Abstract

We studied the mechanisms by which carotid body glomus (type 1) cells produce spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia and hypoxia. In cells perfused with normoxic solution at 37°C, we observed relatively uniform, low-frequency Ca2+ oscillations in >60% of cells, with each cell showing its own intrinsic frequency and amplitude. The mean frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations were 0.6 ± 0.1 Hz and 180 ± 42 nM, respectively. The duration of each Ca2+ oscillation ranged from 14 to 26 s (mean of ∼20 s). Inhibition of inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor and store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) using 2-APB abolished Ca2+ oscillations. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) using thapsigargin abolished Ca2+ oscillations. ML-9, an inhibitor of STIM1 translocation, also strongly reduced Ca2+ oscillations. Inhibitors of L- and T-type Ca2+ channels (Cav; verapamil>nifedipine>TTA-P2) markedly reduced the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Thus, Ca2+ oscillations observed in normoxia were caused by cyclical Ca2+ fluxes at the ER, which was supported by Ca2+ influx via Ca2+ channels. Hypoxia (2–5% O2) increased the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations, and Cav inhibitors (verapamil>nifedipine>>TTA-P2) reduced these effects of hypoxia. Our study shows that Ca2+ oscillations represent the basic Ca2+ signaling mechanism in normoxia and hypoxia in CB glomus cells.

Keywords: Ca2+ channel, Ca2+ oscillations, carotid body type 1 cells, frequency, mild hypoxia

INTRODUCTION

Carotid body (CB) glomus cells are peripheral chemoreceptors that convert the arterial O2 pressure signal to changes in cell membrane potential (Em) that regulate the activity of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (Cav) and [Ca2+]i. The rise in [Ca2+]i is critical for increasing the glomus cell secretory activity, and therefore, changes in [Ca2+]i have been measured to indirectly assess the activity of glomus cells. Studies in isolated glomus cells have shown that the rise in mean [Ca2+]i produced by graded levels of hypoxia follows a hyperbolic function (11, 34, 43). The averaged [Ca2+]i response is very low at mild/moderate levels of hypoxia (Po2 of perfusion solution; 35–100 mmHg), but increases steeply at severe levels of hypoxia (Po2 < 30 mmHg) (8, 10, 31, 35, 47). Respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, and sleep apnea produce mild and moderate levels of hypoxia, where arterial Po2 is reduced from a normal level of ∼100 mmHg to 72–78 mmHg (16, 22). Thus, it is important to understand how mild and moderate levels of hypoxia regulate the Ca2+ signaling processes in glomus cells.

In many cell types, agonists elevate [Ca2+]i as a part of the signal transduction pathway to regulate cell function. In such cells, high agonist concentrations elicit a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i, whereas low agonist concentrations elicit oscillations in [Ca2+]i (26, 40). For example, a low-level stimulus increases the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations to regulate the cellular activity in various cell types such as pancreatic β-cells, adrenal cells, pituitary gonadotrophs, and airway smooth muscle cells (6, 17, 24, 26). Such Ca2+ oscillations are considered to be important for low-level signaling, for preventing desensitization, and for providing efficacy and specificity of information flow. In glomus cells, few and random fluctuations in averaged [Ca2+]i have been observed in earlier studies (8, 33). Whether such fluctuations in [Ca2+]i represent low-level Ca2+ oscillations and how they arise are not known. Search of the literature indicated no published studies on Ca2+ oscillations in glomus cells. In our attempts to better understand the nature of spontaneous Ca2+ fluctuations in glomus cells, we found that a large fraction of glomus cells generated relatively uniform low-frequency Ca2+ fluctuations, suggesting that Ca2+ signaling in glomus cells may also involve Ca2+ oscillations, similar to those in other cell types.

In the present study, we characterized the kinetics of Ca2+ oscillations and investigated the roles of Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in the generation of Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia. We studied the effects of different experimental conditions such as flow rate and perfusion temperature on the kinetics of Ca2+ oscillations. We then studied the effects of mild and moderate levels of hypoxia on the kinetics of Ca2+ oscillations and the role of Ca2+ channels in this process. Our results showed that low-frequency Ca2+ oscillations that occur in glomus cells in normoxia involve Ca2+ fluxes both at the ER and plasma membrane. Mild and moderate levels of hypoxia augmented the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations by increasing Ca2+ influx via Cav. These findings show that Ca2+ oscillations most likely represent the physiological Ca2+ signaling processes that underlie glomus cell activity in normoxia as well as under mild and moderate levels of hypoxia. Some of the preliminary findings were presented at the Experimental Biology meeting (28).

METHODS

Animals and ethical approval.

All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines set by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Rosalind Franklin University under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol no. 18‐02, and conform to the principles and regulations as described by Grundy (20). The animal care and use program is Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care‐accredited and approved by the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (A3279‐01). There are no ethical concerns. Rats (Sprague-Dawley, postnatal days 16–24) purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN) were acclimatized in house for at least ∼1 wk. Standard laboratory diet (Teklad Global 19% Protein Extruded Rodent Diet, Harlan no. 2019S) and drinking water were provided.

Cell isolation.

Rats (male and female) were deeply anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane until cessation of breathing and decapitated with a sharp razor blade. Six to eight CBs from the region of the carotid artery bifurcation were removed from three to four rats and placed in ice-cold, low-Ca2+, low-Mg2+ phosphate-buffered saline (low-Ca2+/Mg2+ PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 2 mM KH2PO4, 0.07 mM CaCl2, and 0.05 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4). Each CB was cut into three to four pieces and placed in a solution containing trypsin (0.4 mg/mL) and collagenase (0.4 mg/mL) in low-Ca2+/Mg2+ PBS and incubated at 37°C for 25 min. Following trituration using a fire-polished glass pipette, the dispersed cells were separated by centrifugation at low speed (1,200 g for 5 min) and suspended in CB growth medium. CB growth medium contained Ham’s F-12, 10% fetal bovine serum, 23 mM glucose, 4 mM Glutamax-I (l-alanyl glutamine), 10 kU penicillin, 10 kU streptomycin, and 300 μg/mL insulin. Cells were plated on to poly-d-lysine-pretreated glass coverslips and incubated at 37°C for ∼3 h in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air-5% CO2. Cells were used the same day within 6 h after plating.

[Ca2+] measurement.

Isolated cells plated on glass coverslips were incubated with 2 μM fura-2 AM for 30 min at 37°C in culture medium. A coverslip with attached cells was placed in a recording chamber positioned on the stage of an inverted microscope (IX71; Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA). Fura-2 was alternately excited at 340 and 380 nm, and the emitted fluorescence was filtered at 510 nm and recorded using a charge-coupled device (CCD)-based imaging system running SimplePCI software (Hamamatsu Corp.). The cells in the recording chamber were continuously perfused with a solution containing (in mM) 117 NaCl, 5 KCl, 23 NaHCO3, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2 and 11 glucose (pH 7.3). Ratiometric data were calibrated by applying experimentally determined constants to the following equation: [Ca2+] = Kd × β × (R – Rmin)/(Rmax – R) (21). Values for Rmax (12.0), Rmin (0.1), and β (11.6) were determined in vitro, and a Kd value of 300 nM for fura-2 was assumed. Each experiment was performed using coverslips of cells prepared on different days, and no more than two coverslips were used for each day.

Hypoxia studies.

In our experiments that used a recording chamber that was open to the atmosphere, we generated different levels of hypoxic solutions (ranging from approximately mild hypoxia to anoxia) by bubbling solutions with 5%CO2-95%N2 with 2 U/mL of glucose oxidase and 100 U/mL of catalase added to the solution (anoxia; see Refs. 5 and 29), 5% CO2-1% O2-94% N2 (severe hypoxia), 5% CO2-2% O2-93% N2 (moderate hypoxia), 5%CO2-5%O2-90%N2 (mild hypoxia), or 5%CO2-10%O2-85%N2. A reproducible level of [O2] in the perfusion chamber was produced for each level of hypoxia, as judged by %O2 measurements using an O2 meter (ISO2; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). After a steady-state basal [Ca2+]i was obtained with normoxic solution, the perfusion solution was switched to a desired hypoxic solution. The temperature of the perfusion solutions was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.3°C. In three trials, the mean O2 levels in solutions in the recording chamber were 0.4% (3 mmHg) for anoxia, 1.6% (12 mmHg) for severe hypoxia, 2.3% (17 mmHg) for moderate hypoxia, and 5.2% (40 mmHg) for mild hypoxia. The O2 meter was calibrated to 0% with solution bubbled with pure nitrogen for 60 min and to 21% with solution gassed with air for 30 min at 37°C.

Materials and data analysis.

2-APB, thapsigargin and ML-9 [1-(5-chloronaphthalenesulfonyl)-homopiperazine HCl] were from Tocris. Fura-2 AM was from Thermofisher Scientific. Catalase and glucose oxidase were from Sigma-Aldrich Co. All other chemicals for preparing perfusion solutions were from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Student’s t-test (for comparison of 2 sets of data) and one-way analysis of variance (comparison of 3 or more sets of data) were used for data analysis using PRISM software. Post hoc testing following analysis of variance was based on unpaired t-test with Bonferroni correction. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as box plots when the total number of cells analyzed is large (n > 40). For other plots, means ± SD are shown. Box plots show four quartile groups (25% each) and median and mean (solid circle) values.

RESULTS

Spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia.

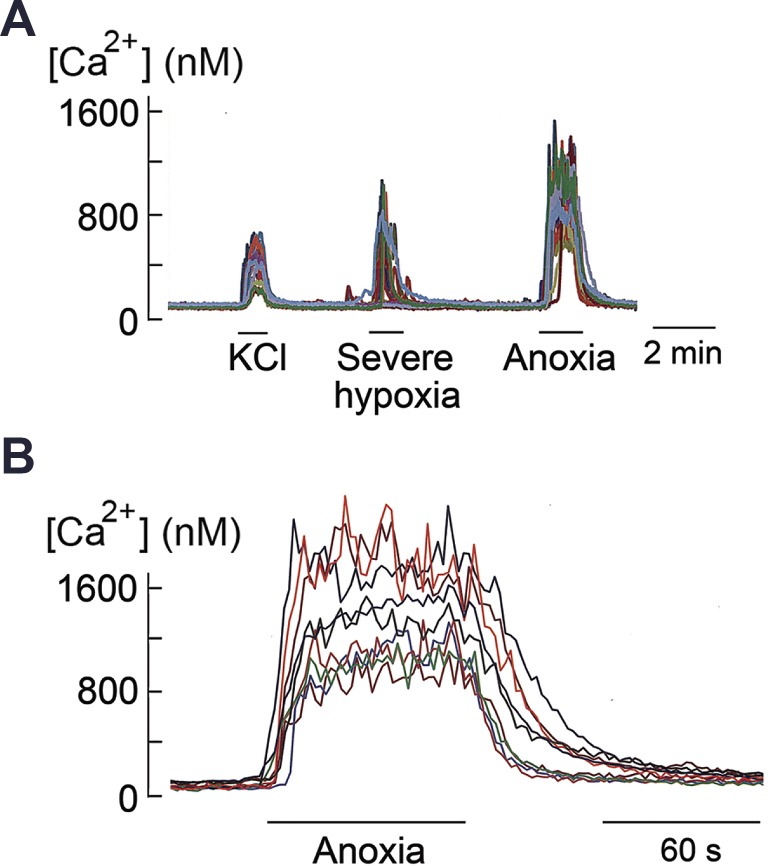

In the first set of experiments, cells were perfused at 30°C, rather than at 37°C, to minimize the appearance of spontaneous Ca2+ fluctuations from the basal state so that [Ca2+]i responses produced by high KCl and hypoxia could be identified clearly. In all six coverslips of cells tested, cells whose [Ca2+]i increased in response to 20 mM KCl were also sensitive to severe hypoxia and anoxia (Fig. 1A). Expanded tracings of the sustained increase in [Ca2+]i by anoxia are shown in Fig. 1B. Cells that did not respond to 20 mM KCl were insensitive to hypoxia and anoxia. Therefore, 20 mM KCl was used to identify hypoxia-sensitive type 1 (glomus) cells throughout the study.

Fig. 1.

Sustained increase in intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) produced by high KCl and anoxia in isolated glomus cells. A: [Ca2+]i responses to 20 mM KCl, severe hypoxia, and anoxia. Perfusion temperature is 30°C. B: [Ca2+]i response to anoxia at an expanded scale.

In isolated cells perfused with normoxic solution at a flow rate of 2 mL/min (velocity of ∼20 cm/min; see below) at 37°C, we observed variable levels of fluctuations in [Ca2+]i in many cells. Fluctuations in basal [Ca2+]i have been observed previously, but the signals were generally averaged, and thus their kinetic properties in individual cells remain poorly defined.

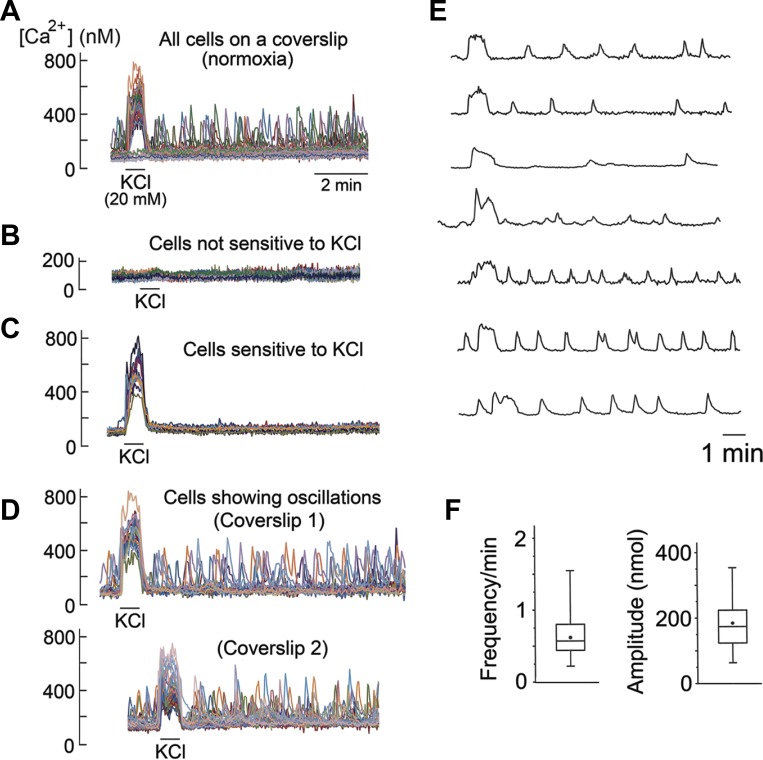

The kinetics of such fluctuations in basal [Ca2+]i in individual cells were examined in detail. A representative recording from a coverslip of cells is shown in Fig. 2A (top tracing). The cell population could be divided into three types based on their response to KCl and appearance of Ca2+ fluctuations (Fig. 2, B–D). Cells that were not sensitive to 20 mM KCl did not show spontaneous Ca2+ fluctuations and were assumed to be mostly type II cells (Fig. 2B). In cells that responded to KCl, some cells showed no Ca2+ fluctuations (Fig. 2C), while others showed varying degrees of Ca2+ fluctuations in both frequency and amplitude. Ca2+ recordings in KCl-sensitive cells from two coverslips of cells are shown in Fig. 2D. Ca2+ fluctuations were present before application of 20 mM KCl, indicating that high KCl itself was not the trigger for the generation of Ca2+ oscillations.

Fig. 2.

Spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia. A: all cells on a coverslip in normoxic solution containing 5 mM KCl (n = 34 cells). KCl (20 mM) is applied briefly at the beginning. B: cells that are insensitive to 20 mM KCl. C: cells that are sensitive to 20 mM KCl but without Ca2+ oscillations. D: cells that are sensitive to 20 mM KCl and show Ca2+ oscillations. Recordings are from two coverslips of cells. E: Ca2+ oscillations from individual cells from different coverslips at expanded scale. F: frequency and amplitude levels (8 coverslips; n = 160 cells).

The percentage of cells in each coverslip showing clearly identifiable Ca2+ fluctuations (>50 nM above the resting level) ranged from ∼30 to ∼85% (average of ∼65%; 32 coverslips of cells). Figure 2E shows examples of Ca2+ fluctuations in individual cells, illustrating the varying levels of frequency and amplitude. Each cell generated its own Ca2+ fluctuations with intrinsic frequency and amplitude that were generally uniform and sustained during the perfusion. Therefore, we will refer to such Ca2+ fluctuations as Ca2+ oscillations from hereon.

Figure 2F plots the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations from individual cells from eight coverslips of cells (n = 160 cells). In cells showing Ca2+ oscillations, mean frequency and amplitude were 0.6 ± 0.1 min and 180 ± 42 nM (above the baseline of ∼100 nM), respectively. If all KCl-responding cells, including those that show no clearly identifiable Ca2+ oscillations, are taken into account, the mean frequency and amplitude levels would be significantly lower and depend on the coverslip of cells used for each experiment. Under our experimental conditions, the average duration of Ca2+ oscillations was ∼20 s (range 14–26 s; n = 16). These findings show that low-frequency Ca2+ oscillations are spontaneously generated in a substantial population of isolated glomus cells perfused at 37°C with a normoxic solution.

Temperature and flow rate effects on Ca2+ oscillations.

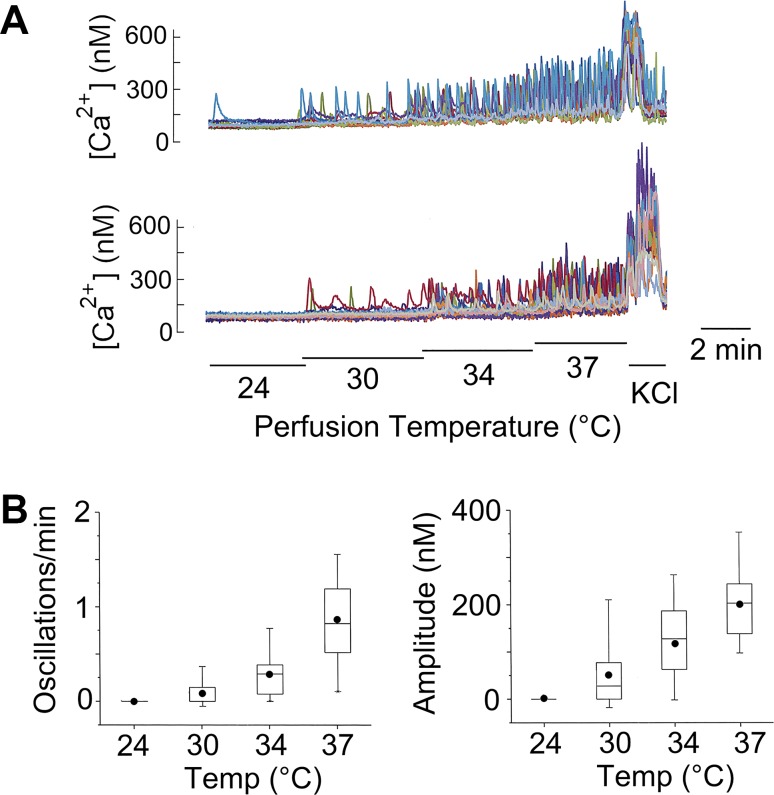

We observed a strong temperature dependence of Ca2+ oscillations in glomus cells, as illustrated in two coverslips of cells (Fig. 3A). At 24°C, Ca2+ oscillations were generally absent. As the temperature of the perfusion solution was increased to 30°C, a few cells started to show oscillations. The number of cells showing Ca2+ oscillations continued to increase as the perfusion temperature was elevated to 34°C and 37°C. Both the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations were increased by heat (Fig. 3B). In the studies of Ca2+ oscillations described below, the perfusion temperature in the recording chamber was maintained at 37°C.

Fig. 3.

Perfusion temperature and Ca2+ oscillations. A: intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) recording in KCl-sensitive cells at different bath temperatures. B: frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations at four temperatures (4 coverslips of cells; n = 88) are all significantly different from each other (P < 0.01).

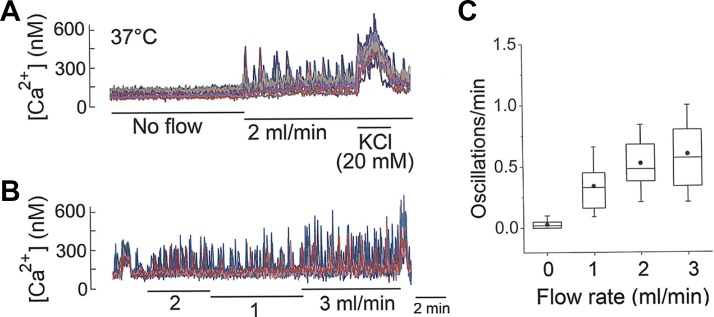

We also observed a significant effect of flow rate of the perfusion solution on the kinetics of Ca2+ oscillations. With the temperature of the standing solution maintained at ∼37°C using a heated recording chamber and zero flow, no Ca2+ oscillations were observed (Fig. 4A). Upon changing the perfusion to a rate of ∼2 ml/min while maintaining the temperature at 37°C, Ca2+ oscillations were quickly elicited in many cells. The estimated velocity of perfusion solution was ∼20 cm/min, a value calculated based on the cross-sectional area (2 mm deep × 5 mm wide) of ∼10 mm2 for solution moving through the recording chamber. When the flow rate was switched from 1 to 3 mL/min, a rate-dependent increase in the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations was clearly present (Fig. 4B). Flow-dependent increase in oscillation frequency is shown in Fig. 4C. These findings show that the perfusion flow rate regulates the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations and suggest the possibility that a mechanism that senses mechanical force may be present in glomus cells. A perfusion flow rate of 2 mL/min was used for studies described below, unless indicated otherwise.

Fig. 4.

Flow rate and Ca2+ oscillations. A: intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in KCl-sensitive cells on a coverslip at flow rates of 0 and 2 mL/min. Bath temperature is kept at 37°C. B: [Ca2+]i in KCl-sensitive cells on a coverslip at flow rate of 1–3 mL/min. C: frequency of Ca2+ oscillations at 4 different flow rates (4 coverslips of cells; n = 53). All values were significantly different from each other (P < 0.01), except those between 2 and 3 mL/min (P > 0.05).

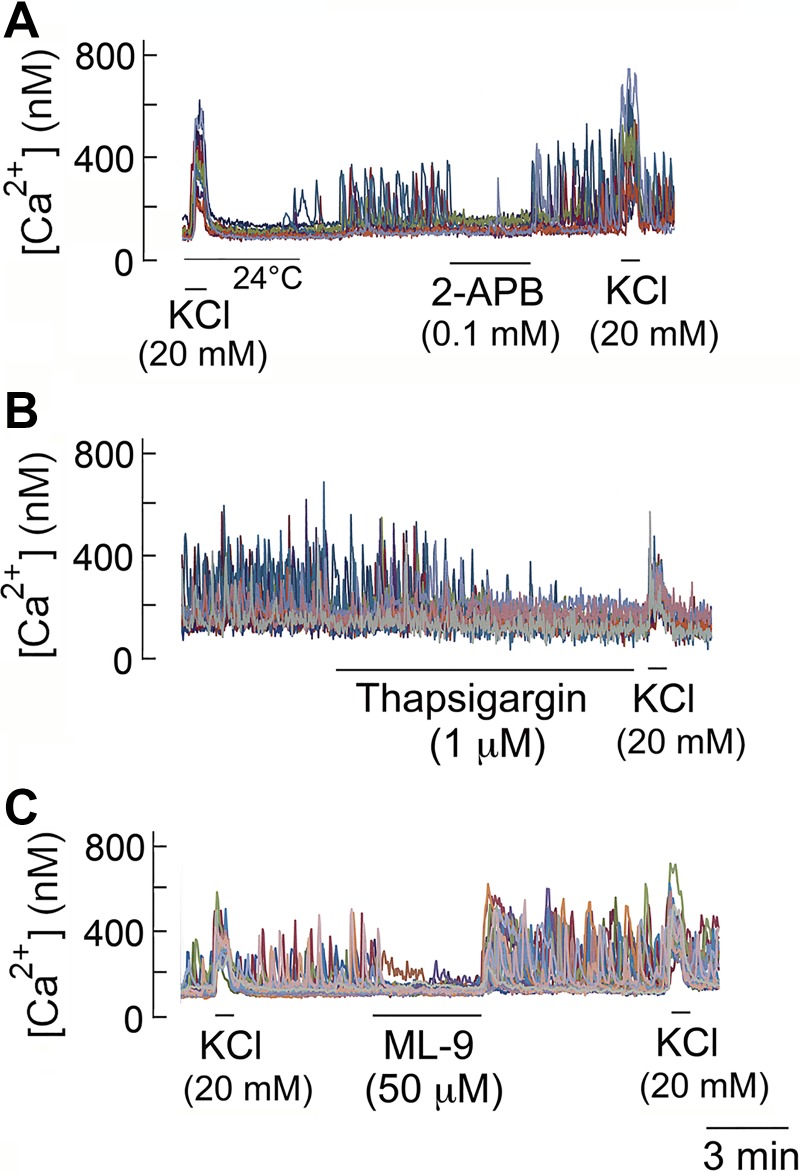

Inhibition of ER inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor and store-operated Ca2+ entry on Ca2+ oscillations.

Ca2+ oscillation is known to occur as a result of Ca2+ release from and uptake by ER, which is modulated by other Ca2+ signals such as Ca2+ influx via Cav and store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) (17). To determine the mechanism of Ca2+ oscillations in glomus cells, we first tested the effect of 2-APB that inhibits inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated Ca2+ release from ER and SOCE. Cells were perfused with normoxic solution at 37°C until a steady-state level of Ca2+ oscillations was achieved. In all five coverslips (n = 73 cells), switching to a solution that contained 100 μM 2-APB caused an immediate cessation of Ca2+ oscillations that fully recovered following washout of the drug (Fig. 5A), indicating that Ca2+ signaling by ER/SOCE is critical for the generation of Ca2+ oscillations.

Fig. 5.

Effects of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), thapsigargin, and ML-9 on Ca2+ oscillations. A: reversible inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations by 2-APB. B: slow and irreversible inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations by thapsigargin. C: reversible inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations by ML-9.

Thapsigargin (1 μM), an irreversible inhibitor of ER Ca2+-ATPase, produced a gradual and complete inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations in all four coverslips (n = 63 cells; Fig. 5B). Application of ML-9 (50 μM), an agent that interferes with STIM1 translocation and thereby inhibits SOCE (41), produced a reversible block of Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia in all four coverslips (n = 66 cells; Fig. 5C). Therefore, these findings indicate that Ca2+ oscillations in glomus cells are mediated by ER/SOCE-dependent mechanisms, similar to those found in other secretory cells.

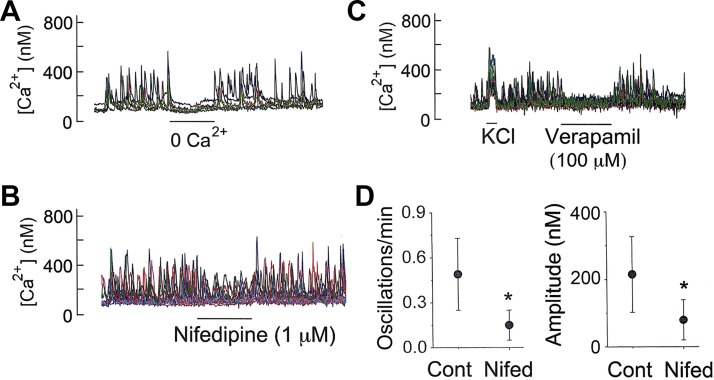

Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia.

In many cell types that exhibit Ca2+ oscillations, Ca2+ influx via the plasma membrane regulates the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations by altering “the Ca2+ load” in the cell (42). In glomus cells showing Ca2+ oscillations, lowering [Ca2+]o from 1 to ∼0 mM quickly abolished Ca2+ oscillations in all cells and the addition of 1 mM Ca2+ restored Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 6A), indicating that Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane is necessary to sustain the basal level of Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia. Nifedipine (1 μM) that blocks the L-type Cav produced a strong reversible inhibition of both frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 6B). Verapamil (100 μM), a nonspecific Cav inhibitor, reversibly abolished Ca2+ oscillations, supporting the critical role of Ca2+ influx via Cav in supporting Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 6C). A summary of the effects of nifedipine on the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations is shown in Fig. 6D.

Fig. 6.

Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ oscillations. A: removal of external Ca2+ on intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) oscillations. B: nifedipine effect on Ca2+ oscillations. C: cessation of Ca2+ oscillations by verapamil (3 coverslips; n = 43 cells). D: nifedipine effects on frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations (means ± SD; 6 coverslips of cells). *Significantly different (P < 0.01).

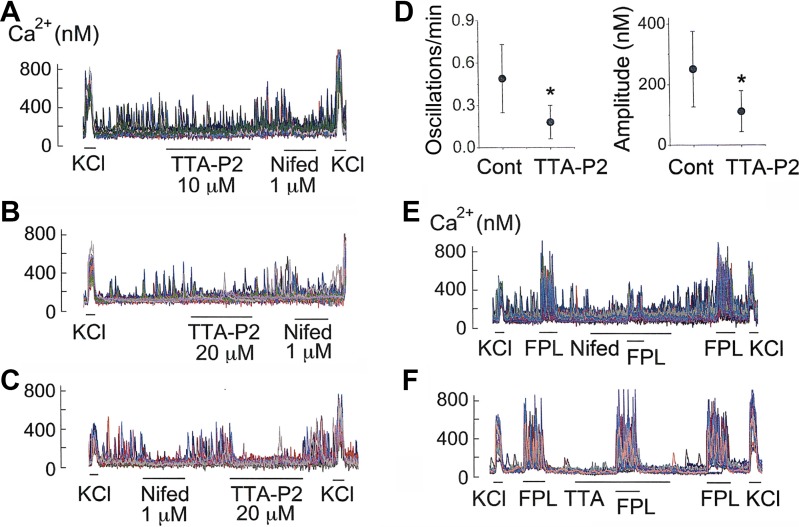

Interestingly, TTA-P2 (a T-type Cav inhibitor; see Ref. 14) also caused a significant inhibition of the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 7, A and B). The inhibitory effect of TTA-P2 on Ca2+ oscillations was as strong as that of nifedipine (Fig. 7, C and D). To be sure that the inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations by TTA-P2 was not due to block of the L-type Cav, we tested the effect of TTA-P2 on FPL-64176-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. FPL-64176 is a potent activator of the L-type Cav and elicits a strong, nifedipine-sensitive increase in [Ca2+]i (27). As predicted, nifedipine produced a 92 ± 5% inhibition of FPL-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (3 coverslips; n = 48 cells; Fig. 7E). However, TTA-P2 produced no significant effect in any of the three coverslips (n = 52 cells), showing that TTA-P2 (20 μM) did not block the L-type Cav (Fig. 7F). ML-218, another T-type Cav inhibitor, also reduced the frequency of basal Ca2+ oscillations by 62 ± 6% (n = 5 coverslips; 78 cells). These results indicate that Ca2+ influx via both L- and T-type Cav occurs in resting isolated glomus cells and is important for the generation of basal Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia.

Fig. 7.

T-type Cav inhibitors and Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia. A: effects of TTA-P2 (10 μM) and nifedipine (1 μM) on Ca2+ oscillations. B: effects of TTA-P2 (20 μM) and nifedipine (1 μM). C: effects of nifedipine (1 μM) and TTA-P2 (20 μM). D: TTA-P2 effects on frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations (means ± SD; 6 coverslips of cells). *Significantly different (P < 0.01). E: nifedipine block of L-type Cav activated by FPL64176. F: lack of effect of TTA-P2 on L-type Cav activated by FPL64176. CaV, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel.

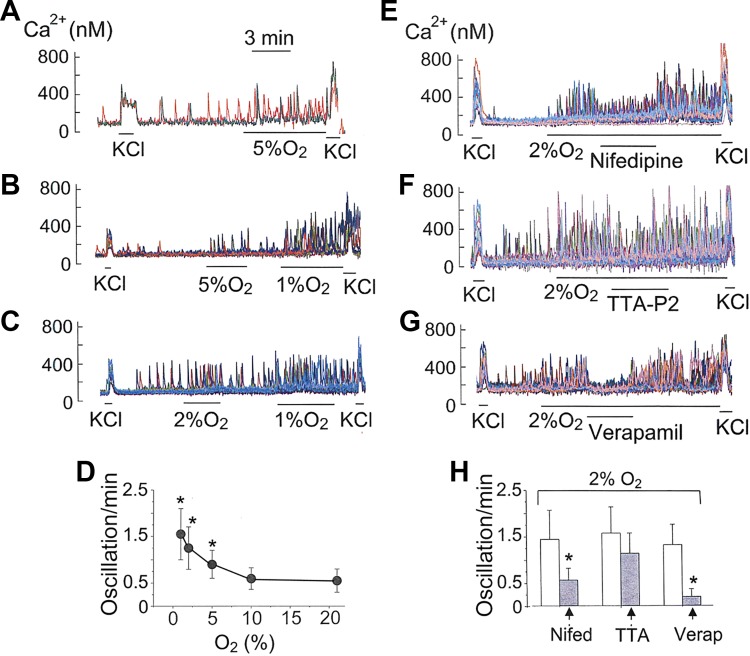

Mild/moderate hypoxia and Ca2+ oscillations.

Mild and moderate levels of hypoxia (2–5% O2) generally produce a very small increase in basal [Ca2+]i when Ca2+ signals from multiple cells are averaged (11, 34, 47). We tested the possibility that mild and moderate levels of hypoxia modulate Ca2+ signaling by regulating Ca2+ oscillations in individual glomus cells. Cells were perfused with normoxic solution at 37°C and then perfused with solution containing 2% or 5% O2. Both levels of hypoxia increased the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations without causing a sustained elevation of basal [Ca2+]i (Fig. 8, A and B). We used 21% O2 for normoxia, although this level of O2 is higher than that found inside the CB. In the CB microvasculature, Po2 measured using different techniques ranges from ∼20 to ∼60 mmHg (4, 13, 30, 48). The frequency of Ca2+ oscillations at 10% O2 was not significantly different from those observed at 21% O2 (P > 0.20, 4 coverslips, 68 cells; Fig. 8D). In support of this finding, earlier studies have found very little or no effect of 50–60 mmHg Po2 on averaged [Ca2+]i (11, 43, 46).

Fig. 8.

Hypoxia and Ca2+ oscillations. A–C: Ca2+ oscillations in response to hypoxia (1–5% O2). D: plot of frequency as a function of %O2 (4–6 coverslips for each level of O2). *Significantly different from that at 21% O2 (P < 0.01). E–G: inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations by 1 μM nifedipine, 20 μM TTA-P2, and 100 μM verapamil under hypoxic conditions. H: frequency effects of nifedipine (5 coverslips; n = 72), TTA-P2 (5 coverslips; n = 66), and verapamil (3 coverslips; n = 48). *Significantly different from control (P < 0.01).

In cells that were quiescent in normoxia, hypoxia (2 or 5% O2) elicited Ca2+ oscillations, and the number of cells responsive to hypoxia on a coverslip increased progressively as the severity of hypoxia was increased from 5% to 1% O2. At 1% O2, some cells responded with an increase in Ca2+ oscillations, whereas others showed sustained elevation of basal [Ca2+]i. These findings show a wide range in glomus cell sensitivity to hypoxia. When only those cells that showed Ca2+ oscillations were analyzed and plotted, it was clear that mild and moderate levels of hypoxia produced a significant increase the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 8D). Such a phenomenon is difficult to detect when [Ca2+]i signals are averaged from multiple cells, as done in earlier studies.

Nifedipine markedly reduced the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations augmented by hypoxia (2%O2; Fig. 8, E and H), indicating that hypoxia enhanced Ca2+ influx via the L-type Cav. However, TTA-P2 (20 μM) produced only a transient inhibition and failed to produce a significant effect overall, suggesting that hypoxia perhaps activated the T-type Cav only transiently at the beginning, which is not enough to keep the inhibition sustained (Fig. 8, F and H). ML-218 (20 μM) also failed to produce a significant inhibition of Ca2+ oscillations under hypoxia (2%O2) in three coverslips of cells. Verapamil, an inhibitor of all isoforms of Cav, abolished Ca2+ oscillations under hypoxia (2%O2), showing that Ca2+ influx is critical for hypoxia (2%O2)-induced increase in Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 8G). These findings indicate that the L-type Cav plays a major role in hypoxia (2% O2)-induced increase in Ca2+ oscillations. Under hypoxic conditions (2%O2), the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations was also strongly reduced by 2-APB (100 μM, 92 ± 6% inhibition, 4 coverslips) and ML-9 (50 μM, 76 ± 9% inhibition, 2 coverslips; n = 48 cells), showing that SOCE/ER play a critical role in the generation of Ca2+ oscillations in hypoxia.

DISCUSSION

Slow and random fluctuations in mean [Ca2+]i have been observed in glomus cells previously, but it is not known whether they represent true Ca2+ oscillations. Our study shows for the first time that a large percentage of isolated glomus cells are able to generate spontaneous, relatively uniform Ca2+ oscillations at a relatively low frequency in normoxia. Our data show that these Ca2+ oscillations are produced by Ca2+ release/uptake processes at the ER membrane and are sustained by Ca2+ influx via the Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane. Thus, the mechanisms of Ca2+ oscillations in glomus cells are similar to those found in other secretory and contracting cells such as pancreatic β-cells, adrenal cells, and airway smooth muscle cells (7, 15, 17, 18, 24). We also show that mild and moderate levels of hypoxia increase the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations, as opposed to a sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i produced by severe levels of hypoxia. Thus, Ca2+ oscillations represent the basic Ca2+ signaling mechanism in glomus cells. Thus, mild and moderate levels of hypoxia augment glomus cell activity most likely by altering the kinetics of Ca2+ release/uptake by the ER to regulate Ca2+ oscillations.

Because the elevation of [Ca2+]i is critical for the secretory activity of glomus cells (34, 36, 44), one could speculate that Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia are probably important for basal transmitter secretion that occurs in normoxia and that the increased frequency of Ca2+ oscillations produced by mild levels of hypoxia augments the secretory response rapidly without desensitization. Although we have not directly determined how changes in frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations affect the secretory activity of glomus cells, we speculate that a strong relationship exists between Ca2+ oscillations and transmitter secretion as in other cell types that exhibit Ca2+ oscillations.

General property of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in isolated glomus cells in normoxia.

Under our experimental conditions in which the cells are perfused with normoxic solution at a constant flow rate (∼2 ml/min) and temperature (37°C), spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations occurred in ∼65% of glomus cells, with varying frequency among individual cells (0–3 Hz). The frequency of Ca2+ oscillations was highly dependent on perfusion temperature, with almost no oscillations present at 24° and prominent oscillations at 37°C. This heat dependence of oscillation frequency is not surprising and has been observed in other types of cells (23, 25).

The frequency of Ca2+ oscillations was also dependent on flow rate within the perfusion chamber. Interestingly, no Ca2+ oscillations were observed at zero-flow rate even at 37°C, suggesting that mechanical perturbation could be affecting Ca2+ signaling mechanisms in glomus cells. Because glomus cells are not in direct contact with the flowing blood in the CB in vivo, we suspect that a pressure-sensing mechanism such as that present in baroreceptors could exist in glomus cells. Abudara and Eyzaguirre (3) first described a mechanical sensitivity of glomus cells. They reported that stirring the fluid bathing cultured rat glomus cells elicited Ca2+ spikes that were abolished in Ca2+-free external solution. Mechanical stimulation by touching the cells with the tip of the pipette also elicited Ca2+ spikes (3). These earlier findings and our recording of flow-sensitive Ca2+ oscillations support the notion that glomus cell activity may be regulated by pressure. The ability of glomus cells to sense pressure in an in vivo system will need further investigation but offers an interesting possibility of blood pressure regulation of CB activity. In this regard, hypertension-associated CB hyperactivity reported in a number of studies could involve pressure-induced changes in Ca2+ oscillations that in turn control glomus cell activity (1, 32, 37).

The frequency and amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations observed in individual glomus cells in normoxia were generally stable during ∼30 min of perfusion. Ca2+ oscillations were observed in both single isolated cells as well as in cells within clusters. Although cells in each cluster seemed to be attached to each other, Ca2+ oscillations frequently occurred independently such that the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in one cell was different from that of another within a cluster. The wide ranges of frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations in isolated glomus cells indicate that the basal excitability and Ca2+ signaling kinetics also vary widely among glomus cells. However, this could be an artifact caused by cell isolation, and Ca2+ oscillations in vivo could occur in a highly orchestrated process. It seems plausible that glomus cells within a lobule of the carotid body in vivo are connected by gap junctions and, therefore, fire at the same time. Future studies using ex vivo CB preparations should help identify the presence of Ca2+ oscillations as well as their kinetics in different regions of intact CB.

Role of Ca2+ channels in Ca2+ oscillations.

The finding that spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations do not occur in Ca2+-free external solution indicates that Ca2+ influx is necessary to keep the Ca2+ signaling machinery that generates Ca2+ oscillations working. Glomus cells express both T- and L-type Cav (11, 31, 38). Strong inhibition of basal Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia by inhibitors of L- (nifedipine, verapamil) and T-type Cav (TTA-P2, ML-218) shows that Ca2+ influx via both types of Cav occurs in normoxia and contributes critically to the Ca2+ oscillatory mechanism. Strong inhibition of hypoxia-induced increase in Ca2+ oscillations by nifedipine and a weak inhibition by TTA-P2 and ML-218 indicate that Ca2+ influx via the L-type Cav is the predominant pathway by which mild and moderate levels of hypoxia increase Ca2+ oscillations. Thus, Ca2+ influx via L- and T-type Cav can reduce the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in normoxia, but the L-type Cav inhibitor has a greater effect under hypoxic conditions.

It is known that the T-type Cav is activated by mild depolarization, involved in pacemaker role in neurons and cardiac cells, and critical for generating low-level spikes and oscillatory firing in many neurons (12, 19, 39). T-type Cav can also open near resting Em and regulate basal Ca2+ signaling (39, 49). Thus, the relative overall contributions of L- and T-type Cav to the generation of Ca2+ oscillations in glomus cells probably depend on the Em of the cell found under normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Mechanism of Ca2+ oscillations in glomus cells.

Based on our findings, we propose that basal Ca2+ influx via both L- and T-type Cav maintains a physiological level of cytosolic “Ca2+ load” that allows Ca2+ release and uptake by ER to occur at a low frequency in normoxia. SOCE exists in glomus cells (45), and thus its activity is expected to correlate with Ca2+ oscillations to help sustain the increase in Ca2+ oscillation frequency produced by hypoxia. When glomus cells depolarize in response to mild and moderate levels of hypoxia, the resulting increase in Ca2+ influx probably elevates the cytosolic “Ca2+ load,” thereby shifting the ER release/uptake process to a higher frequency state. Therefore, glomus cells possess Ca2+ signaling mechanisms that are similar to those described in other cell types. There is some evidence indicating that glomus cells can spontaneously depolarize and hyperpolarize (8). Such events would cause Cav to open and close in an oscillatory manner to help produce and sustain Ca2+ oscillations. Therefore, we suspect that oscillations in cell Em and [Ca2+]i are functionally linked, but this needs to be confirmed in the future.

Limitations of our study in isolated cells.

Although Ca2+ oscillations occur in glomus cells in isolated cells, the presence of such Ca2+ oscillations in vivo is not known. Although unlikely, enzymatic or mechanical dissociation could have caused Ca2+ oscillations following isolation. We were able to observe Ca2+ oscillations in a few CB slices, and therefore, we suspect that glomus cells in vivo can also generate Ca2+ oscillations, possibly with frequency and amplitude that are different from those in isolated cells. Electrical coupling of pairs of rat glomus cells in culture for 3–8 days has previously been demonstrated (2). In our studies, we used cells within 6 h after isolation, and electrical coupling may not be fully established between cells. In intact CB, Ca2+ oscillations may propagate from one cell to the next due to the presence of gap junctions, resulting in identical oscillation frequency within a lobule of the carotid body. The sensitivity of isolated glomus cells to hypoxia may be different from those in vivo due to the presence of various circulatory transmitters and hormones that regulate the excitability of the carotid body. At present, we also do not know the effect of changes in frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations on the secretory activity of glomus cells as well as on the firing of carotid sinus afferent nerve fibers. Future studies are clearly necessary to address these questions by identifying and studying Ca2+ oscillations and nerve fiber activity in perfused and pressurized ex vivo preparations, which should help better understand the biological relevance and importance of Ca2+ oscillations in CB function.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-111497 (to D. Kim) and HL-142906 (to C. White) and by a grant from Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.K. and C.W. conceived and designed research; D.K., J.O.H., and C.W. performed experiments; D.K., J.O.H., and C.W. analyzed data; D.K., J.O.H., and C.W. interpreted results of experiments; D.K. and J.O.H. prepared figures; D.K. drafted manuscript; D.K. and C.W. edited and revised manuscript; D.K., J.O.H., and C.W. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdala AP, McBryde FD, Marina N, Hendy EB, Engelman ZJ, Fudim M, Sobotka PA, Gourine AV, Paton JF. Hypertension is critically dependent on the carotid body input in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Physiol 590: 4269–4277, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.237800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abudara V, Eyzaguirre C. Electrical coupling between cultured glomus cells of the rat carotid body: observations with current and voltage clamping. Brain Res 664: 257–265, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91982-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abudara V, Eyzaguirre C. Mechanical sensitivity of carotid body glomus cells. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 161: 210–213, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acker H, Lübbers DW, Purves MJ. Local oxygen tension field in the glomus caroticum of the cat and its change at changing arterial PO 2. Pflugers Arch 329: 136–155, 1971. doi: 10.1007/BF00586988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann RP, Penketh PG, Seow HA, Shyam K, Sartorelli AC. Generation of oxygen deficiency in cell culture using a two-enzyme system to evaluate agents targeting hypoxic tumor cells. Radiat Res 170: 651–660, 2008. doi: 10.1667/RR1431.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergner A, Sanderson MJ. Acetylcholine-induced calcium signaling and contraction of airway smooth muscle cells in lung slices. J Gen Physiol 119: 187–198, 2002. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergner A, Sanderson MJ. ATP stimulates Ca2+ oscillations and contraction in airway smooth muscle cells of mouse lung slices. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L1271–L1279, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00139.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckler KJ. A novel oxygen-sensitive potassium current in rat carotid body type I cells. J Physiol 498: 649–662, 1997. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckler KJ, Turner PJ. Oxygen sensitivity of mitochondrial function in rat arterial chemoreceptor cells. J Physiol 591: 3549–3563, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.257741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effects of hypoxia on membrane potential and intracellular calcium in rat neonatal carotid body type I cells. J Physiol 476: 423–428, 1994. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cain SM, Snutch TP. T-type calcium channels in burst-firing, network synchrony, and epilepsy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1828: 1572–1578, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C. Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med 15: 1239–1253, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choe W, Messinger RB, Leach E, Eckle VS, Obradovic A, Salajegheh R, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. TTA-P2 is a potent and selective blocker of T-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons and a novel antinociceptive agent. Mol Pharmacol 80: 900–910, 2011. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.073205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Andrea P, Grohovaz F. [Ca2+]i oscillations in rat chromaffin cells: frequency and amplitude modulation by Ca2+ and InsP3. Cell Calcium 17: 367–374, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(95)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delclaux B, Orcel B, Housset B, Whitelaw WA, Derenne JP. Arterial blood gases in elderly persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Eur Respir J 7: 856–861, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupont G, Combettes L, Bird GS, Putney JW. Calcium oscillations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: 1–18, 2011. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fridlyand LE, Tamarina N, Philipson LH. Bursting and calcium oscillations in pancreatic beta-cells: specific pacemakers for specific mechanisms. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299: E517–E532, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00177.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray LS, Macdonald TL. The pharmacology and regulation of T type calcium channels: new opportunities for unique therapeutics for cancer. Cell Calcium 40: 115–120, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grundy D. Principles and standards for reporting animal experiments in The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology. J Physiol 593: 2547–2549, 2015. doi: 10.1113/JP270818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guardiola J, Yu J, Hasan N, Fletcher EC. Evening and morning blood gases in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 5: 489–493, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajjar RJ, Bonventre JV. Oscillations of intracellular calcium induced by vasopressin in individual fura-2-loaded mesangial cells. Frequency dependence on basal calcium concentration, agonist concentration, and temperature. J Biol Chem 266: 21589–21594, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellman B, Gylfe E, Bergsten P, Grapengiesser E, Lund PE, Berts A, Tengholm A, Pipeleers DG, Ling Z. Glucose induces oscillatory Ca2+ signalling and insulin release in human pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 37, Suppl 2: S11–S20, 1994. doi: 10.1007/BF00400821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirono M, Takamura K, Ito Y, Nakano Y, Chikaoka Y, Suzuki N, Yoshioka T. Role of Ca2+-ATPase in spontaneous oscillations of cytosolic free Ca2+ in GH3 rat pituitary cells. Cell Calcium 25: 125–135, 1999. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1998.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iida T, Stojilković SS, Izumi S, Catt KJ. Spontaneous and agonist-induced calcium oscillations in pituitary gonadotrophs. Mol Endocrinol 5: 949–958, 1991. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-7-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang D, Wang J, Hogan JO, Vennekens R, Freichel M, White C, Kim D. Increase in cytosolic Ca2+ produced by hypoxia and other depolarizing stimuli activates a non-selective cation channel in chemoreceptor cells of rat carotid body. J Physiol 592: 1975–1992, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.266957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim D, and Hogan H. Properties of Ca2+ oscillations in rat carotid body chemoreceptor cells (Abstract) FASEB J 32, 1 Suppl 601.2, 2018.29457550 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, Papreck JR, Kim I, Donnelly DF, Carroll JL. Changes in oxygen sensitivity of TASK in carotid body glomus cells during early postnatal development. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 177: 228–235, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lahiri S, Rumsey WL, Wilson DF, Iturriaga R. Contribution of in vivo microvascular Po2 in the cat carotid body chemotransduction. J Appl Physiol (1985) 75: 1035–1043, 1993. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.3.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makarenko VV, Peng YJ, Yuan G, Fox AP, Kumar GK, Nanduri J, Prabhakar NR. CaV3.2 T-type Ca2+ channels in H2S-mediated hypoxic response of the carotid body. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308: C146–C154, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00141.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBryde FD, Abdala AP, Hendy EB, Pijacka W, Marvar P, Moraes DJ, Sobotka PA, Paton JF. The carotid body as a putative therapeutic target for the treatment of neurogenic hypertension. Nat Commun 4: 2395, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molnár Z, Petheo GL, Fülöp C, Spät A. Effects of osmotic changes on the chemoreceptor cell of rat carotid body. J Physiol 546: 471–481, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montoro RJ, Ureña J, Fernández-Chacón R, Alvarez de Toledo G, López-Barneo J. Oxygen sensing by ion channels and chemotransduction in single glomus cells. J Gen Physiol 107: 133–143, 1996. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ortega-Sáenz P, Pardal R, Levitsky K, Villadiego J, Muñoz-Manchado AB, Durán R, Bonilla-Henao V, Arias-Mayenco I, Sobrino V, Ordóñez A, Oliver M, Toledo-Aral JJ, López-Barneo J. Cellular properties and chemosensory responses of the human carotid body. J Physiol 591: 6157–6173, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.263657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardal R, Ludewig U, Garcia-Hirschfeld J, Lopez-Barneo J. Secretory responses of intact glomus cells in thin slices of rat carotid body to hypoxia and tetraethylammonium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 2361–2366, 2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030522297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paton JF, Sobotka PA, Fudim M, Engelman ZJ, Hart EC, McBryde FD, Abdala AP, Marina N, Gourine AV, Lobo M, Patel N, Burchell A, Ratcliffe L, Nightingale A. The carotid body as a therapeutic target for the treatment of sympathetically mediated diseases. Hypertension 61: 5–13, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peers C, Carpenter E, Hatton CJ, Wyatt CN, Bee D. Ca2+ channel currents in type I carotid body cells of normoxic and chronically hypoxic neonatal rats. Brain Res 739: 251–257, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)00832-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev 83: 117–161, 2003. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putney JW, Bird GS. Cytoplasmic calcium oscillations and store-operated calcium influx. J Physiol 586: 3055–3059, 2008. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Bird GS, Putney JW Jr. Ca2+-store-dependent and -independent reversal of Stim1 localization and function. J Cell Sci 121: 762–772, 2008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sneyd J, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Yule DI, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Control of calcium oscillations by membrane fluxes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 1392–1396, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303472101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sterni LM, Bamford OS, Tomares SM, Montrose MH, Carroll JL. Developmental changes in intracellular Ca2+ response of carotid chemoreceptor cells to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 268: L801–L808, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.5.L801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ureña J, Fernández-Chacón R, Benot AR, Alvarez de Toledo GA, López-Barneo J. Hypoxia induces voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and quantal dopamine secretion in carotid body glomus cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 10208–10211, 1994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Hogan JO, Kim D. Voltage- and receptor-mediated activation of a non-selective cation channel in rat carotid body glomus cells. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 237: 13–21, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wasicko MJ, Breitwieser GE, Kim I, Carroll JL. Postnatal development of carotid body glomus cell response to hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 154: 356–371, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wasicko MJ, Sterni LM, Bamford OS, Montrose MH, Carroll JL. Resetting and postnatal maturation of oxygen chemosensitivity in rat carotid chemoreceptor cells. J Physiol 514: 493–503, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.493ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whalen WJ, Savoca J, Nair P. Oxygen tension measurements in carotid body of the cat. Am J Physiol 225: 986–991, 1973. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yunker AM, McEnery MW. Low-voltage-activated (“T-Type”) calcium channels in review. J Bioenerg Biomembr 35: 533–575, 2003. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000008024.77488.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]