Abstract

Introduction:

Data on time trends of dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) during the index endoscopy (ie, prevalent cases) are limited. Our aim was to determine the prevalence patterns of BE-associated dysplasia on index endoscopy over the past 25 years.

Methods:

The Barrett’s Esophagus Study is a multicenter outcome project of a large cohort of patients with BE. Proportions of patients with index endoscopy findings of no dysplasia (NDBE), low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD), and EAC were extracted per year of index endoscopy, and 5-yearly patient cohorts were tabulated over years 1990 to 2010+ (2010-current). Prevalent dysplasia and endoscopic findings were trended over the past 25 years using percentage dysplasia (LGD, HGD, EAC, and HGD/EAC) to assess changes in detection of BE-associated dysplasia over the last 25 years. Statistical analysis was done using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS, Cary, NC).

Results:

A total of 3643 patients were included in the analysis with index endoscopy showing NDBE in 2513 (70.1%), LGD in 412 (11.5%), HGD in 193 (5.4%), and EAC in 181 (5.1%). Over time, there was an increase in the mean age of patients with BE (51.7 ± 29 years vs 62.6 ± 11.3 years) and the proportion of males (84% vs 92.6%) diagnosed with BE but a decrease in the mean BE length (4.4±4.3 cm vs 2.9±3.0 cm) as time progressed (1990–1994 to 2010–2016 time periods). The presence of LGD on index endoscopy remained stable over 1990 to 2016. However, a significant increase (148% in HGD and 112% in EAC) in the diagnosis of HGD, EAC, and HGD/EAC was noted on index endoscopy over the last 25 years (P < .001). There was also a significant increase in the detection of visible lesions on index endoscopy (1990–1994, 5.1%; to 2005–2009, 6.3%; and 2010+, 16.3%) during the same period.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that the prevalence of HGD and EAC has significantly increased over the past 25 years despite a decrease in BE length during the same period. This increase parallels an increase in the detection of visible lesions, suggesting that a careful examination at the index examination is crucial. (Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:257–63.)

INTRODUCTION

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a precancerous condition that can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). The incidence of EAC has been on the increase in the last 4 decades,1 and it is projected to increase to 7-fold by the 2030.2 Cancer registries in the United States, Australia, and Europe have reported increased rates of EAC.3–6 According to SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) data, the lifetime risk of developing EAC in the United States is 0.5%, and it is the 11th leading cause of cancer death.7 The 5-year survival upon diagnosis is currently estimated to be 18.8%, which has been an improvement from a mere 10% in 1997. Because BE is a precursor lesion for EAC, with an annual rate of progression of around 0.1% to 0.5%, earlier detection by screening of high-risk individuals and surveillance of those diagnosed with BE may provide an opportunity to intervene if early neoplasia is found.8,9 Practice guidelines identify this as a crucial step and recommend screening for BE in high-risk individuals.10,11

In a meta-analysis of studies of patients with BE, Visrodia et al12 demonstrated that most EACs were diagnosed at the index examination or within 1 year of detection of BE. These authors reported that 1 in 4 cases of EAC is diagnosed within 1 year of index endoscopy in patients with BE, raising the question of a careful and vigilant endoscopic examination.13 Previous studies have shown that the incidence of BE is increasing over time.14–17 However, it remains unclear at this point if the presence of dysplasia and/or early EAC at index endoscopy has changed over the last few decades. The importance of knowing these data is manifold. It is important to determine if current screening guidelines are leading to more effective detection of prevalent and incident dysplasia/EAC cases effectively in recent years compared with the past. Given the possible miss rate of prevalent EAC, it would also be important to know whether visible lesions harboring neoplasia are present on index examination. Examination of such trends will guide future strategies to improve the quality of index endoscopic examination.

Given the limited amount of information on temporal trends of prevalent dysplasia/EAC in patients with BE, we aimed to determine the prevalence of BE-related lesions on index endoscopy over the past 25 years using data from a multicenter study of tertiary centers specializing in BE management.

METHODS

Participating institutions

The Barrett’s Esophagus Study is a multicenter outcomes project of a large cohort of patients with BE. It includes 6 tertiary referral centers: Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri; University of Alabama, Birmingham, Alabama; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Southern Arizona Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Tucson, Arizona; the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio; the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Portland, Oregon; and the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland. Data from these centers were collected over 2 decades with separate inception points for each individual center. Data collection spanned from January 1990 to October 2016 (study period). Datasets from each center were then merged into the main study database using Microsoft Access for Windows 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash). A unique identification number was assigned to each patient to protect confidentiality in accordance with the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act. The study was approved by each institution’s Institutional Review Board.

Endoscopy and histopathology

BE was defined as any length of salmon-colored mucosa extending proximal to the gastroesophageal junction with biopsy-proven evidence of intestinal metaplasia.18,19 Length of BE was measured from the most proximal squamo-columnar junction to the anatomic gastroesophageal junction. Visible lesions within the BE segment were noted. A minimum of 4-quadrant biopsy specimens was obtained every 1 to 2 cm for suspected dysplasia in adherence with known society guidelines.20 An experienced pathologist performed the histologic assessment and diagnosis at each participating center; no central reading was performed. The highest histologic grade at any given endoscopy/biopsy procedure was deemed as the overall histology.

Patient data

We included patients with documented BE at their index endoscopy. Several of these patients did undergo surveillance endoscopy; however, only findings at the initial endoscopy were considered. Patients who were referred for endoscopic therapy of BE lesions or known HGD/EAC from a previous known endoscopy were excluded and those presenting with dysphagia with suspected/known cancer were excluded from the database. Patients with index findings of intestinal metaplasia or non-dysplastic BE (NDBE), low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD), and EAC were extracted per year of index endoscopy. Demographic information (age, sex, ethnicity), endoscopy results (procedure date, BE segment length, presence, and size of hiatal hernia), and histopathologic diagnosis were collected.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are shown as number (%) and continuous variables as means ± standard deviation. Prevalent dysplasia diagnosed on index endoscopy and endoscopic findings were trended over the past 25 years. Results were tabulated in 5-yearly patient cohorts over the years 1990 to 2016. Because of the ordinal groupings of the years, we used linear trend tests for continuous variables and the Cochran-Armitage trend test for categorical variables. As a sensitivity analysis, we derived age-, sex-, and race-adjusted rates. We performed this by running a multivariable logistic regression model on each histology adjusted for 4 factors: time frame, age, sex, and race. We then ran the least square means on the timeframe variable. This created model-based estimates after standardizing the distribution of the other 3 variables across time frames. Missing data were imputed using sequential regression techniques using the IVEWare software (Survey Research Center, Ann Arbor, Mich). Statistical analysis was done using SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC). A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient demographics and endoscopic characteristics

A total of 3643 patients with BE underwent an index endoscopy examination between 1990 and 2016. The mean age of the patient cohort was 58 ± 19 years. Most of the patients were white (92%) and 88% were men. The mean BE length was 3.3 cm (±3.4 cm) with a mean follow-up period of 4 years (±6.5 years). When index histology was examined over a 25-year study period, non-dysplastic BE was diagnosed in most patients (70.1%) followed by LGD (11.5%). Prevalent HGD/EAC was diagnosed in 10.3% of patients over the same time period. Visible lesions were noted in 6.7% of the patients. Demographic and histologic characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of the Barrett’s esophagus cohort over 1990–2016

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3643 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 58.0 ± 19.9 |

| White | 3245 (92.0) |

| Males | 3207 (88.0) |

| Follow-up period (years), mean ± SD | 4.0 ± 6.5 |

| Baseline histology | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 2513 (70.1) |

| LGD | 412 (11.5) |

| HGD | 193 (5.4) |

| EAC | 181 (5.1) |

| No intestinal metaplasia | 299 (8.2) |

| HGD/EAC | 374 (10.3) |

| Visible lesions | 243 (6.7) |

| BE length (cm) | 3.3 ± 3.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 28.5 ± 5.8 |

| Obese (BMI 30 kg/m2) | 1304 (35.8) |

Values are number (%) except where indicated otherwise.

SD, Standard deviation; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; EAC, esophageal cancer; BE, Barrett’s esophagus; BMI, body mass index.

Trends of change in patient characteristics and endoscopic findings

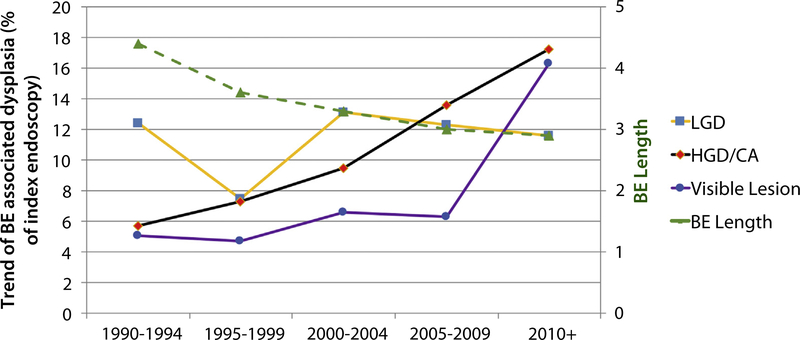

As the years progressed, an increase in the mean age of BE diagnosis was noted with a mean age of 51.7 years (±29 years) between 1990 and 1994 compared with 62.6 years (±11.3 years) between 2010 and 2016. Similarly, there was an increase in the proportion of males diagnosed with BE; 84% of patients were male in the period 1990 to 1994 versus 92.6% in the 2010 to 2016 cohort. The mean length of BE was the only variable that decreased significantly from 4.4 ± 4.3 cm (1990–1994) to 2.9 ± 3.0 cm (2010–2016). There was also an increase in the detection of visible lesions from 5.1% in 1990 to 1994 to 6.3% in 2005 to 2009 to 16.3% in 2010 to 2016. Information on the presence of hiatal hernia, use of aspirin, proton pump inhibitors, histamine-receptor blockers, and statins were collected as well when available.

The mean age of the patients with prevalent HGD/EAC did not change significantly over the time (1990–1994, 62.9 ± 12.2 years; to 2010+, 62.6 ± 15.7 years, P =.19). Similarly, there was no statistically significant change in the number of males with HGD/EAC from 1990 to 1994 to 2010 onward (90% vs 94.8%, P = .46). There was a statistically significant decrease in BE length in patients with prevalent HGD/EAC over these years: in 1990 to 1994, mean BE length was 8.6 ± 8.9 cm, whereas this decreased to 4.2 ± 4.0 cm during 2010 onward (P = .004).

Trend of histology on index endoscopy

When histology at the index endoscopy was analyzed (Fig. 1), it was noted that the presence of LGD had remained stable over 25 years, and this trend was statistically significant over the 5-year groups: 1990 to 1994, 12.4% versus 2000–2004, 13.1% versus 2010 to 2016, 11.6%; P < .01 (Table 2). However, there was a significant increase in the diagnosis of HGD/EAC detected on index endoscopy over the last 25 years: 1990 to 1994, 5.7%; 2000 to 2004, 9.5%, which increased to 17.2% during 2010 to 2016. This change was statistically significant over 5-year cohorts (P < .01). Taken individually, there was a significant increase in the cases of HGD (148% increase) and EAC (112% increase) from 1990 to 2016 (P < .001).

Figure 1.

Trend of BE-related dysplasia, visible lesions, and BE length over last 25 years on index endoscopy.

TABLE 2.

Five-year baseline prevalence of LGD, HGD, EAC, and HGD/EAC on index endoscopy

| Years | Number of patients, total | LGD (%) | HGD (%) | EAC (%) | HGD/EAC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1994 | 351 | 12.4 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 5.7 |

| 1995–1999 | 804 | 7.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 7.3 |

| 2000–2004 | 1372 | 13.1 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 9.5 |

| 2005–2009 | 778 | 12.3 | 6.7 | 7 | 13.6 |

| 2010+ | 338 | 11.6 | 10 | 7.6 | 17.2 |

LGD, Low-grade dysplasia; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; EAC, esophageal cancer.

The increase in trend for HGD/EAC remained statistically significant even after adjusting for BE length and the presence of visible lesions. In multivariate logistic regression for each histology adjusted for age, sex, race, and time frame, the trends remained similar (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online at www.giejournal.org). The adjusted odds ratio (OR, adjusted for age, sex, and race) of HGD/EAC for the period from 1995 to 1999 (referenced against 1990–1994) was 1.32 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77–2.23; P = .31). The odds of having HGD/EAC increased over time with adjusted OR for subsequent time periods were as follows: for 2000 to 2004, adjusted OR 1.45 (95% CI, 0.89–2.37; P = .14); for 2005 to 2009, adjusted OR 2.04 (95% CI, 1.23–3.40; P = .006), and for 2010+ this was 2.90 (95% CI, 1.69–4.98; P < .001). The mean body mass index across time periods was relatively stable with a slight increase in last time period in 2010+. The prevalence of obesity among patients was increasing (increase in obesity from 32.5% in 1990–1994 to 40.2% in 2010 onward); however, this was not statistically significant when trended compared with the first time period (Supplementary Table 1, available online at www.giejournal.org).

Time trends in the prevalence of dysplasia by center were also examined. For centers. 1, 3, and 4, which contributed most of the patients to the database, a significant increase in the prevalence of HGD/EAC was observed, similar to the overall results. Centers 2, 5, and 6 contributed relatively few cases of HGD/EAC, and therefore a trend analysis was not possible (Supplementary Table 2, available online at www.giejournal.org).

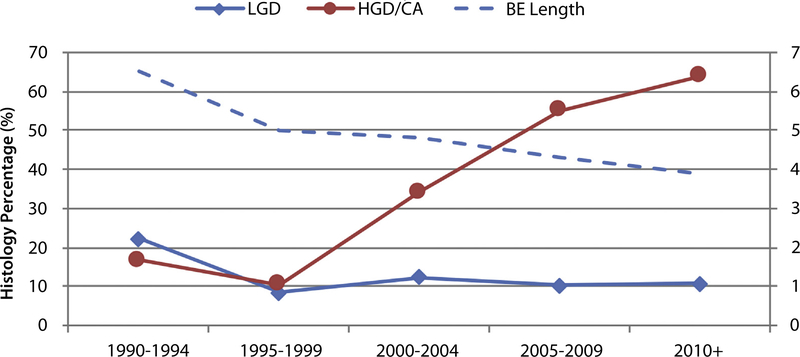

Detailed analysis of visible lesions

The proportion of visible lesions with HGD/EAC histology also increased over the years from 16.7% in 1990 to 1994 to 63.8% in 2010 to 2016 (P < .001). This is represented in Figure 2. For every 1-year increment, the OR for HGD/EAC was 1.058 (95% CI, 1.035–1.082; P < .001).

Figure 2.

Five-year trend analysis of the visible lesion cohort.

As the detection rate of visible lesions was higher with subsequent years, we examined baseline histology in all patients with visible lesions. Overall, 25.8% of visible lesions were harboring EAC, whereas 25.5% were dysplastic (13.8% HGD, 11.7% LGD). Non-dysplastic BE was noted in 44.6% of visible lesions over the years. Breakdown of the 5-year cohorts showed that, during the 1990 to 1994 time frame, most patients with visible lesions had NDBE (61%), and dysplasia or cancer was found in 39% of the patients (Supplementary Table 3, available online at www.giejournal.org). However, with time, there was reversal of this pattern (2010–2016) with higher detection of dysplasia/cancer versus NDBE (75.5% vs 23.4%). Details regarding the histology of visible lesions in the 5-years cohorts are provided in the Supplementary Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of 3643 patients with BE over 25 years from a multicenter registry demonstrates increasing diagnosis of prevalent HGD and EAC on index endoscopy. Our results parallel a previously published literature review and meta-analysis which reported almost 25% of EAC is missed and detected within the first year of diagnosis of BE.12 Interestingly, there was a corresponding increase in visible lesion detection over the same period as well. Advanced histology among visible lesions was also found with higher frequency in recent years with almost 50% of visible lesions detected showing dysplasia or cancer during the 2010 to 2016 period. Although the mean age at BE diagnosis and the proportion of males increased over the years, BE length decreased over time. The trends in prevalent HGD/EAC did not change in a multivariate model when adjusted for age, sex, and other factors.

Our results showing increasing recognition of advanced histology as well as visible lesions on index endoscopy in patients with BE over the years provides evidence of improving efficiency in the earlier detection of neoplastic lesions and for a careful endoscopic examination during BE screening. These results are also consistent with previous epidemiologic studies that have shown that EAC is increasing with time,21–25 an increase that has been demonstrated not only in the United States but also in other western international cancer registries.3–6

There has been an increase in our clinical knowledge regarding BE neoplasia with studies showing the impact of BE inspection time13 and society recommendations of careful inspection during endoscopy, which could have played a major role in increased detection of dysplasia compared with a true increase in prevalence. It is difficult to control this factor due to the nature of the study design. Another important fact to consider in interpreting this trend is the advances in endoscopic techniques, such as high-definition endoscopes, and enhanced imaging, such as electronic chromoendoscopy. This may have led to further detailed examination of suspicious areas and increased yield in recent years. Unfortunately, due to limited reporting of such technology or when newer endoscopes were used, we were unable to study this effect. Finally, this could be due to an actual increase in the prevalence of HGD/EAC cases due to risk factors associated with neoplastic occurrence in BE, such as an aging population, increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease, increased obesity, and lower rates of Helicobacter pylori infection.2 This finding is echoed in other studies that have also looked at the trends of BE over the years. The incidence of BE appears to have increased substantially over the last 30 years with estimates of an increase from 65% between 1997 and 2002 to 159% between 1993 and 2005, with the greatest increase in those under 60 years of age.14,15 Other studies have also demonstrated that the incidence of EAC has risen >350% from the mid-1970s.26–29

Surprisingly, we observed that the increase in the prevalence of HGD/EAC was accompanied by a decrease in the mean length of BE. This has also been demonstrated in some studies that have shown that BE length may be decreasing over time. El-Serag et al30,31 reported that, between 1981 and 1985, mean BE length was 6 ± 3.8 cm, whereas in 1996 to 2000, mean BE length was 3.6 ± 2.9 cm. They also reported a decrease in the proportion of patients being diagnosed with BE >3 cm.32 Kendall and Whiteman28 found that the median length of long-segment BE decreased from 10 cm to 5 cm from 1990 to 1998 and 2002, and this was accompanied by an increase in the diagnosis of short-segment BE in that same time period.

The study results should be interpreted recognizing the following limitations. First, this is a retrospective analysis of data from tertiary referral centers over a long time span. Changing patient population, clinical practice, resolution of endoscopes and use of advanced technology at an individual center and likely experts in BE should be accounted for. As such, the study findings cannot be easily generalized. We could not assess the impact of newer endoscopes or advanced imaging if used because such information was not included in the data and not reported. Also, the impact of expertise at these referral centers in recognition of advanced pathology cannot be accounted for. We do not know whether the endoscopy was performed by a trainee or an experienced endoscopist. Another important criterion that we could not assess was the duration of the endoscopy procedure. Another important point is that the cohort is limited to patients diagnosed with BE, not those undergoing screening for BE. It is entirely possible that rates are declining among all patients screened for BE. Unfortunately, information on the number of biopsy samples obtained from each patient was not available over the time period, and whether sampling practices varied overtime remains unanswered. Finally, as the study was performed in tertiary care centers, our results may not accurately reflect results in community centers over this time span.

In conclusion, temporal trends analysis of 25 years of data from the largest U.S. registry of patients with BE show that the diagnosis of HGD and EAC has increased on index endoscopy. This highlights the importance of a meticulous inspection during screening endoscopy in patients with BE in light of the knowledge that prevalent EAC cases contribute to most EACs. The cause of this trend is still not entirely clear, and more studies are needed to explore the reasons behind it with the hope of detecting neoplasia in patients with BE and eradicating it to prevent esophageal cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURE: Dr Falk is a consultant for CDX and receives funding from Interscope. All other authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this publication.

Abbreviations:

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- CI

confidence interval

- EAC

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- HGD

high-grade dysplasia

- LGD

low-grade dysplasia

- NDBE

non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus

- OR

odds ratio

REFERENCES

- 1.Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:142–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider JL, Corley DA. The troublesome epidemiology of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2017;27:353–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK. The changing epidemiology of esophageal cancer. Semin Oncol 1999;26(5 Suppl 15):2–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botterweck AA, Schouten LJ, Volovics A, et al. Trends in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia in ten European countries. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vizcaino AP, Moreno V, Lambert R, et al. Time trends incidence of both major histologic types of esophageal carcinomas in selected countries, 1973–1995. Int J Cancer 2002;99:860–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord RV, Law MG, Ward RL, et al. Rising incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in men in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;13:356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/,based on November 2016. SEER data submission,posted to the SEER web site . Accessed April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhat S, Coleman HG, Yousef F, et al. Risk of malignant progression in Barrett’s esophagus patients: results from a large population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1049–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Gastroenterological Association; Spechler SJ, Sharma P, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1084–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:30–50; quiz 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visrodia K, Singh S, Krishnamoorthi R, et al. Magnitude of missed esophageal adenocarcinoma after Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2016;150:599–607 e7; quiz e14–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta N, Gaddam S, Wani SB, et al. Longer inspection time is associated with increased detection of high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76: 531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conio M, Cameron AJ, Romero Y, et al. Secular trends in the epidemiology and outcome of Barrett’s oesophagus in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gut 2001;48:304–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Soest EM, Dieleman JP, Siersema PD, et al. Increasing incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus in the general population. Gut 2005;54: 1062–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prach AT, MacDonald TA, Hopwood DA, et al. Increasing incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus: education, enthusiasm, or epidemiology? Lancet 1997;350:933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macdonald CE, Wicks AC, Playford RJ. Ten years’ experience of screening patients with Barrett’s oesophagus in a university teaching hospital. Gut 1997;41:303–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;140:e18–52; quiz e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thota PN, Vennalaganti P, Vennelaganti S, et al. Low risk of high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus less than 1 cm (irregular Z line) within 5 years of index endoscopy. Gastroenterology 2017;152:987–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Evans JA, Early DS, Fukami N, et al. The role of endoscopy in Barrett’s esophagus and other premalignant conditions of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76: 1087–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bosetti C, Levi F, Ferlay J, et al. Trends in oesophageal cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. Int J Cancer 2008;122:1118–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook MB, Chow WH, Devesa SS. Oesophageal cancer incidence in the United States by race, sex, and histologic type, 1977–2005. Br J Cancer 2009;101:855–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong CY, Kroep S, Curtius K, et al. Exploring the recent trend in esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality using comparative simulation modeling. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:997–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepage C, Rachet B, Jooste V, et al. Continuing rapid increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma in England and Wales. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2694–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman HG, Bhat S, Murray LJ, et al. Increasing incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus: a population-based study. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26: 739–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF Jr. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer 1998;83:2049–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendall BJ, Whiteman DC. Temporal changes in the endoscopic frequency of new cases of Barrett’s esophagus in an Australian health region. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thrift AP, Whiteman DC. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma continues to rise: analysis of period and birth cohort effects on recent trends. Ann Oncol 2012;23:3155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Serag HB, Aguirre T, Kuebeler M, et al. The length of newly diagnosed Barrett’s oesophagus and prior use of acid suppressive therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:1255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Serag HB, Garewel H, Kuebeler M, et al. Is the length of newly diagnosed Barrett’s esophagus decreasing? The experience of a VA Health Care System. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen T, Alsarraj A, El-Serag HB. Brief report: the length of newly diagnosed Barrett’s esophagus may be decreasing. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:418–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.