Abstract

BACKGROUND

Systemic inflammation and nutrition status play an important role in cancer metastasis. The combined index of hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP), consisting of haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocytes, and platelets, is considered as a novel marker to reflect both systemic inflammation and nutrition status. However, no studies have investigated the relationship between HALP and survival of patients with pancreatic cancer following radical resection.

AIM

To evaluate the prognostic value of preoperative HALP in pancreatic cancer patients.

METHODS

The preoperative serum levels of hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte counts, and platelet counts were routinely detected in 582 pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients who underwent radical resection. The relationship between postoperative survival and the preoperative level of HALP was investigated.

RESULTS

Low levels of HALP were significantly associated with lymph node metastasis (P = 0.002), poor tumor differentiation (P = 0.032), high TNM stage (P = 0.008), female patients (P = 0.005) and tumor location in the head of the pancreas (P < 0.001). Low levels of HALP were associated with early recurrence [7.3 mo vs 16.3 mo, P < 0.001 for recurrence-free survival (RFS)] and short survival [11.5 mo vs 23.6 mo, P < 0.001 for overall survival (OS)] in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A low level of HALP was an independent risk factor for early recurrence and short survival irrespective of sex and tumor location.

CONCLUSION

Low levels of HALP may be a significant risk factor for RFS and OS in patients with resected pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, HALP, Systemic inflammation, Nutrition status, Postoperative survival

Core tip: The index of hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) consists of haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocytes, and platelets. It is considered as a novel marker to show systemic inflammation and nutrition status. We demonstrated that a low level of HALP was an independent risk factor for surgical outcome in pancreatic cancer patients following radical resection. Its prognostic value is superior to that of previous markers commonly used for systemic inflammation and nutrition status (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and prognostic nutritional index).

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is one of most lethal solid tumors. Radical resection provides the only opportunity for long-term survival. However, long-term survival after resection remains poor as a result of a high incidence of recurrence. The 5-year survival rate after radical surgery is approximately 20%[1,2]. It is urgent to find potential markers that can accurately predict postoperative recurrence and help with decision making for subsequent therapies.

Systemic inflammation and nutrition status play an important role in cancer metastasis. Several preoperative haematological inflammation indices have been demonstrated as prognostic markers for pancreatic cancer. Peripheral blood cells, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, and monocytes, have been reported to be associated with malignancy degree of cancer[3,4]. Inflammatory indices based on the levels of blood cells, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)[5] and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)[6], have been used to predict the prognosis of patients with pancreatic cancer. Nutritional status, such as haemoglobin and albumin levels (prognostic nutritional index, PNI), has also been shown to be an important marker for predicting survival in cancer patients[7].

Recent studies have identified a new marker, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP), which consists of haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocytes, and platelets, to reflect both systemic inflammation and nutrition status. It has been reported to be associated with survival in patients with gastric[8], colorectal[9], renal[10], and bladder cancers[11]. However, no studies have investigated the relationship between HALP and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer following radical resection. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the prognostic value of preoperative HALP in patients with resected pancreatic cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From March 2010 to December 2015, a total of 906 patients were screened. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Pathologically confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma; and (2) Treatment with radical resection. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Incomplete clinicopathological and follow-up data (n = 15); (2) History of antitumor treatments (n = 69); (3) Record of other malignant tumors (n = 18); and (4) Total bilirubin level > 34.2 μmol/L (n = 222). Finally, 582 eligible patients were included in the study. All the clinical features, including routine blood tests and liver function tests, and the follow-up data from each patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, were prospectively recorded in our institutional database. The study was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai Cancer Center. Informed consent was obtained from each patient according to the committee’s guidelines.

Patient follow-up

Each patient was routinely followed until death due to disease recurrence in compliance with a standardized protocol as described in our previous studies[12,13]. Briefly, each patient was checked every month or more often by clinical and laboratory examinations after surgery. If local or metastatic recurrence was suspected, imaging tests (computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging, bone scans, or positron emission tomography/computed tomography) were suggested accordingly. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval from surgery to death or to the last follow-up visit. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time interval from surgery to tumor recurrence or to the last follow-up visit. If the event (death and recurrence) did not take place at the time of the last follow-up, the data were censored at the time of the last visit.

Statistical analysis

The NLR was calculated as the neutrophil count/lymphocyte count, the PLR was calculated as the platelet count/lymphocyte count, and the PNI was calculated as albumin level (g/L) + 5 × lymphocyte count (109/L)[14]. HALP was determined by haemoglobin level (g/L) × albumin level (g/L) × lymphocyte count (/L)/platelet count (/L)[8]. Cut-off values for the NLR, PLR, PNI, and HALP for subgroup classification of OS were illustrated with X-tile software (version v3.6.1, Yale University). The cut-off value with the minimum P value calculated from the log-rank χ2 test for OS was determined as the optimal cut-off value. Relationships between categorical variables were analysed by Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to plot the distribution of OS and RFS by group. The log-rank tests were conducted to compare the survival of patients among subgroups. Multivariate Cox regression survival analyses were performed to identify the independent association of all clinical features with survival. The minimum numbers of independently significant variables were determined by backward stepwise variable selection in the multivariate Cox regression survival analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 13.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) and were two-sided. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical features and patient survival

The clinical characteristics of the 582 patients included are described in Table 1. The median age was 61 years (range, 29-82 years). Three hundred and nineteen patients were male. Two hundred and forty-three patients had tumors located in the head of the pancreas. More than 3 positive lymph nodes were detected in 75 patients, and 1-3 positive lymph nodes were found in 210 patients. Poorly differentiated tumors were confirmed in 221 patients. Vascular invasion and nerve invasion by the tumors were identified in 126 patients and 476 patients, respectively. Elevated preoperative serum CA19-9 was detected in 440 patients. Four hundred and seventy-seven patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. At the last follow-up, 255 patients died of the disease. The median OS time was 20.9 mo, and the OS percentages at 1 and 3 years were 66.0% and 32.9%, respectively. Tumor recurrence after surgery was confirmed in 405 patients. The median RFS time was 10.2 mo, and the percentages of RFS at 1 and 3 years were 41.1% and 13.9%, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of patients with resected pancreatic cancer, n (%)

| Features | n = 582 |

| Age [yr, median (range)] | 61 (29-82) |

| Gender (male/female) | 319(54.8)/263(45.2) |

| Tumour location (head/body, tail) | 243(41.8)/339 (58.2) |

| Preoperative CA19-9 (> 37 U/mL/≤ 37 U/mL) | 440 (75.6)/142 (24.4) |

| HALP (> 44.56/≤ 44.56) | 351 (60.3)/231 (39.7) |

| NLR (> 2.20/≤ 2.20) | 287 (49.3)/295 (50.7) |

| PLR (> 112.94/≤ 112.94) | 331 (56.9)/251 (43.1) |

| PNI (> 53.10/≤ 53.10) | 249 (42.8)/333 (57.2) |

| Tumour size (cm, median (range)) | 4.0 (0.3-11.5) |

| Lymph node metastasis (more than 3/1-3/0 positive lymph nodes) | 75 (12.9)/210 (36.1)/297 (51.0) |

| Total lymph nodes resected [median (range)] | 12 (1-69) |

| TNM stage (IA/IB/IIA/IIB/III) | 39 (6.7)/164 (28.2)/94 (16.2)/210 (36.0)/75 (12.9) |

| Differentiation (well, moderate/poor) | 361 (62.0)/221 (38.0) |

| Neural invasion (yes/no) | 476 (81.8)/106 (18.2) |

| Microvascular invasion (yes/no) | 126 (21.6)/456 (78.4) |

HALP: Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI: Prognostic nutritional index.

Association between HALP and clinical features

The cut-off value of HALP was determined to be 44.56, which provided the best classification for survival prediction. A low level of HALP was present in 231 patients. Patients with low levels of HALP tended to have lymph node metastasis (P = 0.002), poor tumor differentiation (P = 0.032) and high TNM stage (P = 0.008, Table 2). A low level of HALP was more likely to be present in female patients (P = 0.005) or in patients with tumors located in the head of the pancreas (P < 0.001). Low levels of HALP were significantly associated with high NLR (P < 0.001) and PLR (P < 0.001) levels. A low level of HALP was significantly associated with a low PNI level (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Relationship between hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet and clinical features in patients with resected pancreatic cancer

| Features |

HALP |

||

| Low (≤ 44.56, n = 231) | High (> 44.56, n = 351) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 0.161 | ||

| ≤ 62 | 112 | 191 | |

| > 62 | 119 | 160 | |

| Gender | 0.005 | ||

| Female | 121 | 142 | |

| Male | 110 | 209 | |

| Preoperative CA19-9 | 0.473 | ||

| ≤ 37 U/mL | 60 | 82 | |

| > 37 U/mL | 171 | 269 | |

| NLR | < 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 2.20 | 77 | 218 | |

| > 2.20 | 154 | 133 | |

| PLR | < 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 112.94 | 17 | 234 | |

| > 112.94 | 214 | 117 | |

| PNI | < 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 53.10 | 187 | 146 | |

| > 53.10 | 44 | 205 | |

| Tumor location | < 0.001 | ||

| Head | 122 | 121 | |

| Body/Tail | 109 | 230 | |

| TNM stage | 0.008 | ||

| IA | 13 | 26 | |

| IB | 59 | 105 | |

| IIA | 30 | 64 | |

| IIB | 86 | 124 | |

| III | 43 | 32 | |

| Tumor size | 0.718 | ||

| ≤ 4.0 cm | 146 | 227 | |

| > 4.0 cm | 85 | 124 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.002 | ||

| 0 | 102 | 195 | |

| 1-3 | 86 | 124 | |

| > 3 | 43 | 32 | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.032 | ||

| Well/Moderate | 131 | 230 | |

| Poor | 100 | 121 | |

| Neural invasion | 0.672 | ||

| No | 44 | 62 | |

| Yes | 187 | 289 | |

| Microvascular invasion | 1.000 | ||

| No | 173 | 283 | |

| Yes | 58 | 68 | |

HALP: Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI: Prognostic nutritional index.

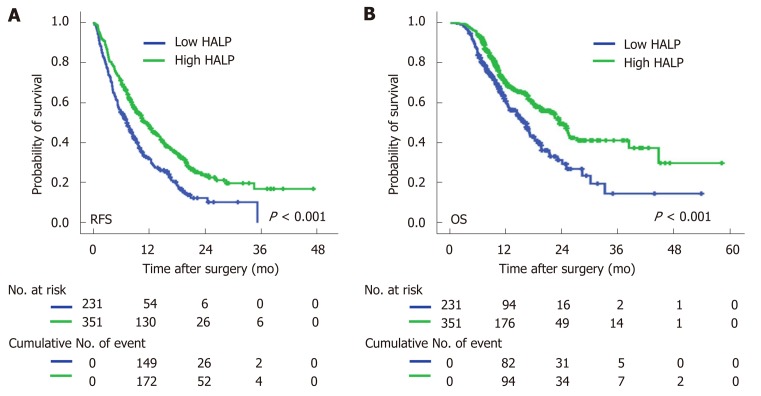

Low levels of HALP associated with poor RFS and OS

Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that high NLR and high PLR levels, low PNI levels and low levels of HALP were all associated with a short median time of OS and RFS (Table 3). The median time of RFS and OS in patients with low levels of HALP was 7.3 mo and 16.3 mo, respectively, compared to patients with high levels of HALP (11.5 mo and 23.6 mo, respectively; P < 0.001, Figure 1). Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that a high level of HALP was an independent favor factor for both RFS [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.601, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.433-0.835, P < 0.001] and OS (HR = 0.605, 95%CI: 0.472-0.774, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall survival in subgroups of patients with resected pancreatic cancer

| Features |

OS |

RFS |

||||||||||

|

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | 0.874 | 0.683-1.119 | 0.286 | NS | 0.896 | 0.737-1.090 | 0.273 | NS | ||||

| Gender (male versus female) | 1.312 | 1.021-1.686 | 0.034 | NS | 1.196 | 0.982-1.456 | 0.075 | NS | ||||

| Tumor location (body/tail versus head) | 0.925 | 0.722-1.185 | 0.538 | NS | 0.976 | 0.806-1.188 | 0.805 | NS | ||||

| Preoperative CA19-9 (> 37 U/mL/≤ 37 U/mL) | 1.871 | 1.355-2.585 | < 0.001 | 1.629 | 1.176-2.258 | 0.003 | 1.543 | 1.218-1.955 | < 0.001 | 1.45 | 1.143-1.839 | 0.002 |

| HALP (> 44.56/≤ 44.56) | 0.605 | 0.472-0.774 | < 0.001 | 0.601 | 0.433-0.835 | < 0.001 | 0.633 | 0.520-0.772 | < 0.001 | 0.678 | 0.556-0.828 | < 0.001 |

| NLR (> 2.20/≤ 2.20) | 1.654 | 1.289-2.122 | < 0.001 | 1.394 | 1.062-1.831 | 0.017 | 1.442 | 1.185-1.754 | < 0.001 | NS | ||

| PLR (> 112.94/≤ 112.94) | 1.272 | 0.990-1.634 | 0.06 | NS | 1.277 | 1.047-1.557 | 0.016 | NS | ||||

| PNI (> 53.10/≤ 53.10) | 0.663 | 0.511-0.860 | 0.002 | NS | 0.764 | 1.650-1.970 | 0.024 | NS | ||||

| TNM stage (III/IIB/IIA/IB/IA) | 1.39 | 1.240-1.558 | < 0.001 | 1.302 | 1.161-1.461 | < 0.001 | 1.294 | 1.184-1.413 | < 0.001 | 1.236 | 1.132-1.350 | < 0.001 |

| Tumor size (> 4.0/≤ 4.0 cm) | 1.586 | 1.237-2.034 | < 0.001 | NA | 1.334 | 1.092-1.630 | 0.005 | NA | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis (more than 3/1-3/0 nodes) | 1.658 | 1.395-1.970 | < 0.001 | NA | 1.533 | 1.334-1.761 | < 0.001 | NA | ||||

| Total lymph nodes resected | 0.992 | 0.979-1.006 | 0.246 | NS | 1.001 | 0.991-1.011 | 0.868 | NS | ||||

| Differentiation (well, moderate versus poor) | 2.192 | 1.711-2.808 | < 0.001 | 1.988 | 1.547-2.555 | < 0.001 | 1.791 | 1.467-2.187 | < 0.001 | 1.672 | 1.367-2.043 | < 0.001 |

| Neural invasion (yes versus no) | 1.533 | 1.078-2.182 | 0.018 | NS | 1.358 | 1.041-1.772 | 0.024 | NS | ||||

| Microvascular invasion (yes versus no) | 1.424 | 1.070-1.894 | 0.015 | NS | 1.306 | 1.037-1.646 | 0.024 | NS | ||||

HALP: Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PNI: Prognostic nutritional index; OS: Overall survival; RFS: Recurrence-free survival; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; NA: Not adopted; NS: Not significant.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrence-free survival and overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients. A: Recurrence-free survival was stratified by low/high levels of HALP; B: Overall survival was stratified by low/high levels of HALP. HALP: Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet.

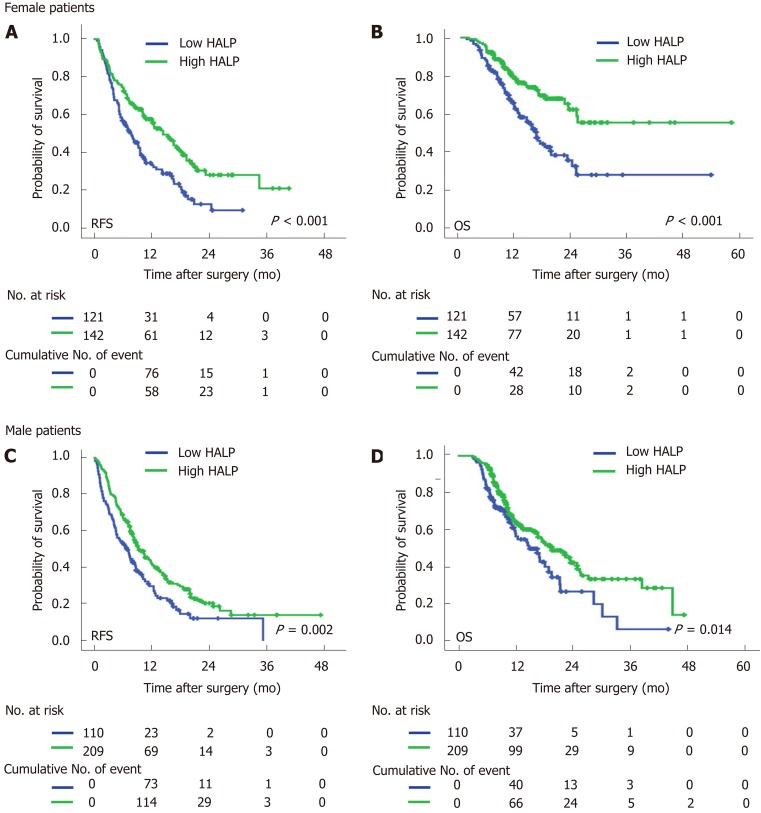

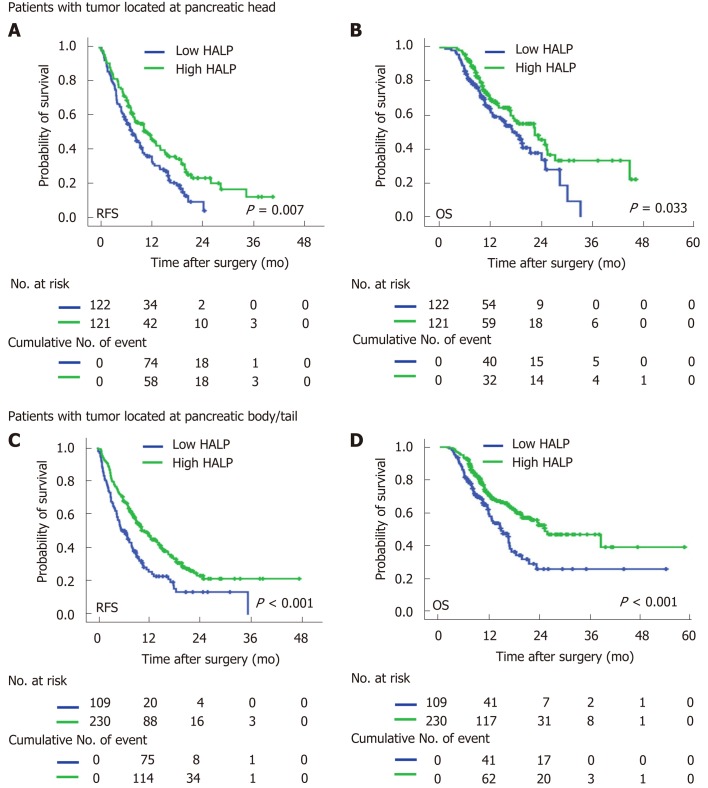

Low levels of HALP predicted poor OS and RFS classified by sex and tumor location

In both male and female patients, patients with a low level of HALP had a shorter median time of RFS (7.0 mo vs 9.5 mo, P = 0.002 for males; and 7.9 mo vs 14.5 mo, P < 0.001 for females; Figure 2) and OS (16.6 mo vs 19.7 mo, P = 0.014 for males; and 16.4 vs median time not reached, P < 0.001 for females; Figure 2) compared to patients with a high level of HALP. Regardless of tumor location in the head or body/tail of the pancreas, the median time of RFS (8.0 mo vs 11.9 mo, P = 0.007 for pancreatic head tumors; and 6.6 mo vs 11.5 mo, P < 0.001 for pancreatic body/tail tumours; Figure 3) and OS (18.2 mo vs 22.5 mo, P = 0.033 for pancreatic head tumors; and 14.6 mo vs 25.1 mo, P < 0.001 for pancreatic body/tail tumors; Figure 3) was significantly shorter in patients with low levels of HALP than in patients with high levels of HALP.

Figure 2.

Recurrence-free survival and overall survival were stratified by low/high levels of haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet in both female and male pancreatic cancer patients. A: Recurrence-free survivals were stratified by low/high levels of HALP (hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet) in female patients. B: Overall survivals were stratified by low/high levels of HALP in female patients. C: Recurrence-free survivals were stratified by low/high levels of HALP in male patients. D: Overall survivals were stratified by low/high levels of HALP in male patients. HALP: Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet.

Figure 3.

Recurrence-free survival and overall survival were stratified by low/high levels of haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet in pancreatic cancer patients with tumour located at head and body/tail. A: Recurrence-free survival was stratified by low/high levels of HALP (hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet) in patients with tumor located at head. B: Overall survival was stratified by low/high levels of HALP in patients with tumor located at head. C: Recurrence-free survival was stratified by low/high levels of HALP in patients with tumor located at body/tail. D: Overall survival was stratified by low/high levels of HALP in patients with tumor located at body/tail. HALP: Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet.

DISCUSSION

Systemic inflammation and malnutrition are recognized as important components of cancer. The novel HALP index represents a combination of haemoglobin and albumin levels as well as lymphocyte and platelet counts. HALP reflects the status of both host inflammation and nutrition. In this study, we demonstrated that HALP was associated with lymph node metastasis, tumor differentiation and TNM staging. HALP was first verified as a significant predictor of RFS and OS in pancreatic cancer patients without hyperbilirubinemia following radical resection.

Systemic inflammation stimulates angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and the formation of supporting microenvironments that can promote the initiation, progression and metastasis of tumor cells[15,16]. The infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, lymphocytes and platelets, has been verified in tumor tissues to improve the classification of survival in pancreatic cancer. Counts of these inflammatory cells in serum are commonly acquired in clinical practice. Inflammation indices based on these counts of immune and inflammatory cells in peripheral blood, such as the NLR[17] and PLR[18], have also been demonstrated to improve the accuracy of survival prediction in pancreatic cancer. In the present study, both the NLR and PLR were associated with survival prediction in pancreatic cancer patients following radical resection. The HALP index, which was determined based on the counts of inflammatory cells, was positively correlated with both the NLR and PLR. Thus, HALP is considered a new potential marker which reflects systemic inflammation.

Anaemia is a common symptom in cancer patients. The association between decreased haemoglobin levels and poor quality of life has been demonstrated by randomized and controlled trials[19,20]. The low level of haemoglobin is correlated with a poor response to treatment and deteriorates survival, especially in patients with late-stage disease[21,22]. Serum albumin has been generally used to assess nutritional status and visceral protein synthesis function. Low levels of serum albumin have also been determined to be an independent risk factor for survival in pancreatic cancer patients[23,24]. Consistent with a previous study, the PNI, which is based on the levels of albumin, has been reported to improve the prediction of survival in pancreatic cancer patients[25,26]. More importantly, both haemoglobin and albumin synthesis might be inhibited by malnutrition and systemic inflammation in patients with extensive disease spread. The HALP index incorporates the factors of malnutrition (haemoglobin and albumin) with factors of the inflammatory response (counts of lymphocytes and platelets). HALP shows high superiority for predicting recurrence and survival in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Multivariate Cox regression demonstrated an independent and advantageous role for the HALP index in the prediction of prognosis. Notably, haemoglobin and albumin levels and lymphocyte and platelet counts are commonly measured in the clinic. The HALP index can be easily and inexpensively applied to monitor the treatment response and patient survival in clinical practice.

A significant correlation between HALP and sex was observed in the present study. Male patients were more likely to have a high level of HALP than female patients. The correlation between HALP and sex was mainly ascribed to the difference in haemoglobin levels between male and female patients (138.1 g/L for males and 127.1 g/L for females, P < 0.001). The lower limit of the normal values of haemoglobin in males and females was innate (120 g/L for males and 110 g/L for females). Subgroup analysis based on sex demonstrated that a low level of HALP was associated with early recurrence and short survival in both male and female patients. Additionally, sex had no significant association with recurrence or survival. Thus, HALP can be used for the prediction of prognosis irrespective of sex.

Patients with tumors located in the body/tail of the pancreas were more likely to have a high level of HALP than patients with tumors located in the head of the pancreas. In the present study, we excluded patients with obstructive jaundice because of the significant association between albumin and total bilirubin levels. However, the levels of albumin (43.2 g/L vs 44.5 g/L, P < 0.001) and haemoglobin (130.9 g/L vs 134.7 g/L, P < 0.001) were still significantly lower in patients with pancreatic head cancer. Pancreatic head cancer always causes the obstruction of bile ducts as well as the gastrointestinal tract and pancreatitis. It affects the nutrition status (haemoglobin and albumin levels) of cancer patients. When a tumor is located in the pancreatic body/tail, it always causes hypersplenism due to the obstruction of the splenic vein. Platelet counts are decreased by hypersplenism. Thus, the platelet count (185 × 109/L vs 210 × 109/L, P < 0.001) was significantly lower in patients with tumors in the pancreatic body/tail. As a result, the level of HALP was jointly increased in patients with tumors in the body/tail of the pancreas. We did not find a significant association between survival and tumor location in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Importantly, subgroup analysis based on tumor location demonstrated that a low level of HALP was associated with early recurrence and short survival irrespective of tumor location.

In conclusion, a low level of HALP was associated with lymph node metastasis, poor tumor differentiation and high TNM staging. A low level of HALP was suggested to be a significant risk factor for RFS and OS in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. The measurement of HALP is inexpensive, convenient, and necessary for the prediction of disease recurrence and survival.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Systemic inflammation and nutrition status are important factors in cancer metastasis. Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) consists of haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocytes, and platelets. It is considered the novel marker for both systemic inflammation and nutrition status.

Research motivation

No studies have investigated the relationship between HALP and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer following radical resection.

Research objectives

The study aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of preoperative HALP in pancreatic cancer patients.

Research methods

The relationship between postoperative survival and the preoperative level of HALP was investigated in 582 pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients who underwent radical resection.

Research results

Low levels of HALP were significantly associated with lymph node metastasis (P = 0.002), poor tumor differentiation (P = 0.032), high TNM stage (P = 0.008), female patients (P = 0.005) and tumor location in the head of the pancreas (P < 0.001). Low levels of HALP were associated with early recurrence [7.3 mo vs 16.3 mo, P < 0.001 for recurrence-free survival] and short survival [11.5 mo vs 23.6 mo, P < 0.001 for overall survival] for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A low level of HALP was an independent risk factor for early recurrence and short survival irrespective of sex and tumor location.

Research conclusions

Low levels of HALP could serve as a significant risk factor for recurrence-free survival and overall survival in patients with resected pancreatic cancer.

Research perspectives

The measurement of HALP is necessary for the prediction of disease recurrence and survival in patients with resected pancreatic cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate the support and help from Dr. Ze-Zhou Wang and Dr. Jin Fan.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center.

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent has been acquired from each patient.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no conflicts-of-interest related to this article.

Peer-review started: November 23, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2019

Article in press: January 15, 2020

P-Reviewer: Hoyos S S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: MedE-Ma JY E-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Shuai-Shuai Xu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Shuo Li, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Hua-Xiang Xu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Hao Li, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Chun-Tao Wu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Wen-Quan Wang, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

He-Li Gao, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Wang Jiang, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Wu-Hu Zhang, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Tian-Jiao Li, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Quan-Xing Ni, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Liang Liu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Xian-Jun Yu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Fudan University, Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai 20032, China; Pancreatic Cancer Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China. yuxianjun@fudanpci.org.

References

- 1.Strobel O, Neoptolemos J, Jäger D, Büchler MW. Optimizing the outcomes of pancreatic cancer surgery. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:11–26. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Roessel S, Kasumova GG, Verheij J, Najarian RM, Maggino L, de Pastena M, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Salvia R, Ng SC, de Geus SW, Lof S, Giovinazzo F, van Dam JL, Kent TS, Busch OR, van Eijck CH, Koerkamp BG, Abu Hilal M, Bassi C, Tseng JF, Besselink MG. International Validation of the Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging System in Patients With Resected Pancreatic Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e183617. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone ML, Beatty GL. Cellular determinants and therapeutic implications of inflammation in pancreatic cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;201:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elaskalani O, Falasca M, Moran N, Berndt MC, Metharom P. The Role of Platelet-Derived ADP and ATP in Promoting Pancreatic Cancer Cell Survival and Gemcitabine Resistance. Cancers (Basel) 2017:9. doi: 10.3390/cancers9100142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlick K, Magnes T, Huemer F, Ratzinger L, Weiss L, Pichler M, Melchardt T, Greil R, Egle A. C-Reactive Protein and Neutrophil/Lymphocytes Ratio: Prognostic Indicator for Doubling overall survival Prediction in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. J Clin Med. 2019:8. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirai Y, Shiba H, Sakamoto T, Horiuchi T, Haruki K, Fujiwara Y, Futagawa Y, Ohashi T, Yanaga K. Preoperative platelet to lymphocyte ratio predicts outcome of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreatic resection. Surgery. 2015;158:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe T, Nakata K, Kibe S, Mori Y, Miyasaka Y, Ohuchida K, Ohtsuka T, Oda Y, Nakamura M. Prognostic Value of Preoperative Nutritional and Immunological Factors in Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3996–4003. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6761-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen XL, Xue L, Wang W, Chen HN, Zhang WH, Liu K, Chen XZ, Yang K, Zhang B, Chen ZX, Chen JP, Zhou ZG, Hu JK. Prognostic significance of the combination of preoperative hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet in patients with gastric carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Oncotarget. 2015;6:41370–41382. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang H, Li H, Li A, Tang E, Xu D, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Tang M, Zhang Z, Deng X, Lin M. Preoperative combined hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet levels predict survival in patients with locally advanced colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:72076–72083. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng D, Zhang CJ, Tang Q, Zhang L, Yang KW, Yu XT, Gong Y, Li XS, He ZS, Zhou LQ. Prognostic significance of the combination of preoperative hemoglobin and albumin levels and lymphocyte and platelet counts (HALP) in patients with renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy. BMC Urol. 2018;18:20. doi: 10.1186/s12894-018-0333-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Y, Shi D, Zhang J, Mao S, Wang L, Zhang W, Zhang Z, Jin L, Yang B, Ye L, Yao X. The Hemoglobin, Albumin, Lymphocyte, and Platelet (HALP) Score is a Novel Significant Prognostic Factor for Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer Undergoing Cytoreductive Radical Prostatectomy. J Cancer. 2019;10:81–91. doi: 10.7150/jca.27210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin W, Xu HX, Zhang SR, Li H, Wang WQ, Gao HL, Wu CT, Xu JZ, Qi ZH, Li S, Ni QX, Liu L, Yu XJ. Tumor-Infiltrating NETs Predict Postsurgical Survival in Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:635–643. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6941-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L, Xu H, Wang W, Wu C, Chen Y, Yang J, Cen P, Xu J, Liu C, Long J, Guha S, Fu D, Ni Q, Jatoi A, Chari S, McCleary-Wheeler AL, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Li M, Yu X. A preoperative serum signature of CEA+/CA125+/CA19-9 ≥ 1000 U/mL indicates poor outcome to pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2216–2227. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichikawa K, Mizuno S, Hayasaki A, Kishiwada M, Fujii T, Iizawa Y, Kato H, Tanemura A, Murata Y, Azumi Y, Kuriyama N, Usui M, Sakurai H, Isaji S. Prognostic Nutritional Index After Chemoradiotherapy Was the Strongest Prognostic Predictor Among Biological and Conditional Factors in Localized Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients. Cancers (Basel) 2019:11. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity. 2019;51:27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalapour S, Karin M. Pas de Deux: Control of Anti-tumor Immunity by Cancer-Associated Inflammation. Immunity. 2019;51:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stotz M, Gerger A, Eisner F, Szkandera J, Loibner H, Ress AL, Kornprat P, AlZoughbi W, Seggewies FS, Lackner C, Stojakovic T, Samonigg H, Hoefler G, Pichler M. Increased neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is a poor prognostic factor in patients with primary operable and inoperable pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:416–421. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikuta S, Sonoda T, Aihara T, Yamanaka N. A combination of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 predict early recurrence after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:461. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.08.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjoquist KM, Renfro LA, Simes RJ, Tebbutt NC, Clarke S, Seymour MT, Adams R, Maughan TS, Saltz L, Goldberg RM, Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Douillard JY, Hoff PM, Hecht JR, Tournigand C, Punt CJA, Koopman M, Hurwitz H, Heinemann V, Falcone A, Porschen R, Fuchs C, Diaz-Rubio E, Aranda E, Bokemeyer C, Souglakos I, Kabbinavar FF, Chibaudel B, Meyers JP, Sargent DJ, de Gramont A, Zalcberg JR Fondation Aide et Recherche en Cancerologie Digestive Group (ARCAD) Personalizing Survival Predictions in Advanced Colorectal Cancer: The ARCAD Nomogram Project. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:638–648. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Almeida JP, Vincent JL, Galas FR, de Almeida EP, Fukushima JT, Osawa EA, Bergamin F, Park CL, Nakamura RE, Fonseca SM, Cutait G, Alves JI, Bazan M, Vieira S, Sandrini AC, Palomba H, Ribeiro U, Jr, Crippa A, Dalloglio M, Diz Mdel P, Kalil Filho R, Auler JO, Jr, Rhodes A, Hajjar LA. Transfusion requirements in surgical oncology patients: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:29–38. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhindi B, Hermanns T, Wei Y, Yu J, Richard PO, Wettstein MS, Templeton A, Li K, Sridhar SS, Jewett MA, Fleshner NE, Zlotta AR, Kulkarni GS. Identification of the best complete blood count-based predictors for bladder cancer outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:207–212. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrane JM, Humes DJ, Acheson AG, Minear F, Wheeler JMD, Walter CJ. Significance of Anemia in Outcomes After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alagappan M, Pollom EL, von Eyben R, Kozak MM, Aggarwal S, Poultsides GA, Koong AC, Chang DT. Albumin and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) Predict Survival in Patients With Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Treated With SBRT. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41:242–247. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruiz-Tovar J, Martín-Pérez E, Fernández-Contreras ME, Reguero-Callejas ME, Gamallo-Amat C. Impact of preoperative levels of hemoglobin and albumin on the survival of pancreatic carcinoma. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:631–636. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082010001100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakagawa K, Sho M, Akahori T, Nagai M, Nakamura K, Takagi T, Tanaka T, Nishiofuku H, Ohbayashi C, Kichikawa K, Ikeda N. Significance of the inflammation-based prognostic score in recurrent pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2019;19:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.05.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geng Y, Qi Q, Sun M, Chen H, Wang P, Chen Z. Prognostic nutritional index predicts survival and correlates with systemic inflammatory response in advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1508–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]