CONSIDERATION OF SEX AS A BIOLOGICAL VARIABLE

There is an increasing literature base reporting sex and gender differences across a wide spectrum of physiological and pathophysiological conditions. This is due, in part, to the 2015 mandate released by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in NIH-Funded Research (NOT-OD-15-102). The mandate states that consideration of sex and gender are needed in all research studies to help inform the development and testing of preventive and therapeutic interventions for both men and women (11). The 11th triennial American Physiological Society/American Society of Nephrology Control of Renal Function in Health and Disease Conference in Charlottesville, VA, included a workshop on sex as a biological variable (SABV) and its importance to scientific research. The purpose of the workshop was to educate and provide insight into the meaning of SABV for conducting biomedical research and the peer review of manuscripts and grants. The workshop included an expert panel of academic researchers whose work focused on understanding how sex impacts biological processes. An important take away from the workshop was that confusion remains as to how to address and best understand SABV in grant applications and manuscripts and how to incorporate SABV into study design. The purpose of this article is to outline several key points from this workshop to aid in understanding how to evaluate SABV in research. This includes a brief discussion of the following: 1) the impact of the NIH SABV notice, 2) the importance of including both sexes in (renal) physiological research, 3) the perceived challenges of including SABV in study design, and 4) suggestions for best practice of consideration of SABV.

Over the last 10 yr, inclusion of women in clinical trials has increased (1); however, preclinical research remains heavily biased toward males. An overreliance on the male sex (XY) in preclinical research has, in part, contributed to failures in clinical trials because they were not properly informed about the impact of sex to differentially regulate biological functions (9). To this end, postmarketing reports found 4 of 10 drugs withdrawn from market by the Federal Drug Administration from 1997 to 2000 caused severe adverse side effects in women (8). The NIH mandate regarding the role of SABV in biomedical research encourages researchers to include the consideration of sex and gender in research questions, study design, data collection and analysis, and reporting (11). As such, the NIH expects inclusion of biological variables (e.g., sex, age, and weight) in grant applications (11). This does not mean that all studies are required to include both sexes in all experiments. Instead, applicants are asked to “consider” SABV. For key studies in which there is a lack of information of the physiology in female subjects, the inclusion of both sexes may be warranted. Furthermore, justification based on strong, primary literature reviews will be expected when only one sex is included in study design.

Now, four years after the NIH SABV policy announcement, has this policy made an impact? Woitowich and Woodruff (17) recently reported an increasing trend from 84% (2016) to 88% (2017) in scientists (ntotal = 1,161) who believe they understand the SABV policy. Furthermore, there was an increase in scientists who agreed that rigor and reproducibility would improve with consideration of SABV (54% vs. 58%) (17). Importantly, grant reviewers reported an increase in both justification of a single sex in study design in grant proposals (44% to 50%, P = 0.0330) and incorporation of SABV reporting into the applicant score (55% to 61%, P = 0.0518) (17). Outside of the United States, funding agencies, such as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the European Commission, have also implemented policies of considering SABV (8). Furthermore, CIHR has successfully developed standardized training on SABV for researchers (5, 8). These worldwide movements to integrate SABV in research are expected to strengthen our understanding of physiology and improve human health care.

IMPORTANCE OF SABV IN RENAL PHYSIOLOGY

Kidney disease is the ninth leading cause of death in women (3a). Chronic kidney disease (CKD) alone affects 195 million women worldwide (5a) and accounts for over 600,000 deaths each year (6). Pregnancy also poses a risk to long-term kidney function in women, as they are particularly susceptible to kidney injury during this time. Women with preeclampsia, or high blood pressure during pregnancy, are at significantly increased risk (5 times) of kidney failure later in life (10). Although kidney disease disproportionally effects women worldwide, women are less likely to have access to adequate treatment (12). As such, sex-specific interventions and treatments are of urgent need. However, a recent study (13a) reported that among top renal physiology journals, less than 15% of animal studies included both sexes. There were five studies conducted solely in male animals to every one study performed in female animals (1).

This is an important problem to remedy because recent preclinical renal physiological data reports sex differences in 11 of 23 renal transporters studied (16). Whole genome microarray gene expression analysis of kidney samples revealed 114 genes that differed in a sex-specific way, including genes for renal necrosis and cell death (16). Both of these studies suggested that fundamental differences between the sexes in normal renal physiology support the need to include female subjects in more studies. These studies also have clinically relevant implications for understanding kidney disease prevalence and progression in both women and men.

CHALLENGES OF CONSIDERATION OF SEX AS A BIOLOGICAL VARIABLE

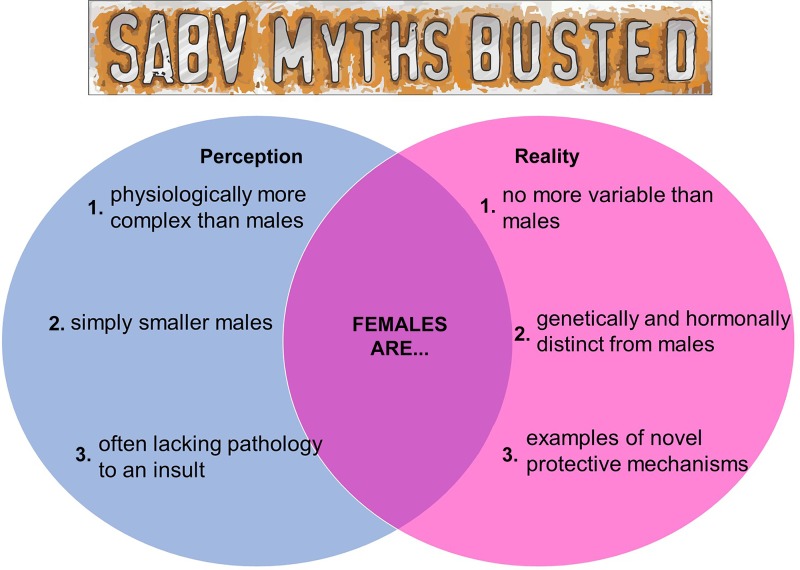

Consideration of sex as a variable is important for a well-designed study, and the meeting workshop highlighted some of the perceived challenges with incorporating SABV. In particular, a primary concern focused on the long-held perception of a more complex female physiology, which is thought to increase study expense and time. It was thought that fluctuations in female sex hormones during the estrous cycle cause greater variability in female subjects, resulting in the need to include even more animals, thus increasing overall expense. Recent studies however, have shown that “women are not more complicated than men, and hormones are not a ‘female problem’ for animal research” (15). While female animals have higher levels of estrogen and progesterone relative to male animals, male animals have higher levels and fluctuations of testosterone (3). Indeed, variability among male subjects is often much greater than it is in female subjects (13).

Second, the workshop revealed the common perception that there is no need to study female subjects because they frequently lack pathology to a particular insult. Workshop participants indicated that researchers often opt for experimental designs with male experimental models only, as they are more likely to give positive results. Some attendees also questioned the importance of including female subjects in studies if the pathology is not present to the same severity as seen in male subjects. However, the expert panel noted that this approach fails to consider the value of discovering novel protective mechanisms in female participants that can be used to better treat both men and women.

A final perceived challenge addressed was the consideration of female subjects simply as “smaller male” subjects. A recent review in Nature Reviews Genetics (7) brought to the foreground sex differences in endogenous (hormones) and exogenous (environmental exposures) factors, genetics, epigenetics, and genome regulation showing that while men and women are similar, they are not the same (see Fig. 1). It is important to recognize that male and female subjects are not the same and consider the impact that sex differences can have in both biomedical research and in human health and disease.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of key myths regarding the use of female subjects in biomedical research.

There are distinct differences between the sexes in numerous physiological and pathophysiological pathways, thus emphasizing the value of studying both male and female subjects. Sex differences exist at every level from DNA methylation patterns and genetic architecture (7) to endocrinology, which can ultimately impact the way one sex responds to a particular intervention. As such, while the consideration of SABV may mean that both sexes should be included in key experiments to determine whether future studies should be designed to examine sex differences, the NIH mandate does not mean that all studies need to be conducted in both sexes.

SUGGESTIONS FOR BEST PRACTICE OF CONSIDERATION OF SABV

While inclusion of SABV in scientific study design is now encouraged by the NIH, there is no standardized method to incorporate SABV into biomedical research, and even fewer requirements for reviewers’ evaluations. The appropriate consideration of SABV for researchers involves inclusion of both male and female groups of animals in a single study and a thoughtful peer review evaluation of SABV to ensure that the mandate is effective.

Best practices for consideration of SABV begins at study design. First, scientists should acknowledge whether their question is relevant to both male and female subjects. If the literature reveals a known sex difference in the pathway being studied, then the researchers must take sex into account when designing their experiments. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that the sexes may respond differently to a treatment. It is equally important to analyze the data separately by sex allowing for the identification of sex-specific effects. Appropriately designed and reported experiments considering SABV can only serve to add to our collective knowledge base and move the field forward.

CONCLUSIONS

Consideration of SABV in biomedical research is increasingly recognized as an important piece of experimental design. For investigators, careful consideration of SABV in study design is critical for enhancing reproducibility and rigor of biomedical research. For reviewers, a comprehensive understanding of SABV is essential in the peer review process for appropriate evaluation of submitted manuscripts and grant applications. SABV does not require researchers to study sex-specific differences but rather encourages them to understand the role that sex could have as a variable in basic scientific studies. Additionally, it is important for researchers and reviewers alike to recognize when and how consideration of SABV is implemented in basic and clinical research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.C.M., S.C.R., M.J.R., and J.C.S. drafted manuscript; E.C.M., S.C.R., M.J.R., and J.C.S. edited and revised manuscript; E.C.M., S.C.R., M.J.R., and J.C.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Greg Sullivan for assistance with the generation of the figure.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bucholz EM, Krumholz HM. Women in clinical research: what we need for progress. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 8, Suppl 1: S1–S3, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention QuickStats: number of deaths from 10 leading causes, by sex−National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66: 413, 2017. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6615a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diatroptov ME. Infradian fluctuations in serum testosterone levels in male laboratory rats. Bull Exp Biol Med 151: 638–641, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s10517-011-1403-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duchesne A, Tannenbaum C, Einstein G. Funding agency mechanisms to increase sex and gender analysis. Lancet 389: 699, 2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Data on chronic kidney disease prevalence and mortality in women. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ [15 January 2020].

- 6.The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Group KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic Kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khramtsova EA, Davis LK, Stranger BE. The role of sex in the genomics of human complex traits. Nat Rev Genet 20: 173–190, 2019. [Erratum in Nat Rev Genet 20: 494, 2019.] doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SK. Sex as an important biological variable in biomedical research. BMB Rep 51: 167–173, 2018. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2018.51.4.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu KA, DiPietro Mager NAD. Women’s involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications. Pharm Pract (Granada) 14: 708, 2016. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes van Balen VA, Spaan JJ, Cornelis T, Spaanderman MEA. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease after preeclampsia. J Nephrol 30: 403–409, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s40620-016-0342-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research Consideration of sex as a biological variable in NIH-funded research https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not-od-15-102.html. [ August 12, 2019].

- 12.Piccoli GB, Alrukhaimi M, Liu Z-H, Zakharova E, Levin A, World Kidney Day Steering Committee . What we do and do not know about women and kidney diseases; questions unanswered and answers unquestioned: reflection on World Kidney Day and International Woman’s Day. BMC Nephrol 19: 66, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-0864-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prendergast BJ, Onishi KG, Zucker I. Female mice liberated for inclusion in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 40: 1–5, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Sandberg K, Pai AV, Maddox T. Sex and rigor: the TGF-beta blood pressure affair. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F1087–F1088, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00381.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shansky RM. Are hormones a “female problem” for animal research? Science 364: 825–826, 2019. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw7570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veiras LC, Girardi ACC, Curry J, Pei L, Ralph DL, Tran A, Castelo-Branco RC, Pastor-Soler N, Arranz CT, Yu ASL, McDonough AA. Sexual dimorphic pattern of renal transporters and electrolyte homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 3504–3517, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017030295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woitowich NC, Woodruff TK. Implementation of the NIH sex-inclusion policy: attitudes and opinions of study section members. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 28: 9–16, 2019. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]