Abstract

Previously, we reported that the neurosteroid allopregnanolone (Allo) promoted neural stem cell regeneration, restored cognitive function, and reduced Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) pathology in the triple transgenic Alzheimer’s mouse model (3xTgAD). To investigate the underlying systems biology of Allo action in AD models in vivo, we assessed the regulation of Allo on the bioenergetic system of the brain. Outcomes of these analysis indicated that Allo significantly reversed deficits in mitochondrial respiration and biogenesis and key mitochondrial enzyme activity and reduced lipid peroxidation in the 3xTgAD mice in vivo. To explore the mechanisms by which Allo regulates the brain metabolism, we conducted targeted transcriptome analysis. These data further confirmed that Allo upregulated genes involved in glucose metabolism, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and signaling pathways while simultaneously downregulating genes involved in Alzheimer’s pathology, fatty acid metabolism, and mitochondrial uncoupling and dynamics. Upstream regulatory pathway analysis predicted that Allo induced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) and coactivator 1-alpha (PPARGC1A) pathways while simultaneously inhibiting the presenilin 1 (PSEN 1), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathways to reduce AD pathology. Collectively, these data indicate that Allo functions as a systems biology regulator of bioenergetics, cholesterol homeostasis, and β-amyloid reduction in the brain. These systems are critical to neurological health, thus providing a plausible mechanistic rationale for Allo as a therapeutic to promote neural cell function and reduce the burden of AD pathology.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13311-019-00793-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Words: Allopregnanolone, Alzheimer’s disease, bioenergetics, mitochondria, therapeutics, transcriptome

Introduction

Allopregnanolone (Allo, 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one) is a neuroactive steroid synthesized de novo from progesterone in embryonic and adult central nervous system [1–3]. Previously, we demonstrated that Allo promoted neural stem cell regeneration, reversed neurogenic and cognitive deficits, and simultaneously reduced AD pathology in the triple transgenic Alzheimer’s mouse model (3xTgAD) [1–7]. The neurogenic and regenerative mechanism of Allo is mediated via GABAA receptors and L-type Ca2+ channel [3, 8, 9]. Further, Allo has been reported to regulate cholesterol homeostasis and clearance via induction of the liver-X-receptor (LXR) and its associated pregnane-X-receptor (PXR) systems [7].

The essential role of mitochondria in cellular bioenergetics and survival of neurons has been well-established [10–12]. Compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics and brain hypometabolism are among the earliest events in Alzheimer’s disease in both preclinical studies and clinical investigations [13–17]. In addition, mitochondria are required for the biosynthesis and metabolism of neurosteroids, including allopregnanolone and its precursor progesterone [18]. Earlier studies indicated that Allo protected neurons from apoptosis via direct inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability pore [19, 20]. However, the direct modulation of Allo on neural mitochondrial bioenergetics remains poorly understood.

In the current study, we investigated the impact of Allo on brain mitochondrial function and lipid peroxidation in female 3xTgAD mice in vivo. To explore the mechanisms by which Allo regulates the brain metabolism, we conducted gene expression analysis focused on mitochondrial bioenergetics and Alzheimer’s pathology. Outcomes of these investigations indicated that Allo potentiated brain mitochondrial bioenergetics via increasing brain glucose metabolism while simultaneously inhibiting brain fatty acid metabolism. In addition, upstream regulatory pathway analysis predicted that Allo regulated several key modulators to reduce AD pathology, which is consistent with our earlier analysis [7]. Collectively, the data are consistent with a systems mechanism of Allo action in the brain to coordinate neural regeneration, metabolic function, and reduction in AD pathology.

Methods

Transgenic Mice

Colonies of 3xTgAD mouse strain (C57BL6/129S; Gift from Dr. Frank Laferla, University of California, Irvine) [21] were bred and maintained at the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, CA) following National Institutes of Health guidelines on use of laboratory animals and an approved protocol by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed on 12 h light/dark cycles and provided ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were genotyped for every generation and checked by immunohistochemical assay every three to four generations to ensure the stability of AD-like phenotype as previously described [14, 21]. Only offspring from breeders that exhibit stable AD pathology were randomized into the study.

Experimental Design

To investigate impact of allopregnanolone on brain mitochondrial function, 6-month female 3xTgAD mice were randomly assigned to one of the following treatment groups: sham ovariectomized (sham-OVX), ovariectomized (OVX), OVX plus allopregnanolone (OVX + Allo) and OVX plus 17β-estradiol (OVX + E2). Mice were bilaterally OVXed. Six weeks after OVX, mice were subcutaneously injected with either vehicle (OVX group), Allo at 10 mg/kg (OVX + Allo group), or E2 at 60 μg/kg (OVX + E2 group). Twenty-four hours after treatment, mice were euthanized, and tissues were collected and processed.

Brain Tissue Preparation and Mitochondrial Isolation

Upon completion of treatment, mice (n = 6 per group) were sacrificed and the brains rapidly dissected on ice. Cerebellum and brain stem were removed from each brain and the hippocampal and cortical tissue of the left hemisphere was collected for other analysis. Brain mitochondria were isolated from the remaining right hemisphere following our previously established protocol [21). Briefly, the hemisphere was rapidly minced and homogenized at 4 °C in mitochondrial isolation buffer (MIB) (pH 7.4), containing sucrose (320 mM), EGTA (1 mM), Tris-HCl (10 mM), and Calbiochem’s Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set I (AEBSF-HCl 500 μM, aprotonin 150 nM, E-64 1 μM, EDTA disodium 500 μM, leupeptin hemisulfate 1 μM). Single-brain homogenates were then centrifuged at 1500 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in MIB, rehomogenized, and centrifuged again at 1500 × g for 5 min. The postnuclear supernatants from both centrifugations were combined, and crude mitochondria were pelleted by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 15% Percoll made in MIB and layered over a preformed 23%/40% Percoll discontinuous gradient, then centrifuged at 31,000 × g for 10 min. The purified mitochondria were collected at the 23%/40% interface and washed with 10 ml MIB by centrifugation at 16,700 × g for 13 min. The loose pellet was collected and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and washed in MIB by centrifugation at 9000 × g for 8 min. The resulting mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in MIB to an approximate concentration of 1 mg/ml. The resulting mitochondrial samples were used immediately for respiratory measurements or stored at − 80 °C for later protein and enzymatic assays. During mitochondrial purification, aliquots were collected for confirmation of mitochondrial purity and integrity following previously established protocols [22, 23]. Briefly, Western blot analysis was performed for mitochondrial anti-VDAC (1:500; Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), nuclear anti-histone H1 (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), endoplasmic reticulum anti-calnexin (1:2000, SPA 865; Stressgen, now a subsidiary of Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI), and cytoplasmic anti-myelin basic protein (1:500, clone 2; RDI, Concord, MA) (data not shown).

Brain Mitochondrial Respiration and Proton Leak

Mitochondrial respiration was measured using the Seahorse XF-96 metabolic analyzer following established protocol [24]. Briefly, protein concentration of purified mitochondria was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher #23227). The mitochondria pellets were resuspended into 1× MAS solution (70 mM sucrose, 220 mM mannitol, 10 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.5% (w/v) fatty acid free BSA, pH 7.2 at 37 °C), and 2 μg of each sample based on protein concentration was seeded into each assay well (8 wells/replicates per mitochondrial sample). Mitochondrial samples were then spun down at 2000g for 10 min and supplemented with 75 μl 1× MAS buffer with substrate (glutamate/malate 5 mM). Metabolic flux cartridges were loaded with the following reagents in 1× MAS: port A: ADP (20 mM); port B: oligomycin (30 μg/ml); port C: FCCP (28 μM); and port D: rotenone (16 μM) + antimycin (70 μM). Injection volumes for all ports were 25 μl. Mitochondrial respiration was measured sequentially in a coupled state with substrate present (basal respiration, state 4 respiration), followed by ADP stimulated state 3 respiration after port A injection, (phosphorylating respiration in the presence of ADP and substrates). Injection of oligomycin in port B induced state 4o respiration and the subsequent injection of FCCP in port C induced uncoupler-stimulated respiration state 3u, whereas the final injection of rotenone and antimycin in port D resulted in non-OXPHOS-related residual oxygen consumption OCRresidual. Respiratory control ratio value was calculated as the ratio of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) at state 3 respiration over OCR at state 4 respiration: OCR = OCRstate3u/OCRstate4o. Oxygen consumption attributed to proton leak is calculated as the difference between oligomycin induced mitochondrial respiration and rotenone + antimycin induced mitochondrial respiration: OCRproton-leak = OCRstate3u − OCRresidual. Proton leak percentage is calculated as oxygen consumption rate due to proton leak over state 3 OCR: proton leak% = OCRproton-leak/OCRstate3u × 100%.

Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number Measurement

Total DNA was isolated from hippocampal tissues with QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and analyzed by quantitative PCR. Relative mtDNA/nDNA ratio was calculated as the relative fold change of mt-ND1(mtDNA) content to HK2 (nDNA) content. Primers were as follows: mt-ND1 forward: 5′-CTAGCAGAAACAAACCGGGC-3′; mt-ND1 reverse: 5′-CCGGCTGCGTATTCTACGTT-3′; nHK2 forward: 5′-GCCAGCCTCTCCTGATTTTAGTGT-3′; and nHK2 reverse: 5′-GGGAACACAAAAGACCTCTTCTGG-3′.

RNA isolation and Protein Extraction

Total RNA was isolated from the designated hippocampal tissues using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. The quality and quantity of RNA samples were determined using the Experion RNA analysis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). RNA samples were reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at − 80 °C for gene array analysis. Total protein was extracted from designated hippocampal tissues using the Tissue Protein Extract Reagent (T-PER, Pierce, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein concentrations were determined by using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of proteins (20 μg/well) were loaded in each well of a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, electrophoresed with a Tris/glycine running buffer, and transferred to a 0.45-μm pore size polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and immunobloted with following primary antibodies: PDH E1 alpha antibody (1:1000, Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), pPDHser232 antibody (1:500, Chemicon, Ramona, CA), pPDHSer293 antibody (1:500, Chemicon, Ramona, CA), pPDHSer300 antibody (1:500, Chemicon, Ramona, CA), αKGDH antibody (1:1000, Proteintech, Chicago, IL), and GAPDH antibody (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were then applied. Signals were visualized by Pierce SuperSignal Chemiluminescent Substrates (Thermo Scientific) and captured by Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). All band intensities were quantified using Un-Scan-it software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Enzyme Activity Assay

PDH activity was measured by monitoring the conversion of NAD+ to NADH by following the change in absorption at 340 nm as previously described [14]. Isolated brain mitochondria were dissolved in 2% CHAPS buffer to yield a final concentration of 15 μg/μl and incubated at 37 °C in PDH Assay Buffer (35 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM KCN, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, (pH 7.25 with KOH), 200 mM sodium pyruvate, 2.5 mM rotenone, 4 mM sodium CoA, 40 mM TPP). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 15 mM NAD+. COX activity was assessed in isolated mitochondria (20 μg) using Rapid Microplate Assay kit for Mouse Complex IV Activity (Mitosciences, Eugene, OR) following the manufacturer’s instructions. α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (αKGDH) activity was assayed spectrophotometrically at 25 °C by measuring the rate of increase of absorbance due to NADH at 340 nm as described previously [25]. Briefly, each assay mixture contained 0.2 mM TPP, 2 mM NAD, 0.2 mM CoA, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 10 mM α-ketoglutarate, 130 mM HEPES-Tris pH 7.4, and 30 μg of isolated brain mitochondrial samples. The reaction was initiated by the addition of CoA and the initial rate was measured.

Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxides in hippocampal lysates were accessed using the leucomethylene blue assay, using tert-butyl hydroperoxide as a standard, by monitoring the 650 nm absorbance after 1 h incubation at RT. The aldehyde product or termination production of lipid peroxidation in brain mitochondria was determined by measuring thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). Samples were mixed with 0.15 M phosphoric acid. After the addition of thiobarbituric acid, the reaction mixture was heated to 100 °C for 1 h. After cooling and centrifugation, the formation of TBARS was determined by the absorbance of the chromophore (pink dye) at 531 nm using 600 nm as the reference wavelength.

qRT-PCR Gene Expression Analysis

Customized 384-well mouse mitochondrial and Alzheimer’s TaqMan low-density array (TLDA) cards (Format 96a, which enables analysis of 4 samples against 96 different genes) were manufactured by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). TaqMan real-time qRT-PCR reactions were performed on 50 ng cDNA samples mixed with the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix 2× (Applied Biosystems), under the thermal cycling conditions: stage 1: AmpErase UNG activation at 50 °C/2 min/100% ramp; stage 2: AmpliTaq gold DNA polymerase activation at 94.5 °C/10 min/100% ramp; stage 3: melt at 97 °C/30 sec/50% ramp, followed by anneal/extend at 59.7 °C/1 min/100% ramp, for 40 cycles. Fluorescence was detected on an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System equipped with the Sequence Detection System Software (Applied Biosystems). Data were analyzed using the RQ Manager Version 1.2 and DataAssist Version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression levels or fold changes relative to the reference group were calculated by the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method, with Ct denoting threshold cycle. Selection of the endogenous control gene for normalization was based on the control stability measure (M), which indicates the expression stability of control genes on the basis of non-normalized expression levels. M was calculated using the geNorm algorithm; genes with the lowest M values have the most stable expression. Samples collected from 6 animals per group were included in the analysis. For each sample, ΔCt was calculated as the difference in average Ct of the target gene and the endogenous control gene. For each group, mean 2−ΔCt was calculated as the geometric mean of 2−ΔCt of all samples in the group. Fold change was then calculated as mean 2−ΔCt (treatment group)/mean 2−ΔCt (comparison group). Fold change values greater than one indicate a positive expression or upregulation relative to the comparison group. Fold change values less than one indicate a negative expression or downregulation relative to the comparison group. Fold regulation was used to represent the fold change results in a biologically meaningful way. For fold change values greater than one (upregulation), the fold regulation is equal to the fold change; for fold change values less than one (downregulation), the fold regulation is the negative inverse of the fold change. The 2−ΔCt values for each target gene were statistically compared between the treatment and comparison group using Student’s t test [26].

Bioinformatic Analysis

IPA (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA) provided a bioinformatics computing tool to interpret our experimental gene expression dataset in the context of biological processes, pathways, molecular networks, and upstream regulators (www.ingenuity.com). Data of genes that showed changes with p < 0.2 were analyzed by a core analysis composed of a network analysis and an upstream regulator analysis. The network analysis identified biological connectivity among molecules in the dataset that were significantly up- or downregulated in a comparison (these molecules are called “network eligible molecules” or “focus molecules” that serve as “seeds” for generating networks) and their interactions with other molecules present in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. Network eligible molecules were combined into networks that maximized their specific connectivity. Additional molecules from the Ingenuity Knowledge Base (these molecules are called “interacting molecules”) were used to specifically connect two or more smaller networks to merge them into a larger one. A network was composed of direct (requiring direct physical contact between two molecules) and indirect (mediated by intermediate factor(s)) interactions among focus molecules and interacting molecules, with a maximum of 70 molecules per network. Generated networks were ranked by the network score according to their degree of relevance to the network eligible molecules from the dataset. The network score was calculated with Fisher’s exact test, taking into account the number of network eligible molecules in the network and the size of the network, as well as the total number of network eligible molecules analyzed and the total number of molecules in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base that were included in the network. Higher network scores are associated with lower probability of finding the observed number of network eligible molecules in a given network by chance. The Ingenuity’s Upstream Regulator Analysis in IPA is a tool that predicts upstream regulators from gene expression data based on the literature and compiled in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. A Fisher’s exact test p value is calculated to assess the significance of enrichment of the gene expression data for the genes downstream of an upstream regulator. A z-score was given to indicate the degree of consistent agreement or disagreement of the actual versus the expected direction of change among the downstream gene targets. A prediction about the state of the upstream regulator, either activated or inhibited, was made based on the z-score.

Statistics

All data were presented as means ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman–Keuls post hoc analysis.

Results

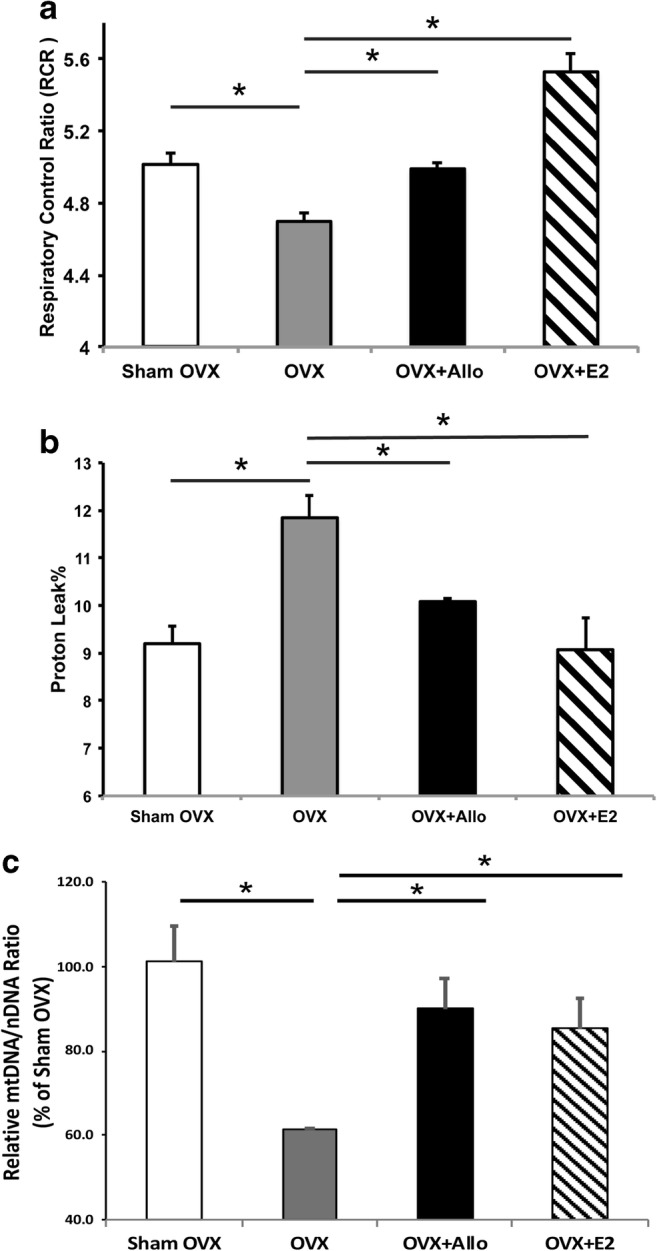

Potentiation of Brain Mitochondrial Respiration and Biogenesis by Allopregnanolone

To determine the impact of Allo on brain mitochondrial function, we analyzed the respiration profiles of isolated brain mitochondria 24 h after 10 mg/kg Allo treatment (SC injection), which proved to be neurogenic in previous studies [4]. 17β-estradiol (E2) was included in all measures of mitochondrial functions as a positive control [27, 28]. Consistent with our previous findings [28], 6 weeks of OVX induced a significant decline in mitochondrial respiration (Fig.1A; p < 0.05, n = 6 per group) in female 3xTgAD mice, compared to the sham group. Allo treatment reversed the OVX-induced deficit to restore mitochondrial respiration to normal level similar as the sham group, whereas E2 treatment potentiated mitochondrial respiration exceeding control magnitude (Fig. 1A; p < 0.05, n = 6 per group). OVX induced a significant rise in proton leak, an indicator of incomplete coupling, in 3xTgAD mice (Fig. 1B; p < 0.05, n = 6 per group). Both Allo and E2 treatment reversed the OVX-induced increase in mitochondrial proton leak by a comparable magnitude (Fig. 1B; p < 0.05, n = 6 per group).

Fig. 1.

Allo increased brain mitochondrial efficiency and biogenesis in OVX 3xTgAD mice. (A) Six weeks of OVX induced a decline in mitochondrial respiration in 3xTgAD mice, compared to the sham group. Allo and E2 treatment significantly reversed the decreased mitochondrial respiration in OVX 3xTgAD mice (p < 0.05, n = 6 per group). (B) OVX induced a significant rise in proton leak in 3xTgAD mice, which was significantly reversed by both Allo and E2 treatment by a comparable magnitude (p < 0.05, n = 6 per group). (C) Allo and E2 treatment significantly restored OVX-induced decrease in mtDNA/nDNA ratio to levels comparable to the sham group (p < 0.05, n = 3–4 per group)

Potentiated mitochondrial respiration could be coupled with increased mitochondrial biogenesis; thus, mitochondrial DNA copy number was measured in hippocampal tissue from the same set of animals. As shown in Fig. 1C, mtDNA/nDNA ratio was significantly decreased in OVX group compared to the sham group. Allo and E2 treatment restored OVX-induced decrease in mitochondria DNA copy number to levels comparable to the sham group. These findings were consistent with increased mitochondrial respiration, suggesting Allo enhances cellular mitochondrial function in OVX mice by regulating mitochondrial biogenesis.

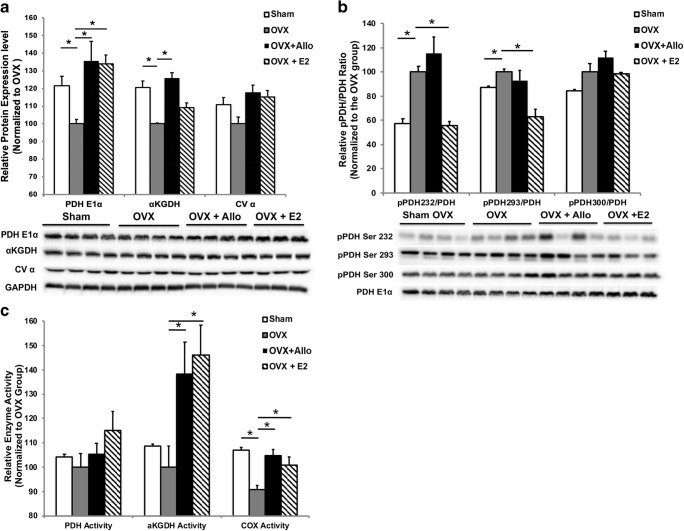

Impact of Allo on Mitochondrial Bioenergetic Enzyme Protein Level and Activity

Increased mitochondrial respiration and biogenesis would be predictive of increased mitochondrial enzyme protein and activity. To investigate the direct impact of Allo on key mitochondrial enzymes, we assessed the protein levels of the pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit E1α (PDHE1α, a primary regulator linking glycolysis to the TCA cycle and lipogenesis), α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (αKGDH, the determiner of metabolic flux through the TCA cycle), and α subunit of ATP synthase (CVα). In 3xTgAD mice, compared to the sham group, OVX induced significant decrease in expression of αKGDH and PDHE1α (Fig. 2A; p < 0.05, n = 4 per group) and a trend toward decreased expression of CVα. Allo treatment reversed the OVX-induced decrease in αKGDH and PDHE1α expression (Fig. 2A; p < 0.05, n = 4 per group). E2 treatment reversed the OVX-induced decrease in PDHE1α expression (Fig. 2A; p < 0.05, n = 3–4 per group). Both Allo and E2 treatment induced a trend toward but not significant increase in expression of CVα (Fig. 2A; n = 3–4 per group).

Fig. 2.

Impact of Allo on mitochondrial bioenergetic enzyme protein level and activity. (A) Compared to the sham group, OVX significantly decreased the expression of αKGDH and PDHE1α (p < 0.05, n = 4 per group) and induced a trend toward decreased expression of CVα in 3xTgAD mice. Allo treatment reversed the OVX-induced decrease in αKGDH and PDHE1α expression (p < 0.05, n = 4 per group). E2 treatment reversed the OVX-induced decrease in PDHE1α expression (p < 0.05, n = 3–4 per group). Both Allo and E2 treatment induced a trend toward but not significant increase in expression of CVα. (B) Compared to the sham group, OVX significantly increased the phosphorylation of Ser232 and Ser293 of PDHE1α in 3xTgAD mice (p < 0.05, n = 3–4 per group). E2 treatment significantly reduced the OVX-induced increase in phosphorylation of Ser232 and Ser293 (p < 0.05, n = 3–4 per group), whereas Allo treatment had no effect on phosphorylation of these sites (n = 3–4 per group). (C) PDH activity did not significantly changed by OVX or Allo treatment in 3xTgAD mice, whereas E2 treatment induced a modest but not statistically significant increase in PDH activity compared to OVX group (n = 6 per group). αKGDH activity was unaffected by OVX in 3xTgAD mice. However, both Allo and E2 treatment significantly increased αKGDH activity (p < 0.05, n = 6 per group), when compared to OVX group. COX activity was significantly decreased by OVX in 3xTgAD mice, which was reversed by both Allo and E2 treatments (p < 0.05, n = 6 per group)

PDH activity is inhibited by reversible phosphorylation at three sites on PDHE1α: Ser 232, Ser293, and Ser300. Therefore, we determined the phosphorylation level on these three sites of PDHE1α in 3xTgAD mice following OVX and Allo or E2 treatment. Compared to the sham group, OVX induced a significant increase in the phosphorylation of Ser232 and Ser293 and a trend toward increased phosphorylation of Ser300 (Fig. 2B; p < 0.05, n = 3–4 per group). E2 treatment significantly reduced the OVX-induced increase in phosphorylation of Ser232 and Ser293 (Fig. 2B; p < 0.05, n = 3–4 per group), whereas Allo treatment had no effect on phosphorylation of these sites (Fig. 2B; n = 3–4 per group).

To further determine whether changes in mitochondrial enzyme level were linked to corresponding modification of enzyme function, we accessed the activity of PDH, αKGDH, and cytochrome c oxidase (COX). PDH activity was not significantly changed by OVX in 3xTgAD mice (Fig. 2C). Compared to OVX group, Allo treatment did not regulate PDH activity, whereas E2 treatment induced a modest but not statistically significant increase in PDH activity (Fig. 2C; n = 6 per group). αKGDH activity was unaffected by OVX in 3xTgAD mice. However, both Allo and E2 treatment significantly increased αKGDH activity (Fig. 2C; p < 0.05, n = 6 per group), when compared to the OVX group. COX activity was significantly decreased by OVX in 3xTgAD mice, which was reversed by both Allo and E2 treatments (Fig. 2C; p < 0.05, n = 6 per group).

Together, Allo treatment effectively reversed OVX-induced decrease in protein levels and activities of key mitochondrial enzymes in 3xTgAD mice.

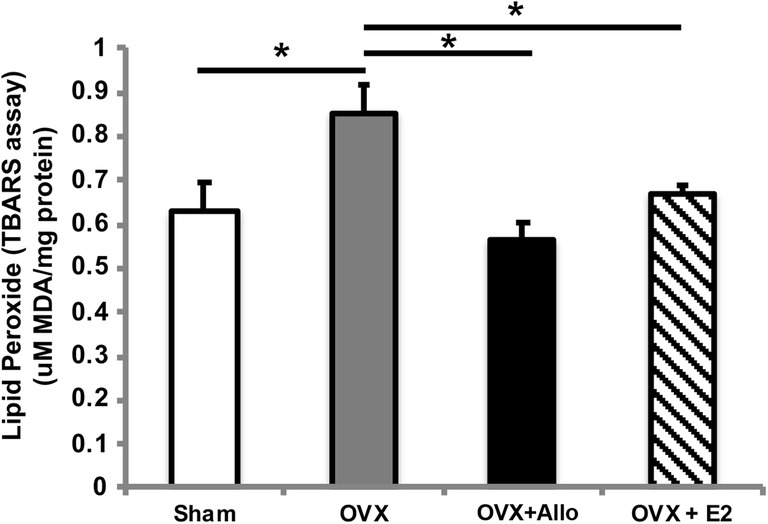

Reduction of Lipid Peroxidation by Allo Treatment

Because compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics is frequently paralleled by an increase in oxidative damage [29], we assessed impact of Allo on lipid peroxides as an indicator of oxidative damage. As shown in Fig. 3, OVX induced a significant increase in lipid peroxidation which was reversed by both Allo and E2 to levels comparable to Sham group (p < 0.05, n = 6 per group).

Fig. 3.

Reduction of lipid peroxidation by Allo treatment. OVX induced a significant increase in lipid peroxidation in 3xTgAD mice, which was reversed by both Allo and E2 treatments to levels comparable to the sham group (p < 0.05, n = 6 per group)

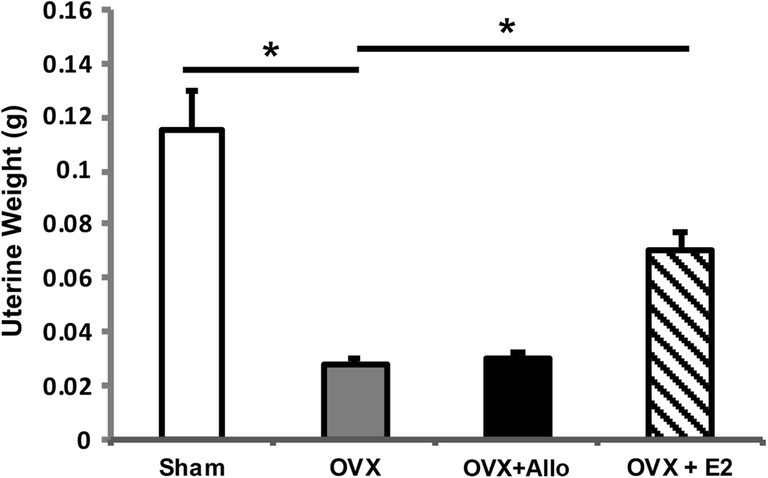

No Impact on Uterine Weight by Allo In Vivo

As shown in Fig. 4, OVX induced a significant decrease in uterine weight relative to the sham group. Allo had no impact on uterine weight as no difference was observed between OVX and OVX + Allo group. As expected, E2 significantly increased uterine weight in the OVX 3xTgAD mice (Fig. 4; p < 0.05, n = 10–12 per group). This finding suggests that Allo will not induce peripheral uterotrophic side effects.

Fig. 4.

No impact on uterine weight by Allo in vivo. OVX induced a significant decrease in uterine weight relative to the sham group. E2 treatment significantly increased uterine weight in the OVX 3xTgAD mice (p < 0.05, n = 10–12 per group), whereas Allo treatment had no impact on uterine weight in vivo (n = 10–12 per group)

Impact of Allo Treatment on Bioenergetic and Alzheimer’s-Related Gene Expression

As an initial analysis of broader Allo effect on biogenetic and Aβ generating pathways, we conducted a targeted q-PCR array containing 192 relevant genes. Compared to the sham group, increased expression in Acadl, Pla2g3, Mmp2, Mme, Cand1, and Mfn1and decreased expression in Sdhb, Acat1, and Txnrd2 were observed in the OVX group, whereas relative to OVX group, E2 treatment significantly increased expression in Ldhb, Gsk3b, Uqcrc1, Nos2, and Irs2 and decreased expression in Slc2a3, Slc16a7, Timm22, and Apba2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gene expression changes in OVX and OVX + E2 groups

| OVX vs. sham | OVX + E2 vs. OVX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Fold change | p value | Gene | Fold change | p value |

| Mme | 1.1669 | 0.0249 | Nos2 | 1.5088 | 0.027 |

| Cand1 | 1.1973 | 0.049 | Irs2 | 1.3607 | 0.0202 |

| Mfn1 | 1.2645 | 0.0322 | Ldhd | 1.2566 | 0.0089 |

| Acadl | 1.4196 | 0.0111 | Uqcrc1 | 1.2108 | 0.0304 |

| Pla2g3 | 1.6082 | 0.0253 | Gsk3b | 1.1704 | 0.0158 |

| Mmp2 | 2.3635 | 0.0112 | Slc2a3 | 0.9074 | 0.0202 |

| Sdhb | 0.7083 | 0.0015 | Timm22 | 0.9054 | 0.0154 |

| Acat1 | 0.7171 | 0.0278 | Apba2 | 0.8504 | 0.0247 |

| Txnrd2 | 0.7930 | 0.0094 | Slc16a7 | 0.7882 | 0.0364 |

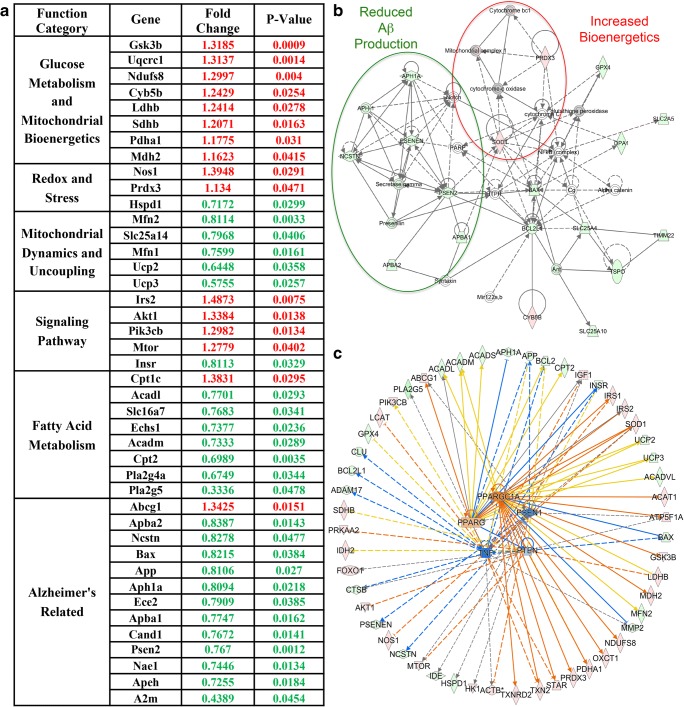

Relative to OVX group, Allo treatment induced significant changes in 42 genes. Based on their function, these 42 genes were categorized into 6 major functional groups. As shown in Fig. 5A, Allo significantly increased expression of genes involved in glucose metabolism (Gsk3b, Uqcrc1, Ndufs8, Cyb5b, Ldhb, Sdhb, Pdha1, Mdh2), redox and stress (Nos1, Prdx3), and signaling pathways (Irs2, Akt1, Pik3cb, Mtor) while decreasing expression of genes regulating mitochondrial dynamics and uncoupling (Mfn2, Slc25a14, Mfn1, Ucp2, Ucp3), fatty acid metabolism (Acadl, Slc16a7, Echs1, Acadm, Cpt2, Pla2g4a, Pla2g5), and Alzheimer’s-related (Apba2, Ncstn, Bax, App, Aph1a, Ece2, Apba1, Cand1, Psen2, Nae1, Apeh, A2m).

Fig. 5.

Impact of Allo on bioenergetic and Alzheimer’s-related gene expression. (A) Relative to OVX, Allo treatment significantly increased expression of genes involved in glucose metabolism and mitochondrial bioenergetics, redox and stress, and signaling pathways while simultaneously decreasing expression of genes involved in mitochondrial dynamics and uncoupling, fatty acid metabolism, and Alzheimer’s-related. (B) Molecular network analysis revealed that Allo induced a decrease in genes within the PSEN1 network and a moderate increase in genes within the mitochondrial bioenergetics and redox network. Genes with increased expression after Allo treatment are shown in red, and genes with decreased expression are shown in green. (C) Upstream regulatory analysis predicted that Allo treatment would activate PPARG and PPARGC1A, while inhibiting the PSEN1, TNF, and PTEN upstream pathways

To further investigate the potential upstream pathways involved in Allo’s regulation of brain bioenergetics and beta-amyloid processing, we conducted molecular network analysis and upstream regulator analysis using IPA. Molecular network analysis further confirmed that Allo induced a moderate increase in genes within the mitochondrial bioenergetics and redox network while simultaneously decreasing expression of genes within the Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) network (Fig. 5B). These findings were supported by upstream regulatory analyses, which predicted that Allo treatment would activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PPARGC1A), two key mitochondrial biogenesis modulators, while inhibiting the PSEN1 upstream pathway. In addition, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) were predicted to be inhibited, suggesting decreased Aβ-induced systemic inflammation and synaptic toxicity in brain following Allo treatment (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

Previous studies from our group indicated that reproductive senescence or ovarian hormone loss by ovariectomy (OVX) significantly exacerbates glucose hypometabolism, mitochondrial deficits, and AD pathology in the female triple transgenic Alzheimer’s mouse brain (3xTgAD), whereas Allo promotes regeneration of neural progenitor cells [4, 8] and Allo-induced regeneration and survival of neural progenitors correlated with improved learning and memory in 3xTgAD mice [1–6, 30]. In the current study, we further demonstrated that in vivo, Allo significantly reversed OVX-induced defected mitochondrial bioenergetics and enzyme activities and suppressed OVX-induced oxidative damage. Allo bioenergetic effect could be explained by its ability to directly upregulate the transcription of genes involved in glucose metabolism, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and signaling pathways while reducing expression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, Alzheimer’s pathology, and mitochondrial uncoupling and dynamics. Upstream regulatory pathway analysis predicted that in parallel Allo also upregulated PPARGC1A and PPARG pathways while simultaneously inhibiting the PSEN 1, PTEN, and TNF pathways.

Allo Increased Mitochondrial Efficiency

Efficiency and viability of the bioenergetic system is a fundamental determinant of synaptic and brain function [10, 29, 31]. Compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics is among the earliest pathogenic events in Alzheimer’s disease [14]. We previously demonstrated that loss of ovarian hormones led to deficits in brain glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function in the 3xTgAD mouse model, which were reversed by E2 [27, 32]. These findings were confirmed in the current study. Further, we demonstrated that Allo, a neurogenic neurosteroid, also potentiated brain mitochondrial function and reversed multiple OVX-induced deficits in 3xTgAD mice by a magnitude comparable to E2. The bioenergetic modulating effect of Allo reported herein is through regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and key mitochondrial enzymes.

The Allo dose tested herein was unlikely to activate the classical progesterone receptor (PR) to elicit a PR-mediated response which requires micromolar concentrations of Allo [33]. Previous findings reported that GABAA receptors and androgen receptor might be required for the bioenergetics modulation by Allo in neurons [34]. However, further investigation is required to confirm the involvement of these two receptors in vivo.

The Impact of Allo on Mitochondrial Proton Leak

In the current study, we observed that Allo decreased proton leak in OVX 3xTgAD mice. This was likely due to the suppression of mitochondrial uncoupling, which was consistent with the decrease in gene expression of multiple mitochondrial uncoupling proteins, UCP2, UCP3, and UCP5. Further, Allo reduced expression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, which will induce mitochondrial uncoupling directly or via induction of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins [35]. In addition, Allo-induced suppression of mitochondrial uncoupling and increase in mitochondrial respiration were paralleled by a reduction in lipid peroxidation, indicating reduced oxidative stress and improved mitochondrial efficiency following Allo treatment in vivo. Collectively, these data indicate that Allo promotes efficient mitochondrial respiration through multiple mechanisms involving electron transport chain function and coupling efficiency.

Allo Induced Activation of Glucose Metabolism and Simultaneous Inhibition of Fatty Acid Metabolism

Our results indicated that Allo induced a dichotomous response in terms of energy production by activating glucose metabolism and mitochondrial bioenergetics while simultaneously suppressing genes involved in fatty acid metabolism. Allo enhanced mitochondrial catalytic capacity by increasing the expression and activities of key mitochondrial enzymes. Allo also increased expression of genes involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism, including lactate dehydrogenase (Ldhb), pyruvate dehydrogenase (Pdha1), glycogen synthase kinase β (GSK3b), phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases (PI3k), protein kinase B (Akt), and insulin receptor substrate 2 (Irs2). Collectively, these changes would lead to an increase of glucose metabolism in the brain, which were consistent with the bioinformatic upstream prediction of the activation of the PPARGC1A and PPARG pathways by Allo treatment.

Our results also revealed that Allo significantly decreased gene expression of multiple key enzymes required for mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism, including carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (Cpt2), Enoyl-CoA hydratase short chain 1 (Echs1), acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Acadm), and long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Acadl). Together with our previous data showing that increased mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism was associated with white matter degeneration in Alzheimer’s [36], the suppression by Allo of fatty acid metabolism in mitochondria might contribute to preserving lipid integrity in the brain to reduce AD pathology.

Allo Induced Reduction in AD Pathology

We previously demonstrated that Allo treatment for 6 months (once per week regimen) significantly reduced β-amyloid burden in the 3xTgAD mouse model [7]. Reduction in pathology was accompanied by induction of liver-X-receptor (LXR), pregnane-X-receptor, and 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA-reductase (HMG-CoA-R), suggesting Allo regulation of cholesterol trafficking and homeostasis. These findings were supported in the current study by the bioinformatic prediction that Allo would regulate PGC-1α and PPARγ to induce expression of LXR [37]. Consistent with reduction in β-amyloid burden, Allo suppressed PSEN1 gene expression which led to bioinformatic prediction of inhibition of the amyloidogenic PSEN1 pathway. These findings are relevant to previous studies demonstrating that compromised mitochondrial function was closely associated with β-amyloid overproduction and mitochondrial deposition [13, 14, 32, 38–40], whereas improvement of brain bioenergetics was paralleled by reduction in β-amyloid burden [41].

In addition, TNF and PTEN were predicted to be inhibited by Allo in OVX 3xTgAD mice, which were consistent with previous reports showing that inhibition of TNFα reduced recruitment of microglial cells in the central neural system [42] and inhibition of PTEN reversed Aβ-induced synaptic toxicity [43]. Allo-induced inhibition of TNF and PTEN may be due to the improved brain bioenergetics and reduced β-amyloid burden; however, further analyses are required to assess the direct impacts of Allo on these two pathways.

Collectively, our findings demonstrate a novel mechanism of action of Allo in the brain that centers on the bioenergetic system of the brain, whereby Allo promotes mitochondrial function and glucose metabolism. These findings extend the understanding of Allo’s impact to promote female brain bioenergetic function that is compromised upon depletion of ovarian hormones, at natural menopause or after premenopausal oophorectomy. Further, promoting mitochondrial function in brain has downstream consequences to prevent development of β-amyloid pathology by improving glucose metabolism and cholesterol clearance in brain while simultaneously suppressing pathways involved in Aβ-induced systemic inflammation and synaptic toxicity. Although the in vivo studies reported herein were conducted in female 3xTgAD mice, our earlier studies of Allo in 3xTgAD and non-Tg males also indicated multiple beneficial outcomes, including neurogenesis, improved cholesterol homeostasis, and reduced burden of AD pathology [4, 7]. Together, these studies provide mechanistic and preclinical evidence for Allo as a systems biology regulator for prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 7.51 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) grants U01-AG031115, U01-AG047222, UF1-AG046148, and P01-AG026572 to Roberta Diaz Brinton.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Irwin RW, Brinton RD. Allopregnanolone as regenerative therapeutic for Alzheimer’s disease: translational development and clinical promise. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;113:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin RW, Solinsky CM, Brinton RD. Frontiers in therapeutic development of allopregnanolone for Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2014;8:203. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinton RD. Neurosteroids as regenerative agents in the brain: therapeutic implications. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2013;9(4):241–50. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JM, Singh C, Liu L, Irwin RW, Chen S, Chung EJ, et al. Allopregnanolone reverses neurogenic and cognitive deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(14):6498–503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001422107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinton RD, Wang JM. Preclinical analyses of the therapeutic potential of allopregnanolone to promote neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo in transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2006;3(1):11–7. doi: 10.2174/156720506775697160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh C, Liu L, Wang JM, Irwin RW, Yao J, Chen S, et al. Allopregnanolone restores hippocampal-dependent learning and memory and neural progenitor survival in aging 3xTgAD and nonTg mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(8):1493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, Wang JM, Irwin RW, Yao J, Liu L, Brinton RD. Allopregnanolone promotes regeneration and reduces β-amyloid burden in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e24293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JM, Johnston PB, Ball BG, Brinton RD. The neurosteroid allopregnanolone promotes proliferation of rodent and human neural progenitor cells and regulates cell-cycle gene and protein expression. J Neurosci. 2005;25(19):4706–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4520-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang JM, Brinton RD. Allopregnanolone-induced rise in intracellular calcium in embryonic hippocampal neurons parallels their proliferative potential. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9(Suppl 2):S11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S2-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brinton RD. The healthy cell bias of estrogen action: mitochondrial bioenergetics and neurological implications. Trends in Neurosciences. 2008;31(10):529–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magistretti PJ. Neuron-glia metabolic coupling and plasticity. J Exp Biol. 2006;209(Pt 12):2304–11. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao J, Hamilton RT, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. Decline in mitochondrial bioenergetics and shift to ketogenic profile in brain during reproductive senescence. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800(10):1121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao J, Irwin RW, Zhao L, Nilsen J, Hamilton RT, Brinton RD. Mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit precedes Alzheimer’s pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(34):14670–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903563106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva DF, Selfridge JE, Lu J. E L, Roy N, Hutfles L, et al. Bioenergetic flux, mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial morphology dynamics in AD and MCI cybrid cell lines. Human molecular genetics. 2013;22(19):3931–46. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosconi L, Berti V, Swerdlow RH, Pupi A, Duara R, de Leon M. Maternal transmission of Alzheimer’s disease: prodromal metabolic phenotype and the search for genes. Human Genomics. 2010;4(3):170–93. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-3-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosconi L, de Leon M, Murray J, E Lezi, Lu J, Javier E, et al. Reduced mitochondria cytochrome oxidase activity in adult children of mothers with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2011;27(3):483-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Yang SY, He XY, Isaacs C, Dobkin C, Miller D, Philipp M. Roles of 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10 in neurodegenerative disorders. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and molecular Biology. 2014;143:460–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sayeed I, Parvez S, Wali B, Siemen D, Stein DG. Direct inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: a possible mechanism for better neuroprotective effects of allopregnanolone over progesterone. Brain Research. 2009;1263:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xilouri M, Papazafiri P. Anti-apoptotic effects of allopregnanolone on P19 neurons. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;23(1):43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39(3):409–21. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irwin RW, Yao J, Hamilton RT, Cadenas E, Brinton RD, Nilsen J. Progesterone and estrogen regulate oxidative metabolism in brain mitochondria. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):3167–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilsen J, Irwin RW, Gallaher TK, Brinton RD. Estradiol in vivo regulation of brain mitochondrial proteome. The Journal of Neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(51):14069–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers GW, Brand MD, Petrosyan S, Ashok D, Elorza AA, Ferrick DA, et al. High throughput microplate respiratory measurements using minimal quantities of isolated mitochondria. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai JC, Cooper AJ. Brain alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex: kinetic properties, regional distribution, and effects of inhibitors. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1986;47(5):1376–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao L, Morgan TE, Mao Z, Lin S, Cadenas E, Finch CE, et al. Continuous versus cyclic progesterone exposure differentially regulates hippocampal gene expression and functional profiles. PloS One. 2012;7(2):e31267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding F, Yao J, Zhao L, Mao Z, Chen S, Brinton RD. Ovariectomy induces a shift in fuel availability and metabolism in the hippocampus of the female transgenic model of familial Alzheimer’s. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao J, Irwin R, Chen S, Hamilton R, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. Ovarian hormone loss induces bioenergetic deficits and mitochondrial β-amyloid. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(8):1507–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao J, Brinton RD. Targeting mitochondrial bioenergetics for Alzheimer’s prevention and treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(31):3474–9. doi: 10.2174/138161211798072517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen S, Wang JM, Irwin RW, Yao J, Liu L, Brinton RD. Allopregnanolone promotes regeneration and reduces beta-amyloid burden in a preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease. PloS One. 2011;6(8):e24293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brinton RD. Estrogen-induced plasticity from cells to circuits: predictions for cognitive function. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2009;30(4):212–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao J, Irwin R, Chen S, Hamilton R, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. Ovarian hormone loss induces bioenergetic deficits and mitochondrial beta-amyloid. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33(8):1507–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rupprecht R, Reul JM, Trapp T, van Steensel B, Wetzel C, Damm K, et al. Progesterone receptor-mediated effects of neuroactive steroids. Neuron. 1993;11(3):523–30. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90156-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimm A, Schmitt K, Lang UE, Mensah-Nyagan AG, Eckert A. Improvement of neuronal bioenergetics by neurosteroids: implications for age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842(12 Pt A):2427–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woyda-Ploszczyca AM, Jarmuszkiewicz W. The conserved regulation of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins: from unicellular eukaryotes to mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1858(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klosinski LP, Yao J, Yin F, Fonteh AN, Harrington MG, Christensen TA, et al. White matter lipids as a ketogenic fuel supply in aging female brain: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(12):1888–904. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landreth G, Jiang Q, Mandrekar S, Heneka M. PPARgamma agonists as therapeutics for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2008;5(3):481–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao J, Brinton RD. Estrogen regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics: implications for prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2012;64:327–71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394816-8.00010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabuzda D, Busciglio J, Chen LB, Matsudaira P, Yankner BA. Inhibition of energy metabolism alters the processing of amyloid precursor protein and induces a potentially amyloidogenic derivative. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(18):13623–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedros I, Petrov D, Allgaier M, Sureda F, Barroso E, Beas-Zarate C, et al. Early alterations in energy metabolism in the hippocampus of APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1842(9):1556–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao J, Chen S, Mao Z, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose treatment induces ketogenesis, sustains mitochondrial function, and reduces pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PloS One. 2011;6(7):e21788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shamim D, Laskowski M. Inhibition of Inflammation mediated through the tumor necrosis factor α biochemical pathway can lead to favorable outcomes in Alzheimer disease. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2017;9:1179573517722512. doi: 10.1177/1179573517722512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knafo S, Sánchez-Puelles C, Palomer E, Delgado I, Draffin JE, Mingo J, et al. PTEN recruitment controls synaptic and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s models. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(3):443–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 7.51 kb)