Abstract

Introduction

Very few population-based assessments of delirium have been performed to date. These have not assessed the implications of delirium after major surgical oncology procedures (MSOPs). We examined the temporal trends of delirium following 10 MSOPs, as well as patient and hospital delirium risk factors. Finally, we examined the effect of delirium on length of stay, inhospital mortality, and hospital charges.

Methods

We retrospectively identified patients who underwent prostatectomy, colectomy, cystectomy, mastectomy, gastrectomy, hysterectomy, nephrectomy, oophorectomy, lung resection, or pancreatectomy within the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2003–2013). We yielded a weighted estimate of 3 431 632 patients. Multivariable logistic regression (MLR) analyses identified the determinants of postoperative delirium, as well as the effect of delirium on length of stay, in-hospital mortality, and hospital charges.

Results

Between 2003 and 2013, annual delirium rate increased from 0.7 to 1.2% (+6.0%; p<0.001). Delirium rates were highest after cystectomy (predicted probability [PP] 3.1%) and pancreatectomy (PP 2.6%), and lowest after prostatectomy (PP 0.15%) and mastectomy (PP 0.13%). Advanced age (odds ratio [OR] 3.80), maleness (OR 1.38), and higher Charlson comorbidity index (OR 1.20), as well as postoperative complications represent risk factors for delirium after MSOPs. Delirium after MSOP was associated with prolonged length of stay (OR 3.00), higher mortality (OR 1.15), and increased in-hospital charges (OR 1.13).

Conclusions

No contemporary population-based assessments of delirium after MSOP have been reported. According to our findings, delirium after MSOP has a profound impact on patient outcomes that ranges from prolonged length of stay to higher mortality and increased in-hospital charges.

Introduction

Delirium, defined as an acute decline of cognition and attention, is a common and severe problem for hospitalized patients, especially in those who undergo surgical procedures. Institutional series demonstrated that delirium affects 10–31% of adult hospital admissions,1 and is possibly even more prevalent in surgical patients.2 Additionally, delirium predisposes to greater morbidity, prolonged length of stay, higher mortality, and increased in-hospital charges.3,4

Institutional data showed that the odds of developing postoperative delirium are dependent on several factors, such as pre-existing cognitive dysfunction or pre-existing comorbidities.5 Furthermore, others reported that incidence of delirium is variable according to patient characteristics and surgical procedures.5 For example, Lee et al6 found a 13.8% rate of delirium after cardiac surgery. Conversely, in a meta-analysis of 26 studies, Bruce et al7 observed a wide range of delirium rates after elective orthopedic surgery ranging from 3.6–28.3%. Unfortunately, the variability of postoperative delirium rates has not been examined in contemporary population-based studies. Specifically, no such study focused on delirium after major surgical oncology procedures (MSOPs). In consequence, neither its rates nor its consequences are known in the MSOP setting.

To address the lack of data focusing on delirium after MSOPs, we assessed delirium temporal trends after 10 MSOPs, namely prostatectomy, colectomy, cystectomy, mastectomy, gastrectomy, hysterectomy, nephrectomy, oophorectomy, lung resection, and pancreatectomy. Moreover, we examined risk factors predisposing to postoperative delirium, as well as its association with length of stay, in-hospital mortality, and hospital charges.

Methods

Study population

Ten MSOPs were selected to serve the study purpose:8,9 prostatectomy, colectomy, cystectomy, mastectomy, gastrectomy, hysterectomy, nephrectomy, oophorectomy, lung resection, and pancreatectomy. Analyses were restricted to cancer diagnoses only. All procedures and diagnoses were coded using the International Classification of Disease, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD–9–CM) (Supplementary Table 1).

Outcomes of interest

Administrative codes were used to identify delirium diagnosis as previously described,8 and were defined as the presence of one of nine ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes: alcohol withdrawal delirium (291.0), drug-induced delirium (292.81), presenile dementia with delirium (290.11), senile dementia with delirium (290.3), vascular dementia with delirium (290.41), subacute delirium (293.1), metabolic encephalopathy (348.31), toxic encephalopathy (349.82), or delirium not otherwise specified (293.0). Prolonged length of stay was defined as a hospitalization above the 75th percentile for each examined MSOPs. Increased in-hospital charges were defined as amounts above the 75th percentile for each of the 10 examined MSOPs.

Patient and hospital characteristics

Patient age, gender, race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African American, and others), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI),10–12 and insurance status (private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and other [self-pay]) were defined according to Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) information. Ten previously reported delirium risk factors,5,12–14 such as dementia, alcohol-induced mental disorder, mood disorder, non-organic disorder, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia disorder, alcohol dependence, drug dependence syndrome, non-dependent drug use, and drug-induced disorder, were tested in logistic regression models. Additional risk variables consisted of hospital region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West),15 hospital size (small, medium and large), and hospital teaching vs. non-teaching status. Teaching institutions had an American Medical Association-approved residency program, were a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals, or had a ratio of 0.25 or higher of full-time equivalent interns and residents to non-nursing home beds.16 Lastly, annual MSOP hospital volume (low, medium, and high), representing the number of MSOP performed at each participating institution during each study calendar year, was calculated independently for each of the 10 examined MSOPs.17 Patients were divided according to three equal hospital volume tertiles, categorized as low-, medium-, and high-volume centers.

Statistical analysis

Data distribution was adjusted according to the provided NIS population weights to render estimates more accurate nationally. All analyses were performed on the weighted population.

First, medians and interquartile ranges, as well as frequencies and proportions were reported for continuous (age and length of stay) and categorical variables (gender, race, insurance status, CCI, annual MSOP hospital volume, region, hospital size, teaching status, and rates of concomitant psychiatric diagnoses that are considered established delirium risk factors5,12–14), respectively. The statistical significance of differences in medians and proportions was evaluated with the Kruskal-Wallis and Chi-squared tests.

Second, temporal trend rates were analyzed by the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC), which uses the linear regression methodology.18

Third, five sets of separate multivariable logistic regression (MLR) models examined five specific endpoints: 1) the first set of MLR models tested patient and hospital determinants of delirium after MSOPs; 2) the second set of MLR models tested the effect of postoperative complications (Supplementary Table 1) on delirium rates after MSOPs; 3) the third set of MLR models tested the effect of delirium on rates of prolonged (≥75th percentile) length of stay; 4) the fourth set of MLR models tested the effect of delirium on rates of in-hospital mortality; and 5) the fifth set of MLR models tested the effect of delirium on rates of increased (≥75th percentile) in-hospital charges. Moreover, endpoints (3) and (5) were subsequently individually re-examined for each MSOP. Specifically, the effect of delirium on prolonged length of stay and the effect of delirium on increased inhospital charges were tested with a separate MLR for each of the 10 examined MSOPs.

Finally, to adjust for clustering within hospitals, all five multivariable analyses regression models were fitted with generalized estimating equations.19 Analyses were performed using the R software environment for statistical computing and graphics (version 3.3.0; http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

General characteristics of the study populations

From 2003–2013, a weighted estimate of 3 431 632 patients underwent one of the 10 examined MSOP. Overall, 1% of patients were discharged with the diagnosis of delirium. Patients with delirium were more frequently older (75 vs. 64 years), male (55.9 vs 44.5%), Caucasian (69.1 vs. 62.8%), Medicare-insured (78.3 vs. 46%), and exhibited higher CCI (CCI ≥2: 23.8 vs. 11.2%) than controls. Non-teaching hospital status (43.1 vs. 41.5%) and lowest hospital surgical volume tertile accounted for higher rates of delirium (35.2 vs. 32.5%). Moreover, length of stay was longer (10 vs. 4 days), when delirium was diagnosed (Table 1). The proportion of patients with CCI ≥1 increased from 33.8 to 39.8% (EAPC +1.7%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.41–2.03; p<0.0001) during the study period.

Table 1.

Weighted descriptive characteristics of 3 431 632 patients older than 18 years undergoing major surgical oncology procedure, nationwide inpatient sample, 2003–2013

| Variables | Overall (%) | Without delirium (%) | With delirium (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted no. (%) of patients | 3 431 632 (100.0) | 3 398 637 (99.04) | 32 994 (0.96) |

| Age at surgery, median (IQR) | 64 (56–73) | 64 (56–73) | 75 (67–81) |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–7) | 10 (7–16) |

| Year of surgery | |||

| 2003–2008 | 61.2 | 61.3 | 51.7 |

| 2009–2013 | 38.8 | 38.7 | 48.3 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 55.4 | 55.5 | 44.1 |

| Male | 44.6 | 44.5 | 55.9 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 62.9 | 62.8 | 69.1 |

| African American | 8 | 8 | 6.3 |

| Non-Caucasian | 29.1 | 29.2 | 24.7 |

| CCI | |||

| 0 | 63.6 | 63.8 | 44.8 |

| 1 | 25 | 25 | 31.3 |

| ≥2 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 23.8 |

| Hospital teaching status | |||

| Non-teaching | 41.5 | 41.5 | 43.1 |

| Teaching | 58.5 | 58.5 | 56.9 |

| Annual MSOP hospital volume | |||

| Low | 32.5 | 32.5 | 35.2 |

| Medium | 33.8 | 33.8 | 34.8 |

| High | 33.7 | 33.7 | 30.0 |

| Hospital region | |||

| South | 35.6 | 35.6 | 34 |

| Midwest | 23.5 | 23.5 | 26.9 |

| Northeast | 21.6 | 21.6 | 20.8 |

| West | 19.3 | 19.3 | 18.2 |

| Insurance status | |||

| Private | 44.1 | 44.4 | 16.2 |

| Medicaid | 4.8 | 4.9 | 3.3 |

| Medicare | 46.3 | 46 | 78.3 |

| Other | 4.7 | 4.8 | 2.3 |

| Hospital size | |||

| Large | 68.4 | 68.4 | 69.6 |

| Medium | 21.5 | 21.5 | 20.8 |

| Small | 10.1 | 0.1 | 10.1 |

| MSOP | |||

| Prostatectomy | 19.8 | 20 | 2.8 |

| Colectomy | 18.8 | 18.7 | 33 |

| Cystectomy | 2.6 | 2.6 | 8.5 |

| Gastrectomy | 2.2 | 2.2 | 5.3 |

| Hysterectomy | 15.5 | 15.6 | 7.2 |

| Mastectomy | 15.6 | 15.7 | 2.1 |

| Nephrectomy | 11 | 11 | 12.6 |

| Oophorectomy | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| Pancreatectomy | 2 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Lung resection | 10.3 | 10.2 | 21.4 |

| Concomitant psychiatric diagnoses | |||

| Dementia | 0.1 | 0.04 | 1.9 |

| Alcohol induced mental disorder | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Mood disorder | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 |

| Non-organic disorder | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Anxiety disorder | 5 | 5 | 7.2 |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Schizophrenia disorder | 0.5 | 0.4 | 7.1 |

| Drug dependence syndrome | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Non-dependent drug use | 10.4 | 10.3 | 12.6 |

| Drug-induced disorder | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 |

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; IQR: interquartile rage; MSOP: major surgical oncology procedures.

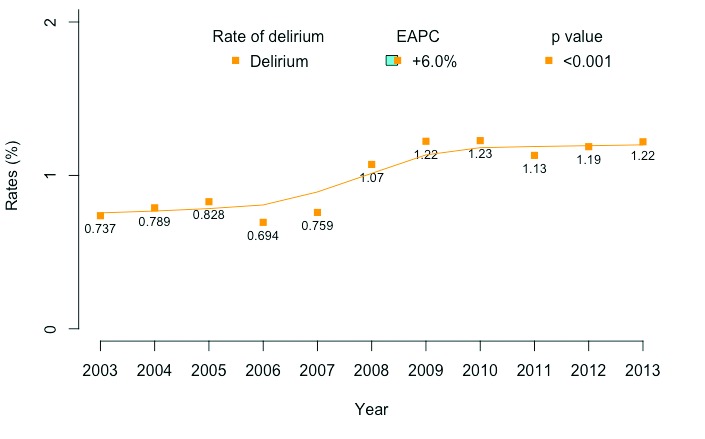

Temporal trend analyses

From 2003–2013, the annual delirium rate increased from 0.7 to 1.2% (EAPC +6.0%; CI +3.6 to +8.5; p<0.001) (Fig. 1). Within individual MSOPs, colectomy (EAPC +7.2%) and pancreatectomy (EAPC +6.5%) exhibited the highest increase in the annual rate of delirium compared to prostatectomy (EAPC −1.68), which exhibited the lowest rate (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overall delirium frequency following major surgical oncology procedures (MSOPs) in 3 431 632 patients, Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2003–2013.

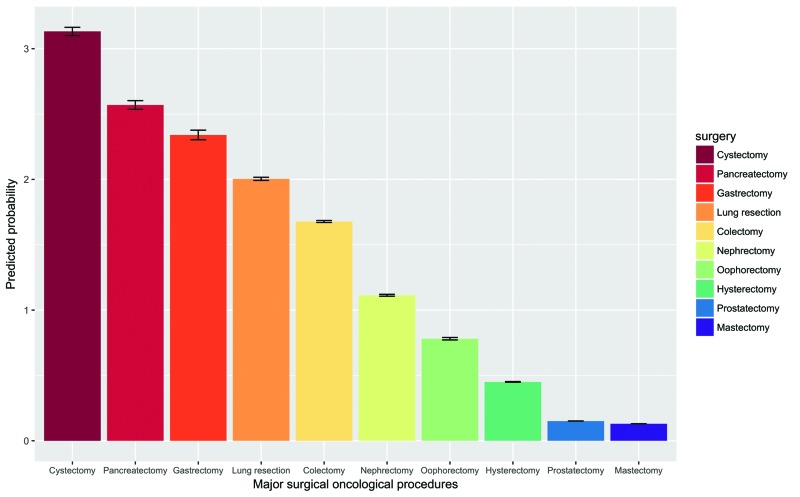

Multivariable logistic regression models testing for patient and hospital determinants of delirium after MSOPs

According to multivariable predicted probability (PP) of delirium after MSOPs (Fig. 2), the highest rate was recorded after cystectomy (PP 3.1%; standard deviation [SD] 0.03), followed by pancreatectomy (PP 2.6%; SD 0.03) and gastrectomy (PP 2.3%; SD 0.04). The lowest rates of postoperative delirium were recorded after prostatectomy (PP 0.15%; SD 0.001) and mastectomy (PP 0.13%; SD 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Model-adjusted probability of a delirium event according to major surgical oncology procedures (MSOPs). Predicted probabilities are derived from multivariable logistic regression models that adjusted for patient demographics (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, Charlson comorbidity index and insurance status), and hospital characteristics (i.e., hospital size, location, length of stay, teaching status, region, and hospital MSOP volume), as well as for patients neurologic disorder (dementia, alcohol induced mental disorder, mood disorder, non-organic disorder, anxiety disorder, alcohol dependence, schizophrenia disorder, drug dependence syndrome, non-dependent drug use, and drug-induced disorder).

Patient risk factors associated with delirium after MSOPs were older age (55–64 years odds ratio [OR] 1.90; p<0.0001; ≥65 years OR 3.80; p<0.0001) and male gender (OR 1.38; p<0.0001). CCI score ≥1 (1 OR 1.07; p=0.03; ≥2 OR 1.20; p<0.001) resulted in a marginal increase. Medicaid (OR 1.21; p=0.02) and Medicare (OR 1.58; p<0.0001) insurance status also increased the delirium rates relative to private insurance status. Finally, African American (OR 0.82; p=0.0002) and non-Caucasian race (OR 0.88; p=0.0001) were associated with lower delirium rates after MSOPs relative to Caucasian patients.

Of 10 established delirium risk factors, seven achieved independent predictor status (Supplementary Table 2): dementia (OR 24.07; p<0.0001), alcohol dependence (OR 14.51; p<0.0001), drug-induced disorder (OR 4.81; p<0.0001), mood disorder (OR 2.43; p<0.0001), drug dependence syndrome (OR 1.70; p=0.02), anxiety disorder (OR 1.53; p<0.0001), and non-dependent drugs use (OR 1.11; p=0.01).

Multivariable logistic regression models testing the effect of any postoperative complications on delirium after MSOPs

According to presence or absence of delirium after MSOPs, complication rates ranged as follows: intraoperative (3.3 vs. 1.7%), respiratory (38.7 vs. 9.8%), neurological (1.5 vs. 0.7%), infectious (14.7 vs. 2.6%), vascular (7.8 vs. 2.1%), gastrointestinal (27.0 vs. 11.2%), cardiac (17.0 vs. 5.8%), genitourinary (10.9 vs. 5.5%), wound (10.0 vs. 2.4%), and other (33.2 vs. 10.1%). Of 10 examined postoperative complications, seven achieved independent predictor status (Table 2): respiratory (OR 1.92; p<0.0001), other (OR 1.51; p<0.0001), neurological (OR 1.46; p=0.0005), infectious (OR 1.36; p<0.0001), vascular (OR 1.27; p<0.0001), gastrointestinal (OR 1.14; p<0.0001), and cardiac (OR 1.10; p=0.008). According to presence or absence of delirium after MSOPs, post-MSOPs transfusion rates were 28.7 vs. 11.5%, respectively. Postoperative transfusions (OR 1.33; p<0.0001) also increased the delirium rate.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression for predicting delirium according to in-hospital complications within 3 431 632 major surgical oncology procedure (MSOP) patients, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2003–2013

| Complications | OR | CI 2.50% | CI 97.50% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | 1.92 | 1.80 | 2.04 | <0.0001 |

| Other | 1.51 | 1.42 | 1.60 | <0.0001 |

| Neurological | 1.46 | 1.18 | 1.80 | 0.0005 |

| Infectious | 1.36 | 1.22 | 1.51 | <0.0001 |

| Transfusions | 1.33 | 1.25 | 1.41 | <0.0001 |

| Vascular | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.40 | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.14 | 1.07 | 1.22 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.18 | 0.008 |

| Intraoperative | 1.10 | 0.96 | 1.28 | 0.2 |

| Genitourinary | 1.06 | 0.97 | 1.16 | 0.2 |

| Wound infections | 1.01 | 0.90 | 1.14 | 0.8 |

Analysis was adjusted for type of surgery, length of stay, age, gender, race, type of procedure, year of surgery, region of the hospital, teaching status, hospital size, annual MSOP hospital volume, Charlson comorbidity index, and insurance status. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Multivariable logistic regression models testing the effect of delirium on prolonged (≥75th percentile) length of stay

Stratification according to presence or absence of delirium after MSOPs was associated with prolonged (≥75th percentile) length of stay (OR 3.00; 95% CI 2.75–3.24; p<0.0001). In all 10 MSOP-specific models examining the length of stay above the 75th percentile, delirium achieved independent predictor status (Table 3): mastectomy (OR 11.34; p<0.0001), prostatectomy (OR 10.45; p<0.0001), hysterectomy (OR 5.99; p<0.0001), nephrectomy (OR 4.54; p<0.0001), oophorectomy (OR 3.54; p<0.0001), lung resection (OR 2.55; p<0.0001), cystectomy (OR 2.03; p<0.0001), gastrectomy (OR 1.88; p<0.0001), colectomy (OR 1.86; p<0.0001), and pancreatectomy (OR 1.84; p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression models, after fitting for age, gender, race, type of procedure, year of surgery, region of the hospital, teaching status, annual MSOP hospital volume, hospital size, Charlson comorbidity index, insurance status, and complications, for predicting the effect of delirium on elevated length of stay (≥75th percentile) in 3 431 632 MSOP patients, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2003–2013

| Procedure-specific effect of delirium on length of stay higher than the 75th percentile | OR | CI 2.50% | CI 97.50% | p | Overall median length of stay, days (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mastectomy | 11.34 | 8.26 | 16.04 | <0.0001 | 2 (1–2) |

| Prostatectomy | 10.45 | 8.13 | 13.57 | <0.0001 | 2 (1–3) |

| Hysterectomy | 5.99 | 5.35 | 6.73 | <0.0001 | 3 (2–5) |

| Nephrectomy | 4.54 | 4.19 | 4.92 | <0.0001 | 4 (3–6) |

| Oophorectomy | 3.54 | 2.83 | 4.42 | <0.0001 | 4 (2–7) |

| Lung resection | 2.55 | 2.41 | 2.69 | <0.0001 | 6 (4–9) |

| Cystectomy | 2.03 | 1.85 | 2.23 | <0.0001 | 8 (7–11) |

| Gastrectomy | 1.88 | 1.67 | 2.11 | <0.0001 | 10 (8–16) |

| Colectomy | 1.86 | 1.78 | 1.95 | <0.0001 | 7 (5–11) |

| Pancreatectomy | 1.84 | 1.64 | 2.06 | <0.0001 | 10 (7–16) |

CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range; OR: odds ratio,

Multivariable logistic regression models testing the effect of delirium on in-hospital mortality

Overall, 1.1% of MSOP patients died during hospitalization. Stratification according to presence or absence of delirium after MSOPs was associated with higher (6 vs. 1%; p<0.0001) rate of in-hospital mortality. Moreover, delirium after MSOPs was associated with 1.15-fold (OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.10–1.21; p<0.0001) mortality rate increase. Low absolute mortality rates after individual MSOPs (ranging from 0.13–3.2%) prevented the reporting of multivariable MSOPspecific mortality rates after delirium.

Multivariable logistic regression models testing the effect of delirium on increased (≥75th percentile) in-hospital charges

Stratification according to presence or absence of delirium after MSOPs was associated with increased (≥75th percentile) in-hospital charges (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.05–1.21; p=0.001). In all 10 MSOP-specific models examining the hospital charges above the 75th percentile, delirium achieved independent predictor status (Table 4): prostatectomy (OR 2.04; p<0.0001), lung resection (OR 2.02; p<0.0001), oophorectomy (OR 1.99; p<0.0001), cystectomy (OR 1.86; p<0.0001), hysterectomy (OR 1.74; p<0.0001), nephrectomy (OR 1.74; p<0.0001), gastrectomy (OR 1.73; p<0.0001), pancreatectomy (OR 1.64; p<0.0001), colectomy (OR 1.59; p<0.0001), and mastectomy (OR 1.49; p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression models, after fitting for age, gender, race, type of procedure, year of surgery, region of the hospital, teaching status, Annual MSOP hospital volume, hospital size, Charlson comorbidity index, insurance status and complications, for predicting the effect of delirium on increased in-hospital charges (≥75th percentile) in 3 431 632 MSOP patients, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2003–2013

| Procedure specific effect of delirium on hospital charges higher than the 75th percentile | OR | CI 2.50% | CI 97.50% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostatectomy | 2.04 | 1.76 | 2.36 | <0.0001 |

| Lung resection | 2.02 | 1.91 | 2.13 | <0.0001 |

| Oophorectomy | 1.99 | 1.63 | 2.42 | <0.0001 |

| Cystectomy | 1.86 | 1.70 | 2.03 | <0.0001 |

| Hysterectomy | 1.77 | 1.61 | 1.95 | <0.0001 |

| Nephrectomy | 1.74 | 1.62 | 1.87 | <0.0001 |

| Gastrectomy | 1.73 | 1.54 | 1.94 | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatectomy | 1.64 | 1.46 | 1.84 | <0.0001 |

| Colectomy | 1.59 | 1.52 | 1.66 | <0.0001 |

| Mastectomy | 1.49 | 1.23 | 1.80 | <0.0001 |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Discussion

Postoperative delirium is a multifaceted problem that is associated with poor perioperative outcomes, increased long-term adverse sequelae, and a significant cost burden.18 To date, several single and multi-institutional series have assessed the rate of delirium and its implication on patient outcomes. Nonetheless, contemporary population-based assessments of delirium using large administrative databases are lacking. Based on these considerations, we sought to examine population-level trends in delirium following MSOP. To accomplish this task, we relied on the NIS database, including patients who underwent one of 10 MSOPs. Our study yielded several noteworthy findings.

First, our population-based analyses revealed a rate of delirium after MSOPs of 1%. This finding contrasts with the postoperative delirium incidence currently reported in the literature, ranging from 4% for minor procedures, to 35–65% for major procedures.12 It should be noted that delirium rates may be captured less frequently than other comorbidities, such as infection,20 venous thromboembolism,21 or common postoperative complications.8 Moreover, delirium may go unnoticed in older patients with other comorbidities that are given greater importance in the acute care setting, such as after MSOPs. Last but not least, delirium may go unnoticed because of absence of associated symptoms. In that regard, Lipowski et al22 distinguished between hypoactive (quiet) and hyperactive variants of delirium. Patients with active delirium are easily identifiable. Conversely, individuals with hypoactive variant, which accounts for 75% of cases, may permanently go unnoticed.23 In consequence, prospective studies that a priori include delirium among outcomes of interest may contrast with population-based analyses, where delirium rates may be under-reported.

Second, we identified an increase in delirium rates after MSOP over time. Several factors may explain this phenomenon. For example, increasing comorbidities of patients undergoing MSOP may have contributed to these findings. Indeed, we found that the annual rate of CCI ≥1 increased by 1.7% (95% CI 1.41–2.03; p<0.0001) during the study period.

Third, to the best of our knowledge, we are first to report delirium rates after specific MSOPs. Here, cystectomy (3.2%), pancreatectomy (2.6%), and gastrectomy (2.4%) demonstrated the highest rates of delirium. Conversely, two procedures, namely prostatectomy (0.14%) and mastectomy (0.13%), were associated with significantly lower rates than average (1%). These rates suggest a relationship between post-MSOP delirium and the complexity of the surgical procedures. For example, cystectomy and pancreatectomy are associated with longer operative times and higher use of analgesia. Both procedures respectively represent the first highest and the second highest, when delirium rates are considered.

Fourth, analyses of established delirium risk factors validated our findings. Specifically, well-known12,24 delirium risk factors, such as dementia (OR 24.07), alcohol dependence (OR 14.51), and mood disorder (2.43) all strongly and significantly increased delirium rates after MSOPs. Moreover, drug-induced disorder, anxiety disorder, and drug dependence syndrome were also strongly associated with delirium, which is often reported in patients treated with opioids, benzodiazepines, and sedatives.14

Fifth, to the best of our knowledge, we are first to examine the association between delirium after MSOPs and specific complications. Of 10 examined postoperative complications, seven achieved independent predictor status. Specifically, respiratory, other, neurological, infectious, vascular, gastrointestinal, and cardiac complications were associated with higher rates of post-MSOP delirium. To the best of our knowledge, we are also first to report that postoperative transfusions were associated with increased rate of delirium (OR 1.33). This result is worrisome since approximately 30% of MSOP patients require a transfusion during hospital stay.25

Sixth, our findings suggest that length of stay is longer in patients experiencing delirium after MSOPs. Based on our observations, the effect of delirium on length of stay above the 75th percentile is strongest for MSOPs with short length of stay. Conversely, MSOP-specific delirium rates are weakest for MSOPs with long length of stay. For example, after prostatectomy (median length of stay two days) and mastectomy (median length of stay two days), the effect of delirium was 10-fold higher. Conversely, after cystectomy (median length of stay eight days) or colectomy (median length of stay seven days), the effect of delirium was only two-fold higher. These observations contrast with the absolute risk of delirium. The latter is lowest for procedures with shortened length of stay and highest for procedures with prolonged length of stay. We also observed a similar relationship between delirium and increased in-hospital charges.

We are also first to report a relationship between delirium and higher in-hospital mortality after MSOPs. Overall, patients who experienced delirium had a 15% increase of inhospital mortality compared to those without delirium. These findings are worrisome, and they should motivate physicians toward increased delirium monitoring in patients treated with one of the 10 MSOPs.

Finally, from a stricter urological point of view, it can be postulated that this analysis may be of interest for urologists who are dealing with complex patients with multiple urological and non-urological issues and who may benefit from a multidisciplinary evaluation. Indeed in today’s medical climate, surgical indications are evolving towards more aggressive behavior, including radical surgery in advanced urological malignancies26 and metastasectomy in oligometatstaic cancers.27 In this scenario, urologists must be aware of possible complications surrounding MSOPs in order to reduce and possibly prevent these in their patients.9,17 While our data emphasized that postoperative delirium is still a relatively frequent event in our daily practice, it should be noted that it might be prevented by following an evidence-based approach.

Our study is not devoid of limitations, which apply to all studies with retrospective designs. Additionally, our study was unable to adjust for tumor characteristics, and longitudinal data was also unavailable. Moreover, we were unable to control for some risk factors, such as laboratory values and baseline cognitive impairment. Finally, the NIS database does not specify delirium type (hyperactive vs. hypoactive), which could not be determined. Despite these limitations, we were able to provide some new insight on the importance of delirium after MSOPs.

Conclusions

No contemporary population-based assessments of delirium after MSOP have been reported. According to our findings, delirium after MSOP has a profound impact on patient outcomes that ranges from prolonged length of stay to higher mortality and increased in-hospital charges.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

Nationwide inpatient sample codes for major surgical oncological procedure (MSOP) and complications

| MSOP | Codes |

|---|---|

| Cystectomy | “576”,“577”,“688” |

| Pancreatectomy | “604”,“605”,“6062” |

| Lung resection | “3220”,“3229”,“323”,“324”,“325”,“326”,“329” |

| Gastrectomy | “435”,“436”,“437”,“438”,“439” |

| Prostatectomy | “525”,“526”,“527” |

| Nephrectomy | “554”,“5551”,“5552”,“5554” |

| Hysterectomy | “683”,“684”,“685”,“686”,“687”,“688”,“689” |

| Oophorectomy | “653”,“654”,“655”,“656” |

| Mastectomy | “8521”,“8522”,“8523”,“854” |

| Colectomy | “457”,“458”,“484”,“485”,“486”,“173” |

|

| |

| Complications | Codes |

|

| |

| Intraoperative | “9982” |

| Cardiac | “4100”,“4101”,“4102”,“4103”,“4104”,“4105”,“4106”,“4107”,“4108”,“4109”,“4110”,“4111”,“41181”,“41189”,“40201”,“40211”,“40291”,“4280”,“4281”,“42821”,“42831”,“42841”,“4289”,“4275”,“9971” |

| Respiratory | “5180”,“5184”,“5185”,“5187”,“51881”,“514”,“4660”,“46611”,“46619”,“4800”,“4801”,“4802”,“4803”,“4808”,“4809”,“481”,“4820”,“4821”,“4822”,“4823”,“4824”,“4828”,“4829”,“5070”,“51881”,“4830”,“4831”,“4838”,“485”,“486”,“7991”,“9973” |

| Genitourinary |

Diagnoses: “59010”,“59011”,“5902”,“59080”,“59081”,“5909”,“591”,“5933”,“5934”,“5935”,“59381”,“59382”,“59589”,“5961”,“5962”,“5966”,“9975”,“604”,“5991”,“7882”,“9963”,“5950”,“5970”, Procedures: “5501”,“5502”,“5503”,“5512”,“5593”,“5594”,“9761”,“9762”,“561”,“5641”,“5673”,“5674”,“5675”,“5681”,“5682”,“5683”,“5684”,“5685”,“5686”,“5689”,“5691”,“598” |

| Gastrointestinal | “5310”,“5311”,“5312”,“5313”,“5320”,“5321”,“5322”,“5323”,“5400”,“5401”,“5409”,“5600”,“5601”,“5602”,“5603”,“5608”,“5609”,“7876”,“9974”,“5692”,“5693”,“5695”,“5696”,“5793”,“00845” |

| Neurologic | “9970”,“99700”,“99701”,“99702”,“99709”,“436”,“951”,“952”,“953”,“954”,“955”,“956”,“3446”,“3530”,“354”,“355”,“7234” |

| Infection | “53641”,“51901”,“9985”,“993”,“038”,“0545”,“7907”,“99591”,“99592” |

| Vascular | “4151”,“41511”,“41512”,“41519”,“451”,“4510”,“4511”,“4512”,“4518”,“4519”,“4531”,“4534”,“45340”,“45341”,“45342”,“4538”,“4539”,“9972”,“9992”,“44422 “,“44481”,“44489”,“433”,“4330”,“4331”,“4332”,“4333”,“4338”,“4339”,“434”,“4340”,“4341”,“4349”,“436”,“437”,“4371”,“4372”,“4374”,“4373”,“4375”,“4376”,“4377”,“4378”,“4379”,“430”,“431”,“435”,“4599”,“4442”,“4448”,“9977” |

| Wound infection | “9983”,“99830”,“99831”,“99832”,“99833”,“9985”,“99859”,“99851”,“9986”,“567” |

| Other | “0418”,“2768”,“4589”,“584”,“7823”,“7824”,“7855”,“9950”,“9954”,“9994”,“9996”,“9997”,“9984”,“9987”,“9988”,“9989”,“53640”,“53642”,“53649”,“5793”,“99586” |

| Transfusion | “9902”,“9904”,“9900”,“9904”,“9902”, 9900” |

Delirium frequency of 3 431 632 patients underwent one of the 10 examined major surgical oncology procedures (MSOPs), Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2003–2013.

Supplementary Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression predicting delirium in 3 431 632 patients underwent one of 10 major surgical oncology procedures, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2003–2013

| Predictors of delirium | OR | CI 2.50% | CI 97.50% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystectomy | 9.25 | 7.73 | 11.07 | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatectomy | 7.03 | 5.73 | 8.62 | <0.0001 |

| Lung resection | 6.85 | 5.79 | 8.10 | <0.0001 |

| Gastrectomy | 6.33 | 5.17 | 7.74 | <0.0001 |

| Colectomy | 6.06 | 5.14 | 7.14 | <0.0001 |

| Nephrectomy | 5.64 | 4.76 | 6.67 | <0.0001 |

| Oophorectomy | 4.98 | 3.90 | 6.37 | <0.0001 |

| Hysterectomy | 3.50 | 2.89 | 4.23 | <0.0001 |

| Mastectomy | 1.15 | 0.91 | 1.45 | 0.2 |

| Length of stay | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.05 | <0.0001 |

| Teaching hospital (ref. non-teaching) | 1.01 | 0.95 | 1.08 | 0.7 |

| Annual MSOP hospital volume low (ref. high) | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.08 | 0.9 |

| Medium | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.11 | 0.4 |

| Hospital size small (ref. large) | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.07 | 0.5 |

| Medium | 0.96 | 0.89 | 1.02 | 0.2 |

| 2009–2013 (ref. 2003–2008) | 1.43 | 1.35 | 1.52 | <0.0001 |

| Age 55–64 (Ref. <55) | 1.90 | 1.67 | 2.16 | <0.0001 |

| Age ≥65 | 3.80 | 3.32 | 4.35 | <0.0001 |

| Male (Ref. female) | 1.38 | 1.30 | 1.46 | <0.0001 |

| African American (Ref. Caucasian) | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.0002 |

| Non-Caucasian | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.0001 |

| Charlson 1 (Ref. Charlson 0) | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.13 | 0.03 |

| Charlson ≥2 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.29 | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid (Ref. private ins) | 1.21 | 1.03 | 1.42 | 0.02 |

| Medicare | 1.58 | 1.44 | 1.73 | <0.0001 |

| Other | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.15 | 0.7 |

| Midwest (Ref. South) | 1.27 | 1.18 | 1.36 | <0.0001 |

| Northeast | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 0.5 |

| West | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.008 |

| Dementia | 24.07 | 18.77 | 30.88 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol induced mental disorder | 0.90 | 0.65 | 1.25 | 0.5 |

| Mood disorder | 2.43 | 2.02 | 2.93 | <0.0001 |

| Non-organic disorder | 1.23 | 0.90 | 1.68 | 0.2 |

| Anxiety disorder | 1.53 | 1.39 | 1.69 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol dependence | 14.51 | 12.68 | 16.62 | <0.0001 |

| Schizophrenia disorder | 0.92 | 0.61 | 1.37 | 0.7 |

| Drug dependence syndrome | 1.70 | 1.09 | 2.67 | 0.02 |

| Non-dependent drug use | 1.11 | 1.02 | 1.20 | 0.01 |

| Drug-induced disorder | 4.81 | 3.65 | 6.33 | <0.0001 |

CI: confidence interval; MSOP: major surgical oncology procedures; OR: odds ratio.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Saad has been an advisory board member for and has received payment/honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, and Sanofi; and has participated in clinical trials supported by Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, and Sanofi. The remaining authors report no competing financial or personal interests related to this work.

This paper has been peer-reviewed

References

- 1.Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: A systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35:350–64. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raats JW, van Eijsden WA, Crolla RMPH, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for postoperative delirium after major surgery in elderly patients. PloS One. 2015;10:e0136071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie DL, Zhang Y, Bogardus ST, et al. Consequences of preventing delirium in hospitalized older adults on nursing home costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:405–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leslie DL, Zhang Y, Holford TR, et al. Premature death associated with delirium at 1-year followup. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1657–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson TN, Raeburn CD, Tran ZV, et al. Postoperative delirium in the elderly: Risk factors and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2009;249:173–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee A, Mu JL, Joynt GM, et al. Risk prediction models for delirium in the intensive care unit after cardiac surgery: A systematic review and independent external validation. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:391–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce AJ, Ritchie CW, Blizard R, et al. The incidence of delirium associated with orthopedic surgery: A meta-analytic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19:197–214. doi: 10.1017/S104161020600425X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan H-J, Saliba D, Kwan L, et al. Burden of geriatric events among older adults undergoing major cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1231–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nazzani S, Preisser F, Mazzone E, et al. In-hospital length of stay after major surgical oncological procedures. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:969–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER. Review articles: Postoperative delirium: Acute change with long-term implications. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1202–11. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litaker D, Locala J, Franco K, et al. Preoperative risk factors for postoperative delirium. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:84–9. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(01)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin RY, Heacock LC, Fogel JF. Drug-induced, dementia-associated, and non-dementia, non-drug delirium hospitalizations in the United States, 1998–2005: An analysis of the national inpatient sample. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:51–61. doi: 10.2165/11531060-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed Dec. 15, 2017]. Available at: https://www.census.gov/en.html.

- 16.NIS Description of Data Elements. [Accessed July 21, 2017]. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp.

- 17.Nazzani S, Bandini M, Preisser F, et al. Postoperative paralytic ileus after major oncological procedures in the enhanced recovery after surgery era: A population-based analysis. Surg Oncol. 2019;28:201–7. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghani KR, Sammon JD, Karakiewicz PI, et al. Trends in surgery for upper urinary tract calculi in the USA using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample: 1999–2009. BJU Int. 2013;112:224–30. doi: 10.1111/bju.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panageas KS, Schrag D, Riedel E, et al. The effect of clustering of outcomes on the association of procedure volume and surgical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:658–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-8-200310210-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sammon JD, Klett DE, Sood A, et al. Sepsis after major cancer surgery. J Surg Res. 2015;193:788–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trinh VQ, Karakiewicz PI, Sammon J, et al. Venous thromboembolism after major cancer surgery: Temporal trends and patterns of care. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:43–9. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipowski ZJ. Transient cognitive disorders (delirium, acute confusional states) in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:1426–36. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.11.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcantonio E, Ta T, Duthie E, et al. Delirium severity and psychomotor types: Their relationship with outcomes after hip fracture repair. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:850–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grover S, Ghormode D, Ghosh A, et al. Risk factors for delirium and inpatient mortality with delirium. J Postgrad Med. 2013;59:263–70. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.123147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ecker BL, Simmons KD, Zaheer S, et al. Blood transfusion in major abdominal surgery for malignant tumors: A trend analysis using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:518–25. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nini A, Capitanio U, Larcher A, et al. Perioperative and oncologic outcomes of nephrectomy and caval thrombectomy using extracorporeal circulation and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest for renal cell carcinoma invading the supradiaphragmatic inferior vena cava and/or right atrium. Eur Urol. 2018;73:793–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciriaco P, Briganti A, Bernabei A, et al. Safety and early oncologic outcomes of lung resection in patients with isolated pulmonary recurrent prostate cancer: A single-center experience. Eur Urol. 2019;75:871–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Nationwide inpatient sample codes for major surgical oncological procedure (MSOP) and complications

| MSOP | Codes |

|---|---|

| Cystectomy | “576”,“577”,“688” |

| Pancreatectomy | “604”,“605”,“6062” |

| Lung resection | “3220”,“3229”,“323”,“324”,“325”,“326”,“329” |

| Gastrectomy | “435”,“436”,“437”,“438”,“439” |

| Prostatectomy | “525”,“526”,“527” |

| Nephrectomy | “554”,“5551”,“5552”,“5554” |

| Hysterectomy | “683”,“684”,“685”,“686”,“687”,“688”,“689” |

| Oophorectomy | “653”,“654”,“655”,“656” |

| Mastectomy | “8521”,“8522”,“8523”,“854” |

| Colectomy | “457”,“458”,“484”,“485”,“486”,“173” |

|

| |

| Complications | Codes |

|

| |

| Intraoperative | “9982” |

| Cardiac | “4100”,“4101”,“4102”,“4103”,“4104”,“4105”,“4106”,“4107”,“4108”,“4109”,“4110”,“4111”,“41181”,“41189”,“40201”,“40211”,“40291”,“4280”,“4281”,“42821”,“42831”,“42841”,“4289”,“4275”,“9971” |

| Respiratory | “5180”,“5184”,“5185”,“5187”,“51881”,“514”,“4660”,“46611”,“46619”,“4800”,“4801”,“4802”,“4803”,“4808”,“4809”,“481”,“4820”,“4821”,“4822”,“4823”,“4824”,“4828”,“4829”,“5070”,“51881”,“4830”,“4831”,“4838”,“485”,“486”,“7991”,“9973” |

| Genitourinary |

Diagnoses: “59010”,“59011”,“5902”,“59080”,“59081”,“5909”,“591”,“5933”,“5934”,“5935”,“59381”,“59382”,“59589”,“5961”,“5962”,“5966”,“9975”,“604”,“5991”,“7882”,“9963”,“5950”,“5970”, Procedures: “5501”,“5502”,“5503”,“5512”,“5593”,“5594”,“9761”,“9762”,“561”,“5641”,“5673”,“5674”,“5675”,“5681”,“5682”,“5683”,“5684”,“5685”,“5686”,“5689”,“5691”,“598” |

| Gastrointestinal | “5310”,“5311”,“5312”,“5313”,“5320”,“5321”,“5322”,“5323”,“5400”,“5401”,“5409”,“5600”,“5601”,“5602”,“5603”,“5608”,“5609”,“7876”,“9974”,“5692”,“5693”,“5695”,“5696”,“5793”,“00845” |

| Neurologic | “9970”,“99700”,“99701”,“99702”,“99709”,“436”,“951”,“952”,“953”,“954”,“955”,“956”,“3446”,“3530”,“354”,“355”,“7234” |

| Infection | “53641”,“51901”,“9985”,“993”,“038”,“0545”,“7907”,“99591”,“99592” |

| Vascular | “4151”,“41511”,“41512”,“41519”,“451”,“4510”,“4511”,“4512”,“4518”,“4519”,“4531”,“4534”,“45340”,“45341”,“45342”,“4538”,“4539”,“9972”,“9992”,“44422 “,“44481”,“44489”,“433”,“4330”,“4331”,“4332”,“4333”,“4338”,“4339”,“434”,“4340”,“4341”,“4349”,“436”,“437”,“4371”,“4372”,“4374”,“4373”,“4375”,“4376”,“4377”,“4378”,“4379”,“430”,“431”,“435”,“4599”,“4442”,“4448”,“9977” |

| Wound infection | “9983”,“99830”,“99831”,“99832”,“99833”,“9985”,“99859”,“99851”,“9986”,“567” |

| Other | “0418”,“2768”,“4589”,“584”,“7823”,“7824”,“7855”,“9950”,“9954”,“9994”,“9996”,“9997”,“9984”,“9987”,“9988”,“9989”,“53640”,“53642”,“53649”,“5793”,“99586” |

| Transfusion | “9902”,“9904”,“9900”,“9904”,“9902”, 9900” |

Delirium frequency of 3 431 632 patients underwent one of the 10 examined major surgical oncology procedures (MSOPs), Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2003–2013.

Supplementary Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression predicting delirium in 3 431 632 patients underwent one of 10 major surgical oncology procedures, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2003–2013

| Predictors of delirium | OR | CI 2.50% | CI 97.50% | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystectomy | 9.25 | 7.73 | 11.07 | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatectomy | 7.03 | 5.73 | 8.62 | <0.0001 |

| Lung resection | 6.85 | 5.79 | 8.10 | <0.0001 |

| Gastrectomy | 6.33 | 5.17 | 7.74 | <0.0001 |

| Colectomy | 6.06 | 5.14 | 7.14 | <0.0001 |

| Nephrectomy | 5.64 | 4.76 | 6.67 | <0.0001 |

| Oophorectomy | 4.98 | 3.90 | 6.37 | <0.0001 |

| Hysterectomy | 3.50 | 2.89 | 4.23 | <0.0001 |

| Mastectomy | 1.15 | 0.91 | 1.45 | 0.2 |

| Length of stay | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.05 | <0.0001 |

| Teaching hospital (ref. non-teaching) | 1.01 | 0.95 | 1.08 | 0.7 |

| Annual MSOP hospital volume low (ref. high) | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.08 | 0.9 |

| Medium | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.11 | 0.4 |

| Hospital size small (ref. large) | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.07 | 0.5 |

| Medium | 0.96 | 0.89 | 1.02 | 0.2 |

| 2009–2013 (ref. 2003–2008) | 1.43 | 1.35 | 1.52 | <0.0001 |

| Age 55–64 (Ref. <55) | 1.90 | 1.67 | 2.16 | <0.0001 |

| Age ≥65 | 3.80 | 3.32 | 4.35 | <0.0001 |

| Male (Ref. female) | 1.38 | 1.30 | 1.46 | <0.0001 |

| African American (Ref. Caucasian) | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.0002 |

| Non-Caucasian | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.0001 |

| Charlson 1 (Ref. Charlson 0) | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.13 | 0.03 |

| Charlson ≥2 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.29 | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid (Ref. private ins) | 1.21 | 1.03 | 1.42 | 0.02 |

| Medicare | 1.58 | 1.44 | 1.73 | <0.0001 |

| Other | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.15 | 0.7 |

| Midwest (Ref. South) | 1.27 | 1.18 | 1.36 | <0.0001 |

| Northeast | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 0.5 |

| West | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.008 |

| Dementia | 24.07 | 18.77 | 30.88 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol induced mental disorder | 0.90 | 0.65 | 1.25 | 0.5 |

| Mood disorder | 2.43 | 2.02 | 2.93 | <0.0001 |

| Non-organic disorder | 1.23 | 0.90 | 1.68 | 0.2 |

| Anxiety disorder | 1.53 | 1.39 | 1.69 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol dependence | 14.51 | 12.68 | 16.62 | <0.0001 |

| Schizophrenia disorder | 0.92 | 0.61 | 1.37 | 0.7 |

| Drug dependence syndrome | 1.70 | 1.09 | 2.67 | 0.02 |

| Non-dependent drug use | 1.11 | 1.02 | 1.20 | 0.01 |

| Drug-induced disorder | 4.81 | 3.65 | 6.33 | <0.0001 |

CI: confidence interval; MSOP: major surgical oncology procedures; OR: odds ratio.