Abstract

Elevations in circulating levels of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) are associated with a variety of cardiometabolic diseases and conditions. Restriction of dietary BCAAs in rodent models of obesity lowers circulating BCAA levels and improves whole-animal and skeletal-muscle insulin sensitivity and lipid homeostasis, but the impact of BCAA supply on heart metabolism has not been studied. Here, we report that feeding a BCAA-restricted chow diet to Zucker fatty rats (ZFRs) causes a shift in cardiac fuel metabolism that favors fatty acid relative to glucose catabolism. This is illustrated by an increase in labeling of acetyl-CoA from [1-13C]palmitate and a decrease in labeling of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA from [U-13C]glucose, accompanied by a decrease in cardiac hexokinase II and glucose transporter 4 protein levels. Metabolomic profiling of heart tissue supports these findings by demonstrating an increase in levels of a host of fatty-acid-derived metabolites in hearts from ZFRs and Zucker lean rats (ZLRs) fed the BCAA-restricted diet. In addition, the twofold increase in cardiac triglyceride stores in ZFRs compared with ZLRs fed on chow diet is eliminated in ZFRs fed on the BCAA-restricted diet. Finally, the enzymatic activity of branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) is not influenced by BCAA restriction, and levels of BCAA in the heart instead reflect their levels in circulation. In summary, reducing BCAA supply in obesity improves cardiac metabolic health by a mechanism independent of alterations in BCKDH activity.

Keywords: branched-chain amino acids, cardio metabolic diseases, heart metabolism, obesity, Zucker fatty rat

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, nearly 40% of adults have obesity, with the prevalence expected to rise over the coming years (4). Obesity raises the risk for chronic cardiometabolic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure (6). The mechanisms underlying obesity-related cardiac dysfunction are still incompletely resolved. Studies in humans with obesity suggest an association with increased fatty-acid uptake, coupled with impaired fatty-acid oxidation and triglyceride (TG) mobilization, leading to accumulation of cardiac TG stores (16). TG accumulation is also associated with impaired heart function in rodent models of obesity, including the Zucker fatty rat (ZFR) (5, 22).

Over the past decade, the use of unbiased metabolic-profiling technologies has identified several biomarkers that are associated with obesity-related health disorders and outcomes. Among these, the branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs; valine, leucine, and isoleucine) and related metabolites have emerged as robust markers of obesity-related diseases (11, 14). Although the association of BCAAs with human obesity was first described in the 1960s (1), our group and others have shown that this more broadly encompasses BCAAs and products of their tissue catabolism (15). More recently, mechanisms underlying these associations are beginning to emerge (13, 14, 20, 21).

Similar to humans who have obesity and insulin resistance, the ZFR model exhibits spontaneous elevations in circulating BCAA concentrations, driven mainly by lower rates of BCAA oxidation in liver and adipose tissue (17, 20). We have previously shown that restricting the dietary supply of BCAA by 45% in ZFRs normalizes circulating BCAA concentrations to the level of control Zucker lean rats (ZLRs) (19). This results in lowering of lipid-derived metabolites in skeletal muscle, associated with improvements in whole-animal insulin sensitivity and enhanced glucose uptake and glycogen storage in muscle. However, the effects of dietary restriction of BCAA on cardiac metabolism have not been reported. Using a combination of targeted metabolomics and metabolic flux analysis, we demonstrate here that chronic dietary BCAA restriction in ZFRs decreases glucose oxidation while increasing fatty-acid oxidation in the heart. These changes in cardiac substrate utilization are accompanied by a reduction in the cardiac TG pool, suggesting that dietary BCAA restriction may lead to more healthful utilization of lipids by the heart in obese and insulin-resistant states.

METHODS

Animals and diets.

As previously described (19), 6-wk-old male ZLRs and ZFRs from Charles River Laboratories were placed on either a low-fat diet (A11072001, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or a low-fat diet in which 45% of BCAAs were removed and replaced with a small increment of all other amino acids except phenylalanine and tyrosine (A11072002, Research Diets), such that the two diets were isonitrogenous and isocaloric. Rats were individually housed in a 12-h light:dark cycle with ad libitum access to water and 1 of the 2 diets for 15 wk. Food intake and weight gain were monitored weekly. Plasma and tissue samples used for biochemical analyses were taken from rats euthanized at wk 15 in the fed state between 9:00 AM and 11:00 AM by exsanguination following intraperitoneal administration of Nembutal (80 mg/kg). Tissues (liver, brown adipose, white adipose, gastrocnemius, and heart) were rapidly excised, weighed, and freeze clamped in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C until further analysis. The hearts from this cohort of animals were used to perform metabolomics analyses described below. A second cohort of 6-wk-old male ZFRs underwent the same 15-wk dietary intervention and were used for the isolated heart-perfusion studies. All animal procedures were approved and carried out in compliance with the guidelines of the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolated heart perfusions.

Fed ZFRs were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, and isolated beating hearts were perfused in the Langendorff mode at 37°C with nonrecirculating perfusate. For the first 15-min equilibration period, hearts were perfused with Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer containing 119 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 2.6 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 11 mM glucose, and 0.05 mM L-carnitine at a flow rate of 12 mL/min (7, 8, 18). The hearts were then perfused for 30 min with Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer with the following additions: 3% BSA (fatty acid free; Fisher Scientific), 100 μU/mL insulin, 5.5 mM unlabeled glucose, 5.5 mM [U-13C]glucose (Cambridge Isotopes), and 0.4 mM [1-13C]palmitate (Cambridge Isotopes) bound to BSA. Amino acids were also included in the perfusate at levels measured in plasma of ZFRs fed the control diet and BCAA-restricted diet (19). At the end of each perfusion, hearts were freeze clamped in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Metabolite profiling.

Targeted amino acid, acylcarnitine, and acyl-CoA analyses were performed by previously described mass spectrometry methods (15, 19) using heart samples collected at the end of a prior feeding study (19) or heart samples collected at the end of the current perfusion studies. All mass spectrometry analyses employed stable isotope dilution with internal standards as described in Refs. 2 and 15. Cardiac TG was quantified using a kit from Abcam (ab65336), correcting for glycerol content as previously described (20). To measure malonyl-CoA levels, heart samples were extracted with 0.3 M perchloric acid, and [13C3]malonyl-CoA (Sigma, MO) was added to the fresh extract, which was then centrifuged and filtered through a Millipore Ultrafree-MC 0.1-μm centrifugal filter before being injected onto a Chromolith FastGradient RP-18e HPLC column (EMD Millipore). The column outflow was analyzed on a Waters Xevo TQ-S triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

Branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase activity assay.

Cardiac branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) activity was determined as previously described (20). Briefly, frozen tissue samples were pulverized in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized using a QIAGEN TissueLyser II in 250 μL of ice-cold buffer I (30 mM KPi pH 7.5, 3 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM α-ketoisovalerate, 3% FBS, 5% Triton X-100, 1 μM Leupeptin). Samples were then centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g, and 50 μL of supernatant was added to 300 μL of buffer II (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 30 mM KPi pH 7.5, 0.4 mM CoA, 3 mM NAD+, 5% FBS, 2 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 2 mM MgCl2, and 7.8 μM α-keto [1-14C] isovalerate) in a polystyrene test tube containing a raised 1-M NaOH CO2 trap. Tubes were capped and placed in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction mixture was acidified by injection of 70% perchloric acid followed by shaking on an orbital shaker for 1 h. The 14CO2 contained in the trap was counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

Stable isotope-resolved metabolite profiling.

The method used for measurement of acyl-CoA metabolites by LC-MS/MS was previously described (9). An internal standard (0.2 nmol [2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,5-2H9]pentanoyl-CoA) was added to samples during homogenization. For the measurements involving acetyl-CoA labeling derived from [1-13C]palmitate, we assumed complete oxidation of each labeled palmitate molecule and multiplied the labeled acetyl-CoA concentration by a factor of 8.

2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate measurements.

2-Deoxyglucose-6-phosphate was quantified using LC-Q-Exactive+-MS with a Microsorb-MV C18 column (100 × 4.6 mm, 3 μm), as previously described (18).

Reverse transcription real-time quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from heart tissue using TRI REAGENT (T9474, Sigma). cDNA was generated using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using TaqMan gene expression assays for hexokinase HKII (Rn00562457) and PowerUp SYBr Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystem) for all other genes on a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystem) using specific primers. mRNA levels were normalized to Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A (PPIA) and 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 (RPLP0) mRNA and fold induction was calculated using the delta delta threshold cycle method. The following primers were used: PPIA [forward (fw): GCATACGGGTCCTGGCATCTTGTCC, reverse (rev): ATGGTGATCTTCTTGCTGGTCTTGC]; Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPARA) (fw: CAGATGAGTCCCCTGGCAAT, rev: GCGTGGACTCCATAGTGGTA); Perilipin 5 (PLIN5) (fw: TGCCCATGACTGAAGCTGAG, rev: ACGCACAAAGTAGCCCTGTT); PLIN2 (fw: CCGTAACTGGGGCAAAGGAT, rev: CCTGAGACTGTGCTGGCTAC); PLIN3 (fw: GGCTGGATAGACTGCAGGAG, rev: AGCCCCAGACACTGTTGATG); carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT)1A (fw: CTTATCGTGGTGGTGGGTGT, rev: AGGGTCCGACTGATCTTTGC); CPT1B (fw: AGAACACGAGCCAACAAGCA, rev: TCTTCTCGGTCCAGTTTGCG); MONDOA (fw: AGCAGACGTGCCAGACCTA, rev: TCAAAGAGCTTGGTGAGCGA); glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 (fw: CTTATGTTGGCCGTGGGAGG, rev: GCGGTGGTTCCATGTTTGAT); GLUT4 (fw: CCATGGCTGTAGCTGGTTTC, rev: GGAGGACGGCAAATAGAAGG); HK1 (fw: AACAGCCTCCGTCAAGATGC, rev: CCGAGATCCAGGGCAATGAAA); 3-Oxoacid CoA-Transferase 1 (OXCT1) (fw: TGCCTGCTACTTTTCCGTCA, rev: CACAACCCGAAACCACCAAC); CPT2 (fw: ATTTTGAGACTGGCGTTGGG, rev: CTGAGATGTAGCTGGTGTGCT); Heart-type fatty acid binding protein (HFABP) (fw: TGACCAAGCCGACCACAATC, rev: GACCTCGTCAAACTCTACTCCC); uncoupling protein 2 (fw: TCGCTTGCTTCTTGGGCAG, rev: GGACCGCAGGAGAATACACAG); and uncoupling protein 3 (fw: TTCTACACCCCCAAAGGAACG, rev: CATCCGTGGGTTGAGCACAG).

Immunoblot analyses.

Tissue lysates were prepared in Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies) containing protease inhibitor tablets (A32961, Thermo) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktails 2 and 3 (P5726 and P0044, Sigma). Thirty milligrams of protein were loaded onto 4%–15% precast polyacrylamide gels (456–8086, Bio-Rad) and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk for 1 h before probing with primary antibodies for AKT (9272), phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT; 9271), HKII (2867), pan-actin (8456) (Cell Signaling), GLUT1 (ab652), GLUT4 (ab654; Abcam), or β-tubulin (T8328; Sigma). All primary antibodies were diluted 1:1,000, whereas secondary antibodies were diluted 1:10,000. Immunoblots were quantified using the Li-Cor Image Studio software, and density was normalized to pan-actin or β-tubulin.

Statistical analyses.

All data are reported as mean ± the standard error. For studies comparing all four experimental groups, a full factorial ANOVA was performed in JMP Pro 12 to evaluate diet and genotype effects followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference post hoc test for all pairwise multiple comparisons. For heart-perfusion studies in which only ZFRs fed the two diets were compared, an unpaired two-sided student's t test was performed in Excel. In all cases, a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Dietary BCAA restriction increases fatty-acid oxidation and decreases glucose utilization in perfused hearts from ZFRs.

To characterize the effects of dietary BCAA restriction on cardiac metabolism, we performed metabolic flux analysis in isolated perfused hearts from ZFRs fed standard chow or a BCAA-restricted diet for 15 wk. During the perfusions, we maintained amino acid concentrations at the levels found in the circulation of ZFRs fed the normal or BCAA-restricted diets, respectively. The hearts simultaneously received [U-13C]glucose and [1-13C]palmitate to allow measurement of the contribution of each substrate to the acetyl-CoA pool based on differential labeling. The basis of this method is that [1-13C]palmitate will generate the acetyl-CoA isomer containing one heavy atom (M + 1), whereas labeling by [U-13C] glucose will produce the isomer containing two heavy atoms (M + 2) (Fig. 1A); these mass isotopomer species are readily separated and quantified by LC-MS/MS (9, 11). We chose the acetyl-CoA pool as a readout of substrate utilization given the intense label scrambling that occurs in downstream metabolites during multiple turns of the TCA cycle, making interpretation of label incorporation into TCA cycle intermediates other than acetyl-CoA complex and unreliable (7).

Fig. 1.

Dietary branched-chain amino acid restriction alters fuel selection in isolated Zucker fatty rat (ZFR) hearts. Male ZFR were fed chow diet (Obese control) or a chow diet in which BCAA were restricted by 45% (Obese restr) for 15 wk. The hearts were then isolated and perfused with [1-13C]palmitate and [U-13C]glucose. A: labeling strategy and 13C enrichment in the acetyl-CoA pool. B: 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate concentrations. C: 13C enrichment in the malonyl-CoA pool. n = 7–8 per group. Data represent mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005. 2DG6P, 2 deoxyglucose-6-phosphate; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase.

Dietary BCAA restriction increased 13C-label incorporation into acetyl-CoA derived from palmitate with a corresponding decrease in 13C acetyl-CoA label derived from glucose (Fig. 1A). These changes were accompanied by a trend (P = 0.06) for decreased glucose uptake and phosphorylation in hearts from ZFRs fed the BCAA-restricted diet, as measured by cardiac 2-deoxy-glucose-6-phosphate concentrations (Fig. 1B). We also measured a clear decrease in 13C labeling of malonyl-CoA derived from glucose (Fig. 1C). Malonyl-CoA is directly synthesized from acetyl-CoA via the acetyl-CoA carboxylase reaction, and its decreased labeling from glucose parallels a similar decrease in labeling of acetyl-CoA. Taken together, these findings suggest that dietary BCAA restriction in ZFRs decreases cardiac glucose uptake, phosphorylation, and catabolism while simultaneously increasing the efficiency of fatty-acid oxidation to acetyl-CoA.

Dietary BCAA restriction affects levels of metabolites involved in fatty-acid oxidation in ZFR and ZLR hearts.

To determine if our findings in the isolated perfused heart are reflective of changes in cardiac metabolism in vivo, we applied targeted metabolomics to frozen heart tissues taken from a cohort of ZLRs and ZFRs fed standard chow or BCAA-restricted diets. Details of the physiologic and metabolic phenotypes of these animals (not including cardiac phenotypes) are reported in a prior publication (19). Notably, at the end of the 15-wk study period, circulating TG, nonesterified fatty acid, glucose, and insulin concentrations were not different between the ZFRs fed standard chow or BCAA-restricted diets (19).

Targeted acylcarnitine analysis revealed that dietary BCAA restriction caused small increases in a subset (C16:2, C18, C18:1) of long, even-chain, nonhydroxylated acylcarnitines in heart tissue in both ZLRs and ZFRs (Fig. 2A). BCAA restriction had a more pronounced effect to increase the levels of a larger set of long, even-chain, hydroxylated acylcarnitines (C16-OH, C16:1-OH, C16:2-OH, C18-OH, C18:1-OH, C18:2-OH) in the same heart samples (Fig. 2B). Hydroxylated versions of the primary acylcarnitine species are generated at the second enzymatic step (enoyl-CoA hydratase) of the fatty-acid β-oxidation sequence.

Fig. 2.

Effect of dietary branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) restriction on fatty-acid oxidation-related metabolites. Zucker lean rats and Zucker fatty rats (ZFRs) were fed a chow diet (lean control and obese control, respectively) or BCAA-restricted diet (lean restr, and obese restr, respectively). Even-chain acylcarnitine (AC) concentrations (A), even-chain hydroxylated-acylcarnitine (OH-AC) concentrations (B), and acyl-CoA concentrations (C) in snap-frozen hearts from a previously described animal cohort (19). n = 9–15 per group. Acyl-CoA concentrations (D) in hearts from ZFRs fed a chow diet (obese control) or BCAA-restricted diet (obese restr) snap frozen at the conclusion of the perfusion study described in Fig. 1. n = 7–8 per group. Data represent mean ± SE. Statistical differences indicated by: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 for obesity effect and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.005 for diet effect.

Acyl-CoA profiling revealed that the levels of lauroyl, myristoyl, palmitoyl, and oleoyl CoAs trended higher in standard chow-fed ZFRs compared with standard chow-fed ZLRs (Fig. 2C). These CoA species are derived from endogenously synthesized fatty acids. In contrast, levels of linolenoyl and linoleoyl CoAs derived from dietary, polyunsaturated fatty acids were lower in standard chow-fed ZFRs compared with ZLRs (Fig. 2C). BCAA restriction tended to increase the levels of all of these acyl-CoA species in both ZFRs and ZLRs (Fig. 2C). Overall, BCAA restriction increased levels of the direct substrates for the fatty-acid oxidation spiral (nonhydroxylated acylcarnitines and long-chain acyl-CoA species) and caused a more pronounced increase in intermediates generated during the oxidation process (hydroxylated acylcarnitines). These changes are consistent with an effect of BCAA restriction to increase flux of fatty acids through the β-oxidation pathway, supporting the finding of increased acetyl-CoA enrichment from [1-13C]palmitate summarized in Fig. 1.

We also profiled long-chain acyl-CoA levels in hearts following the perfusion studies described in Fig. 1. Interestingly, under these circumstances, hearts from BCAA-restricted ZFRs had lower levels of all long-chain acyl-CoA species compared with hearts from standard chow-fed ZFRs (Fig. 2D). One important difference between the data shown in Fig. 2C and the data shown in Fig. 2D is that hearts freshly isolated from ZFRs and profiled for acyl-CoA levels (Fig. 2C) were chronically exposed in vivo to a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, particularly in hyperlipidemic ZFRs, whereas the perfused hearts were only exposed to 0.4 mM palmitate during the 30-min perfusion procedure (Fig. 2D). These findings suggest that the larger pool of long-chain acyl-CoA and acylcarnitine species in freshly isolated hearts from BCAA-restricted ZFRs (Fig. 2, A–C) are readily consumed when exogenous lipid supply is reduced during perfusion. Overall, the data in Figs. 1 and 2 support the conclusion that hearts from ZFRs fed the BCAA-restricted diet undergo a shift toward oxidation of fatty acids, an energetically efficient fuel, and away from glucose oxidation.

We also measured malonyl-CoA levels by a targeted LC-MS/MS assay in both the freshly isolated and perfused hearts, given the important role ascribed to malonyl-CoA as an allosteric inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) (12). Despite a lower rate of conversion of [13C-U]glucose to malonyl-CoA in hearts from BCAA-restricted animals reported in Fig. 1, malonyl-CoA levels were not affected by animal genotype (ZLR vs. ZFR: 0.128 ± 0.036 pmol/mg vs. 0.130 ± 0.011 pmol/mg) or BCAA restriction, either in freshly isolated (obese control vs. obese restricted: 0.130 ± 0.011 pmol/mg vs. 0.137 ± 0.004 pmol/mg) or perfused heart samples (obese control vs. obese restricted: 0.057 ± 0.036 pmol/mg vs. 0.054 ± 0.005 pmol/mg). Thus, it does not appear that changes in cardiac malonyl-CoA levels are responsible for the shift in fuel selection from glucose to fatty acids that occurs in response to BCAA restriction.

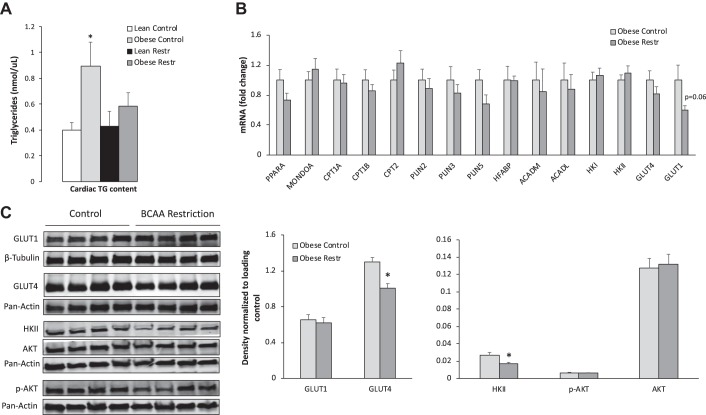

Dietary BCAA restriction normalizes cardiac triglyceride content in Zucker fatty rats.

Our prior study in ZFRs showed that dietary BCAA restriction lowered the levels of a host of lipid-derived acyl-CoA and acylcarnitine species in skeletal muscle, suggesting improved efficiency of skeletal-muscle fatty-acid oxidation in response to this dietary maneuver (19). We hypothesized that similar improvements in lipid homeostasis might occur in the hearts of these animals, leading to reduced cardiac TG stores. We found that ZFRs fed a standard diet had nearly twice the level of cardiac TG compared with ZLRs. Dietary BCAA restriction lowered cardiac TG levels in ZFRs by ~40%, reaching levels indistinguishable from those in hearts of ZLRs (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Effect of dietary branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) restriction on cardiac triglyceride (TG) concentrations, gene expression, and protein abundance. A: Zucker lean rats and Zucker fatty rats (ZFRs) were fed a chow diet (lean control and obese control, respectively) or BCAA-restricted diet (lean restr and obese restr, respectively) and cardiac TG concentrations were measured. n = 9–15 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. lean control. B: mRNA levels in perfused hearts from ZFR fed a chow diet (obese control) or BCAA-restricted diet (obese restr). C: representative immunoblots of glucose transporter (GLUT) 1, GLUT4, hexokinase (HK) II, phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT), and AKT with indicated loading controls and corresponding densitometric measurements. n = 7–8 per group. Data represent mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 for diet effect. CPT, carnitine palmitoyltransferase.

Expression of genes and proteins related to metabolic fuel selection.

To investigate mechanisms underlying the increase in fatty-acid oxidation and decrease in glucose utilization with dietary BCAA restriction, we measured mRNA transcripts encoding PPARα, MONDOA, CPT1a, CPT1b, CPT2, PLIN2, PLIN3, PLIN5, HFABP, ACADM, ACADL, HKI, HKII, GLUT1, and GLUT4. BCAA restriction had no significant effect on transcripts from these genes, although there was a trend for BCAA restriction to lower GLUT1 mRNA (P = 0.06) (Fig. 3B). We also measured the abundance of several key proteins. We found no significant decrease in GLUT1 protein in response to BCAA restriction, but we did observe a significant decrease in GLUT4 and HKII protein levels, which serve as the major glucose transporter and glucose phosphorylating enzyme in the heart, respectively (Fig. 3C). The decreases in GLUT4 and HKII protein are consistent with the decrease in glucose uptake, phosphorylation, and conversion to acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA observed in hearts from ZFRs fed the BCAA-restricted diet. We also tested the idea that BCAA restriction might alter substrate selection secondary to an effect on insulin sensitivity. However, we found no differences in p-AKT or total AKT protein levels in the two dietary groups, suggesting that BCAA restriction does not affect insulin signaling in the heart (Fig. 3C).

The effect of dietary BCAA restriction on cardiac BCAA metabolism in ZFRs.

We next measured the levels of BCAA and their catabolic products in heart samples. Valine but not Leu/Ile levels were significantly elevated in ZFR compared with ZLR hearts (Fig. 4A). Dietary restriction of BCAA decreased BCAA levels in hearts from both ZFRs and ZLRs (Fig. 4A). Obesity had no effect on cardiac C3, C5, and C3-OH/C5-dicarboxylate acylcarnitines, which are products of BCAA catabolism. However, all three metabolites were significantly lowered in response to dietary BCAA restriction in both the ZFR and ZLR models (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of dietary branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) restriction on cardiac BCAA metabolism. Zucker lean rats and Zucker fatty rats were fed a chow diet (lean control and obese control, respectively) or a BCAA-restricted diet (lean restr and obese restr, respectively). A: BCAA concentrations. B: concentrations of BCAA catabolic products C3, C5, and C5-OH/C3-DC acylcarnitines. C: activity of the rate-limiting enzyme in BCAA catabolism, branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH). Data represent mean ± SE. Statistical differences indicated by: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 for obesity effect and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.005 for diet effect. KIV, alpha-keto-isovalerate; Leu/Ile, leucine/isoleucine; Val, valine.

To determine whether obesity or diet influence the rate-limiting step of BCAA catabolism in the heart, we measured activity of branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH). Unlike what has been observed previously in liver and adipose tissue (19), cardiac BCKDH activity was not affected by obesity (Fig. 4C). BCAA restriction also had no effect on BCKDH activity in hearts of ZFRs or ZLRs (Fig. 4C). Thus, lower levels of the C3 and C5 acylcarnitines in the hearts of rats fed the BCAA-restricted diet are likely the result of reduced cardiac BCAA supply and uptake rather than a change in BCKDH activity.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that dietary BCAA restriction in genetically obese ZFRs results in a shift in cardiac substrate utilization, leading to lowering of the cardiac TG pool. Using metabolic flux analysis in perfused hearts, we demonstrate that the effect of dietary BCAA restriction on cardiac TG content likely occurs as a result of a change in metabolic fuel selection that favors fatty-acid oxidation over glucose utilization. These observations align with decreases in protein abundance of GLUT4 and HKII as well as the higher levels of fatty acid-derived even-chain acylcarnitines and acyl-CoA metabolites in hearts of rats fed the BCAA-restricted diet, particularly the hydroxylated-acylcarnitine species generated by the second enzymatic step of the β-oxidation spiral. These findings suggest that the increases in circulating BCAA known to occur in obesity could play a role in cardiac dysfunction by shifting metabolic fuel selection from fatty acids to glucose, a less energetically favorable substrate, and promoting harmful lipid accumulation.

At first glance our finding of lower glucose oxidation in hearts from ZFRs fed the BCAA-restricted diet is seemingly at odds with a prior study in which whole-body deletion of the BCKDH phosphatase Protein phosphatase M1K (PPM1K) was used to clamp BCKDH in a phosphorylated and inactive state (10). In that model, the authors reported an increase in BCAA levels coupled with impairment of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and decreased rates of cardiac glucose oxidation in contrast with our finding of a decrease in glucose catabolism in response to lowering of BCAA levels. However, a major difference in the studies is the absence of changes in cardiac BCKDH activity in either ZFRs or ZLRs in response to the BCAA-restricted diet. We also note that the BCKDH kinase, BDK, and the PPM1K phosphatase have substrates in addition to BCKDH, including the key lipogenic enzyme ATP-citrate lyase (20); these alternative activities of BDK and PPM1K may have contributed to the cardiac phenotypes observed in global PPM1K knockout mice. In sum, our study defines unique salutary effects of BCAA restriction on cardiac fuel metabolism that are independent of alterations in BCKDH activity.

Another recent report suggests that cardiac BCAA oxidation may be impaired in mice rendered insulin resistant by feeding of a high-fat diet (3). Oxidation of uniformly labeled 14C BCAA to 14CO2 was found to be 50% lower in isolated working hearts from high-fat diet-fed mice compared with chow-fed mice. However, the mechanism of this BCAA metabolic defect is unclear, since the lower rate of BCAA oxidation could not be accounted for by altered BCKDH phosphorylation, mitochondrial branched-chain amino acid transaminase expression, or changes in the levels of BDK or PPM1K. In our model, decreases in cardiac levels of BCAA and their downstream metabolites in response to BCAA restriction were well correlated with the lower levels of circulating BCAA in both the obese ZFR and lean ZLR strains, suggesting no intrinsic obesity-driven deficit in BCAA catabolism. It remains possible that obesity influences enzymes of BCAA metabolism distal to BCKDH, a topic for future investigation.

In summary, using a chronic dietary intervention in an animal model of obesity, we show that normalization of circulating BCAA increases fatty-acid oxidation and normalizes cardiac TG levels. Adding to prior findings that dietary BCAA restriction enhances whole-body and skeletal-muscle insulin sensitivity and lipid homeostasis (19), the current study suggests that reducing BCAA delivery to the heart in obesity may improve cardiac metabolic health.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH Grants DK-58398 and DK-78669 (to C. B. Newgard), K08-HL-135275 (to R. W. McGarrah), American Heart Association Grant 16SFRN31800000 (to R. W. McGarrah) and an American Diabetes Association Pathway to Stop Diabetes Award 1-16-INI-17 (to P. J. White).

DISCLOSURES

C. B. Newgard is a member of the Eli Lilly and Company Global Diabetes Scientific Advisory Board.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.W.M., G.-F.Z., B.A.C., P.J.W., and C.B.N. conceived and designed research; R.W.M., G.-F.Z., B.A.C., Y.D., J.M.W., S.P., and O.I. performed experiments; R.W.M., G.-F.Z., B.A.C., Y.D., J.M.W., S.P., O.I., P.J.W., and C.B.N. analyzed data; R.W.M., G.-F.Z., J.M.W., P.J.W., and C.B.N. interpreted results of experiments; R.W.M., G.-F.Z., J.M.W., P.J.W., and C.B.N. prepared figures; R.W.M., G.-F.Z., P.J.W., and C.B.N. drafted manuscript; R.W.M., G.-F.Z., B.A.C., J.M.W., P.J.W., and C.B.N. edited and revised manuscript; R.W.M., G.-F.Z., B.A.C., Y.D., J.M.W., S.P., O.I., P.J.W., and C.B.N. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Felig P, Marliss E, Cahill GF Jr. Plasma amino acid levels and insulin secretion in obesity. N Engl J Med 281: 811–816, 1969. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196910092811503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara CT, Wang P, Neto EC, Stevens RD, Bain JR, Wenner BR, Ilkayeva OR, Keller MP, Blasiole DA, Kendziorski C, Yandell BS, Newgard CB, Attie AD. Genetic networks of liver metabolism revealed by integration of metabolic and transcriptional profiling. PLoS Genet 4: e1000034, 2008. [Erratum in: PLoS Genet 4: 2008.] doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fillmore N, Wagg CS, Zhang L, Fukushima A, Lopaschuk GD. Cardiac branched-chain amino acid oxidation is reduced during insulin resistance in the heart. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 315: E1046–E1052, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00097.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief: 1–8, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holloway GP, Snook LA, Harris RJ, Glatz JFC, Luiken JJFP, Bonen A. In obese Zucker rats, lipids accumulate in the heart despite normal mitochondrial content, morphology and long-chain fatty acid oxidation. J Physiol 589: 169–180, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, Wilson PWF, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N Engl J Med 347: 305–313, 2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Deng S, Ibarra RA, Anderson VE, Brunengraber H, Zhang G-F. Multiple mass isotopomer tracing of acetyl-CoA metabolism in Langendorff-perfused rat hearts: channeling of acetyl-CoA from pyruvate dehydrogenase to carnitine acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem 290: 8121–8132, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.631549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Sadhukhan S, Berthiaume JM, Ibarra RA, Tang H, Deng S, Hamilton E, Nagy LE, Tochtrop GP, Zhang G-F. 4-Hydroxy-2(E)-nonenal (HNE) catabolism and formation of HNE adducts are modulated by β oxidation of fatty acids in the isolated rat heart. Free Radic Biol Med 58: 35–44, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Zhang S, Berthiaume JM, Simons B, Zhang G-F. Novel approach in LC-MS/MS using MRM to generate a full profile of acyl-CoAs: discovery of acyl-dephospho-CoAs. J Lipid Res 55: 592–602, 2014. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D045112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li T, Zhang Z, Kolwicz SC Jr, Abell L, Roe ND, Kim M, Zhou B, Cao Y, Ritterhoff J, Gu H, Raftery D, Sun H, Tian R. Defective branched-chain amino acid catabolism disrupts glucose metabolism and sensitizes the heart to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Metab 25: 374–385, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGarrah RW, Crown SB, Zhang G-F, Shah SH, Newgard CB. Cardiovascular metabolomics. Circ Res 122: 1238–1258, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGarry JD, Leatherman GF, Foster DW. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I. The site of inhibition of hepatic fatty acid oxidation by malonyl-CoA. J Biol Chem 253: 4128–4136, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newgard CB. Interplay between lipids and branched-chain amino acids in development of insulin resistance. Cell Metab 15: 606–614, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newgard CB. Metabolomics and metabolic diseases: where do we stand? Cell Metab 25: 43–56, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Lien LF, Haqq AM, Shah SH, Arlotto M, Slentz CA, Rochon J, Gallup D, Ilkayeva O, Wenner BR, Yancy WS Jr, Eisenson H, Musante G, Surwit RS, Millington DS, Butler MD, Svetkey LP. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab 9: 311–326, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulze PC, Drosatos K, Goldberg IJ. Lipid use and misuse by the heart. Circ Res 118: 1736–1751, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.She P, Van Horn C, Reid T, Hutson SM, Cooney RN, Lynch CJ. Obesity-related elevations in plasma leucine are associated with alterations in enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1552–E1563, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00134.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Christopher BA, Wilson KA, Muoio D, McGarrah RW, Brunengraber H, Zhang GF. Propionate-induced changes in cardiac metabolism, notably CoA trapping, are not altered by l-carnitine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 315: E622–E633, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00081.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White PJ, Lapworth AL, An J, Wang L, McGarrah RW, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva O, George T, Muehlbauer MJ, Bain JR, Trimmer JK, Brosnan MJ, Rolph TP, Newgard CB. Branched-chain amino acid restriction in Zucker-fatty rats improves muscle insulin sensitivity by enhancing efficiency of fatty acid oxidation and acyl-glycine export. Mol Metab 5: 538–551, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White PJ, McGarrah RW, Grimsrud PA, Tso SC, Yang WH, Haldeman JM, Grenier-Larouche T, An J, Lapworth AL, Astapova I, Hannou SA, George T, Arlotto M, Olson LB, Lai M, Zhang G-F, Ilkayeva O, Herman MA, Wynn RM, Chuang DT, Newgard CB. The BCKDH kinase and phosphatase integrate BCAA and lipid metabolism via regulation of ATP-citrate lyase. Cell Metab 27: 1281–1293.e7, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White PJ, Newgard CB. Branched-chain amino acids in disease. Science 363: 582–583, 2019. doi: 10.1126/science.aav0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young ME, Guthrie PH, Razeghi P, Leighton B, Abbasi S, Patil S, Youker KA, Taegtmeyer H. Impaired long-chain fatty acid oxidation and contractile dysfunction in the obese Zucker rat heart. Diabetes 51: 2587–2595, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]