Abstract

We previously showed that ARHGAP42 is a smooth muscle cell (SMC)-selective, RhoA-specific GTPase activating protein that regulates blood pressure and that a minor allele single nucleotide variation within a DNAse hypersensitive regulatory element in intron1 (Int1DHS) increased ARHGAP42 expression by promoting serum response factor binding. The goal of the current study was to identify additional transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms that control ARHGAP42 expression. Using deletion/mutation, gel shift, and chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments, we showed that recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region (RBPJ) and TEA domain family member 1 (TEAD1) binding to a conserved core region was required for full IntDHS transcriptional activity. Importantly, overexpression of the notch intracellular domain (NICD) or plating SMCs on recombinant jagged-1 increased IntDHS activity and endogenous ARHGAP42 expression while siRNA-mediated knockdown of TEAD1 inhibited ARHGAP42 mRNA levels. Re-chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that RBPJ and TEAD1 were bound to the Int1DHS enhancer at the same time, and coimmunoprecipitation assays indicated that these factors interacted physically. Our results also suggest TEAD1 and RBPJ bound cooperatively to the Int1DHS and that the presence of TEAD1 promoted the recruitment of NICD by RBPJ. Finally, we showed that ARHGAP42 expression was inhibited by micro-RNA 505 (miR505) which interacted with the ARHGAP42 3′-untranslated region (UTR) to facilitate its degradation and by AK124326, a long noncoding RNA that overlaps with the ARHGAP42 transcription start site on the opposite DNA strand. Since siRNA-mediated depletion of AK124326 was associated with increased H3K9 acetylation and RNA Pol-II binding at the ARHGAP42 gene, it is likely that AK124326 inhibits ARHGAP42 transcription.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY First, RBPJ and TEAD1 converge at an intronic enhancer to regulate ARHGAP42 expression in SMCs. Second, TEAD1 and RBPJ interact physically and bind cooperatively to the ARHGAP42 enhancer. Third, miR505 interacts with the ARHGAP42 3′-UTR to facilitate its degradation. Finally, LncRNA, AK124326, inhibits ARHGAP42 transcription.

Keywords: ARHGAP42/GRAF3, SRF, RBPJ, RhoA, smooth muscle, TEAD

INTRODUCTION

Although hypertension is a major cardiovascular risk factor, the complex nature of blood pressure regulation has made it difficult to identify the mechanisms that influence its development (6, 34). Since blood pressure is directly proportional to systemic arteriolar resistance, vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) play a major role in its regulation. Inward vascular remodeling, a processed mediated by alterations in vascular SMC growth and vessel matrix composition, has long been associated with hypertension, and the increase in vessel stiffness that accompanies this process has been shown to contribute to end-organ damage (19, 29, 37). More recent studies indicate that the intrinsic mechanical properties of vascular SMCs also play a role in the development of hypertension (40). Force generation in SMCs is directly proportional to myosin light chain phosphorylation, and Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent activation of myosin light chain kinase and nitrous oxide-dependent activation of myosin light chain phosphatase are major regulators of SMC contractility (35). Signaling through the small GTPase, RhoA, potentiates calcium-induced SMC contractility by a mechanism that involves direct phosphorylation of myosin light chain by the RhoA effector, Rho-kinase (ROCK) as well as ROCK-dependent inhibition of myosin phosphatase (41). Many contractile agonists that signal through G protein-coupled receptors, i.e., angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and norepinephrine, have been shown to stimulate RhoA in SMCs, and many do so by activating the regulator of G protein signaling family of Rho-specific GTPase exchange factors (1). Several components of the RhoA signaling pathway have been implicated in the development of hypertension, but many questions remain in regard to the mechanisms that control RhoA activity in SMCs (16, 28, 48).

We have recently shown that the Rho-specific GTPase activating protein (GAP), ARHGAP42, is selectively expressed in SMCs and controls blood pressure by inhibiting RhoA activity in resistance arterioles (2). Indeed, global ARHGAP42-deficient mice exhibited significant hypertension, and this effect was completely prevented by treatment of mice with the ROCK inhibitor, Y-27632, or by SMC-specific Cre-dependent reexpression of ARHGAP42. In addition to increasing our understanding of blood pressure control, these results also provided a mechanism for the blood pressure-associated locus identified within the first intron of the ARHGAP42 gene (9, 47). Given that the minor allele at this locus was associated with a decrease in blood pressure, we hypothesized that it increased ARHGPA42 expression by increasing the activity of a yet-to-be defined regulatory element. Using chromatin structure and sequence conservation data, we identified a SMC-selective intronic regulatory element encompassing the blood pressure-associated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs604723 that when deleted by CRISPR-Cas9-based methods, decreased endogenous ARHGAP42 expression in human aortic SMCs (3). We went on to show that the presence of the minor T allele at rs604723 created a low-affinity binding site for serum response factor (SRF) and that SRF binding to this sequence correlated with the transcriptional activity of this regulatory element and endogenous expression of the ARHGAP42 alleles.

Given the importance of ARHGAP42 in the control of SMC contractility and blood pressure homeostasis, the overall goal of the current study was to identify additional mechanisms that control ARHGAP42 expression in SMCs. Results presented herein indicate that the recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region (RBPJ) and TEA domain family member 1 (TEAD1) transcription factors are critical for ARHGAP42 expression and that they bind cooperatively to the intronic regulatory element. Our data also suggest that the ARHGAP42 expression is regulated by noncoding RNAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human aortic and bronchial SMCs (HuAoSMCs and HuBrSMCs, respectively) were purchased from Lonza and maintained in Clonetics smooth muscle growth medium-2 and supplemented with growth factors and 5% FBS. Multipotential 10T1/2 cells were maintained in DMEM + 10% FBS. For more information, refer to Supplemental table of the major resources at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9968405.

Plasmids.

The ARHGAP42 intron-1 DNase hypersensitivity (Int1DHS)-luciferase reporter construct was generated as previously described (3). RBPJ and TEAD1 mutations were introduced using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol. All mutations were verified by Sanger sequencing. The myc-TEAD1 plasmid was purchased from Addgene (Cat. No. 33109). For 3′-untranslated region (UTR) stability experiments, the ARHGAP42 3′-UTR was amplified from HuAoSMC genomic DNA by PCR and then cloned into pGL3 basic using In Fusion cloning (Clontech).

Luciferase assays.

HuBrSMCs were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells/well. 10T1/2 cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a density of 1.2 × 104 cells/well. Cells were transfected the day after plating with 50 or 25 ng of plasmid per well for 24 and 48-well plates, respectively. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection using the Steady-Glo Luciferase Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw luciferase values were normalized to the activity of the empty pGL3 vector. For Jagged-1 stimulation, transfected cells were trypsinized the following day and then replated on control or Jagged-coated dishes. In some experiments, N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine-t-butyl ester (DAPT) was added at 10 μM 24 h after promoter-luciferase transfections, and luciferase activity was measured 16 h later.

Jagged-1 stimulation.

Six-well plates were incubated with 3 μg of anti-human IgG (Fc-specific) (Sigma), diluted in PBS for 4 h at room temperature. After removal of residual antibody solution, wells were treated with 3 μg rat Jagged-1 human Fc recombinant protein (R&D Systems) or 3 μg human Fc recombinant protein (Millipore) as a control in PBS overnight at 4°C. HuBrSMCs were seeded onto coated plates for 16–24 h after and then harvested for luciferase assays or RNA isolation.

miR505 transfections.

HuBrSMCs were transfected with 80 nM of a micro-RNA 505 (miR505) or negative-control mimetic (Invitrogen) using the Lipofectamine-2000 reagent. Assays were performed 48 h after transfection.

Immunoprecipitations.

10T1/2 or COS cells were transfected with flag- and myc-tagged constructs for 48 h. Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer + 0.5% Triton X-100 and then incubated with antibody-conjugated beads for 2 h at 4°C with end-overend rotation. Beads were then washed three times in cold RIPA buffer and then twice with cold 1× TBS. Sample buffer (4×) was added to immunoprecipitated samples and then boiled for 5 min. Samples were loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE gel for Western blot analysis as previously described. For the detection of endogenous RBPJ interactions with TEAD1 and SRF, nuclei from HuBrSMCs were isolated using the NU-PER kit (Thermoscientific). Nuclear lysates were precleared by incubating extracts with IgG negative-control antibody linked to beads for 30 min at room temperature. Cleared nuclear lysates were then incubated with anti-TEAD1, RBPJ, or SRF antibodies (Santa Cruz) linked to protein A agarose beads for 2 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were run on SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed with SRF, RBPJ, and TEAD1 antibodies using standard Western blot analysis techniques. Specificity of antibodies was validated here using a standard knockdown approach. Additionally, all antibodies have been previously validated in a large number of studies.

Knockdowns.

HuBrSMCs were transfected with 20 to 80 nM siRNA targeted to TEAD1, SRF, RBPJ, or green fluorescent protein using the RNAiMax (Invitrogen) or Dharmafect (Dharmacon) transfection reagent. For knockdown of the AK124326 long noncoding RNA, HuBrSMC were transfected with 100 nM siRNA, using Dharmafect (Dharmacon) as the transfection reagent. Cells were assayed 48 to 72 h after transfection.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from cells using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and treated with DNase (Qiagen) to eliminate contaminating genomic DNA. RNA was converted to cDNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). cDNA (12–50 ng) was used for quantitative real-time PCR.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

HuAoSMC nuclear lysates were prepared using the Nuclear Isolation Kit from ThermoScientific and then dialyzed in Dignam’s buffer D, containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.1 M KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Each reaction contained 10 μg lysate or 1 μL in vitro translated-SRF, 20,000 counts/min of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe, and 0.20 μg poly-(2′-deoxyinosinic-2′-deoxycytidylic acid) in binding buffer, consisting of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DDT, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% glycerol.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed according to the X-ChIP protocol (Abcam) with slight modifications. In brief, HuBrSMCs were fixed for 10 min in 0.7% formaldehyde. The cross-linking reaction was stopped by incubating cells with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. Cells were scraped in lysis buffer, containing 5 mM PIPES (pH 8.0), 85 mM KCl, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and then nuclei were isolated by centrifugation at 2,300 g for 5 min. Nuclei were lysed in nuclear lysis buffer, consisting of 50 mM Tris·Cl (pH 8.1), 10 mM EDTA, and 0.13% SDS. Chromatin was sheared into 500-base pair (bp) fragments by sonication and immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with 1–5 μg of one of the following antibodies: anti-RBPJ (Cell Signaling), anti-Notch3 (Santa Cruz), anti-TEAD1 (Santa Cruz), anti-SRF (Santa Cruz), anti-yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1; Santa Cruz), anti-H3K9Ac (Upstate), nonimmune rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling), or nonimmune mouse IgG (Millipore). For re-ChIP assays, chromatin that was immuoprecipitated with the TEAD1 antibody was eluted with re-ChIP elution buffer, diluted 3 times with 1× ChIP buffer, and then incubated with 1 μg RBPJ antibody or 1 μg normal rabbit IgG antibody. In some experiments, cells were treated with DAPT (10 μM) or vehicle for 18 h before the start of fixation.

Statistics.

All data represent at least three separate experiments presented as means ± SE. Means were compared by two-tailed Student’s t-test or analysis of variance (where indicated), and statistical significance was considered as a P value of <0.05. All gels and Western blots shown are representative of at least two individual experiments.

RESULTS

Int1DHS activity was mediated by a 100-bp conserved region that bound RBPJ and TEAD1.

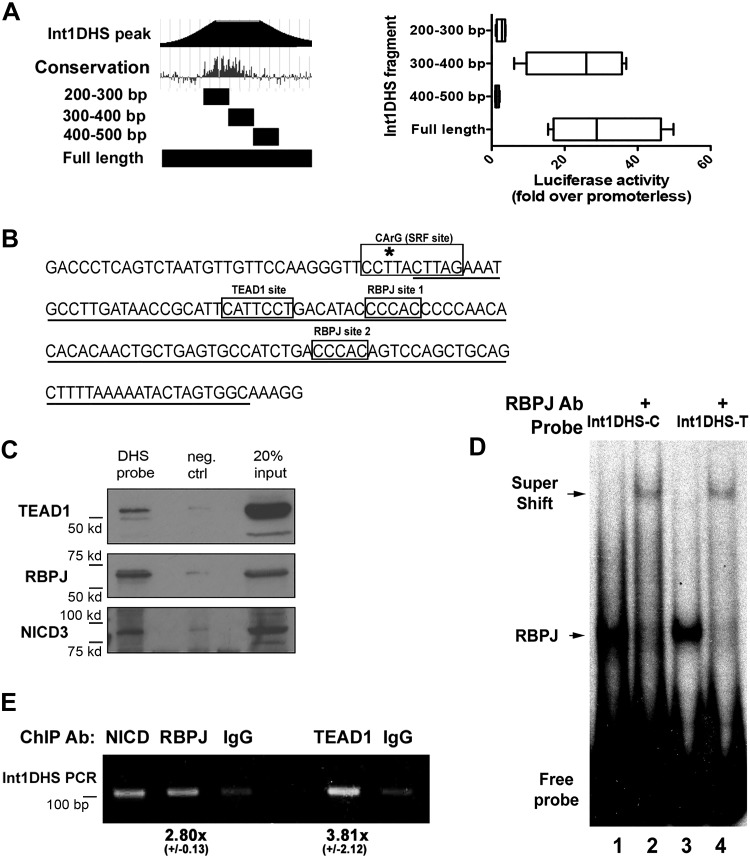

We have previously demonstrated that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of a 100-bp sequence at the center of a DNAse hypersensitive region within the ARHGAP42 first intron (Int1DHS) inhibited ARHGAP42 expression in SMCs. We also showed that the presence of the minor T allele at SNP rs604723 promoted SRF binding to increase ARHGAP42 expression (3). The Int1DHS variant that contains the major C allele at rs604723 did not bind SRF, but still exhibited very high transcriptional activity in luciferase assays (20-fold over empty vector), suggesting that SRF-independent mechanisms were critical for its activity (3). To begin to identify the mechanisms involved, we generated a series of Int1DHS deletions. As shown in Fig. 1A, most of the activity of the full-length major allele Int1DHS region was contained within a 100-bp conserved sequence (300–400 bp) just downstream of SNP rs604723.

Fig. 1.

A conserved 100-base pair (bp) region that binds RBPJ and TEAD1 mediated Int1DHS transcriptional activity. A: Int1DHS deletion fragments (left) were cloned into the luciferase vector and then transfected into HuBrSMCs. Luciferase activity was measured after 48 h and is expressed as fold over empty luciferase vector. B: schematic of the core sequence (underlined) and transcription factor binding sites (boxed) that mediate Int1DHS activity. *Location of single nucleotide variation (SNP) rs604723 (C/T). C: core Int1DHS sequence was biotin tagged, linked to streptavidin beads, and then incubated with HuAoSMC nuclear lysates. Washed precipitates were eluted, run on an SDS page gel, and subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies to TEAD1, RBPJ, and NICD3; n = 3, representative blots shown. D: gel shift assays were performed by incubating HuAoSMC nuclear extracts with radiolabeled 100-bp IntDHS oligonucleotide probes containing the major (C) or minor (T) rs604723 alleles and RBPJ binding site 1. RBPJ binding was confirmed by supershift with an RBPJ antibody (2nd and 4th columns). Note that RBPJ binding was not affected by the rs604723 variation; n = 2, representative blots shown. E: ChIP assays were performed in HuBrSMCs using antibodies to NICD3, RBPJ, and TEAD1 and PCR primer sets spanning the ARHGAP42 core Int1DHS region. Results were quantified by densitometry, normalized to input, and expressed relative to IgG control as means ± SE; n = 2. RBPJ, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region; TEAD1, TEA domain family member 1; Int1DHS, intron1 DNAse hypersensitive regulatory element; HuBrSMC, human bronchial smooth muscle cell; HuAoSMC, human aortic smooth muscle cell; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; NICD3, notch3 intracellular domain; SRF, serum response factor; neg ctrl, negative control.

With the help of the TRANSFAC database, we identified two GTGGG stretches that match the consensus binding sequence for the multifunctional Notch-related transcription factor, RBPJ (Fig. 1B). Notch-dependent transcription is activated when a Notch ligand (Jagged1 and -2; Delta-like 1, 3, and 5) engages the Notch receptor (Notch 1–4) on a neighboring cell, resulting in cleavage of the Notch receptor by γ-secretase. The released notch intracellular domain (NICD) then translocates to the nucleus where it binds to RBPJ (14). This binding interaction not only displaces transcriptional repressors that are bound to RBPJ in the absence of active Notch but also facilitates the recruitment of transcription activators such as mastermind-like transcriptional coactivator (MAML) and histone acetyl transferases. We and others have shown that RBPJ binds to a number of SMC-specific promoters (8, 38, 39, 44), and in vivo evidence suggests that Notch/RBPJ signaling is required for SMC differentiation from multiple precursors (5, 8, 15, 21). We also identified a consensus motif (CATTCC) for the TEAD factors that have been implicated in muscle-selective gene expression and are transcriptional mediators of the Hippo signaling pathway [see Fu et al. (12) for review].

We used several approaches to test whether RBPJ and TEAD1 (the TEAD family member most strongly implicated in SMC-selective gene expression) bound to the Int1DHS region. As shown in Fig. 1C, a biotin-conjugated 100-bp core probe precipitated RBPJ, the Notch3 intracellular domain (NICD3), and TEAD1 from HuAoSMC nuclear extracts. The fact that precipitation efficiency in these assays (IP:input) was higher for RBPJ than TEAD1 provides qualitative evidence that RBPJ binds to the Int1DHS with higher affinity in this assay. RBPJ binding was confirmed in gel-shift experiments in which we observed a prominent complex that was completely supershifted upon addition of an RBPJ Ab (Fig. 1D). It is important to note that the rs604723 variation that promotes relatively weak SRF binding had no effect on the binding of RBPJ in gel-shift assays. In further support of these data, we used targeted ChIP assays to demonstrate that RBPJ and TEAD1 bound to the endogenous ARHGAP42 Int1DHS region in SMCs (Fig. 1E).

Int1DHS activity and ARHGAP42 expression were regulated by Notch/RBPJ signaling.

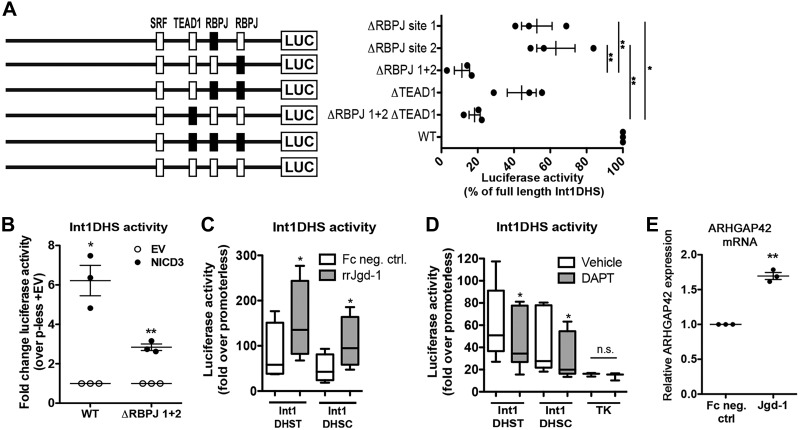

To test whether the RBPJ and TEAD1 binding sites contributed to the transcriptional activity of the core-Int1DHS region, we mutated each site separately and in combination within the context of the full-length 604-bp Int1DHS region. As shown in Fig. 2A, mutation to RBPJ site 1 significantly decreased full-length DHS activity by ~50%. whereas mutation of both sites reduced activity by over 85%. These results suggested that RBPJ/Notch was required for the full activity of the Int1DHS region and that these two sites may act cooperatively. We next used several gain/loss of function approaches to test whether Notch3, the major Notch receptor subtype expressed in SMCs, was required for Int1DHS activity (14). Overexpression of NICD3 significantly increased the activity of the Int1DHS fragment, and this effect was significantly diminished by mutation of both RPBJ binding sites (Fig. 2B). Activation of endogenous Notch signaling by seeding SMCs on recombinant Jagged-1 increased Int1DHS-luciferase activity (Fig. 2C), whereas inhibition of Notch receptor cleavage with the γ-secretase inhibitor, DAPT, reduced Int1DHS-luciferase activity (Fig. 2D). The effects of Notch signaling on Int1DHS activity were similar for both rs604723 alleles, indicating that they were SRF independent. Importantly, plating human SMCs on Jagged-1 ligand upregulated endogenous ARHGAP42 expression as measured by quantitative Taqman-based RT-PCR (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

RBPJ/Notch was required for Int1DHS transcriptional activity and ARHGAP42 expression. A: as depicted, the RBPJ and TEAD1 binding sites were mutated separately and in combination within the context of the full-length Int1DHS-luciferase (LUC) construct. Black boxes represent mutated sites. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection into HuBrSMCs and is expressed relative to the wild-type (WT) construct set to 100%. *P < 0.05, all mutated constructs were different from WT. **P < 0.05, RBPJ 1 vs. RBPJ 1+2, RBPJ 2 vs. RBPJ 1+2, and RBPJ 2 vs. RBPJ 2 + RBPJ 1+2 TEAD1 (ANOVA); n = 3. B: WT and ΔRBPJ1+2 Int1DHS-luciferase constructs were cotransfected into 10T1/2 cells along with Flag-NICD3. *P < 0.05 vs. WT plus empty vector (EV); **P < 0.05 vs. WT plus NICD3 (ANOVA); n = 3. C: HuBrSMCs were transfected with full-length Int1DHS-luciferase constructs containing either the major C or minor T allele at rs604723. After 24 h, cells were split and seeded onto plates coated with recombinant rat Jagged-1 (rrJgd-1) or control Fc protein. *P < 0.05, compared with Fc negative control (t-test); n = 4. D: HuBrSMCs were transfected with a luciferase construct driven by the minimal thymidine kinase promoter (TK) or a full-length Int1DHS-luciferase construct containing either the major C or minor T allele at rs604723. N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine-t-butyl ester (DAPT; 10 μM) or vehicle were added 24 h after transfection, and luciferase activity was measured after another 16 h. *P < 0.05, compared with vehicle treated (t-test); n = 6. E: endogenous ARHGAP42 expression was measured by RT-PCR in HuAoSMCs plated on recombinant Jagged-1 or control Fc protein for 24 h. *P < 0.01 vs. Fc negative control (neg ctrl) (t-test); n = 3. RBPJ, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region; Int1DHS, intron1 DNAse hypersensitive regulatory element; TEAD1, TEA domain family member 1; HuBrSMC, human bronchial smooth muscle cell; NICD3, notch3 intracellular domain; HuAoSMC, human aortic smooth muscle cell; SRF, serum response factor; bp, base pair.

RBPJ and TEAD1 interacted to regulate Int1DHS activity.

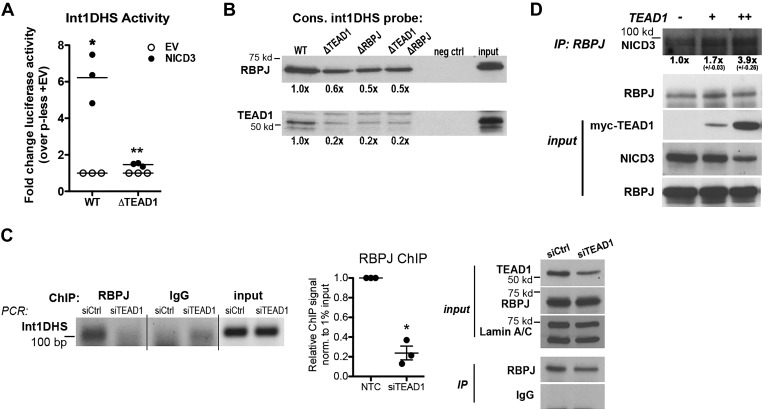

To further test the importance of TEAD1, we used siRNA to knock down TEAD1 expression by ~70% in HuBrSMCs (see Fig. 4C). As shown in Fig. 3A, ARHGAP42 expression was significantly downregulated in TEAD1-deficient cells as measured by quantitative PCR. Given the proximity of the TEAD1 and RBPJ binding sites within the Int1DHS, we hypothesized that these two factors interacted physically to facilitate the formation of a larger transcription complex. In strong support of this idea, exogenous and endogenous RBPJ and TEAD1 were strongly coimmunoprecipitated from COS cells and human bronchial SMCs, respectively (Figs. 3, B and C). To determine whether RBPJ and TEAD1 were bound to the Int1DHS at the same time, we performed a re-ChIP assay for RBPJ binding using DNA that had been previously immunoprecipitated with a TEAD1 antibody. As a negative control in these experiments, an IgG antibody was incubated with an equal fraction of TEAD1 ChIP DNA. As shown in Fig. 3D, we observed significant enrichment of Int1DHS DNA in the RBPJ ChIPed sample strongly supporting co-occupancy of these factors.

Fig. 4.

Cooperative interaction between RBPJ and TEAD1 regulated Int1DHS activity. A: wild-type (WT) and ΔTEAD1 Int1DHS-luciferase constructs were cotransfected into 10T1/2 cells along with Flag-NICD3. *P < 0.05 vs. WT plus empty vector (EV); **P < 0.05 vs. WT plus NICD3 (ANOVA); n = 3. p-less, promotorless. B: HuBrSMC nuclear extracts were incubated with 100-base pair (bp) biotin-conjugated probes containing the indicated WT or mutated sequences. Following incubation with streptavidin beads and extensive washing, eluted proteins were separated on and SDS page gel and then analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies to TEAD1 and RBPJ. Binding was quantified by densitometry and is expressed relative to WT set to 1 as means ± SE; n = 2. C: HuBrSMCs were treated with siRNAs targeting TEAD1 or green fluorescent protein (GFP). Targeted ChIP assays were performed in TEAD1 knockdown and control HuBrSMCs using antibodies to RBPJ and PCR primers spanning the ARHGAP42 core Int1DHS region. Results were quantified by densitometry, normalized (norm) to input and expressed relative to IgG control as means ± SE. *P < 0.01 vs. control (Ctrl) siRNA; n = 3. D: 10T1/2 cells were transfected with increasing amounts of myc-TEAD1, and lysates were incubated with RBPJ antibody. Immunoprecipitated (IP) samples were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-Notch3 antibody. NICD3 coimmunoprecipitation (D, top) was quantified by densitometry and is expressed relative to plus empty expression vector set to 1 means ± SE; n = 2. RBPJ, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region; TEAD1, TEA domain family member 1; Int1DHS, intron1 DNAse hypersensitive regulatory element; NICD3, notch3 intracellular domain; HuBrSMC, human bronchial smooth muscle cell; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; NTC, nontargeted control.

Fig. 3.

TEAD1 was required for ARHGAP42 expression. A: HuBrSMCs were treated with TEAD1 or control siRNA for 72 h, and ARHGAP42 expression was measured by quantitative PCR. *P < 0.05 vs. control (Ctrl) siRNA (t-test); n = 3. B: COS-7 cells were transfected with flag-RBPJ and myc-TEAD1, and immunoprecipitation was carried out 48 h later by incubating lysates with an anti-myc antibody. Immunoprecipitated (IP) samples were eluted, run on an SDS page gel, and subjected to Western blot analysis using an RBPJ antibody; n = 2, representative blot shown. C: HuBrSMC nuclear extracts were incubated with TEAD1 Ab conjugated to agarose beads. Washed TEAD1 immunoprecipitates were eluted, run on an SDS page gel, and subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies to TEAD1 and RBPJ; n = 3, representative blot shown. D: TEAD1 ChIP DNA that was still cross-linked was immunoprecipitated with RBPJ or control IgG antibody. PCR on re-ChIPed DNA was performed using primers spanning the Int1DHS. Results were quantified by densitometry, normalized to input, and expressed relative to IgG control as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. IgG (t-test); n = 3. TEAD1, TEA domain family member 1; HuBrSMC, human bronchial smooth muscle cell; RBPJ, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; Int1DHS, intron1 DNAse hypersensitive regulatory element; bp, base pair.

Importantly, a mutation to the TEAD1 binding site attenuated the positive transcriptional effects of NICD3 overexpression by 77% (Fig. 4A), perhaps suggesting that TEAD1 facilitates RBPJ and/or NICD3 binding to the ARHGAP42 Int1DHS. To begin to assess these potential cooperative interactions, we performed pull-down assays with a 100-bp DNA probe consisting of the conserved Int1DHS region that contained mutations to the juxtaposed RBPJ and TEAD1 binding sites. As shown in Fig. 4B, mutation to either site reduced binding of both transcription factors, indicating at least some level of cooperativity. The fact that RBPJ binding at the endogenous Int1DHS (as measured by ChIP) was significantly decreased in TEAD1 knockdown SMCs also supports this idea (Fig. 4C). To test whether the RBPJ-TEAD interaction affected the ability of RBPJ to recruit the NICD, we performed RBPJ-NICD3 coimmunoprecipitation experiments in cells overexpressing increasing amounts of TEAD1. As shown in Fig. 4D, the RBPJ-NICD3 interaction correlated directly with TEAD1 expression levels.

SRF and Notch activation were required for RBPJ, TEAD1, and YAP1 recruitment to the Int1DHS.

Although RBPJ binding to and Notch-dependent regulation of the Int1DHS enhancer were independent of SRF, we had previously shown that SRF was a major regulator of ARHGAP42 expression. To further address the relationship between SRF and RBPJ binding, we performed ChIP assays in SMCs treated with siRNAs for SRF and RBPJ. As shown in Fig. 5A, SRF depletion completely inhibited RBPJ binding to the Int1DHS, whereas RBPJ depletion had little effect on SRF binding. Because we did not detect protein-protein interactions between SRF and RBPJ (Fig. 5B), it is likely that SRF promotes RBPJ binding by more indirect mechanisms. To study the role of Notch activation on transcription complex formation at the Int1DHS enhancer, we performed additional ChIP assays in the presence and absence of DAPT. As expected, DAPT significantly decreased binding of NICD3 to the IntDHS enhancer, but it also significantly decreased binding of TEAD1 and YAP1. RBPJ binding was similarly reduced, but this difference did not reach significance. DAPT treatment had little effect on SRF binding to the Int1DHS, providing additional evidence that Notch signaling was not required for SRF recruitment. Importantly, DAPT did not affect H3K9 acetylation, suggesting that its effects were not due to repressive changes in chromatin structure at the Int1DHS.

Fig. 5.

SRF and Notch signaling regulated transcription complex formation at the Int1DHS. A: HuBrSMCs were treated with siRNAs targeting SRF, RBPJ, or green fluorescent protein (GFP) for 48 h. Targeted ChIP assays were performed using antibodies to SRF and RBPJ and PCR primers spanning the ARHGAP42 Int1DHS. Results were quantified by densitometry, normalized to input, and expressed relative to control (Ctrl) siRNA set to 1; n = 1. B: HuBrSMC lysates were incubated with antibodies to SRF, RBPJ, or nonimmune rabbit IgG. Washed immunoprecipitates (IP) were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels, and Western blots were probed for SRF or RBPJ; n = 2, representative blot shown. C: HuBrSMCs were treated with N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine-t-butyl ester (DAPT) for 16 h and then subjected to ChIP assays using the indicated antibodies and PCR primers spanning the Int1DHS. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle treated (t-test); n = 3. SRF, serum response factor; Int1DHS, intron1 DNAse hypersensitive regulatory element; HuBrSMC, human bronchial smooth muscle cell; RBPJ, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; TEAD1, TEA domain family member 1; YAP1, yes-associated protein 1; norm, normalized.

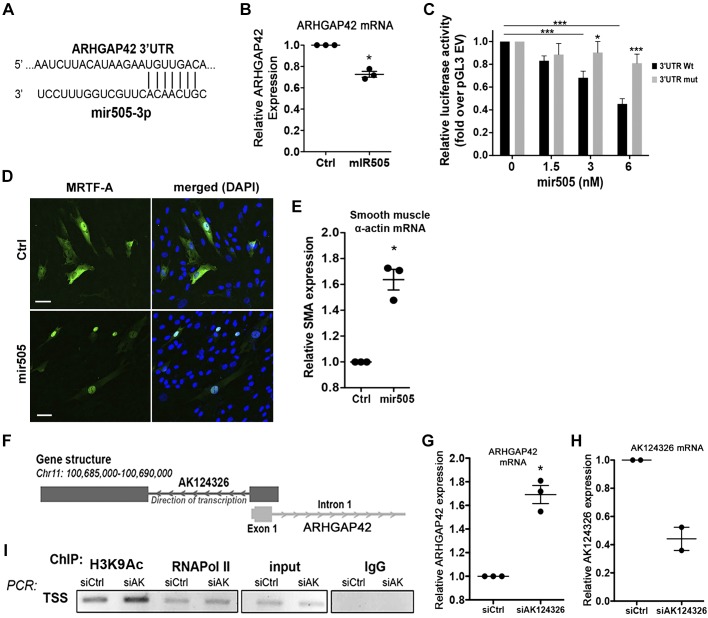

ARHGAP42 expression was regulated by noncoding RNAs.

To identify additional mechanisms that control ARHGAP42 levels, we used the Target Scan algorithm on the University of California, Santa Cruz, genome browser to identify micro RNA (miRs) that could potentially interact with the ARHGAP42 message. Conserved miR505 received the highest score, and as shown in Fig. 6A, was predicted to target the 3′-UTR of the ARHGAP42 mRNA that we had previously characterized by RNA sequencing (3). To begin to assess the role of miR505, we transfected a miR505 mimetic into HuBrSMCs and measured ARHGAP42 expression by quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 6B, miR505 modestly reduced endogenous ARHGAP42 mRNA levels by 25%. To test whether the effects of miR505 were due to destabilization of the ARHGAP42 message, we cloned the most distal 1.2 kb of the ARHGAP42 3′-UTR downstream of the luciferase gene within the context of the promoterless pGL3 vector. The presence of this 3′-UTR fragment increased luciferase activity by ~10-fold (overempty pGL3 vector), suggesting that this region had a stabilizing effect on the luciferase message (data not shown). Importantly, cotransfection of miR505 with the luciferase-3′-UTR plasmid resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in luciferase activity but had no significant effect on the luciferase-3′-UTR construct in which the miR505 binding sited had been mutated (Fig. 6C). Taken together these data strongly suggest that miR505 facilitates the degradation of the ARHGAP42 mRNA. To assess the physiological consequences of miR505-mediated ARHGAP42 downregulation on RhoA-dependent events in SMCs, we examined its effects on myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF)-A localization and smooth muscle α-actin expression (Fig. 6, D and E). Both of these end points were significantly elevated strongly, suggesting that RhoA activity is higher in miR505-treated cells.

Fig. 6.

ARHGAP42 expression was negatively regulated by micro-RNA (miR)505-3p and LncRNA AK124326. A: sequence pairing between miR505 and the ARHGAP42 3′-untranslated region (UTR). B: HuBrSMCs were transfected with a miR505 mimetic (80 nM) or scrambled control (Ctrl) miR. ARGAHP42 expression was measured 48 h later by quantitative RT-PCR. *P < 0.05 (t-test); n = 3. C: 1.2-Kb fragment of the ARHGAP42 3′-UTR was cloned downstream of the luciferase cDNA in the pGL3 basic vector, and the miR505 binding site was mutated by site-directed mutagenesis. Wild-type (WT) or mutant (Mut) constructs were transfected into 10T1/2 cells along with increasing concentration of miR505. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h later. ***P < 0.001 (ANOVA), n = 10. D: HuBrSMCs were treated with mir505-3p and then transfected with a green fluorescent protein-myocardin-related transcription factor-A (GFP-MRTF-A) fusion protein. Slides were fixed and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Scale bar, 50 μm. E: α-smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) expression was measured by TaqMan RT-PCR in HuBrSMCs treated with miR505-3p mimic. *P < 0.05 vs. control (t-test); n = 3. F: schematic of AK124326 gene positioning in relation to the ARHGAP42 first exon. G and H: ARHGAP42 and AK124326 mRNA levels were measured in HuBrSMCs transfected with AK124326 or control siRNA. *P < 0.05 vs. control siRNA (t-test); n = 3. I: ChIP assays were performed in HuBrSMCs treated with AK124326 or control siRNA using antibodies to acetylated H3K9 and RNA Pol-II and primer sets targeted to the ARHGAP42 transcription start site (TSS); n = 2. HuBrSMC, human bronchial smooth muscle cell; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; EV, empty vector.

As shown in Fig. 6F, a long noncoding RNA, AK124326, has been described that overlaps with the ARHGAP42 transcription start site but is transcribed in the opposite direction. Since LncRNAs have been shown to affect gene expression by a variety of cis and trans mechanisms [see Guttman et al. (18) for review], we measured ARHGAP42 expression in HuBrSMCs treated with siRNA to AK124326. As shown in Fig. 6, G and H, knocking down AK124326 by ~60% resulted in a twofold increase in ARHGAP42 expression. Targeted ChIP assays demonstrated that this increase was accompanied by elevated levels of H3K9 acetylation and RNA Pol-II binding at the ARHGAP42 transcription start site (Fig. 6I). AK124326 contains a short open reading frame that could potentially result in the production of a small peptide. To test the importance of this mechanism, we cloned this reading frame into a Flag-tagged expression vector and transfected this construct into HuAoSMCs. We did not observe detectable expression under these conditions (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We previously demonstrated that the smooth muscle-selective Rho-specific GAP, ARHGAP42, was required for blood pressure regulation and provided evidence that the rs604723 minor allele enhanced ARHGAP42 expression by promoting SRF binding to a novel enhancer within the ARHGAP42 first intron (2, 3). In the current study, we identified several additional mechanisms that control ARHGAP42 expression and provide evidence that the RBPJ and TEAD1 transcription factors regulate endogenous ARHGAP42 expression, at least in part, by controlling the activity of the Int1DHS enhancer.

The RBPJ/Notch and TEAD/YAP transcription pathways are important regulators of cell fate and function in many cell types including SMCs [see Fu et al. (12) and Gridley (14) for reviews]. Several conditional in vivo mouse models have been used to show that Notch/RBPJ signaling was critical for SMC differentiation of epicardial cells (7, 15), cardiac neural crest cells (21), and Tie-1 expressing stem cells (5). Although RBPJ binding sites have been described in the smooth muscle α-actin and smooth muscle myosin heavy-chain promoters (38, 44), RBPJ/Notch signaling has been shown to have both positive and negative effects on SMC-specific promoter activity, suggesting context-dependent regulation by this pathway (8, 26, 31, 38, 39, 44). The precise cause of these discrepancies is unknown but likely involves variable levels of Notch activity between model systems; differential upregulation (timing and/or magnitude) of the Notch target genes, Hes and Hey, which can inhibit differentiation (44); and/or the ability of RBPJ to function as a direct repressor in the absence of Notch signaling. TEAD1 and TEAD4 are relatively highly expressed in muscle tissues (23, 46), and TEAD-binding cis elements were shown to be important for SMC-specific promoter activity (43). However, as with RBPJ/Notch, these effects were also context dependent (13, 43) perhaps due to model-dependent differences in Hippo signaling, the expression of TEAD family members, or TEAD interactions with additional transcription regulators such as MEF2 (17, 24).

Although most studies on the SRF/myocardin factor, RBPJ/Notch, and TEAD/YAP pathways in SMCs have assessed these transcription factors individually; several lines of evidence from this study and others suggest that cooperation between these pathways may be a critical determinant of SMC-specific gene expression. First, SRF, RBPJ, and TEAD1 cis elements are present together in many SMC-specific genes and have been directly implicated in the regulation of smooth muscle α-actin promoter activity (13, 30, 45). More recent ChIP seq experiments demonstrated significant binding overlap between these transcription factors. For example, the consensus TEAD binding site was overrepresented in SRF ChIP seq datasets in both HL1 cardiac and NIH3T3 cells (10, 20), and we have recently shown using ChIP seq approaches that SRF and RBPJ binding exhibited remarkable overlap in HuAoSMCs (39). Second, a number of studies including this one have shown physical and functional interactions between these transcription factors and their cofactors. SRF and TEAD1 were shown to interact to regulate muscle-selective gene expression (17, 20, 27), whereas more recent studies demonstrated that YAP and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ binding motif (TAZ) interacted with the MRTFs (25, 33, 42) and that SRF/MRTF and TEAD/YAP pathways regulated similar sets of genes (11). Although our data showed that SRF depletion inhibited RBPJ binding to the Int1DHS, we did not detect a physical interaction between these factors, making it difficult to conclude SRF directly recruits RBPJ to the Int1DHS. It is well known that SRF and the myocardin factors promote positive chromatin remodeling, and we have previously shown that SRF binding to the minor allele at rs604723 was associated with increased DNAse sensitivity at the Int1DHS region (3). Thus, we feel that our data support a model in which SRF promotes an open chromatin state that facilitates RBPJ binding to the Int1DHS region (see Fig. 7). Given the presence of additional SRF binding sites including one within the ARHGAP42 transcription start site (TSS) (39), it is likely that SRF promotes positive chromatin remodeling across the entire ARHGAP42 gene.

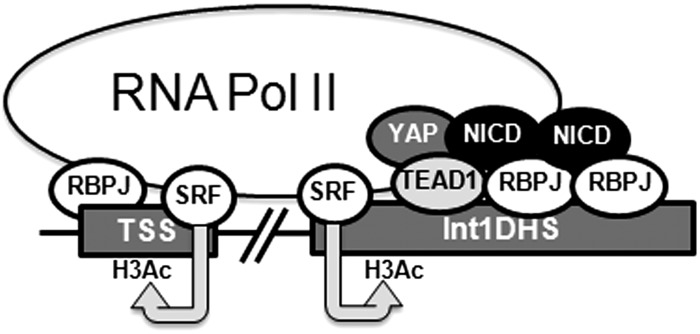

Fig. 7.

Transcription complex formation at the ARHGAP42 Int1DHS enhancer. Data from the present and previous studies suggest that SRF promotes RBPJ binding to the ARHGAP42 Int1DHS through positive effects on chromatin structure not by direct protein-protein interactions between these factors. RBPJ and TEAD1 bind cooperatively to conserved cis elements within the Int1DHS just downstream of the low-affinity SRF binding site created by the presence of the minor rs604723 allele. Recruitment of the NICD3 to RBPJ (and perhaps TEAD1) helps to stabilize the enhancer complex and to the further recruitment of the TEAD1 cofactor, YAP1. Given the presence of an additional SRF/RBPJ binding region at the ARHGAP42 transcription start site (TSS), it is likely that the Int1DHS and TSS regions cooperate to drive the smooth muscle cell-selective expression of ARHGAP42. Int1DHS, intron1 DNAse hypersensitive; SRF, serum response factor; RBPJ, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin κ-J region; TEAD1, TEA domain family member 1; NICD3, notch3 intracellular domain; YAP1, yes-associated protein 1; H3Ac, acetylated Histone H3.

To our knowledge the present study is the first to demonstrate a physical interaction between RBPJ and TEAD1, and the observation that DAPT significantly decreased binding of TEAD1 and YAP1 to the Int1DHS provides further support for the emerging idea of cross talk between the Notch and Hippo pathways. For example, Manderfield et al. (32) have shown that the NICD binds YAP and that YAP can be recruited to DNA by RBPJ. In the current study, the TEAD1 binding site was required for transactivation of the core-Int1DHS enhancer by the NICD. indicating that TEAD1 was either required for RBPJ binding or that TEAD1 helps to recruit the NICD under these conditions. In support of the later possibility, Rayon et al. (36) demonstrated in HEK cells that TEAD4 binding was required for NICD-dependent activation of an enhancer within the CDX2 gene. The fact that DAPT had little effect on H3K9 acetylation strongly suggests that the positive effects of Notch activation are likely due to changes in transcription factor recruitment to an already open chromatin region and not to overall changes in chromatin structure at the Int1DHS. We are currently testing whether this combination of cis elements serves as a “transcriptional cassette” that helps drive SMC-specific gene expression. It will also be interesting to test whether combinatorial activation of RhoA, Notch, and Hippo signaling can induce SMC differentiation from undifferentiated precursors.

It is clear that tight control of ARHGAP42 expression is a key mechanism for regulating blood pressure in mice and humans. Similar to other SMC markers, ARHGAP42 is significantly upregulated by signals that enhance RhoA-dependent nuclear translocation of the MRTFs (3, 4). When coupled with the observations that ARHGAP42 expression was significantly increased in vessels from hypertensive mice and that ARHGAP42 expression was upregulated by cell stretch (3), we hypothesize that this mechanism serves as a functional rheostat to limit excessive RhoA activity under these conditions (4). Interestingly, actin polymerization has also been shown to promote the nuclear translocation of YAP and TAZ (11, 42), suggesting that cross talk between these cofactors and that the MRTFs may be important for fine-tuning ARHGAP42 expression.

Our results also implicate posttranscriptional mechanisms in the control of ARHGAP42 expression. The long noncoding RNA, AK124326, is particularly interesting in this regard because the AK124326 and ARHGAP42 transcription start sites overlap in opposite directions and because the mature AK124326 message contains sequence that is antisense to the entire ARHGAP42 first exon. The results of our knockdown experiments indicated that AK124326 is a negative regulator of ARHGAP42 message levels in HuBrSMCs. Although we cannot completely rule out an antisense mechanism, the positive changes in chromatin structure and Pol-II binding that we observed in AK124326-deficient cells suggests that AK124326 inhibits ARHGAP42 transcription. Previous studies have shown that long noncoding RNAs positioned near TSSs can inhibit gene expression by acting as transcription factor sinks, and it will be important to address this possibility. Interestingly, Hu et al. (22) recently reported ARHGAP42 expression was upregulated in nasopharyngeal cancer cells and that knockdown of AK124326 resulted in decreased ARHGAP42 expression in this model. While ARHGAP42 is not normally expressed in noncancerous nasopharyngeal cells, these results suggest that the effects of AK124326 may be context dependent.

Our data strongly indicated that miR505 decreases ARHGAP42 expression in SMCs by promoting the degradation of ARHGAP42 message. Of considerable importance, Yang et al. (49) recently demonstrated that miR505 levels were more than twofold higher in serum samples taken from 101 patients with hypertension than in those taken from 90 normotensive controls, suggesting it may play a role in blood pressure regulation. Although these authors suggested that miR505's effects on blood pressure were mediated by its effects in endothelial cells, our demonstration that miR505 increased smooth muscle α-actin expression and MRTF-A nuclear localization suggests that miR505's effects on blood pressure could be mediated by increased RhoA signaling in vascular SMCs. It is difficult to exclude the possibility that miR505 has non-ARHGAP42 targets that regulate SMC marker gene expression and RhoA-dependent MRTF-A nuclear localization, and future experiments are needed to examine whether miR505 is a significant regulator of SMC phenotype.

In summary, our results suggest that SRF, RBPJ, and TEAD1 converge at an enhancer element within the ARHGAP42 first intron. Since this enhancer likely mediates the effects of blood pressure associate variants in this region, further characterization of these interactions should provide a better understanding of the genetics of blood pressure and the mechanisms that control SMC-selective gene expression.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-109607 (to C. P. Mack), HL-130367 (to J. M. Taylor and C. P. Mack), and T32-HL-69768 (to K. D. Mangum) and American Heart Fellowship Grant 15PRE25340001 (to K. D. Mangum).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.D.M., J.M.T., and C.P.M. conceived and designed research; K.D.M., E.J.F., J.C.M., and C.P.M. performed experiments; K.D.M., J.M.T., and C.P.M. analyzed data; K.D.M. and C.P.M. interpreted results of experiments; K.D.M. and C.P.M. prepared figures; K.D.M. and C.P.M. drafted manuscript; K.D.M. and C.P.M. edited and revised manuscript; K.D.M. and C.P.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aittaleb M, Boguth CA, Tesmer JJ. Structure and function of heterotrimeric G protein-regulated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Mol Pharmacol 77: 111–125, 2010. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai X, Lenhart KC, Bird KE, Suen AA, Rojas M, Kakoki M, Li F, Smithies O, Mack CP, Taylor JM. The smooth muscle-selective RhoGAP GRAF3 is a critical regulator of vascular tone and hypertension. Nat Commun 4: 2910, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai X, Mangum KD, Dee RA, Stouffer GA, Lee CR, Oni-Orisan A, Patterson C, Schisler JC, Viera AJ, Taylor JM, Mack CP. Blood pressure-associated polymorphism controls ARHGAP42 expression via serum response factor DNA binding. J Clin Invest 127: 670–680, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI88899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai X, Mangum K, Kakoki M, Smithies O, Mack CP, Taylor JM. GRAF3 serves as a blood volume-sensitive rheostat to control smooth muscle contractility and blood pressure. Small GTPases. 2017 Nov 3 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/21541248.2017.1375602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang L, Noseda M, Higginson M, Ly M, Patenaude A, Fuller M, Kyle AH, Minchinton AI, Puri MC, Dumont DJ, Karsan A. Differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells from local precursors during embryonic and adult arteriogenesis requires Notch signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 6993–6998, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118512109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowley AW., Jr The genetic dissection of essential hypertension. Nat Rev Genet 7: 829–840, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrg1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.del Monte G, Casanova JC, Guadix JA, MacGrogan D, Burch JB, Pérez-Pomares JM, de la Pompa JL. Differential Notch signaling in the epicardium is required for cardiac inflow development and coronary vessel morphogenesis. Circ Res 108: 824–836, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.229062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi H, Iso T, Sato H, Yamazaki M, Matsui H, Tanaka T, Manabe I, Arai M, Nagai R, Kurabayashi M. Jagged1-selective notch signaling induces smooth muscle differentiation via a RBP-Jkappa-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 281: 28555–28564, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, Chasman DI, Smith AV, Tobin MD, Verwoert GC, Hwang SJ, Pihur V, Vollenweider P, O’Reilly PF, Amin N, Bragg-Gresham JL, Teumer A, Glazer NL, Launer L, Zhao JH, Aulchenko Y, Heath S, Sõber S, Parsa A, Luan J, Arora P, Dehghan A, Zhang F, Lucas G, Hicks AA, Jackson AU, Peden JF, Tanaka T, Wild SH, Rudan I, Igl W, Milaneschi Y, Parker AN, Fava C, Chambers JC, Fox ER, Kumari M, Go MJ, van der Harst P, Kao WH, Sjögren M, Vinay DG, Alexander M, Tabara Y, Shaw-Hawkins S, Whincup PH, Liu Y, Shi G, Kuusisto J, Tayo B, Seielstad M, Sim X, Nguyen KD, Lehtimäki T, Matullo G, Wu Y, Gaunt TR, Onland-Moret NC, Cooper MN, Platou CG, Org E, Hardy R, Dahgam S, Palmen J, Vitart V, Braund PS, Kuznetsova T, Uiterwaal CS, Adeyemo A, Palmas W, Campbell H, Ludwig B, Tomaszewski M, Tzoulaki I, Palmer ND, Aspelund T, Garcia M, Chang YP, O’Connell JR, Steinle NI, Grobbee DE, Arking DE, Kardia SL, Morrison AC, Hernandez D, Najjar S, McArdle WL, Hadley D, Brown MJ, Connell JM, Hingorani AD, Day IN, Lawlor DA, Beilby JP, Lawrence RW, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Ongen H, Dreisbach AW, Li Y, Young JH, Bis JC, Kähönen M, Viikari J, Adair LS, Lee NR, Chen MH, Olden M, Pattaro C, Bolton JA, Köttgen A, Bergmann S, Mooser V, Chaturvedi N, Frayling TM, Islam M, Jafar TH, Erdmann J, Kulkarni SR, Bornstein SR, Grässler J, Groop L, Voight BF, Kettunen J, Howard P, Taylor A, Guarrera S, Ricceri F, Emilsson V, Plump A, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Weder AB, Hunt SC, Sun YV, Bergman RN, Collins FS, Bonnycastle LL, Scott LJ, Stringham HM, Peltonen L, Perola M, Vartiainen E, Brand SM, Staessen JA, Wang TJ, Burton PR, Soler Artigas M, Dong Y, Snieder H, Wang X, Zhu H, Lohman KK, Rudock ME, Heckbert SR, Smith NL, Wiggins KL, Doumatey A, Shriner D, Veldre G, Viigimaa M, Kinra S, Prabhakaran D, Tripathy V, Langefeld CD, Rosengren A, Thelle DS, Corsi AM, Singleton A, Forrester T, Hilton G, McKenzie CA, Salako T, Iwai N, Kita Y, Ogihara T, Ohkubo T, Okamura T, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Eyheramendy S, Meitinger T, Wichmann CO, Cho YS, Kim HL, Lee JY, Scott J, Sehmi JS, Zhang W, Hedblad B, Nilsson P, Smith GD, Wong A, Narisu N, Stančáková A, Raffel LJ, Yao J, Kathiresan S, O’Donnell CJ, Schwartz SM, Ikram MA, Longstreth WT Jr, Mosley TH, Seshadri S, Shrine NR, Wain LV, Morken MA, Swift AJ, Laitinen J, Prokopenko I, Zitting P, Cooper JA, Humphries SE, Danesh J, Rasheed A, Goel A, Hamsten A, Watkins H, Bakker SJ, van Gilst WH, Janipalli CS, Mani KR, Yajnik CS, Hofman A, Mattace-Raso FU, Oostra BA, Demirkan A, Isaacs A, Rivadeneira F, Lakatta EG, Orru M, Scuteri A, Ala-Korpela M, Kangas AJ, Lyytikäinen LP, Soininen P, Tukiainen T, Würtz P, Ong RT, Dörr M, Kroemer HK, Völker U, Völzke H, Galan P, Hercberg S, Lathrop M, Zelenika D, Deloukas P, Mangino M, Spector TD, Zhai G, Meschia JF, Nalls MA, Sharma P, Terzic J, Kumar MV, Denniff M, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Wagenknecht LE, Fowkes FG, Charchar FJ, Schwarz PE, Hayward C, Guo X, Rotimi C, Bots ML, Brand E, Samani NJ, Polasek O, Talmud PJ, Nyberg F, Kuh D, Laan M, Hveem K, Palmer LJ, van der Schouw YT, Casas JP, Mohlke KL, Vineis P, Raitakari O, Ganesh SK, Wong TY, Tai ES, Cooper RS, Laakso M, Rao DC, Harris TB, Morris RW, Dominiczak AF, Kivimaki M, Marmot MG, Miki T, Saleheen D, Chandak GR, Coresh J, Navis G, Salomaa V, Han BG, Zhu X, Kooner JS, Melander O, Ridker PM, Bandinelli S, Gyllensten UB, Wright AF, Wilson JF, Ferrucci L, Farrall M, Tuomilehto J, Pramstaller PP, Elosua R, Soranzo N, Sijbrands EJ, Altshuler D, Loos RJ, Shuldiner AR, Gieger C, Meneton P, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Gudnason V, Rotter JI, Rettig R, Uda M, Strachan DP, Witteman JC, Hartikainen AL, Beckmann JS, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS, Boehnke M, Larson MG, Järvelin MR, Psaty BM, Abecasis GR, Chakravarti A, Elliott P, van Duijn CM, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Caulfield MJ, Johnson T; International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association StudiesCARDIoGRAM consortiumCKDGen ConsortiumKidneyGen ConsortiumEchoGen consortium; CHARGE-HF consortium . Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature 478: 103–109, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esnault C, Stewart A, Gualdrini F, East P, Horswell S, Matthews N, Treisman R. Rho-actin signaling to the MRTF coactivators dominates the immediate transcriptional response to serum in fibroblasts. Genes Dev 28: 943–958, 2014. doi: 10.1101/gad.239327.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster CT, Gualdrini F, Treisman R. Mutual dependence of the MRTF-SRF and YAP-TEAD pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts is indirect and mediated by cytoskeletal dynamics. Genes Dev 31: 2361–2375, 2017. doi: 10.1101/gad.304501.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu V, Plouffe SW, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ development, homeostasis, and regeneration. Curr Opin Cell Biol 49: 99–107, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gan Q, Yoshida T, Li J, Owens GK. Smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts use distinct transcriptional mechanisms for smooth muscle alpha-actin expression. Circ Res 101: 883–892, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gridley T. Notch signaling in the vasculature. Curr Top Dev Biol 92: 277–309, 2010. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92009-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grieskamp T, Rudat C, Lüdtke TH, Norden J, Kispert A. Notch signaling regulates smooth muscle differentiation of epicardium-derived cells. Circ Res 108: 813–823, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guilluy C, Brégeon J, Toumaniantz G, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Retailleau K, Loufrani L, Henrion D, Scalbert E, Bril A, Torres RM, Offermanns S, Pacaud P, Loirand G. The Rho exchange factor Arhgef1 mediates the effects of angiotensin II on vascular tone and blood pressure. Nat Med 16: 183–190, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nm.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta M, Kogut P, Davis FJ, Belaguli NS, Schwartz RJ, Gupta MP. Physical interaction between the MADS box of serum response factor and the TEA/ATTS DNA-binding domain of transcription enhancer factor-1. J Biol Chem 276: 10413–10422, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, Garber M, Grenier JK, Munson G, Young G, Lucas AB, Ach R, Bruhn L, Yang X, Amit I, Meissner A, Regev A, Rinn JL, Root DE, Lander ES. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature 477: 295–300, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto J, Ito S. Some mechanical aspects of arterial aging: physiological overview based on pulse wave analysis. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 3: 367–378, 2009. doi: 10.1177/1753944709338942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He A, Kong SW, Ma Q, Pu WT. Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5632–5637, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.High FA, Zhang M, Proweller A, Tu L, Parmacek MS, Pear WS, Epstein JA. An essential role for Notch in neural crest during cardiovascular development and smooth muscle differentiation. J Clin Invest 117: 353–363, 2007. doi: 10.1172/JCI30070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Q, Lin X, Ding L, Zeng Y, Pang D, Ouyang N, Xiang Y, Yao H. ARHGAP42 promotes cell migration and invasion involving PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Med 7: 3862–3874, 2018. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin Y, Messmer-Blust AF, Li J. The role of transcription enhancer factors in cardiovascular biology. Trends Cardiovasc Med 21: 1–5, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karasseva N, Tsika G, Ji J, Zhang A, Mao X, Tsika R. Transcription enhancer factor 1 binds multiple muscle MEF2 and A/T-rich elements during fast-to-slow skeletal muscle fiber type transitions. Mol Cell Biol 23: 5143–5164, 2003. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5143-5164.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim T, Hwang D, Lee D, Kim JH, Kim SY, Lim DS. MRTF potentiates TEAD-YAP transcriptional activity causing metastasis. EMBO J 36: 520–535, 2017. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurpinski K, Lam H, Chu J, Wang A, Kim A, Tsay E, Agrawal S, Schaffer DV, Li S. Transforming growth factor-beta and notch signaling mediate stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells. Stem Cells 28: 734–742, 2010. doi: 10.1002/stem.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F, Wang X, Hu G, Wang Y, Zhou J. The transcription factor TEAD1 represses smooth muscle-specific gene expression by abolishing myocardin function. J Biol Chem 289: 3308–3316, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.515817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loirand G, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Pacaud P. RhoA and resistance artery remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1051–H1056, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00710.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luft FC. Molecular mechanisms of arterial stiffness: new insights. J Am Soc Hypertens 6: 436–438, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack CP, Owens GK. Regulation of smooth muscle alpha-actin expression in vivo is dependent on CArG elements within the 5′ and first intron promoter regions. Circ Res 84: 852–861, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.84.7.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mack CP. Signaling mechanisms that regulate smooth muscle cell differentiation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 1495–1505, 2011. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manderfield LJ, Aghajanian H, Engleka KA, Lim LY, Liu F, Jain R, Li L, Olson EN, Epstein JA. Hippo signaling is required for Notch-dependent smooth muscle differentiation of neural crest. Development 142: 2962–2971, 2015. doi: 10.1242/dev.125807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miranda MZ, Bialik JF, Speight P, Dan Q, Yeung T, Szászi K, Pedersen SF, Kapus A. TGF-β1 regulates the expression and transcriptional activity of TAZ protein via a Smad3-independent, myocardin-related transcription factor-mediated mechanism. J Biol Chem 292: 14902–14920, 2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.780502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; Writing Group Members; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Executive Summary: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2016 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133: 447–454, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pintérová M, Kuneš J, Zicha J. Altered neural and vascular mechanisms in hypertension. Physiol Res 60: 381–402, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rayon T, Menchero S, Nieto A, Xenopoulos P, Crespo M, Cockburn K, Cañon S, Sasaki H, Hadjantonakis AK, de la Pompa JL, Rossant J, Manzanares M. Notch and hippo converge on Cdx2 to specify the trophectoderm lineage in the mouse blastocyst. Dev Cell 30: 410–422, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renna NF, de Las Heras N, Miatello RM. Pathophysiology of vascular remodeling in hypertension. Int J Hypertens 2013: 808353, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozenberg JM, Tesfu DB, Musunuri S, Taylor JM, Mack CP. DNA methylation of a GC repressor element in the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain promoter facilitates binding of the Notch-associated transcription factor, RBPJ/CSL1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 2624–2631, 2014. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rozenberg JM, Taylor JM, Mack CP. RBPJ binds to consensus and methylated cis elements within phased nucleosomes and controls gene expression in human aortic smooth muscle cells in cooperation with SRF. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 8232-8244, 2018. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sehgel NL, Zhu Y, Sun Z, Trzeciakowski JP, Hong Z, Hunter WC, Vatner DE, Meininger GA, Vatner SF. Increased vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness: a novel mechanism for aortic stiffness in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H1281–H1287, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00232.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction through the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway in smooth muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 25: 613–615, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speight P, Kofler M, Szászi K, Kapus A. Context-dependent switch in chemo/mechanotransduction via multilevel crosstalk among cytoskeleton-regulated MRTF and TAZ and TGFβ-regulated Smad3. Nat Commun 7: 11642, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swartz EA, Johnson AD, Owens GK. Two MCAT elements of the SM alpha-actin promoter function differentially in SM vs. non-SM cells. Am J Physiol 275: C608–C618, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang Y, Urs S, Liaw L. Hairy-related transcription factors inhibit Notch-induced smooth muscle alpha-actin expression by interfering with Notch intracellular domain/CBF-1 complex interaction with the CBF-1-binding site. Circ Res 102: 661–668, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang Y, Urs S, Boucher J, Bernaiche T, Venkatesh D, Spicer DB, Vary CP, Liaw L. Notch and transforming growth factor-beta (TGFbeta) signaling pathways cooperatively regulate vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 285: 17556–17563, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wackerhage H, Del Re DP, Judson RN, Sudol M, Sadoshima J. The Hippo signal transduction network in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Sci Signal 7: re4, 2014. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wain LV, Verwoert GC, O’Reilly PF, Shi G, Johnson T, Johnson AD, Bochud M, Rice KM, Henneman P, Smith AV, Ehret GB, Amin N, Larson MG, Mooser V, Hadley D, Dörr M, Bis JC, Aspelund T, Esko T, Janssens AC, Zhao JH, Heath S, Laan M, Fu J, Pistis G, Luan J, Arora P, Lucas G, Pirastu N, Pichler I, Jackson AU, Webster RJ, Zhang F, Peden JF, Schmidt H, Tanaka T, Campbell H, Igl W, Milaneschi Y, Hottenga JJ, Vitart V, Chasman DI, Trompet S, Bragg-Gresham JL, Alizadeh BZ, Chambers JC, Guo X, Lehtimäki T, Kühnel B, Lopez LM, Polašek O, Boban M, Nelson CP, Morrison AC, Pihur V, Ganesh SK, Hofman A, Kundu S, Mattace-Raso FU, Rivadeneira F, Sijbrands EJ, Uitterlinden AG, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS, Wang TJ, Bergmann S, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Laitinen J, Pouta A, Zitting P, McArdle WL, Kroemer HK, Völker U, Völzke H, Glazer NL, Taylor KD, Harris TB, Alavere H, Haller T, Keis A, Tammesoo ML, Aulchenko Y, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Galan P, Hercberg S, Lathrop M, Eyheramendy S, Org E, Sõber S, Lu X, Nolte IM, Penninx BW, Corre T, Masciullo C, Sala C, Groop L, Voight BF, Melander O, O’Donnell CJ, Salomaa V, d’Adamo AP, Fabretto A, Faletra F, Ulivi S, Del Greco F, Facheris M, Collins FS, Bergman RN, Beilby JP, Hung J, Musk AW, Mangino M, Shin SY, Soranzo N, Watkins H, Goel A, Hamsten A, Gider P, Loitfelder M, Zeginigg M, Hernandez D, Najjar SS, Navarro P, Wild SH, Corsi AM, Singleton A, de Geus EJ, Willemsen G, Parker AN, Rose LM, Buckley B, Stott D, Orru M, Uda M, van der Klauw MM, Zhang W, Li X, Scott J, Chen YD, Burke GL, Kähönen M, Viikari J, Döring A, Meitinger T, Davies G, Starr JM, Emilsson V, Plump A, Lindeman JH, Hoen PA, König IR, Felix JF, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Ongen H, Breteler M, Debette S, Destefano AL, Fornage M, Mitchell GF, Smith NL, Holm H, Stefansson K, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Samani NJ, Preuss M, Rudan I, Hayward C, Deary IJ, Wichmann CO, Raitakari OT, Palmas W, Kooner JS, Stolk RP, Jukema JW, Wright AF, Boomsma DI, Bandinelli S, Gyllensten UB, Wilson JF, Ferrucci L, Schmidt R, Farrall M, Spector TD, Palmer LJ, Tuomilehto J, Pfeufer A, Gasparini P, Siscovick D, Altshuler D, Loos RJ, Toniolo D, Snieder H, Gieger C, Meneton P, Wareham NJ, Oostra BA, Metspalu A, Launer L, Rettig R, Strachan DP, Beckmann JS, Witteman JC, Erdmann J, van Dijk KW, Boerwinkle E, Boehnke M, Ridker PM, Jarvelin MR, Chakravarti A, Abecasis GR, Gudnason V, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Munroe PB, Psaty BM, Caulfield MJ, Rao DC, Tobin MD, Elliott P, van Duijn CM; LifeLines Cohort StudyEchoGen consortiumAortaGen ConsortiumCHARGE Consortium Heart Failure Working GroupKidneyGen consortiumCKDGen consortiumCardiogenics consortium; CardioGram . Genome-wide association study identifies six new loci influencing pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure. Nat Genet 43: 1005–1011, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ng.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wirth A, Benyó Z, Lukasova M, Leutgeb B, Wettschureck N, Gorbey S, Orsy P, Horváth B, Maser-Gluth C, Greiner E, Lemmer B, Schütz G, Gutkind JS, Offermanns S. G12-G13-LARG-mediated signaling in vascular smooth muscle is required for salt-induced hypertension. Nat Med 14: 64–68, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Q, Jia C, Wang P, Xiong M, Cui J, Li L, Wang W, Wu Q, Chen Y, Zhang T. MicroRNA-505 identified from patients with essential hypertension impairs endothelial cell migration and tube formation. Int J Cardiol 177: 925–934, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]