Arabidopsis nodulin homeobox protein AtNDX interacts with the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) core components AtRING1A and AtRING1B and negatively regulates ABI4 expression during ABA signaling.

Abstract

The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) and the Polycomb group proteins have key roles in regulating plant growth and development; however, their interplay and underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Here, we identified an Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) nodulin homeobox (AtNDX) protein as a negative regulator in the ABA signaling pathway. AtNDX mutants are hypersensitive to ABA, as measured by inhibition of seed germination and root growth, and the expression of AtNDX is downregulated by ABA. AtNDX interacts with the Polycomb Repressive Complex1 (PRC1) core components AtRING1A and AtRING1B in vitro and in vivo, and together, they negatively regulate the expression levels of some ABA-responsive genes. We identified ABA-INSENSITIVE (ABI4) as a direct target of AtNDX. AtNDX directly binds the downstream region of ABI4 and deleting this region increases the ABA sensitivity of primary root growth. Furthermore, ABI4 mutations rescue the ABA-hypersensitive phenotypes of ndx mutants and ABI4-overexpressing plants are hypersensitive to ABA in primary root growth. Thus, our work reveals the critical functions of AtNDX and PRC1 in some ABA-mediated processes and their regulation of ABI4.

INTRODUCTION

The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) regulates a variety of developmental processes including seed dormancy, seed germination, seedling growth, flowering, and plant senescence (Cutler et al., 2010; Zhu, 2016; Nonogaki, 2019). ABA also plays crucial and generally protective roles in various abiotic stress responses including drought, high salt, and low temperature (Cutler et al., 2010; Zhu, 2016; Qi et al., 2018). In the ABA signaling pathway, after perceiving ABA, ABA receptors PYR/PYLs/RCARs interact with and inhibit the negative regulators of the clade A-type protein phosphatases 2C (PP2Cs), which releases the inhibitory effect of these PP2Cs on downstream protein kinases such as SUCROSE NONFERMENTING1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASES2.2/2.3/2.6 (SnRK2.2/2.3/2.6), OPEN STOMATA1, GUARD CELL HYDROGEN PEROXIDE-RESISTANT1 (GHR1), and calcium-dependent protein kinases (Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Cutler et al., 2010; Hua et al., 2012; Zhu, 2016; Qi et al., 2018). Some protein kinases such as SnRKs then phosphorylate and activate downstream targets such as the SLOW ANION CHANNEL-ASSOCIATED1 (SLAC1), which regulates stomatal movement, or transcription factors such as the basic leucine zipper-family proteins ABRE binding factors (ABFs)/AREBs (including ABF1, ABF2/AREB1, ABF3 and ABF4/AREB2; Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000) and ABA INSENSITIVE5 (ABI5; Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000), which regulate the expression of ABA-responsive genes.

In addition to basic leucine zipper transcription factors, many other transcription factors such as MYB, MYC, NAC (NAM, ATAF1/2 and CUC2), the Trp-Arg-Lys-Tyr (WRKY), ZINC-FINGER HOMEODOMAIN (ZHD), NUCLEAR FACTOR-Y (NFY), and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 (ARF2) are involved in the ABA signaling pathway (Ren et al., 2010; Fujita et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Rushton et al., 2012; Singh and Laxmi, 2015; Promchuea et al., 2017). Early studies of ABI mutants in seed germination identified several genes such as ABI1, ABI2, ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5. The genes ABI1 and ABI2, which encode PP2Cs, are key negative regulators in the early ABA signaling pathway. The gene ABI3 encodes a transcription factor with a B3 domain that shares high sequence similarity with maize (Zea mays) Viviparous1 (Giraudat et al., 1992). The gene ABI4 encodes an APETALA2-type transcription factor (Finkelstein et al., 1998), which can bind to target genes by recognizing CE1-like cis-elements (CACCG and CCAC motif) and act as either an activator or a repressor depending on the context (Kerchev et al., 2011; Shu et al., 2013; Wind et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2017). ABI4 expression is hormone-regulated, and its protein stability is affected by ABA and gibberellic acid in opposite ways (Shkolnik-Inbar and Bar-Zvi, 2010; Shu et al., 2016). Several transcription factors have been reported to directly regulate ABI4 expression, such as ABI4 itself and WRKY8, which positively regulate ABI4 expression (Bossi et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2013), and Related to ABI3/VP1 (Feng et al., 2014) and BASIC PENTACYSTEINE (BPC) family proteins, which negatively regulate ABI4 (Mu et al., 2017). BPCs can bind the ABI4 promoter and recruit Polycomb Repressive Complex2 (PRC2), thus repressing ABI4 expression through the histone H3 Lys 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) epigenetic modification (Mu et al., 2017).

Polycomb group proteins (PcGs) are the major epigenetic machinery executing transcriptional repression and developmental regulation in animals and plants (Calonje, 2014; Mozgova and Hennig, 2015; Zhou et al., 2018). The two best-characterized PcG complexes to date are PRC1 and PRC2 (Mozgova and Hennig, 2015). PRC1 deposits histone H2A monoubiquitination (H2Aub) and mediates chromatin compaction of its target genes (Calonje, 2014; Wang and Shen, 2018), and PRC2 catalyzes H3K27me3 (Mozgova and Hennig, 2015). PRC1 components were initially identified in Drosophila melanogaster by genetic approaches. The canonical Drosophila PRC1 consists of Polycomb (Pc), Polyhomeotic, Posterior sex combs (Psc), and dRing1, also known as “Sex combs extra.” They have multiple homologs in mammals, resulting in different possible combinations of PcGs (Shao et al., 1999; Francis et al., 2001). Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) has no Polyhomeotic protein, and the LIKE HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN1 (LHP1), a plant homolog of animal HP1, functions like Pc in recognizing and colocalizing with H3K27me3 genome-wide (Turck et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2007). EARLY BOLTING IN SHORT DAYS and SHORT LIFE interact with EMBRYONIC FLOWER1 (EMF1), a functional equivalent of the Psc C-terminal region, to form a bivalent chromatin reader complex for both H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 that mediate switching between repressed and active chromatin during plant development (Li et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). The most conserved PRC1 components in plants are the RING-finger proteins RING1 and BMI1, corresponding to dRing1 and the N terminus of Psc in Drosophila, respectively (Molitor and Shen, 2013; Merini and Calonje, 2015). In Arabidopsis, two RING1 homologs (AtRING1A and AtRING1B) and three BMI1 homologs (AtBMI1A, AtBMI1B, and AtBMI1C) have been identified based on a unique domain architecture that contains a conserved RING finger domain in the N-terminal region and a ubiquitin-like domain named “Ring-finger And WD40 associated Ubiquitin-Like” in the C-terminal region (Sanchez-Pulido et al., 2008; Xu and Shen, 2008). AtRING1A and AtRING1B interact with themselves, with each other, and with LHP1, EMF1, AtBMI1A, AtBMI1B, and AtBMI1C (Wang and Shen, 2018). The two AtRING1A/B proteins and the three AtBMI1A/B/C proteins have been shown to have E3 ligase activity in vitro and in vivo (Bratzel et al., 2010, 2012).

Target selection by PcGs at various developmental stages is critical for the functions of targets. In Arabidopsis, both cis-element and DNA binding factors are required for recruiting PRC2 (Xiao et al., 2017). Besides the classical hierarchical model in which PRC1 is recruited by the binding of Pc to the H3K27me3 marker deposited by PRC2, numerous factors involved in the recruitment of PRC1 have emerged in mammals (Blackledge et al., 2015). In plants, many proteins interact with PRC1 components EMF1, LHP1, AtRING1A, and AtBMI1A/B/C (Li et al., 2016; Wang and Shen, 2018; Zhu et al., 2019). AtRING1A interacts with ALFIN1-like PHD-domain H3K4me3 binding protein AL6 and directly regulates the expression of ABI3 and DELAY OF GERMINATION1 (DOG1; Molitor et al., 2014), CURLY LEAF (a PRC2 component catalyzing H3K27-methylation; Xu and Shen, 2008), and Chromatin Assembly Factor-1 subunit during DNA replication (Jiang and Berger, 2017). The dissection of different PcG component regulons reflects the important roles of PRC1 in repressing gene expression during seed maturation and vegetative development, and suggests that DNA binding protein may play a crucial role in recruiting PcG to specific targets in plants (Wang and Shen, 2018). Until now, however, no transcription factor has been identified that interacts with AtRING1A/B (Wang and Shen, 2018).

In our previous studies, we used a root-bending assay to study plant response to ABA, and we identified several ABA overly-sensitive (abo) mutants that show hypersensitivity to ABA with respect to inhibition of primary root growth (Liu et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011, 2018; He et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014; Promchuea et al., 2017). The cloned genes include ABO3, which encodes a WRKY transcription factor (Ren et al., 2010); AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 (ARF2; Wang et al., 2011), ABO5, and ABO8, which encode two pentatricopeptide repeat proteins localized in mitochondria (Liu et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2014); ABO6, which encodes a DEXH-box RNA helicase in mitochondria (He et al., 2012); and ENHANCER OF ABA CO-RECEPTOR1 (EAR1), which encodes a novel protein that enhances the activity of PP2Cs (Wang et al., 2018).

Here we characterized two mutant alleles of an Arabidopsis nodulin homeobox homologous gene, AtNDX. The gene NDX was previously isolated from a soybean (Glycine max) nodule-specific expression library (Jørgensen et al., 1999) and represents a small gene family in different plants. The Arabidopsis genome has only one AtNDX gene. AtNDX can bind the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) at the 3′ end of Arabidopsis FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) and control expression of FLC and the antisense transcript COOLAIR (Sun et al., 2013). Our results demonstrate that the expression of AtNDX is downregulated by ABA and that AtNDX directly interacts with AtRING1A and AtRING1B. These proteins coregulate the expression of some common ABA-responsive genes. Further, AtNDX directly binds the downstream region of ABI4 and represses its expression, and mutation of ABI4 could recover the ABA-hypersensitive phenotype of ndx mutants in both seed germination and primary root growth.

RESULTS

AtNDX is a Negative Regulator of ABA-Mediated Inhibition of Seed Germination and Primary Root Growth

A root-bending assay (Yin et al., 2009) was employed to screen for ABO mutants in an ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS)-mutagenized Arabidopsis M2 population, in which we identified two ABO mutant alleles, ndx-5 and ndx-6. Genetic analysis indicated that ndx-5 and ndx-6 are recessive mutations in a single nuclear gene. The mutations ndx-5 and ndx-6 were back-crossed to wild-type Columbia (Col-0) four times before performing the following analyses.

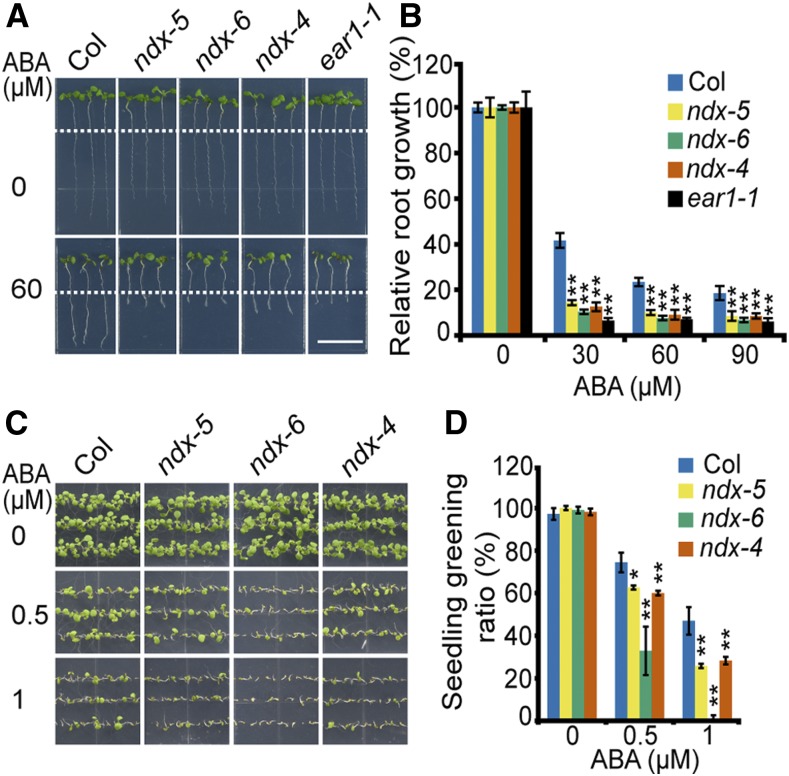

We quantified the ABA-induced inhibition of primary root growth in ndx mutants and the wild type. The primary root growth was measured after 5-d–old seedlings were moved from Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium to MS medium or MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of ABA. The ndx mutants and the wild type showed no difference in primary root growth on MS medium. However, ABA-induced inhibition of root growth was significantly more severe in ndx mutants than in the wild type. Here, we used ear1-1 for comparison of ABA sensitivity (Figures 1A and 1B; Wang et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

ndx Mutants Are Hypersensitive to ABA in Primary Root Growth and Seedling Establishment.

(A) Primary root growth of ndx mutants is hypersensitive to ABA compared with the wild type. Five-d–old seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to an MS medium supplemented with 30 μM, 60 μM, and 90 μM of ABA for 4 d before being photographed. Scale bar = 1 cm. The phenotype in 60 μM of ABA was shown. ear1-1 served as a control.

(B) Statistical analysis of relative root growth with different concentrations of ABA. The root growth of wild type and ndx mutants on MS medium without ABA was set to 100%. Error bars represent ±se of 15 seedlings from three plates in one representative experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(C) Seedling establishment of ndx mutants is hypersensitive to ABA. The seeds were germinated on MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of ABA for 9 d before being photographed.

(D) The seedling greening ratio in (C). Error bars represent ±se of ∼90 seeds from three plates for one experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared with wild type: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

Root growth integrates root cell division, differentiation, and elongation. Therefore, we further determined the meristem zone (MZ) cell number and differentiation zone cell length in ndx-5 and wild type, which reflect the root cell division activity and mature cell size, respectively. Consistent with the primary root growth, both the MZ cell number and differentiation zone cell length were inhibited by ABA to a greater extent in the ndx mutant than in the wild type (Supplemental Figures 1A to 1D). Then we investigated the ABA sensitivity of the seed germination and seedling establishment in ndx mutants and the wild type. With increasing concentrations of ABA, the percentage of seedlings with green cotyledons in ndx mutants was reduced significantly more than those of wild type, while there was no obvious difference between ndx and wild type on MS medium without ABA (Figures 1C and 1D; Supplemental Figures 2A to 2D).

We also detected the expression of ABA response genes, including ABI3 and ABI4, and found the expression levels of these two genes were higher in ndx mutants than the wild type (Supplemental Figure 2E). However, we did not find any difference between the wild type and ndx mutants in a detached leaf water loss assay and stomata number on leaves (Supplemental Figures 2F and 2G), suggesting that NDX is not involved in water loss under drought stress. These results demonstrate that AtNDX is a negative regulator of ABA signaling in seed germination and primary root growth, but not in ABA-promoted stomatal closure.

Isolation of AtNDX by Map-Based Cloning

We identified the mutation in ndx-5 by map-based cloning. AtNDX was delimited to BAC clones T4I9 and F4C21 on chromosome IV (Supplemental Figure 3A). Sequencing of putative genes in this region identified a G1911 to A1911 mutation (counting from the first putative ATG of AT4G03090) in AT4G03090 (previously named “AtNDX,” Supplemental Figure 3A; Mukherjee et al., 2009). We compared the sequences amplified from cDNAs of ndx-5 and the wild type and found that the point mutation affected the acceptor splicing between the seventh intron and the eighth exon and created a new acceptor site upstream of the original one, resulting in an early putative stop codon in the new transcript (Supplemental Figure 3B).

Map-based cloning narrowed down the ndx-6 mutation to the same region as ndx-5. Sequencing of AT4G03090 in ndx-6 revealed a mutation from G569 to A569, which is suspected to change the donor splicing site between the third exon and third intron from GT to AT. Transcript analyses indicated that cDNA from ndx-6 contained an extra third intron that creates an early putative stop codon in the new transcript (Supplemental Figure 3C). We also obtained a AtNDX mutant, enhancer of coolair1-4 (eoc1-4), here renamed “ndx-4,” previously described by Sun et al. (2013). In the ndx-4 mutant, AtNDX is disrupted by a T-DNA insertion (Supplemental Figure 3A; Sun et al., 2013). The mutation ndx-4 showed similar ABA sensitivity to ndx-5 with respect to root growth and seedling establishment (Figure 1).

Immunoblot assays using NDX antibodies indicated that the AtNDX level was significantly reduced in the ndx-4, ndx-5, and ndx-6 mutants compared with the wild type; glutathione S-transferase (GST)-AtNDX-C from Escherichia coli was used as the positive control to evaluate the specificity of NDX antibodies (Supplemental Figure 3E). Given that the phenotypes of ndx-5 are weaker than those of ndx-6 for both flowering time (Supplemental Figure 3F) and ABA sensitivity, ndx-5 is assumed to produce a truncated protein with some residual function.

An 8-kb fragment that includes the wild-type AT4G03090 gene and contains ∼3,000 bp upstream of the first putative ATG to 1,000 bp downstream of the putative TGA stop codon complemented the ABA-sensitive phenotypes of ndx-5 in several independent lines (two independent lines are shown in Supplemental Figures 4A and 4B). In addition, overexpressing AtNDX-MYC under control of a 35S promoter or AtNDX-Flag driven by the native promoter also complemented the ABA-sensitive root phenotype of ndx-5 or ndx-4 (Supplemental Figures 4C to 4F). However, we found that these overexpression lines were not more resistant to ABA than the wild type in terms of primary root growth, suggesting that only a certain amount of AtNDX protein is needed for its full functioning in ABA-mediated primary root growth, or that the protein did not accumulate much, as AtNDX is likely regulated by 26S proteasome pathway as shown below. These results indicate that AT4G03090 is the AtNDX gene.

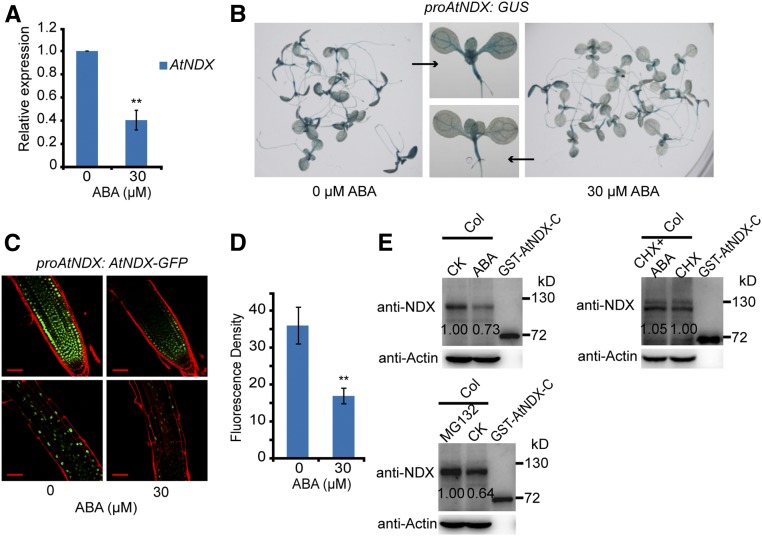

ABA Negatively Regulates the Expression of AtNDX

To elucidate the role of AtNDX in the ABA response, we first examined the effect of ABA treatment on AtNDX expression and AtNDX protein levels. Transcript analysis by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) showed that the expression of AtNDX was significantly repressed by ABA (Figure 2A). We then assayed transgenic plants transformed with the native AtNDX promoter (proAtNDX) driving a GUS reporter gene and found that ABA treatment greatly reduced GUS expression as observed by GUS staining (Figure 2B). We also observed GFP fluorescence in transgenic plants carrying proAtNDX:AtNDX-GFP and found that 30 μM of ABA treatment significantly reduced GFP expression (Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

The Expression of AtNDX Is Inhibited by ABA.

(A) Relative transcript levels of AtNDX in 7-d–old wild-type seedlings treated with 0 μM or 30 μM of ABA for 3 h. Error bars represent ±se of three technical replicates from one experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(B) Representative GUS staining results of proAtNDX:GUS transgenic plants treated with 0 μM or 30 μM of ABA for 12 h.

(C) The fluorescence of AtNDX-GFP is reduced after ABA treatment. Five-d–old seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to an MS medium supplemented with 30 μM of ABA for 12 h before being observed. Scale bar = 50 μm.

(D) Statistical analysis of the fluorescence of MZ in (C). The fluorescence was quantified by the software ImageJ, and error bars represent ±se of 10 seedlings from three plates in one representative experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(E) Immunoblot assays indicate that AtNDX protein level is reduced after ABA treatment. Seven-d–old seedlings were treated by 0 μM (CK) or 50 μM of ABA for 12 h (top left), 100 μM of CHX or 100 μM of CHX +50 μM of ABA for 12 h (top right), 0 μM (CK) or 50 μM of MG132 for 12 h. Then the total proteins were extracted and detected with anti-NDX antibodies. GST-AtNDX-C purified from E. coli was used as a positive control. Actin protein serves as an loading control. The numbers indicate the relative gray value. CK, control check.

To explore whether the AtNDX protein level is affected by ABA, we analyzed the total protein extracts from seedlings with or without ABA treatment. Immunoblotting analysis with anti-NDX antibodies indicated that endogenous AtNDX protein was reduced under ABA treatment. When we used intracellular protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) or CHX plus ABA in treating the seedlings and blocking protein biosynthesis to see the ABA effect on AtNDX protein, the protein reduction caused by ABA was no longer detected (Figure 2E). These results indicate that ABA negatively regulates AtNDX at the transcriptional level, but not at the posttranscriptional level. At the same time, we found that AtNDX was accumulated when seedlings were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. This result suggests that AtNDX is regulated by the 26S proteasome degradation pathway (Figure 2E). Here, GST-AtNDX-C was used as a positive control.

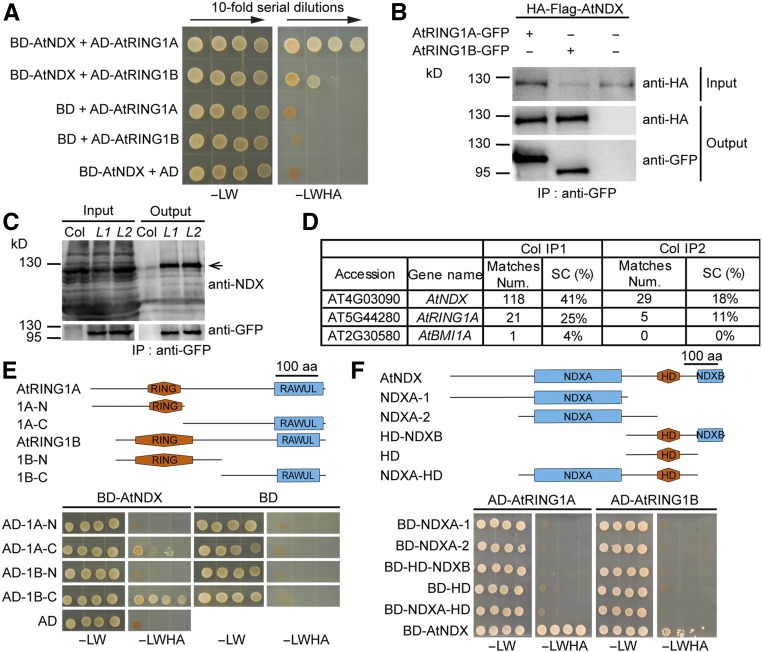

AtNDX Interacts with PRC1 Core Components AtRING1A and AtRING1B

To further clarify the working mechanism of AtNDX, we attempted to identify the proteins interacting with AtNDX through a yeast two-hybrid screening. A normalized Arabidopsis yeast two-hybrid cDNA library was used as the prey, and screened with binding domain fused with AtNDX as the bait. Two clones encoding AtRING1A fragments and one clone encoding an AtRING1B fragment were identified among ∼100 sequenced clones encoding putative interactors. We then verified their interaction with AtNDX using the full-length AtRING1A or AtRING1B in the yeast two-hybrid assay (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

NDX Interacts with PRC1 Core Components AtRING1A and AtRING1B In Vitro and In Vivo.

(A) AtNDX interacts with AtRING1A and AtRING1B in the yeast two-hybrid assay. AD, Gal4 activation domain; BD, Gal4 DNA binding domain; −LW, synthetic dropout medium without Leu and Trp; −LWHA, synthetic dropout medium without Leu, Trp, His, and Ade.

(B) Co-IP assay indicates that AtNDX interacts with AtRING1A and AtRING1B in Arabidopsis protoplasts. The total proteins were isolated from protoplasts co-expressing HA-Flag-AtNDX and AtRING1A-GFP or AtRING1B-GFP proteins. Co-IP was performed with GFP agarose beads and immunoblotting was conducted with anti-HA and anti-GFP antibodies.

(C) Co-IP assay shows that AtNDX interacts with AtRING1A in two independent transgenic lines. The total proteins were isolated from 10-d–old proSuper:AtRING1A-GFP transgenic seedlings (L1, L2) and Co-IP was performed with GFP agarose beads. Immunoblotting was conducted with anti-NDX and anti-GFP antibodies.

(D) Mass spectrometry analysis shows that AtRING1A copurified with AtNDX. The total proteins extracted from 10-d–old wild-type and ndx-5 seedlings were immunoprecipitated with anti-NDX antibodies and the immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. SC, sequence coverage of the protein.

(E) The C terminus of AtRING1A/B interacts with AtNDX in a yeast two-hybrid assay. The structures of AtRING1A/B proteins and the diagrams of truncated proteins were shown on top. aa, amino acids.

(F) The NDXA and NDXB domains of AtNDX are both required for interacting with AtRING1A/B. The structure of AtNDX protein and the diagrams of truncated proteins were shown on top. aa, amino acids.

We next tested whether AtNDX and AtRING1A or AtRING1B interact in vivo using a coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay. Proteins were extracted from protoplasts transiently expressing HA-Flag-AtNDX and AtRING1A- or AtRING1B-GFP and used for Co-IP. The results indicated that AtRING1A-GFP and AtRING1B-GFP coimmunoprecipitated HA-Flag-AtNDX (Figure 3B). Then, we used GFP beads to immunoprecipitate proteins extracted from 10-d–old transgenic seedlings (two lines) containing AtRING1A-GFP driven by a super promoter to detect whether the endogenous AtNDX protein could coimmunoprecipitate with AtRING1A-GFP. An immunoblot assay with anti-NDX antibodies showed that endogenous AtNDX protein coimmunoprecipitated with AtRING1A-GFP (Figure 3C).

To examine the natural interaction between AtNDX and AtRING1A/B, we used anti-NDX antibodies in immunoprecipitation experiments to identify AtNDX-associated proteins from 10-d–old seedlings. After mass spectrometry analysis, we identified AtRING1A and AtBMI1A, suggesting that AtNDX is associated with PRC1 core components in vivo (Figure 3D). Therefore, we tested whether there were direct interactions between AtNDX and other PRC1 components such as AtBMI1A, AtBMI1B, AtBMI1C, AtEMF1, or LHP1 using the yeast two-hybrid assay. However, we did not find any interaction (Supplemental Figure 5). To determine which parts of AtRING1A/B and AtNDX confer their physical interaction, different deletions were tested in the yeast two-hybrid assay. Deletion analysis revealed that the C terminus of AtRING1A/B, containing the RING-FINGER AND WD40 ASSOCIATED UBIQUITIN-LIKE domain, is sufficient to bind AtNDX (Figure 3E), while the full-length AtNDX protein is required for their interaction (Figure 3F). Together, our data demonstrate that AtNDX interacts with AtRING1A/B in vitro and in vivo.

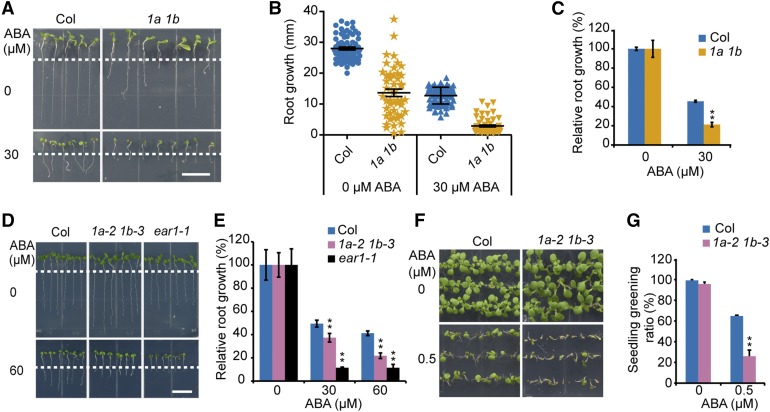

The atring1a atring1b Double Mutants Are Hypersensitive to ABA in Primary Root Growth and Seedling Establishment

To investigate the role of AtRING1A/B in the ABA response, we examined the phenotype of atring1a and atring1b single and double mutants on MS medium containing ABA. Single mutants for atring1 or atbmi1 do not show apparent morphological phenotypes except for a late flowering phenotype of atring1a (Shen et al., 2014). However, the atring1a/b and atbmi1a/b double mutants displayed strong embryonic defects during postgermination (see Supplemental Figure 6 for mutant information), which is consistent with the derepression of several key regulatory genes implicated in embryogenesis and stem cell activity (Xu and Shen, 2008; Bratzel et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2010). The expression of AtRING1A/B was not affected in ndx mutants and the expression of AtNDX was not affected in the ring mutants (Supplemental Figures 6B to 6D). The atring1a and atring1b-2 single mutants displayed similar ABA sensitivity to the wild type (Supplemental Figures 7A to 7D and Supplemental Figures 8A to 8D). We then selected 5-d old atring1a atring1b double mutants according to the abnormal cotyledon phenotypes on MS medium and transferred them onto medium supplemented with or without ABA for 4 d. Although atring1a atring1b mutants displayed various root lengths on MS medium, their relative root growth (i.e. growth on ABA medium relative to growth on ABA-free medium) was significantly more sensitive to ABA than that of the wild type (Figures 4A to 4C).

Figure 4.

The atring1a atring1b Double Mutants Are Hypersensitive to ABA in Seedling Establishment and Primary Root Growth.

(A) Primary root growth of atring1a atring1b (1a 1b) double mutant is hypersensitive to ABA compared with the wild type. Four-d–old seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to an MS medium supplemented with 30 μM of ABA for 3 d before being photographed. Scale bar = 1 cm.

(B) Statistical analysis of primary root growth in (A). Error bars represent ±se of 45 seedlings from three biological repeats.

(C) Statistical analysis of relative root growth in (A). The root growth of wild type and double mutant on MS medium without ABA was set to 100%. Error bars represent ±se of 45 seedlings from three biological repeats. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(D) Primary root growth of atring1a-2 atring1b-3 (1a-2 1b-3) double mutant is hypersensitive to ABA compared with the wild type. Four-d–old seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to an MS medium supplemented with 60 μM of ABA for 4 d before being photographed. Scale bar = 1 cm.

(E) Statistical analysis of relative root growth in different concentrations of ABA. The primary root growth of the wild type and atring1a-2 atring1b-3 double mutant (1a-2 1b-3) on MS medium without ABA was set to 100%. ear1-1 served as the positive control. Error bars represent ±se of 10 seedlings from one representative experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(F) Seedling establishment of atring1a-2 atring1b-3 double mutant (1a-2 1b-3) is hypersensitive to ABA. The seeds were germinated on MS medium supplemented with 0.5 μM of ABA for 9 d before being photographed.

(G) The seedling greening ratio in (F). Error bars represent ±se of ∼90 seeds from three plates for one experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared with wild type: **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

Because the atring1a atring1b double mutant is sterile, we were unable to test the seed cotyledon greening phenotype on ABA-containing medium. We then used a weak double mutant, ring1a-2 ring1b-3, in which a T-DNA fragment is inserted in the promoter region of AtRING1A, resulting in reduced expression of AtRING1A compared with the wild type and a more uniform phenotype (Supplemental Figure 6; Li et al., 2017). The atring1a-2 atring1b-3 double mutant was significantly more sensitive to ABA with respect to inhibition of seedling establishment than the wild type, and ear1-1 served as the ABA-hypersensitive control (Figures 4D to 4G). In conclusion, these results revealed that AtRING1A and AtRING1B negatively regulate ABA responses with respect to seedling establishment.

To examine the genetic interaction between AtNDX and AtRING1A/B, we constructed ndx-5 atring1a and ndx-5 atring1b-2 double mutants and tested their phenotypes on ABA medium. The ndx-5 atring1a mutant displayed slightly but not significantly increased ABA sensitivity with respect to inhibition of root growth and substantially increased ABA sensitivity with respect to inhibition of seedling establishment (Supplemental Figures 7A to 7D), while the ndx-5 atring1b-2 double mutant showed similar sensitivity to the ndx-5 single mutant (Supplemental Figures 8A to 8D). The ndx-5 atring1a double mutant even exhibited shorter roots and smaller cotyledons on MS medium compared with wild type (Supplemental Figure 7C). The additive effects of AtNDX and AtRING1A could be due to each protein having specific additional targets. Our data suggest that AtRING1A plays a broader, more important role than AtRING1B as demonstrated by its role in flowering control (Shen et al., 2014). Collectively, the above results indicate that the AtNDX and AtRING1A/B proteins are involved in some ABA-mediated responses.

AtNDX and AtRING1A/B Coregulate the Expression of ABI4 and Some ABA-Responsive Genes

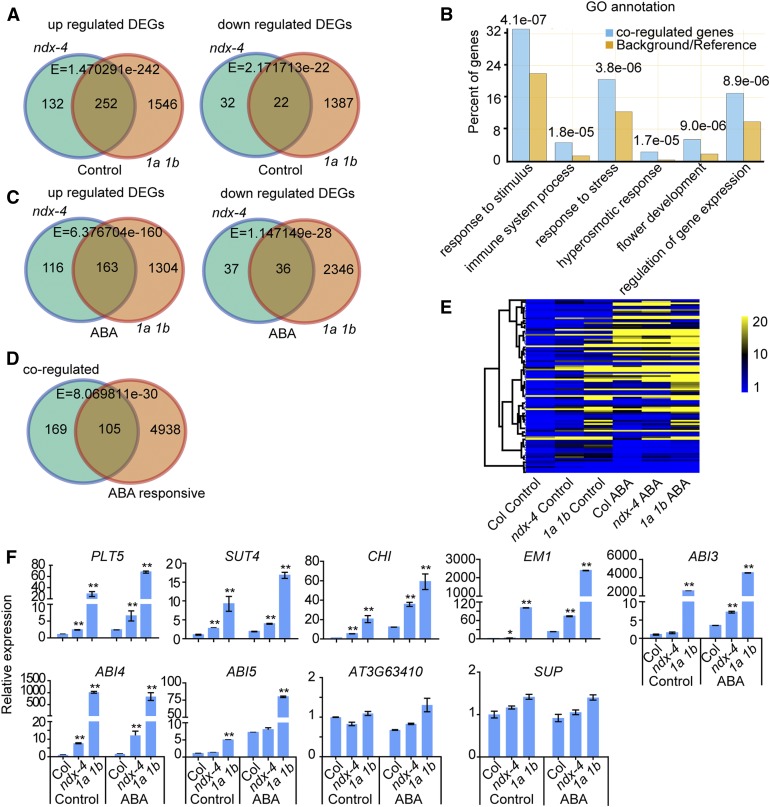

Because AtNDX and AtRING1A/B interact with each other in vivo and both mutants are hypersensitive to ABA in seed germination, seedling establishment, and root growth, we speculated that they might regulate some common genes involved in ABA responses. Therefore, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments to profile the transcriptome of ndx-4, atring1a atring1b, and the wild type under different conditions. We used ndx-4 because it is a T-DNA insertion mutant with a cleaner genetic background than the EMS mutants (ndx-5 and ndx-6). Total RNAs were isolated from 7-d–old seedlings treated with or without ABA for 3 h and used for mRNA-seq library construction. We sequenced two biological replicates for each sample on a NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina) and obtained more than 30 million paired-end clean reads for each replicate. RNA-seq reads were mapped back to The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR10) genome, and gene expression levels were quantified using the software Cuffdiff (Trapnell et al., 2013). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were filtered with a false discovery rate < 0.05 and fold change > 2, and required to have an expression >1 Fragments Per Kilobase per Million (FPKM; Trapnell et al., 2013).

Under normal conditions (i.e. no ABA treatment), 384 and 1,798 genes were upregulated in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b, respectively, while 54 and 1,409 genes were downregulated in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b, respectively, compared with the wild type (Figure 5A; Supplemental Data Set, Sheets 1 to 11). Among these genes, 252 were co-upregulated and 22 were co-downregulated in the two mutants (Figure 5A). We classified the genes coregulated by AtNDX and AtRING1A/B under normal conditions and found that these genes encode proteins with various functions, most of them annotated as stimulus/stress responses and developmental processes (Figure 5B). Under ABA treatment, 279 and 1,467 genes were upregulated while 73 and 2,382 genes were downregulated in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b, respectively, compared with the wild type (Figure 5C). Among them, 163 genes were co-upregulated and 36 genes were co-downregulated in the two mutants (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

AtNDX and AtRING1A/B Coregulate ABI4 and a Series of ABA-Responsive Genes.

(A) Venn diagram shows the number of overlapped up- and downregulated DEGs in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b double mutant (1a 1b) compared with the wild type under control conditions.

(B) GO annotation analysis of AtNDX and AtRING1A/B coregulated genes. The abscissa represents a part of GO terms with significant enrichment, the ordinate represents the ratio of the genes enriched in the GO term to the total number of genes, and the number represents the E value of the significance analysis compared with the reference genome (TAIR10, v2017).

(C) Venn diagram shows the number of overlapped up- and downregulated DEGs in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b double mutant (1a 1b) compared with the wild type under ABA treatment conditions. Seven-d–old seedlings were treated with 0 μM or 60 μM of ABA for 3 h.

(D) Venn diagram shows the overlapped number of co-up- and downregulated genes under normal conditions in ndx-4 and the atring1a atring1b double mutant (1a 1b), which are ABA-responsive genes in the wild type.

(E) Heat map shows that the ABA-responsive genes coregulated by AtNDX and AtRING1A/B in (D) were mainly upregulated in the ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b double mutant. The unit of expression is FPKM.

(F) Relative expression level analyses of ABA-related genes in the ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b double mutant (1a 1b). For each sample, 7-d–old seedlings were treated with 0 μM of ABA (Control) or 60 μM of ABA (ABA) for 3 h, then the total RNAs were extracted. Error bars represent ±se of three technical replicates from one experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared with wild type: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

To identify the genes that lead to ABA-hypersensitive phenotypes in the ndx and atring1a atring1b mutants, we examined the overlap between the coregulated genes in the two mutants under normal conditions and the genes regulated by ABA signaling in the wild type. In the wild type, 2,269 genes were ABA-induced and 2,774 genes were ABA-repressed. Among the total 279 coregulated genes in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b under normal conditions, 105 genes were responsive to ABA in the wild type, including 80 ABA-induced genes and 25 ABA-repressed genes (Figure 5D; Supplemental Data Set, Sheet 12). We then compared the expression levels of these coregulated and ABA-responsive genes under normal and ABA treatment conditions. Heat map analysis indicated that the expression levels of most of these coregulated genes in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b were higher than those in the wild type under both normal conditions and ABA treatment (Figure 5E).

We used RT-qPCR to confirm the expression of a sample of genes, including PLETHORA5 (PLT5), SUCROSE TRANSPORTER4 (SUT4), CHALCONE ISOMERASE (CHI), and LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT1 (EM1) from those that were both coregulated and ABA-responsive, and AT3G63410 from those that were neither coregulated nor ABA-responsive and found the results to be consistent with the RNA-seq data. SUPERMAN (SUP) served as a control for no change in expression (Figure 5F). We checked the expression levels of several major components in the ABA signaling pathway and found that ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 displayed much higher expression in atring1a atring1b than in the wild type (Figure 5F), but were not identified by RNA-seq owing to their low expression (ABI3, ABI4) or their insignificant difference in expression between ndx-4 and wild type (ABI5). The RT-qPCR results indicated that ABI3 and ABI4 were also expressed at higher levels in ndx-4 than in the wild type in the presence of ABA, but ABI5 was not (Figure 5F), suggesting that the expression of ABI3 and ABI4 is modulated by AtNDX.

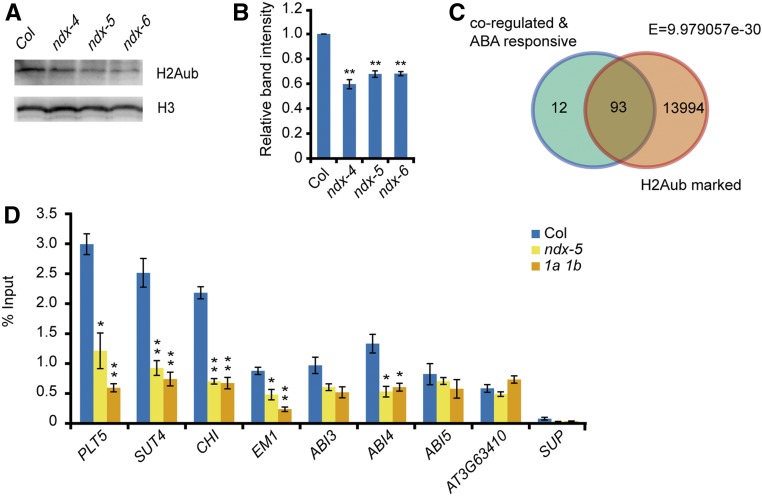

AtNDX Is Required for Normal H2Aub Levels in ABI4 and Other ABA-Responsive Genes

As core components of PRC1, AtRING1A/B mediate H2Aub in vitro and in vivo (Bratzel et al., 2010; Li et al., 2017). As AtNDX interacts with AtRING1A/B, we wanted to know whether the H2Aub level would be affected by AtNDX. We performed immunoblotting analysis using nuclear proteins extracted from 7-d–old seedlings. Interestingly, we found that the total H2Aub level was significantly reduced in each of the three ndx mutants (Figures 6A and 6B). Because AtNDX did not affect the expression of AtRING1A/B (Supplemental Figure 6), these results suggest that AtNDX is required for H2Aub modification, which most likely relies on protein interaction between AtNDX and AtRING1A/B. We hypothesize that if PRC1 works with AtNDX to regulate its target genes, the H2Aub on some loci should be altered in the ndx mutants. Referring to published data (Zhou et al., 2017), we identified 93 H2Aub-marked genes, representing ∼84% of the 105 coregulated and ABA-responsive genes (Figure 6C). We then selected some of these genes (Supplemental Figure 9) and checked their H2Aub levels by a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. Among these genes, the H2Aub levels of PLT5, SUT4, CHI, EM1, and ABI4 were significantly reduced in both ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b compared with the wild type, while the H2Aub level of ABI3 was reduced slightly but not significantly. The H2Aub levels of AT3G63410 and ABI5 were apparently unchanged (Figure 6D), which is consistent with the lack of difference in their expression levels in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b relative to the wild type (Figure 5F). SUPERMAN (SUP)was used as a negative control without H2Aub. Collectively, our results demonstrate that AtNDX and AtRING1A/B affect H2Aub levels of ABI4 and some ABA-responsive genes. These results suggest that that H2Aub levels are negatively correlated with the expression levels of some genes, but they are not necessarily linearly related, which is similar to several repressive histone modifications reported before (Huang et al., 2013).

Figure 6.

AtNDX and AtRING1A/B Regulate H2Aub Levels of ABI4 and ABA-Responsive Genes.

(A) Immunoblot assay indicates that the H2Aub levels in ndx mutants are reduced compared with the wild type. The nuclear proteins of 10-d–old seedlings were extracted and detected with H2Aub antibody, and H3 was used as an internal control.

(B) Statistical analysis of relative band intensity in (A). The band intensity was quantified by the software ImageJ, and the ratio of H2Aub to H3 in wild type was set to 1. Error bars represent ±se of three biological replicates. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(C) Venn diagram shows the number of overlapped genes between AtNDX and AtRING1A/B coregulated ABA-responsive genes and H2Aub-marked genes.

(D) ChIP-qPCR analysis shows that the H2Aub levels of ABI4 and ABA-responsive genes are reduced in ndx-5 and atring1a atring1b double mutant (1a 1b). The checked regions are labeled with the red lines below the gene diagrams in Supplemental Figure 9. Error bars represent ±se of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared with wild type: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

ABI4 Is a Direct Target of AtNDX

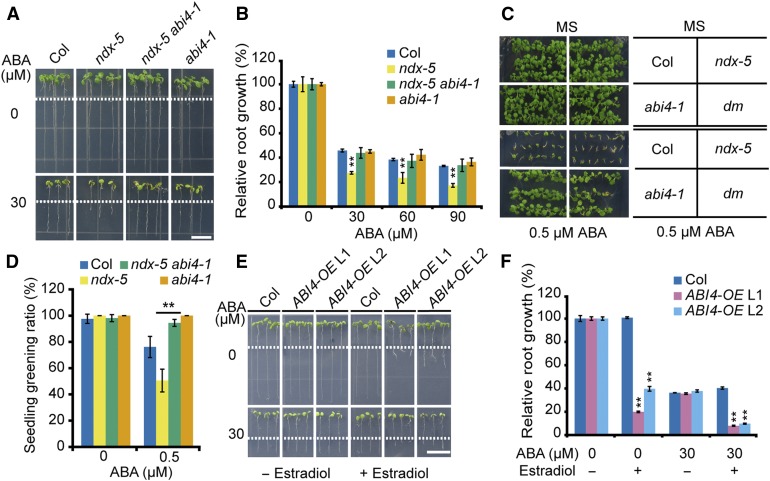

To find the possible targets of AtNDX in ABA-regulated root growth, we performed genetic analyses of several major components in the ABA signaling pathway. We found that the abi4-1 mutation could rescue the ABA-hypersensitive phenotype of the ndx-5 mutant with respect to both primary root growth and seedling establishment (Figures 7A to 7D). However, abi4-1 single mutants showed similar ABA sensitivity in primary root growth as the wild type (Figures 7A and 7B). This result suggests that as a positive regulator, ABI4 level in the wild type is not high enough to inhibit the primary root growth under ABA treatment, but the higher expression of ABI4 in ndx-5 mutants leads to more sensitivity to ABA in primary root growth, compared with in the wild type.

Figure 7.

ABI4 Mutations Rescue the ABA-Hypersensitive Phenotype of ndx-5 and ABI4-Overexpressing Transgenic Lines Display ABA-Hypersensitive Phenotype.

(A) ndx-5 abi4-1 double mutant rescues the ABA-hypersensitive phenotype of ndx-5 in root growth. Five-d–old seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to an MS medium supplemented with 30 μM of ABA for 4 d before being photographed. Scale bar = 1 cm.

(B) Statistical analysis of relative root growth with different concentrations of ABA treatment. The root growth of each genotype on MS medium without ABA was set to 100%. Error bars represent ±se of 15 seedlings from one representative experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(C) ndx-5 abi4-1 double mutant rescues the ABA-hypersensitive phenotype of ndx-5 in seedling establishment. The seeds were germinated on MS medium supplemented with 0 or 0.5 μM of ABA for 9 d before being photographed.

(D) The seedling greening ratio in (C). Error bars represent ±se of ∼90 seeds from three plates in one experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(E) Overexpression of ABI4 inhibits the root growth and confers ABA hypersensitivity. Five-d–old wild type and the transgenic wild-type plants with inducible ABI4 overexpression were transferred to MS medium supplemented with 0 or 30 μM of ABA and without or with estradiol for 3 d before being photographed. Scale bar = 1 cm.

(F) Statistical analysis of relative root growth in (E). The root growth of each genotype on MS medium without ABA and estradiol was set to 100%. Error bars represent ±se of 10 seedlings from three plates for one representative experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

To further confirm the results, we created two CRISPR/Cas9 abi4 mutants in ndx-4 and ndx-5 using an egg-specific promoter system (Wang et al., 2015), among which a chimeric protein was produced in abi4-C1 and a truncated protein in abi4-C2. The ABA-sensitive phenotypes of ndx-4 abi4-C1 and ndx-5 abi4-C2 were similar to those of the wild type (Supplemental Figures 10A to 10D), confirming that ABI4 acts at or downstream of AtNDX in ABA signaling. By contrast, ndx-5 abi1-1 (Col-0), ndx-5 abi2-1 (Landsberg erecta [Ler]) double mutants, and the ndx-5 snrk2.2/2.3 triple mutant displayed intermediate ABA-sensitive phenotypes, suggesting that AtNDX is one of the downstream targets of these components in the early ABA signaling pathway (Supplemental Figures 11A to 11F). The ndx-5 abi3-1 and ndx-5 abi5 double mutants displayed similar primary root growth phenotypes to ndx-5, but exhibited ABA-insensitive seedling establishment phenotypes similar to those of abi3-1 and abi5 (Supplemental Figures 11G to 11L). These findings suggest that ABI3 and ABI5 act at or downstream of AtNDX in seedling establishment, but play different roles in ABA-inhibited primary root growth. Indeed, recently it was found that ABI5 mutations can suppress the primary root ABA-sensitive phenotype of the golden2-like1 golden2-like2 wrky40 triple mutant in Arabidopsis, suggesting that ABI5 also functions in primary root growth, although like abi4, the abi5 single mutant did not show any primary root growth phenotype to ABA (Ahmad et al., 2019).

Although studies have reported diverse functions of ABI4, including regulating lateral root growth (Shkolnik-Inbar and Bar-Zvi, 2010) and increasing ABA accumulation, decreasing gibberellic acid content, and causing dwarfing when overexpressed (Shu et al., 2016), few studies have examined the role of ABI4 in regulating primary root growth. To test this, we produced estradiol-inducible ABI4-overexpression transgenic lines and examined their phenotype on ABA medium. High expression of ABI4 induced by addition of estradiol inhibited primary root growth on MS medium, which is consistent with previous results on ectopic, constitutive ABI4 expression (Söderman et al., 2000). ABI4 overexpression also caused increased sensitivity to ABA in terms of primary root growth (Figures 7E and 7F). These results suggest that ABI4 plays a positive role in ABA inhibition of primary root growth.

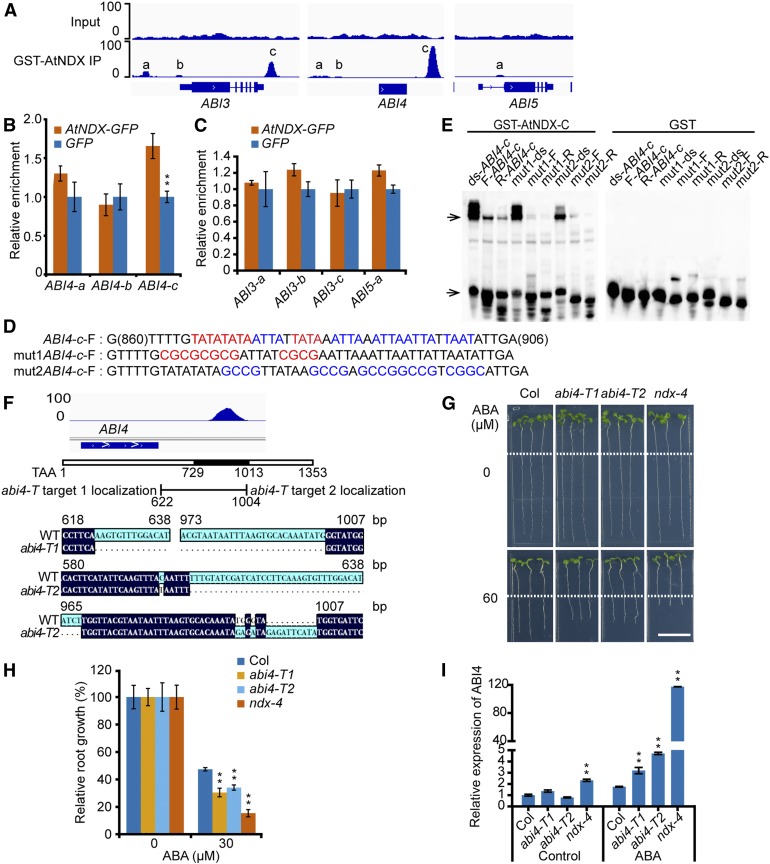

The above results prompted us to test whether AtNDX directly targets ABI4. To search for AtNDX targets, we performed ChIP-seq analysis using anti-NDX antibodies or using AtNDX-GFP complemented ndx seedlings with anti-GFP antibodies, but failed to pull down enough genomic DNA for further analysis, probably because of low antibody quality or a low amount of AtNDX protein. We then used DNA affinity purification sequencing (DAP-seq) to examine AtNDX binding (O’Malley et al., 2016). AtNDX is a homeodomain (HD)-containing protein that belongs to a large family of transcription factors with the HD preferably binding to a core TAAT motif (Mukherjee et al., 2009; Christensen et al., 2012). The homeodomain of AtNDX is atypical and highly divergent (Mukherjee et al., 2009). AtNDX has been reported to bind the ssDNA at the 3′ region of FLC in a non-sequence–specific manner (Sun et al., 2013). We used the GST-fused C terminus of AtNDX protein (including the HD and NDXB domain) to pull down fragmented genomic DNA in vitro, as we could not purify full-length AtNDX from E. coli (Sun et al., 2013). The DAP-seq analysis revealed that the AtNDX fragment preferred to bind the promoter and terminal region of genes and that the AtNDX binding sequence usually possessed a high AT ratio (Supplemental Figures 12A and 12B).

We noticed that there were both weak and strong binding signals close to the ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 genes (Figure 8A). We further examined whether these loci were targeted by AtNDX in vivo using a ChIP-PCR assay. Here we used the ndx-1 (eoc1-1) mutant complemented by AtNDX driven by its native promoter and fused with GFP in frame (Sun et al., 2013). Seven-d–old seedlings were used for a ChIP-PCR assay with GFP antibodies, and pro35S:GFP transgenic seedlings were used as a control. We found that a significant enrichment was detected around the ABI4 downstream region (∼730 to 1,013 bp from the putative stop codon), but not in the promoter region (Figure 8B). For ABI3 and ABI5, we did not detect a clear AtNDX enrichment (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

ABI4 is a Direct Target of AtNDX.

(A) DAP-seq genome browser views show AtNDX binding signals around ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 genes.

(B) and (C) ChIP-qPCR analyses show that AtNDX binds to the ABI4 downstream sequence in vivo. The letters in (A) indicate the tested regions. DNA fragments immunoprecipitated by GFP beads were quantified by qPCR and normalized to the internal control ACT4; the relative enrichment in AtNDX-GFP over GFP is presented. Error bars represent ±se of three technical replicates from one experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. Asterisks indicate significant difference: **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(D) The probes used in EMSA. The sequence of ABI4-c-F probe is from the center of ABI4-c region in (A). The red letters represents the TATA motif; the blue letters represent the ATTA motif; mut1 and mut2 probes show the corresponding mutation sequence; F, forward strand DNA.

(E) EMSA shows that recombinant GST-AtNDX-C binds to ABI4 downstream sequence in vitro. The upper right arrow indicates the bound probe; the lower right arrow indicates the free probe; ds, double-stranded probe formed by annealing; F, forward single-stranded probe; R, reverse single-stranded probe. GST protein was used as a negative control.

(F) The diagram of the binding peak of ABI4 downstream by AtNDX in DAP-seq and target location of CRISPR/Cas9. The sequence alignments show that the fragments from ABI4 downstream bases 624 to 1,000 (counting after the first base of stop codon in ABI4) in abi4-T1 and the bases 605 to 968 in abi4-T2 were deleted, and there are insert mutants in target 2 in abi4-T2. These mutations almost cover the whole binding peak sequence of AtNDX.

(G) abi4-T1 and abi4-T2 lines confer more ABA sensitivity than the wild type, but less ABA-sensitive than ndx-4. Four-d–old seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to an MS medium supplemented 0 or 30 μM of ABA for 4 d before being photographed. Scale bar = 1 cm.

(H) Statistical analysis of relative root growth in (G). The root growth of each genotype on MS medium without ABA was set to 100%. Error bars represent ±se of 12 seedlings from three plates for one representative experiment, and three independent experiments were done with similar results. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

(I) Relative transcript levels of ABI4 in 8-d–old seedlings. Seedlings were grown on MS medium for 4 d, then transferred to an MS medium supplemented with 0 μM or 30 μM ABA for 4 d before being harvested. Error bars represent ±se of three technical replicates. **P < 0.01, Student’s t test.

We then confirmed the binding in vitro through an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) at the DAP-seq peak localized in the ABI4 downstream region (Figures 8D and 8E). We noticed that AtNDX-GST could bind to both ssDNA and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) of this region, but had stronger binding affinity to dsDNA (Figure 8E). This differs from the results of a previous study, in which AtNDX only bound to ssDNA (Sun et al., 2013), probably due to the different probes used in two assays (Sun et al., 2013). These results suggest that AtNDX can bind both ssDNA and dsDNA. The GST negative control did not show any binding affinity. We observed that either TATA or ATTA mutations decreased the binding affinity (Figure 8E). Moreover, AtNDX binding affinity seemed to be related to the AT content of the sequence (Figure 8E).

As AtNDX can bind the downstream region of ABI4 and repress its expression, we wanted to know whether deletion of the ABI4 downstream fragment would affect ABI4 expression. We used CRISPR/Cas9 to create two deletion mutants (abi4-T1, abi4-T2) in the downstream region of ABI4 (Wang et al., 2015). The two CRISPR/Cas9 mutants were more sensitive to ABA than the wild type, but less sensitive to ABA than ndx-4 with respect to primary root growth (Figures 8G to 8I). Consistently, we found that the expression of ABI4 under ABA treatment was significantly increased in these two CRISPR/Cas9 lines (Figure 8I). These results suggest that the downstream region of ABI4 plays a negative role in regulation of ABI4 expression.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we provide several lines of evidence showing that AtNDX interacts with the PRC1 core components AtRING1A and AtRING1B, and that they coregulate the H2Aub modification and expression of some ABA-responsive genes (Figures 3, 5, and 6). Interestingly, ABA negatively regulates the expression of AtNDX. Under normal conditions, a larger number of AtNDX and AtRING1A/B coregulated ABA-responsive genes were upregulated than downregulated in ndx-4 and atring1a atring1b mutants relative to wild type, suggesting that AtNDX and AtRING1A/B are required for repressing these genes under the normal conditions. AtNDX and AtRING1A/B mutants are hypersensitive to ABA in seed germination, seedling establishment, and root growth, but not in ABA-promoted stomatal closure, indicating that they are negative regulators in some ABA-mediated responses. We found that in ndx mutants, the H2Aub level was apparently reduced but the expression levels of AtRING1A and AtRING1B were unchanged, suggesting that H2Aub modification is mediated by AtNDX at the posttranscriptional level. Furthermore, most of the AtNDX and AtRING1A/B coregulated ABA-responsive genes have H2Aub modification. We found an apparent reduction in H2Aub in these coregulated ABA-responsive genes, including ABI4, in the ndx and atring1a atring1b mutants. So we speculate that AtNDX might relate to the AtRING1A/B’s function in modifying the target genes, such as ABI4.

Under drought stress conditions, the upstream components in the ABA signaling pathway such as ABA receptors, SnRKs, and PP2Cs usually modulate both the expression of ABA-responsive genes at the transcriptional level in a relatively slow response and guard cell movement at the posttranscriptional level in a quick response (Cutler et al., 2010; Zhu, 2016; Qi et al., 2018). Here we found that ndx mutants exhibited ABA super-sensitivity with respect to seedling establishment and primary root growth. Our genetic analyses with classic ABA-responsive mutants indicate that ndx mutation compromised the ABA-insensitive phenotypes of abi1-1 (Col-0; Hua et al., 2012), abi2-1 (Leung et al., 1997), and snrk2.2/2.3 (Fujii et al., 2007) double mutants, further suggesting that AtNDX is one of the downstream targets in ABA signaling (Supplemental Figure 11). During the seedling establishment stage, the ABA-insensitive phenotypes of abi3 (Giraudat et al., 1992), abi4 (Finkelstein et al., 1998), and abi5 (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000) were not changed by introducing the ndx mutation, suggesting that ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 function genetically downstream of AtNDX. The expression of ABI3 is increased in ndx, but we did not find that AtNDX could directly bind to ABI3 in the ChIP-PCR analysis, suggesting either that AtNDX does not directly target ABI3 or that our technique is not sensitive enough to detect the binding. Indeed, the regulation network of ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 is very complex (Söderman et al., 2000; Feng et al., 2014).

Although previous studies had shown diverse functions of ABI4 (Wind et al., 2013; Feng et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Shu et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2017), its role in regulating primary root growth in an abi4 mutant had not been revealed. Our genetic studies show that ABI4 mutations can rescue the ABA-hypersensitive seedling establishment and primary root growth phenotypes of ndx mutants, and that overexpression of ABI4 in an inducible manner retarded primary root growth and increased sensitivity to ABA. These results suggest that ABI4 functions downstream of AtNDX in regulating primary root growth. Given that abi4-1 does not show any primary root growth difference compared to the wild type under ABA treatment, we speculate one reason is that the expression of ABI4 is precisely and strictly regulated during plant development. In the wild type after germination, ABI4 is gradually silenced and stays at a very low expression level that is not enough to inhibit primary root growth under ABA treatment. However, in the ndx mutants and ABI4 overexpression lines, ABI4 is expressed to reach a high level that is sufficient to inhibit the primary root growth. Therefore, we think the targets of ABI4 are probably directly related to ABA response.

In our study, we found by DAP-seq and EMSA that AtNDX is able to bind the downstream region of ABI4, while H2Aub is mainly distributed in the ABI4 gene body, especially in the first exon (Zhou et al., 2017). How then does AtNDX promote H2Aub modification and repress ABI4 expression? We speculate that AtNDX might bind the downstream region of ABI4 and then form a DNA loop, allowing it to interact with AtRNG1A/B in the coding region, promoting H2Aub modification and suppressing ABI4 expression (Figure 9). One of the examples is a recent study on the expression of GLABRA1 (GL1), in which the KANADI1-TARGET OF EAT1 complex binds the 3′ downstream region of GL1 and then forms a loop in the promoter region, repressing GL1 expression and inhibiting trichome formation (Wang et al., 2019). Genome-wide Hi-C (a genome-wide chromatin conformation capture) analysis in Arabidopsis indicates that promoter regions with repressive histone modification markers such as H3K27me3 show a strong tendency to form conformational linkages over long distances in gene bodies (Liu et al., 2016). ABI4 is also regulated by BPC-recruited PRC2 in the promoter, which mediates H3K27me3 modification (Mu et al., 2017). Some components of PRC1 could interact with those of the PRC2 complex to form a large complex (Wang and Shen, 2018). It is possible that AtNDX interacts with AtRING1A/B to form a DNA loop after it binds to the downstream region of ABI4 (Figure 9). In this study, we attempted to test this hypothesis by the chromatin conformation capture technique, but failed due to a lack of suitable restriction enzyme recognition sites in this region. Nevertheless, the deletion by CRISPR/Cas9 of the ABI4 downstream region where AtNDX most likely binds increased ABI4 expression and ABA sensitivity. The deletion lines were more ABA-sensitive in primary root growth than the wild type, but less ABA-sensitive than ndx, suggesting that AtNDX not only works in the downstream region of ABI4, but also, for example, works together with PRC1 in the ABI4 coding region. Without ABA treatment, the expression of ABI4 in two deletion lines was not increased, but increased in ndx mutant, suggesting that AtNDX is required for repressing ABI4 expression under normal condition (Figure 8I).

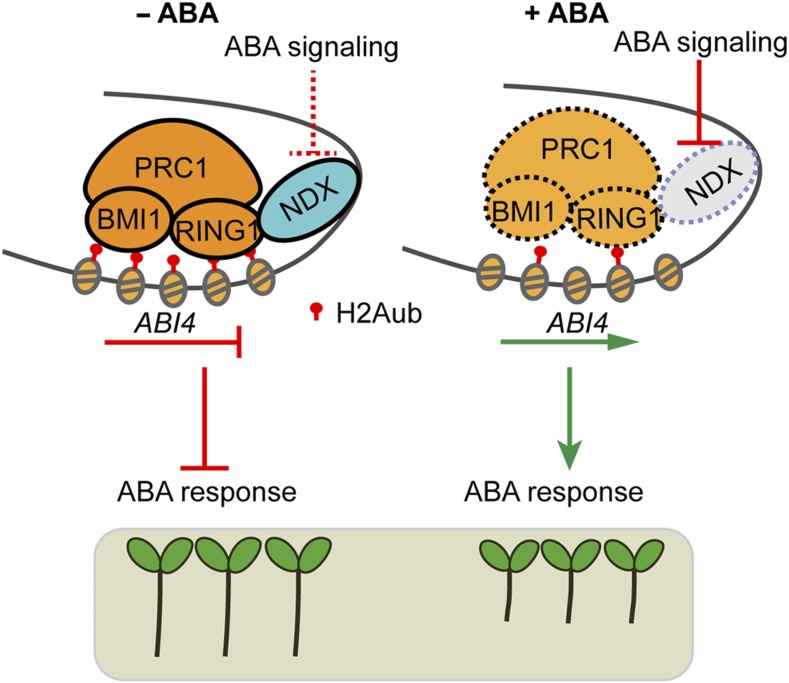

Figure 9.

A Proposed Model for the Role of AtNDX and AtRING1A/B in ABA Signaling.

Under normal conditions (−ABA), AtNDX binds to the downstream region of ABI4 and interacts with AtRING1A/B in the coding region, which promotes H2Aub modification and suppresses ABI4 expression. Under stress conditions (+ABA), the expression of AtNDX is repressed by ABA signaling, which results in activation of the ABI4 expression.

In our study, it was very hard to obtain a stably overexpressed ABI4 transgenic line in later generations, suggesting that ABI4 can be easily silenced, likely due to its sequence in coding region. A previous study showed that AtNDX could stabilize the R-loop structure of FLC (Sun et al., 2013), and this study reveals a novel role for AtNDX working with PRC1 for gene repression, suggesting that AtNDX uses different regulatory mechanisms to control gene expression. When comparing gene expression patterns, the number of genes coregulated by AtNDX and AtRING1A/AtRING1B was not very large; one possible explanation is that some genes may be regulated by AtNDX-mediated R-loop formation during transcription. Recent studies have indicated that, like other epigenetic markers such as histone modification and DNA methylation, R-loops play crucial roles in various cellular processes including gene expression and DNA repair (Xu et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Crossley et al., 2019). To fully understand the functions of AtNDX, it will be necessary to perform genome-wide profiles of R-loops and H2Aub in ndx and atring1a atring1b mutants. However, more improved techniques are needed as AtNDX protein availability is a limiting factor: the protein is not highly accumulated even when the gene is driven by the 35S promoter (this study; Sun et al., 2013). This may be also the possible reason for why the overexpressed AtNDX lines did not show ABA insensitivity while rescuing the ndx mutant phenotype.

Many studies have shown that epigenetic regulation is involved in plant abiotic stress responses (Chinnusamy et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2013). A recent study indicates that PRC2 attenuates ABA-induced senescence in Arabidopsis in a long-term process (Liu et al., 2018a). The PRC1 complex also represses the expression of some important genes in phase transitions during different developmental stages (Calonje, 2014; Wang and Shen, 2018). The connection between ABA signaling and chromatin modification has been explored in several previous studies (Chinnusamy et al., 2008; Saez et al., 2008; Han et al., 2012; Peirats-Llobet et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018b). For example, SWI3B, a subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, interacts with HYPERSENSITIVE TO ABA1 and positively modulates ABA signaling (Saez et al., 2008). The SWI/SNF ATPase BRAHMA can directly bind to the transcription start site of ABI5 and maintain the well-positioned nucleosome for repressing the expression of ABI5 (Han et al., 2012). The activity of BRAHMA is adversely regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation mediated by SnRK2s and PP2CA (Peirats-Llobet et al., 2016), which would result in activation of ABI5 or maintaining the repression status of ABI5, respectively. H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 marks were found to be involved in drought stress memory (Liu et al., 2014). ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX4 and ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX5 directly regulate the expression of ABA-HYPERSENSITIVE GERMINATION3 (encoding a PP2C) through H3K4 methylation by binding at the locus (Liu et al., 2018b). The finding in this study that AtNDX interacts with PRC1 core components AtRING1A/B to mediate ABA signaling provides novel evidence for the direct connection between ABA signaling and epigenetic regulation.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seeds were surface-sterilized and sown on MS medium containing 2% (w/v) Suc and 0.8% (w/v) or 0.9% (w/v) agar. After being stratified at 4°C for 3 d, the plates were transferred to a light incubator (model no. F17T8/TL841 bulb; PHILIPS) with a light intensity of 60 μE m−2 s−1 under 22-h light/2-h dark at 22°C. The mutants used in this study: Atring1a, Atring1b-2 (Shen et al., 2014), Atring1a−/−Atring1b+/− (Xu and Shen, 2008), ring1a-2 ring1b-3 (Li et al., 2017), eoc1-4 renamed as ndx-4 in this study (Sun et al., 2013), abi1-1 (Kong et al., 2015), snrk2.2/2.3 (Wang et al., 2018), and abi4-1 (Liu et al., 2010) were in the Columbia (Col-0) background; abi2-1, abi3-1 (Wang et al., 2011) were in the Landsberg erecta (Ler) background; and abi5 were in the Wassilewskija (Ws) background. The transgenic plants AtNDX-FLAG (in eoc1-4, ndx-4 in this study) and AtNDX-eGFP (in eoc1-1, ndx-1) renamed as proAtNDX:AtNDX-Flag and proAtNDX:AtNDX-GFP were as described by Sun et al. (2013). For transgenic plants overexpressing AtNDX and AtRING1A, their coding sequences were fused with the indicated tag and driven by the super promoter (Ni et al., 1995) and cloned into the pCAMBIA1300 vector. For the β-estradiol–inducible ABI4 overexpression lines, the coding sequence of ABI4 was fused with GFP tag and cloned into the pER8 vector (Zuo et al., 2000). The constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 and then transformed into the ndx-5 mutant or wild type by floral infiltration. The primers used to examine these mutants and construct the transgenic plants are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

To generate the ABI4 downstream deletion lines (abi4-T1 and abi4-T2), targeting the fragment from 618 bp and 1,007 bp downstream of ABI4 (counting after the ABI4 putative stop codon) was selected for CRISPR/Cas9 editing. The targets were cloned into the pHSE401 vector as previously described by Wang et al. (2015) and the constructs were transformed into Col-0 by floral dip. The transgenic T1 seeds were screened on MS medium containing 25 mg/L of hygromycin. To identify the deletion lines, ∼80 T1 plants were first screened by PCR, then verified by sequencing, and the homozygous mutants were used to generate T2. To generate ndx-4 abi4-C1 and ndx-5 abi4-C2 mutants, the same method was used, except that targets at the coding sequence of ABI4 were selected and the constructs were introduced into ndx-4 and ndx-5 mutant. T2 plants were harvested individually, and T3 seeds were screened on hygromycin medium for the non-hygromycin–resistant lines. The primers used to examine these mutants, to construct the CRISPR/Cas9 vector and transgenic plants, are listed in Supplemental Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Map-Based Cloning of AtNDX

The mutants ndx-5 and ndx-6 were isolated from ∼20,000 ethyl methyl sulfone (EMS)-mutated M2 seedlings based on the root bending assay. ndx-5 mutant plants were crossed with Ler plants. A total of ∼1,300 ndx-5 mutant plants were selected from the self-fertilized F2 population based on the ABA-hypersensitive phenotype on 30 μM of ABA. The simple-sequence–length polymorphism markers were used for mapping. The position of the AtNDX mutation was determined within BAC clone T4I9. All genes in the BAC clone T4I9 were sequenced, and the mutation in the At4g03090 gene was identified in ndx-5. ndx-6 was mapped to the same BAC clone as ndx-5, and a mutation in ndx-6 was found in At4g03090. For the complementation, an 8-kb fragment that included ∼3,000 bp upstream of the first putative ATG to 1,000 bp downstream of the putative stop codon TGA of At4g03090 gene was amplified and cloned into pCAMBIA1391 vector. The constructs were introduced into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 and then transformed into the ndx-5 mutant by floral infiltration. The several independent transgenic lines obtained were able to complement the abscisic acid (ABA)-hypersensitive phenotypes of ndx-5.

ABA-Related Phenotype Analyses

For the root growth assay, seeds were germinated on the vertically oriented plates, and 5-d–old seedlings were transferred to MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of ABA for 3 or 4 d. Then the seedlings were photographed and the root growth after transfer (below the white dotted line in Figures 1A, 4A, 4D, 7A, 7E, and 8G) was measured by the software ImageJ (https://imagej.en.softonic.com/). For the calculation of relative root growth, the root growth of each genotype on MS medium without ABA was set to 100%. For the seed germination greening ratio assay, seeds were sown on MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of ABA and grew for two to 11eleve days after sowing before being photographed, and the ratios of seedlings with ruptured endosperm, emerged radicals, and expended green cotyledons were calculated.

Observation of Root Meristem and Mature Epidermal Cell

To measure of meristem cell number, a drop of transparent liquid was added to a glass slide, and the root tips of the seedlings were immersed in the transparent liquid, then covered with a glass cover and placed under a model no. BX53 microscope (Olympus). The cells in the meristem were observed with a 20-fold objective lens and photographed. The transparent liquid contains 60 mL of deionized water, 7.5 g of Gum Arabic, 100 g of hydrated trichloroacetaldehyde, and 5 mL of glycerol.

To measure the length of mature epidermal cells, roots were treated according to the steps described previously by (Malamy and Benfey, 1997). The films were observed under a 10-fold objective lens and photographed, and the cell length was measured using the software ImageJ. For each root, the first five epidermal cells (near to the distal) from the first cell with root hair were measured and used to calculate the average length.

Physiological Experiments

For the water loss in detached leaves, shoots were cut from plants growing under normal conditions for four weeks, and placed on a piece of weighing paper under a light in a greenhouse and weighed immediately every 0.5 h or 1 h. The results are shown as a percentage of the fresh weight. More than two independent experiments were performed, each including three or four replicate shoots per line.

For stomatal density, epidermal strips were peeled from 4-week–old plants and the mesophyll cells were removed with a small brush. The cleaned epidermal strips were photographed under a model no. BX53 microscope (Olympus) with a 40-fold objective lens and photographed. The stomata numbers were counted.

GUS Staining

A 1,609-bp fragment upstream from the start codon ATG of AtNDX was amplified by PCR. The amplified fragment was cloned into the pCAMBIA1391 vector for a transcriptional fusion of the AtNDX promoter with the GUS coding region. Seven-d–old homozygous transgenic plants carrying proAtNDX:GUS were treated with 0 μM or 30 μM of ABA for 12 h, and incubated in GUS staining buffer (0.1 M of PBS, 0.5 mM of K4Fe[CN]6, 0.5 mM of K3Fe[CN]6, 1 mg/mL of X-gluc, and 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100) for 6 h at 37°C.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Five-d–old proAtNDX:AtNDX-GFP transgenic seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to MS medium supplemented with 0 μM or 30 μM of ABA for 12 h. Then seedlings were incubated in 10 μM of propidium iodide for 3 min (to visualize the cell) before being imaged with a model no. LSM710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). The roots were photographed under the same setting and the fluorescence intensities of the same area in the root MZ were measured by the software ImageJ.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

For yeast two-hybrid screening, a normalized universal Arabidopsis cDNA library (cat. no. 630487; Clontech) was screened with the full length of AtNDX as bait. The screening was performed according to the operating instruction. For construction of the bait and prey, the full length or truncated AtNDX and AtRING1A/B were fused into pGBKT7 (binding domain) or pGADT7 (activation domain) vectors. The plasmids were cotransfected into yeast strain AH109. Then the transfected yeast cells were plated on SD/-Leu/-Trp medium and SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp medium and cultured at 30°C for 5 d. The primers used for vector construction are listed in Supplemental Table 3.

Co-IP and Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assays

The Co-IP assays were performed as described by Wang et al. (2018). Briefly, the total proteins of Arabidopsis protoplasts transfected with pro35S:HA-Flag-AtNDX and proSuper:AtRING1A-GFP or proSuper:AtRING1B-GFP, or transgenic plants harboring proSuper:AtRING1A-GFP were extracted and immunoprecipitated by GFP beads (cat. no. gta-20; ChromoTek). The primers used for vector construction are listed in Supplemental Table 3. The immunoprecipitated proteins were detected with the indicated antibodies by immunoblotting analysis. The antibodies used were anti-GFP antibodies (cat. no. ab290; Abcam), anti-HA antibodies (cat. no. H6908; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-NDX antibodies (produced by Shanghai Youke Biotechnology). Anti-NDX antibodies are polyclonal antibodies prepared by immunizing rabbits with a peptide comprising the 589th to 879th amino acids of the AtNDX protein. For liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), total proteins were extracted from wild-type and ndx-5 mutant 10-d–old seedlings, and immunoprecipitated with anti-NDX antibodies, and the precipitated products were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis as described by Kong et al. (2015).

RNA-Seq Analyses

Seven-d–old seedlings were treated with half strength liquid MS medium supplemented with 0 μM or 60 μM of ABA for 3 h. The total RNAs were extracted using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (cat. no. 74104; Qiagen) and sent to Berry Genomics for library construction and sequencing. The sequencing was performed on the Novaseq6000 platform (Illumina). Each sample had two biological replicates and obtained ∼12G clean bases each replicate. RNA-seq reads were collapsed into nonredundant reads and mapped back to The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) 10 genome (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) with Araport 11 annotation using the tool Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) Aligner (http://code.google.com/p/rna-star/) with a maximum eight mismatches per pair reads (Dobin et al., 2013). The gene expression level was quantified using the available software Cuffdiff (http://cufflinks.cbcb.umd.edu/). The DEGs were filtered with a false discovery rate < 0.05 and fold change > 2, and required to have an expression >1 FPKM (Trapnell et al., 2013). The Venn diagrams were drawn on the website http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/ and the E values were calculated through hypergeometric test with the R software package. The heatmap was drawn based on the expression levels of indicated genes by the software MeV v4.9.0 with default parameters (Saeed et al., 2003). The raw data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are accessible through SRA accession code PRJNA556351 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA556351).

RT-qPCR

Seven-d–old seedlings were treated with different concentrations of ABA for 3 h, and the total RNAs were extracted with a HiPure Plant RNA Mini Kit (R4151; Magen). Four micrograms of RNAs were used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with a Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (cat. no. K1682; Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-qPCR was performed as described by Kong et al. (2015). The primers used for RT-qPCR were listed in Supplemental Table 5.

ChIP

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described by Zhang et al. (2016) with a little modification. For H2Aub ChIP, 10-d–old seedlings were ground into fine powder and cross linked with 1% (v/v) formaldehyde for 10 min. The nuclei were isolated and the chromatin was sonicated with a Bioruptor (Diagenode) and immunoprecipitated with the H2Aub antibody (cat. no. D27C4; Cell Signaling) and Protein A+G Magnetic Beads (cat. no. 16-663; Millipore). For AtNDX-GFP ChIP, 7-d–old proAtNDX:AtNDX-GFP/ndx-1 and pro35S:GFP/Col-0 transgenic plants were used and the chromatin was immunoprecipitated by GFP beads (cat. no. gta-20; ChromoTek). The precipitated DNAs were recovered with a ChIP DNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (cat. no. D5205; Zymo Research) and analyzed by RT-qPCR. The primers used for ChIP-qPCR are listed in Supplemental Table 6.

Purification of Recombinant Protein, EMSA, and DAP-Seq

The DNA binding and NDXB domain (1,800 to 2,634 bp) in the C-terminal of AtNDX was fused in frame with glutathione S-transferase (GST) in the pGEX-2T vector and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). The fused protein was induced by 1 mM of Isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubated overnight at 16°C. The recombinant protein was purified with Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For double-strand probes, the 5′-biotin-labeled DNA primers were made by 20 min of 100°C denaturation and renaturation in room temperature, and purified by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and a QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). For single-strand probes, the primers were denatured for 20 min and then transferred to ice immediately. Each 20-μL volume of binding reaction contained 10 fM of Biotin-probe and 1 μg of protein. The probes were incubated with the GST-AtNDX-C protein at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction products were separated by 6.5% (v/v) native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and detected according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DAP-seq was performed according to O’Malley et al. (2016) with a little modification. The genomic DNA was extracted from 7-d–old wild-type seedlings and fragmented with a Bioruptor (Diagenode) to 200 to 500 bp. The GST-AtNDX-C protein was first incubated with Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) for 2 h, and the free protein was washed out. Then the GST-AtNDX-C covered beads were incubated with 500 ng of fragmented DNA for 1 h. After washing out the free DNA, the affinity purified DNA was eluted and used for sequencing. Two repeats were sequenced and 5-M reads were obtained for each repeat. The clean data were mapped to the Arabidopsis genome (TAIR10) using the software BowTie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) with the following parameters: -N 1 -p 5 -q; and the NDX binding peaks were identified by the software MACS (v1.4.2; Zhang et al., 2008). The raw data have been deposited in the NCBI SRA and are accessible through SRA accession code PRJNA556351 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA556351).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the following accession numbers: AtNDX, AT4G03090; AtRING1A, AT5G44280; AtRING1B, AT1G03770; AtBMI1A, AT2G30580; AtBMI1B, AT1G06770; AtBMI1C, AT3G23060; AtEMF1, AT5G11530; LHP1, AT5G17690; PLT5, AT5G57390; SUT4, AT1G09960; CHI, AT2G43570; EM1, AT3G51810; ABI3, AT3G24650; ABI4, AT2G40220; ABI5, AT2G36270; ACT4, AT5G59370; SUP, AT3G23130. Mutants used in this article can be obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center under the following accession numbers: snrk2.2 (GABI-Kat 807G04), and snrk2.3 (SALK_107315). The RNA-seq data and DAP-seq data for this research have been deposited in the NCBI SRA under accession code PRJNA556351.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Root cell division and elongation of ndx-5 mutant are hypersensitive to ABA. Supports Figure 1.

Supplemental Figure 2. Seedling establishment and stomata movement analysis of AtNDX. Supports Figure 1.

Supplemental Figure 3. Map-based cloning and mutation analysis of AtNDX. Supports Figure 1.

Supplemental Figure 4. Complementation of ndx mutants. Supports Figure 1.

Supplemental Figure 5. AtNDX does not directly interact with other PRC1 components in yeast cells. Supports Figure 3.

Supplemental Figure 6. The transcriptional levels of AtNDX and AtRING1A/B in corresponding mutants. Supports Figure 5.

Supplemental Figure 7. ndx-5 atring1a double mutant is more sensitive to ABA than ndx-5 in seed germination but not in primary root growth. Supports Figure 5.

Supplemental Figure 8. ndx-5 atring1b-2 double mutant shows similar sensitivity with ndx-5 to ABA in seedling establishment and primary root growth. Supports Figure 5.

Supplemental Figure 9. ChIP-seq genome browser views from published results. Supports Figure 6.

Supplemental Figure 10. Disruption of ABI4 by CRISPR/Cas9 rescues the ABA-hypersensitive phenotype of ndx mutants. Supports Figure 7.

Supplemental Figure 11. Genetic analysis of AtNDX and ABA signaling pathway members. Supports Figure 7.

Supplemental Figure 12. DAP-seq analysis shows that AtNDX prefers to bind the promoter and terminal regions of genes that possess a high AT ratio. Supports Figure 8.

Supplemental Table 1. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table 2. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table 3. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table 4. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table 5. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table 6. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set. Gene expression analysis from RNA-seq. Supports Figure 5.

DIVE Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Acknowledgments