Abstract

Background

More than two‐thirds of pregnant women experience low‐back pain and almost one‐fifth experience pelvic pain. The two conditions may occur separately or together (low‐back and pelvic pain) and typically increase with advancing pregnancy, interfering with work, daily activities and sleep.

Objectives

To update the evidence assessing the effects of any intervention used to prevent and treat low‐back pain, pelvic pain or both during pregnancy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth (to 19 January 2015), and the Cochrane Back Review Groups' (to 19 January 2015) Trials Registers, identified relevant studies and reviews and checked their reference lists.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any treatment, or combination of treatments, to prevent or reduce the incidence or severity of low‐back pain, pelvic pain or both, related functional disability, sick leave and adverse effects during pregnancy.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy.

Main results

We included 34 RCTs examining 5121 pregnant women, aged 16 to 45 years and, when reported, from 12 to 38 weeks’ gestation. Fifteen RCTs examined women with low‐back pain (participants = 1847); six examined pelvic pain (participants = 889); and 13 examined women with both low‐back and pelvic pain (participants = 2385). Two studies also investigated low‐back pain prevention and four, low‐back and pelvic pain prevention. Diagnoses ranged from self‐reported symptoms to clinicians’ interpretation of specific tests. All interventions were added to usual prenatal care and, unless noted, were compared with usual prenatal care. The quality of the evidence ranged from moderate to low, raising concerns about the confidence we could put in the estimates of effect.

For low‐back pain

Results from meta‐analyses provided low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, inconsistency) that any land‐based exercise significantly reduced pain (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.64; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.03 to ‐0.25; participants = 645; studies = seven) and functional disability (SMD ‐0.56; 95% CI ‐0.89 to ‐0.23; participants = 146; studies = two). Low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision) also suggested no significant differences in the number of women reporting low‐back pain between group exercise, added to information about managing pain, versus usual prenatal care (risk ratio (RR) 0.97; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.17; participants = 374; studies = two).

For pelvic pain

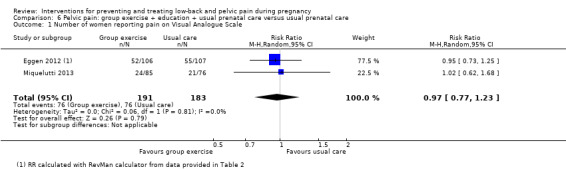

Results from a meta‐analysis provided low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision) of no significant difference in the number of women reporting pelvic pain between group exercise, added to information about managing pain, and usual prenatal care (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.23; participants = 374; studies = two).

For low‐back and pelvic pain

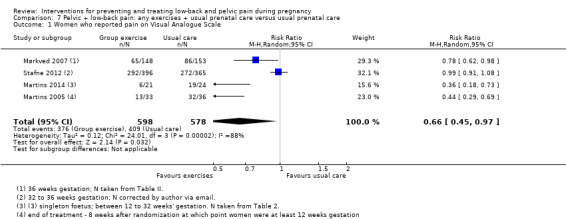

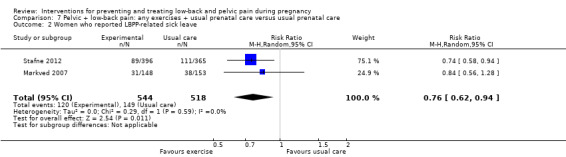

Results from meta‐analyses provided moderate‐quality evidence (study design limitations) that: an eight‐ to 12‐week exercise program reduced the number of women who reported low‐back and pelvic pain (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.97; participants = 1176; studies = four); land‐based exercise, in a variety of formats, significantly reduced low‐back and pelvic pain‐related sick leave (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.62 to 0.94; participants = 1062; studies = two).

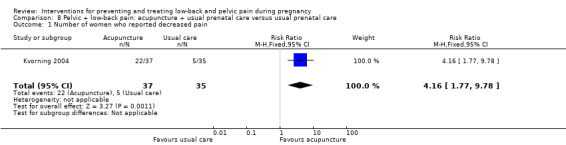

The results from a number of individual studies, incorporating various other interventions, could not be pooled due to clinical heterogeneity. There was moderate‐quality evidence (study design limitations or imprecision) from individual studies suggesting that osteomanipulative therapy significantly reduced low‐back pain and functional disability, and acupuncture or craniosacral therapy improved pelvic pain more than usual prenatal care. Evidence from individual studies was largely of low quality (study design limitations, imprecision), and suggested that pain and functional disability, but not sick leave, were significantly reduced following a multi‐modal intervention (manual therapy, exercise and education) for low‐back and pelvic pain.

When reported, adverse effects were minor and transient.

Authors' conclusions

There is low‐quality evidence that exercise (any exercise on land or in water), may reduce pregnancy‐related low‐back pain and moderate‐ to low‐quality evidence suggesting that any exercise improves functional disability and reduces sick leave more than usual prenatal care. Evidence from single studies suggests that acupuncture or craniosacral therapy improves pregnancy‐related pelvic pain, and osteomanipulative therapy or a multi‐modal intervention (manual therapy, exercise and education) may also be of benefit.

Clinical heterogeneity precluded pooling of results in many cases. Statistical heterogeneity was substantial in all but three meta‐analyses, which did not improve following sensitivity analyses. Publication bias and selective reporting cannot be ruled out.

Further evidence is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimates of effect and change the estimates. Studies would benefit from the introduction of an agreed classification system that can be used to categorise women according to their presenting symptoms, so that treatment can be tailored accordingly.

Plain language summary

Treatments for preventing and treating low‐back and pelvic pain during pregnancy

Review question

We looked for evidence about the effects of any treatment used to prevent or treat low‐back pain, pelvic pain or both during pregnancy. We also wanted to know whether treatments decreased disability or sick leave, and whether treatments caused any side effects for pregnant women.

Background

Pain in the lower‐back, pelvis, or both, is a common complaint during pregnancy and often gets worse as pregnancy progresses. This pain can disrupt daily activities, work and sleep for pregnant women. We wanted to find out whether any treatment, or combination of treatments, was better than usual prenatal care for pregnant women with these complaints.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to 19 January 2015. We included 34 randomised studies in this updated review, with 5121 pregnant women, aged 16 to 45 years. Women were from 12 to 38 weeks’ pregnant. Studies looked at different treatments for pregnant women with low‐back pain, pelvic pain or both types of pain. All treatments were added to usual prenatal care, and were compared with usual prenatal care alone in 23 studies. Studies measured women's symptoms in different ways, ranging from self‐reported pain and sick leave to the results of specific tests.

Key results

Low‐back pain

When we combined the results from seven studies (645 women) that compared any land‐based exercise with usual prenatal care, exercise interventions (lasting from five to 20 weeks) improved women's levels of low‐back pain and disability.

Pelvic pain

There is less evidence available on treatments for pelvic pain. Two studies found that women who participated in group exercise and received information about managing their pain reported no difference in their pelvic pain than women who received usual prenatal care.

Low‐back and pelvic pain

The results of four studies combined (1176 women) showed that an eight‐ to 12‐week exercise program reduced the number of women who reported low‐back and pelvic pain. Land‐based exercise, in a variety of formats, also reduced low‐back and pelvic pain‐related sick leave in two studies (1062 women).

However, two other studies (374 women) found that group exercise plus information was no better at preventing either pelvic or low‐back pain than usual prenatal care.

There were a number of single studies that tested a variety of treatments. Findings suggested that craniosacral therapy, osteomanipulative therapy or a multi‐modal intervention (manual therapy, exercise and education) may be of benefit.

When reported, there were no lasting side effects in any of the studies.

Quality of the evidence and conclusions

There is low‐quality evidence suggesting that exercise improves pain and disability for women with low‐back pain, and moderate‐quality evidence that exercise results in less sick leave and fewer women reporting pain in those with both low‐back and pelvic pain together. The quality of evidence is due to problems with the design of studies, small numbers of women and varied results. As a result, we believe that future studies are very likely to change our conclusions. There is simply not enough good quality evidence to make confident decisions about treatments for these complaints.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care.

| Low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant women with back pain Intervention: low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual prenatal care | Any exercises + usual prenatal care | |||||

| Pain intensity measured by a number of different measurements; lower score = better. Follow‐up was measured between 8 and 24 weeks after randomisation across studies. Treatments varied from 5 to 20 weeks in duration. | The mean pain intensity in the control groups was 16.14 | The mean pain intensity in the intervention groups was 0.64standard deviations lower

(1.03 to 0.25 lower) (SMD ‐0.64, 95% CI ‐1.03 to ‐0.25; participants = 645; studies = 7) |

SMD ‐0.64, 95% CI ‐1.03 to ‐0.25 |

645 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | A standard deviation of 0.64 lower represents a moderate difference between groups, and may be clinically relevant. However, there was considerable clinical heterogeneity amongst the participants, interventions and outcome measures. |

| Disability measured by Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index; lower score = better. Follow‐up was measured from 5 to 12 weeks after randomisation across studies. Treatments varied from 5 to 8 weeks in duration. | The mean disability in the control groups was 26.64 | The mean disability in the intervention groups was 0.56standard deviations lower (0.89 lower to 0.23 higher) | SMD ‐0.56; 95% CI ‐0.89 to ‐0.23 | 146 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | A standard deviation of 0.56 lower represents a moderate difference between groups and may be clinically relevant. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the mean control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Poor or no description of randomisation process, allocation concealment, or blinding of research personnel in most of the studies in the meta‐analyses. 2 One study reported results in the opposite direction. 3 Imprecision (< 400 participants).

4 The assumed risk was calculated by measuring the mean pain intensity and the mean disability for the control groups.

Summary of findings 2. Pelvic + low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care.

| Pelvic + low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant women with, or at risk of developing, pelvic and back pain Intervention: pelvic + low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk (moderate risk population)3 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual prenatal care | Any exercises + usual prenatal care | |||||

| Number of women who reported pain on Visual Analogue Scale. Follow‐up was measured immediately after the intervention. Treatments ran from 8 to 12 weeks in duration. | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.45 to 0.97) | 1176 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | mean reduction of 34% across studies | |

| 708 per 1000 | 467 per 1000 (318 to 686) | |||||

| Number of women who reported LBPP‐related sick leave. Follow‐up was measured immediately after the intervention, which ran for 12 weeks. | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.62 to 0.94) | 1062 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | mean reduction of 24% across studies | |

| 288 per 1000 | 219 per 1000 (178 to 270) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 There was a mix of potential biases among the four studies: no allocation concealment (1); no blinding of research personnel (all); poor/no description of drop‐outs, co‐interventions and baseline inequality (mixed). 2 No blinding of research personnel; poor description of attrition; some differences in co‐interventions.

3 Moderate risk population chosen as the assumed risk because studies included pregnant women who did not have serious, systemic morbidities and entered at different points of their pregnancies, with varying levels of pain and disability.

Background

Description of the condition

Low‐back pain (LBP) and pelvic pain (PP) are common during pregnancy and tend to increase as pregnancy advances; in some cases, the pain radiates into the buttock, leg and foot. However, much still remains unclear about these very distinct but related conditions (Vermani 2010; Vleeming 2008). For many women, pain can become so severe that it interferes with ordinary daily activities, disturbs sleep and contributes to high levels of sick leave (Kalus 2007; Mogren 2006; Sinclair 2014; Skaggs 2007). Global prevalence is reported to range from 24% to 90%, in part, because there is currently no universally recognised classification system for the condition (Vermani 2010; Vleeming 2008). A prospective study of 325 pregnant women from the Middle East found that almost two‐thirds reported LBP, PP or both, during their current pregnancy (Mousavi 2007), with similar proportions reported by a sample of pregnant women (N = 599) in the United States (Skaggs 2007). Relapse rates are high in subsequent pregnancies (Mogren 2005; Skaggs 2007), and a postpartum prevalence of 24.7% (range 0.6% to 67%) (Wu 2004) underlines the importance of developing effective treatment programmes for this condition. Despite these figures, it is estimated that over 50% of women receive little or no intervention from healthcare providers (Greenwood 2001; Sinclair 2014; Skaggs 2007). These numbers suggest that more studies are needed to establish the underlying aetiology and pathogenesis of the conditions (Miquelutti 2013; Mørkved 2007). Current theories include: altered posture with the increased lumbar lordosis (exaggerated curvature of the lower spine) necessary to balance the increasing anterior weight of the womb, and inefficient neuromuscular control (Vleeming 2008). Several risk factors have also been identified, including increased weight during pregnancy, previous history of LBP and low job satisfaction (Albert 2006; Vleeming 2008).

Whilst LBP and PP may occur together during pregnancy, PP (posterior pain arising from the region of the sacroiliac joints, anterior pain from the pubic symphysis, or both) can often occur on its own, along with residual symptoms postpartum. A follow‐up to a cohort study of 870 pregnant women with PP found that 10% still experienced moderate or severe pain 18 months after delivery, and were seriously hindered in more than one activity (Rost 2006). Estimates of the prevalence of pregnancy‐related PP vary (depending on the type of study, diagnostic criteria and precision of identifying the pain), however, the best evidence suggests a point prevalence of 20% (Vleeming 2008). Van de Pol 2007 also reported that, whilst prognosis was generally good, those women reporting PP were less mobile than those reporting LBP only, and experienced more co‐morbidity and depressive symptoms; these findings are supported by a recent review (Vermani 2010). The need for a uniform terminology in order to promote research and management of these conditions is widely recognised. There are a number of tests validated for distinguishing LBP from PP; Vermani 2010 and Vleeming 2008 provide details of these tests.

Description of the intervention

European guidelines recommend that LBP (Airaksinen 2006) and PP (Vleeming 2008), are managed by providing adequate information and reassurance to patients that it is best to stay active, continue normal daily activities and work if possible, and by offering individualised exercises where appropriate. Similarly, prenatal practitioners in the United Kingdom and Nordic countries give women information about how to manage LBP, PP or both during their pregnancy and may refer them to physiotherapy for a more specific treatment programme. However, in the United States, women are taught that LBP is a normal part of pregnancy. Interventions that have been used to date to help manage the pain include exercises, frequent rest, hot and cold compresses, abdominal or pelvic support belts, massage, acupuncture, chiropractic, aromatherapy, relaxation, herbs, yoga, Reiki, paracetamol, and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (Sinclair 2014; Vermani 2010).

For this review, we conducted a broad search for studies that assessed the effects of any intervention that prevented or treated LBP, PP, or a combination of both for women at any stage of their pregnancy. We identified studies investigating the effects of: exercise (land‐ or water‐based), pelvic belts, osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMT), spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), neuro emotional technique (NET), craniosacral therapy (CST), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), kinesiotaping (KT), yoga, acupuncture, acupuncture plus exercises, and a multi‐modal approach incorporating manual therapy, exercise and education.

How the intervention might work

Exercise (land‐ or water‐based)

Exercise therapy is a management strategy that is supervised or 'prescribed' and encompasses a group of interventions ranging from general physical fitness or aerobic exercise, to muscle strengthening, various types of flexibility/stretching or progressive muscle relaxation exercises. It is further defined as any program in which, during the therapy sessions, the participants were required to carry out repeated voluntary dynamic movements or static muscular contractions (in each case, either 'whole‐body' or 'region‐specific' (Cochrane Back Review Group). Regular exercise can have both physical and psychological benefits, depending on the content of each programme, and the individual’s adherence (ACSM 2006). The exercises recommended for pregnancy‐related LBP are similar to those used for non‐specific LBP, with minor modifications, and are thought to have a similar mechanism of action (Vermani 2010).

Yoga

Yoga is a form of complementary and alternative medicine that incorporates a fluid transition through a number of poses (Asanas), to promote improvements in joint range of motion, flexibility, muscular strength and resistance, balance, concentration and self‐confidence, and a series of breathing exercises (Pranayamas) that facilitate mental relaxation and introspection (Martins 2014).

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR)

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) aims to relax muscles, reduce stress responses and decrease pain sensations. The technique involves deep breathing and progressive relaxation of major muscle groups, which promotes systematic relaxation (McGuigan 2007).

Manual therapy (SMT, OMT, CST, NET)

Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) is defined as a high velocity thrust performed to a joint beyond its restricted range of movement. Spinal mobilisation involves low‐velocity, passive movements within or at the limit of joint range (Cochrane Back Review Group). Most studies do not make a clear distinction between these two, because in clinical practice, these two techniques are often part of a 'manual therapy package', which may also include soft tissue/myofascial release. Manual therapy is thought to influence the spinal ‘gating’ mechanism and the descending pain suppression system at spinal and supraspinal levels to decrease pain. In addition, it is thought to return a vertebra to its normal position or restore lost mobility (Maigne 2003).

Osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMT) is a hands‐on, whole body approach to diagnose, treat, and prevent illness or injury, during which the osteopathic physician moves muscles and joints using techniques including stretching, gentle pressure and resistance (American Osteopathic Association).

Craniosacral therapy (CST), like OMT, is a hands‐on, whole body approach using light touch to release tension build‐up in different areas of the body and mind. For LBP and PP, CST techniques can be used to release tension build‐up in the connecting fascia, ligaments and muscles of the low‐back and pelvis, promoting a feeling of relaxation and enhanced body‐awareness. Other experiences reported include: sense of ease; warmth and tingling sensations, feeling accepted, a sense of harmony and peace, a feeling of letting go, feeling balanced, and increased energy (Craniosacral Therapy UK).

Neuro emotional technique (NET) is a mind‐body technique that combines relaxed breathing and visualisation with manual adjustment of the spinal levels that innervate the organ thought to be disturbing the body's balance of yin and yang. The underlying theory is that pain is caused by neurological imbalances related to the physiology of unresolved stress, therefore, by finding and removing the imbalances, the symptoms can be resolved (Bablis 2008; Neuro Emotional Technique; Peterson 2012a).

Acupuncture, alone or with exercises

Acupuncture is needle puncture at classical meridian points, aimed at promoting the flow of ‘Qi’ or energy. The acupuncturist must avoid certain acupuncture points in pregnancy that supply the cervix and uterus (which have been used to induce labour), but the technique in general is considered to be safe (Moffatt 2013; Vermani 2010). Needles may be stimulated manually or electrically. Acupuncture is thought to stimulate the body’s own pain relieving opioid mechanisms (Lin 2008). Placebo or sham acupuncture is needling of traditionally unimportant sites, superficial insertion or non‐stimulation of the needles once placed. There is some evidence that sham acupuncture may produce similar results to real acupuncture, raising the possibility that the effect of acupuncture may be a result of the stimulation of pressure receptors, regardless of their location (Field 2008).

Multi‐modal approach, including manual therapy, exercise and education

A combination of aspects of manual therapy and exercise, along with education that includes information about correct posture, relaxation techniques (Vermani 2010), instructions to keep the knees together and bent when turning in bed, and to avoid activities such as jarring, bouncing and stretching joints to their extreme (Lile 2003; Mens 2009).

Pelvic belts

Pelvic belts are a form of lumbar or pelvic support that can help to: (1) correct deformity; (2) limit spinal motion; (3) stabilise the lumbar spine and/or pelvis; (4) reduce mechanical loading; and (5) provide miscellaneous effects such as massage, heat or placebo. They may be made of flexible or rigid materials (Cochrane Back Review Group). Mens 2006 suggests that pelvic belts may stimulate the action of the corset muscle around the tummy and stabilising muscles of the spine along with the pelvic floor muscles.

Kinesio tape

Kinesio tape is an elastic therapeutic tape used for treating sports injuries and a variety of other disorders. Kinesiotaping (KT) techniques were developed by a Chiropractor, Dr Kenso Kase, in the 1970s. It is claimed that KT supports injured muscles and joints and helps relieve pain by lifting the skin and allowing improved blood and lymph flow (Williams 2012).

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation is a therapeutic non‐invasive modality, which is primarily used for pain relief. It consists of electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves via skin surface electrodes, typically placed over the painful area (Cochrane Back Review Group). A variety of TENS applications can be used depending on patient comfort and nerve accommodation, all with the aim of inhibiting pain transmission via the activation of the inhibitory interneurons in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord dorsal horn, and/or via the body's descending pain suppression system.

Why it is important to do this review

The number of new studies investigating the effectiveness of interventions for preventing and treating LBP and PP during pregnancy is increasing rapidly. The most recent update of this review was published in 2013, therefore, in order to appropriately reflect the current evidence available and inform decisions about the care of pregnant women with these conditions, it was essential to update this review again.

Objectives

To update the evidence assessing the effects of any interventions used to prevent and treat LBP, PP and LBPP during pregnancy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated any intervention for preventing or treating LBP, PP and LBPP during pregnancy. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies (those which use techniques for allocating participants to groups that may be prone to bias), and cross‐over designs, as they are not considered a valid study design for Pregnancy and Childbirth reviews, since women's physical characteristics change rapidly during pregnancy.

Types of participants

Studies that included pregnant women at any point in their pregnancy who were at risk of developing, or suffering from LBP, PP or the two in combination as reported symptomatically by the women or diagnosed by clinicians using specific tests.

Types of interventions

Studies that examined any intervention intended to reduce the incidence or severity of LBP, PP or both during pregnancy. We did not put parameters on the types of interventions. We grouped the studies to allow us to examine interventions that specifically addressed LBP, PP or the two in combination. Under each population, we grouped the interventions under exercise, yoga, manual therapy, acupuncture, multi‐modal approach, pelvic belts, Kinesio tape and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), depending on the studies identified. Interventions were added to usual prenatal care and compared to usual prenatal care (in some studies referred to as 'no treatment'), or usual prenatal care plus another intervention.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that started interventions and measured outcomes at least once post treatment during pregnancy. We excluded studies that diagnosed LBP, PP or LBPP, identified LBP, PP or LBPP as intermediate or proxy outcomes only, started interventions prior to pregnancy but measured the LBP, PP or LBPP during pregnancy, or started the study during pregnancy when their goal was to assess postpartum outcomes, and therefore the only measurements conducted during pregnancy were baseline values.

Primary outcomes

We included outcomes that were measured with validated measurement tools and included women’s own rating of usefulness of a treatment, reduction of symptoms, participation in usual daily activities and adverse effects (reported by women and assessors) measured at the end of treatment, during pregnancy. If outcomes were measured by both women and assessors, we only used data provided by the women.

Pain intensity (pain levels).

Back‐ or pelvic‐related functional disability/functional status (ability to perform daily activities).

Days off work/sick leave.

Adverse effects for women and infants; as defined by trialist.

Secondary outcomes

We did not identify or analyse secondary outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (19 January 2015).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We also identified potential studies by searching the Trials Register of the Cochrane Back Review Group (CBRG) by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator, most recently on 19 January 2015, and by following up on studies that were listed as 'ongoing' in prior literature searches. The CBRG Trials Register is populated by the results of monthly electronic database searches (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Index to Chiropractic Literature), by handsearching selected journals and conference proceedings, by quarterly searches of CENTRAL and international healthcare guideline sources and by the results of specific searches and reference checks of included studies for individual reviews (Cochrane Back Review Group). Regular searches for ongoing studies of back and neck pain treatments are conducted in the U.S. National Institute of Health database of clinical trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, as well as via the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (ICTRP)

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of included studies and related systematic reviews (Airaksinen 2006; Anderson 2005; Ee 2008; Field 2008; Franke 2014; Richards 2012; Vermani 2010).

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For this update and the previous version of this review (Pennick 2013), the following methods were used for assessing all reports that were identified as a result of all searches. For methods used in previous versions of the review, see Pennick 2007.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed, for inclusion, all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We obtained the full text of any articles identified that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, or lacked sufficient information to make a decision. We made all final decisions for inclusion after reading the full‐text of the article. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third assessor.

Data extraction and management

We used the data abstraction form developed by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group to extract data. For eligible studies, both review authors independently extracted the data. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third assessor. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted the authors of the original reports to provide further details. For articles that were published in non‐English languages, we sought the assistance of individuals who were experienced in systematic reviews and fluent in the language of interest; where possible, we used Google Translate (Google Translate) to assist with the translations and then verified key results with our translators.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described, for each included study, the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias (e.g. study reports that participants were randomised but does not give details of the method used).

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described, for each included study, the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth, case record numbers);

unclear risk of bias (e.g. study does not report any concealment approach, or only states that a list or table was used).

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described, for each included study, the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and whether reasons were given, and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants). We also noted if missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the study authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; greater than 20% drop‐out; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure from intervention received, compared to that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described, for each included study, how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described, for each included study, any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed other bias as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, assuming there are adequate data, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using GRADE

We assessed the quality of the overall body of evidence for all primary outcomes for all comparisons, using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE Handbook. We also included 'Summary of findings' tables for the following two comparisons for which we had sufficient data to conduct meta‐analyses.

Comparison 1: Low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care ('Summary of findings' table 1)

Pain intensity measured after end of treatment by a number of different measurements (lower score = better)

Disability measured after end of treatment by Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire and Oswestry Disability index (lower score = better)

Comparison 7: Pelvic + low‐back pain: any exercises + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care ('Summary of findings' table 2)

Number of women who reported pain on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

Number of women who reported LBP/PP‐related sick leave

GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool was used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence is downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risks of bias: indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias. See Appendix 1 for further explanation of the quality of the evidence.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between studies. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) for studies that measured the same outcome, but used different methods. We presented both summary results with 95% CIs. As in the 2013 update, we used Cohen's three levels to guide our classification of the estimates of effect as small (< 0.5), medium (0.5 to < 0.8) or large (≥ 0.8; Cohen 1988). To determine if an estimate of effect was clinically important, we were guided by the work conducted in LBP research; a 30% change in pain (VAS/NRS (numerical rating scale)) was considered clinically important (Ostelo 2008), and two to three points on the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), or 8% to 12% on the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (Bombardier 2001).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not include any cluster‐RCTs in this review.

If we identify cluster‐randomised trials in future updates, we will include them in the analyses along with individually‐randomised studies. We will adjust their sample sizes or standard errors using the methods described in the Handbook, Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6 (Higgins 2011), using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the study (if possible), from a similar study or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised and individually‐randomised studies, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Other unit of analysis issues

Studies in Pregnancy and Childbirth may include outcomes for multiple pregnancies. If we identify studies with multiple pregnancies in future updates of this review, we will outline analytical methods as per the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Methodological Guidelines and Handbook sections 9.3.7 and 16.3 (Higgins 2011).

If we identify studies with more than two treatment groups, we will divide the control group by the number of intervention groups if data from all groups are used in the same meta‐analysis, as per Handbook Section 16.4.7 (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included in analyses, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis (seeSensitivity analysis). For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each study was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

If data were unclear or missing, we contacted the authors of the included studies for further details.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics provided in RevMan. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. We noted potential sources of differences between studies where analyses had high heterogeneity. In future updates, with sufficient data, we plan to explore heterogeneity by subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases, such as publication bias, using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). Had it been reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect, i.e. where studies were examining the same intervention, and the studies’ populations and methods were judged to be sufficiently similar, we would have used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data.

Since there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between studies, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary when an average treatment effect across studies was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects, and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between studies. Where the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine studies. When we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Although we identified heterogeneity in gestational age, duration and content of exercise regimens across studies, we did combine data with random‐effects meta‐analyses to determine the overall estimate of effect for any type of exercise intervention for women with LBP and those who had both LBP and PP. We were unable to investigate subgroup analyses due to insufficient data. For outcomes with high heterogeneity, we discussed possible sources of differences between studies in the text where results are reported.

Had we had sufficient data, we would have carried out the following subgroup analyses.

Gestational age by trimester per comparison and outcome

Different durations of interventions per comparison and outcome

Different content of interventions per comparison and outcome

Had we had sufficient data, we would have examined the following outcomes in subgroup analyses.

Pain intensity (pain levels)

Low‐back‐ or pelvic‐related functional disability/functional status (ability to perform daily activities)

Days off work/sick leave

We would further assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014), reporting the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of study quality, assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, by excluding studies with a high or unclear risk of bias from the analyses in order to assess whether this made any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The review completed in 2002 (Young 2002) contained three studies: two examined interventions for women with LBP (Kihlstrand 1999; Thomas 1989), one examined an intervention for a mixed population with both LBP and PP (Wedenberg 2000). One study was excluded because it used a quasi‐randomised sequence generation.

The first update of the review (Pennick 2007) included eight studies (1305 women), described in nine publications. Seven were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and the eighth used a cross‐over design. The literature search, updated to February 6, 2006 had identified 11 potentially relevant reports; five RCTs, described in six reports, were included: two studies examined women with LBP (Garshasbi 2005; Suputtitada 2002), one examined women with PP (Elden 2005), and two more examined a mixed population with LBP and PP (Kvorning 2004; Martins 2005); two studies were identified as ongoing, and three were excluded because they used a quasi‐randomised study design.

The 2013 update (Pennick 2013) included 26 studies, described in 30 reports. The literature search, updated to July 18, 2012, identified 47 potentially relevant reports from both the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth and the Cochrane Back Review Groups' Trials Registers.

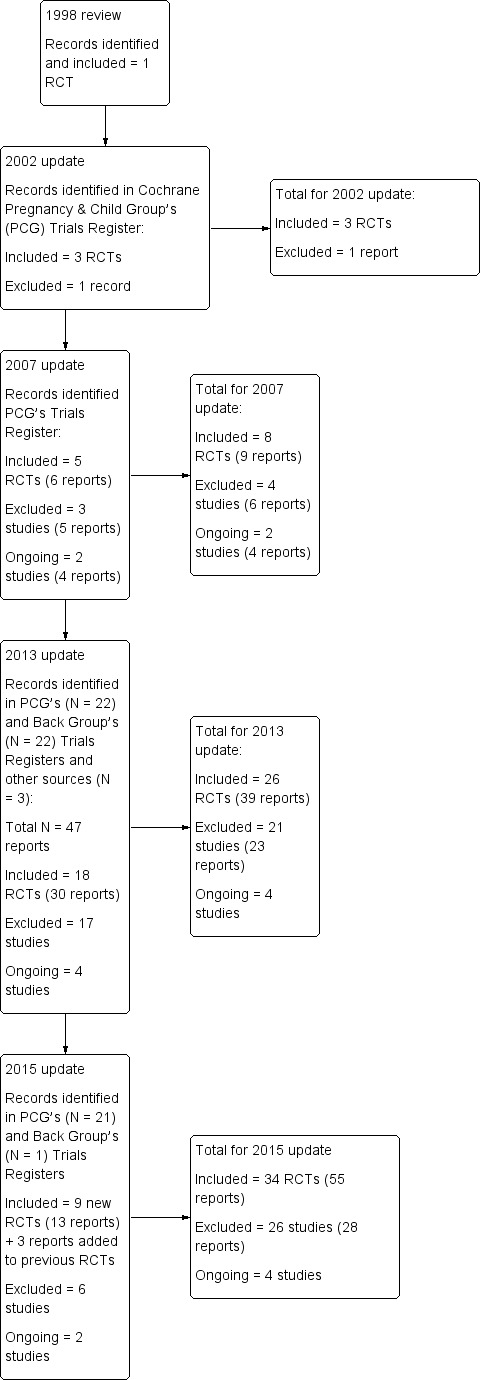

This 2015 update identified 19 potentially relevant reports from the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Review Group's Trials Register to 31 August 2014 and two reports that were identified through personal searching by the co‐author (VEP) to follow up on abstracts and reports of ongoing studies to 14 October 2014. One more report (Gundermann 2013) was identified by scanning the references in a recent systematic review (Franke 2014), identified by the Cochrane Back Review Group's Trials register to 19 January 2015 (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included nine new RCTs in this update, reported in 13 publications: three were reported in multiple publications: (Kordi 2013; Martins 2014; Miquelutti 2013); six were published in single reports (Akmese 2014; Elden 2013; Gundermann 2013; Hensel 2014; Kaya 2013; Keskin 2012). Four reports were ongoing studies (Freeman 2013; Greene 2009; Moholdt 2011; Vas 2014).

This review now includes 34 RCTs examining 5121 pregnant women, aged between 16 to 45 years.

Population

Gestational age, when reported, ranged from 12 to 38 weeks. Fifteen RCTs examined women with low‐back pain (LBP) (N = 1847 randomised; 1687 analysed): Akmese 2014; Bandpei 2010; Garshasbi 2005; Gil 2011; Gundermann 2013; Hensel 2014; Kalus 2007; Kashanian 2009; Kaya 2013; Keskin 2012; Kihlstrand 1999; Licciardone 2010; Peterson 2012; Sedaghati 2007; Suputtitada 2002); six looked at pelvic pain (PP) (N = 889 randomised; 791 analysed; Depledge 2005; Elden 2005; Elden 2008; Elden 2013; Kordi 2013; Lund 2006); and 13 studies examined women with pelvic‐ and LBP (LBPP), reported separately or together (N = 2385 randomised; 2160 analysed; Eggen 2012; Ekdahl 2010; George 2013; Kluge 2011; Kvorning 2004; Martins 2005; Martins 2014; Miquelutti 2013; Mørkved 2007; Peters 2007; Stafne 2012; Wang 2009a; Wedenberg 2000).

Interventions

Seven studies investigated the effects of exercise on LBP, either on land (N = 713 randomised; 645 analysed; Bandpei 2010; Garshasbi 2005; Gil 2011; Kashanian 2009; Miquelutti 2013; Sedaghati 2007; Suputtitada 2002), or in water (N = 258 randomised; 241 analysed; Kihlstrand 1999). In each study, exercise was added to usual prenatal care and compared with prenatal care alone. Akmese 2014 (N = 73 randomised; 66 analysed) compared progressive muscle relaxation with music (PMR) added to usual prenatal care with prenatal care plus instructions to rest twice a day. Peterson 2012 (N = 57 randomised; 50 analysed) compared the effects of exercise, spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and neuro emotional technique (NET), and Kalus 2007 (N = 115 randomised; 94 analysed) compared the effects of the BellyBra against those of Tubigrip. Kaya 2013 (N = 29 randomised and analysed) compared kinesiotaping (KT) with exercise, and Keskin 2012 (N = 88 randomised; 79 analysed) investigated the effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) compared with acetaminophen, exercise or usual prenatal care. Three further studies (Gundermann 2013; Hensel 2014; Licciardone 2010, N = 587 randomised; 585 analysed) added osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMT) to usual prenatal care and compared it with sham ultrasound (sham US) added to usual prenatal care or usual prenatal care by itself.

Of the six studies investigating pregnant women with PP, Depledge 2005 (N = 90 randomised; 87 analysed) compared the effects of two types of pelvic support belt (rigid versus non‐rigid) added to exercise with exercise alone. Elden 2013 (N = 123 randomised and analysed) examined the effects of craniosacral therapy (CST) added to, and compared with, usual prenatal care. Elden 2008 and Lund 2006 (N = 185 randomised; 155 analysed) compared different acupuncture techniques, and Elden 2005 (N = 386 randomised; 330 analysed) added acupuncture or stabilising exercises to, and compared them with, usual prenatal care. Kordi 2013 (N = 105 randomised; 96 analysed) added a lumbo‐pelvic belt to information about managing PP, and compared this to exercise plus information, or information alone. Miquelutti 2013 compared a Birth Preparation Program (incorporating exercise and information) with usual prenatal care and included women with LBP and PP who were analysed separately. For women with PP, 29 were randomised; 45 analysed, i.e. more reported PP at the end of the study.

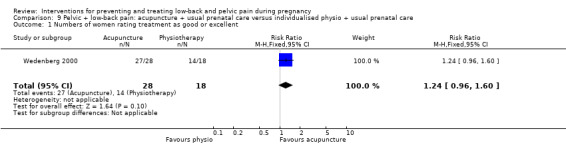

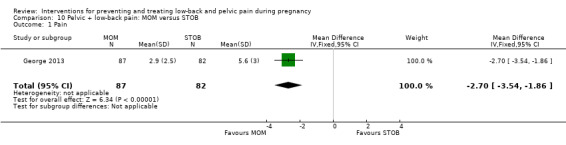

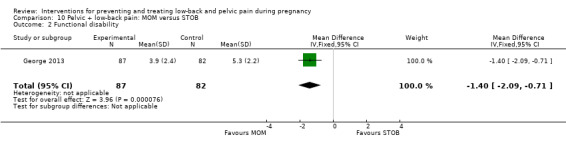

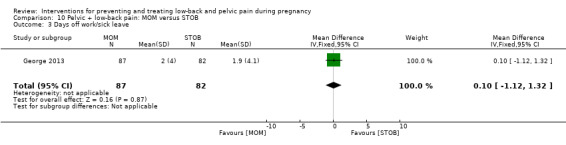

Women who had both LBP and PP, reported separately or together, were given a range of exercise interventions (Eggen 2012; Kluge 2011; Martins 2005; Mørkved 2007; Stafne 2012; N = 1532 randomised; 1390 analysed), or exercises as part of a yoga program (Martins 2014; N = 60 randomised; 45 analysed), OMT (Peters 2007; N = 60 randomised; 57 analysed), a multi‐modal intervention that included manual therapy, exercise and education (George 2013; N = 169 randomised and analysed); or acupuncture alone (Ekdahl 2010; Kvorning 2004; Wang 2009a; Wedenberg 2000; N = 359 randomised; 302 analysed).

The control groups used were generally described as usual prenatal care. The more recent acupuncture studies used sham acupuncture as a control (Elden 2008; Wang 2009a), tested the optimal time to start treatment with acupuncture (Ekdahl 2010), examined different depths of acupuncture stimulation (Lund 2006), or its relative effectiveness against physiotherapy (Wedenberg 2000). Relative effectiveness was examined between SMT and NET (Peterson 2012) and between two types of pelvic belts (Depledge 2005; Kalus 2007). Sham US was used as a control against OMT (Hensel 2014; Licciardone 2010), and exercise as a control against either KT (Kaya 2013) or a lumbo‐pelvic belt (Kordi 2013).

All studies looked at treatment; two studies also looked at interventions that may prevent LBP (Licciardone 2010; Sedaghati 2007) and four explored what may prevent LBPP (Eggen 2012; Miquelutti 2013; Mørkved 2007; Stafne 2012).

See tables of Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies for further details.

Excluded studies

For this update, we excluded five studies after review of the full‐text: Hensel 2013; McCullough 2014; Moffatt 2014; Thomas 1989; Torstensson 2013. Thomas 1989 used a cross‐over design to investigate the effects of different pillows on LBP, and this study had been included in this review up to and including the 2013 update. There were always concerns about the appropriateness of including the study due to study design and methods of analyses. The review authors decided to exclude this study in the 2015 update because of these concerns.

See table of Characteristics of excluded studies for details about reasons for exclusion for this and previous updates.

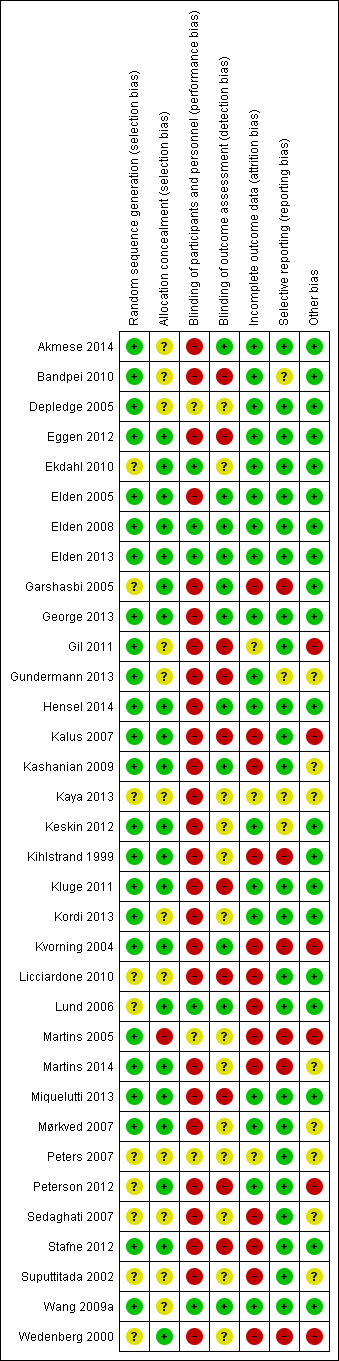

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, the risks of bias were high, raising concerns about the confidence we could put in the estimates of effect. See Figure 2 for a summary of these risks of bias in each study; see the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies for details.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Of the 34 studies included in this update, 24 (71%) adequately reported on the method of randomisation employed, despite the fact that all were identified as 'randomised controlled trials'; 21 (62%) studies adequately reported on an appropriate method of allocation concealment. This represents an improvement when compared to the last update, in which only 13 out of 26 studies (50%) adequately reported on the method of randomisation, and 14 out of 26 studies (54%) on the method of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Blinding is very difficult to carry out in non‐pharmacological studies, especially when symptoms are the outcomes of interest; nonetheless, lack of blinding of research personnel and participants still has the potential to introduce bias. Five studies (15%) reported that the providers and the participants were blinded, while 11 (32%) reported that the outcome assessors were blinded. Of these, only two reduced the bias for blinding by asking all participants if they felt the treatment they had received was credible (Elden 2013; Wang 2009a).

Incomplete outcome data

Eighteen studies (53%) reported that the women were analysed in the groups to which they were randomised; most of the studies only analysed data from those who completed the study, although two (Licciardone 2010; Peterson 2012) imputed missing data in order to present a full data set. Attrition rates ranged from zero to 33% (Lund 2006). In seven of the study reports, it was difficult to determine the exact numbers randomised and withdrawn, reasons for the withdrawal and the group membership of those who withdrew. Seventeen (50%) of the more recent publications included a CONSORT flow chart that traced the enrolment, randomisation, follow‐up and analysis of participants (Schulz 2010).

Selective reporting

We did not specifically search for protocols to determine what outcomes had been planned, however five studies were identified from study registration databases during the literature search for the 2013 update (Eggen 2012; Elden 2008; Kalus 2007; Licciardone 2010; Wang 2009a); four studies were identified as ongoing for this update (Freeman 2013; Greene 2009; Moholdt 2011; Vas 2014), and two studies that were identified as 'ongoing' in the last update were included as completed studies for this update (Abolhasani 2010 (included study Kordi 2013); Hensel 2008 (included study Hensel 2014)). Only 19 studies (compared to 17 listed in the 2013 update) provided data on the outcomes they had identified in the description of the methods in either the publication or the study registration report, in a form that enabled us to include them in analyses; for one study, we calculated the end of treatment score and standard deviation using the RevMan calculator to enable us to include the data (Bandpei 2010).

Other potential sources of bias

Fourteen studies were either at high (N = 6) or unclear (N = 8) risk of bias for this section. Four of these were dissimilar at baseline in important prognostic characteristics (Gil 2011; Martins 2005; Peterson 2012; Wedenberg 2000), despite the fact that Gil 2011; Martins 2005 described adequate randomisation techniques; 13 reported very different co‐interventions between the groups, did not describe co‐interventions, reported co‐interventions that would make it difficult to determine the real effect of the intervention, or did not describe compliance (Gil 2011; Gundermann 2013; Kalus 2007; Kashanian 2009; Kaya 2013; Kvorning 2004; Martins 2005; Martins 2014; Mørkved 2007; Peters 2007; Sedaghati 2007; Suputtitada 2002; Wedenberg 2000). Three of the above studies were either abstracts or short communications, for which we were unable to obtain the full reports (Gundermann 2013; Kaya 2013; Peters 2007).

Effects of interventions

Low‐back pain (LBP)

Comparison 1. Low‐back pain: any exercise + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care

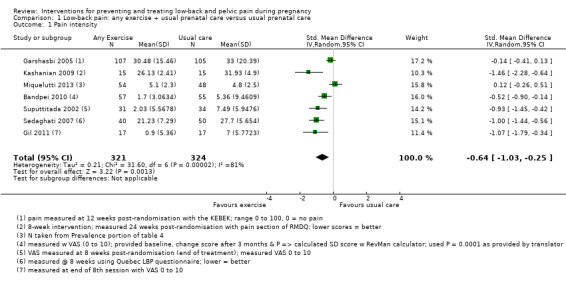

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, inconsistent results) from seven studies (Bandpei 2010; Garshasbi 2005; Gil 2011; Kashanian 2009; Miquelutti 2013; Sedaghati 2007; Suputtitada 2002; N = 645 analysed) that any land‐based exercise, added to usual prenatal care, significantly reduced pain (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.03 to ‐0.25; participants = 645; studies = 7; I² = 81%; Analysis 1.1) more than usual prenatal care by itself. A SMD of 0.64 represents a moderate difference between groups. Heterogeneity was high for this analysis, and pain was measured between eight and 24 weeks after randomisation across the included studies. The gestation at which pain was measured may be one source of heterogeneity; elements of the exercise regimens may be another. When we conducted a sensitivity analysis, based on the 'Risk of bias' domain of allocation concealment, heterogeneity was not improved by excluding studies with unclear risk of bias (Tau² = 0.23; I² = 83%). In both Gil 2011 and Suputtitada 2002, it appeared that the standard deviation (SD) reported in the study report was actually a standard error (SE), however, after discussion with the statisticians, we used the published data in the meta‐analysis. We are concerned about the accuracy of reporting in these studies.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Low‐back pain: any exercise + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care, Outcome 1 Pain intensity.

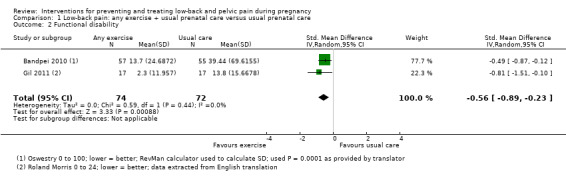

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision) from two studies (Bandpei 2010; Gil 2011; N = 146 analysed) that land‐based exercise also reduced functional disability (SMD ‐0.56; 95% CI ‐0.89 to ‐0.23; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.2) more than usual prenatal care by itself (Table 1). Again, we recalculated the SD stated in Gil 2011 because it appeared to be a SE.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Low‐back pain: any exercise + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care, Outcome 2 Functional disability.

All but one of the studies (Miquelutti 2013) reported effects in the same direction, so land‐based exercise seemed to reduce pain and functional disability, but there is considerable uncertainty about the size of the effect, due to the risks of bias in the included studies and concern about the accuracy of reporting in Bandpei 2010, Gil 2011 and Suputtitada 2002. See further details in the Discussion. None of the interventions, gestational ages or outcomes was sufficiently similar, nor were sufficient data provided to allow us to perform a meta‐analysis to determine the estimate of effect of any specific exercise for a specific group of pregnant women.

None of the studies included in this comparison reported the primary outcome of days off work/sick leave. Four studies (Garshasbi 2005; Gil 2011; Miquelutti 2013; Suputtitada 2002) reported that no adverse effects occurred as a result of the intervention.

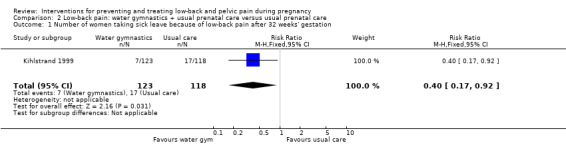

Comparison 2. Low‐back pain: water gymnastics + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Kihlstrand 1999; N = 241 analysed) that water‐based exercise, added to usual prenatal care, reduced LBP‐related sick leave more than usual prenatal care by itself; women who exercised were 60% less likely to take sick leave due to their LBP at 32 weeks' gestation (risk ratio (RR) 0.40; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.92; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Low‐back pain: water gymnastics + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care, Outcome 1 Number of women taking sick leave because of low‐back pain after 32 weeks' gestation.

This study reported the primary outcome of pain intensity on a graph of mean values and did not report on the other primary outcome of functional disability. No adverse effects occurred as a result of the intervention.

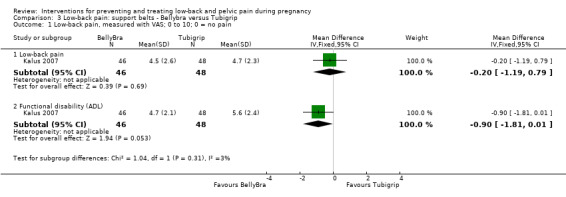

Comparison 3. Low‐back pain: usual prenatal care + support belts ‐ Bellybra versus Tubigrip

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Kalus 2007; N = 94 analysed) that there was no significant difference between the BellyBra's and the Tubigrip's ability to relieve pain (mean difference (MD) ‐0.20; 95% CI ‐1.19 to 0.79) or to decrease functional disability (activities of daily living) (MD ‐0.90; 95% CI ‐1.81 to 0.01; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Low‐back pain: support belts ‐ Bellybra versus Tubigrip, Outcome 1 Low‐back pain, measured with VAS; 0 to 10; 0 = no pain.

This study did not report the primary outcomes of days off work/sick leave, or adverse effects.

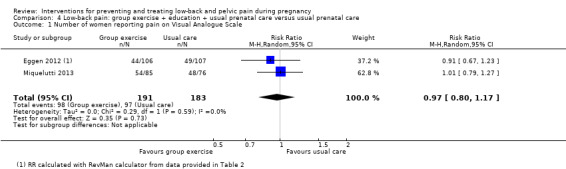

Comparison 4. Low‐back pain: group exercise + education + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from two studies (Eggen 2012; Miquelutti 2013; N = 374 analysed) that group exercise added to information about how to manage pregnancy‐related LBP was no better at preventing LBP than usual prenatal care alone (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.17; Analysis 4.1). There were no adverse effects resulting from the interventions in either study.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Low‐back pain: group exercise + education + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care, Outcome 1 Number of women reporting pain on Visual Analogue Scale.

Eggen 2012 found no significant difference between groups for disability. Neither study reported the primary outcome of days off work/sick leave.

Additional results for low‐back pain

All results below were extracted directly from the papers as the presentation of results in each paper prevented pooling of data.

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) with music + usual prenatal care versus advice to rest + usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Akmese 2014; N = 66 analysed) that PMR, accompanied by music, significantly decreased pain more than lying down for the same amount of time each day. The study did not report the primary outcomes of functional disability, days off work/sick leave or adverse effects.

Manual therapy + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care

Four studies examined the effects of manual therapy, specifically: osteomanipulative therapy (OMT) (Gundermann 2013; Hensel 2014; Licciardone 2010), spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), or neuro emotional technique (NET) (Peterson 2012), which were compared with usual prenatal care alone or with another intervention.

There was moderate‐quality evidence (study design limitations) from one study (Hensel 2014; N = 400 analysed) that OMT added to usual prenatal care improved pain (effect size ‐7.11; 95% CI ‐10.30 to ‐3.93) and functional disability (effect size ‐2.25; 95% CI ‐3.18 to ‐1.32) significantly more than usual prenatal care alone, but not more than usual prenatal care plus placebo ultrasound (US). The paper did not specify the measure of treatment effect (i.e. MD or SMD), referring instead to 'effect size'. There were no adverse effects resulting from the interventions used in this study.

Low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from another study (Licciardone 2010; N = 144 analysed) also found no significant difference in pain relief (effect size 0.14; 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.53) or functional disability (effect size 0.35; 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.76) between usual prenatal care plus OMT and usual prenatal care plus placebo ultrasound. In further analysis of the same data, the authors concluded that OMT was more effective than usual prenatal care alone for preventing progressive functional disability as a result of LBP (RR 0.4; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.7). The paper did not specify the measure of treatment effect (i.e. MD or SMD), referring instead to 'effect size'. Adverse effects were reported as being similar across groups but no further detail was provided.

Low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from a third small study (Gundermann 2013; N = 41 analysed) concluded that OMT was more effective in reducing pain than usual prenatal care (between‐group difference of means 3.5; 95% CI 2.4 to 4.6). This study did not report on the other primary outcomes of functional disability, days off work/sick leave or adverse effects.

Low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Peterson 2012; N = 50 analysed) found that, while the majority of women in each of the groups (exercise, NET and SMT) improved in functional disability and pain, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups. Days off work/sick leave was not compared between groups before and after treatment, however the authors did state that they had measured sick leave due to pregnancy‐related LBP at the beginning of their study. Some post‐treatment soreness was reported in all groups but no adverse effects occurred as a result of the interventions.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Keskin 2012; N = 79 analysed) that TENS improved pain and functional disability significantly more than usual prenatal care. This study also included two additional active treatment groups (exercise; acetaminophen), which also resulted in significant pre‐ versus post‐treatment improvements in pain and functional disability when compared to usual prenatal care (pain/VAS P < 0.001; disability/RMDQ P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in these outcomes when acetaminophen was compared to exercise (pain/VAS P = 0.694; disability/RMDQ P = 0.506), despite the fact that baseline VAS scores (pain) were significantly higher in the TENS group (P = 0.004). There were no adverse effects resulting from TENS.

Keskin 2012 did not report on the primary outcome of days off work/sick leave.

Acetaminophen + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence from one study (Keskin 2012) as described above, that acetaminophen improved pain and functional disability (measured on the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)) significantly more than usual prenatal care. There was no significant difference in these outcomes, also noted above, when acetaminophen was compared to exercise.

Kinesiotaping (KT) + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care + exercise + acetaminophen

One abstract (Kaya 2013; N = 29 analysed) compared KT with exercise plus acetaminophen and reported that pain and functional disability were significantly lower in both groups, however, these outcomes improved more in the group that received KT (P < 0.001); insufficient information was available in the abstract to draw any further conclusions. The abstract did not report on the primary outcome of days off work/sick leave. There were no adverse effects resulting from the KT intervention.

Adverse effects

When reported, there were no serious adverse effects noted for either the mother or the neonate in any of the studies (Eggen 2012; Gil 2011; Garshasbi 2005; Hensel 2014; Kaya 2013; Keskin 2012; Kihlstrand 1999; Licciardone 2010; Miquelutti 2013; Peterson 2012; Sedaghati 2007; Suputtitada 2002). Women who participated in water‐based exercise did not develop any more urinary tract or uterine infections than those who received usual prenatal care (Kihlstrand 1999). There were no data reported on the (primary) preventative aspects of any of these interventions, although there was a sense that they may have prevented further development of pain and disability, and therefore may have had some secondary preventative consequences.

Pelvic pain (PP)

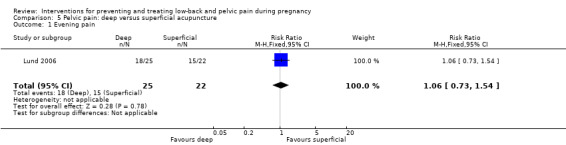

Comparison 5. Pelvic pain: deep acupuncture + usual prenatal care versus superficial acupuncture + usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Lund 2006; N = 47 analysed) that there was no significant difference in evening pain between women who received deep acupuncture and those who received superficial acupuncture (RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.54; Analysis 5.1). Data were not provided for the primary outcomes of functional disability, days off work/sick leave or adverse effects.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Pelvic pain: deep versus superficial acupuncture, Outcome 1 Evening pain.

Comparison 6. Pelvic pain: usual prenatal care + group exercise + education versus usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from two studies (Eggen 2012; Miquelutti 2013; N = 374 analysed) that group exercise added to information about how to manage pregnancy‐related PP was no better at preventing pain than usual prenatal care alone (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.23; Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Pelvic pain: group exercise + education + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care, Outcome 1 Number of women reporting pain on Visual Analogue Scale.

Neither study reported the primary outcome of days off work/sick leave. Eggen 2012 found no difference between groups for functional disability. No adverse effects occurred as a result of either intervention.

Additional results for pelvic pain

All results below were extracted directly from the papers as the presentation of results in each paper prevented pooling of data.

We were unable to pool the data from Elden 2005 and Elden 2008, since acupuncture was compared with different interventions in these two studies; data were extracted directly from the published reports.

Acupuncture + usual prenatal care versus sham acupuncture + usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Elden 2008; N = 108 analysed) that there was no significant difference in pain relief between acupuncture plus usual prenatal care and non‐penetrating sham acupuncture plus usual prenatal care (median evening pain on VAS = 36 and 41 respectively, P = 0.483); acupuncture plus usual prenatal care showed significant improvement in some daily functions, as measured using the Disability Rating Index (DRI), over non‐penetrating sham acupuncture plus usual prenatal care (median DRI 44 and 55 respectively, P = 0.001), which was further illustrated in the two groups by the number of women who worked regularly (28/57 (acupuncture) versus 16/57 (sham acupuncture), P = 0.041).

Acupuncture + usual prenatal care versus stabilising exercises + usual prenatal care or usual prenatal care alone

Elden 2005 (N = 330 analysed) examined the effects on PP of adding either acupuncture or stabilising exercises to usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care alone. There was moderate‐quality evidence (imprecision of effect estimates) that, after one week of treatment, those who received usual prenatal care reported significantly more intense evening PP than those who had received either acupuncture (difference of medians: 27; 25th to 75th percentiles 13.3 to 29.5; P < 0.001) or stabilising exercises (difference of medians:13; 25th to 75th percentiles 2.7 to 17.5; P = 0.0245). Those who received acupuncture reported significantly less intense evening PP than those who received stabilising exercises (difference of medians: ‐14; 25th to 75th percentiles ‐18 to ‐3.3; P = 0.0130). Data were not provided for the primary outcomes of disability or days off work/sick leave.

Rigid pelvic belts + exercise + usual prenatal care versus non‐rigid pelvic belt + exercise + usual prenatal care versus exercise + usual prenatal care

There was low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Depledge 2005; N = 87 analysed) that there was a significant reduction of average pain in the group that received exercise alone (31.8% reduction in pain) or exercise plus a rigid belt (29% reduction), and no significant pain reduction in the group that had exercise plus a non‐rigid belt (13% reduction); there were no data provided that compared results between groups. There was no significant difference between the three groups in functional disability.

Low‐quality evidence (study design limitations, imprecision of effect estimates) from another study (Kordi 2013; N = 96 analysed) suggested that the use of a non‐rigid lumbo‐pelvic belt significantly reduced pain (P < 0.001) and functional disability (P = 0.008) more than exercise at the final six‐week follow‐up.

In both of these studies belts and exercise were added to information about how to manage pregnancy‐related PP; both resulted in better outcomes than information alone. Neither study measured the other primary outcomes of days off work/sick leave or adverse effects.

Craniosacral therapy (CST) + usual prenatal care versus usual prenatal care

There was moderate‐quality evidence (imprecision of effect estimates) from one study (Elden 2013; N = 123 analysed) that the addition of CST to usual prenatal care significantly improved morning PP (P = 0.017) and functional disability (P = 0.016) more than usual prenatal care alone. There were no significant differences between groups in evening pain or days off work/sick leave.

Prevention ‐ Birth Preparation Program versus usual prenatal care