Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death, accounting for more than 155,000 deaths each year.1 Most patients with lung cancer are diagnosed at advanced stages.2 Because lung cancer has poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of 18%,3 curative treatment options are limited. Lung cancer also leads to severe symptoms and is a source of considerable morbidity among the elderly.4 Thus, improving patients’ quality of end-of-life and preventing unnecessary invasive care is of utmost importance and hospice plays an essential role as a treatment modality among these patients.

Several studies find that hospice improves quality-of-life among cancer patients and satisfaction with hospice is often higher than conventional care (CC).5,6 On the other hand, findings regarding savings associated with hospice use have been somewhat mixed. While some studies find savings associated with hospice use,5,7–10 others find costs to be similar11 or even higher among hospice users than CC patients.12,13 An important caveat is that most studies that examine savings associated with hospice use include all hospice users with varied conditions in their study sample8,9 or group all cancer patients under a single category.7 However, hospice care for cancers with particularly high symptom burden and treatment cost may be the most likely to generate significant savings. Knowing these cancers may help providers target hospice to specific types of cancer, thereby substantially increasing savings and decreasing financial burden to patients and their families.

One study that examined the impact of hospice on healthcare costs among head and neck cancers, which are a source of considerable morbidity and mortality, found higher savings than other studies that combined all cancer types in their study sample.10 Another study of hospice care concluded that savings were higher among Medicare enrollees with very aggressive cancers (median survival < 1 year) compared to other conditions.11 Hence, lung cancer, which has very low survival rates3 and leads to the use of expensive services,14 could generate considerable savings from hospice use.

Studies that look at the mechanism by which hospice leads to cost savings have also been limited. Some studies have found lower hospitalizations,9,15 and emergency department (ED)9,15 and Intensive care unit (ICU)9,15 visits as likely contributors to cost-savings. However, chemotherapy15 and radiation therapy sessions, which contribute significantly towards end-of-life costs among cancer patients, have been often overlooked. In fact, chemotherapy and radiation therapy sessions make larger contributions to end-of-life outpatient service costs among cancer patients than ED visits.16

The objective of our study is to compare monthly spending on services used in the last 6 months of life by lung cancer decedents that used hospice versus those that used CC. Unlike most studies which lump all end-of-life spending into a single variable, our study, like the study by Enomoto et al. (2015), looks at month-by-month spending to better understand the mechanism by which hospice might impact end-of-life costs. We also compare month-by-month utilization patterns including hospitalizations, and use of select outpatient services such as ED visits, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy between hospice users and non-users during the 6-month period. Our analysis of utilization metrics (including measures that have been overlooked by prior studies, such as radiation therapy) provide a better understanding of the drivers of spending differences between hospice users and non-users.

Methods

Sample

The claims and demographic information for a 10% random sample of Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries with cancer between 2009–2013 was provided to us by Medicare. To select this sample, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) first identified all patients with cancer from 100% of Medicare claims using the standard algorithm used for creating cancer indicators in the Medicare Chronic Condition Warehouse (CCW) files, and then provided us a 10% random sample. From the sample, we identified beneficiaries that had lung cancer and died between 2010 and 2013.

We included only beneficiaries that were continuously enrolled in both Medicare Part A and B for at least 6 months before death to ensure complete utilization and spending information for the sample. We removed any beneficiaries that were enrolled in Medicare Advantage (MA). These exclusions resulted in a sample of 43,789 individuals.

The sample was then divided into 2 groups - “hospice users” and “hospice non-users” depending on whether they had any hospice claims in last 6 months of life.

Data

The primary data sources are the following 2009–2013 claims files: Medicare Hospice files, which contain final action claims submitted by hospice providers; Part A Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file containing inpatient hospital and skilled nursing facility (SNF) claims; Part B files including the Medicare Hospital Outpatient file, which includes records for services provided in hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) and the Carrier file, which has claims for services by non-institutional providers; and Durable Medical Equipment (DME) file containing claims submitted by DME suppliers. Data from 2009 data was used to ensure that we have the complete 6-month resource utilization information for beneficiaries that died in early 2010.

The Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary Files (MBSF) were used to obtain beneficiaries’ demographic characteristics and disease indicators including cancer type. The American Community Survey (ACS) data supplied ZIP-level income, education, and unemployment rates. Information regarding the number of hospice providers serving the beneficiary ZIP were obtained using the Hospice Compare files. Since these files were made available only starting in 2017 on Medicare.gov, we used the 2017 Hospice Compare files to identify zip codes served and the hospice certification date to determine whether they were in operation during the 2009–2013 study period.

Outcomes

We included spending and utilization outcomes for each month in the 6-month period prior to death. While some studies of end-of-life use last year of life as the time period to analyze utilization, we use six months because hospice eligibility requires that a beneficiary has a life expectancy of six months or less. Spending measures include total monthly spending on all-cause inpatient stays, SNF stays, OP procedures and drugs, ED visits, physician services, DME, and hospice care. We defined spending as the Medicare allowed payment, which includes patient out-of-pocket spending and Medicare reimbursements. Since we use data from 4 years, we accounted for inflation by adjusting all spending to 2013 dollars.17 Costs for inpatient stays were inflated using the hospital and related component of the consumer price index (CPI), costs for DME were inflated based on the medical care commodities component, and all other costs were inflated based on medical care services component of CPI.

We included four monthly utilization outcomes: 1) indicator of any hospitalization, 2) indicator of any ED visit, 3) number of Part B chemotherapy claims, and 4) number of radiation therapy sessions.

Statistical Approach

We first descriptively compared the covariates and outcomes between hospice users and non-users and checked whether the sample was balanced on all observable covariates. Selection bias is a common issue when studying cost savings associated with hospice use. It is possible that patients who choose hospice care do so to avoid aggressive end-of-life care and are inherently different from patients who do not – i.e., there are observable or unobservable characteristics that influence hospice use. Thus, we used propensity score matching, followed by regression analysis using the matched sample to compare the outcomes.

To create a matched sample, we first used logistic regression to estimate the propensity score of hospice enrollment using the following covariates: age at diagnosis, gender, race, time since diagnosis, chronic condition indicators such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and others available in the MBSF file, zip-level income, education, and unemployment rates, and number of hospice providers serving the zip code. These covariates are mostly consistent with those in prior studies.8,10 However, while prior studies used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) data and had stage information, this information is not available to us. Hence, we attempt to address this issue by controlling for an indicator of metastasis using the criterion of ≥ 2 diagnosis codes of metastatic disease (ICD-9-CM 196–199), separated by 30 days or more.18,19

Next, we matched hospice enrollees to non-hospice controls within 2% of the standard deviation of the propensity scores. All unmatched subjects were excluded. Once the matched cohorts were created, we compared patient characteristics using the matched samples to check whether matching resulted in a more balanced cohort.

With the matched sample, we estimated spending using generalized linear models (GLM) with log-link and gamma distribution.20 For outcomes of any hospitalization and ED visit, we fit logistic regression models, while for other utilization measures (counts), we estimated negative binomial models. We included the same set of covariates in the regression analysis as matching. For each outcome, we computed predicted values among hospice users and non-users after setting all other covariates to their mean values. Since patients within the same zip code share similar zip code-level characteristics such as health care resources or provider practice patterns, all standard errors were clustered by zip code to account for those similarities.

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted two sensitivity analysis. First, we estimated spending measures using GLM with log-link and gamma distribution using the full sample (i.e. including all individuals who met the inclusion criteria), and computed the predicted values to see how they compare to the results from our primary analysis. Next, we conducted a sub-group analysis to determine whether spending differences varied by length of hospice enrollment. We divided hospice enrollees into three categories based on different enrollment periods – a) beneficiaries that began using hospice < 7 days before death, b) beneficiaries that began using hospice between 7–30 days before death, and c) beneficiaries that began using hospice between 30–60 days before death. Each sub-groups of enrollees were matched to non-users and we re-estimated the GLM spending models. The spending differences were then obtained as difference in the adjusted means by month between hospice users and non-users.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics for hospice users and non-users in both the full and propensity score matched samples. Of the 43,789 beneficiaries in the full sample, 27,198 (66.7%) used hospice in the last 6 months before death. Patients that used hospice were more likely to be older, female, white, and have metastatic cancer. However, they were less likely to suffer from other chronic conditions. The average length of stay in hospice was 31 days, but the median was only 13 days. In addition, Table 1 also indicates patient characteristics for each group, after creating the matched sample. Matching resulted in a cohort that was better balanced on the covariates.

Table 1.

Descriptive comparison of sample characteristics

| Unmatched Samplea | Matched Sampleb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospice Users | Hospice Non-users | Std. diffc | Hospice Users | Hospice Non-users | Std. diffc | |

| N=27,197 | N= 16,592 | N=16,481 | N= 16,481 | |||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age group 65–70 | 15% | 16% | −0.04 | 16% | 16% | −0.01 |

| Age group 70–75 | 20% | 20% | −0.02 | 20% | 20% | <−0.01 |

| Age group 75+ | 58% | 54% | 0.08 | 55% | 55% | 0.02 |

| Female | 49% | 43% | 0.12 | 44% | 43% | 0.02 |

| White | 90% | 86% | 0.09 | 87% | 87% | 0.02 |

| Conditions | ||||||

| Diabetes | 33% | 36% | −0.07 | 36% | 36% | −0.01 |

| Hypertension | 71% | 76% | −0.12 | 76% | 76% | −0.01 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 53% | 60% | −0.14 | 58% | 60% | −0.03 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 44% | 47% | −0.06 | 47% | 47% | <0.01 |

| Depression | 26% | 24% | 0.03 | 25% | 24% | 0.02 |

| Heart failure | 37% | 48% | −0.23 | 45% | 48% | −0.05 |

| Cataract | 9% | 9% | −0.01 | 9% | 9% | <0.01 |

| COPDd | 59% | 67% | −0.18 | 66% | 67% | −0.03 |

| Other cancers: | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 6% | 6% | 0.03 | 6% | 6% | <0.01 |

| Prostate cancer | 6% | 6% | −0.01 | 6% | 6% | <−0.01 |

| Colon cancer | 5% | 5% | −0.01 | 5% | 5% | <0.01 |

| Cancer metastasis | 38% | 28% | 0.21 | 31% | 28% | 0.05 |

| Number of chronic conditions (N) | 5.6 | 6.2 | −0.23 | 6.1 | 6.2 | −0.04 |

| Time from diagnosis to death (in days) | 566 | 669 | −0.10 | 629 | 661 | −0.03 |

| Market characteristics | ||||||

| Median Household Income ($) | 54403 | 53509 | 0.04 | 53697 | 53531 | 0.01 |

| Percent College Educated over 65 (%) | 20 | 19 | 0.07 | 19 | 19 | 0.02 |

| Percent Unemployed (%) | 9 | 9 | −0.03 | 9 | 9 | <−0.01 |

| Number of hospices serving the ZIP (N) | 11 | 11 | 0.03 | 11 | 11 | <0.01 |

Note:

Unmatched sample refers to the sample of lung cancer patients that died between January 2010 to December 2013 and had complete cost information for the 6-month period before death;

Matched sample refers to sample created by matching patients that used hospice to patients that did not use hospice based on propensity scores;

Standardized difference between the two groups;

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

Spending measures

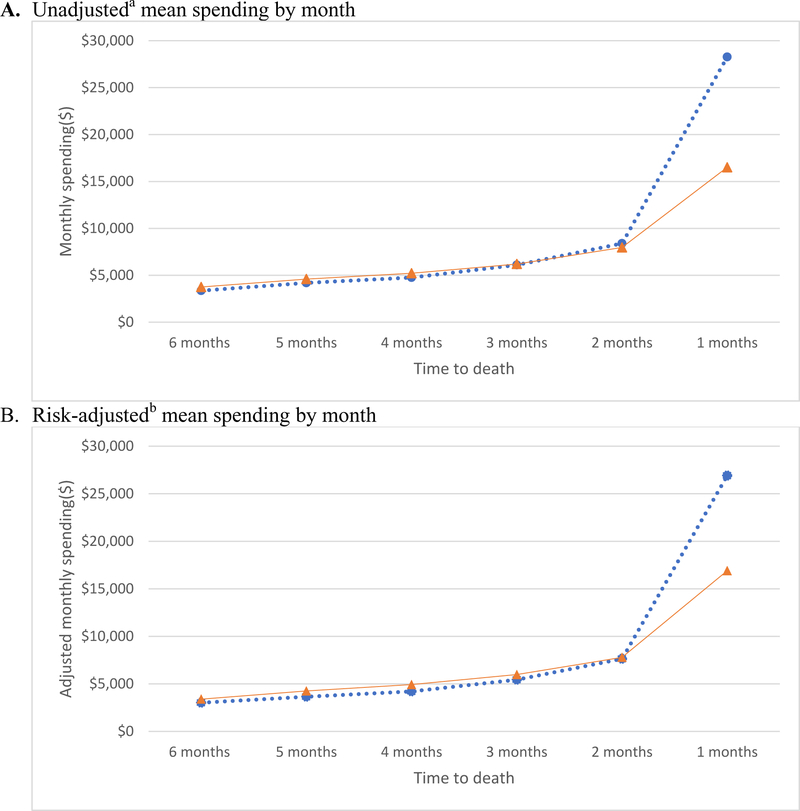

Figure 1 compares month by month mean spending between lung cancer patients that used hospice versus those that did not. Figure 1a presents comparison of unadjusted mean spending by month between hospice users and non-users in the full samples. In general, mean spending increased steadily from 6 months before death to 2 months before death. Hospice users had slightly higher spending than non-users during this period. However, in the final month of life, spending among non-users was around $28,280 per Medicare beneficiary compared to spending of $16,510 among hospice users (p<0.01).

Figure1.

Comparison of mean spending by month in the last 6 months of life between lung cancer patients that used hospice versus those that did not use hospice

Notes:

a Unadjusted spending by month for the unmatched sample.

b Using the matched sample, spending was adjusted for patient and market characteristics for each monthly measure using GLM model with log link and gamma distribution. Standard errors accounted for clustering within a ZIP. Value are predicted values among hospice users and non-users after setting all the other covariates to their mean values;  Hospice users;

Hospice users;  Hospice non-users;

Hospice non-users;

Figure 1b presents the adjusted mean spending by month in the last 6 months before death between hospice users and non-users in the propensity-score matched sample. As shown in Figure 1b, after matching hospice users to non-users using propensity score matching and running regression analysis, Medicare lung cancer decedents that received hospice care had spending of $16,907 in the final month of life compared to non-users who had spending of $26,906– a difference of nearly $10,000 (p<0.01). Figures 1a and 1b indicate that patterns of both unadjusted and adjusted spending by month are similar.

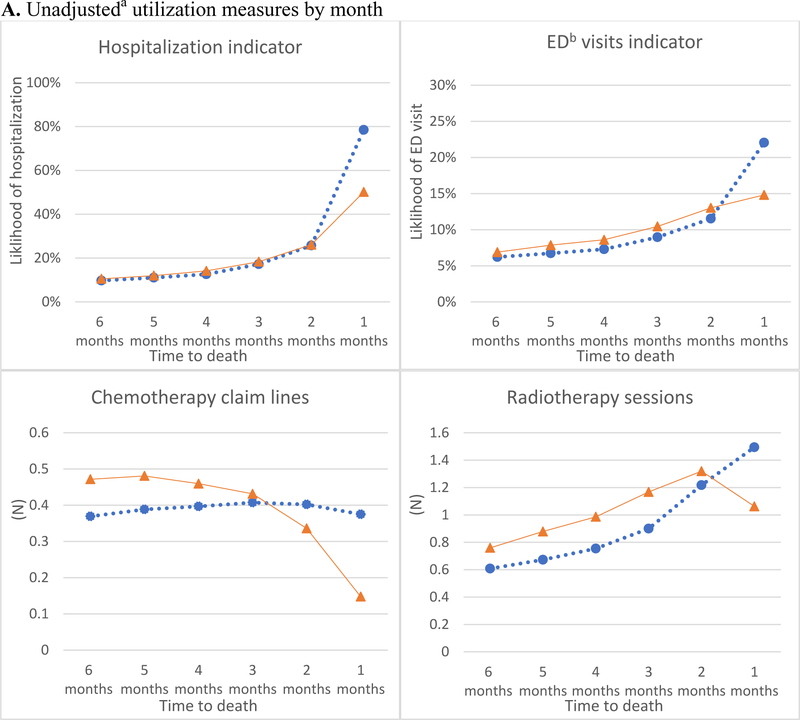

Utilization measures

Figure 2 compares month by month utilization rates in the last 6 months of life for hospice and non-users. Figure 2a presents a comparison of unadjusted utilization rates in the full sample. The descriptive trends in utilization suggest that the likelihood of any hospitalization and any ED visit increased gradually from 6 months before death to 2 months before death, followed by a larger increase in the last 2 months. The increase in the likelihood of any hospitalization and ED visit in the last month was less steep among hospice users than non-users - similar to the trends in spending. The trends in number of chemotherapy and radiation therapy sessions followed a different pattern than hospitalizations and ED visits. For both hospice users and non-users, the number of chemotherapy sessions per month increased gradually 6 months to 3 months before death. In the last 2 months, while number of chemotherapy sessions per month fell sharply among hospice users, among non-users the number of sessions remained nearly the same as the number of visits in the prior 4 months. In terms of the number of radiation therapy sessions, non-users experienced a steady increase in the last six months of life with a substantial increase in the number of sessions in the last month. On the other hand, hospice users experienced a gradual increase in the number of radiation therapy sessions until the final month prior to death, when the number of radiation sessions decreased substantially.

Figure 2.

Comparison of utilization of select services by month in the last 6 months of life between lung cancer patients that used hospice versus those that did not use hospice

Notes:

a Unadjusted utilization by month for the unmatched sample.;

b Emergency department;

c Using the matched sample, utilization was adjusted for patient and market characteristics for each monthly measure. Standard errors accounted for clustering within a ZIP. Value are predicted values among hospice users and non-users after setting all the other covariates to their mean values;  Hospice users;

Hospice users;  Hospice non-users;

Hospice non-users;

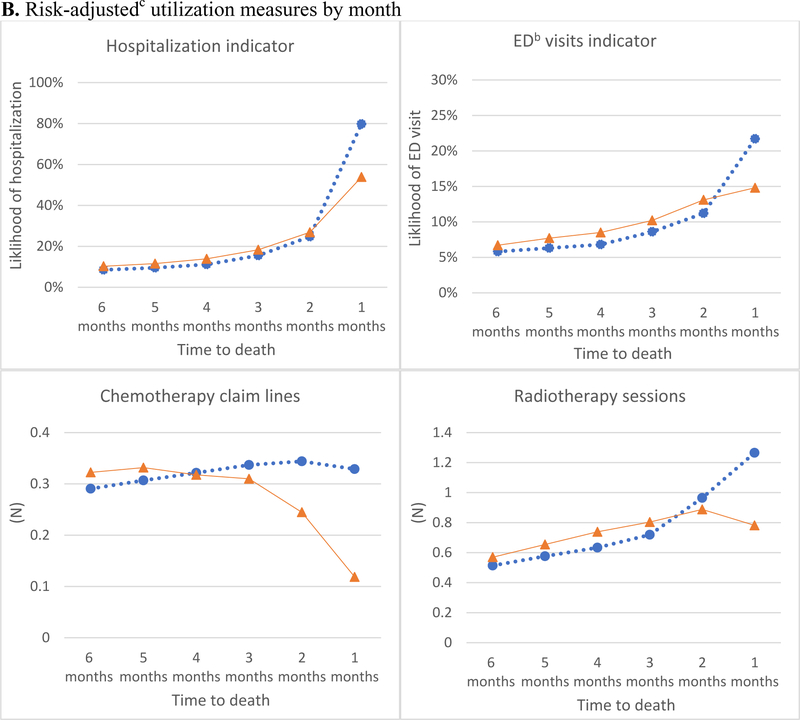

Figure 2b presents regression-adjusted month by month utilization using the propensity score matched sample. In the last month of life non-users had a significantly higher likelihood of a hospitalization (80% versus 54%, p<0.01), higher likelihood of an ED visit (22% versus 15%, p<0.01), greater number chemotherapy (0.32 versus 0.12, p<0.01), and radiation therapy sessions (1.26 versus 0.80, p<0.01) than hospice users.

Sensitivity analysis

Table 2 shows results of the sensitivity analyses. The results from the regression analysis using the full sample are consistent with the primary analysis.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis

| Time-to-death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Type | 6 months | 5 months | 4 months | 3 months | 2 months | 1 months |

| Regression analysis using full sample | ||||||

| Risk-adjusteda monthly spending difference between hospice users and non-users | $356.68 | $560.6 | $667.57 | $441.16 | $169.28 | $(9591) |

| P-Values | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Different hospice enrollment period | ||||||

| Enrolled < 7 days before death | ||||||

| Risk-adjustedb monthly spending difference between hospice users and non-users | $44 | $(9) | $(40) | $(611) | $(494) | $(3816) |

| P-Values | 0.66 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Enrolled ≥ 7 days and <30 days before death | ||||||

| Risk-adjustedb monthly spending difference between hospice users and non-users | $403 | $285 | $328 | $178 | $204 | $(9482) |

| P-Values | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.00 |

| Enrolled ≥30 days & <60 days before death | ||||||

| Risk-adjustedb monthly spending difference between hospice users and non-users | $546 | $832 | $707 | $1723 | $520 | $(15,689) |

| P-Values | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Notes:

Using the full sample of lung cancer patients, spending was adjusted for patient and market characteristics for each monthly measure using GLM model with log link and gamma distribution. Standard errors accounted for clustering within a ZIP. Value are difference in predicted values among hospice users and non-users after setting all the other covariates to their mean values;

Each sub-group of hospice-enrollees were matched to non-users using propensity score matching. Using the matched sample, spending was adjusted for patient and market characteristics for each monthly measure using GLM model with log link and gamma distribution. Standard errors accounted for clustering within a ZIP. Value are difference in predicted values among hospice users and non-users after setting all the other covariates to their mean values;

The results from our sub-group analysis reveal that hospice enrollment led to savings in the last month of life irrespective of whether the patient enrolled in hospice for < 7 days, 7–30 days, or 30–60 days. However, the amount of savings varied by length of hospice stay. Patients who enrolled in hospice for < 7 days before death had $3816 lower spending in the last month of life compared to non-users (p<0.01). However, those that enrolled for longer durations had larger savings in the last month of life - $9482 lower spending among those enrolled for 7–30 days compared to non-users(p<0.01), and $15,689 lower spending among those enrolled for 30–60 days (p<0.01) compared to non-users.

Discussion

We examined the impact of hospice on Medicare spending and found that beneficiaries with lung cancer using hospice had lower spending in the last 6 months of life compared to non-users. Most of the savings came in the last month of life - the time when most beneficiaries began enrolling in hospice (mean length of stay was 31 days). Several studies have found that hospice reduces end-of-life costs among cancer patients. Using a sample of lung cancer patients, we find greater savings in the last month of life compared to prior studies. For example, a prior study that looked at monthly cost trends among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with head and neck cancers found savings of $7000-$7400 in the last month10 – as compared to our estimates of around $10,000 savings for lung cancer patients. Our findings could be attributable to higher morbidity among lung cancer patients,4 and the fact that these patients generally use more expensive services than patients with other cancer types.14 Our study confirms findings from other studies that have looked at other aggressive cancers,10,13 including lung cancer,13 and found cost savings associated with hospice use.

Our findings also suggest that reduction in spending among hospice users is likely due to lower utilization across a range of services including hospitalizations, ED visits, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy in the last month of life. Thus, our study provides evidence that hospice substitutes for more expensive procedures often utilized at end-of-life. Our results are consistent with a prior study that found a lower likelihood of starting a new chemotherapy agent in last 30 days of life among lung cancer patients that used hospice,15 but to our knowledge, ours is the first study to also demonstrate a reduction in radiation therapy sessions among hospice users.

An important finding from our sub-group analysis is the role of length of hospice enrollment on cost savings. While we find evidence of savings for various lengths of hospice enrollment, we find longer hospice enrollments lead to greater savings.

While our study does not directly measure the impact of hospice on quality of life, the decrease in hospitalizations, ED visits, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy may contribute towards improved quality of life. For example, evidence suggests that chemotherapy at end-of-life can often be therapeutically ineffective and can cause more harm than good by causing symptoms such as pain, nausea, and vomiting.21 Hence, decrease in chemotherapy sessions, along with palliative care provided in hospice is likely to improve quality of life among hospice users.

An important limitation of our study is the lack of cancer stage information. Stage influences both spending and the decision of whether to enroll in hospice. We attempt to address this issue using the indicator of metastasis we constructed. Also, while propensity score matching can be used to balance observed covariates between the two groups and reduce bias, it does not control for unobserved differences between hospice users and non-users. Further, Medicare claims data lack information on functional status, family support, and other characteristics that likely influence end-of-life costs. However, our use of Medicare claims data adds to the strength of the study in the form of large study sample. Finally, we do not have information on home-health costs that may impact our results.

Conclusion

Hospice care among lung cancer patients could reduce the financial burden faced by patients and families towards end-of-life and lead to substantial savings for Medicare - the largest payer for hospice care. While the number of patients using hospice has increased in the last decade, additional patients could benefit from the improved quality of end-of-life resulting from decreased hospitalization, ED visits, and chemotherapy and radiation treatments. It is thus important to facilitate conversations between physicians and patients about end-of-life care over aggressive care by reimbursing physicians for those conversations.

Funding source:

NIH/NIA grant number 1R01AG047934-01, and NIH grant number R24 HD041025

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014 National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, based on November 2016 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Midthun DE. Early detection of lung cancer. F1000Research. 2016;5:739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2014, Featuring Survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2017;109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson BE, Pham H. Cost-effectiveness of hospice care. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 1996;12:417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Lee IC, et al. Does Hospice Improve Quality of Care for Persons Dying from Dementia? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59:1531–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mor V, Kidder D. Cost savings in hospice: final results of the National Hospice Study. Health services research. 1985;20:407–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor DH, Ostermann J, Van Houtven CH, Tulsky JA, Steinhauser K. What length of hospice use maximizes reduction in medical expenditures near death in the US Medicare program? Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1466–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley AS, Deb P, Du Q, Aldridge Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Hospice enrollment saves money for Medicare and improves care quality across a number of different lengths-of-stay. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2013;32:552–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enomoto LM, Schaefer EW, Goldenberg D, Mackley H, Koch WM, Hollenbeak CS. The Cost of Hospice Services in Terminally Ill Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2015;141:1066–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell DE, Lynn J, Louis TA, Shugarman LR. Medicare Program Expenditures Associated with Hospice Use. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140:269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane R, Bernstein L, Wales J, Leibowitz A, Kaplan S. A randomised controlled trial of hospice care. The Lancet. 1984;323:890–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connors AF Jr, Knaus WA, Dawson NV, et al. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Brown ML. Costs of cancer care in the USA: a descriptive review. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2007;4:643–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duggan KT, Hildebrand Duffus S, D’Agostino RB, Petty WJ, Streer NP, Stephenson RC. The Impact of Hospice Services in the Care of Patients with Advanced Stage Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2017;20:29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chastek B, Harley C, Kallich J, Newcomer L, Paoli CJ, Teitelbaum AH. Health care costs for patients with cancer at the end of life. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2012;8:75s–80s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn A, Grosse SD, Zuvekas SH. Adjusting health expenditures for inflation: a review of measures for health services research in the United States. Health services research. 2018. February;53(1):175–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalidindi Y, Jung J, Feldman R. Differences in spending on provider-administered chemotherapy by site of care in Medicare. The American journal of managed care. 2018;24:328–333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman DP, Jena AB, Lakdawalla DN, Malin JL, Malkin JD, Sun E. The value of specialty oncology drugs. Health Services Research. 2010;45:115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher MD, Punekar R, Yim YM, et al. Differences in health care use and costs among patients with cancer receiving intravenous chemotherapy in physician offices versus in hospital outpatient settings. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(1):e37–e46. doi: 10.1200/jop.2016.012930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braga S. Why do our patients get chemotherapy until the end of life? Annals of Oncology. 2011;22:2345–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]