Abstract

Background

Because of the high number of people with schizophrenia not responding adequately to monotherapy with antipsychotic agents, the evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of additional medication was examined in a number of clinical trials. One approach to this research question was the use of benzodiazepines, as monotherapy as well as in combination with antipsychotics.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of benzodiazepines in people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychoses.

Search methods

In February 2011, we updated the literature search of the previous version of this systematic review (last search March 2005). We searched the trial register of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group (containing methodical searches of BIOSIS, CINAHL, Dissertation abstracts, EMBASE, LILACS, MEDLINE, PSYNDEX, PsycINFO, RUSSMED, Sociofile, supplemented with hand searching of relevant journals and numerous conference proceedings). Additionally, we inspected references of all identified studies for further relevant studies and contacted authors of relevant publications in order to obtain missing data from existing trials. We applied no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials comparing benzodiazepines (as monotherapy or as adjunctive agent) with antipsychotic drugs or placebo for the pharmacological management of schizophrenia and/or schizophrenia‐like psychoses.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors (MD and CL) analysed independently the new references of the update‐search referring to the inclusion criteria. MD and CL extracted all data from the included trials. For dichotomous outcomes we calculated risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). We analysed continuous data by using mean differences (MD) and their 95% CI. We assessed each pre‐selected outcome from the included trials with the risk of bias tool.

Main results

The 2011 update search yielded three further randomised controlled trials. The review currently includes 34 studies with 2657 participants. Most studies were characterised by a small sample size, short duration, and incomplete outcome data reporting.

Benzodiazepine monotherapy is compared with placebo in eight trials. The proportion of participants with no clinically important response did not significantly differ between those given benzodiazepines or placebo (N = 382, 6 RCTs, RR 0.67 CI 0.44 to 1.02). The results from the various rating scales applied to assess global and mental state were inconsistent.

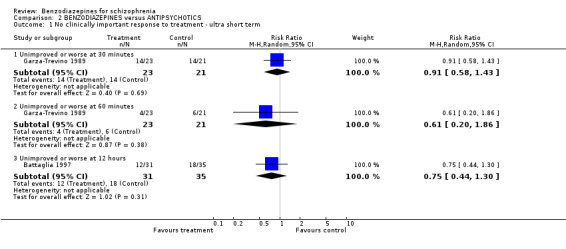

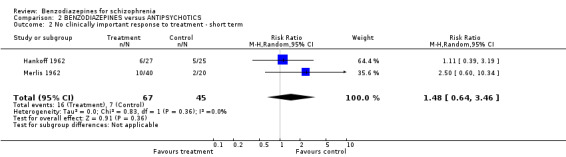

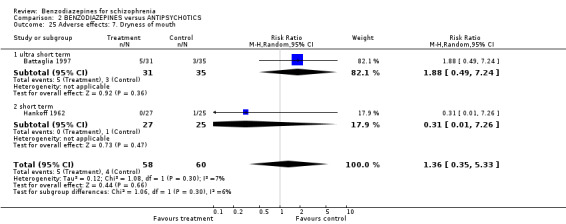

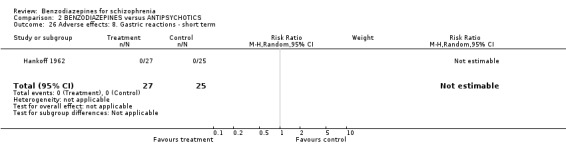

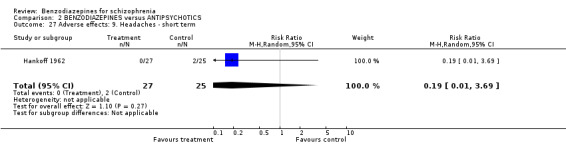

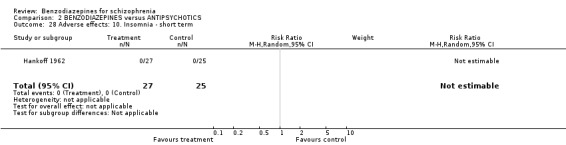

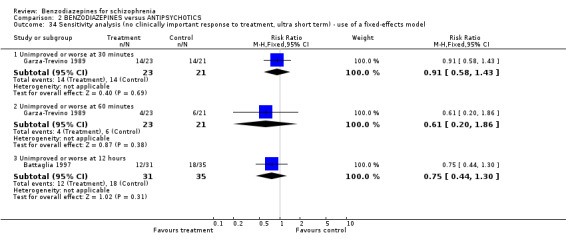

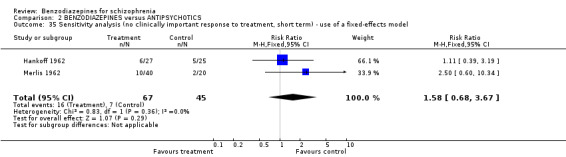

Fourteen studies examined benzodiazepine monotherapy in comparison with antipsychotic monotherapy. Clinically important treatment response assessment revealed no statistically significant difference between the study groups (30 minutes: N = 44, 1 RCT, RR 0.91 CI 0.58 to 1.43; 60 minutes: N = 44,1 RCT, RR 0.61 CI 0.20 to 1.86; 12 hours: N = 66, 1 RCT, RR 0.75 CI 0.44 to 1.30; pooled short‐term studies: N = 112, 2 RCTs, RR 1.48 CI 0.64 to 3.46). Desired sedation occurred significantly more often among participants in the benzodiazepine group than in the antipsychotic group at 20 and 40 minutes. No significant between‐group differences could be identified for global and mental state or occurrence of adverse effects.

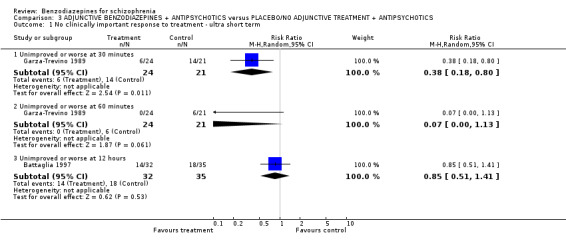

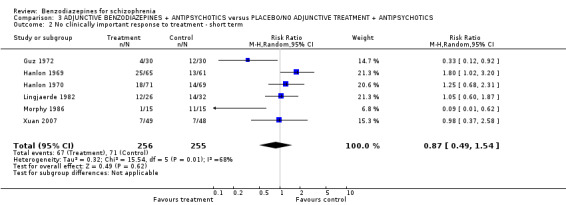

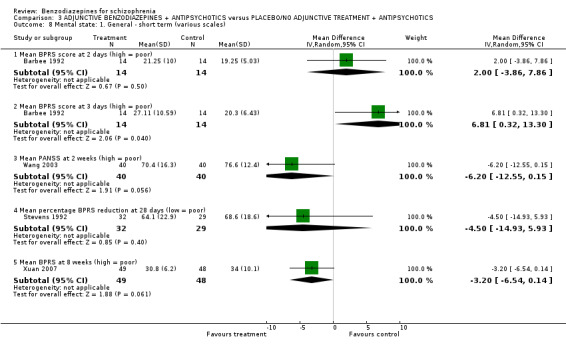

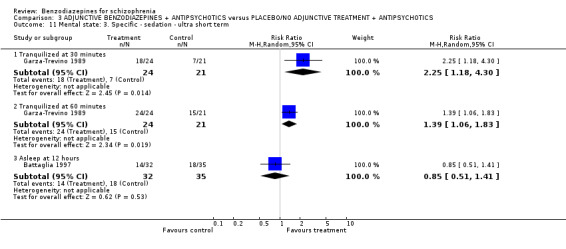

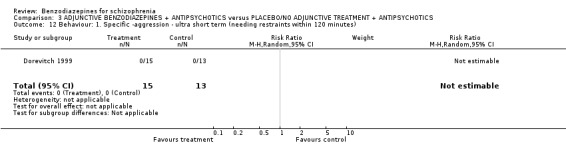

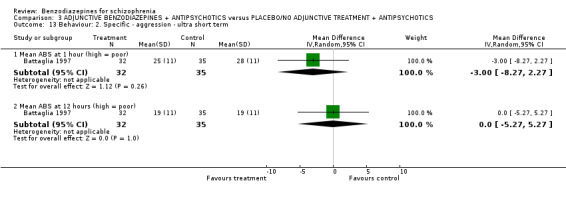

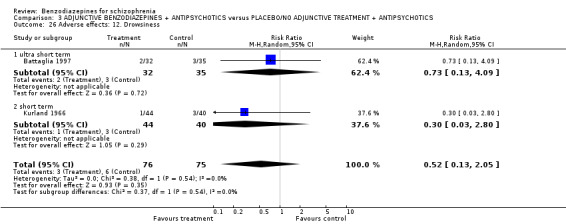

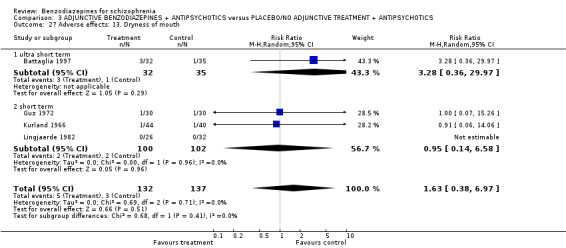

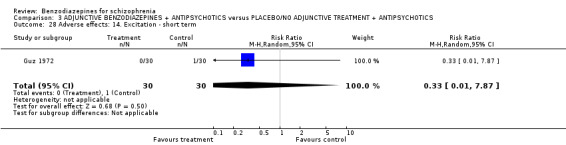

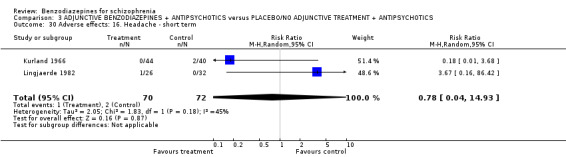

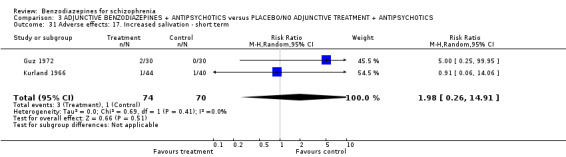

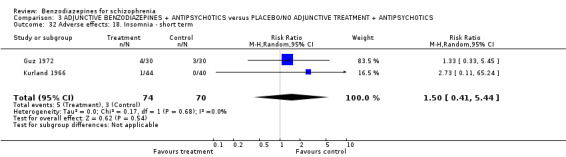

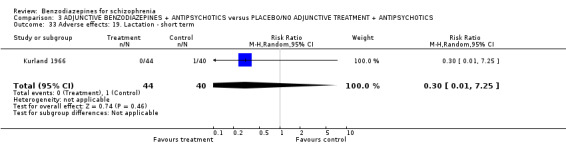

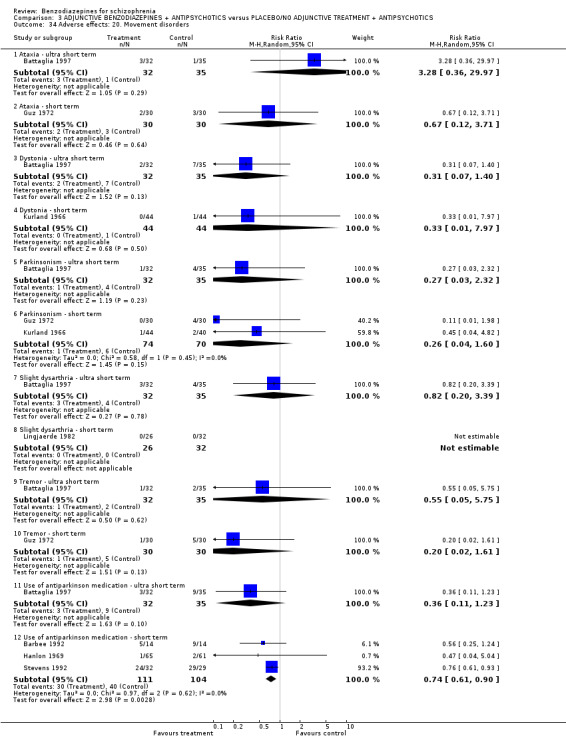

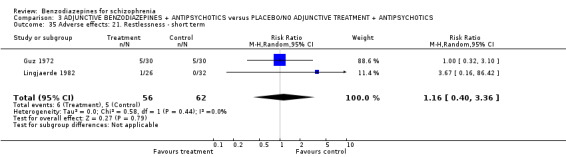

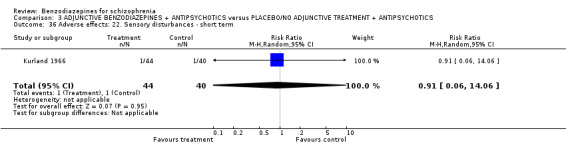

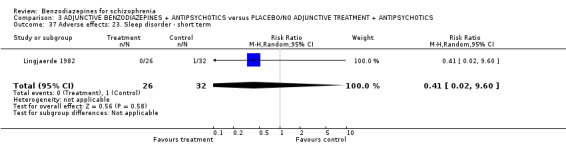

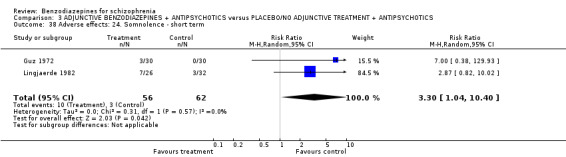

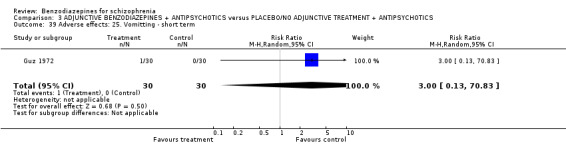

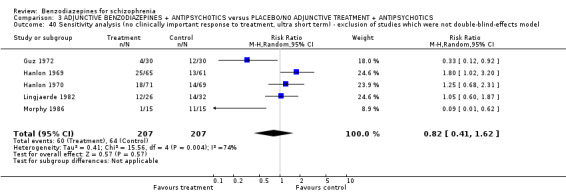

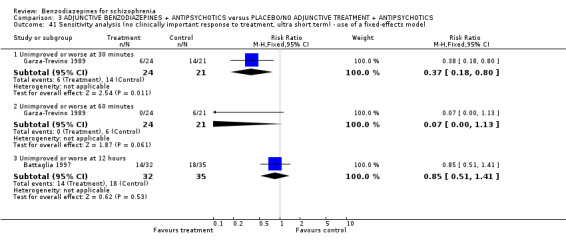

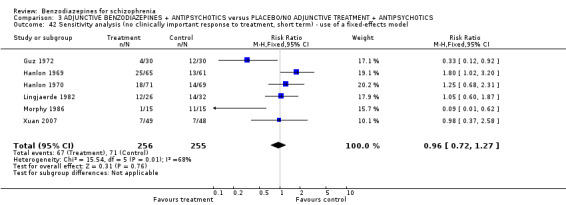

Twenty trials compared benzodiazepine augmentation of antipsychotics with antipsychotic monotherapy. Referring to clinically important response, statistically significant improvement could be demonstrated only for the first 30 minutes of augmentation treatment (30 minutes: 1 RCT, N = 45, RR 0.38 CI 0.18 to 0.80; 60 minutes: N = 45,1 RCT, RR 0.07 CI 0.00 to 1.13; 12 hour: N = 67,1 RCT, RR 0.85 CI 0.51 to 1.41; pooled short‐term studies: N = 511, 6 RCTs, RR 0.87 CI 0.49 to 1.54). Analyses of the global and mental state yielded no between‐group differences except for desired sedation at 30 as well as 60 minutes (30 minutes: N = 45, 1 RCT, RR 2.25 CI 1.18 to 4.30; 60 minutes: N = 45, 1 RCT, RR 1.39 CI 1.06 to 1.83).

Authors' conclusions

There is currently no convincing evidence to confirm or refute the practise of administering benzodiazepines as monotherapy or in combination with antipsychotics for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychosis. Low‐quality evidence suggests that benzodiazepines are effective for very short‐term sedation and could be considered for calming acutely agitated people with schizophrenia. Measured by the overall attrition rate, the acceptability of benzodiazepine treatment appears to be adequate. Adverse effects were generally poorly reported. High‐quality future research projects with large sample sizes are required to clarify the evidence of benzodiazepine treatment in schizophrenia, especially regarding long‐term augmentation strategies.

Keywords: Humans, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/adverse effects, Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use, Benzodiazepines, Benzodiazepines/adverse effects, Benzodiazepines/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia

Antipsychotic drugs are the primary method of treatment for people suffering from mental illness. However, many people with mental health problems do not respond well to antipsychotics which often are very good at treating positive symptoms (e.g. hearing voices or seeing things), but not so good for negative symptoms (e.g. loss of emotions, inactivity). In addition, antipsychotics can sometimes cause debilitating side effects such as movement disorders, weight gain, sleepiness and dizziness. If someone does not respond well to traditional antipsychotic drugs, psychiatrists are faced with the choice of switching to a different type of drug that may work better on its own; or adding a new drug or drugs to supplement the original antipsychotic drug treatment.

Benzodiazepines can be taken alone or in combination with more traditional antipsychotic drugs. They cause sedation, calmness and relax the muscles, so are helpful in calming down agitated people with anxiety, sleep problems, seizures, alcohol withdrawal and acute mental health problems.

This review found 34 studies with 2657 people. It compared benzodiazepines when used alone as the only medication or when used in combination with another drug for people with schizophrenia. Information from the 34 studies was generally poor, incomplete and badly reported. The 34 studies were of short duration and were small in size. The review suggests that there is little evidence to support the use of benzodiazepines either alone or in combination. However, benzodiazepines do have sedative properties that can calm people down and help them become less agitated for short periods of time. More research, particularly involving benzodiazepines as add‐on treatment used in combination with traditional antipsychotic drugs, is required.

This plain language summary has been written by Benjamin Gray, Service User and Service User Expert, Rethink Mental Illness, Email: ben.gray@rethink.org.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. BENZODIAZEPINES AS SOLE TREATMENT versus PLACEBO AS SOLE TREATMENT for schizophrenia.

| Benzodiazepines as sole treatment versus placebo as sole treatment for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Setting: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: benzodiazepines as sole treatment versus placebo as sole treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Benzodiazepines as sole treatment versus placebo as sole treatment | |||||

| No clinically important response to treatment ‐ short term | 667 per 1000 | 447 per 1000 (293 to 680) | RR 0.67 (0.44 to 1.02) | 382 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Leaving the study early due to any reason (overall acceptability of treatment) | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 0.89 (0.57 to 1.38) | 440 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5 | |

| Leaving the study early due to adverse effects (overall tolerability of treatment) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 161 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6,7 | |

| Number of participants tranquillised at endpoint of the study (Desired sedation/tranquillisation) | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | No included trial provided data for that outcome. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes8. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Serious study limitations: High risk of bias regarding outcome data reporting in Merlis 1962 and attrition in two trials (Gundlach 1966; Hankoff 1962). 2 Substancial level of heterogeneity. 3 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval around the pooled risk ratio includes both "no effect" and "appreciable benefit". Downgraded by 1. 4 High risk of bias regarding outcome data reporting in Merlis 1962 and attrition in two trials (Gundlach 1966; Hankoff 1962). Nishikawa 1982 used a cross‐over design. 5 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval around the pooled risk ratio and the best estimate of effect includes both "no effect" and "appreciable benefit". Downgraded by 1. 6Merlis 1962 was characterised by incomplete outcome data reporting and Nishikawa used a cross‐over study design. 7 There were only few studies included that were characterised by a small sample size; one of these used a cross‐over design (Nishikawa 1982) and another one reported outcome data incompletely (Merlis 1962).

8 The basis for the assumed risk was the risk in the pooled control group of the relevant studies.

Summary of findings 2. BENZODIAZEPINES versus ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia.

| Benzodiazepines versus antipsychotics for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Setting: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: benzodiazepine monotherapy versus antipsychotic monotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Benzodiazepines versus antipsychotics | |||||

| No clinically important response to treatment ‐ ultra short term (at 60 minutes) | 286 per 1000 | 174 per 1000 (57 to 532) | RR 0.61 (0.2 to 1.86) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| No clinically important response to treatment ‐ ultra short term (at 12 hours) | 514 per 1000 | 386 per 1000 (226 to 668) | RR 0.75 (0.44 to 1.3) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | |

| No clinically important response to treatment ‐ short term | 150 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 (96 to 519) | RR 1.48 (0.64 to 3.46) | 112 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | |

| Leaving the study early due to any reason (overall acceptability of treatment) | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 0.73 (0.45 to 1.18) | 738 (13 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6 | |

| Leaving the study early due to adverse effects (overall tolerability of treatment) | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 13 (0.78 to 216.39) | 444 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low7,8 | |

| Desired sedation ‐ ultra short term ‐ asleep at 12 hours | 514 per 1000 | 386 per 1000 (226 to 668) | RR 0.75 (0.44 to 1.3) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low8 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes10. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The trial was not blinded. 2 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval around the risk ratio includes both "no effect" and "appreciable benefit". Downgraded by 1. 3 Both trials were characterised by incomplete outcome data reporting. 4 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval around the pooled risk ratio and the best estimate of effect includes both "no effect" and "appreciable harm". Downgraded by 1. 5 Two trials were non‐blinded (Garza‐Trevino 1989; TREC‐Rio 2003); Lerner 1979,Merlis 1962 and Hankoff 1962 reported outcome data incomplete and Nishikawa used a cross‐over study design. 6 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval around the best estimate of effect includes both "no effect" and "appreciable benefit". Downgraded by 1. 7TREC‐Rio 2003 was not blinded, Lerner 1979 and Merlis 1962 reported outcome data incompletely and Nishikawa 1982 used a cross‐over trial design. 8 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval of the risk ratio includes both "no effect" and appreciable harm". Downgraded by 1. 9 Both included studies were conducted as open trials.

10 The basis for the assumed risk was the risk in the pooled control group of the relevant studies.

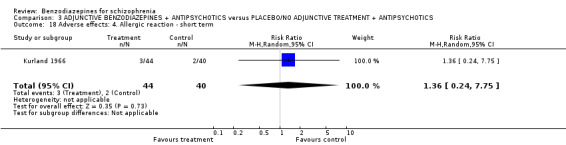

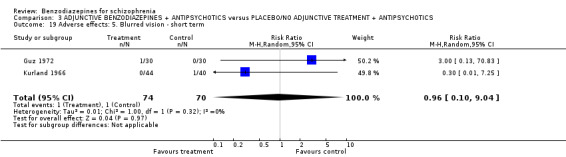

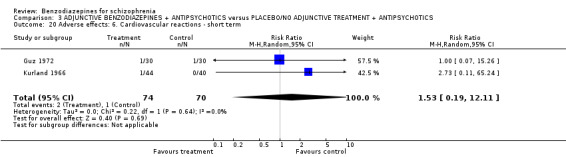

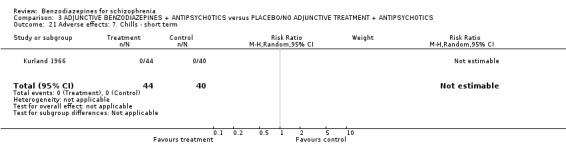

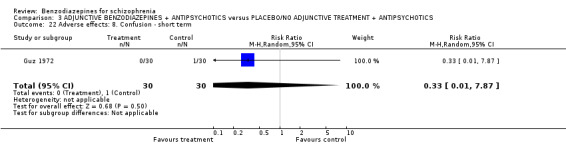

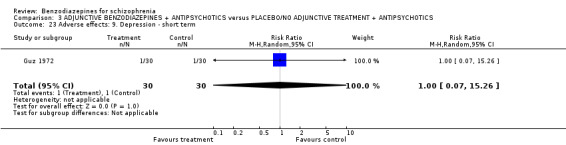

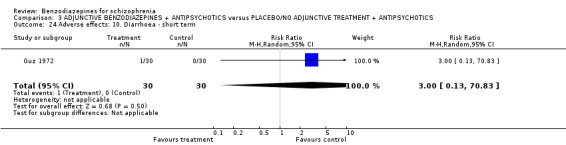

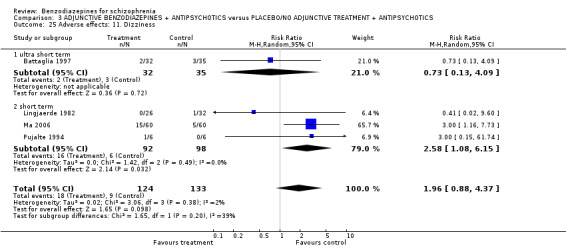

Summary of findings 3. ADJUNCTIVE BENZODIAZEPINES + ANTIPSYCHOTICS versus PLACEBO/NO ADJUNCTIVE TREATMENT + ANTIPSYCHOTICS for schizophrenia.

| Adjunctive benzodiazepines + antipsychotics versus placebo/no adjunctive treatment + antipsychotics for schizophrenia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Setting: inpatients and outpatients Intervention: adjunctive benzodiazepines + antipsychotics versus placebo/no adjunctive treatment + antipsychotics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Adjunctive benzodiazepines + antipsychotics versus placebo/no adjunctive treatment + antipsychotics | |||||

| No clinically important response to treatment ‐ ultra short term (at 60 minutes) | 286 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (0 to 323) | RR 0.07 (0 to 1.13) | 45 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| No clinically important response to treatment ‐ ultra short term (at 12 hours) | 514 per 1000 | 437 per 1000 (262 to 725) | RR 0.85 (0.51 to 1.41) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | |

| No clinically important response to treatment ‐ short term (3 weeks or longer) | 307 per 1000 | 267 per 1000 (150 to 473) | RR 0.87 (0.49 to 1.54) | 511 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | |

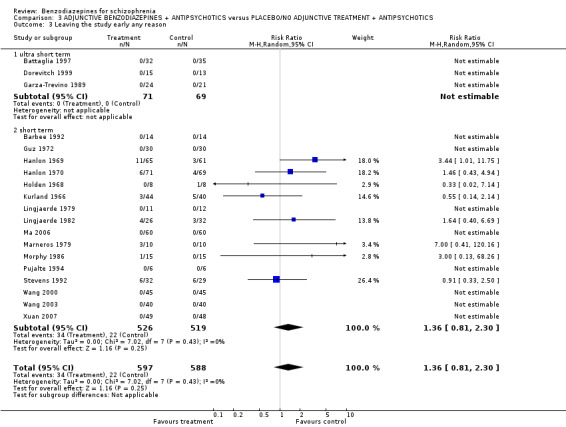

| Leaving the study early due to any reason (overall acceptability of treatment) | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 1.36 (0.81 to 2.3) | 1185 (19 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6 | |

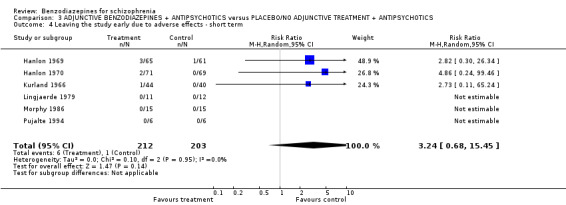

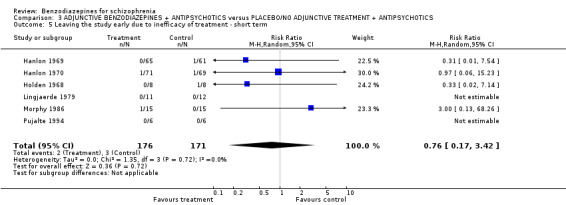

| Leaving the study early due to adverse effects (overall tolerability of treatment) ‐ short term | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 3.24 (0.68 to 15.45) | 415 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low7,8 | |

| Desired sedation ‐ ultra short term ‐ tranquillised at 60 minutes | 714 per 1000 | 992 per 1000 (757 to 1000) | RR 1.39 (1.06 to 1.83) | 45 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Desired sedation ‐ ultra short term ‐ asleep at 12 hours | 514 per 1000 | 437 per 1000 (262 to 725) | RR 0.85 (0.51 to 1.41) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low9 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes10. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The study was not double‐blinded. 2 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval of the risk ratio includes both "no effect" and "appreciable benefit". Downgraded by 1. 3Xuan 2007 was not blinded and Lingjaerde 1982 used a cross‐over study design. 4 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval of the pooled risk ratio includes both "no effect" and "appreciable benefit". Downgraded by 1. 5 Five studies were not blinded und three used a cross‐over design. 6 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval of the pooled risk ratio includes both "no effect" and "appreciable harm". Downgraded by 1. 7 One study used a cross‐over‐design and three were characterised by selective reporting. 8 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval of the pooled risk ratio and best estimate of effect includes both "no effect" and "appreciable harm". Downgraded by 1. 9 Serious imprecision: The 95% confidence interval of the risk ratio includes both "no effect" and "appreciable harm". Downgraded by 1.

10 The basis for the assumed risk was the risk in the pooled control group of the relevant studies.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder. It afflicts approximately one per cent of the population worldwide with little gender differences. Schizophrenia ranks among the seven most frequent causes listed by the WHO for loss of years of life due to disability (WHO 2001). Its typical manifestations are "positive" symptoms such as fixed, false beliefs (delusions) and perceptions without cause (hallucinations), "negative" symptoms such as apathy and lack of drive, disorganisation of behaviour and thought, and catatonic symptoms such as mannerisms and bizarre posturing (Carpenter 1994). The degree of suffering and disability is considerable with 80% to 90% of those affected not working (Marvaha 2004) and up to 10% dying by suicide (Tsuang 1978).

Description of the intervention

Benzodiazepines are mainly characterised by their sedative and muscle‐relaxing properties. Therefore, these compounds are traditionally used for the pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, seizures, and alcohol withdrawal. In schizophrenia, the administration of benzodiazepines can be considered to sedate and calm agitated people with acute schizophrenic episodes (Leucht 2011). The adverse effects that are experienced most frequently are drowsiness, dizziness, problems with concentration, and "paradoxical effects" including irritability, impulsivity as well as seizures. Rare, but very severe adverse effects of benzodiazepines are respiratory depression/arrest in short‐term treatment and, more commonly, the risk of dependence in case of long‐term medication.

Benzodiazepines are often classified according to their elimination half‐live (e.g. short‐acting with less than six hours and long‐acting with more than 24 hours).

How the intervention might work

The mechanism of action of benzodiazepines is characterised by enhanced activity of the inhibiting neurotransmitter GABA (gamma‐aminobutyric acid). The GABA‐A receptor in the synapsis of neurons has specific receptors for benzodiazepines. Interaction of benzodiazepines with these receptors results in a hyperpolarisation through increased opening of chloride ion channels (increase of the membrane potential). These molecular alterations result in an enhancement of GABA‐A receptor activity followed by decline of the excitability of neurons. All in all, these mechanisms cause the calming effects of the benzodiazepines due to reduced synaptic communication between neurons (Benkert 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Antipsychotic drugs can be regarded as core treatment for both, acute and long‐term treatment of schizophrenia (Falkai 2005; Falkai 2006). The effectiveness of antipsychotics in schizophrenia could be demonstrated in a wide range of randomised controlled trials (Leucht 2009). But many people with schizophrenia do not achieve full remission of symptoms despite adequate antipsychotic drug treatment. At the present time, clozapine is considered as gold standard in the case of treatment‐resistance (Essali 2009), but due to its risk profile (especially in terms of agranulocytosis), most guidelines recommend clozapine administration only after non‐response to at least two adequate trials with different other antipsychotic compounds (Leucht 2011). However, many individuals with psychoses fail to respond satisfactorily to conventional treatment with first‐ and second‐generation antipsychotics, and clinicians are often faced with the choice of switching to alternate types of medication, or augmenting existing antipsychotics with other drugs or treatment options.

Therefore, the evaluation of additive therapeutic strategies in the presence of remaining relevant schizophrenic symptoms has high clinical relevance. Over the last forty years a variety of adjunctive treatment options have been evaluated concerning effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia (Christison 1991). In this context, the administration of various compounds such as carbamazepine (Leucht 2007a), lithium (Leucht 2007b), benzodiazepines, beta‐blockers (Cheine 2001) and valproate (Schwarz 2008) were examined in people with psychosis refractory to antipsychotic monotherapy. Additionally to the pharmacological approaches, other somatic therapy strategies such as electroconvulsive therapy have also been evaluated for people with schizophrenia (Tharyan 2005).

In this systematic review we examine the role of benzodiazepines in the treatment of schizophrenia. Companion reviews of our work‐group have examined the anticonvulsant carbamazepine (Leucht 2007a), lithium (Leucht 2007b) and valproate (Schwarz 2008) as sole or adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia. In contrast to this systematic review, another Cochrane review examined the effectiveness of benzodiazepines in acute psychoses irrespective of the underlying diagnosis (Gillies 2005), while we only included studies on schizophrenia and related disorders.

Objectives

To review the effectiveness of benzodiazepines for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychoses, including examining whether:

benzodiazepines monotherapy is an effective treatment option for schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychoses; and

benzodiazepine augmentation of antipsychotic medication is an effective treatment for the same illnesses.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We only included studies that randomly assigned participants with schizophrenia or related disorders. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies such as those using allocation by day of the week, date of birth, alternate allocation. This decision is based on the evidence of a strong relationship between allocation concealment and direction of effect (Schulz 1995).

If a trial was described as "double‐blind", but randomisation was not explicitly mentioned, we implied that the study was randomised and assessed the inclusion of the trial in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) when these "implied randomisation" studies were added, then we included these in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, we only analysed clearly randomised trials and described the results of the sensitivity analysis in the text.

Where people were given additional medications within the treatment group receiving benzodiazepines, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and it was only the medication with benzodiazepines that was randomised.

Randomised cross‐over studies were eligible, but only data up to the point of first cross‐over were used to avoid biases due to carry‐over effects of the treatments (Elbourne 2002).

Types of participants

We included people with the main diagnosis of schizophrenia and other types of schizophrenia‐like psychoses (e.g. schizophreniform, schizoaffective, or delusional disorders), irrespective of the diagnostic system applied. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia‐like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994). In accordance with the general strategy of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group (Adams 2011), we also included studies that had used other diagnostic criteria than those of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). These diagnostic criteria are not meticulously used in clinical routine either, so broader inclusion criteria will enhance generalisability and representativeness. Trials randomising people with schizophrenia were included without restrictions concerning age, gender, and comorbidities.

To be included, at least 50% of the participants within a trial had to have a schizophrenic syndrome, or the results exclusively regarding the participants with schizophrenia were provided by the authors.

Types of interventions

Benzodiazepine alone.

Placebo (or no intervention).

Benzodiazepine in combination with any antipsychotic treatment: any dose.

Antipsychotic treatment (any dose).

Antipsychotic treatment (any dose) in combination with placebo (or no intervention).

Benzodiazepines could be applied in any dose and any route of administration (e.g. oral tablets, oral liquids, intramuscular injections, or intravenous injections).

Types of outcome measures

We grouped all outcomes by time ‐ ultra short term (up to 24 hours), short term (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13 to 26 weeks) and long term (over 26 weeks).

Primary outcomes

1. No clinically important response to treatment.

We defined this as less than 50% reduction from the baseline value of a rating scale such as the "Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale" (PANSS; Kay 1987) or the "Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale" (BPRS; Overall 1962) because validation studies have shown that this definition is clinically meaningful (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b; Leucht 2006). If these data were not available, we used the definition provided in the included studies.

Secondary outcomes

1. Leaving the study early

1.1 Leaving the study early due to any reason (as a measure of overall acceptability) 1.2 Leaving the study early due to adverse effects (as a measure of overall tolerability) 1.3 Leaving the study early due to inefficacy of treatment (as a measure of overall efficacy)

2. Global state

2.1 Average score/change of the global state 2.2 Relapse ‐ as defined by each of the studies

3. Mental state

3.1 No clinically significant improvement of the general mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.2 Average score/change of the general mental state 3.3 No clinically significant response in terms of anxiety ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.4 Average score/change of anxiety 3.5 No clinically significant response in terms of positive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.6 Average score/change of positive symptoms 3.7 No clinically significant response in terms of negative symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.8 Average score/change of negative symptoms 3.9 No clinically significant response in terms of depressive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.10 Average score/change of depressive symptoms 3.11 No clinically significant response in terms of manic symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.12 Average score/change of manic symptoms 3.13 Number of participants with clinically desired sedation 3.14 Average score/change of vigilance

4. Behaviour

4.1 General behaviour 4.2 Specific behaviours 4.2.1 Social functioning 4.2.2 Aggression against self, others, or property

5. Service utilisation

5.1 Days in hospital 5.2 Change in hospital status

6. Adverse effects

6.1 General adverse effects ‐ total number of patients with adverse effects 6.2 Specific adverse effects

7. Economic outcomes

7.1. Average change in total cost of medical and mental health care 7.2. Total indirect and direct costs

Search methods for identification of studies

No language restriction was applied to avoid the problem of "language bias" (Egger 1997b).

Electronic searches

The search methods for this 2011 update are documented below, for previous searches see Appendix 1.

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (February 2011)

We searched the register using the phrases:

[*abecarnil* OR *adinazolam* OR *AHN 086* OR *alpidem* OR *alprazolam* OR *anthramycin* OR *arfendazam* OR *azepam* OR *bentazepam* OR *benzodiazepine* OR *bretazenil* OR *bromazepam* OR *brotizolam* OR *CGS 20625* OR *CGS 8216* OR *CGS 9895* OR *CGS 9896* OR *chlordiazepoxide* OR *ciclotizolam* OR *ciprazafone* OR *clobazam* OR *clonazepa* OR *clotiazepam* OR *CP 32961* OR *DBCE* OR *devazepide* OR *dextofisopam* OR *diazepam* OR *dikaliumclorazepat* OR *divaplon* OR *dulozafone* OR *ELB 139* OR *emapunil* OR *endixaprine* OR *eszopiclone* OR *etizolam* OR *FG 7142* OR *flumazenil* OR *flunitrazepam* OR *flurazepam* OR *flutazoram* OR *GABA* OR *gedocarnil* OR *girisopam* OR *imidazenil* OR *JL 13* OR *KC 5944* OR *L 365260* OR *lorazepam* OR *lormetazepam* OR *lorzafone* OR *magnesium* OR *MCC* OR *medazepam* OR *metaclazepam* OR *midazolam* OR *nerisopam* OR *nitrazepam* OR *nordazepam* OR *oxazepam* OR *pazinaclone* OR *PBCC* OR *perlapine* OR *pinasepam* OR *pipequaline* OR *Pirenzepine* OR *PK 11195* OR *prazepam* OR *premazepam* OR *quazepam* OR *radequinil* OR *reclazepam* OR *ricasetron* OR *rilmazafone* OR *Ro 15‐4513* OR *Ro 19‐5686* OR *Ro 5‐4864* OR *sarmazenil* OR *SL 75102* OR *SR 95195* OR *suriclone* OR *temazepam* OR *tiagabine* OR *timelotem* OR *tofisopam* OR *tracazolate* OR *trepipam* OR *triazolam* OR *triflubazam* OR *Y 23684* OR *zaleplon* OR *zalospirone* OR *ZAPA* OR *ZK 90798* OR *ZK 91296* OR *ZK 93423* OR *zolam* OR *zolpidem* OR *zopiclone* in interventions of STUDY]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (http://szg.cochrane.org/cochrane‐schizophrenia‐group‐specialised‐register).

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the references of all identified studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first/corresponding author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials and for missing information.

Data collection and analysis

Methods used in data collection and analysis for this update are documented below, for previous methods please see Appendix 2.

Selection of studies

Review authors MD and CL inspected all abstracts of studies identified as above and identified potentially relevant reports. In addition, to ensure reliability, MT and SL inspected a random sample of these abstracts, comprising 10% of the total. Where disagreement occurred this was resolved by discussion, or if there was still doubt, the full article was acquired for further inspection. The full articles of relevant reports were acquired for reassessment and carefully inspected for a final decision on inclusion (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). Once the full articles were obtained, in turn MD and CL inspected all full reports and independently decided whether they met the inclusion criteria. MD and CL were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, or journal of publication. Where difficulties or disputes arose, we asked author SL for help and if it was impossible to decide, we added these studies to those awaiting assessment and contacted the authors of the papers for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Review authors MD and CL extracted data from all included studies. In addition, to ensure reliability, MT independently extracted data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. Again, any disagreement was discussed, decisions documented and, if necessary, we contacted the authors of studies for clarification. With remaining problems, SL helped to clarify issues and these final decisions were documented. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible but included the data only if two review authors independently had the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. If studies were multicentre, wherever possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data on standard simple forms.

2.2 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) which can be difficult to conduct in unstable conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We combined endpoint and change data in the analysis as we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.3 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion: (a) data from studies of at least 200 participants were entered in the analysis irrespective of the following rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies; (b) endpoint data: when a scale starts from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation. If this value was lower than one, it strongly suggested a skew and the study was excluded. If this ratio was higher than one but below two, there is suggestion of skew. We entered the study and tested whether its inclusion or exclusion substantially changed the results. If the ratio was larger than two the study was included, because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011). (c) change data: when continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. We entered the study, because change data tend to be less skewed and because excluding studies would also lead to bias, because not all the available information was used.

In case of skewness we displayed the data in an 'other data table' and did not calculate effect sizes. These tables can be found within the section "data analysis".

2.4 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.5 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into "clinically improved" or "not clinically improved". It can be generally assumed that if there is a reduction less than 50% in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered as "No clinically significant response" (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.6 'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used GRADE profiler (GRADE Profiler) to import data from RevMan 5 (Review Manager (RevMan)) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the summary of findings table.

1. No clinically important response to treatment

2. Acceptability of treatment

leaving the study early due to any reason

leaving the study early due to adverse effects (tolerability of treatment)

3. Desired sedation/tranquillisation

number of participants tranquillised at endpoint of the study (ultra short term)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (MD, CL, MT) worked independently to assess risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to measure trial quality. This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. We did not include studies in this systematic review if sequence generation was inadequate.

If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus, with the involvement of another member of the review group (SL). Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted the authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. Non‐concurrence in quality assessment was reported, but if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again, resolution was made by discussion.

The level of risk of bias was noted in both, the text of the review and in the Table 1; Table 2; Table 3.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Dichotomous data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000).

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we estimated mean differences (MDs) between groups with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ "cluster randomisation" (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data pose problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation (ICC) in clustered studies, leading to a "unit of analysis" error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

If clustering had not been accounted for in primary studies, we planned to present data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. If in subsequent versions of this review we include cluster trials, we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain ICCs for their clustered data and will adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study but adjust for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a "design effect". This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported it will be assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we only used data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant, the additional treatment arms were presented in comparisons. If data are binary these were simply added and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). The loss to follow‐up in randomised schizophrenia trials is often considerable calling the validity of the results into question. Nevertheless, it is unclear what degree of attrition leads to a high degree of bias. We did not exclude data from trials on the basis of the percentage of participants completing them. We, however, used the 'Risk of bias' tool described above to indicate potential bias when more than 25% of the participants left the studies prematurely, when the reasons for attrition differed between the intervention and the control group, and when no appropriate imputation strategies were applied.

2. Dichotomous data

Data were presented on a "once‐randomised‐always‐analyse" basis, assuming an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. If the authors applied such a strategy, we used their results. If the original authors presented only the results of the per‐protocol or completer population, we assumed that those participants lost to follow‐up would have had the same percentage of events as those who remained in the study.

3. Continuous data

3.1 General

Intention‐to‐treat was used when available. We anticipated that in some studies, in order to perform an ITT analysis, the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leon 2006). Therefore, where LOCF data were used in the analysis, it was indicated in the review.

3.2 Standard deviations

If standard deviations(SDs) were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals (CIs) available for group means, and either 'P' value or 't' values available for differences in mean, we can calculate them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011): When only the SE is reported, SDs are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, CIs, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations. When such situations or participant groups arose, these were fully discussed.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods. When such methodological outliers arise these were fully discussed.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

Heterogeneity between studies was investigated by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2011). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). An I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic, was interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). When substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcomes, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997a). These are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots are possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage concerning the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose random‐effects model for all analyses but additionally we investigated the use of a fixed‐model approach in sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, this was reported. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, the graph was visually inspected and outlying studies were successively removed to see if heterogeneity was restored. For this review, we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, data were presented. If not, data were not pooled and issues discussed. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut off but are investigating use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious, we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not perform further analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

All sensitivity analyses were only applied for the primary outcome.

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as implied randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we included these studies in sensitivity analyses and if there were no substantive differences when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then all data were employed from these studies.

2. Implication of non double‐blind trials

We aimed to assess the exclusion of trials that were not double‐blind in a sensitivity analysis.

3. Fixed versus random‐effects models

All data were synthesised using a random‐effects model, however, we also calculated data for the primary outcome using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether the greater weights assigned to larger trials with greater event rates, altered the significance of the results compared with the more evenly distributed weights in the random‐effects model.

Results

Description of studies

Please also see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

The initial search strategy identified more than 180 citations, of which about 100 were clearly unrelated to the topic of this review. We obtained and inspected 82 articles. Forty‐one studies were excluded and a further three studies are awaiting assessment. Overall 31 studies were included.

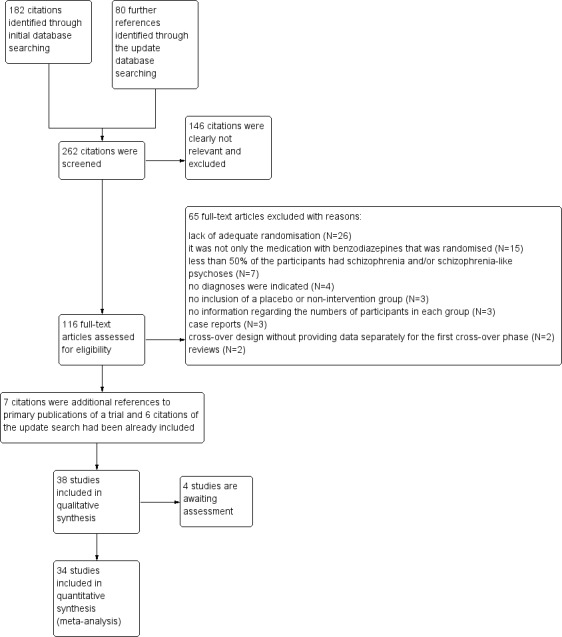

The update search in February 2011 yielded 80 further references of which 34 were potentially relevant and were regarded more closely. Three of these reports were included (Wang 2000; Ma 2006; Xuan 2007) and 24 studies were excluded and the reasons for exclusion documented in the Characteristics of included studies table. One citation could be a further relevant randomised trial (Davis 2008), but due to insufficient information it had to be classified as awaiting assessment. We have written to the corresponding author. Six references retrieved in the update search were reports of studies that had been already included in the first version of this review (a flowchart of the systematic literature search is provided in Figure 1). This systematic review now includes 34 studies while 66 reports are listed in the excluded studies table and four studies are still awaiting assessment.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The 34 included studies were published between 1962 and 2007. Most of the studies were published in English, four in Chinese (Wang 2000; Wang 2003; Ma 2006; Xuan 2007) and one study in German (Marneros 1979).

2.1 Methods

All studies were randomised ("implied randomisation" in case of Marneros 1979) and most used double‐blind‐blind methodology. For further details please see sections below on allocation and blinding.

2.2 Study design

Thirty studies had a parallel group design, whereas four were designed as cross‐over studies (Holden 1968; Lingjaerde 1979; Lingjaerde 1982; Nishikawa 1982). No trial employed a cluster randomisation. Regarding dealing with missing data, many studies did not clearly indicate which analysis method was applied. Some stated the use of a completers‐only analysis, whereas, no trial report mentioned a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach.

2.3 Duration

In 25 studies the benzodiazepines were administered over a short‐term period from one to 10 weeks (N = 25), in seven studies over an ultra short‐term period ‐ up to 24 hours, and in two studies (Cheung 1981; Nishikawa 1982) over a long‐term period (from 18 months to three years).

2.4 Participants

The 34 studies included a total of 2657 people. The number of people included in each study ranged from 12 (Nestoros 1982) to 301 (TREC‐Rio 2003). Nineteen studies included only persons with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like psychosis. The applied diagnostic criteria varied to a considerable degree because the studies were carried out at different times during a period of 45 years. Fifteen studies additionally included people with other diagnoses. They were included because at least 50% of the trial sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like psychosis. There was one exception to this rule. Azima 1962 included 184 persons of which only 22 were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like psychosis, but the data used in this analysis exclusively refer to the 22 people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia‐like psychosis.

2.5 Setting

Eighteen trials included exclusively inpatients, five trials randomised outpatient participants. One study included both, inpatients and outpatients (Lingjaerde 1979), and another trial was conducted in an emergency room (TREC‐Rio 2003). There was no information regarding the setting available for the remaining nine trials examined in this review.

2.6 Interventions

Seven studies compared benzodiazepine as a sole agent with placebo and 13 trials compared benzodiazepines with antipsychotic drugs both given as monotherapy. Twenty included studies examined the effects of benzodiazepines as add‐on medication to antipsychotic compounds. Diazepam (N = 7) and chlordiazepoxide (N=7) were the most frequently administered benzodiazepines followed by clonazepam (N = 6) and lorazepam (N = 5). Other benzodiazepines such as alpidem, alrazolam, camazepam, estazolam, flunitrazepam, and midazolam were given in only a few cases. Dose of medication varied due to the duration of the studies and due to the mode of administration (see Characteristics of included studies).

The most often administered antipsychotic drug was haloperidol (N = 13) followed by chlorpromazine (N = 4). Occasionally fluphenazine, thioridazine or risperidone were given. Some studies did not indicate the antipsychotic used, but it was stated that the dose of the antipsychotic agents was kept constant.

2.7 Outcomes

2.7.1 No clinically important response to treatment

The primary outcome criteria "no clinically important response to treatment" was reported only by a limited number of the included studies (16 trials).

2.7.2 Rating scales

Different rating scales were used to assess clinical response and adverse effects. Details of scales that provided usable data are shown below. Reasons for exclusion of data from other instruments are given under "outcomes" in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.7.2.1 Global state

2.7.2.1.1 Clinical Global Impression ‐ CGI (Guy 1976) A rating instrument commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery. Chouinard 1993 and Foster 1997 reported data from this scale.

2.7.2.2 Mental state

2.7.2.2.1 Agitated Behaviour Scale ‐ ABS (Corrigan 1989) This is a 14‐item scale used for monitoring agitation levels. This scale has been applied in emergency department settings. The means and standard deviations for the total score and subscale scores are based on samples of persons with traumatic brain injury treated during the acute phases of recovery on an inpatient rehabilitation unit. A prospective sample of all participants with brain injuries, regardless of whether they were demonstrating agitation, revealed an overall mean ABS score of 21.01 and a standard deviation of 7.35 (Corrigan 1989). Battaglia 1997 used this scale.

2.7.2.2.2 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) A brief rating scale used to assess the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms. The scale has 18 items, and each item can be defined on a seven‐point scale varying from "not present" (1) to "extremely severe" (7). Scoring goes from 18 ‐126. Barbee 1992; Minervini 1990; Foster 1997; Wang 2000; Ma 2006 and Xuan 2007 reported data from the BPRS scale. Battaglia 1997 selected eleven psychosis/anxiety items (hostility, suspiciousness, uncooperativeness, unusual thought content, disorganised conceptualisation, hallucinatory behaviour, grandiosity, anxiety, excitement, tension and mannerisms/posturing) and termed this modified version the MBPRS.

2.7.2.2.3 Inpatient Multidimensional Psychiatric Scale ‐ IMPS (Lorr 1962) A rating scale used to assess the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms. Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Further details could not be obtained. Chouinard 1993 reported data from this scale. 2.7.2.2.4 Malamud‐Sands Scale ‐ MMS (Malamud 1947) The scale consists of 19 items which can be divided into three major groups. The first seven comprise behavior items that can be directly observed at the time when the patient is interviewed. The next four are functions which are also objectively observable but which are based on the continuous observations by ward personnel during 24 hours which are reported to the rating psychiatrist. The third group comprises eight functions which can be evaluated only on the basis of an interview and on communication with the participants themselves. Only Merlis 1962 provided data from this scale.

2.7.2.2.5 Positive and Negative Symptom Scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1987) A 30‐item scale used to assess the severity and range of general, positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Each item is defined on a seven‐point severity scale from absent (1) to extreme (7). Scoring goes from 30 ‐210. Wang 2003 used this scale.

2.7.2.2.6 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1989) This six‐point scale contains a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia, affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐associality and attention impairment. Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Barbee 1992 reported data from this scale.

2.7.2.3 Behaviour

2.7.2.3.1 Nurses Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation ‐ NOSIE (Honigfeld 1965) An 80‐item scale with items rated on a five‐point scale from zero (not present) to four (always present). Ratings are based on behaviour over the previous three days. The seven headings are social competence, social interest, personal neatness, cooperation, irritability, manifest psychosis and psychotic depression. The total score ranges from zero to 320 with high scores indicating a poor outcome. Chouinard 1993 reported data from this scale.

2.7.2.4 Adverse effects

2.7.2.4.1 Simpson Angus Scale ‐ SAS (Simpson 1970) This 10‐item scale, with a scoring system of zero to four for each item, measures drug‐induced parkinsonism, a short term drug‐induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism. Foster 1997 used this scale.

2.7.2.4.2 Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale/Form ‐ TESS/F (Guy 1976) This checklist assesses a variety of characteristics for each adverse effects, including severity, relationship to the drug, temporal characteristics (timing after a dose, duration and pattern during the day), contributing factors, course, and action taken to counteract the effect. Symptoms can be listed a priori or can be recorded as observed by the investigator. Ma 2006 reported data from this scale.

2.7.3 Missing outcomes

The primary outcome criteria "No clinically important response to treatment" was incompletely reported by the included studies. Special aspects, as for example, aggression and manic symptoms, were evaluated only by very few studies. Again, behaviour and adverse effects were incompletely reported. No data were available for economic consequences of treatment.

Excluded studies

Sixty‐five studies were excluded and displayed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The reasons for exclusion were that the participants were not randomised (N = 22), the randomisation procedure was inappropriate (N = 4), or in case of adjunct treatment it was not only the medication with benzodiazepines that was randomised (N = 15). Further reasons were that the studies did not include a placebo or non‐intervention group (N = 3), they were designed as cross‐over studies with unusable data of the first cross‐over phase (N = 2), case reports (N = 3), reviews (N = 2), did not report numbers in each group (N = 3), or the participants with schizophrenia and/or schizophrenia‐like psychosis were less than 50% of the trial sample and data were not provided separately for people with schizophrenia (N = 7), or no diagnosis was indicated (N = 4).

Studies awaiting assessment

We contacted the authors of two cross‐over studies (Maculans 1964; Ungvari 1999) to obtain data from the first cross‐over phase. We also contacted a further first author (Salzman 1991) to clarify initial group size and missing standard deviation. We have not yet received feedback from these authors. Another trial is currently awaiting assessment after the update search (Davis 2008)

Ongoing studies

We found no ongoing studies.

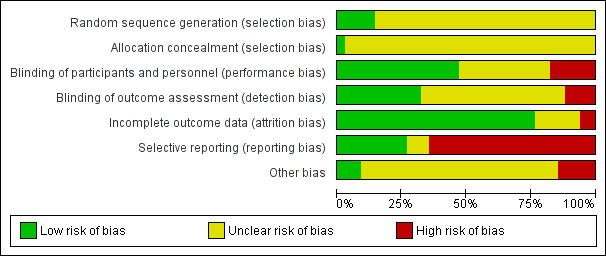

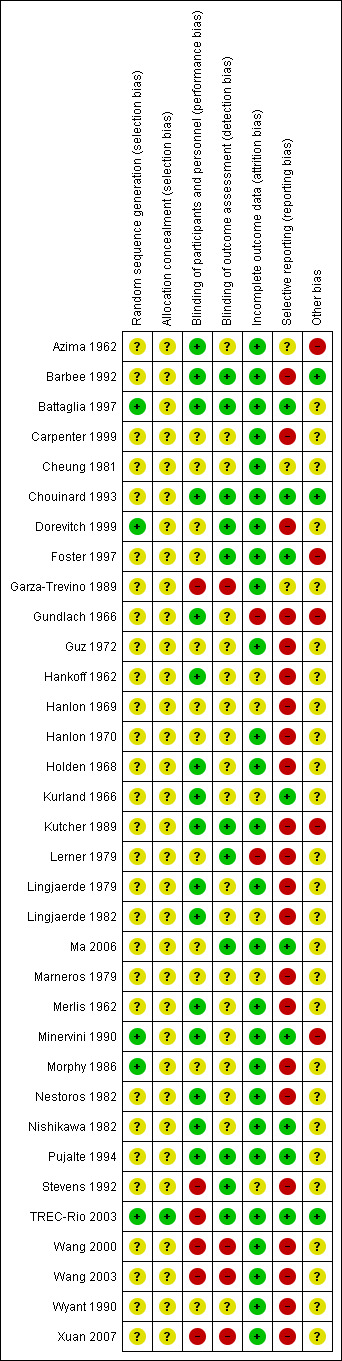

Risk of bias in included studies

For graphical representations of our judgements of risk of bias please refer to Figure 2 and Figure 3. Full details of judgements are provided in the risk of bias tables of the included studies.

2.

3.

Allocation

The participants of three studies (Battaglia 1997; Dorevitch 1999; TREC‐Rio 2003) were assigned by a table of random numbers and two trials were balanced for each group of six participants (Minervini 1990; Morphy 1986). These trials were classified as having a "Low risk of bias" in the quality score ranking. No further details on the randomisation method were available in 24 studies. Three trials stated at least to have used a "stratified randomisation procedure" (Hanlon 1969; Hanlon 1970; Carpenter 1999,) and in one study the randomisation procedure was based on a lottery (Wang 2000). In one publication, no randomisation was mentioned (Marneros 1979). Because the trial was described as "double‐blind" we implied that the study was randomised. All these 31 studies were given the quality score "Unclear risk of bias".

Regarding concealment of allocation, only one study provided enough information to permit judgement of "Low risk of bias" in the quality score (TREC‐Rio 2003).

Blinding

Performance‐Bias: Most of the included studies were declared as "double‐blind". In 10 of these, the trial authors provided no further information concerning the mechanism of blinding ("Unclear risk of bias"), while 16 provided information to allow judgement with "Low risk of bias" in the quality tool. Most of these trials used identical capsules for blinding. Two studies (Wyant 1990; Ma 2006 ) were described as single‐blind without further information ("Unclear risk of bias") and six studies (Garza‐Trevino 1989; Stevens 1992; Wang 2000; Wang 2003; TREC‐Rio 2003; Xuan 2007) were not blinded (classified as "High risk of bias").

Detection‐Bias: 19 publications did not provide enough information to allow classification of high or low risk of bias. In 11 trials, we assessed a "Low risk" for a detection‐bias, while four studies appeared to have a "High risk" regarding this bias (Garza‐Trevino 1989; Wang 2000; Wang 2003; Xuan 2007). The open studies of Stevens 1992 and TREC‐Rio 2003 were blinded for the assessment of the main outcome and therefore classified as "Low risk of bias".

Incomplete outcome data

The overall‐attrition (participants who left the trials early for any indication) was low (< 10%) in 27 trials (rated as "Low risk of bias" with the exception of the study by Kurland 1966 that was characterised by highly different attrition rates in the intervention‐ and control group and therefore classified as "Unclear risk of bias") and moderate (10% to 25%) in five studies (Hankoff 1962; Hanlon 1969; Marneros 1979; Lingjaerde 1982; Stevens 1992). Moderate attrition was judged as "Unclear risk of bias" because the trial authors of these studies did not provide sufficient information to judge if the analysis methods were appropriate to deal with the missing data. In two trials the attrition could be considered as high (> 25%) (Gundlach 1966; Lerner 1979) (rated as "High risk of bias"). Thirteen studies reported the number of participants leaving the study early due to adverse effects and 11 studies reported the number of participants leaving the study early due to inefficacy of treatment. In most of the publications the trial authors used a completers‐analysis.

Selective reporting

The outcome‐data reporting was incomplete in 22 studies (rated as "High risk of bias"). In several instances the data had to be estimated from figures which led to imprecision. Ten trials appeared to be free of selective reporting and were rated with "Low risk of bias" in the quality score, although in many of these publications the reporting of adverse effects was incomplete.

Other potential sources of bias

Only three studies seemed to be free of other potential sources of bias and were assigned a "Low risk of bias" (Cheung 1981; Barbee 1992; TREC‐Rio 2003). In 25 studies the risk of bias was considered as "unclear" due to a lack of available information in the publications. Thus, there was insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists. Two trials were characterised through extreme baseline imbalances regarding the different study groups (Azima 1962; Foster 1997). Other reasons for rating "High risk of bias" are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

1. COMPARISON 1: BENZODIAZEPINES AS SOLE TREATMENT versus PLACEBO AS SOLE TREATMENT

1.1 Primary outcome: No clinically important response to treatment

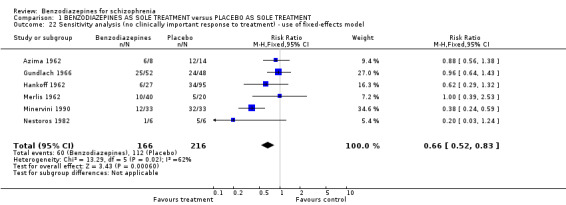

Six short‐term studies (Azima 1962, Gundlach 1966, Hankoff 1962, Merlis 1962, Minervini 1990, Nestoros 1982) reported the number of participants without a clinically significant response to treatment. Combining the data of these trials demonstrated no significant difference in favour of any treatment modality (N = 382, 6 RCTs, RR 0.67 CI 0.44 to 1.02). The I² value of 62% and the significant heterogeneity test (P = 0.02) indicated a substantial level of heterogeneity. The included long‐term studies did not provide data for the primary outcome.

1.2 Secondary outcomes

1.2.1 Leaving the study early

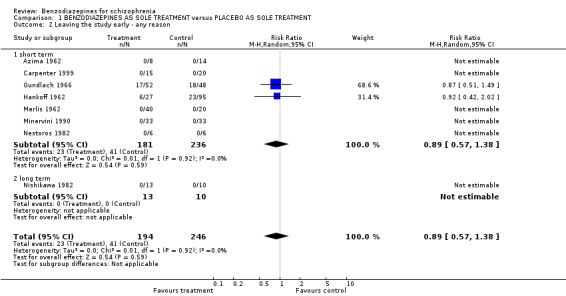

1.2.1.1 Leaving the study early due to any reason

Eight studies contributed data to this outcome. Seven studies were short term and one was long term. In the short‐term studies there was no statistically significant difference between participants treated with benzodiazepines and placebo (N = 417, 7 RCTs, RR 0.89 CI 0.57 to 1.38) and in the long‐term trial, no participant left the trial early (Nishikawa 1982).

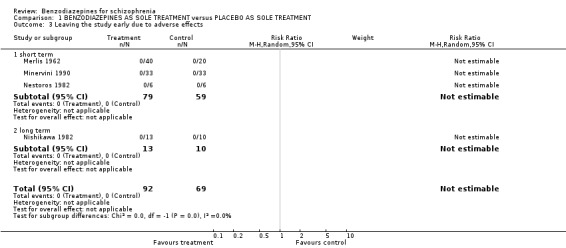

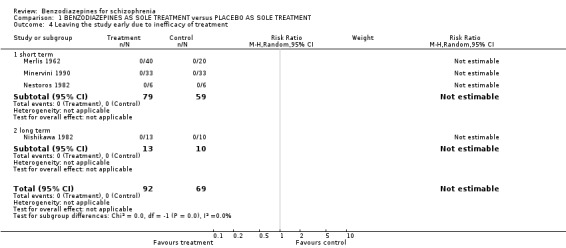

1.2.1.2 Leaving the study early due to adverse effects

Three short‐term studies (Merlis 1962; Minervini 1990; Nestoros 1982) indicated the reason for premature discontinuation was due to adverse effects. As there no one left early in either group, the risk ratio could not be estimated. The same holds true for the only long‐term study (Nishikawa 1982).

1.2.1.3 Leaving the study early due to inefficacy of treatment

Again, four trials (Merlis 1962; Minervini 1990; Nestoros 1982; Nishikawa 1982) stated the number of participants leaving the study early was due to inefficacy of treatment. No attrition was observed.

1.2.2 Global state

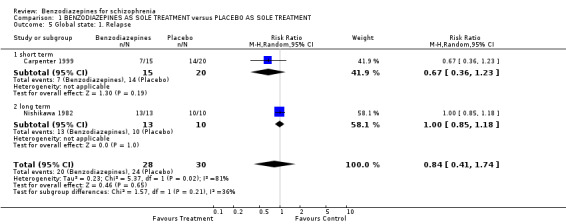

1.2.2.1 Relapse

Two trials reported relapse rates after one year, one short‐term study (Carpenter 1999) and one long‐term study (Nishikawa 1982). We found no significant difference between the treatment and placebo groups in both trials (short term: N = 35, 1 RCT, RR 0.67 CI 0.36 to 1.23; long term: N = 23, 1 RCT, RR 1.00 CI 0.85 to 1.18).

1.2.3 Mental state

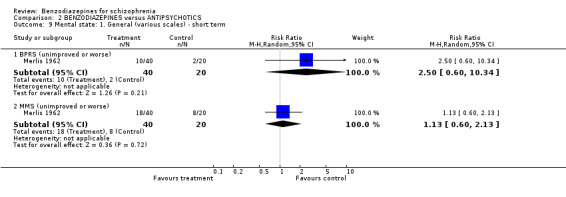

1.2.3.1 General: BPRS and MMS scale

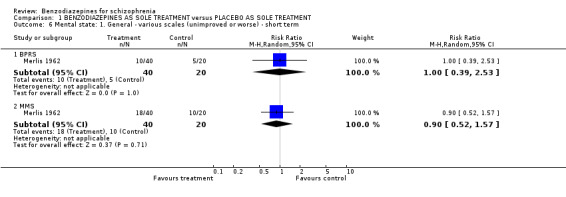

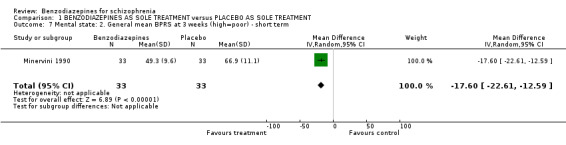

Merlis 1962 analysed the number of participants unimproved or worse according to the BPRS and the MMS total scores. There were no significant differences between groups, neither in terms of the BPRS (N = 60,1 RCT, RR 1.00 CI 0.39 to 2.53), nor in terms of the MMS (N = 60,1 RCT, RR 0.90 CI 0.52 to 1.57). In contrast to the dichotomous data, we found that the mean BPRS scores at three weeks favoured benzodiazepines compared with placebo on a statistically significant level (Minervini 1990, N = 66,1 RCT, MD ‐17.60 CI ‐22.61 to ‐12.59).

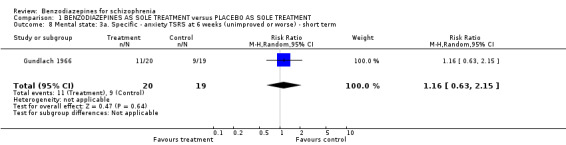

1.2.3.2 Specific: anxiety symptoms (TSRS and HAM‐A scale) Two studies rated anxiety (Gundlach 1966; Minervini 1990) with special scales. Gundlach 1966 used the TSRS at six weeks and found no evidence for significant group difference (N = 39,1 RCT, RR 1.16 CI 0.63 to 2.15). Minervini 1990 employed the HAM‐A rating scale at three weeks and reported a significant advantage in favour of the treatment group. However, data were skewed and could therefore only be displayed in an "other data table".

1.2.4 Adverse effects

1.2.4.1 General: total number of participants with adverse effects

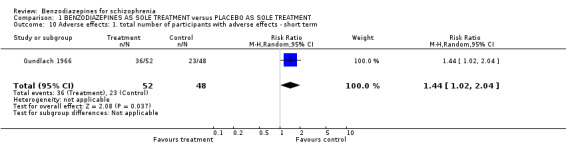

Only Gundlach 1966 analysed how many participants experienced at least one adverse effect. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (N = 100,1 RCT, RR 1.44 CI 1.02 to 2.04, number needed to harm (NNTH) 5 CI 3 to 50) with more participants in the benzodiazepine group suffering from adverse effects than in the placebo group.

1.2.4.2 Specific adverse effects

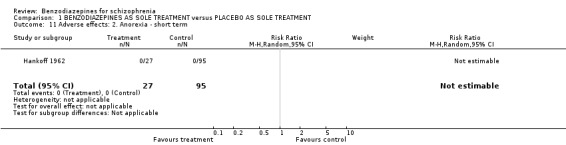

1.2.4.2.1 Anorexia Hankoff 1962 reported on anorexia. No participant experienced this adverse effect (N = 122,1 RCT, RR not estimable).

1.2.4.2.2 Autonomic reactions Gundlach 1966 observed 13 participants in the benzodiazepine group and seven participants in the placebo group with autonomic reactions such as flushing or dry mouth. The difference did not reach statistical significance (N = 100,1 RCT, RR 1.71 CI 0.75 to 3.93).

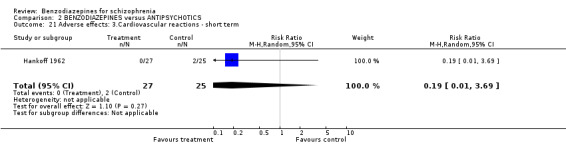

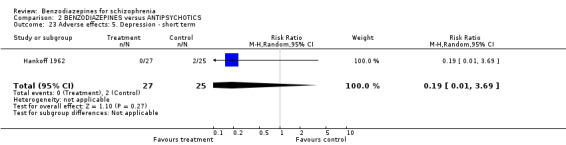

1.2.4.2.3 Cardiovascular reactions, depression and dryness of mouth Hankoff 1962 reported on cardiovascular reactions, depression and dryness of mouth, but no participant in neither group experienced these adverse effects (N = 122,1 RCT, RR not estimable).

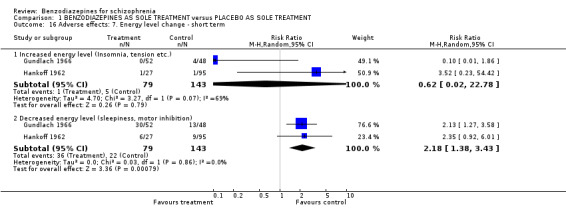

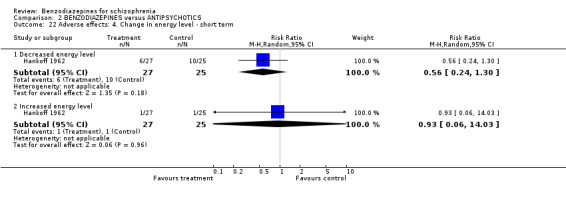

1.2.4.2.4 Energy level Two studies (Hankoff 1962; Gundlach 1966) examined changes in energy level. We found no significant difference regarding an increase in energy level between groups (N = 222, 2 RCTs, RR 0.62 CI 0.02 to 22.78). An I² value of 69% was assessed and the Chi2 test indicated a P value of P = 0.07. For the pooled results of both trials, significantly more participants with a decrease in energy level in the benzodiazepine group than in the control group were identified (N = 222, 2 RCTs, RR 2.18 CI 1.38 to 3.43, NNTH 5 CI 3 to 25).

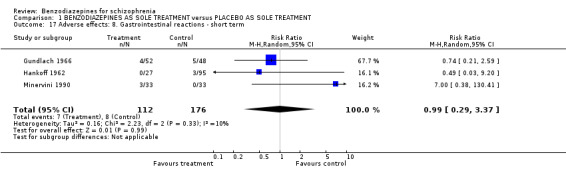

1.2.4.2.5 Gastrointestinal reactions Three studies (Gundlach 1966; Hankoff 1962; Minervini 1990) indicated the numbers of participants experiencing gastrointestinal reactions on the prescribed study medication, but no significant difference between the groups could be identified (3 RCTs, N = 288, RR 0.99 CI 0.29 to 3.37).

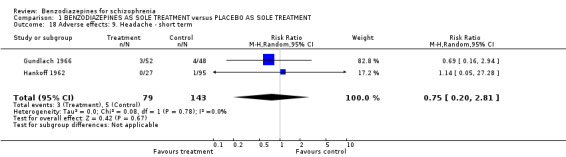

1.2.4.2.6 Headache Regarding headache, there was no significant difference between benzodiazepines and placebo (Gundlach 1966; Hankoff 1962) (N = 222, 2 RCTs, RR 0.75 CI 0.20 to 2.81).

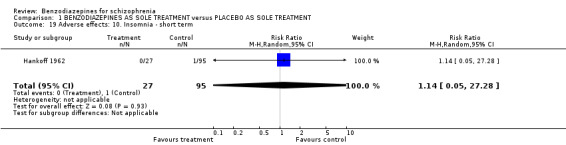

1.2.4.2.7 Insomnia In Hankoff 1962 only one participant in the placebo group complained about insomnia (N = 122,1 RCT, RR 1.14 CI 0.05 to 27.28).

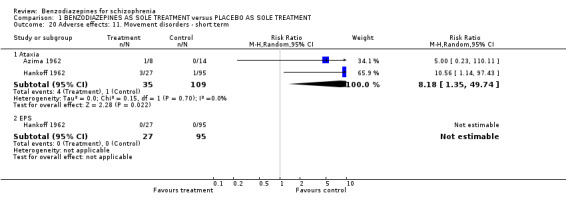

1.2.4.2.9 Movement disorder Two studies (Azima 1962; Hankoff 1962) investigated the occurrence of movement disorders and we found participants in the benzodiazepine group experienced significantly more ataxia compared to the placebo group (N = 144, 2 RCTs, RR 8.18 CI 1.35 to 49.74, NNTH not significant). Hankoff 1962 also reported on EPS in general, but no participant in either group experienced this adverse effect (N = 122,1 RCT, RR not estimable).

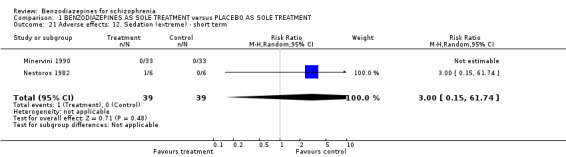

1.2.4.2.10 Sedation Altogether, in two studies (Minervini 1990; Nestoros 1982) only one participant in the pooled benzodiazepine group suffered from extreme sedation (N = 78, 2 RCTs, RR 3.00 CI 0.15 to 61.74).

1.3 Sensitivity analyses

1.3.1 Implication of randomisation

We aimed to conduct a sensitivity analysis in terms of the primary outcome when a trial was not clearly stated to be randomised but described as "double‐blind". This affects no study which contributed data to this comparison. Therefore, the sensitivity analysis was not undertaken.

1.3.2 Implication of non double‐blind trials

No non‐double blind trial was included in the pooled data‐analysis of the primary outcome.Therefore, no sensitivity analysis was conducted.

1.4 Fixed and random effects

When using a fixed‐effect model to analyse the data for the primary outcome, we assessed a statistically significant superiority of benzodiazepines compared with placebo (N = 382, 6 RCTs, RR 0.66 CI 0.5 to 0.8) accompanied by a substantial level of heterogeneity (I² = 62%, heterogeneity test: P = 0.02).

1.5 'Summary of findings' table

The results of three outcomes ‐ no clinically important response to treatment, leaving the study early due to any reason, and leaving the study early due to adverse effects ‐ were considered more closely in a 'Summary of findings' table (see Table 1). The judgements derived from this instrument were used for the discussion section of the review (see Discussion ‐ Summary of main results

2. COMPARISON 2: BENZODIAZEPINES versus ANTIPSYCHOTICS

2.1 Primary outcome: No clinically important response to treatment

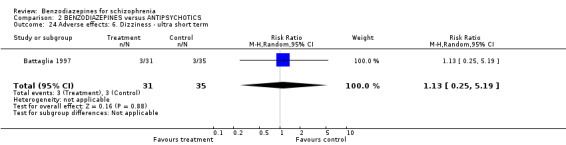

Focussing on global clinical response only four studies (Battaglia 1997; Garza‐Trevino 1989; Hankoff 1962; Merlis 1962) evaluated the number of participants who experienced no clinically significant response to treatment. Garza‐Trevino 1989 investigated the participants after 30 and 60 minutes, Battaglia 1997 after 12 hours, Hankoff 1962 after two weeks, and Merlis 1962 after four weeks. We found no significant differences between groups (30 minutes: N = 44,1 RCT, RR 0.91 CI 0.58 to 1.43; 60 minutes: N = 44,1 RCT, RR 0.61 CI 0.20 to 1.86; 12 hours: N = 66,1 RCT, RR 0.75 CI 0.44 to 1.30; pooled short‐term studies: N = 112, 2 RCTs, RR 1.48 CI 0.64 to 3.46). In summary, no significant evidence was found to suggest that one agent was superior to the other.

2.2 Secondary outcomes

2.2.1 Leaving the study early

2.2.1.1 Leaving the study early due to any reason

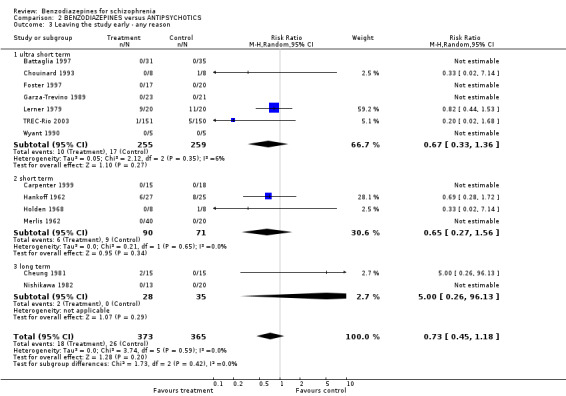

Thirteen studies indicated the number of participants leaving the study early due to any reason. Seven studies were ultra short term, four were short term, and two were long‐term studies. In neither group was the difference between the medication with benzodiazepines and antipsychotics significant (ultra short: N = 514, 7 RCTs, RR 0.67 CI 0.33 to 1.36; short term: N = 161, 4 RCTs, RR 0.65 CI 0.27 to 1.56; long term: N = 63, 2 RCTs, 2 RCTs, RR 5.00 CI 0.26 to 96.13).

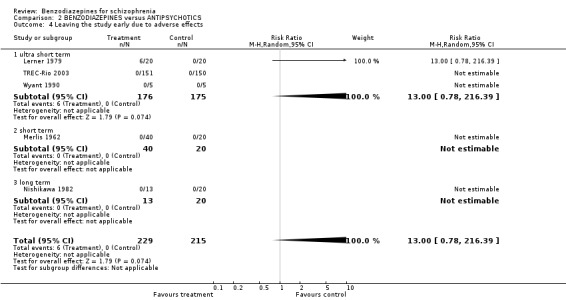

2.2.1.2 Leaving the study early due to adverse effects

Regarding attrition due to adverse terms in three studies of the ultra short‐term category (Lerner 1979; TREC‐Rio 2003; Wyant 1990), no statistically significant difference was found between benzodiazepines and antipsychotics (N = 351, 3 RCTs, RR 13.00 CI 0.78 to 216.39). Only Merlis 1962 and Nishikawa 1982 reported on leaving early due to adverse effects in the short and long term, respectively, but again, no significant differences could be detected between the pooled results of the intervention and control groups (short term: N = 60,1 RCT, RR not estimable; long term: N = 33,1 RCT, RR not estimable).

2.2.1.3 Leaving the study early due to inefficacy of treatment

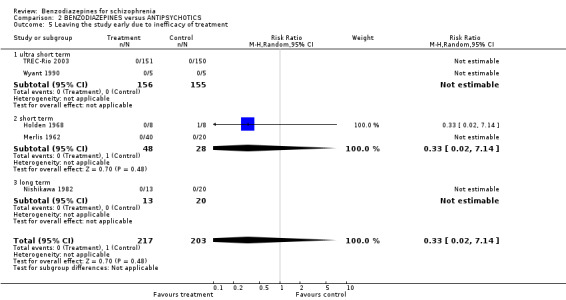

Additionally, there were no significant differences in terms of premature discontinuation due to inefficacy of treatment in either category (ultra short term: N = 311, 2 RCTs, RR not estimable; short term: N = 76, 2 RCTs, RR 0.33 CI 0.02 to 7.14; long term: N = 33,1 RCT, RR not estimable).

2.2.2 Global state

2.2.2.1 CGI severity score

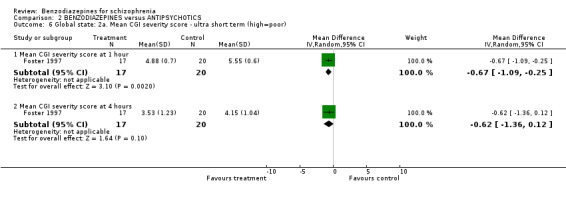

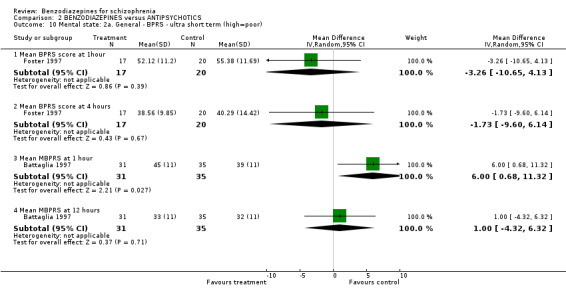

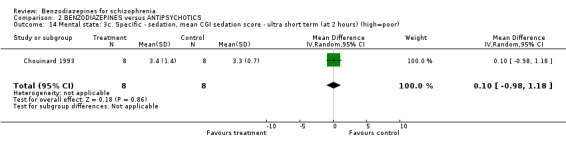

Three studies (Chouinard 1993; Foster 1997; Lerner 1979) reported on the mean CGI severity score at endpoint as a measure of the participants' global state. Foster 1997 assessed one and four hours, Chouinard 1993 two hours, and Lerner 1979 four, and 24 hours. Foster 1997 revealed a statistically significant superiority of benzodiazepines at one hour (N = 37, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.67 CI ‐1.09 to ‐0.25) but not at four hours (N = 37, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.62 CI ‐1.36 to 0.12). The data at two hours (Chouinard 1993), four hours (Lerner 1979), and 24 hours (Lerner 1979) were skewed and could only be displayed in an "other data table".

2.2.2.2 Relapse

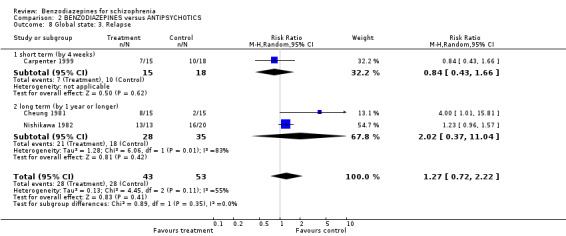

Relapse was reported by Carpenter 1999 at four weeks, and by Cheung 1981 and Nishikawa 1982 at one year or longer. There was no significant between‐group difference in the short‐term study (N = 33, 1 RCT, RR 0.84 CI 0.43 to 1.66) as well as in the pooled overall result of the two long‐term studies (N = 63, 2 RCTs, RR 2.02 CI 0.37 to 11.04). With an I² value of 83% and a significant heterogeneity test (P = 0.01), the heterogeneity between the two long‐term studies (Cheung 1981; Nishikawa 1982) was substantial.

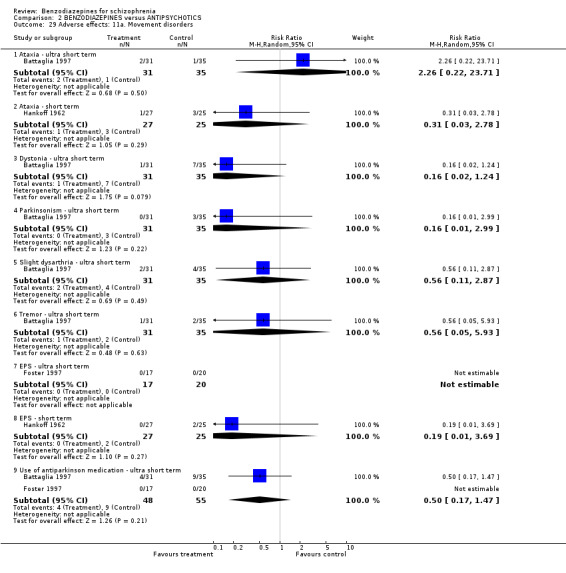

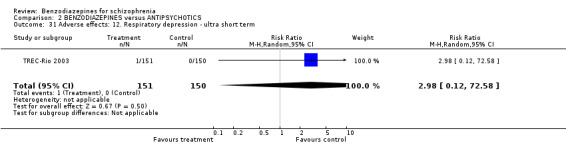

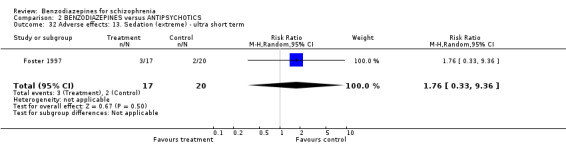

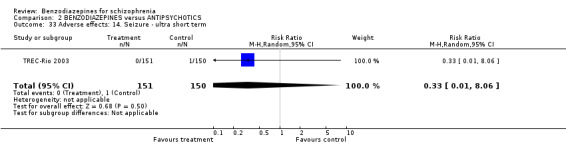

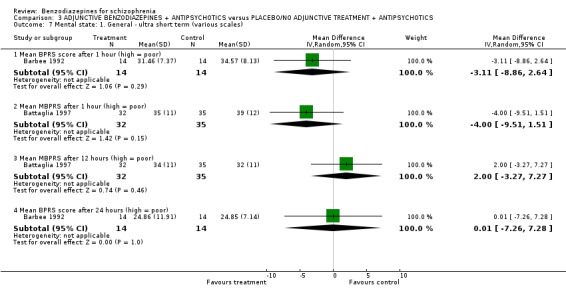

2.2.3 Mental state

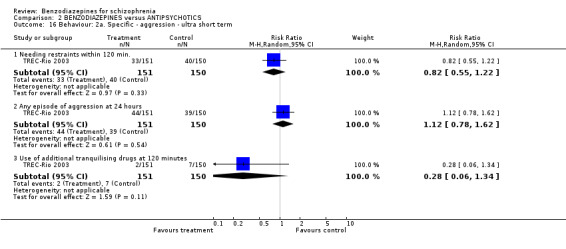

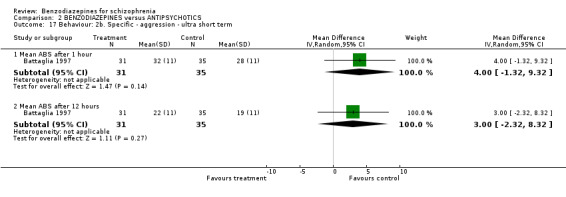

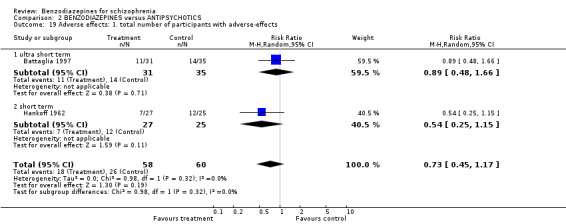

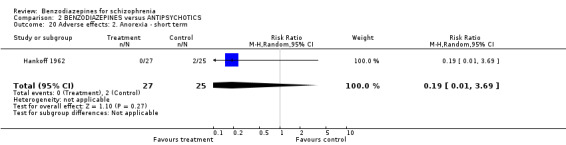

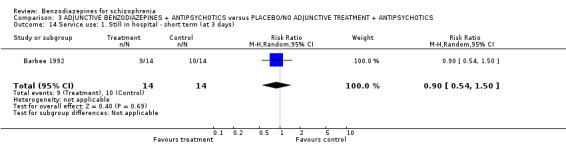

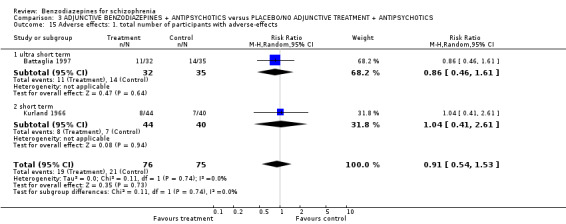

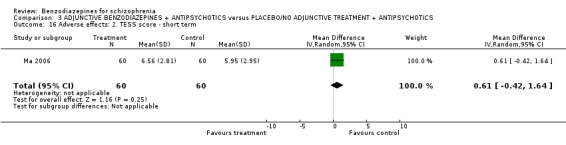

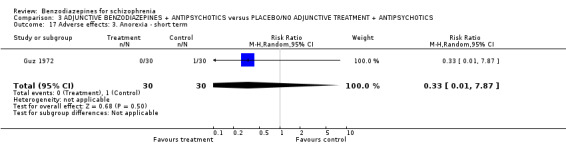

2.2.3.1 General: BPRS, MBPRS and MMS scale