Abstract

The cardiac potassium IKs current is carried by a channel complex formed from α-subunits encoded by KCNQ1 and β-subunits encoded by KCNE1. Deleterious mutations in either gene are associated with hereditary long QT syndrome. Interactions between the transmembrane domains of the α- and β-subunits determine the activation kinetics of IKs. A physical and functional interaction between COOH termini of the proteins has also been identified that impacts deactivation rate and voltage dependence of activation. We sought to explore the specific physical interactions between the COOH termini of the subunits that confer such control. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange coupled to mass spectrometry narrowed down the region of interaction to KCNQ1 residues 352–374 and KCNE1 residues 70–81, and provided evidence of secondary structure within these segments. Key mutations of residues in these regions tended to shift voltage dependence of activation toward more depolarizing voltages. Double-mutant cycle analysis then revealed energetic coupling between KCNQ1-I368 and KCNE1-D76 during channel activation. Our results suggest that the proximal COOH-terminal regions of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 participate in a physical and functional interaction during channel opening that is sensitive to perturbation and may explain the clustering of long QT mutations in the region.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Interacting ion channel subunits KCNQ1 and KCNE1 have received intense investigation due to their critical importance to human cardiovascular health. This work uses physical (hydrogen/deuterium exchange with mass spectrometry) and functional (double-mutant cycle analyses) studies to elucidate precise and important areas of interaction between the two proteins in an area that has eluded structural definition of the complex. It highlights the importance of pathogenic mutations in these regions.

Keywords: IKs current, long QT syndrome, KCNQ1-KCNE1 interactions

INTRODUCTION

The cardiac slowly activating delayed rectifier current IKs is carried by the channel complex formed from two gene products: KCNQ1, encoding the pore-forming α-subunits, and KCNE1, encoding the regulatory β-subunits. Many mutations found in these genes may perturb channel function such that outward potassium current is reduced, delaying repolarization and prolonging the cardiac action potential. This delay in repolarization can be detected on an electrocardiogram as a prolonged QT interval; hence, pathophysiological sequelae of loss-of-function mutations to this channel are grouped under the umbrella term of long QT syndrome (LQTS), where patients have an increased susceptibility to arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.

While the KCNQ1 α-subunits form functional channels by themselves in vitro, that current is not found endogenously in the heart. KCNE1 is necessary to transform the KCNQ1 current into cardiac IKs, which has increased current density with much slower activation and deactivation. The KCNQ1 subunits have a predicted structure like that of other voltage-gated potassium channels: six transmembrane domains (S1–S6) with intracellular NH2 and COOH termini, a voltage sensor formed by positively charged residues in S4, and a pore loop between S5 and S6 that lines the conduction pathway and confers potassium selectivity. KCNE1 has a single α-helical transmembrane domain with extracellular NH2 terminus and intracellular COOH terminus and associates with KCNQ1 with variable stoichiometry (26, 28). The placement of KCNE1 within the channel complex has been probed in several ways. A direct physical interaction between the transmembrane domain of KCNE1 and the S6 domain of KCNQ1 has been identified (1, 25, 30, 37), and contact between a single residue from each subunit in large part controls the activation kinetics of IKs (24). Cysteine mutagenesis and resultant disulfide bond formation experiments place the external portion of KCNE1 in close proximity to the S1 and S4 domains of neighboring KCNQ1 subunits (5, 45). Together, these results suggest a tilted traverse of KCNE1 through the membrane and multiple points of contact with KCNQ1 within the channel.

Several groups have examined the interaction between the intracellular domains of KCNQ1 and KCNE. Sachyani et al. (33) have provided a crystal structure of the KCNQ1 COOH terminus that indicates residues 352 through 385 are α-helical (forming the A-helix) and comprise part of a calmodulin-binding site. We still lack, however, 3-dimensional structures for the two subunits in the complex. The transmembrane portion of KCNQ1 has been modeled onto the crystal structure of Kv1.2 (35), and an NMR structure of KCNE1 has allowed for in silico docking experiments that approximate their relative positions in the channel complex (13). Functional studies indicate the importance of the COOH-terminal regions: truncation of the KCNE1 COOH terminus shifts voltage-dependent activation and reduces association of KCNE1 with KCNQ1 (3). The KCNE1 COOH terminus is also able to physically bind to the KCNQ1 COOH terminus, specifically to the proximal third of the domain (3, 6, 9, 50), and proximity of these regions has additionally been reconfirmed by cysteine mutagenesis studies (21). Several naturally occurring LQTS mutations are located in these regions, further supporting their functional significance. Here, we report our investigations further exploring the region of functional interaction and identification of direct interacting pairs of residues between the KCNQ1 and KCNE1 proximal COOH termini.

We used hydrogen/deuterium exchange coupled to mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), a technique that offers the advantage of not being reliant on mutagenesis-based data but by unbiased mutual protection from deuterium exchange of interacting proteins. We narrowed down to KCNE1 residues 70–75 and KCNQ1 residues 352–374 as regions that physically interacted. Targeted double-mutant cycle analysis (DMCA) of residues in these regions identified an interaction between KCNQ1-P369 and KCNE1-S74 during the channel closed-to-open transition and a weaker interaction between KCNQ1-I368 and KCNE1-H73 during the open-to-closed transition. These data help to define the physical and functional interaction sites of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 in the proximal COOH terminus, an area of increasingly complex regulatory activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression, and purification of KCNQ1-C1 and KCNE1-CT.

Construction of the KCNQ1-C1 (KCNQ1 residues 349–480) and KCNE1-CT (KCNE1 residues 67–129) expression plasmids and expression and purification of the proteins have been previously described (50). Briefly, for KCNQ1-C1, the DNA fragment obtained from PCR amplification of human KCNQ1 genes was cloned into the pMAL-C2 vector (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), which includes the maltose-binding protein (MBP) tag, and expressed in the Escherrichia coli strain BL21(DE3) pLysS (Promega, Madison, WI) grown at 37°C to a OD500 of 0.5 in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing appropriate antibiotics, inducing with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and incubating for an additional 6–8 h at 25°C. For purification, cells (~10 g) were resuspended and lysed by sonication in MBP buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethernol, complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), 100 μg/mL DNAseI]. After centrifugation, the supernatant was run through an amylose column (New England BioLabs), and bound MBP-KCNQ1-C1 was eluted with MBP buffer containing 10 mM maltose. The eluate was applied onto a 1.6 cm × 70 cm Superdex 200 gel filtration column, and the proteins were eluted with HEPES buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.8),150 mM NaCl, 5 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol] at 0.5 mL/min. Fractions containing the protein were identified by ultraviolet spectrum and were pooled and concentrated.

For KCNE1-CT, the DNA fragment obtained from PCR amplification of human KCNE1 genes was cloned into the pET23a(+) vector (EMD Chemicals, Darmstadt, Germany), which includes the His6 tag, and expressed in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3) pLysS grown identically to KCNQ1-C1 up through induction with IPTG and then incubated for an additional 16–18 h at 17°C. The purification procedure was the same as for KCNQ1 fragments but with the following modifications. His-buffer for resuspension/lysis contained 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethernol, complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and 100 μg/mL DNAseI. A Ni-NTA His-Bind affinity column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used for purification, and proteins were eluted with 200 mM imidazole in His-buffer. From the gel filtration column, proteins were eluted with the His-buffer.

HDX-MS.

Purified KCNQ1-C1 and KCNE1-CT at a starting concentration of 1 mg/mL were used for the HDX-MS experiments. Phosphate buffer [20 mM KPO4, 130 mM KCl (pH 6.2)] was used for all experiments, which were conducted on ice. Initially, the proteins were subjected to enzymatic digestion to determine sequence coverage of the proteolytic peptides (mapping studies). Each sample was diluted 20-fold in phosphate buffer and then digested with equimolar pepsin in 0.01 N HCl (pH 2.1) for 5 min, followed by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) analysis (detailed in the next section).

To determine baseline deuterium exchange, each protein was diluted 10-fold in deuterated phosphate buffer, and exchange was allowed to proceed for 60 s. The reaction was quenched with an equal volume of ice-cold citric acid buffer (0.5 M, pH 2.2) and subjected to pepsin digestion as above. (The 10-fold dilution with equal-volume quenching yields a final 20-fold dilution, equivalent to the dilution used in the original mapping studies.) To determine the effects of protein-protein interaction, KCNQ1-C1 and KCNE1-CT were premixed for 1 h in a 1:3 ratio to ensure full saturation of the interaction (Experiments with KCNQ1 saturating KCNE1 were carried out separately from experiments with KCNE1 saturating KCNQ1.). Deuterium exchange proceeded as above, and the quenched samples were subjected to immediate LC-ESI-MS analysis.

HDX LC-ESI-MS and peptide identification.

A Shimadzu HPLC, with two LC-10AD pumps, was used to generate a fast gradient with a 50 μL/min flow rate, optimized for best sequence coverage. Solvent A was 5% acetonitrile (Fisher) in H2O, 0.2% formic acid (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid (Pierce); solvent B consisted of 95% acetonitrile in H2O, 0.2% formic acid, and 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid. All components of the setup, including tubing, injector, and column, were submerged in an ice bath at all times to reduce back exchange.

For analysis of proteolytic peptides, 200 μL of chilled digest was injected onto a 1.0-mm ID × 50 mm C8 column (Waters, Milford, MA). After 5-min desalting with 2% solvent B, the peptides were eluted at 30 μL/min with a 2−15% gradient for 1 min, 15−30% for 9 min, 30−50% for 1 min, and 50−95% for 1 min. The effluent was infused into a 12 T Varian IonSpec FT-ICR MS (Varian, Inc., Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The extent of deuterium incorporation of each peptic peptide was determined by FT-ICR-MS from the centroid mass difference between deuterated and nondeuterated samples (49).

HDX-MS data analysis.

Average changes in deuterium incorporation (ΔHDX) ± SE of all peptides of both proteins were determined from three separate experiments, each of noninteracting and interacting cases. The mass spectrometry distribution for all peptides was fitted to a Gaussian curve using OriginLab to determine the centroid mass of each peptide, which was the value used for determining ΔHDX. Significance was determined based on a two-tailed t-test. Based on a combination of instrument accuracy and precision of data analysis, the significance was set at P < 0.05. Thus, any change in deuterium incorporation with P < 0.05 was considered significant even if the absolute average value for ΔHDX was below 0.5. This method of analysis has been previously used by other groups (15, 16).

Plasmids and cell culture.

Construction and validation of Myc-KCNQ1 and 3X-FLAG-KCNE1 expression plasmids have been previously described (17, 25). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to create the KCNQ1 and KCNE1 COOH-terminal point mutations, with products confirmed by sequencing.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and 10,000 IU penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transient transfections were performed using Fugene 6 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Molar ratios of 1:4:0.33 of KCNQ1/KCNE1/green fluorescent protein (GFP) plasmid were used to ensure fully saturated IKs current and to allow identification of transfected cells by fluorescence. Electrophysiology studies were performed 48 h after transfection.

Electrophysiology.

Transfected HEK-293 cells were grown on sterile glass coverslips and placed in an acrylic-polystyrene perfusion chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) mounted in an inverted microscope outfitted with fluorescence optics and patch pipette micromanipulators. Extracellular solution consisted of (in mM) 140 NaCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 glucose, and 10 HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature (20–22°C). Intracellular pipette solution contained (in mM) 126 KCl, 4 K-ATP, 1 MgSO4, 5 EGTA, 0.5 CaCl2, and 25 HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) at room temperature. The whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique was used to measure potassium currents (10). A MultiClamp 700B patch-clamp amplifier was used, and protocols were controlled via PC using pCLAMP10 acquisition and analysis software (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Patch-clamp pipettes were manufactured, and tips were polished to obtain a resistance of 2–3 MΩ in the test solutions. The pipette offset potential in these solutions was corrected to zero just before seal formation. The junction potential for these solutions was calculated between 3 and 4 mV (by pClamp analysis software) and was not corrected for analyses. Whole cell capacitance (generally 10–25 pF) was compensated electronically through the amplifier. Whole cell series resistance of 6–12 MΩ was compensated to 75–90% using amplifier circuitry such that the voltage errors for currents of 2 nA were always less than 6 mV. A standard holding potential was −90 mV, and figure insets show applied voltage protocols. Data were filtered using an eight-pole Bessel filter at 1 kHz, with a sampling rate of 4 kHz for the activation protocol.

DMCA.

To investigate specific sites of interaction with a functional consequence between KCNQ1 and KCNE1 in the areas identified by HDX-MS we employed DMCA to measure coupling energies between the two proteins (11). DMCA has been employed in numerous ion channel studies to probe specific sites of intra- and intersubunit interactions (29, 31). Wild-type (WT) KCNQ1 and KCNE1 were analyzed using activation protocols, along with the four KCNQ1 and three KCNE1 single mutations, and 12 double-mutant pairs. To calculate the macroscopic conductance-voltage relationship, normalized tail currents were plotted against the test voltage and fitted with single a Boltzmann function according to Eq. 1:

| (1) |

In Eq. 1, I/Imax is the normalized tail current, V is the applied test voltage, Vh is the voltage at which one-half of the maximal activation occurs and k is the slope factor. A1 and A2 are the upper and lower asymptotes, which were left to vary, as the channels do not fully activate in the tested voltage range. The slope factor k can also be defined by the following equation:

| (2) |

In Eq. 2, R is the ideal gas constant (1.99 cal/mol), T is the absolute temperature (298 K), zg is the apparent gating valence, and F is Faraday’s constant (23,061 cal/mol). The Gibbs free energy of activation, ΔG, was calculated using the Vh and slope factor according to Eq. 3:

| (3) |

Combining Eqs. 2 and 3, we derive Eq. 4:

| (4) |

The change in ΔG (ΔΔG) caused by each mutation was calculated as

| (5) |

The ΔΔG of coupling of single mutants mut1 and mut2, and double-mutants mut1–2, were calculated by the equation

| (6) |

ΔΔGcoupling may be positive or negative depending on the direction of the energetic perturbation of a mutation. For comparisons, ΔΔGcoupling is commonly expressed in absolute values of kilocalories per mole (11). Standard errors were calculated using linear error propagation.

RESULTS

HDX-MS identifies a physical interaction between proximal COOH termini of KCNQ1 and KCNE1.

HDX-MS may be used to identify receptor-ligand binding interfaces, protein conformation changes, and protein-protein interactions. It relies on the monitoring of exchange of the amide hydrogen of the peptide backbone with deuterium, which depends on the solvent accessibility of each individual residue. Protein folding and protein-protein interaction can reduce the solvent accessibility at specific residues, thereby protecting them from deuterium exchange.

To establish a baseline structure-dependent solvent accessibility pattern, KCNQ1 and KCNE1 were separately subjected to HDX-MS. Initial peptide mapping was performed on undeuterated proteins with pepsin digestion followed by LC-ESI-MS, which yielded seven peptides with 87.3% sequence coverage for KCNE1-CT and seven peptides with 92.4% sequence coverage for KCNQ1-C1. All of these peptides were recovered under deuterium exchange conditions.

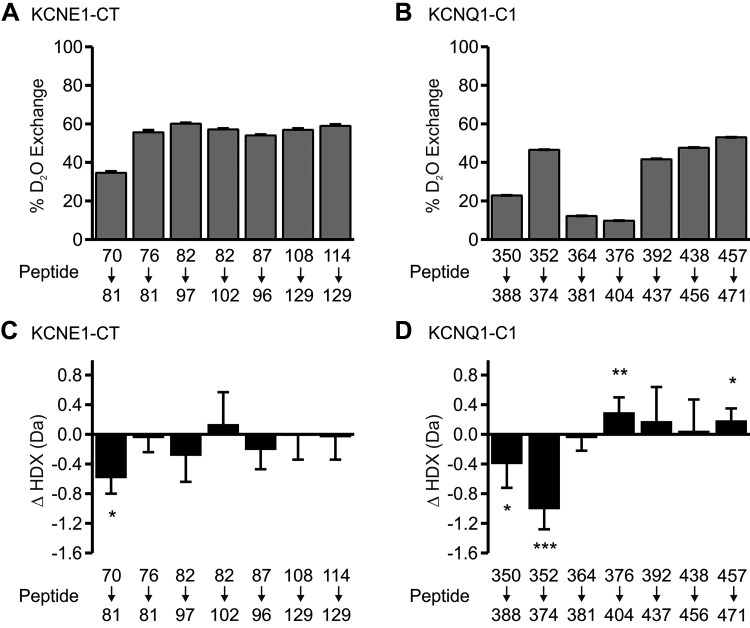

The extent of deuterium exchange for each peptide was calculated as the centroid mass difference between deuterated and nondeuterated peptides divided by the maximum number of deuterium exchange possible (the number of peptide bonds in the peptide minus the number of proline residues). This fraction was expressed as a percentage in Fig. 1A for KCNE1-CT peptides, and in Fig. 1B for KCNQ1-C1 peptides. The rate of deuterium incorporation yields structural implications. In a completely unstructured peptide, the amide hydrogens are free and completely solvent accessible. In such an ideal case, full exchange is expected, and any deviation is attributed to the inevitable back-exchange that occurs in the analysis. Even simple secondary structure, though, such as an α-helix, will reduce the exchange rate, because the amide hydrogens are participating in hydrogen bonding and will exchange more slowly than free amide hydrogen. Any form of tertiary or quaternary structure, as well as protein-protein interactions, will further protect residues and slow the exchange rate. For KCNE1-CT, six of the seven peptides exhibit ~60% deuterium exchange, while the most proximal (NH2-terminal) segment (residues 70–81) has reduced exchange compared with the others (Fig. 1A). Because the two proximal peptides overlap (70–81 and 76–81), we can infer that the reduction in deuterium exchange is occurring mostly in the range of residues 70–75. For KCNQ1-C1, four of the seven peptides exhibit exchange rates from ~40% to 55% (residues 352–374, 392–437, and 457–471), while three peptides exhibited rates from ~10% to 20% (residues 350–388, 364–381, and 376–404) (Fig. 1B). Again, because of peptide overlap, we can infer that the location of highest secondary structure is likely between residues 364 and 391.

Fig. 1.

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange with mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) of KCNE1-CT (residues 67–129; A) and KCNQ1-C1 (residues 349–480; B). The x-axis is labeled with the residue ranges of peptides obtained by enzymatic digestion; the y-axis indicates percent deuterium exchange, which is calculated as the difference between deuterated and undeuterated mass divided by the maximum deuterium exchange possible, multiplied by 100. C and D: change in amount of deuterium incorporated when KCNE1-CT (C) and KCNQ1-C1 (D) deuterated alone compared with being in the presence of the other protein. Data indicate means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

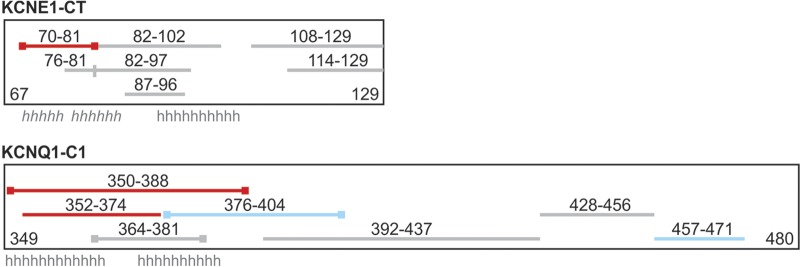

To examine the effects of protein-protein interaction on deuterium exchange, each protein was first saturated with the other before being subjected to deuterium exchange, quenching, and LC-ESI-MS analysis. Any difference in deuterium exchange was calculated as the difference in mass of each peptide alone and with interaction with the partner protein. The change in HDX (ΔHDX) for KCNE1-CT peptides and KCNQ1-C1 peptides are graphed in Fig. 1, C and D. A negative ΔHDX indicates that, with the interacting partner present, the peptide had reduced deuterium exchange because it was protected from solvent. A positive ΔHDX indicates that a peptide was deprotected such that an increase in deuterium exchange occurred. For KCNE1-CT, the most proximal peptide (residues 70–81) showed significant decrease in HDX, whereas the overlapping peptide 76–81 did not, indicating that protection was most likely centered about residues 70–75. None of the remaining peptides were significantly changed. For KCNQ1-C1, the most proximal peptides, particularly residues 352–374, showed significant protection. Together with the data from KCNE1-CT, we conclude that the most proximal segments of the KCNE1 and KCNQ1 COOH termini physically interact. The KCNQ1-C1 peptides also reveal two more COOH-terminal KCNQ1 segments that are deprotected after interaction with KCNE1-CT: residues 376–404 and residues 457–471. This suggests that, upon binding with KCNE1-CT, a conformational change occurs that leaves these residues more exposed to solvent. Figure 2 summarizes all of the HDX-MS experimental findings in a schematic diagram of the KCNE1-CT and KCNQ1-C1 proteins and proteolytic peptides. The schematics also indicate the location of predicted α-helices [based on sequence analysis for KCNQ1 and periodicity analysis of alanine/tryptophan mutations for KCNE1 (32)], which roughly correspond to the regions of reduced deuterium exchange identified in Fig. 1, A and B.

Fig. 2.

Summary diagram hydrogen-deuterium exchange with mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) experiments. Rectangular boxes represent full-length protein drawn roughly to scale according to number of amino acids, with residue range marked at the bottom corners. Lines inside represent lengths of digested peptides, with residues labeled above each. Lines with square ends are peptides that had lower than average deuterium incorporation. Red lines indicate peptides with negative change in HDX, blue lines peptides with positive change in HDX. Roman “h” indicates location of predicted α-helices; italic “h” indicates prediction by periodicity analysis (32); roman “h” indicates sequence-based prediction, and for KCNE1, NMR structure (13).

KCNQ1 and KCNE1 proximal COOH-terminal mutations.

To further investigate interactions in the KCNE1 (E1) and KCNQ1 (Q1) proximal COOH termini, we turned to double-mutant cycle analysis. Because the regions identified by HDX were still rather large (particularly the KCNQ1 segment), complete analysis of every single possible double-mutant combination was prohibitive, as it would have involved analysis of nearly 200 single- and double-mutant pairings. We chose residues to analyze on the basis of several factors: residues that have been identified with LQTS-associated mutations, and residues that were identified as being in close proximity by cysteine mutagenesis and disulfide bond formation analysis (21). Based on these criteria, the residues chosen were for E1 H73, S74, and D76 and for Q1 K362, H363, I368, and P369. The mutations made were either known disease-associated mutations (E1, S74L and D76N; Q1, H363N) or were designed to perturb the side-chain physical characteristics of charge, mass, or hydrophobicity (E1, H73D; Q1, K362E, I368S, and P369S).

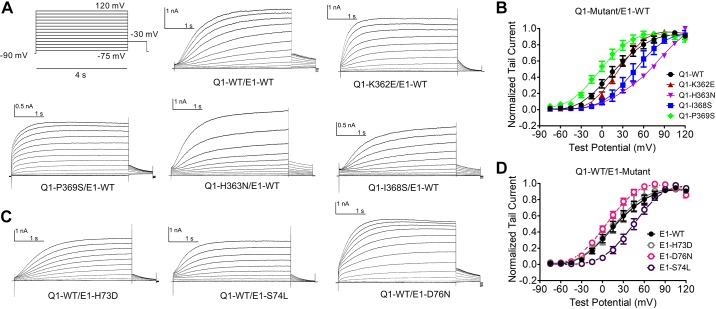

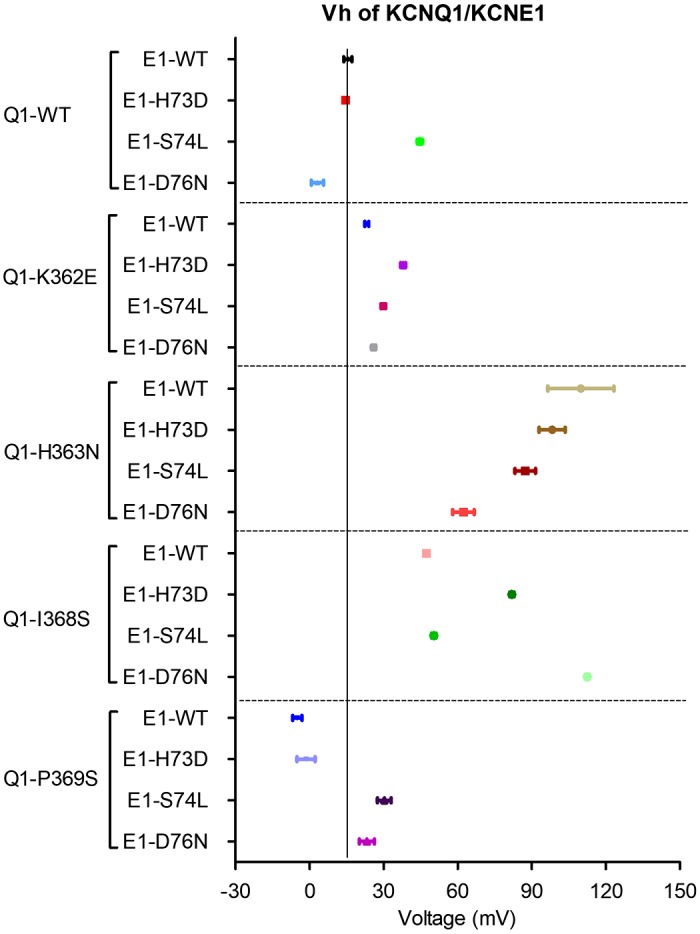

The single mutations were characterized and compared with the Q1/E1 WT pair. Voltage-dependent activation curves were plotted for the four Q1 mutations paired with WT E1 (Fig. 3, A and B) and for the three E1 mutations paired with WT Q1 (Fig. 3, C and D). The double-WT Q1-E1 pairing is also included for comparison. To ascertain that KCNQ1 mutations did not result in nonfunctional channels, which would have rendered them unusable for DMCA, we expressed each in the absence of KCNE1 and performed current measurements. Each KCNQ1 mutant subunit produced robust voltage-gated K+ currents with comparable voltage dependence of activation (VDA; Supplemental Fig. S1 and Supplemental Table S1; all supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10859258.v1). The mutant channel subunit pairs produced IKs-like currents with slow, sigmoidal shaped activation except for Q1-P369S. VDA was expressed as Vh, the voltage at which one-half of the channels are activated. Q1-P369S paired with E1-WT produced more rapidly activating K+ conductance with a significantly hyperpolarized shift in VDA (−20.5 mV relative to Q1-WT/E1-WT). Compared with Q1-WT/E1-WT channels, that have a Vh of 15.51 mV, the other Q1 mutants expressed with E1-WT exhibit a depolarizing shift in the VDA between 7.65 and 94.34 mV relative to Q1-WT/E-1WT (Table 1). Channels comprised of Q1-WT/E1-H73D behaved nearly the same as Q1-WT/E1-WT. The other two E1-mutant parings with Q1-WT shifted the VDA in either depolarizing (Q1-WT/E1-S74L, 29.12mV relative to WT) or hyperpolarizing direction (Q1-WT/E1-D76, −12.33 mV relative to WT). Summary Vh and slope factor constant measurements for all single and double-mutant pairs can be found in Table 1. Given that all of the mutant subunits produced varying degrees of perturbation of the VDA, they were judged fit for use in DMCA.

Fig. 3.

Effects of single COOH-terminal mutations of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 on voltage-dependent activation (VDA). A: whole cell current traces of KCNQ1 mutants with wild-type KCNE1 (KCNE1-WT) in response to a series of depolarizing voltage steps (voltage clamp protocol shown above). B: normalized VDA curves of cardiac potassium current (IKs) carried by KCNQ1 mutant (-Mut) and KCNE1-WT. C: whole cell current traces of KCNQ1-WT with KCNE1 mutants. D: normalized VDA curves of IKs carried by KCNQ1-WT and KCNE1-Mut. All mutations are significantly left or right shifted (P < 0.05) except KCNQ1-WT/KCNE1-H73D. See Table 1 for all Vh (voltage at which half of maximal activation occurs) values and n values.

Table 1.

Parameters of activation

| Vh, mV | Slope Factor | ΔΔG, kcal/mol | ︱ΔΔGc︱, kcal/mol | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1-WT/E1-WT | 15.51 ± 1.63 | 22.59 ± 1.62 | 11 | ||

| Single mutants | |||||

| Q1-K362E/E1-WT | 23.16 ± 0.82 | 15.36 ± 0.74 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 10 | |

| Q1-H363N/E1-WT | 109.85 ± 13.39 | 43.04 ± 4.7 | 1.11 ± 0.18 | 13 | |

| Q1-I368S/E1-WT | 47.24 ± 0.89 | 20.67 ± 0.81 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 6 | |

| Q1-P369S/E1-WT | −4.99 ± 1.89 | 17.55 ± 1.69 | −0.58 ± 0.06 | 8 | |

| Q1-WT/E1-H73D | 14.58 ± 0.98 | 20.7 ± 0.95 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 7 | |

| Q1-WT/E1-S74L | 44.63 ± 1.00 | 18.53 ± 0.91 | 1.02 ± 0.03 | 10 | |

| Q1-WT/E1-D76N | 3.18 ± 2.45 | 16.97 ± 2.23 | −0.30 ± 0.09 | 6 | |

| Double mutants | |||||

| Q1-K362E/E1-H73D | 37.89 ± 1.08 | 19.87 ± 1.02 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 9 |

| Q1-K362E/E1-S74L | 29.86 ± 0.95 | 16.99 ± 0.87 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 10 |

| Q1-K362E/E1-D76N | 25.9 ± 0.80 | 14.21 ± 0.72 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 8 |

| Q1-H363N/E1-H73D | 98.36 ± 3.91 | 35.81 ± 1.6 | 1.22 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.15 | 10 |

| Q1-H363N/E1-S74L | 87.32 ± 4.15 | 32.42 ± 2.07 | 1.19 ± 0.08 | 0.94 ± 0.15 | 11 |

| Q1-H363N/E1-D76N | 62.31 ± 4.32 | 33.5 ± 3.36 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.14 | 6 |

| Q1-I368S/E1-H73D | 81.94 ± 0.86 | 19.32 ± 0.56 | 2.11 ± 0.03 | 1.15 ± 0.03 | 7 |

| Q1-I368S/E1-S74L | 50.30 ± 0.90 | 25.00 ± 0.82 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 1.18 ± 0.03 | 9 |

| Q1-I368S/E1-D76N | 112.45 ± 0.87 | 24.51 ± 0.27 | 2.31 ± 0.02 | 1.66 ± 0.07 | 10 |

| Q1-P369S/E1-H73D | −1.43 ± 3.66 | 21.51 ± 3.37 | −0.45 ± 0.10 | 0.12 ± 0.09 | 7 |

| Q1-P369S/E1-S74L | 30.27 ± 2.75 | 30.91 ± 3.10 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 10 |

| Q1-P369S/E1-D76N | 23.18 ± 3.04 | 27.88 ± 3.32 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 6 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of experiments. KCNQ1 and KCNE1 single- and double-mutant analysis. For activation parameters, Vh and slope factor were calculated from Boltzmann fit of normalized tail currents. See methods for equations used in calculations. ΔΔG, difference in Gibbs free energy of activation (ΔG); ΔΔGc, ΔΔG coupling; WT, wild type; Vh, voltage at which half of maximal activation occurs.

DMCA identifies KCNQ1 I378 and KCNE1 D76 as an energetically coupled interaction site.

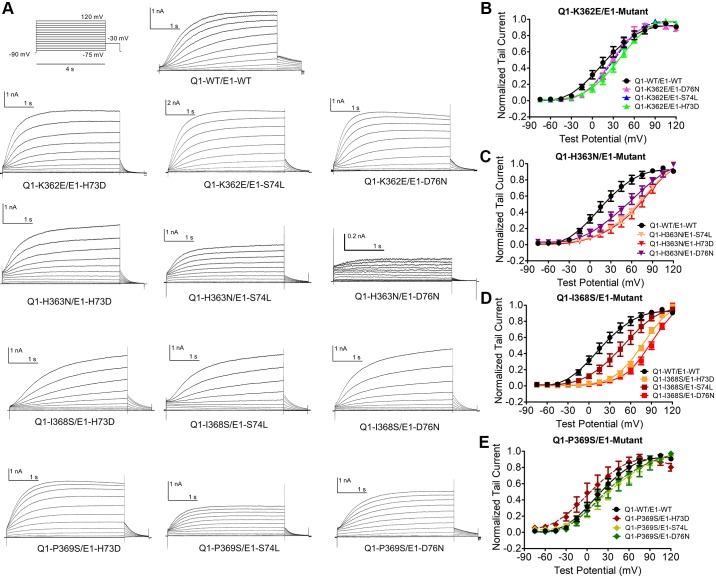

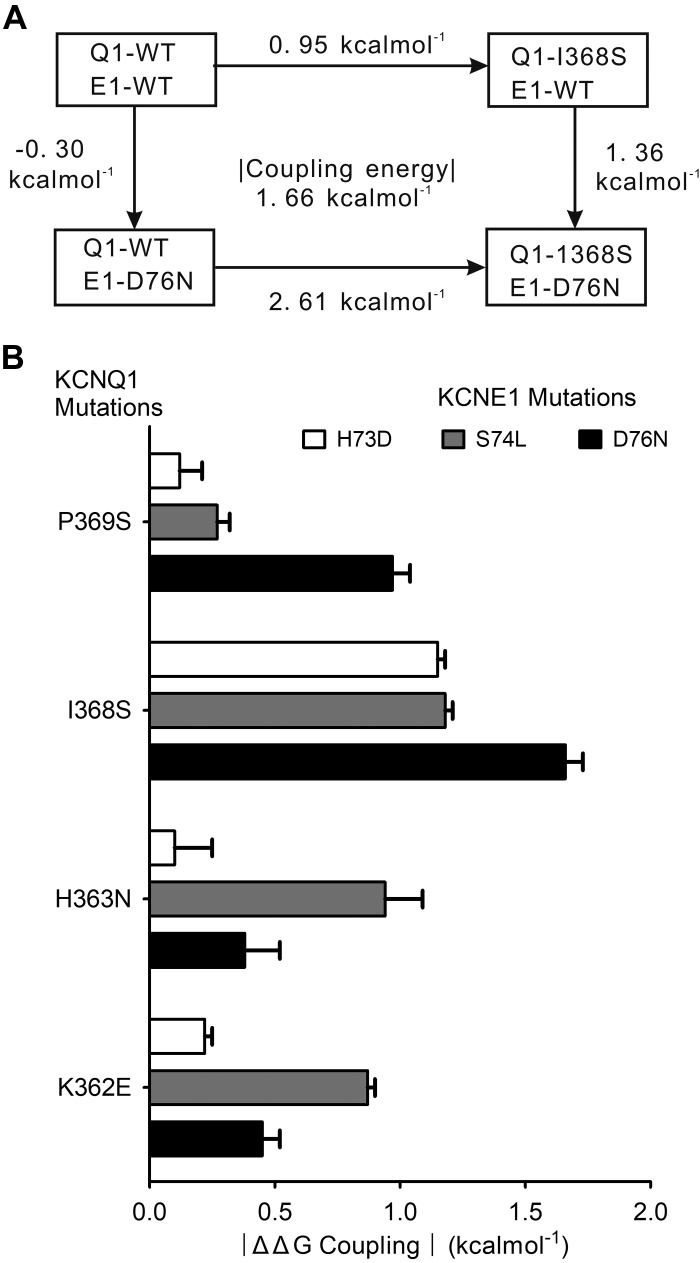

As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, DMCA was conducted on 12 double-mutant pairs and analyzed using the two parameters, the Vh and slope factor from the Boltzmann fit of VDA curves, to determine energetic coupling from the closed-to-open (C-O) transition. Q1-P369S/E1-H73D significantly left shifted VDA toward hyperpolarized voltages. Q1-H363N and Q1-I368S, when paired with any E1 mutant (E1-H73D, S74L, or D76N) significantly right shifted (depolarizing direction) VDA (Vh >50 mV). DMCA compares the change in ΔG (ΔΔG) from WT to mutant of two single mutations (one each in Q1 and E1) to the ΔΔG of the double-mutant pair. If the mutated residues do not interact, their effects should be additive, and the sum of their ΔΔG would equal the ΔΔG of the double-mutant, giving a ΔΔGcoupling of near 0 kcal/mol. If the residues do functionally interact, then their ΔΔG’s would not be additive, an indication of energetic coupling. There is no uniformly agreed on cutoff value for ΔΔGcoupling, but studies investigating ion channel subunit interactions have interpreted values ranging from 0.7 to 1.7 kal/mol as significant and indicating interaction (8, 19, 29, 31, 42). Accordingly, we set a ΔΔGcoupling value of 1.5 kcal/mol as indicative of strong interaction and values between 1.0 and 1.5 kcal/mol as suggesting weaker or transient interactions. The coupling energies based on activation were evaluated within their own group, as explained below. Figure 6A shows an exemplar mutant cycle analysis of the double-mutant pair Q1-I368S with E1-D76N, with the energetics calculations based on Vh and slope factor from the Boltzmann fit of the VDA curves. Figure 6B summarizes the coupling energies for all double-mutant pairs (all numbers are expressed as absolute values to simplify the comparison between different pairings). The Q1-I368S/E1-D76N pairing shows the most significant coupling at 1.66 kcal/mol. Within the 12 pairs tested, this is by far the tightest energetic coupling, indicating that the residues interact during the C-O transition of the channel (Table 1). If we consider a less stringent energetic coupling, 1.0–1.5 kcal/mol, we see potential interacting sites of Q1-I368 with both E1-H73 and E1-S74, and between Q1-P369 with E1-D76. For simplicity, we have limited our interpretation to that between Q1-I368/E1-D76 with the strongest evidence for functional interaction.

Fig. 4.

Effects of double COOH-terminal mutations of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 on voltage-dependent activation (VDA). A: whole cell current traces of KCNQ1 mutants (Mut) with KCNE1 mutants in response to a series of depolarizing voltage steps (voltage clamp protocol shown above). B–E: normalized VDA curves of cardiac potassium current (IKs) carried by KCNQ1 wild-type (-WT) and KCNE1-Mut. All mutations are significantly left or right shifted (P < 0.05). See Table 1 for all Vh (voltage at which half of maximal activation occurs) values and n values.

Fig. 5.

Vh (voltage at which half of maximal activation occurs) values of cardiac potassium current (IKs) carried by KCNQ1 and KCNE1.

Fig. 6.

Double-mutant cycle analysis (DMCA) for KCNE1 and KCNQ1. A: exemplar double-mutant thermodynamic cycle for KCNQ1-I368S with KCNE1-D76N using Vh (voltage at which half of maximal activation occurs) and slope factor derived from Boltzmann fit of voltage dependence of activation (VDA) curves for the closed-to-open transition (see methods, Eq. 1). B: mean coupling energies [difference in Gibbs free energy of activation (ΔG; ΔΔG) coupling, absolute value] for all double-mutant pairings calculated as in A. See Table 1 for calculations of ΔG and ΔΔG and n values of all experiments.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here provide evidence for an important physical interaction between the cytoplasmic COOH-terminal regions of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 just as they emerge from the membrane. Several disease-causing mutations have been identified in this region, an indication of the physical and functional significance of this region. An early study that identified KCNE1 as a LQTS gene characterized two mutations, S74L and D76N, found in LQTS patients, and showed that both reduced IKs current by right-shifting the VDA (36). The more distal mutation Y81C also right shifts VDA (44). For the KCNQ1 proximal COOH terminus (residues 352–371) there are 14 LQTS-associated missense mutations. Of these, three have been characterized: Q357R and R366Q right shift the VDA, and R360G nearly eliminates all current (2, 22, 47). This in vitro evidence, based on clinically relevant mutations, indicates that the proximal COOH termini play an important role in normal channel function, particularly the relative stability of the channel in its closed and open states. Because many studies of the KCNQ1 and KCNE1 transmembrane domains place KCNE1 within close proximity to KCNQ1 S6 (4, 12, 18, 25, 30, 37–39, 43, 46), from which the KCNQ1 COOH terminus emerges, we hypothesized that the COOH termini of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 would lie close to each other as they exit the membrane and that direct interactions between residues might have a physiological impact on channel activity.

We (3, 23) previously identified the COOH terminus of KCNE1 as a domain that is important in determining the deactivation kinetics of IKs, differentiating it from the transmembrane domain, which controls activation kinetics. Truncation of the KCNE1 COOH terminus resulted in a right shift in VDA, decreased current density, and compromised rate adaptation, where the expected increase in current density with increased rate of depolarization was not observed. The truncation mutant also had a reduced association with KCNQ1, although it was not strictly required for binding and formation of the channel complex. A more limited truncation involving the proximal COOH terminus of KCNE1 but retaining the distal segments produced an IKs-like current with altered VDA that is consistent with the present results (6). Furthermore, recombinant KCNE1 COOH terminus was shown to coprecipitate with the KCNQ1 channel. These results point to a role for the KCNE1 COOH terminus in anchoring KCNE1 in the channel complex and stabilizing the open conformation of the channel, and/or destabilizing the closed conformation. Subsequent studies using different methodologies showed that KCNQ1 and KCNE1 COOH termini physically interacted with some differences in the precise location that may have been due to the potentially dynamic nature of the interaction (9, 50). Cysteine scanning mutagenesis of this region identified residues in KCNQ1-K363C and P369C in close enough proximity to react with KCNE1-H73C, S74C, and D76C in various combinations (21). Given this evidence, we sought to identify residues that functionally interact, and we turned first to HDX-MS as a method that would allow identification of region-specific interactions using the native sequence of each protein.

It is interesting to compare the HDX-MS findings with other structural information about the KCNE1 COOH terminus. Secondary sequence prediction by programs such as PSIPRED shows a more distal α-helical region near residues 90–98. This is supported by the NMR structure of KCNE1, although the structure of the NH2 and COOH termini are not determined with as much confidence as the transmembrane domain (13). Modeling of KCNQ1 with KCNE1 has been primarily of the transmembrane segments without docking of the COOH termini for the two proteins (12, 18, 46). In contrast, alanine/tryptophan scanning with periodicity analysis of the proximal KCNE1-CT suggests an α-helix interrupted by a conserved proline residue (P77) (32). Although seemingly at odds, there is one crucial factor differentiating these experiments that may account for the disparity: the secondary sequence prediction and NMR structure are of KCNE1 alone, although the periodicity and analysis were done in the presence of KCNQ1. Interaction between the two subunits may change the structure that KCNE1 adopts. Our HDX analysis of KCNE1-CT alone presents yet another set of parameters, wherein the KCNE1 COOH terminus is expressed both without its transmembrane domain and without KCNQ1. These circumstances may support the formation of a helical segment at the proximal end of the COOH terminus, as suggested by the finding of reduced deuterium exchange rate.

HDX-MS analysis of KCNQ1-C1 showed that the more distal residues (from 392 to 480) had relatively higher rates of deuterium exchange, whereas more proximal residues had reduced deuterium exchange. The overlapping residues indicate that the reduced exchange was centered on residues 364–391, which corresponds well with the predicted location of helix A, from about residue 370–382 (33). The entire KCNQ1 COOH terminus has four predicted α-helical regions, connected by flexible coils. The region just distal to the S6 domain, which emerges from the membrane, has been thought of as a linker, although its structure has not been elucidated. Secondary structure prediction yields an α-helix through residue 364 and then a coil through P369, after which helix A starts. The COOH terminus of KCNQ1 also contains two key calmodulin-binding sites, one of which resides in the portion that we have investigated (A370–A384), that is important for tetramerization and stabilization of the protein (7, 33). For our MBP-fusion proteins, we have found that exogenous calmodulin adds little to stability or oligomerization (50) and would have complicated the HDX-MS studies with additional peptides and interacting surfaces. Nevertheless, omission of calmodulin must be considered when interpreting our results.

HDX-MS defined regions of KCNQ1-KCNE1 COOH-terminal interaction involving KCNQ1 352–374 and KCNE1 70–81. Of interest, two KCNQ1 peptides showed an increase in deuterium exchange after interaction with KCNE1. KCNQ1 peptides 376–404 and 457–471 were deprotected, which may have occurred from allosteric conformational change upon binding to KCNE1, causing these regions to become more solvent accessible. This may explain why peptide 364–381 showed no significant change in either direction; since it straddles a protected and a deprotected region almost equally, which would have resulted in the relative loss and gain in deuterium canceling each other out. Previous binding studies using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis also gives evidence for a possible conformational change to KCNQ1 upon binding to KCNE1, as the SPR sensograms could be fitted to a two-state binding model (50).

Aided by localization of the physical interaction with HDX-MS, we chose those residues to analyze by DMCA to investigate functional interaction. Analysis of each single mutant individually revealed that the COOH-terminal regions are quite sensitive to perturbation, with all of the mutations resulting in significantly right-shifted VDA curves, with the exception of Q1-P369S. For closed-to-open transition, the pairing Q1-I368S with E1-D76N yielded the strongest ΔΔGcoupling energy at 1.66 kcal/mol. These findings may seem at odds with results from cysteine scanning mutagenesis that identified disulfide bond formation between KCNQ1-H363C and KCNE1-H73C, S74C, and D76C, as well as between KCNQ1-P369C and KCNE1-D76C (21). Although disulfide bond formation indicates proximity of residues, it does not necessarily mean they are functionally interacting in the native state. Our data do not preclude the proximity of these other residues. Furthermore, the disulfide bond experiments give a “snapshot” of residues in close proximity and do not reflect potential dynamics of interaction.

For the KCNQ family, KCNQ2–KCNQ5 sequence in the proximal COOH termini are quite conserved, with high homology or identity. KCNQ1 is less conserved with these family members and at position 368 KCNQ2–5 have arginine. Such a large difference may contribute to the unique gating that KCNE1 confers on KCNQ1. KCNE1 can bind to KCNQ2, -3, and -4 but without changing the current in the same manner (25, 34). More distal sites containing coil-coil domains are known to provide specificity in terms of subunit family tetramerization (27). Thus, our results suggest a specific divergent region in the COOH terminus of KCNQ1 that differentiates it from all its family members in terms of KCNE1 regulation.

We recognize several possible limitations and caveats to this study. One caveat of the HDX-MS data is that we did not have 100% sequence coverage of the proteins analyzed; for KCNE1-CT we were lacking a peptide that includes residues 103–107, and for KCNQ1-C1 we were missing the very COOH-terminal region of residues 472–480. It is possible that these residues may play some role in protein-protein interactions and we were simply unable to analyze the presence or absence of interactions. A potential limitation with DMCA is that some mutations may dramatically alter channel interaction without evidence of directly participating in the interactions. To avoid this, we first examined KCNQ1 mutant subunits without KCNE1 which verified that no dramatically detrimental effects were exerted independently of KCNE1 interactions (Supplemental Fig. S1 and Supplemental Table S1). Another possible limitation is that if these residues are not directly involved in an interaction, the mutation may induce an allosteric effect at a distance. Although we cannot be completely certain, the process of DMCA would likely have avoided such pitfalls.

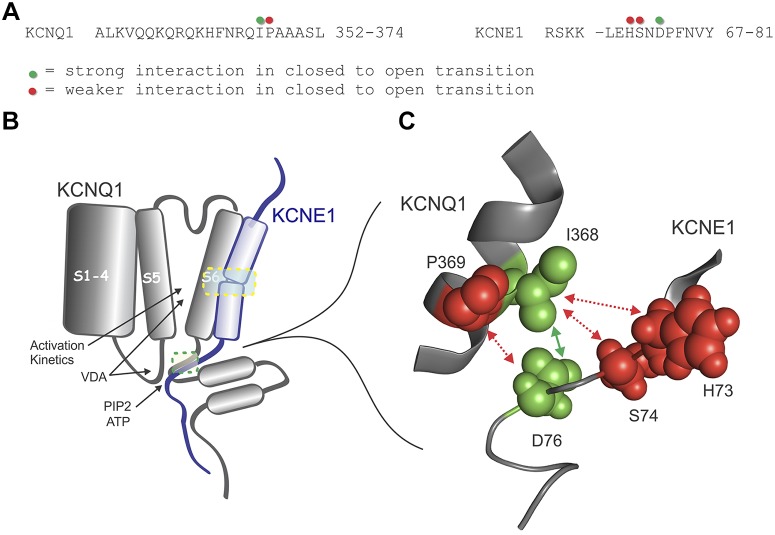

Multiple studies that have examined KCNQ1 and KCNE1 COOH termini are important to consider with respect to the present data. Dvir et al. (6) provided results suggesting that more distal segments of the two subunits interacted to determine channel regulation by protein kinase A and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). They further speculated that the proximal COOH terminus of KCNQ1 (largely overlapping with the segment studied in this work) existed close to the membrane and acted as a lever arm involved in channel gating (33). PIP2 binding has been explored by several groups that have shown interactions at KCNQ1 residues in the proximal COOH terminus, helix A-B linker, S23 linker, and S45 linker (6, 40, 41, 48). Kasimova et al. (14) have suggested that the KCNQ1 S45 linker interacts with the distal S6-CT in a PIP2-responsive fashion to influence gating. Furthermore, an ATP-binding site has been demonstrated in the KCNQ1 COOH terminus that involved proximal COOH terminus as well as in the Helix-A (20). Our data, in light of these other studies, leads us to refine an interaction site between KCNQ1 and KCNE1 where multiple signals and influences may occur to alter channel activation gating. It appears that, much like the rest of KCNE1, there are multiple important points of contact with the KCNQ1 channel, each of which may alter channel activity in different ways. We propose that at the proximal COOH termini of KCNQ1 (before the calmodulin-binding sites at the beginning of helix A) there exists a region of interaction with KCNE1 that significantly affects channel VDA. Figure 7 schematically illustrates this model and its complex confluence of signals (PIP2, ATP, calmodulin, and S45-S6-CT interactions). Given the possible mobility of this area (14) such interactions may dynamically change to achieve a degree of channel regulation that is complex. Further specifics of functional interactions would be greatly aided by future structural determinations of coassembled KCNQ1 with KCNE1 that included the COOH termini; however, the possibly flexible nature of the region may hinder crystallographic approaches.

Fig. 7.

A: sequences of KCNE1-CT (residues 67–129) and KCNQ1-C1 (residues 349–480) illustrating coverage of hydrogen-deuterium exchange with mass spectrometry and sites of interaction based on double-mutant cycle analysis. B: 2-dimensional rendering of experimentally determined sites of interaction between KCNE1 and KCNQ1 [and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and ATP] with the sites that control activation and deactivation kinetics indicated by dotted rectangles (only one KCNE1 subunit interacting with one KCNQ1 subunit is shown). C: schematic diagrams of KCNE1 interaction with KCNQ1. Three-dimensional rendering by Pymol showing KCNQ1 (Q1) and KCNE1 (E1) COOH-terminal interactions during the closed-to-open transition. VDA, voltage dependence of activation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants 1R01-HL-093440 (to T. V. McDonald) and F30-HL-096296 (to J. Chen).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.V.M. conceived and designed research; J.C., Z.L., J.P.C., R.Z., and T.V.M. performed experiments; J.C., Z.L., J.P.C., R.Z., and T.V.M. analyzed data; J.C., J.P.C., and T.V.M. interpreted results of experiments; J.C., Z.L., J.P.C., and T.V.M. prepared figures; J.C. drafted manuscript; J.C., Z.L., R.Z., and T.V.M. edited and revised manuscript; Z.L., R.Z., and T.V.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Mark Girvin and Steve Roderick of Albert Einstein College of Medicine for frequent insightful comments and suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barro-Soria R, Ramentol R, Liin SI, Perez ME, Kass RS, Larsson HP. KCNE1 and KCNE3 modulate KCNQ1 channels by affecting different gating transitions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E7367–E7376, 2017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710335114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulet IR, Raes AL, Ottschytsch N, Snyders DJ. Functional effects of a KCNQ1 mutation associated with the long QT syndrome. Cardiovasc Res 70: 466–474, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Zheng R, Melman YF, McDonald TV. Functional interactions between KCNE1 C-terminus and the KCNQ1 channel. PLoS One 4: e5143, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chouabe C, Neyroud N, Richard P, Denjoy I, Hainque B, Romey G, Drici MD, Guicheney P, Barhanin J. Novel mutations in KvLQT1 that affect Iks activation through interactions with Isk. Cardiovasc Res 45: 971–980, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00411-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung DY, Chan PJ, Bankston JR, Yang L, Liu G, Marx SO, Karlin A, Kass RS. Location of KCNE1 relative to KCNQ1 in the IKS potassium channel by disulfide cross-linking of substituted cysteines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 743–748, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811897106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dvir M, Strulovich R, Sachyani D, Ben-Tal Cohen I, Haitin Y, Dessauer C, Pongs O, Kass R, Hirsch JA, Attali B. Long QT mutations at the interface between KCNQ1 helix C and KCNE1 disrupt IKS regulation by PKA and PIP2. J Cell Sci 127: 3943–3955, 2014. doi: 10.1242/jcs.147033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh S, Nunziato DA, Pitt GS. KCNQ1 assembly and function is blocked by long-QT syndrome mutations that disrupt interaction with calmodulin. Circ Res 98: 1048–1054, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218863.44140.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleitsman KR, Kedrowski SM, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. An intersubunit hydrogen bond in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that contributes to channel gating. J Biol Chem 283: 35638–35643, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807226200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haitin Y, Wiener R, Shaham D, Peretz A, Cohen EB, Shamgar L, Pongs O, Hirsch JA, Attali B. Intracellular domains interactions and gated motions of IKS potassium channel subunits. EMBO J 28: 1994–2005, 2009. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch 391: 85–100, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horovitz A. Double-mutant cycles: a powerful tool for analyzing protein structure and function. Fold Des 1: R121–R126, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(96)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jalily Hasani H, Ahmed M, Barakat K. A comprehensive structural model for the human KCNQ1/KCNE1 ion channel. J Mol Graph Model 78: 26–47, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang C, Tian C, Sönnichsen FD, Smith JA, Meiler J, George AL Jr, Vanoye CG, Kim HJ, Sanders CR. Structure of KCNE1 and implications for how it modulates the KCNQ1 potassium channel. Biochemistry 47: 7999–8006, 2008. doi: 10.1021/bi800875q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasimova MA, Zaydman MA, Cui J, Tarek M. PIP2-dependent coupling is prominent in Kv7.1 due to weakened interactions between S4–S5 and S6. Sci Rep 5: 7474, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep07474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khrapunovich-Baine M, Menon V, Verdier-Pinard P, Smith AB III, Angeletti RH, Fiser A, Horwitz SB, Xiao H. Distinct pose of discodermolide in taxol binding pocket drives a complementary mode of microtubule stabilization. Biochemistry 48: 11664–11677, 2009. doi: 10.1021/bi901351q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khrapunovich-Baine M, Menon V, Yang CP, Northcote PT, Miller JH, Angeletti RH, Fiser A, Horwitz SB, Xiao H. Hallmarks of molecular action of microtubule stabilizing agents: effects of epothilone B, ixabepilone, peloruside A, and laulimalide on microtubule conformation. J Biol Chem 286: 11765–11778, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krumerman A, Gao X, Bian JS, Melman YF, Kagan A, McDonald TV. An LQT mutant minK alters KvLQT1 trafficking. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C1453–C1463, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00275.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuenze G, Duran AM, Woods H, Brewer KR, McDonald EF, Vanoye CG, George AL Jr, Sanders CR, Meiler J. Upgraded molecular models of the human KCNQ1 potassium channel. PLoS One 14: e0220415, 2019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laha KT, Wagner DA. A state-dependent salt-bridge interaction exists across the β/α intersubunit interface of the GABAA receptor. Mol Pharmacol 79: 662–671, 2011. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Gao J, Lu Z, McFarland K, Shi J, Bock K, Cohen IS, Cui J. Intracellular ATP binding is required to activate the slowly activating K+ channel IKs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 18922–18927, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315649110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lvov A, Gage SD, Berrios VM, Kobertz WR. Identification of a protein-protein interaction between KCNE1 and the activation gate machinery of KCNQ1. J Gen Physiol 135: 607–618, 2010. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matavel A, Medei E, Lopes CM. PKA and PKC partially rescue long QT type 1 phenotype by restoring channel-PIP2 interactions. Channels (Austin) 4: 3–11, 2010. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.1.10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melman YF, Domènech A, de la Luna S, McDonald TV. Structural determinants of KvLQT1 control by the KCNE family of proteins. J Biol Chem 276: 6439–6444, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melman YF, Krumerman A, McDonald TV. A single transmembrane site in the KCNE-encoded proteins controls the specificity of KvLQT1 channel gating. J Biol Chem 277: 25187–25194, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melman YF, Um SY, Krumerman A, Kagan A, McDonald TV. KCNE1 binds to the KCNQ1 pore to regulate potassium channel activity. Neuron 42: 927–937, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray CI, Westhoff M, Eldstrom J, Thompson E, Emes R, Fedida D. Unnatural amino acid photo-crosslinking of the IKs channel complex demonstrates a KCNE1:KCNQ1 stoichiometry of up to 4:4. eLife 5: e11815, 2016. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajo K, Kubo Y. Second coiled-coil domain of KCNQ channel controls current expression and subfamily specific heteromultimerization by salt bridge networks. J Physiol 586: 2827–2840, 2008. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakajo K, Ulbrich MH, Kubo Y, Isacoff EY. Stoichiometry of the KCNQ1 - KCNE1 ion channel complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18862–18867, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010354107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nyce HL, Stober ST, Abrams CF, White MM. Mapping spatial relationships between residues in the ligand-binding domain of the 5-HT3 receptor using a molecular ruler. Biophys J 98: 1847–1855, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panaghie G, Tai KK, Abbott GW. Interaction of KCNE subunits with the KCNQ1 K+ channel pore. J Physiol 570: 455–467, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price KL, Millen KS, Lummis SC. Transducing agonist binding to channel gating involves different interactions in 5-HT3 and GABAC receptors. J Biol Chem 282: 25623–25630, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocheleau JM, Gage SD, Kobertz WR. Secondary structure of a KCNE cytoplasmic domain. J Gen Physiol 128: 721–729, 2006. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachyani D, Dvir M, Strulovich R, Tria G, Tobelaim W, Peretz A, Pongs O, Svergun D, Attali B, Hirsch JA. Structural basis of a Kv7.1 potassium channel gating module: studies of the intracellular C-terminal domain in complex with calmodulin. Structure 22: 1582–1594, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroeder BC, Kubisch C, Stein V, Jentsch TJ. Moderate loss of function of cyclic-AMP-modulated KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K+ channels causes epilepsy. Nature 396: 687–690, 1998. doi: 10.1038/25367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith JA, Vanoye CG, George AL Jr, Meiler J, Sanders CR. Structural models for the KCNQ1 voltage-gated potassium channel. Biochemistry 46: 14141–14152, 2007. doi: 10.1021/bi701597s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Splawski I, Tristani-Firouzi M, Lehmann MH, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT. Mutations in the hminK gene cause long QT syndrome and suppress IKs function. Nat Genet 17: 338–340, 1997. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strutz-Seebohm N, Pusch M, Wolf S, Stoll R, Tapken D, Gerwert K, Attali B, Seebohm G. Structural basis of slow activation gating in the cardiac IKs channel complex. Cell Physiol Biochem 27: 443–452, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000329965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tai KK, Goldstein SA. The conduction pore of a cardiac potassium channel. Nature 391: 605–608, 1998. doi: 10.1038/35416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tapper AR, George AL Jr. Location and orientation of minK within the IKs potassium channel complex. J Biol Chem 276: 38249–38254, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas AM, Harmer SC, Khambra T, Tinker A. Characterization of a binding site for anionic phospholipids on KCNQ1. J Biol Chem 286: 2088–2100, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobelaim WS, Dvir M, Lebel G, Cui M, Buki T, Peretz A, Marom M, Haitin Y, Logothetis DE, Hirsch JA, Attali B. Ca2+-calmodulin and PIP2 interactions at the proximal C-terminus of Kv7 channels. Channels (Austin) 11: 686–695, 2017. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2017.1388478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venkatachalan SP, Czajkowski C. A conserved salt bridge critical for GABAA receptor function and loop C dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 13604–13609, 2008. [Erratum in Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6423, 2009.] doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801854105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang KW, Tai KK, Goldstein SA. MinK residues line a potassium channel pore. Neuron 16: 571–577, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu DM, Lai LP, Zhang M, Wang HL, Jiang M, Liu XS, Tseng GN. Characterization of an LQT5-related mutation in KCNE1, Y81C: implications for a role of KCNE1 cytoplasmic domain in IKs channel function. Heart Rhythm 3: 1031–1040, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu X, Jiang M, Hsu KL, Zhang M, Tseng GN. KCNQ1 and KCNE1 in the IKs channel complex make state-dependent contacts in their extracellular domains. J Gen Physiol 131: 589–603, 2008. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200809976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu Y, Wang Y, Meng XY, Zhang M, Jiang M, Cui M, Tseng GN. Building KCNQ1/KCNE1 channel models and probing their interactions by molecular-dynamics simulations. Biophys J 105: 2461–2473, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang T, Chung SK, Zhang W, Mullins JG, McCulley CH, Crawford J, MacCormick J, Eddy CA, Shelling AN, French JK, Yang P, Skinner JR, Roden DM, Rees MI. Biophysical properties of 9 KCNQ1 mutations associated with long-QT syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2: 417–426, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.850149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaydman MA, Silva JR, Delaloye K, Li Y, Liang H, Larsson HP, Shi J, Cui J. Kv7.1 ion channels require a lipid to couple voltage sensing to pore opening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 13180–13185, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305167110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Z, Smith DL. Determination of amide hydrogen exchange by mass spectrometry: a new tool for protein structure elucidation. Protein Sci 2: 522–531, 1993. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng R, Thompson K, Obeng-Gyimah E, Alessi D, Chen J, Cheng H, McDonald TV. Analysis of the interactions between the C-terminal cytoplasmic domains of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 channel subunits. Biochem J 428: 75–84, 2010. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]