Highlights

-

•

An online MI intervention was recently developed to complement ICBT.

-

•

Intervention consists of videos, exercises, feedback to better simulate face-to-face MI.

-

•

Study evaluated intervention impact on motivation and perceptions of MI.

-

•

Ratings of motivation and MI perceptions significantly increased from pre- to post-MI.

-

•

Future research should explore longer term impact of online MI on ICBT.

1. Introduction

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an established treatment for the prevalent and debilitating conditions of anxiety and depression (Butler et al., 2006; World Health Organization, 2017). Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) has emerged as a comparable, effective approach for treating anxiety and depression with the additional benefits of overcoming many barriers to seeking mental health treatment (Newby et al., 2016; Andersson and Titov, 2014). Despite being accessible and effective, there continues to be room for improvement in ICBT in terms of client engagement, completion rates, and overall symptom reduction (Andersson et al., 2019; Edmonds et al., 2018). Research findings on the relationship between client characteristics and response to ICBT interventions remain inconclusive as to which factors influence a client's response to ICBT (Andersson, 2016). That said, Miller and Rollnick (2013) posit that an individual's degree of ambivalence to change, which is identifiable in the motivational language used by the client (Sijercic et al., 2016), contributes to varying treatment responses. Notably, researchers have found that client motivational language in early face-to-face CBT sessions for anxiety significantly predicts symptom change post-treatment (Lombardi et al., 2014; Sijercic et al., 2016; Westra, 2004). Motivational language encompasses expressions stated by the client in support of change, known as change-talk, as well as against change, referred to as counterchange talk (Hagen and Moyers, 2009).

MI was originally developed for use in face-to-face therapy for addressing poor treatment adherence for alcohol-related concerns (Miller, 1983). MI embraces a client-centered communication approach for strengthening client intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence to change (Riper et al., 2014; Sijercic et al., 2016). To date, MI has been shown to effectively change diverse health behaviours (e.g., alcohol and substance use, safer sex practices, eating disorders), across a variety of cultures, and with a wide age range of clients (Hettema et al., 2005; Rubak et al., 2005; Westra et al., 2011). Most recently, MI has been integrated with CBT to efficaciously treat anxiety concerns. In a meta-analysis on the integration of MI and CBT for anxiety disorders, Marker and Norton (2018) found that MI as a pre-treatment to CBT, as compared to CBT alone, had a moderate significant effect on symptom reduction (Hedges g = 0.59) and maintained outcomes at follow-up. Although research to date on the integration of MI and ICBT has been limited, the research thus far shows promise. Titov et al. (2010) conducted a randomized controlled trial examining the effect of appending motivational enhancement strategies in the form of open-ended questions to self-guided ICBT for social anxiety. Results indicated that while both treatment groups experienced large reductions on social anxiety scores from pre- to post-treatment (Cohen's d = 1.15–0.97), participants randomized to ICBT with online motivational enhancement strategies had a 75% completion rate, as opposed to a 56% completion rate for the ICBT alone group.

Given the findings that MI can boost CBT outcomes for anxiety and improve treatment adherence in ICBT for social anxiety, we developed an online MI intervention to serve as a pre-treatment to ICBT (Soucy et al., 2018a). Building on suggestions from Titov et al. (2010), who used open-ended questions only, the MI intervention incorporated more interactive online media, including three videos (i.e., Introduction, ICBT Expert, Conclusion) and five exercises (i.e., Values Clarification, Importance Ruler, Looking Back, Confidence Ruler, Looking Forward). The inclusion of more interactive components in the intervention was an attempt to maintain greater consistency with the “spirit” of face-to-face MI, namely building on the principles of partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation - all of which emphasize using the therapeutic skills of asking open-ended questions, practicing reflective listening, and providing affirmative and summary statements (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). This was done through the style of spoken language in the videos, written language in the closed and open-ended questions, and in the immediate feedback provided to participants based on responses to the exercises (Miller and Rollnick, 2013).

The purpose of the current pilot study was to evaluate the acceptability, strengths, and areas for improvement of the newly developed online MI intervention. Specifically, participants were asked to rate their level of motivation prior to and following completion of the intervention, as well as, to provide quantitative and qualitative feedback about the users' experience with and perception of the intervention. Following the methodological example set by Birk et al. (2004), two samples were recruited to evaluate the MI intervention: one sample had past experience with ICBT, as they had previously participated in an ICBT course (i.e., experience with ICBT sample); the other sample had no experience with ICBT (i.e., no experience with ICBT sample) and were recruited from the general population.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Eligibility criteria for both samples were any Canadian resident over 18 years of age, understanding English, and having computer and internet access. The experience with ICBT sample had to have previously participated in an ICBT program (called the Wellbeing Course) in the Online Therapy Unit (OTU: www.onlinetherapyuser.ca) but not be active clients. The no experience with ICBT sample had to indicate not having participated in online therapy. Both samples of participants additionally had to endorse symptoms of anxiety or depression, either by indicating in the consent that they were experiencing anxiety, worry, difficulties with depression and/or loss of pleasure in activities, or by reporting symptoms of anxiety on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7: Spitzer et al., 2006) or depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., 2009; see Measures).

2.2. Procedure

Recruitment took place from August 2018 to January 2019 after receiving approval from the University of Regina Research Ethics Board. To obtain participants with ICBT experience, a staff member of the OTU sent an email invitation to past research participants who previously participated in the Wellbeing course, but had completed their involvement, and had consented to being contacted for future research. To obtain participants without ICBT experience, snowball sampling was employed through Facebook and Twitter. All interested individuals accessed the study through an anonymous online link, which directed participants to the MI intervention and self-report questionnaires on the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform. After meeting eligibility criteria and providing consent, participants were administered the pre-intervention survey along with the Change Questionnaire (CQ; Miller and Johnson, 2008) (see Measures). Participants then worked their way through the online MI intervention (as described below) and after each video or skill, they responded to questions to evaluate the respective video or skill (see Measures). After completing the entire online MI intervention and related evaluation questions, participants concluded by once again completing the CQ and answering questions about their perceptions of the online MI intervention. Participants received debriefing information at the conclusion of the study that reiterated the purpose of the study was to understand perceptions of the new online MI intervention. They were also provided contact information for the OTU and online resources related to anxiety and depression in the event they were interested. The intervention and questionnaires took approximately 1 h to complete.

2.3. Online MI intervention

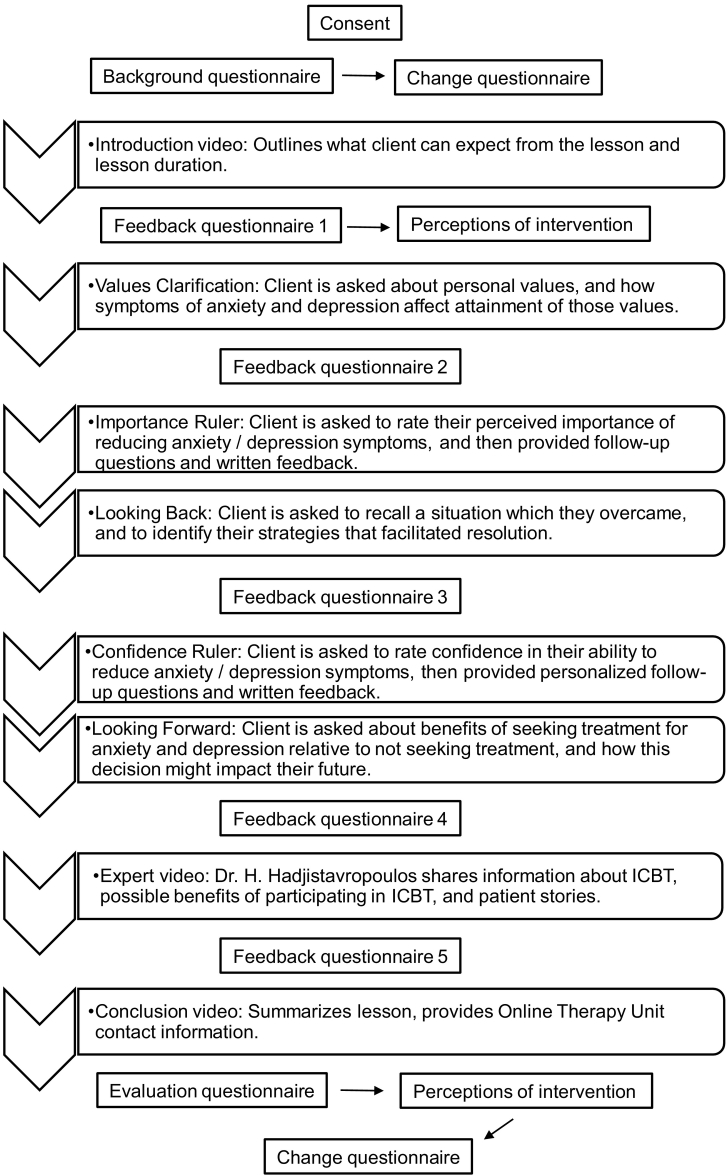

The intervention begins with a brief MI Introduction video explaining the objectives of the intervention. Following the video, the client receives the Values Clarification exercise, which is designed to evoke change talk through exploration of personal values and goals. Open-ended questions encourage clients to think about and identify their values, and to explore how anxiety and depression symptoms impact living congruently and consistently with those values. An Importance Ruler exercise is presented next, which is a common technique used in face-to-face therapy when attempting to provoke client's intrinsic motivation to change (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). Clients rate how important they feel it is to reduce their anxiety or depression on a Likert scale, and then their individual ratings prompt specific follow-up questions that encourage them to reflect on their initial importance ratings. The follow-up questions aim to promote client reflection as to why they did not select the number incrementally lower on the importance scale. Using a similar Likert scale, the client is subsequently asked to rate their likelihood of completing the ICBT program, with higher scores reflecting a higher likelihood. Based on both the importance and likelihood ratings, the client receives a written feedback statement designed to summarize the clients' responses, help clients to reflect on their selected options, and to highlight possible discrepancies between importance of participating in ICBT and completing ICBT. Following the Importance Ruler, the client works through the Looking Back exercise, which includes a series of open-ended questions encouraging clients to recall a situation they experienced and then to reflect on how they managed the situation. The Confidence Ruler exercise follows, which is similar to the Importance Ruler, and involves the client rating on a Likert scale how confident they are in their ability to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms. Similar follow-up questions and written feedback statements to the Importance Ruler are provided during the exercise. The last exercise is the Looking Forward exercise, in which the client is asked to think about the benefits of seeking treatment as compared to not seeking treatment, and how this decision might impact their future. The Expert video follows, which contains information about what to expect from the ICBT course and provides perspectives from previous clients. The intervention ends with the Conclusion video, which summarizes the content of the MI intervention and discusses next steps in obtaining ICBT (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Procedural flow chart.

2.4. Measures

Background questionnaire. Sociodemographic data included age, gender, education level, residence location, ethnicity, and background with counselling and pharmacological treatments. In order to assess symptom severity, participants were administered the PHQ-8 to assess depressive symptoms using 8 items rated on a 4-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) (Kroenke et al., 2009) and the GAD-7 to measure anxiety using 7 items rated on a 4-point scale that ranges from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) (Spitzer et al., 2006). Both measures are scored by summing items to create a total score and have established psychometric properties (Kroenke et al., 2009; Spitzer et al., 2006).

2.4.1. CQ

The CQ is a 12 item self-report scale that measures various components of motivation for change (Miller and Johnson, 2008). Research by Miller and Johnson (2008) identified that, of the 12 items, the three items of importance, confidence, and commitment accounted for 81% of the variance. Therefore, in this study at pre-and post-intervention, we had participants rate the following items on an 11 point scale: (1) It is important for me to reduce the anxiety and/or depression I experience (importance); (2) I feel I can reduce the anxiety and/or depression I experience (confidence); and (3) I am trying to reduce the anxiety and/or depression I experience (commitment). There are no specific interpretation guidelines for the CQ, other than higher ratings on the 0 to 10 scale indicate higher perceived importance to reduce anxiety, higher perceived confidence to change, and higher commitment to change.

2.4.2. Perceptions of the online MI intervention

Immediately following the Introduction video and at post-MI, participants rated the online MI intervention on whether it seemed logical, how successful they perceived it to be in helping someone prepare for ICBT, and in their confidence in recommending the lesson to a friend. The three independent questions were rated on a 1 (not at all) to 9 (very) scale, with higher scores signifying positive perceptions of the intervention across the various facets measured.

2.4.3. Video and exercise evaluation questions

For each video and exercise, participants were asked to complete several evaluative questions that varied to some degree depending on the video or exercise. See Table 4 for a comprehensive list of all evaluation questions. In general, participants were asked to rate the videos and exercises on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very), with higher scores indicating a more positive evaluation. Videos and exercises were rated in terms of the extent to which the respective video or exercise motivated the participant to learn strategies to reduce anxiety and depression. Videos were also rated on a number of additional questions assessing visual appeal, ease of understanding, ease of listening, and interest. For each video and exercise, participants were given the opportunity to provide qualitative feedback responding to questions such as, “Any feedback or comments on the Values Clarification exercise?” and “How can we make this video more helpful?” The final question asked participants, “What, if anything, did you learn about yourself by completing [this] lesson?”

Table 4.

Evaluation questionnaire.

| FQ 1: Introduction video | Experience with ICBT (n = 21) |

No experience with ICBT (n = 20) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Visually appealing | 3.86 | 0.91 | 3.35 | 0.99 | .09 |

| Easy to understand | 4.67 | 0.58 | 4.40 | 0.88 | .28 |

| Easy to listen to | 4.62 | 0.59 | 4.35 | 0.99 | .29 |

| Interesting to watch | 3.86 | 1.11 | 3.45 | 1.23 | .23 |

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | p | |

| Does this video encourage you to learn more about how to reduce symptoms of anxiety/depression? | |||||

| Yes | 15 | 71.4 | 13 | 65.0 | .79 |

| No | – | – | 4 | 20.0 | |

| Unsure | 6 | 28.6 | 3 | 15.0 | |

| Does this video encourage you to learn more about online therapy? | |||||

| Yes | 16 | 76.2 | 13 | 65.0 | .44 |

| No | – | – | – | – | |

| Unsure | 5 | 23.8 | 7 | 35.0 | |

| FQ 2: Values clarification | Experience with ICBT (n = 21) |

No experience with ICBT (n = 20) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Does thinking about your values motivate you to work on learning strategies to improve your wellbeing? | 4.43 | 0.68 | 4.00 | 0.86 | .08 |

| FQ 3: Importance ruler and looking back | Experience with ICBT (n = 21) |

No experience with ICBT (n = 20) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Does thinking about the importance of reducing anxiety/depression motivate you to work on learning strategies to manage anxiety/depression? | 4.57 | 0.51 | 4.25 | 0.91 | .17 |

| Do you find thinking about a situation you previously experienced and recognizing how you overcame it motivates you to work on learning strategies to reduce anxiety/depression? | 4.24 | 0.89 | 3.80 | 0.89 | .12 |

| FQ 4: Confidence ruler and looking forward | Experience with ICBT (n = 21) |

No experience with ICBT (n = 20) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Does thinking about your confidence in your ability to reduce anxiety/depression motivate you to learn strategies to reduce anxiety/depression? | 4.00 | 0.84 | 4.00 | 0.86 | 1.00 |

| Does thinking about your hopes for the future motivate you to learn strategies to reduce anxiety/depression? | 4.24 | 0.70 | 3.90 | 1.07 | .24 |

| FQ 5: Expert video | Experience with ICBT (n = 21) |

No experience with ICBT (n = 20) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Visually appealing | 4.14 | 0.85 | 3.65 | 0.93 | .09 |

| Easy to understand | 4.86 | 0.36 | 4.40 | 1.05 | .67 |

| Easy to listen to | 4.62 | 0.81 | 4.30 | 1.08 | .29 |

| Interesting to watch | 4.00 | 1.05 | 3.75 | 1.12 | .46 |

| Informative | 4.62 | 0.59 | 4.25 | 1.07 | .18 |

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | p | |

| Does this video encourage you to learn more about how to reduce symptoms of anxiety/depression? | |||||

| Yes | 18 | 85.7 | 15 | 75.0 | .28 |

| No | 1 | 4.8 | – | – | |

| Unsure | 2 | 9.5 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| Does this video encourage you to learn more about online therapy? | |||||

| Yes | 18 | 85.7 | 15 | 75.0 | .28 |

| No | 1 | 4.8 | – | – | |

| Unsure | 2 | 9.5 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| FQ 6: Conclusion video | Experience with ICBT (n = 21) |

No experience with ICBT (n = 20) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Visually appealing | 3.95 | 0.92 | 3.60 | 1.05 | .26 |

| Easy to understand | 4.76 | 0.54 | 4.50 | 0.76 | .21 |

| Easy to listen to | 4.76 | 0.54 | 4.55 | 0.76 | .31 |

| Interesting to watch | 4.00 | 1.05 | 3.75 | 1.21 | .48 |

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | p | |

| Does the intervention motivate you to participate in online therapy? | |||||

| Yes | 19 | 90.5 | 19 | 95.0 | .59 |

| No | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 5.0 | |

| M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| How has your motivation changed? | 4.19 | 0.68 | 3.75 | 0.91 | .09 |

Note. All ratings were made on a score from 1 to 5 with higher scores reflecting positive perceptions.

2.5. Analysis

Quantitative data analysis was completed using SPSS version 25. Independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses were used to examine possible differences between the two samples on demographic and clinical variables (i.e., PHQ-8, GAD-7), and mental health treatment history. To measure immediate impact on the ratings of motivation for change, three repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVAs) were conducted, with time as the within-subject variable (i.e., pre- and post-CQ scores) and sample as the between-subject variable (i.e., ICBT experience and no ICBT experience). To measure changes in perceptions of the intervention, three repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted, with time as the within-subject variable (i.e., pre- and post-logical, −successfulness in helping prepare for ICBT, and -confidence in recommending lesson scores) and sample as the between-subject variable (i.e., ICBT experience and no ICBT experience). Video and exercise evaluation scores were examined using descriptive statistics followed by independent samples t-tests to examine possible differences in ratings between the two samples.

Considering the lack of research to date on online MI interventions, we examined participants' open-ended responses evaluating the videos and exercises to identify the perceived strengths and challenges of the intervention. As such, a theoretical thematic analysis was conducted following the protocol outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). Two researchers (CB and JS) individually reviewed the qualitative responses and identified common statements and suggestions. The researchers then conferred on the topics itemized in the review and from this, codes were developed and agreement between raters was assessed (Kappa = 0.80, weighted). Overall categories emerged from the theoretical thematic analysis in the form of positive, negative, and neutral feedback. Positive feedback identified strengths of the intervention, with two themes emerging as to perceptions of the intervention content and as to emotions or thoughts evoked. Subthemes were further identified, which are described in the Results. Negative feedback identified challenges within the MI intervention, with three themes emerging pertaining to structural areas for improvement in the videos or exercises, to difficulties encountered with completing the exercises, and to negative thoughts and feelings evoked from participating in the intervention. Subthemes were further identified, which are described in the Results. Neutral feedback had two themes emerge, namely no response provided or unsure of opinion.

3. Results

3.1. Background characteristics

Forty-one participants fully completed the study (experience with ICBT sample: n = 21; no experience with ICBT sample; n = 20). As shown in Table 1, statistically significant differences were found between the two samples on age, ethnicity, GAD-7, and PHQ-8 scores, with the no experience with ICBT sample being younger in age, all self-identifying as White, and having higher symptom scores. The no experience with ICBT sample had scores suggesting they were experiencing clinically significant anxiety and depression, while those in the ICBT sample were reporting scores that were in the nonclinical range (Kroenke et al., 2009; Spitzer et al., 2006). No other background differences between samples were found.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of samples.

| Experience with ICBT (n = 21) |

No experience with ICBT (n = 20) |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Age | 45.35 | 11.99 | 35.8 | 10.47 | 0.01 |

| PHQ-8 | 7.33 | 4.84 | 11.95 | 6.40 | 0.01 |

| GAD-7 | 5.62 | 4.24 | 11.30 | 7 | 0.00 |

| n | % | n | % | p | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 20 | 95.2 | 18 | 90.0 | 0.21 |

| Male | – | – | 2 | 10.0 | |

| Other | 1 | 4.8 | – | – | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 17 | 81.0 | 20 | 100.0 | 0.04 |

| Other | 4 | 19.0 | – | – | |

| Community size | |||||

| Urban | 17 | 81.0 | 15 | 75.0 | 0.65 |

| Rural | 4 | 19.0 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| Living arrangements | |||||

| Living with family | 15 | 71.4 | 16 | 80.0 | 0.78 |

| Living with roommate | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 5.0 | |

| Living alone | 5 | 23.8 | 3 | 15.0 | |

| Education | |||||

| High school or equivalent | 5 | 23.8 | 2 | 10.0 | 0.48 |

| College Certificate or diploma | 8 | 38.1 | 8 | 40.0 | |

| University | 8 | 38.1 | 10 | 50.0 | |

| Therapeutic treatment | |||||

| Current Therapy - Yes | 3 | 14.3 | 5 | 25.0 | 0.40 |

| Current Therapy - No | 18 | 85.7 | 15 | 75.0 | |

| Past Therapy - Yes | 20 | 95.2 | 17 | 85.0 | 0.28 |

| Past Therapy - No | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 15.0 | |

| Pharmacological treatment | |||||

| Current - Yes | 10 | 47.6 | 9 | 45.0 | 0.87 |

| Current - No | 11 | 52.4 | 11 | 55.0 | |

| Past - Yes | 17 | 81.0 | 13 | 65.0 | 0.26 |

| Past - No | 4 | 19.0 | 7 | 35.0 | |

3.2. Change in motivation

The MI intervention had a statistically significant impact on motivation for change. Examining CQ confidence scores (i.e., I feel I can reduce the anxiety and/or depression I experience), the repeated measures ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect for time, with post-MI confidence scores being significantly higher (p < .0001) than pre-scores across samples (see Table 2). The ANOVA further revealed a statistically significant main effect for sample, F(1,39) = 14.40, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.270, with the no experience with ICBT sample reporting significantly lower confidence scores overall than the experience sample. There were no interaction effects between time and sample for confidence scores (p < .21). Examining scores for importance and commitment to reduce anxiety/depression, no main effects for time or sample were found, nor interaction effects between time and sample. Of note, the main effect for time for importance scores approached statistical significance (p < .052), with pre-MI importance scores being lower than post-MI scores. (See Table 2)

Table 2.

Change questionnaire pre- to post-intervention.

| Outcome measure sample | Pre-intervention Mean (SD) | Post-intervention Mean (SD) | Mean difference (Standard Error) | P value (Effect size (ηp2) for time effect) | P value (Effect size (ηp2) for group effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance to change | |||||

| Experience with ICBT | 8.86 (1.56) | 9.52 (0.81) | 0.383 | 0.052 | 0.75 |

| No experience with ICBT | 9.25 (1.12) | 9.35 (1.35) | (0.191) | (0.093) | (0.003) |

| Confidence to change | |||||

| Experience with ICBT | 7.67 (1.53) | 8.62 (1.43) | 1.326 | 0.0001 | 0.001 |

| No experience with ICBT | 5.85 (1.50) | 7.55 (1.67) | (0.291) | (0.348) | (0.270) |

| Commitment to change | |||||

| Experience with ICBT | 8.95 (1.28) | 8.95 (1.12) | 0.025 | 0.92 | 0.08 |

| No experience with ICBT | 8.15 (2.28) | 8.10 (1.86) | (0.246) | (0.001) | (0.075) |

Note. Likert Scale rating from 0 (Definitely Not) to 10 (Definitely).

3.3. Change in perceptions of the online MI intervention

When examining perceived successfulness of the intervention, there was a statistically significant main effect for time, F(1,39) = 11.60, p ≤ .002, ηp2 = 0.229, with post-MI successfulness scores across samples being significantly higher than pre-MI scores (see Table 3). There was also a statistically significant main effect for sample, F(1,39) = 5.81, p < .02, ηp2 = 0.13, with the experience with ICBT sample reporting significantly higher successfulness scores compared to the no experience sample. There were no interactions between time and sample on ratings of perceived successfulness of the intervention. When examining confidence ratings, there was a statistically significant main effect for time, F(1,39) = 25.96, p < .0001, ηp2 = 0.400, with confidence scores across samples being significantly higher at post-MI than at pre-MI. There was also a statistically significant main effect for sample, which identified the no experience with ICBT sample reported lower scores for overall confidence in recommending the lesson to a friend, F(1,39) = 7.24, p < .01, ηp2 = 0.157, than the experience with ICBT sample. No interactions were found between time and sample on confidence ratings. When examining logic scores, no main effects for time (p < .059) or sample (p < .12) were found, nor an interaction between time and sample. (see Table 3)

Table 3.

Change in perceptions of the online MI intervention.

| Outcome measure Sample | Pre-intervention Mean (SD) | Post-intervention Mean (SD) | Mean difference (Standard Error) | P value (Effect size (ηp2) for time effect) | P value (Effect size (ηp2) for group effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention logical | |||||

| Experience with ICBT | 7.52 (1.60) | 7.81 (1.33) | 0.717 | 0.059 | 0.12 |

| No experience with ICBT | 6.65 (1.98) | 7.25 (1.48) | (0.45) | (0.093) | (0.008) |

| Successful in preparing for ICBT | |||||

| Experience with ICBT | 7.24 (1.67) | 7.90 (1.30) | 0.996 | 0.002 | 0.02 |

| No experience with ICBT | 6.15 (1.53) | 7.00 (1.49) | (0.41) | (0.229) | (0.13) |

| Confidence in recommending | |||||

| Experience with ICBT | 7.24 (1.79) | 8.10 (1.41) | 1.492 | 0.0001 | 0.01 |

| No experience with ICBT | 5.55 (2.01) | 6.80 (2.29) | (0.55) | (0.40) | (0.157) |

3.4. Strengths and areas for improvement in the videos and exercises

As illustrated in Table 4, participants' ratings of the videos and exercises did not differ between the two samples. Examination of mean video ratings indicated that participants felt the videos were visually appealing, easy to understand and listen to, and interesting to watch. Similarly, participants' ratings of the exercises were high, with the lowest mean rating of the exercises being a 4.00 out of 5.0. Following completion of the MI intervention, 39 out of 41 (95.12%) participants indicated interest in participating in ICBT. (See Table 4)

3.5. Theoretical thematic analysis

Participant feedback about the online MI intervention was abundantly positive with some constructive feedback for improvement. From the theoretical thematic analysis of open-ended questions, main categories were identified as to positive, negative, and neutral feedback. Themes within those categories related to the structure and content of the intervention videos and exercises, and to thoughts and feelings evoked by the intervention. Table 5 provides an elaboration on the themes and subthemes, as well as client quotations to further illustrate subthemes identified. Overall, themes and subthemes did not appear to vary by sample, apart from the six participants in the no experience with ICBT sample who encountered technical difficulties with the video. Positive feedback on both the videos and the exercises outweighs the negative, as is evident in Table 5.

Table 5.

Qualitative Feedback on the intervention videos and exercises: categories, descriptions, quotes, and frequencies.

| Categories and subcategories | Descriptions | Example quotes | Experience n (%) | No experience n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Videos - positive | ||||

| Acceptable, well done | Identified as acceptable, as in good, great, or well done. | “It's great.” (participant 129) | 28 (15.63%) | 22 (12.28%) |

| Clear, concise | Information presented in a clear or concise manner. | “It was short and to the point, clear about the lesson and points for what will be included.” (participant 44) | 22 (12.28%) | 21 (11.72%) |

| Informative | Informative or adequate information provided. | “Very informative and a good length.” (participant 54) | 19 (10.60%) | 18 (10.04%) |

| Encouraging, helpful | Identified as encouraging, positive, or helpful | “It was well done and informative. It came off as positive and encouraging.” (participant 46) | 12 (6.69%) | 9 (5.02%) |

| Videos - negative | ||||

| Lacks detail | More details or information on ICBT preferred. | “Not enough info. About strategies, what happens next.” (participant 227) | 6 (3.34%) | 7 (3.90%) |

| Design improvements | Suggestions for alternative design elements, for example using different graphics. | “What's with the arrows?” (participant 167) | 2 (1.11%) | 3 (1.66%) |

| Technical difficulties | Technical difficulties encountered with the video not playing or in having very little volume. | “Video would not load.” (participant 150) | – | 6 (3.34%) |

| Videos - neutral | ||||

| No opinion or no response provided. | No opinion expressed or no response provided. | “N/A.” (participant 58) | 2 (1.11%) | 2 (1.11%) |

| Exercises - positive | ||||

| Insightful | Exercises identified as thought provoking, and as providing opportunity to self-reflect. | “Interesting overall as a reflection of things I don't normally reflect on.” (participant 239) | 23 (18.25%) | 9 (7.14%) |

| Empowering | Exercises were empowering, encouraging, self-affirming. | “That I should value my courage to ask for help when I need it. That my mental well-being is mine to control and change when required with the help of trained professionals. That I'm not alone.” (participant 51) | 14 (11.13%) | 11 (8.74%) |

| Motivating | Exercises described as motivating, energizing, and providing opportunity to recognize desire to change. | “Forcing yourself to really think about things can be motivating and help to re-energize your desire and/or commitment to get better.” (participant 46) | 15 (11.90%) | 6 (4.76%) |

| Exercises - negative | ||||

| Feedback statements | Confusion regarding feedback statements that were provided after certain exercises, or that it was computerized. | “What feedback are you talking about? Who is giving me feedback?” (participant 56) | 10 (7.93%) | 3 (2.39%) |

| Difficulty completing | Difficulty with self-reflection and with identifying personal strengths, or that exercise too lengthy. | “It's hard to think positive things when you are feeling down. My mind goes blank.” (participant 204) | 6 (4.76%) | 9 (7.13%) |

| Questioning helpfulness | Experience with ICBT sample expressed uncertainty if intervention would be helpful. | “To be honest, I don't know if [the intervention] would have made any difference for me as I was so desperate for help that I was willing to try no matter what.” (participant 137) | 3 (2.39%) | – |

| Exercises - neutral | ||||

| No opinion or no response provided. | No opinion expressed or no response provided. | “I don't know.” (participant 115) | 11 (8.72%) | 6 (4.76%) |

4. Discussion

Considering the known benefits of integrating CBT and MI (Sijercic et al., 2016), in addition to the successful adaptation of CBT to ICBT (Carlbring et al., 2018), it follows that a natural direction for research would be to adapt MI into an online format as an adjunct to ICBT to further enhance clinical outcomes. Yet the adaptation of MI to an online format is complex; face-to-face MI is an interactive therapeutic process whereby therapists attempt to cultivate a partnership with the client by demonstrating acceptance and compassion through both spoken and body language. Face-to-face MI also includes the therapist communicating with the client in a directive way so as to evocate, identify, and resolve the client's ambivalence to change (Miller and Rollnick, 2013).

In light of these challenges, the current study offered a preliminary evaluation of a newly developed online MI intervention, which sets the stage for future testing of the intervention, and may be of interest to other researchers and clinicians seeking to incorporate MI into ICBT. Overall, the findings indicate the intervention had an effect on immediate motivation for change, namely ratings of confidence to change, which were observed across participants with and without ICBT experience. Similarly, results suggest that the intervention had a significant impact on increasing perceptions of ICBT across both samples, with all but two participants expressing further interest to participate in ICBT. The qualitative information further provided insight into the strengths and areas for improvement in the individual components of the MI intervention. The results from this study parallel research findings by Hettema et al. (2005), who found that face-to-face MI had an effect that was detected early in treatment.

As a whole, the findings are positive in that MI is based on making individuals self-aware of their potential for change in behaviour, whereby “small changes may be of interest if they mark the beginning of a changing process for the [individual]” (Rubak et al., 2005, p. 309). In the current study, the MI intervention sought to better prepare participants for participating in ICBT. The intervention was found to significantly impact confidence to change and approached statistical significance for increasing perceived importance of change. These findings demonstrate the MI intervention did mark the beginning of change for participants with and without ICBT experience. Of note, the intervention did not have an immediate impact on commitment ratings. In hindsight, participants' self-rated scores for commitment, or “trying to change”, were generally high across both samples at pre-intervention and at post-intervention. It is possible that a single MI lesson is too short of a time period to immediately effect this rating. Despite no significant immediate effects on commitment being reported, individuals may have continued along in the change process in trying to reduce their symptoms after the MI intervention. If participants had been provided the opportunity to begin ICBT after the MI intervention, it is possible that the self-report ratings for commitment may have improved as participants learned the skills to reduce symptoms.

Qualitative feedback from participants suggested that the adaptation to an online format was successful in evoking interest to change across both samples. Participants shared statements reflecting discovery of their new found ability to make change occur, as well as, indicating the identification and mobilization of intrinsic values and goals. Interestingly, the open-ended questions in the feedback questionnaires during the intervention did not ask participants to share their thoughts or feelings about change, rather the questions asked for comments or feedback on the exercises; yet, participants provided personal thoughts and feelings in response to the questions of their own volition. This follows the MI principle of evocation whereby shared participant thoughts and feelings are considered essential for identifying and resolving ambivalence to change (Rubak et al., 2005). Given that change talk is posited to be one of the main mechanisms of change in face-to-face MI (Magill and Hallgren, 2019), participants' expression of change talk in the current study provides preliminary support for the effectiveness of this intervention.

Speaking to the results of the online MI intervention, the differences between the two samples warrant discussion. The experience with ICBT sample differed from the no experience with ICBT sample in a number of ways. The experience with ICBT sample had lower overall symptoms of anxiety and depression than the no experience sample. Considering the experience with ICBT sample had all engaged in ICBT at some point in the past one to five years, it is encouraging to note that the participants with previous ICBT experience were in the nonclinical range – which is what one would hope after participating in ICBT. The no experience with ICBT sample did indicate anxiety and depression scores within the clinical range, based on the measures administered. This sample was also younger than the overall experience with ICBT sample, which may be in part due to the method of recruitment for each sample. In terms of responding to items, the experience with ICBT sample reported higher scores overall for confidence to work on reducing symptoms, which may be due to the fact that these participants had previously worked on reducing their symptoms by engaging in ICBT. They also reported perceiving the online MI intervention as more likely to be successful in preparing one to participate in ICBT and as having somewhat higher confidence in recommending the intervention to a friend, as compared to ratings from the no experience sample.

One possible explanation for the differences in perceptions of the online MI intervention could be that experience with ICBT positively influences participant perceptions. Another possibility is that higher symptom scores negatively influences one's perception, whether it be in one's confidence to reduce symptoms, or confidence in an intervention that encourages working on symptoms. It is important to note that, despite the differences between samples in age, symptom severity, and item ratings, both samples reported an increase in confidence to reduce symptoms, in the successfulness of the intervention, and in confidence of recommending the intervention to a friend. Both samples rated the intervention positively, so much so that 39 out of 41 participants expressed further interest in participating in ICBT after working through the online MI intervention.

4.1. Limitations and strengths

The current study was designed to gain user feedback and to explore the immediate impact of the online MI intervention on motivation for change. As such, it is not yet known how the MI intervention will impact motivation for ICBT or whether it will have a direct effect on clinical outcomes. Due to an overall lack of research to date on MI as an adjunct to ICBT, it remains unclear exactly how MI impacts ICBT engagement, adherence, and symptom change. An additional limitation remains that motivation was assessed using a self-report rather than an objective measure (e.g., logging into the ICBT program, symptom reductions). Further to this point, while the CQ has been found to have greater value in predicting CBT outcomes relative to alternative self-report measures of motivation (e.g., Sijercic et al., 2016), additional research is required in order to determine the effect of the online MI intervention on ICBT outcomes. Consistent with pre-CQ scores, both samples of participants were motivated prior to participating in the online MI intervention and, thus, it is unknown if the intervention would have a different effect if participants were less motivated. As this preliminary study was conducted without a control group and a relatively small sample, replication with control groups and larger samples is needed in order to examine the differential impact of the online MI intervention on changes in motivation levels compared to no such intervention, or to a control intervention that only provides education on ICBT (e.g., Soucy et al., 2016). Moreover, Braun and Clarke (2006) postulate that qualitative feedback, while valuable for identifying strengths and limitations, can be limited by what participants are willing to share and also by researcher interpretation. In an attempt to control for variability of researcher interpretation and bias, two researchers reached agreement on the categories and themes identified in participant feedback. It is still possible, however, that participants' responses to the questions asked throughout the online MI intervention were not consistent with what they actually believe.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the current study is important for several reasons. Foremost, the reviewed online MI intervention was developed to be more consistent with face-to-face MI and represents a potential cost-effective approach to further enhance ICBT outcomes. The mixed methodology used in the current study allowed for an understanding of how MI impacted perceived motivation, and led to a better understanding of the video and exercise features that could be improved upon. Recognizing areas for improvement can be used to alter sections of the online MI intervention going forward. In addition, two samples were examined in the current study, which yielded comparable positive impacts on individuals who have experience with ICBT and those who do not. This is encouraging as the samples not only had different experiences with ICBT, but also the no experience sample had higher depression and anxiety scores. As such, the findings suggest that online MI can be used across different samples of participants regardless of ICBT experience, age, and symptom severity. This is particularly important given that many participants who seek ICBT have limited experience with treatment in general, and even less experience with internet interventions prior to starting (Titov et al., 2019).

4.2. Future research

The identified strengths and areas for improvement gathered from participant feedback in the current study facilitate the modification and improvement of the MI intervention going forward. This is beneficial to the current research team but also to others who may be interested in developing MI to supplement internet interventions. More examples should be added to the exercises to facilitate participants thinking about themselves, their values, and their possible strengths. Furthermore, additional information about the ICBT course lessons could be included with the Expert video. Building on the findings of the current study, the MI intervention warrants testing in a randomized clinical trial (RCT) to further understand whether online MI impacts ICBT engagement and outcomes for anxiety and depression as intended. The impact of the intervention on related constructs to motivation, such as self-efficacy, may also merit examination. Soucy and Hadjistavropoulos are currently conducting a large-scale RCT (registered with Clinical Trials (NCT03684434)), with participants randomly assigned to receive the online MI intervention or no treatment (i.e., a waiting period) prior to transdiagnostic ICBT for anxiety and depression. Results will inform whether online MI can be used as a cost-effective adjunct to ICBT.

Longer term, should Soucy and Hadjistavropoulos find that MI positively impacts engagement in ICBT and participant outcomes, further investigation is warranted to explore the possible mechanisms of change. This could be accomplished by randomly assigning participants to receive the MI intervention or to receive a control intervention, such as psychoeducation on mental health, which is similar in length but does not aim to increase motivation. It would also be informative to explore if online MI could improve adherence when lower levels of therapist support are offered (e.g., Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017). Currently, self-guided ICBT has lower levels of treatment completion than therapist-guided, and thus, online MI has the potential to reduce therapist time and costs while not compromising clinical outcomes (Baumeister et al., 2014; Mehta et al., 2018). Moreover, it would be valuable to explore the impact of MI on patient behaviour during ICBT, for example, the level of participant engagement and completion rates (Gullickson et al., 2019; Soucy et al., 2018a, Soucy et al., 2018b; Soucy et al., 2019). It would also be valuable to explore how online MI, and thus patient motivation, impacts therapist behaviour, such as praising effort, encouraging practice, or even the style of language therapists employ (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2019a; Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2018;). Given the adaptability of ICBT, it would be important to also explore the use of the MI intervention by others who deliver ICBT in routine care (Titov et al., 2018), as well as whether the intervention could be adapted and used with other types of internet interventions, such as ICBT for chronic health conditions (Mehta et al., 2018), or ICBT for alcohol misuse (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2019b), or whether it could be offered with blended ICBT with face-to-face CBT (Mathiasen et al., 2016).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to the Online Therapy Unit team, to those who participated in this study, and to Nichole Faller for sharing their insight and experience with us.

Funding

H.D.H. is funded by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health to operate the Online Therapy Unit. The Unit also holds research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (152917), the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, and the Saskatchewan Centre for Patient-Oriented Research. JS is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Funders had no involvement in the design of the paper, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

References

- Andersson G. Internet-delivered psychological treatments. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2016;12:157–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Titov N. Advantages and limitations of Internet-basedinterventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:4–11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Titov N., Dear B.F., Rozental A., Carlbring P. Internet-delivered psychological treatments: from innovation to implementation. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):20–28. doi: 10.1002/wps.20610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H., Reichler L., Munzinger M., Lin J. The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions – a systematic review. Internet Interv. 2014;1:205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Birk T., Hickl S., Wahl H.-W., Miller D., Kammerer A., Holz…Volcker H.W. Development and pilot evaluation of a psychosocial intervention program for patients with age-related macular degeneration. The Gerontologist. 2004;44(6):836–843. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.6.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Butler A.C., Chapman J.E., Forman E.M., Beck A.T. The empirical status ofcognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006;26(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P., Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Riper H., Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Internet- based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47(1):1–18. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds M., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Schneider L.H., Dear B.F., Titov N. Who benefits most from therapist-assisted Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy in clinical practice? Predictors of symptom change and drop out. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2018;54:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullickson K.M., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Dear B.F., Titov N. Negative effects associated with internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy: an analysis of client emails. Internet Interv. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100278. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Schneider L.H., Edmonds M., Karin E., Nugent M.N., Dirkse D., Dear B.F., Titov N. Randomized controlled trial of Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy comparing standard weekly versus optional weekly therapist support. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2017;52:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Schneider L.H., Klassen K., Dear B.F., Titov N. Development and evaluation of a scale assessing therapist fidelity to guidelines for delivering therapist-assisted Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47(6):447–461. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1457079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Gullickson K.M., Schneider L.H., Dear B.F., Titov N. Development of the Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy undesirable therapist behaviours scale (ICBT-UTBS) Internet Interventions. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100255. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Mehta S., Wilhelms A., Keough M.T., Sundström C. A systematic review of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for alcohol misuse: study characteristics, program content and outcomes. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019:1–21. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2019.1663258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen G.L., Moyers T.B. Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC), Version 1.1: Addendum to MISC 1.0. 2009. http://casaa.unm.edu Retrieved from the University of New Mexico Center on Alcoholism, Substance Use and Addictions.

- Hettema J., Steele J., Miller W.R. Motivational interviewing. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Strine T.W., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W., Berry J.T., Mokdad A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi D.R., Button M.L., Westra H.A. Measuring motivation: change talk and counter-change talk in cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2014;43:12–21. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.846400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M., Hallgren K.A. Mechanisms of behavior change in motivational interviewing: do we understand how MI works? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019;30:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marker I., Norton P. The efficacy of incorporating motivational interviewing to cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders: a review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018;62:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiasen K., Andersen T.E., Riper H., Kleiboer A.A.M., Roessler K.K. Blended CBT versus face-to-face CBT: a randomized non-inferiority trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(432) doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1140-y. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27919234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S., Peynenburg V.A., Hadjistavropoulos H.D. Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic health conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Behav. Med. 2018;42(2):169–187. doi: 10.1007/s10865-018-9984-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.R. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav. Psychother. 1983;11:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.R., Johnson W.R. A natural language screening measure for motivation to change. Addictive Behaviours. 2008;33:1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W., Rollnick S. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. [Google Scholar]

- Newby J.M., Twomey C., Li S.S.Y., Andrews G. Transdiagnostic computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;199:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riper H., Andersson G., Hunter S.B., Wit J., Berking M., Cuijpers P. Treatment of comorbid alcohol use disorders and depression with cognitive-behavioural therapy and motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109(3):394–406. doi: 10.1111/add.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S., Sandbaek A., Lauritzen T., Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2005;55(513):305–312. https://bjgp.org/content/55/513/305.full Retrieved from. (on April 27, 2019) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijercic I., Button M.L., Westra H.A., Hara K.M. The interpersonal context of client motivational language in cognitive-behaviour therapy. Psychotherapy. 2016;53(1):13–21. doi: 10.1037/pst0000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy J.N., Owens V.A.M., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Dirkse D.A., Dear B.F. Educating patients about Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy: perceptions among treatment seekers and non-treatment seekers before and after viewing an educational video. Internet Interv. 2016;6:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy J.N., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Beck C.D. University of Regina; Regina, Canada: 2018. Development and Evaluation of an Online Motivational Interviewing Intervention for Enhancing Engagement in Internet-delivered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation proposal) [Google Scholar]

- Soucy J.N., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Couture C.A., Owens V.A.M., Dear B.F., Titov N. Content of client emails in Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy: a comparison between two trials and relationship of outcome. Internet Interv. 2018;11:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy J., Hadjistavropoulos H., Pugh N., Dear B., Titov N. What are clients asking their therapist during therapist-assisted Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy? A content analysis of client questions. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2019;47(4):407–420. doi: 10.1017/S1352465818000668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Andrews G., Schwencke G., Robinson E., Peters L., Spence J. Randomized controlled trial of Internet cognitive behavioural treatment for social phobia with and without motivational enhancement strategies. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2010;44:938–945. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.493859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B., Nielssen O., Staples L., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Nugent M.…Kaldo V. ICBT in routine care: A descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interventions. 2018;13:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Nielssen O., Mohr D.C., Andersson G., Dear B.F. From research to practice: ten lessons in delivering digital mental health services. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1239. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra H.A. Managing resistance in cognitive behavioural therapy: the application of motivational interviewing in mixed anxiety and depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2004;33:161–175. doi: 10.1080/16506070410026426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra H.A., Aviram A., Doell F.K. Extending motivational interviewing to the treatment of major mental health problems: current directions and evidence. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2011;56(11):643–650. doi: 10.1177/070674371105601102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf Retrieved from.