Abstract

Objective:

Our goal was to identify pathogenic variants (PV) associated with germline cancer predisposition in an unselected cohort of older breast cancer survivors. Older patients with cancer may also be at higher risk for clonal hematopoiesis (CH) due to their age and chemotherapy exposure. Therefore, we also explored the prevalence of PVs suggestive of CH.

Methods:

We evaluated 44 older adults (65 years or older) diagnosed with breast cancer who survived at least two years after diagnosis from a prospective study, compared to healthy controls over the age of 65 (n=36). DNA extracted from blood samples and a multi-gene panel test was used to evaluate for common hereditary cancer predisposition and CH PVs. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare PV rates between groups.

Results:

Eight PVs in ATM, BRCA2 (x2), PALB2, RAD51D, BRIP1, and MUTYH (x2) were identified in 7 of 44 individuals with breast cancer (15.9%, 95% CI: 7–30%), whereas none were identified in healthy controls (p=0.01). Results remained statistically significant after removal of MUTYH carriers (p=0.045). PVs indicative of CH (ATM, NBN, and PPM1D [x2]) were identified in three of 27 individuals with breast cancer who received chemotherapy and in one healthy control.

Conclusion:

Moderate-risk and later disease onset high-risk hereditary cancer predisposition PVs were statistically significantly enriched in our survivorship cohort compared to controls. Because age- and chemotherapy-related CH are more frequent in this population, care must be taken to differentiate potential CH PVs from germline cancer predisposition PVs.

Keywords: older adults, BRCA1, BRCA2, genetic testing, hereditary cancer

Introduction

Recent data suggests that the overall rate of likely pathogenic and pathogenic variants (PV) associated with a germline predisposition to breast cancer is independent of age at the time of cancer diagnosis 1,2. Our group recently reported a 5.6% prevalence of breast cancer-associated PVs in 588 women diagnosed with breast cancer after the age of 65 1. In this population, PVs were most commonly found in BRCA2 and less penetrant genes such as CHEK2 1.

Germline genetic testing is performed on blood or saliva samples, which can also be used to detect PVs related to clonal hematopoiesis (CH). CH is typically suspected when the PV is represented at an allele fraction less than the 50% expected for heterozygosity 3. CH refers to the abnormal clonal expansion of blood cells in an individual 4. Among healthy people aged 70 years and older, 9.5–18.0% have been reported to carry CH PVs, compared to <2% among their younger counterparts 4,5. CH has been associated with the risk of developing primary or therapy-related leukemia, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and decreased overall survival 5.

Because the frequency of CH increases with both higher age and chemotherapy exposure, older adults with breast cancer may be at elevated risk of CH PVs. As it has been shown that CH may confound next-generation sequencing analysis for germline cancer predisposition, identifying and differentiating germline and CH-related PVs may be particularly critical in older patients with breast cancer 3.

Both hereditary cancer predisposition and CH may impact cancer survivorship, so recognition is important to guide patient management and reduce future disease morbidity. Identifying germline cancer predisposition is additionally important for cancer screening and precision prevention among family members, who often serve as caregivers for breast cancer survivors 6.

In this study, we assessed the prevalence of hereditary cancer predisposition PVs among older breast cancer survivors, and explored whether PVs suggestive of CH were more common among those with chemotherapy exposure compared with survivors without such exposure and among healthy controls.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment and Cohort Creation

This was a pilot study of patients recruited to the survivorship cohort of a larger prospective study of stage I–III patients with breast cancer who were aged 65 or over (City of Hope IRB 11127). Each of the 701 participants recruited to the main study belonged to one of three groups: those with breast cancer scheduled to start a new chemotherapy regimen (n=501), those with breast cancer not receiving chemotherapy (n=100), and healthy controls (n=100). Participants herein were selected at the end of 2017 and included those who had provided a blood sample and had re-consented to participate in the long-term survivorship portion of the study. In total, 80 participants met these criteria: 27 patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy, 17 patients with breast cancer without chemotherapy, and 36 healthy controls.

Genetic Analysis

DNA was extracted from whole blood and sequenced on an Illumina 2500 using a custom multiplex amplicon amplification panel covering exons of breast, ovarian, and colon cancer predisposition genes (QIAGEN, Redwood, CA). The 21 genes evaluated were APC, ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CDKN2A, CHEK2, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, MUTYH, NBN, NF1, PALB2, PMS2, PPM1D, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, and TP53.

Following American College of Medical Genetics/Genomics variant classification guidelines, PVs with allele fractions above 5% were used for germline and CH analyses 7. Ingenuity Variant Analysis version 5.1.20171127 (QIAGEN, Redwood, CA) was used for variant annotation, with a manual review of PVs by a board-certified molecular geneticist (T.P.S.). In brief, variants were excluded if observed with a population allele frequency greater than or equal to 2% in common population databases (e.g., from http://gnomad-old.broadinstitute.org/). Average sequencing read depth was 1000X. Heterozygous PVs were presumed germline if their allele fractions were over 40% and considered likely indicative of CH if their allele fractions were between 5% and 20%. Secondary orthogonal sequencing methods were used to help categorize PVs between allele fractions of 20–40%.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the participants’ demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics. The rates of PVs were calculated and compared between patients with breast cancer and healthy controls using Fisher’s exact test. All statistical tests were two‐sided, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Due to the exploratory nature of this analysis, p-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 analytic software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Cohort demographics

We assessed blood samples from 44 breast cancer survivors (of these, 27 had prior chemotherapy exposure) and 36 cancer-free controls (Table 1). The mean age at diagnosis for patients with breast cancer was 71.7 (standard deviation [SD]=5.3, median=71, range 65–86). Their mean age at blood draw was 74.6 (SD=5.3, median=74, range 68–89). The majority of cases had early-stage (0-ll) cancer (93.2%). One male with breast cancer was included in the cohort. Cases were largely non-Hispanic white (77.3%). The most common breast cancer phenotype was estrogen receptor-positive/progesterone receptor-positive/Her2 amplification-negative (ER+/PR+/Her2−).

Table 1.

Participant demographics and disease and treatment characteristics of patients with breast cancer.

| Patients with Breast cancer (n=44) | Healthy controls (N=36) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at blood drawn | ||

| Mean (SD) | 74.6 (5.29) | 72.4 (6.40) |

| Median (range) | 74 (68–89) | 70 (67–93) |

| Gender (N[%]) | ||

| Female | 43 (97.7%) | 36 (100%) |

| Male | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Race/ethnicity (N[%]) | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 34 (77.3%) | 25 (69.4%) |

| Black | 3 (6.8%) | 4 (11.1%) |

| Asian | 4 (9.1%) | 1 (2.8%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4.5%) | 6 (16.7%) |

| Other | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| For patients with breast cancer only | ||

| Age at breast cancer diagnosis | ||

| Mean (SD) | 71.7 (5.30) | |

| Median (range) | 71 (65–86) | |

| Chemotherapy (N[%]) | ||

| Yes | 27 (61.4%) | |

| No | 17 (38.6%) | |

| Stage (N[%]) | ||

| I | 20 (45.5%) | |

| II | 21 (47.7%) | |

| III | 3 (6.8%) | |

| Her2/ER/PR status(N[%]) | ||

| Triple-negative | 3 (6.8%) | |

| Her2-negative | ||

| ER−/PR+ | 1 (2.3%) | |

| ER+/PR− | 3 (6.8%) | |

| ER+/PR+ | 29 (65.9%) | |

| Her2-positive | ||

| ER−/PR− | 1 (2.3%) | |

| ER+/PR− | 4 (9.1%) | |

| ER+/PR+ | 3 (6.8%) | |

The mean age of healthy controls (n =36) at blood draw was 72.4 (SD=6.40, median=70, range 67–93). All controls were female and largely non-Hispanic white (69.4%), with no reported history of cancer. Overall, there were no significant differences between patients with breast cancer and healthy controls in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, and cancer comorbidity (exact p values>0.2). However, the healthy controls were younger at blood draw (p=0.01).

Identified hereditary predisposition PVs

Among the 44 patients with breast cancer, seven (15.9%, 95% CI 7–30%) had at least one germline cancer predisposition PV (in ATM, BRCA2 [x2], PALB2, RAD51D, BRIP1, and/or MUTYH [x2]), whereas none (95% CI 0–10%) of the healthy controls had PVs in these genes (exact p=0.01). One male with breast cancer had two PVs, one in ATM and one in BRCA2. Two individuals had single, unique PVs in MUTYH, both of which predispose carriers to colon cancer when inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion (an individual must have one PV on both alleles). Therefore, the finding of a single MUTYH allele alone is not thought to contribute substantially to cancer risk. However, even after removal of MUTYH from the above analysis, our results remained statistically significant with five (11.4%, 95% CI 4–25%) individuals having at least one germline cancer predisposition PV compared to none in the healthy controls (exact p=0.045). All PVs were previously catalogued in the hereditary cancer database ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Germline pathogenic variants identified in the survivorship cohort

| Pt | Gene symbol | Transcript ID | Transcript variant | Protein variant | Translation impact | NGS VAF | NGS read depth | ClinVar ID(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1** | ATM | NM_000051.3 | c.7951C>T | p.Q2651* | stop gain | 23.59^ | 301 | RCV000130403; RCV000411562 |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.3 | c.1642C>T | p.Q548* | stop gain | 51.23 | 486 | RCV000077662.4; RCV000130404.3 |

|

| 2 | BRCA2 | NM_000059.3 | c.6393_6396delATTA | p.K2131fs*5 | frameshift | 34.59^ | 133 | RCV000044930.2; RCV000166186.1; RCV000211011.2; RCV000478975.1 |

| 3 | BRIP1 | NM_032043.2 | c.2392C>T | p.R798* | stop gain | 49.72 | 362 | RCV000394625.1; RCV000212324.3; RCV000005004.3; RCV000409918.1; RCV000312325.1; RCV000504276.1; RCV000205436.3; RCV000116139.8 |

| 4 | MUTYH | NM_001128425.1 | c.1147delC | p.A385fs*23 | frameshift | 48.12 | 399 | RCV000235584.2; RCV000196379.5; RCV000164291.4; RCV000144632.1; RCV000121593.1 |

| 5 | MUTYH | NM_001128425.1 | c.934-2A>G | N/A | splice site error | 50.79 | 254 | RCV000034683.8; RCV000122431.1; RCV000129053.8; RCV000212712.3 |

| 6 | PALB2 | NM_024675.3 | c.3549C>G | p.Y1183* | stop gain | 50.1 | 497 | RCV000114634.6; RCV000001304.2; RCV000001305.2; RCV000114635.1; RCV000212830.2; RCV000129158.7; RCV000121742.1 |

| 7 | RAD51D | NM_002878.3 | c.81delA | p.V28fs*12 | frameshift | 40.79 | 152 | RCV000485671.1 |

Participant (Pt) 1 was identified to have two pathogenic variants. Next generation sequencing (NGS) variant allele fraction (VAF).

Orthogonally validated through commercial testing and identified as germline origin.

Laboratory re-sequencing (completed commercially) was performed to help classify PVs with allele fractions between 20% and 40% (n=2; ATM p.Q251* at 23.59% and BRCA2 p.K2131fs*5 at 34.59%). Both were considered germline PVs after laboratory analysis.

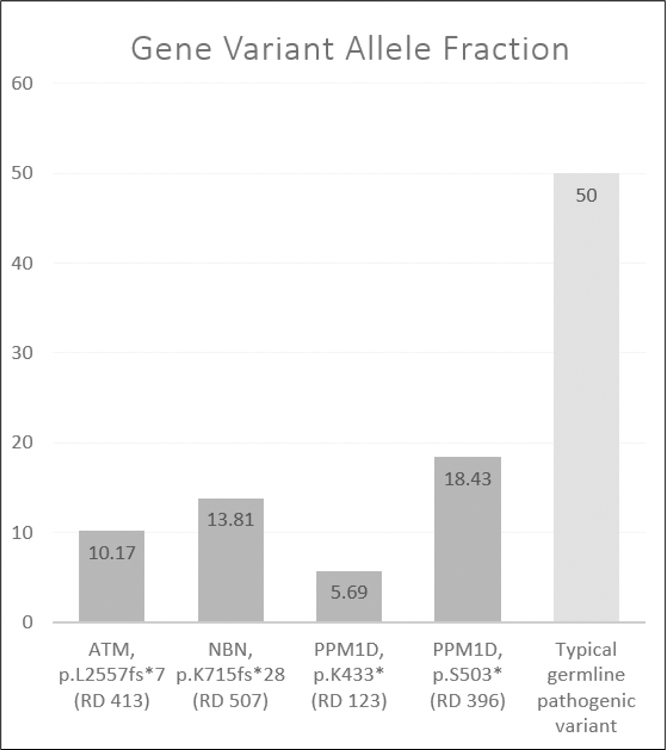

PVs associated with probable clonal hematopoiesis

Among the 44 patients with breast cancer, three had PVs likely representative of CH (Figure 1), with allele fractions ranging from 5.69% to 18.43%. Among these PVs, all were identified in patients who received chemotherapy, and none were identified in patients who did not. For the individuals with likely CH PVs, blood was drawn 18–34 months after the end of chemotherapy. Among the 36 healthy controls, one had a CH PV in ATM; this healthy control was 85 years of age at the time of blood draw. Though distributed as hypothesized, the prevalence of CH PVs was not statistically different across the three groups 1) 11.11% (95% CI 2–29% in patients with breast cancer who received chemotherapy, 2) 0% (95% CI 0–20%) in patients with breast cancer who did not receive chemotherapy, and 3) 2.8% (95%CI 0–15%) in healthy controls, p=0.26. Complete blood counts were available for two of four of the individuals with likely CH and showed no signs of hematologic disease. One of the four cases reported atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. No cases reported leukemia or metastatic disease. All individuals remain alive 20–49 months after blood sample collection.

Fig. 1.

Allele fractions of the gene variants identified in this study that are likely representative of clonal hematopoiesis, presented in comparison to a typical germline pathogenic variant. Sequencing locus read depth (RD) is provided in parentheses under each respective variant.

Discussion

Recent literature has shown that older adults with cancer may have germline cancer predisposition 1,2. Older adults may also be at higher risk for CH due to their age and chemotherapy exposure 4,5. In our unselected cohort of older breast cancer survivors, we identified both actionable germline cancer predisposition PVs and PVs suggestive of CH.

Our study supports a recent recommendation by The American Society of Breast Surgeons to make genetic testing available to all patients with a personal breast cancer history, regardless of age 8: a recommendation not currently agreed upon by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline committee 9. Regarding our findings, our prior study knowledge did not suggest anything particularly unique about our unselected breast cancer survivorship cohort that would have led to an increased prevalence of germline cancer predisposition PVs. Not surprisingly, PVs in high-risk breast cancer genes such as BRCA1 or TP53 were not identified among this older breast cancer cohort. Rather, one PALB2 and two BRCA2 PVs were identified in our cohort. Although these are relatively high-risk breast cancer genes, they are often associated with later onset disease 1.

The findings of this study are significant because they particularly underscore the importance of identifying hereditary cancer predisposition among older adults with cancer. Once identified, this information can be leveraged to improve the delivery of risk-appropriate care for breast cancer survivors. For instance, identification of germline BRCA2 and PALB2 PVs would allow for consideration of poly-ADP ribose inhibitor therapy for those with metastatic breast cancer 10. BRCA2, PALB2, and ATM (a moderate-risk breast cancer predisposition gene 1) PV carriers with limited-stage breast cancers may also benefit from high-risk surveillance for new primary breast cancers 9. As fallopian tube and ovarian cancers are often diseases of advanced age, BRCA2, BRIP1 and RAD51D PV carriers of any age (assuming they have a treatable primary cancer and they can tolerate the procedure) may benefit from risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 9. Furthermore, once an actionable cancer hereditary predisposition PV is identified in the patient, cascade testing can be completed in the family to enable risk appropriate surveillance and precision prevention for family members 9,11. For instance, specifically regarding MUTYH, even though a single MUTYH PV would not change care for a breast cancer survivor, cascade testing and/or evaluation of family members for signs of MUTYH-associated polyposis would be recommended 11.

Even though the prevalence of likely CH PVs was not statistically significant across the three participant groups, their identification remains intriguing. As shown in our cohort, several genes associated with CH (e.g., ATM) are also common cancer predisposition genes. As expected, CH was only identified in patients with breast cancer with prior chemotherapy. The only individual with findings of CH who did not receive chemotherapy was a healthy individual at high risk for CH based on age alone (85 years) 4. Given the a priori presumed high prevalence of CH among older individuals, and the consequent difficulty classifying variants between 20–40% allele fraction, orthogonal validation for PVs in this range was completed and confirmed two cases representing germline PVs rather than CH. The PVs in our study with allele fractions between 5–20% most likely represent CH, as variants with allele fractions in this range are unlikely to be germline and other confounding factors were unlikely. There was no leukemia or metastatic disease reported to suggest that the PVs represented circulating tumor DNA, the PVs were unlikely to be due to germline mosaicism, and the next-generation sequencing read depth and allele fractions of the PVs did not suggest sequencing error or false-positive findings 3.

The small cohort size in this study is its primary limitation. Complete family history information was also lacking to further stratify hereditary cancer predisposition risk. To evaluate whether a larger sample size would have strengthened our CH findings, bootstrap analysis was completed. At a theoretical total sample size of 400 patients, CH would have been significantly associated with chemotherapy exposure (p=0.02). Additionally, our study lacks evaluation of some of the more common CH genes, such as DMNT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 4. Currently, no firm recommendations can be made to test for CH PVs in this population given the unclear clinical utility. Nonetheless, we showed that CH can be identified and discriminated from germline PVs, and we hope that our results will serve as a nidus for larger survivorship studies, which will be necessary both to detail the spectrum of CH and to understand its meaning.

Conclusion

Our findings support that there is an increased frequency of moderate-risk and later disease onset high-risk hereditary cancer predisposition PVs among older breast cancer survivors compared to healthy controls. Care must be taken to differentiate germline cancer predisposition variants from age- or chemotherapy-related CH. Further research is warranted to identify the role and value of these tests into clinical practice and survivorship studies.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers P30CA33572 (Integrative Genomics Core), R01AG037037 (PI: Hurria), and K08CA234394 (PI: T. Slavin). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Other sources of support include: the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (PI: J. Weitzel; PI: A. Hurria) and the Dr. Norman & Melinda Payson Professorship in Medical Oncology (J. Weitzel). We wish to thank the participants who enabled this research to be completed. We would also like to thank research coordinator Kevin Karwing Tsang and scientific editor Kerin Higa.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chavarri-Guerra Y, Hendricks CB, Brown S, et al. The burden of breast cancer predisposition variants across the age spectrum among 10,000 patients. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(5):884–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tung N, Lin NU, Kidd J, et al. Frequency of Germline Mutations in 25 Cancer Susceptibility Genes in a Sequential Series of Patients With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1460–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weitzel JN, Chao EC, Nehoray B, et al. Somatic TP53 variants frequently confound germ-line testing results. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2018;20(8):809–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(26):2488–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman RL, Busque L, Levine RL. Clonal Hematopoiesis and Evolution to Hematopoietic Malignancies. Cell stem cell. 2018;22(2):157–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rebbeck TR, Burns-White K, Chan AT, et al. Precision Prevention and Early Detection of Cancer: Fundamental Principles. Cancer discovery. 2018;8(7):803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2015;17(5):405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manahan ER, Kuerer HM, Sebastian M, et al. Consensus Guidelines on Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer from the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Version 3.2019 Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2019;Version 3.2019. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- 10.Somlo G, Frankel PH, Arun BK, et al. Efficacy of the PARP Inhibitor Veliparib with Carboplatin or as a Single Agent in Patients with Germline BRCA1- or BRCA2-Associated Metastatic Breast Cancer: California Cancer Consortium Trial . Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(15):4066–4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NCCN. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology V.1.2017: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2017;12017. [Google Scholar]