Abstract

In this digital era, transmitting data through a computer network has become common. Moreover, some applications have also been developed to do it. Nevertheless, users may not be aware of the security aspect of this data transmission, which can lead to disclosing this private message. In a case when a sensitive message is the object to transmit, a security mechanism should be applied. Data hiding is one of the methods introduced to work for this issue. In this algorithm, the message is embedded into the cover, such as an audio file, before being transmitted; on the other side, the recipient extracts it. However, the size of the message and the quality of the resulted stego data are still challenging. In this paper, we focus on these two problems by considering some factors: embedding space, embedding process, reducing, and smoothing steps. Firstly, the audio signal is discretized to obtain audio samples. Next, these samples are interpolated to provide spaces for hiding the secret. Considering that the quality of the generated stego audio is likely to drop, reducing and smoothing steps are designed. The experimental results show that this approach can improve the quality of the stego based on the specified payload capacity. That is, there is an increase in PSNR value of at least 10 dB, depending on the payload size and the methods.

Keywords: Computer science, Data embedding, Data protection, Data hiding, Information security, Multimedia security

Computer science; Data embedding; Data protection; Data hiding; Information security; Multimedia security

1. Introduction

For some decades, information and communication technology has been seeing significant growth. This development has made it easy for people to transmit data between devices anywhere and anytime. Moreover, at present, limited devices such as smartphones can process data much more quickly than before. Nevertheless, this advancement may attract illegitimate users who actively attack the computer system [1], for example, by intercepting the transmitted data. This activity causes a security problem for secret and private information such as financial and medical data.

Some methods have been proposed to overcome this security issue that can be grouped into a network and information security, which complement each other. While the former can be implemented by designing a suitable intrusion detection system (IDS), honeypot, or other security tools; security tools can be designed to conceal the secret. This concealment can be achieved in some ways, including encrypting [2] or embedding the secret in a medium; this is called a data hiding method [3]. In this research, the terms hiding and embedding have the same definition.

In its design, data-hiding may use either image [4], audio [5], video [6], or even text [7], [8] to carry the secret. As predicted, each medium, called the carrier or cover, has its own characteristics. For example, an image concerns visual quality, while audio focuses on the voice. In the data-hiding terminology, quality is defined as the similarity level of the carrier between, before, and after the secret is embedded, regardless of the carrier being used. In fact, research in data-hiding is mostly carried out by using the image [3], [9]; on the contrary, that exploring audio is only a few, and even less than video. Furthermore, the embedding process can be performed either in the spatial domain, where the secret is directly hidden in the cover, or in the frequency domain, wherein the cover must be transformed before the embedding process, for example, by employing Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [10] or Wavelet Transform [11].

Spatial domain-based data-hiding methods have been popular to protect secret data. Despite its limitation in generating excellent stego quality, this method may accommodate more secrets than that of the transformed-based algorithm. Therefore, improving the visual or audio quality is still a challenge. Additionally, those two algorithms may be implemented in a different environment, depending on the purpose of the required system.

In general, the previous algorithms can be classified in some groups, including [12]: LSB modification, histogram shifting (HS), pixel value difference (PVD), and difference expansion (DE). Two primary factors are still a challenge in the data-hiding field: the capacity of the secret being embedded in the cover, and the quality of the resulted stego file [13]. In this paper, we work on those two problems by focusing on the spatial domain and taking audio as the cover. Here, the embedding is implemented in the generated samples. Moreover, the difference between the stego audio and its corresponding file (cover) is reduced.

The remaining sections of this paper are structured, as follows. Section 2 describes the previous works of data-hiding. Section 3 explains the proposed method, followed by its experimental results and analysis in Section 4. The comparison of the method is provided in Section 5. Finally; the conclusion is presented in Section 6.

2. Data-hiding methods

Overall, the data-hiding method can be illustrated in Fig. 1, where an image or audio can be taken as the cover. The hiding is done by the sender before the data transmission starts. On the other side, the recipient receives the stego and extracts it to obtain the secret. Slightly different from the spatial-based approach, in the frequency-based method, the cover must be first transformed before being embedded. In [14], Lei et al. make use of Quaternion Wavelet Transform to achieve robustness and an appropriate capacity of the secret. In their research, the transformation is combined with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and chaotic signals to improve the performance further. In many situations, the recipient also reconstructs the original medium (cover). In this case, the reversibility of the cover is a crucial factor, and the corresponding algorithm is classified in Reversible Data Hiding (RDH). Therefore, both the secret and the cover can be obtained without losing information. Furthermore, RDH is one of the appropriate methods to use for providing privacy of the users, protecting copyright, and authenticating users.

Figure 1.

An example of the general process in hiding the secret, where a cover image or audio is implemented.

Generally, a data hiding algorithm is independent of the types of cover. Nevertheless, an algorithm cannot be just implemented on different media. So, even though the proposed method explores audio as the cover, in this section, we review both image- and audio-based algorithms. Moreover, many embedding algorithms are initially developed by using an image. One of the popular data-hiding methods, Difference Expansion (DE) [15], which was initially introduced for an image, has been further developed for audio [16]. This algorithm ([15]) was the primary reference for the following data-hiding research. In practical terms, DE is designed for 2D, which represents the characteristic of an image. In order to manipulate this construction, audio samples (which consist of 1D data) are formed as two rows called bigits. By using the same type of medium, Andra et al. [5] improved its capability. In their research, intelligent partitioning combined with multilayer embedding was applied to the embedding process. It is claimed that their result was better than the previous method.

In 2015, Joong and Yoo [17] proposed a method by exploring the use of interpolation and the Least Significant Bit (LSB) modification. In their research, which utilized an image, they found that the algorithm is better at hiding the secret. In other research, Zhang et al. [18] generated prediction errors for the histogram, which was then shifted. Here, both the cover and the secret can successfully be retrieved from the stego. Echo hiding is the topic that is investigated in [16]. In order to ensure that only legitimate users can recover the hidden data, the shared-secret algorithm is applied in [19]. In this research, the number of users who are able to obtain the data can be determined according to the specified parameters. This system may increase the security of the secret since the extraction should be carried out by some users concurrently.

By manipulating the difference between values (e.g., a pixel of an image, a sample of audio) and a modulus function, Maniriho and Ahmad [20] embed the secret. In that research, they further explore the use of both positive and negative difference values, unlike previous research. By employing this characteristic, they can raise the quality of the stego data from the existing method. In the case video is utilized as the cover, both image and audio are often used at the same time [21]. It means that the method combines the image- and audio-based data-hiding. As a result, the capacity of the secret significantly goes up; however, the quality of the stego drops.

In [9], Bobeica et al. implemented the Prediction Error Expansion (PEE) on audio RDH, which was initially introduced for image [22]. Their research intends to find an optimal threshold value to specify which samples should be used to hold the secret, along with the prediction error value. Indirectly, the threshold also affects the value of the expanded samples. The predictor value itself may consider a relatively small or large number of neighboring samples, as in [23] and [24], respectively.

Jung and Yoo [25] propose to expand the cover before the embedding process starts. It is intended to accommodate more secrets than the original cover can hold. While this algorithm is implemented in an image, in the next research, Ahmad and Fiqar [26] extend this method to an audio file. Some additional steps have been updated to make it able to maintain the quality of the respective stego. For evaluation, various types of files have been applied; their results reflect that the proposed method is suitable to implement.

Variations of the methods have also been introduced by combining them with other methods, such as secret sharing [27], homomorphic encryption [28], [29], multiple predictors [30], and the encrypted-mesh model [31]. Furthermore, Hua et al. [32] analyze some possible attacks on the resulting stego data and explain other aspects of the existing algorithms, for example, commercialization and its patent application. Even though this is intended for watermarking, which has a purpose that is slightly different from data hiding, the overall analysis and method are the same. Overall, those methods are to prevent either active or passive attacks [33].

3. Secret data protection

This proposed method is developed based on those previous works, especially [17], [25]. The algorithm consists of two main processes: embedding and extraction. In the embedding process, the sender puts the secret in the cover which is then extracted by the receiver to obtain both the original cover and the secret, by reversing the embedding step. The overall process of the embedding can be presented in Fig. 2. In general, the audio cover is sampled before being normalized and interpolated. At the same, time, the secret is binarized and segmented before being embedded. Next, some finishing steps are applied to have the stego audio, which includes smoothing to reduce the possible noise.

Figure 2.

Embedding process.

3.1. Embedding process

Before being embedded, the cover which is a continuous signal must be discretized to have audio samples. For this purpose, the audio signal is converted into 16-bit audio samples (see Fig. 3 for the example). In this pre-embedding process, we consider these original samples, which are represented by . Like [26], [25], this discrete signal is interpolated to make more spaces within the signal. In this research, linear interpolation is applied (see (1)), to obtain , whose illustration is provided in Fig. 4. Here, and respectively represent the magnitude of the original and the corresponding samples generated by the interpolation process in a group comprising and samples, where n is the index. It is worth noting that the index (location) of the original and interpolating samples is consecutively odd and even. After the interpolation is applied, a vector of samples is obtained as the combination of and . Supposed there are 3 samples as follows: and . The generated vector of samples is .

| (1) |

Figure 3.

Audio sampling.

Figure 4.

Interpolating sample.

The space of the embedding is allocated by grouping some consecutive original samples, called segment (k), which in this research it is set as either 2, 3, 4, or 5. From each segment, we find both the highest () and the lowest () values of jth segment by using (2) and (3), respectively. Here, is the ith original sample in a segment. Next, the average () of these two values and the respective sample of jth segment is calculated by using (4).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

By taking , from the vector , it is found that:

Therefore, the average of the samples in each segment is:

There are some conditions which determine the space of embedding () of segment j. That is, it depends on the value of the corresponding sample and its neighbors. If the sample is the last one in the cover, then (5) is applied. Otherwise, the value of is determined by the comparison between and . That is, (6), (7) or (8) is employed if , or , respectively.

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

The value of is then used for determining the number of bits () which can be embedded to the corresponding sample by using (9).

| (9) |

By using (5)-(9), we find that and . Therefore, the total of bits to be embedded in and are and , respectively. It can also be inferred that the number of bits per sample does not have to be the same. So, this value varies depending on the other sample values in the corresponding segment.

Suppose the secret of being protected is . This payload is split according to the values of and . Based on them, the first and second groups of the secret are respectively:

This secret group of bits () is reduced ith times to achieve a simpler form of the corresponding secret (). To this purpose, (10) is implemented whose output relies on the value of the secret-whether it is even or odd. This process can be repeated until the output is either 0 or 1. The resultant value is then used in the extraction process by the receiver. For a simple example, here we specify that , so and .

| (10) |

Let and be the jth interpolating sample before and after being embedded by the secret. The group of bits that has been allocated is added to that interpolating sample, as depicted in (11). It is shown that the original sample () does not hold the hidden data. Therefore, their value does not change at all.

| (11) |

In this example, the generated values are:

It is shown that there is an increase in the interpolating sample, from 83 to 88 and from 88 to 91, for the first and the second samples, respectively. This difference causes noise, which disturbs the quality of the resulted audio. Additionally, this deviation may indirectly attract the attention of attackers to carry out illegal access. Therefore, we believe that this noise should be further reduced to as low as possible. For this purpose, the reducing process, called reduced difference (RD), is introduced. Generally, this process can be firstly presented in (12) - (14), where and are correspondingly the first and the second temporary values, is the jth smoothed embedded sample, and is the final embedded sample after being smoothed. This smoothing process can be performed several times according to the required quality.

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

For the next extraction process, the sender should send some information taken from (13) and (14) to the receiver. This information can be summarized in (15), which constructs a set of key for the ith smoothing step of the jth sample.

| (15) |

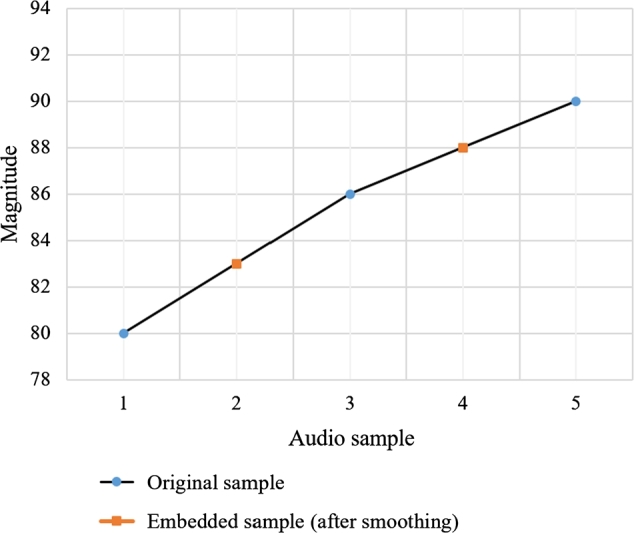

By using this smoothing step, we have that , for the first sample, and , for the second sample. Correspondingly, the following values are obtained: and . Therefore, after the first smoothing iteration, the embedded samples are and . This illustration is presented in Figs. 5, 6 and 7. It is shown that an iteration has made the embedded samples smoother than before. From the example, we can summarize the audio samples as follows:

-

•

Original samples

-

•

Interpolating samples

-

•

Combined samples

-

•

Embedded samples (non-smoothing)

-

•

Combined samples (non-smoothing)

-

•

Smoothing embedded samples

-

•

Stego samples

-

•

Smoothing key

Figure 5.

Original and interpolating audio samples.

Figure 6.

Embedded sample before smoothing.

Figure 7.

Embedded sample after smoothing.

Those samples can be further smoothed by carrying out this step several times, depending on the specified level. It can be inferred that doing more smoothing steps result in reducing the noise. Nevertheless, doing this stage may take additional time, even though it is not significant. In the case that the smoothed signal has reached the optimal value, applying further smoothing does not change the result, as shown in this smoothing example where and cannot be further optimized.

In more detail, the comparison of the proposed and existing base methods ([25], [17], [26], [5], [9]) is presented in Table 1. It is shown that this method adds steps that previously did not exist, for example, the reducing step. Moreover, the embedding process is simpler than the one in [26].

Table 1.

| Parameters | Method of [25] | Method of [17] | Method of [26] | Method of [5] | Method of [9] | Proposed Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Medium | Image | Image | Audio | Audio | Audio | Audio |

| Interpolation method | Neighbor mean interpolation (NMI) | NDDI (taken from [34]) | None | None | Linear (see (1)) | |

| Size of payload | Dynamic | Static | Dynamic | Static | Static | Dynamic |

| Ni = ⌊log2|dn|⌋ | (see (9)) | |||||

| – | (see (4)-(8)) | |||||

| Embedding | Improved RDE | (see (11)) | ||||

| Reducing | None | None | None | None | None | (see (10)) |

| Smoothing | None | None | Embedding: | None | None | (see (12), (13), (14), (16)) |

| Extraction: |

3.2. Extraction process

In the extraction process, the cover medium and the secret data are taken from the stego. Principally, obtaining the secret is compulsory, while that of the cover is optional, depending on the reversibility of the method. Nevertheless, in this research, we work to extract those two types of data. This process is generally performed in the reverse order of the embedding process, as provided in Fig. 8. It is depicted that the normalization and smoothing are applied to the stego file, similar to the embedding step. Two parallel processes are designed to obtain both the original cover and the secret. This has made each step does not depend each other, which may speed up the processing time and reliability of both cover and secret data.

Figure 8.

Extraction process.

According to the stego audio resulting from the embedding step, the receiver has . Based on the fact that the odd-indexed sample is the original one, the receiver obtains and . So, the original samples are interpolated by using (1) results in and . These values are then used to obtain and by reversing the smoothing steps in (12)-(14). For this purpose, we have (16) to generate and . Therefore, those non-smoothing samples can be depicted as .

| (16) |

Next, by inverting (11) we have and . Consecutively, these values are proceeded by (10). At this step, the payload and are held by considering the corresponding number of bits and which have been specified in (9). It is worth noting that the receiver is able to calculate these values. This means that the sender does not have to transmit them.

Finally, the whole payload is extracted to have . Correspondingly, the original audio sample is obtained by taking . Therefore, both the payload and the cover can be thoroughly reconstructed the same as the original values. It means that this method is reversible.

4. Experimental results

In order to evaluate the performance of the proposed method, we measure two values similar to other research such as in [26]. The first is the value of PSNR (peak signal to noise ratio) to find the similarity level of the cover between before and after the payload is embedded. Represented in dB (decibel), it is intended that this stego file is not much different from the original cover, which may attract the suspicion of the public. So, the better the quality, the more the similarity. The PSNR value itself is calculated by using (17), where MAX is the maximum value of the samples, and the corresponding MSE (mean-squared error) is defined in (18). Because the audio is a 1D array (vector), the value of m is 1; while that of n depends on the number of the total samples. The second value is the amount of payload (in bits) which can be embedded to the cover without much affecting the cover. Higher capacity means that more secret data can be protected. These two values, however, are often inversely proportional. There is a trade-off between them.

| (17) |

| (18) |

Similar to [26], for this evaluation, audio files are taken from [35] comprising 15 files, from Audio1 to Audio15 (see Table 2) are used. This data set consists of 3 genres (i.e., Country-Folks, Classical, Pop-Rock), each of which contains five instruments play three seconds (i.e., Cello, Acoustic Guitar, Piano, Saxophone, Voice). The payload is randomly generated whose size is varied, from 1 kb to 100 kb, as presented in Table 3. The experiment is carried out in some scenarios as follows.

Table 2.

Audio Data Set for the Experiment.

| Cover No. | Audio cover | Genre, Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Audio1 | Country-Folk, Cello |

| 2 | Audio2 | Classical, Cello |

| 3 | Audio3 | Pop-Rock, Cello |

| 4 | Audio4 | Country-Folk, Acoustic guitar |

| 5 | Audio5 | Classical, Acoustic guitar |

| 6 | Audio6 | Pop-Rock, Acoustic guitar |

| 7 | Audio7 | Country-Folk, Piano |

| 8 | Audio8 | Classical, Piano |

| 9 | Audio9 | Pop-Rock, Piano |

| 10 | Audio10 | Country-Folk, Saxophone |

| 11 | Audio11 | Classical, Saxophone |

| 12 | Audio12 | Pop-Rock, Saxophone |

| 13 | Audio13 | Country-Folk, Voice |

| 14 | Audio14 | Classical, Voice |

| 15 | Audio15 | Pop-Rock, Voice |

Table 3.

Number of Bits Being Used in the Experiment.

| Payload no. | Size (kb) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 20 |

| 4 | 30 |

| 5 | 40 |

| 6 | 50 |

| 7 | 60 |

| 8 | 70 |

| 9 | 80 |

| 10 | 90 |

| 11 | 100 |

4.1. Size of segment

In this experimental scenario, the size of segments is evaluated, from to . We believe that this range represents the trend of possible values. It is found that in general, the bigger the size of segment results to a higher number of payload which can be held by the cover, as shown in Fig. 9. This graph shows that the pattern does not depend on the characteristics of the cover. Nevertheless, as predicted, the quality of the stego may decrease along with the increase of the corresponding capacity.

Figure 9.

The capacity of the payload with various sizes of segment.

It is known that more significant segments enlarge the number of samples to explore. This means that many sample values within segments are available. Consequently, the number of spaces can be used goes up. Contrarily, a smaller segment reduces the possible space. This condition affects the selection of the maximum and minimum values that their average along with the respective sample in the segment relies on.

Moreover, a segment overlaps with the next segment minus 1 sample. So, a sample may be used for several other segments depending on the size of the previously specified segment. In other words, multiple-embedding can be implemented in each segment, which results in improving its capacity.

4.2. Level of reduced payload

The effect of the reducing level is provided in Fig. 10 by setting its value from (not reduced) to , and . It is shown that the increase in PSNR value is proportional to that of reducing the level. Without applying the reduction before the embedding, the resulted PSNR is the lowest, and it rises according to the value of i. In general, there is an increase of about 5 dB in the PSNR value along with the increasing i.

Figure 10.

Average of PSNR for various audio covers with k = 2.

This figure also explains that greater payloads stored in the cover results in a lower stego quality. As predicted, there is a trade-off between those two factors. On average, raising the payload size from 1 kb to 100 kb decreases about 25 dB of the stego quality.

It is also found that extending the size of the payload leads to reducing the gap of the PSNR of the respective payload size. For example, the PSNR difference resulted by kb and kb is higher than that of kb and kb, and so on. It means that this method has more influence on the smaller payload than on the bigger ones. Therefore, increasing the capacity of payload to a certain size may not greatly reduce the quality of the resulted stego. In other words, this proposed method has a better effect on bigger secret data. It is likely that the secret is distributed evenly among the samples. According to our previous research [36], this condition is better than when most secrets reside in a small group of samples.

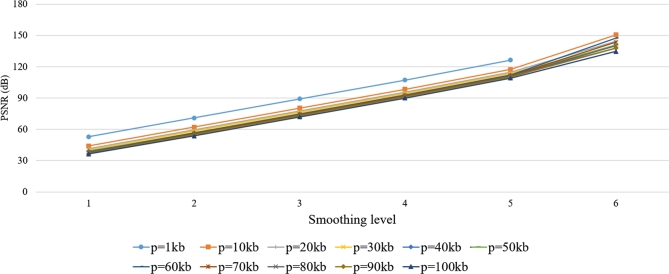

4.3. Level of smoothing

Here, the effect of the smoothing step on improving the quality of the resulted stego file is to be evaluated. In this scenario, we vary the smoothing level from 1 to 6. An example of the experimental result is provided in Fig. 11, where Audio1 is employed as the cover to carry various sizes of payload. It is shown that a single smoothing step may increase about 15 dB in PSNR value. Nevertheless, there is a maximum number of how many times the smoothing step can be applied. As presented in Fig. 11, by setting kb and applying the smoothing 6 times the PSNR value is infinite.

Figure 11.

The effect of smoothing on the PSNR of stego Audio1, where k = 2,i = 0.

Furthermore, when this smoothing step is applied to Audio2 as the cover, the infinite value of PSNR is achieved in the 4th iteration for all sizes of payload (see Fig. 12), which is better than that of Audio1. It means that by using Audio2, a fewer number of smoothing step has been able to make the stego similar to the cover.

Figure 12.

The effect of smoothing on the PSNR of stego Audio2, where k = 2,i = 0.

In more detail, it is also presented that smaller payload tends to achieve this condition with less smoothing steps than the bigger one, regardless of the characteristic of the cover. For example, different covers have been used in Fig. 11 and Fig. 13. It is shown that the payload kb takes 6 and 3 times, respectively, lower than others. This is consistent with the results of the previous analysis.

Figure 13.

The effect of smoothing on the PSNR of stego Audio13, where k = 2,i = 0.

4.4. Effect of genres

In this scenario, we evaluate the effect of the audio genre on the quality of the stego. For this purpose, we measure the PSNR of various sizes of the payload by setting the parameters as minimum as possible, i.e., , without payload reduction and single smoothing step. From the experimental results provided in Fig. 14, it is found that (Country-Folk, Voice) is the highest, followed by (Classical, Cello), (Classical, Saxophone), and (Classical, Acoustic guitar). On the other hand, Pop-Rock combined with various instruments, produces low PSNR.

Figure 14.

The effect of genre of audio cover on the PSNR of stego, where k = 2,i = 0.

This PSNR measurement, in general, is inversely proportional to the capacity of the payload, as previously shown in Fig. 9. It is found that the level of differences between samples affects the PSNR value. This means that a lower difference maintains a higher PSNR level but a smaller size of the payload, and vice versa. Therefore, in the case that there are secret bits functioning as the main factors, Pop-Rock can be considered. Otherwise, Country-Folk or Classical is the best choice.

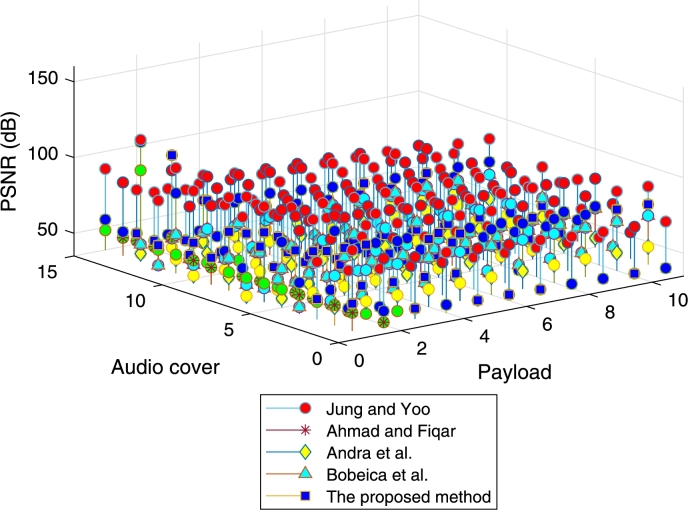

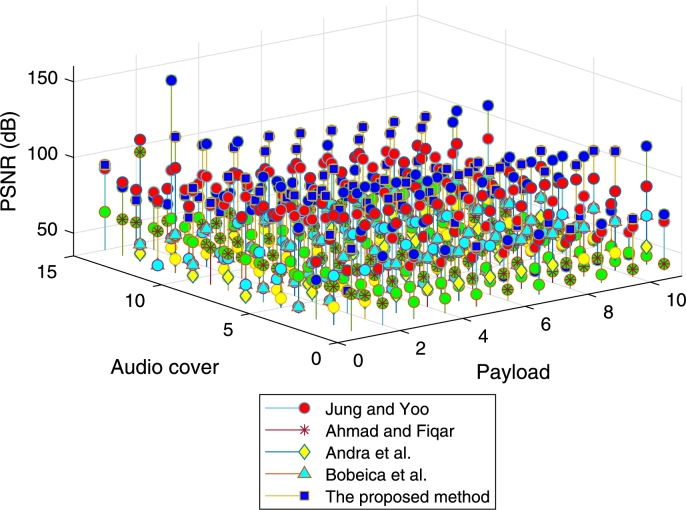

For the comparison, the methods of [25], [26], [5] and [9] are implemented whose results are provided in Fig. 15 and Fig. 16. They are evaluated by using the same experimental data. Respectively, those figures represent both [26] and the proposed method with single smoothing, while the others do not have it. As shown in Fig. 15, [25] has the best result. However, after being smoothed three times, the proposed method is superior in the most cover and payload size variations (see Fig. 16). At this stage, the stego quality of [26] is still relatively low, so that it is slightly higher than [5]. However, there is an increase in the quality level. On the contrary, the performances of [25], [5], and [9] are stable because they have no smoothing step as previously described. Moreover, finding an appropriate embedding threshold value in [9] is still a challenge, which affects the performance.

Figure 15.

Comparison between Jung and Yoo [25], Ahmad and Fiqar [26], Andra et al. [5], Bobeica et al. [9] and the proposed method, in terms of the quality with single smoothing.

Figure 16.

Comparison between Jung and Yoo [25], Ahmad and Fiqar [26], Andra et al. [5], Bobeica et al. [9] and the proposed method, in terms of the quality with three times smoothing.

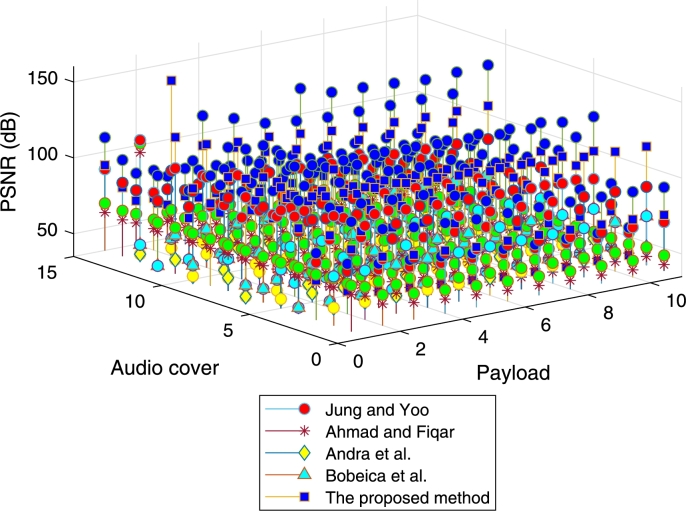

When the smoothing is applied four times, the proposed method is the best in all covers and payloads as depicted in Fig. 17. There is also a rise in the performance of [26]; nevertheless, its improvement cannot exceed that of [25]. It is predicted that by running more smoothing steps, [26] will be better than [25]. According to these results, it can be inferred that the proposed method requires less smoothing iteration than [26] to achieve the same level of the stego quality.

Figure 17.

Comparison between Jung and Yoo [25], Ahmad and Fiqar [26], Andra et al. [5], Bobeica et al. [9] and the proposed method, in terms of the quality with four times smoothing.

5. Discussion

As previously described, the research in audio-based data hiding methods is less than that of image-based [3], despite its possible superiority. The use of interpolation has extended the number of samples in the respective stego being generated. Consequently, the sampling rate may change; otherwise, the playing time of the audio is longer than the original audio cover. The advantage is that it is able to carry more bits, as previously described. This has been proven in the experimental results provided in Table 1. Furthermore, different interpolation algorithms likely have similar results, so in this research, we take the linear method due to its simplicity.

Dynamic payload capacity per sample has been useful to keep the quality of the stego audio. It is because not all samples on the cover have the same suitable number of bits to take. Some factors affect this characteristic, for example, the value of the previous and the next samples, as described in Section 3. Finding the details of these factors, along with their weight, is still challenging. That is, too many secret bits in a sample drop the quality, and too few bits cause the embedding process to fail.

To the best of our knowledge, only a few methods which design both reducing and smoothing steps in the embedding process. Indeed, these additional steps have made the process longer, but it is only in about a second which we may ignore it. Moreover, common devices are more advanced that the computation, in this case, is not the problem. In fact, reducing and smoothing have been able to increase the quality of the stego audio as provided in Section 4.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, audio-based data-hiding is proposed for protecting secret data. It is shown that without using a location map, this proposed method still works properly by taking the information about the sequence of the respective samples. Furthermore, the segmentation and smoothing steps designed for this scheme can increase the quality of the stego. It is also depicted that the genre of the audio has a significant effect on the performance or the secret size. According to the experimental results, this method is superior to existing ones. That is, it can obtain more than 90 dB, while others may not achieve the same performance. Moreover, the proposed method takes a smaller number of iteration than the previous research to have a certain stego quality level.

In the future, this method can be extended to raise the quality of the stego file further. This improvement may be made by more effectively specifying the size of the segments. That is, the size is dynamic according to some considered factors, including possible information should be stored. Additionally, the interpolation is explored to find the most appropriate one, considering the size and the number of the samples.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Tohari Ahmad: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Muhammad Hanif Amrizal: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Waskitho Wibisono, Royyana Muslim Ijtihadie: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education, the Republic of Indonesia under WCR research grant No. 718/PKS/ITS/2019.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Hadlington L. Human factors in cybersecurity; examining the link between Internet addiction, impulsivity, attitudes towards cybersecurity, and risky cybersecurity behaviours. Heliyon. 2017;3(7) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shareef F.R. A novel crypto technique based ciphertext shifting. Egypt. Inform. J. 2020 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y., Li X., Zhang X., Wu H., Ma B. Reversible data hiding: advances in the past two decades. IEEE Access. 2016;4:3210–3237. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Y., Wang C., Chen W., Lin F., Lin W. A novel data hiding algorithm for high dynamic range images. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2017;19(1):196–211. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andra M.B., Ahmad T., Usagawa T. Medical record protection with improved GRDE data hiding method on audio files. Eng. Lett. 2017;25(2):112–124. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramalingam M., Isa N.A.M. A data-hiding technique using scene-change detection for video steganography. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2016;54:423–434. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutub A.A-Z., Alaseri K.A. Refining Arabic text stego-techniques for shares memorization of counting-based secret sharing. J. King Saud Univ, Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Nofaie S., Gutub A., Al-Ghamdi M. Enhancing Arabic text steganography for personal usage utilizing pseudo-spaces. J. King Saud Univ, Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bobeica A., Dragoi I.C., Caciula I., Coltuc D., Albu F., Yang F. Capacity control for prediction error expansion based audio reversible data hiding. Proc. 22nd International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC); Sinaia, Romania; 2018. pp. 810–815. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manunggal T.T., Arifianto D. Proc. IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Singapore. 2016. Data protection using interaural quantified-phase steganography on stereo audio signals; pp. 3817–3821. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miri A., Faez K. Adaptive image steganography based on transform domain via genetic algorithm. Optik. 2017;145:158–168. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain M., Wahab A.W.A., Idris Y.I.B., Ho A.T.S., Jung K. Image steganography in spatial domain: a survey. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2018;65:46–66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain M., Wahab A.W.A., Anuar N.B., Salleh R., Noor R.M. Pixel value differencing steganography techniques: analysis and open challenge. Proc. IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan; Taipei, Taiwan; 2015. pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei B., Zhou F., Tan E., Ni D., Lei H., Chen S., Wang T. Optimal and secure audio watermarking scheme based on self-adaptive particle swarm optimization and quaternion wavelet transform. Signal Process. 2015;113:80–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian J. Reversible data embedding using a difference expansion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2003;13:890–896. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi K.-C., Pun C.-M., Chen C.L. Application of a generalized difference expansion based reversible audio data hiding algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2015;74(6):1961–1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung K., Yoo K. Steganographic method based on interpolation and LSB substitution of digital images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2015;74(6):2143–2155. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang W., Ma K., Yu N. Reversibility improved data hiding in encrypted images. Signal Process. 2014;94:118–127. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X., Weng J., Yan W. Adopting secret sharing for reversible data hiding in encrypted images. Signal Process. 2018;143:269–281. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniriho P., Ahmad T. Information hiding scheme for digital images using difference expansion and modulus function. J. King Saud Univ, Comput. Inf. Sci. 2019;31(3):335–347. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadek M.M., Khalifa A.S., Mostafa M.G. Video steganography: a comprehensive review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2015;74:7063–7094. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thodi D.M., Rodriguez J.J. Expansion embedding techniques for reversible watermarking. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007;16(3):721–730. doi: 10.1109/tip.2006.891046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huo Y., Xiang S., Liu S., Luo X., Bai Z. Reversible audio watermarking algorithm using non-causal prediction. Wuhan Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2013;18(5):455–460. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiang S., Li Z. Reversible audio data hiding algorithm using noncausal prediction of alterable orders. EURASIP J. Audio Speech Music Process. 2017;2017(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung K., Yoo K. Data hiding method using image interpolation. Comput. Stand. Interfaces. 2009;31(2):465–470. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad T., Fiqar T.P. Enhancing the performance of audio data hiding method by smoothing interpolated samples. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control. 2018;14(3):767–779. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutub A., Al-Juaid N., Khan E. Counting-based secret sharing technique for multimedia applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019;78(5):5591–5619. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiong L., Dong D., Xia Z., Chen X. High-capacity reversible data hiding for encrypted multimedia data with somewhat homomorphic encryption. IEEE Access. 2018;6:60635–60644. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang S., Luo X. Reversible data hiding in homomorphic encrypted domain by mirroring ciphertext group. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2018;28(11):3099–3110. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jafar I.F., Darabkh K.A., Al-Zubi R.T., Al Na'mneh R.A. Efficient reversible data hiding using multiple predictors. Comput. J. 2016;59(3):423–438. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang R., Zhou H., Zhang W., Yu N. Reversible data hiding in encrypted three-dimensional mesh models. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018;20(1):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hua G., Huang J., Shi Y.Q., Goh J., Thing V.L.L. Twenty years of digital audio watermarking-a comprehensive review. Signal Process. 2016;128:222–242. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ketshabetswe L.K., Zungeru A.M., Mangwala M., Chuma J.M., Sigweni B. Communication protocols for wireless sensor networks: a survey and comparison. Heliyon. 2019;5(5) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ Newton's divided difference interpolation formula. Available: (Accessed August 2018). [Online]

- 35.https://www.upf.edu/web/mtg/irmas/ IRMAS: a dataset for instrument recognition in musical audio signals. Available: (Accessed August 2017). [Online]

- 36.Ahmad T., Faruki J.N., Ijtihadie R.M., Wibisono W. Analyzing the effect of block size on the quality of the stego audio. Proc. the 5th International Conference on Science and Technology; Yogyakarta, Indonesia; 2019. [Google Scholar]