Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is an immune-mediated, chronic relapsing disorder characterised by severe gastrointestinal symptoms that dramatically impair patients’ quality of life, affecting psychological, physical, sexual, and social functions. As a consequence, patients suffering from this condition may perceive social stigmatisation, which is the identification of negative attributes that distinguish a person as different and worthy of separation from the group. Stigmatisation has been widely studied in different chronic conditions, especially in mental illnesses and HIV-infected patients. There is a growing interest also for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, in which the possibility of disease flare and surgery-related issues seem to be the most important factors determining stigmatisation. Conversely, resilience represents the quality that allows one to adopt a positive attitude and good adjustments despite adverse life events. Likewise, resilience has been studied in different populations, age groups, and chronic conditions, especially mental illnesses and cancer, but little is known about this issue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, even if this could be an interesting area of research. Resilience can be strengthened through dedicated interventions that could potentially improve the ability to cope with the disease. In this paper, we focus on the current knowledge of stigmatisation and resilience in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Quality of life, Ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and IBD unclassified for patients where the diagnostic distinction between CD and UC remains uncertain [1, 2]. IBD is an immune-mediated chronic condition for which currently no definitive cure is available. The natural history of IBD is characterised by periods of remission and relapse [3, 4]. While some patients may experience long periods of remission, others may experience a rather aggressive course with rapid disease progression [5]. In UC, mucosal inflammation is limited to the colon, typically extending proximally from the rectum [1]. In contrast, CD may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the anus, and is characterised by skip lesions, and carries the risk of developing fistulas, strictures, and abscesses [2]. Our understanding of the pathophysiology leading to the development of IBD remains incomplete [6]. Most likely, there is a complex interplay of reduced intestinal barrier function, an overshooting intestinal immune response to pathogen presentation, genetic predisposition, and environmental triggers [7].

IBD is a relatively common disease with an estimated incidence of UC at 24.3 per 100,000 and CD at 12.7 per 100,000 person years in Europe [8]. Similar incidence rates are seen in other developed nations, but there has been a recent rise in its incidence in developing nations [8]. IBD can develop at any age, but peak incidence is in early adulthood, with a second peak in patients over 65 years of age. As mortality from IBD is relatively low, the prevalence of IBD is rising [9]. Medical treatment for IBD includes mesalazine therapy—for UC only—with immunosuppressive treatment for CD and UC cases not controlled by mesalazine. Advanced medical therapy of IBD includes biological treatments with anti-tumour necrosis factor α agents, anti-integrin agents, and agents against interleukin-12/23. Recently the small molecule tofacitinib has been approved for UC and many other molecules are currently in development. While the above agents are effective in inducing response and remission in IBD, at least a third of patients do not respond to medical therapy [1, 2]. There remains a high need for surgical intervention in IBD.

The symptoms of IBD can vary depending on diagnosis and phenotype, but very often include diarrhoea, bleeding per rectum, anaemia, abdominal pain and weight loss [1, 2]. In addition, patients with CD may experience fistula discharge, abscesses or bowel obstruction due to the development of strictures [2, 10], whereas severe colonic inflammation in UC may lead to toxic megacolon [11]. All the aforementioned factors largely justify the high psychological burden for patients with IBD. Anxiety and depression affect many patients with IBD [12, 13] and this is often associated with poor disease outcomes. Anxiety may be driven by physical symptoms and the fear associated with experiencing those. For example, worry about incontinence in patients with diarrhoea may lead to anxiety and social isolation. Importantly, medications such as corticosteroids, which are widely prescribed for the management of flares, may in themselves precipitate anxiety and depression [14]. The patients may also become fearful of potential disease complications leading to hospital admission, need for resection surgery or the development of IBD-related colorectal cancer [3]. These fears may often be in excess of the actual risk of such a complication. The patients may fear surgical treatment for the risk of needing a stoma and medical treatments over concerns of potentially severe complications from immunosuppressive therapy. In addition, misinformation or unchecked information sources can be associated with a higher risk of anxiety [15].

In summary, patients with IBD experience disabling physical symptoms might need life-changing surgery and a have higher level of psychological distress and illnesses. These challenges will undoubtedly also affect their social and work life. This article provides the most recent insights regarding stigmatisation that IBD patients may experience and the resilience and coping skills involved in dealing with their disease.

Literature search strategy

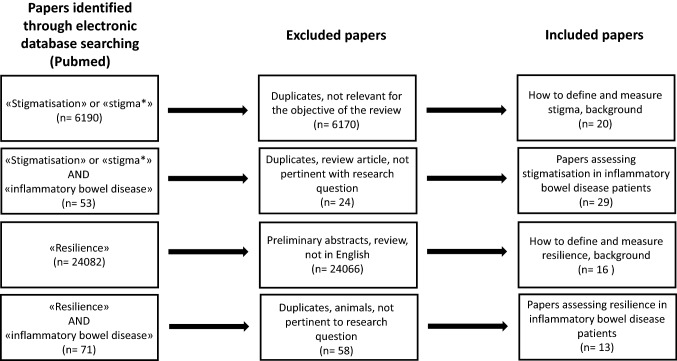

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of paper selection. During the first week of September 2019, we searched Medline (PubMed) using the medical subject heading terms “stigmatisation”, “stigma*”, and “resilience” alone or matched with “inflammatory bowel disease”, “Crohn’s disease”, and “ulcerative colitis” for all articles published in English since inception, focusing on the research question of this review, i.e., the evaluation of stigmatisation and resilience in patients with IBD, with any of the available scales. Two authors independently searched the electronic database for papers dealing with stigmatisation (MVL, SC) and resilience (JG, MVL) in IBD patients. More than 1000 papers were found with this search strategy, the majority of which were unrelated to the subject of this review and were not considered (see Fig. 1). We, therefore, selected only landmark studies and relevant review articles for the general description of stigmatisation and resilience, focusing instead on original papers dealing with this issue in adult IBD patients. Finally, we also searched the reference lists of pivotal review articles for additional papers we judged to be relevant to this review.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of paper selection that was performed through Pubmed for articles written in English. The main research question regarded the evaluation of stigmatisation and resilience in patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease. The medical subject heading terms “Crohn’s disease” and “ulcerative colitis” were also used. More general articles dealing with how to define and how to measure stigmatisation and resilience were used to provide background for the purpose of the review

Stigmatisation: definition and how to measure it

Stigmatisation can be defined as the identification of negative attributes that distinguish a person as different and worthy of separation from the group, often leading the person losing social status and facing discrimination [16]. Social stigma is a complex and continually evolving phenomenon. It includes one’s own perception, the internalisation of negative behaviours held by other subjects, and the implementation of behaviours by other subjects [17]. Therefore, it is usually divided into three main domains. “Enacted stigma” is “stigma put into practice” and represents direct social discrimination and discriminatory experiences. “Perceived” or “felt stigma” relates to individuals feelings that other subjects have negative attitudes or negative beliefs about them and their condition. “Internalised stigma” or “self-stigmatisation” occurs when stigmatised individuals begin to conform to social mentality and to believe that stereotypes about their condition are actually true and apply to themselves [18]. A fourth recognised domain called “resistance to stigma” has been identified by some researchers using the stigma scale for mental illness (ISMI) and has been described as an adaptive response [19].

In each victim of stigmatisation, we can recognise any of the four domains of stigma and the relationship between each of them and the impact on patients’ health and well-being is well documented in the literature [20–22]. Indeed, the entity of stigmatisation depends on many factors, involving the patient, the disease, and the social context.

The stigmatisation of subjects suffering from mental illnesses has a long historical tradition, as proven by the fact that the word “stigmatisation” derives from "stigma" which is the mark that in ancient Greece was applied to slaves and criminals [23]. In the following millennia, society did not treat people who suffered from depression, autism, schizophrenia, and any other mental illness much differently to slaves and criminals. Subjects suffering from psychiatric illnesses were imprisoned, tortured, and sometimes even murdered [23]. Stigmatisation of mental illness has been identified as a critical health problem. Individuals who suffer the effects of stigmatisation due to their mental illness have a reduced life expectancy, not only due to the increase in suicides or self-harm, but due to a reduction in their physical health [24]. Such reduction is not only the consequence of both the side effects of medicines and lifestyle, but also of limited accessibility to the health services and an impaired general quality of life [24].

Besides mental illnesses, social stigmatisation is also associated with other chronic conditions. The most emblematic example is represented by patients suffering from HIV infection, who are often stigmatised due to the association of this disease with behavioural factors, such as intravenous drug abuse, and sexual promiscuity [25]. A meta-analysis based on 64 studies showed that higher levels of depression, reduced levels of social support, reduced levels of adherence to anti-retroviral therapy, and reduced access to the social services were found in HIV-infected patients who perceived high stigma [26]. Similarly, patients with lung cancer can be stigmatised due to the strong connection of the disease with cigarette smoking [27]. In lung cancer patients, it was shown that the perception of stigma resulted in increased severity of depression, anxiety and overall severity of cancer-related symptoms [28]. Among others, patients with epilepsy may perceive the stigma due to the symptoms and the care burden they exert on their loved ones, such as the inability to drive [29]. Patients with a functional illness, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel disease (IBS), experience stigmatisation in relation to the fact that other people neither believe to the authenticity of their condition and, therefore, do not validate nor believe their experiences and symptoms exist [30].

Stigmatisation is assessed throughout the use of different scales, depending on the specific disorder. In patients with psychiatric diseases, the ISMI scale is most commonly used [19], while the HIV stigma scale [31] and the IBS perceived stigma scale (PSS) [32] are used for HIV and IBS patients, respectively. The same PSS used for IBS patients was also applied to IBD patients [17]. The PSS–IBD is a self-administered scale consisting of 20 statements, equally divided between significant others (friends, family members, spouse or partner) and health care providers (doctors, nurses, therapists, or other people who provide medical care). Each score is obtained by dividing the sum of the single item scores by the total number of answered items. Higher scores denote greater perceived stigma, with a range of 0 (never) to 4 (always) per every single statement.

Stigmatisation in inflammatory bowel disease

IBD mainly affects young adults with symptoms ranging from abdominal pain and diarrhoea, to fever, weight loss, malnutrition, and intestinal obstruction requiring hospitalisation [33]. These conditions are clearly susceptible to stigmatisation, mainly because of their symptoms, the incorrect historical assumption of being psychosomatic conditions, and given that they may deeply affect sexual life and body image [34]. Intestinal symptoms can be detrimental to the patient, in particular in a social setting, as the taboo around such symptoms is still widespread in many cultures [17]. Furthermore, while today IBD aetiology places it in the field of immune-mediated diseases, in the past they were seen as psychosomatic illnesses in which one’s personality traits made him/her susceptible to its manifestations. The notion that a person could develop CD because of his/her "obsessive behaviour" could explain stigmatisation [35].

The patients with IBD frequently report problems related to stigmatisation, including being treated differently, having a stoma bag, and being a burden to others [36–38]. An American study recruiting patients online and through the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation showed that perceived stigma is a significant predictor of poor outcomes in IBD patients, playing a role in the quality of life of patients with detrimental effects similar to those seen in other chronic diseases [39]. The activity of the disease did not correlate with stigma perception. This may be due to the constant worry over potential flares rather than just over current symptoms [39].

Data regarding perceived stigma in IBD and IBS are controversial. Looper et al. did not find any significant difference in a study from 2004 [40], while a later study on a much larger cohort showed that IBS patients perceiving moderate-to-high stigma were three times more common than those with IBD [17].

There is now a substantial body of evidence regarding the importance of stigmatisation in IBD. These studies have focused on the various domains of stigmatisation, including perceived, internalised, and enacted stigma (Table 1) [17, 36, 38–64].

Table 1.

Relevant studies exploring stigmatisation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

| Authors | Year | Country | Type of stigma | Sample size | Key points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wyke et al. | 1988 | UK | Perceived, enacted | 170 | Most individuals disclosed IBD, most co-workers/employers were understanding, IBD led to changes in work |

| Drossman et al. | 1989 | USA | Perceived | 150 | Most common concerns related to surgery, energy level and body image |

| Salter | 1990 | USA | Internalised | Not clear | Ostomy allows “to control” the disease, feeling clumsy during sexual intercourse |

| Mayberry et al. | 1992 | UK | Enacted | 58 (CD only) | Unemployment, CD patients more likely to conceal their disease to employers |

| Moody et al. | 1992 | UK | Enacted | 53 | Employers unwilling to employ an individual with IBD and to give time off to attend clinics |

| Mayberry | 1999 | UK | Enacted | 195 (personnel managers) | Unwillingness to provide time to see the physician, IBD jeopardises promotions |

| Moody et al. | 1999 | UK | Perceived | 64 | Many students complain of teachers not being sympathetic, underachievement due to ill health |

| Moskovitz et al. | 2000 | Canada | Perceived | 86 | Poor social support is related to worse surgical outcomes |

| de Rooy et al. | 2001 | Canada | Perceived | 241 | Greater stigma perceived by elderly, females, patients with UC, and with low level of education; |

| Levenstein et al. | 2001 | Cross-national | Perceived, internalised | 2002 | Complications and variable disease evolution elicit concern; specific issues vary among countries |

| Daniel | 2002 | USA | Perceived, enacted, internalised | 5 | Impaired body image, feeling different, ashamed and worried about others thinking IBD is used for secondary gain |

| Krause | 2003 | Chile | Internalised | 19 | IBD as illness that invades all dimensions of life |

| Looper and Kirmayer | 2004 | Canada | Perceived | 89 (51 IBD) | Higher level of perceived stigma in functional disorders vs other medical conditions (including IBD) |

| Finlay et al. | 2006 | USA | Perceived | 148 | Major differences across ethnic groups regarding knowledge of disease and social support |

| Smith et al. | 2007 | USA | Internalised | 195 (71 with IBD) | Disgust related to low colostomy adjustment, low life satisfaction, low quality of life and to stronger feelings of stigmatisation |

| Simmons et al. | 2007 | UK | Internalised | 51 | Stoma acceptance, interpersonal relationship and location of the stoma were associated with adjustment |

| Taft et al. | 2009 | USA | Perceived | 211 | Perceived stigma affects quality of life |

| Voth and Sirois | 2009 | UK | Internalised | 259 | IBD self-blame is related to poorer outcomes |

| Taft et al. | 2011 | USA | Perceived | 496 | Greater stigma in IBS than IBD, patient outcomes more affected in stigmatised IBD patients |

| Dibley and Norton | 2013 | UK | Perceived | 611 | Emotional and psychological impact, feelings of stigma, limited lives, practical coping mechanisms |

| Czuber-Dochan et al. | 2013 | UK | Perceived | 46 | IBD-related fatigue not addressed in medical consultations |

| Taft et al. | 2013 | USA | Internalised | 191 | Social isolation common due to stigma |

| Czuber-Dochan et al. | 2014 | UK | Enacted | 20 (healthcare professionals) | IBD-related fatigue poorly understood |

| Frohlich | 2014 | USA | Perceived | 14 | Feeling stigmatised by partner, healthcare professionals, and colleagues |

| Saunders | 2014 | UK | Perceived | 16 | Non-disclosure because of shame may lead to experiencing blame |

| Bernhofer et al. | 2017 | USA | Perceived | 16 | Feeling labelled as unable to tolerate pain |

| Rohde et al. | 2018 | USA | Enacted | 127 | Enacted stigma among college students decreases when IBD is disclosed |

| Gamwell et al. | 2018 | USA | Perceived | 80 | Indirect effect of perceived stigma on depressive symptoms as it impacts on social belongingness |

| Dibley et al. | 2019 | UK | Perceived, internalised | 18 | Kinship stigma is present in IBD patients |

CD Crohn’s disease, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, IBS irritable bowel syndrome

Perceived stigma in IBD was evaluated first in 1989, showing how the functional impairment experienced by patients was greater in their social and psychological rather than in their physical dimensions [36]. Moreover, CD patients were affected by a higher degree of perceived stigma compared to UC patients. A cross-sectional survey of 611 UK patients with IBD revealed that concerns about how other people perceived IBD led to social withdrawal and isolation, in an effort to protect themselves from potential shame [55]. These findings were confirmed by a subsequent study showing how perceived stigma indirectly worsened depression and favoured social isolation [63]. A cross-sectional survey involving 2002 IBD patients from 8 countries showed that disease-related concerns varied considerably, probably due to differences in social and economic background [48]. The study highlighted the relevance of surgery, the possibility of having an ostomy, uncertainties and unpredictability of disease course, and treatment side effects. Additionally, patients often reported concerns about being a burden to others, of feeling dirty, and of having sexual and intimacy difficulties due to their disease [48].

Studies evaluating the effect of internalised stigma in IBD patients have shown how one-third of patients reported internalised stigma in addition to alienation and social withdrawal and how most engaged in stigma resistance behaviours [57]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that self-blame correlates with poor outcomes and leads IBD patients to avoid coping strategies [54]. Ostomy was shown to be associated with self-stigma due to the feeling of shame related to it [52].

Finally, the enacted stigma was evaluated in several studies, generally showing how being affected by IBD has an impact on working life, as IBD patients are more likely to encounter difficulties in finding a job and getting a promotion [43–45]. Disappointingly, 30% of work managers would not provide time off to their employee to attend outpatient clinic appointments [44, 45]. More recently, the enacted stigma was evaluated in a cohort of college students showing that better awareness of the disease reduced stigma [62].

As most of these studies were conducted in the late 1990s and early 2000, and given that only a few more studies have been published since the last systematic review dealing with this issue [34], there is an urgent need to carry out further studies assessing stigmatisation related to IBD.

Resilience: definition and how to measure it

Studies on resilience vary in their methodology and samples [64–66]. Historically, most studies focused on difficult environmental circumstances and children's ability to thrive and withstand the risk factors in their surroundings [67, 68]

Resilience, from the Latin verb "resilire", means rebound or recoil [69]. The most commonly used description for medical purposes involves the ability to adapt well in the face of adversity [70]. Recently, Ungar recommended to standardisation of research on resilience by defining three distinct parts: (1) risk exposure, (2) desired outcome, and (3) protective factors [67]. However, resilience is a dynamic process that grows over time [65].

Resilience among patients with a chronic illness is often defined as an individual's ability to cope well in the face of disease [71]. Literature reviews on chronic illnesses and resilience revealed a paucity of articles including adults compared to children [72, 73]. However, resilience was either defined as a set of personal traits or as an outcome. In cancer patients undergoing treatment [74], higher levels of resilience were positively related to higher levels of activity and lower levels of psychological distress. In a study of the relation between self-silencing and resilience in women with HIV, higher rates of silencing were associated with lower levels of resilience [75]. Furthermore, higher levels of income, education, and employment were significantly associated with resilience. A review of 12 cross-sectional studies on resilience and chronic illness showed that resilience was both a significant predictor and outcome of recovery and quality of life in individuals living with a chronic condition [71]. Hence, resilience can be considered as a part of a patient’s clinical complexity [76].

There is a multitude of scales measuring resilience mostly unique to the sample or specific situation researched. A comprehensive review by Windle et al. concluded that of 15 original scales examined many lacked sufficient information regarding the psychometric ratings and theoretical underpinning of the scales [77]. Three scales were regarded as having more robust psychometric properties, Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) [78], resilience scale for adults (RSA), and the brief resilience scale (BRS) [79, 80].

The BRS contains six items of resilience with higher scores indicating higher levels of resilience [80]. The BRS assesses individuals' traits of resilience and their ability to cope with stress. It was initially tested on samples of cardiac rehabilitated and fibromyalgia patients. Similarly, the RSA measured 5 domains of resilience with 37 items, namely personal competence, personal structure, social competence, social support, and family coherence [79]. It was originally tested on a sample of psychiatric outpatients. The scale was later reduced to 33 items and used a semantic differential scale format for higher accuracy [81]. Lastly, the CD-RISC comprises 25 items, also measuring trait resilience on a five-point Likert scale [78]. Like the RSA, CD-RISC was first assessed among a sample of psychiatric patients. To this day, the CD-RISC has been translated into over 70 different languages and is by far the most widely used scale of resilience [82].

Resilience in inflammatory bowel disease

Although IBD imposes a mental and physical toll on individuals [83], some individuals do report feeling stronger due to having IBD [84].

Most studies included in this review (Table 2) investigated psychological resilience and trait resilience that promoted the ability to bounce back from IBD-related adversity [85–97]. Some demographic characteristics found to be relevant to individuals with IBD included being optimistic, older [85], male, employed, not religious, and nulliparous [86]. Women with IBD more commonly reported resilience to be an essential determinant of health and both genders mentioned self-efficacy, social support, occupational balance, and job satisfaction as the main determinants of health [87]. Women with IBD and high resilience showed changes in brain-behavioural patterns, whereas the results were not conclusive for male participants [88]. Individuals whose onset of CD occurred later in life (after 30 years of age) and who performed complimentary activities appeared to be more resilient [86]. These findings were corroborated by Taylor et al.'s study, which compared level of physical activity, resilience, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among IBD participants [89]. A higher intensity of physical activity independently and significantly predicted a higher level of physical HRQOL, but not mental HRQOL. Resilience, on the other hand, was a significant and positive impact on mental HRQOL.

Table 2.

Relevant studies exploring resilience in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

| Authors | Year | Country | Measured resilience | Sample size | Key points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sirois | 2014 | Canada | Trait resilience | 155 (IBD) | High perception of health and high levels of resilience had greater odds of using CAM |

| Dur et al. | 2014 | Austria | Psychological resilience | 15 adults (CD) | Resilience appeared to be more salient and relevant to women vs men |

| Kilpatrick et al.a | 2015 | USA | Psychological resilience | 27 (IBD) | Female IBD with high resilience showed changes in brain-behavioural pattern |

| Scardillo et al. | 2016 | USA | Resilience as traits | 45 adults (30 IBD) | Resilience was significantly higher amongst individuals who adapted well to their ostomy |

| Sehgal et al.a | 2017 | USA | Psychological resilience | 113 | Lower level of resilience was associated with anxiety and depression; higher resilience predicted higher QOL |

| Carlsen et al. | 2017 | USA | Trait resilience—predictor of adjustment | 87 (30% adolescents, 62 CD) | Self-efficacy and resilience were significant predictors of transition readiness among adolescent and young adults with IBD |

| Melinder et al. | 2017 | Sweden | Psychosocial stress resilience | 1799 (UC) | Low-to-moderate stress resilience in adolescence correlated with increased risk of CD and UC |

| Sirois and Hirsch | 2017 | Canada | Trait resilience | 152 adults (51.7% CD) | No significant difference between resilient and thriving IBD patients on perceived social support, depressive symptoms, coping efficacy, and illness acceptance |

| Skrautvol and Naden | 2017 | Norway | Stress resilience | 13 adults (7 CD) | Several themes were delineated, notably “creating resilience through integrative care” |

| Taylor et al. | 2018 | USA | Trait resilience | 328 adults (145 UC) | Resilience positively and significantly associated with HRQOL |

| Acciari et al. | 2019 | Brazil | 11 personal traits | 104 adults (CD) | Individuals who were employed without children and males were more resilient than their counterparts; CD onset > 30 years old and individuals who had complimentary activities were more resilient |

| Hwang and Yu | 2019 | Korea | A set of quality influenced by society, relationships and psychology | 90 adults (76 CD) | Negative relation between resilience and depression; resilience was not affected by clinical characteristics in UC patients; lower income, sleep disturbances, being unmarried negatively impacted resilience in CD patients |

| Luo et al. | 2019 | China | Dynamic process of resilience | 15 adults (10 CD) | Necessary cognitive traits and resilience-specific coping mechanisms to deal constructively with IBD |

CAM complementary and alternative medicine, CD Crohn’s disease, IBS irritable bowel disease, HCs healthy controls, HRQOL health-related quality of life, UC ulcerative colitis, IBD inflammatory bowel disease

aAbstracts/conference proceedings

Sehgal et al. found that lower levels of resilience were associated with significantly higher levels of anxiety and clinical depression [90]. Conversely, higher levels of resilience were found to predict better quality of life among IBD patients.

Higher levels of resilience predicted higher levels of adaptation to the ostomy; notably, perseverance—defined as a trait of resilience was the most reliable predictor [91]. Moreover, lower income, sleep disturbances and being unmarried negatively impacted the level of resilience and depression among CD patients with an ostomy. Resilience was not significantly affected by clinical characteristics in UC patients. Overall, there was a slightly higher resilience level among UC patients compared to CD patients [92].

Contrarily to the previous studies, Sirois and Hirsch drew a distinction and defined resilience as a set of traits that only promote the ability to recover from an illness [93]. The authors contrasted the concept of resilience with one's ability to thrive, the latter entailed growth above and beyond the recovery. The study examined illness acceptance, coping efficacy, depressive symptoms, and perceived social support differences among IBD patients who experienced loss, resilience, and thriving. At baseline, results indicated that across the four outcomes coping efficacy significantly distinguished those who thrived versus those who were resilient. 6 months later, this difference was no longer statistically significant. However, both resilient and thriving IBD groups were consistently reporting better psychological outcomes compared to the individuals experiencing loss from their illness.

Stress resilience was investigated in two studies [94, 95]. Melinder et al. examined prospectively a large cohort of young men from the general Swedish population speculating that low-stress resilience would predict the onset of IBD. Three quarters of subsequently diagnosed individuals had low to moderate levels of stress resilience. Skrautvol and Naden examined qualitatively stress resilience through integrative care [95]. The highly select interviewees dealt with IBD using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and dietary supplements stressing the perceived importance of individualising treatment plans and making changes in their lifestyle. These findings go in line with Sirois' findings that 46% of individuals with IBD used CAM as a complementary treatment to conventional medicine [96]. Although the magnitude of the relation was small, individuals with IBD who reported high perception of health and high levels of resilience had greater odds of using CAM.

During transition from juvenile to adult-centred care, both self-efficacy (SE) and resiliency were found to independently and significantly predict better transition [97]. In response, Carlsen et al. developed an e-health transfer concept to assess patient-reported outcomes, including self-efficacy, resilience, stress response among adolescents with IBD transitioning to healthcare [98].

Resiliency and IBD only began to be investigated during the last 5 years. In most studies, resiliency was perceived as a series of traits or psychological resilience, only one study defined resiliency as a dynamic process [85], and two others looked at stress resilience [94, 95]. There also seemed to be some disagreement on whether the definition entails to thrive or restore former health [93]. Moreover, the dominance of cross-sectional data, small size, and purposive samples, as well as the near absence of longitudinal studies, are some of the shared limitations across the reviewed articles [99].

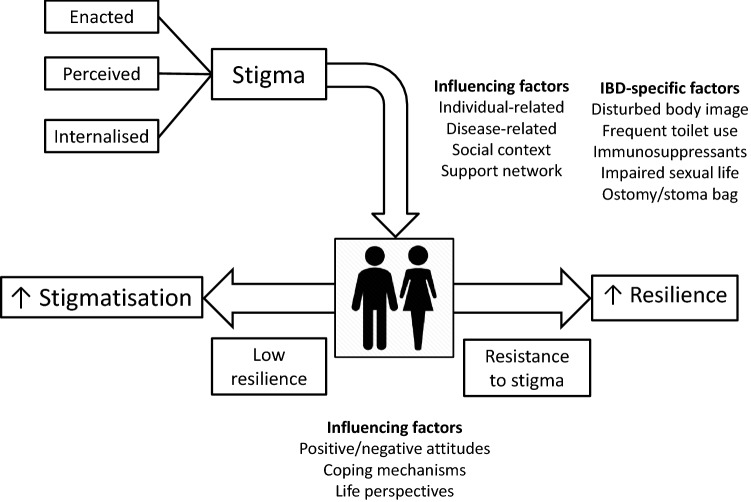

Stigmatisation and resilience share many common features (Fig. 2), some of which are IBD specific, and it is reasonable to assume that they mutually influence each other, as shown for psychiatric illnesses [100] and patients living with HIV [101]. Disappointingly, only one study involving 40 community-based adult patients with self-reported IBD has investigated this issue in the IBD population so far. In that study, the authors showed that individuals who seemed more resilient were also more positive, used humour as a coping mechanism, and placed their IBD in a wider life perspective [102]. Also, stigma was more evident in patients with weak resilience, especially in those suffering from mental health disorders and in those lacking support networks.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the most relevant features of stigmatisation and resilience and their influencing factors. Low resilience may favour stigmatisation, whilst resistance to stigma may strengthen resilience. Inflammatory bowel disease is burdened by a number of disease-specific issues that favour social stigmatisation and may affect resilience

Future directions

Many unmet needs still exist in the IBD research agenda, including a better understanding of its physiopathology, reduction of diagnostic delays, discovery of more effective and safer drugs, optimisation of existing therapies, improving patients’ adherence to the treatment plan, improving patient’s quality of life, management of extraintestinal manifestations, and prevention of complications [103–110]. A multidimensional approach is necessary for delivering high-quality healthcare for IBD patients, but we are still far from optimal management in real life [111]. Psychosocial aspects of IBD still receive less attention than the more physical aspects of the illness. According to current evidence, stigmatisation and resilience in IBD patients are not adequately addressed in day-by-day clinical practice, even if they have a great impact in terms of quality of life and coping with the stress of a chronic illness. More holistic approaches to IBD care are required that incorporate physical, psychological, and social aspects of living with IBD.

Further research is required to better understand how stigma and resilience influence patient engagement with medical services, adherence to treatment, attitude towards healthy living, and longer-term disease outcomes. Future work to establish if and how stigmatisation can be reduced and resilience improved is urgently needed. In the authors’ opinion, the combination of better medical treatments and comprehensive approaches addressing psychosocial aspects, including stigma and resilience, will lead to a better quality of life for patients with IBD.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Jennifer Tarabay for helping with the literature review and for drafting Table 2.

Abbreviations

- BRS

Brief resilience scale

- CAM

Complementary and alternative medicine

- CD-RISC

Connor–Davidson resilience scale

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IBS

Irritable bowel disease

- HRQOL

Health-related quality of life

- ISMI

Stigma scale for mental illness

- PSS

Perceived stigma scale

- RSA

Resilience scale for adults

- SE

Self-efficacy

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

Author contributions

All authors participated in the drafting of the manuscript or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and provided approval of the final submitted version. Individual contributions are as follows: all authors contributed to designing the review, collecting data, writing the manuscript, and reviewing the paper; CPS and MVL made the final critical revision for important intellectual content.

Funding

None.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

This article does not contain any study with human and animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Burisch J, Gecse KB, Hart AL, Hindryckx P, Langner C, Limdi JK, Pellino G, Zagórowicz E, Raine T, Harbord M, Rieder F, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] Third European Evidence-Based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–670. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomollon F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cullen GJ, Daperno M, Kucharzik T, Rieder F, Almer S, Armuzzi A, Harbord M, Langhorst J, Sans M, Chowers Y, Fiorino G, Juillerat P, Mantzaris GJ, Rizzello F, Vavricka S, Gionchetti P, ECCO 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Sabatino A, Rovedatti L, Vidali F, Macdonald TT, Corazza GR. Recent advances in understanding Crohn's disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:101–113. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Sabatino A, Biancheri P, Rovedatti L, Macdonald TT, Corazza GR. Recent advances in understanding ulcerative colitis. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0719-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selinger CP, Andrews JM, Titman A, Norton I, Jones DB, McDonald C, Barr G, Selby W, Leong RW, Sydney IBD Cohort Study Group Collaborators Long-term follow up reveals low incidence of colorectal cancer, but frequent need for resection, among Australian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;12:644–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Sabatino A, Lenti MV, Giuffrida P, Vanoli A, Corazza GR. New insights into immune mechanisms underlying autoimmune diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DH, Cheon JH. Pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and recent advances in biologic therapies. Immune Netw. 2017;17:25–40. doi: 10.4110/in.2017.17.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chermoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selinger CP, Leong RW. Mortality from inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1566–1572. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenti MV, Di Sabatino A. Intestinal fibrosis. Mol Aspects Med. 2019;65:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doshi R, Desai J, Shah Y, Decter D, Doshi S. Incidence, features, in-hospital outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality associated with toxic megacolon hospitalizations in the United States. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13:881–887. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1889-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Häuser W, Janke KH, Klump B, Hinz A. Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparisons with chronic liver disease patients and the general population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:621–632. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gracie DJ, Guthrie EA, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Bi-directionality of brain–gut interactions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1635–1646. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selinger CP, Parkes GC, Bassi A, Fogden E, Hayee B, Limdi JK, Ludlow H, McLaughlin S, Patel P, Smith M, Raine TC. A multi-centre audit of excess steroid use in 1176 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:964 –973. doi: 10.1111/apt.14334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selinger CP, Carbery I, Warren V, Rehman AF, Williams CJ, Mumtaz S, Bholah H, Sood R, Gracie DJ, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. The relationship between different information sources and disease-related patient knowledge and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:63–74. doi: 10.1111/apt.13831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taft TH, Keefer L, Artz C, Bratten J, Jones MP. Perceptions of illness stigma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1391–1399. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2002;1:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd JE, Adler EP, Otilingam PG, Peters T. Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) Scale: a multinational review. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2011;17:157–168. doi: 10.1177/1359105311414952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Beek KM, Bos I, Middel B, Wynia K. Experienced stigmatization reduced quality of life of patients with a neuromuscular disease: a cross-sectional study. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:1029–1038. doi: 10.1177/0269215513487234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scambler G, Heijnders M, van Brakel WH. Understanding and tackling health-related stigma. Psychol Health. 2006;11:269–270. doi: 10.1177/1359105306061186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rössler W. The stigma of mental disorders. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1250–1253. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henderson C, Noblett J, Parke H, et al. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:467–482. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millen N, Walker C. Overcoming the stigma of chronic illness: strategies for normalisation of a ‘spoiled identity’. Health Sociol Rev. 2001;10:89–97. doi: 10.5172/hesr.2001.10.2.89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011453. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328:1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cataldo JK, Brodsky JL. Lung cancer stigma, anxiety, depression and symptom severity. Oncology. 2013;85:33–40. doi: 10.1159/000350834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behavior JA. Stigma, epilepsy, and quality of life. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3:10–20. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Åsbring P, Närvänen A-L. Women’s experiences of stigma in relation to chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:148–160. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinius M, Wettergren L, Wiklander M, Svedhem V, Ekstrom AM, Eriksson LE. Development of a 12-item short version of the HIV stigma scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:115. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0691-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones MP, Keefer L, Bratten J, Taft TH, Crowell MD, Levy RPO. Development and initial validation of a measure of perceived stigma in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14:367–374. doi: 10.1080/13548500902865956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:720–727. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taft TH, Keefer L. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s12328-016-0639-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheffield BF, Carney MW. Crohn’s disease: a psychosomatic illness? Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:446–450. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Appelbaum MI. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Functional status and patient worries and concerns. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1379–1386. doi: 10.1007/BF01538073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701–712. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Rooy EC, Toner BB, Maunder RG, et al. Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a clinical population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1816–1821. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, Nealon-Woods M. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1224–1232. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Looper KJ, Kirmayer LJ. Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:373–378. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(04)00447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wyke RJ, Edwards FC, Allan RN. Employment problems and prospects for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1988;29:1229–1235. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.9.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salter M. Stoma care. Overcoming the stigma. Nurs Times. 1990;86:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayberry MK, Probert C, Srivastava E, Rhodes J, Mayberry JF. Perceived discrimination in education and employment by people with Crohn's disease: a case control study of educational achievement and employment. Gut. 1992;33:312–314. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moody GA, Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Mayberry JF. The attitude of employers to people with inflammatory bowel disease. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:459–460. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90306-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayberry JF. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on educational achievements ad work prospects. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:S34–36. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moody G, Eaden JA, Mayberry JF. Social implications of childhood Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;128:S43–S45. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moskovitz DN, Maunder RG, Cohen Z, McLeod RS, MacRae H. Coping behavior and social support contribute independently to quality of life after surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:517–521. doi: 10.1007/BF02237197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levenstein S, Li Z, Almer S, Barbosa A, et al. Cross-cultural variation in disease-related concerns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1822–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daniel JM. Young adults' perceptions of living with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2002;25:83–94. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krause M. The transformation of social representations of chronic disease in a self-help group. J Health Psychol. 2003;8:599–615. doi: 10.1177/13591053030085010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finlay DG, Basu D, Sellin JH. Effect of race and ethnicity on perceptions of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:503–507. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith DM, Loewenstein G, Rozin P, Sherriff RL, Ubel PA. Sensitivity to disgust, stigma, and adjustment to life with a colostomy. J Res Pers. 2007;41:787–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simmons KL, Smith JA, Bobb KA, Liles LL. Adjustment to colostomy: stoma acceptance, stoma care self-efficacy and interpersonal relationships. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:627–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voth J, Sirois FM. The role of self-blame and responsibility in adjustment to inflammatory bowel disease. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:99–108. doi: 10.1037/a0014739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dibley L, Norton C. Experiences of fecal incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: self-reported experiences among a community sample. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1450–1462. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281327f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Czuber-Dochan W, Dibley LB, Terry H, Ream E, Norton C. The experience of fatigue in people with inflammatory bowel disease: an exploratory study. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:1987–1999. doi: 10.1111/jan.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taft TH, Ballou S, Keefer L. A preliminary evaluation of internalized stigma and stigma resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Health Psychol. 2013;18:451–460. doi: 10.1177/1359105312446768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bredin F, Darvell M, Nathan I, Terry H. Healthcare professionals' perceptions of fatigue experienced by people with IBD. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:835–844. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frohlich DO. Support often outweights stigma for people with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2014;37:126–136. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saunders B. Stigma, deviance and morality in young adults' accounts of inflammatory bowel disease. Sociol Health Illn. 2014;36:1020–1036. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernhofer EI, Masina VM, Sorrell J, Modic MB. The pain experience of patients hospitalized with inflammatory bowel disease: a phenomenological study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017;40:200–207. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rohde JA, Wang Y, Cutino CM, et al. Impact of disease disclosure on stigma: an experimental investigation of college students' reactions to inflammatory bowel disease. J Health Commun. 2018;23:91–97. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1392653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gamwell KL, Baudino MN, Bakula DM, et al. Perceived illness stigma, thwarted belongingness, and depressive symptoms in youth with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:960–965. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dibley L, Williams E, Young P. When family don't acknowledge: a hermeneutic study of the experience of kinship stigma in community-dwelling people with inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Health Res. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1049732319831795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Werner EE. Overcoming the odds. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15:131–136. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199404000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Southwick SM, Charney DS. The science of resilience: implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. Science. 2012;338(6103):79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1222942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Osorio C, Probert T, Jones E, Young AH, Robbins I. Adapting to stress: understanding the neurobiology of resilience. Behav Med. 2017;43:307–322. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2016.1170661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ungar M. Designing resilience research: Using multiple methods to investigate risk exposure, promotive and protective processes, and contextually relevant outcomes for children and youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;96:104098. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Werner EE. Children and war: risk, resilience, and recovery. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24:553–558. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Macmillian Dictionnary (2019) Origin of the word resilient. https://www.macmillandictionaryblog.com/resilient

- 71.American Psychological Association (2019) What is resilience. APA. https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience

- 72.Cal SF, Sá LRd, Glustak ME, Santiago MB. Resilience in chronic diseases: a systematic review. Cogent Psychol. 2015;2:1024928. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2015.1024928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quiceno JM, Venaccio S. Resilience: a perspective from the chronic disease in the adult population. Pensam Psicol. 2011;9:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gheshlagh GR, Sayehmiri K, Ebadi A, Dalvandi A, Dalvand S, Tabrizi NK. Resilience of patients with chronic physical diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18:e38562. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.38562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Matzka M, Mayer H, Kock-Hodi S, Moses-Passini C, Dubey C, Jahn P, Schneeweiss S, Eicher M. Relationship between resilience, psychological distress and physical activity in cancer patients: a cross-sectional observation study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dale SK, Cohen MH, Kelso GA, Cruise RC, Weber KM, Watson C, Burke-Miller JK, Brody LR. Resilience among women with HIV: Impact of silencing the self and socioeconomic factors. Sex Roles. 2014;70:221–231. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0348-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Corazza GR, Formagnana P, Lenti MV. Bringing complexity into clinical practice: an internistic approach. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;61:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: what are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12:65–76. doi: 10.1002/mpr.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M, Aslaksen PM, Flaten MA. Resilience as a moderator of pain and stress. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Connor KM, Davidson JR (2014) Translations of the CD-RISC. Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale. https://www.connordavidson-resiliencescale.com/translations.php

- 84.Farrell D, McCarthy G, Savage E. Self-reported symptom burden in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:315–322. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Skrastins O, Fletcher PC. "One flare at a time": adaptive and maladaptive behaviors of women coping with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Nurse Spec. 2016;30:E1–E11. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luo D, Lin Z, Shang XC, Li S. "I can fight it!": a qualitative study of resilience in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Acciari AS, Leal RF, Coy CSR, Dias CC, Ayrizono MLS. Relationship among psychological well-being, resilience and coping with social and clinical features in Crohn's disease patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2019;56:131–140. doi: 10.1590/s0004-2803.201900000-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dur M, Sadlonova M, Haider S, Binder A, Stoffer M, Coenen M, Smolen J, Dejaco C, Kautzky-Willer A, Fialka-Moser V, Moser G, Stamm TA. Health determining concepts important to people with Crohn's disease and their coverage by patient-reported outcomes of health and wellbeing. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kilpatrick LA, Gupta A, Love AD, et al. Neurobiology of psychological resilience in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:S-774. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(15)32639-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taylor K, Scruggs PW, Balemba OB, Wiest MM, Vella CA. Associations between physical activity, resilience, and quality of life in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118:829–836. doi: 10.1007/s00421-018-3817-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sehgal P, Abrahams E, Ungaro RC, Dubinsky M, Keefer L. Resilience is associated with lower rates of depression and anxiety, and higher quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:S797–S798. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(17)32759-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scardillo J, Dunn KS, Piscotty R., Jr Exploring the relationship between resilience and ostomy adjustment in adults with a permanent ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2016;43:274–279. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hwang JH, Yu CS. Depression and resilience in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients with ostomy. Int Wound J. 2019;16:62–70. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sirois FM, Hirsch JK. A longitudinal study of the profiles of psychological thriving, resilience, and loss in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22:920–939. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Melinder C, Hiyoshi A, Fall K, Halfvarson J, Montgomery S (2017) Stress resilience and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study of men living in Sweden. BMJ Open 7:e014315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Skrautvol K, Naden D. Tolerance limits, self-understanding, and stress resilience in integrative recovery of inflammatory bowel disease. Holist Nurs Pract. 2017;31:30–41. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sirois FM. Health-related self-perceptions over time and provider-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use in people with inflammatory bowel disease or arthritis. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carlsen K, Haddad N, Gordon J, Phan BL, Pittman N, Benkov K, Dubinsky MC, Keefer L. Self-efficacy and resilience are useful predictors of transition readiness scores in adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:341–346. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carlsen K, Hald M, Dubinsky MC, Keefer L, Wewer V. A personalized eHealth transition concept for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: design of intervention. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2019;2:e12258. doi: 10.2196/12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rossi A, Galderisi S, Rocca P, Bertolino A, Rucci P, Gibertoni D, Stratta P, Bucci P, Mucci A, Aguglia E, Amodeo G, Amore M, Bellomo A, Brugnoli R, Caforio G, Carpiniello B, Dell'Osso L, di Fabio F, di Giannantonio M, Marchesi C, Monteleone P, Montemagni C, Oldani L, Roncone R, Sacchetti E, Santonastaso P, Siracusano A, Zeppegno P, Maj M; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses (2017) Personal resources and depression in schizophrenia: the role of self-esteem, resilience and internalized stigma. Psychiatry Res 256:359–364 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Gottert A, Friedland B, Geibel S, Nyblade L, Baral SD, Kentutsi S, Mallouris C, Sprague L, Hows J, Anam F, Amanyeiwe U, Pulerwitz J. The people living with HIV (PLHIV) resilience scale: development and validation in three countries in the context of the PLHIV Stigma Index. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:172–182. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02594-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dibley L, Norton C, Whitehead E. The experience of stigma in inflammatory bowel disease: an interpretive (hermeneutic) phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:838–851. doi: 10.1111/jan.13492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cantoro L, Di Sabatino A, Papi C, Margagnoni G, Ardizzone S, Giuffrida P, Giannarelli D, Massari A, Monterubbianesi R, Lenti MV, Corazza GR, Kohn A. The time course of diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease over the last sixty years: an Italian multicentre study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:975–980. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Selinger CP, Lenti MV, Clark T, Rafferty H, Gracie D, Ford AC, OʼConnor A, Ahmad T, Hamlin PJ. Infliximab therapeutic drug monitoring changes clinical decisions in a virtual biologics clinic for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:2083–2088. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Naviglio S, Giuffrida P, Stocco G, Lenti MV, Ventura A, Corazza GR, Di Sabatino A. How to predict response to anti-tumour necrosis factor agents in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:797–810. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1494573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lenti MV, Selinger CP. Medication non-adherence in adult patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review and update of the determining factors, consequences and possible interventions. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:215–226. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1284587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Riva MA, Ferraina F, Paleari A, Lenti MV, Di Sabatino A. From sadness to stiffness: the spleen's progress. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:739–743. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Abbati G, Incerti F, Boarini C, Pileri F, Bocchi D, Ventura P, Buzzetti E, Pietrangelo A. Safety and efficacy of sucrosomial iron in inflammatory bowel disease patients with iron deficiency anemia. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:423–431. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Busti F, Marchi G, Girelli D. Iron replacement in inflammatory bowel diseases: an evolving scenario. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:349–351. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Giuffrida P, Aronico N, Rosselli M, Lenti MV, Cococcia S, Roccarina D, Saffioti F, Delliponti M, Thorburn D, Miceli E, Corazza GR, Pinzani M, Di Sabatino A. Defective spleen function in autoimmune gastrointestinal disorders. Intern Emerg Med. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02129-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lenti MV, Armuzzi A, Castiglione F, Fantini MC, Fiorino G, Orlando A, Pugliese D, Rizzello F, Vecchi M, Di Sabatino A, on behalf of IG-IBD Are we choosing wisely for inflammatory bowel disease care? The IG-IBD choosing wisely campaign. Dig Liv Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]