Introduction

The relevance and impact of human subject research on clinical practice depends on whether the study population reflects the age distribution and health characteristic profiles of the general population. Older adults with a cancer are disproportionately underrepresented in clinical trials and fewer data are available to assess the risks and benefits of cancer treatments, particularly adverse effects on functional outcomes and quality of life1. Furthermore, there is a lack of understanding of how the underlying biologic processes of aging affect tolerance of cancer treatment and survival outcomes. In 2010, the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) outlined the following gaps in generating high quality research in older adults with cancer: 1) clinical measures most relevant to older adults are rarely incorporated into oncology clinical trials; 2) biological and physiological markers of aging are inconsistently included in oncology research; 3) a need for more studies of vulnerable older adults and/or those aged 75 years or older; and 4) limited research infrastructure to support collaborations between geriatrics and oncology.2 Almost a decade later, CARG has been awarded a five-year R21/R33 grant to develop a sustainable national research infrastructure to create and support significant and innovative projects at the interface of cancer and aging that address the four gaps that were initially identified. As a component of this infrastructure award, interactive Cores were developed to facilitate and support aging-related research in oncology. The purpose of this perspective is to summarize the mission and proposed function, process and procedures for Core 1: Clinical and Biological Measures of Aging; and to provide examples of how the Core will facilitate research in geriatric oncology.

Mission

The mission of Core 1 is to accelerate the pace of discovery and collaboration between investigators by providing resources to inform the use of appropriate clinical and biological measures of aging within the context of cancer and aging research. Validated clinical assessment tools to evaluate geriatric domains, such as physical function and cognitive status, are feasible to incorporate into oncology clinical trials (Table 1). 3,4 Various clinical measures of aging also have demonstrated association with cancer-related outcomes.2 For example, a history of falls is associated with increased chemotherapy toxicity;5 similarly, impairment in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) have been associated with worse overall survival in older adults with advanced non-small cell lung cancer.6 These measures also can serve as important outcomes that can inform treatment tolerance and survivorship. These endpoints may be as relevant, if not more so, than traditional oncology endpoints for older adults with cancer.7,8 However, at the present time, relatively few therapeutic trials in oncology report on geriatric-relevant issues, such as functional decline or cognition, as endpoints9,10. Biological markers of aging also may add important information regarding the physiologic age of a patient and provide additional insight as to how cancer treatment may accelerate the aging process.11

Table 1:

Examples of clinical and biological measures

| Clinical measures | |

| Nutrition | Mini Nutritional Assessment13 |

| Cognition | Mini-Cog14 Mini-Mental State Examination15 Montreal Cognitive Assessment16 |

| Physical Function | Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living17 Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living18 Short Physical Performance Battery19 |

| Biological measures | |

| Chronic inflammatory Markers | IL-6, IL-1Rα, TNFα20–22 |

| Coagulation/Vascular/Immune Markers | D-dimer and fibrinogen23, VCAM24, PMN/lymphocyte ratio25, peripheral blood bioenergetics 26 |

| Markers of cellular senescence | p16inka27, senescence-associated secretory phenotype28, telomere length29, DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic clocks30 |

| Body Composition31 | Sarcopenia – Imaging-based32–34, SarcoPRO35,36 |

Abbreviations: IL=Interleukin; TNF=tumor necrosis factor; VCAM=vascular cell adhesion protein; PMN=polymorphonuclear neutrophil; DNA= deoxyribonucleic acid

Function

The workforce shortage of providers who have expertise in geriatrics is contributing to a crisis in cancer care.1 Provision of quality clinical care requires geriatric expertise and generation of evidence specific to older adults. Rapid progress towards this goal requires collaboration in geriatric oncology research. Therefore, the target audience for Core 1 is broad and designed to reach both new and established investigators interested in aging research as well as those not familiar with geriatric oncology, to foster collaboration and to grow the research base in this area. Developing mentorship infrastructure for the next generation of researchers at the intersection of aging and cancer is also an important priority of the grant. Core 1 will cultivate opportunities for mentorship and advance career development for junior investigators by connecting them to experts in the field and providing peer-to-peer mentoring and opportunities for collaboration. For established researchers in aging and cancer research as well as researchers in other fields, Core 1 will facilitate opportunities for networking that will build stronger and broader transdisciplinary and trans-specialty collaborations. This goal is timely, as supported by a new NIH policy, effective January 25, 2019, that mandates the inclusion of older adults into all NIH-supported research involving human subjects when scientifically appropriate.12 This mandate presents an opportunity for the Core to enhance rigor of scientific projects by providing support for investigators who will be conducting disease-based research and will likely need guidance on recruitment and assessment of older adults in their studies.

Resources, Processes, and Procedures

The goal of Core 1 is to provide resources and expertise in clinical measures and biological markers of aging for researchers across disciplines. Incorporation of these measures in research design is necessary for high-quality research in older adults with cancer2. At the broadest level, Core 1 will develop two types of resources. The first type of resource will include informational-enduring materials that can be accessed from the CARG website. The second type of resource will include interactions with appropriately matched experts in the relevant domain, measurement area, and/or cancer type of interest, in a way that is tailored to the needs of the investigator. The goal of Core 1 will be achieved in multiple phases. The initial phases will focus on developing and updating enduring materials/resources to be readily accessed by researchers followed by pilot testing strategies to offer an “interactive” consultative resource. Through-out the phases, the goal will be to develop strategies that align with existing resources in order to build a process that is feasible and sustainable.

Informational-Enduring Resource

Creating informational-enduring materials will be an integral component of Core 1. This will include an inventory of measures related to geriatric assessment domains and biological measures. Beyond providing the rationale, scoring, interpretation and key references for the measure, the resource also will contain recommendations for implementation protocols and data collection. Table 1 provides examples of clinical and biological resources that will be available. This resource, once built, will be accessible by a broad audience. This self-service resource is intended to serve as a “one-stop” place for obtaining comprehensive information on clinical and biological assessment tools for implementation into oncology research.

As the interactive-consultative resource is developed, the aspirational goal is to connect researchers with experts who have experience with the measures. A limitation for many junior investigators is the lack of access to pilot data. Cross-referencing measures with existing datasets and the responsible principal investigator likely will help accelerate opportunities and collaborations for new and existing investigators. In order to sustain this process, we will create a database of consultants, organized by expertise (i.e. cognitive function, physical function), who are willing to provide advice to other researchers. We will start with existing CARG members and aim to build the repertoire of consultants by asking researchers who are requesting the Core’s service to agree to be a consultant for others. Dr. Arti Hurria, who frequently reiterated the importance of researchers in our community “paying it forward”, promoted this idea at the inaugural meeting. The added value to consultants would be opportunities to foster new collaborations with colleagues who have similar interests and may potentially lead to multicenter studies.

Interactive-Consultative Resource

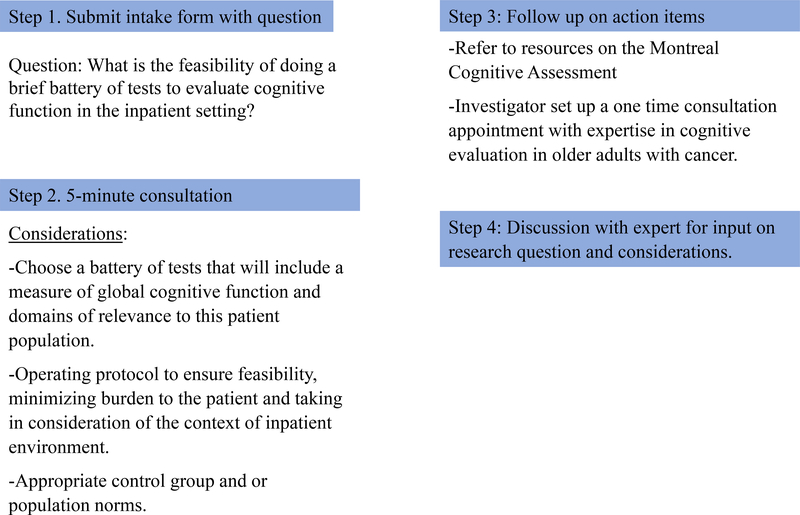

The next phases of Core 1 will be to work with core leaders to develop and iteratively test processes and procedures for the interactive-consultative resources with continued feedback from key stakeholders and users. The goal is to provide two levels of services tailored to the needs of the researcher. Table 2 provides an example of considerations of the processes, procedures, and plan for sustainability for the interactive resource. For Level 1, we plan to incorporate existing resources and processes from CARG into this component. For example, CARG will use the “5- minute consultation” as a means of acquiring initial input on a research question. A new feature for this process will be the addition of a screening process that allows CARG to schedule appropriate expertise for the research question. For some investigators, additional needs, including one-on-one expert consultation and connection with other Cores within the infrastructure such as biostatistics, may be identified during the “5-minute consultation”. Building upon this initial brief consultation, additional considerations may include further interactions with an expert at a “one-time consultation” versus multiple consultation meetings. The sustainability plan for Level 2 will likely be more complex and may require a fee-for-service process. Figure 1 provides an example of how a hypothetical investigator seeking to assess cognitive function in older patients receiving intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia can use the services facilitated by Core 1.

Table 2.

Example of considerations for processes, procedures and plan for sustainability for the interactive resource

| Processes/Steps | Objective(s) | Procedures/Activities | Sustainability Plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: All investigators | |||

| Step 1: Screening | 1. To understand/clarify research question and specific brief consultation request. 2. To identify appropriate CARG expert to match with investigator to ensure efficiency. (Make sure appropriate person attends CARG calls). |

1. Initial consult intake form on CARG website. 2. Contact made by CARG team to clarify research questions and plan for a date/time for “5-Minute Consultation”. Timeline: approximately 2 weeks from receipt of initial intake. 3. Time to “5-Minute Consultation” may vary based on needs and urgency. |

No fees will be charged. Staffing will be done through the grant infrastructure. |

| Step 2: “5-Minute Consultation” | 1. To provide high level feedback and comments on the study concept and aims related to biologic and clinical measures. 2. To provide recommendations on the next steps. |

1. Recommendations may point to a need for consultation with an individual or group within CARG (may involve other CORES) on the following: a. Design b. Selection of measurements c. Implementation of protocols d. Statistical analysis |

No fees will be charged. Staffing will be reliant on existing CARG members and willingness to be the expert for a specific request. |

| Step 3: Follow up on next steps depends on recommendations from “5-Minute Consultation” | 1. To provide follow up so that we can close the initial request. 2. To ensure that the investigator received the appropriate information, contacts, and connections. |

1. Staff will follow up and provide an email contact and specific next steps based on recommendations from the “5-Minute Consultation”. Timeline: within 1 week after the “5-Minute Consultation” | No fees will be charged. Staffing will be done through the grant infrastructure. |

| Level 2: Determined by needs and resources available | |||

| Consultation with an individual/group expert (one time) | 1. To provide opportunity for further discussions. 2. To provide opportunity to request access to preliminary data to generate power analysis and feasibility data for new investigators. |

1. Investigator will schedule consultation with expert. 2. Advice provided specific to research question. |

Build in request for a consultation fee for individuals with grant funding. Willingness to serve as a future “expert” for individuals requiring consultation- “pay it forward” |

| Consultation with an individual/group expert (ongoing for a grant period and length of involvement to be individualized) | Same as above except for a longer duration. | 1. Establish framework for collaboration 2. Establish goals of collaboration 3. Provide timeline/deliverables 4. Staff to track collaboration and activities |

Writing the consultant into the grant will be expected unless an exception made. |

Figure 1.

An example of how a hypothetical investigator seeking to assess cognitive function in older patients receiving intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia can use the services facilitated by Core 1.

Conclusion

Clinical and biological measures of aging are valuable and relevant assessment variables in oncology research. Given the limited number of oncology researchers with aging expertise and the dire need for additional knowledge in this area, it is essential to facilitate and support the needs of researchers interested in incorporating geriatrics into oncology research in a time efficient way. The mission of Core 1, to provide resources and expertise in clinical and biological measures of aging for investigators across disciplines, is a key component to advancing the field of geriatric oncology and ultimately improving the evidence base for caring for older adults with cancer.

Acknowledgments

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Klepin was funded by the CARG R21 grant (R21 AG059206).

References

- 1.Naylor MD, Cohen HJ, Hurria A. Improving the Quality of Cancer Care in an Aging Population. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 2013;310:1795–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale W, Mohile SG, Eldadah BA, et al. Biological, clinical, and psychosocial correlates at the interface of cancer and aging research. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:581–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer 2005;104:1998–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, et al. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2011;29:1290–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2011;29:3457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maione P, Perrone F, Gallo C, et al. Pretreatment quality of life and functional status assessment significantly predict survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: a prognostic analysis of the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurria A, Dale W, Mooney M, et al. Designing therapeutic clinical trials for older and frail adults with cancer: U13 conference recommendations. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2014;32:2587–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. The New England journal of medicine 2002;346:1061–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brain EG, Mertens C, Girre V, et al. Impact of liposomal doxorubicin-based adjuvant chemotherapy on autonomy in women over 70 with hormone-receptor-negative breast carcinoma: A French Geriatric Oncology Group (GERICO) phase II multicentre trial. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 2011;80:160–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildiers H, Mauer M, Pallis A, et al. End points and trial design in geriatric oncology research: a joint European organisation for research and treatment of cancer–Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology–International Society Of Geriatric Oncology position article. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2013;31:3711–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurria A, Jones L, Muss HB. Cancer Treatment as an Accelerated Aging Process: Assessment, Biomarkers, and Interventions. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book / ASCO American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting 2016;35:e516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inclusion Across the Lifespan - Policy Implementation: NIH Inclusion Across the Lifespan in Research Involving Human Subjects 2019. (Accessed June 4, 2019, at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/lifespan/lifespan.htm.)

- 13.Vellas B, Guigoz Y, Garry PJ, et al. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition 1999;15:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1451–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies Of Illness In The Aged. The Index Of Adl: A Standardized Measure Of Biological And Psychosocial Function. Jama 1963;185:914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puthoff ML. Outcome measures in cardiopulmonary physical therapy: short physical performance battery. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2008;19:17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen HJ, Harris T, Pieper CF. Coagulation and activation of inflammatory pathways in the development of functional decline and mortality in the elderly. The American journal of medicine 2003;114:180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pomykala KL, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. The association between pro-inflammatory cytokines, regional cerebral metabolism, and cognitive complaints following adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Brain imaging and behavior 2013;7:511–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim DW, Chung K, Chung WK, et al. Risk of secondary cancers from scattered radiation during intensity-modulated radiotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiation oncology (London, England) 2014;9:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robson SC, Shephard EG, Kirsch RE. Fibrin degradation product D-dimer induces the synthesis and release of biologically active IL-1 beta, IL-6 and plasminogen activator inhibitors from monocytes in vitro. British journal of haematology 1994;86:322–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moses K, Brandau S. Human neutrophils: Their role in cancer and relation to myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Seminars in immunology 2016;28:187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyrrell DJ, Bharadwaj MS, Van Horn CG, Marsh AP, Nicklas BJ, Molina AJ. Blood-cell bioenergetics are associated with physical function and inflammation in overweight/obese older adults. Experimental gerontology 2015;70:84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Johnson SM, Fedoriw Y, et al. Expression of p16(INK4a) prevents cancer and promotes aging in lymphocytes. Blood 2011;117:3257–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coppe JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS biology 2008;6:2853–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beeharry N, Broccoli D. Telomere dynamics in response to chemotherapy. Current molecular medicine 2005;5:187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horvath S DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome biology 2013;14:R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demark-Wahnefried W, Peterson BL, Winer EP, et al. Changes in weight, body composition, and factors influencing energy balance among premenopausal breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2001;19:2381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mourtzakis M, Prado CMM, Lieffers JR, Reiman T, McCargar LJ, Baracos VE. A practical and precise approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl Physiol Nutr Me 2008;33:997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunne RF, Roussel B, Culakova E, et al. Characterizing cancer cachexia in the geriatric oncology population. J Geriatr Oncol 2019;10:415–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams GR, Deal AM, Muss HB, et al. Frailty and skeletal muscle in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2018;9:68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans CJ, Chiou CF, Fitzgerald KA, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure in sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gewandter JS, Dale W, Magnuson A, et al. Associations between a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure of sarcopenia and falls, functional status, and physical performance in older patients with cancer. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2015;6:433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]