Abstract

An expandable polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent graft is beneficial for the treatment of coronary perforations. However, several reports have shown that restenosis and thrombotic occlusion occasionally occur in the stented segment after PTFE-covered stent implantation. A restenosis case after treatment with PTFE-covered stent against saphenous vein graft (SVG) perforation has never been evaluated with optical coherence tomography (OCT) or coronary angioscopy (CAS). This case report presents a 75-year-old man treated with a PTFE-covered stent after he suffered from SVG perforation 6 months ago. He was found to have a focal restenosis of the distal edge of the PTFE-covered stent and underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. OCT showed focal restenosis with homogeneous neointima and exposed struts in the middle and proximal part of the PTFE-covered stent. CAS showed white neointima with a smooth surface at the restenosis site and a sharp border against proximal exposed struts with characteristic links. This case study showed, for the first time in vivo and in a human, the neointimal characteristics of restenosis and uncovered stent struts in a PTFE-covered stent which had been implanted 6 months before. The delayed endothelialization was sustained until 12 months after implantation.

Keywords: percutaneous coronary intervention, polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent, case study, coronary angioscopy, optical coherence tomography, PCI, OCT

Coronary artery perforation is reported to be a rare complication in around 0.4% of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). 1 2 Coronary artery perforation is a critical complication associated with high mortality rates, ranging from 7 to 15.2%. 3 4 An expandable polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent graft (GraftMaster, Abbott Vascular Instruments, Abbott Park, IL) which consists of a PTFE layer sandwiched between two stainless steel stents. This stent design is beneficial for the treatment of coronary perforations and aneurysms and for complex ulcerated lesions with excellent immediate results. 5 However, several reports after PTFE-covered stent implantation have shown that restenosis and thrombotic occlusion occasionally occur in the stented segment. 6 7 Coronary angioscopy (CAS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) enable neointimal growth or endothelialization on the stent struts and ascertain the presence of thrombi. 8 9 A case report reported a restenosis at the proximal edge of a PTFE-covered stent graft due to thrombus formation and absence of endothelialization in the covered stent at 9-month follow-up. 10 However, a restenosis case after treatment with PTFE-covered stent against saphenous vein graft (SVG) perforation has never been evaluated with OCT or CAS. Here, we report a case of a restenosis of PTFE-covered stent in SVG visualized by OCT and CAS 6 months after the implantation.

Case Report

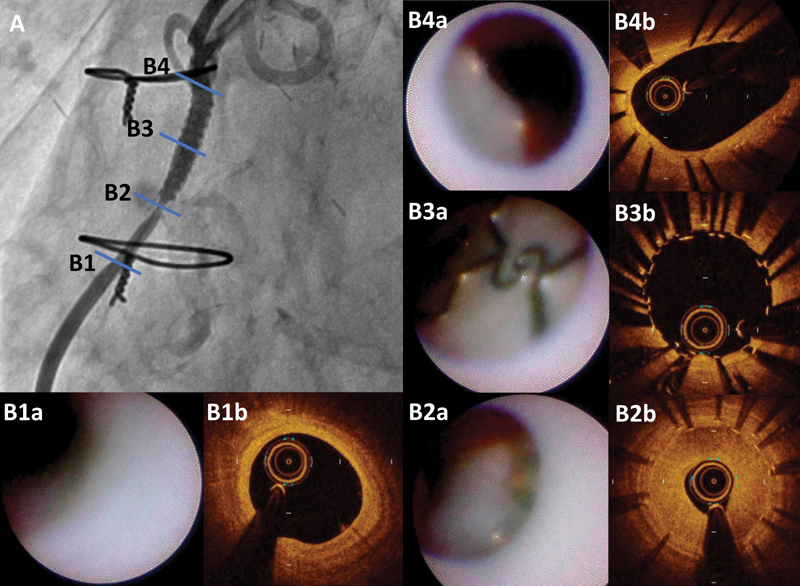

A 75-year-old man with a history of a coronary artery bypass graft with a saphenous vein for the right coronary artery for stable angina 8 months ago was referred for effort angina 6 months ago. He was found to have stenosis at the proximal part of the SVG, as detected by coronary angiography ( Fig. 1A ). He undergone PCI and implantation with a 3.5 × 18 mm everolimus-eluting stent (EES; Xience Alpine, Abbott Vascular Instruments, Abbott Park, IL) ( Fig. 1B ) and experienced coronary perforation ( Fig. 1C ). Since it was difficult to stop the bleeding using prolonged balloon inflation, a 3.5 × 19 mm PTFE-covered stent was implanted inside the EES and hemostat was achieved ( Fig. 1D ). The patient was discharged 2 days later and the chest pain disappeared. This time, however, he was referred for effort angina again and found to have a focal restenosis of the distal edge of the PTFE-covered stent, as detected by coronary angiography ( Fig. 2A ). After discussion, the patient opted to undergo PCI using OCT and CAS. We used a 7-F sheath (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) via the right femoral artery and engaged a 7-F Amplatz-left 1 guiding catheter (Mach 1, Boston Scientific, MA). OCT imaging was performed for the restenosis and overall proximal stent using the frequency-domain OCT system (C8-XRTM OCT Intravascular Imaging System; St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN). OCT showed extremely focal restenosis at the distal edge of the PTFE-covered stent with homogeneous neointima ( Fig. 2B2b ) and exposed struts in the middle and proximal part of the PTFE-covered stent ( Fig. 2B3b ), whereas a thin layer of endothelialization was visible in the most proximal EES part ( Fig. 2B4b ). CAS showed white neointima with a smooth surface at the restenosis site and a sharp border against the proximal exposed struts ( Fig. 2B2a ). The exposed struts with characteristic links in the middle and proximal part of the PTFE-covered stent were diffusely observed ( Fig. 2B3a ). The endothelialization grade was one in the EES part ( Fig. 2B4a ). Any atherosclerotic changes were not observed in distal SVG ( Fig. 2B1a, 1b ). Then, we delivered a 3.0 × 9 mm biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (BP-SES; Ultimaster, Terumo, Japan) into the lesion and obtained satisfactory expansion. Final OCT and CAS did not show any protrusion, malapposition, or underexpansion. The patient was discharged 2 days later without any complications and any symptoms. In 6 months, he experienced a relapse of angina and underwent PCI to the distal edge of BP-SES ( Fig. 3A ). OCT and CAS images revealed the stenosed BP-SES ( Fig. 3B1a, 1b ) and the persistently uncovered PTFE-covered stent ( Fig. 3B2a, 2b, 3 ). We dilated the stenosed lesion with a 3.0 × 20 mm paclitaxel-coated balloon (PCB; SeQuent Please, Nipro, Japan) and obtained satisfactory expansion.

Fig. 1.

Coronary angiogram shows tight stenosis in the proximal of the saphenous vein graft ( A ). A 3.5 × 18 mm everolimus-eluting stent (EES) is deployed ( B ). Coronary perforation after stent implantation ( C ). A 3.5 × 19 mm polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent is implanted inside the EES to achieve hemostat ( D ).

Fig. 2.

Coronary angiogram shows a focal restenosis of the distal edge of the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent ( A ) and indicates corresponding optical coherence tomography (OCT) and coronary angioscopy (CAS) images ( B1 – B4 ). OCT and CAS images show no atherosclerotic change in distal saphenous vein graft ( B1a , B1b ). OCT images show extremely focal restenosis at the distal edge of the PTFE-covered stent with homogeneous neointima ( B2a ), exposed struts in the middle and proximal part of the PTFE-covered stent ( B3a ), and a thin layer of endothelialization in the most proximal everolimus-eluting stent (EES) part ( B4a ). CAS images show a focal white neointima with smooth surface at restenosis site ( B2b ), exposed struts with characteristic links in the middle and proximal part of PTFE-covered stent ( B3b ), and grade 1 endothelialization in the EES part ( B4b ).

Fig. 3.

In 6 months, coronary angiogram shows a focal restenosis of the distal edge of biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (BP-SES) ( A ). Optical coherence tomography and coronary angioscopy images revealed stenosed BP-SES ( B1a , B1b ), uncovered proximal edge of BP-SES ( B2a , B2b ), and persistently uncovered polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent ( B3 ).

This patient with SVG stenosis experienced the restenosis of PTFE-covered stent and we delivered a BP-SES to the lesion to avoid repeat restenosis. However, restenosis occurred at the distal edge of BP-SES. Therefore, we decided to use PCB this time and to continue follow-up. A previous report has described the risk of repeat coronary artery rupture after repeat PCI. 11 To avoid repeat SVG rupture, we paid attention to avoid over-dilatation and we used 3.0 mm BP-SES and 3.0 mm PCB which were 0.5 mm smaller than the first EES. Then, we could avoid repeat SVG rupture.

Discussion

This case study with OCT and CAS imaging showed neointimal characteristics of restenosis and uncovered stent struts in a PTFE-covered stent which had been implanted 6 months before. The delayed endothelialization was sustained until 12 months after implantation.

Compared with treatment of native coronary artery, PCI of diseased SVG was associated with a higher incidence of restenosis. 12 The PTFE-covered stent for the treatment of diseased SVG resulted in worse clinical outcomes compared with bare-metal stent despite high-pressure implantation and prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy. 13 Previous CAS study reported delayed endothelialization and thrombus in PTFE-covered stent. 10 The present study also showed delayed endothelialization in the middle part of the PTFE-covered stent. OCT and CAS images did not show any thrombus and showed restenosis by neointimal proliferation in the distal edge of the PTFE-covered stent instead. The majority of restenoses of PTFE-covered stent is known to occur at the edges as compared with the center (23.8 vs. 8.8%). The mechanism of the restenosis has not been elucidated due to the lack of invasive imaging studies with OCT or CAS. As a case of edge-restenostic PTFE-covered stent, OCT and CAS revealed the mechanism of neointimal proliferation. The adhesion of the endothelium on PTFE vascular prostheses was reported to be impaired, 14 and therefore, the neointima may be thought to intrude into the PTFE-covered stent from outside of the distal edge.

Conclusion

OCT and CAS showed sharply bordered white neointima with smooth surface and uncovered stent struts in a PTFE-covered stent with restenosis.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ajluni S C, Glazier S, Blankenship L, O'Neill W W, Safian R D. Perforations after percutaneous coronary interventions: clinical, angiographic, and therapeutic observations. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;32(03):206–212. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruberg L, Pinnow E, Flood Ret al. Incidence, management, and outcome of coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention Am J Cardiol 20008606680–682., A8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Javaid A, Buch A N, Satler L F et al. Management and outcomes of coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(07):911–914. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimony A, Zahger D, Van Straten M et al. Incidence, risk factors, management and outcomes of coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(12):1674–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell P G, Hall J A, Harcombe A A, de Belder M A. The Jomed Covered Stent Graft for coronary artery aneurysms and acute perforation: a successful device which needs careful deployment and may not reduce restenosis. J Invasive Cardiol. 2000;12(05):272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gercken U, Lansky A J, Buellesfeld L et al. Results of the Jostent coronary stent graft implantation in various clinical settings: procedural and follow-up results. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56(03):353–360. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danenberg H D, Shauer A, Gilon D. Very late coronary stent graft thrombosis after aspirin cessation. Int J Cardiol. 2007;120(01):e15–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takano M, Ohba T, Inami S, Seimiya K, Sakai S, Mizuno K. Angioscopic differences in neointimal coverage and in persistence of thrombus between sirolimus-eluting stents and bare metal stents after a 6-month implantation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(18):2189–2195. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takano M, Yamamoto M, Inami S et al. Long-term follow-up evaluation after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation by optical coherence tomography: do uncovered struts persist? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(09):968–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takano M, Yamamoto M, Inami S et al. Delayed endothelialization after polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent implantation for coronary aneurysm. Circ J. 2009;73(01):190–193. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-07-0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veselka J, Tesar D, Honek T, Burkert J. Treatment of recurrent coronary rupture by implantation of three coronary stent-grafts. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent. 2003;5(02):88–91. doi: 10.1080/14628840310003299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keeley E C, Velez C A, O'Neill W W, Safian R D. Long-term clinical outcome and predictors of major adverse cardiac events after percutaneous interventions on saphenous vein grafts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(03):659–665. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone G W, Goldberg S, O'Shaughnessy C et al. 5-year follow-up of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents compared with bare-metal stents in aortocoronary saphenous vein grafts the randomized BARRICADE (barrier approach to restenosis: restrict intima to curtail adverse events) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(03):300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crombez M, Chevallier P, Gaudreault R C, Petitclerc E, Mantovani D, Laroche G. Improving arterial prosthesis neo-endothelialization: application of a proactive VEGF construct onto PTFE surfaces. Biomaterials. 2005;26(35):7402–7409. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]