Abstract

apoB exists as apoB100 and apoB48, which are mainly found in hepatic VLDLs and intestinal chylomicrons, respectively. Elevated plasma levels of apoB-containing lipoproteins (Blps) contribute to coronary artery disease, diabetes, and other cardiometabolic conditions. Studying the mechanisms that drive the assembly, intracellular trafficking, secretion, and function of Blps remains challenging. Our understanding of the intracellular and intraorganism trafficking of Blps can be greatly enhanced, however, with the availability of fusion proteins that can help visualize Blp transport within cells and between tissues. We designed three plasmids expressing human apoB fluorescent fusion proteins: apoB48-GFP, apoB100-GFP, and apoB48-mCherry. In Cos-7 cells, transiently expressed fluorescent apoB proteins colocalized with calnexin and were only secreted if cells were cotransfected with microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. The secreted apoB-fusion proteins retained the fluorescent protein and were secreted as lipoproteins with flotation densities similar to plasma HDL and LDL. In a rat hepatoma McA-RH7777 cell line, the human apoB100 fusion protein was secreted as VLDL- and LDL-sized particles, and the apoB48 fusion proteins were secreted as LDL- and HDL-sized particles. To monitor lipoprotein trafficking in vivo, the apoB48-mCherry construct was transiently expressed in zebrafish larvae and was detected throughout the liver. These experiments show that the addition of fluorescent proteins to the C terminus of apoB does not disrupt their assembly, localization, secretion, or endocytosis. The availability of fluorescently labeled apoB proteins will facilitate the exploration of the assembly, degradation, and transport of Blps and help to identify novel compounds that interfere with these processes via high-throughput screening.

Keywords: apolipoprotein B, very low density lipoproteins, low density lipoproteins, chylomicrons

Lipoproteins are noncovalently held assemblies of lipids and proteins that resemble micelles. They play a physiological role in the transport of hydrophobic lipids and fat-soluble vitamins throughout the lymph and bloodstream for utilization or storage by peripheral tissues (1). Lipoproteins are composed of a core consisting of triglyceride and cholesteryl esters surrounded by a monolayer composed of phospholipids, free cholesterol, and various apolipoproteins. ApoB is a very large, amphipathic, nonexchangeable apolipoprotein that is a structural component of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, including chylomicrons (CMs) and VLDLs (2). Full-length apoB, apoB100, is a 512 kDa protein that is synthesized in mammalian livers and is the major apolipoprotein found in VLDL (3). In the mammalian intestine and in rodent livers, an mRNA editing enzyme (apobec1) converts the cytidine at position 6666 of apoB mRNA to uracil, creating a premature stop codon (4, 5). This edited mRNA is translated into a truncated form of apoB, apoB48, a 246 kDa protein consisting of the N-terminal 48% of apoB100. ApoB48 is the main apolipoprotein of CMs.

During translation, the nascent apoB peptide interacts with the ER (6, 7). Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) transfers lipids to a growing apoB polypeptide to form primordial lipoproteins (pre-VLDLs or pre-CMs) (8, 9) that are approximately the same size as plasma HDLs. In the absence of MTP or insufficient amounts of lipids, apoB is ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome (10). In the second step, primordial lipoproteins are enlarged into VLDLs or CMs (6, 11–13). These larger VLDLs and CMs undergo a second quality-control step, post-ER presecretory proteolysis, whereby oxidized, aggregated low density apoB-containing lipoproteins (Blps) are degraded by autophagy and lysosomes (10). Because of their large size, VLDLs and CMs travel through the secretory pathway via specific transport vesicles and are secreted via exocytosis into the circulation (14, 15). In the circulation, CMs and VLDLs acquire exchangeable apolipoproteins and undergo lipolysis by lipases anchored to the endothelial cell surface (16). The hydrolyzed remnant Blps are cleared mainly by the liver via receptor-mediated endocytosis (1, 17).

Because elevated plasma levels of Blps contribute to hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic diseases, reducing their plasma levels is a worldwide public health goal (18–20). Plasma apoB may be elevated due to increased secretion or decreased catabolism of Blps. Much work has been done to elucidate mechanisms in the assembly, secretion, degradation, regulation, uptake, internalization, and trafficking of Blps in order to find ways to lower their plasma concentrations. However, to date it has proven difficult to study these processes in systems that are amenable to high-throughput screening and capture the physiologic complexity of Blp metabolism.

Fluorescently tagged proteins are useful tools for studies and have been invaluable for monitoring intracellular biological processes (21, 22). They are frequently used in live cell imaging and intravital microscopy to investigate physiological processes in real time (23). Fluorescent fusion proteins are also advantageous for high-throughput screens to identify regulatory proteins in various pathways and specific antagonists. In addition, they are easier to handle and dispose of than radioactive molecules that are usually used to study lipoprotein assembly and secretion. Despite the clear value of fluorescently tagged apoB in research and drug discovery, an apoB fluorescent fusion protein has not been previously developed and/or published to our knowledge. This is most likely the result of technical challenges faced in cloning the very large coding sequence of apoB, which we were able to overcome with modern cloning and gene synthesis techniques. Here, we report three plasmids expressing fluorescent apoB fusion proteins. Utilizing these constructs, we were able to visualize intracellular apoB in mammalian cells. These apoB fusion proteins were secreted in an MTP-dependent fashion as full-length lipoprotein particles. Finally, the apoB48-mCherry construct was transiently expressed in zebrafish larvae to evaluate whether this approach was also effective in vivo. Fluorescent apoB fusion proteins could be detected and visualized in living cells. Taken together, these results indicate that the C-terminal fusion of fluorescent proteins to apoB does not interfere with the assembly, secretion, or uptake of Blps, and these fusion proteins can be used to study both the intracellular and intraorganism transport of Blps.

METHODS

Plasmids

The untagged apoB48 expression plasmid was described previously (24). The apoB48-GFP fusion construct was custom-synthesized by Cyagen Corp. (Fig. 1A). The 5′-untranslated region (UTR) and coding region of human apoB48 (7,403 bp; accession number NM_000384) was subcloned into the pRP.Des2d vector via gateway cloning. apoB48A-GFP was expressed under a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. Enhanced GFP (27 kDa; excitation/emission maximum: 488/509 nM) was inserted at the C terminus of the protein after a linker sequence (15 bp; TACAAA TTGCATTAG) and before the SV40 3′-UTR and polyA signal.

Fig. 1.

Plasmids expressing different apoB fusion proteins. A: apoB48-GFP was custom-designed and constructed by Cyagen Corp. The 5′-UTR and N-terminal 48% of apoB were subcloned into the pRP.ExTri-CMV vector, which was expressed under a CMV promoter. eGFP was added after a linker sequence at the C terminus of the protein. B: apoB48-mCherry was subcloned into the pDONOR vector and then recombined into the pDEST vector using a lambda-based recombination reaction. mCherry was inserted at its C terminus. Expression was driven by the hsp70 promoter. C: apoB100-GFP synthesized by Origene. The open reading frame of full-length apoB was expressed under the CMV promoter. TurboGFP was added to the C terminus of the protein.

Multisite gateway cloning was used to construct the apoB48-mCherry vector (25). The coding region of human apoB48 was amplified by PCR from apoB100 using primers that also inserted attB sites for gateway cloning. It was subcloned into the pDONOR vector and then recombined into the pDEST vector using a lambda-based recombination reaction. It was expressed under the control of the inducible heat-shock protein 70 (hsp70) promoter. A fluorescent tag, mCherry (excitation/emission maximum: 587/610 nM), was cloned onto the C terminus of the protein (Fig. 1B).

The apoB100-GFP vector (Fig. 1C) was made by Origene. The open reading frame of full-length human apoB (NM_000384) was subcloned into a PCMV6-AC-GFP plasmid via restriction digest with sgf1 and mlu1. ApoB100 was expressed under the CMV promoter. At the C terminus of the protein, a linker sequence (21 bp) followed by TurboGFP (Pontellina plumata; 26 kDa; excitation/emission maximum: 482/502 nm) was inserted before the human growth hormone polyA signal. Each of these plasmids has been deposited in AddGene. A control GFP plasmid (pmaxGFP) was from Lonza.

Expression and visualization of apoB chimeras in Cos-7 cells

Cos-7 cells were plated on coverslips (70,000 cells/well of a 12-well plate) and transfected with 2 µg plasmids expressing apoB48-GFP or apoB100-GFP using Turbofect (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 2 µl Turbofect per 1 µg DNA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and rinsed, and the nucleus was stained with DAPI. Coverslips were mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting media (Vector Laboratories) to prevent photobleaching. Immunofluorescence was detected with an Olympus confocal microscope.

For the expression of apoB48-mCherry, cells were transfected as described above. After 24 h, cells were incubated at 43°C for 30 min (heat shock). Eight hours later, the same cells were again subjected to one more heat shock for 30 min. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were fixed and visualized as described above.

For colocalization of apoB with calnexin, fixed cells were blocked with PBS supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton, and 1% horse serum for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with anti-calnexin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:200 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells expressing GFP-tagged proteins were then probed with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen; 1:250 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells expressing apoB48-mCherry were probed with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen; 1:250 dilution). Coverslips were mounted and visualized as described above.

apoB and MTP colocalization

First, Cos-7 cells were plated in 100 mm diameter plates (1,000,000 cells per plate) and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, and l-glutamine. After 18 h, they were transfected with 6 μg plasmids expressing apoB48-GFP using Turbofect (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 2 µl Turbofect per 1 µg DNA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One day later, the cells were trypsinized and plated on coverslips (70,000 cells/well of a 12-well plate) and reverse-transfected with 1.5 μg plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged MTP (26–29). After 48 h, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed, and blocked with PBS supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton, and 1% horse serum for 1 h at room temperature. They were then incubated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:200 dilution in TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then probed with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen; 1:250 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (1:5000 dilution in PBS) for 10 min. Cells were rinsed in PBS and mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting media to prevent photobleaching. Immunofluorescence was detected with an Olympus confocal microscope. Eight adjacent fields were captured. The GFP tag on the apoB48-GFP can be visualized without probing for apoB.

Measurement of cellular and secreted apoB

Cos-7 cells are most commonly used to study the initiation step of lipoprotein assembly. Although these cells do not naturally secrete lipoproteins, the coexpression of apoB with MTP decreases posttranslational degradation of apoB and is sufficient for lipoprotein assembly and secretion (26–32). Cos-7 cells were plated (250,000 cells/well) in 6-well plates and transfected with 3 µg plasmids expressing different apoB constructs with Turbofect as described above. To induce apoB expression, cells expressing apoB48-mCherry were heat-shocked twice as described above. After 36 h, cells expressing different constructs were incubated with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 0.4 mM oleic acid complexed with 1.5% BSA for 16 h. apoB was measured in the media via ELISA (24, 33).

Similar experiments were performed in a rat hepatoma cell line, McA-RH7777. McA-RH7777 cells express endogenous rat MTP and apoB and naturally assemble apoB-containing lipoproteins and have been extensively used to study lipoprotein assembly (34–36). Plasmids expressing the chimeric apoB constructs were transfected in McA-RH7777 cells. Forty-eight hours later, media were collected from the cells after an overnight incubation with DMEM containing 20% FBS and 0.4 mM oleic acid complexed to 1.5% BSA. ELISA was used to measure apoB in the media (24, 33).

In order to measure intracellular human apoB, cells were scraped in PBS. A small amount of cell lysate was used to measure total protein with the Coomassie Plus Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The rest of the cell lysate was centrifuged at 100 g. The pellet was resuspended in cell extract buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), rotated for 1 h at 4°C, and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was used to measure intracellular apoB by ELISA.

Immunoprecipitation

ApoB plasmid constructs were transfected in Cos-7 cells as described above. After 36 h, cells were cultured overnight in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 0.4 mM oleic acid/1.5% BSA complexes. Media from three wells were combined and incubated with 2 µl anti-apoB antibody (Academy Biomedical Co., Inc.) at 4°C for 1 h. Next, 40 µl protein A/G PLUS agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added and rotated for 3 h at 4°C. The beads were rinsed three times with PBST. ApoB was eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Immunoprecipitants were run on a 6% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked in TBST with 5% milk for 1 h and probed with a monoclonal antibody against apoB, 1D1 (University of Ottawa Heart Institute), overnight at 4°C. Next, membranes were incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 633 (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were visualized with a phosphorimager (Storm 860; Molecular Diagnostics). For immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of GFP, anti-GFP antibodies from Protein Tech were used.

Density gradient ultracentrifugation of lipoproteins

apoB plasmid constructs were transfected in Cos-7 cells. Cells expressing all three constructs were incubated overnight with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 0.4 mM oleic acid complexed with 1.5% BSA. Four wells were combined for density gradient ultracentrifugation. Four milliliters of media were brought up to 1.34 g/ml with solid potassium bromide (KBr). Next, the media were overlaid with differing-density KBr solutions in the following order: 2 ml 1.21 g/ml, 2 ml 1.15 g/ml, 2 ml 1.063 g/ml, 1 ml 1.019 g/ml, and 1 ml 1.006 g/ml. Media from McA-RH7777 were adjusted to 1.34 g/ml with solid KBr and then overlaid with 1 ml 1.21 g/ml, 1 ml 1.15 g/ml, 2 ml 1.063, 2 ml 1.019 g/ml, and 2 ml 1.006 g/ml. Media were centrifuged overnight (SW41 rotor; 40,000 rpm, 197,568 g, 17 h, 15°C), and 1 ml fractions were collected from the top. ApoB content was measured via ELISA, and the density was measured with a refractometer in each fraction.

Expression of apoB48-mCherry in zebrafish

apoB48-mCherry (100 pg) or mCherry-Rab5c (100 pg) (37) was injected into zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage along with mRNA encoding Tol2 transposase (100 pg) in a volume of 2 nl. Tg(actin2:eGFP-Rab7) transgenic fish were used to facilitate the visualization of the cellular ultrastructure as well as the subcellular localization of late-endosomal compartments (37, 38). Injected larvae were heat-shocked at 37°C for 1 h at 5 dpf, and images were taken on 6 dpf live zebrafish with an inverted Leica DMI6000 confocal microscope (SP5) 17–20 h after heat shock. Live animals were mounted for imaging as previously described (39). A total of 13 larvae from 3 independent clutches were imaged after being injected with the apoB48 plasmid, and 11 larvae were imaged following Rab5-mCherry injections. Additionally, wild-type larvae were coinjected with apoB48-mCherry and Rab7-GFP plasmids along with Tol2 transposase mRNA. Injected larvae were heat-shocked at 37°C for 1 h at 5 dpf and imaged 4 h after heat shock. A total of six larvae from three independent clutches were imaged following coinjection with the apoB48-mCherry and Rab7-GFP plasmids.

Statistical analyses

One-way ANOVA was used to compare both apoB secretion and intracellular apoB expression in cells that expressed MTP and cells that did not express MTP. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Subcellular localization of apoB fusion proteins to the ER and colocalization with MTP

Plasmids encoding apoB fusion proteins (Fig. 1) were transfected into Cos-7 cells, and the fluorescently labeled apoB fusion proteins were visualized using confocal microscopy (Fig. 2A, B). Both apoB48-GFP (green) and apoB48-mCherry (red) showed diffuse perinuclear labeling that colocalized with the ER marker calnexin. Colocalization of apoB48-GFP and apoB48-mCherry with calnexin (yellow) indicates that they are present in the ER, the site of Blp assembly (Fig. 2A, B). MTP, critical for Blp assembly, is also localized mainly to the ER. In order to visualize whether MTP colocalized with apoB, we coexpressed MTP-FLAG and apoB48-GFP in Cos-7 cells and performed immunohistochemistry. MTP-FLAG colocalized with apoB-GFP, indicating that the two proteins are located in the same subcellular compartment (Fig. 2C). Thus, apoB fusion proteins are expressed in the ER in close proximity to MTP.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescent apoB fusion proteins are located in the endoplasmic reticulum and colocalize with calnexin and MTP. Cos-7 cells were plated on coverslips and transfected with plasmids expressing the various apoB constructs. A: After 48 h, cells expressing apoB48-GFP (green) were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (calnexin, red). B: Cells expressing apoB48-mCherry were incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (calnexin, green). C: Cos-7 cells were first transfected with plasmids expressing apoB48-GFP followed by plasmids expressing MTP-FLAG. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). Cells were visualized with an Olympus confocal microscope. Images were merged to determine colocalization (yellow). The experiment was performed in duplicate, and eight adjacent fields were captured per slide. Scale bars: 10 µm.

Quantification of intracellular apoB fusion proteins

To quantify the intracellular amounts of apoB in Cos-7 cells, we transfected the tagged apoB constructs in Cos-7 cells that stably expressed MTP (+MTP-FLAG) and compared the levels to cells not expressing MTP (−MTP-FLAG). In addition, these Cos-7 cells were also transfected with a previously characterized untagged apoB48 construct that acted as a positive control. Untagged apoB48 was the most highly expressed in both Cos-7 cells expressing MTP and not expressing MTP (Fig. 3A). ApoB48-GFP and apoB48-mCherry were present at 67% and 53%, respectively, of the untagged apoB48. ApoB100-GFP was also detected intracellularly, albeit at lower levels (∼30% of untagged apoB48) (Fig. 3A). There were no significant differences in intracellular apoB between cells expressing MTP-FLAG and cells not expressing MTP-FLAG (Fig. 3A). Thus, these studies indicate that all four apoB peptides were expressed in these cells, independent of the presence or absence of MTP. This is not surprising, as apoB is expressed in the absence of MTP and MTP is required only for its assembly into lipoprotein and secretion.

Fig. 3.

apoB fusion proteins are secreted as lipoproteins from Cos-7 cells. A, B: apoB plasmids were transfected into two different Cos-7 cells. +MTP-FLAG are cells that were stably expressing MTP-FLAG, and −MTP-FLAG are cells that do not express MTP. After 36 h, cells were incubated with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 0.4 mM oleic acid complexed with BSA. Media were collected after an overnight incubation. ApoB was measured in the cell lysates (A) and media (B). Data are representative of two experiments performed in triplicate. A Student’s t-test was performed for each condition between +MTP-FLAG and −MTP-FLAG (mean ± SD; n = 3; *P < 0.05). The expression of apoB fusion proteins was similar in Cos-7 cells whether they were expressing MTP or not (A). These fusion proteins were secreted into media from cells that were also expressing MTP (B). C: Cos-7 cells stably transfected with MTP-FLAG were transfected with different plasmids expressing the indicated apoB peptides. ApoB was immunoprecipitated from the media. Immunoprecipitates were run on a 6% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed for apoB. Bands were visualized in a phosphorimager. Images are representative of two experiments performed in duplicate. D: Cos-7 cells were transfected with either control-GFP (2.5 µg) and hMTP (2.5 µg) or apoB48-GFP (2.5 µg) and hMTP (2.5 µg) plasmids. After 36 h, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-GFP antibodies. A different set of cells, after 36 h of transfection, was washed and replenished with fresh media. After overnight incubation, the media were collected for immunoprecipitation. The immunoprecipitates were run on 3% to 8% Tris acetate gradient gels and immunoblotted using anti-GFP antibodies. Data are representative of two independent experiments. E, F: Cos-7 cells expressing either control-GFP or apoB48-GFP were visualized using a fluorescent microscope (E). In a separate experiment, transfected cells were probed for calnexin (red). The images were taken at 100× magnification with a Nikon Eclipse confocal microscope (F). Control-GFP was in the cytosol and did not colocalize with calnexin. In contrast, apoB48-GFP colocalized with calnexin.

ApoB fusion proteins are secreted from cells

In order to ensure that the fluorescent tag did not interfere with the secretion of apoB, we measured the amount of apoB secreted into the cell culture media. Cos-7 cells can secrete apoB only if both MTP and apoB are coexpressed (40). Media from Cos-7 cells not expressing MTP had very low amounts of apoB (0.5% to 5.5% of secreted apoB compared with cells expressing MTP) (Fig. 3B). Thus, apoB48 and apoB100 are not secreted to any appreciable amount in the absence of MTP.

In cells expressing MTP, untagged apoB48 was the most highly secreted peptide. Cells expressing untagged apoB48 secreted about two times more apoB than cells expressing apoB48-GFP or apoB48-mCherry (Fig. 3B). Cells expressing apoB100-GFP secreted apoB at much lower levels (∼12% of untagged apoB48) (Fig. 3B), probably due to low transfection efficiency of the larger plasmid. However, this level of secretion was significantly higher than in cells not expressing MTP. Therefore, the addition of the fluorescent tag did not abolish secretion of apoB fusion proteins, and their secretion was dependent on MTP.

To validate that the secreted peptides retained the fluorescent tag, media from cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-apoB antibody and subjected to Western blotting. Probing the blot for apoB revealed slightly higher molecular weight bands for apoB48-GFP and apoB48-mCherry relative to untagged apoB48, consistent with the secretion of full-length apoB fusion proteins (Fig. 3C). This was further studied by transfecting cells with apoB48-GFP and MTP plasmids (Fig. 3D). For control, cells were transfected with plasmids expressing control GFP and MTP. Cells and media were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted using anti-GFP antibodies. Cells and media from cells transfected with apoB48-GFP showed a prominent band with a molecular weight higher than 250 kDa. This band was absent in cells transfected with GFP-only plasmids. These studies indicate that GFP runs as a high molecular weight band only when expressed as an apoB48 fusion protein. We further studied the subcellular localization of GFP in cells expressing GFP or apoB48-GFP. As expected, the transfection efficiency and expression of GFP were much higher than those of apoB48-GFP (Fig. 3E). In cells expressing GFP, GFP was mainly in the cytosol and did not colocalize with calnexin (Fig. 3F). In contrast, apoB48-GFP was not in cytosol but was in the ER colocalized with calnexin. These studies suggest that GFP becomes an ER protein when expressed as apoB48 fusion proteins. Although the apoB100-GFP levels could be measured by ELISA (Fig. 3B), these levels could not be detected by Western blot analysis or immunofluorescence (not shown).

ApoB fusion proteins are secreted as lipoproteins in Cos-7 cells

Next, we determined whether fluorescently tagged apoB fusion proteins were secreted as buoyant Blps. ApoB constructs were transfected in Cos-7 cells stably expressing MTP. Because Cos-7 cells do not endogenously make Blps, Cos-7 cells that express both MTP and apoB secrete HDL-sized lipoproteins, even after oleic acid supplementation (26, 28–30). Consistent with previous studies (26, 28–30), untagged apoB48 was secreted as particles with a density similar to HDL in the range of 1.12–1.19 g/ml (Fig. 4A). Compared with apoB48, apoB48-GFP was secreted as a more homogenous population of Blps with a flotation density of 1.10–1.19 g/ml (Fig. 4B). Like apoB48-GFP, the bulk of apoB48-mCherry was secreted as lipoproteins with a density of 1.11–1.20 g/ml with a peak at 1.12 g/ml (Fig. 4C). ApoB100-GFP had a lower flotation density of 1.08–1.15 g/ml (Fig. 4D). This is consistent with the observation that the longer full-length apoB100 can recruit more lipids than apoB48 (30, 39). A small amount of all four apoB peptides could also be detected in the lipid-free protein fraction (fraction 12), which may be degradation products of apoB recognized by the monoclonal antibody 1D1 used for ELISA. These studies show that C-terminally tagged apoB fusion proteins are lipidated similarly to untagged proteins, are secreted as buoyant Blps particles, and that the fluorescent tag does not interfere with the assembly and secretion of these Blps.

Fig. 4.

ApoB fusion proteins are secreted as lipoproteins. Cos-7 cells stably expressing MTP were transfected with different apoB fusion proteins. A–D: Media from four wells for each plasmid were combined, adjusted to 1.3 g/ml with KBr, and overlaid with solutions with varying densities to create a density gradient and subjected to density gradient ultrancentrifugation in a SW-41 rotor (40,000 rpm, 197,568 g, 14°C, 16 h), and 1 ml fractions were collected. ApoB was measured via ELISA in each fraction of the media of cells expressing apoB48 (A), apoB48-GFP (B), apoB48-mCherry (C), or apoB100-GFP (D). The density in each fraction was measured with a refractometer. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

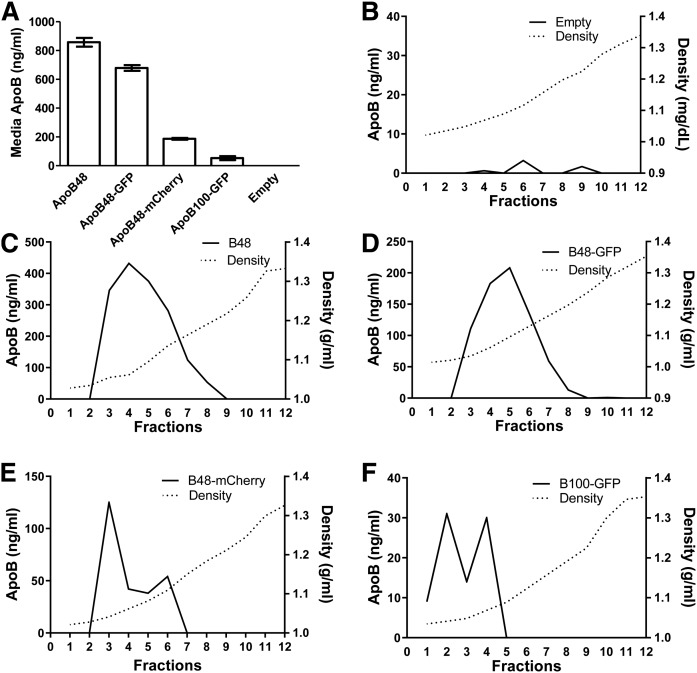

Characterization of apoB fusion lipoproteins secreted by McA-RH7777 cells

To study the secretion of apoB fusion proteins in a system that naturally produces Blps, we expressed these constructs in a rat hepatoma cell line, McA-RH7777. The monoclonal antibody used for human apoB ELISA, 1D1, does not detect rat apoB. Hence, cells transfected with an empty plasmid have no detectable apoB in the media (Fig. 5A, B). apoB48 and apoB48-GFP were efficiently secreted by McA-RH7777 cells (Fig. 5A). The amounts of both apoB48 and apoB48-GFP secreted by McA-RH7777 cells were higher than those secreted by Cos-7 cells (compare Fig. 5A with Fig. 3B). The amounts of apoB48-mCherry and apoB100-GFP were lower than apoB48-GFP (Fig. 5A) and were comparable to those secreted by Cos-7 cells (compare Fig. 5A with Fig. 3B).

Fig. 5.

ApoB fusion proteins are secreted as LDL-sized particles when expressed in McA-RH7777 cells. Rat hepatoma McA-RH7777 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing various apoB fusion proteins. After 36 h, cells were incubated with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 0.4 mM oleic acid complexed with BSA. The media were collected after an overnight incubation. A: ApoB was measured in the media via ELISA (mean ± SD; n = 4; one-way ANOVA). B–F: Media from four wells were combined, adjusted to 1.3 g/ml with KBr, and overlaid with KBr solutions with varying densities. Media were subjected to overnight ultracentrifugation in an SW41 rotor (40,000 rpm, 197,568 g, 15°C, 16 h), and 1 ml fractions were collected from the top. ApoB in each fraction of the media of cells expressing no human apoB (B), apoB48 (C), apoB48-GFP (D), apoB48-mCherry (E), or apoB100-GFP (F) was measured via ELISA. In addition, the density of each fraction was measured with a refractometer (dotted lines). Data are representative of two experiments.

Ultracentrifugation of the media from McA-RH7777 cells expressing the various apoB fusion proteins showed that secreted proteins floated at densities similar to those of plasma LDL and HDL (Fig. 5C–F). No apoB was detected in the bottom fractions 9–12 (1.22–1.33 g/ml). Consistent with results from previous studies (26, 30), the untagged apoB48 was secreted with a peak density at 1.062 g/ml (Fig. 5C). About 20% of the untagged apoB48 was secreted with a density of 1.05 g/ml (fractions 2 and 3). There were no Blps secreted in the VLDL fraction (fraction 1). ApoB48-GFP was detected (1.03–1.20 g/ml) in both the HDL and LDL fractions with a peak density at 1.1 g/ml. Approximately 40% (fractions 3 and 4) of apoB48-GFP was secreted with a density similar to LDL (1.03–1.061 g/ml) particles (Fig. 5D). Like the untagged apoB48, there was no apoB48-GFP in the VLDL or lipid-free protein fractions. Unlike apoB48-GFP and untagged apoB48, a majority (65%) of apoB48-mCherry was found in the LDL buoyancy fractions (1.04–1.06 g/ml) (Fig. 5E) with a peak at 1.04 g/ml. Longer apoB peptides form more triglyceride-rich and less-dense Blps with a greater circumference (39). Consistent with these published observations, almost all of the apoB100-GFP was found in the LDL fractions (1.03–1.06 g/ml) (Fig. 5F). Because some apoB100-GFP was found in fraction 1 (1.03 g/ml), it is possible that apoB100-GFP formed VLDL-sized particles. Collectively, both studies in Cos-7 and McA-RH7777 cells suggest that apoB fusion proteins can form Blps with densities similar to untagged apoB.

Secretion and endocytosis of apoB48-mCherry in larval zebrafish

Encouraged by the findings from cultured cells, we went on to evaluate whether these fluorescent apoB fusion proteins would enable monitoring of Blps in vivo using larval zebrafish. Tg(actin2:eGFP-Rab7) transgenic larvae were coinjected with 100 pg apoB48-mCherry or mCherry-Rab5c plasmids and 100 pg mRNA encoding Tol2 transposase, which promotes random integration of the construct into the genome of only a subset of cells, while the majority of cells remain wild-type (nontransgenic). After 17–20 h, a bright mCherry signal was detectable in a small subset of cells injected with the Rab5c plasmid, indicating that integration of the transgene is rare and that this control protein (an early endosomal marker) is not trafficked to neighboring cells (Fig. 6A). By contrast, each larva injected with the apoB48 construct had mCherry-rich puncta detectable throughout the entire liver (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Expression of human apoB48-mCherry in zebrafish. A: Low-magnification confocal images of Rab5-mCherry clones in the zebrafish liver (n = 11). B: Low-magnification confocal images of apoB48-mCherry in the zebrafish liver. The fluorophore is detectable ubiquitously throughout the liver (n = 13). C: High-magnification confocal images of Rab5-mCherry clones in the zebrafish liver, including the stable transgenic Rab7-EGFP marker of cellular ultrastructure and early endosomes. Clones lacking Rab5-mCherry are clearly visible (dashed white lines), confirming findings from the low-magnification images that suggest that the construct integrates into only a subset of liver cells. D: High-magnification confocal images of apoB48-mCherry in the zebrafish liver, demonstrating not only ubiquitous dispersion of this protein product throughout the liver but also partial colocalization with late endosomes (white arrowheads). E: Double mosaic images 4 h after heat shock displays the Rab7 signal restricted to transgenic clones, whereas the apoB48-mCherry signal is detectable throughout the liver (n = 6).

Next, we compared the expression patterns of Rab5-mCherry and apoB48-mCherry in transgenic larvae stably expressing Rab7-GFP. Rab7-GFP is an in vivo marker of endosomes and cellular ultrastructure. Consistent with our findings in wild-type larvae, Rab5-mCherry was only detectable in a subset of liver cells, indicating that the transgene integrated into a small number of cells (Fig. 6C, white outlines). By contrast, apoB48-mCherry was detectable throughout the liver and partially colocalized with the Rab7-GFP-labeled endosomes (Fig. 6D, white arrowheads).

To investigate the kinetics of protein expression further, wild-type larvae were coinjected with plasmids encoding both apoB48-mCherry and Rab7-GFP and imaged 4 h after heat shock. Rab7-GFP expression was restricted to few transgenic clones (Fig. 6E). In contrast, even at this early time point, apoB48-mCherry was present throughout the liver (Fig. 6E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the apoB48-mCherry transgene was expressed in larval zebrafish.

DISCUSSION

This study describes the successful construction of several plasmids that express fluorescent apoB fusion proteins: apoB48-GFP, apoB100-GFP, and apoB48-mCherry. Importantly, these fluorescent apoB proteins exhibit several central and important aspects of endogenous apoB homeostasis in that they i) localize to the ER, ii) require MTP for secretion, and iii) form buoyant lipid-rich Blps. Additionally, apoB48-mCherry was detectable in vivo in larval zebrafish. Hence, the C-terminal addition of a fluorescent protein to apoB does not interfere with lipidation and secretion.

One of the main motivations of a C-terminal tag was to avoid disrupting the ER-targeting signal peptide at the N terminus. Encouragingly, irrespective of the apoB fusion protein studied or culture system used, fluorescent apoB localized properly to the ER. The fusion proteins remained intact in cells and media. We further demonstrated that these proteins were lipidated by both human and rat MTP. Last, secreted fluorescent apoB was present exclusively in the buoyant density fractions of supernatants derived from rat hepatoma cells, indicating that it is lipidated and associated with Blps.

However, several differences were observed between the fluorescent apoB fusions and untagged apoB48. ApoB48-GFP and apoB48-mCherry were expressed at significantly lower levels than untagged apoB48 in Cos-7 cells. This observation could be attributable to the lower transfection efficiency of the larger plasmids. However, when the same experiment was repeated in the rat hepatoma cell line, apoB48-mCherry was detectable at much lower levels than apoB48-GFP, indicating that these different fluorescent proteins may have different effects on lipoprotein biogenesis. Additionally, the density distributions of the resulting particles were somewhat different between apoB48-mCherry and apoB48-GFP, with the GFP-tagged version closely mirroring the native apoB48 and the mCherry fusion producing a higher number of LDL-like particles.

ApoB100-GFP was also secreted from cells in an MTP-dependent fashion as LDL- and HDL-sized particles, as quantified by ELISA. However, due to its low expression, it could not be visualized by immunohistochemistry in the ER or via Western blot after immunoprecipitation, which may limit its utility for trafficking and protein-expression experiments. The relatively low transfection efficiency of all three plasmids could be overcome by generating stably expressing cell lines or animals.

The apoB48-mCherry construct was also evaluated in vivo using the zebrafish larvae. In contrast to the endosomal markers Rab5c and Rab7 that were detectable only in a subset of cells, apoB48-mCherry was detectable throughout the liver. Further, some apoB48-mCherry was colocalized with Rab7 in the endosomal compartment. We interpret this to suggest that apoB48-mCherry was secreted from transfected cells and subsequently endocytosed by neighboring nontransgenic hepatocytes. Additionally, colocalization with Rab7 suggests that trafficking occurs at least partially through the endosomal pathway, as would be expected for native lipoproteins. Alternatively, it is possible that apoB48-mCherry is detectable throughout the liver because it integrates very efficiently into the genome and forms large transgenic clones.

There are several important limitations to this zebrafish model: i) apoB48-mCherry was tagged with the fluorophore; ii) these larvae had an additional apoB gene incorporated into the genome that was encoded by a human cDNA sequence; iii) the transgene expression was driven by a ubiquitous heat-shock promoter (hsp70) that may have caused expression in tissues that do not normally produce lipoproteins; and iv) these larvae were expressing the truncated apoB48 isoform that is usually associated with intestine-derived CMs. Despite these departures from the biology of endogenous zebrafish apoB, this human apoB48 was expressed and could be visualized.

Fluorescently tagged proteins are valuable tools for large-scale screening in both mammalian cells and nonmammalian model systems (21–23). Here, we show that the fusion of different fluorescent proteins at the C terminus of apoB is well tolerated during Blp assembly. Because apoB constructs described in this study can be visualized in mammalian cell lines, they would be valuable for live cell imaging, identifying the subcellular location of apoB, and tracking apoB intracellularly under different conditions. In addition, unlike untagged apoB, these constructs can be used in human or other mammalian cell systems that endogenously express apoB, such as liver and intestinal cells, in order to study intracellular Blps assembly and its transport. They may also be useful for visualizing and investigating apoB in other apoB-expressing tissues that are less widely studied, such as the heart (41), retina (42), or kidney (43). Further, they may be valuable in high-throughput screening for identifying molecules that support or interfere with apoB expression, Blps assembly, and secretion pathways, as well as their uptake.

Each construct also has its own advantages and disadvantages. For example, because apoB48-mCherry is expressed under an inducible promoter, it is possible to heat-shock the cells and visualize the progression of apoB48 through the secretory pathway. The apoB48-GFP plasmid contains the 5′-UTR, which may help to identify translational regulators. One drawback of these proteins is that they are not endogenously expressed. Overexpression of these plasmids may have unintended consequences on other molecular pathways. Further, the apoB48-mCherry and apoB100-GFP plasmids do not contain the 5′-UTR and thus may not fully recapitulate certain aspects of translational regulation. Finally, none of the plasmids contain the 3′-UTR and consequently any cis- or trans-acting regulatory elements will not influence their expression or mRNA degradation. The results described here and an understanding of their caveats provide justification for future efforts to insert the GFP coding sequence into the endogenous apoB gene locus via precise genome editing similar to the LipoGlo system recently developed in zebrafish (44), which may be a more valuable tool for studying these regulatory mechanisms.

Zebrafish recapitulate the major aspects of interorgan lipoprotein homeostasis in an optically clear organism, thus creating the opportunity for in vivo imaging (45, 46). This opportunity may facilitate the study of lipid transport in the blood stream between organs, apoB deposition in plaques and the endothelium, LDL endocytosis in peripheral tissues, endosomal trafficking, and the role of apoB in development. Blps are atherogenic proteins, and their elevated plasma levels have long been a risk factor for atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases (18, 20). Zebrafish are easily genetically manipulated and amenable to small-molecule screening. The availability of fluorescently tagged proteins in this animal model may pave the way for the identification of possible novel drug targets or gene-drug interactions.

In short, we report that adding fluorescent reporter proteins at the C terminus of apoB does not disrupt their ability to form Blps. These constructs can be used to study Blp assembly, secretion, trafficking, and regulation both within cells and in intact organisms. Fluorescent proteins fused to apoB represent a valuable tool for investigating the cell biology of Blps as well as for identifying novel molecules that interfere with lipoprotein biogenesis and transport through high-throughput screening.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Kowalski for help cloning the hsp70:apoB48-mCherry plasmid.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- Blp

- low density apoB-containing lipoprotein

- CM

- chylomicron

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus

- hsp70

- heat-shock protein 70

- KBr

- potassium bromide

- MTP

- microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

- UTR

- untranslated region

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK093399 (S.A.F.), R01 GM63904 (S.A.F.), R01 DK116079 (S.A.F.), F31 HL139338 (J.H.T.), HL-137202-01A1 (M.M.H.), and DK046900-17A1 (M.M.H.) and Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Award BX004113-01A1 (M.M.H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hussain M. M., Kancha R. K., Zhou Z., Luchoomun J., Zu H., and Bakillah A.. 1996. Chylomicron assembly and catabolism: role of apolipoproteins and receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1300: 151–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segrest J. P., Jones M. K., De Loof H., and Dashti N.. 2001. Structure of apolipoprotein B-100 in low density lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 42: 1346–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell-Quint J., Forte T., and Graham P.. 1981. Synthesis of two forms of apolipoprotein B by cultured rat hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 99: 700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S-H., Habib G., Yang C-Y., Gu Z-W., Lee B. R., Weng S-A., Silberman S. R., Cai S. J., Deslypere J. P., Rosseneu M., et al. 1987. Apolipoprotein B-48 is the product of a messenger RNA with an organ-specific in-frame stop codon. Science. 238: 363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell L. M., Wallis S. C., Pease R. J., Edwards W. H., Knott T. J., and Scott J.. 1987. A novel form of tissue-specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein-B48 in intestine. Cell. 50: 831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh M. T., and Hussain M. M.. 2017. Targeting microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and lipoprotein assembly to treat homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 54: 26–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pease R. J., Harrison G. B., and Scott J.. 1991. Cotranslational insertion of apolipoprotein B into the inner leaflet of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature. 353: 448–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussain M. M., Shi J., and Dreizen P.. 2003. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and its role in apolipoprotein B-lipoprotein assembly. J. Lipid Res. 44: 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iqbal J., Walsh M. T., Hammad S. M., Cuchel M., Tarugi P., Hegele R. A., Davidson N. O., Rader D. J., Klein R. L., and Hussain M. M.. 2015. Microsomal triglycerdie transfer protein transfers and determines plasma concentrations of ceramide and sphingomyelin but not glycosylceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 290: 25863–25875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher E. A. 2012. The degradation of apolipoprotein B100: multiple opportunities to regulate VLDL triglyceride production by different proteolytic pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1821: 778–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirwi A., and Hussain M. M.. 2018. Lipid transfer proteins in the assembly of apoB-containing lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 59: 1094–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain M. M. 2000. A proposed model for the assembly of chylomicrons. Atherosclerosis. 148: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cartwright I. J., and Higgins J. A.. 2001. Direct evidence for a two-step assembly of ApoB48-containing lipoproteins in the lumen of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum of rabbit enterocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 48048–48057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiwari S., and Siddiqi S. A.. 2012. Intracellular trafficking and secretion of VLDL. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32: 1079–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansbach C. M., and Siddiqi S. A.. 2010. The biogenesis of chylomicrons. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72: 315–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg I. J. 1996. Lipoprotein lipase and lipolysis: central roles in lipoprotein metabolism and atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 37: 693–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams K. J. 2008. Molecular processes that handle–and mishandle–dietary lipids. J. Clin. Invest. 118: 3247–3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goff D. C. Jr., Lloyd-Jones D. M., Bennett G., Coady S., D’Agostino R. B., Gibbons R., Greenland P., Lackland D. T., Levy D., O’Donnell C. J., et al. 2014. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 129(25 Suppl. 2): S49–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson J. G., and Gidding S. S.. 2014. Curing atherosclerosis should be the next major cardiovascular prevention goal. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63: 2779–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mozaffarian D., Benjamin E. J., Go A. S., Arnett D. K., Blaha M. J., Cushman M., Das S. R., de Ferranti S., Després J. P., Fullerton H. J., et al. 2016. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 133: e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez E. A., Campbell R. E., Lin J. Y., Lin M. Z., Miyawaki A., Palmer A. E., Shu X., Zhang J., and Tsien R. Y.. 2017. The growing and glowing toolbox of fluorescent and photoactive proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 42: 111–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giepmans B. N., Adams S. R., Ellisman M. H., and Tsien R. Y.. 2006. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 312: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chudakov D. M., Lukyanov S., and Lukyanov K. A.. 2005. Fluorescent proteins as a toolkit for in vivo imaging. Trends Biotechnol. 23: 605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain M. M., Zhao Y., Kancha R. K., Blackhart B. D., and Yao Z.. 1995. Characterization of recombinant human apoB-48-containing lipoproteins in rat hepatoma McA-RH7777 cells transfected with apoB48 cDNA: overexpression of apoB-48 decreases synthesis of endogenous apoB-100. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15: 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwan K. M., Fujimoto E., Grabher C., Mangum B. D., Hardy M. E., Campbell D. S., Parant J. M., Yost H. J., Kanki J. P., Chien C. B., et al. 2007. The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev. Dyn. 236: 3088–3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rava P., Ojakian G. K., Shelness G. S., and Hussain M. M.. 2006. Phospholipid transfer activity of microsomal triacylglycerol transfer protein is sufficient for the assembly and secretion of apolipoprotein B lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 11019–11027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khatun I., Walsh M. T., and Hussain M. M.. 2013. Loss of both phospholipid and triglyceride transfer activities of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in abetalipoproteinemia. J. Lipid Res. 54: 1541–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh M. T., Iqbal J., Josekutty J., Soh J., Di L. E., Özaydin E., Gündüz M., Tarugi P., and Hussain M. M.. 2015. Novel abetalipoproteinemia missense mutation highlights the importance of the N-terminal beta-barrel in microsomal triglyceride transfer protein function. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 8: 677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh M. T., Di L. E., Okur I., Tarugi P., and Hussain M. M.. 2016. Structure-function analyses of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein missense mutations in abetalipoproteinemia and hypobetalipoproteinemia subjects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1861: 1623–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S., McLeod R. S., Gordon D. A., and Yao Z.. 1996. The microsomal triglyceride transfer protein facilitates assembly and secretion of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins and decreases cotranslational degradation of apolipoprotein B in transfected COS-7 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 14124–14133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon D. A., Jamil H., Sharp D., Mullaney D., Yao Z., Gregg R. E., and Wetterau J.. 1994. Secretion of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins from HeLa cells is dependent on expression of the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and is regulated by lipid availability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91: 7628–7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rava P., and Hussain M. M.. 2007. Acquisition of triacylglycerol transfer activity by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein during evolution. Biochemistry. 46: 12263–12274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakillah A., Zhou Z., Luchoomun J., and Hussain M. M.. 1997. Measurement of apolipoprotein B in various cell lines: correlation between intracellular levels and rates of secretion. Lipids. 32: 1113–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blackhart B. D., Yao Z., and McCarthy B. J.. 1990. An expression system for human apolipoprotein B100 in a rat hepatoma cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 8358–8360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borén J., Rustaeus S., and Olofsson S. O.. 1994. Studies on the assembly of apolipoprotein B-100- and B-48-containing very low density lipoproteins in McA-RH7777 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 25879–25888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao Z., and McLeod R. S.. 1994. Synthesis and secretion of hepatic apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1212: 152–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otis J. P., Shen M. C., Caldwell B. A., Reyes Gaido O. E., and Farber S. A.. 2019. Dietary cholesterol and apolipoprotein A-I are trafficked in endosomes and lysosomes in the live zebrafish intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 316: G350–G365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark B. S., Winter M., Cohen A. R., and Link B. A.. 2011. Generation of Rab-based transgenic lines for in vivo studies of endosome biology in zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 240: 2452–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spring D. J., Chen-Liu L. W., Chatterton J. E., Elovson J., and Schumaker V. N.. 1992. Lipoprotein assembly: apolipoprotein B size determines lipoprotein core circumference. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 14839–14845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel S. B., and Grundy S. M.. 1995. Heterologous expression of apolipoprotein B carboxyl-terminal truncates: a model for the study of lipoprotein biogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 36: 2090–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen L. B., Veniant M., Boren J., Raabe M., Wong J. S., Tam C., Flynn L., Vanni-Reyes T., Gunn M. D., Goldberg I. J., et al. 1998. Genes for apolipoprotein B and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein are expressed in the heart: evidence that the heart has the capacity to synthesize and secrete lipoproteins. Circulation. 98: 13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C. M., Presley J. B., Zhang X., Dashti N., Chung B. H., Medeiros N. E., Guidry C., and Curcio C. A.. 2005. Retina expresses microsomal triglyceride transfer protein: implications for age-related maculopathy. J. Lipid Res. 46: 628–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krzystanek M., Pedersen T. X., Bartels E. D., Kjaehr J., Straarup E. M., and Nielsen L. B.. 2010. Expression of apolipoprotein B in the kidney attenuates renal lipid accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 10583–10590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thierer J. H., Ekker S. C., and Farber S. A.. 2019. The LipoGlo reporter system for sensitive and specific monitoring of atherogenic lipoproteins. Nat. Commun. 10: 3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson J. L., Carten J. D., and Farber S. A.. 2011. Zebrafish lipid metabolism: from mediating early patterning to the metabolism of dietary fat and cholesterol. Methods Cell Biol. 101: 111–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carten J. D., and Farber S. A.. 2009. A new model system swims into focus: using the zebrafish to visualize intestinal metabolism in vivo. Clin. Lipidol. 4: 501–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]