Abstract

Study Objectives:

Sleep apnea (SA) is prevalent among patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and increases cardiovascular risk. A previous study showed that 1 month of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) reduced severity of SA in patients with CAD by reducing fluid accumulation in the legs during the day and the amount of fluid shifting rostrally into the neck overnight. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether CR will lead to longer-term attenuation of SA in patients with CAD.

Methods:

Fifteen patients with CAD and SA who had participated in a 1-month randomized trial of the effects of exercise training on SA were followed up until they completed 6 months of CR (age: 65 ± 10 years; body mass index: 27.0 ± 3.9 kg/m2; apnea-hypopnea index [AHI]: 39.0 ± 16.7). The AHI was evaluated at baseline by polysomnography and then at 6 months by portable monitoring at home. Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2peak) was evaluated via a graded cardiopulmonary exercise test at baseline and 6 months later. The 6-month CR program included once weekly, 90-minute, in-facility exercise sessions, and 4 days per week at-home exercise sessions.

Results:

After 6 months of CR, there was a 54% reduction in the AHI (30.5 ± 15.2 to 14.1 ± 7.5, P < .001). Body mass index remained unchanged, but VO2peak increased by 27% (20.0 ± 6.1 to 26.0 ± 8.9 mL/kg/min, P = .04).

Conclusions:

Participation in CR is associated with a significant long-term decrease in the severity of SA. This finding suggests that attenuation of SA by exercise could be a mechanism underlying reduced mortality following participation in CR in patients with CAD and SA.

Clinical Trial Registration:

This study is registered at www.controlled-trials.com with identifier number ISRCTN50108373.

Citation:

Mendelson M, Inami T, Lyons O, Alshaer H, Marzolini S, Oh P, Bradley TD. Long-term effects of cardiac rehabilitation on sleep apnea severity in patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(1):65–71.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, exercise, fluid shifts, sleep apnea, upper airway

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Sleep apnea is prevalent among patients with coronary artery disease and increases cardiovascular risk. Cardiac rehabilitation, including exercise, can lead to longer-term attenuation of sleep apnea in patients with coronary artery disease.

Study Impact: After 6 months of cardiac rehabilitation, the severity of sleep apnea decreased more than 50%. The attenuation of sleep apnea by exercise could be a mechanism whereby cardiac rehabilitation reduces mortality in patients with coronary artery disease and sleep apnea.

INTRODUCTION

Among patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), those who participate in a cardiac rehabilitation (CR) exercise program have a significantly lower mortality rate than those who do not.1 The mechanisms underlying such exercise-induced improvements in mortality have yet to be elucidated but likely involve beneficial effects on endothelial and platelet function, and on inflammatory markers.1,2 In patients with CAD, untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.3 Untreated OSA is also associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in the general population.4 In a recent randomized trial, we demonstrated that exercise training reduced the severity of OSA and central sleep apnea (CSA), assessed by the frequency of apneas and hypopnea per hour of sleep (apnea-hypopnea index, AHI) by 34% in patients with CAD over 1 month.5 Thus, an additional beneficial effect of exercise in patients with CAD may be attenuation of sleep apnea. However, if this was the case, then one would expect that exercise would also have a longer-term beneficial effect on sleep apnea severity.

The aim of this study, therefore, was to evaluate whether CR leads to longer-term attenuation of SA in patients with CAD. We hypothesized that the CR-associated reduction in sleep apnea severity observed after 1 month would be sustained or decline further over a longer 6-month period.

METHODS

Participants

Participants for this protocol had previously participated in a 4-week randomized controlled trial5 conducted at Toronto Rehabilitation Institute’s Cardiac Rehabilitation Program. Inclusion criteria were men and women aged 18 to 85 years with CAD, defined as a documented myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery or coronary angioplasty and/or stenting referred to the University Health Network Toronto Rehabilitation Institute for CR, with sleep apnea defined as an AHI of at least 15 events/h, identified on a baseline in-laboratory overnight polysomnography (PSG) as previously described.5 Exclusion criteria were treated OSA or CSA, adenotonsillar hypertrophy, use of diuretics, a history of heart failure, and inability to exercise due to musculoskeletal problems.

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

Participants underwent baseline, symptom-limited, graded exercise tests on a cycle ergometer (Ergoline 800 P) or a treadmill (Quinton) at the discretion of the cardiology technologist and physician depending on balance, mobility, and participant preference. For the cycle-ergometer protocol, the workload was increased by 16.7 W every minute and breath-by-breath gas samples were collected and averaged over 20-second periods via calibrated metabolic cart (VMAX Encore and Spectra – CareFusion, Yorba Linda, California, USA). The Bruce protocol was used for patients being tested on the treadmill.6 Peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) and the anaerobic threshold were determined, the latter by the V-slope method.7 A 12-lead electrocardiogram (Quinton, Q-Stress system) was monitored continuously.

Sleep studies

All participants underwent a baseline overnight PSG using standard techniques and scoring criteria for sleep stages, arousals from sleep, and periodic leg movements.8,9 Apneas were defined as ≥ 90% reduction in airflow or thoracoabdominal motion from baseline, respectively, lasting ≥ 10s. Hypopneas were defined as ≥ 30% reduction airflow lasting ≥ 10 seconds, associated with a ≥ 3% desaturation or an arousal from sleep.9 They were classified as obstructive if there was out-of-phase thoracoabdominal motion or flow limitation on the nasal pressure tracing, and central if there was absent thoracoabdominal motion, or in-phase thoracoabdominal motion without evidence of airflow limitation, during apneas and hypopneas, respectively.8 Sleep apnea was defined as an AHI ≥ 15 events/h and was classified as OSA when ≥ 50% of events were obstructive and as CSA when > 50% of events were central. The AHI and periodic leg movements indices were calculated. Signals were recorded on a computerized sleep recording system (Sandman, Nellcor Puritan Bennett Ltd., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and scored by technicians blinded to the other experimental data and to the randomization.

Six months after entering the CR program, the AHI was determined in the patients’ homes by a validated portable home sleep apnea diagnostic device, BresoDX (BresoTEC Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada).10–12 Data recorded using BresoDX were downloaded and analyzed by a computerized algorithm that automatically detects apnea and hypopneas as previously described.10 Sleep time was estimated using head actigraphy embedded in the BresoDX face-frame.13 The AHI was calculated as the number of apnea and hypopneas divided by estimated sleep time.

Cardiac rehabilitation

Patients participated in a 6-month CR program, which included once weekly, 90-minute, supervised on-site exercise sessions, and at-home sessions 4 days per week. A combination of aerobic exercise (30 to 60 minutes, 5 days per week) and resistance training (two to three sessions per week) was used. Training modality was individually prescribed according to the participants’ abilities: either overground walking, treadmill walking, or cycle ergometer for the aerobic training, and either dumbbells, resistance bands, or working against body weight for resistance training. The same exercises were performed during on-site and at-home sessions where one aerobic and one resistance training session per week were performed on site and the remaining (four aerobic and one to two resistance) training sessions were performed independently at home. Intensity of on-site exercise was monitored using 10-second pulse rate or heart rate monitors, and ratings of perceived exertion. CR also included regular education seminars emphasizing issues related to cardiac symptom recognition, managing modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, unhealthy diet, and physical activity levels and medication use.

Protocol

Patients who had previously participated in a 4-week-long randomized controlled trial of CR5 were approached to participate in the current study. In the previous study, prior to entering CR, participants underwent a baseline cardiopulmonary exercise test. Participants then underwent a baseline PSG. Individuals with an AHI ≥ 15 events/h on PSG were then randomly allocated to an exercise intervention or control group. Participants in the control group were instructed to maintain their usual level of activity for 4 weeks. None of the participants was treated for their sleep apnea during the study period. After 4 weeks, all assessments made at baseline were repeated. At this point, participants in the control group crossed over into CR. Participants who had been randomized to exercise continued in CR. Patients’ baseline AHI data were taken from the previous protocol. For patients who had been randomized to the 4-week exercise group, baseline AHI was taken from their first PSG. For patients who had been randomized to the 4-week control group, their baseline AHI for the current study was taken from the PSG performed at the end of the 4-week control period because it was the AHI just prior to undergoing CR. In the previous study, we showed that there was no change in the AHI in the control group between baseline and 4 weeks later. After completion of 6 months of CR, patients had their AHI reevaluated at home via the portable home sleep apnea diagnostic device only and completed a follow-up cardiopulmonary exercise test. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Data analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as proportions. Changes from baseline to follow-up were analyzed using paired t tests. A value of P < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

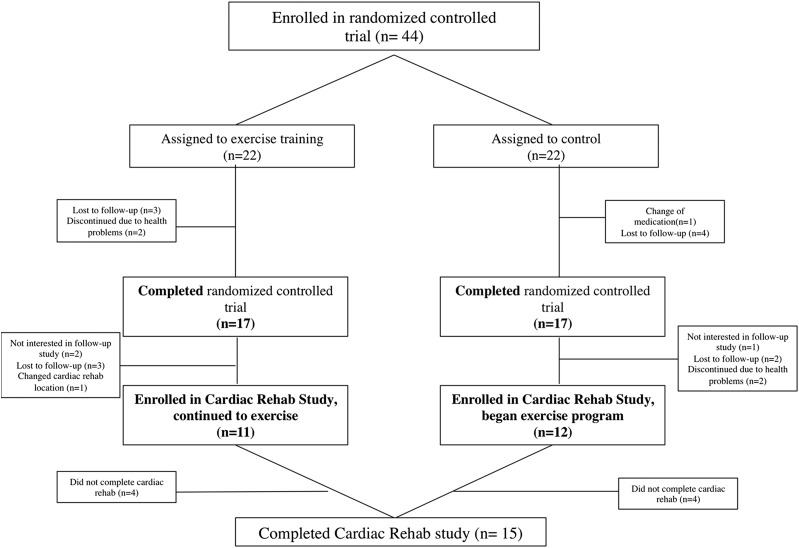

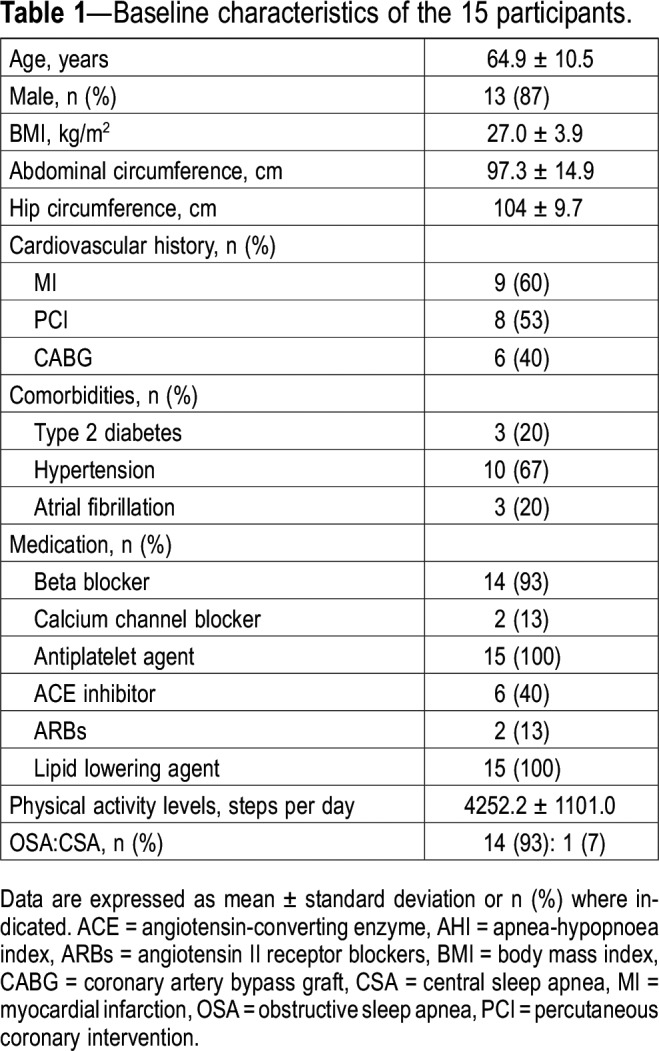

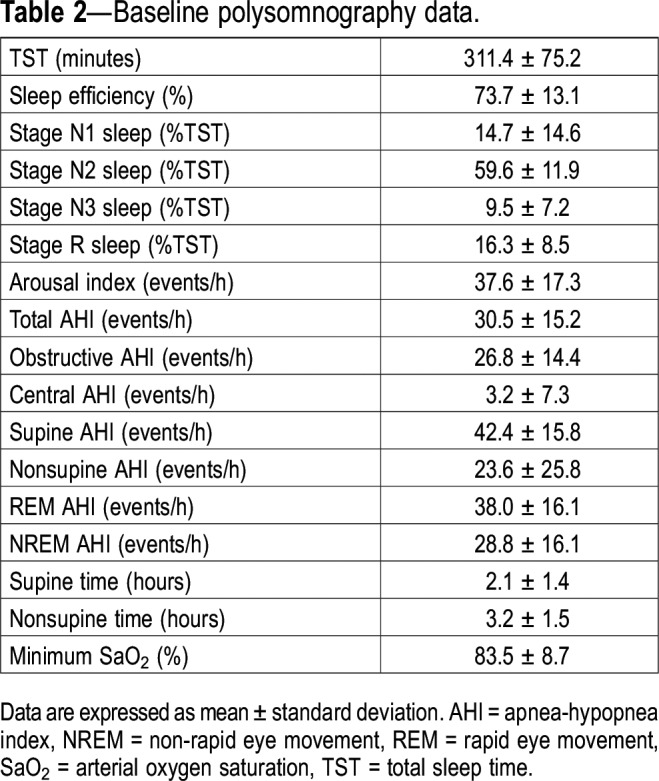

Study participants flow through the protocol is shown in Figure 1. Of the 34 patients who had completed the previous randomized controlled trial,5 23 accepted to participate in this ancillary study. Of those, 15 completed the study and their baseline clinical characteristics and polysomnographic data are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Most of the patients were mildly overweight men. Most patients had OSA (93%) with a mean AHI in the severe range (30.5 ± 15.2).

Figure 1. Flow of the participants through the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 15 participants.

Table 2.

Baseline polysomnography data.

Effects of 6 months of CR

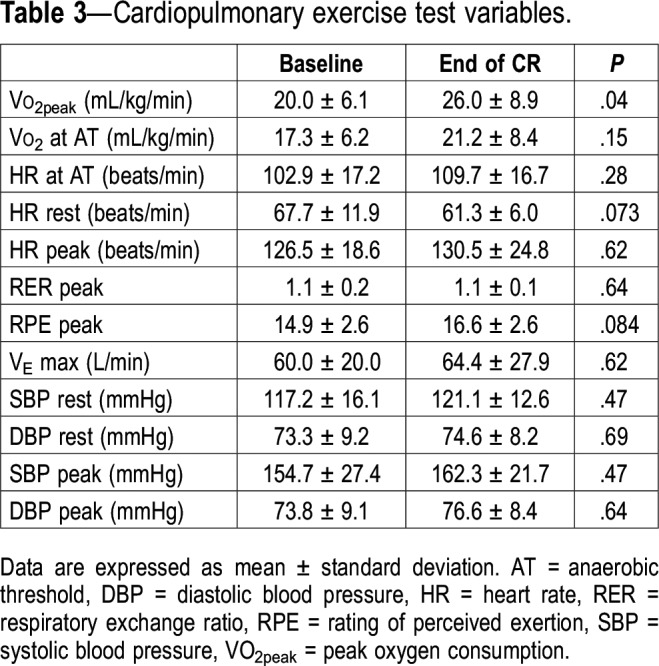

There was no change in body weight (from 83.5 ± 14.4 to 83.4 ± 14.2 kg, P = .99) after 6 months of CR. Changes in cardiopulmonary exercise test variables are presented in Table 3. Only VO2peak increased significantly (P = .04).

Table 3.

Cardiopulmonary exercise test variables.

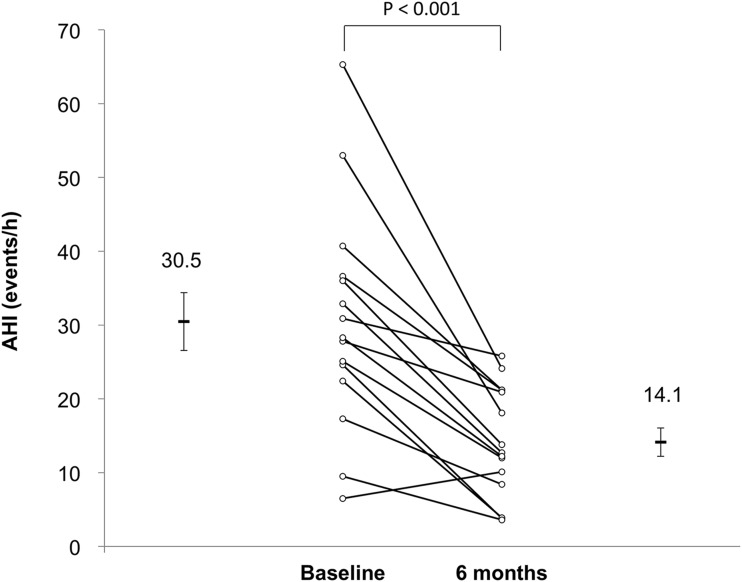

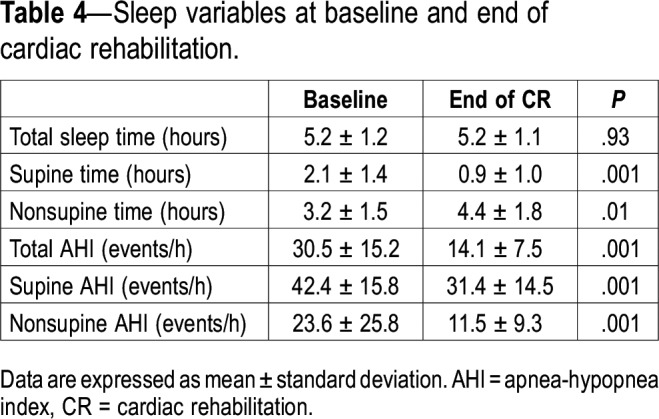

After 6 months of CR, there was a 54% reduction in the AHI (P < .001, Figure 2). Table 4 displays sleep data at baseline and 6 months. There was no change in the total sleep time from baseline to 6 months (from 5.2 ± 1.2 to 5.2 ± 1.1 hours, P = .93). However, time spent in the supine position decreased significantly from baseline to 6 months (from 2.1 ± 1.4 to 0.9 ± 1.0 hours, P = .001). Nevertheless, this was not the main factor contributing to the reduction in AHI, because there were reductions in both the supine AHI (from 42.4 ± 15.8 to 31.4 ± 14.5, P = .001) and nonsupine AHI (from 23.6 ± 25.8 to 11.5 ± 9.3, P = 0.001). Furthermore, we did not find any relationship between the reduction of AHI at 6 months and either the improvement in VO2peak (R2 = .046, P > .05) or the degree of reduction in overnight rostral fluid shift after 1 month of CR in the original treatment group (R2 = .039, P > .05). There was no difference in the change in the AHI in patients who crossed over from control group to CR group after the 1-month randomized trial compared to those who were in the original exercise group (a 55.3% reduction in AHI from 36.6 to 16.3 versus a 51.5% reduction from 25.1 to 12.2 in the control and exercise groups, respectively).

Figure 2. AHI at baseline and after 6 months of cardiac rehabilitation.

The AHI decreased from 30.5 ± 15.2 to 14.1 ± 7.5 events/h (P < .001) from baseline to 6 months later at the end of cardiac rehabilitation. AHI = apnea-hypopnea index.

Table 4.

Sleep variables at baseline and end of cardiac rehabilitation.

DISCUSSION

The most important result of the current study is that in patients with CAD and SA, participation in 6 months of exercise CR was accompanied by a significant decrease in the severity of SA. The 54% reduction in the AHI was in the clinically significant range in many and occurred despite a lack of change in body weight.

Previous studies have demonstrated that exercise training reduces sleep apnea severity. For example, a recent meta-analysis concluded that among randomized controlled trials, exercise training was associated with a reduction of 28% in AHI from baseline.14 Furthermore, in the randomized trial conducted prior to the current ancillary study,5 we showed that 4 weeks of exercise training alone reduced the AHI by 34% in patients with CAD via a reduction in leg fluid volume and attenuation of the overnight rostral fluid shift from the legs to the neck. The exercise protocols used in most studies to date have been 3 months or less, whereas ours was 6 months. It is possible that there is a progressive effect over time that could account for the greater reduction in the AHI after 6 months in the current study than we observed after 1 month in our previous study.5 Such a long-term effect might also explain why the 54% reduction we observed after 6 months of CR was greater than that reported in other studies of CR of less than 6 months’ duration.15–17 The AHI can be subject to night-to-night variability.18 However, in the current study, the magnitude of reduction in the AHI in both the original control and treatment groups is much greater than could be attributed to night-to-night variability.

There are several physiological mechanisms that might explain how exercise training alleviates OSA. In our previous 4-week randomized trial in patients with CAD and sleep apnea, we observed that the reduction in the AHI was accompanied by reductions in the fluid volume of the legs and in the degree of overnight fluid shift from the legs to the neck. This was, in turn, associated with dilatation of the upper airway, presumably due to a reduction in tissue pressure around the upper airway because of reduced fluid accumulation. These data strongly suggest that reduced overnight fluid shift into the neck and upper airway dilation were mechanisms involved in the reduction in AHI in the absence of any change in body weight or physical fitness (VO2peak). It is likely that the same mechanisms contributed to the reduction in AHI we observed after 6 months in the current study. However, data on fluid shift and upper airway dimensions were not available at the 6-month point in the current study. It is also not clear why the AHI fell further from 4 weeks to 6 months. One possibility is that there was a progressive reduction in leg fluid volumes and overnight rostral fluid shift as patients continued their exercise program between 4 weeks and 6 months.

Other potential physiological mechanisms that may explain the effect of exercise training on sleep apnea include increased respiratory stability through more consolidated and deeper sleep, increased strength and fatigue resistance of the upper airway dilators, and decreased nasal resistance.16 Aerobic exercise can also improve cardiometabolic and chemoreflex control responses, which may improve upper airway function. However, we have no direct data to support these potential mechanisms. Furthermore, although we did not document an objective measurement of exercise compliance, the significant improvement in VO2peak indicates that the patients were compliant enough to improve their physical fitness. Furthermore, it has previously been shown that mean compliance rates in the CR program used in the current study are approximately 80% of prescribed exercise sessions.19

We observed improved cardiorespiratory fitness in patients after 6 months of cardiac rehabilitation, which is consistent with previous studies in patients with OSA.15,16,20 However, none of those previous studies showed that reductions in the AHI were related to improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, nor did they propose any physiologically plausible explanation as to why improved fitness might contribute to the reduced AHI. Consequently, we do not think that the improvement in VO2peak contributed to the observed decrease in the AHI, particularly because the AHI improved after 4 weeks in the absence of any improvement in fitness.5

In the current study, supine time during sleep decreased significantly from baseline to 6 months. This may have contributed in part to the improvement in AHI after cardiac rehabilitation. However, because both the supine and nonsupine AHIs decreased from baseline to 6 months, it is highly unlikely that the change in the time spent supine was the main factor responsible for improvement in the AHI.

It is also possible that the multidisciplinary approach of CR that includes not only exercise, but also dietary management and risk-factor modification, contributed to attenuation of sleep apnea. However, this seems unlikely in view of two observations: first, the fall in AHI from baseline to 4 weeks in the initial study occurred prior to the institution of dietary management and risk factor modification, and second, the fall in AHI at both 4 weeks and 6 months occurred in the absence of weight loss.

Participation in 6 months of CR was associated with a 54% decrease in the AHI. In 10 of 15 patients, the decrease in AHI was greater than 50% and in 9 of 15 patients, the AHI decreased to less than 15 events/h. Thus, the magnitude of the fall in AHI is likely to have been clinically significant in most patients. These data highlight the importance and benefits of CR for the management of sleep apnea in these patients.

The current study also sheds light on a potential mechanism by which exercise improves morbidity and mortality in patients with CAD. Untreated OSA in patients with CAD is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.3 Our data suggest the possibility that attenuation of sleep apnea, which is common in patients with CAD,21 could contribute to the reduction in mortality. However, larger-scale randomized trials would be required to assess this possibility.

The current study has some limitations. First, it was not a randomized trial and did not include a control group who did not participate in CR. However, in the previous 4-week randomized trial, that included the same patients, we demonstrated a significant fall in the AHI in the CR group, but not in the control group.5 In addition, the patients who crossed over from control group to CR group after the four-week randomized trial period experienced a fall in AHI after six months similar to that seen in those originally randomized to CR. Consequently, it appears most likely that the fall in the AHI observed after 6 months of CR was due to exercise. Second, we did not measure fluid shift and upper airway dimensions at the 6-month point in the current study, and therefore cannot be certain that attenuation of rostral fluid shift and upper airway dilation were responsible for the fall in AHI. However, in view of our findings after the 4-week randomized trial period,5 it seems likely that these factors contributed to the fall in AHI after 6 months as well. Third, whereas the AHI was determined by the in-laboratory PSG at baseline, the follow-up AHI at 6 months was determined from the portable apnea monitoring device at home. However, we have previously shown the AHI determined by BresoDX to be in excellent agreement with that determined at simultaneous PSG.22 Accordingly, we are confident of the accuracy of the AHI results at 6 months. The BresoDX device is unable to differentiate between central and obstructive events at this time. Therefore, we cannot draw conclusions as to effects of exercise on central versus obstructive events. However, this is largely irrelevant because 14 of the 15 patients had OSA and because most events at baseline were obstructive (88%), it can be assumed that the reduction in total AHI observed is predominantly the result of a reduction in obstructive events. Accordingly, this study is essentially examining the effects of exercise on OSA. Last, we cannot exclude a potential selection bias toward including those who adhered better to the exercise protocol because not all patients included in the previous randomized trial completed the 6-month follow-up.

In conclusion, this study found that participation of patients with CAD and coexisting sleep apnea in CR is associated with a clinically significant long-term decrease in sleep apnea severity. Our results also suggest a progressive reduction in sleep apnea severity from baseline to 4 weeks to 6 months during CR. One implication of our results is that attenuation of sleep apnea by exercise could be a mechanism underlying reduced mortality following participation in CR in patients with CAD and SA. Future larger scale, long-term trials will be required to address this possibility.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) operating grant MOP-82731. Dr. Lyons was supported by a joint Canadian Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Peter Macklem Research Fellowship and the Joseph M. West Family Memorial Fund Postgraduate Research Award. Dr. Inami was supported by an unrestricted fellowship from Philips Respironics Japan. Dr. Bradley is supported by the Clifford Nordal Chair in Sleep Apnea and Rehabilitation Research, and the Godfrey S. Pettit Chair in Respiratory Medicine. Dr. Bradley is the chief Medical Officer or BresoTEC Inc., whose device, BresoDX, was used in this study. Dr. Alshaer is the co-inventor of the sleep apnea and snoring detecting device (BresoDX) used in the study and is an officer in the manufacturing company.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CSA

central sleep apnea

- CR

cardiac rehabilitation

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- VO2peak

peak oxygen consumption

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter DA, Oh PI, Chong A. Relationship between cardiac rehabilitation and survival after acute cardiac hospitalization within a universal health care system. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(1):102–113. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328325d662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mora S, Cook N, Buring JE, Ridker PM, Lee IM. Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events: potential mediating mechanisms. Circulation. 2007;116(19):2110–2118. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peker Y, Hedner J, Kraiczi H, Loth S. Respiratory disturbance index: an independent predictor of mortality in coronary artery disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(1):81–86. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9905035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendelson M, Lyons OD, Yadollahi A, Inami T, Oh P, Bradley TD. Effects of exercise training on sleep apnoea in patients with coronary artery disease: a randomised trial. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):142–150. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01897-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce RA, Kusumi F, Hosmer D. Maximal oxygen intake and nomographic assessment of functional aerobic impairment in cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 1973;85(4):546–562. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(73)90502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60(6):2020–2027. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):597–619. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rechtschaffen A, Kales AA. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Washington, DC: Public Health Service, U.S. Government Printing Office; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alshaer H, Fernie GR, Maki E, Bradley TD. Validation of an automated algorithm for detecting apneas and hypopneas by acoustic analysis of breath sounds. Sleep Med. 2013;14(6):562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alshaer H, Levchenko A, Bradley TD, Pong S, Tseng WH, Fernie GR. A system for portable sleep apnea diagnosis using an embedded data capturing module. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27(3):303–311. doi: 10.1007/s10877-013-9435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alshaer H, Rudzicz F, Falk TH, Tseng WH, Bradley TD. Classification of vibratory patterns of the upper airway during sleep. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2013;2013:2080–2083. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2013.6609942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hummel R, Bradley TD, Fernie GR, Chang SJ, Alshaer H. Estimation of sleep status in sleep apnea patients using a novel head actigraphy technique. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015;2015:5416–5419. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7319616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendelson M, Bailly S, Marillier M, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, objectively measured physical activity and exercise training interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2018;9:73. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desplan M, Mercier J, Sabaté M, Ninot G, Prefaut C, Dauvilliers Y. A comprehensive rehabilitation program improves disease severity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a pilot randomized controlled study. Sleep Med. 2014;15(8):906–912. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kline CE, Crowley EP, Ewing GB, et al. The effect of exercise training on obstructive sleep apnea and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2011;34(12):1631–1640. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sengul YS, Ozalevli S, Oztura I, Itil O, Baklan B. The effect of exercise on obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized and controlled trial. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(1):49–56. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levendowski DJ, Zack N, Rao S, et al. Assessment of the test-retest reliability of laboratory polysomnography. Sleep Breath. 2009;13(2):163–167. doi: 10.1007/s11325-008-0214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanmugasegaram S, Oh P, Reid RD, McCumber T, Grace SL. A comparison of barriers to use of home- versus site-based cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2013;33(5):297–302. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31829b6e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Servantes DM, Pelcerman A, Salvetti XM, et al. Effects of home-based exercise training for patients with chronic heart failure and sleep apnoea: a randomized comparison of two different programmes. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(1):45–57. doi: 10.1177/0269215511403941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa LE, Uchoa CH, Harmon RR, Bortolotto LA, Lorenzi-Filho G, Drager LF. Potential underdiagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea in the cardiology outpatient setting. Heart. 2015;101(16):1288–1292. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alshaer H, Fernie GR, Tseng WH, Bradley TD. Comparison of in-laboratory and home diagnosis of sleep apnea using a cordless portable acoustic device. Sleep Med. 2016;22:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]