Introduction

To help eliminate perinatal HIV transmission, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) strongly recommends avoidance of breastfeeding for women living with HIV (WLHIV), regardless of maternal viral load or combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) status.1 However, cART radically improves HIV prognosis and virtually eliminates perinatal transmission, and breastfeeding’s benefits are well-established.2 As more US WLHIV are pursuing pregnancy, some breastfeed despite recommendations, for which a harm reduction approach is proposed.3 Conversely, breastfeeding is recommended for WLHIV in low-income-countries given high-quality randomized controlled trials demonstrating 1–2% total perinatal transmission and decreased child mortality with cART starting in the third trimester and continued during breastfeeding.4 However, these data come from settings where child mortality is high, largely from gastrointestinal and respiratory infections, and replacement feeding is often not “affordable, feasible, acceptable, sustainable or safe,” limiting generalizability to US populations.

To assess US policy, we conducted a critical review of primary, secondary, and gray literature relevant to perinatal transmission, risks, and potential health benefits of breastfeeding for infants and women in high-income settings. US health surveillance data, government and professional society guidelines were reviewed.5 Pubmed, EMBASE, Cochrane, Web of Science and Google searches were performed in 10/2016 and periodically updated through 9/2018. Scoping review of literature cited in official documents and review articles was performed. MG conducted the review; findings were vetted by HT, CT, and JC in their respective areas of expertise. Supporting data and nonessential references are included in an online supplement due to space constraints at journals.sagepub.com/home/lme.

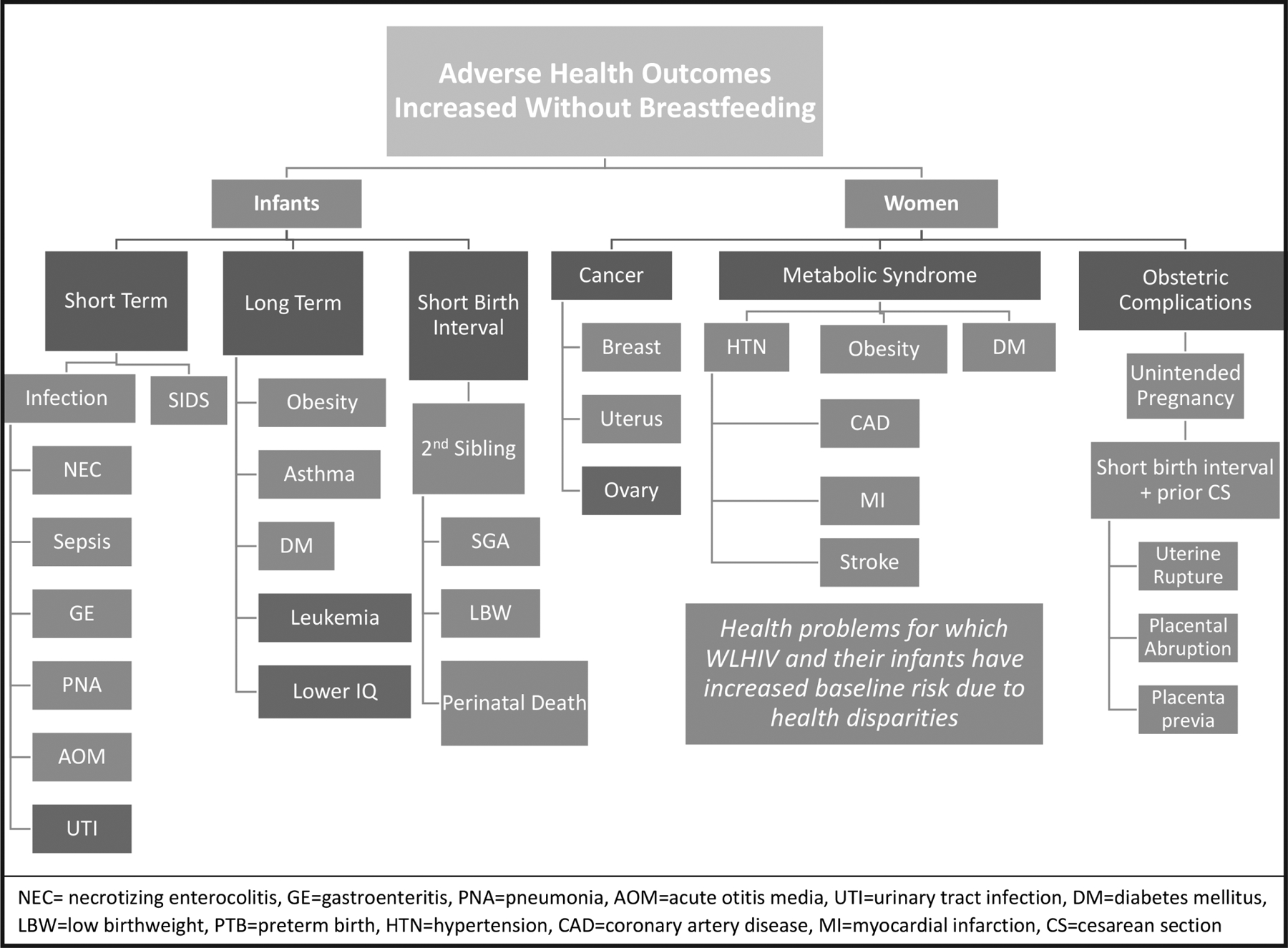

First, we delineate the risk of HIV transmission from breastfeeding for HIV-exposed US infants. Next, we delineate the risks to this same population of children if they are not breastfed, including excess mortality from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and sepsis. We then discuss maternal health considerations. We conclude that strict avoidance of breastfeeding by WLHIV may not maximize health outcomes, particularly given existing infant and maternal health disparities (see Figure 1). Supported by ethical considerations of autonomy, harm reduction, and social justice, we suggest eliminating the categorical recommendation against breastfeeding for cART-adherent WLHIV.

Figure 1.

Health risks of not breastfeeding for United States women living with HIV and their infants

Clinical Considerations6

Risk of Perinatal HIV from Breastfeeding

Perinatal transmission in high-income-countries continues to decrease with more effective, tolerable cART and treatment upon HIV diagnosis, including in pregnancy.7 Approximately 8700 (95% CI: 8400–8800) US WLHIV deliver annually.8 In 2014 an estimated 63 infants (0.8%) contracted perinatal HIV.9 However, viral load (VL) is the greatest predictor of perinatal transmission, and infants whose mothers have detectable VL (>50 copies/ml) are disproportionately affected.10 Factors that increase the risk of perinatal transmission include high VL, as in acute HIV during pregnancy or breastfeeding, non-adherence with cART, inadequate prenatal care, injection drug use, substance use, CD4 T cell count <200, age ≤24, genital infections, and not receiving DHHS recommended antepartum cART, intrapartum care, or postpartum infant prophylaxis.11

Conversely, cART-adherent women with undetectable VL near delivery have very low perinatal transmission rates, e.g. 0.05% from 2000–2011 per United Kingdom/Ireland national surveillance data.12 Those who transmit HIV despite attaining undetectable VL before delivery have significant obstetrical risks, such as premature rupture of membranes of unknown duration in the setting of placenta previa, placental abruption, or preterm delivery shortly after achieving virologic control.13 Initiation of cART early in pregnancy further reduces transmission, irrespective of VL. A French national cohort had 0.2% transmission with preconception cART vs. 0.4%, 0.9%, and 2.2% with first, second, or third trimester initiation.14 The DHHS states that VL should be undetectable on cART before attempting conception.15 In France (n=2615) and United Kingdom/Ireland (n=1894), transmission was 0.0% with preconception cART and undetectable VL near delivery.16

However, evidence above does not account for risk of breastmilk transmission, since high-income governments recommend WLHIV avoid breastfeeding. These policies have discouraged the study of breastfeeding outcomes in high-income settings, and current US perinatal HIV exposure data are insufficient for guiding practice.17 For example, a chart review of HIV-exposed infants found that perinatal HIV was more common among the 1% (80/8054) who breastfed (aOR 4.6, 95% CI 2.2–9.8), however key details like maternal VL were omitted.16 Meanwhile, in our 2016 survey, 33% of providers reported having patients who breastfeed despite recommendations, and latest US guidelines have introduced a harm reduction approach, suggesting possible ascertainment bias in the review above in which perinatal HIV cases may have been more likely to have their breastfeeding status exposed.19 Surreptitious breastfeeding and coincident nonadherence with other perinatal HIV recommendations may further confound the picture, though a harm reduction approach may attenuate these concerns moving forwards.

In contrast, a 2011 systematic review found 8 studies from low-income settings in which breastfeeding for 6 months was associated with 0–1% perinatal transmission (n=3202).20 In Mma Bana, the largest cohort in the review, 709 women initiated cART between 26–34 weeks of pregnancy, and at 6 months postpartum there were two breastmilk transmissions (0.3%): one mother was non-adherent with medications, and the other had VL >170,000, delivered prematurely, and breastfed before achieving viral suppression.21 One meta-analysis was identified which included 6 studies (n=2109) with pooled transmission of 1.08% (95% CI 0.32–1.85) over 6 months of breastfeeding, though this was deemed “very low” quality evidence, and applicability to US population is limited by absent VL or adherence data, late initiation of cART, and lack of standard postnatal infant prophylaxis.22 The more recent PROMISE study (n=2431) also found 0.3% transmission through 6 months of breastfeeding.23 Breastmilk transmission in high-income settings may be similar, and cART-adherence with undetectable VL may virtually eliminate transmission risk, much as it has from pregnancy and delivery.

Health Benefits of Breastfeeding for Infants

Breastfeeding decreases major causes of US infant mortality, including SIDS and complications of prematurity.24 In a meta-analysis of 23 studies, SIDS was half as likely among breastfed vs. formula-fed infants.25 NEC and sepsis have highest incidence among non-breastfed premature and low birthweight infants, and mortality is inversely related to weight and gestational age.26 Prematurity and low birthweight affects 11.4% and 8.2% of US infants, respectively, and breastfeeding decreased NEC 58% in four randomized-controlled trials and urosepsis 69% in a large preterm cohort.27 A UK study modeling preterm infant feeding estimated 190 excess deaths from NEC or sepsis annually if no premature infants breastfeed (n=51,703).28

Notably, black infants suffer 2.2-fold mortality (3.5-fold preterm-related death) and black women have twentyfold higher incidence of HIV when compared to white counterparts.29 Thus, accounting for existing health disparities is critical for appreciating potential benefits of breastfeeding in this population. For example, SIDS causes 38.7 deaths/100,000 US livebirths, but 74.0/100,000 for black infants.30 HIV-exposed US infants are also more likely to have low birthweight (22.9%, n=980) or be preterm (18.6% overall, and 21% among women receiving cART in the first trimester; n=1869).31 If US WLHIV breastfed, there may be significantly fewer SIDS and prematurity-associated deaths among their infants.

Breastfeeding also prevents potentially fatal gastroenteritis (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.18–0.74) and hospitalization for respiratory infections (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.14–0.54) for US infants.32 Acute otitis media, which affects ˂80% under 3 years, is decreased 50% with breastfeeding.33 Victora et al. presented confounder-adjusted meta-analyses showing: 35% reduction in type 2 diabetes; 13% lower rate of overweight/obesity; 9% reduction in asthma; 19% reduction of childhood leukemia; and, an increase in child intelligence quotient (IQ) of 3.4 points.34 Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life with continued breastfeeding for at least the first year is the most effective strategy for conferring these benefits, and is the normative standard for infant feeding in high income settings.

Weighing Risks and Benefits for Infants

To determine the best feeding method for HIV-exposed US infants, we must reconcile the hypothetical increased duration of perinatal transmission risk with current excess health risks from lack of breastfeeding, as outlined above.35 First, while breastmilk transmission in low-income-countries is <1% with cART, many of the data come from clinical trials, which may affect cART-adherence by providing medications and other support. For example, in Mma Bana >90% achieved and maintained viral suppression during pregnancy and 6 months of breastfeeding.36 Although cART uptake among US WLHIV is increasing over time, adherence remains suboptimal: population-based data from New York State 2008–2010 (n=980) demonstrated that only 75% were virally suppressed at delivery, and among those, just 44% remained suppressed one year postpartum.37 Retrospective studies from Mississippi and Philadelphia found that <40% were optimally engaged in HIV care throughout the year after delivery.38 Postpartum non-adherence to cART and loss to care among US WLHIV yield significant concerns about the safety of breastfeeding for their infants.

Simultaneously, data demonstrate how HIV diagnosis >2 years before pregnancy, preconception HIV care, early and adequate prenatal care, older maternal age, viral suppression at delivery and low infant birthweight, among other factors, can predict postpartum retention in care and sustained viral suppression.39 Documented breastmilk transmissions appear to occur with cART nonadherence, detectable VL, or loss to follow up, and known risk factors could inform individualized infant feeding recommendations. Momplaisir et al. highlight the interpersonal, community and health systems-level issues impacting postpartum retention, suggesting a five-pronged approach to improve outcomes.40 Importantly, a substantial proportion of US WLHIV do maintain ongoing viral suppression, and breastfeeding itself may increase postpartum cART-adherence by prolonging unified maternal and child interests. Development of clinical algorithms to identify candidates for breastfeeding, and support for postpartum retention in HIV care would be crucial for introducing personalized feeding recommendations for HIV-exposed US infants.

Notably, in the US, perinatal HIV is a serious, but chronic disease with very low mortality (0.05/100 child-years) and morbidity dominated by treatment side-effects.41 Thus, breastmilk transmission of HIV may not substantially impact infant mortality, and any increased HIV-morbidity might be compensated for by breastfeeding’s health benefits. One concern regarding potential HIV-related morbidity is risk of genotypic resistance for perinatally infected infants whose mothers breastfeed without viral suppression. However, this is less likely to impact US infants, as it has occurred among low-income-countries among infants, including those infected antepartum/intrapartum, who received prolonged antiretroviral prophylaxis for breastfeeding in lieu of maternal cART or whose mothers first initiated cART postpartum.42

Finally, regarding theoretical increased drug toxicity for infants via breastmilk or prolonged prophylaxis, studies have shown that severe adverse events (SAEs) are equally rare for 1 vs. 28 weeks of breastmilk exposure, and found no differences between breastfeeding infants receiving 6 weeks vs. 6 months of prophylaxis.43 While infant antiretroviral prophylaxis and breastmilk exposure appear safe and well tolerated, recommendations for optimal maternal treatment and infant prophylaxis during breastfeeding and weaning in US populations continue to evolve.44

Overall, the significant benefits of breastfeeding may outweigh risks for infants of cART-adherent US WLHIV. Likewise, while 6 months of breastfeeding may confer the majority of benefits with acceptably low risk, the duration of breastfeeding that would optimize risks/benefits for infants is beyond the scope of this discussion, but important to address. A statistical model would be helpful for extrapolating how alternative feeding recommendations would impact morbidity and mortality for HIV-exposed US infants.

Health Benefits of Breastfeeding for Women

Breastfeeding also affects leading causes of US women’s mortality, including heart disease (#1), cancer (#2), diabetes (#7), and hypertension (#13).45 In the Nurses’ Health Study (n= 89,326), 2 years of cumulative breastfeeding reduced myocardial infarction by 23%, and any breastfeeding decreased hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia, with direct doseresponse.46 Breastfeeding also decreases stroke by 23%.47 Meta-analysis showed that breastfeeding decreased type 2 diabetes by 32% (RR 0·68, 95% CI 0·57–0·82).48 Breastfeeding consumes ~480 kcal/day, increasing postpartum weight loss, and body mass index was 1% lower per 6 months of breastfeeding among 740,000 British women.49

Breast cancer is US women’s most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer death.50 Victora et al. report adjusted metaanalyses demonstrating 7% reduction of invasive breast cancer with breastfeeding in high-income-countries, and worldwide premenopausal breast cancer decreased 4.3% per year of breastfeeding.51 Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of US women’s cancer death, and breastfeeding reduces risk by 30%.52 In a 2017 meta-analysis, risk of endometrial cancer, the most common gynecologic malignancy among US women, was decreased 11% with breastfeeding.53

Per the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “underserved women are disproportionately likely to experience adverse health outcomes that may improve with breastfeeding.”54 WLHIV are predominantly socioeconomically disadvantaged women of color, and avoiding breastfeeding compounds their already increased obesity, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and cancer risks.55 For example, black women are especially susceptible to hormone-and-triple-negative breast cancers, whereas breastfeeding could decrease that risk by 19%.56 While causality remains unclear, postpartum depression has a strong inverse relationship to breastfeeding, and current guidelines may worsen WLHIV’s undue psychiatric morbidity.57

Lastly, exclusive breastfeeding induces lactational amenorrhea, preventing 98% of pregnancies for six months.58 This significantly reduces risks of subsequent short interval pregnancies: maternal and infant death, uterine rupture, placental abruption, placenta previa, preterm rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction and premature delivery.59 WLHIV, like many minority and low-income women, disproportionately experience unintended pregnancies and their sequelae.60 Ultimately, breastfeeding protects US women’s health, and recommending against breastfeeding especially harms minority and low-income women.

Ethical Considerations

Autonomy

Our review illustrates the clinical equipoise regarding optimal feeding practices for US WLHIV.61 Critically, the prevailing argument that curtailing women’s autonomy is justified given the value of protecting infants’ best interests is undermined by the potential benefits of breastfeeding for infants whose mothers maintain undetectable VL. The addition of “patient-centered, evidence-based counseling” for women who question the recommendation against breastfeeding and harm reduction strategies for “when women with HIV choose to breastfeed despite intensive counseling” make major strides towards respecting women’s autonomy.62 However, discussing breastfeeding as a matter of maternal “choice” may trivialize the health benefits that infants and women stand to gain. Yet, current guidelines state that “breastfeeding is not recommended [sic]” and prompt providers to address “potential barriers to formula feeding,” falling short of the genuine shared-decision making clinical equipoise enjoins.63

While DHHS recommendations do not have the force of law, legal authority has loomed large for WLHIV who attempt to breastfeed.64 The American Academy of Pediatrics has suggested the “rare circumstance” in which women with undetectable VL on cART may breastfeed “despite intensive counseling” without constituting “grounds for automatic referral to Child Protective Services.”65 Women cannot make free, informed choices if they fear breastfeeding may jeopardize parental rights, particularly when “intensive counseling” continues immediately-postpartum, when lactation support is critical for successful breastfeeding. Telling women not to breastfeed may also subject them to social pressure, grief, shame, and guilt, further curtailing maternal autonomy.66

The availability of safe formula in the US is cited as justification for the recommendation against breastfeeding for WLHIV.67 Instead, donor human milk and formula could be a part of a shared decision-making framework that could facilitate informed collaboration between WLHIV and their physicians.68 Frequent healthcare visits during pregnancy and infancy allows for ongoing risk-benefit assessments and close monitoring. Anticipatory guidance and heightened surveillance paired with skilled breastfeeding support help minimize transmission risk, for example, by promoting early detection of mastitis and prompting unilateral pumping and discarding of breastmilk during acute infection.69 Recent updates to DHHS guidelines offer support for WLHIV who breastfeed “despite intensive counseling” and provide valuable practical guidance for providers regarding postpartum management. However, clinical equipoise regarding infants’ interests suggests that the recommendation against breastfeeding may be replaced with individualized, evidence-based recommendations and strategies to promote cART-adherence.

Harm Reduction

Acknowledging that a wide range of factors, from familial pressures and stigma to awareness of health benefits and desire for bonding, may lead WLHIV to breastfeed contrary to US recommendations, Levison and others have promoted a harm reduction approach.70 They argue that a hardline stance against breastfeeding may increase perinatal transmission by prompting some to conceal their choice from providers and others to avoid treatment altogether.71 They emphasize replacement feeding as optimal, but suggest exclusive breastfeeding with cART for “those who decide to breastfeed despite being fully informed of the risks.” Harm reduction compassionately recognizes the difficult, often complex choices individual WLHIV face. Critically, its adoption may assuage providers’ fear of legal or professional repercussions from promoting informed feeding choices. However, harm reduction and current DHHS Recommendations treat breastfeeding with HIV as a harm, and thus may not be the appropriate framework for approaching this issue. First, with cART-induced viral suppression, breastfeeding’s health benefits may outweigh its risks, whereas avoiding breastfeeding may cause net harm. Likewise, routine cesarean delivery for WLHIV was discontinued given evidence that iatrogenic harms from surgery outweighed marginal reductions in perinatal transmission when risk was already very low due to maternal virologic control.72 Further-more, retaining the expectation that WLHIV avoid breastfeeding and asserting that breastfeeding is “reasonable but inferior,” introduces judgement that may unintentionally jeopardize forthright patient-provider interactions, compromising both shared decision-making and the disclosure required for breastfeeding women to participate in observational studies. Finally, 84% of HIV healthcare providers have stated that they would require government and/or professional society guidelines before supporting breastfeeding among WLHIV with undetectable VL, and the DHHS continues to strongly recommend against breastfeeding. It is unclear whether acceptance of harm reduction truly satisfies those criteria for individual providers or if it will lead to corresponding updates in hospital and health system policies.73 In this regard, harm reduction may be insufficient to substantially change practice, promote informed decisions or close evidence gaps.

Health and Socioeconomic Inequities

Current recommendations against breastfeeding likely further disadvantage already disadvantaged women and infants, largely due to existing socioeconomic and racial disparities. Unfortunately, minority women suffer disproportionately from diseases breastfeeding may prevent, such as obesity, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, depression, and female cancers.74 Additionally, current policy imposes financial hardship via formula’s costs, including loss of Women Infant and Children (WIC)’s breastfeeding incentives, and lost wages due to infant or maternal illness.75 Ironically, WLHIV who adhere to healthcare recommendations generally are least likely to transmit HIV and most likely to experience current recommendations as unjust. The extent to which postpartum adherence can be addressed by increasing awareness, care coordination, peer-and-technology-based interventions, and long-acting cART formulations puts the onus on the US healthcare system to close gaps that undermine WLHIV’s access to breastfeeding’s benefits.

Further, HIV-exposed US infants disproportionately experience health risks that could be mitigated by breastfeeding. In 2013, mortality for black infants was more than double that of white infants, chiefly attributed to greater burdens of prematurity and SIDS.76 Since preconception cART is associated with prematurity and low birthweight, the HIV-exposed infants least likely to contract HIV are most likely to be harmed by not breastfeeding.77 Socioeconomically disenfranchised infants would especially benefit from decreased diabetes, obesity, and asthma, plus a higher IQ with corresponding adult educational attainment and income. While donor breastmilk may partially alleviate consequences of current policy, most HIV-exposed infants do not have access to banked milk, and breastfeeding itself is more beneficial, feasible, and cost-effective.78 Discouraging WLHIV from breastfeeding may inadvertently contribute to poor health outcomes among vulnerable infants and women, systematically reinforcing racial inequity by deepening disparities in health and wealth.79

Conclusion and Recommendations

Given potential benefits of breastfeeding and very low perinatal transmission risk with undetectable VL, breast may be best for infants of cART-adherent WLHIV. As with decisions about having children, WLHIV have a right to make an informed choice about breastfeeding, especially given clinical equipoise regarding infant outcomes, maternal health considerations and personal significance. Additionally, women and select HIV-exposed infants may be harmed by avoiding breastfeeding, and further policy change may be required to fully support shared-decision making, necessitating an approach beyond harm reduction. Finally, avoiding breastfeeding may inadvertently increase health inequities by further disadvantaging WLHIV and their infants.

We suggest DHHS recommendations include breastfeeding as an option for cART-adherent WLHIV who maintain undetectable VL, ideally within a prospective cohort emphasizing informed consent and close observation. Clinical tools should be developed to help providers identify dyads who may safely breastfeed and to facilitate shared-decision making, and care should be taken to ensure that patient counseling is unbiased and evidence-based. Case management should ensure ongoing cART access, and donor milk or, if unavailable, formula should be subsidized when breastfeeding is not recommended or desired.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Transmission in the United States, available at <http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/PerinatalGL.pdf> (last accessed February 1, 2019);; Committee on Pediatric Aids, “Infant Feeding and Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus in the United States,” Pediatrics 131, no. 2 (2013): 391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, Murch S, et al. “Breastfeeding in the 21st Century: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Lifelong Effect,” Lancet 387, no. 10017 (2016): 475–490; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, Trikalinos T, and Lau J “Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries,” Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 153, no. 153 (2007): 1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1;; Whitmore SK, Zhang X, Taylor AW, and Blair JM, “Estimated Number of Infants Born to HIV-Infected Women in the United States and Five Dependent Areas, 2006,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 57, no. 3 (2011): 218–222; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yudin MH, Kennedy VL, and MacGillivray SJ, “HIV and Infant Feeding in Resource-Rich Settings: Considering the Clinical Significance of a Complicated Dilemma,” AIDS Care 28, no. 8 (2016): 1023–1026; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Levison J, Weber S, and Cohan D. “Breastfeeding and HIV-Infected Women in the United States: Harm Reduction Counseling Strategies,” Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 59, no. 2 (2014): 304–309; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Johnson G, Levison J, and Malek J, “Should Providers Discuss Breastfeeding with Women Living with HIV in High-Income Countries? an Ethical Analysis,” Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (2016); [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Morrison P, Israel-Ballard K, and Greiner T, “Informed Choice in Infant Feeding Decisions can be Supported for HIV-Infected Women Even in Industrialized Countries,” AIDS 25, no. 15 (2011): 1807–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund, Guideline: Updates on HIV and Infant Feeding: The Duration of Breastfeeding, and Support from Health Services to Improve Feeding Practices among Mothers Living with HIV, Geneva, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant MJ and Booth A, “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies,” Health Information and Libraries Journal 26, no. 2 (2009): 91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1.

- 7.Townsend CL, Byrne L, Cortina-Borja M, Thorne C, de Ruiter A, Lyall H, Taylor GP, Peckham CS, and Tookey PA, “Earlier Initiation of ART and further Decline in Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission Rates, 2000–2011,” AIDS 28, no. 7 (2014): 1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitmore et al, supra note 3.

- 9.Taylor AW, Nesheim SR, Zhang X, Song R, FitzHarris LF, Lampe MA, Weidle PJ, and Sweeney P, “Estimated Perinatal HIV Infection among Infants Born in the United States, 2002–2013,” JAMA Pediatrics 171, no. 5 (2017): 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camacho-Gonzalez AF, Kingbo MH, Boylan A, Eckard AR, Chahroudi A, and Chakraborty R, “Missed Opportunities for Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission in the United States,” AIDS 29, no. 12 (2015): 1511–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Id.;; Mandelbrot L, Tubiana R, Le Chenadec J, Dollfus C, Faye A, Pannier E, Matheron S, et al. , “No Perinatal HIV-1 Transmission from Women with Effective Antiretroviral Therapy Starting before Conception,” Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 61, no. 11(2015): 1715–1725; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Whitmore SK, Taylor AW, Espinoza L, Shouse RL, Lampe MA, and Nesheim S, “Correlates of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in the United States and Puerto Rico,” Pediatrics 129, no. 1 (2012): 74; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brady KA, Kathleen, Storm DS, Naghdi A, Frederick T, Fridge J, and Hoyt MJ “Perinatal HIV Exposure Surveillance and Reporting in the United States, 2014,” Public Health Reports 132, no. 1 (2017): 76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Townsend et al. , supra note 7.

- 13.Camacho-Gonzalez et al. , supra note 10.

- 14.Mandelbrot et al. , supra note 11.

- 15.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1.

- 16.Townsend et al. , supra note 7;; Mandelbrot et al. , supra note 11.

- 17.Brady et al. , supra note 11.

- 18.Whitmore et al. , supra note 11.

- 19.Gross MS, Tomori C, Tuthill E, Sibinga EMS, Anderson J, and Coleman JS, “US Healthcare Providers Survey on Breastfeeding Among Women Living with HIV,” Oral presentation at: 7th International Workshop on HIV & Women, 2017, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, Kitch D, Lockman S, Moffat C, Makhema J, et al. 2010. “Antiretroviral Regimens in Pregnancy and Breast-Feeding in Botswana.” New England Journal of Medicine 362, no. 24: 2282–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brady et al. , supra note 11.

- 22.Bispo S, Chikhungu L, Rollins N, Siegfried N, and Newell ML, “Postnatal HIV Transmission in Breastfed Infants of HIV-Infected Women on ART: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of the International AIDS Society 20, no. 1 (2017): 21251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn PM, Taha TE, Cababasay M, Fowler MG, Mofenson LM, Owor M, Fiscus S, et al. , “Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission through Breastfeeding: Efficacy and Safety of Maternal Antiretroviral Therapy Versus Infant Nevirapine Prophylaxis for Duration of Breastfeeding in HIV-1-Infected Women with High CD4 Cell Count (IMPAACT PROMISE): A Randomized, Open-Label, Clinical Trial,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 77, no. 4 (2018): 383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Victora et al. , supra note 2;; Ip et al. , supra note 2;; Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, and Thoma ME, “Infant Mortality Statistics from the 2013 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set,” National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System 64, no. 9 (2015): 1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ip et al. , supra note 2.

- 26.Ip et al. , supra note 2;; Matthews et al. , supra note 24;; Levy I, Comarsca J, Davidovits M, Klinger G, Sirota L, and Linder N, “Urinary Tract Infection in Preterm Infants: The Protective Role of Breastfeeding,” Pediatric Nephrology 24, no. 3 (2009): 527–531; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mahon J, Claxton L, and Wood H, “Modelling the Cost-Effectiveness of Human Milk and Breastfeeding in Preterm Infants in the United Kingdom,” Health Economics Review 6 (2016): 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ip et al. , supra note 2;; Levy et al. , supra note 26.

- 28.Mahon et al. , supra note 26.

- 29.Matthews et al. , supra note 24;; Johnson AS, Beer L, Sionean C, Hu X, Furlow-Parmley C, Le B, Skarbinski J, Hall HI, and Dean HD, “HIV Infection — United States, 2008 and 2010,” MMWR Supplements 62, no. 3 (2013): 112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, and Tejada-Vera B, “Deaths: Final Data for 2014,” National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System 65, no. 4 (2016): 1–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watts DH, Williams PL, Kacanek D, Griner R, Rich K, Hazra R, Mofenson LM, Mendez HA, and Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study, “Combination Antiretroviral use and Preterm Birth.,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases 207, no. 4 (2013): 612–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ip et al. , supra note 2;; Kochanek et al. , supra note 30.

- 33.Ip et al. , supra note 2.

- 34.Victora et al. , supra note 2.

- 35.Azad MB., Vehling L, Chan D, Klopp A, Nickel NC, McGavock JM, Becker AB,et al. , “Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk from Breastfeeding and Formula from Food,” Pediatrics 142, no. 4 (2018), doi:e20181092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shapiro et al. , supra note 20.

- 37.Azad et al. , supra note 35.

- 38.Swain CA, Smith LC, Nash D, Pulver WP, Lazariu V, Anderson BJ, Warren BL, Birkhead GS, and McNutt LA, “Postpartum Loss to HIV Care and HIV Viral Suppression among Previously Diagnosed HIV-Infected Women with a Live Birth in New York State,” PloS One 11, no. 8 (2016): e0160775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Id., Momplaisir FM, Storm DS, Nkwihoreze H, Jayeola O, and Jemmott JB, “Improving Postpartum Retention in Care for Women Living with HIV in the United States,” AIDS 32, no. 2 (2018): 133–142; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bengtson AM, Chibwesha CJ, Westreich D, Mubiana-Mbewe M, Chi BH, Miller WC, Mapani M, et al. , “A Risk Score to Identify HIV-Infected Women most Likely to Become Lost to Follow-Up in the Postpartum Period,” AIDS Care 28, no. 8 (2016): 1035.-; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Davis NL, Miller William C., Hudgens Michael G., Chasela Charles S., Sichali Dorothy, Kayira Dumbani, Nelson Julie A. E., et al. , “Maternal and Breastmilk Viral Load: Impacts of Adherence on Peripartum HIV Infections Averted-the Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition Study,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 73, no. 5 (2016): 572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Momplaisir et al. , supra note 39.

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “HIV Surveillance Report, 2015,” 2016, available at <http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html> (last accessed February 6, 2019);; Berti E, Thorne C, Noguera-Julian A, Rojo P, Galli L, de Martino M, and Chiappini E,“The New Face of the Pediatric HIV Epidemic in Western Countries: DemographicCharacteristics, Morbidity and Mortality of the Pediatric HIV-Infected Population,” The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 34 no. 5 Suppl 1 (2015): 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White AB, Mirjahangir JF, Horvath H, Anglemyer A, and Read JS, “Antiretroviral Interventions for Preventing Breast Milk Transmission of HIV,” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews no. 10 (2014): CD011323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Updates on HIV and Infant Feeding: The Duration of Breastfeeding, and Support from Health Services to Improve Feeding Practices among Mothers Living with HIV, supra note 4; [PubMed]; Beste S, Essajee S, Siberry G, Hannaford A, Dara J, Sugandhi N, and Penazzato M, “Optimal Antiretroviral Prophylaxis in Infants atHigh Risk of Acquiring HIV: A Systematic Review,” The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 37, no. 2 (2018): 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1;; Waitt C, Low N, Van de Perre P, Lyons F, Loutfy M, and Aebi-Popp K, “Does U=U for Breastfeeding Mothers and Infants? Breastfeeding by Mothers on Effective Treatment for HIV Infection in High-Income Settings,” The Lancet HIV 5, no. 9 (2018): e531–e536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kochanek et al. , supra note 30.

- 46.Stuebe AM, Michels KB, Willett WC, Manson JE, Rexrode K, and Rich-Edwards JW, “Duration of Lactation and Incidence of Myocardial Infarction in Middle to Late Adulthood,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 200, no. 2 (2009): 138.e1–138.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobson LT, Hade EM, Collins TC, Margolis KL, Waring ME, Van Horn LV, Silver B, Sattari M, Bird CE, and Kimminau K, “Breastfeeding History and Risk of Stroke among Parous Postmenopausal Women in the Women’s Health Initiative,” Journal of the American Heart Association 7, no. 17 (2018): e008739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Victora et al. , supra note 2.

- 49.Victora et al. , supra note 2;; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women’s Health Care Physicians and Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, “Committee Opinion no. 570: Breastfeeding in Underserved Women: Increasing Initiation and Continuation of Breastfeeding,” Obstetrics and Gynecology 122, no. 2 Pt 1 (2013): 423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kochanek et al. , supra note 30.

- 51.Victora et al. , supra note 2.

- 52.Victora et al. , supra note 2;; Kochanek et al. , supra note 30.

- 53.Jordan SJ, Na R, Johnatty SE, Wise LA, Adami HO, Brinton LA, Chen C, et al. , “Breastfeeding and Endometrial Cancer Risk: An Analysis from the Epidemiology of Endometrial Cancer Consortium,” Obstetrics and Gynecology 129, no. 6 (2017): 1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women’s Health Care Physicians and Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, supra note 49.

- 55.Johnson et al. , supra note 29;; “HIV Surveillance Report, 2015,” supra41.

- 56.Islami F, Liu Y, Jemal A, Zhou J, Weiderpass E, Colditz G, Boffetta P, and Weiss M, “Breastfeeding and Breast Cancer Risk by Receptor Status — a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 26, no. 12 (2015): 2398–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Victora et al. , supra note 2;; Orza L, Bewley S, Logie CH, Crone ET, Moroz S, Strachan S, Vazquez M, and Welbourn A, “How does Living with HIV Impact on Women’s Mental Health? Voices from a Global Survey,” Journal of the International AIDS Society 18, no. Suppl 5 (2015): 20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Labbok MH, “Postpartum Sexuality and the Lactational Amenorrhea Method for Contraception,” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 58, no. 4 (2015): 915–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, and Kafury-Goeta AC, “Effects of Birth Spacing on Maternal Health: A Systematic Review,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 196, no. 4 (2007): 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women’s Health Care Physicians and Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, supra note 49.

- 61.Waitt et al. , supra note 44;; Kahlert C, Aebi-Popp K, Bernasconi E, de Tejada BM, Nadal D, Paioni P, Rudin C, Staehelin C, Wagner N, and Vernazza P, “Is Breastfeeding an Equipoise Option in Effectively Treated HIV-Infected Mothers in a High-Income Setting?” Swiss Medical Weekly 148 (2018): w14648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1.

- 63.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1.

- 64.Walls T, Palasanthiran P, Studdert J, Moran K, and Ziegler JB, “Breastfeeding in Mothers with HIV,” Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 46, no. 6 (2010): 349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Committee on Pediatric Aids, supra note 1.

- 66.Tariq S, Elford J, Tookey P, Anderson J, de Ruiter A, O’Connell R, and Pillen A, “‘It Pains Me because as a Woman You have to Breastfeed Your Baby’: Decision-Making about Infant Feeding among African Women Living with HIV in the UK,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 92, no. 5 (2016): 331–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1.

- 68.Barry MJ and Edgman-Levitan S. “Shared Decision Making — Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care,” The New England Journal of Medicine 366, no. 9 (2012): 780–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1.

- 70.Levison et al. , supra note 3;; Johnson et al. , supra note 3.

- 71.Levison et al. , supra note 3.

- 72.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, supra note 1;; Morrison et al. , supra note 3.

- 73.Gross et al. , supra note 19.

- 74.Jacobson et al. , supra note 47;; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women’s Health Care Physicians and Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, supra note 49;; Jordan et al. , supra note 53;; Islami et al. , supra note 56.

- 75.Karpf B, Smith G, and Spink R, “Affording formula: HIV+ women’s experiences of the financial strain of infant formula feeding in the UK,” Oral presentation at 23rd Annual Conference of British HIV Association, April 7, 2017; [Google Scholar]; Shafai T, Mustafa M, and Hild T, “Promotion of Exclusive Breastfeeding in Low-Income Families by Improving the WIC Food Package for Breastfeeding Mothers,” Breastfeeding Medicine: The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine 9, no. 8 (2014): 375–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matthews et al. , supra note 24.

- 77.Watts et al. , supra note 31.

- 78.Azad et al. , supra note 35;; Committee on Nutrition, Section on Breastfeeding, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. “Donor Human Milk for the High-Risk Infant: Preparation, Safety, and Usage Options in the United States,” Pediatrics 139, no. 1 (2017): 3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eichelberger KY, Doll K, Ekpo GE, and Zerden ML, “Black Lives Matter: Claiming a Space for Evidence-Based Outrage in Obstetrics and Gynecology,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 10 (2016): 1771–1772; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bartick MC, Jegier BJ, Green BD, Schwarz EB, Reinhold AG, and Stuebe AM, “Disparities in Breastfeeding: Impact on Maternal and Child Health Outcomes and Costs,” The Journal of Pediatrics 181 (2017): 55.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]