Abstract

Study Objectives:

Executive functions (EFs) in children with insomnia have not been sufficiently assessed in the literature. This study aimed to describe sleep patterns and habits and EF abilities in preschool children with insomnia, compared to healthy control patients, and to evaluate the relationships between sleep patterns and EFs.

Methods:

Two groups of children were recruited: 45 preschoolers with chronic insomnia (28 boys), aged 24–71 months and 167 healthy preschool children (81 boys) aged 24–71 months. Parents of all children completed two questionnaires to assess their children’s sleep habits and disturbances, and their EFs with the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – Preschool Version.

Results:

Children with chronic insomnia were found to wake up earlier, sleep less during the night, have more nighttime awakenings, and higher nocturnal wakefulness, compared to the control group. The chronic insomnia group showed significant impairment in all the EFs domains. Nocturnal sleep duration, nighttime awakenings, and nocturnal wakefulness correlated with inhibit, plan/organize, working memory, inhibitory self-control, emergent metacognition, and the global executive composite scores in the chronic insomnia group. In the control group, the number of nighttime awakenings correlated with inhibition, inhibitory self-control, and the global executive composite. Regression analyses showed a predominant role of insomnia factor in the association with EFs in both clinical and control groups.

Conclusions:

Our findings confirm the link between sleep and “higher level” cognitive functioning. The preschool period represents a critical age during which transient sleep problems also might hamper the development of self-regulation skills and the associated neural circuitry.

Citation:

Bruni O, Melegari MG, Esposito A, et al. Executive functions in preschool children with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(2):231–241.

Keywords: executive functions, insomnia, preschool, sleep

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: The preschool period is marked by the acquisition of core executive functions (EFs) and sleep plays a critical role in neuroplasticity of the prefrontal cortex and correlated EFs. Sleep problems occur with high frequency in preschool age and might interfere with the children’s ability to develop EFs skills and with the correct development of cognitive abilities.

Study Impact: Children with chronic insomnia show significant impairment in all the EFs domains, compared to children in the control group. The presence of early sleep problems can undermine the healthy development of critical cognitive abilities and negatively affect early learning

INTRODUCTION

Sleep regulation represents one of the earliest adaptive behaviors, with sleep/wake time modulation rapidly evolving during the first years of life, connected to structural, biochemical, and cognitive developmental changes. Toddlers and younger preschool children can spend more time asleep than awake. The higher need of sleep during early infancy is likely a function of the development of the neural circuitry subserving the rapid age-related changes of behavioral self-regulation skills.1

An adverse association between health indicators and inadequate sleep patterns has been reported in the pediatric population2; thus, the understanding of the implications of sleep problems for processes related to development is a critical benchmark for health policy.

Chronic insomnia is highly prevalent in children and may be influenced by medical (ie, pain, obstructive sleep apnea) and mental health problems, as well as by maladaptive sleep practices.3,4 It includes delayed sleep onset, bedtime resistance to falling asleep, or protracted awakenings requiring parental involvement during the night. In the preschool period, sleep problems may affect up to 30% of children and, although a substantial decline has been observed in their prevalence over the years, these difficulties still tend to occur in 11% to 15% of children during the school-age period.5

The negative effects of sleep problems on general cognitive functioning are supported by a large body of literature, in children in both clinical and control groups.6–10 Among the cognitive processes, difficulties in executive functions (EFs) have been identified to be particularly sensitive to sleep disruption/deprivation,11 because of the consequence of sleep loss on the prefrontal cortex (PFC).12–14

EFs are referred to as a set of processes involved in the regulation, execution, and generation of behaviors, such as focused attention, cognitive flexibility, working memory, or emotional regulation.

In a review, Beebe15 described difficulties in EFs in children with sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), indicating that deficits in EFs may be attributable to sleep disruption, or hypoxemia, or to the combination of both. Nelson et al11 reported a specific pattern of association of sleep problems with EFs in young children: sleep problems were negatively correlated with performance on tasks assessing working memory and interference suppression inhibition, even after controlling for general cognitive abilities, but not with flexible shifting or response inhibition.

The preschool period is marked by the acquisition of core EFs (eg, inhibition, cognitive flexibility), while more complex skills (eg, problem solving, goal setting, reasoning) develop later, during middle childhood and adolescence. EFs can be classified as “cool” or “hot.” Cool EFs are nonemotionally laden functions whereas hot EFs refer to the cognitive abilities needed for motivationally or emotionally salient decision making and goal setting.11

From a developmental perspective, hot EFs emotional regulation begins in the second year of life and increases during preschool age, whereas cool EFs inhibitory control and shifting-flexibility abilities appear by three years of age and do not achieve the complete maturation and integration across the preschool age period.11 Thus, if the integrity of the brain is altered during early childhood, a critical time for the establishment and emergence of executive skills, there is an increased risk for EFs impairment and cumulative deficits.

Structural brain imaging studies have shown that the PFC is specifically sensitive to disordered sleep16,17; the consequences of poor sleep are more evident for “higher-level” cognitive skills such as executive control (EC), compared to general cognitive functioning, in both children14 and adults.18

Thus, early sleep disruption/deprivation interfering with neurophysiological developmental processes may alter the developing PFC structures and their related maturational processes implicated in cognitive executive functioning.13,19,20 However, it should be considered that an underdeveloped capacity for self-regulation linked to biological factors (ie, difficult temperament) might interfere with the children’s capability to establish consistent sleep patterns.

Only few studies have been carried out evaluating the effect of disordered sleep in infants and children on EF.21 Longitudinal studies, focusing on EFs at 222 or 4 years of age,23 showed that sleep is prospectively associated with EF, similarly to what has been observed in school-age children.24,25 Bernier et al23 showed that children obtaining higher proportions of their sleep at night during infancy performed better, 3 years later, on a task calling upon complex EFs such as abstract reasoning, concept formation, and problem-solving skills, but they did not show better general cognition.

Although healthy sleep plays an important role in children’s daytime functioning, the role that persistent sleep disruption plays on different EFs has not been assessed in detail, with few reports focusing mainly on children with SDB.14

It is surprising, in consideration of the high prevalence of sleep disturbances among preschool-age children (approximately 30%) and their clearly negative effects on EFs, that very few studies have been carried out in healthy young and preschool-age children and limited only to children without sleep problems.11,22,23 Moreover, because sleep problems occur with high frequency at a developmental stage during which self-regulation processes and associated neural circuitry undergo rapid age-related changes, it is extremely important to evaluate the role that persistent sleep disruption plays on different EFs domains, in this specific development period. To our knowledge, no studies have been carried out evaluating EFs in children with sleep disturbances such as insomnia, frequent awakenings, or difficulty falling asleep. In order to fill this gap in the literature, the aims of our study were: (1) to compare sleep patterns and habits in preschool-age children with chronic insomnia with a matched control group, (2) to compare their EFs abilities, and (3) to evaluate the relationship between sleep patterns and EFs within the two groups.

METHODS

Participants

Clinical group

The clinical group consisted of 45 preschool-age children with insomnia (28 boys, 62.2%), aged 24–71 months (mean = 41.2 months, standard deviation [SD] = 15.47), and recruited at the Pediatric Sleep Center of the Sapienza University, Rome, Italy. All children of this group were referred by pediatricians because of their insomnia resistant to the most commonly used treatments (mainly over-the-counter products) and not responding to behavioral techniques. All children fulfilled the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3) criteria for chronic insomnia defining it as “a persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep, and results in some form of daytime impairment.”

The parents or caregivers reported one or more of the following (> 3 times/week lasting for > 3 months): difficulty initiating sleep or maintaining sleep, waking up earlier than desired, resistance going to bed on appropriate schedule, difficulty sleeping without parent or caregiver intervention. The reported sleep/wake complaints could not be explained purely by inadequate opportunity (ie, enough time allotted for sleep) or inadequate circumstances (ie, safe, dark, quiet, and comfortable environment) for sleep.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were presence of diagnosed medical disorders, neurological/psychiatric disorders, and presence of intercurrent diseases that would require treatment with drugs potentially affecting sleep (eg, antihistamines, steroids).

Control group

The control group comprised 167 preschool children (81 boys, 49%) aged 24–71 months (mean = 44.3 months, SD = 10.52) recruited from different preschool/kindergartens. Children with diagnosed medical disorders and/or neurological/psychiatric problems were excluded.

This study was approved by the ethic commission of the Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome.

Procedures

Parents of children of the clinical group were approached by doctors during the hospital visit and invited to join the study. Parents of children of the control group were contacted by researchers and schoolteachers with an explanation of the aims of the study. In both groups, parents completed two deidentified questionnaires to assess their children’s sleep habits and patterns, as well as their EFs. All the questionnaires were administered in Italian. A written parental consent was obtained for all children before inclusion in the study. Participation to the study was voluntary and participants were not paid.

Measures

Assessment of sleep

To assess the infant sleep-related difficulties and habits, all mothers completed the following measures:

-

1.

Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ).26 The BISQ assesses children’s sleep patterns and habits and is composed of questions regarding the following areas: (1) bedtime, (2) rise time, (3) nocturnal sleep duration, (4) daytime sleep duration, (5) number of nighttime awakenings, (6) nocturnal wakefulness, (7) latency to falling asleep during the night (ie, 5 to 15 minutes, 16 to 30 minutes, 31 to 60 minutes, > 60 minures), (8) method of falling asleep (ie, feeding, hold in arms, in parent bed, alone in own bed, and rocked), (9) sleeping arrangement (ie, parents bed, crib in the parents’ room, own room with siblings, own room alone, other), (10) preferred body position (on his/her belly, on his/her side, on his/her back), and (11) frequency of nocturnal awakenings (every night, 5 to 6 nights per week, 3 to 4 nights per week, 1 to 2 nights per week, and fewer than 1 night per month). At the end, parents completed a question on (12) their perception about their child’s sleep as a problem on a three-point Likert scale (a very serious problem, a small problem, not at all a problem). Although the BISQ has been developed for infants, we decided to use the same instruments also for older children for uniformity because the information needed was mainly related to sleep duration, night awakenings, and sleep latency.

-

2.

The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children - adapted (SDSC).27 A revised version of the SDSC questionnaire was used and adapted for use with toddlers in order to identify the presence of sleep disturbances. From the original scale, we selected 15 items (removing 11 items deemed to be inappropriate for this age). Responses were given on a three-point Likert scale with higher values reflecting a greater difficulty of the assessed dimension. A principal component analysis on 15 items revealed three extracted factors: (1) Insomnia (composed of 6 items, difficulty falling asleep, sleep latency > 30 min, bedtime struggles, night awakenings > 2, night awakening screaming, awakening feeling tired) with factor loadings ranging from 0.48 and 0.88 (α clinical group = 0.72, α control group = 0.78); (2) parasomnias (composed of 5 items, eg, nightmares, sleeptalking, sleep terrors, sleepwalking, bruxism) with factor loadings ranging from 0.47 and 0.72 (α clinical group = 0.65 α control group = 0.57), and (3) respiratory disturbances during sleep (composed of 4 items, snoring, difficulty breathing, sleep apnea, night sweating) with factor loadings ranging from 0.47 and 0.78 (α clinical group = 0.62, α control group = 0.59.

Assessment of EFs

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - Preschool version (BRIEF-P)28 was developed in order to provide information about specific subcomponents in EFs through observable behavioral manifestations of these processes in children aged 2–5 years. The scale is composed of 63 items on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 2 = Sometimes, and 3 = Often) assessing EFs within five domains: (1) Inhibit - the children’s ability to modulate their behavior and control impulses, (2) Emotional control - the child ability to modulate emotional responses, (3) Plan/Organize - the children’s ability to anticipate future events, to set goals, and to plan steps in order to complete tasks, (4) Shift - the children’s ability to shift from one activity to another, and (5) Working Memory - the children’s ability to keep information in mind to complete a task.

Exploratory factor analyses performed in the normative sample and in a mixed clinical sample (age 2 to 5 years) yielded three latent factors that proved to be stable across raters and the presence of neurodevelopmental disorders: the Inhibit and Emotional Control subscales constituted the broader construct of “Inhibitory Self-Control.” Combined with the Shift subscale, Emotional Control also loaded onto a second factor, which was labeled “Flexibility.” The third factor, “Emergent Metacognition” comprised the Working Memory and Plan/Organize subscales, referring to the developing metacognitive aspects of EFs. Together, the five domains of EFs form the global executive composite score.

Information on this scale structure, administration, norms, score interpretation, current reliability and validity evidence, and general guidelines for clinical use have been published.29

An Italian version of the BRIEF-P is available,30 which was completed by the parents. For each aspect of EFs, higher scores mean difficulties in the specific EFs. For the statistical analysis we used the raw scores because a comparison between the two groups was needed (t scores are more useful for the clinical application of the scale, when it is needed to evaluate a single patient, in comparison to a normed population).

Internal consistency was good for both the clinical and control groups: (1) inhibit dimension (α clinical group = 0.88, α control group = 0.85); (2) emotional control dimension (α clinical group = 0.85, α control group = 0.76); (3) plan/organize dimension (α clinical group = 0.78, α control group = 0.77); (4) shift dimension (α clinical group = 0.79, α control group = 0.72); and (5) working memory dimension (α clinical group = 0.90, α control group = 0.85).

Statistical analysis

First, the t test was used to assess differences between the clinical group and control group in age, sleep habits (ie, bedtime, rise time, nocturnal sleep duration, daytime sleep duration, number of nighttime awakenings, nocturnal wakefulness), and EFs. Then, we performed a series of χ2 tests to compare the clinical and control groups for sex, their method of falling asleep, location of sleep, preferred body position, and latency to falling asleep during the night. Pearson correlations were run separately in each group to examine the correlation between EFs and children’s sleep habits. For this test, because the difference in size of the two groups was high (control group almost four times more numerous than patients) and the tendency to obtain statistically significant r values, even if small, with increasing sample size, we considered as significant only medium-to-large r values (≥ .30), if they were also accompanied by a value of P < .05.31 Finally, a series of multiple hierarchical regression analyses were conducted in order to understand the link between the SDSC-derived factors (ie, insomnia, parasomnias, and respiratory disturbances during sleep) and EFs, separately in the clinical and control groups.

The commercially available software STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 6, StatSoft Inc. (Tulsa, OK; 2001) was used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

None of the study variables had deviations from normality (values less than 2 for skewness and 7 for kurtosis).32 There were no significant differences between the clinical and control groups for sex (χ2 = 2.671, P = .10) nor significant age differences between the two groups (F1,211 = 2.494, P = .12, partial η2 = 0.01).

Differences in sleep habits and patterns

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for the clinical and control groups are reported in Table 1. We found differences for rise time, nocturnal sleep duration, number of nighttime awakenings, and nocturnal wakefulness. No differences between the two groups emerged for bedtime and daytime sleep duration.

Table 1.

Comparison of sleep problems and habits in the clinical and control groups.

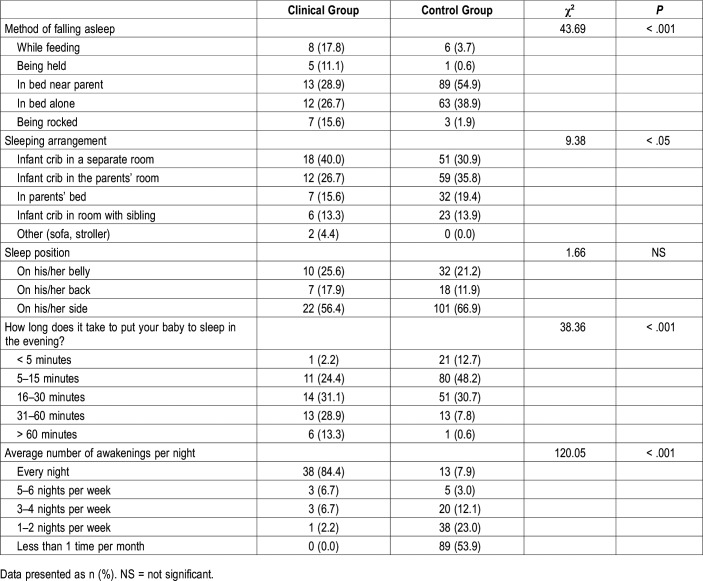

Regarding the method to fall asleep (Table 2), children in the clinical group were found to be more frequently held in arms and rocked than those in the control group (standardized residual for the clinical group 3.2 and 3.3, standardized residual for the control group = −1.7 and −1.7, respectively). These children were also reported to have feeding as the method to fall asleep (standardized residuals = 2.8) more frequently than children in the control group (standardized residual = −1.5).

Table 2.

Method of falling asleep, sleeping arrangement, sleep position, settling time, and number of nights with awakenings (Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire) in the clinical and control groups.

No significant differences emerged for sleep position.

The comparison of the SDSC-derived factors in the two groups revealed significant differences on all three factors (ie, insomnia, parasomnias, and respiratory disturbances during sleep), with higher scores in the clinical group. However, none of the participants either in the clinical or control groups scored in the clinical range for respiratory disturbances.

Differences in EFs

Significant differences between the clinical and control groups were found in all aspects of EFs (Table 3). More specifically, the clinical group reported more difficulties in inhibition, emotional control, planning/organizing, shifting, working memory, inhibitory self-control, emergent metacognition, and global executive composite than the control group.

Table 3.

Executive function components in the clinical and control groups.

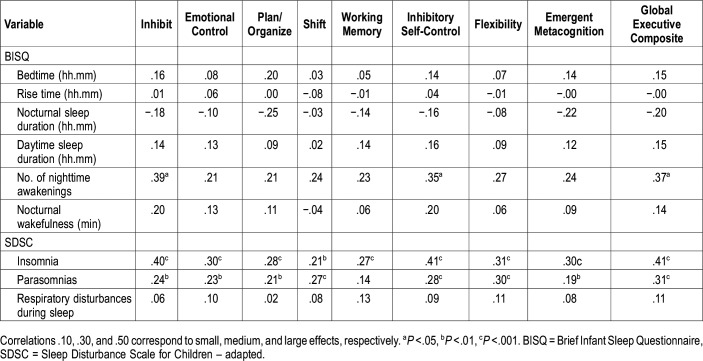

Correlation between sleep and executive functions

In the clinical group, zero-order correlations (Table 4) revealed significant and negative correlations (with a medium effect) between nocturnal sleep duration and inhibit, plan/organize, working memory, inhibitory self-control, emergent metacognition and the global executive composite. Positive and significant correlations (with a medium effect) were found between number of nighttime awakenings and inhibit, emotional control, inhibitory self-control and flexibility. Nocturnal wakefulness was positively correlated with emotional control and inhibitory self-control. The SDSC insomnia factor was significantly correlated with higher scores in inhibition, emotional control, inhibitory self-control, and global executive composite.

Table 4.

Correlations between executive functions and sleep problems and habits within the clinical group.

In the control group, zero-order positive correlations (and medium effects) were found between the number of nighttime awakenings and inhibition, inhibitory self-control and the global executive composite (Table 5). The SDSC insomnia and parasomnias factors were positively associated with higher scores in all the EFs dimensions.

Table 5.

Correlations between executive functions and sleep problems and habits within the control group.

Sleep problems as predictors of EFs

We conducted different hierarchical regression analyses to understand the link between the SDSC factors insomnia, parasomnias, and respiratory disturbances during sleep and EFs (dependent variables). Child sex and age were entered as control variables in each multiple hierarchical regression analysis (Table 6). In the clinical group, the SDSC insomnia factor predicted difficulties mainly in hot EFs, such as inhibition, emotional control, and inhibitory self-control, and global executive composite. No other significant correlations were found.

Table 6.

Multiple hierarchical regression analyses between the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children – adapted factors and executive functions within the clinical and control group.

For the control group, the SDSC insomnia factor predicted higher scores not only in hot EFs (inhibition, emotional control) but also in cool EFs (plan/organize, inhibitory self-control, flexibility, emergent metacognition), and global executive composite. Furthermore, the SDSC parasomnias factor predicted difficulties in shifting, flexibility, and global executive composite. No other significant correlations were found (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating EFs in children with chronic insomnia in comparison to with children in a control group.

As originally hypothesized, we found that the patients with chronic insomnia show decreased night sleep duration and increased number of night awakenings and nocturnal wakefulness. Furthermore, sleep habits in this clinical group were found to be different from those of the control group so that parents adopted dysfunctional methods of falling asleep, contributing to reinforce the disregulated sleep patterns. All these dysfunctional habits and sleep disruption seem to be similar to those of children with sleep problems reported in the literature.33

Children in the clinical group performed poorly in all EFs dimensions when compared to the control group. This finding is in agreement with the literature showing a strict relationship between sleep disturbance and executive functioning. A comprehensive review reported similar findings in children with SDB, suggesting impairment in multiple EFs domains in pediatric SDB,34 but still no studies evaluated this relationship in children with chronic insomnia.

Our findings show that distinct sleep problems affect specific EFs abilities in the two groups: in the clinical group, sleep duration, the number of nighttime awakenings, and nocturnal wakefulness were correlated with greater impairment in several EFs; in healthy children, the number of night awakenings correlated with poorer performance on inhibitory EFs components.

In agreement with our findings, Bernier et al22 showed that the percentage of nighttime sleep, at 12 and 18 months of age, was associated with several EFs indices: night sleep at 12-month was correlated with both conflict and impulse control at 26 months of age, whereas night sleep at 18 months was correlated with concurrent working memory and later impulse control. Children obtaining a higher percentage of their sleep during night time were more advanced in their EF development and this was confirmed by the same authors on the longitudinal study with children obtaining higher proportions of their sleep during infancy performing better on complex EFs 3 years later (abstract reasoning, concept formation, and problem-solving skills).23

As an additional support, a more recent longitudinal study reported a strong association between sleep problems in preschool and subsequent EFs performance in elementary school. More specifically, greater sleep problems were associated with poorer performance on a working memory task, and interference suppression task but not on a response inhibition task.11 Sadeh et al35 reported that poorer infant sleep quality (measured by actigraphy), at 1 year of age, was associated with increased attention and behavior regulation problems in preschoolers. Karpinski et al36 reported that SDB was associated with poorer EFs in preschoolers. In an experimental design, Gruber et al37 found that even a modest sleep restriction was associated with greater impulsivity in children aged 7 to 11 years. These negative cognitive and behavioral effects are believed to be due to the deleterious effect of sleep disruption on the PFC where EC abilities are centered.13

Furthermore, in our study the models of association between SDSC factors and EFs showed that the SDSC insomnia factor mostly predicted the impairment of inhibitory and emotional control EFs in the clinical group and the scores at the emotional and cognitive EFs in the control group. SDSC parasomnia factor was associated with shifting and flexibility in the control group only.

The different pattern of association between sleep and EFs in our two groups suggests that sleep disruption seems to cause a more pervasive impact on executive functioning in control children than in children with chronic insomnia in whom the associations were limited to control of emotional and inhibitory functioning.

All these data confirm that sleep problems are able to interfere with the children’s ability to develop EFs skills in the daily life.20,38

There is a bidirectional interaction between sleep and EFs: deficits in early PFC development leading to poor EC might compromise a child’s ability to effectively regulate attention and behavior in preparation for sleep; however, chronic sleep problems might affect EFs development through deleterious effects on the PFC, leading to a “vicious circle” of escalating EFs and sleep problems across development. Previous studies documenting the negative effects of sleep loss on EC have highlighted sleep as a potential target to improve cognitive functioning; similarly, interventions to improve early EC development might better equip children with the self-regulatory abilities needed to develop lifelong healthy sleep habits and other critical health behaviors.38

When considering interactions of this nature it is not unlikely that difficulties with EF may be inherited, at least to some extent. It is reasonable to consider the possibility that parents with EF difficulties may be more likely to have children with EF difficulties and problems in self-regulation at bedtime. Epigenetic and genetic components in the family are probably very important in the phenotype of sleep problems.39

Although EFs can be understood in general terms, a distinction can be made between the development of relatively hot affective aspects of EFs and the development of more purely cognitive, cool aspects.40 Hot and cool EFs show different timing of development in preschool age, paralleling the maturation of the PFC41 and it has been suggested that sleep plays a critical restorative role in its functioning and neuroplasticity.42–44

Imaging research suggests that hot EFs (emotional and inhibitory control) are subserved by the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and ventromedial regions of the PFC, which have connections to the amygdala and the limbic system, implicated in emotional processing, and mature in the second year of life.45 Conversely, cool EFs seem to be strictly related to a network involving the dorsolateral PFC, the thalamus, basal ganglia, hippocampus, and association areas of the neocortex, important for cognition, that require a more mature PFC development.46–48

Even short-lasting sleep deficits can disturb the function of PFC, which in turn leads to disorders of attention and divergent thinking, difficulties in making decisions, disorders of memory, and inhibition of reactions.49

Lack of sleep, to which the prefrontal cortex areas are most susceptible, seems to affect more cool EFs (inhibition, plan/organize, working memory, and shifting). However, a differentiation between the effect on cool and hot EFs seems to be difficult to disentangle.

Some studies show that chronic sleep deprivation decreases connectivity between the amygdala, the OFC, and the medial PFC and increases connectivity between the amygdala and the autonomic-activating centers of the locus coeruleus, disrupting the emotion regulation by degrading top-down inhibitory processes of emotional reactions.50 Our findings seem to confirm this hypothesis, that is, in children with chronic insomnia, sleep disruption mainly affects the inhibitory and emotional control that are subserved by the OFC and medial PFC. In these children both nocturnal sleep duration and night awakenings correlate with emotional regulation and inhibition, supporting the hypothesis that the severity of sleep fragmentation, and not only sleep duration, is related to hot EFs. We can hypothesize that, as reported in adults, dysfunctions in sleep-wake regulating neural circuitries might reinforce emotional disturbances on the one hand, and, on the other hand, dysfunctional emotional reactivity (hot EFs) might mediate the interaction between cognitive and autonomic hyperarousal.51

In control children, insomnia seems to predict also cool EFs; although it is difficult to explain, we might postulate that in healthy children a transient state of insomnia alters differentially the PFC circuits.

Overall, our findings confirm that a persistent disruption of sleep in children with insomnia is associated with an altered modulation of the control of emotions, whereas a sleep disruption in otherwise healthy children also might affect the brain circuits involving the dorsolateral PFC and cortical associative areas involved in the integration between EFs components, resulting in a deficit of cool EFs.52

Some limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. This is a cross-sectional study and it does not allow to draw conclusions on the effects of insomnia on the development of EFs over time. Preschool sleep problems were measured using a parent-report scale rather than objective measurements and parents may not be accurate reporters of sleep problems. Furthermore, the findings might be the result of a report bias—parents who report more sleep problems also report more EF difficulties. Moreover, our study did not examine various environmental and biologic factors that can be important for understanding the sleep-EC relationship. The role of the family environment, including family stress and adverse events, as well as possible neurodevelopmental mechanisms underlying the overlap between sleep problems and EC deficits merit future study. Finally, we used the SDSC questionnaire that was adapted for age; however, the Cronbach alpha was satisfactory, and the extracted factors were similar to those of the original standardized questionnaire.

CONCLUSIONS

In the light of our findings, the fact that behavioral sleep problems occur with high frequency at a developmental stage during which the capacity for behavioral self-regulation and associated neural circuitry undergo rapid age-related changes calls for a deeper consideration of the mechanism of the correlation between sleep and neurobehavioral development in children.5

Our findings confirm the data reported in younger (infants) and older (schoolers) children supporting the link between sleep and “higher level” cognitive functioning. The correlations found also in the control group testify that the preschool period represents a critical age during which transient sleep problems also can interfere with the functioning of developing self-regulation skills and their associated neural circuitry. Therefore, we can possibly infer that the different relationship between insomnia and deficit in EFs in children with chronic insomnia and in the control group might underly a different maturational development of EFs and the corresponding neural circuits implicated.

The presence of early sleep problems in this domain merits considerable attention because in preschool children they can undermine the healthy development of critical cognitive abilities and negatively affect early learning and, consequently, long-term academic trajectories, especially without appropriate intervention to counteract the emerging cognitive problems and address the underlying causes of early deficits. Future research is needed to address the many still unanswered questions, such as prospective longitudinal studies using more objective sleep and/or EFs measures.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. This study was partially supported by a fund from the Italian Ministry of Health “Ricerca Corrente” (RC n. 2751598) (R.F.). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BISQ

Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire

- BRIEF-P

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - Preschool version

- EC

executive control

- EFs

executive functions

- ICSD

International Classification of Sleep Disorders

- OFC

orbitofrontal cortex

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- SDB

sleep-disordered breathing

- SDSC

Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children - adapted

REFERENCES

- 1.Ednick M, Cohen AP, McPhail GL, Beebe D, Simakajornboon N, Amin RS. A review of the effects of sleep during the first year of life on cognitive, psychomotor, and temperament development. Sleep. 2009;32(11):1449–1458. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.11.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutil C, Walsh JJ, Featherstone RB, et al. Influence of sleep on developing brain functions and structures in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;42:184–201. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiscock H, Canterford L, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Adverse associations of sleep problems in Australian preschoolers: national population study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):86–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quach J, Hiscock H, Canterford L, Wake M. Outcomes of child sleep problems over the school-transition period: Australian population longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1287–1292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turnbull K, Reid GJ, Morton JB. Behavioral sleep problems and their potential impact on developing executive function in children. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1077–1084. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steenari MR, Vuontela V, Paavonen EJ, Carlson S, Fjallberg M, Aronen E. Working memory and sleep in 6- to 13-year-old schoolchildren. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scher A. Infant sleep at 10 months of age as a window to cognitive development. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81(3):289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M, Keller P. Children’s sleep and cognitive functioning: race and socioeconomic status as moderators of effects. Child Dev. 2007;78(1):213–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Touchette E, Petit D, Séguin JR, Boivin M, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir JY. Associations between sleep duration patterns and behavioral/cognitive functioning at school entry. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1213–1219. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hupbach A, Gomez RL, Bootzin RR, Nadel L. Nap-dependent learning in infants. Dev Sci. 2009;12(6):1007–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson TD, Nelson JM, Kidwell KM, James TD, Espy KA. Preschool sleep problems and differential associations with specific aspects of executive control in early elementary school. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40(3):167–180. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2015.1020946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl R. The impact of inadequate sleep on children’s daytime cognitive function. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996;3(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(96)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beebe DW, Gozal D. Obstructive sleep apnea and the prefrontal cortex: towards a comprehensive model linking nocturnal upper airway obstruction to daytime cognitive and behavioral deficits. J Sleep Res. 2002;11(1):1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blunden S, Beebe DW. The contribution of intermittent hypoxia, sleep debt and sleep disruption to daytime performance deficits in children: consideration of respiratory and non-respiratory sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10(2):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beebe DW. Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: a comprehensive review. Sleep. 2006;29(9):1115–1134. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chee MWL, Tan JC, Zheng H, et al. Lapsing during sleep deprivation is associated with distributed changes in brain activation. J Neurosci. 2008;28(21):5519–5528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0733-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Killgore WDS. Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Prog Brain Res. 2010;185:105–129. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim J, Dinges DF. A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(3):375–389. doi: 10.1037/a0018883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsujimoto S. The prefrontal cortex: Functional neural development during early childhood. Neuroscientist. 2008;14(4):345–358. doi: 10.1177/1073858408316002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maski KP, Kothare SV. Sleep deprivation and neurobehavioral functioning in children. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013;89(2):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynaud E, Vecchierini MF, Heude B, Charles MA, Plancoulaine S. Sleep and its relation to cognition and behaviour in preschool-aged children of the general population: a systematic review. J Sleep Res. 2018;27(3):e12636. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernier A, Carlson SM, Bordeleau S, Carrier J. Relations between physiological and cognitive regulatory systems: infant sleep regulation and subsequent executive functioning. Child Dev. 2010;81(6):1739–1752. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernier A, Beauchamp MH, Bouvette-Turcot AA, Carlson SM, Carrier J. Sleep and cognition in preschool years: specific links to executive functioning. Child Dev. 2013;84(5):1542–1553. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Dev. 2002;73(2):405–417. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. The effects of sleep restriction and extension on school-age children: What a difference an hour makes. Child Dev. 2003;74(2):444–455. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadeh A. A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an Internet sample. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e570–e577. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, et al. The sleep disturbance scale for children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res. 1996;5(4):251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1996.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gioia GA, Espy KA, Isquith PK. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2003.

- 29.Sherman E, Brooks BL. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - Preschool Version (BRIEF-P): test review and clinical guidelines for use. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16(5):503–519. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gioia GA, Espy KA, Isquith PK. BRIEF-P: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version. Italian ed. Marano A, Innocenzi M, Devescovi A, trans-ed. Florence, Italy: HOGREFE Editore; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- 32.Curran PJ, West S, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(1):16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byars K, Yolton K, Rausch J, Lanphear B, Beebe DW. Prevalence, patterns, and persistence of sleep problems in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e276–e284. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mietchen JJ, Bennett DP, Huff T, Hedges DW, Gale SD. Executive function in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing: a meta-analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;22(8):839–850. doi: 10.1017/S1355617716000643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadeh A, De Marcas G, Guri Y, Berger A, Tikotzky L, Bar-Haim Y. Infant sleep predicts attention regulation and behavior problems at 3-4 years of age. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40(3):122–137. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2014.973498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karpinski AC, Scullin MH, Montgomery-Downs HE. Risk for sleep-disordered breathing and executive function in preschoolers. Sleep Med. 2008;9(4):418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gruber R, Cassoff J, Frenette S, Wiebe S, Carrier J. Impact of sleep extension and restriction on children’s emotional lability and impulsivity. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1155–e1161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garon N, Bryson SE, Smith IM. Executive function in preschoolers: a review using an integrative framework. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(1):31–60. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruni O, Sette S, Angriman M, et al. Clinically oriented subtyping of chronic insomnia of childhood. J Pediatr. 2018;196:194–200.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zelazo PD, Müller U, Frye D, et al. The development of executive function in early childhood. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2003;68(3):vii-137. doi: 10.1111/j.0037-976x.2003.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giedd JN, Rapoport JL. Structural MRI of pediatric brain development: what have we learned and where are we going? Neuron. 2010;67(5):728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raven F, Van der Zee EA, Meerlo P, Havekes R. The role of sleep in regulating structural plasticity and synaptic strength: Implications for memory and cognitive function. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kocevska D, Muetzel RL, Luik AI, et al. The developmental course of sleep disturbances across childhood relates to brain morphology at age 7: the generation r study. Sleep. 2017;40(1) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verweij IM, Romeijn N, Smit DJ, Piantoni G, Van Someren EJ, van der Werf YD. Sleep deprivation leads to a loss of functional connectivity in frontal brain regions. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15(1):88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phelps EA, LeDoux JE. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: from animal models to human behavior. Neuron. 2005;48(2):175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson TD, Kidwell KM, Hankey M, Nelson JM, Espy KA. Preschool executive control and sleep problems in early adolescence. Behav Sleep Med. 2018;16(5):494–503. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2016.1228650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casey BJ, Tottenham N, Liston C, Durston S. Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(3):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson CA, Thomas KM, de Haan M. Neuroscience and Cognitive Development: The Role of Experience and the Developing Brain. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrison Y, Horne JA. One night of sleep loss impairs innovative thinking and flexible decision making. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1999;78(2):128–145. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1999.2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoo SS, Gujar N, Hu P, Jolesz FA, Walker MP. The human emotional brain without sleep–a prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr Biol. 2007;17(20):R877–R878. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K, Lombardo C, Riemann D. Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(4):227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y, Wang E, Zhang H, et al. Functional connectivity changes between parietal and prefrontal cortices in primary insomnia patients: evidence from resting-state fMRI. Eur J Med Res. 2014;19(1):32. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-19-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]