Abstract

Knockdown of the antisense noncoding mitochondrial RNAs (ASncmtRNAs) induces apoptotic death of several human tumor cell lines, but not normal cells, supporting a selective therapy against different types of cancer. In this work, we evaluated the effects of knockdown of ASncmtRNAs on bladder cancer (BCa). We transfected the BCa cell lines UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 with the specific antisense oligonucleotide Andes-1537S, targeted to the human ASncmtRNAs. Knockdown induced a strong inhibition of cell proliferation and increase in cell death in all three cell lines. As observed in UMUC-3 cells, the treatment triggered apoptosis, evidenced by loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and Annexin V staining, along with activation of procaspase-3 and downregulation of the anti-apoptotic factors survivin and Bcl-xL. Treatment also inhibited cell invasion and spheroid formation together with inhibition of N-cadherin and MMP 11. In vivo treatment of subcutaneous xenograft UMUC-3 tumors in NOD/SCID mice with Andes-1537S induced inhibition of tumor growth as compared to saline control. Similarly, treatment of a high-grade bladder cancer PDX with Andes-1537S resulted in a strong inhibition of tumor growth. Our results suggest that ASncmtRNAs could be potent targets for bladder cancer as adjuvant therapy.

Keywords: bladder cancer, antisense therapy, noncoding RNA, apoptosis

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BCa) is the most common malignant tumor of the urinary tract, corresponding to the seventh most common cancer worldwide, with over 549,000 new cases every year and accounting for over 199,000 deaths1. The most common type of BCa (70 - 80%) corresponds to urothelial carcinoma, a non-invasive papillary tumor that progress occasionally. About 20 - 30% of these cases develop into aggressive muscle-invasive carcinoma2, and approximately half of the patients will progress to metastatic disease with a 5-year survival rate of only 5%3. Cisplatin chemotherapy is recommended after radical nephroureterectomy5, albeit displaying high toxicity and low efficacy4-6. To improve survival rates, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies for BCa7.

We reported that the antisense non-coding mitochondrial RNAs (ASncmtRNAs) are promising targets to inhibit tumor growth in pre-clinical models. ASncmtRNA knockdown (ASK for short) with antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) targeted to the ASncmtRNAs, induces strong inhibition in tumor growth in syngeneic murine models of the aggressive murine melanoma cell line B16F108,9 and the renal cell carcinoma line RenCa10. In addition, ASK in several human cell lines in vitro, using ASO Andes-1537, targeted to the human ASncmtRNAs, induces apoptotic cell death together with downregulation of survivin11, an anti-apoptotic factor that is overexpressed in tumor cells12,13. Interestingly, ASK does not affect normal cells, including human keratinocytes (HFK), endothelial cells (HUVEC), normal melanocytes (HnEM) and normal epithelial renal cells (HREC)12.

The ASncmtRNAs belong to a family of mitochondrial long non-coding RNAs containing stem-loop structures that also include a sense member (SncmtRNA)14-16. Interestingly; these transcripts exit the mitochondria to the cytosol and nucleus in normal and tumor cells suggesting a functional role outside the organelle17. SncmtRNA and ASncmtRNAs are differentially expressed according to proliferative status15; normal proliferative cells, but not resting cells, express the SncmtRNA and the ASncmtRNAs. Remarkably however, tumor cell lines and tumor cells in human biopsies of different origins downregulate the ASncmtRNAs15. Based on these results, we proposed that the ASncmtRNAs are tumor suppressors playing an important step in carcinogenesis and represent a new general hallmark of cancer, the last is due that ASncmtRNAs are down regulated, independent of tumor origin, therefore represent a universal signature such as, sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and activating invasion and metastasis15,18.

In the present work, we studied the effects of ASK on the human bladder cancer cell lines UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 and found that in vitro treatment induces a drastic inhibition of proliferation and apoptotic cell death. Moreover, ASK negatively affects the invasive capacity and spheroid formation of UMUC-3 cells, mediated by downregulation of N-cadherin and MMP1119,20. In vivo treatment with Andes-1537 of a UMUC-3 xenograft induced a strong inhibition of tumor growth, compared to controls. Similar results were obtained using a patient derived-xenograft (PDX) from a high-grade BCa patient. Altogether, these results indicate a potential use of the ASncmtRNAs as novel and potent adjuvant therapeutic targets for BCa.

Materials and Methods

Animal studies

Animal studies were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (CONICYT), Chile and approved by the Ethical Committee of Fundación Ciencia & Vida. Immuno-compromised NOD/SCID mice were obtained from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained in the animal facility of the Fundacion Ciencia & Vida under specific pathogen-free conditions (Tecniplast, Buguggiate, Italy) in a temperature-controlled room with a 12/12 h light/dark schedule with sterile food and water ad libitum. Xenograft studies of BCa using the UMUC-3 cell line was carried out essentially as described before8,10. Briefly, 5 x 105 UMUC-3 cells in 100 μl sterile saline were injected subcutaneously (sc) into the left flanks of 10 NOD/SCID mice and tumor growth was monitored every three days with an electronic caliper and tumor volume was estimated with the formula: tumor volume (mm3) = Length x Width2 x 0.5236. When tumors reached a volume of about 100 mm3, mice were randomized into two groups of 5 mice each. For treatment, mice were injected intraperitoneally (ip) every other day with 200 µl saline, either alone or containing 100 µg Andes-1537.

Establishment of a BCa patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model

A tumor specimen was obtained from a patient diagnosed with BCa and subjected to radical bladder resection at the Urology Department of Hospital Barros Luco-Trudeau, Santiago, Chile. The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Board of the Hospital, together with the written informed consent of the patient and was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The pathology report indicated that the sample corresponded to stage T2N0M0. The tumor was preserved in sterile DMEM + antibiotics at 4°C and processed in the laboratory within 3 h. The tumor specimen was sliced into fragments of about 3 mm3 and 4 fragments were implanted sc into both flanks of four 8-week old NOD/SCID mice under anesthesia. After suture, mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions as described before (first generation PDX). Tumor growth was monitored twice a week with an electronic caliper and after reaching a volume of about 600 mm3, tumors were collected by surgery under anesthesia, divided again into fragments of ~3 mm3 and implanted sc into the left flank of 10 8-weeks old NOD/SCID mice (second generation PDX).

Cell culture

The urinary bladder cancer cell lines RT-4 (wild-type p53, mutant CDKN2A and TSC1), T24 transitional cell papilloma (p53- and HRAS-mutated) and transitional cell carcinoma UMUC-3 (p53-, CDKN2A-, KRAS- and PTEN-mutated) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured according to seller´s guidelines. All cell cultures were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) in a humidified cell culture chamber at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cultures were checked periodically for mycoplasma contamination using the EZ-PCR Mycoplasma Test Kit (Biological Industries Israel, Beit Haemek Ltd., Israel). All studies were performed within 2 years of cell purchase and cultures were discarded beyond 6 months after thawing.

To obtain primary cultures of normal human bladder epithelial cells (NBE), a fragment of normal tissue was removed after radical bladder surgery, transferred to the laboratory and dissected into 1-2 mm3 pieces. The tissue was washed three times in PBS at room temperature (RT) and digested for 4 h at 37ºC in RPMI containing 1 mg/ml collagenase I, 2 mg/ml collagenase IV, 1 mg/ml Dispase, 20 μg/ml hyaluronidase and 2000 U/ml DNase I. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 200 x g for 5 min at RT and the pellet was suspended in PBS and again centrifuged for 5 min at 200 x g. The final pellet was suspended in RPMI containing 5% FBS and seeded onto collagen I-coated T25 flasks (Nunc, Walthan, MA, USA) and cultured under normal conditions. Fibroblasts were removed by differential trypsinization10,21.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

Fluorescence detection of SncmtRNA and AsncmtRNAs in cells was performed in suspension according to the protocol described before22.

Chromogenic in situ hybridization

For tissue samples, 5-μm thick serial paraffin sections were collected onto silanized slides (DAKO, Sta Clara, CA, USA) and deparaffinized in 2 consecutive 5 min xylene washes. One section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The others were rehydrated in two 3-min washes of 98% and 90% ethanol each and once in DEPC-treated distilled water for 5 min14,15. Sections were then incubated in 2.5 μg/ml Proteinase K (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at RT for 20 min and then washed twice for 3 min in DEPC-treated water, immersed in 96% ethanol for 10 s and air-dried. In situ hybridization was carried out as described before16 using 35 pmoles/ml digoxigenin-labeled probes targeted to SncmtRNA (5' TGATTATGCTACCTTTGCACGGT) and the ASncmtRNAs (5' ACCGTGCAAAGGTAGCATAATCA) in hybridization solution. Washing and color development were carried out as described before14,15.

Cell transfection

Cells were seeded into 12-well plates (Nunc) at 50,000 cells/well and transfected the next day with 100 nM each ASO, using 2 µg/ml Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen). Transfection was allowed to proceed for 24-72 h under normal culture conditions. ASOs contained 100% phosphorothioate internucleosidic linkages (LGC Biosearch Technology Inc, Novato, CA. USA). The sequences of the ASOs used were 5' CACCCACCCAAGAACAGG (Andes-1537) and 5' TTATATTTGTGTAGGGCTA (non-related control ASO or ASO-C). To assess transfection efficiency, the same ASOs were labeled at the 5' end with Cy-3 (IDT Inc, Corallville. IA, USA).

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer´s instructions. cDNA synthesis was carried out with 100 ng RNA and MMLV reverse transcriptase as described before15,16. PCR reactions were prepared as described14,15 and amplification was performed as follows: 100°C for 10 min, 70°C for 10 min, 80°C for 10 min and 94°C for 5 min, followed by 26 cycles (S and ASncmtRNAs) or 16 cycles (18S rRNA), consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min. Primers used were 5' ACCGTCCAAAGGTAGCATAATCA (forw) and 5' CAAGAACAGGGTTTGTTAGG (rev) for ASncmtRNA-2; 5' TAGGGATAACAGCGCAATCCTATT (forw) and 5'CACACCCACCCAAGAACAGGGAGGA (rev) for ASncmtRNA-1; and 5'GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT (forw) and 5'CATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG (rev) for 18S rRNA.

Cell viability and proliferation assessment

Total cell number and viability was determined by Trypan blue (Tb) or propidium iodide (PI) exclusion. PI was added at 50 μg/ml 1 min before flow cytometry on a BD-FACS Canto Flow Cytometer (Fundación Ciencia & Vida). For Tb, the number of viable and dead cells was determined counting at least 100 cells per sample in triplicate under an Olympus BX-53 fluorescence microscope. Cell proliferation was assessed by using the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2, 5 diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) assay. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 3,000 cells/well. At 0, 24, 48 and 72 h post-transfection, 20 µl/well of 5 mg/ml MTT was added and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. DMSO was then added (150 µl/well) and incubated for 10 min at RT. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm in an Epoch microplate reader (Biotek, Winossky, VT, USA).

Mitochondrial depolarization (ΔΨm)

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates and transfected for 24 h as described above. Afterwards, cells were incubated with 20 nM tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 15 min at 37°C, harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD-FACS canto Flow Cytometer8,10. As positive control, mitochondrial depolarization was elicited using 10 µM carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at 37°C.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from cells as described8 and protein concentration was determined via standard bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) protocol (Pierce, Rockford, Rockford, IL. USA). Cell lysates (30 µg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to polivinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes on a Transblot- Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 25 V for 17 min. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4ºC in blocking solution [5% non-fat dry milk, 0,1% Tween 20 in 1X Tris-buffered saline (TBS)]. On the following day, membranes were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti E-cadherin (1:1000; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), N-cadherin (1:1500; BD Biosciences), MMP-11 (1:2000; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), procaspase-3 (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Bcl-xL (1:500; Abcam) or survivin (1:5000; Abcam), in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. After 3 washes for 5 min at RT in TBST (0,1% Tween-20 in TBS), and membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000; KPL, Milford, MA, USA) for 1h at RT. For loading controls, membranes were probed with mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:4000; Sigma-Aldrich) or anti-GAPDH (1:5000; R&D Systems), followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:2000; KPL) for 1h at RT. After 3 washes in TBST, blots were revealed with the EZ-ECL system (Biological Industries) on a C-DiGit blot Scanner (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). The pixel intensity of each protein band was quantified using Image J software (NIH).

Determination of Phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure

PS exposure was assessed by Annexin-V binding with the AlexaFluor®488-Annexin V/dead Cell apoptosis Kit (Molecular probes), according to manufacturer's instructions and analyzed by flow cytometry8-11.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

Apoptosis was determined by TUNEL, using the Fluorometric in situ Cell Death Detection kit (Promega), according to manufacturer's instructions. Ten high-magnification fields were counted and the proportion of apoptotic (green) cells was determined, as the fraction of total cells. For assessment of apoptosis in vivo after Andes-1537 treatment, tumors from ASO-C- or Andes 1537-treated mice were surgical resected, fixed immediately in neutral-buffered formalin (10%) and paraffin-embedded. Afterward, 5 μm-thick serial paraffin sections were collected on silanized slides (DAKO) and hydrated as described before11,15. The TUNEL procedure was performed using DeadEnd™ Colorimetric Apoptosis Detection System (Promega), according to manufacturer's instruction. As positive control, DNAse I-treated muscle and liver sections were included. Control tumor sections were counter-stained with contrast blue (KPL).

Stemness and invasion of UMUC-3 cells

To determine stemness23,24, 5,000 Tb-negative UMUC-3 cells transfected as described above for 24 h were suspended in MEGM (Lonza) supplemented with 25 ng/ml EGF, 5 mg/ml hydrocortisone, 5 µg/ ml insulin (Lonza) and 25 ng/ml bFGF (Invitrogen) and seeded into 2% agarose-coated 12-well-plates. After incubation at 37°C for 12 days, spheres >50 μm in diameter were scored. For matrigel invasion assay, 105 cells treated as above for 48 h were seeded over Matrigel-coated inserts (Matrigel Invasion Chamber 8.0 lm; BD Biosciences). After 24 h, inserts were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and membranes were stained with DAPI, mounted in Mowiol and observed under an Olympus CKX41 microscope at 40X magnification. At least 10 fields were evaluated10.

Statistical Analysis

Experimental results were analyzed by Student's t-test and significance (p-value) was set at the nominal level of p<0.05 or less.

Results

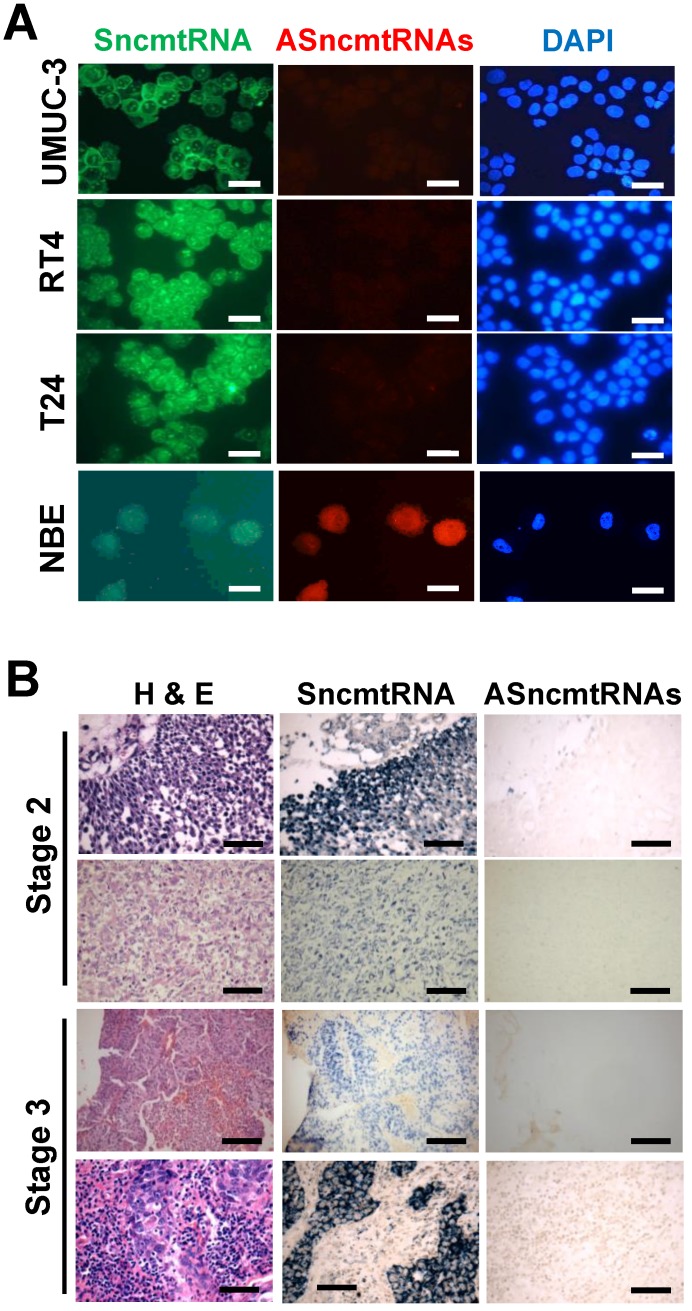

Differential expression of the SncmtRNA and ASncmtRNAs in BCa and normal bladder cells

As observed previously for other human tumor cell lines, FISH of UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 human BCa cell lines revealed expression of the SncmtRNA and downregulation of the ASncmtRNAs (Fig. 1A). In contrast, normal epithelial cells obtained from healthy bladder tissue (NBE), express both mitochondrial transcripts (Fig. 1A). Chromogenic in situ hybridization of biopsies showed that the ASncmtRNAs are also downregulated in BCa tumors, independent of the malignancy grade (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Differential expression of ncmtRNAs in bladder cancer cell lines and biopsies. (A) FISH of UMUC-3, RT-4 and T24 cells shows expression of SncmtRNA (green) and downregulation of ASncmtRNAs (red). NBE cells express both mitochondrial transcripts. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue) (Bars = 25 µm). (B) Four sections of each BCa biopsy (Grade 2 and 3) were stained with Hematoxylin/Eosin (H&E) and subjected to chromogenic ISH using specific probes for SncmtRNA and ASncmtRNAs, respectively (Bars = 100 µm).

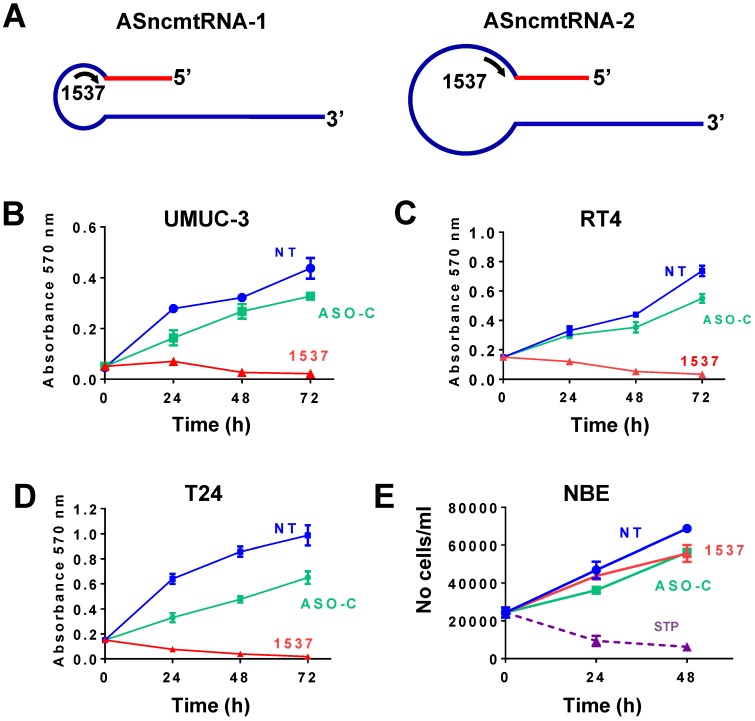

ASK induces strong inhibition of proliferation of bladder cancer cells

UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells were transfected with Andes-1537, targeted to the loop of the ASncmtRNAs (Fig. 2A). Similarly, to other human and mouse tumor cell lines12, ASncmtRNA knockdown (ASK) elicited in this manner induced a drastic inhibition of proliferation in all 3 BCa cell lines, compared to controls (Fig. 2B-D). In contrast, proliferation of normal NBE cells was not affected by the same treatment, compared to the strong reduction in viability induced by staurosporin (STP)26 (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

ASK induces strong inhibition in proliferation of BCa tumor cell lines. (A) Schematic representation of ASncmtRNA-1 and -2, indicating the complementary position of Andes-1537 (1537S). (B-D) UMUC-3 (B), RT4 (C) and T24 cells were transfected with Andes 1537 or ASO-C or left untreated for 24, 48 and 72 h and cell viability was determined at each time point by MTT assay. (E) Normal bladder epithelial (NBE) cells were transfected as described before for 24 and 48 h and cells were stained with Trypan blue. As positive control, NBE cells were incubated with 1 uM staurosporin (STP).

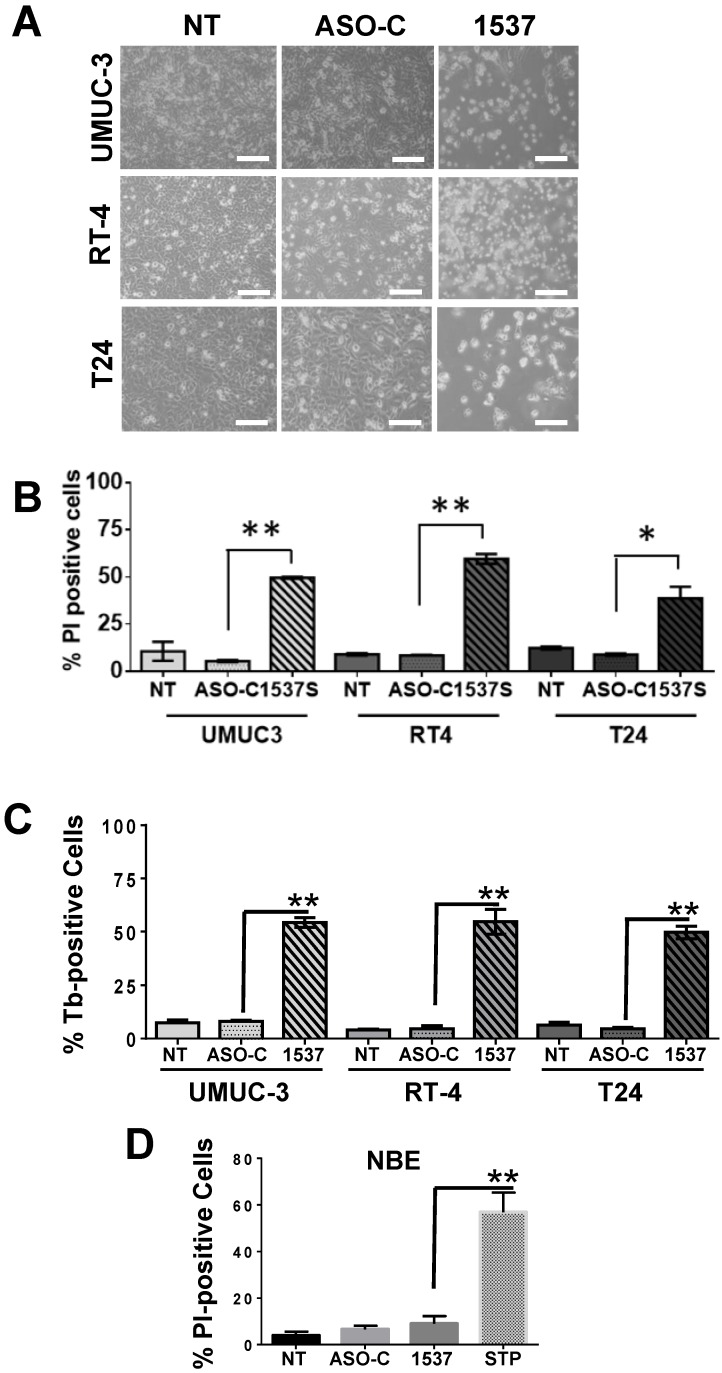

ASK induces apoptosis of bladder cancer cells

UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells transfected with Andes-1537 exhibited massive detachment from the substrate at 48 h, as compared to cells transfected with ASO-C or left untreated (NT) (Fig. 3A). This detachment and loss of cell viability (Fig. 3B-C) were the result of increased cell death, since ASK induced 50-60% Trypan blue (Tb)-positive (Fig. 3B) and PI-positive (Fig. 3C) cells. In contrast, normal bladder epithelium (NBE) cells treated with Andes-1537 did not display a higher proportion of PI-positive cells compared to controls (Fig. 3D), although, as expected, staurosporin induced around 70% PI-positive cells (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

ASK induces cell death of BCa cell lines. UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells were transfected for 48 h with Andes-1537 or ASO-C or left untreated (NT). (A) Andes-1537 caused massive cell detachment from the substrate, as opposed to controls (NT, ASO-C) (Bars = 50 μm). (B, C) Andes-1537 induced 50-60% death in all 3 cell lines, compared to controls, as evidenced by Tb (B) and PI (C) exclusion. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Andes-1537 vs. ASO-C. (D) Normal bladder epithelial cells were transfected with Andes-1537 or ASO-C or left untreated for 48 h and permeability to PI was determined by cytometry. Andes-1537 treatment displayed no significant level of cell death, like controls. Staurosporine (STP) treatment was used as positive control. **p<0.01, STP vs. Andes-1537.

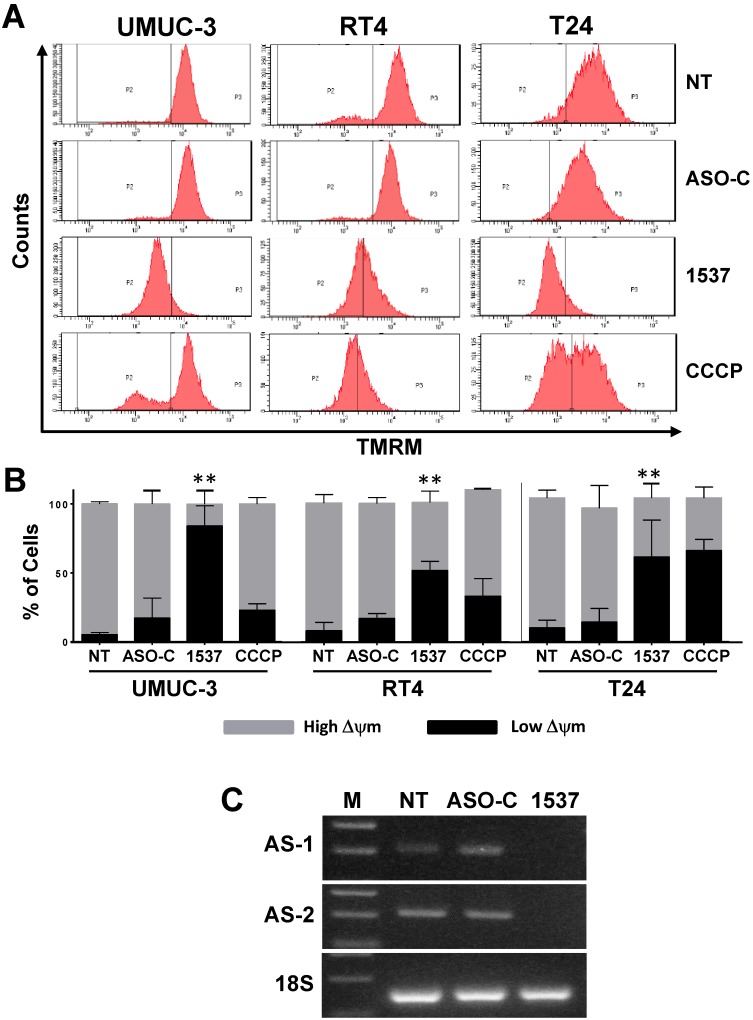

In order to determine if ASK-induced death of BCa cell lines occurs through apoptosis, as observed previously for other cancer cell types11, we measured mitochondrial membrane potential (ΨΔm)26-28 in UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cell lines treated as above for 48 h and stained with tetramethyl-rhodamine methylester (TMRM). The uncoupling drug CCCP was used as positive control26. Flow cytometry revealed that ASK induced a marked dissipation of ΨΔm in all 3 cell lines, compared to controls (Fig. 4A). Results of three independent experiments show that Andes-1537 induced 50-80% dissipation of ΨΔm (Fig. 4B). Note that CCCP induces only 40% ΨΔm dissipation. RT-PCR corroborated that ASK induced knockdown of ASncmtRNA-1 and ASncmtRNA-2 targets (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

ASK induces dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm). UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells treated with Andes-1537 or ASO-C, or left untreated (NT) for 24h or with uncoupling drug CCCP were harvested at 24 h post-transfection, stained with 20 nM TMRM for 15 min and analyzed by flow cytometry, revealing that ASK induces dissipation of Δψm. (B) A triplicate analysis shows that Andes-1537 induced between 50 and 80% dissipation of Δψm (UMUC-3, **p=0.0073; RT4, **p=0.0024; T24, p=0.017). (C) RT-PCR of total RNA purified from cells treated as in (A) for 48 h revealed the specific knockdown effect of Andes-1537 on ASncmtRNA-1 (AS-1) and ASncmtRNA-2 (AS-2). 18S rRNA was used as internal control. (M, 100-bp ladder).

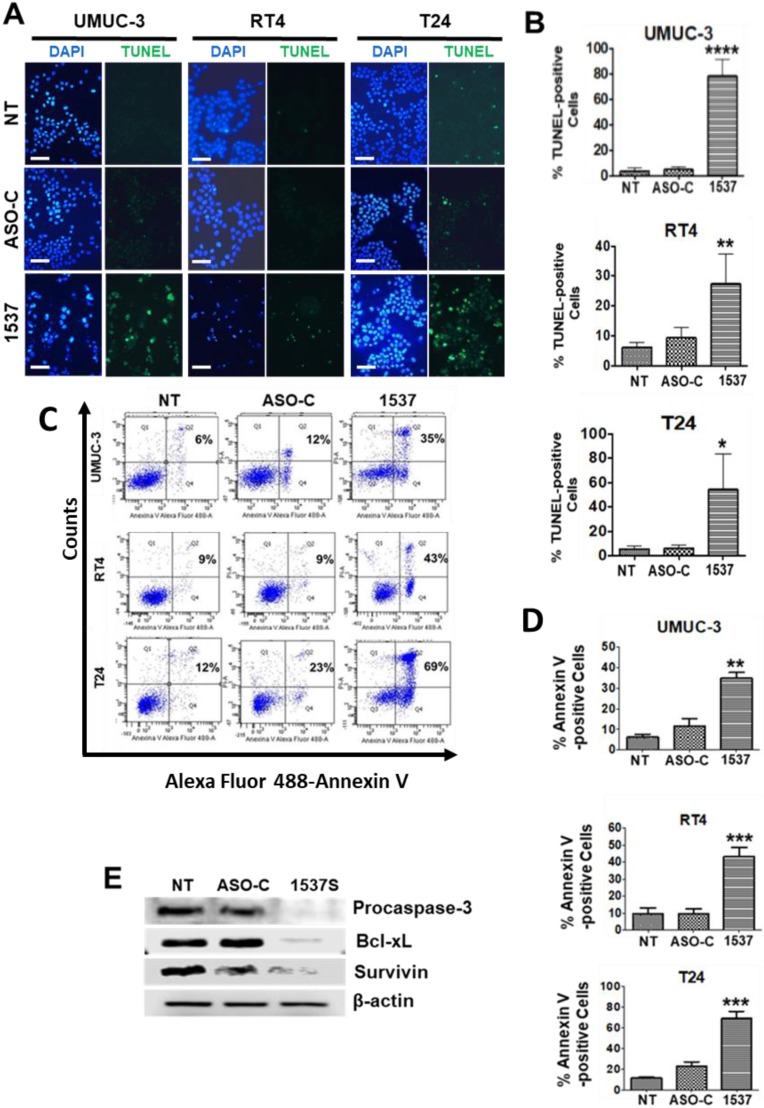

In addition, ASK for 48 h induced a strong increase in chromatin fragmentation (Fig. 5A, B), as evidenced by TUNEL assay, and translocation of phosphatidylserine to the outer layer of the plasma membrane (Fig. 5C, D), both hallmark markers of apoptosis25.

Figure 5.

ASK induces chromatin fragmentation and phosphatidylserine translocation in BCa cell lines. (A) UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells were transfected with Andes-1537 or ASO-C or left untreated (NT) for 48 h and subjected to TUNEL assay. Andes-1537 transfection induced an increase in TUNEL-positive cells. Bars = 50 µm. (B) Quantification of TUNEL positive cells in in all 3 lines. (C) BCa cell lines were analyzed by flow cytometry, revealing a higher population of Annexin V-positive cells in samples treated with Andes-1537. (D) Quantification of Annexin V-positive cells in the three cell lines, as compared to controls (NT and ASO-C). (E) Total lysates of UMUC-3 cells treated as in (A) were subjected to Western blot, revealing triggering of apoptosis through cleavage of procaspase-3 and drastic downregulation of Bcl-xL and survivin by ASK, compared to controls (NT and ASO-C). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; Andes-1537 vs. ASO-C.

ASK induces downregulation of the anti-apoptotic factors survivin and Bcl-xL

Apoptotic cell death depends on the counterbalance between pro-and anti-apoptotic factors29,30. Western blot of UMUC-3 cells transfected as described above for 48 h showed that ASK induces cleavage of procaspase-3 (Fig. 5E), in accordance with the apoptotic effects described above. ASK also induces downregulation of the anti-apoptotic factors Bcl-xL31, and survivin (Fig. 5F), a member of the inhibitor of family of inhibitors of apoptosis (IAP) proteins12.

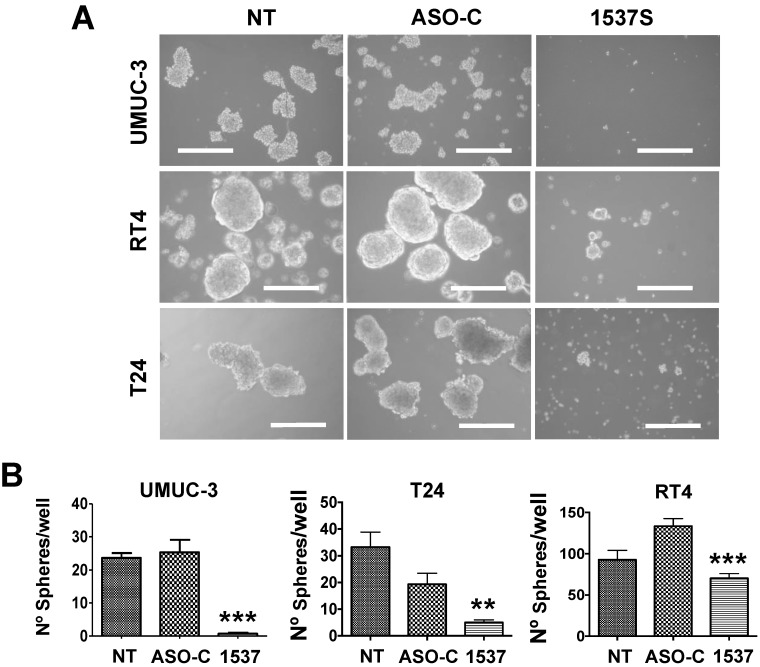

ASK reduces stemness and invasiveness of BCa cell lines

An important property of tumorigenicity is the presence of cancer stem cells (CSC), a small sub-population of tumor cells that are responsible for the initiation, progression, local and distant metastasis, resistance to chemo- and radiotherapy and disease relapse32-34. Therefore, anchorage-independent sphere formation is an important in vitro parameter to determine stemness of tumor cells. To determine whether ASK affects stemness, UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells were transfected with Andes-1537 or ASO-C or left untreated (NT) for 48 h. Cells were then harvested, counted and 5,000 Tb-negative cells were seeded per well into agarose-coated 12-well plates (see Methods). After 10 days in culture, spheres >50 µm in diameter were scored, revealing that ASK strongly inhibits sphere formation (Fig 6A, B).

Figure 6.

ASK induces inhibition of stemness in BCa cell lines. UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells (50,000 cells/well) were transfected with Andes-1537 or ASO-C or left untreated (NT) for 48 h. After harvesting, 5,000 Tb-negative cells were seeded into 12-well agarose-coated plates and cultured for 10-12 days, when spheres >50 µm in diameter were scored. (A) Representative phase contrast images of spheres (Bars = 200 µm). (B) A triplicate analysis showed that ASK induces between 50 and 90% inhibition of sphere formation in cell lines. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

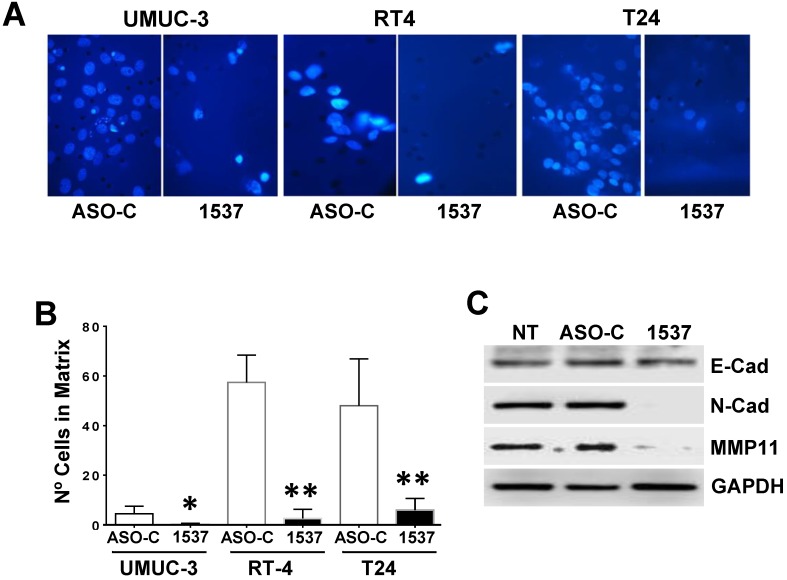

To determine whether ASK affects the invasive capacity of UMUC-3 cells8, after a 24 h treatment as described above, 150,000 Tb-negative cells were seeded over Matrigel-coated inserts. After 24 h, the membranes were fixed, mounted in Mowiol, stained with DAPI and observed by fluorescence microscopy. ASK induced a significant reduction on the invasion capacity of UMUC-3 cells (Fig. 7A, B). Western blot showed that this effect is brought about by downregulation of N-cadherin and Matrix Metallopeptidase 11 (MP11), key proteins involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)32-34.

Figure 7.

ASK reduces invasiveness of BCa cell lines. UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 cells (50,000 cells/well) were transfected with Andes-1537 or ASO-C or left untreated (NT) for 48 h. (A) Invasion was determined with Matrigel Transwell Assay. (B) A triplicate analysis showed that ASK induces a drastic and significant reduction of invasiveness in all 3 cell lines. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (C) UMUC-3 cells transfected as in (A) for 48 h were collected and total lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis of E-cadherin (E-cad), N-cadherin (N-cad) and Matrix Metallopeptidase 11 (MMP), using GAPDH as loading control. ASK induces down regulation of N-cadherin and MMP11.

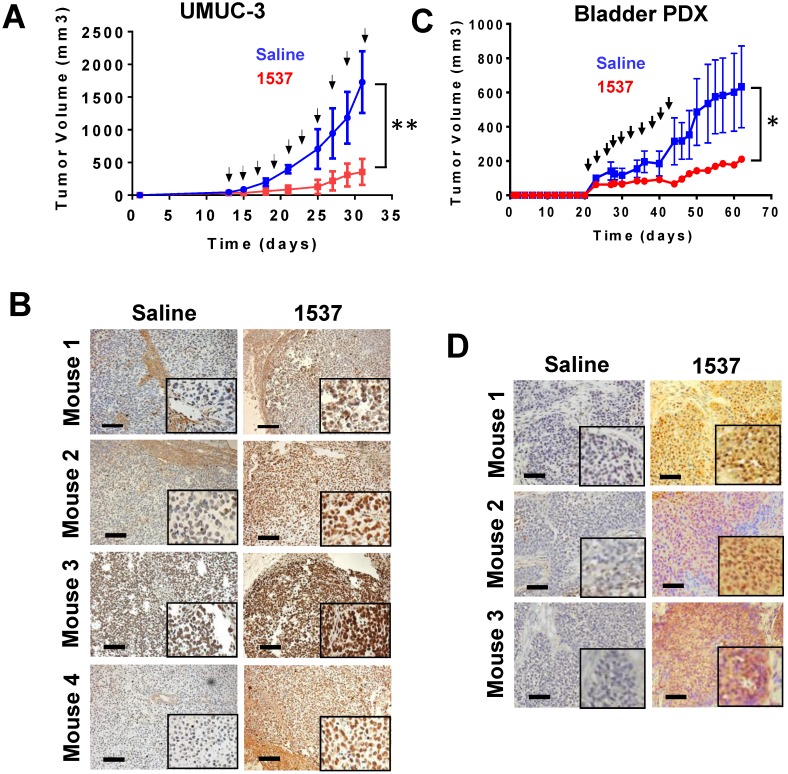

ASK inhibits growth of UMUC-3 tumors in vivo

In order to probe in vivo the effect of ASK on BCa tumor growth, we injected UMUC-3 cells (5 x 105) sc into the left flank of 10 NOD-SCID mice. When tumors reached an average volume about 80 mm3, mice were randomized into two groups of 5 mice each, with similar tumor size. Mice were injected intraperitoneally (ip) every other day, in a blinded fashion, with 10 doses of 200 µl saline either alone or containing 100 µg Andes-1537 (see arrows Fig. 8A). Tumor growth of saline-injected mice reached around 800 mm3 on day 30 post-cell injection, while tumor growth in mice treated with Andes-1537 was strongly inhibited, reaching a maximum average tumor size of 180 mm3 (Fig. 8A). On day 32 post-cell injection, all mice were sacrificed under anesthesia and tumors were collected, fixed and cut into 5 µm sections. To assess the effect of treatment on induction of apoptosis, tumor sections were analyzed by TUNEL assay. Around 70% of TUNEL-positive nuclei was observed in tumor sections from mice treated with Andes-1537, in contrast with absence of signal in saline control tumors (Fig. 8B, see inserts).

Figure 8.

ASK delays BCa tumor growth in vivo. (A) Mice bearing tumors between 50-80 mm3 were randomized into 2 groups of 5 mice each, which were treated with Andes-1537 or saline alone. At 32 days post-cell injection, ASK induced a drastic inhibition of tumor growth (**p=0.0031), mice were euthanized under anesthesia and tumors were collected from both groups. (B) ASK induces TUNEL-positive cells in tumors. Only tumors from Andes-1537-treated mice showed positive TUNEL nuclear staining (Bars = 250 µm). Inserts show higher magnification of the same samples. (C) Andes-1537S inhibits growth of a BCa PDX tumor. On day 23 post-implantation, tumors of about 100 mm3 were observed and mice were randomized into two groups. The control group was injected ip with 200 µl saline and the treatment group with 100 µg Andes-1537. The remaining 9 injections of the treatment group were performed with 50 µg Andes-1537 (arrows). ASK induced significant inhibition of tumor growth, compared to saline (*p=0.0078). (D) At day 62 post-implantation, mice were euthanized under anesthesia and tumors sections were analyzed by TUNEL assay, showing that tumors from Andes-1537-treated PDX mice displayed positive nuclear signal (Bars = 250 µm).

Evaluation of ASO therapy in a patient derived-xenograft (PDX) model of bladder cancer

To evaluate the effect of ASK in vivo in a scenario closer to real clinical specimens, we developed a PDX BCa model. The tumor sample was obtained from a male BCa patient at stage T2N0M035, displaying penetration through the muscle layer. Small pieces of the tumor sample of about 3 mm3 were implanted sc in 3 mice and after 3 weeks, tumors ~600 mm3 were collected after surgery under anesthesia (first generation PDX). This first generation of PDX was again divided in pieces of about 3 mm3 and implanted sc into 10 mice (second generation PDX). When tumors reached a size between 80 and 100 mm3, mice were randomized into two group of 5 mice each and injected ip with 200 μl saline, either alone or containing 100 μg Andes-1537. This first injection was followed by 9 injections with saline alone or containing 50 μg Andes-1537 (see arrows Fig. 8B). Treatment with Andes-1537 induced strong inhibition of tumor growth as compared to the control group (Fig. 8C). On day 62 post-tumor implantation, mice were sacrificed under anesthesia and tumors of three mice were collected, fixed and sectioned. Chromogenic TUNEL assay revealed around 60% positive nuclei in tumors from Andes-1537-treated mice, compared to no signal in the control group (Fig. 8D).

Discussion

As described previously for other cancer cell types11, the mitochondrial ASncmtRNAs, as well as SncmtRNA, are expressed in normal proliferating bladder cells, but the former is downregulated in BCa cell lines as well as in BCa biopsies15. Interestingly, we reported that the urine from patients with BCa contain cells that show expression of SncmtRNA and downregulation of ASncmtRNAs, in contrast to urine from healthy donors22. Hence, downregulation of the ASncmtRNAs seems to be an important step during carcinogenesis and represents a general hallmark of cancer11,15. Interestingly, in mouse cells the expression pattern of these mitochondrial transcripts is identical to human cells and mouse tumor cells also downregulate the ASncmtRNAs8,10. The mechanism underlying the downregulation of these transcripts during carcinogenesis is unclear, but in human papilloma-virus infected cells (HPV), it appears to be mediated by the E2 viral oncogene16. Interestingly, mouse hepatocytes transfected with a vector encoding hepatitis B virus antigen X also display downregulation of the ASncmtRNAs (E. Jeldes, unpublished results). However, the important question of which factor(s) induce(s) downregulation of these mitochondrial transcripts in non-viral induced cancers remains unknown.

As reported here, knockdown of the ASncmtRNAs (ASK) with Andes-1537 induces strong inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptotic cell death of UMUC-3, RT4 and T24 BCa cell lines, independent of their genetic backgrounds (see Methods). In UMUC-3 cells, apoptosis is mediated at the molecular level by downregulation of Bcl-xL and survivin, two important apoptotic inhibitors25,31. In other words, BCa cells cannot elude apoptotic death and, more importantly, the ASO treatments do not affect viability of normal bladder epithelial cells. Probably the lower copy number of ASncmtRNA in tumor cells renders them more vulnerable to ASK, although this hypothesis warrants further research15. Therefore, a question that remains unanswered is why tumor cells maintain low levels of ASncmtRNAs. Does downregulation of ASncmtRNAs constitute a kind of oncogenic switch? We believe that the high levels of these RNAs in normal cells could play a tumor suppressor role. This dual role of a molecule in carcinogenesis and metastasis has been described for mutated forms of p5336,37, and TGF-β during breast cancer progression38-39.

In addition to apoptotic cell death, ASK also induces strong inhibition of stemness and invasion40,41 (Fig. 6, 7). Inhibition of invasiveness correlates with downregulation of N-cadherin and MMP11, two important factors involved in EMT, invasion and metastasis43. An important question is how Andes-1537 can reduce the levels of these 2 EMT-promoting factors and 2 apoptosis inhibitors (survivin and Bcl-xL). We hypothesized that in human melanoma SK-MEL-2 cells, downregulation of similar proteins by ASK might be mediated by microRNAs (miRNAs)11, which have become increasingly important amongst epigenetic factors controlling tumorigenesis43,44. We postulated that these miRNAs are probably generated by Dicer-mediated processing of the double-stranded stem of the ASncmtRNAs as a consequence of ASK11. Recently, we found that ASK induces the expression of hsa-miR-1973 and hsa-miR-4485-3p in the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231, with sequences that match perfectly to the sequence of the stem of ASncmtRNA-2. In addition, nuclear-encoded miRNAs are also upregulated by the treatment45.

Previously we showed that ASK is an effective in vivo strategy to reduce tumor growth in murine syngeneic models of melanoma (B16F10 cells)8,9 and renal cell carcinoma (RenCa cells)10. Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumors are models developed by direct transplantation of human tumor fragments into immune-compromised mice. In BCa, recently a total of 65 human bladder cancer tissues samples were implanted sc into the flanks of immunodeficient mice, obtaining six successful PDX models, and primary tumor tissues and xenografts of passage 2 or higher were compared. The analysis showed similar histological characteristics, degree of differentiation, and genomic alterations between the primary and xenograft tumors46. Moreover, previous work reported that PDX models allowed efficacy studies of combination therapy, either concurrent or sequential, to select the most effective therapy to be used in patients47. For these reasons, PDX models are considered a valuable platform for translational cancer research and are becoming standard practice for cancer research48-50.

In vivo results in xenografts and in the PDX model, support the proof-of-concept of the potential use of ASK for BCa therapy. Indeed, a Phase I Clinical Trial (NCT02508441) with Andes-1537 in San Francisco, CA (UCSF) was recently completed. Andes-1537 was well-tolerated and one patient with pancreatic cancer and another with cholangiocarcinoma maintained stable disease beyond six months51.

Conclusions

Our study shows that knockdown of ASncmtRNAs induces a pleiotropic effect, affecting simultaneously several physiological processes such as proliferation, apoptosis evasion and invasion, required for bladder cancer progression. However, there are still some limitations in our study, for example, whether ASK is responsible for the generation of miRNAs that act negatively on several different targets. Or, can the ASncmtRNAs act as miRNA sponges or ceRNAs? Precise molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of ASK by antisense treatment and the negative effects over bladder tumor cell physiology warrants future research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the “Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica” (CONICYT), Chile [grants Fondecyt-1140345, Fondef-D04I1338 and Proyecto Basal AFB 170004]. The authors wish to thank María José Fuenzalida from the Cytometry Facility at Fundación Ciencia & Vida, for her support and expertise in flow cytometry experiments.

Abbreviations

- ASncmtRNAs

antisense non-coding mitochondrial RNAs

- ASK

ASncmtRNA knockdown

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- BCa

bladder cancer

- SncmtRNA

sense non-coding mitocondrial RNA

- PDX

patient-derived xenograft

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowles MA. Molecular pathogenesis of bladder cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:287–97. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vishnu P, Mathew J. Tan WW. Current therapeutic strategies for invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2011;4:97–113. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S22875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rink M, Ehdaie B, Cha EK. et al. Stage-specific impact of tumor location on oncologic outcomes in patients with upper and lower tract urothelial carcinoma following radical surgery. Eur Urol. 2012;62:677–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan AL, Litwin MS, Chamie K. The future of bladder cancer care in the USA. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:59–62. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noon AP, Albertsen PC, Thomas F. et al. Competing mortality in patients diagnosed with bladder cancer: evidence of undertreatment in the elderly and female patients. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1534–40. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noon AP, Catto JW. Bladder cancer in 2012: Challenging current paradigms. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:67–68. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobos-González L, Silva V, Araya M. et al. Targeting antisense mitochondrial ncRNAs inhibits murine melanoma tumor growth and metastasis through reduction in survival and invasion factors. Oncotarget. 2016;7:58331–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varas-Godoy M, Lladser A, Farfan N. et al. In vivo knockdown of antisense non-coding mitochondrial RNAs by a lentiviral-encoded shRNA inhibits melanoma tumor growth and lung colonization. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31:64–72. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borgna V, Villegas J, Burzio VA. et al. Mitochondrial ASncmtRNA-1 and ASncmtRNA-2 as potent targets to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis in the RenCa murine renal adenocarcinoma model. Oncotarget. 2017;8:43692–708. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vidaurre S, Fitzpatrick C, Burzio VA. et al. Down-regulation of the Antisense Mitochondrial ncRNAs is a Unique Vulnerability of Cancer Cells and a Potential Target for Cancer Therapy. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:27182–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altieri DC. Survivin - The inconvenient IAP. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;39:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang BH, Xia F, Pop R. et al. Developmental control of apoptosis by the immunophilin arylhy drocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP) Involves mitochondrial import of the surviving protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16758–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villegas J, Burzio VA, Villota C. et al. Expression of a novel non-coding mitochondrial RNA in human proliferating cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7336–47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burzio VA, Villota C, Villegas J. et al. Expression of a family of noncoding mitochondrial RNAs distinguishes normal from cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9430–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903086106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villota C, Campos A, Vidaurre S, Expression of mitochondrial ncRNAs is modulated by high-risk HPV oncogenes. J Biol Chem; 2012. p. 287. 21303-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landerer E, Villegas J, Burzio VA. et al. Nuclear localization of the mitochondrial ncRNAs in normal and cancer cells. Cell Oncol. (Dordr) 2011;34:297–305. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hannahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Araki K, Shimura T, Suzuki H. et al. E/N-cadherin switch mediates cancer progression via TGF-β-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1885–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Chen B, Cai J. et al. Comparative analysis of matrix metalloproteinase family members reveals that MMP9 predicts survival and response to temozolomide in patients with primary glioblastoma. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García L, Arranz I, López A. et al. New human primary epithelial cell culture model to study conjunctival inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7143–52. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivas A, Burzio V, Landerer E. et al. Determination of the differential expression of mitochondrial long non-coding RNAs as a noninvasive diagnosis of bladder cancer. BMC Urol. 2012;12:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-12-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM. et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M. et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5821–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Kepp O. et al. Mitochondrial gateways to cancer. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heiskanen KM, Bhat MB, Wang HW. et al. Mitochondrial depolarization accompanies cytochrome c release during apoptosis in PC6 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5654–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herdt BG, Houston MA, Augenlicht LH. Growth properties of colonic tumor cells area function of the intrinsic mitochondrial membrane potential. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1591–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houston MA, Augenlicht LH, Heerdt BG. Stable differences in intrinsic mitochondrial membrane potential of tumor cell subpopulations reflect phenotypic heterogeneity. Int J Cell Biol; 2011. p. 978583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez J, Meier P. To fight or die-inhibitor of apoptosis proteins at the crossroad innate immunity and death. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:872–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mace PD, Shirley S, Day CL. Assembling the building blocks: structure and function of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:46–53. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshimine S. Prognostic significance of Bcl-xL expression and efficacy of Bcl-xL targeting therapy in urothelial carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2312–20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papaccio F, Paino F Regad T. et al. Concise review: Cancer cells, cancer stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells: influence in cancer development. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:2115–25. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balsara ZR, Li X. Sleeping beauty: awakening urothelium from its slumber. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;312:F732–43. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00337.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nieto MA, Huang RY, Jackson RA. et al. EMT: 2016. Cell. 2016;66:21–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL. et al. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part B: Prostate and bladder tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:106–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bossi G, Lapi E, Strano S. et al. Mutant p53 gain of function: reduction of tumor malignancy of human cancer cell lines through abrogation of mutant p53 expression. Oncogene. 2006;25:304–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim LY, Vidnovic N, Ellisen LW. et al. Mutant p53 mediates survival of breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1606–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang B, Vu M, Booker T. et al. TGF-β switches from tumor suppressor to prometastatic factor in a model of breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1116–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI18899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jakowlew SB. Transforming growth factor-beta in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;3:435–57. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye X, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity: A central regulator of cancer progression. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:675–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gravdal K, Halvorsen OJ, Haukaas SA. et al. A switch from E-cadherin to N-cadherin expression indicates epithelial to mesenchymal transition and is of strong and independent importance for the progress of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;1:7003–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang J, Lyu H, Wang J. et al. MicroRNA regulation and therapeutic targeting of survivin in cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2014;15:20–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nana-Sinkam SP, Croce CM. MicroRNA regulation of tumorigenesis, cancer progression and interpatient heterogeneity: towards clinical use. Genome Biol. 2014;15:445. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0445-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzpatrick C, Bendek MF, Briones M. et al. Mitochondrial ncRNA targeting induces cell cycle arrest and tumor growth inhibition of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through reduction of key cell cycle progression factors. Cell Death & Dis. 2019;10:423–34. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1649-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park B, Jeong BC, Choi YL. et al. Development and characterization of a bladder cancer xenograft model using patient-derived tumor tissue. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:631–38. doi: 10.1111/cas.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan CX, Zhang H, Tepper CG. et al. Development and characterization of bladder cancer patient-derived xenografts for molecularly guided targeted therapy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0134346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sausville EA, Burger AM. Contributions of human tumor xenografts to anticancer drug development. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3351–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho SY, Kang W, Han JY. et al. An integrative approach to precision cancer medicine using patient-derived xenografts. Mol Cells. 2016;39:77–86. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okada S, Vaeteewoottacharn K, Kariya R. Establishment of a patient-derived tumor xenograft model and application for precision cancer medicine. Chem Pharm Bull. 2018;66:225–30. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c17-00789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhawan MS, Aggarwal RR, Boyd E. et al. Phase 1 study of ANDES-1537: A novel antisense oligonucleotide against non-coding mitochondrial DNA in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:suppl. abstr 2557. [Google Scholar]