Abstract

Background

Babies with breech presentation (bottom first) are at increased risk of complications during birth, and are often delivered by caesarean section. The chance of breech presentation persisting at the time of delivery, and the risk of caesarean section, can be reduced by external cephalic version (ECV ‐ turning the baby by manual manipulation through the mother's abdomen). It is also possible that maternal posture may influence fetal position. Many postural techniques have been used to promote cephalic version.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of postural management of breech presentation on measures of pregnancy outcome. We evaluated procedures in which the mother rests with her pelvis elevated. These include the knee‐chest position, and a supine position with the pelvis elevated with a wedge‐shaped cushion.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (22 August 2012).

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials comparing postural management with pelvic elevation for breech presentation, with a control group.

Data collection and analysis

One or both review authors assessed eligibility and trial quality.

Main results

We have included six studies involving a total of 417 women. The rates for non‐cephalic births, Cesarean section and Apgar scores below 7 at one minute, regardless of whether ECV was attempted or not, were similar between the intervention and control groups (risk ratio (RR) 0.98; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84 to 1.15; RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.37; RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.55).

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence from well‐controlled trials to support the use of postural management for breech presentation. The numbers of women studied to date remain relatively small. Further research is needed.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Breech Presentation; Cesarean Section; Cesarean Section/statistics & numerical data; Confidence Intervals; Patient Positioning; Patient Positioning/methods; Posture; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Version, Fetal; Version, Fetal/methods

Plain language summary

Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation

There is currently not enough evidence for encouraging the mother to adopt different postures during pregnancy in order to change a breech baby's position in the womb.

Babies born in the breech position (bottom first) are more likely to have problems during birth than babies born head first (cephalic). There are different ways of trying to encourage the baby to turn so that he/she can be born head first. Some of these involve the mother adopting different postures. This review of six trials, involving 417 women, found too little evidence to support the use of certain postures to change the baby's position in pregnancy to head down. Further research is required.

Background

Babies with breech presentation (bottom first) are at increased risk of complications during birth. This risk can be reduced by planned caesarean section (Hofmeyr 2003). The chance of breech presentation persisting at the time of delivery, and the risk of caesarean section, can be reduced by external cephalic version (ECV ‐ turning the baby by manual manipulation through the mother's abdomen) (Hofmeyr 1996). Other methods used to attempt to correct the position of the baby include acupuncture, homoeopathy and postural methods. Over the years many postural techniques have been used by midwives, doctors and traditional birth attendants to promote cephalic version (Hofmeyr 1989). Little, however, has appeared in the medical literature on this subject. Elkins 1982 reported an uncontrolled trial of the knee‐chest position, assumed for 15 minutes every two hours of waking for five days. Use of this procedure in 71 women with ultrasound‐confirmed breech presentation after 37 weeks' gestation was followed by a normal cephalic birth in 65 cases. This method has been modified by researchers (e.g. knee‐chest position assumed with full urinary bladder three times a day for seven days) (Chenia 1987). Another postural method is 'Indian version', assuming the supine, head‐down position with the pelvis supported by a wedge‐shaped cushion for 10 to 15 minutes once or twice a day (Bung 1987).

Objectives

To assess the effects on presentation at and method of delivery, and perinatal morbidity and mortality, of postural management for breech presentation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing the effects of postural management with pelvic elevation for breech presentation on clinically meaningful outcomes, with a control group (no treatment); random or quasi‐random allocation to a treatment and control group; violations of allocated management and exclusions after allocation not sufficient to materially affect outcomes.

Types of participants

Women with singleton breech presentation.

Types of interventions

Postural management entailing relaxation with the pelvis in an elevated position.

Types of outcome measures

We have included outcome data if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; missing data were insufficient to materially influence conclusions; data were available for analysis according to original allocation, irrespective of protocol violations; and data were available in a format suitable for analysis.

Primary outcomes

Non‐cephalic birth

Caesarean section

Secondary outcomes

Apgar score less than seven at one minute

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

Poor perinatal outcome as defined by trial authors

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (22 August 2012).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the 2010 update, we used the following methods when assessing the trial identified by the updated search (Founds 2006). For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in earlier versions of this review, seeAppendix 1.

Selection of studies

GJ Hofmeyr (GJH) (first review author) and T Lawrie (TL) (seeAcknowledgements) independently assessed for inclusion the study identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For the eligible study, GJH and TL extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion and, if required, would have consulted R Kulier (RK). We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked them for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

GJH and TL independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). We resolved any disagreement by discussion and, if required, would have consulted RK.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator),

high risk (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number) or,

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk, high risk or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low risk, high risk or unclear risk of bias for personnel;

low risk, high risk or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. We assessed methods as:

low risk;

high risk;

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

high risk (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

high risk;

low risk;

unclear risk of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2009). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as a summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

We analysed no continuous data for this review. In future updates of this review, if more data become available, we will analyse continuous data using the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in this update. In future updates, if we identify any cluster‐randomised trials, they will be included in the analyses along with the individually randomised trials, following the guidelines described in the Handbook (Section 16.3.4 and 16.3.6). We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity and subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Crossover trials

We have not included crossover trials.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis. For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if T² was greater than zero and either I² was greater than 30% or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates of this review, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually, and use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If we detect asymmetry in any of these tests, or by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and we judged the trials’ populations and methods to be sufficiently similar. If there had been clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if we had detected substantial statistical heterogeneity, we would have used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials had been considered clinically meaningful. We would have treated the random‐effects summary as the average range of possible treatment effects and we would have discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect had not been clinically meaningful we would not have combined trials. If we had used random‐effects analyses, the results would have been presented as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If, in future updates of this review, we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will also consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses:

no external cephalic version attempted;

external cephalic version attempted.

We used only primary outcomes in subgroup analyses.

For fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analyses we assessed differences between subgroups by interaction tests. For random‐effects and fixed‐effects meta‐analyses using methods other than inverse variance, we assessed differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicated a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We would have performed sensitivity analyses for aspects of the review that could have the results; for example, where there had been a risk of bias associated with the quality of some of the included trials. These will be carried out in future updates of this review, as required.

Results

Description of studies

See table of Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

See table of Characteristics of included studies, particularly the 'Methods' and 'Notes' sections.

Chenia 1987 modified Elkins's procedure to be used three times a day for seven days with a full urinary bladder. Seventy‐six black women with breech presentation beyond 37 weeks' gestation were allocated by randomised sealed envelope to a study and a control group.

Bung 1987 reported a controlled trial of 'Indian' version. The women were encouraged to lie down once or twice a day for 10 to 15 minutes in the supine, head‐down position, the pelvis being supported by a wedge‐shaped cushion. Sixty‐one women with breech presentation between the 30th and 35th weeks of pregnancy were allocated according to odd and even days of the month to a study and a control group.

Hartadottir 1992 'randomised' women with breech presentation after 34 weeks' gestation to a group taught to assume the knee‐chest position for 15 minutes twice a day, or to a control group. There were three exclusions after randomisation, and compliance was poor in some women.

Obwegeser 1999 randomly allocated 109 women to an 'Indian version' or control group, but six left the clinic (lost to follow‐up) and three were withdrawn for poor compliance.

Smith 1999 evaluated the knee‐chest position, and differed from the others in that external cephalic version was offered to the women if the breech presentation persisted after a week (47/51 in the postural group, 44/49 in the control group). This may have obscured the effect of the procedure to some extent. For this reason, we have performed sub‐group analysis for trials with and without external cephalic version (ECV) attempt. ECV was successful in one of the postural group and four of the control group (Smith 1999).

Founds 2006 randomised women with singleton breech presentation between 34 and 38 weeks to a group taught to assume the maternal knee‐chest position for 15 minutes three times daily, or to a control group. There were two protocol deviations in the study group and one woman was lost to follow‐up. We applied an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

In other respects, the studies were methodologically sound. Double blinding was not possible, but the measures of outcome other than Apgar score were not subject to observer bias. The results may, however, have been affected by a chance preponderance of primigravid women in the experimental group in four studies: 11/39 versus 4/37 (Chenia 1987), 15/30 versus 11/31 (Bung 1987), 19/30 versus 13/25 (Hartadottir 1992) and 9/14 versus 4/11 (Founds 2006).

Because the basic principle of the two techniques investigated is similar, namely relaxation in a position in which the pelvis is elevated above the level of the shoulders, the findings of the studies have been combined. It should, however, be noted that the gestation at enrolment differed between the studies.

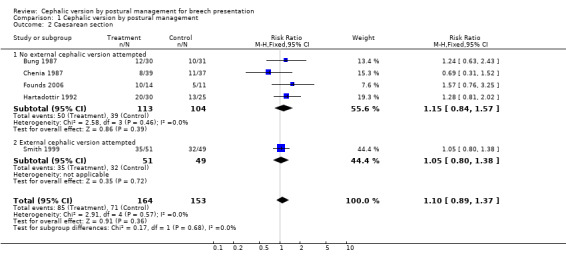

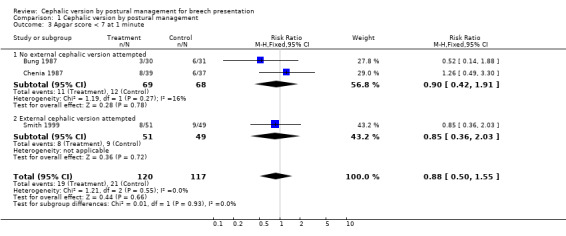

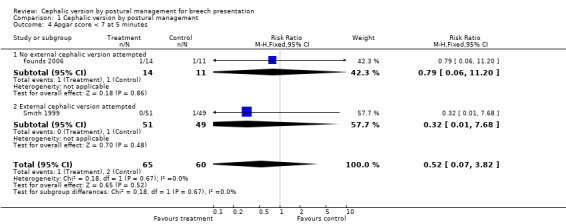

Effects of interventions

We included six studies involving a total of only 417 women. There was no effect on the rate of non‐cephalic births (risk ratio (RR) 0.98; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84 to 1.15; six trials, 417 women; Analysis 1.1), overall caesarean section rate (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.37; five trials, 317 women; Analysis 1.2) and rate of low Apgar score at one minute (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.55; three trials, 237 women; Analysis 1.3). The findings are consistent, at the 95% CI, with anything between a moderate positive and a negative effect. These findings held for the subgroup in which external cephalic version was not attempted, and the group overall, but may have been affected by a chance preponderance of primigravid women in the intervention groups (seeDescription of studies). The two trials which showed a tendency to reduced non‐cephalic births were those in which the procedure was started as early as 30 weeks' gestation (Bung 1987; Obwegeser 1999).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalic version by postural management, Outcome 1 Non‐cephalic births.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalic version by postural management, Outcome 2 Caesarean section.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalic version by postural management, Outcome 3 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute.

Discussion

The studies must be regarded as too small to establish conclusively whether or not postural management is effective.

The results of the trials are consistent with each other.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

To date, there is insufficient evidence from well‐controlled trials to support the routine use of postural management in clinical practice.

Implications for research.

The controlled trials reported to date are too small to support or refute the evidence from uncontrolled trials of the value of postural management for breech presentation.

Because of the simplicity of postural management and its potential wide application in different settings, it is reasonable that the procedure be evaluated further by means of larger randomised clinical trials. These should include evaluation of the effect of the gestational age on the effectiveness of these procedures, and exploration of women's views. Additional procedures which might be investigated to facilitate version include maternal hydration to increase amniotic fluid volume, and performing the procedure with a full bladder to aid disengagement of the presenting breech from the mother's pelvis.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 August 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review updated with new search date. |

| 22 August 2012 | New search has been performed | Search updated, No new trials identified |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1996 Review first published: Issue 2, 1996

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 September 2010 | New search has been performed | Search updated. One new trial included (Founds 2006), conclusions unchanged. |

| 1 October 2009 | New search has been performed | Search updated. One report added to Studies awaiting classification (Founds 2006). |

| 1 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 30 September 2001 | New search has been performed | Search updated. |

Acknowledgements

Tess Lawrie for assistance with classification of studies, data extraction, and updating of the review; Sonja Henderson for administrative support; Lynn Hampson and Jill Hampson for the literature search.

The original version of this review was made possible through a fellowship grant supported by the Department for International Development (UK) and Shell Petroleum. The sponsors do not take any responsibility for the data presented or the views expressed.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

The following methods were used to assess Bung 1987; Chenia 1987; Hartadottir 1992; Obwegeser 1999; Smith 1999. Trials under consideration were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion according to the prespecified selection criteria, without consideration of their results. Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the prespecified criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in Clarke 2000.

Data were extracted from the sources and entered onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2000), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Cephalic version by postural management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Non‐cephalic births | 6 | 417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.84, 1.15] |

| 1.1 No external cephalic version attempted | 5 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.75, 1.14] |

| 1.2 External cephalic version attempted | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.87, 1.38] |

| 2 Caesarean section | 5 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.89, 1.37] |

| 2.1 No external cephalic version attempted | 4 | 217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.84, 1.57] |

| 2.2 External cephalic version attempted | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.80, 1.38] |

| 3 Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute | 3 | 237 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.50, 1.55] |

| 3.1 No external cephalic version attempted | 2 | 137 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.42, 1.91] |

| 3.2 External cephalic version attempted | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.36, 2.03] |

| 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.07, 3.82] |

| 4.1 No external cephalic version attempted | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.06, 11.20] |

| 4.2 External cephalic version attempted | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.68] |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalic version by postural management, Outcome 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bung 1987.

| Methods | Allocated according to odd and even days of the month. | |

| Participants | Singleton breech presentation at 30 to 35 weeks. | |

| Interventions | 'Indian version' (10 to 15 minutes once or twice a day in the supine, head‐down position with the pelvis supported by a wedge‐shaped cushion) (n = 30), compared with control group (n = 31). | |

| Outcomes | Non‐cephalic births; caesarean sections; Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute. | |

| Notes | More primigravidas in study group (15/30 vs 11/31). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Allocated according to odd or even days of the month. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not feasible. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Other bias | High risk | More primigravidas in study group (15/30 vs 11/31). |

Chenia 1987.

| Methods | Randomised sealed envelopes used. | |

| Participants | Singleton breech presentation beyond 37 weeks. All participants were black women. | |

| Interventions | Knee‐chest position assumed with full urinary bladder 3 times a day for 7 days (n = 39), compared with control group (n = 37). | |

| Outcomes | Non‐cephalic births; caesarean sections; Apgar score < 7 at 1 minute. | |

| Notes | More primigravidas in the study group (11/39 vs 4/37). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomised. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not feasible. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | High risk | Moderate risk. More primigravidas in the study group (11/39 vs 4/37). |

Founds 2006.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, randomisation by coin tossing. | |

| Participants | 25 women with singleton breech presentations between 34 and 38 weeks. Excluded if there was a history of heart disease, hypertension, preterm labour, third trimester bleeding or uterine/placenta abnormalities. | |

| Interventions | Study group (14) were asked to do maternal knee‐chest posture for 15 minutes 3 times per day for 7 days, and were given a log to record time spent in the posture. | |

| Outcomes | Presentation at labour, mode of delivery, birthweight, Apgar scores. | |

| Notes | 2 protocol deviations and one woman was lost to follow‐up in study group. Intention‐to‐treat analysis applied. 9/14 in study group were primigravidas vs 4/11 in control group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation by coin tossing. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not feasible. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data. |

| Other bias | High risk | Moderate risk. More primigravidas (9/14) in study group than in control group (4/11). |

Hartadottir 1992.

| Methods | 'Randomized', method not specified. 3 withdrawals after randomisation (2 found to be cephalic on sonar, 1 lost to follow‐up). The women in the control group were not informed that they were participating in a trial. | |

| Participants | Singleton breech presentation beyond 34 weeks. | |

| Interventions | Women asked to assume knee‐chest position for 15 minutes twice a day (n = 30), compared with control group (n = 31). Compliance was poor in some women. | |

| Outcomes | Non‐cephalic births; caesarean section. | |

| Notes | More primigravidas in study group (19/30 versus 13/25). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'Randomized', method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not feasible. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | 3 subjects excluded after randomisation. |

| Other bias | High risk | Moderate risk. 3 subjects excluded after randomisation. More primigravidas in study group (19/30 versus 13/25). |

Obwegeser 1999.

| Methods | Separate computerised randomisation for primiparas and multiparas. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: ultrasound‐confirmed, uncomplicated singleton breech pregnancy, 30‐32 weeks' gestation. Exclusion criteria: uterine or pelvic abnormalities, maternal or fetal disease. | |

| Interventions | Asked to assume a supine position with the pelvis elevated by a 30‐35cm cushion, for periods of 10 minutes, twice daily (n = 50); compared with control group (n = 50). | |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous version. | |

| Notes | Universitatsfrauenklinik, Vienna. 3 women withdrawn from the study group because of poor compliance. Pilot study to calculate sample size. Study ended after the first year because of the large sample size needed to show a small difference. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Separate computerised randomisation for primiparas and multiparas. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not feasible. |

| Other bias | High risk | 9 post‐randomisation withdrawals: 6 women left the clinic (lost to follow‐up) and 3 women withdrawn because of poor compliance. |

Smith 1999.

| Methods | Randomised sealed envelopes using variable blocks and stratified by parity. No blinding of allocation. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: singleton breech presentation, gestational age 36 weeks or more. Exclusion criteria: placenta praevia, antepartum haemorrhage, fetal growth restriction, hypertensive disease, previous uterine surgery, uterine anomaly, ruptured membranes, fetal anomaly, contraindication to vaginal delivery, fetal death. | |

| Interventions | Asked to assume the knee‐chest position for 15 minutes, 3 times a day, for a week (n = 51). Compared with no postural management (n = 49). Both groups offered external cephalic version if still a breech presentation after a week. | |

| Outcomes | Breech presentation at birth; caesarean section; fetal and maternal complications. | |

| Notes | 1990 to 1997. Adelaide, Australia. Estimated sample size 288. Stopped after 100 due to slow enrolment. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomised sealed envelopes using variable blocks and stratified by parity. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not feasible. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | Baseline characteristics similar. |

vs: versus

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bullough 1987 | Excluded because the planned trial was not conducted. |

| Cardini 1998 | Excluded because posture was not used. May be included in a separate review. 130 primigravidas in the 33rd week of gestation were randomised to receive stimulation of acupoint BL 67 by moxa rolls for 7 to 14 days. The 130 in the control group received routine care. The intervention group experienced a mean of 48.45 fetal movements per day versus 35.35 in the control group (95% confidence interval (CI) for difference, 10.56 to 15.60). During the 35th week of gestation, 98 in the intervention group were cephalic versus 62 in the control group (risk ratio (RR) 1.58; 95% CI, 1.29 to 1.94). Despite the fact that 24 subjects in the control group and 1 subject in the intervention group underwent external cephalic version, 98 in the intervention group were cephalic at birth versus 81 in the control group (RR 1.21; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.43). |

| Van Drooge 1984 | Excluded because the technique of hyperextension is fundamentally different from the techniques used in the other studies. Allocation of women at 32 to 38 weeks was by envelope. Unfortunately, there were more nulliparous women in the study than the control group (11/20 versus 7/20). Version was less common, but not significantly so, in the study than in the control group (7/20 versus 9/20). |

Differences between protocol and review

The outcomes have been divided into 'Primary' and 'Secondary' outcomes, and the methods have been updated to reflect the latest Cochrane Handbook Higgins 2009.

Contributions of authors

GJ Hofmeyr prepared the original version and maintains the review. R Kulier revised and quality‐checked the original review and contributed to the writing of this update.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Witwatersrand, South Africa.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Geneva University Hospital, Switzerland.

External sources

South African Medical Research Council, South Africa.

Department for International Development, UK.

Shell Petroleum, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bung 1987 {published data only}

- Bung P, Huch R, Huch A. Is Indian version a successful method of lowering the frequency of breech presentations?. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde 1987;47:202‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chenia 1987 {published data only}

- Chenia F, Crowther CA. Does advice to assume the knee‐chest position reduce the incidence of breech presentation at delivery? A randomized clinical trial. Birth 1987;14:75‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Founds 2006 {published data only}

- Founds SA. Clinical implications from an exploratory study of postural management of breech presentation. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health 2006;51(4):292‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hartadottir 1992 {published data only}

- Hartadottir H, Thornton JG. A randomised trial of the knee/chest position to encourage spontaneous version of breech pregnancies. Proceedings of 26th British Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 1992; Manchester, UK, 1992:356. Manchester, 1992:356.

Obwegeser 1999 {published data only}

- Obwegeser R, Hohlagschwandtner M, Auerbach L, Schneider B. Management of breech presentation by Indian version ‐ a prospective, randomized trial [Erhohung der Rate von Spontanwendungen bei Beckenendlagen durch die Indische Brucke? Eine prospective, randomisierte Studie]. Zeitschrift fur Geburtshilfe und Neonatologie 1999;203:161‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 1999 {published data only}

- Smith C, Crowther C, Wilkinson C, Pridmore B, Robinson J. Knee‐chest postural management for breech at term: a randomized controlled trial. Birth 1999;26:71‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Wilkinson C, Crowther C. Knee chest postural management for breech at term: a randomised controlled trial. 2nd Annual Congress of the Perinatal Society of Australia & New Zealand; 1998 March 30‐April 4; Alice Springs, Australia 1998:143.

References to studies excluded from this review

Bullough 1987 {published data only}

- Bullough CHW. A comparison of methods of achieving version in late pregnancy. Personal communication 1987.

Cardini 1998 {published data only}

- Cardini F, Weixin H. Moxibustion for correction of breech presentation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280(18):1580‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Van Drooge 1984 {published data only}

- Drooge PH, Huisjes HJ. Hyperextension treatment in breech presentation [Hyperextensiebehandeling bij stuitligging]. Nederlands Tijdschrift roor Geneeskunde 1984;128:1088‐90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.1 [updated June 2000]. In: Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elkins 1982

- Elkins VH. External cephalic version. In: Enkin M, Chalmers I editor(s). Effectiveness and Satisfaction in Antenatal Care. London: Cambridge University Press, 1982:216. [Google Scholar]

Harbord 2006

- Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small‐study effects in meta‐analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Statistics in Medicine 2006;25:3443‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2009

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hofmeyr 1989

- Hofmeyr GJ. Breech presentation and abnormal lie in late pregnancy. In: Chalmers I, Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC editor(s). Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989:653‐65. [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 1996

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1996, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000083] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 2003

- Hofmeyr GJ, Hannah M. Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000166] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2000 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.1 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

RevMan 2008 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

References to other published versions of this review

Hofmeyr 1995

- Hofmeyr GJ. Cephalic version by postural management. [revised 05 October 1993]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.