Abstract

Whereas multiple national, international, and trial registries for heart failure have been created, international standards for clinical assessment and outcome measurement do not currently exist. The working group’s objective was to facilitate international comparison in heart failure care, using standardized parameters and meaningful patient-centered outcomes for research and quality of care assessments. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement recruited an international working group of clinical heart failure experts, researchers, and patient representatives to define a standard set of outcomes and risk-adjustment variables. This was designed to document, compare, and ultimately improve patient care outcomes in the heart failure population, with a focus on global feasibility and relevance. The working group employed a Delphi process, patient focus groups, online patient surveys, and multiple systematic publications searches. The process occurred over 10 months, employing 7 international teleconferences. A 17-item set has been established, addressing selected functional, psychosocial, burden of care, and survival outcome domains. These measures were designed to include all patients with heart failure, whether entered at first presentation or subsequent decompensation, excluding cardiogenic shock. Sources include clinician report, administrative data, and validated patient-reported outcome measurement tools: the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; the Patient Health Questionnaire-2; and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Recommended data included those to support risk adjustment and benchmarking across providers and regions. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement developed a dataset designed to capture, compare, and improve care for heart failure, with feasibility and relevance for patients and clinicians worldwide.

Key Words: epidemiology, heart failure, quality and outcomes

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ICHOM, International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure

Central Illustration

Highlights

-

•

ICHOM seeks to help standardize and align outcome measurement efforts globally.

-

•

Standardization and alignment of this sort does not exist for heart failure.

-

•

The heart failure working group developed a standard set of 17 outcomes to be measured.

-

•

ICHOM hopes this standardization effort will increase quality and value in heart failure care.

Cardiovascular diseases are responsible for a significant burden on patients and health care systems worldwide (1,2). Although prevalence estimates in the developing world are largely lacking, heart failure affects up to 2% of the adult population in the developed world, with current estimates over the period of 2002 to 2014 suggesting an absolute increase in heart failure incidence and prevalence (3, 4, 5). Estimates of the annual costs of heart failure treatment in the Unites States alone exceed $30 billion, over one-half of which is due to hospitalization (6). It is therefore fundamental to be able to effectively monitor and manage this disease process.

Major guidelines exist for heart failure management, recommending therapies that affect the course of the disease. However, these guidelines most commonly focus on mortality, hospitalization, or surrogate measures such as change in ejection fraction or ventricular remodeling (6, 7, 8). Though reducing symptoms and increasing functional capacity and quality of life are commonly articulated goals, there is less consensus on how best to achieve these outcomes. Additionally, the many international studies and registries that exist exhibit marked heterogeneity in terms of what is measured and the definitions thereof and tend to neglect patient-reported outcomes (9). This has the effect of limiting international comparison and our understanding of the burden of heart failure on quality of life and physical function.

The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) seeks to promote comprehensive standardized outcome measurement and align outcome measurement efforts globally. To this end, a heart failure working group was formed. The goal of the working group was to define a standard pragmatic patient-centered outcome set to improve patient care and permit comparison across regions and health care systems. The standard outcome set for heart failure is intended to be both a management and a research tool. The goal was to include sufficient detail to be meaningful, while limiting the amount and complexity of collected data to ensure feasibility, considering also cost and time required for set implementation.

Methods

Working group composition and process

An international working group was formed from recognized experts in heart failure, epidemiology, and public health. Allied health professionals, patient advocates, and patient representatives were also included. The primary criterion for being invited to join the working group was expertise in the condition or, in the case of patient representatives, personal experience with heart failure. Working group members were identified through their published work, through ICHOM’s professional network, or through recommendations from experts in the field. The working group lead was a heart failure cardiologist (T.M.) with significant clinical, research, and guideline development experience. A project team was also formed that included a project leader (J.A. then O.O.) as well as a research fellow (D.B.) who managed the process and teleconferences, communicated with the working group, and provided the supporting research efforts underlying each teleconference. Industry representatives were deliberately excluded from the process in line with ICHOM policy to avoid the perception of bias toward any particular product or service offered, though feedback was sought during the final stages by means of an open review period. Regulators and payers were not involved, as these would necessarily vary across countries and health care systems. As the focus of the set was its clinical applicability, emphasis was placed on patients and clinicians. Patient input was sought by means of both a focus group and patient survey administered by the project leader, with heart failure patients representing the United Kingdom, United States, and Brazil. English-speaking heart failure patients were convened by videoconference and questioned as to which outcomes were most meaningful, at what age they were affected, and how daily life was affected by their disease. Patients were surveyed via an online questionnaire regarding agreement with the outcome set capturing the outcomes that have mattered most to them as patients. Comparison between the patient-derived outcome set and the working group–derived clinical outcomes helped inform set development.

Our goal was to define a parsimonious 10- to 15-item set of clinical outcomes that broadly encompassed mortality, morbidity, and patient-reported health-related quality of life. The outcome set was to be adequately comprehensive and sensitive to detect a clinical change, prompting further investigation or treatment escalation, while remaining pragmatic in terms of measurement time and ease of use, being feasible to implement at the primary care level. The set’s use would not preclude collection and reporting of additional data measures beyond those specifically highlighted.

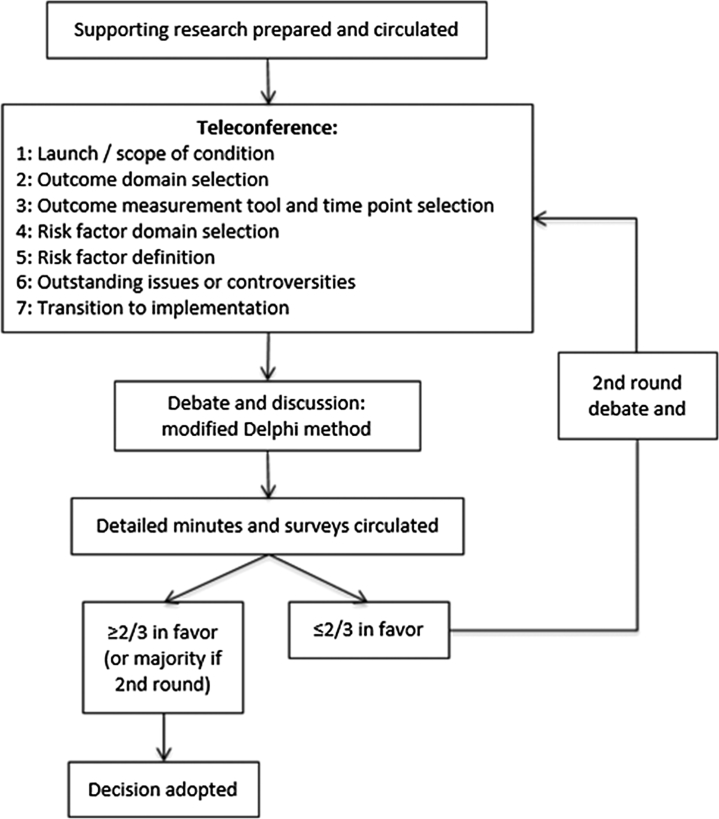

From May 25, 2015, to March 18, 2016, 7 international teleconferences took place (Figure 1). Prior to each teleconference, the project team summarized key evidence sourced from clinical guidelines, relevant scientific publications, and a large initial survey of heart failure registry publications (Table 1). This was circulated to the working group in advance of each teleconference. A modified Delphi method was utilized to achieve consensus on all major aspects of set development.

Figure 1.

Working Group Teleconference Flow Diagram

A flow diagram outlining the decision making process across the 7 teleconferences.

Table 1.

Registries Informing Outcome, Risk-Adjustment Variable, and Complication Domains

| Registry∗ | Region | Publication Date Range | Index Population | Current Population | Presentation | Clinical Setting | Publications Reviewed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHERE | America | 2003–2014 | 27,645 | >185,000 | AHF | I | 31 |

| ADHERE-I | Asia-Pacific and Latin America | 2011–2012 | 4,206 | 10,171 | AHF | I | 3 |

| AHEAD | Czech Republic | 2011–2015 | 4,153 | 5,057 | AHF | I | 7 |

| ALARM-HF | Europe, Latin America, Australia | 2010–2014 | 4,953 | 4,953 | AHF | I | 5 |

| ASIAN-HF | North, East, and South Asia | 2012–2016 | 6,480 | 6,480 | CHF | I/O | 2 |

| ATTEND | Japan | 2010–2015 | 1,110 | 4,842 | AHF | I | 14 |

| COHERE | America | 2000–2007 | 4,280 | 4,280 | ChHF | O | 7 |

| EFICA | France | 2006–2010 | 581 | 581 | AHF | I | 4 |

| EHFS II | European Union | 2006–2010 | 3,580 | 3,580 | AHF | I | 3 |

| ESC-HF-LT | European Union | 2010–2013 | 12,440 | 12,440 | A/ChHF | I/O | 1 |

| ESC-HF-P | European Union | 2010–2013 | 5,118 | 5,118 | A/ChHF | I/O | 3 |

| GWTG-HF | America | 2006–2015 | 59,965 | 65,032 | AHF | I | 55 |

| HIJC-HF | Japan | 2008 | 3,578 | 3,578 | AHF | I | 1 |

| IMPACT-HF | America | 2002–2005 | 363 | 567 | AHF | I | 5 |

| IMPROVE-HF | America | 2007–2014 | 15,381 | 15,177 | ChHF | O | 13 |

| IN-HF | Italy | 2012–2014 | 5,610 | 5,610 | A/ChHF | I/O | 5 |

| JCARE | Japan | 2006–2014 | 2,676 | 1,677 | AHF | I | 18 |

| KorHF | Korea | 2011–2015 | 3,200 | 3,200 | AHF | I | 10 |

| NICOR | United Kingdom | NR | NR | >200,000 | AHF | I | 0 |

| OPTIMIZE-HF | America | 2004–2014 | 48,612 | 48,612 | AHF | I | 32 |

| RO-AHFS | Romania | 2011–2015 | 3,224 | 3,224 | AHF | I | 4 |

| S-HFR | Sweden | 2010–2015 | 16,117 | 55,313 | A/ChHF | I/O | 14 |

| Thai-ADHERE | Thailand | 2010–2013 | 1,612 | 1,671 | AHF | I | 2 |

| THESUS-HF | Sub-Saharan Africa | 2012–2015 | 1,006 | 1,006 | AHF | I | 5 |

AHF = acute heart failure; ChHF = chronic heart failure; I = inpatient; O = outpatient; NR = not reported.

For detailed information and references by registry, please see the Online Table S1 and Online Appendix.

The working group considered the following criteria when selecting outcomes for inclusion: frequency of occurrence for the outcome of interest; the impact of a change in outcome on the patient; outcome modification potential; the feasibility of data collection at the primary care level; how meaningful the outcome is as reported by survey or focus group patients; and the cost to patients or health care systems. For patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) tools, additional criteria were considered: domains of interest covered; clinical interpretation of a change detected by the PROM tool; comparison of the PROM tool to others in current use; and the feasibility of the tool’s implementation at the primary care level. Time points for data collection were defined for baseline patient characteristics, PROM, and clinician-reported outcomes. A set of risk adjustment variables was proposed that included risk factors shown to affect the clinical course of the heart failure patient, composed of both demographic and health-related factors. Evidence-based treatment variables affecting the course of illness and quality of life were discussed and included as well, as accurate placement of a patient’s disease trajectory requires information about therapies applied.

Following each teleconference, detailed minutes were circulated along with a survey including each specific discussion point. A two-thirds threshold was required to adopt a decision, which would be formally ratified at the subsequent teleconference. If two-thirds was not reached, further discussion was undertaken at the start of the following teleconference with a second survey on these topics circulated, with a majority decision adopted if two-thirds was still not achieved.

Members of the working group and project team unanimously approved the final standard set and accompanying data collection reference guide. Funding for this project was provided in part by the British Heart Foundation, American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, and Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Several members of our working group are actively involved these and other societies. However, this project and its results have not been formally endorsed by said societies.

As new evidence for heart failure management emerges, this set will ultimately require revision to remain in line with the evolving evidence base as well as clinical guidelines. To this end, ICHOM will implement a steering committee to oversee ongoing revisions in line with new evidence.

Results

Condition scope

The working group defined a broad scope as it applies to heart failure. Consistent with major guidelines, patients would be diagnosed as having heart failure if they had clinically identified heart failure signs and symptoms and objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction (6, 7, 8). All patients with the diagnosis of heart failure would be included, whether presenting acutely or chronically, regardless of etiology, and across the spectrum of ejection fraction. Acute heart failure was classified as either an acute first presentation or as an acute decompensation of chronic heart failure, whether or not it resulted in a hospital admission.

Patients with a first presentation as cardiogenic shock were excluded from the scope, as there is often a distinct upstream precipitating factor, which requires urgent or emergent intervention. As such, the patient does not fit in with the typical management pattern for the general heart failure population. However, patients surviving the initial event, with or without aggressive medical or surgical intervention, and continuing to be in heart failure, would be included after stabilization. Similarly, patients with coronary or valvular disease may fit the scope if presenting with objective signs of ventricular dysfunction in the absence of immediately correctable causes such as active ischemia. Patients with heart failure who had undergone transplant or mechanical assistance were considered outside the scope. These populations present unique treatment challenges not concordant with the majority of heart failure patients. The scope did not include patients with isolated right heart failure.

Treatment variables

Treatments included for measurement and recording reflect the recommendations of major evidence-based guidelines. These therapies are known to affect mortality, hospitalization, quality of life, or a combination of these in the heart failure patient (6,8). Broadly, these can be divided into pharmacotherapy, invasive therapies, and rehabilitation. Pharmacotherapy includes all heart failure medications at baseline and any changes made to the therapeutic regime over time. Invasive therapies include devices such as pacemakers, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, and cardiac resynchronization therapy, as well as cardiac surgery. Cardiac rehabilitation program initiation was included to complete the treatment options available (Online Table S1). Treatment variables will be captured through the patient’s medical record. Ongoing treatment variable modifications will be overseen by the ICHOM steering committee in line with emerging evidence.

Outcome set

To inform the development of the outcome set and understand real world heart failure outcome measurement efforts, the project team compiled information sourced from 24 heart failure registries. Ultimately, 241 discrete publications were surveyed (Table 1). This phase documented outcome domains, definitions, and ascertainment methods. Registries predominantly focused on acute hospitalizations. Only a single registry included validated PROM tools (10,11). Detailed registry and reference information can be found in the Online Appendix and Online Table S3.

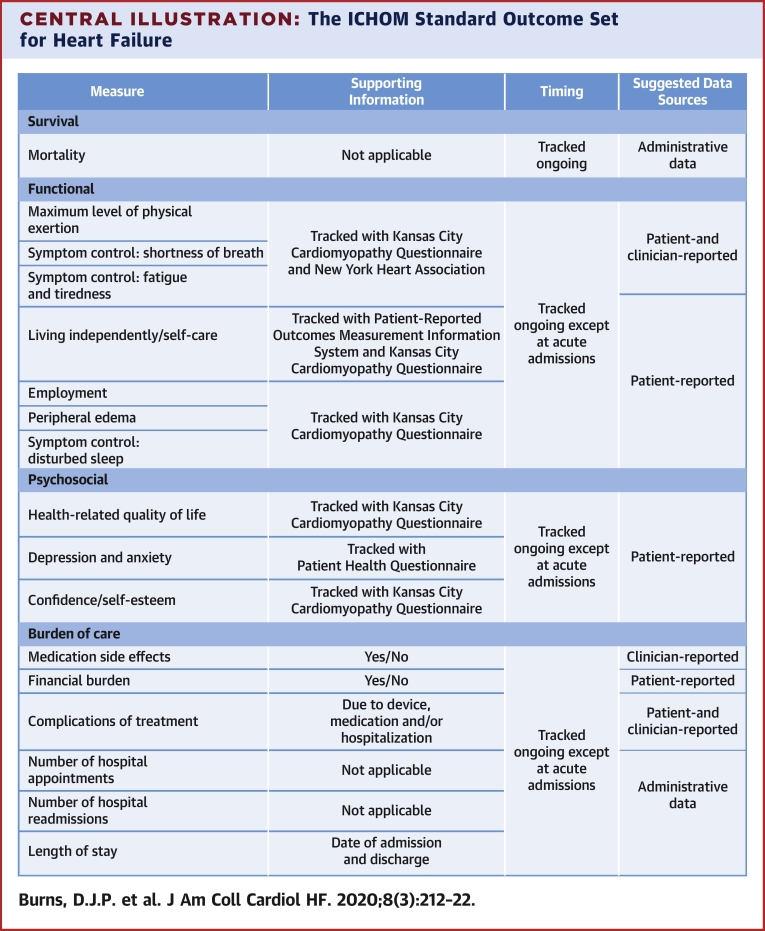

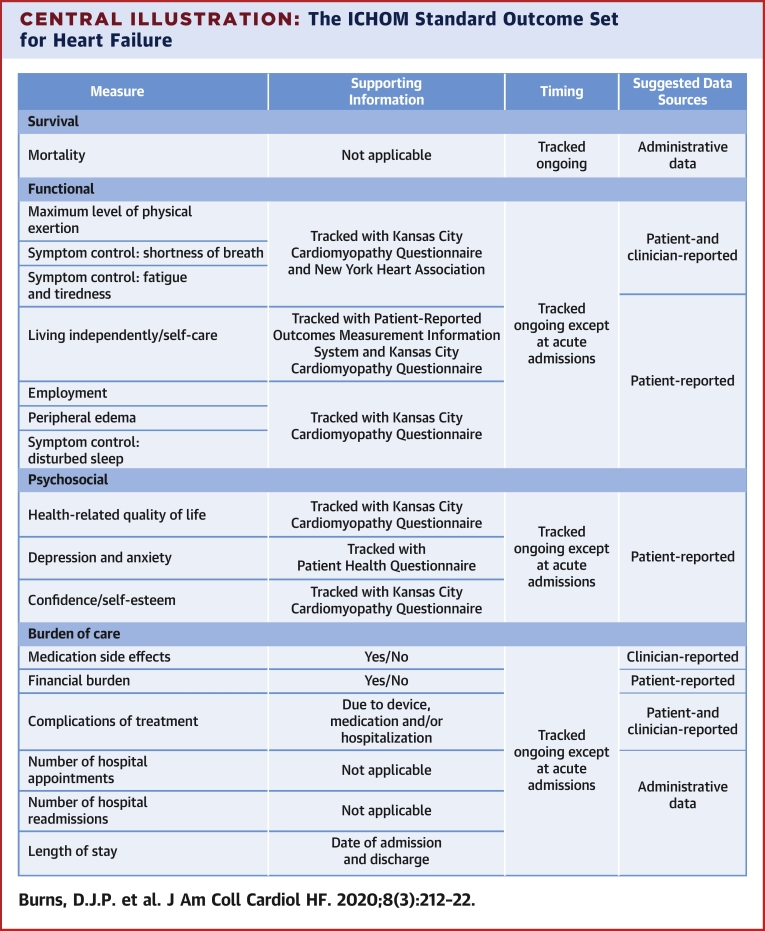

The final outcome set includes 17 outcomes, reflecting 4 domains: functional; psychosocial; burden of care; and survival (Central Illustration). Institutions implementing the outcome set will collect data from hospital, clinician, and patient medical records; patient self-report; and administrative sources. All-cause mortality was chosen, as disease-specific mortality is more difficult to accurately capture and is less meaningful to the individual patient.

Central Illustration.

The ICHOM Standard Outcome Set for Heart Failure

List of outcomes included in the heart failure standard set. ICHOM = International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement; KCCQ-12 = Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; N/A = not applicable; NYHA = New York Heart Association; PHQ-2 = Patient Health Questionnaire; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SOB = shortness of breath.

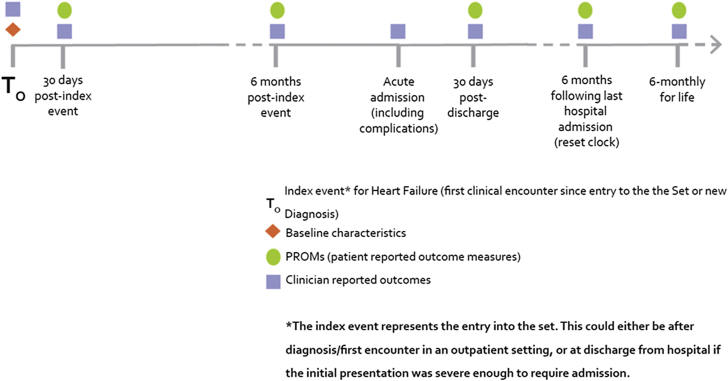

The working group recommends collection of baseline data and clinician-reported outcomes at the time of the index encounter defining entry into the set (T0). T0 would be the date of hospital discharge if the patient’s diagnosis was the result of a hospital admission, as this would be the point defining an ambulatory heart failure patient. PROM and clinician-reported measures should then be documented at 30 days (T30). These would both be repeated at 6 months following T0. In the case of an unexpected acute event, decompensation, or hospitalization (Tn), clinician-reported outcomes only would be measured, with both clinician-reported outcomes and PROM resuming at 30 days and 6 months following Tn. Again, discharge would be the ideal measurement point if the event led to a hospitalization. Once a patient achieves stable follow-up, clinician-reported outcomes and PROM would be recorded every 6 months for life. A sample timeline can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sample Timeline for Outcome Measurement

Follow-up chronology from entry into the outcome set, including variables to be measured at each time point. PROM = patient-reported outcome measure.

Administrative and hospital data, including survival, would be collected at all time points. Given the frequency of patient assessment, all complications, admissions, and mortality should be attainable in a timely fashion and limit loss to follow-up. Patient-reported outcomes are not expected to be captured at the time of a decompensation. Following such a decompensation, the standard set will capture that there has been an abrupt decline in functional capacity, an unplanned visit or readmission with duration, and subsequent modifications to treatment (Figure 2). As the site following the ambulatory heart failure patient will likely differ from an acute care setting, it is unrealistic to expect a formal PROM tool administration. PROM tools would be administered at subsequent planned visits to ensure that a pre-decompensation baseline has been achieved.

Biomarker measurements such as serum sodium and natriuretic peptides were considered, but were ultimately felt to be beyond the pragmatic nature of the proposed outcome set. Though used in diagnosis and monitoring treatment response, we felt these were more appropriate as further testing prompted by a change in the patient’s clinical condition as reflected in the 17-item outcome set, rather than included in the set itself. As stated previously, collection of such data in addition is not precluded.

PROM

To meaningfully characterize patient health-related quality of life within the functional and psychosocial domains, the working group recommends validated PROM assessment tools, standardizing outcome assessment for self-report beyond that captured by generic quality of life questioning. A comprehensive 2009 review undertaken by the University of Oxford Department of Public Health thoroughly evaluated the major heart failure–specific tools in use (12). We evaluated 3 primary PROM assessment tools: the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ); the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ); and the Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire (13, 14, 15). The KCCQ and the MLHFQ are the most commonly used PROM in heart failure, and both have been validated and widely studied. Details regarding the validity, reliability, and responsiveness of each tool have been included in the Online Table S4.

Which PROM tool to recommend was controversial. For technical quality, all 3 tools score highly in terms of validity, reliability, and responsiveness. The Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire requires a trained interviewer, which represents a substantial barrier to implementation. Both the KCCQ and MLHFQ address the majority of proposed domains, and there was little to distinguish each tool based on technical quality. To better evaluate each tool, we used the Evaluating the Measurement of Patient-Reported Outcomes scoring tool (16). With Evaluating the Measurement of Patient-Reported Outcomes, the KCCQ scored noticeably higher in validity, sensitivity to change, and interpretability; the MLFHQ scored higher in reliability and burden (17). The KCCQ was ultimately selected given its ability to detect and interpret score change (18). To maximize efficiency in administration and decrease overall collection time, the shortened KCCQ-12 was ultimately included. This short-form tool has been shown to preserve the favorable parameters of the original instrument (19). Information on licensing the KCCQ-12 is provided with the accompanying reference guide, and a sample KCCQ-12 has been included in the Online Appendix. In addition to the KCCQ-12, we recommend the use of the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification to help characterize appropriate outcomes in the “functional” domain (Central Illustration).

To supplement the KCCQ-12, the working group recommends the use of 2 measure-specific PROM: the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Physical Function Short Form 4a and the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 for depression and anxiety (20,21). The tools serve to capture certain subtleties not captured by the KCCQ-12, such as physical capability, self-care, and mental health. The EQ-5D tool was initially proposed (22). However, when comparing our proposed outcome set with those outcomes covered by the above-mentioned disease-specific PROM, the EQ-5D did not add any additional information. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System is a free collection of rigorously reviewed and tested validated outcome measures. The Physical Function Short Form 4a measures self-reported capability of physical activities, including dexterity, walking or mobility, central mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 is a validated 2-item tool with a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 92% for major depression when scoring ≥3 (23). Detailed information on the specific questions within these tools can be found in the Online Appendix, and links to each are published in the accompanying reference guide. PROM assessment tools have been heavily relied on, with several shortened PROM tools being recommended. Using these tools, total data collection time is approximately 15 min.

Complications

Covered under the burden of care domain, all pharmacotherapy and device therapy may result in treatment-related complications, significantly affecting a patient’s quality of life. It is important to document the time and severity of each occurrence, as well as interventions performed to address each complication. Complications were considered related to hospitalization, heart failure medications, or device placement. Recommended complications to be documented are included in the Online Appendix.

Case-mix adjustment

As robust risk adjustment models require accounting for differences in case-mix across regions and health care systems, the working group defined a set of adjustment variables (Table 2). These are factors shown to affect the course of the heart failure patient and include both demographic and health-related factors. To support the selection of these factors, major heart failure registries and clinical guidelines were searched for variables associated with the course of the patient’s illness. The results of this survey, with relevant citations, have been included in the Online Appendix. Recognizing that different international regions will have different dominant heart failure etiologies, we have included underlying etiology in line with current clinical practice guidelines (6). Variable definitions, as applicable, were identified from major health-related publications, operational definitions, or clinical practice guidelines (Online Table S8). Hyperlipidemia was not included given inconsistent evidence and a lack of working group consensus. Left ventricular ejection fraction was included due to it being a common marker of cardiac function, distinguishing heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Steps were also taken to align variable definitions between the heart failure set and the related ICHOM coronary artery disease standard set (24).

Table 2.

Risk-Adjustment Variables

| Measure∗ | Supporting Information | Timing | Suggested Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | |||

| Age | Date of birth | At index event for HF | Administrative data |

| Sex | Sex at birth | ||

| Ethnicity | Note that regulations on reporting ethnicity may differ per country | ||

| Baseline health status | |||

| Hypertension | Yes or no | At index event for HF | Clinician-reported |

| Diabetes | |||

| Renal dysfunction | Serum creatinine, need for dialysis | ||

| Smoking status (current or in past year) | Yes or no | ||

| Alcohol use (>1 drink a day) | |||

| Prior MI | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | |||

| Chronic lung disease | Oxygen dependency | ||

| Body mass index | Height and weight | ||

| Ejection fraction | Determined by echocardiogram† | ||

| Underlying etiology | As diagnosed | ||

HF = heart failure; MI = myocardial infarction; N/A = not applicable.

Measure definitions can be found in the accompanying Online Appendix Section S8.

Echocardiogram is recommended, though ejection fraction can be determined by other methods.

In the selection of case-mix adjustment variables, socioeconomic variables are important factors to consider when assessing outcomes in heart failure patients (25). Whereas there was general agreement that the inclusion of socioeconomic variables would be beneficial, the working group was unable to reach consensus regarding which specific measures to include or which parameter(s) would be ideal. Also of concern was how to reconcile socioeconomic variables across countries and regions, which may have vastly different baselines and relative understandings of higher versus lower socioeconomic status. The list of adjustment variables was necessarily pragmatic to allow meaningful comparisons of standardized outcome measures across institutions, regions, and health care systems. The list is intended to serve as a starting point in building international risk-adjustment models in the heart failure population.

Discussion

The ICHOM heart failure working group defined a consensus standard set of treatment, outcome, and adjustment variables to be measured within the heart failure patient population, with a view toward care quality and standardization. It is our hope that this will contribute to the establishment of robust risk-adjustment models for patient-reported outcomes and permit comparison of the intensity, challenges, and outcomes of heart failure care across international boundaries. The development of the set was an international collaboration, involving 24 members and a project leader, across 12 countries and 6 continents. The working group included clinical leaders, researchers, and patient representatives. To our knowledge this is the first and largest collaboration of its kind.

A major component of this set’s development was surveying registry data to establish what measurement efforts are currently being undertaken by health care and research teams. The focus and structure of existing national and international heart failure registries limit the extent to which longitudinal patient-centered outcomes can be measured and compared. Most registries focus on inpatient populations, short-term mortality, and rehospitalization; patient health status is often overlooked or not clearly defined and standardized (9). Without this consideration, complete estimates of value, as determined by outcomes relative to the cost of care, cannot be determined (26). In addition, recorded outcomes are not standardized among registries. These limitations affect efforts to understand the patient’s perspective and to compare heart failure care processes internationally. Our goal included focusing on what mattered most to patients and is unique in that patient focus groups and interviews actively informed the development of the outcome set. In addition, we rely heavily on PROM assessment tools to obtain validated, reproducible, and meaningful assessments of the many domains of health status, adding additional depth and consistency beyond unstructured patient self-report. Finally, by specifying routine follow-up intervals for health status assessment, we hope to be able to capture multiple repeat measures and trends with respect to long-term outcomes.

Standardizing outcome measurement allows comparison across regions by enabling groups to “speak the same language” when comparing outcome measures. By specifying common measures and definitions, variability and systematic error between sample populations should be decreased. By specifying exact coding practices in the accompanying data collection reference guide, we hope to facilitate cross-region collaboration when tracking heart failure outcomes. Without case-mix adjustment, outcomes between differing populations may not be directly comparable. These additional measures allow us to draw more meaningful conclusions when comparing unique populations.

An important aspect of this project is the standardization of heart failure outcome measurement across differing regions and health care systems. To achieve this, we have published a comprehensive data collection reference guide summarizing the set, outcome reporting tools, adjustment variables, and collection time points (27). This guide includes a by-variable data collection and coding reference, further reducing variability in outcome reporting between centers. The reference guide has been included as a Online Appendix, and is also available from the ICHOM website (28).

The final stage of this project is to promote implementation of the standard set. Major hurdles to be overcome include the following: 1) budgeting; 2) local or regional agreement of clinicians willing to use the set; 3) ongoing evaluation and gap- analysis of what is and is not being measured or recorded; 4) ensuring efficient and user-friendly means of collecting and storing clinical data; and 5) ensuring systematic and consistent collection of PROM data. Heart failure patients may be followed by a number of clinicians or centers, requiring necessary communication between treating centers, which may prove challenging. The inflection point for feasibility may have arrived with the wider implementation of standardized electronic health records into which patients now routinely answer functional questionnaires before new and return appointments. Though several data sources and PROM tools are required, utilizing multiple shortened assessment tools has resulted in a data collection time of only 15 min. We recognize that implementation is not a simple task. In the short term, we are planning pilot implementation under leadership from working group members. Using the results of these projects, ICHOM plans to grow in a stepwise fashion toward broader implementation of this set.

Pilot implementation of this outcome set is being conducted in 13 Brazilian hospitals, coordinated by the Brazilian National Hospital Association, including >1,000 patients from January 2017 to present. The main metrics for determining pilot success are follow-up rate (>70%), absence of missing data (<10%), and accuracy (>90%). Hospitals are free to define their data collection instrument, ranging from spreadsheets to integrated electronic data records. PROM are collected by telephone contact, surveys, e-mail, and in-person visits. The implementation experience, in terms of process, performance, and benchmarking, has been examined and is currently being prepared for publication.

This outcome measurement set must be interpreted and implemented in the context of several limitations. The working group was unable to reach consensus regarding measures of socioeconomic status, an important consideration when considering outcomes in patients with heart failure (25). Populations informing the development of the set tended to be “Western” with the largest contributions from North America and Europe. Asia was broadly represented, though the Middle East was notably absent. No registry included a dedicated South American population. A single registry focused on Africa. Though standardization of outcome measurement can facilitate cross-region comparisons, the standard set may be biased toward Western patient populations given the above-mentioned points.

Every effort was made to recruit an internationally representative working group. Pragmatic considerations prevented representation from every potential region. The working group reflects the geographic distribution of current measurement efforts. The final composition of the group was determined by the positive responses to our invitation. Similarly, due to logistic constraints, patients surveyed for focus groups were not globally representative in terms of distribution and heart failure etiology.

With cooperation and leadership from working group members, ICHOM has partnered with sites in Europe, the Americas, and Asia to pilot and benchmark the implementation of the standard set. From here we hope to build toward a more generalized adoption of the set. Over time, we hope to be able to identify gaps in treatment and improve quality of care worldwide.

Footnotes

Funding for this project was obtained from generous support by the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, British Heart Foundation, American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, and Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Arora is currently affiliated with Medtronic. Dr. Beltrame has received research grants from Servier Laboratories, AstraZeneca, and Biotronics. Dr. Crespo-Leiro has received advisory board honoraria, educational fees, and institutional research support from Novartis; research support from Federación Española de Asociaciones de Enfermedades Rares; travel grants from Vifor Pharma and Servier; and personal fees from Novartis, Abbott Vascular, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, and Astellas. Dr. Filippatos has received research support from Bayer, Novartis, Servier, Vifor Pharma, and Medtronic. Dr. Hardman has received an institutional research grant from The Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development–European Commission: Research and Innovation. Dr. Jessup is a member of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Guidelines writing committee. Dr. Lam is supported by a Clinician Scientist Award from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore; has received research support from Boston Scientific, Bayer, Roche Diagnostics, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, and Vifor Pharma; has served as a consultant for or on the Advisory Board, Steering Committee, or Executive Committee of Boston Scientific, Bayer, Roche Diagnostics, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Vifor Pharma, Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Janssen Research and Development LLC, Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Abbott Diagnostics, Corvia, Stealth BioTherapeutics, JanaCare, Biofourmis, Darma, Applied Therapeutics, WebMD Global LLC, and Radcliffe Group Ltd. Dr. Masoudi is the American College of Cardiology Chief Medical Officer of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry programs. Dr. McIntyre has received consulting and advisory fees and travel expenses from Bayer, Novartis Pharma, Vifor Pharma, and Servier; and research support from Bayer. Dr. Mindham is a patient representative for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2010 Chronic Heart Failure Guidelines. Dr. Stevenson has received research support from St. Jude Medical and Novartis; and consulting fees from St. Jude Medical. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Appendix

For supplemental information and references, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/148114 Available at:

- 2.Mendis S., Puska P., Norrving B., editors. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosterd A., Hoes A.W. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart. 2007;93:1137–1146. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.025270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conrad N., Judge A., Tran J. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet. 2017;391:572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zannad F. Rising incidence of heart failure demands action. Lancet. 2017;391:518–519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yancy C.W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKelvie R.S., Moe G.W., Ezekowitz J.A. The 2012 Canadian Cardiovascular Society heart failure management guidelines update: focus on acute and chronic heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:168–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponikowski P., Voors A.A., Anker S.D. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambrosy A.P., Fonarow G.C., Butler J., for the Task Force Members and Document Reviewers The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam C.S.P., Anand I., Zhang S. Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure (ASIAN-HF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:928–936. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam C.S.P., Teng T.-H.K., Tay W.T. Regional and ethnic differences among patients with heart failure in Asia: the Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure registry. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3141–3153. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackintosh A., Gibbons E., Fitzpatrick R., editors. A Structured Review of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for People With Heart Failure: An Update 2009. University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green C.P., Porter C.B., Bresnahan D.R., Spertus J.A. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rector T., Kubo S., Cohn J. Patients’ self-assessment of their congestive heart failure: part 2: content, reliability and validity of a new measure, the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. Heart Fail. 1987;3:198–209. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt G.H., Nogradi S., Halcrow S., Singer J., Sullivan M.J., Fallen E.L. Development and testing of a new measure of health status for clinical trials in heart failure. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:101–107. doi: 10.1007/BF02602348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valderas J.M., Ferrer M., Mendívil J., for the Scientific Committee on Patient-Reported Outcomes of the IRYSS Network Development of EMPRO: a tool for the standardized assessment of patient-reported outcome measures. Value Health. 2008;11:700–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garin O., Ferrer M., Pont À. Disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires for heart failure: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:71–85. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9416-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garin O., Herdman M., Vilagut G. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: a systematic, standardized comparison of available measures. Heart Fail Rev. 2014;19:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s10741-013-9394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spertus J.A., Jones P.G. Development and validation of a short version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:469–476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Measures Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/obtain-administer-measures Available at:

- 21.Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) https://phqscreeners.com Available at:

- 22.EuroQol EQ-5D. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments Available at:

- 23.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNamara R.L., Spatz E.S., Kelley T.A. Standardized outcome measurement for patients with coronary artery disease: consensus from the international consortium for health outcomes measurement (ICHOM) J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Díaz-Toro F., Verdejo H.E., Castro P.F. Socioeconomic inequalities in heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2015;11:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter M.E. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2477–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement . ICHOM; Boston, MA: 2016. Heart Failure Data Collection Reference Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement Heart Failure: The Standard Set. http://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/heart-failure Available at: Accessed November 19, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.