion of integrated care • State waiver for treatment plan integration • Community support for agency practice change |

Inner Context Themes

Integrated Care as a Journey

Integrated care persisted as an elusive concept for OBH. Leadership, through the interviews, debated the definition of integrated care and how OBH needed to evolve to meet it. To some directors, integrated care focused on integrated electronic medical records, a wellness plan that included everything about a person, and having physicians on staff, not just a collocated clinic. Others on the leadership team viewed integrated care as a more population-based health work that provided preventative rather than reactionary services. Sometimes managers used “integrated” to describe their internal process of merging SUD and mental health care and others reserved “integrated” for services that involved physical health care. However, overwhelmingly, OBH leadership believed “this is a decade process and…we’re asking people to change policies and practices and procedures and ways of viewing themselves in their work and their how their profession works, …[this] take[s] a lot of time and a tremendous attention to detail” and that they had only just begun.

Additionally, the impression that the model was evolving was heightened because they had lost momentum with massive layoffs a year after the end of the grant period. There was a concern that they were becoming less integrated without grant funding and support — staff who collected and analyzed data left with the grant funding. Then later, nurses who provided reproductive health care information to teen clients and smoking cessation sessions were laid off. Outpatient services were provided in groups to maximize staff productivity rather than individually. The nostalgia for the laid-off employees, manageable caseloads, and staff time to focus on health promotion activities were palpable: “it’s been hugely painful to all of us. We’re doing the best we can… Hopefully we return to those times where funding will support those efforts and we can continue to do the work that we know we should be doing.”

The journey for OBH did not always go as planned. As they developed their integrated care model, the agency had to modify medical billing and clarify the role of the medical assistants. A secondary effect of having a sub-capitated payment system for mental health services shielded OBH from standard practices such as connecting services with specific diagnosis codes; this manifested in not knowing who was legally credentialed to obtain vital signs, perform glucose and urine analysis tests, and handle medications. As the programming became more institutionalized, these issues were noticed with more frequency; “it’s just the momentum is so fast, nobody’s been able to step back and ask, ‘Did we dot all the i’s and cross all the t’s?’” Adding medical assistants and other medical personnel brought to light the “cultural difference[s]” between the community mental health and medical models. Once medical assistants were brought to the table, to coordinate health insurance and navigate medical systems, administrators learned that they could also perform venipuncture. Transferring venipuncture responsibilities from nurses to medical assistants altered the care practices of OBH. The agency found, with new eyes, they could be more efficient and patient-centered by restructuring the timing of medication delivery from every two weeks to monthly: “I think that’s a good outcome for clients and they’re finding that they’re going to have better med compliance because they weren’t coming in… Now they’re going to do a monthly injection, then those people would be more stable.” Through daily practices, they continued to find more ways to enhance their system—some planned, some unplanned. There was a continual impression that their model was everchanging, every day offered an opportunity to learn how to be more integrated.

At the time of data collection, the agency was simultaneously in a period of expanded service growth (dental) and workforce loss (nurses). The integrated care implementation and sustainment process were continually changing, finding holes while moving ahead and behind; this became a barrier to sustainability for the agency: the leadership had inconsistent definitions of integrated care and the application of the model ebbed and flowed.

Everything and Nothing

The CMMI grant allowed OBH to advance staff knowledge through training and access to several EBPs that may or may not be specific to integrated care but were implemented at the same time and became tied to their model. According to the original grant proposal, the agency pledged to train their staff in an array of EBPs “including but not limited to” Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), Motivational Interviewing, Moral Recognition Therapy, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Cognitive Processing Therapy, Adverse Childhood Experiences, Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment, Coaching for Activation/Patient Activation Measure (PAM), and other health promotion strategies.45 Interviews described additional EBPs like Living Well, Illness Management and Recovery, Wellness Recovery Action Planning, Screening Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), and Whole Health Action Management were added during the grant. However, it became difficult to sustain the new knowledge, “we trained and trained and trained and trained and trained. There also was a certain amount of fatigue, because you still had to see clients.” Some pieces of training were delivered during the on-boarding process, such as SBIRT and Motivational Interviewing, whereas others, such as DBT, were delivered online. There was no report of “supportive coaching” or ongoing refresher coaching for the trained EBP models.

In combination with the influx of training, EBP components were started and then stopped throughout the process based on staff perception of usefulness. The PAM was rolled out to the staff for data collection and treatment planning purposes but was discontinued “in part because it got way more expensive and, also, because it was very computer-based” which “didn’t seem to fit how care coordinators were doing their work.” When possible, OBH decided not to be registered or buy licensed EBP models due to cost and “because there is a boat-load of data that needs to be collected… and the sense was there was already a lot of [health] data being collected [for the grant].” The health data reporting required by CMMI was supposed to help facilitate data-driven services and population health initiatives. Beyond noting if the client had a primary care physician (PCP), health data included the following: date of last PCP visit, smoking status, substance use diagnosis, blood pressure, body mass index, and other “standard metrics of chronic measures.” During the implementation period, medical assistants were “swimming in paper” as the primary data collectors. There was no evidence that adult outpatient teams utilized the health data that was collected, which was frustrating because “we spent a lot of time pulling together behavioral health data and primary care data” to create reports for the clinicians; and while “that is one of the things that I thought teams might use more, I don’t think anybody is using them now… maybe they didn’t know what to do with it.” After the grant funding ended, OBH stopped recording health data for clients unless they were seeing a medication prescriber.

While staff members were saturated in training and health data, there was a concern that clinicians never learned how to apply what they learned with their clients. OBH indicated that most of their integrated care work relied on motivational interviewing. Saying that without substantial skills in motivational techniques, clinicians only focus on the crisis at hand and not the overarching health risk; there is a need to “put more structure in place to help even the less skilled clinicians get there faster with clients.” Through the new employee orientation, everyone is trained in the basics of motivational interviewing; however, there were no booster sessions or on-going support in how to apply this technique within a health context:

I think [the clinicians] might be doing the best they can. What I think what we’re not doing, maybe is at the front side when they’re hired and maybe going back in to do refreshers and making sure… I don’t know if anybody has ever jumped into their world and said ‘how are we integrating here?’ or just providing those monthly sessions on hypertension, diabetes, or whatever; how do they actually fit that into work… I don’t think we’ve done that, and maybe I’ve been mistaken; maybe it’s occurred at some point, but if it did, I don’t think we went back and revisited it.

The CMMI grant got the “jump start [on] things and [OBH] on the right path” but EBP and data-driven decision-making represent long-term processes, not one-time events. The influx of training was reported as extraordinarily helpful but insufficient in moving the workforce into proficiency with the different EBP components or health data analytics within daily clinician practices.

Recording blood pressure and BMI are helpful, but only if the clinician understands why these data points matter and how they contribute to the overall wellness of the client. EBPs are designed to enhance service quality and efficacy, but if the clinician does not know how to apply the interventions or get ongoing support and fidelity training in them, they will not use what they learned. These factors created barriers to sustaining the EBPs and the integrated care model itself: clinicians received the training they needed to provide data-driven and evidence-based treatment, but they never learned how to apply the knowledge they received.

Outer Context Themes

System Barriers

There are policy and legal issues that kept the integrated care model from being as successful as OBH leadership wished. Their regional Medicaid managed care payer merged SUD and mental health service contracts and oversight, but not payment systems. The federal and state Medicaid rules and expectations have also not changed to promote integrated care delivery. OBH experienced discrepancies in policies related to data privacy, disciplinary profession regulations, and funding. First, data privacy differences between mental health and SUD treatment have limited the agency’s ability to communicate with emergency departments. Leadership expressed the difficulty of being a “fully integrated agency, that inhibits us from sharing information on a lot of our clients” and that it becomes confusing if there is “any suggestion of [chemical use]…this is like…a real conundrum because people can say, ‘oh I had a few beers this weekend,’ so does that cross the 42 CFR threshold or not?” Second, learning the varied rules and adhering to them across professions was difficult. This issue was also apparent when complying with statutory expectations for Medicaid approved treatment plans. The expectations in Washington State were different for SUD and mental health treatment plans and each service required its own separate plan. OBH reported receiving a waiver from the legislature to create a merged treatment plan that would suffice for both services but it was projected to end in 2017. Last, Medicaid has separate funding strategies for the two lines of service: “we [had] sub-capitated funding for our mental health, but our chemical health/substance use disorder services was fee-for-service so we actually had two separate economies underneath one roof providing integrated care.” The differences in funding were challenging to manage, requiring the substance use disorder staff to return to discipline-specific supervision for revenue maximization rather than maintain the multidisciplinary team structure

The Medicaid financing and treatment requirement barriers that OBH experienced were similar to those discussed previously within the literature. Even though several state and federal infrastructure initiatives were promoting integrated care, the larger system structures were not supportive. The lack of consistent payment methods, treatment requirements, and privacy standards created significant sustainability challenges.

Change is Difficult

Mirroring the siloed statutes and funding streams, shifting the workforce towards integration has been difficult. One of the first things OBH did in their path to integration was to collocate staff and create multidisciplinary teams. Medical providers (APRNs and psychiatrists), nurses, clinicians, and care coordinators moved from their separate wings and were housed together. This spatial proximity facilitated impromptu consultation between team members, as well as, enhanced drop-in access and easy scheduling for clients.

Spatial positioning was implemented, but social repositioning proved to be a more difficult transition for OBH. The collocation of OBH staff was meant to break down long-standing power imbalances between professional disciplines. The diffusion of staff into collocated teams was protested heavily by the medical providers and nurses who relied heavily on consultation and support provided by their disciplinary peers and “it’s still an on-going problem today…the med providers wish they were all together. Still.” Part of the rationale for the move was that care coordinators were feeling beholden to providers for information: “if you have the nurses and the docs over here and they have good information that we need or they need to know information, we always have to come to [them];” that if the teams were collocated, communication would be more fluid and there would be less of a power discrepancy. The hope was that a behavior shift would occur in the daily huddles. Even with the team supervised by a clinical social worker or clinical counselor, daily huddles continued to be “probably more focused on docs than it needs to be,” which was evident when the observed team decided not to meet because the medication management provider was on vacation.

Second, according to the informants, the referral process between services was not smooth. Daily huddles were created to allow for consultation and referrals between team members; however, only high-needs clients and the patient list for the medication provider were discussed. When care coordinators attempted to refer individuals for medication management or SUD treatment, the provider begrudgingly accepted the client after asking a series of deflecting questions. The siloes between service options at OBH were lessened, but they were still there.

Lastly, the nurses’ professional identity impeded integrated care efforts. OBH placed a psychiatric nurse on each integrated care team, in the hopes that she would move from daily care management to “more population health based approach. But it never really came to fruition.” The agency wanted the nurses to start conversations concerning diabetes prevention and be the primary providers of tobacco cessation services, but it was found that “they’d been here for a very long time and their role had really been kind of a psych nurse model with medication being at the heart of it.” There was also concern that the nurses “didn’t want to go to the top of their credential” and leave injections and other physician supporting services to the medical assistants. As the agency wanted to “formulate [the nurses] role and shift it,” it was determined that the medical assistants could do the daily tasks that the outpatient nurses were doing and they were laid off. To sustain the integrated care model, OBH exchanged the psychiatric nurse, a more traditional community mental health role, for a less expensive and less trained medical assistant who could perform similar functions.

Adhering to traditional professional norms impeded sustainability for OBH. Staff members’ habits were difficult to change during the 3 years of implementation. Traditional communication patterns across disciplines persisted as evidenced through staff meeting structures, a hesitancy to accept referrals across services, and a refusal from the nurses to move towards population-based health care. To counter the professional discipline rigidity, the agency relied more on medical assistants to promote positive health behaviors, interactions with primary care physicians, and support to the medication prescribers. Change is difficult within professional disciplines and proved hard to counter within OBH’s organizational culture.

Discussion

Across the United States, CMHCs are transitioning to integrated practice with federal grant support. After grant funding ends, clinics often attempt to continue programming without additional funding or supporting policy infrastructure.7 OBH’s experiences with layoffs, decreasing staff positions, and lowering employee benefits speak to the difficulties of maintaining services without changes in healthcare reimbursement methods or supplemental grant funds. This case study’s findings demonstrate that implementing and then sustaining integrated care models in a CMHC would benefit from a flexible workforce, shared definition, policy and funding congruence between the agency and state/federal regulations, and on-going support and training in practice application. The barriers to sustainability found within this case study are not unique to OBH.

Integrated care demands a flexible workforce of members who can transcend traditional professional disciplines and power dynamics. Interprofessional teamwork requires collaborative skills such as cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, communication, autonomy, and coordination,46–47 which mirror integrated care service components. Research has demonstrated that cross-training primary care and behavioral health providers in physical health clinics is difficult because of their professional training which does not highlight the merits of other disciplines, working styles, and communication skills,48–49 that may lead to maladaptive hierarchical communication patterns48 and the absence of democratic decision-making.49 Power dynamics across health professionals manifest in situations where providers want to protect their autonomy and reduce dependency on others,50 which supports the prioritization of those with higher education levels and salaries.48 Since medical settings are centered around the physician, it is not surprising that most research conducted on integrated care focuses on the primary care setting and is quiet concerning issues of power dynamics. An area of research that has demonstrated potential promise for decreasing communication barriers within interdisciplinary teams with high task interdependence is relational coordination.51–52 Relational coordination links the effectiveness of coordination of care with the quality of communication amongst the interdisciplinary team,51–52 highlighting frequency, focus on problem-solving, quality of relationships, shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect.51 CMHCs engaged in primary care integration need to create intentional processes that monitor communication patterns, challenge traditional hierarchal relationships, and train staff on how to effectively work in interdisciplinary teams, such as relational coordination.

When developing a primary care integration model, CMHCs need to be clear on the components and design of their program. With a consistent definition and understanding of the desired type, level, process, breadth, and degree of integration,53 the CMHC can be more targeted in job descriptions, training, and practices. OBH had a loose understanding of integrated care as a concept and an inconsistent application of their model across the agency, which is common amongst grant-funded integrated care initiatives.12 As OBH’s model evolved, it became apparent that population-based health care delivery was crucial to their design, and this contributed to the nurse layoffs. Having a shared definition and care delivery standards would help an agency monitor integrated care services, provide guidance for training and development of workers, and provide on-going momentum for integration.54

As providers begin to develop integrated care models, they are often ahead of the siloed health policies and payment systems.18 Without grant funding, the different Medicaid payment types for SUD and mental health fractured the interprofessional team structure, which is typical for integrated care programs.1, 12 Further consequences of losing grant funding were demonstrated in the loss of the nurses, position layoffs, and other staff changes during the summer of 2016. Also, although the state is advancing integrated care in some initiatives, the OBH’s waiver for the separate SUD and mental health treatment plan requirement was issued piecemeal and subject to expiration. If integrated care is to continue to advance, Medicaid rules and standards need to be more flexible across location and requirements need to change rather than forcing agencies to create short-term workarounds. Lastly, it is crucial that public funding streams, like Medicare and Medicaid, support integrated care delivery so that programming can be sustained after grant funding. Collaborating with state policymakers, particularly concerning Medicaid, is crucial for CMHCs developing integrated care models.

A further barrier for OBH was a reliance on one-time trainings, which, as commonly discussed in the literature, are insufficient in assisting clinicians in altering daily practice.55 Clinician adherence and skill with EBPs are enhanced with on-going consultation and support packages.55 Had the CMHC in this case study incorporated booster or consultation sessions, the clinicians could have solidified their skills and better applied the interventions and techniques in practice. Lastly, with so many trainings happening within 3 years, the dilution of each EBP was likely.

The primary care integration in behavioral health settings has a promising future, particularly if interdisciplinary teams can learn to share power, statutes governing practice are updated, and funding mechanisms are aligned. Collocated and coordinated care is possible with strong partnerships, worker flexibility, and system structure change. As more CMHCs transition to primary care integration models, interdisciplinary training and Medicaid rules and payment structures will need to re-align to meet the needs of this emerging approach to care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as the grant had ended a year prior, the agency lacked client outcome data to triangulate with the qualitative methods employed by this study. Second, participant recruitment from the outpatient treatment team was lacking, speaking to the difficulties of doing organizational studies in environments responding to significant turnover and change. Additionally, individual front-line employee interviews were not conducted due to the agency’s financial constraints and need to maintain productivity expectations. Had such interviews been included, the findings might have led to a greater understanding of reduced employee response rate and team dynamics. The limited involvement of direct-line staff in the study and lack of outcome data may have limited generalizability to other CMHCs.

There are several areas in which further research is warranted. While there are numerous studies that describe roles and job functions within integrated care teams,8–10 this case study demonstrates that mental health providers struggle with transferring health information such as blood pressure, weight management, and smoking cessation into a mental health context. Further, the experience at OBH indicates that interdisciplinary teams would benefit from further cross-training and role clarification. Lastly, findings from this case study illuminate the difficulty of maintaining innovative interventions after grant-funding ends, even when there is considerable policy support. Specifically, OBH’s experience demonstrates that interventions require targeted financial support for sustainability. Future research is needed to gain more specificity of daily integrated care practices conducted by behavioral health providers in an interdisciplinary team setting7, 56 and Medicare and Medicaid payment models that enhance program sustainability.7

Implications for Behavioral Health.

This case study speaks to the application of primary care integration in a behavioral health setting, exploring potential barriers to implementation that result from grant-funding, as well as the challenges that arise without on-going federal financial support. The lessons learned by OBH are valuable for future adopters of integrated care so that they can be more specific in design and anticipate system issues that impede implementation. To enhance sustainability, CMHCs should begin with a shared definition of integrated care that speaks to both the care components and location of service delivery. Also, integration efforts should then be tailored to meet this definition, including but not limited to job descriptions, EBP selection and adoption, performance appraisal systems, financial systems, and agency policies. Considering the system and payment issues with integrated care, partnerships across the service sector and government levels are also crucial to model success and on-going financial viability. Creating and negotiating fiscal models with medical insurance carriers, including Medicare and Medicaid, that support collaborative and integrated care programming after initial start-up grant funds are utilized is a necessary component of the implementation process. Last and critically important, CMHCs implementing integrated care need to utilize techniques that support collaborative power-sharing between disciplines and promote front-line provider engagement and adoption. Although further research is warranted to uncover insurance payment and interdisciplinary teaming strategies, this case study contributes much to the discussion of how primary care integration and integrated mental health and SUD treatment present within a CMHC and the substantive need to investigate power dynamics between disciplines within these settings.

Acknowledgements:

This work was funded by the National Institute of Health (TL1TR000422). The methods, observations, and interpretations put forth in this article do not necessarily represent those of the funding agency. The author would like to thank Jean Kruzich, Gunnar Almgren, and Larry Kessler for their guidance in this research project and Kitsap Mental Health Services for partnering on this research adventure.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement

There are no known conflicts of interest in the production of this study. National Institute of Health (TL1TR000422) funded this work. The methods, observations, and interpretations put forth in this article do not necessarily represent those of the funding agency.

References

- 1.Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne A, Pincus H. From silos to bridges: Meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illness. Health Affairs. 2006; 25(3): 659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks J, Svendensen D, Singer P. et al. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. Alexandria VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2006. Available on line at https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Mortality%20and%20Morbidity%20Final%20Report%208.18.08.pdf Accessed on January 11, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, et al. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-Year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Medical Care. 2011; 49(6): 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croft B, Parish S. Care integration in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Implications for behavioral health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 2013; 40: 258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. §18001 (2010).

- 6.Ader J, Stille C, Keller D, et al. The medical home and integrated behavioral health: Advancing the policy agenda. Pediatrics. 2015; 135(5): 909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey T, Crotty K, Morrissey J, et al. Future research needs for evaluating the integration of mental health and substance abuse treatment with primary care. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2013; 19(5): 345–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Druss B, Rohrbaugh R, Levinson C, et al. Integrated Medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001; 58: 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Druss B, von Esenwein S; Compton M. et al. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: The Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010; 167: 151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanderlip E, Henwood B, Hrouda D, et al. Systematic Literature review of general health care interventions within programs of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2017; 68(3), 218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011; 38(1): 4–23. Doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller B, Ross K, Davis M. et al. Payment reform in the patient-centered medical home: Enabling and sustaining integrated behavioral health care. American Psychologist. 2017; 72(1): 55–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser Family Foundation (2013). Summary of the Affordable Care Act. Available online at http://www.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/summarv-of-the-affordable-care-act/. Accessed on January 11, 2019.

- 14.Roosevelt J, Burke T, Jean P. Commentary on Part I: Objectives of the ACA In The Affordable Care Act as a National Experiment: Health Policy Innovations and Lessons. Ed. Selker H. & Wasser J. New York: Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. (n.d.) CMS (n.d.) Health care innovation awards. Available online at https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Health-Care-Innovation-Awards/index.html. Accessed on January 11, 2019.

- 16.Bradford D, Cunningham N, Slubicki M, et al. An evidence synthesis of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013; 74(8): e754–e764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanderlip E, Williams N, Fiedorowicz J, et al. Exploring primary care activities in ACT Teams. Journal of Community Mental Health. 2014; 50: 466–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manderscheild R, Kathol R. Fostering sustainable, integrated medical & behavioral health services in medical settings. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014; 160(1): 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown Levey SMB, Miller BF, deGruy FV. Behavioral health integration: An essential element of population-based healthcare redesign. Translational BehavioralMedicin,2012; 2(3): 364–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blasé KA, et al. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (FMHI Publication #231) Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network. 2005. Available online at http://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/resources/implementation-research-synthesis-literature. Accessed January 11, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bond G, Drake R, McHugo G, et al. Long-term sustainability of evidence-based practices in community mental health agencies. Administrative Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2014; 41: 228–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willging C, Lamphere L, Rylko-Bauer B. The transformation of behavioral healthcare in New Mexico. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015; 42: 343–355. DOI 10.1007/s10488-014-0574-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDonald M, Pauly B, Wong G, et al. Supporting successful implementation of public health interventions: Protocol for a realist synthesis. Systematic Reviews, 2016; 5(54): 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheirer MA, Dearing J. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. American Journal of Public Health. 2011; 101(11): 2059–2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell B, Beidas R. Advancing implementation research and practice in behavioral health systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2016; 43: 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baskarada S. Qualitative case study guidelines. The Qualitative Report. 2014; 19(24): 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin, Robert Case study research design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilgun J. A case for case studies in social work research. Social Work. 1994; 39(4), 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cresswell J. Research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palinkas LA, Horowitz S, Green C, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 2015; 42(5): 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton MQ Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.SAMHSA. Primary and behavioral health care integration grants. Available online at https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/samhsa_hrsa/performance-profile.pdf. Accessed on January 11, 2019

- 33.Green C, Duan N, Gibbons R, et al. Approaches to Mixed methods dissemination and implementation research: Methods, strengths, caveats, and opportunities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 2015; 42(5): 508–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaudoir S, Dugan A, Barr C. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient and innovation level measures. Implementation Science. 2013; 8(22): 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Damanpour F. Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. The Academy of Management Journal. 1991; 34(3), 555–590. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009; 4(50): 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durlak J, DuPre E. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008; 41: 327–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kauth M, Sullivan G, Cully J, et al. Facilitating Practice changes in mental health clinics: A guide for implementation development in health care systems. Psychological Services. 2001; 8(1): 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielsen K. How can we make organizational interventions work? Employees and line managers as actively crafting interventions. Human Relations. 2013; 66(8): 1029–1050. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science. 2015; 10(53): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torrey W, Drake R, Dixon L, et al. Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2001; 52(1): 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilgun J. Beyond description to interpretation and theory in qualitative social work research. Qualitative Social Work. 2015; 14(6): 741–752. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miles M, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Please see SAMHSA website for more information on each EBP: https://www.samhsa.gov/ebp-resource-center

- 46.Norsen L Opladen J, Quinn J. Practice model: Collaborative practice. Critical Care Nursing Clinics North America. 1995; 7: 43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005; 19: 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall J, Cohen D, Davis M, et al. Preparing the Workforce for behavioral health and primary care integration. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2015; 28(5): S41–S51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2014; 90: 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacDonald J, Jayasuriya R, Harris M. The influence of power dynamics and trust on multidisciplinary collaboration: A qualitative case study of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Heath Services Research. 2012; 12: 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gittell J, Weinberg D, Pfefferle S, et al. Impact of relational coordination on job satisfaction and quality outcomes: a study of nursing homes. Human Resource Management Journal. 2008; 18(2): 154–170. [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDermott A, Conway E, Cafferkey K. et al. Performance management in context: formative cross-functional performance monitoring for improvement and the mediating role of relational coordination in hospitals. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2019; 30(3): 436–456. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodwin N. Understanding integrated care. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2016; 16(4): 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ignatowicz A, Greenfield G, Pappas Y, et al. Achieving provider engagement: Providers’ perceptions of implementing and delivering integrated care. Qualitative Health Research. 2014; 24(12): 1711–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beidas R, Edmunds J, Ditty M, et al. Are inner context factors related to implementation outcomes in cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety? Administrative Policy and Mental Health and Mental Health Services. 2014; 41: 788–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fraser M, Lombardi B, Wu S, et al. Integrated primary care and social work: A systematic review. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2018; 9(2): 175–215. [Google Scholar]