Abstract

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate that peripheral diseases can trigger inflammation in the brain, causing psychosocial maladies, including depression. While few direct studies have been made, anecdotal reports associate urological disorders with mental dysfunction. Thus, we investigated if insults targeted at the bladder might elicit behavioral alterations. Moreover, the mechanism of neuroinflammation elicited by other peripheral diseases involves the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which is present in microglia in the brain and cleaves and activates proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β. Thus, we further explored the importance of NLRP3 in behavioral and neuroinflammatory changes. Here, we used the well-studied cyclophosphamide (CP)-treated rat model. Importantly, CP and its metabolites do not cross the blood-brain barrier or trigger inflammation in the gut, so that any neuroinflammation is likely secondary to bladder injury. We found that CP triggered an increase in inflammasome activity (caspase-1 activity) in the hippocampus but not in the pons. Evans blue extravasation demonstrated breakdown of the blood-brain barrier in the hippocampal region and activated microglia were present in the fascia dentata. Both changes were dependent on NLRP3 activation and prevented with 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium (Mesna), which masks the effects of the CP metabolite acrolein in the urine. Finally, CP-treated rats displayed depressive symptoms that were prevented by NLRP3 inhibition or treatment with Mesna or an antidepressant. Thus, we conclude that CP-induced cystitis causes NLRP3-dependent hippocampal inflammation leading to depression symptoms in rats. This study proposes the first-ever causative explanation of the previously anecdotal link between benign bladder disorders and mood disorders.

Keywords: bladder, cystitis, hippocampus, immunity, neuroinflammation

INTRODUCTION

There are numerous accounts in the literature of the association between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and depression (11). Particularly persuasive are the conclusions of the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study (11, 46), although mood disorders have been anecdotally associated with many of the underlying diseases for years including recurrent urinary tract infections (49), overactive bladder (20, 33, 57, 58), bladder outlet obstruction (16), and incontinence (19). Probably best known for this association is interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, a prevalent condition affecting up to 8 million women in the United States (4) that is strongly associated with depression (26, 37, 39, 47) and suicidal ideation (26). Despite considerable effort to understand the origin of these symptoms, the etiology has remained enigmatic.

Recently, breakthroughs have shown that several acute and chronic diseases of peripheral tissues trigger inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS) (23). Much of this groundbreaking knowledge is derived from studies of the gastrointestinal system. For example, Hsieh et al. (27) demonstrated that as little as 30 min of ischemia in the intestines results in an increase in the expression of inflammatory mediators and activation of microglia within the CNS. In addition, irritable bowel syndrome, which might be considered a colonic parallel to interstitial cystitis due to its unknown origin, inflammatory nature, and similar psychosocial comorbidities, also triggers neuroinflammation (14). Importantly, these peripheral to central pathways are not limited to the gastrointestinal system, for other peripheral insults such as burns, cardiac arrest, and acute pancreatitis can all result in CNS inflammation (23). Neuroinflammation is well known to cause mood disorders (44, 45, 48, 50, 56) and plays a major role in debilitating diseases such as major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder (10, 24). Therefore, based on these parallels with other disorders, we hypothesized that insults to the bladder may result in neuroinflammation in the CNS that leads to the psychosocial symptoms seen in patients with LUTS.

One of the best studied acute insults to the bladder is the effect of cyclophosphamide (CP) (5). CP is used as a chemotherapeutic and is broken down to acrolein (among other metabolites). Acrolein is stored in the urine before excretion where it is able to interact with the bladder wall and trigger a massive hemorrhagic cystitis. While this was once a very significant clinical problem, most cases are avoided these days by concomitant administration of 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium (Mesna), which binds acrolein in the urine and masks its harmful effects. In the present study, we used this model to determine if this acute insult in the bladder can result in central neuroinflammation and if this inflammation is responsible for depressive symptoms. Importantly, CP and its metabolites do not cross the blood-brain barrier (18, 59) and therefore are unlikely to have a direct effect on neuroinflammation. In addition, given the correlation between gut injury and neuroinflammation, it is important to note that CP does not inflame the gut and is in fact used as an anti-inflammatory treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (2). Thus, any effects of CP on the CNS are likely to be secondary to its bladder insult.

One of the mechanisms that is proving to play a fundamental role in behavior-changing neuroinflammation is the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)/IL-1β pathway (53). NLRP3, often referred to as the central processing unit of inflammation, is a component of the innate immune system that responds to damage and pathogens by forming an intracellular complex called the inflammasome (15). The inflammasome recruits and activates the protease caspase-1, which cleaves the proinflammatory cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms. These cytokines are then released from the cell via a form of necrotic programmed cell death called pyroptosis (15). Within the brain, the inflammasome is predominately located within glial cells where it has been implicated in the inflammatory processes of important diseases such as ischemic stroke and Alzheimer’s (25, 29). Thus, in this study, we have further explored a role for the NLRP3 pathway in mediating any neuropsychiatric effects of CP detected in the rat.

METHODS

Animals.

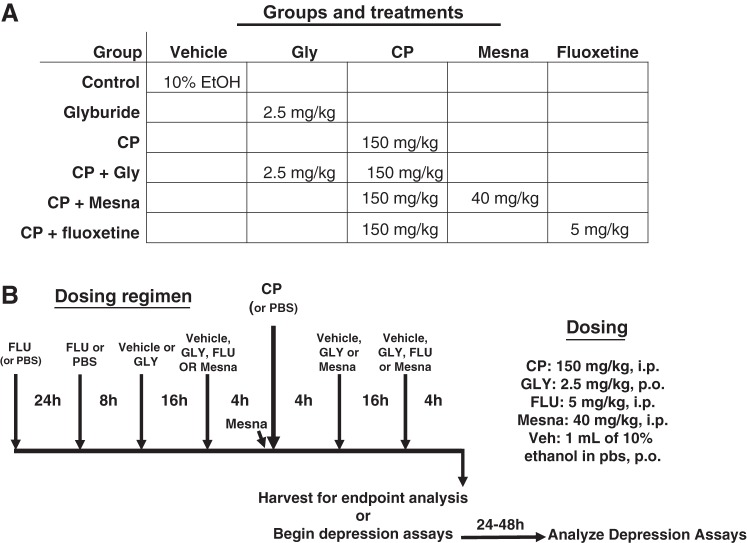

All protocols adhered with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University Medical Center. Female Sprague-Dawley rats (~200 g) were randomly divided into groups to receive the various treatments shown in Fig. 1A. Not all treatments groups were used for all end points. Rats were then subjected to the dosing regimen shown in Fig. 1B. Basically, animals were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of CP (150 mg/kg) or PBS as a control, and 24 h later, end-point analysis began. However, depending on the experiment, rats were also pretreated/treated with various inhibitors to assess the role of various pathways. To assess a role for NLRP3, rats were given the NLRP3 inhibitor glyburide (34) (GLY; 2.5 mg/kg in 10% ethanol in PBS, ≈800 µl/rat po; Ref. 28) or vehicle as the control. GLY was given in the evening before CP administration (5 PM) and again 16 h later (9 AM). Four hours later (1 PM), CP or PBS alone was injected (intraperitoneally). Additional doses of GLY were given 4 h (5 PM) and 20 h (9 AM) after CP injection. Twenty-four hours after CP injection, animals were euthanized or entered into the Evans blue protocol or behavior assays. To assess a role for acrolein-induced cystitis, Mesna (40 mg/kg; Ref. 1) was administered to a group of animals 4 h before CP, immediately before CP, and 4 and 16 h after CP. For behavior assays, an additional group of rats was administered the antidepressant fluoxetine (FLU) as a control. FLU was given 48, 24, and 4 h before CP administration (and 20 h after). This proved to be the minimum time necessary to see effects of fluoxetine, which are most noted chronically, but acute effects have been reported (52).

Fig. 1.

Groups and treatments used in this study. A: diagram of the various groups utilized in this project and the doses of the various treatments used for each group. Not all groups were used for all end points, as described in the text. B: dosing regimen for the experiments. Rats were given the drugs at the indicated doses at the indicated times. CP, cyclophosphamide; GLY, glyburide; FLU, fluoxetine; Veh, vehicle; Mesna, 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium.

Bladder weight.

Bladder weights were recorded at the time of euthanasia.

Evans blue assay and gross analysis.

Inflammation in the bladder and inflammation/blood-brain barrier permeability in the brain were measured using Evans blue dye (3, 42). Rats were injected intravenously in the tail vein (2%, 3 ml/kg). One hour after injection, rats were euthanized and transcardially perfused through a ventricular catheter to remove intravascular dye. For gross analysis, brains were isolated and sectioned coronally using a scalpel and photographed. For other analyses, bladders were removed, weighed, and placed into 1 mL formamide. The hippocampus and pons were dissected out, weighed, and placed into 250 µL formamide. Samples were then incubated at 56°C overnight with shaking. Absorbance was measured (620 nm), and the results were calculated as picograms of Evans blue per micrograms of tissue using a standard curve of Evans blue absorbance.

Caspase-1 activity.

Caspase-1 activity was measured using a fluorometric assay as previously described (28). Briefly, samples were homogenized in 200 μL lysis buffer (10 mM MgCl2 and 0.25% Igepal CA-630) and centrifuged (10,000 g, 10 min), and the supernatant was mixed with equal parts storage buffer [40 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 20 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 20% glycerol]. Extract (75 μL) was combined with 25 μL of a 1:1 combination of lysis and storage buffer, 50 μL assay buffer [25 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 5% sucrose, and 0.05% CHAPS], 10 μL of 100 mM DTT, and 20 μL of 1 mM N-acetyl-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-7-amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (Ac-YVAD-AFC) in blacked-walled 96-well plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the dark with mild shaking. Fluorescence (excitation: 400 nm and emission: 505 nm) was measured and compared with a standard curve of fluorescence versus free AFC to determine the rate of product production. Protein concentrations of sample aliquots were assessed by Bradford assay (7), and rates were normalized to protein to calculate the specific activity of caspase-1.

Quantitative PCR.

Quantitative PCR was performed by Gene Master, LLC (Cary, NC) using their standard techniques. RNA was extracted using TRIzol (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and samples were stored at −20°C until transferred to Gene Master (<2 wk). cDNA was then generated (Invitrogen Superscript III kit), and quantitative PCR was run in triplicate with validated primers [pro-IL-1β: forward 5′-CACCTTCTTTTCCTTCATCTTTG-3′ and reverse 5′-TCGTTGCTTGTCTCTCCTTG-3′; pro-IL-18: forward 5′-AGGCTCTTGTGTCAACTTCAAA-3′ and reverse 5′-AGTCTGGTCTGGGATTCGTT-3′; NLRP3: forward 5′-GAAGATTACCCACCCGAGAAA-3′ and reverse 5′-CCAGCAAACCTATCCACTCC-3′; and associated speck-like protein containing a COOH-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC): forward 5′-ATCTGGAGGGGTATGGCTTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CTTGTTTTGGTTGGGGGTCT-3′] using β-actin (forward 5′-CCCATTGAACACGGCATT-3′ and reverse 5′-ACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACA-3′) as an internal control. Gene expression levels of vehicle-treated rats were averaged and normalized to a value of 1. Results are presented as relative expression (fold increase) of the studied genes in treated rats compared with vehicle.

Histological analysis.

Whole brains were immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (room temperature, 48 h), sliced coronally, and embedded in paraffin blocks with the cut hippocampal plane on the block face. Sections (10 µm) were then cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using routine methods. Sections were visualized using Olympus Vanox BH-2 microscope and analyzed by a board-certified pathologist (W. T. Harrison) for evidence of inflammation and changes in microglia.

Immunocytochemistry and quantitation of microglia.

Coronal sections (10 μm) of the hippocampus were stained with anti-IbA1/AIF1 (1:500, catalog no. NBP2-19019, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO) using standard methods and citrate antigen retrieval. Horseradish peroxidase development was accomplished with the Vectastain ABC Staining Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) using the secondary antibody provided. All sections were imaged on a Zeiss Axio Imager 2 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) running Zen software (Zeiss), using the tiling and stitching feature to ensure the entire fascia dentata was visualized. Images were imported into NIS-Elements software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). One hemisphere was chosen, and 600,000–700,000 µm2 of the fascia dentata were demarcated as the region of interest. The number of microglia within this region was then counted. Microglia cells were defined as black/brown spots with two or greater associated tendrils, and the number present in the region of interest was counted. Microglial density was then calculated.

Behavioral assays.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the sucrose preference assay and the forced swim assay. These assays began 24 h after CP treatment and required 24–48 h to complete. No additional medications were given to the animals during this period. In the sucrose preference assay, animals were presented two bottles simultaneously: one bottle containing a 2% sucrose solution and the other bottle containing drinking water. The amount of liquid consumed in each bottle during the 24 h of testing was measured. The location of the two bottles was varied during this period. The sucrose preference score was expressed as percentage of total liquid intake.

In the forced swim assay, rats were placed in tap water (25–27°C) within a large, clear cylinder (catalog no. 76-0494, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), such that neither the animal’s legs nor their tail touched the bottom. Rats were left in this cylinder for a 10-min training period. Twenty-four hours later (48 h after CP), rats were then placed back in the cylinder and recorded for 5 min (Logitech Webcam, Silicon Valley, CA). The recordings were quantified for time spent immobile by several blinded individuals, and the average score was used in each individual measurement. Immobility was defined as absence of movement except for those necessary for keeping the nose above water.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences were assessed using a two-tail Student’s t test or ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis, as indicated in the figures. All statistical analyses were conducted using Graph Pad In Stat Software (La Jolla, CA), and results were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

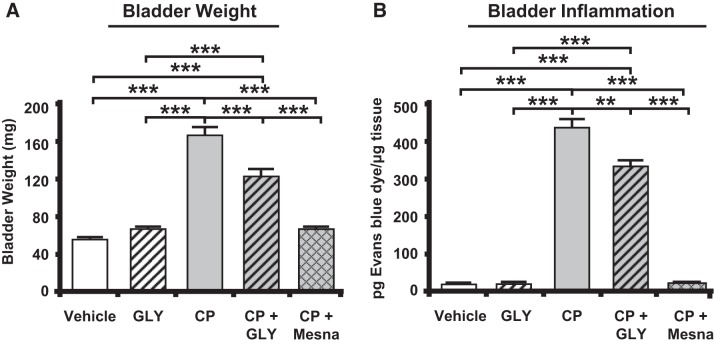

CP administration increased bladder weight and inflammation.

Bladder weight and inflammation was used to confirm effective induction of cystitis. As shown in Fig. 2A, rat bladder weights were significantly increased 24 h after CP administration. Additionally, there was a significant increase in inflammation as indicated by extravasation of Evans blue (Fig. 2B). Consistent with a prior study (28), both bladder weight and inflammation were reduced when CP-treated rats also received GLY, although the levels were still higher than vehicle-treated or GLY-only treated rats (Fig. 2, A and B). As expected, concomitant treatment with Mesna blocked the changes in both end points to levels not significantly different from vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 2.

Bladder weights and inflammation are increased in response to cyclophosphamide (CP), and this is blocked by glyburide (GLY) or 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium (Mesna). A: bladder weights at euthanize were higher after CP treatment, and this was reduced by treatment with GLY or Mesna. Bars represent mean bladder weight ± SE (vehicle: n = 32, CP: n = 42, GLY: n = 17, CP + GLY: n = 20, and CP + Mesna: n = 34). B: inflammation in the bladder, as measured by Evans blue dye extravasation, was increased after CP treatment, and this was reduced by treatment with GLY or Mesna. Results are reported as pg Evans blue dye/µg tissue. Bars represent means ± SE (vehicle: n = 3, GLY: n = 3, CP: n = 4, CP + GLY: n = 4, and CP + Mesna: n = 4). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis.

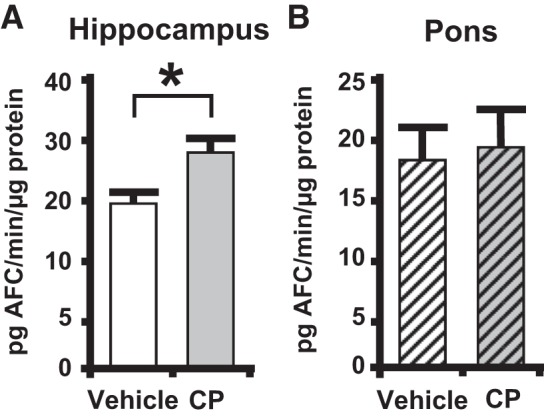

Caspase-1 activity is increased in the hippocampus but not in the pons.

As shown in Fig. 3A, there was a significant increase in caspase-1 activity, a marker of inflammasome activation, in the hippocampus of CP-treated rats at 24 h. This increase was not present in the pons (Fig. 3B). This suggests that central activation of the inflammasome in response to CP-induced cystitis is occurring, at least in part, within the hippocampus and that this effect is specific and not a general response in the brain to CP or its metabolites.

Fig. 3.

Caspase-1 activity is increased in the hippocampus, not the pons, of cyclophosphamide (CP)-treated rats. Central nervous system tissue was harvested and processed as described in methods. A: hippocampus caspase-1 activity in vehicle- and CP-treated rats. Results are reported as pg 4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (AFC)·min−1·µg protein−1. Bars represent mean activity ± SE. B: caspase-1 activity in the pons in vehicle- and CP-treated rats. Results are reported as pg AFC·min−1·µg protein−1. Bars represent mean activity ± SE (for both A and B, vehicle: n = 4 and CP: n = 4). *P < 0.05 by a two-tailed Student’s t test.

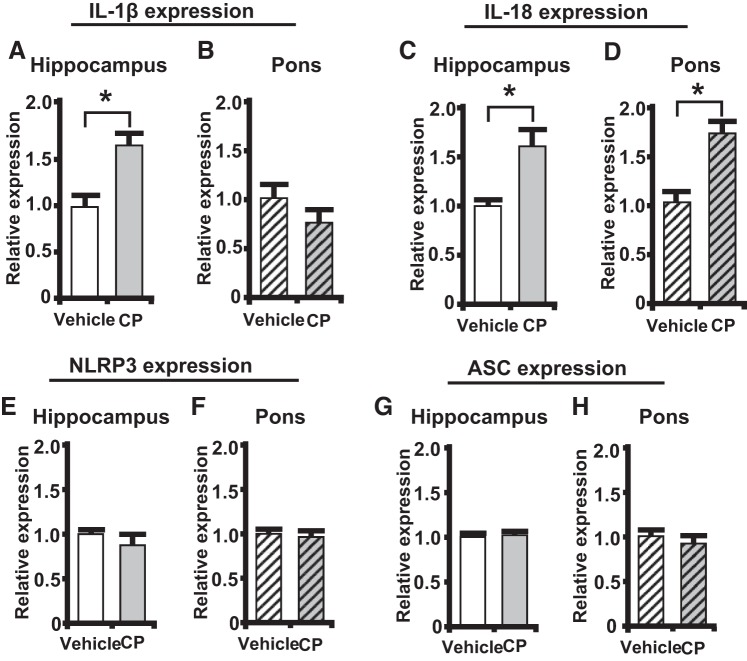

Pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 mRNA expression are increased in the hippocampus.

Gene expression of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 was measured in the hippocampus and pons. As shown in Fig. 4A, there was a significant increase in pro-IL-1β expression in the hippocampus of CP-treated rats while no change in expression was found within the pons (Fig. 4B). A significant increase of pro-IL-18 gene expression was also found in the hippocampus of CP-treated rats (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, there was also an increase in pro-IL-18 expression in the pons of CP-treated rats (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 mRNA expression levels are increased in the hippocampus during cyclophosphamide (CP)-induced cystitis. NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) and associated speck-like protein containing a COOH-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC) mRNA expression levels were unchanged in the hippocampus during CP-induced cystitis. Results are expressed as relative expression of the studied genes in treated rats compared with vehicle. Bars represent mean expression levels ± SE. A: pro-IL-1β levels in the hippocampus (vehicle: n = 13 and CP: n = 12). B: pro-IL-1β levels in the pons (vehicle: n = 6 and CP: n = 6). C: pro-IL-18 expression levels in the hippocampus (vehicle: n = 8 and CP: n = 7). D: pro-IL-18 expression levels in the pons (vehicle: n = 4 and CP: n = 4). E: NLRP3 levels in the hippocampus (vehicle: n = 9 and CP: n = 8). F: NLRP3 levels in the pons (vehicle: n = 6 and CP: n = 6). G: ASC expression levels in the hippocampus (vehicle: n = 9 and CP: n = 8). H: ASC expression levels in the pons (vehicle: n = 6 and CP: n = 6). *P < 0.05 by a two-tailed Student’s t test.

NLRP3, and other critical components of the inflammasome such as ASC, have been found to be upregulated in many other inflammatory conditions, although their expression is regulated by mechanisms different than those regulating pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 (54). However, as shown in in Fig. 4, E–H, we did not see significant changes in either NLRP3 or ASC in the hippocampus or pons of CP-treated rats.

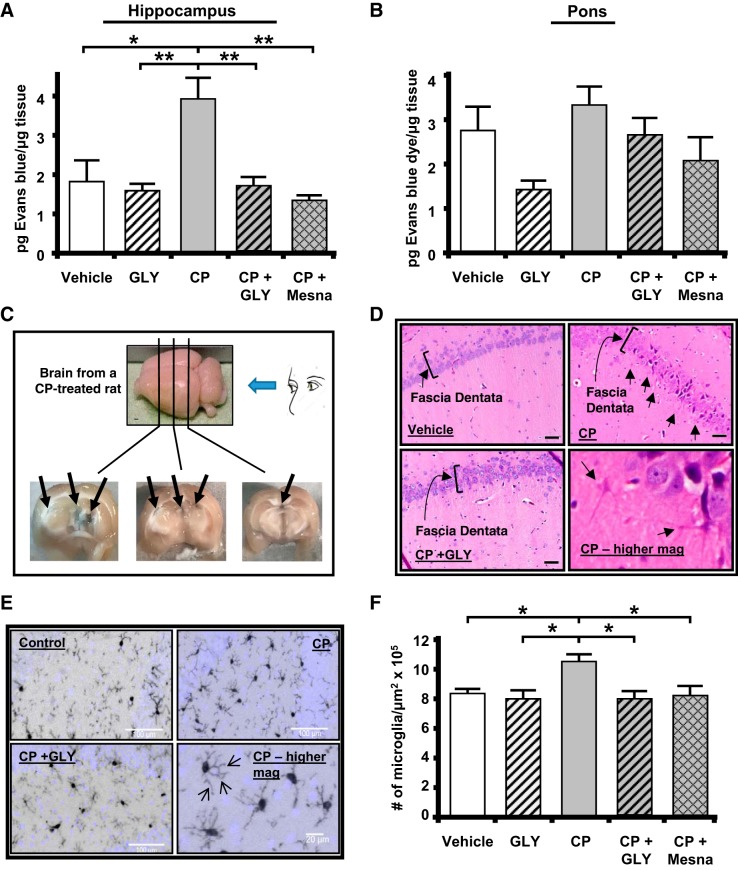

CP-induced cystitis induces NLRP3-dependent inflammation in the hippocampus.

Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier is one of the known consequences of NLRP3-induced inflammation within the CNS (53). To evaluate this change, we performed the Evans blue assay (3, 42). In the hippocampus from CP-treated rats, we detected a significant increase in Evans blue extravasation compared with vehicle-treated or GLY only-treated controls, indicating inflammation and disruption of the blood-brain barrier (Fig. 5A). Critically, the administration of either GLY or Mesna at the times shown in Fig. 1B reduced the dye extravasation to levels not significantly different from controls. In the pons (Fig. 5B), there was no significant change in dye extravasation in response to CP, clearly demonstrating the effect in the hippocampus was specific and not a general breakdown of this barrier. When gross cross sections of the brain from CP-treated rats were examined (Fig. 5C), areas of Evans blue dye were apparent in the periventricular region of the hippocampal formation, where the dye was permeating through areas of true blood-brain barrier breakdown and not through the circumventricular organs. These blue areas were not observed in any other group (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Cyclophosphamide (CP)-induced cystitis results in inflammation and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier in the hippocampus, not in the pons. Administration of glyburide (GLY) or 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium (Mesna) blocks this effect. A: Evans blue extravasation was increased in the hippocampus by CP. This increase was prevented by treatment with GLY or Mesna. All results were calculated as pg Evans blue per μg tissue. B: Evans blue extravasation was not significantly changed in the pons by any treatment. Bars represent means ± SE. For A, vehicle: n = 3, GLY: n = 3, CP: n = 4, CP + GLY: n = 4, and CP + Mesna: n = 4. For B, vehicle: n = 4, GLY: n = 3, CP: n = 4, CP + GLY: n = 4, and CP + Mesna: n = 8. C: CP-induced cystitis resulted in areas of gross blood-brain barrier breakdown, with Evans blue dye apparent (arrows) in the periventricular region of the hippocampus. A CP-treated rat was injected with Evans blue as described in methods. After 1 h, the brain was removed, sectioned coronally with a scalpel at the approximate locations indicated, and photographed. D: CP resulted in a NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)-dependent increase in the number of microglia-like cells within the fascia dentata of the hippocampus. Coronal sections (10 µm) were cut through the hippocampus, and a hematoxylin and eosin stain was performed using routine methodical techniques. Slides were visualized at ×60. Activated glial cells are indicated by arrows. E: immunohistochemistry showed increased density of activated microglia within the fascia dentata. Coronal sections (10 µm) were cut, and immunohistochemistry was performed using an anti-IbA1/AIF1 antibody and routine histological methods. Slides were visualized at ×20, and the number of microglia was quantitated. Arrows demonstrating increased glial processes (arrows) at higher magnification are shown. F: density of microglia. Results are depicted as the number of microglia per μm2. Bars represent means ± SE (vehicle: n = 5, GLY: n = 6, CP: n = 7, CP + GLY: n = 4, and CP + Mesna: n = 8). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis.

Histologically, the hippocampus demonstrated evidence of inflammation in the CP-treated rats (Fig. 5D). In particular, cells with morphology of activated microglia were present in CP-treated samples (arrows in Fig. 5D, top and bottom right). These inflammatory changes were found predominantly in and around the fascia dentata (indicated by brackets in top left). The activated microglia were not present when CP-treated rats were administered GLY (CP + GLY group shown in Fig. 5D, bottom left; for all other groups, data not shown). To quantitate these changes, hippocampal sections were stained for IbA1/AIF1, a marker of activated microglia, and the density of activated microglia in the fascia dentata region was quantitated. Figure 5E shows a typical staining pattern for control, CP, and CP + GLY samples (other groups not shown). Figure 5F shows the results of this quantitation with a significantly increased density of microglia in the CP-treated rat. This increase was blocked to levels not significantly different from controls when rats were treated with either GLY or Mesna. Qualitatively, we also noted an increase in microglial processes in brains from CP-treated rats (arrows in Fig. 5E, bottom right).

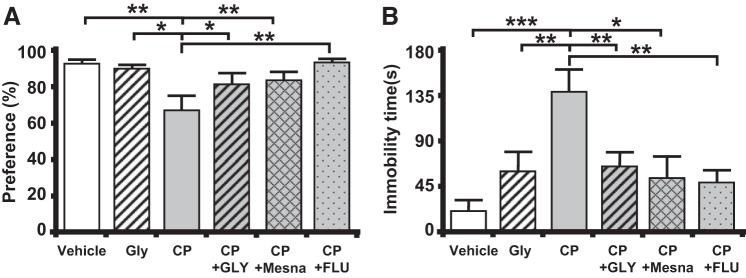

CP-induced cystitis results in NLRP3-dependent symptoms of depression.

To determine if CP-induced cystitis results in depressive symptoms, we performed two independent behavioral assays, the sucrose preference assay and the forced swim assay. For these experiments, an additional control group of CP-treated rats were administered the antidepressant fluoxetine to differentiate true depression symptoms from sick behavior, which would not be affected by the antidepressant. In the sucrose preference assay (Fig. 6A), CP-treated rats consumed a significantly lower percentage of sucrose-laden water. Importantly, this change was prevented when CP-treated rats were treated with GLY, Mesna, or fluoxetine. In the forced swim assay (Fig. 6B), CP-treated rats spent significantly more time immobile when compared with control. Critically, this change was also prevented by GLY, Mesna, and fluoxetine.

Fig. 6.

Cyclophosphamide (CP) induces behavioral signs of depression through NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3). A: sucrose preference test. A reduction of preference indicates depression. Bars represent means ± SE [vehicle: n = 10, glyburide (GLY): n = 4, CP: n = 8, CP + GLY: n = 6, CP + 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium (Mesna): n = 12, and GP + fluoxetine (FLU): n = 8]. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis. B: forced swim assay. An increase in time spent immobile indicates depression. Bars represent means ± SE (vehicle: n = 9, GLY: n = 18, CP: n = 8, CP + GLY = 18, CP + Mesna: n = 6, and GP + FLU: n = 11). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis.

DISCUSSION

Chronic inflammatory syndromes are present in every specialty in medicine. Whether it is irritable bowel syndrome in gastroenterology or interstitial cystitis in urology, these conditions present a myriad of challenges to physicians and patients. These patients have high rates of comorbid depression, anxiety, and other related psychiatric disorders, and recent studies have begun to demonstrate this adverse psychosocial consequence may be due to neuroinflammation mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome (45). The present study has shown, for the first time, that an acute insult to the bladder in an animal model can also result in neuroinflammation in the CNS and the associated symptoms of depression.

We began our study looking for signs of inflammasome activation (caspase-1 activity) in the hippocampus, due to its known association with depression, and the pons, due to its well-known function in micturition. We found just such an increase within the hippocampus 24 h after CP treatment but no significant changes in the pons. This differential response suggests the effect is specific to this region and not a nonspecific, perhaps toxic, response of the brain to CP or its metabolites. Often associated with inflammasome activation is an increase in the expression of pro-IL-1β and/or pro-IL-18. Accordingly, we found increased mRNA expression of both of these proinflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus, consistent with inflammasome activation or at least the beginning of an inflammatory response. Surprisingly, pro-IL-18 was significantly increased in the pons, suggesting that this region of the brain is actually responding to CP. However, we found no other indication of an inflammatory reaction, so the significance of the rise in IL-18 remains unknown.

One of the most significant changes we discovered was that CP-induced cystitis triggers breakdown of the blood-brain barrier within the hippocampus but not the pons. While it is intuitively obvious that partial dissolution of this barrier is detrimental to the integrity of the CNS, the demarcation between the hippocampus and pons confirms that neither CP itself nor its metabolites are directly causing this breakdown. If direct effects were involved, the breakdown could be expected to occur throughout the CNS and not localize to the hippocampus. It should be noted that our experiments do not rule out inflammation and inflammasome activation in other parts of the brain. Importantly, GLY prevented this blood-brain barrier breakdown. Seeing as GLY is an inhibitor of NLRP3 with little or no effects on other inflammasomes (34), these results specifically implicate the NLRP3 inflammasome in this response. Finally, the breakdown of this barrier was also blocked with Mesna, which is well known to bind acrolein in the urine and prevent it from harming urothelia. Mesna undergoes rapid oxidation in plasma with only a very small portion remaining in the circulation. Thus urinary Mesna concentration vastly exceeds that in plasma, essentially restricting this compound to the urinary system (9, 30). Indeed, doses up to 100 mg/kg (compare with 40 mg/kg used in this study) have produced no apparent effects on bone marrow, hepatic, renal or CNS function (9, 30). Thus, Mesna’s effectiveness in this study strongly argues that the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier in the hippocampus is a direct result of the cystitis triggered by CP in the bladder.

While Evans blue does detect breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, it is also a harbinger of inflammation in a tissue. Indeed, we found histological evidence of inflammation in CP-treated rats within the fascia dentata. Quantitation of the activated microglia in this region clearly showed an increased density, and this increase was again blocked by both GLY and Mesna. Thus, these results demonstrate that the NLRP3 inflammasome plays a critical role in inducing inflammation in the hippocampus in response to CP-induced cystitis. Therapeutically, administration of a NLRP3 inhibitor at the time of an acute inflammatory event may serve as a critical intervention to prevent the emergence of neuroinflammatory changes.

At this time, the mechanism by which inflammation in the bladder results in inflammation in the hippocampus is unclear. In fact, the mechanism transmitting inflammatory signals to the brain from peripheral sources is an in vogue topic that is rapidly developing. Currently, there are three distinct pathways that may contribute to varying degrees (45). The first pathway, called the humoral pathway, includes the leaking of peripheral cytokines directly into the CNS through areas of blood-brain barrier breakdown. Given serum proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6) are increased in response to CP (31), and we detected barrier breakdown, we feel this pathway likely contributes to CP induction of neuroinflammation. Peripheral cytokines may also be directly transported across the barrier through saturable transport molecules (45), although we have not examined this possibility. The second pathway, the neural pathway, involves cytokine stimulation of afferent nerves that carry retrograde transmission of a signal for inflammation through ascending fibers and into the brain where they are translated back into central cytokine signals (44). Recent evidence has established an inflammatory phenotype within the L6-S1 dorsal quadrants of the spinal cord in CP-induced cystitis (36), suggesting that neural transfer of an inflammatory response may also be playing a role in moving the signal from the bladder to the CNS. Likewise, CP-induced cystitis is well known to cause bladder pain, and acute pain itself can directly stimulate symptoms of depression (41), most likely through this neural transfer pathway. Finally, a third pathway, called the cellular pathway, has been found to contribute to the transfer of inflammatory signals (12). This pathway involves movement of immune cells that have been activated in the periphery directly to the brain vasculature and parenchyma. This pathway was discovered in studies of the inflamed liver, which releases TNF-α. TNF-α crosses the blood-brain barrier and stimulates the release of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 from microglia, which, in turn, passes back into the periphery and triggers the chemotaxis of monocytes into the brain (12). As stated earlier, there are increases in serum levels of TNF-α in response to CP (31), so it is possible these pathways are involved as well. Clearly, there is considerable fodder for future exploration in this area.

Regardless of how the peripheral inflammatory signal is transferred, once the brain is inflamed, it is well known to bring about symptoms of depression and other negative psychosocial behaviors (44, 45, 48, 50, 56). Indeed, using two distinct and well-established assays of depression, we found that symptoms of depression strongly correlated with neuroinflammation in the present study. While these studies do not address how neuroinflammation actually brings about these symptoms, numerous theories abound in the literature (44, 45), suggesting that the mechanism may be multifactorial. For example, cytokine signals are known to influence the availability of mood-relevant neurotransmitters, particularly the monoamines (43). Many of these signals, working through well-known STAT, interferon regulatory factor, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways (17), activate indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase, which shifts tryptophan metabolism toward kynurenine and away from serotonin, thus reducing serotonin availability (13, 51). Kynurenine (converted to kynurenic acid in microglia) also inhibits the release of glutamate and, by extension, dopamine (6). Other work on potential pathways leading to depression demonstrates that cytokine signals may significantly affect neural plasticity, triggering decreased neurotrophic support, decreased neurogenesis, increased oxidative stress, and even increased apoptosis in the CNS (8, 22, 32, 35, 38). Perhaps the effects on neural plasticity may explain why, in some disorders of the genitourinary tract such as interstitial cystitis, debilitating psychiatric effects can persist long after any localized inflammation is measurable. Finally, cytokines may have dramatic effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (21, 40), and dysregulation of the HPA axis has been suggested to underlie increased psychological stress levels in patients with overactive bladder and interstitial cystitis, at least those exposed to chronic early life stress (55). The contributions of these various pathways to the mood disorders experienced by patients with diseases of the lower urinary tract represent important and exciting areas for exploration while offering the promise of targeted pharmacological interventions to alleviate the high morbidity and healthcare costs associated with the mental suffering of urology patients.

In conclusion, we have shown in an animal model that an acute insult in the bladder can trigger significant neuroinflammation in the hippocampus, which brings about symptoms of depression. Moreover, the inflammation/depression responsive is dependent on activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Thus, this study proposes the first-ever causative explanation of the previously anecdotal link between benign bladder disorders and mood disorders. However, it is limited by the acute nature of the CP-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. While it has been demonstrated that behavioral changes occur in the short-term response to bladder inflammation, this does not confirm the presence of a specific clinical diagnosis, such as depression or anxiety, as these are chronic conditions that can be accurately modeled only in more chronic studies. Future studies will use longer-term experiments that use repeated insults over time to definitively link bladder inflammation and neuroinflammation with specific psychiatric diseases. The present study justifies these longer projects by demonstrating a novel mechanism of neuroinflammation that is likely to be activated in the setting of chronic bladder inflammation.

GRANTS

This work was awarded the Swiss Continence Foundation Award at the 7th International Neuro-Urology Meeting, January, 24–26, 2019, in Zurich, Switzerland. This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01-DK-103534 (to J. T. Purves).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.A.H., F.M.H., and J.T.P. conceived and designed research; N.A.H., H.J., S.W.W., and I.D. performed experiments; N.A.H., F.M.H., W.T.H., S.W.W., I.D., S.N.H., and P.D.L. analyzed data; N.A.H., F.M.H., W.T.H., and J.T.P. interpreted results of experiments; N.A.H. and F.M.H. prepared figures; N.A.H. and F.M.H. drafted manuscript; N.A.H., F.M.H., S.N.H., and J.T.P. edited and revised manuscript; N.A.H., F.M.H., and J.T.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Fuller and the Substrate Services Core and Research Support Services in the Dept. of Surgery for help with histological embedding and sectioning. We also thank the Light Microscopy Core Facility and Y. Gao for help obtaining images. Both core facilities are at Duke University Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali SA, Danda SK, Basha SA, Rasheed A, Ahmed O, Ahmed MM. Comparision of uroprotective activity of reduced glutathione with mesna in ifosfamide induced hemorrhagic cystitis in rats. Indian J Pharmacol 46: 105–108, 2014. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.125188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barta Z, Tóth L, Zeher M. Pulse cyclophosphamide therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 12: 1278–1280, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belayev L, Busto R, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Quantitative evaluation of blood-brain barrier permeability following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Brain Res 739: 88–96, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)00815-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M, Bogart LM, Stoto MA, Eggers P, Nyberg L, Clemens JQ. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol 186: 540–544, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birder L, Andersson KE. Animal modelling of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Int Neurourol J 22, Suppl 1: S3–S9, 2018. doi: 10.5213/inj.1835062.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borland LM, Michael AC. Voltammetric study of the control of striatal dopamine release by glutamate. J Neurochem 91: 220–229, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254, 1976. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buntinx M, Moreels M, Vandenabeele F, Lambrichts I, Raus J, Steels P, Stinissen P, Ameloot M. Cytokine-induced cell death in human oligodendroglial cell lines: I. Synergistic effects of IFN-γ and TNF-α on apoptosis. J Neurosci Res 76: 834–845, 2004. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carless PA. Proposal for the inclusion of mesna (sodium 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate) for the prevention of ifosfamide and cyclophosphamide (oxazaphosphorine cytotoxics) induced haemorrhagic cystitis. Geneva, Switzerland: 17th Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colpo GD, Leboyer M, Dantzer R, Trivedi MH, Teixeira AL. Immune-based strategies for mood disorders: facts and challenges. Expert Rev Neurother 18: 139–152, 2018. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2018.1407242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Kopp ZS, Aiyer LP. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int 103, Suppl 3: 4–11, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Mello C, Le T, Swain MG. Cerebral microglia recruit monocytes into the brain in response to tumor necrosis factoralpha signaling during peripheral organ inflammation. J Neurosci 29: 2089–2102, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3567-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 46–56, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daulatzai MA. Chronic functional bowel syndrome enhances gut-brain axis dysfunction, neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment, and vulnerability to dementia. Neurochem Res 39: 624–644, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Virgilio F. The therapeutic potential of modifying inflammasomes and NOD-like receptors. Pharmacol Rev 65: 872–905, 2013. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.006171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunphy C, Laor L, Te A, Kaplan S, Chughtai B. Relationship between depression and lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev Urol 17: 51–57, 2015. doi: 10.3909/riu0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujigaki H, Saito K, Fujigaki S, Takemura M, Sudo K, Ishiguro H, Seishima M. The signal transducer and activator of transcription 1alpha and interferon regulatory factor 1 are not essential for the induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by lipopolysaccharide: involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways, and synergistic effect of several proinflammatory cytokines. J Biochem 139: 655–662, 2006. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genka S, Deutsch J, Stahle PL, Shetty UH, John V, Robinson C, Rapoport SI, Greig NH. Brain and plasma pharmacokinetics and anticancer activities of cyclophosphamide and phosphoramide mustard in the rat. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 27: 1–7, 1990. doi: 10.1007/BF00689268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giannantoni A, Gubbiotti M, Mearini E, Balducci PM, de Vermandois JA. MP27-11 overactive bladder, urinary incontinence and depression. J Urol 199, 4S: e350–e351, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.02.890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golabek T, Skalski M, Przydacz M, Świerkosz A, Siwek M, Golabek K, Stangel-Wojcikiewicz K, Dudek D, Chlosta P. Lower urinary tract symptoms, nocturia and overactive bladder in patients with depression and anxiety. Psychiatr Pol 50: 417–430, 2016. doi: 10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/59162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, Yirmiya R. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry 13: 717–728, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ounallah-Saad H, Renbaum P, Zalzstein Y, Ben-Hur T, Levy-Lahad E, Yirmiya R. A dual role for interleukin-1 in hippocampal-dependent memory processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32: 1106–1115, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamasaki MY, Machado MC, Pinheiro da Silva F. Animal models of neuroinflammation secondary to acute insults originated outside the brain. J Neurosci Res 96: 371–378, 2018. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haroon E, Miller AH, Sanacora G. Inflammation, glutamate, and glia: a trio of trouble in mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 42: 193–215, 2017. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng TC, Gelpi E, Halle A, Korte M, Latz E, Golenbock DT. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493: 674–678, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nature11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hepner KA, Watkins KE, Elliott MN, Clemens JQ, Hilton LG, Berry SH. Suicidal ideation among patients with bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Urology 80: 280–285, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh YH, McCartney K, Moore TA, Thundyil J, Gelderblom M, Manzanero S, Arumugam TV. Intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury leads to inflammatory changes in the brain. Shock 36: 424–430, 2011. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182295f91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes FM Jr, Vivar NP, Kennis JG, Pratt-Thomas JD, Lowe DW, Shaner BE, Nietert PJ, Spruill LS, Purves JT. Inflammasomes are important mediators of cyclophosphamide-induced bladder inflammation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F299–F308, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00297.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ismael S, Zhao L, Nasoohi S, Ishrat T. Inhibition of the NLRP3-inflammasome as a potential approach for neuroprotection after stroke. Sci Rep 8: 5971, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24350-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkins S. Guidelines for the Administration of Mesna with Ifosfamide and Cyclophosphamide. London: London Cancer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SH, Lee IC, Ko JW, Moon C, Kim SH, Shin IS, Seo YW, Kim HC, Kim JC. Diallyl disulfide prevents cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis in rats through the inhibition of oxidative damage, MAPKs, and NF-κB pathways. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 23: 180–188, 2015. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koo JW, Duman RS. IL-1β is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 751–756, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708092105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai H, Gardner V, Vetter J, Andriole GL. Correlation between psychological stress levels and the severity of overactive bladder symptoms. BMC Urol 15: 14, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12894-015-0009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, Lee WP, Hoffman HM, Dixit VM. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol 187: 61–70, 2009. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Ramenaden ER, Peng J, Koito H, Volpe JJ, Rosenberg PA. Tumor necrosis factor alpha mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial toxicity to developing oligodendrocytes when astrocytes are present. J Neurosci 28: 5321–5330, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3995-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B, Su M, Tang S, Zhou X, Zhan H, Yang F, Li W, Li T, Xie J. Spinal astrocytic activation contributes to mechanical allodynia in a rat model of cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. Mol Pain pii: 1744806916674479, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1744806916674479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKernan LC, Walsh CG, Reynolds WS, Crofford LJ, Dmochowski RR, Williams DA. Psychosocial co-morbidities in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS): a systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn 37: 926–941, 2018. doi: 10.1002/nau.23421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McTigue DM, Tripathi RB. The life, death, and replacement of oligodendrocytes in the adult CNS. J Neurochem 107: 1–19, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meijlink JM. Bladder pain: the patient perspective. Urologia 84, Suppl 1: 5–7, 2017. doi: 10.5301/uj.5000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menke A. Is the HPA axis as target for depression outdated, or is there a new hope? Front Psychiatry 10: 101, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michaelides A, Zis P. Depression, anxiety and acute pain: links and management challenges. Postgrad Med 131: 438–444, 2019. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1663705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michels M, Vieira AS, Vuolo F, Zapelini HG, Mendonça B, Mina F, Dominguini D, Steckert A, Schuck PF, Quevedo J, Petronilho F, Dal-Pizzol F. The role of microglia activation in the development of sepsis-induced long-term cognitive impairment. Brain Behav Immun 43: 54–59, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller AH. Mechanisms of cytokine-induced behavioral changes: psychoneuroimmunology at the translational interface. Brain Behav Immun 23: 149–158, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 65: 732–741, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol 16: 22–34, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milsom I, Kaplan SA, Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS. Effect of bothersome overactive bladder symptoms on health-related quality of life, anxiety, depression, and treatment seeking in the United States: results from EpiLUTS. Urology 80: 90–96, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muere A, Tripp DA, Nickel JC, Kelly KL, Mayer R, Pontari M, Moldwin R, Carr LK, Yang CC, Nordling J. Depression and coping behaviors are key factors in understanding pain in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Pain Manag Nurs 19: 497–505, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noto C, Rizzo LB, Mansur RB, McIntyre RS, Maes M, Brietzke E. Targeting the inflammatory pathway as a therapeutic tool for major depression. Neuroimmunomodulation 21: 131–139, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000356549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Renard J, Ballarini S, Mascarenhas T, Zahran M, Quimper E, Choucair J, Iselin CE. Recurrent lower urinary tract infections have a detrimental effect on patient quality of life: a prospective, observational study. Infect Dis Ther 4: 125-135, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s40121-014-0054-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sayana P, Colpo GD, Simões LR, Giridharan VV, Teixeira AL, Quevedo J, Barichello T. A systematic review of evidence for the role of inflammatory biomarkers in bipolar patients. J Psychiatr Res 92: 160–182, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwarcz R, Pellicciari R. Manipulation of brain kynurenines: glial targets, neuronal effects, and clinical opportunities. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303: 1–10, 2002. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.034439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silva MT, Alves CR, Santarem EM. Anxiogenic-like effect of acute and chronic fluoxetine on rats tested on the elevated plus-maze. Braz J Med Biol Res 32: 333–339, 1999. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X1999000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song L, Pei L, Yao S, Wu Y, Shang Y. NLRP3 inflammasome in neurological diseases, from functions to therapies. Front Cell Neurosci 11: 63, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szabo G, Csak T. Inflammasomes in liver diseases. J Hepatol 57: 642–654, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor SE. Mechanisms linking early life stress to adult health outcomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 8507–8512, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003890107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teixeira AL, Müller N. Immunology of psychiatric disorders. Neuroimmunomodulation 21: 71, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000356525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tzeng NS, Chang HA, Chung CH, Kao YC, Yeh HW, Yeh CB, Chiang WS, Huang SY, Lu RB, Chien WC. Risk of psychiatric disorders in overactive bladder syndrome: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Investig Med 67: 312-318, 2019. doi: 10.1136/jim-2018-000835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu P, Chen Y, Zhao J, Zhang G, Chen J, Wang J, Zhang H. Urinary microbiome and psychological factors in women with overactive bladder. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7: 488, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu YJ, Muldoon LL, Dickey DT, Lewin SJ, Varallyay CG, Neuwelt EA. Cyclophosphamide enhances human tumor growth in nude rat xenografted tumor models. Neoplasia 11: 187–195, 2009. doi: 10.1593/neo.81352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]