Abstract

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis is a sexually transmitted infection. Mother‐to‐child transmission can occur at the time of birth and may result in ophthalmia neonatorum or pneumonitis in the newborn.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of antibiotics in the treatment of genital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis during pregnancy with respect to neonatal and maternal morbidity.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register and added the results to Studies awaiting classification (September 2006). We updated this search on 3 January 2012 and added one additional trial report to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of any antibiotic regimen compared with placebo or no treatment or alternative antibiotic regimens in pregnant women with genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed trial quality and extracted data independently. Study authors were contacted for additional information.

Main results

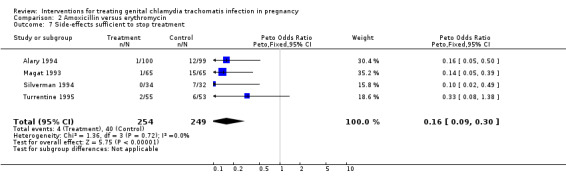

Eleven trials were included. Trial quality was generally good. Amoxycillin appeared to be as effective as erythromycin in achieving microbiological cure (odds ratio 0.54, 95% confidence interval 0.28 to 1.02). Amoxycillin was better tolerated than erythromycin (odds ratio 0.16, 95% confidence interval 0.09 to 0.30). Clindamycin and azithromycin also appear to be effective, although the numbers of women included in trials are small.

Authors' conclusions

Amoxycillin appears to be an acceptable alternative therapy for the treatment of genital chlamydial infections in pregnancy when compared with erythromycin. Clindamycin and azithromycin may be considered if erythromycin and amoxycillin are contra‐indicated or not tolerated.

[Note: The seven citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Chlamydia trachomatis; Anti‐Bacterial Agents; Anti‐Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use; Chlamydia Infections; Chlamydia Infections/drug therapy; Chlamydia Infections/transmission; Genital Diseases, Female; Genital Diseases, Female/drug therapy; Infectious Disease Transmission, Vertical; Infectious Disease Transmission, Vertical/prevention & control; Pregnancy Complications, Infectious; Pregnancy Complications, Infectious/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Interventions for treating genital chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy

Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted infection which, if a mother has it during pregnancy and labour, can cause eye or lung infections in the newborn baby. The risk of transmission during birth varies, but is about 20% to 50% for eye infections and about 10% to 20% for infection of the lungs. Mothers may also be at increased risk of infection of the uterus. The review looked at various antibiotics being used during pregnancy to reduce these problems and to assess any adverse effects. Tetracyclines taken in pregnancy are known to be associated with teeth and bone abnormalities in babies, and some women find erythromycin unpleasant to take because of feeling sick and vomiting. The review found eleven trials, involving 1449 women, on erythromycin, amoxycillin, azithromycin and clindamycin, and the overall trial quality was good. However, all the trials assessed 'microbiological cure' (that is they looked for an eradication of the infection) and none assessed whether the eye or lung problems for the baby were reduced. Also, none of the trials were large enough to assess potential adverse outcomes adequately. The review found amoxycillin was an effective alternative to erythromycin but lack of long‐term assessment of outcomes caused concern about its routine use in practice. If erythromycin is used, some women may stop taking it because of adverse effects. Azithromycin and clindamycin are potential alternatives. More research is needed.

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis is a sexually transmitted infection. Mother‐to‐child transmission can occur at the time of delivery and may result in ophthalmia neonatorum or pneumonitis in the neonate. Estimates of the risk of transmission at the time of delivery vary. The risk of mother‐to‐child transmission resulting in moderate to severe conjunctivitis appears to be approximately 15% to 25% and for pneumonitis 5% to 15%. Postpartum endometritis has also been associated with chlamydial infection, although the risk of this occurring in women infected with chlamydia at the time of delivery is not known.

The drugs of choice for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection are the tetracyclines; however, as the use of tetracyclines in pregnancy are known to be associated with teeth and bone abnormalities, erythromycin has been recommended as the first‐line treatment. Some women find erythromycin unpleasant to take because of nausea and vomiting and this may result in poor compliance which may lead to persisting infection.

As a consequence other antibiotic regimens have been investigated as alternatives to erythromycin.

Objectives

To determine whether antibiotic therapy in women infected with genital Chlamydia trachomatis is effective in the prevention of neonatal chlamydial infection and postpartum endometritis. In the absence of this information, eradication of maternal infection as determined by microbiological cure has been taken as a surrogate outcome. The occurrence of side‐effects of treatment is also included.

If antibiotics are effective, the review will seek to determine which antibiotics are effective and review their side‐effect profile.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials comparing antibiotic therapy with placebo or no therapy and all randomised controlled trials comparing two different antibiotic regimens in pregnant women with genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection (any method of diagnosis).

Types of participants

Women identified at any stage during the antenatal period as having genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection (symptomatic or asymptomatic). Co‐infection with other sexually transmitted infections will not be a reason to exclude women from the review.

Types of interventions

Any antibiotic (any dosage and any route of administration) versus placebo or no therapy.

Comparisons of any two different antibiotic regimens.

Types of outcome measures

(i) Neonatal death (ii) Ophthalmia neonatorum (iii) Neonatal pneumonitis (iv) Maternal postpartum endometritis (v) Delivery less than 37 weeks' gestation (vi) Failure to achieve microbiological cure (vii) Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment/change treatment (viii) Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment (ix) Fetal anomalies

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (September 2006 and 3 January 2012) and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

All potential trials were selected for eligibility according to the criteria specified in the protocol. The information necessary for the review was abstracted from the report by each of the review authors independently and, where necessary, we requested additional information from the authors.

All trials were assessed for methodological quality using standard Cochrane criteria. Summary odds ratios have been calculated if appropriate (ie if there is no evidence of significant heterogeneity) using the Cochrane statistical software, RevMan.

Results

Description of studies

For details of included studies, see table of Characteristics of included studies. For details of excluded studies, see the table of Characteristics of excluded studies. (Seven reports from updated searches been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the methodological quality for each included trial using a simple checklist, which included whether the allocated treatment was adequately concealed and the proportion of women lost to follow up.

Overall, the quality of the trials was good. Four of the eleven included trials were double blind and all trials reported losses to follow up. The description of the interventions was good (with the exception of Martin 1997) and the main outcome of all the trials was well described in most.

The process by which the interventions were randomly assigned was not well specified in two of the trials, although both papers stated that the allocation was random and both of these trials were double blind (Alger 1991; Bell 1982).

Effects of interventions

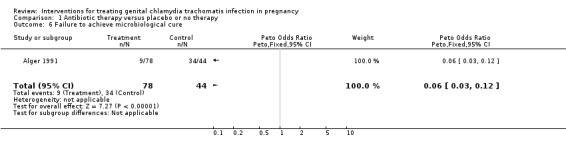

Antibiotic therapy for genital chlamydial infection in pregnancy reduces the number of women with positive cultures following treatment by approximately 90% when compared with placebo.

All the tested antibiotic regimens demonstrate a high level of 'microbiological cure' (with the exception of Martin 1997, which did not report this outcome). The data suggest that amoxycillin may even be superior to erythromycin in achieving microbiological cure, although this difference is not statistically significant.

When compared with erythromycin the use of amoxycillin was associated with a lower incidence of side‐effects in general, and in particular with a lower incidence of side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment. With the relatively small amount of data presented, azithromycin appears to be very well tolerated. Side‐effects of clindamycin appear to be no different, in frequency, from those of erythromycin.

There is little evidence from any of the included trials that 'microbiological cure' is the same as prevention of neonatal infection or postnatal infection in the mother. One trial (Alary 1994), assessed neonatal infection by taking chlamydial cultures from the neonate at one week of age. No positive cultures were found from 152 neonates tested.

Discussion

The suggestion that amoxycillin is a useful treatment for genital chlamydial infection is surprising. In vitro studies suggest that Chlamydia trachomatis is relatively insensitive to amoxycillin (Kuo 1977). This review, however, suggests very strongly that amoxycillin does eradicate chlamydial infection in pregnancy.

The number of women included in these trials is too small to assess whether the newer antibiotics included in this review such as azithromycin and clindamycin are safe for use in pregnancy, as rare adverse outcomes are unlikely to be detected and clinical experience with their use is limited.

'Microbiological cure' is used in these trials as an alternative to eradication of infection. This assumption may not hold true, however, and the extent to which it is true may vary between the different antibiotics being tested. Thus, if two antibiotics appear to be equally effective in terms of 'microbiological cure' there may still be differences in their effect on more substantive outcomes such as neonatal chlamydial infection. Unfortunately, no trial reported this information in terms of clinical disease.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review suggests that, in terms of microbiological 'cure', amoxycillin is an effective alternative to erythromycin for women with genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy. The lack of suitable data on the longer‐term effectiveness of amoxycillin in terms of the risk of neonatal infection does, however, cause concern about its routine use in clinical practice.

The decision to implement using amoxycillin as the first line treatment for genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy will depend on the extent to which clinicians are satisfied that a negative 'test of cure' in the woman is equivalent to prevention of neonatal infection.

If erythromycin continues to be used as the treatment of choice in pregnancy then there seems little doubt that if women are intolerant of erythromycin then amoxycillin seems a suitable alternative. Clindamycin and azithromycin may be considered further alternatives if erythromycin and amoxycillin are contra‐indicated or not tolerated.

Implications for research.

Further studies are necessary to determine whether amoxicillin is associated with true eradication of Chlamydia trachomatis from the genital tract during pregnancy. Long‐term follow up of a cohort of mothers and neonates treated with amoxycillin for genital chlamydial infection in pregnancy to precisely determine the risk of neonatal infection may be enough to reassure clinicians that the treatment is suitable for more widespread use. However, a large randomised comparison of amoxycillin and erythromycin which addressed their relative effectiveness in preventing neonatal infection would be ideal.

The results obtained with clindamycin and azithromycin could usefully be repeated in larger trials which rely more on substantive outcome measures. If amoxycillin is adopted widely as first‐line treatment for chlamydia in pregnancy then amoxycillin would be the appropriate control treatment for such trials.

[Note: The seven citations in Studies awaiting classification may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 January 2013 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1996 Review first published: Issue 2, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 January 2012 | Amended | Search updated. One additional trial report added to the Studies awaiting classification section (El‐Shourbagy 2011). Information about the updating of this review has been added to Published notes. |

| 12 June 2009 | Amended | Search updated. No new reports identified. Jacobson 2001; Kacmar 2001; Nadafi 2005; Wehbeh 1996; Wehbeh 1998; and Zul'karneev 1998 remain in the Studies awaiting classification section. |

| 11 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 1 February 2007 | Amended | Plain language summary added. We updated the search in September 2006. The six new reports of trials identified through the updated search (Jacobson 2001; Kacmar 2001; Nadafi 2005; Wehbeh 1996; Wehbeh 1998; Zul'karneev 1998) have been added to the Studies awaiting classification and will be assessed for the 2007 update later this year. |

| 23 June 1998 | New search has been performed | Search updated. Four new trials added. |

Notes

This review has been relinquished by the original review team. If you are interested in updating this review, please register your interest by completing a Title Registration Form, which you will find on our website at http://pregnancy.cochrane.org/, and emailing the completed form to the Managing Editor.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Alary, Dr Alger and Dr Silverman who provided us with extra information from their trials.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antibiotic therapy versus placebo or no therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

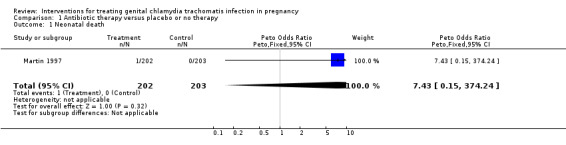

| 1 Neonatal death | 1 | 405 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.43 [0.15, 374.24] |

| 2 Ophthalmia neonatorum | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Neonatal pneumonitis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

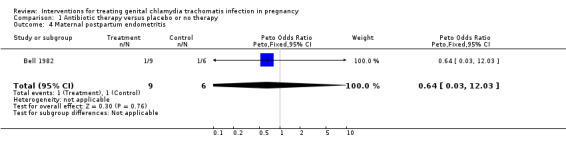

| 4 Maternal postpartum endometritis | 1 | 15 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.03, 12.03] |

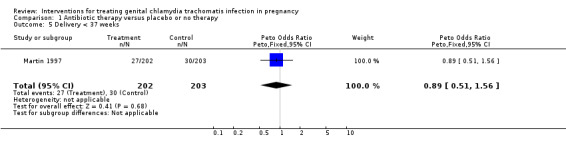

| 5 Delivery < 37 weeks | 1 | 405 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.51, 1.56] |

| 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure | 1 | 122 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.03, 0.12] |

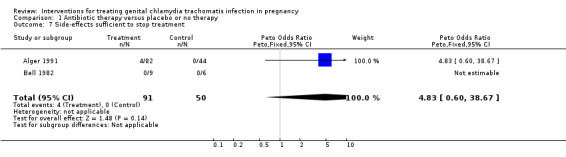

| 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment | 2 | 141 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.83 [0.60, 38.67] |

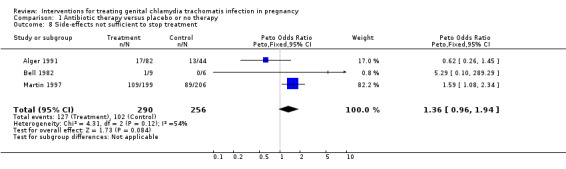

| 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment | 3 | 546 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.96, 1.94] |

| 9 Fetal anomalies | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic therapy versus placebo or no therapy, Outcome 1 Neonatal death.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic therapy versus placebo or no therapy, Outcome 4 Maternal postpartum endometritis.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic therapy versus placebo or no therapy, Outcome 5 Delivery < 37 weeks.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic therapy versus placebo or no therapy, Outcome 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic therapy versus placebo or no therapy, Outcome 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic therapy versus placebo or no therapy, Outcome 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment.

Comparison 2. Amoxicillin versus erythromycin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Ophthalmia neonatorum | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Neonatal pneumonitis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Maternal postpartum endometritis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Delivery < 37 weeks | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

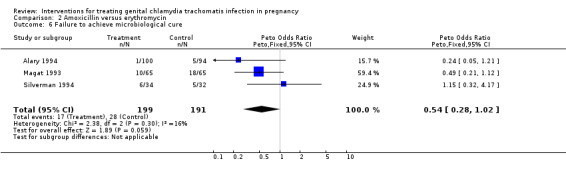

| 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure | 3 | 390 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.28, 1.02] |

| 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment | 4 | 503 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.09, 0.30] |

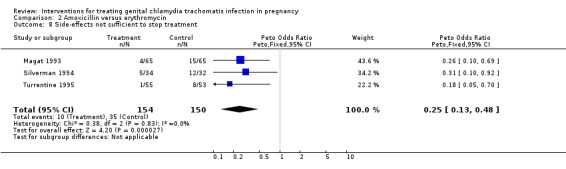

| 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment | 3 | 304 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.13, 0.48] |

| 9 Fetal anomalies | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Amoxicillin versus erythromycin, Outcome 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Amoxicillin versus erythromycin, Outcome 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Amoxicillin versus erythromycin, Outcome 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment.

Comparison 3. Azithromycin versus erythromycin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

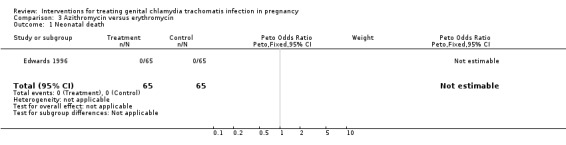

| 1 Neonatal death | 1 | 130 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Ophthalmia neonatorum | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Neonatal pneumonitis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Maternal postpartum endometritis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

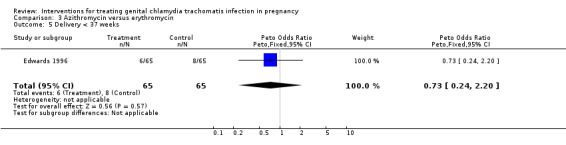

| 5 Delivery < 37 weeks | 1 | 130 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.24, 2.20] |

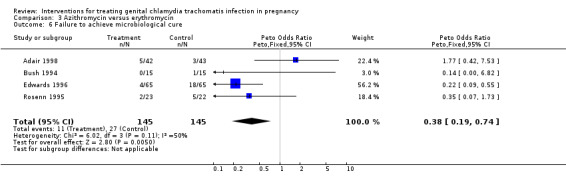

| 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure | 4 | 290 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.19, 0.74] |

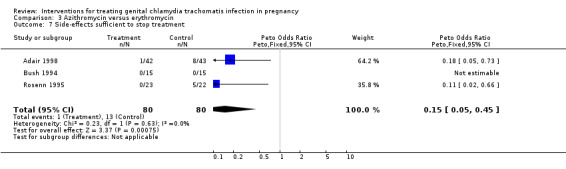

| 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment | 3 | 160 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.05, 0.45] |

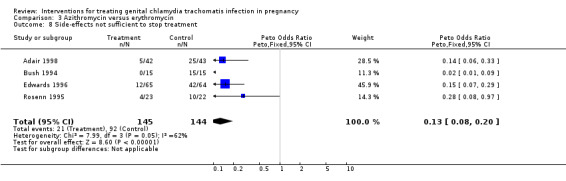

| 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment | 4 | 289 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.08, 0.20] |

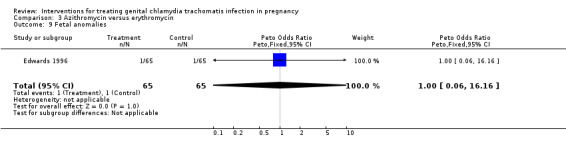

| 9 Fetal anomalies | 1 | 130 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 16.16] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 1 Neonatal death.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 5 Delivery < 37 weeks.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 9 Fetal anomalies.

Comparison 4. Clindamycin versus erythromycin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Ophthalmia neonatorum | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Neonatal pneumonitis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Maternal postpartum endometritis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Delivery < 37 weeks | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

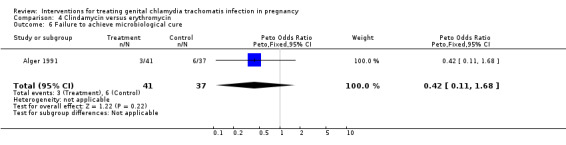

| 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure | 1 | 78 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.11, 1.68] |

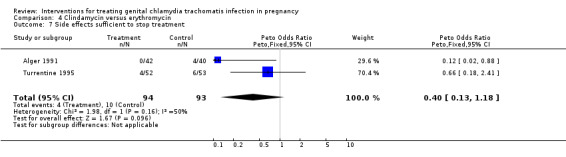

| 7 Side effects sufficient to stop treatment | 2 | 187 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.13, 1.18] |

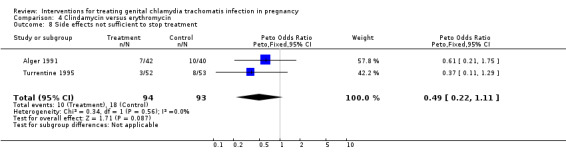

| 8 Side effects not sufficient to stop treatment | 2 | 187 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.22, 1.11] |

| 9 Fetal anomalies | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Clindamycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Clindamycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 7 Side effects sufficient to stop treatment.

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Clindamycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 8 Side effects not sufficient to stop treatment.

Comparison 5. Clindamycin versus amoxicillin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Ophthalmia neonatorum | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Neonatal pneumonitis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Maternal postpartum endometritis | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Delivery < 37 weeks | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Failure to achieve microbiological cure | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

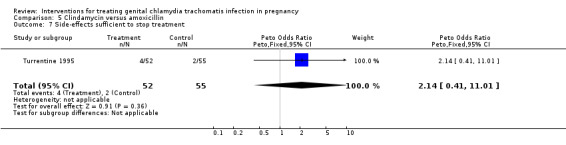

| 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment | 1 | 107 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [0.41, 11.01] |

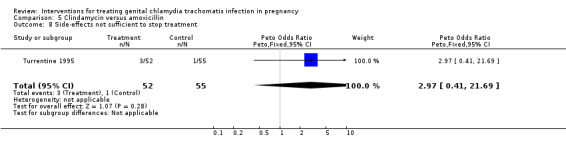

| 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment | 1 | 107 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.97 [0.41, 21.69] |

| 9 Fetal anomalies | 0 | 0 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Clindamycin versus amoxicillin, Outcome 7 Side‐effects sufficient to stop treatment.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Clindamycin versus amoxicillin, Outcome 8 Side‐effects not sufficient to stop treatment.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Adair 1998.

| Methods | Random numbers generated in blocks of 20. Allocation cards in sealed opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 106 pregnant women with positive cervical swabs of Chlamydia trachomatis using a direct DNA probe. Exclusions ‐ hypersensitivity to study drugs. | |

| Interventions | Azithromycin 1 g stat Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days All partners referred for treatment. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure using DNA probe 3 weeks after start of treatment Side effects. | |

| Notes | Not blinded 9/54 of azithromycin and 7/52 of erythromycin lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Alary 1994.

| Methods | Random allocation. | |

| Participants | 210 pregnant women with positive cervical or urethral cultures of Chlamydia trachomatis. Exclusions ‐ >38 weeks at diagnosis, treatment with antibiotics between the cervical culture being taken and randomisation, known allergy to the study drugs. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days Amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day for 7 days All partners treated with doxycycline. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure by culture 21 days after the completion of study drug Swabs taken from babies' eyes, nose, pharynx, rectum and genitals for culture of Chlamydia trachomatis at age 1 week. | |

| Notes | Double blind. Amoxicillin recipients received a dummy dose to make both drug regimens four times a day. 5/105 in amoxicillin group and 6/105 in erythromycin group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Alger 1991.

| Methods | 'Random allocation' ‐ method not specified. | |

| Participants | 135 pregnant women with positive cervical cultures of Chlamydia trachomatis. Exclusions ‐ >24 weeks at diagnosis, recent antibiotic use, known allergy to study drugs, impaired hepatic function, colitis, current use of insulin, warfarin, steroids and carbamazepine. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 333 mg plus clindamycin placebo four times a day for 14 days Clindamycin 450 mg plus erythromycin placebo four times a day for 14 days Clindamycin placebo and erythromycin placebo four times a day for 14 days All partners treated with doxycycline. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure by culture 14 days after first dose of study drug Second test of cure 4 weeks later Final test of cure in labour. | |

| Notes | Double blind 9/135 women lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Bell 1982.

| Methods | 'Random allocation' ‐ method not specified. | |

| Participants | 27 pregnant women with positive cervical cultures of Chlamydia trachomatis. Exclusions ‐ >24 weeks at diagnosis, known allergy to study drugs. | |

| Interventions | Amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day for 10 days Matching placebo All partners treated with tetracycline or doxycycline. | |

| Outcomes | Infant infection determined by multiple culture and serology of blood and tears Maternal post partum endometritis. | |

| Notes | Double blind 2/13 in amoxicillin group and 4/14 in placebo group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bush 1994.

| Methods | Random allocation by sealed opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 30 pregnant women with positive cervical swabs of Chlamydia trachomatis using DNA assay. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days Azithromycin 1 g single dose All partners treated with doxycycline. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure using DNA assay 14 days after completion of study drug. | |

| Notes | Not double blind No loss to follow‐up. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Edwards 1996.

| Methods | Random number table. | |

| Participants | 140 pregnant women with positive cervical swab for Chlamydia trachomatis using DNA hybridisation. Exclusions ‐ <15 years, known allergy to study drugs. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days Azithromycin 1 g stat All partners referred for treatment. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure 2 weeks after starting study drugs using DNA hybridisation. | |

| Notes | Not blinded 7/72 in erythromycin group and 3/68 in azithromycin group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Magat 1993.

| Methods | Random allocation. | |

| Participants | 143 pregnant women with positive cervical cultures of Chlamydia trachomatis. Exclusions ‐ >36 weeks at diagnosis, current antibiotic use, known allergy to study drugs, gastrointestinal upset, colitis. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days Amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day for 7 days All partners treated with doxycycline. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure by culture 4 weeks after first dose of study drug. | |

| Notes | Not double blind 6/71 erythromycin group and 7/72 in amoxycillin group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Martin 1997.

| Methods | Random number generator with random block sizes of 2, 4 and 6 Stratified by centre. | |

| Participants | 423 pregnant women at 23‐29 weeks gestation with positive cervical Chlamydia trachomatis cultures. Exclusions ‐ <16 years, medical complications related to preterm delivery, antibiotics after initial culture and prior to trial entry, allergy to erythromycin, receiving theophylline, co‐infection with gonorrhoea. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin base 333 mg three times a day until completion of 35th week gestation (minimum of 6 weeks) Matching placebo All partners referred for treatment All women treated with doxycycline, tetracycline or erythromycin after delivery ‐ infants either treated empirically or followed‐up. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure with culture 2‐4 weeks after enrolment (results not reported) Low birth weight Premature rupture of membranes Preterm delivery. | |

| Notes | Double blind 1 week run‐in period to assess compliance ‐ 180/594 (30%) excluded following run‐in 3/208 in erythromycin group and 6/215 in placebo group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Rosenn 1995.

| Methods | Random numbers in block size 6. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 48 pregnant women positive for Chlamydia trachomatis screened at their first prenatal visit by DNA PCR. Exclusions ‐ 36 weeks or greater, antibiotics in 14 days prior to enrolment, co‐infection with gonorrhoea, sensitivity to study drugs. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days Azithromycin 1 g stat All partners treated. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure by DNA PCR 3 weeks after study drug finished. | |

| Notes | Not double blind 1/24 in azithromycin group and 2/24 in erythromycin group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Silverman 1994.

| Methods | Sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 74 pregnant women with positive cervical cultures of Chlamydia trachomatis. Exclusions ‐ >36 weeks at diagnosis, recent antibiotic use (within 14 days), known allergy to study drugs. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days Amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day for 7 days All partners treated with doxycycline. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure by culture 3‐4 weeks after starting study drugs. | |

| Notes | Not double blind 4/36 in erythromycin group and 4/38 in amoxicillin group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Turrentine 1995.

| Methods | Random allocation. | |

| Participants | 113 pregnant women with positive cervical cultures of Chlamydia trachomatis. Exclusions ‐ >36 weeks at diagnosis, current antibiotic use, known allergy to study drugs, gastrointestinal upset. | |

| Interventions | Erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 7 days Amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day for 7 days Clindamycin 600 mg three times a day for 10 days All partners treated with doxycyline. | |

| Outcomes | Test of cure by culture 4 weeks after study drug finished. | |

| Notes | Not double blind 3/56 in erythromycin group, 2/57 in amoxicillin group and 3/55 in clindamycin group lost to follow‐up (no outcome data). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid PCR = polymerase chain reaction stat = given once

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Crombleholme 1990 | Pregnant women with cervical Chlamydia trachomatis infection were 'offered' amoxycillin treatment. If they declined they were given erythromycin. No element of random allocation was included in this study. |

| McGregor 1990 | Women were selected for trial entry on the basis of a high population risk of preterm delivery and treated with erythromycin or placebo. Of the 229 women enrolled, 26 had a positive culture for endocervical Chlamydia trachomatis. No outcome data is presented by infection status at recruitment. |

| Thomason 1990 | Historical cohort study comparing standard duration of erythromycin therapy with a short course. Not random allocation. |

Contributions of authors

Both authors prepared the review. Peter Brocklehurst maintains the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Department of Health, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Adair 1998 {published data only}

- Adair CD, Gunter M, Stovall TG, Mcelroy G, Veille JC, Ernest JM. Chlamydia in pregnancy: a randomized trial of azithromycin and erythromycin. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1998;91:165‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alary 1994 {published data only}

- Alary M, Joly JR, Moutquin JM, Mondor M, Boucher M, Fortier A, et al. Randomised comparison of amoxycillin and erythromycin in treatment of genital chlamydial infection in pregnancy. Lancet 1994;344:1461‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alger 1991 {published and unpublished data}

- Alger LS, Lovchik JC. Comparative efficacy of clindamycin versus erythromycin in eradication of antenatal Chlamydia trachomatis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1991;165:375‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bell 1982 {published data only}

- Bell TA, Sandstrom IK, Eschenbach DA, Hummel D, Kuo C, Wang S, et al. Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy with amoxicillin. In: Mardh PA editor(s). Chlamydial infections. Elsevier Biomedical Press, 1982:221‐4. [Google Scholar]

Bush 1994 {published data only}

- Bush MR, Rosa C. Azithromycin and erythromycin in the treatment of cervical chlamydial infection during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1994;84:61‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Edwards 1996 {published data only}

- Edwards MS, Newman RB, Carter SG, LeBoeuf FW, Menard MK, Rainwater KP. Randomized clinical trial of azithromycin for the treatment of Chlamydia cervicitis in pregnancy. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics & Gynecology 1996;4:333‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magat 1993 {published data only}

- Magat AH, Alger LS, Nagey DA, Hatch V, Lovchik JC. Double‐blind randomized study comparing amoxicillin and erythromycin for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1993;81:745‐749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martin 1997 {published data only}

- Martin DH, Eschenbach DA, Cotch MF, Nugent RP, Roa AV, Klebanoff MA, et al. Double‐blind placebo‐controlled treatment trial of Chlamydia trachomatis endocervical infections in pregnant women. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics & Gynecology 1997;5:10‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rosenn 1995 {published data only}

- Rosenn M, Macones GA, Silverman N. A randomized trial of erythromycin and azithromycin for the treatment of chlamydia infection in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;174:410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenn MF, Macones GA, Silverman NS. Randomized trial of erythromcyin and azithromycin for treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnancy. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics & Gynecology 1995;3:241‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Silverman 1994 {published data only}

- Silverman N, Hochman M, Sullivan M, Womack M. A randomized prospective trial of amoxicillin versus erythromycin for the treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;168:420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman NS, Sullivan M, Hochman M, Womack M, Jungkind DL. A randomized, prospective trial comparing amoxicillin and erythromycin for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994;170:829‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Turrentine 1995 {published data only}

- Turrentine MA, Troyer L, Gonik B. Randomized prospective study comparing erythromycin, amoxicillin and clindamycin for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics & Gynecology 1995;2:205‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Crombleholme 1990 {published data only}

- Crombleholme WR, Schachter J, Grossman M, Landers DV, Sweet RL. Amoxicillin therapy for Chlamyida trachomatis in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1990;75:752‐756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGregor 1990 {published data only}

- McGregor JA, French JI, Richter R, Vuchetich M, Bachus V, Seo K, et al. Cervicovaginal microflora and pregnancy outcome: results of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of erythromycin treatment. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1990;163:1580‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomason 1990 {published data only}

- Thomason JL, Kellett AV, Gelbart SM, James JA, Broekhuizen FF. Short‐course erythromycin therapy for endocervical chlamydia during pregnancy. Journal of Family Practice 1990;30:711‐2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

El‐Shourbagy 2011 {published data only}

- El‐Shourbagy MAA, El‐Refaie TA, Sayed KKA, Wahba KAH, El‐Din ASS, Fathy MM. Impact of seroconversion and antichlamydial treatment on the rate of pre‐eclampsia among Egyptian primigravidae. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2011;113(2):137‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jacobson 2001 {published data only}

- Jacobson GF, Autry AM, Kirby RS, Liverman EM, Motley RU. A randomized controlled trial comparing amoxicillin and azithromycin for the treatment of chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;184(7):1352‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kacmar 2001 {published data only}

- Kacmar J, Cheh E, Montagno A, Peipert JF. A randomized trial of azithromycin versus amoxicillin for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2001;9:197‐202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nadafi 2005 {published data only}

- Nadafi M, Abdali KH, Parsanejad ME, Rajaee‐Fard AR, Kaviani M. A comparison of amoxicillin and erythromycin for asymptomatic chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2005;90(2):142‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wehbeh 1996 {published data only}

- Wehbeh H, Ruggiero R, Ali Y, Lopez G, Shahem S, Zarou D. A randomized clinical trial of a single dose of zithromycin in treatment of chlamydia amongst pregnant women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;174(1 Pt 2):361. [Google Scholar]

Wehbeh 1998 {published data only}

- Wehbeh HA, Ruggeirio RM, Shahem S, Lopez G, Ali Y. Single‐dose azithromycin for chlamydia in pregnant women. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1998;43(6):509‐14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zul'karneev 1998 {published data only}

- Zul'karneev RSh, Kalinin IuT, Afanas'ev SS, Rubal'skii OV, Denisov LA, Vorob'ev AA, Sorokin SV. Use of recombinant alpha2‐interferon and a complex immunoglobulin preparation for the treatment of chlamydiosis in pregnancy women. Zhurnal Mikrobiologii, Epidemiologii i Immunobiologii 1998, (2):115‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Kuo 1977

- Kuo CC, Wang SP, Grayston TJ. Antimicrobial activity of several antibiotics and a sulfonamide against Chlamydia trachomatis organisms in cell culture. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1977;12:80‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]