Abstract

Background:

Transferred emergency general surgery (EGS) patients constitute a highly vulnerable, acutely ill population. Guidelines to facilitate timely, appropriate EGS transfers are lacking. We determined patient- and hospital-level factors associated with interhospital EGS transfers, a critical first step to identifying which patients may require transfer.

Materials and methods:

Adult EGS patients (defined by American Association for the Surgery of Trauma ICD-9 diagnosis codes) were identified within the 2008–2013 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) (n=17,175,450). Patient- and hospital-level factors were examined as predictors of transfer to another acute care hospital with a multivariate proportional cause-specific hazards model with a competing risks analysis to assess the effect of risk factors for transfer.

Results:

1.8% of encounters resulted in a transfer (n=318,286). Transferred patients were on average 62 years old and most commonly had Medicare (52.9% [n=168,363]), private (26.7% [n=84,991]), or Medicaid insurance (10.7% [n=34,279]). 67.7% were white. The most common EGS diagnoses among transferred patients were related to hepatopancreatobiliary (n=90,989 [28.6%]) and upper gastrointestinal tract (n=60,088 [18.9%]) conditions. Most transferred patients (n=269,976 [84.8%]) did not have a procedure prior to transfer. Transfer was more likely if patients were in small (Hazard ratio [HR] 2.52, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 2.28–2.78) or medium (1.32, 1.21–1.44) versus large facilities, government (1.19, 1.11–1.28) versus private facilities, and rural (4.58, 3.98–5.27) or urban non-teaching (1.89, 1.70–2.10) versus urban teaching facilities. Patient-level factors were not strong predictors of transfer.

Discussion:

We identified that hospital-level characteristics more strongly predicted the need for transfer than patient-related factors. Consideration of these factors by providers as care is delivered in the context of the resources and capabilities of local institutions may facilitate transfer decision-making.

Introduction

Emergency general surgery (EGS) conditions, such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, and small bowel obstruction, constitute a large public health burden with more than 2.6 million hospitalizations per year totaling $28.4 billion in costs.1 The demand for EGS care is increasing amidst the “looming crisis” of a general surgeon shortage.2 Increased subspecialization, lifestyle demands, and reimbursement pressures have led to a smaller pool of general surgeons willing to provide emergency care.3–6 Gaps in the availability of emergency surgical care7 inherently promote the transfer of patients to facilities that can provide the care that is needed.

Outcomes among EGS patients who are transferred are poor. Transferred EGS patients experience more morbidity and mortality than directly admitted patients, even after adjusting for severity of illness.8–15 Among patients with major non-traumatic surgical emergencies, transferred patients experience higher mortality (4.9 vs 0.9%, p=0.04) and longer hospital stays (5–13 days vs 3–8 days, p<0.001) than their directly admitted counterparts.13 Among surgical intensive care unit (ICU) patients, interhospital transfer is a risk factor for ICU mortality (odds ratio [OR], 1.60; 95% confidence interval, 1.04 to 2.45; P=0.03).15

A better understanding of the current interhospital transfer system will allow for the identification of vulnerable sub-populations and potential interventions to improve the care provided to transferred EGS patients. Determining the factors that predict a patient needing to be transferred is one element of the system that has heretofore been understudied. Recognizing factors that predict transfer can allow providers to more readily identify patients with a high probability of being transferred and potentially minimize delays to definitive care. Using nationally representative data, this study identified predictors of the need to transfer an EGS patient to another acute care hospital. An improved understanding of the patient- and hospital-level factors associated with the decision to transfer will also provide critical insights to inform potential regionalization of EGS care in the future.

Methods

We analyzed the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to determine patient- and hospital-level factors associated with the transfer of emergency general surgery (EGS) patients to acute care hospitals. The NIS database was developed as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), is maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and is the largest source of all-payer hospital discharge information in the United States.16 NIS represents a systematic collection of discharge data from HCUP hospitals.17 Prior to 2012, the NIS database represented 100 percent of discharges from a sample of approximately 1,000 hospitals. Beginning with the 2012, the NIS database represents a fraction of discharges from across all HCUP hospitals.

The 2008–2013 NIS was queried for adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) admitted on a non-elective basis for emergency general surgery (EGS) conditions as determined by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma DRG international Classification of Diseases – 9th Revision criteria.18 As is consistent with previous studies and to focus our study on patients who were admitted for an EGS diagnosis and subsequently transferred, we only included patients who had an AAST EGS diagnosis code listed in the primary diagnosis field.19 EGS conditions, as defined by the AAST, encompass 309 unique ICD-9-CM codes and correspond to the following diagnosis groups:18,20

Resuscitation: acute respiratory failure, shock

General abdominal conditions: abdominal pain, abdominal mass, peritonitis, hemoperitoneum, retroperitoneal abscess

Intestinal obstruction: adhesion, incarcerated hernia, cancer, volvulus, intussusception

Upper gastrointestinal tract: upper gastrointestinal bleed, peptic ulcer disease, fistula, gastrostomy, small intestinal cancer, ileus, Meckel’s, bowel perforation, appendix

Hepatic-pancreatic-biliary: gallstones and related diseases, pancreatitis, hepatic abscess

Colorectal: lower gastrointestinal bleed, diverticular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, colitis, colonic perforation, megacolon, regional enteritis, colostomy/ ileostomy, hemorrhoid, perianal and perirectal fistula and infection, anorectal stenosis, rectal prolapse

Hernias: Inguinal, femoral, umbilical, incisional, ventral, diaphragmatic

Soft tissue: cellulitis, abscess, fasciitis, wound care, pressure ulcer, compartment syndrome

Vascular: ruptured aneurysm, acute intestinal ischemia, acute peripheral ischemia, phlebitis

Cardiothoracic: cardiac tamponade, empyema, pneumothorax, esophageal perforation

Others: tracheostomy, foreign body, bladder rupture

As it is not possible within the NIS database to track patients between hospital encounters, we excluded patients who had been transferred in from a different acute care hospital; thus, our cohort represents patients who are transferred for the first time in their course. As such, the data presented here represent information about the patient and hospital garnered from the patient encounter at the referring not accepting institution.

Our primary outcome was discharge disposition. Discharges with missing information regarding discharge disposition were excluded.

Demographic data analyzed included information on gender, age, race, expected primary payer, and median household income quartile. Because of the prevalence of missing race, encounters missing race information were recoded as “missing.” Missing values for other variables in the analysis were excluded using listwise deletion. Median household income according to patient’s residential zip code was reported based upon NIS predetermined quartiles (0–25th percentile [first], 26th-50th percentile [second], 51st-75th percentile [third], or 76th-100th percentile [fourth]).

Clinical data analyzed included a comorbidity assessment, EGS diagnosis groups (detailed above), procedures performed, and day of the week of admission. Comorbidities were accounted for by applying the Charlson Comorbidity Index.21,22 To describe the operative procedures performed during the admission and prior to transfer, ICD-9-CM procedures codes previously identified as pertaining to EGS ICD-9-CM diagnoses were applied.19,20

Hospital characteristics analyzed (as defined by NIS) included total number of discharges, bed size (small, medium, large), hospital region, hospital control/ownership (government, nonfederal; private, non-profit; private, investor-own), hospital location (rural or urban), and teaching status (teaching or nonteaching). As bed size and total number of discharges represent different constructs (i.e., capacity for number of patients versus how quickly a hospital can move patients through, respectively), both were included in the model.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics for patient and hospital characteristics were reported as percentages for categorical variables and means and standard errors or median and interquartile range for continuous variables, as appropriate. We compared unadjusted differences by transfer status using the Chi-squared test for categorical variables and the t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney for continuous variables, as appropriate.

Patient- and hospital-level factors were examined as predictors of transfer to another acute care hospital with a multivariate proportional cause-specific hazards model. Because patients may succumb to death or discharge to other locations rather than transfer to an acute care facility, a competing risks analysis considering the NIS design was applied to assess the effect of risk factors for transfer.23

Data analysis and statistics were performed with the SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The data come from a nationally available, publicly accessible deidentified data set. Therefore, IRB approval and consent were not obtained.

Results

In our study, 1.8% of encounters resulted in a transfer between 2008 and 2013 (n=318,286). (Table 1) Transferred patients were on average 62 years old, and 67.7% were white. Most patients were insured with Medicare (52.9%), private (26.7%), or Medicaid insurance (10.8%). The most common EGS diagnoses among transferred patients were related to hepatopancreatobiliary (n=90,989 [28.6%]) and upper gastrointestinal tract (n=60,088 [18.9%]) conditions. Most transferred patients (n=269,976 [84.8%]) did not have a procedure prior to transfer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Emergency General Surgery Patients Transferred to Acute Care Facilities in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2008–2013

| Not Transferred (n=16,918,415) | Transferred (n=318,286) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean±standard error) | 58.8±0.068 | 61.6±0.097 | <0.0001 |

| Gender, % (n) | |||

| Male | 46.0 (7,777,214) | 50.1 (159,499) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 54.0 (9,141,201) | 49.9 (158,787) | |

| Race, % (n) | |||

| White | 63.2 (10,691,886) | 67.7 (215,569) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 11.7 (1,973,646) | 9.1 (28,927) | |

| Hispanic | 10.3 (1,745,396) | 6.1 (19,509) | |

| Other | 4.9 (824,048) | 4.2 (13,428) | |

| Missing | 10.0 (1,683,439) | 12.8 (40,852) | |

| Primary payer, % (n) | |||

| Medicare | 45.7 (7,729,253) | 52.9 (168,363) | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid | 11.4 (1,927,200) | 10.8 (34,279) | |

| Private insurance | 30.1 (5,095,711) | 26.7 (84,991) | |

| Self-pay | 8.6 (1,449,667) | 5.4 (17,276) | |

| No charge | 1.0 (162,567) | 0.4 (1,274) | |

| Other | 3.3 (554,020) | 3.8 (12,101) | |

| Median household income national quartile, % (n) | |||

| 0–25th | 27.7 (4,688,902) | 34.2 (108,949) | <0.0001 |

| 26th-50th | 25.6 (4,337,466) | 29.3 (93,267) | |

| 51st-75th | 24.6 (4,168,518) | 20.4 (64,868) | |

| 76th-100th | 22.0 (3,723,529) | 16.1 (51,202) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, % (n) | |||

| 0 | 36.1 (5,243,176) | 28.5 (80,129) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 27.7 (4,028,424) | 26.9 (75,813) | |

| 2 | 15.2 (2,205,532) | 17.5 (49,287) | |

| 3 | 21.0 (3,047,643) | 27.1 (76,352) | |

| Diagnosis group description, % (n) | |||

| Hepatic-pancreatic-biliary | 20.6 (3,478,532) | 28.6 (90,989) | <0.0001 |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract | 19.7 (3,338,885) | 18.9 (60,088) | |

| Soft tissue | 19.4 (3,287,799) | 13.5 (43,053) | |

| Colorectal | 18.4 (3,107,080) | 12.1 (38,658) | |

| Intestinal obstruction | 10.0 (1,690,038) | 11.6 (36,846) | |

| General abdominal | 5.3 (892,904) | 6.8 (21,565) | |

| conditions | |||

| Vascular | 2.5 (421,580) | 3.0 (9,424) | |

| Cardiothoracic | 0.8 (137,851) | 2.6 (8,119) | |

| Hernias | 3.1 (526,304) | 2.4 (7,731) | |

| Other | 0.1 (24,948) | 0.4 (1,261) | |

| Resuscitation | 0.1 (12,494) | 0.2 (553) | |

| Procedure-related groupings, % (n) | |||

| None | 68.0 (11,507,137) | 84.8 (269,976) | <0.0001 |

| Cholecystectomy | 9.3 (1,579,589) | 3.0 (9,604) | |

| Orthopedic or soft tissue | 5.0 (852,195) | 2.7 (8,742) | |

| Colon | 2.9 (492,148) | 1.9 (6,037) | |

| Stomach | 1.5 (258,286) | 1.5 (4,678) | |

| Cardiothoracic | 0.6 (99,610) | 1.3 (4,212) | |

| Small bowel | 1.5 (249,165) | 1.2 (3,691) | |

| Vascular | 0.7 (118,816) | 0.7 (2,370) | |

| Lysis of adhesions | 1.6 (264,362) | 0.7 (2,232) | |

| Appendix | 5.7 (959,043) | 0.6 (1,791) | |

| Hernia | 1.8 (309,408) | 0.4 (1,399) | |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 0.1 (14,204) | 0.3 (859) | |

| Exploratory laparotomy | 0.1 (22,573) | 0.2 (722) | |

| Anorectal | 0.7 (112,640) | 0.2 (504) | |

| Pancreas | 0.1 (12,756) | 0.2 (494) | |

| Hepatobiliary | 0.2 (28,820) | 0.1 (368) | |

| Amputations | 0.1 (18,410) | 0.1 (279) | |

| Laparoscopy | 0.1 (15,275) | 0.1 (256) | |

| Bladder | 0.0 (3,662) | 0.0 (66) | |

| Kidney | 0.0 (3,126) | 0.0 (<11) | |

| Day of the week of admission, % (n) | |||

| Monday-Friday | 75.3 (12,746,040) | 74.6 (237,328) | <0.0001 |

| Saturday-Sunday | 24.7 (4,172,375) | 25.4 (80,958) | |

On univariate analysis, patients were more likely to be transferred if they were in a small facility, a hospital with government nonfederal ownership, or a rural hospital. (Table 2) On multivariate analysis, hospital- rather than patient-level factors were stronger predictors of transfer. (Table 3) Patient-level factors associated with transfer included male sex (Hazard Ratio [HR] 1.09 [95% Confidence Intervals (CI) 1.07–1.11]), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (HR for CCI of 2 is 1.08 [95% CI 1.04–1.11] and HR for CCI of 3 is 1.16 [95% CI 1.12–1.20]), and admission on a Saturday or Sunday (HR 1.04 [95% CI 1.02–1.07]). Hospital-level factors were the strongest predictors of transfer, especially small bed size (HR 2.52 [95% CI 2.28–2.79]), medium bed size (HR 1.32 [95% CI 1.21–1.44]), government nonfederal ownership (HR 1.19 [95% CI 1.11–1.28]), and rural location (HR 4.58 [95% CI 3.98–5.27]) as well as urban nonteaching location (HR 1.88 [95% CI 1.70–2.10]).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Hospitals that Admitted Emergency General Surgery Patients Transferred to Acute Care Facilities in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2008– 2013

| Not Transferred (n=16,858,093) | Transferred (n=317,357) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total discharges median, Q1-Q3 | 9502.2, 3732.4–20749.0 | 3557.7, 1318.0–10342.0 | <0.0001 |

| Bed size, % (n) | |||

| Small | 13.4 (2,264,795) | 29.6 (94,233) | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 26.0 (4,401,197) | 26.8 (85,447) | |

| Large | 60.6 (10,252,423) | 43.5 (138,606) | |

| Region of hospital, % (n) | |||

| Northeast | 21.0 (3,548,002) | 20.0 (63,543) | <0.0001 |

| Midwest | 21.6 (3,653,922) | 27.8 (88,596) | |

| South | 37.8 (6,402,674) | 34.8 (110,916) | |

| West | 19.6 (3,313,816) | 17.3 (55,230) | |

| Control/ownership of hospital, % (n) | |||

| Government, nonfederal | 11.6 (1,972,582) | 16.8 (53,589) | <0.0001 |

| Private, non-profit | 74.0 (12,519,329) | 68.7 (218,623) | |

| Private, investor-owned | 14.4 (2,426,504) | 14.5 (46,075) | |

| Location/teaching status of hospital, % (n) | |||

| Rural | 12.3 (2,073,200) | 36.8 (117,220) | <0.0001 |

| Urban nonteaching | 45.9 (7,757,260) | 43.8 (139,511) | |

| Urban teaching | 41.9 (7,087,954) | 19.3 (61,556) | |

Table 3.

Predictors of Transfer of Emergency General Surgery Patients to Acute Care Hospitals in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2008–2013

| Parameter | Hazard Ratio | 95% Hazard Ratio Confidence Limits |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.09 | (1.07–1.11) |

| Female | Reference | |

| Age | 0.99 | (0.99–1.00) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 0.91 | (0.86–0.96) |

| Hispanic | 0.84 | (0.78–0.91) |

| Other | 1.00 | (0.93–1.08) |

| Missing | 1.08 | (1.01–1.16) |

| White | Reference | |

| Expected primary payer | ||

| Medicare | 0.92 | (0.89–0.95) |

| Medicaid | 0.85 | (0.81–0.88) |

| Self-pay | 0.65 | (0.61–0.69) |

| No charge | 0.57 | (0.46–0.70) |

| Other | 1.14 | (1.05–1.23) |

| Private insurance | Reference | |

| Household income of patient’s zip code (median) | ||

| 26th to 50th percentile | 0.92 | (0.88–0.96) |

| 51st to 75th percentile | 0.88 | (0.84–0.93) |

| 76th to 100th percentile | 0.89 | (0.84–0.95) |

| 0–25th percentile | Reference | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||

| 1 | 0.97 | (0.94–0.99) |

| 2 | 1.08 | (1.04–1.11) |

| 3 | 1.16 | (1.12–1.20) |

| 0 | Reference | |

| EGS diagnosis group | ||

| Resuscitation Yes | 0.61 | (0.44–0.86) |

| Resuscitation No | Reference | |

| General abdominal conditions Yes | 0.71 | (0.60–0.84) |

| General abdominal conditions No | Reference | |

| Intestinal obstruction Yes | 0.62 | (0.53–0.73) |

| Intestinal obstruction No | Reference | |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract Yes | 0.42 | (0.36–0.50) |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract No | Reference | |

| Hepatic-pancreatic-biliary Yes | 0.64 | (0.54–0.75) |

| Hepatic-pancreatic-biliary No | Reference | |

| Colorectal Yes | 0.22 | (0.18–0.25) |

| Colorectal No | Reference | |

| Hernias Yes | 0.70 | (0.59–0.83) |

| Hernias No | Reference | |

| Soft tissue Yes | 0.21 | (0.18–0.25) |

| Soft tissue No | Reference | |

| Vascular Yes | 0.39 | 0.33–0.46) |

| Vascular No | Reference | |

| Cardiothoracic Yes | 0.93 | (0.76–1.13) |

| Cardiothoracic No | Reference | |

| Procedure type | ||

| Colon | 0.26 | (0.24–0.28) |

| Amputation | 0.41 | (0.31–0.56) |

| Anorectal | 0.43 | (0.34–0.54) |

| Appendix | 0.10 | (0.09–0.12) |

| Bladder | 0.30 | (0.17–0.54) |

| Cardiothoracic | 0.33 | (0.29–0.38) |

| Cholecystectomy | 0.16 | (0.15–0.17) |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 0.36 | (0.30–0.43) |

| Exploratory laparotomy | 0.54 | (0.44–0.65) |

| Stomach | 0.42 | (0.39–0.46) |

| Hernia | 0.11 | (0.10–0.13) |

| Laparoscopy | 0.44 | (0.30–0.64) |

| Hepatobiliary | 0.29 | (0.21–0.39) |

| Lysis of adhesions | 0.16 | (0.14–0.18) |

| Orthopedic or soft tissue | 0.59 | (0.55–0.63) |

| Pancreas | 0.31 | (0.24–0.39) |

| Kidney | 0.90 | (0.34–2.38) |

| Small bowel | 0.24 | (0.22–0.26) |

| Vascular | 0.56 | (0.50–0.63) |

| No procedure | Reference | |

| Day of Admission | ||

| Admitted Saturday-Sunday | 1.04 | (1.02–1.07) |

| Admitted Monday-Friday | Reference | |

| Total number of discharges | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) |

| Hospital Bed Size | ||

| Small | 2.52 | (2.28–2.79) |

| Medium | 1.32 | (1.21–1.44) |

| Large | 1.00 | |

| Hospital Region | ||

| Midwest | 1.13 | (1.03–1.23) |

| South | 0.83 | (0.76–0.91) |

| West | 0.97 | (0.89–1.07) |

| Northeast | Reference | |

| Hospital Ownership | ||

| Government, nonfederal | 1.19 | (1.11–1.28) |

| Private, invest-own | 0.96 | (0.89–1.03) |

| Private, not-profit | Reference | |

| Hospital Location/Teaching Status | ||

| Rural | 4.58 | (3.98–5.27) |

| Urban nonteaching | 1.89 | (1.70–2.10) |

| Urban teaching | Reference | |

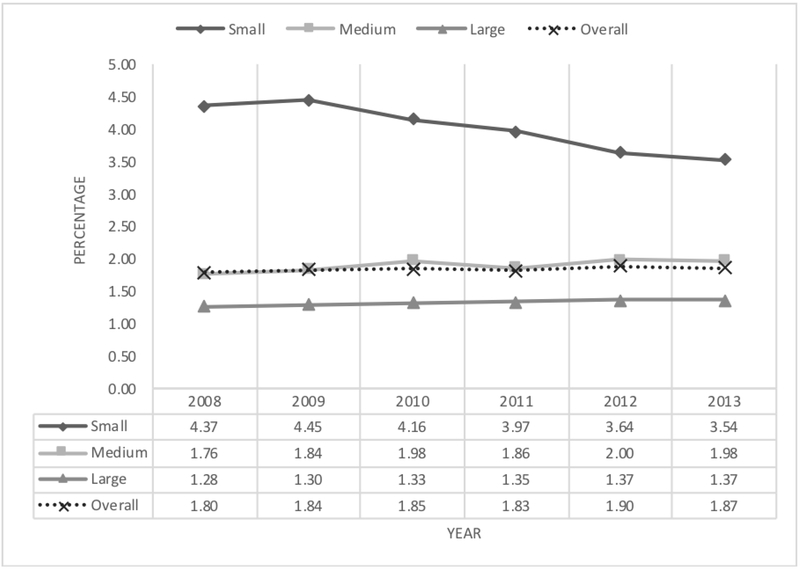

In addition to examining risk factors for transfer, we also examined the rates of transfer stratified by bed size across the six years included in our study. (Figure 1) While the overall rate of transfer remained relatively constant, the percentage of transfers from hospitals with a small bed size according to NIS decreased from a high of 4.45% in 2009 to a low of 3.54% in 2013.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Inpatient Emergency General Surgery Patients Transferred to Acute Care Hospitals According to Bed Size in Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2008–2013

Discussion

Interhospital transfers of emergency general surgery (EGS) patients are, in part, based on the needs of the patients compared to the availability of resources. While previous studies have focused on predictors of transfer among patients with traumatic surgical emergencies, the evaluation of predictors of transfer among patients with non-traumatic surgical emergencies is limited.24 In this study, we found that hospital-level, as compared to patient-level, factors were stronger predictors of the need for transfer based upon a nationally representative data set. This information can be applied by providers as they consider the resources available while caring for EGS patients and can inform the development of networks and guidelines to care for EGS patients.

EGS has found a quality improvement “home” under the acute care surgery umbrella. Acute care surgery encompasses trauma, EGS, and surgical critical care. As acute care surgery evolves, EGS is being recognized as a public health concern in need of organized efforts for quality improvement25 and potentially regionalization.13 Similar to that which has occurred over the past five decades during which the national trauma system has developed,26 initiatives focused on EGS care have the potential to improve the timeliness and quality of care delivered for this often-overlooked area of surgical disease.

A vital component of the success of trauma systems is the interhospital transfer of injured patients. When a patient’s needs exceed the capacity of the index center, the American College of Surgeons Advance Trauma Life Support program recommends that the patient be transferred to a higher level of care.27 Indeed, the transfer of injured patients from smaller hospitals to trauma centers has been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity.28,29 A national study determined patient- and hospital-level factors associated with the decision to transfer (versus admit) among severely injured patients (n=19,312 encounters) who were initially seen at non- trauma center EDs.30 Compared with patients without insurance, the adjusted absolute risk of admission versus transfer was 14.3% (95% CI, 9.2%−19.4%) higher for patients with Medicaid and 11.2% (95% CI, 6.9%−15.4%) higher for patients with private insurance. Other factors associated with admission versus transfer included severe abdominal injuries (risk difference, 15.9%; 95% CI, 9.4%−22.3%), urban teaching hospital versus non-teaching hospital (risk difference, 26.2%; 95% CI, 15.2%−37.2%), and annual ED visit volume (risk difference, 3.4%; 95% CI, 1.6%−5.3% higher for every additional 10,000 annual ED visits). A different study using the Oregon State Trauma Registry assessed factors associated with the transfer of injured patients from EDs of non–tertiary care hospitals. Among the 3,785 (37%) patients transferred to a tertiary care hospital from the ED, the hospital of initial presentation was the factor of greatest importance in predicting transfer. Additional nonclinical variables independently associated with transfer included type and level of hospital, patient age, increasing distance from the nearest higher-level hospital (a measure of geographic isolation), and the patient’s insurance status.31

Although the factors influencing the transfer of injured patients have been rigorously investigated24,31–33 and guidelines for the interhospital transfer of injured patients have been established by the ACS Committee on Trauma,34 similar studies and standards have not been established for the EGS population. With a shrinking number of general surgeons willing to cover emergency cases3,4,35,36 as well as the growing and aging of the United States population, the burden of EGS care will increase over the next several decades,3,5 and the system of interhospital transfers of EGS patients will need to be optimized.37 However, a comprehensive study of EGS patients transferred between hospitals to inform the establishment of guidelines to direct transfers of EGS patients is lacking. Thus, this research fills a critical gap in our understanding of why patients are transferred and the factors that are associated with the decision to transfer. While the importance of hospital-level factors in predicting the need for transfer should not be underappreciated, at the encounter-level, this study can guide researchers and healthcare providers so that they focus their efforts on the most influential patient populations as they investigate potential emergency general surgery regionalization. For example, researchers may investigate reasons for transfer among patients with specific diagnoses or socioeconomic status as well as prioritize the development of transfer networks for patients with hepatic-pancreatic-biliary diagnoses. Should EGS regionalization become widespread, like trauma care before it, the present study will be critical to predict patients’ needs and to guide the allocation of limited resources.13

Our study also found that while the overall rate of transfers was stable over the six-year study period, the percentage of patients transferred at small hospitals steadily decreased. This trend warrants further investigation. Although smaller hospitals may be increasing their capability to provide care to EGS patients, a second explanation may be that patients are less likely to initially present to smaller hospitals for their initial care. While not specifically addressed within this study, variability in transfer rates for similar patients with the same diagnosis would be anticipated. Future research and quality improvement efforts should investigate what enables one hospital to care for a patient in his or her home community while another patient in a different location may need to be transferred for appropriate care.

Regionalization should be considered as only one approach to address the needs of emergency general surgical patients. Furthermore, implementing a formal regionalized system for emergency general surgery care would require significant, deliberate thought and planning involving a wide stakeholder base. While regionalization may be an appropriate approach for select patients and diagnoses, methods to improve access to quality care locally, through telemedicine, enhanced partnerships between rural and academic centers, and ensuring a rural general surgery workforce, among others, should be explored and developed. Although regionalization of emergency general surgery may be able to be developed in parallel to the trauma system, trauma hospitals and providers do not overlap perfectly with that of emergency general surgery. Thus, the emergency general surgery system will likely be wider, more complex, and more expensive (without an obvious source of funding) than that of the trauma system. We also cannot underestimate the potential burden placed on patients and their families as part of regionalization for emergency general surgery, trauma, or any other diagnosis. In the effort to obtain appropriate care, they are potentially uprooted not only from their “medical home” but also their social support networks and likely incur substantial costs.

The current study has a number of limitations. First, NIS is an administrative database of discharge records from US hospitals; thus, data on the physiologic status of the patient is not available for analysis. Additionally, information on elements that would influence the decisions surrounding transfer (e.g., reason for transfer), the transfer process itself (e.g., potential delays in transfer), and detailed resources and capabilities of the referring hospital are not available for analysis. Third, our focus was on patients who were admitted for a primary diagnosis of an EGS condition and subsequently transferred. Patients who developed an EGS diagnosis during the course of their hospital stay that was initially due to a non-EGS diagnosis (e.g., mesenteric ischemia after elective cardiac surgery) warrant future study. Similarly, because the NIS does not allow for patients to be tracked between hospitals, our data only reflect the characteristics of the transfer during the initial referring hospital encounter as opposed to subsequent hospital stays if the patient was transferred more than once prior to death or discharge to home or an extended care facility.

Elucidating the patient- and hospital-level factors associated with the transfer of EGS patients provides critical information toward informing interventions to optimize the EGS healthcare system (e.g., development of transfer guidelines to standardize approaches to transfer, matching patient need with hospital provision). While large, urban centers are likely best equipped to care for complex EGS patients and may serve as foci for regionalization, future efforts should build upon this data to inform organizational planning and ensure proper resource allocation for the delivery of EGS care in an evolving health care environment.20 All EGS patients cannot and should not be transferred. However, objective guidelines to identify patients appropriate for transfer should be developed and validated. Guidelines will need to be tailored to the resources and capabilities of the hospital; such criteria have the potential to reduce the time to definitive care and improve health outcomes.3

Acknowledgment

Authors’ contributions: A.I. contributed to conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; and drafting the work or revising it critically. X.W. contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and drafting the work or revising it critically. J.H. contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and drafting the work or revising it critically. B.H. contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and drafting the work or revising it critically. M.S. contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and drafting the work or revising it critically. J.S. contributed to conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; and drafting the work or revising it critically. S.F-T. contributed to conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; and drafting the work or revising it critically. C.G. contributed to conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; and drafting the work or revising it critically. The project described was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 1K08HS025224-01A1 and the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ or NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Ogola GO, Gale SC, Haider A, Shafi S. The financial burden of emergency general surgery: National estimates 2010 to 2060. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(3):444–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voelker R Experts say projected surgeon shortage a “looming crisis” for patient care. Jama. 2009;302(14):1520–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cofer JB, Burns RP. The developing crisis in the national general surgery workforce. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(5):790–795; discussion 795–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams TE Jr, Satiani B, Thomas A, Ellison EC. The impending shortage and the estimated cost of training the future surgical workforce. Annals of surgery. 2009;250(4):590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etzioni DA, Finlayson SR, Ricketts TC, Lynge DC, Dimick JB. Getting the science right on the surgeon workforce issue. Archives of Surgery. 2011;146(4):381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACS Health Policy Research Institute and the American Association of Medical Colleges. The Surgical Workforce in the United States: Profile and Recent Trends. . Chapel Hill, NC: April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudkin SE, Oman J, Langdorf MI, et al. The state of ED on-call coverage in California. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(7):575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holena DN, Mills AM, Carr BG, et al. Transfer status: a risk factor for mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Surgery. 2011;150(3):363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg AL, Hofer TP, Strachan C, Watts CM, Hayward RA. Accepting critically ill transfer patients: adverse effect on a referral center’s outcome and benchmark measures. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(11):882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combes A, Luyt CE, Trouillet JL, Chastre J, Gibert C. Adverse effect on a referral intensive care unit’s performance of accepting patients transferred from another intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(4):705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golestanian E, Scruggs JE, Gangnon RE, Mak RP, Wood KE. Effect of interhospital transfer on resource utilization and outcomes at a tertiary care referral center. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1470–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flabouris A, Hart GK, George C. Outcomes of patients admitted to tertiary intensive care units after interhospital transfer: comparison with patients admitted from emergency departments. Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10(2):97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santry HP, Janjua S, Chang Y, Petrovick L, Velmahos GC. Interhospital transfers of acute care surgery patients: should care for nontraumatic surgical emergencies be regionalized? World J Surg. 2011;35(12):2660–2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arthur KR, Kelz RR, Mills AM, et al. Interhospital transfer: an independent risk factor for mortality in the surgical intensive care unit. Am Surg. 2013;79(9):909–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borlase BC, Baxter JK, Kenney PR, Forse RA, Benotti PN, Blackburn GL. Elective intrahospital admissions versus acute interhospital transfers to a surgical intensive care unit: cost and outcome prediction. J Trauma. 1991;31(7):915–918; discussion 918–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quality AfHRa. Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2014. In: Quality AfHRa, ed. Rockville MD. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houchens RL, Ross DN, Elixhauser A, Jiang J. Nationwide Inpatient Sample Redesign Final Report. In: Quality USAfHRa, ed2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shafi S, Aboutanos MB, Agarwal S, Jr., et al. Emergency general surgery: definition and estimated burden of disease. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(4):1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah AA, Haider AH, Zogg CK, et al. National estimates of predictors of outcomes for emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3):482–490; discussion 490–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gale SC, Shafi S, Dombrovskiy VY, Arumugam D, Crystal JS. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: A 10-year analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample--2001 to 2010. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(2):202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: the Charlson comorbidity index. Methods of information in medicine. 1993;32(5):382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Hoore W, Bouckaert A, Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1996;49(12):1429–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim HJ, Zhang X, Dyck R, Osgood N. Methods of competing risks analysis of end-stage renal disease and mortality among people with diabetes. BMC medical research methodology. 2010;10:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delgado MK, Yokell MA, Staudenmayer KL, Spain DA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wang NE. Factors Associated With the Disposition of Severely Injured Patients Initially Seen at Non–Trauma Center Emergency Departments: Disparities by Insurance Status. JAMA surgery. 2014;149(5):422–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calland JF, Ingraham AM, Martin N, et al. Evaluation and management of geriatric trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg.73(5 Suppl 4):S345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trunkey DD. History and development of trauma care in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000(374):36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/atls. Accessed 1/2/2018.

- 28.Newgard CD, McConnell KJ, Hedges JR, Mullins RJ. The benefit of higher level of care transfer of injured patients from nontertiary hospital emergency departments. J Trauma. 2007;63(5):965–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sampalis JS, Denis R, Frechette P, Brown R, Fleiszer D, Mulder D. Direct transport to tertiary trauma centers versus transfer from lower level facilities: impact on mortality and morbidity among patients with major trauma. J Trauma. 1997;43(2):288–295; discussion 295–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delgado MK, Yokell MA, Staudenmayer KL, Spain DA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wang NE. Factors associated with the disposition of severely injured patients initially seen at non-trauma center emergency departments: disparities by insurance status. JAMA surgery. 2014;149(5):422–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newgard CD, McConnell KJ, Hedges JR. Variability of trauma transfer practices among non-tertiary care hospital emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(7):746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nathens AB, Maier RV, Copass MK, Jurkovich GJ. Payer status: the unspoken triage criterion. J Trauma. 2001;50(5):776–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parks J, Gentilello LM, Shafi S. Financial triage in transfer of trauma patients: a myth or a reality? Am J Surg. 2009;198(3):e35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. Chicago, IL: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hutter MM. Specialization: the answer or the problem? Ann Surg. 2009;249(5):717–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Division of Advocacy and Health Policy. A growing crisis in patient access to emergency surgical care. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2006;91(8):8–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wheatley B, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Planning Committee on Regionalizing Emergency Care Service. Regionalizing emergency care : workshop summary Future of emergency care. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press,; 2010: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedges JR, Newgard CD, Mullins RJ. Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act and trauma triage. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10(3):332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]