Abstract

Objective:

Steady state insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels vary significantly during continuous intravenous infusion of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1/recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3) in the first weeks of life in extremely preterm infants. We evaluated interleukin-6 (IL-6) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) levels as predictors of low IGF-1 levels.

Methods:

Nineteen extremely preterm infants were enrolled in a trial, 9 received rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 and 10 received standard neonatal care. Blood samples were analyzed daily for IGF-1, IL-6 and IGFBP-1 during intervention with rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3.

Results:

Thirty seven percent of IGF-1 values during active treatment were < 20 μg/L. Among treated infants, higher levels of IL-6, one and two days before sampled IGF-1, were associated with IGF-1 < 20 μg/L, gestational age adjusted OR 1.30 (95% CI 1.03–1.63), p = .026, and 1.57 (95% CI 1.26–1.97), p < .001 respectively. Higher levels of IGFBP-1 one day before sampled IGF-1 was also associated with IGF-1 < 20 μg/L, gestational age adjusted OR 1.74 (95% CI 1.19–2.53), p = .004.

Conclusion:

In preterm infants receiving continuous infusion of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3, higher levels of IL-6 and IGFBP-1 preceded lower levels of circulating IGF-1. These findings demonstrate a need to further evaluate if inflammation and/or infection suppress serum IGF-1 levels.

Keywords: IGF-1, Preterm infants, Inflammation, rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3, IL-6, IGFBP-1

1. Introduction

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is an important fetal growth factor and regulator of development. Fetal serum levels of IGF-1 increase during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy [1,2]. Postnatal levels of IGF-1 rise more slowly than levels in utero [3] and the levels are substantially lower in preterm infants relative to levels in fetuses of corresponding gestational age (GA) [4]. Postnatal IGF-1 deficiency is associated with complications of extreme prematurity, including bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), neurodevelopmental impairment, and growth restriction [5–8].

A study of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1/recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3), administered as a continuous intravenous (IV) infusion until estimated endogenous IGF-1 levels were within physiological range, was undertaken to assess the prevention of ROP and other complications of prematurity. The phase II trial initiated in Nov 2011 was designed in three sections (A, B and C) to investigate dosing, pharmaco-kinetics, safety and efficacy of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 treatment. A fourth section (D), to evaluate effect on severity of ROP, was completed in March 2016. Feasibility and safety data from section A-C as well as results from section D have been previously published [9–12].

In study sections B, C and D, steady state IGF-1 levels varied significantly between patients during continuous IV infusion of rhIGF-1/ rhIGFBP-3 [12]. In order to better understand variability of steady state IGF-1 levels during treatment in extremely preterm infants, this study used samples from sub-sections B and C of the randomized control trial. Insulin like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) is a major determinant of free IGF-1 availability [13]. The endocrine system is known to interact with the immune system [14], and interleukin-6 (IL-6) is an inflammatory biomarker that is easy to detect and has been previously associated with low levels of IGF-1 in preterm infants [15]. A negative correlation between IL-6 and IGF-1, and a positive correlation between IL-6 and IGFBP-1 has been shown in cord blood from preterm infants [16]. Children with chronic inflammatory diseases in childhood have reduced levels of IGF-1 and elevated levels of IL-6 [17], and a positive correlation between IL-6 and IGFBP-1 has been demonstrated in infants with fetal growth restriction [18]. The aim of this study was to determine the correlation between simultaneous levels of IGF-1 and the biomarkers IL-6 and IGFBP-1, and the prediction of low IGF-1 during continuous IV infusion of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3, in extremely preterm infants using a priori collected IL-6 and IGFBP-1 samples.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

Infants were randomized 1:1 to receive rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 or standard neonatal care. Infants with GA at birth between 23 weeks +0 days and 27 weeks +6 days were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included maternal diabetes requiring insulin; monozygotic twins; detectable gross malformation; known or suspected chromosomal abnormality, genetic disorder or syndrome; clinically significant neurological disease; persistent blood glucose levels < 2.5 mmol/L or > 10 mmol/L on day of birth. Infants were enrolled from November 22, 2011 to July 30, 2013 at two clinical sites in Sweden (Skåne University Hospital, Lund; Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm). Randomization was stratified by clinical site and GA. 19 preterm infants were enrolled, 9 received rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 and 10 standard neonatal care, supplemental Fig. A.1. Details from the study protocol have been previously described [10] and is outlined in Supplement A. The sample size was based on the primary aims for the randomized clinical trial.

Approval was obtained from the regional ethics review board in Gothenburg, Sweden before study initiation (IRB number 203–09). All parents/guardians of the study infants provided written informed consent. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov ().

2.2. Intervention

The study drug rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 (mecasermin rinfabate) is a 1:1 M ratio of the noncovalent complex of rhIGF-1 and rhIGFBP-3. Administration via continuous IV infusion was performed by trained study personnel through a central or peripheral venous line using an infusion syringe pump. Saturation targets and nutrition protocol were harmonized across sites. Parenteral and enteral nutrition were administered according to a standardized protocol, aiming at early achievement of optimized total protein intake (4.0–4.5 g/kg/day) and energy (120 kcal/kg/day). Neonatal care was otherwise determined based upon the individual condition of the infant.

Infusion started within 24 h after birth and was to continue until the infant’s endogenous production of IGF-1 was considered sufficient for the infant to reach and maintain the targeted serum levels, or up to a postmenstrual age of maximum 29 weeks +6 days. Estimated endogenous IGF-1 level was calculated based on serum IGF-1, dose of the study drug, clearance and weight.

Dosing of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 intended to establish serum IGF-1 within a reference target range (20–60 μg/L) based on published levels in fetal blood measured by cordocentesis (18–38 weeks GA) [1]. The starting dose of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 was calculated using an algorithm based on results from a phase I study [19] incorporating GA, basal IGF-1 concentration and birth weight. Mean (min-max) starting dose among the infants in the active treatment group in this trial was 97.9 (75–106) μg/kg.

Sampling was carried out throughout the study at regular intervals. In the intervention group, a blood sample was obtained immediately before the start of the first infusion, at 4 and 12 h after initiation of infusion and thereafter one sample was to be obtained 6 h after the start of each infusion interval (24 h). In the control group, blood sampling was performed at study day 1 and thereafter at least once weekly during the study period. The median (range) number of samples per infant during the first 14 days was 14 (8–15) days in the intervention group, and 9 (7–9) days in the control group. The infant’s total IGF-1 serum level, as determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Mediagnost GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) [20], was used to adjust the dose of the study drug (at the discretion of the investigators) to maintain the infant’s serum IGF-1 within the targeted range.

All adverse events were prospectively registered as previously decribed [10]. The records were reviewed in this study to identify all events related to infection/inflammation during active treatment and all events within two days of IGF-1 levels < 20 μg/L.

2.3. Biomarker analyses

All blood samples for immunochemical analyses were stored in −70 °C before analysis. Samples for measurements of IGF-1 concentrations were diluted 1:50 and analyzed by an IGF binding-protein blocked competitive radioimmunoassay, performed without extraction in the presence of an approximately 250-fold excess of IGF-2. A secondary antibody, diluted in PolyEthyleneGlycol, was added after 3 days incubation with primary antibody. Then bound IGF-1 was precipitated by centrifugation. The method has been described previously (Mediagnost GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) [20]. Lowest level for detection was 0.064 μg/L. Inter-assay CVs were 29.0%, and 11.3% at 9 μg/L and 33 μg/L, respectively. Intra-assay CVs were 18.5%, and 11.4% at 9 μg/L and 33 μg/L, respectively.

Samples for analysis of serum concentrations of IL-6 were diluted 1:4 and analyzed in duplicate by Luminex xMAP assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Lowest detection limit was 0.04 pg/mL. Inter-assay coefficient of variation (CVs) was for 11.3% at 101 pg/mL and intra-assay CV was 6.9%. Beads and antibodies within the assay were from the same batches.

Serum concentrations of IGFBP-1 were analyzed in duplicate by an ELISA method (Mediagnost GmbH) according to instructions provided by the manufacturer. The assay detected all but the most phosphorylated form of IGFBP-1. Samples were routinely diluted 1:32 before analysis, but in cases where concentrations exceeded highest detection limits, samples where further diluted 1:32–1:128. Lowest detection limit was 0.02 μg/L. Inter-assay CVs were 5.2%, 7.4% and 6.8% at 2.3 μg/L, 18 μg/L and 33 μg/L, respectively. Intra-assay CVs were 5.9%, 6.2% and 6.8% at 1.5 μg/L, 21 μ/L and 163 μg/L, respectively. All ELISA kits were from the same batches.

2.4. Statistical methods

For descriptive purposes mean, standard deviation (SD), median, min-max or inter-quartile range (IQR) are presented where applicable for continuous variables and number and percentage for categorical variables. Area Under the Curve (AUC) for inflammatory biomarkers was calculated by using trapezoidal method for days 0–7, 0–14, 0–21. Samples from infants in the intervention group were separated into active and non-active treatment period (period after stop of treatment).

Due to small sample size non-parametric methods were applied. The relationship between two biomarkers within a study group was tested by using Wilcoxon Signed rank test on Spearman correlation coefficients calculated for each patient over repeated measures data. The relationship between treated patients and controls with respect to continuous variables was tested by using Mann-Whitney U test and for dichotomous variables the Fisher’s Exact test. The overall test between the groups with respect to a continuous variable was performed by using Kruskal-Wallis test.

Longitudinal mean curve and its 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for values of IGF-1, IL-6 and IGFBP-1 values over time for active intervention, non-active intervention and control groups were estimated by using random coefficient models with unstructured covariance pattern, and underlying cubic splines allowing for non-linear changes over time. Gaussian distribution including an empirical bias correction of covariance estimators was found satisfactory based on residual plots. SAS Software procedure PROC GLIMMIX was used.

To identify the explanatory factors for low values of IGF-1 (< 20 μg/L), Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) for binary outcome and repeated data adjusting for within-patient correlation, with logit-link function was used. The optimal covariance pattern was selected based on lowest Quasilikelihood under the Independence model Criterion (QIC). The provided efficacy measure from these analyses were odds-ratios expressed by 1 unit increase (OR), with associated 95% CI and p-values. For each biomarker, the relationship between IGF-1 levels < 20/≥20 μg/L and potentially explanatory variables were analyzed: biomarker level two days before (day −2) each longitudinal IGF-1 sample, biomarker level one day before (day −1) each longitudinal IGF-1 sample and biomarker level on the day of sampled IGF-1 (day 0). The non-linear and natural logarithmic functions of explanatory variables were explored. Univariable as well as analyses adjusted for gestational age were performed. Significant relationships were depicted as probability plots.

All tests were two-tailed and conducted at 0.05 significance level. All analyses were performed using SAS Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US).

3. Results

3.1. Biomarkers in rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 treated versus in standard of care infants

For the 9 infants treated with study drug, mean dose was 95.1 (SD 10.6) μg/kg/day and the median duration of infusion was 12 (IQR 4–22) days. Follow-up time was median 96 (IQR 93–104) days in the treated group and 97 (IQR 91–108) days in the control group. The two groups were balanced with respect to gestational age and sex. Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics.

| Intervention, rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 (n = 9) | Standard neonatal care (n = 10) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (40.0%) | 1.000 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 26.1 (1.1) | 25.8 (1.5) | 0.902 |

| 26.4 (24.4; 27.6) | 26.4 (23.4; 27.3) | ||

| Birth weight (g) | 910 (164) | 779 (153) | 0.102 |

| 935 (670; 1120) | 753 (620; 1100) |

For categorical variables n (%) is presented. For continuous variables Mean (SD)/Median (Min; Max) are presented. rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3: recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1/recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3.

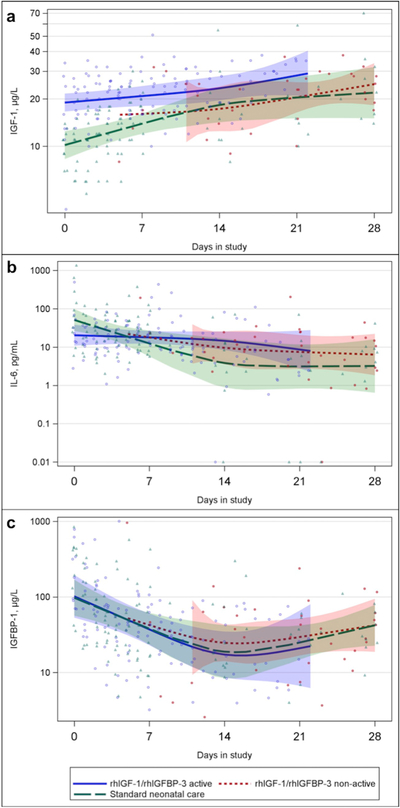

All longitudinal values of IGF-1, IL-6 and IGFBP-1 between days 0–28 and estimated mean curve with 95% CI are shown in Fig. 1a–c. Serum levels of IGF-1 were numerically higher for 0–28 days for infants during treated period compared to the non-treated period and infants randomized to standard care. No obvious patterns could be observed in levels of IL-6 or IGFBP-1 for the study groups. During the first 14 days of treatment, area under the curve (AUC) serum levels of IGF-1 were 22.1 (SD 4.1) μg/L, compared with 15.5 (SD 4.8) μg/L in control infants, p = .010. AUC values up to day 7, 14 and 21 of IGF-1, IL-6 and IGFBP-1 and test between groups are shown in supplemental Table A.1 for treated infants during active and non-active treatment period and for controls.

Fig. 1.

Biomarkers over time for treated infants during active and non-active treatment periods and controls. Individual values, estimated mean and 95% CI for active intervention (blue unfilled circles, solid line), non-active intervention (red filled circles, short dash line) and controls (green triangles, long dash line) are demonstrated.

a: Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1, μg/L) b: Interleukin-6 (IL-6, pg/mL) c: Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1, μg/L). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Biomarkers associated with decreased serum IGF-1 levels during treatment

Out of 127 longitudinal IGF-1 values from infants in the intervention group during active treatment period 47 (37%) were < 20 μg/L. There was a significant reduction in low IGF-1 values with increasing GA, OR 0.63 (95% CI 0.41–0.98), p = .039 per one week increase. Table 2.

Table 2.

Univariable and gestational age adjusted association between IGF-1 levels < 20 μg/L and selected variables preceding days during active intervention.

| Predictors | Number of samples for 9 infants with active intervention | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) p-value | Adjusted for GA OR (95% CI) p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) | 127 | 0.63 (0.41–0.98) | |

| p = .039 | |||

| IL-6 day −2 (log2, pg/mL) | 105 | 1.27 (1.02–1.59) | 1.30 (1.03–1.63) |

| p = .033 | p = .026 | ||

| IL-6 day −1 (log2, pg/mL) | 115 | 1.51 (1.22–1.87) | 1.57 (1.26–1.97) |

| p < .001 | p < .001 | ||

| IL-6 day 0 (log2, pg/mL) | 122 | 1.36 (0.97–1.91) | 1.39 (1.03–1.88) |

| p = .077 | p = .032 | ||

| IGFBP-1 day −2 (log2, μg/L) | 107 | 1.05 (0.83–1.32) | 1.10 (0.84–1.44) |

| p = .687 | p = .476 | ||

| IGFBP-1 day −1 (log2, μg/L) | 117 | 1.62 (1.11–2.36) | 1.74 (1.19–2.53) |

| p = .013 | p = .004 | ||

| IGFBP-1 day 0 (log2, μg/L) | 124 | 1.47 (1.15–1.87) | 1.51 (1.20–1.89) |

| p = .002 | p < .001 |

Odds-ratios (OR) per 1 unit increase are presented.

GA, gestational age; CI, confidence interval; IL-6, interleukin-6; IGFBP-1, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1.

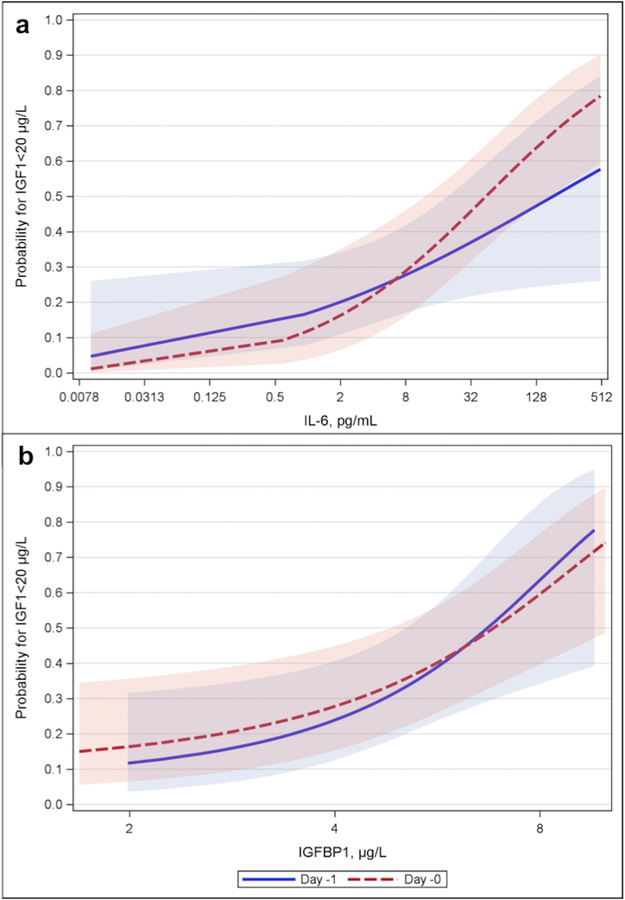

On the continuous scale and correlating simultaneously taken measurements, IL-6 was not statistically significantly associated with IGF-1 levels among treated infants on active, non-active nor among study controls, supplemental Table A.2. However, higher IL-6 levels at day −2 and day −1 before the actual IGF-1 value were associated with higher risk for IGF-1 < 20 μg/L, Table 2 and Fig. 2a. Gestational age adjusted OR per doubled value (log2 scale) IL-6, for example an increase from 3 to 6 or from 25 to 50, in pg/mL one day before sampled IGF-1 was 1.57 (95% CI 1.26–1.97), p < .001.

Fig. 2.

Estimated probability for IGF1 < 20 μg/L. a: For different values of interleukin-6 (IL-6, log2 transformation of pg/mL) on day −2 and − 1 b: For different values of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1, log2 transformation of μg/L) on day −1 and 0.

Higher levels of IGFBP-1 at day 0 and −1 were also associated with higher risk for IGF-1 levels < 20 μg/L, Table 2 and Fig. 2b. There was a statistically significant negative correlation for simultaneously collected values of IGFBP-1 and IGF-1 for controls during periods before and after day 14, supplemental Table A.2, but no corresponding association was seen among treated infants.

3.3. Clinical events during active treatment

All occasions with confirmed or suspected infection during active treatment (n = 9) was related in time to IGF-1 levels < 20 μg/L. One adverse event of discolored fingertips after peripheral arterial catheterization was not associated with any drop in serum level of IGF-1. IGF-1 was < 20 μg/L in serum on 16 occasions during active treatment. Five occasions were related in time to confirmed infection, four to suspected infection (elevated CRP or clinical signs reported as related to suspected infection in the record of adverse events) and on one occasion IGF-1 in serum dropped to < 20 μg/L after an IV line had been accidentally placed in pleura. On six occasions there were no association in time between IGF-1 < 20 μg/L during active treatment and adverse events related to infection or inflammation. During this study there was one incident with interruption of the infusion. Serum IGF-1 taken 12 h after reconnection and continued treatment did not demonstrate a change in IGF-1 level compared to before the incident.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that low (< 20 μg/L) serum levels of IGF-1 during continuous, longitudinal IV infusion of rhIGF-1/ rhIGFBP-3 in extremely preterm infants was preceded by high levels of IL-6, and IGBP-1.

The analyses were limited by the small sample of 19 infants (9 treated with rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3). However, the longitudinal design and high resolution of daily sampling is unique in this patient cohort and enabled investigation of correlation between biomarkers during the time-period prior to the decreased IGF-1 levels. Even though the analysis method would have allowed for simultaneous measurement of other cytokines, IL-6 was the only cytokine that was a priori decided and analyzed in the blood samples from this study. The analyses performed within this manuscript should be seen as hypotheses building and exploratory, providing knowledge to future studies, rather than confirmatory.

In section D of the phase 2 trial a standardized dose of rhIGF-1/ rhIGFBP-3 was used with the intention of maintaining serum IGF-1 levels within a higher range of 28–109 μg/L. Only 28 of 61 treated patients had ≥70% of IGF-1 levels within the predefined higher target range [12]. This might have been related to compliance and technical issues of continuous IV drug administration but our results highlight that IGF-1 metabolism and concurrent inflammatory factors also might be of importance. Further understanding of factors associated with IGF-1 levels will improve the potential of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 treatment.

Association between inflammatory biomarkers and IGF-1 levels has been previously demonstrated in a physiological setting. In a study of IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in preterm infants, there was a negative correlation between endogenous levels of IGF-1 and IL-6 between 5 and 8 weeks after birth [15]. There are complex interactions between IGF-1 and the immune system. Pro-inflammatory cytokines seem to dampen the effects of IGF-1 through intracellular crosstalk of various types. For example, the signaling components mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), specifically extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK) 1/2 are shared in IGF-1 receptor activated pathways and pro-inflammatory signaling pathways [14,21]. In vitro studies of cancer cells have demonstrated other pathways where cytokines may inhibit the actions of IGF-1 [22,23]. IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines have been previously shown to increase the production of IGFBP-1 [24,25]. The mechanism through which increased levels of IL-6 and IGFBP-1 may lead to lower levels of IGF-1 is not clear. In our study, high levels of IL-6 were found two days before levels of IGF-1 decreased below 20 μg/L, preceding high levels of IGFBP-1 found one day before low levels of IGF-1 during continuous infusion of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3. A recent review suggest micro RNA as possible link between inflammation and growth factors in intrauterine growth restriction as well as in chronic inflammatory diseases in childhood [26]. The rapid changes are not likely to be related to gene expression in this population that has limited endogenous production of IGF-1. Instead we speculate that the findings are associated with clearance of IGF-1 from the vascular compartment. Children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis have increased IL-6 production and low levels of IGF-1 [27]. It has been proposed that IL-6 induces proteolysis of the binding protein and thereby increases clearance of IGF-1 [28]. Our findings suggest that a potential effect of IL-6 could be mediated through IGFBP-1. IGF-1 forms a smaller complex with IGFBP-1 compared to with IGFBP-3 [29], and the IGF-1/IGFBP-1 complex can leave the vascular compartment [30]. It has also been suggested that the IGF-1/IGFBP1 complex might interact with glomerular receptors and increase glomerular capillary permeability [31]. There are no studies in extremely preterm infants to confirm an association between increased levels of IGFBP-1 and increased clearance of IGF-1 from the vascular compartment.

A recent publication examined correlations between high and low levels of IGF-1 and IGFBP-1 with 25 different proteins in extremely preterm infants [32]. The study demonstrated association between levels of IGFBP-1 and IL-6 at all measured days and association between low levels of IGF-1 and high levels of IL-6 on postnatal day 21. In growth restricted infants, elevated levels of IGFBP-1 and IL-6 have been demonstrated in the placenta [18]. In the study by Street et al. there was also a positive correlation between IL-6 and IGFBP-1 in both placenta and cord blood. A study of preterm infants born before the 28th week of gestation demonstrated higher levels of IL-6 and IGFBP-1 at postnatal day 14 in small for gestational age infants compared to appropriate for gestational age infants [33]. Association between levels of IL-6, IGFBP-1 and IGF-1 have also been demonstrated in other clinical settings. A study of adult patients with sepsis showed that levels of IGF-1 were inversely associated with levels of IL-6 [34]. In children with meningococcal sepsis low levels of IGF-1 and high levels of IL-6 and IGFBP-1 were associated with poor outcome [35]. The results from previous studies support the hypothesis that infection and inflammation are associated with IGF-1 metabolism. In our study a drop in IGF-1 to below 20 μg/L was associated in time with clinical signs of infection or inflammation in 9 of 16 occasions.

Infection, stress and catabolism may affect the levels of IL-6 in this preterm population. Experimental studies have demonstrated that acute psychological stress increases the levels of circulating IL-6 in adults [36]. Marchini et al. demonstrated an association between increasing fetal stress, low levels of IGF-1 and high levels of IL-6 and IGFBP-1 in cord blood from term infants [37]. In very preterm infants appropriate for gestational age, levels of IL-6 in cord blood had a negative correlation with IGF-1 and a positive correlation with both low and high phosphorylated forms of IGFBP-1 [16]. A catabolic state is common in preterm infants, in part due to high nutritional demands and difficulties to provide sufficient nutrients, and is also related to low levels of IGF-1. A negative correlation between IL-6 and IGF-1 has been observed in relation to severe starvation. In a study of children suffering from severe malnutrition in Uganda, low levels of IGF-1 and high levels of IL-6 was demonstrated at baseline. After two weeks of nutritional intervention, IGF-1 increased 3-fold and IL-6 decreased 6-fold [38]. Similarly, Prendergast et al. showed a negative correlation between IGF-1 and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, in growth stunted children [39].

In line with our results, an inhibitory effect of IL-6 on IGF-1 expression is supported by results from animal studies. Mice overexpressing IL-6 suffer from impaired postnatal growth and lower IGF-1 levels. Administration of antibodies neutralizing the IL-6 receptor improved postnatal growth, and administration of recombinant IL-6 reduced IGF-1 levels [27]. The same study also demonstrated a negative correlation between IGF-1 and IL-6 in children with systemic juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. In a rat model of necrotizing enterocolitis, intervention with enteral IGF-1 reduced levels of IL-6 and incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis [40]. IGF-1 is an important factor in preterm development and increased understanding of the complex interactions between immune processes and IGF-1 has the potential to optimize utilization and treatments.

5. Conclusions

Results from this study increase the understanding of the feasibility of longitudinal infusion of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 in a population of extremely preterm infants. The association between elevated IL-6 and low levels of IGF-1 needs to be further established before any recommendation in dose alteration based on IL-6 levels can be made. Additional work is required to determine if infection and/or inflammatory processes suppress serum IGF-1 levels despite ongoing continuous infusion with rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3. The results demonstrate a need to further evaluate IGF-1 metabolism in this population to establish the physiological impact of our findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the infants and their families who participated in this study. We thank the research nurses Camilla Halzius, Margareta Gebka and Ann-Cathrine Berg along with other contributors. We also thank Norman Barton and Alexandra Mangili from Shire for their support.

Funding

This study was funded by Premacure AB, a member of the Shire Group of Companies, and by the PREVENTROP FP7 Consortium [grant number 305485]; the Swedish Medical Research Council [grant number 2016-01131]; the Gothenburg Medical Society, and Swedish Government grants under the ALF agreement [grant number ALFGBG-717971].

Abbreviations:

- ROP

retinopathy of prematurity

- GA

gestational age

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- IGFBP-3

insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3

- IGFBP-1

insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IV

intravenous

- rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3

recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1/ recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3

- SD

standard deviation

- IQR

inter-quartile range

Footnotes

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov ().

Declaration of Competing Interest

IH-P, DL and AH hold stock/stock options in Premalux AB, and have received consulting fees from Shire PLC. BH has received consulting fees from Premacure AB and Shire PLC, and grant/research support from Baxter. JB holds stock in Premalux AB.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ghir.2019.11.001.

References

- [1].Langford K, Nicolaides K, Miell JP, Maternal and fetal insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in the second and third trimesters of human pregnancy, Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl 13 (1998) 1389–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hellström A, Ley D, Hansen-Pupp I, Hallberg B, Löfqvist C, van Marter L, van Weissenbruch M, Ramenghi LA, Beardsall K, Dunger D, Hård A-L, Smith LEH, Insulin-like growth factor 1 has multisystem effects on foetal and preterm infant development, Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor 105 (2016) 576–586, 10.1111/apa.13350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lineham JD, Smith RM, Dahlenburg GW, King RA, Haslam RR, Stuart MC, Faull L, Circulating insulin-like growth factor I levels in newborn premature and full-term infants followed longitudinally, Early Hum. Dev 13 (1986) 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hansen-Pupp I, Löfqvist C, Polberger S, Niklasson A, Fellman V, Hellström A, Ley D, Influence of insulin-like growth factor I and nutrition during phases of postnatal growth in very preterm infants, Pediatr. Res 69 (2011) 448–453, 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182115000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Löfqvist C, Hellgren G, Niklasson A, Engström E, Ley D, Hansen-Pupp I, WINROP Consortium, Low postnatal serum IGF-I levels are associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD): Low IGF-I and BPD, Acta Paediatr. 101 (2012) 1211–1216, 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hellström A, Engström E, Hård A-L, Albertsson-Wikland K, Carlsson B, Niklasson A, Löfqvist C, Svensson E, Holm S, Ewald U, Holmström G, Smith LEH, Postnatal serum insulin-like growth factor I deficiency is associated with retinopathy of prematurity and other complications of premature birth, Pediatrics. 112 (2003) 1016–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hansen-Pupp I, Hövel H, Löfqvist C, Hellström-Westas L, Fellman V, Hüppi PS, Hellström A, Ley D, Circulatory insulin-like growth factor-I and brain volumes in relation to neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm infants, Pediatr. Res 74 (2013) 564–569, 10.1038/pr.2013.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kajantie E, Dunkel L, Rutanen E-M, Seppälä M, Koistinen R, Sarnesto A, Andersson S, IGF-I, IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-3, phosphoisoforms of IGFBP-1, and postnatal growth in very low birth weight infants, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 87 (2002) 2171–2179, 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ley D, Hansen-Pupp I, Niklasson A, Domellöf M, Friberg LE, Borg J, Löfqvist C, Hellgren G, Smith LEH, Hård A-L, Hellström A, Longitudinal infusion of a complex of insulin-like growth factor-I and IGF-binding protein-3 in five preterm infants: pharmacokinetics and short-term safety, Pediatr. Res 73 (2013) 68–74, 10.1038/pr.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hansen-Pupp I, Hellström A, Hamdani M, Tocoian A, Kreher NC, Ley D, Hallberg B, Continuous longitudinal infusion of rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 in extremely preterm infants: evaluation of feasibility in a phase II study, Growth Horm. IGF Res. Off. J. Growth Horm. Res. Soc. Int. IGF Res. Soc 36 (2017) 44–51, 10.1016/j.ghir.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hellstrom A, Ley D, Hallberg B, Lofqvist C, Hansen-Pupp I, Ramenghi LA, Borg J, Smith LEH, Hard A-L, IGF-1 as a drug for preterm infants: a step-wise clinical development, Curr. Pharm. Des 23 (2017) 5964–5970, 10.2174/1381612823666171002114545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ley D, Hallberg B, Hansen-Pupp I, Dani C, Ramenghi LA, Marlow N, Beardsall K, Bhatti F, Dunger D, Higginson JD, Mahaveer A, Mezu-Ndubuisi OJ, Reynolds P, Giannantonio C, van Weissenbruch M, Barton N, Tocoian A, Hamdani M, Jochim E, Mangili A, Chung J-K, Turner MA, Smith LEH, Hellström A, study team, rhIGF-1/rhIGFBP-3 in preterm infants: a phase 2 randomized controlled trial, J. Pediatr 206 (2019), 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.10.033 (56–65.e8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee PD, Giudice LC, Conover CA, Powell DR, Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1: recent findings and new directions, Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. N. Y. N 216 (1997) 319–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].McCusker RH, Strle K, Broussard SR, Dantzer R, Bluthé R, Kelley KW, Chapter 7 -crosstalk between insulin-like growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines, in: Ader R (Ed.), Psychoneuroimmunology, Fourth ed., Academic Press, Burlington, 2007, pp. 171–191, , 10.1016/B978-012088576-3/50011-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hellgren G, Löfqvist C, Hansen-Pupp I, Gram M, Smith LE, Ley D, Hellström A, Increased postnatal concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with reduced IGF-I levels and retinopathy of prematurity, Growth Horm. IGF Res. Off. J. Growth Horm. Res. Soc. Int. IGF Res. Soc 39 (2018) 19–24, 10.1016/j.ghir.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hansen-Pupp I, Hellström-Westas L, Cilio CM, Andersson S, Fellman V, Ley D, Inflammation at birth and the insulin-like growth factor system in very preterm infants, Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor 96 (2007) 830–836, 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].MacRae VE, Wong SC, Farquharson C, Ahmed SF, Cytokine actions in growth disorders associated with pediatric chronic inflammatory diseases (review), Int. J. Mol. Med 18 (2006) 1011–1018, 10.3892/ijmm.18.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Street ME, Seghini P, Fieni S, Ziveri MA, Volta C, Martorana D, Viani I, Gramellini D, Bernasconi S, Changes in interleukin-6 and IGF system and their relationships in placenta and cord blood in newborns with fetal growth restriction compared with controls, Eur. J. Endocrinol 155 (2006) 567–574, 10.1530/eje.1.02251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Löfqvist C, Niklasson A, Engström E, Friberg LE, Camacho-Hübner C, Ley D, Borg J, Smith LEH, Hellström A, A pharmacokinetic and dosing study of intravenous insulin-like growth factor-I and IGF-binding protein-3 complex to preterm infants, Pediatr. Res 65 (2009) 574–579, 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819d9e8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Blum WF, Breier BH, Radioimmunoassays for IGFs and IGFBPs, Growth Regul. 4 (Suppl. 1) (1994) 11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].O’Connor JC, McCusker RH, Strle K, Johnson RW, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Regulation of IGF-I function by proinflammatory cytokines: at the interface of immunology and endocrinology, Cell. Immunol 252 (2008) 91–110, 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shen WH, Jackson ST, Broussard SR, McCusker RH, Strle K, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, IL-1beta suppresses prolonged Akt activation and expression of E2F-1 and cyclin A in breast cancer cells, J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 (172) (2004) 7272–7281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shen WH, Yin Y, Broussard SR, McCusker RH, Freund GG, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits cyclin a expression and retinoblastoma hyperphosphorylation triggered by insulin-like growth factor-I induction of new E2F-1 synthesis, J. Biol. Chem 279 (2004) 7438–7446, 10.1074/jbc.M310264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Samstein B, Hoimes ML, Fan J, Frost RA, Gelato MC, Lang CH, IL-6 stimulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP)-1 production, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 228 (1996) 611–615, 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Lang CH, Stimulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 synthesis by interleukin-1beta: requirement of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, Endocrinology 141 (2000) 3156–3164, 10.1210/endo.141.9.7641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cirillo F, Lazzeroni P, Catellani C, Sartori C, Amarri S, Street ME, MicroRNAs link chronic inflammation in childhood to growth impairment and insulin-resistance, Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 39 (2018) 1–18, 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].De Benedetti F, Alonzi T, Moretta A, Lazzaro D, Costa P, Poli V, Martini A, Ciliberto G, Fattori E, Interleukin 6 causes growth impairment in transgenic mice through a decrease in insulin-like growth factor-I. A model for stunted growth in children with chronic inflammation, J. Clin. Invest 99 (1997) 643–650, 10.1172/JCI119207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].De Benedetti F, Meazza C, Oliveri M, Pignatti P, Vivarelli M, Alonzi T, Fattori E, Garrone S, Barreca A, Martini A, Effect of IL-6 on IGF binding protein-3: a study in IL-6 transgenic mice and in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Endocrinology. 142 (2001) 4818–4826, 10.1210/endo.142.11.8511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Drop SL, Schuller AG, Lindenbergh-Kortleve DJ, Groffen C, Brinkman A, Zwarthoff EC, Structural aspects of the IGFBP family, Growth Regul. 2 (1992) 69–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hodgkinson SC, Spencer GSG, Bass JJ, Davis SR, Gluckman PD, Distribution of circulating insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) into tissues, Endocrinology 129 (1991) 2085–2093, 10.1210/endo-129-4-2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Laviades C, Gil MJ, Monreal I, González A, Díez J, Is the tissue availability of circulating insulin-like growth factor I involved in organ damage and glucose regulation in hypertension? J. Hypertens 15 (1997) 1159–1165, 10.1097/00004872-199715100-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Leviton A, Allred EN, Fichorova RN, VanderVeen DK, O’Shea TM, Kuban K, Dammann O, ELGAN study investigators, early postnatal IGF-1 and IGFBP-1 blood levels in extremely preterm infants: relationships with indicators of placental insufficiency and with systemic inflammation, Am. J. Perinatol (2019), 10.1055/s-0038-1677472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].McElrath TF, Allred EN, Van Marter L, Fichorova RN, Leviton A, ELGAN Study Investigators, Perinatal systemic inflammatory responses of growth-restricted preterm newborns, Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor 102 (2013), 10.1111/apa.12339 (e439–442). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Papastathi C, Mavrommatis A, Mentzelopoulos S, Konstandelou E, Alevizaki M, Zakynthinos S, Insulin-like growth factor I and its binding protein 3 in sepsis, Growth Horm. IGF Res. Off. J. Growth Horm. Res. Soc. Int. IGF Res. Soc 23 (2013) 98–104, 10.1016/j.ghir.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].de Groof F, Joosten KFM, A J, Janssen MJL, de Kleijn ED, Hazelzet JA, Hop WCJ, Uitterlinden P, Doorn J. van, Hokken-Koelega ACS, Acute stress response in children with meningococcal sepsis: important differences in the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I axis between nonsurvivors and survivors, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 87 (2002) 3118–3124, 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y, The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis, Brain Behav. Immun 21 (2007) 901–912, 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Marchini G, Hagenäs L, Kocoska-Maras L, Berggren V, Hansson L-O, Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 and interleukin-6 are markers of fetal stress during parturition at term gestation, J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. JPEM 18 (2005) 777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bartz S, Mody A, Hornik C, Bain J, Muehlbauer M, Kiyimba T, Kiboneka E, Stevens R, Bartlett J, St Peter JV, Newgard CB, Freemark M, Severe acute malnutrition in childhood: hormonal and metabolic status at presentation, response to treatment, and predictors of mortality, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 99 (2014) 2128–2137, 10.1210/jc.2013-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Prendergast AJ, Rukobo S, Chasekwa B, Mutasa K, Ntozini R, Mbuya MNN, Jones A, Moulton LH, Stoltzfus RJ, Humphrey JH, Stunting is characterized by chronic inflammation in Zimbabwean infants, PLoS One 9 (2014) e86928, , 10.1371/journal.pone.0086928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tian F, Liu G-R, Li N, Yuan G, Insulin-like growth factor I reduces the occurrence of necrotizing enterocolitis by reducing inflammatory response and protecting intestinal mucosal barrier in neonatal rats model, Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci 21 (2017) 4711–4719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.