Abstract

Aim:

Previous studies suggest higher mindfulness may be associated with better sleep quality in people with chronic pain conditions. However, the relationship between mindfulness and sleep in fibromyalgia patients, who commonly suffer from sleep problems, remains unstudied. We examined the relationship between mindfulness and sleep, and how this relationship may be mediated by depression, anxiety, and pain interference in fibromyalgia patients.

Method:

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from a randomized trial in fibromyalgia patients. We measured mindfulness (Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire), sleep quality and disturbance (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), PROMIS Sleep Disturbance (PROMIS-SD)), pain interference (PROMIS Pain Interference), and anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale). Pearson correlations were used to examine associations among mindfulness and sleep quality and disturbance. Mediation analysis was conducted to assess whether pain interference, depression, and anxiety mediated the relationship between mindfulness and sleep.

Results:

A total of 177 patents with fibromyalgia were included (93% female, mean age: 52±12 years, BMI: 30±7 kg/m2, 59% white). Higher mindfulness was associated with better sleep quality and less sleep disturbance (PSQI: r=−0.23, P=0.002, PROMIS-SD: r=−0.24, P=0.002) as well as less pain interference (r=−0.31, P<0.0001), anxiety (r=−0.58, P<0.001), and depression (r=−0.54, P<0.0001). Pain interference, depression, and anxiety mediated the association between mindfulness and sleep quality and disturbance.

Conclusion:

Higher mindfulness is associated with better sleep in patients with fibromyalgia, with pain interference, depression, and anxiety mediating this relationship. Longitudinal studies are warranted to examine the potential effect of cultivating mindfulness on sleep in fibromyalgia.

Keywords: Fibromyalgia, sleep, depression, anxiety, chronic pain, mediation

INTRODUCTION

Over 90% of patients with fibromyalgia report having problems with sleep, making it one of the central concerns of patients with the condition (1,2). The impact of poor sleep is all-encompassing; it affects mood, quality of life, work productivity, and the ability to cope with pain (3-5). Moreover, the individuals with fibromyalgia who have sleep problems also tend to experience more pain, disability, and emotional stress than those who do not have sleep problems (2,6). Although the mechanisms leading to poor sleep in fibromyalgia are still under study, many of the features of fibromyalgia such as pain and depression are known to contribute to poor sleep quality (1,7). Conversely, sleep problems likely interact with clinical dimensions such as depression and anxiety to have a synergistic negative impact on well-being in fibromyalgia patients (5,8). In order to better understand the complex nature of sleep in fibromyalgia, further investigation of sleep in relation to overall psychological functioning is essential.

Growing evidence over the past decades has identified mindfulness as a contributor to better psychological and physical health (9-11). Mindfulness is a characteristic defined as the ability to observe, describe, or be aware of present moment experiences without judgment or reactivity. Mindfulness has been linked to better psychological health because it promotes increased attention and emotional regulation, and an enhanced awareness of self (12). In fibromyalgia, studies have demonstrated that patients with higher mindfulness experience better psychological health, less pain interference in daily activities, better coping with pain, and lower overall impact of symptoms (13,14). Moreover, prior literature has demonstrated that higher mindfulness is associated with better sleep quality in chronic conditions such as HIV, multiple sclerosis, and asthma (15-17). However, the relationship between mindfulness and sleep in fibromyalgia remains unknown. Elucidating this relationship in fibromyalgia patients will inform our understanding of the complex interplay of clinical dimensions of the condition.

Recent literature has further characterized mindfulness as composed of five facets: Observing, Describing, Acting-with-Awareness, Non-judging, and Non-reacting (18,19). Stronger levels of the Describing, Acting-with-Awareness, and Non-judging facets of mindfulness have consistently been associated with better psychological health (10,11,13,20-23). A study in fibromyalgia patients showed that these three facets are associated with less anxiety, depression, stress, and better quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia (14). It is unknown whether the same facets of mindfulness may be associated with better sleep.

The primary objective of this study was to examine the association between mindfulness and sleep quality and disturbance in the context of fibromyalgia. Further, we evaluated the potential mediating effects of pain interference, anxiety, and depression in the association between mindfulness and sleep. We hypothesized that higher levels mindfulness would be associated with better sleep quality in fibromyalgia, and this relationship may be mediated by pain interference, anxiety, and depression.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional secondary analysis of baseline data from a randomized controlled trial comparing Tai Chi and aerobic exercise for patients with fibromyalgia. All data were collected at Tufts Medical Center, an urban academic tertiary hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. A detailed protocol was previously published in reference to recruitment, intervention, and follow-up procedures (24).

Participants were recruited through flyers and advertisements in local media and the rheumatology clinic at Tufts Medical Center, which identified and referred potential participants. Interested respondents received information about the study and completed a preliminary screening over the phone. Respondents were invited to a formal screening at the clinic if they met eligibility criteria, including: 1) being 21 years or older and 2) fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 classification criteria and 2010 diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia (25,26). Respondents were excluded if they: 1) had participated in Tai Chi or other similar types of mind-body approaches such as qigong or yoga in the past six months; 2) had serious medical conditions limiting ability to participate in Tai Chi or aerobic exercise; 3) had diagnosed medical conditions known to contribute to fibromyalgia symptomatology, such as thyroid disease, inflammatory arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, myositis, vasculitis, or Sjogren’s syndrome; 4) were unable to pass the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire; 5) scored below 24 on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (27); 6) planned to relocate from the region during the trial period; 7) verbally confirmed they were pregnant or planned to become pregnant during the study period; or 8) did not speak English. Signed informed consent was obtained from each study participant. All randomized participants who completed the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) were included in this study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Tufts Medical Center (approval #9945).

Measures

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was measured using the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), a validated, 39-item self-report questionnaire that measures the ability to be mindful of one’s daily life (18,28). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-like scale. Total FFMQ score ranges from 39-195 and is composed of five subscales that measure the five facets of mindfulness: (1) Observing (8 items, range 8-40), defined as attending to internal or external experiences, such as sensations, thoughts, and emotions; (2) Describing (8 items, range 8-40), defined as conveying internal experiences with words; (3) Acting-with-awareness (8 items, range 8-40), defined as attending to activities in the present moment; (4) Non-judging of inner experience (8 items, range 8-40), defined as applying a non-evaluative stance towards thoughts and feelings; and (5) Non-reactivity to inner experience (7 items, range 7-35), defined as allowing thoughts and feelings to flow without becoming engrossed in them. Higher scores indicate higher levels of mindfulness.

Fibromyalgia Impact

Fibromyalgia impact was measured using the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR). The FIQR is a 21-item, validated self-report instrument that assesses overall impact of fibromyalgia symptoms including pain, function, fatigue, mental health, and overall well-being over the past seven days (29). Total scores, calculated from the three subscales, range from 0-100. Higher scores indicate greater impact of fibromyalgia symptoms.

Sleep Quality and Disturbances

Sleep quality and disturbance was assessed by the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (30). This 19-item scale assesses seven components of sleep quality and disturbances during the past month, including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is assessed on a 4-point Likert scale with a range in global score from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate worse sleep quality.

Sleep quality and disturbance was also measured using the PROMIS Adult Short Form: Sleep Disturbance (PROMIS-SD), one of seven subscales comprising the Participant-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) static short forms (31). The 8-item PROMIS-SD measure evaluates overall sleep quality, disturbances, and satisfaction over the past 7 days on 5-point scales. Raw scores were converted into t-scores ranging from 28.9 to 76.5, with higher scores indicating greater sleep disturbance.

The PSQI is the most widely used self-report instrument for measuring sleep quality and disturbance, although it has been reported to have relatively poor ability to discriminate between lower sleep disturbance scores (32). PROMIS Sleep Disturbance, which was developed using classical test theory methods and item response theory analyses, is thought to have greater measurement precision than the PSQI (32). In this study, we used both measures for a more robust assessment of sleep quality and disturbance.

Pain Interference

Pain interference was assessed using the PROMIS Adult Short Form 6b: Pain Interference (PROMIS-PI), which measures the degree to which pain limits or interferes with physical, mental, emotional, and social activities in the past seven days (33). The instrument consists of 6 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale and has high validity and reliability. Raw scores were converted into t-scores ranging from 41.0 to 78.3, with higher scores representing worse pain impact.

Depression & Anxiety

Levels of depression and anxiety were assessed using The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a validated, 14-item self-report questionnaire (34). The questionnaire contains two 7-item subscales with scores ranging from 0-21. The two subscales are HADS-A for Anxiety and HADS-D for Depression. Higher scores reflect greater symptom severity.

Statistical Analysis

Data were checked for normality of distribution. Pearson correlations were used to assess associations of mindfulness with sleep quality and disturbance, pain interference, anxiety, and depression.

For the mediation analysis, the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) scale was inverted to facilitate interpretation such that higher values indicated worse mindfulness. Linear regression models were used to test whether pain interference, depression, and anxiety mediated the association between mindfulness and PSQI, and the association between mindfulness and PROMIS-SD, following the criteria outlined below. Each potential mediating variable was introduced into a single mediator model to assess its effect after controlling for age, sex, race, and education. Prior to data analysis, these variables were determined to be the major demographic factors that may be associated with sleep, pain, depression, and anxiety in patients with fibromyalgia.

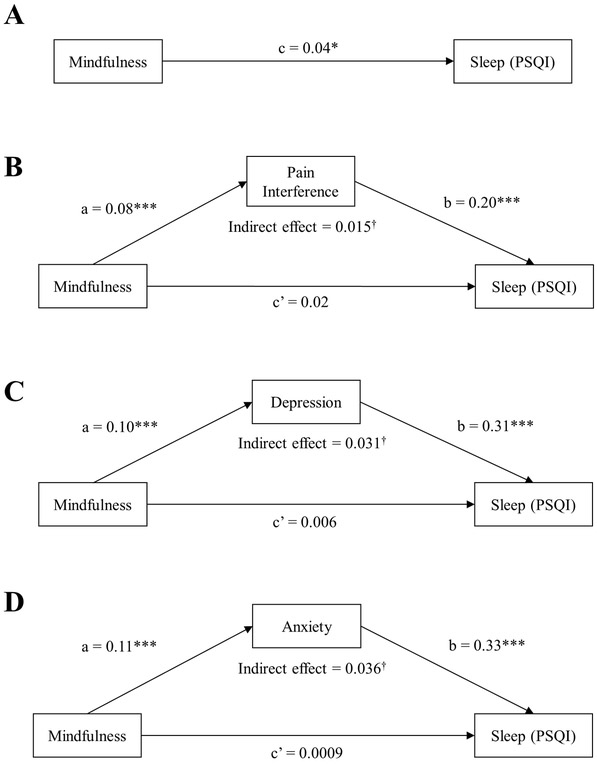

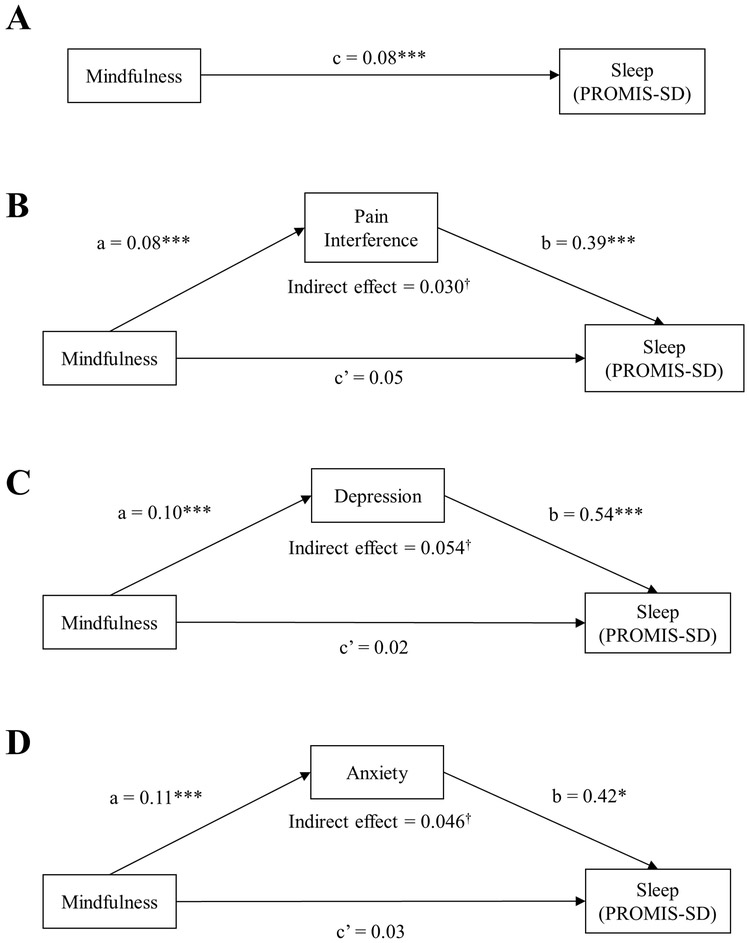

Mediation was determined according to the implementation of Baron and Kenny criteria (35). Partial mediation was fulfilled if (1) the causal variable (mindfulness) was significantly associated with the outcome variable (PSQI or PROMIS-SD) (path c); (2) the causal variable (mindfulness) was significantly associated with the proposed mediator (pain interference, depression, or anxiety) (path a); and (3) the proposed mediator was significantly associated with the outcome variable (PSQI or PROMIS-SD) after adjusting for the causal variable (mindfulness) (path b) (Figure 1, 2). The amount of mediation, or indirect effect, was calculated as a*b. The Sobel Test was used to test the significance of the indirect effect. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4, and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Figure 1.

A. Total effect (path c) of mindfulness on sleep disturbance and quality, measured by PSQI. Figure 1B-D. Effect of mindfulness on the mediator (path a) and effect of the mediator on sleep, controlling for mindfulness (path b). Direct effect (path c’) of mindfulness on sleep, i.e. total effect adjusted for effects of pain interference (Figure 1B), depression (Figure 1C), and anxiety (Figure 1D). All analyses are controlled for age, sex, race, and education. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Mindfulness is measured by the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, sleep quality and disturbance by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), pain interference by PROMIS Pain Interference, depression and anxiety by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. †Indicates significance of the indirect effect at the level of p < 0.05 based on the Sobel test.

Figure 2.

A. Total effect (path c) of mindfulness on sleep quality and disturbance, measured by PROMIS-SD. Figure 2B-D. Effect of mindfulness on the mediator (path a) and effect of the mediator on sleep, controlling for mindfulness (path b). Direct effect (path c’) of mindfulness on sleep, i.e. total effect adjusted for effects of pain interference (Figure 2B), depression (Figure 2C), and anxiety (Figure 2D). All analyses are controlled for age, sex, race, and education. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Mindfulness is measured by the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, sleep quality and disturbance by PROMIS Sleep Disturbance (PROMIS-SD), pain interference by PROMIS Pain Interference, depression and anxiety by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. †Indicates significance of the indirect effect at the level of p < 0.05 based on the Sobel test.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of the 177 patients with fibromyalgia included in our analysis. Participants had a mean age of 52.0 years, were 93% female, 59% white, 38% college graduates, and had an average BMI of 30.1 kg/m2. The mean disease duration was 13.1 years. The mean total mindfulness score (FFMQ) was 131.3, and mean scores of the five individual facets of mindfulness ranged from 21.7 to 29.5.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n=177)a

| Variable | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age, yrs. | 52.0 ± 12.2 |

| Sex, n(%) | |

| Female | 165(93.2) |

| Race, n(%) | |

| White | 104(58.8) |

| Other | 73(41.2) |

| Level of Education, n (%) | |

| Less than College Degree | 110 (62.2) |

| College Degree or Higher | 67 (37.8) |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 30.1 ± 6.7 |

| Duration of disease, yrs. | 13.1 ± 10.1 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Range: 0-21)* | 11.7 ± 4.0 |

| Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire | |

| Total (Range: 39-195) | 131.3 ± 20.7 |

| Observing (Range: 8-40) | 29.5 ± 5.7 |

| Describing (Range: 8-40) | 27.8 ± 6.2 |

| Acting with Awareness (Range: 8-40) | 24.9 ± 6.8 |

| Non-Judging (Range: 8-40) | 27.4 ± 7.5 |

| Non-Reacting (Range: 7-35) | 21.7 ± 4.9 |

| PROMIS Pain Interference (Range: 41-78.3)*† | 65.2 ± 5.9 |

| PROMIS Sleep Disturbance (Range 28.9-76.5)*† | 59.9 ± 7.8 |

| Symptom Severity (Range: 0-12)* | 8.7 ± 2.0 |

| HADS-Depression (Range: 0-21)* | 7.6 ± 4.1 |

| HADS-Anxiety (Range: 0-21)* | 8.9 ± 4.1 |

| Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (Range: 0-100)* | 57.0 ± 19.4 |

Values reported as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted

Indicates tests with higher scores indicating worse outcomes; better outcomes unmarked.

PROMIS Pain Interference and PROMIS Pain Interference reported in t-scores

PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Table 2 illustrates the associations between mindfulness and sleep, pain interference, and psychological health measures. All significant associations were in the expected direction of higher mindfulness correlating with better health outcomes. Specifically, higher total mindfulness was significantly associated with better sleep (PSQI: r = −0.23, P = 0.002; PROMIS-SD: r = −0.24, P = 0.002), less pain interference (PROMIS-PI: r = −0.31, P < 0.001), and better psychological health (HADS-D: r = −0.54, P < 0.0001, HADS-A: r = −0.58, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Associations between Facets of Mindfulness and Sleep, Pain Interference, Anxiety, and Depression (n = 177)

| PSQI | PROMIS Sleep |

PROMIS Pain |

HADS-D | HADS-A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total FFMQ† | −0.23** | −0.24** | −0.31** | −0.54** | −0.58** |

| FFMQ† Facet | |||||

| Observing | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.19* | −0.11 |

| Describing | −0.15* | −0.17* | −0.26** | −0.38** | −0.33** |

| Acting with Awareness | −0.15* | −0.16* | −0.25** | −0.47** | −0.53** |

| Non-judging | −0.29** | −0.19* | −0.26** | −0.40** | −0.57** |

| Non-reacting | −0.13 | −0.19* | −0.19* | −0.30** | −0.28** |

Note: *p<0.05,

p < 0.01;

Higher scores indicate higher mindfulness; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (range 0-21), higher scores indicate worse sleep quality; PROMIS-SD = PROMIS Sleep Disturbance t-score (range 28.9-76.5), higher scores indicate more sleep disturbance; PROMIS-PI = PROMIS-Pain Interference t-score (range 41-78.3), higher scores indicate worse pain interference; HADS-D/HADS-A = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale depression/anxiety subscales (range 0-21), higher scores indicate worse symptoms.

Of the five facets, the Describing, Acting with Awareness, and Non-judging facets were significantly associated with all measures (PSQI, PROMIS-SD, PROMIS-PI, HADS-D, HADS-A). The Non-reacting facet was significantly associated with all measures except PSQI. In contrast, the Observing facet was only significantly associated with depression (HADS-D).

Mediating Effects of Pain Interference, Depression, and Anxiety

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual models and the results of the mediation analyses on the association between mindfulness and sleep quality and disturbance (PSQI). Mindfulness was significantly correlated with sleep (path c: β = 0.04; P = 0.01), establishing a significant effect that may be mediated (Figure 1A). The criteria for partial mediation as outlined by Baron and Kenny were fulfilled with pain interference as the mediating variable, such that: (1) mindfulness was significantly correlated with pain interference (path a: β = 0.08; P = 0.0002); and (2) pain interference was significantly correlated with sleep (path b: β = 0.20; P = 0.0002) after adjusting for age, sex, race, and education (Figure 1B). The direct effect of mindfulness on sleep, controlling for pain interference, was β = 0.02, P = 0.14 (path c’). Since the effect size of path c’ was not zero, partial mediation by pain interference was fulfilled. The indirect effect of mediation (a*b = 0.015) was significant (Sobel Z = 2.71; P = 0.007). Thus, the relationship between mindfulness and sleep quality and disturbance as measured by PSQI was significantly mediated by pain interference.

Based on these criteria, anxiety and depression were also partial mediators of the effect of mindfulness on sleep quality and disturbance (PSQI) (Figures 1C-D). Similarly, the relationship between mindfulness and sleep quality and disturbance as measured by PROMIS-SD was also significantly mediated by all three proposed mediators: pain interference, anxiety, and depression (Figure 2).

In sum, higher mindfulness was associated with less pain interference, less anxiety, and less depression, which in turn were associated with better sleep quality. Mediation results were maintained when using two different measures of sleep quality and disturbance.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to investigate the relationship between mindfulness and sleep among a large and diverse sample of patients with fibromyalgia. We found that higher mindfulness was associated with better sleep quality and less sleep disturbance in patients with fibromyalgia. We further demonstrated that pain interference, depression, and anxiety mediated the relationship between mindfulness and sleep in fibromyalgia patients.

Our results align with evidence showing higher mindfulness is associated with better sleep quality in males living with HIV, postmenopausal women with insomnia, post-treatment patients with cancer, and patients with asthma and multiple sclerosis (15-17,36,37). Our findings are also consistent with studies examining the effect of mindfulness-cultivating interventions on sleep quality in fibromyalgia patients. Such interventions have been shown to improve sleep quality, as well as reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and pain interference (38-42). Understanding the factors that may influence the effect of mindfulness will enhance the development of therapies that aim to cultivate mindfulness in patients with fibromyalgia and their implementation into clinical care.

Of the five facets of mindfulness, higher levels of three facets, Describing, Acting with Awareness, and Non-judging, were associated with better sleep quality, less pain interference, and fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms. Higher levels of the Describing, Acting with Awareness, and Non-judging facets have previously been demonstrated to be associated with better psychological health in chronic pain and other clinical and healthy populations (10,11,13,20-23). However, this is the first study to our knowledge to show that these three facets of mindfulness also correlate with better sleep quality and less sleep disturbance. This supports the conceptualization of mindfulness as being composed of distinct but related components, in which related components may have similar therapeutic value for health.

In addition, our mediation analyses indicate that higher mindfulness is associated with less pain interference and fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms, which in turn relate to better sleep quality and less sleep disturbance. The individual relationships that compose these mediation models are conceptually supported by previous evidence. The positive effects of mindfulness on pain interference, depression, and anxiety have been recognized in studies of patients with fibromyalgia (14,43). Of note, higher mindfulness can attenuate the subjective experience of pain and protect against psychological symptoms. It is also supported that greater pain interference, depression, and anxiety contribute to poor sleep quality in fibromyalgia (1,5,44). These relationships among mindfulness, anxiety, depression, pain interference, and sleep reveal a complex interplay of clinical and psychosocial parameters that contribute to sleep problems in fibromyalgia. This suggests that symptom-specific treatment targeting poor sleep alone in fibromyalgia may be ineffective. Therefore, a more holistic approach to patient evaluation assessing psychosocial and physical health is warranted. Taken together, clinicians may find it most effective to devise a multimodal therapeutic strategy that influences multiple clinical characteristics, such as mindfulness and depression, in order to improve sleep in fibromyalgia.

Our findings should be interpreted with caution due to some limitations. First, even though previous evidence supports the conceptual models of mediation presented, the cross-sectional nature of the study precludes definitive conclusions about the direction of associations among variables (5,43). Future longitudinal studies are warranted to further disentangle these relationships. Second, average Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) score was higher in this population than in other samples of patients with chronic pain and healthy adults (13,19,45,46). It is unclear how higher average mindfulness score influenced our findings. Finally, as this study was a secondary analysis, we were not able to investigate the influence of sleep-related factors that were not measured in the parent study, such as the effects of sleep disorders or medications affecting sleep.

However, an important strength of this study is the large and diverse sample of patients with fibromyalgia, as it increases generalizability to patient populations encountered in clinical settings. In addition, the results regarding sleep quality and disturbance were consistent between analyses using PSQI and PROMIS-Sleep Disturbance measures, which strengthen support for our findings.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that higher mindfulness is associated with better sleep quality and less sleep disturbance in patients with fibromyalgia. The associations between mindfulness and sleep measures were mediated by pain interference, anxiety, and depression. Thus, multimodal therapeutic strategies influencing multiple clinical characteristics, including mindfulness and psychosocial factors, may be essential to improving sleep quality for individuals with fibromyalgia. Longitudinal studies are needed to further evaluate the causality and directionality of these relationships and should consider measuring change in mindfulness to evaluate its longitudinal effect on sleep in fibromyalgia populations.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health (R01AT006367, K24AT007323, and K23AT009374) and the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (UL1 RR025752) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (UL1TR000073 and UL1TR001064). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCIH. The investigators are solely responsible for the content of the manuscript and decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest:

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Bigatti SM, Hernandez AM, Cronan TA, Rand KL. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: Relationship to pain and depression. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theadom A, Cropley M, Humphrey K-L. Exploring the role of sleep and coping in quality of life in fibromyalgia. J Psychosom Res 2007;62:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stranges S, Tigbe W, Gómez-Olivé FX, Thorogood M, Kandala N-B. Sleep Problems: An Emerging Global Epidemic? Findings From the INDEPTH WHO-SAGE Study Among More Than 40,000 Older Adults From 8 Countries Across Africa and Asia. Sleep 2012;35:1173–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strine TW, Chapman DP. Associations of frequent sleep insufficiency with health-related quality of life and health behaviors. Sleep Med 2005;6:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choy EHS. The role of sleep in pain and fibromyalgia. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirõ E, Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Prados G, Medina A. When is pain related to emotional distress and daily functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome? the mediating roles of self-efficacy and sleep quality. Br J Health Psychol 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicassio PM, Moxham EG, Schuman CE, Gevirtz RN. The contribution of pain, reported sleep quality, and depressive symptoms to fatigue in fibromyalgia. Pain 2002;100:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia. JAMA 2014;311:1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiner K, Tibi L, Lipsitz JD. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature. Pain Med 2013;14:230–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee AC, Harvey WF, Price LL, Morgan LPK, Morgan NL, Wang C. Mindfulness is associated with psychological health and moderates pain in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2017;25:824–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poulin PA, Romanow HC, Rahbari N, Small R, Smyth CE, Hatchard T, et al. The relationship between mindfulness, pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, depression, and quality of life among cancer survivors living with chronic neuropathic pain. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:4167–4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci 2011;6:537–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones KD, Mist SD, Casselberry MA, Ali A, Christopher MS. Fibromyalgia Impact and Mindfulness Characteristics in 4986 People with Fibromyalgia. Explor J Sci Heal 2015;11:304–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pleman B, Park M, Han X, Price L, Bannuru R, Harvey W, et al. Mindfulness is associated with psychological health and moderates the impact of fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol 2019;38:1737–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell R, Vansteenkiste M, Delesie L, Soenens B, Tobback E, Vogelaers D, et al. The role of basic psychological need satisfaction, sleep, and mindfulness in the health-related quality of life of people living with HIV. J Health Psychol 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagnini F, Cavalera C, Rovaris M, Mendozzi L, Molinari E, Phillips D, et al. Longitudinal associations between mindfulness and well-being in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J Clin Heal Psychol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao D, Wang H, Feng X, Lv G, Li P. Relationship between neuroticism and sleep quality among asthma patients: the mediation effect of mindfulness. Sleep Breath 2019;Epub ahead. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mindfulness. Assessment 2006;13:27–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, et al. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 2008;15:329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son J van, Nyklíček I, Nefs G, Speight J, Pop VJ, Pouwer F. The association between mindfulness and emotional distress in adults with diabetes: Could mindfulness serve as a buffer? Results from Diabetes MILES: The Netherlands. J Behav Med 2015;38:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bränström R, Duncan LG, Moskowitz JT. The association between dispositional mindfulness, psychological well-being, and perceived health in a Swedish population-based sample. Br J Health Psychol 2011;16:300–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desrosiers A, Klemanski DH, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Mapping Mindfulness Facets Onto Dimensions of Anxiety and Depression. Behav Ther 2013;44:373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraemer KM, McLeish AC, Johnson AL. Associations between mindfulness and panic symptoms among young adults with asthma. Psychol Heal Med 2015;20:322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, McAlindon T, Fielding RA, Harvey WF, Driban JB, Price LL, et al. A novel comparative effectiveness study of Tai Chi versus aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:600–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park T, Reilly-Spong M, Gross CR. Mindfulness: A systematic review of instruments to measure an emergent patient-reported outcome (PRO). Qual Life Res 2013;22:2639–2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, Ward R, Han BK, Ross RL. The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ, III CFR, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buysse DJ, Yu L, Moul DE, Germain A, Stover A, Dodds NE, et al. Development and validation of patient-reported outcome measures for sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairments. Sleep 2010;33:781–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu L, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, Stover A, Dodds NE, et al. Development of Short Forms From the PROMISTM Sleep Disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment Item Banks. Behav Sleep Med 2011;10:6–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenny DA. Mediation. 2018. Available at: http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm#REF. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- 36.Garcia MC, Pompéia S, Hachul H, Kozasa EH, Souza AAL de, Tufik S, et al. Is mindfulness associated with insomnia after menopause? Menopause 2014;21:301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garland SN, Campbell T, Samuels C, Carlson LE. Dispositional mindfulness, insomnia, sleep quality and dysfunctional sleep beliefs in post-treatment cancer patients. Pers Individ Dif 2013;55:306–311. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Schmid CH, Fielding RA, Harvey WF, Reid KF, Price LL, et al. Effect of tai chi versus aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia: comparative effectiveness randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2018:k851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grossman P, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer U, Raysz A, Kesper U. Mindfulness training as an intervention for fibromyalgia: evidence of postintervention and 3-year follow-up benefits in well-being. Psychother Psychosom 2007;76:226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cash E, Salmon P, Weissbecker I, Rebholz WN, Bayley-Veloso R, Zimmaro LA, et al. Mindfulness Meditation Alleviates Fibromyalgia Symptoms in Women: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Behav Med 2015;49:319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon W Van, Shonin E, Dunn TJ, Garcia-Campayo J, Griffiths MD. Meditation awareness training for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Br J Health Psychol 2017;22:186–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amutio A, Franco C, Sánchez-Sánchez LC, Pérez-Fuentes M del C, Gázquez Linares JJ, Gordon W Van, et al. Effects of mindfulness training on sleep problems in patients with fibromyalgia. Front Psychol 2018;9:1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brooks JM, Muller V, Sánchez J, Johnson ET, Chiu C-Y, Cotton BP, et al. Mindfulness as a protective factor against depressive symptoms in people with fibromyalgia. J Ment Heal 2017;0:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munguia-Izquierdo D, Legaz-Arrese A. Determinants of sleep quality in middle-aged women with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Sleep Res 2012;21:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curtis K, Osadchuk A, Katz J. An eight-week yoga intervention is associated with improvements in pain, psychological functioning and mindfulness, and changes in cortisol levels in women with fibromyalgia. J Pain Res 2011;4:189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KMG, Bohlmeijer ET. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2011;152:533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]