Abstract

Objectives.

To characterize the temporal trajectory of body image disturbance (BID) in patients with surgically treated head and neck cancer (HNC).

Study Design.

Prospective cohort study.

Setting.

Academic medical center.

Subjects and Methods:

Patients with HNC who were undergoing surgery completed the Body Image Scale (BIS), a validated patient-reported outcome measure of BID, pretreatment and 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months posttreatment. Changes in BIS scores (ΔBIS) relative to pretreatment (primary endpoint) were analyzed with a linear mixed model. Associations between demographics, clinical characteristics, psychosocial attributes, and persistently elevated BIS scores and increases in BIS scores ≥5 points relative to pretreatment (secondary endpoints) were analyzed through logistic regression.

Results.

Of the 68 patients, most were male (n = 43), had oral cavity cancer (n = 37), and underwent microvascular reconstruction (n = 45). Relative to baseline, mean ΔBIS scores were elevated at 1 month postoperatively (2.9; 95% CI, 1.3–4.4) and 3 (3.2; 95% CI, 1.5–4.9) and 6 (1.8; 95% CI, 0.02–3.6) months posttreatment before returning to baseline at 9 months posttreatment (0.9; 95% CI, −0.8 to 2.5). Forty-three percent of patients (19 of 44) had persistently elevated BIS scores at 9 months posttreatment relative to baseline, and 51% (31 of 61) experienced an increase in BIS scores ≥5 relative to baseline.

Conclusions.

In this cohort of patients surgically treated for HNC, BID worsens posttreatment before returning to pretreatment (baseline) levels at 9 months posttreatment. However, 4 in 10 patients will experience a protracted course with persistent posttreatment body image concerns, and half will experience a significant increase in BIS scores relative to pretreatment levels.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, body image, disfigurement, survivorship, quality of life, patient reported outcomes

Head and neck cancer (HNC) arises in cosmetically and functionally critical areas. As a result of HNC and its treatment, changes in highly visible and socially significant parts of the body are common.1,2 Disfigurement and impaired smiling, swallowing, and speaking can result in substantial psychosocial morbidity, including depression,3 anxiety,4 suicide,5 and concerns about body image.1,2 When severe, these body image concerns result in body image disturbance (BID), a multidimensional phenomenon characterized by a negative selfperceived change in appearance and/or function.6–8 BID is prevalent in HNC survivors; associated with social isolation, stigmatization, and depression; and can have a devastating negative impact on quality of life.9–11

There are significant gaps in our knowledge of the epidemiology of BID in HNC survivors, even though it is a key component of survivorship care.12 Specifically, because most studies have been cross-sectional in nature,11,13–17 included only short-term follow-up,3,18 or used nonvalidated measures of BID,19 there is a lack of data about the temporal trajectory of, and risk factors for, BID in surgically treated HNC survivors.1,2 It is critical to more fully characterize the longitudinal course of BID in HNC survivors to enhance preoperative counseling and facilitate the delivery of optimally timed preventative and therapeutic interventions targeted to high-risk patients. The objectives of this study are thus (1) to characterize the temporal trajectory of BID in HNC survivors in the first year posttreatment; (2) to identify pretreatment demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics associated with persistent BID following HNC treatment; and (3) to evaluate the association between demographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors and clinically relevant increases in the severity of BID following HNC treatment relative to baseline.

Methods

Study Design

The study utilized a prospective cohort design; the shortterm follow-up for this cohort has been published.18 The current study follows patients through the first year posttreatment (ie, 12 months after completing adjuvant therapy), which is an additional 9 months of analysis relative to the prior study. These additional data allow us to (1) characterize more fully the longitudinal trajectory of BID from the acute posttreatment period to early survivorship and (2) evaluate whether certain subsets of HNC survivors experience different temporal trajectories of BID recovery, thereby enhancing our ability to provide data-driven preoperative counseling to guide the delivery of optimally timed preventative and therapeutic interventions targeted to high-risk patients. The study was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board. Patients were enrolled after providing written informed consent.

Study Participants

Eligibility criteria for the study included (1) ≥18 years of age; (2) diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, or larynx or a cutaneous malignancy of the head and neck; and (3) definitive surgery with or without adjuvant therapy. Patients were excluded due to inability to speak English or distant metastases. Patients were recruited from a multidisciplinary HNC clinic at a single academic medical center. The project coordinator reviewed the electronic medical record to identify potential participants. Those meeting demographic and oncologic inclusion criteria were screened in a dedicated research space within the HNC clinic. Purposive sampling was performed to ensure representation across hypothesized risk factors of age, sex, American Joint Committee on Cancer classification, ablative surgery, and type of reconstruction to enhance the scientific rigor of our approach. Two of the 70 eligible patients who enrolled between May 9, 2017, and February 6, 2018, withdrew before completing the baseline questionnaires, leaving a cohort of 68 with complete baseline (pretreatment) data for analysis. Participants received $15 for enrolling and then up to $60 for completion of follow-up.

The sample size was determined per the precision in estimating mean Body Image Scale (BIS) scores (primary endpoint) at each time point, where precision is measured with the half-width of the corresponding 95% CI. There is a sharp decrease in 95% CI half-width (corresponding to an increase in precision of estimated mean BIS) for increasing sample size, with precision “leveling off” for sample sizes ≥50. To detect absolute differences in BIS for 50 based on a paired t test with an SD (BIS difference) of 3.8 and a 2-sided α of 0.05, we estimated power to be at least 80% to detect a difference in BIS scores of approximately ≥1. —a power estimate that is conservative given our analysis based on linear mixed models regression that borrows strength over time.

Study Procedures

Study measures were completed concurrent with scheduled clinical evaluations prior to treatment (at enrollment), 1 month postoperatively, and after completion of treatment (at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months) on electronic tablets or paper and captured in REDCap.20 Completion of treatment was defined as the date of surgery for those treated by surgery only or the date of completion of adjuvant therapy for those treated with surgery and adjuvant therapy.

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the change in posttreatment BIS scores relative to pretreatment. The BIS is a unidimensional 10-item patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) that assesses the affective, cognitive, and emotional aspects of body image due to cancer or its treatment over the prior 7 days.21 BIS scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater BID.21 The BIS is a validated, reliable PROM and the most commonly used PROM to assess HNC-related BID.22 Although a study suggested some clinical relevance to BIS scores ≥10,23 there has been no rigorous psychometric analysis to establish the minimal clinically important difference between subjects or within subjects over time.

Secondary endpoints included the following: persistent elevation in BIS scores at 9 months posttreatment, which was defined as the time point (9 months) at which the mean ΔBIS scores for the cohort returned to zero, and increases in BIS scores ≥5 at any follow-up time point relative to baseline. In our clinical experience with the BIS to assess therapeutic interventions to treat BID in HNC survivors, changes in BIS scores ≥5 over time are related to clinically meaningful changes in BID and quality of life.

Other Study Variables

Demographics and oncologic characteristics were gathered with study-specific questionnaires. Psychosocial characteristics included measures of HNC-related shame and stigma (Shame and Stigma Scale),24 depression (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Form [PROMIS SF] v1.0–Depression 4a),25 anxiety (PROMIS SF v1.0–Anxiety 4a),25 and social isolation (PROMIS SF v2.0-Social Isolation 4a).26

Statistical Considerations

Data analysis was performed with R 3.5.1 (R Foundation) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Descriptive statistics for demographics, clinical measures, and PROMs included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous measures. Although the distribution of BIS scores is positively skewed, we found the distribution of differences (ΔBIS = posttreatment BIS score – pretreatment BIS score) at each time point to satisfy approximate normality assumptions based on histograms and quantile-quantile plots. We therefore analyzed the collection of ΔBIS scores for all follow-up time points with a linear mixed model, with time (categorical) as a fixed effect and subject-specific random effects to accommodate correlation among ΔBIS scores obtained from the same subject over time. For the BIS instrument only, we treated BIS scores (our primary endpoint) as interval censored in instances of item nonresponse. For example, if a patient answered 9 of 10 BIS questions with a partial score equal to 5, the summed BIS score is treated as being at least 5 and at most 8 (each BIS question contributes at most 3 points to the total score). This affects construction of the likelihood for the mixed model. Specifically, subjects with no item nonresponse contribute a normal density to the likelihood, while subjects with interval-censored scores contribute a difference in normal cumulative distribution functions to the likelihood. Analysis of ΔBIS scores with mixed models was performed through the NLMIXED procedure in SAS, due to the need to specify the likelihood. Mean ΔBIS at each follow-up time point, corresponding 95% CIs, and inference were determined with model-based estimates.

Associations between demographics, clinical characteristics, and psychosocial attributes and study completion status (completed or withdrawn/lost to follow-up) were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum tests or Fisher’s exact tests for continuous or categorical variables as appropriate. Associations between demographics, clinical characteristics, and psychosocial attributes and BID persistence at 9 months posttreatment (defined as ΔBIS9 months >0) were summarized with odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs based on fitted simple logistic regression models. Evaluation of ΔBIS over time for patients with and without persistent BIS was performed via the mixed model approach for interval-censored data as described. Summed scores for all other PROMs were treated as missing if any individual question was missing for that instrument. The same approach was used to evaluate potential risk factors for a large increase in BIS (defined as ΔBIS ≥5 at any follow-up time point).

Results

Study Cohort

Sixty-eight patients were included in the cohort. Table 1 shows the cohort characteristics. During the follow-up period, 15 patients died; 7 were lost to follow-up; and 3 withdrew from the study. The 10 patients who were lost to follow-up or withdrew during the course of the study did not differ significantly in terms of baseline characteristics relative to those who otherwise completed the study (see Supplemental Table S1 in the online version of the article). Completion rates of study questionnaires at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months posttreatment were 98% (62 of 63), 96% (53 of 55), 96% (44 of 46), 100% (44 of 44), and 98% (42 of 43), respectively. The median age was 63 years (IQR, 53–72.3); 63% were male (43 of 68); 54% had oral cavity cancer (37 of 68); and 66% underwent microvascular reconstruction (45 of 68).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, Oncologic, and Psychosocial Characteristics of the Study Cohort (N = 68).

| Characteristic | Median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 63 (53–72.25) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 25 (37) |

| Male | 43 (63) |

| Race | |

| White | 55 (81) |

| African American | 11 (16) |

| Other | 2 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/current partner | 38 (56) |

| Single/separated/divorced/widowed | 30 (44) |

| Body mass index | |

| Underweight | 3 (4) |

| Normal weight | 26 (38) |

| Overweight/Obese | 39 (57) |

| Preoperative mood disorder diagnosis | |

| No | 45 (66) |

| Yes | 23 (34) |

| Preoperative psychiatric medication | |

| No | 45 (66) |

| Yes | 23 (34) |

| Preoperative hypothyroidism | |

| No | 53 (78) |

| Yes | l5 (22) |

| Shame and stigma scale scorea | 16 (10–25) |

| PROMIS SF 4a score | |

| Anxietyb | 10 (7–13) |

| Depressionb | 6 (4–10) |

| Social isolation | 4 (4–9) |

| Tumor location and histology | |

| Oral cavity SCC | 37 (54) |

| Oropharynx SCC/SCC of unknown primary | 8(12) |

| Larynx/hypopharynx SCC | 9(13) |

| Facial cutaneous malignancy | 14(21) |

| pl6 status (oropharynx cases only) | |

| Negative | 3 (38) |

| Positive | 5 (63) |

| AJCC pathologic T classification | |

| 0-2 | 32 (47) |

| 3-4b | 36 (53) |

| Ablative surgeryc | |

| Mandibulectomy | 13(19) |

| Glossectomy | 37 (54) |

| Maxillectomy | 5 (7) |

| Radical tonsillectomy/pharyngectomy | 5 (7) |

| Total laryngectomy | 6 (9) |

| Skin/soft tissue resection and/or parotidectomy | 18 (26) |

| Neck dissection | 60 (88) |

| Other | 6 (9) |

| Reconstructive surgery | |

| None or dermal substitute | 17 (25) |

| Regional flap | 6 (9) |

| Microvascular free flap | 45 (66) |

| Osseous microvascular free flap reconstruction | |

| No | 56 (83) |

| Yes | 12 (18) |

| Adjuvant therapy | |

| None | 26 (41) |

| Radiation | 23 (36) |

| Chemoradiationd | 15 (23) |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; IQR, Interquartile range; PROMIS SF, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Form; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

n = 65 due to missing data (n = 3).

n = 67 due to missing data (n = 1).

n > 68 as patients may belong to > 1 category.

n = 64 due to mortality prior to adjuvant therapy (n = 3) and lost to follow-up (n = 1).

Temporal Trajectory of BID in Surgically Treated HNC Survivors

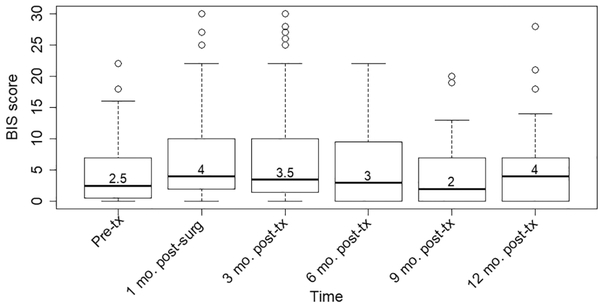

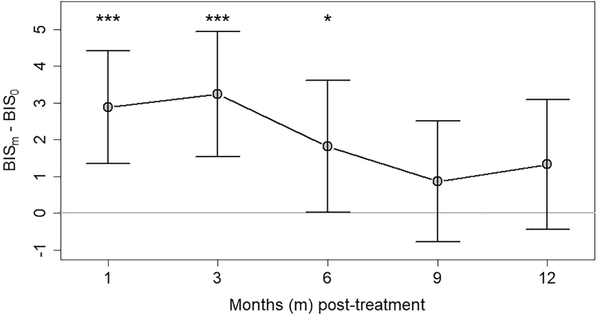

Figure 1 displays the temporal trajectory of BID severity in HNC survivors from pretreatment through the first year posttreatment. The median BIS score was 2.5 (IQR, 0.75–7) at baseline, peaked at 4 (IQR, 2–10) at 1 month postoperatively, decreased gradually until 9 months posttreatment (2; IQR, 0–7), and then increased to 4 (IQR, 0–7) at 12 months posttreatment. The change in the severity of BID over the first year posttreatment relative to pretreatment levels is shown in Figure 2. Relative to pretreatment, mean ΔBIS scores were elevated at 1 month postoperatively (2.9; 95% CI, 1.3–4.4) and 3 (3.2; 95% CI, 1.5–4.9) and 6 (1.8; 95% CI, 0.02–3.6) months posttreatment before returning to baseline levels at 9 (0.9; 95% CI, −0.8 to 2.5) and 12 (1.3; 95% CI, −0.4 to 3.1) months posttreatment.

Figure 1.

Severity of body image disturbance in the first year after treatment for patients with surgically treated head and neck cancer. Severity of body image disturbance (as determined by Body Image Scale [BIS] scores) prior to treatment and 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after completion of treatment for 64, 58, 52, 43, 43, and 41 patients at each time point, respectively. Values are presented as median (thick line), interquartile range (box), upper quartile + 1.5 IQR (whisker), and outliers (circles).

Figure 2.

Temporal trajectory of change in body image disturbance in the first year after treatment for patients with surgically treated head and neck cancer. Change in the severity of body image disturbance following treatment (as determined by the mean change in Body Image Scale [BIS] scores at each posttreatment time point relative to pretreatment baseline) for 60, 53, 44, 44, and 41 patients at each time interval, respectively. Values are presented as mean (95% CI). *P <.05. ***P <.001.

Persistent Posttreatment BID in Surgically Treated HNC Survivors

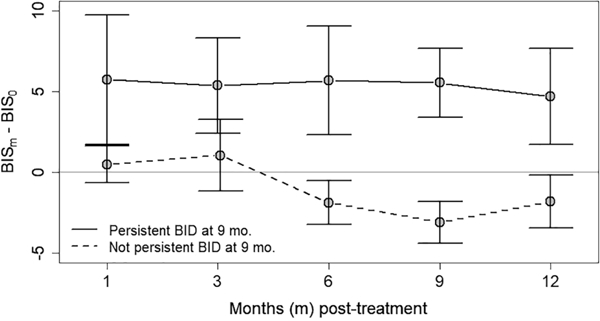

HNC survivors with persistent posttreatment elevations in their BIS scores relative to baseline were identified. At 9 months posttreatment—the time point at which the mean ΔBIS scores of the cohort returned to zero—43% of patients (19 of 44) had persistently elevated BIS scores relative to pretreatment. When the cohort was stratified by persistent elevation in BIS scores at 9 months posttreatment, 2 distinct temporal trajectories of BID severity over time emerged (Figure 3). Those with persistently elevated BIS scores at 9 months posttreatment had a mean ΔBIS score that was elevated at all posttreatment time points relative to baseline: 5.7 (95% CI, 1.7–9.8), 5.4 (95% CI, 2.4–8.3), 5.7 (95% CI, 2.3–9.0), 5.5 (95% CI, 3.4–7.7), and 4.7 (95% CI, 1.7–7.7) for 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months posttreatment, respectively. However, for the HNC survivors who returned to pretreatment BIS scores by 9 months posttreatment, the mean ΔBIS scores never increased from baseline at any time point and actually decreased relative to baseline at 6, 9, and 12 months posttreatment: −1.9 (95% CI, −3.3 to −0.5), −3.1 (95% CI, − 4.4 to −1.8), and −1.8 (95% CI, −3.5 to −0.2). Demographic, clinical, and psychosocial attributes were analyzed to identify risk factors for having persistently elevated BIS scores at 9 months posttreatment relative to baseline (Table 2); however, none had an association.

Figure 3.

Temporal trajectory of change in body image disturbance (BID) for patients with and without persistent BID. Change in the severity of BID following treatment (as determined by the mean change in Body Image Scale [BIS] score at each posttreatment time point relative to pretreatment baseline), stratified by those with or without persistent elevations in BIS scores at 9 months posttreatment.

Table 2.

Risk Factors for Persistent Body Image Disturbance at 9 Months Posttreatment Relative to Baseline (n = 44).

| Characteristic | n | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| ≥40 | 41 | Ref |

| <40 | 3 | 2.82 (0.25–63.69) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 25 | Ref |

| Female | 19 | 1.00 (0.12–1.44) |

| BMI | ||

| Overweight/obese | 29 | Ref |

| Underweight or normal weight | 15 | 1.24 (0.35–4.40) |

| Preoperative mood disorder | ||

| No | 28 | Ref |

| Yes | 16 | 1.04 (0.29–3.60) |

| Preoperative psychiatric medication | ||

| No | 29 | Ref |

| Yes | 15 | 1.24 (0.35–4.40) |

| Preoperative hypothyroidism | ||

| No | 33 | Ref |

| Yes | 11 | 1.13 (0.28–4.51) |

| Shame and Stigma Scale | 42 | 1.01 (0.95–1.06) |

| PROMIS SF 4a | ||

| Anxiety | 43 | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) |

| Depression | 43 | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) |

| Social isolation | 44 | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) |

| AJCC pathologic T classification | ||

| 0-2 | 27 | Ref |

| 3-4b | 17 | 1.91 (0.56–6.73) |

| Reconstruction | ||

| None/dermal substitute | 13 | Ref |

| Regional flap | 3 | 0.58 (0.02–7.68) |

| Microvascular free flap | 28 | 0.88 (0.23–3.36) |

| Osseous flap reconstruction | ||

| No | 38 | Ref |

| Yes | 6 | 3.07 (0.53–24.18) |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| None | 19 | Ref |

| Radiation or chemoradiation | 25 | 1.58 (0.47–5.53) |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; PROMIS SF, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Form.

Increased Severity of Posttreatment BID in HNC Survivors

HNC survivors with large increases in BIS scores relative to baseline pretreatment levels (defined as ≥5 points) were identified. Fifty-one percent of patients (31 of 61) experienced a large increase in the severity of their BID posttreatment relative to pretreatment. Of the analyzed clinical, oncologic, and psychosocial variables (Table 3), only pretreatment body mass index was associated with experiencing a large increase in the severity of BID following treatment (odds ratio, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.01–8.40).

Table 3.

Risk Factors for Experiencing an Increase in Body Image Scale Scores ≥5 Relative to Baseline (n = 61).

| Characteristic | na | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| ≥40 | 58 | Ref |

| <40 | 3 | 0.47 (0.02–5.13) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 37 | Ref |

| Female | 24 | 1.65 (0.59–4.74) |

| BMIb | ||

| Overweight/obese | 35 | Ref |

| Underweight or normal weight | 26 | 2.83 (1.01–8.40) |

| AJCC pathologic T classification | ||

| 0-2 | 32 | Ref |

| 3-4b | 29 | 1.82 (0.66–5.13) |

| Reconstruction | ||

| None/dermal substitute | 15 | Ref |

| Regional flap | 6 | 2.00 (0.28–14.80) |

| Microvascular free flap | 40 | 2.71 (0.81–10.08) |

| Osseous flap reconstruction | ||

| No | 50 | Ref |

| Yes | 11 | 1.90 (0.51–8.01) |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| None | 24 | Ref |

| Radiation or chemoradiation | 36 | 1.48 (0.52–4.23) |

| Shame and Stigma Scale | 59 | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) |

| PROMIS SF 4a | ||

| Anxiety | 60 | 1.10 (0.97–1.26) |

| Depression | 60 | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) |

| Social isolation | 61 | 1.03 (0.88–1.20) |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; PROMIS SF, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Form.

Bold indicates P < .05..

Discussion

BID is a critical issue for HNC survivors because the condition is prevalent and associated with significant psychosocial morbidity and can have a devastating negative impact on quality of life.9–11 This study builds on a landmark cohort study by Krouse et al,19 analyzing adaptation following HNC treatment, and other cross-sectional studies of BID in HNC patients11,13–16 to provide novel, clinically important information about the epidemiology of BID in HNC survivors. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective cohort study following surgically treated HNC survivors for 1 year posttreatment to assess the temporal trajectory of BID with a validated PROM of BID. As such, this study represents a methodological improvement over prior research that was cross-sectional in nature,11,13–17 included only short-term follow-up,3,18 or used nonvalidated measures of BID.19 Herein, we (1) demonstrate that the severity of BID worsens posttreatment relative to pretreatment (baseline) levels until 9 months posttreatment; (2) describe that >40% of patients fail to return to their pretreatment level at 9 months posttreatment; (3) highlight a large subset of HNC survivors who fail to recover to pretreatment body image levels and experience a more protracted course of posttreatment BID; and (4) show that >50% of HNC survivors experience clinically significant posttreatment worsening in body image concerns. By providing novel information about the temporal trajectory of BID following surgical treatment of HNC, these data advance our knowledge of the disorder, can enhance preoperative counseling, and may be used to guide the delivery of optimally timed preventative and therapeutic interventions targeted to high-risk patients.

One of the major findings of this study is that, on average, patients surgically treated for HNC recover to pretreatment levels of body image dissatisfaction by 9 months posttreatment. Fingeret et al, in their cross-sectional analysis of 280 patients with HNC, demonstrated that survivors within the first year posttreatment experienced higher levels of body image dissatisfaction relative to pretreatment patients.11 Our prospective data provide more granular estimates about the expected course of body image recovery.

A second critical result of our analysis is the identification of 2 distinct subgroups of HNC survivors with regard to the temporality of their adaptation to posttreatment BID—a finding that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously reported. Although the mean change in BIS scores relative to baseline returns to zero at 9 months posttreatment for the cohort overall, we demonstrated that 43% of HNC survivors fail to return to baseline at 9 months posttreatment. This subgroup of HNC survivors has a significant increase in the severity of their body image dissatisfaction immediately after treatment relative to pretreatment levels and maintain this new level throughout the first year posttreatment without amelioration. Although our data do not allow us to discern the underlying mechanism why patients with similar defects and reconstructions experience such divergence in their recovery, we hypothesize that unmeasured intrinsic characteristics related to image investment or coping strategies may be responsible for the differences between the subpopulations. Future studies should aim to understand the underlying biological mechanism responsible for the observed differences. In addition, our finding highlights that future preventative and therapeutic interventions may specifically target this subpopulation of HNC survivors.

The development of biomarkers, the identification of pretreatment characteristics, or the creation of screening tools would help identify those patients with HNC who are at highest risk for posttreatment body image concerns and facilitate the delivery of targeted interventions. Unfortunately, our data evaluating the association between clinical, oncologic, and psychosocial characteristics and persistent BID and large increases in BID following treatment did not help identify a high-risk subgroup. It is well documented that measures of objective disfigurement correlate poorly with BID in patients with HNC.11 As such, prior studies have focused on predisposing psychosocial factors, such as depression and anxiety,1,3,8,22,27 and conceptual models highlight the potential moderating roles of image investment, preoperative expectations, and image coping strategies on the development of BID following treatment of HNC.28 However, the relationship of certain psychosocial variables and BID has been variable and conflicting across studies, likely reflecting limitations of the cross-sectional design, differences in study populations, inconsistent covariate adjustment, and heterogeneous psychosocial and body image assessment tools.22 The current study was powered to detect prespecified changes in the primary endpoint (BIS scores over time) and thus was underpowered for analysis of secondary endpoints (factors associated with persistent BID and increases in BID severity). As such, additional prospective research that is powered to identify biomarkers and baseline pretreatment characteristics is necessary to characterize a precise high-risk subpopulation that is predisposed to a protracted and refractory course of BID following treatment of HNC.

Although the data presented herein can help inform the timing of the delivery of preventative and therapeutic interventions for BID in patients undergoing surgery for HNC, no effective therapies for BID in HNC survivors have been described.1,11 Researchers have evaluated the effect of cosmetic rehabilitation29 and skin camouflaging30 on BID in HNC survivors. Unfortunately, neither intervention was effective at treating BID. As a result, treatment of BID in HNC survivors represents a significant unmet survivorship need.31 Prior work in patients with breast cancer who have with body image dissatisfaction suggests that cognitive behavioral, mindfulness, and compassion-based interventions have significant potential and merit further exploration and rigorous testing in HNC survivors.32–34 Such interventions would need to be tailored to the specific body image concerns relevant to HNC survivors and reflect key HNC BID-related conceptual domains, such as personal dissatisfaction with appearance, other-oriented appearance concerns, appearance concealment, distress with functional impairments, and social avoidance and isolation.28

This prospective cohort study with a validated PROM was methodologically sound and conducted with low levels of missing data. Although the study was appropriately powered on the basis of our preliminary data, missing data from those who died or were lost to follow-up may bias study findings if these patients were systematically different than those who remained alive and continued to follow up. Although the BIS is the most widely used PROM of BID for patients with HNC,22 limited psychometric data prevent us from making more definitive claims about the clinical significance of changes in BIS scores over time. The study is also limited by its single-institution design, which may preclude the generalizability of these data to other practice settings or patient populations. We attempted to maintain high external validity by employing a purposive enrollment strategy and creating a cohort representative of a standard academic HNC practice. However, the heterogeneous inclusion criteria limit internal validity relative to a study with narrowly defined inclusion criteria.

In this prospective cohort pilot study, we provide novel and clinically impactful data regarding the epidemiology of BID in surgically treated HNC survivors. We (1) demonstrate that the severity of BID worsens posttreatment relative to pretreatment (baseline) levels until 9 months posttreatment, (2) identify a large subset of HNC survivors who fail to recover to pretreatment body image levels and experience a protracted trajectory of body image recovery, and (3) show that >50% of HNC survivors experience clinically significant posttreatment worsening in body image concerns. Although these data can enhance preoperative counseling and guide the delivery of optimally timed preventative and therapeutic interventions targeted to high-risk patients, significant further research is required to identify better pretreatment markers of posttreatment BID. Novel, effective strategies to prevent and treat BID in HNC survivors are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: ACS IRG-16-185-17 from the American Cancer Society to Evan M. Graboyes, P30 CA138313 from the National Cancer Institute to the Biostatistics Shared Resource of the Hollings Cancer Center, database support from the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute (UL1TR000062). No role in the design and conduct; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or writing or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental Material

Additional supporting information is available in the online version of the article.

Disclosures

Competing interests: Eric J. Lentsch—director of content for DosedDaily.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- 1.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Goettsch K. Body image: a critical psychosocial issue for patients with head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2015;17:422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhoten BA, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhoten BA, Deng J, Dietrich MS, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image and depressive symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer: an important relationship. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:3053–3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu YS, Lin PY, Chien CY, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with head and neck cancer: 6-month follow-up study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osazuwa-Peters N, Simpson MC, Zhao L, et al. Suicide risk among cancer survivors: head and neck versus other cancers. Cancer. 2018;124:4072–4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhoten BA. Body image disturbance in adults treated for cancer—a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teo I, Fronczyk KM, Guindani M, et al. Salient body image concerns of patients with cancer undergoing head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck. 2016;38:1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Reece GP, Gillenwater AM, Gritz ER. Multidimensional analysis of body image concerns among newly diagnosed patients with oral cavity cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32:301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen F, Snyder CF, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Identifying cutoff scores for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the head and neck cancer-specific module EORTC QLQ-H&N35 representing unmet supportive care needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38(suppl 1):E1493–E1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy BA, Ridner S, Wells N, Dietrich M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: a review of the current state of the science. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:251–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fingeret MC, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Weston J, Nipomnick S, Weber R. The nature and extent of body image concerns among surgically treated patients with head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21:836–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:203–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Branch L, Feuz C, McQuestion M. An investigation into body image concerns in the head and neck cancer population receiving radiation or chemoradiation using the body image scale: a pilot study. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2017;48:169–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke SA, Newell R, Thompson A, Harcourt D, Lindenmeyer A. Appearance concerns and psychosocial adjustment following head and neck cancer: a cross-sectional study and nine month follow-up. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19:505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen SC, Yu PJ, Hong MY, et al. Communication dysfunction, body image, and symptom severity in postoperative head and neck cancer patients: factors associated with the amount of speaking after treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23: 2375–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung TM, Lin CR, Chi YC, et al. Body image in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy: the impact of surgical procedures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C, Cao J, Wang L, Zhang R, Li H, Peng J. Body image and its associated factors among Chinese head and neck cancer patients undergoing surgical treatment: a cross-sectional survey [published online June 21, 2019]. Support Care Cancer. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04940-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graboyes EM, Hill EG, Marsh CH, Maurer S, Day TA, Sterba KR. Body image disturbance in surgically treated head and neck cancer patients: a prospective cohort pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krouse JH, Krouse HJ, Fabian RL. Adaptation to surgery for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis MA, Sterba KR, Brennan EA, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing body image disturbance in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160:941–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopwood P, Lee A, Shenton A, et al. Clinical follow-up after bilateral risk reducing (“prophylactic”) mastectomy: mental health and body image outcomes. Psychooncology. 2000;9:462–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kissane DW, Patel SG, Baser RE, et al. Preliminary evaluation of the reliability and validity of the Shame and Stigma Scale in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2013;35:172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahn EA, DeWalt DA, Bode RK, et al. New English and Spanish social health measures will facilitate evaluating health determinants. Health Psychol. 2014;33:490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fingeret MC, Hutcheson KA, Jensen K, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Lewin JS. Associations among speech, eating, and body image concerns for surgical patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2013;35:354–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis MA, Sterba KR, Day TA, et al. Body image disturbance in surgically treated head and neck cancer patients: a patient centered approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161: 278–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang S, Liu HE. Effectiveness of cosmetic rehabilitation on the body image of oral cancer patients in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:981–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen SC, Huang BS, Lin CY, et al. Psychosocial effects of a skin camouflage program in female survivors with head and neck cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1376–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giuliani M, McQuestion M, Jones J, et al. Prevalence and nature of survivorship needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38:1097–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Epner DE. Managing body image difficulties of adult cancer patients: lessons from available research. Cancer. 2014;120:633–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esplen MJ, Wong J, Warner E, Toner B. Restoring Body Image After Cancer (ReBIC): results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherman KA, Przezdziecki A, Alcorso J, et al. Reducing body image-related distress in women with breast cancer using a structured online writing exercise: results from the my changed body randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1930–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.