Abstract

Background

Areca nut (AN) is the seed endosperm of the Areca catechu L. palm and a Group 1 carcinogen chewed by 10–20% of the world population. AN is often chewed with Piper betle L. leaf, slaked lime, and tobacco to form a betel quid (BQ). The negative health effects associated with AN/BQ consumption warrant the need for an evidence-based cessation program. However, systematic research on AN/BQ cessation is rare.

Methods/design

The Betel Nut Intervention Trial (BENIT; trial #NCT02942745) is a randomized controlled trial designed to test the efficacy of an intensive AN/BQ cessation program. The trial is ongoing in Guam and Saipan with adult chewers who include tobacco in their BQ. Enrolled participants are assessed for their primary (chewing status) and secondary (saliva bio-verification) outcome at baseline, 22 days, and 6 months. Participants randomized into the control arm receive an educational booklet while those randomized into the intervention arm receive the educational booklet and a 22-day cessation program modeled after a smoking cessation program and led by trained facilitators. Information on chewing behavior (history, reasons for chewing, and AN/BQ composition and dependency) are collected. The intervention effectiveness is assessed using the logistic mixed model to compare cessation status between randomization groups.

Discussion

AN/BQ chewing affects a large population of people, many of whom live in low and moderate income countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the BENIT focuses on chewers in Guam and Saipan, it has the potential for greater regional and global importance.

Keywords: Areca nut, Betel quid, BENIT, Cessation, Guam, Saipan

1. Background

The areca nut (AN) is a small, fibrous seed endosperm grown from the Areca catechu L. palm. The palm is fruitful in tropical climates that receive high levels of rainfall, such as India, Southeast Asia, and numerous islands in the Pacific [1]. Colloquially, AN is known as betel nut as it is often combined with the Piper betle L. leaf and other ingredients such as slaked lime and tobacco to form a betel quid (BQ). BQ composition has been found to vary considerably by region. Globally, AN/BQ is the fourth most commonly used psychoactive substance after tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine [2], and is consumed by roughly 10–20% of the world population [3]. Estimates of the AN/BQ chewing prevalence in the Mariana Islands recently became available: 11% in Guam [4] and 24% in Saipan [5].

In as early as the 15th century, AN/BQ has been described as a luxury food item most often consumed by royalty [6]. Today, AN/BQ is used in many social and cultural settings, and it is well documented that AN/BQ chewing often begins as a result of sociocultural influence [[6], [7], [8]]. Several studies validate factors that exist as reasons for chewing AN/BQ. For example, AN/BQ users report a feeling of euphoria, well-being, heightened alertness, and increased concentration [[7], [8], [9]]; pharmacologic studies have demonstrated that arecoline, one of the main alkaloid constituents of AN, is a principal contributor to these sensations [[10], [11], [12]].

In 2004, AN/BQ consumption, with or without tobacco, was deemed a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [13]. AN/BQ chewing has also been associated with several detrimental systemic effects on metabolism, nervous system, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal system, endocrine system, reproductive system, respiratory system, and blood and inflammatory pathways [[14], [15], [16], [17]].

Previous research has established a causal link between AN/BQ consumption and dependency syndrome. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision defines dependency syndrome as a condition in which the user experiences a strong desire to engage in a behavior, difficulty in controlling the behavior, and continued use despite harmful consequences [18]. Winstock et al. (2000) found that those who chewed AN with and without tobacco exhibited dependency syndrome comparable to cigarette smokers [19]. Two studies further confirmed the association, adding that the level of dependency differed between those who chewed AN with tobacco from those who chewed AN without tobacco, with a higher dependence among the tobacco users [20,21].

Unlike tobacco cessation, systematic research on AN/BQ cessation is rare [22]. The negative health effects associated with AN/BQ consumption, along with those of other harmful products consumed with AN/BQ, warrant the need for an evidence-based cessation program. To address the lack of AN/BQ cessation program, the Betel Nut Intervention Trial (BENIT) was implemented in Guam and Saipan in August 2016. Thus, the objective of this manuscript is to describe the rationale and design of the BENIT.

2. Methods

The BENIT is a randomized, controlled, superiority trial with two parallel groups of equal sizes. The BENIT is a project developed through the University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership to Advance Cancer Health Equity. The aims of the BENIT are to: 1) test the efficacy of an intensive AN/BQ cessation program, and 2) quantify the efficacy of the program using bio-verification. The BENIT is a registered clinical trial (Paulino and Herzog, NCT02942745) under the U.S. National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health.

2.1. Target population and inclusion/exclusion criteria

The selection of Guam and Saipan for this intervention is based on findings from a previous study conducted in these two islands in the Mariana Archipelago. Among AN/BQ chewers in the study, the prevalence of oral potentially malignant disorders in Class 2 chewers (those who consume AN/BQ with tobacco and slaked lime) was higher than in Class 1 chewers (those who consume AN alone or BQ without tobacco) at 19% versus 4% respectively [23]. Therefore, the Class 2 AN/BQ chewers are the target population in the BENIT.

Enrollment into the BENIT, which began in August 2016, is ongoing in Guam and Saipan of the Mariana Islands. The trial is anticipated to end in August 2020. The study sites are the University of Guam in Mangilao, Guam and the Commonwealth Cancer Association in Gualo Rai, Saipan. Potential participants continue to be screened for eligibility by study staff as of May 2019. Potential participants are assessed on demographics, chewing status, chewing frequency, willingness to try to quit chewing AN/BQ, and willingness to attend group intervention sessions. To be consented, participants must: 1) be a self-described chewer of AN/BQ with tobacco, 2) have chewed AN/BQ with tobacco for at least one year, and at a frequency of at least three days per week, 3) be at least 18 years old, 4) be willing to attempt to quit chewing AN/BQ within the course of participation, 5) be willing to participate in five one-hour group sessions over the period of 22 days, and 6) be able to understand, speak, and read English. Pregnant women are excluded.

Participants are recruited from a variety of sources. One source is from previous studies conducted under the National Cancer Institute-sponsored University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership to Advance Cancer Health Equity. Another source is through community efforts, including collaborative recruitment through various local health coalitions and associations, dental clinics, community health centers, village mayors, radio announcements and interviews, religious organizations, on-campus University events, and print and social media.

Once recruitment began, it became clear that at least one-third of those expressing interest wanted to participate in the trial with friends and family members. To avoid losing a large number of potential participants, we allowed individuals or groups of individuals to be recruited and randomized together. The power and analysis were adjusted to accommodate the correlation structure.

2.2. Sample size determination

Estimation of the required sample size analyses [24] for the BENIT is based on the z-test comparing two independent cessation prevalences at six months. Given the absence of AN/BQ cessation intervention studies in the research literature, it is difficult to estimate the expected difference in cessation prevalences between the two conditions. We used cigarette smoking cessation rates to compute sample size, estimated at approximately 20% at a six-month follow-up assessment [25]. Smoking cessation literature reports that interventions lead to approximately twice the quitting rate as in control groups. Therefore, we computed the sample size required to detect as statistically significant a difference in a six-month cessation estimate of 26% for the intervention condition and 13% for the control condition.

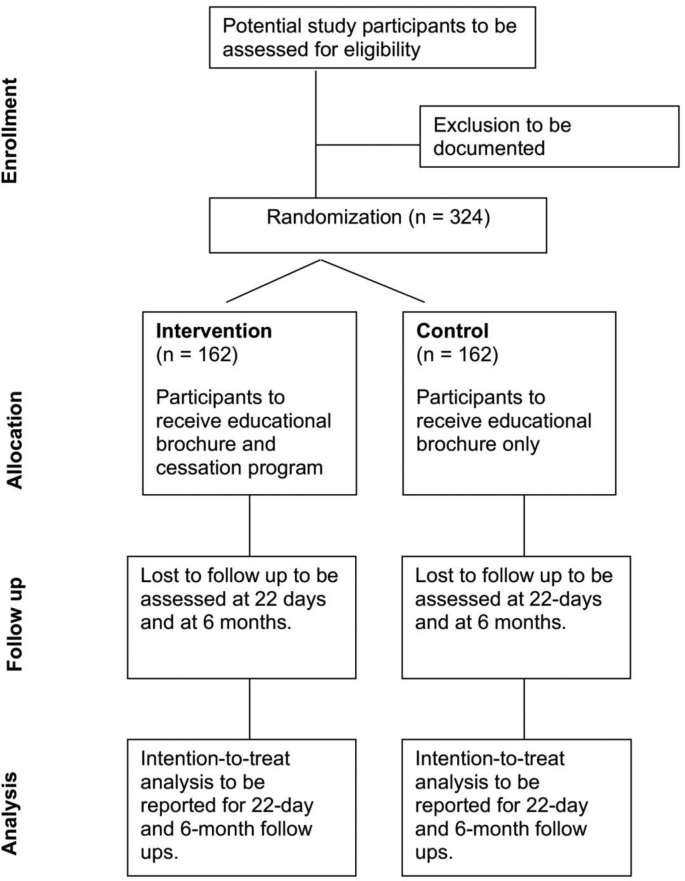

Assuming a probability of type I error of 5% (α = 0.05, two-tailed) and a power of 80% (probability of type II error β = 0.20), 145 participants are needed for each condition (290 total) to detect this difference. Assuming a 10% drop-out rate, a total of 324 participants, or 162 per group, would be needed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram for the randomization of areca nut/betel quid chewers in the Mariana Islands into a cessation study known locally as the Betel Nut Intervention Trial.

The correlation structure imposed by recruiting groups is accounted for by inflating the variance of the difference by the design effect θ = 1 + (m-1) ρ, where m is the average group size, which was set to 1.5 and ρ is the correlation between group members, which was set to 0.2. This is a conservative estimate as in past studies of behaviors within households [26] or within cluster-randomized studies [27], wherethe ρ′s are below 0.25; also the BENIT has substantial singleton participants. The sample size of 145 per group allows for a difference between 29% for the intervention condition and 13% for the control condition to be detected statistically.

This sample size is likely very conservative. The most relevant data available is from a feasibility study of AN/BQ cessation that yielded very high self-reported cessation rates of 65% at the end of the program and 100% at the one-month follow-up [28]. These results provide a tentative basis for expecting cessation rates to be as high as, and possibly higher than, those for cigarette smoking. To account for this, we have instituted an early termination protocol using the O'Brien-Fleming procedure for interim analysis [29], where the intervention will be tested at five interim stages during the study (Table 1). Stage 5 is the final analysis.

Table 1.

Five-stage criteria for the early termination of the areca nut/betel quid cessation study known as the Betel Nut Intervention Trial.

| Stage | Overall Number | Number Per Arm | Rejection Area | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 30 | |Z| > 4.5617 | 0.000005 |

| 2 | 118 | 59 | |Z| > 3.22564 | 0.0012 |

| 3 | 176 | 88 | |Z| > 2.63372 | 0.0084 |

| 4 | 234 | 117 | |Z| > 2.28087 | 0.0226 |

| 5 | 292 | 146 | |Z| > 2.04007 | 0.0413 |

Thus far, we have performed the stage 1 and 2 analyses comparing cessation rates at 22 days. Thirty individuals in the intervention arm and 32 individuals in the control arm were used in the stage 1 analysis to keep randomization groups intact. The Wald chi-squared test with one degree of freedom from the proportional hazards model using the robust variance accounting for the clustering with randomization groups was conducted. The test at stage 1 was not significant (-test = 3.7945 which is equivalent to Z = 1.9479, P = .0514). Fifty-nine individuals in the intervention arm and 66 in the control arm were used in the stage 2 analysis. The test at stage 2 was also not significant (-test = 7.1381 which is equivalent to Z = 2.6717, P = .0075). Hence, the trial continues.

2.3. Randomization

The 324 BQ chewers are being recruited and randomized equally into the intervention and control groups, as demonstrated in Fig. 1. The expected allocation is 81 participants in each arm from each island. The Biostatistics Core of the University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership oversees the random allocation. Randomization schedules that were created are stratified by location (Guam, Saipan) and use blocked randomization, with block sizes of 4, 6 and 8 [29], to avoid a large imbalance in size between the study groups at any time. Separate randomization schedules are created for individuals and for groups of individuals to balance this factor between intervention and control groups. The randomization lists that were generated by computer are placed in opaque envelopes by the Biostatistics Core staff not involved with participant enrollment and study implementation. A separate group of research staff open the envelopes at enrollment wherein participants are informed of their random assignment to intervention or control. The statisticians performing the interim data analysis are blinded to the assignment as groups are labeled A and B.

2.4. Control condition

The control condition consists of a minimal intervention, a single booklet, specifically created for this study and designed to encourage AN/BQ cessation. The booklet entitled “Quitting Betel Nut” provides general information on AN/BQ, risks associated with AN/BQ chewing including graphical images, cessation strategies modeled after tobacco cessation including tips and heuristics, and study contact information.

Participants assigned to the control condition meet with study staff to receive the AN/BQ cessation booklet, for administration of the three study assessments, and for the collection of saliva samples. The survey assessments and saliva collections occur on the same time schedule as for intervention condition participants (baseline, approximately 22 days post-baseline, and six months post-baseline). The surveys administered to control condition participants omit questions regarding the intensive AN/BQ cessation program. The intervention and control condition participants receive compensation for their time.

2.5. Intervention condition

The general framework employed to guide the intervention is cognitive-behavioral therapy [30], which is goal-oriented and problem-focused. The goal of this intervention is to help AN/BQ chewers to quit chewing using structured sessions. The cognitive component addresses chewers’ attitudes and beliefs about AN/BQ chewing – for example, by educating them about how AN/BQ increases their risk for developing oral cancer. Preliminary data revealed that most participants initially underestimated such negative health effects of AN/BQ use [28]. The behavioral component of the intervention aims to replace chewing-promoting behaviors with behaviors that are more conducive to quitting AN/BQ and staying quit, such as identification and management of triggers, making lifestyle changes that support quitting (e.g., increasing time spent in places where chewing is forbidden, making AN/BQ less readily available to oneself), and preparing responses for social situations where they may experience peer pressure to chew.

The structure of the BENIT is modeled after a specific group-based cognitive-behavioral smoking cessation program [31] for its well-established and evidence-based practices. A group intervention format was selected because past research on smoking cessation revealed that group-based treatment was as effective as individual counseling while being more time- and cost-effective [32]. The intervention consists of a 22-day, five-session support and informational group program designed to help AN/BQ chewers to quit chewing. An individual-based option is available for chewers preferring to participate alone. The meetings are approximately 1 h in length and are conducted by trained research staff who are knowledgeable about the local culture, including AN/BQ use. Surveys are administered prior to the sessions at the first and last meeting, as well as six months after the last meeting. At most sessions, handouts are provided and topical “homework” is distributed. The homework assignments reinforce the themes emphasized during the therapy sessions. Table 2 provides an overview of the intervention content by session.

Table 2.

Description of the intervention sessions of the areca nut/betel quid cessation study known as the Betel Nut Intervention Trial.

| Session | Day | Description of Session |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| 2 | 8 |

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| 3 | 15 |

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| 4 | 18 |

|

| ||

| ||

| 5 | 22 |

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

The intervention procedures for Guam and Saipan are the same. Intervention facilitators employ checklists of intervention components to assess and reinforce treatment fidelity at each intervention session [33]. The intervention sessions are recorded and reviewed by the research investigators. Immediate feedback is provided to the facilitators.

The intervention groups may include up to 10 participants. The intervention sessions begin almost immediately, within a week of enrollment, regardless of the number of participants in the group. The availability of multiple facilitators allows for multiple intervention sessions to occur simultaneously. To minimize loss to follow-up, any participant delayed more than one month may re-enroll in the intervention. Re-enrollments do not change the total accrual into the trial.

2.6. Survey assessments and saliva collection

Survey questionnaires are administered at three sessions. In the first session, baseline surveys comprise questions on demographics, current chewing behavior, chewing history, reasons for chewing [7], AN/BQ composition, and AN/BQ dependency items [34,35]. Saliva samples are collected at this time. The first follow-up survey is administered during the 22-day group session for intervention group participants. Participants provide information regarding their intervention compliance, including whether they have attempted to quit chewing AN/BQ since starting the intervention program; their current chewing status (chewer or ex-chewer); how much they have cut down their chewing; how many group sessions they attended (as well as why they did not attend, if they missed one or more sessions); and AN/BQ composition (if still chewing). They are also asked several questions to measure their satisfaction with the cessation program and its format. Saliva samples are collected for a second time. Six months post-baseline, study staff arrange to meet with participants to complete a final survey assessment. Participants are asked again to evaluate the program, as well as follow-up questions regarding their current chewing status and AN/BQ composition. Saliva samples are collected for a final time. Individual in-person meetings are arranged with control group participants 22 days and 6 months after randomization, and the same surveys are administered, except for the program satisfaction questions, and saliva samples are collected.

2.7. Data management

The Biostatistics Core oversees data management. Participant attendance is being tracked in a system created in Microsoft Excel. Questionnaire data are being double-entered through Microsoft Excel. The data are cleaned for consistency and range checks. The data are all stored on security, password protected computers at the University of Guam and University of Hawaii Cancer Center. Once the trial results are published, access to the data can be requested through the University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership data sharing plan, given compliance with ethical review requirements.

2.8. Bio-verification of self-reports

The saliva samples (ca. 1–2 mL) collected during the survey assessments are to be used to verify cessation self-reports. Saliva samples are collected via “passive drool” in 20 mL conical polypropylene tubes which are initially stored at −20OC, then shipped to the University of Hawaii Cancer Center. After arriving in Hawaii, samples are stored at the Analytical Biochemistry Shared Resource at −80OC until analysis. Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry is used to analyze levels of salivary markers of AN exposure, namely the most predominant alkaloids specific for Areca catechu including arecoline, arecaidine, guvacoline and guvacine [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. To verify self-reports of BQ abstinence, cut-offs for levels of alkaloids specific for ANs are set as follows: arecoline 60 ng/mL, arecaidine 10 ng/mL, guvacoline 20 ng/mL, and guvacine 6 ng/mL. Levels above these values indicate evidence of recent BQ consumption. Participants whose saliva tests reveal values above the specified cut-offs will be considered current chewers for the purposes of bio-verified outcomes. Cotinine levels are being used to verify BQ use with tobacco. All of one individual's samples are being assayed in one batch and the results are being compared to self-reports of recent chewing behavior, amount and recency, to assess agreement between the two sources. These data allow for further refinement of AN biomarkers and enhancement of future AN biomarker technology.

2.9. Evaluation of effectiveness

The goal of the analysis is to determine if the proposed intervention strategy affects cessation of BQ chewing. Information on chewing behavior is collected at baseline, at 22 days, and at 6 months for the intervention and control conditions. The assessment of the efficacy of the cessation program is by estimation and comparison of cessation prevalences over time, defined as the proportion who are not chewing BQ. The plan for a logistic mixed model [38] is to compare the cessation status between randomization groups at 22 days and 6 months, accounting for the correlation structure for the repeated (correlated) measures within each individual and the clustering of participants randomized as groups. The independent variables include randomization group (defined as intent-to-treat), time (parameterized as two indicator variables), location (Guam/Saipan), and interaction terms between group and time. Potential confounders to be added to the model include sex, ethnicity and age. The t-tests for the interaction term at 22 days and 6 months are the respective tests of short-term and long-term efficacy. Note that the t-test with degrees of freedom >30, as is the case here, is equivalent to a z-test; therefore, the p-value from the t-test is compared to the interim analysis critical values. Statistics of interest from the model include the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) comparing randomization groups, and the covariate-adjusted probabilities of cessation and their 95% CIs, predicted by group from the model. Analysis performed within subgroups, such as location (Guam/Saipan), randomization type (individual/group) and baseline AN/BQ composition, provides information on whether the intervention was more effective in select groups. Treatment is additionally modeled as the number of sessions attended to determine if the program was more effective in more compliant participants. The mixed model uses all available data at each time point. If there is evidence of non-random missingness, such as by differential drop-out between groups, multiple imputation [39] is planned to adjust for any bias caused by missing data patterns. A secondary analysis using a linear mixed model allows for the estimation, and comparison between randomization groups, of the number of AN/BQ chewed over time, overall and by composition, to determine if groups reduced their use and whether the intervention group had larger reductions.

Plans for investigating self-reported AN/BQ use and saliva values include using agreement measures, such as Kappa statistics [40], and the stated biomarker cut-offs for recent chewing. Self-report of the addition of tobacco to the quid allows for a comparison with cotinine levels detected in saliva collected.

3. Discussion

The rationale and design of the BENIT are described in this paper. The findings of this clinical trial will have global implications, especially for the 600 million people worldwide estimated to chew AN or BQ [3].

The BENIT offers a few notable innovations. Foremost, the BENIT is the first randomized cessation trial under study that focuses exclusively on AN/BQ. It draws from a well-established and evidence-based model of tobacco cessation. Other AN/BQ interventions are limited to an education awareness campaign (Butt, NCT03418506) and the treatment of oral cancer (Hasan, NCT03638622) and oral submucous fibrosis (Sethi, NCT02639897). Second, the BENIT offers group and individual enrollment. The group-level option lends a social support structure to families or friends who want to quit, while the individual-level option preserves anonymity among individuals and “closet” chewers. Finally, self-reports of AN/BQ cessation in the BENIT will undergo bio-verification, using the most relevant salivary biomarkers of the most predominant areca and tobacco alkaloids for this purpose.

Despite the global prominence of AN as the fourth most consumed psychoactive substance in the world, no systematic research on AN/BQ cessation programs exists. This is striking, given the voluminous research literature on cessation of other addictive carcinogens such as tobacco and alcohol. AN/BQ chewing affects a large population of people, many of whom live in low and moderate income countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the current intervention trial focuses on Guam and Saipan, it has the potential for greater regional and global importance. Thus, increased attention on the development of AN/BQ cessation programs is long overdue.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Guam institutional review board (CHRS#16-04, initial approval). Research staff obtain written consent from all participants prior to enrollment.

Availability of data and materials

The data are accessible only to the BENIT analytic team in order to produce the final reports and publications. Once the trial results are published, access to the data can be requested through the University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership data sharing plan, given compliance with ethical review requirements. Contact the corresponding author at paulinoy@triton.uog.edu.

Author's contributions

YCP developed the initial manuscript draft. Additionally, YCP, TAH, AAF, PP and CTK developed the study design and methods. LRW and GB provided statistical support. PPS, JSNC, LFT and AJM assisted with data collection. All authors participated in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following individuals and organizations for their contributions to the BENIT: Kennedy Benjamin, Mamie Ikeda, Claudine Atalig, Janet Santos, Arlene Sibetang, Dr. Robert Gatewood, Dr. Kenneth Pierson, Jonas Macapinlac, Michelle Conerly and Kyle Santos, for assistance with the production of the BENIT commercials; Dr. John Moss, Casierra Cruz and Tayna Belyeu-Camacho for assistance with the initial BENIT infrastructure; Elua Mori and Chandra Legdesog for assistance with data collection; Mr. Juan Babauta, the Commonwealth Cancer Association, the Guam Comprehensive Cancer Control Coalition and the U54 UOG/UHCC Communication Outreach Core for assistance with recruitment and referrals; and Jennifer Lai for assistance with manuscript edits and submission. This work is supported by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership to Advance Cancer Health Equity, Grant U54CA143728 (University of Guam) and Grant U54CA143727 (University of Hawaii Cancer Center).

References

- 1.Staples G.W., Bevacqua R.F. Traditional Trees of Pacific Islands: Their Culture, Environment, and Use. Par; 2006. Areca catechu (betel nut palm) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall M. An overview of drugs in Oceania: relations of substance. In: Lindstrom L., editor. Drugs in Western Pacific Societies. University Press of America; Washington, D.C.: 1987. pp. 13–49. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta P.C., Warnakulasuriya S. Addiction Biology. 2002. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulino Y.C., Hurwitz E.L., Ogo J.C., Paulino T.C., Yamanaka A.B., Novotny R. Epidemiology of areca (betel) nut use in the Mariana Islands: findings from the University of Guam/University of Hawai’i cancer center partnership program. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(Pt B):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CNMI Department of Commerce . 2010. The Final Report on the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams S., Malik A., Chowdhury S., Chauhan S. Sociocultural aspects of areca nut use. Addiction Biol. 2002;7:147–154. doi: 10.1080/135562101200100147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little M.A., Pokhrel P., Murphy K.L., Kawamoto C.T., Suguitan G.S., Herzog T.A. The reasons for betel-quid chewing scale: assessment of factor structure, reliability, and validity. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:62. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulino Y.C., Novotny R., Miller M.J., Murphy S.P. Areca (betel) nut chewing practices in Micronesian populations. Hawaii J. Public Health. 2011;3:19–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghani W.M., Razak I.A., Yang Y.-H., Talib N.A., Ikeda N., Axell T. Factors affecting commencement and cessation of betel quid chewing behaviour in Malaysian adults. BMC Publ. Health. 2011;11:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu N.S. Effects of Betel chewing on the central and autonomic nervous systems. J. Biomed. Sci. 2001;8:229–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02256596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu N.S. Neurological aspects of areca and betel chewing. Addiction Biol. 2002;7:111–114. doi: 10.1080/13556210120091473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y.-J., Peng W., Hu M.-B., Xu M., Wu C.-J. The pharmacology, toxicology and potential applications of arecoline: a review. Pharm. Biol. 2016;54:2753–2760. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2016.1160251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IARC . 2004. Betel-quid and Areca-Nut Chewing and Some Areca-Nut Derived Nitrosamines. Various. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharan R.N., Mehrotra R., Choudhury Y., Asotra K. Association of Betel nut with carcinogenesis: revisit with a clinical perspective. PloS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shafique K., Zafar M., Ahmed Z., Khan N.A., Mughal M.A., Imtiaz F. Areca nut chewing and metabolic syndrome: evidence of a harmful relationship. Nutr. J. 2013;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan M.S., Bawany F.I., Ahmed M.U., Hussain M., Khan A., Lashari M.N. Betel nut usage is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease. Global J. Health Sci. 2014;6:189–195. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n2p189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg A., Chaturvedi P., Gupta P.C. A review of the systemic adverse effects of areca nut or betel nut. Indian J. Med. Paediatr. Oncol. 2014;35:3–9. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.133702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . 2010. ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winstock A.R., Trivedy C.R., Warnakulasuriya K.A.A.S., Peters T.J. A dependency syndrome related to areca nut use: some medical and psychological aspects among areca nut users in the Gujarat community in the UK. Addiction Biol. 2000;5:173–179. doi: 10.1080/13556210050003766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirza S.S., Shafique K., Vart P., Arain M.I. Areca nut chewing and dependency syndrome: is the dependence comparable to smoking? a cross sectional study. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Pol. 2011;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benegal V., Rajkumar R.P., Muralidharan K. Does areca nut use lead to dependence? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;9:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehrtash H., Duncan K., Parascandola M., David A., Gritz E.R., Gupta P.C. Defining a global research and policy agenda for betel quid and areca nut. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e767–e775. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulino Y.C., Hurwitz E.L., Warnakulasuriya S., Gatewood R.R., Pierson K.D., Tenorio L.F. Screening for oral potentially malignant disorders among areca (betel) nut chewers in Guam and Saipan. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J. second ed. L. Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiore M., Jaén C., Baker T., Al E. 2008. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen J., Bahendeka S.K., Whyte S.R., Meyrowitsch D.W., Bygbjerg I.C., Witte D.R. Household and familial resemblance in risk factors for type 2 diabetes and related cardiometabolic diseases in rural Uganda: a cross-sectional community sample. BMJ Open. 2017 Sep 21;7(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S., Crespi C.M., Wong W.K. Comparison of methods for estimating the intraclass correlation coefficient for binary responses in cancer prevention cluster randomized trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2012 Sep;33(5):869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss J., Kawamoto C., Pokhrel P., Paulino Y., Herzog T. Developing a betel quid cessation program on the island of Guam. Pacific Asia Inq Multidiscip. Perspect. 2015;6:144–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman L., Furberg C., DeMets D., Reboussin D., Granger C. Springer International Publishing Switzerland; New York: 2015. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins K.A., Conklin C.A., Levine M.D. 2008. Cognitive-behavioral Therapy for Smoking Cessation: A Practical Guidebook to the Most Effective Treatments. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown R.A. Intensive behavioral treatment. In: Barlow D.H., editor. The Tobacco Dependence Treatment Handbook: A Guide to Best Practices. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. pp. 118–177. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stead L.F., Lancaster T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005;18 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001007.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borrelli B. The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. J. Publ. Health Dent. 2011;71(Suppl 1):S52–S63. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee C.Y., Chang C.S., Shieh T.Y., Chang Y.Y. Development and validation of a self-rating scale for betel quid chewers based on a male-prisoner population in Taiwan: the Betel Quid Dependence Scale. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herzog T.A., Murphy K.L., Little M.A., Suguitan G.S., Pokhrel P., Kawamoto C.T. The betel quid dependence scale: replication and extension in a Guamanian sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franke A.A., Mendez A.J., Lai J.L., Arat-Cabading C., Li X., Custer L.J. Composition of betel specific chemicals in saliva during betel chewing for the identification of biomarkers. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;80:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franke A.A., Li X., Lai J.F. Pilot study of the pharmacokinetics of betel nut and betel quid biomarkers in saliva, urine, and hair of betel consumers. Drug Test. Anal. 2016;8:1095–1099. doi: 10.1002/dta.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fitzmaurice G., Laird N., Ware J. 2011. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little R.A., Rubin D.B. second ed. 2002. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleiss J., Levin B., Paik M. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2003. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are accessible only to the BENIT analytic team in order to produce the final reports and publications. Once the trial results are published, access to the data can be requested through the University of Guam/University of Hawaii Cancer Center Partnership data sharing plan, given compliance with ethical review requirements. Contact the corresponding author at paulinoy@triton.uog.edu.