Abstract

Study Objectives:

The accuracy of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) screening instruments in seniors may change as the predictive role of sex, age, and body mass index (BMI) changes with aging. We investigated the diagnostic performance of the STOP-BANG questionnaire in older individuals with aging-adapted scores and thresholds.

Methods:

Independent community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older were screened for OSA. The STOP-BANG questionnaire was tested with different configurations and compared to the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) obtained from home sleep apnea testing (HSAT). Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) were tested as possible supplementary screening criteria.

Results:

We recruited 458 individuals with a mean age of 71 ± 5 years, 41% men, BMI of 28.5 ± 4.6 kg/m2. Mild, moderate, and severe OSA were present in, respectively, 34%, 30%, and 19% of the sample. The STOP questions had an area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic curve significantly lower than the STOP-BANG and the STOP+BMI > 28 kg/m2 (STOP-B28). Both STOP-BANG and STOP-B28 had high sensitivity and low specificity in all OSA levels with similar AUC to predict AHI ≥ 5 events/h, 0.64. ESS and AIS were nonsignificant as adjunctive instruments.

Conclusions:

Novel modifications of a standard instrument created the STOP-B28, a simpler-to-obtain and similarly performing variation of the STOP-BANG using fewer inputs, and useful to exclude OSA. Screening seniors via questionnaires to detect OSA is problematic. Considering the 83% OSA prevalence in this age group, it may be a sensible option to indicate objective tests, oximetry, HSAT, or even polysomnography, as a first step in OSA investigation.

Citation:

Martins EF, Martinez D, Cortes AL, Nascimento N, Brendler J. Exploring the STOP-BANG questionnaire for obstructive sleep apnea screening in seniors. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(2):199–206.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, screening, seniors

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Old age correlates with increased prevalence of sleep apnea mainly due to neuromuscular mechanisms, independently of classic predictors as sex and body mass index. In seniors, questions on sex and body mass index may not be determinant in the screening of sleep apnea cases. No specific questionnaires for sleep apnea screening in the elderly have been developed.

Study Impact: This study evaluating and adapting the STOP-BANG questionnaire in the elderly showed inadequate accuracy compared to other studies in younger populations. Adjunctive use of other instruments did not improve diagnostic performance. A valid approach for a clinician may be to skip the questionnaires and screen for OSA starting with home sleep apnea testing or polysomnography in every senior.

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), defined by an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) equal or greater than 5 events/h, is prevalent in about one-third of the general population. OSA prevalence increases with age, reaching up to 95% among seniors past 70 years old.1

The gold standard for OSA diagnosis is the full-night polysomnography performed at the sleep laboratory. However, this is a time-consuming and expensive procedure. Several screening tools were suggested to determine high OSA risk, encouraging the judicious use of sleep studies.2

Meta-analyses data indicate that the STOP-BANG questionnaire3 has the best performance in OSA screening.4,5 Initially created to screen OSA in the surgical population, the STOP-BANG has four questions (STOP) on: snoring, tiredness during the daytime, observed apnea, and high blood pressure; and four items (BANG) on physical features: body mass index > 35 kg/m2, age > 50 years, neck circumference > 40 cm, and male gender.

The risk markers in the STOP-BANG questionnaire may have different characteristics in young and older persons, which may demand restructuring the instrument. Most of the available studies using the STOP-BANG questionnaire for sleep apnea screening were performed including middle-age populations.5 We found no specific studies investigating the diagnostic performance of the STOP-BANG questionnaire in a senior population.

The BANG features of the STOP-BANG questionnaire are the ones more likely to require adaptations when used in older people. First, studies in older adults have concluded that people with a body mass index (BMI) in the overweight range had a similar or lower risk of mortality than those in the BMI normal range (< 25 kg/m2) for younger adults.6,7 Also, normal BMI is more prevalent in seniors than in younger persons.8–10 Second, age older than 50 years in all participants makes this question unnecessary. Third, neck circumference is collinear with sex and BMI. Hence, it may be unnecessary to include this variable in seniors’ OSA screening. Fourth, even though adult men are more likely to have OSA than women,11 in seniors, the sex difference wanes.12 The OSA prevalence in older men and women is quite similar.13 Therefore, the usefulness of the gender item in the STOP-BANG questionnaire may be uncertain for seniors.

Based on these premises, we hypothesized that the STOP-BANG questionnaire requires adaptations to retain its accuracy when used for determining OSA risk in older adults. The purpose of the current study was to analyze the diagnostic performance of the STOP-BANG questionnaire, and combinations of questions to indicate risk of OSA in older adults.

METHODS

Study population

We performed a cross-sectional study with independently living older adults age 65 years or older, participants in an ongoing cohort study (MEDIDAS - GPPG n°. 15-0342) designed to study morbimortality associated with OSA. The cohort included 535 individuals assessed between May 2014 and May 2018 from a database of 2,103 seniors adscript to the primary health care unit of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre. The participants had previously attended the hospital research center to perform OSA screening questionnaires and home sleep apnea testing (HSAT). Exclusion criteria were disability preventing the patient from attending the visit at the research center, incomplete data, unwillingness to undergo HSAT, previous treatment for sleep apnea, and presence of central sleep apnea (more than 50% central apneic events). The Institutional Review Board (IRB0000921) approved the study. All patients signed a form consenting to the anonymous use of their data.

Measurements

Participants answered self-administered standardized questionnaires about their current lifestyle, and health condition. The general health questionnaire included questions about participants’ medication use, surgical history, and previous diagnoses.

The STOP-BANG questionnaire was the studied screening tool. The STOP section includes four questions related to snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, and high blood pressure. Two or more yes answers to STOP questions indicate high OSA risk. The STOP-BANG adds four more questions to the STOP section. The BANG questions assess the OSA risk based on BMI > 35 kg/m2, age > 50 years, neck circumference > 40 cm, and male gender. Three or more yes answers to STOP-BANG questions indicate high OSA risk. In this study, all seniors already had one point on the STOP-BANG questionnaire related to age older than 50 years.

Sleep disruption and daytime dysfunction were gauged by eight questions from the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS)14: (1) “Sleep induction”; (2) “Awakenings during the night”; (3) “Final awakening earlier than desired”; (4) “Total sleep duration”; (5) “Overall quality of sleep”; (6) “Sleeping during the day”; (7) “Well-being during the day”; and (8) “Functioning capacity during the day”. These questions are scored from 0 to 3 points, with 0 meaning no symptoms. Patients were considered as having dysfunction in the AIS if they scored one point in any of the eight questions. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was used to evaluate daytime sleepiness.15 Patients with an ESS score higher than 10 were considered sleepy.

The clinical assessments performed included body weight and height measurements. The BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Neck circumference was measured in centimeters above the thyroid cartilage. Blood pressure was measured using an OMRON HEM (OMRON HEALTHCARE BRASIL INDUSTRIA E COMÉCIO DE PRODUTOS MÉDICOS LTDA, São Paulo, Brazil) 7130 automatic sphygmomanometer, in the sitting position after at least 15 minutes of rest.

Sleep study

Participants underwent home sleep apnea testing (HSAT) using the Embletta Gold (Embla, Denver, Colorado, United States) or the Somnocheck Effort, (Weinmann GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), which was validated against complete polysomnography by our study group.16 Airflow and snoring were recorded by a nasal cannula attached to a pressure transducer while oxygen saturation and heart rate were recorded by a pulse oximeter. The same monitor also recorded body position and respiratory effort. One certified technician manually scored respiratory events lasting 10 seconds or longer. OSA was defined by a 90% or greater drop in flow; hypopnea by a 30% or greater drop in flow accompanied by either a 3% or greater oxygen desaturation or an autonomic arousal identified by an increase of at least six beats per minute in heart rate, as previously reported.17 The AHI was calculated by dividing the total of apneas and hypopneas by the number of hours of artifact-free recording. Older adults with an AHI< 5 events/h were classified as non-OSA; with AHI from 5 to 14 events/h, as mild OSA; with AHI from 15 to 29 events/h, as moderate OSA; and with AHI ≥ 30 events/h as severe OSA.18 A certified sleep medicine specialist reviewed all the sleep studies.

Statistical analysis

We compared categorical data using chi-square, and scale data using t test. The accuracy of the STOP, STOP-BANG questionnaires, and a variation from these questionnaires were described by sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR). Data were analyzed using the SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States) and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) calculations were performed by the MedCalc for Windows software (version 18.4.1.0; MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium). Findings with probability of alpha error < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

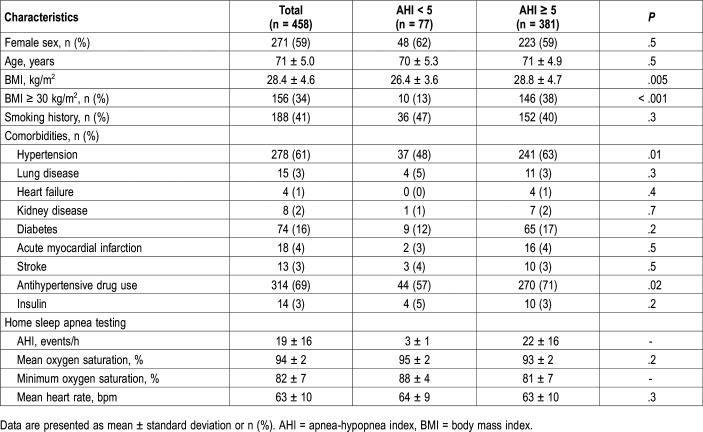

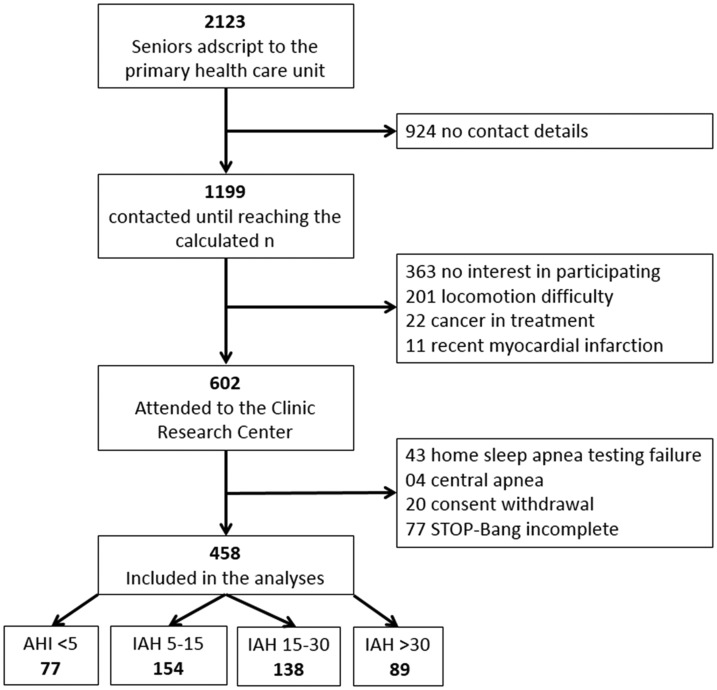

General characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 and study flowchart in Figure 1. From a sample of 602 independent older adults from the community, 458 were included, 41% men. Men and women had similar age (respectively, 71 ± 5.0 versus 70 ± 4.9 years; P = .05), AHI (respectively, 20 ± 17 versus 18 ± 15 events/h; P = .15), and STOP score (respectively, 2.3 ± 1.1 versus 2.4 ± 1.0; P = .44). Because gender scores one point, STOP-BANG score was greater in men than in women (respectively, 4.8 ± 0.3 versus 3.7 ± 1.2; P < .001). The BMI was lower in men than in women (respectively, 27.9 ± 4.0 versus 28.8 ± 5.0 kg/m2; P = .03).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population grouped by presence of obstructive sleep apnea.

Figure 1. Flowchart of study population.

Seniors aged 65 years or older were included from an ongoing cohort and grouped by OSA severity. OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

The proportion of older adults with AHI ≥ 5 events/h was 83% (n = 381), being similar between men and women, respectively, 85% versus 82% (P = .54). Mild, moderate, and severe OSA were present in, respectively, 34%, 30%, and 19% of the sample. OSA cases had greater BMI (respectively, 28.7 ± 4.7 versus 26.4 ± 3.7 kg/m2; P < .001) than non-OSA cases; the neck circumference was nonsignificantly larger (respectively, 39 ± 3.8 versus 38 ± 4.4 cm; P = .08). The proportion of older adults with AHI ≥ 15 events/h in age groups 65 to 70 years, 71 to 75 years, and 76+ years increases from 46%, to 51%, and 59%, respectively (P for trend = .04).

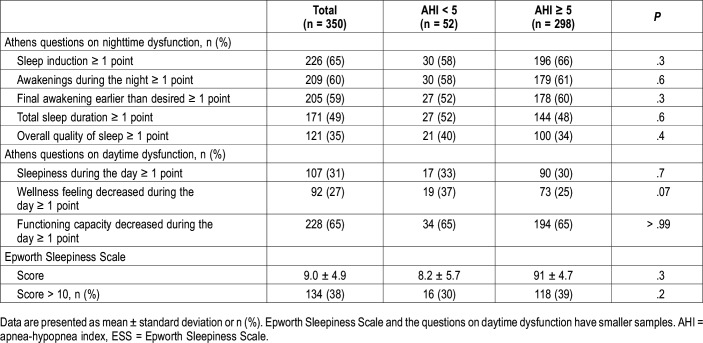

The percentages of patients with at least one point in any of the eight questions from the AIS nighttime or daytime questions and ESS scores are shown in Table 2. The percentage of any dysfunction between the AHI < 5 events/h and AHI ≥ 5 events/h groups was similar for all questions, 68% and 69%, respectively; P = .9. From ESS scores, 39% of the respondents with an AHI ≥ 5 events/h had daytime sleepiness defined as a score higher than 10 points. In the group with AHI < 5 events/h, the frequency of ESS ≥ 10 points was 30%, a difference with no statistical significance.

Table 2.

Nighttime and daytime dysfunction of the study population grouped by presence of obstructive sleep apnea.

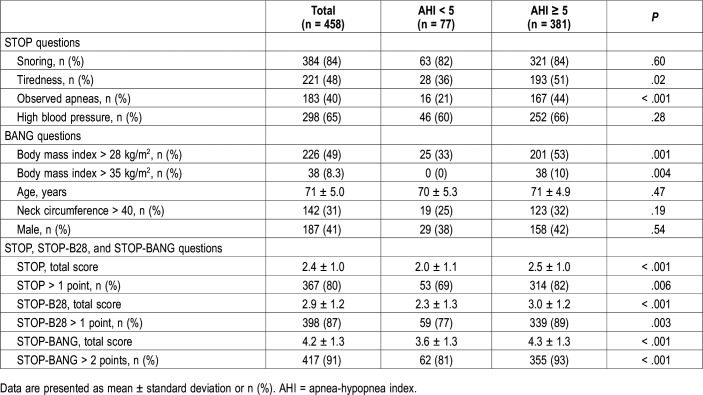

Answers to STOP-BANG questionnaires categorized by OSA category defined at AHI cutoff point of 5 are seen in Table 3. Tiredness, observed apneas, STOP score, STOP > 1 point, STOP-BANG score, and STOP-BANG > 2 points were greater in OSA cases. The neck circumference > 40 cm, male gender, snoring, and hypertension were similar.

Table 3.

STOP, STOP-B28, and STOP-BANG questionnaires in older adults by obstructive sleep apnea groups, defined as AHI ≥ 5 events/h.

The STOP score ≥ 2 points predicted AHI ≥ 5 events/h in 82% of the seniors and was able to predict correctly 31% of the non-OSA cases, 76% of the mild OSA cases, 82% of moderate OSA cases, and 94% of the severe OSA cases. The STOP-BANG score ≥ 3 predicted the AHI ≥ 5 events/h in 93% of seniors and was capable to predict correctly 19% of the non-OSA cases, 90% of mild OSA cases, 94% of moderate OSA cases, and 99% of the severe OSA cases.

Using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), we analyzed the diagnostic performance of different scores and tested several modified versions of the STOP-BANG. The highest AUC was obtained by removing from the BANG section three questions: age, neck, and gender. The item age > 50 years was removed for being a constant, and the neck circumference and the male gender for not changing significantly the AUC when present in the score. BMI was the only variable significantly different between non-OSA and OSA groups (Table 3). Using the recommended 35 kg/m2 BMI cutoff point to predict AHI ≥ 5 events/h showed an AUC of 0.55 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.48 to 0.61). The 28 kg/m2 BMI cutoff point to predict AHI ≥ 5 events/h had an AUC significantly higher than the 35 kg/m2 BMI cutoff point (AUC = 0.64, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.70). Therefore, we adopted the STOP-B28 (STOP+BMI > 28 kg/m2) for the following analyses. The STOP-B28 mean score was higher in OSA than in patients without OSA (3.0 ± 1.2 versus 2.3 ± 1.3, P < .001). The STOP-B28 > 1 point predicted AHI ≥ 5 events/h in 89% of the seniors and classified correctly 23% of the non-OSA cases, 83% mild OSA cases, 91% moderate OSA cases, and 98% severe OSA cases.

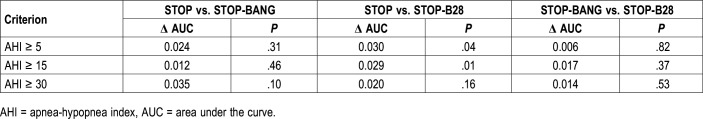

Comparing the AUC of STOP, STOP-BANG, and STOP-B28 questionnaires, adding the BANG section to the STOP section does not increase significantly the AUC in comparison with STOP alone. STOP-B28 is statistically superior to STOP alone and performed similarly to the STOP-BANG (Table 4). To predict AHI ≥ 5 events/h as well as AHI ≥ 15 events/h, the STOP-B28 questionnaire had the higher AUC, respectively, 0.64 and 0.65 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.69 and 0.61 to 0.70). To predict AHI ≥ 30 events/h, the STOP-BANG questionnaire had the higher AUC, 0.69 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.73) but it was virtually the same for all three instruments (Figure S1 in the supplemental material).

Table 4.

Pairwise comparison of AUC of the STOP-BANG, STOP-B28, and STOP questionnaires in older adults by AHI level.

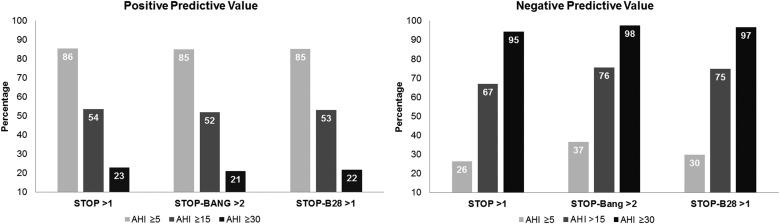

For the STOP, STOP-BANG, and STOP-B28 positive and negative predictive values were evaluated (Figure 2). The PPV found for the three questionnaires was approximately 85%, very close to the actual prevalence. When negative, all three questionnaires carry approximately 30% likelihood of excluding truly OSA-negative patients at the cutoff of AHI > 5 events/h, with a 70% risk of underdiagnosis. Regarding AHI ≥ 30 events/h, the three questionnaires showed adequate performance to exclude negative cases, and poor ability to confirm positive cases.

Figure 2. Bar graph of the PPV and NPV of the STOP, STOP-BANG, and STOP-B28 scores by OSA severity.

The three questionnaires presented high NPVs only with AHI ≥ 30 events/h. AHI apnea-hypopnea index PPV, NPV positive and negative predictive values OSA severity. OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

The AUC of all the three scores—STOP-BANG, STOP-B28, and STOP—were statistically significant, but clinically nonsignificant because AUC is below 70 in all19 (Figure S1). STOP questionnaire had poor diagnostic performance in seniors. Both STOP-BANG as STOP-B28 had high sensitivity and low specificity in all OSA levels. Figure S2A and Figure S2B in the supplemental material display sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, of the three questionnaires for the different OSA severity levels.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, the STOP and STOP-BANG questionnaires had high sensitivity and low specificity to identify seniors with OSA. The proposed STOP-B28 score improves significantly the AUC and may enhance the applicability of a screening tool in seniors. Both STOP-BANG and STOP-B28 had a similar accuracy to predict AHI ≥ 5. Although the STOP-B28 did not perform significantly better than the STOP-BANG, it is a simpler OSA screening instrument.

The prevalence of AHI ≥ 5 events/h in the current study was elevated, 83% of the sample. Therefore, the utility of using a screening method in the presence of such a high prior probability has to be discussed. A diagnostic test starts to show usefulness when the PLR is > 2 and the NLR is < 0.5. With a PLR around 1.2 observed in the current study to detect AHI ≥ 5 events/h, the test’s utility is practically null as the prior probability of 83% is increased to a posterior probability of 82%, 89%, or 93%. However, the instruments could be useful to exclude AHI ≥ 30 events/h, which has a prevalence of around 20%. At this OSA severity grade, any of the three instruments perform similarly in terms of NPV or NLR. Using the NPV or the NLR to identify AHI < 30 events/h may be of importance to select patients in whom the investigation could be delayed in a limited-resource scenario as they represent the less severe cases. In our study, the seniors with no snoring, no tiredness, no apneas, no hypertension, and no BMI > 28 kg/m2 still carried a substantial risk of having mild-moderate OSA but none of them had severe OSA.

To predict AHI ≥ 30 events/h, a STOP-BANG score of 1 or 2 has an excellent NLR of 0.1. This means that a senior with one or two positive answers in the STOP-BANG is 10 times less likely to have severe OSA than one with STOP-BANG score > 2, meaning that a negative questionnaire reduces the prior probability of severe OSA by tenfold, from 20% to 2%. From the perspective of the NPV, a STOP-BANG score of 1 or 2 has an NPV of 98%, indicating that a negative questionnaire reduces the prior probability of severe OSA to 2%.

To predict AHI ≥ 30 events/h, a STOP-B28 score of 0 or 1 has an NLR of 0.14, meaning that a negative questionnaire reduces seven times the prior probability of severe OSA, from 20 to 3%. From the perspective of the NPV, a STOP-B28 score of 0 or 1 has an NPV of 97%, indicating that a negative questionnaire reduces the prior probability of severe OSA to 3%.

Ancoli-Israel et al20 proposed that a cutoff point of AHI 10 events/h could be more suitable to avoid overdiagnosis in older persons. In our study, the accuracy of the STOP-B28 obtained with a cutoff point of 10 events/h (0.62) was lower than the accuracy of a cutoff of 5 events/h (0.64). Several studies of OSA in elderly persons considered only individuals with AHI ≥ 15 events/h as OSA cases; however, no improvement of the diagnostic performance is seen when using this cutoff. To detect OSA at AHI 15 events/h, the accuracy increases from 0.64 to 0.65. The PPV is around 50% and the NPV indicates a 25% probability of not being a “case of interest” for continuing investigation. The same reasoning can be employed regarding the screening of severe OSA. To detect cases with AHI > 30 events/h the accuracy changes from 0.64 to 0.68. It seems that using any of the STOP-BANG-derived instruments may be misleading either to confirm or to exclude severe OSA cases in seniors.

Among the classic OSA confounders of sex, age, and BMI, BMI was the only one significantly, though weakly, (r = .3; P < .001) correlated with the lnAHI. In our sample, only 8.3% of the participants had a BMI > 35 kg/m2, which might increase false-negative results. Hence, we attempted other BMI cutoff points. Comparing AUC for three BMI cutoff points of 35 kg/m2, 30 kg/m2 and 28 kg/m2, the threshold that resulted in an AUC significantly larger than BMI 35 kg/m2 was BMI 28 kg/m2. For that reason, we preferred the 28 kg/m2 cutoff point, recommended by Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde for seniors as overweight cutoff point, taking into account the changes in body composition that occur with aging. A modified STOP-B30 instrument using the standard 30 kg/m2 used for adults obtained an AUC of 0.59. The STOP-B28 AUC of 0.64 was significantly larger.

Regarding the BMI in seniors, in the Wisconsin cohort showed the association of an AHI > 15 events/h with BMI was weaker in older than middle-aged adults. For an AHI > 15 events/h, BMI had an odds ratio (95% CI) of 2.0 (1.7–2.4) at the mean age of 40 years and at the mean age of 80 years the odds ratio is 1.3 (1.1–1.5).21 Also, BMI below 25 kg/m2 is more often present in seniors than in younger age groups, suggesting that a normal BMI does not protect against OSA.8–10 Furthermore, loss of neuromuscular units with aging decreases muscle tone and facilitates airway collapsibility, independently of obesity.22

As already mentioned, the score on age older than 50 years is a constant, not a variable. The neck circumference did not correlate significantly with the AHI or lnAHI (r = .09; P = .06). It was, however, significantly correlated with the BMI (r = .19; P < .001) suggesting that this measurement may provide an OSA risk estimate that is collinear with the BMI. The exclusion of the Neck item from the score results in an AUC of the modified instrument that is similar to that of the STOP-BANG questionnaire.

The frequency of AHI ≥ 5 events/h was similar in men and women (85% and 82%, respectively). The AHI, the STOP questionnaire, and the frequency of comorbid hypertension and diabetes were also similar in men and women. This indicates that the utility of including the item Gender in the STOP-BANG questionnaire may be minor. Indeed, in the current study the accuracy of the total score with or without this question changes negligibly.

In 2008, Chung et al3 developed the STOP-BANG questionnaire specifically for anesthetists to screen for OSA during the preoperative period of surgical patients. Because it is a fast and easy-to-use mnemonic, STOP-BANG is widely applied. It has been considered better than other questionnaires for OSA screening.23 The original description of the STOP-BANG by Chung et al reported that in the cutoffs AHI ≥ 5 events/h, AHI ≥ 15 events/h, and AHI ≥ 30 events/h the STOP-BANG has higher sensibility than the STOP only, mainly in patients with moderate and severe OSA. However, the specificity was low in the questionnaires in all cutoffs of the AHI. The STOP questions alone had a moderate level of sensitivity (65.6% for AHI > 5 events/h; 74.3% for AHI > 15 events/h; 79.5% for AHI > 30 events/h) and specificity (60.0% for AHI > 5 events/h; 53.3 for AHI > 15 events/h; and 48.6% for AHI > 30 events/h) to detect OSA.24 In our sample of elderly patients, the STOP-BANG > 2 and STOP-B28 > 1 also reached high sensitivity and low specificity in all the cutoffs of the AHI. Nevertheless, the authors demonstrated greater AUC than ours. This is probably because of BANG items not fitting well with the senior population.

In 2014, Chung and colleagues published another article25 in an attempt to improve the specificity of the STOP-BANG, avoiding the false-positive results. The authors concluded that in patients with STOP > 1 point, male gender and BMI > 35 kg/m2 were more predictive than age > 50 years and neck circumference > 40 cm. These results demonstrate that age has different influences on younger and older populations.

Studies analyzing the diagnostic performance of the STOP-BANG specifically in community-living senior populations were not found. A study in patients with chronic kidney disease26 concludes, in agreement with us, that STOP-BANG performance is poor and recommends objective OSA diagnostic method in patients with renal disease. Another study assessing the diagnostic performance of the STOP-BANG in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with results of sensibility and specificity similar to ours, recommends OSA screening using home sleep-monitoring devices instead of questionnaires.27 Their data suggest that the presence of comorbidities makes the STOP-BANG less accurate.

Daytime sleepiness could be another possible symptom with screening utility in OSA but our attempt to verify its utility reproduced a disappointing result. In a previous study by our group, the prevalence of ESS > 10 in adults with AHI ≥ 5 events/h was 63%.28 In the current study, the prevalence of ESS > 10 was 39% in seniors with AHI ≥ 5 events/h. Based on this simple comparison, we predict that sleepiness in the elderly may be even less helpful for OSA screening in seniors than it is in adults. Further research is necessary to vouch the sensitivity and specificity of such symptoms if used as justification to perform a sleep test.

One limitation of the current study is the selection bias that incurs in a reduced external validity. Recruitment of women was larger because they were more willing to participate. Most of the male individuals approached refused to participate. Retirement rates (90% of women and 30% of men) implying more time available to attend visits to the research center is one possible reason for a slight male underrepresentation in our sample. Another limitation is the use of HSAT instead of in-laboratory polysomnography. Because of the lack of certainty about the time asleep in a HSAT, it is likely that, the denominator being larger than the actual sleep time, the AHI will be systematically lower. In our study validating the HSAT,16 we observed that, on average, the AHI in polysomnography was around 3 events/h higher than in HSAT. Also, the best AHI cutoff point in HSAT was 7 events/h, equivalent to 5 events/h in polysomnography. If a cutoff point of 7 was used an OSA prevalence of 77% instead of 83% would be obtained in the current sample. The accuracy of the tested indices, however, would remain similar. For instance, the AUC for STOP-B28 would change from 0.64 to 0.63. Apparently, the use of a slightly less accurate apnea detection method does not affect the conclusions of the current study.

We adapted the STOP-BANG questionnaire by eliminating the questions that were not suitable for this population; we adapted the BMI threshold to 28 kg/m2, resulting in better accuracy and a cutoff point more appropriate to the elderly population than 35 kg/m2; we demonstrated that instead of using the STOP-BANG questionnaire in seniors it would be simpler and more sensible to use STOP-B28. Furthermore, the data indicate the use of the STOP-B28 mainly to exclude severe OSA.

This study concludes that the diagnostic performance of the STOP-BANG questionnaire in seniors is insufficient to recommend its ample utilization in screening of OSA. In the presence of the high prior probability of AHI > 5 events/h in seniors, the STOP-BANG questionnaire could be reduced to one question: age ≥ 65 years. A positive answer to this question raises a high suspicion of OSA. Because the PPV found for the three questionnaires was around 85% and the actual prevalence is of 83% the risk of overdiagnosis at the cutoff AHI > 5 events/h is negligible. The clinician who advances the investigation of every senior, using oximetry, HSAT, or polysomnography based simply on age of 65 years or older will identify OSA cases in about 80% of the tests, a diagnostic performance hard to obtain with paper and pencil instruments. Neither sleepiness nor complaints of sleep disruption and daytime dysfunction helped as screening tools. Further studies are needed to identify other signs and symptoms that could be more specific to OSA in seniors and could improve the performance of screening questionnaires in this age group.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at Division of Cardiology, Interdisciplinary Sleep Research Laboratory, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Brazil. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partly supported by Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa (FIPE), Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA, Brazil), and Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- AIS

Athens Insomnia Scale

- AUC

area under the curve

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- HSAT

home sleep apnea testing

- NLR

negative likelihood ratio

- NPV

negative predictive value

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PLR

positive likelihood ratio

- PPV

positive predictive value

REFERENCES

- 1.Tufik S, Santos-Silva R, Taddei JA, Bittencourt LR. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the Sao Paulo Epidemiologic Sleep Study. Sleep Med. 2010;11(5):441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramachandran SK, Josephs LA. A meta-analysis of clinical screening tests for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(4):928–939. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c47b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-BANG questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149(3):631–638. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagappa M, Liao P, Wong J, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG questionnaire as a screening tool for obstructive sleep apnea among different populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu HY, Chen PY, Chuang LP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: A bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;36:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winter JE, MacInnis RJ, Wattanapenpaiboon N, Nowson CA. BMI and all-cause mortality in older adults: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(4):875–890. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.068122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng FW, Gao X, Mitchell DC, et al. Body mass index and all-cause mortality among older adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24(10):2232–2239. doi: 10.1002/oby.21612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung S, Yoon IY, Lee CH, Kim JW. Effects of age on the clinical features of men with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2009;78(1):23–29. doi: 10.1159/000218143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawanyawisuth K, Chindaprasirt J, Senthong V, et al. Lower BMI is a predictor of obstructive sleep apnea in elderly Thai hypertensive patients. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(4):1215–1219. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0826-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Giudice G, Colangeli A, Carducci P, Carunchio M, Di Crecchio R, Fiore-Donati A. Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in elderly population with high and low BMI. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:2194. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sforza E, Chouchou F, Collet P, Pichot V, Barthélémy JC, Roche F. Sex differences in obstructive sleep apnoea in an elderly French population. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(5):1137–1143. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00043210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senaratna CV, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48(6):555–560. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Oliveira ACT, Martinez D, Vasconcelos LF, et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and its outcomes with home portable monitoring. Chest. 2009;135(2):330–336. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayappa I, Rapaport BS, Norman RG, Rapoport DM. Immediate consequences of respiratory events in sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2005;6(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, Jr, Quan SF. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2000:160-164. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Mason WJ, Fell R, Kaplan O. Sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14(6):486–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the sleep heart health study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(8):893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eikermann M, Jordan AS, Chamberlin NL, et al. The influence of aging on pharyngeal collapsibility during sleep. Chest. 2007;131(6):1702–1709. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo J, Huang R, Zhong X, Xiao Y, Zhou J. STOP-BANG questionnaire is superior to Epworth sleepiness scales, Berlin questionnaire, and STOP questionnaire in screening obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127(17):3065–3070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812–821. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung F, Yang Y, Brown R, Liao P. Alternative scoring models of STOP-BANG questionnaire improve specificity to detect undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(9):951–958. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholl DD, Ahmed SB, Loewen AH, et al. Diagnostic value of screening instruments for identifying obstructive sleep apnea in kidney failure. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(1):31–38. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westlake K, Plihalova A, Pretl M, Lattova Z, Polak J. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective study on sensitivity of Berlin and STOP-BANG questionnaires. Sleep Med. 2016;26:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez D, Breitenbach TC, Lumertz MS, et al. Repeating administration of Epworth Sleepiness Scale is clinically useful. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(4):763–773. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.