The novel coronavirus, 2019-nCov (named as SARS-CoV-2 by ICTV Coronaviridae Study Group on February 12, 2020), causes severe respiratory illness1 and has been spreading around the world rapidly.2 As of February 14, 2020, there are over 64,000 confirmed cases with 1,384 deaths. This raises an urgent need for an effective treatment of the deadly disease. However, current antiviral drugs have limited effects on 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2). Although Gilead’s NUC (nucleoside) inhibitor, which previously failed to treat Ebola, seemed to benefit a 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) patient in Washington, USA, it remains unknown whether the drug will be effective against the virus in other patients, who may have been infected by different variants of the virus. Our analysis of 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome from 19 patients in China, USA and Australia reveals that these viruses have differences in sequence (Fig. 1a). These differences are mostly single nucleotide variations. Fig. 1b shows an example of single nucleotide variations that result in changes in amino acids 62 and 84 of ORF8 of 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2), a polypeptide implicated in driving coronavirus transition from bat to human.3 The evidence from patient samples suggests that 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) is actively acquiring new mutations that may enable it to escape antiviral drugs. This raises a serious challenge to the development of conventional drugs and of vaccines. The same limitations apply to other deadly RNA viruses such as SARS or MERS.

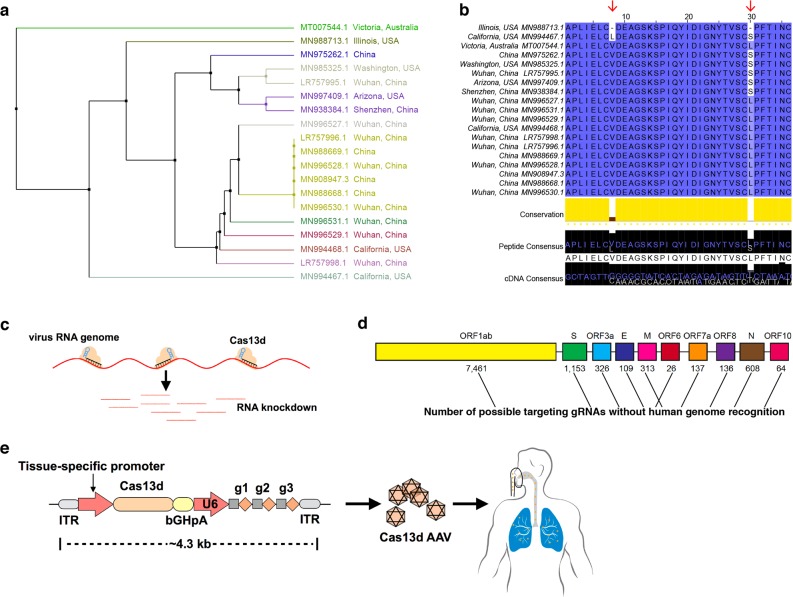

Fig. 1. Analysis of genomic variations between 2019-nCov(SARS-CoV-2) viruses from infected patients in different countries and a flexible CRISPR/Cas13d strategy for treating 2019-nCov(SARS-CoV-2) virus infection and countering its evolution.

a, b Sequence analysis of 2019-nCov(SARS-CoV-2) virus RNA genome with available complete sequences from 19 infected patients in China, USA and Australia. Lineage tree (a) and peptide sequence alignment (b) for a portion of the polypeptide ORF8 of 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2), showing sequence variation between the 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) viruses from different patients. The sequences were extracted from GenBank then aligned with MUSCLE algorithm and visualized with Jalview. Red arrows in (b) indicate regions with variants. Geographical locations and GenBank IDs of the 19 patients are shown. c A model for Cas13d cleavage of 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome. d Number of guide RNAs that can be designed to cleave each peptide-encoding region of 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome without affecting the human genome. All possbile guide RNAs (gRNAs) containing 22 nt spacer sequences were generated for peptide-encoding regions of 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome then mapped to human genome with Bowtie. Guide RNAs with no alignment to human genome allowing up to 2 mismatches were considered to be specific to the 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome without human genome recognition. e Schematic for AAV design carrying Cas13d effector and a three-gRNA array for treatment of patients with 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) infection. ITR inverted terminal repeats.

Our group has implemented a flexible and efficient approach for targeting RNA in the laboratory using CRISPR/Cas13d technology (under review), and here we propose that this system can be used to specifically chew up 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome, hence limiting its ability to reproduce. To functionally disrupt the virus, we will specifically use guide RNAs (gRNAs) that concomitantly target ORF1ab and S, which represent the replicase-transcriptase (ORF1ab) and the spike (S) of the virus. The Gilead’s NUC inhibitor, remdesivir, having a similar chemical structure to HIV reverse-transcriptase inhibitors, is currently being tested in clinical trials for 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2), while a drug targeting the spike glycoprotein has also been tested in phase I trials for the treatment of HIV and SARS-CoV.4

CRISPR/Cas13d is an RNA-guided, RNA-targeting CRISPR system.5 To cleave the 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome, a Cas13d protein and guide RNAs-containing spacer sequences specifically complementary to the virus RNA genome are used (Fig. 1c). One advantage of the CRISPR/Cas13d system is its flexibility with respect to designing guide RNAs, because the RNA-targeting cleavage activity of Cas13d does not depend on the presence of specific adjacent sequences such as the NGG motif for the DNA-editing effector, Cas9.5 This unique feature of the system meets the requirement for rapid development of guide RNAs to target different virus variants that evolve and may escape traditional drugs. In total, we have designed 10,333 guide RNAs to specifically target 10 peptide-coding regions of the 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) virus RNA genome, without affecting the human transcriptome (Fig. 1d). Due to its desirable safety profile, adeno-associated virus (AAV) can serve as a vehicle to deliver the Cas13d effector to patients infected with 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2). The small size of the Cas13d effector makes it suitable for an ‘all-in-one’ AAV delivery with a guide-RNA array (Fig. 1e). Up to three guide RNAs targeting different peptide-encoding regions of 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) RNA genome can be packaged into one AAV vector (Fig. 1e), making the system more efficient for virus clearance and resistance prevention. The expression of Cas13d can be driven by tissue-specific promoters to achieve precise treatment of infected organs. Additionally, AAV has serotypes highly specific to the lung, the main organ infected by 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2), and thus can be exploited for targeted delivery of the CRISPR system. A similar strategy is applicable to other types of RNA viruses.

Taken together, we propose that CRISPR/Cas13d system is potentially a straightforward, flexible, and rapid novel approach for the treatment and prevention of RNA virus infection. Future studies determining the safety and efficacy of this system in eliminating 2019-nCov (SARS-CoV-2) and other viruses in animal models are needed before its therapeutic application to patients. If proven to be effective, this therapeutic approach will provide patients worldwide with more options to fight against life-threatening viruses that have the potential to evolve and develop resistance rapidly.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Tuan M. Nguyen, Yang Zhang

References

- 1.Huang Chaolin, Wang Yeming, Li Xingwang, Ren Lili, Zhao Jianping, Hu Yi, Zhang Li, Fan Guohui, Xu Jiuyang, Gu Xiaoying, Cheng Zhenshun, Yu Ting, Xia Jiaan, Wei Yuan, Wu Wenjuan, Xie Xuelei, Yin Wen, Li Hui, Liu Min, Xiao Yan, Gao Hong, Guo Li, Xie Jungang, Wang Guangfa, Jiang Rongmeng, Gao Zhancheng, Jin Qi, Wang Jianwei, Cao Bin. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perlman Stanley. Another Decade, Another Coronavirus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(8):760–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau SKP, et al. J. Virol. 2015;89:10532–10547. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01048-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, G. & De Clercq, E. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0 (2020).

- 5.Konermann S, et al. Cell. 2018;173:665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]