Abstract

Surveillance data indicate that tick-borne diseases (TBDs) are a substantial public health problem in the United States, yet information on the frequency of tick exposure and TBD awareness and prevention practices among the general population is limited. The objective of this study was to gain a more complete understanding of the U.S. public’s experience with TBDs using data from annual, nationally representative HealthStyles surveys. There were 4728 respondents in 2009, 4050 in 2011, and 3503 in 2012. Twenty-one percent of respondents reported that a household member found a tick on his or her body during the previous year; of these, 10.1% reported consultation with a health care provider as a result. Overall, 63.7% of respondents reported that Lyme disease (LD) occurs in the area where they live, including 49.4% of respondents from the West South Central and 51.1% from the Mountain regions where LD does not occur. Conversely, in the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions where LD, anaplasmosis, and babesiosis are common, 13.9% and 20.8% of respondents, respectively, reported either that no TBDs occur in their area or that they had not heard of any of these diseases. The majority of respondents (51.2%) reported that they did not routinely take any personal prevention steps against tick bites during warm weather. Results from these surveys indicate that exposure to ticks is common and awareness of LD is widespread. Nevertheless, use of TBD prevention measures is relatively infrequent among the U.S. public, highlighting the need to better understand barriers to use of prevention measures.

Keywords: Tick-borne disease, Lyme disease, Prevention, Tick exposure

Introduction

From 2009 to 2013, over 200,000 cases of tick-borne diseases (TBDs) were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), including cases of anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease (LD), Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), and tularemia (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010, 2013). LD, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted by Ixodes spp. ticks, leads in number of cases with over 36,000 confirmed and probable cases reported in 2013. Several novel tick-borne pathogens recently have been found to cause human illness in the United States: Borrelia miyamotoi, Ehrlichia species Wisconsin, and Heartland virus (Krause et al., 2013; Mcmullan et al., 2012; Pritt et al., 2011). In addition, southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI or Masters’ disease), which mimics the erythema migrans rash of early LD, is associated with the bite of the Amblyomma americanum tick but is of unknown etiology (Wormser et al., 2005). Diverse in their vectors, geographic distribution, and clinical manifestations, TBDs represent a substantial public health problem in the United States.

In the absence of available vaccines (Food and Drug Administration, 2002; Shen et al., 2011) or easily implemented community-wide interventions, prevention of TBDs relies heavily on the consistent use of personal prevention measures and environmental tick controls on personal property (Connally et al., 2009; Curran et al., 1993; Schulze et al., 1994, 1995; Stafford, 2004). Implementation of these measures is largely contingent upon individuals’ awareness of TBD risk where they live and recreate. Information on levels of TBD awareness and use of prevention measures among the U.S. public is lacking. In addition, several other important aspects of TBDs such as frequency of tick exposure and health care seeking behavior have not been quantified. Using data from nationwide HealthStyles surveys, this study was undertaken to gain a more complete understanding of the U.S. population’s experience with TBDs to guide prevention and control efforts.

Materials and methods

HealthStyles is an annual, cross-sectional, nationwide survey designed to be nationally representative based on U.S. Census Bureau demographics. Porter Novelli, a social marketing and public relations firm, has conducted the HealthStyles survey since 1995, and CDC annually licenses results from the survey post-collection. Survey questions aim to assess knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors for various health-related topics and to obtain information on self-reported diseases and conditions (Kennedy et al., 2011; Kobau et al., 2006; Polen et al., 2015). In general, HealthStyles surveys demonstrate reliability and validity, showing concordance with the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System on outcome levels, trends over time, and demographic breakdowns for similar health topics (Pollard, 2007).

HealthStyles survey respondents are randomly recruited each year from a large, nationally representative panel of non-institutionalized adults aged ≥18 years living in the contiguous United States and the District of Columbia. The 2009 HealthStyles survey was administered via mail, and the 2011 and 2012 surveys were administered online (Porter Novelli Public Services, 2009a, 2011a, 2012a). Each survey took approximately 40 minutes to complete. The specific questions regarding awareness of, prevention measures for, and experiences with TBDs are shown in Table 1 (Porter Novelli Public Services, 2009b, 2011b, 2012b). Response data were weighted using several demographic factors to ensure representativeness according to Current Population Survey (CPS) demographic proportions and to reduce potential nonresponse bias (US Census Bureau, 2006). (See Appendix A for details on sampling methodologies and demographic factors used for weighting in 2009, 2011, and 2012.)

Table 1.

HealthStyles tick-borne disease survey questions and year questions were asked.

| 1. | “In the last year, did anyone in your household find a tick on their body?” Select one: Yes; No; Not sure (2009) |

| 2. | “If yes, did this person consult a health care provider because of finding a tick?” Select one: Yes; No; Not sure (2009) |

| 3. | “Have you ever been diagnosed with Lyme disease?” Select one: Yes; No; Not sure (2009, 2012)a |

| 4. | “If yes, how long were you treated with antibiotics?” Select one: 4 weeks or less; 5–8 weeks; Longer than 8 weeks; I did not receive antibiotic treatment (2009) |

| 5. | “Do you personally know anyone who describes themselves as having chronic Lyme disease?” Select all that apply: Yes, I know someone; No, I do not know anyone; I suffer from chronic Lyme disease (2011) |

| 6. | “Which of the following diseases spread by ticks occur in the area where you live?” Select all that apply: Lyme disease; Rocky Mountain spotted fever; Anaplasmosis; STARI or Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness; Ehrlichiosis; Tularemia; Babesiosis; Tick-borne Relapsing Fever; None of these diseases occur in my area; I have not heard of any of these (2009) |

| 7. | “Would you use chemical pesticides up to one or two times per year if they would meaningfully reduce the number of ticks in your yard/on your property?” Select one: I already use them; Yes, I would consider them; Maybe I would use them; No, I would not use them; Not sure; Don’t have a yard/land (2009) |

| 8. | “When the weather is warm in your area, what steps, if any, do you routinely take to prevent tick bites?” Select all that apply: I wear repellent; I shower soon after coming indoors; I check my body for ticks when I come in; I take other steps that are not listed above; I do not take any steps to prevent ticks bites (2011) |

In 2012, respondents were asked, “Have you ever been diagnosed with Lyme disease?” Response options included: “No; Yes, within the past the past 6 months; Yes, 7–11 months ago; Yes, 1–2 years ago, Yes, 3–5 years ago; Yes, more than 5 years ago.” Due to a small number of responses for any of the “Yes” options, these responses were collapsed into a single “Yes” for those who reported ever having been diagnosed with LD.

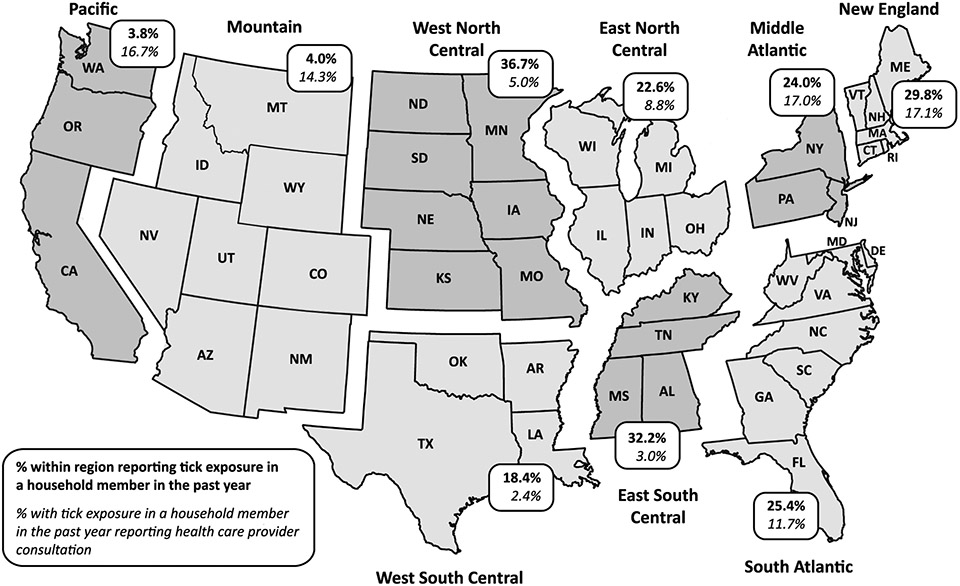

For this study, reported frequencies are unweighted and reported proportions are weighted. Geographic regions are those designated by the U.S. Census Bureau (Fig. 1). Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Analysis of 2009, 2011, and 2012 HealthStyles data was judged to be exempt from institutional review board requirements.

Fig. 1.

Tick exposure and health care seeking by region (2009).

Results

Survey response rates were 73% (4728/6504) in 2009, 69% (4050/5864) in 2011, and 80% (3503/4371) in 2012 (P < .0001). For all three samples combined, 51.6% of respondents were female and 68.1% were white. Median respondent age was 51 years. Most respondents had an annual household income ≥$50,000 (55.8%), had some college education or higher (61.4%), and were employed (59.8%). Demographic characteristics of respondents matched the CPS proportions for each year (see Appendix B).

In 2009, 934 (21.0%) of 4728 total respondents reported that a household member found a tick on his or her body during the previous year; of these, 109 (10.1%) reported that a health care provider was consulted as a result of finding a tick on a household member. Respondents living in the West North Central, East South Central, and New England regions more commonly reported tick exposure in the household (36.7%, 32.2%, and 29.8%, respectively) (Fig. 1). Of all respondents reporting tick exposure in the household, health care provider consultation was most common in the New England (17.1%), Mid-Atlantic (17.0%), and Pacific (16.7%) regions and least common in the West South Central (2.4%), East South Central (3.0%), and West North Central (5.0%) regions.

Sixty (1.3%) respondents in 2009 and 43 (0.9%) in 2012 reported having been diagnosed with LD at some time in their lives. The percentage was highest in both years among respondents in the New England (6.5% in 2009, 2.2% in 2012) and Mid-Atlantic (3.0% in 2009, 2.0% in 2012) regions. Among survey respondents in 2009 who reported past diagnoses with LD, the reported duration of antibiotic treatment was ≤4 weeks for 39.0% of respondents, 5–8 weeks for 20.3% of respondents, and >8 weeks for 35.6% of respondents. In the 2011 survey, respondents were asked about “chronic LD”; 17 (0.5%) said they had “chronic LD” and 516 (10.5%) said they knew someone else with “chronic LD.”

When asked which TBDs occur in the area where they live, respondents’ answers varied by disease and region (Table 2). Overall, 63.7% reported that LD occurs in the area where they live. Many respondents living in regions where LD is not known to occur, such as the East South Central, Mountain, and West South Central regions, reported that the disease occurs where they live (63.6%, 51.1%, and 49.4%, respectively). Overall, 20.2% of respondents reported that RMSF occurs in their area, with highest percentages in the Mountain (48.1%) and East South Central (38.3%) regions. In the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions, areas that have a high incidence of LD as well as anaplasmosis and babesiosis, 13.9% reported that no TBDs occur in their area and 20.8% said they had not heard of any of these diseases. Regardless of region or endemicity, few respondents reported that the following diseases occur where they live: anaplasmosis (0.9%), babesiosis (1.1%), ehrlichiosis (1.4%), STARI (2.4%), tick-borne relapsing fever (1.9%), or tularemia (1.0%).

Table 2.

Number of respondents who believe that the indicated TBD occurs in the area where they live (2009).

| Geographic region | LD n (% within region) |

RMSF n (% within region) |

None or “Have not heard of any of these TBDs”a n (% within region) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2943 (63.7) | 959 (20.2) | 1559 (31.6) |

| New England | 170 (86.1) | 18 (11.5) | 30 (13.9) |

| Mid-Atlantic | 502 (78.7) | 64 (7.6) | 146 (20.8) |

| East North Central | 552 (68.6) | 89 (10.9) | 234 (28.6) |

| West North Central | 242 (77.9) | 82 (20.6) | 70 (19.3) |

| South Atlantic | 597 (66.2) | 265 (28.3) | 289 (28.8) |

| East South Central | 206 (63.6) | 122 (38.3) | 109 (30.2) |

| West South Central | 242 (49.4) | 110 (25.8) | 236 (45.4) |

| Mountain | 157 (51.1) | 148 (48.1) | 116 (30.3) |

| Pacific | 275 (38.9) | 61 (9.5) | 329 (55.1) |

The TBDs listed in this survey question were Lyme disease, RMSF, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, STARI, tick-borne relapsing fever, and tularemia (Table 1).

The majority of respondents (51.2%) reported that they did not routinely take any personal prevention steps against tick bites during warm weather (Table 3). Tick check was the most commonly reported personal prevention practice, with highest levels reported in West North Central (47.9%), East South Central (43.7%), and New England (43.2%) regions. Use of repellent was reported by respondents most commonly in the West North Central (30.3%), East South Central (27.6%), and West South Central (26.5%) regions, and showering to prevent tick bites was reported most commonly in the East South Central (26.6%), South Atlantic (21.4%), and West North Central (20.5%) regions.

Table 3.

Use of prevention measures.

| Geographic region | Personal prevention measures (2011)a n (% within region) |

Yard-based pesticides (2009) n (% within region) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use repellent | Shower | Do tick checks | Other steps | Do nothing | Currently use | Would not use | |

| Overall | 826 (21.1) | 589 (15.7) | 1316 (30.6) | 312 (7.6) | 2066 (51.2) | 558 (10.7) | 446 (10.2) |

| New England | 53 (25.6) | 32 (15.1) | 103 (43.2) | 25 (13.1) | 64 (35.9) | 15 (7.2) | 21 (14.1) |

| Mid-Atlantic | 127 (26.1) | 92 (19.2) | 182 (30.7) | 49 (9.5) | 247 (45.4) | 58 (6.8) | 76 (10.5) |

| East North Central | 152 (23.7) | 81 (12.1) | 219 (29.0) | 44 (6.5) | 336 (51.9) | 60 (7.1) | 83 (10.1) |

| West North Central | 101 (30.3) | 65 (20.5) | 182 (47.9) | 31 (11.1) | 118 (32.2) | 39 (9.2) | 35 (10.8) |

| South Atlantic | 167 (21.3) | 147 (21.4) | 287 (38.0) | 50 (5.8) | 339 (44.8) | 136 (13.0) | 75 (9.2) |

| East South Central | 54 (27.6) | 49 (26.6) | 86 (43.7) | 25 (14.1) | 63 (34.2) | 50 (15.6) | 25 (7.0) |

| West South Central | 100 (26.5) | 69 (16.9) | 112 (26.5) | 37 (7.4) | 224 (52.6) | 113 (22.8) | 24 (5.9) |

| Mountain | 34 (12.2) | 18 (6.1) | 64 (23.3) | 14 (5.0) | 216 (64.8) | 24 (5.8) | 33 (9.8) |

| Pacific | 38 (5.9) | 36 (6.6) | 81 (12.0) | 37 (5.2) | 459 (76.1) | 63 (10.3) | 74 (14.6) |

Respondents could choose more than one response.

Regarding environmental prevention measures, 10.7% of respondents reported using chemical pesticides to reduce ticks on their properties (Table 3). Highest rates of chemical pesticide use were reported by respondents in the West South Central (22.8%), East South Central (15.6%), and South Atlantic (13.0%) regions. In contrast, 10.2% of respondents overall reported that they would not use chemical pesticides on their property; respondents from the New England (14.1%) and Pacific (14.6%) regions were more commonly averse to chemical pesticide use.

Discussion

Results from these surveys suggest that exposure to ticks is common and awareness of at least one tick-borne disease (LD) is widespread in the United States. Nevertheless, use of measures to prevent TBDs is relatively infrequent, and there appear to be important gaps regarding awareness of other, non-Lyme TBDs among the U.S. public.

Reported exposure to ticks in households exceeded 18% in nearly all areas except the Mountain and Pacific regions. In New England, our results are similar to the 28% exposure rate reported by Gould et al. (2008) for endemic areas of Connecticut. In both the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions, a substantial proportion of respondents reported seeking care after tick exposure, likely driven by awareness of greater LD risk in those areas. Interestingly, in other regions, the frequency of tick exposure appears to be inversely related to care seeking, perhaps as a result of desensitization to tick exposures in areas with an abundance of ticks. For example, respondents in the West North Central and East South Central regions reported high rates of tick exposure but the lowest proportion of seeking health care for tick exposure. The inverse was true the Mountain and Pacific regions. It should be noted, however, that consultation with a healthcare provider for tick bite alone is not generally recommended, as antibiotic prophylaxis for tick bite has been validated only for the prevention of Lyme disease in very specific circumstances (Wormser et al., 2006).

A surprisingly large proportion of respondents reported receiving more than 8 weeks of antibiotic treatment for LD. While we cannot verify this time frame or determine the type of treatment prescribed or the rationale of the respondents’ providers, it should be emphasized that for early LD, which comprises the majority of LD cases, there is no scientific evidence of clinical benefit from antibiotic treatment longer than current guidelines recommend (Kowalski et al., 2010; Wormser et al., 2003, 2006). Further, in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of LD, several controlled trials showed no benefit in prolonged antibiotic therapy (Klempner et al., 2001; Krupp et al., 2003). That many respondents reported receiving prolonged therapy is concordant with other reports of providers’ non-adherence to or unfamiliarity with LD treatment guidelines (Eppes et al., 1994; Kowalski et al., 2010; Magri et al., 2002). Antimicrobial treatment for longer than guidelines recommend occurs commonly with other conditions and is not an indication that longer treatment courses are medically justified (Bratzler et al., 2005; Hecker et al., 2003; Kahan et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2014). Our results indicate that providers in LD endemic areas may benefit from education regarding the duration of therapy needed, especially in light of the risk of antibiotic-related complications and development of resistance.

The level of awareness of LD was high in all regions, especially among respondents in the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions, which account for a large proportion of reported cases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). This observation should be tempered, however, by the fact that 51–64% of respondents living in the East South Central, West South Central, and Mountain regions with no or very low incidences of LD reported that it occurs where they live. This misunderstanding is likely a result of widespread misinformation common on the internet (Cooper and Feder, 2004) and may result in patient requests for inappropriate diagnostic tests and treatment in these regions (Perea et al., 2014). TBD education efforts for the public and providers should take care in emphasizing the highly focal nature of TBDs, highlighting which diseases occur where and noting the possibility of travel-related cases.

Respondents in regions where RMSF occurs were somewhat familiar with the disease, but there is opportunity to increase awareness considering that the disease can become rapidly fatal if not treated promptly. In contrast, awareness of less common TBDs (anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and ehrlichiosis) was low in all regions. Fortunately, since Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia microti, and Ehrlichia species Wisconsin are transmitted by the same Ixodes spp. ticks that transmit B. burgdorferi, those with awareness of LD who adopt prevention practices against these ticks will decrease their risk of acquiring other TBDs as well.

Despite the high numbers of tick exposures and high LD awareness reported by respondents in the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions, the proportion of respondents in these regions routinely practicing personal prevention methods is lower than what has been reported in the literature for highly endemic areas (Herrington et al., 1997; Phillips et al., 2001; Shadick et al., 1997). In addition, a lower proportion of respondents in these regions reported current use of chemical pesticides to reduce ticks on properties, and a high proportion reported that they would not consider using these pesticides when compared with other regions. However, the low levels of use of personal and environmental prevention measures reported in this study may be due to the inclusion of respondents who infrequently encounter tick habitat and therefore have little need to take precautions. Alternatively, it may suggest that even with adequate levels of knowledge and awareness, additional barriers exist among the public toward adopting prevention measures, such as knowledge of effectiveness, affordability, accessibility, and perceptions of risk (Gould et al., 2008). Future research should determine the specific reasons why people choose not to implement certain measures. Once these barriers are understood, intensive educational interventions promoting acceptable, validated methods may increase prevention practices among the public in areas of tick-borne disease risk (Daltroy et al., 2007).

Our findings are subject to several limitations. First, all data collected in the HealthStyles surveys were self-reported, may be subject to recall bias, and could not be independently validated. Second, reporting weighted proportions allows for better accuracy in terms of the representativeness of responses to the U.S. population; however, these weighted proportions are notably discrepant from the unweighted proportions (not reported) for survey questions with a small number of responses. Third, our results do not include data for persons under 18 years of age who account for a quarter of all reported LD cases. Fourth, the census regions used for our assessments do not coincide precisely with areas of endemicity for certain TBDs and do not allow for finer-scale evaluations of TBD risk in relation to reported prevention practices or disease awareness. Further, some of the survey questions are subject to variable interpretation. For example, for the question related to TBD occurrence, the phrase, “the area where you live,” could have been interpreted by respondents to mean their region, state, county, or municipality. For the survey questions on LD diagnoses, diagnosis requirements such as physician-diagnosed LD or laboratory evidence of infection were not defined. Further, the term “chronic LD” was not defined in the survey because it is in common usage among the public, particularly on the internet; it is typically used to describe a range of conditions which may or may not be associated with B. burgdorferi infection; and it currently has no agreed upon clinical definition (Marques, 2008). Finally, English language literacy is required to participate in HealthStyles surveys; therefore, some individuals with low literacy in English may have been underrepresented.

These limitations notwithstanding, the HealthStyles surveys had robust sample sizes, relatively high response rates, and used post-stratification weighting to ensure representativeness to the U.S. population. These findings serve as a baseline for future, annual use of HealthStyles surveys to evaluate TBD awareness, prevention practices, self-reported tick exposures, and LD diagnoses over time, increasing the validity and reliability of the current findings. In conclusion, results from the national HealthStyles surveys contribute to a more accurate picture of the overall burden of TBDs in the United States and highlight opportunities for targeted TBD health communications as well as the need to better understand barriers to use of prevention measures by the public.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Anna Perea, CDC, for creating Fig. 1; Alison Hinckley, CDC, for thoughtful review of the manuscript; and Sarah Lewis, CDC, for coordinating HealthStyles data. This project was conducted as part of routine research at CDC; as such, there are no specific funding sources to acknowledge.

Appendix

Appendix A. HealthStylesa sampling & data collection methodology, 2009, 2011, 2012

| Year | 2009 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling & data collection company | Synovate Inc. | GfK (Knowledge Panel) | GfK (Knowledge Panel) |

| Panel sampling methodology | Opt-in panel | Panel built using probability-based random sampling (using both random-digit dial and address-based methods) | Panel built using probability-based random sampling (using both random-digit dial and address-based methods) |

| Survey sampling methodology | Stratified random sampling based on region, household income, population density, age, and household size | Random sampling | Random sampling |

| Panel of potential respondentsb | Mail panel: ~328,000 panelists | Online panel: ~50,000 panelists | Online panel: ~50,000 panelists |

| Initial wave of consumer surveys |

ConsumerStyles Response rate: 49.4% (10,587/21,420) |

ConsumerStyles Response rate 55.5% (8110/14,598) |

Spring ConsumerStyles Response rate 57.8% (6728/11,636) |

| HealthStyles surveys (sent to a subsample of respondents who completed the initial wave) |

HealthStyles Version B By mail Sept.–Oct. 2009 Response rate: 72.7% (4728/6504) |

HealthStyles summer wave Online Jul.–Aug. 2011 Response rate: 69% (4050/5865) |

Fall ConsumerStyles Online Sept.–Oct. 2012 Response rate: 80% (3503/4371) |

| Respondent incentives | Cash and/or coupon cash worth ≤$10; respondent entered into sweepstakes to win cash prize (first place: $1000; second place (20 prizes): $50) | Cash equivalent reward points worth ≤$10; respondent entered into monthly sweepstakes to win in-kind prize worth ≤$500 | Cash equivalent reward points worth ≤$10; respondent entered into monthly sweepstakes to win in-kind prize worth ≤$500 |

| Weighting factors, designed to weight the data to match U.S. Current Population Survey (CPS) proportions | Gender, age, income, race, household size | Gender, age, income, race/ethnicity, household size, education, census region, metro status, and prior Internet access | Gender, age, income, race/ethnicity, household size, education, census region, metro status, and prior Internet access |

HealthStyles surveys are designed and conducted by Porter Novelli, a global social marketing and public relations firm (Washington, DC).

Respondents are recruited whether or not they have landline phones or Internet access, and, if needed, households are provided with a laptop computer and access to the Internet to complete the surveys.

Appendix B. Respondent demographics for 2009, 2011, and 2012 HealthStyles surveys

| Characteristic | HealthStyles 2009 |

HealthStyles 2011 |

HealthStyles 2012 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted no. | Weighted % | Unweighted no. | Weighted % | Unweighted no. | Weighted % | |

| Overall | 4728 | n/a | 4050 | n/a | 3503 | n/a |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2271 | 48.5 | 1971 | 48.5 | 1733 | 48.3 |

| Female | 2457 | 51.5 | 2079 | 51.5 | 1770 | 51.7 |

| Age in years | ||||||

| 18–34 | 532 | 30.5 | 734 | 29.9 | 735 | 29.8 |

| 35–54 | 2386 | 38.3 | 1678 | 36.6 | 1236 | 36.0 |

| 55–64 | 897 | 14.8 | 882 | 16.2 | 706 | 16.2 |

| ≥65 | 913 | 16.4 | 756 | 17.3 | 826 | 17.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 3050 | 68.9 | 3077 | 68.3 | 2641 | 67.0 |

| Black | 664 | 11.5 | 349 | 11.4 | 334 | 11.5 |

| Hispanic | 672 | 13.4 | 348 | 13.5 | 332 | 14.4 |

| Other | 342 | 6.2 | 276 | 6.8 | 196 | 7.1 |

| Education | ||||||

| HS or less | 1406 | 29.8 | 1259 | 43.3 | 1136 | 41.9 |

| Some college | 1761 | 37.5 | 1295 | 28.6 | 1065 | 29.0 |

| ≥Bachelor | 1522 | 31.8 | 1496 | 28.1 | 1302 | 29.1 |

| Not specified | 39 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Income | ||||||

| <$25,000 | 1180 | 24.8 | 695 | 18.6 | 567 | 19.0 |

| $25–$49,999 | 971 | 24.2 | 932 | 23.6 | 832 | 22.5 |

| $50–$74,999 | 811 | 18.8 | 804 | 21.3 | 706 | 21.6 |

| ≥ $75,000 | 1766 | 32.2 | 1619 | 36.6 | 1398 | 36.9 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 3087 | 67.5 | 2355 | 55.9 | 1985 | 56.1 |

| Not employed | 1606 | 31.8 | 1695 | 44.1 | 1518 | 43.9 |

| Not specified | 35 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Footnotes

Disclosures

This work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. government. The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Bratzler DW, Houck PM, Surgical Infection Prevention Guideline Writers, W., 2005. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Am. J. Surg 189, 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010. Summary of notifiable diseases – United States, 2008. MMWR 57, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. Summary of notifiable diseases, United States, 2012. MMWR 61, 653–684. [Google Scholar]

- Connally NP, Durante AJ, Yousey-Hindes KM, Meek JI, Nelson RS, Heimer R, 2009. Peridomestic Lyme disease prevention: results of a population-based case–control study. Am. J. Prev. Med 37, 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JD, Feder HM Jr., 2004. Inaccurate information about Lyme disease on the internet. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J 23, 1105–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran KL, Fish D, Piesman J, 1993. Reduction of nymphal Ixodes dammini (Acari: Ixodidae) in a residential suburban landscape by area application of insecticides. J. Med. Entomol 30, 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daltroy LH, Phillips C, Lew R, Wright E, Shadick NA, Liang MH, 2007. A controlled trial of a novel primary prevention program for Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses. Health Educ. Behav 34, 531–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppes SC, Klein JD, Caputo GM, Rose CD, 1994. Physician beliefs, attitudes, and approaches toward Lyme disease in an endemic area. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila) 33, 130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration, 2002. Manufacturer discontinues only Lyme disease vaccine. 0362–1332 (Print) 0362-1332 (Linking). [Google Scholar]

- Gould LH, Nelson RS, Griffith KS, Hayes EB, Piesman J, Mead PS, Cartter ML, 2008. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding Lyme disease prevention among connecticut residents, 1999–2004. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 8, 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker MT, Aron DC, Patel NP, Lehmann MK, Donskey CJ, 2003. Unnecessary use of antimicrobials in hospitalized patients: current patterns of misuse with an emphasis on the antianaerobic spectrum of activity. Arch. Intern. Med. 163, 972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington JE Jr., Campbell GL, Bailey RE, Cartter ML, Adams M, Frazier EL, Damrow TA, Gensheimer KF, 1997. Predisposing factors for individuals’ Lyme disease prevention practices: Connecticut, Maine, and Montana. Am. J. Public Health 87, 2035–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahan NR, Chinitz DP, Kahan E, 2004. Physician adherence to recommendations for duration of empiric antibiotic treatment for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: a national drug utilization analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 13, 239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A, Basket M, Sheedy K, 2011. Vaccine attitudes, concerns, and information sources reported by parents of young children: results from the 2009 HealthStyles survey. Pediatrics. 127 (Suppl. 1), S92–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempner MS, Hu LT, Evans J, Schmid CH, Johnson GM, Trevino RP, Norton D, Levy L, Wall D, Mccall J, Kosinski M, Weinstein A, 2001. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med 345, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobau R, Gilliam F, Thurman DJ, 2006. Prevalence of self-reported epilepsy or seizure disorder and its associations with self-reported depression and anxiety: results from the 2004 HealthStyles Survey. Epilepsia 47, 1915–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski TJ, Tata S, Berth W, Mathiason MA, Agger WA, 2010. Antibiotic treatment duration and long-term outcomes of patients with early Lyme disease from a Lyme disease-hyperendemic area. Clin. Infect. Dis 50, 512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause PJ, Narasimhan S, Wormser GP, Rollend L, Fikrig E, Lepore T, Barbour A, Fish D, 2013. Human Borrelia miyamotoi infection in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med 368, 291–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp LB, Hyman LG, Grimson R, Coyle PK, Melville P, Ahnn S, Dattwyler R, Chandler B, 2003. Study and treatment of post Lyme disease (STOP-LD): a randomized double masked clinical trial. Neurology 60, 1923–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Liu G, Thiboutot DM, Leslie DL, Kirby JS, 2014. A retrospective analysis of the duration of oral antibiotic therapy for the treatment of acne among adolescents: investigating practice gaps and potential cost-savings. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 71, 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magri JM, Johnson MT, Herring TA, Greenblatt JF, 2002. Lyme disease knowledge, beliefs, and practices of New Hampshire primary care physicians. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract 15, 277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques A, 2008. Chronic Lyme disease: a review. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am 22 (341–360), vii–viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcmullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, Macneil A, Goldsmith CS, Metcalfe MG, Batten BC, Albarino CG, Zaki SR, Rollin PE, Nicholson WL, Nichol ST, 2012. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N. Engl. J. Med 367, 834–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea AE, Hinckley AF, Mead PS, 2014. Tick bite prophylaxis: results from a 2012 survey of healthcare providers. Zoonoses Public Health, September 22. doi: 10.1111/zph.12159. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CB, Liang MH, Sangha O, Wright EA, Fossel AH, Lew RA, Fossel KK, Shadick NA, 2001. Lyme disease and preventive behaviors in residents of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. Am. J. Prev. Med 20, 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polen KN, Sandhu PK, Honein MA, Green KK, Berkowitz JM, Pace J, Rasmussen SA, 2015. Knowledge and attitudes of adults towards smoking in pregnancy: results from the HealthStyles(c) 2008 Survey. Matern. Child Health J 19 (1), 144–154, 10.1007/s10995-014-1505-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard WE, 2007. Evaluation of consumer panel survey data for public health communication planning: an analysis of annual survey data from 1995–2006. In: American Statistical Association 2007 Proceedings of the Section on Health Policy Statistics, pp. 1528–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Novelli Public Services, 2009a. ConsumerStyles 2009 Methodology; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Novelli Public Services, 2009b. Fall ConsumerStyles 2009 Survey. (Unpublished raw data). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Novelli Public Services, 2011a. ConsumerStyles 2011 Methodology; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Novelli Public Services, 2011b. Fall ConsumerStyles 2011 Survey. (Unpublished raw data). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Novelli Public Services, 2012a. ConsumerStyles 2012 Methodology; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Novelli Public Services, 2012b. Fall ConsumerStyles 2012 Survey. (Unpublished raw data). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Pritt BS, Sloan LM, Johnson DK, Munderloh UG, Paskewitz SM, Mcelroy KM, Mcfadden JD, Binnicker MJ, Neitzel DF, Liu G, Nicholson WL, Nelson CM, Franson JJ, Martin SA, Cunningham SA, Steward CR, Bogumill K, Bjorgaard ME, Davis JP, Mcquiston JH, Warshauer DM, Wilhelm MP, Patel R, Trivedi VA, Eremeeva ME, 2011. Emergence of a new pathogenic Ehrlichia species, Wisconsin and Minnesota, 2009. N. Engl. J. Med 365, 422–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze TL, Jordan RA, Vasvary LM, Chomsky MS, Shaw DC, Meddis MA, Taylor RC, Piesman J, 1994. Suppression of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs in a large residential community. J. Med. Entomol 31, 206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze TL, Jordan RA, Hung RW, 1995. Suppression of subadult Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) following removal of leaf litter. J. Med. Entomol 32, 730–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadick NA, Daltroy LH, Phillips CB, Liang US, Liang MH, 1997. Determinants of tick-avoidance behaviors in an endemic area for Lyme disease. Am. J. Prev. Med 13, 265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen AK, Mead PS, Beard CB, 2011. The Lyme disease vaccine – a public health perspective. Clin. Infect. Dis 52 (Suppl. 3), s247–s252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford III K, 2004. Tick Management Handbook. Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau, 2006. Current Population Survey Design and Methodology (Technical Paper 66).

- Wormser GP, Ramanathan R, Nowakowski J, Mckenna D, Holmgren D, Visintainer P, Dornbush R, Singh B, Nadelman RB, 2003. Duration of antibiotic therapy for early Lyme disease. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med 138, 697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormser GP, Masters E, Nowakowski J, Mckenna D, Holmgren D, Ma K, Ihde L, Cavaliere LF, Nadelman RB, 2005. Prospective clinical evaluation of patients from Missouri and New York with erythema migrans-like skin lesions. Clin. Infect. Dis 41, 958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere AC, Klempner MS, Krause PJ, Bakken JS, Strle F, Stanek G, Bockenstedt L, Fish D, Dumler JS, Nadelman RB, 2006. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis 43, 1089–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]