Abstract

Background

We aimed at reviewing design and realisation of perfusion/flow phantoms for validating quantitative perfusion imaging (PI) applications to encourage best practices.

Methods

A systematic search was performed on the Scopus database for “perfusion”, “flow”, and “phantom”, limited to articles written in English published between January 1999 and December 2018. Information on phantom design, used PI and phantom applications was extracted.

Results

Of 463 retrieved articles, 397 were rejected after abstract screening and 32 after full-text reading. The 37 accepted articles resulted to address PI simulation in brain (n = 11), myocardial (n = 8), liver (n = 2), tumour (n = 1), finger (n = 1), and non-specific tissue (n = 14), with diverse modalities: ultrasound (n = 11), computed tomography (n = 11), magnetic resonance imaging (n = 17), and positron emission tomography (n = 2). Three phantom designs were described: basic (n = 6), aligned capillary (n = 22), and tissue-filled (n = 12). Microvasculature and tissue perfusion were combined in one compartment (n = 23) or in two separated compartments (n = 17). With the only exception of one study, inter-compartmental fluid exchange could not be controlled. Nine studies compared phantom results with human or animal perfusion data. Only one commercially available perfusion phantom was identified.

Conclusion

We provided insights into contemporary phantom approaches to PI, which can be used for ground truth evaluation of quantitative PI applications. Investigators are recommended to verify and validate whether assumptions underlying PI phantom modelling are justified for their intended phantom application.

Keywords: Microcirculation, Perfusion imaging, Phantoms (imaging), Reference standards

Key points

Without a validated standard, interpretation of quantitative perfusion imaging can be inconclusive.

Perfusion phantom studies contribute to ground truth evaluation.

We systematically reviewed design and realisation of contemporary perfusion phantoms.

Assessed phantom designs are diverse and limited to single tissue compartment models.

Investigators are encouraged to adopt efforts on phantom validation, including verification with clinical data.

Background

Perfusion imaging (PI) is a powerful method for assessing and monitoring tissue vascular status, and alterations therein. Hence, PI is generally aimed at distinguishing healthy from ischemic and infarcted tissue. PI applications cover various imaging modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that can record perfusion parameters in a wide spread of tissues including brain, liver, and myocardial tissue. A distinction can be made between contrast-enhanced and non-contrast PI approaches. The pertinent signal intensity in tissue can be recorded as a function of time or after a time interval, called dynamic or static PI respectively. This systematic review focuses on dynamic PI, as this approach enables quantitative analysis and absolute quantification of perfusion. In dynamic PI, it is possible to construct mathematical models that fit image data with model parameters in order to explain observed response functions in tissue. For example, time-intensity curves highlight the distribution of contrast material into the tissue over time. Model outcomes include computation of absolute blood flow (BF), blood volume (BV), and/or mean transit times (MTTs) [1]. Multiple BF models of tissue perfusion exist, including model-based deconvolution, model-independent singular value decomposition and maximum upslope models [2]. These BF models are increasingly used in addition to standard semiquantitative analysis, as these show potential towards better accuracy and standardised assessment of perfusion measures [3–5].

Without a validated standard, interpretation of quantitative results can be challenging. Validation and/or calibration of absolute perfusion measures is required to ensure unrestricted and safe adoption in clinical routine [6–8]. Validation approaches include in vivo, ex vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies and combinations hereof. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages, and may differ in level of representativeness, controllability of variables, and practical applicability. Our focus was on in vitro studies, i.e., physical phantom studies. Phantom studies contribute to ground truth evaluation of single aspects on quantitative PI applications in a simplified, though controlled, environment. Phantom studies also allow for the comparison and optimisation of imaging protocols and analysis methods. We hereby observe a shift from the use of static to dynamic perfusion phantoms (i.e., with a flow circuit), as the latter enables in-depth evaluation of time-dependent variables.

In general, it can be challenging to translate findings from phantom studies into clinical practice. For example, it can be questionable whether certain choices and simplifications in perfusion phantom modelling are justified. Intra- and interdisciplinary knowledge sharing on phantom designs, experimental findings, and clinical implications can be used to substantiate this. Hence, this systematic review presents an overview on contemporary perfusion phantoms for evaluation of quantitative PI applications to encourage best quantitative practices.

Methods

A systematic search on general and contemporary perfusion phantoms was conducted using Scopus database online, which includes MEDLINE and EMBASE. The query included “perfusion”, “flow”, and “phantom”. Inclusion was limited to English written articles and reviews published between January 1999 and December 2018.

Two investigators independently screened titles and abstracts (M.E.K. and M.J.W.G.), whereby in vivo, ex vivo and in silico related perfusion studies were excluded, even as non-related in vitro studies (e.g., static and large-vessel phantoms). We hereby note that thermal and optical PI techniques fall outside the scope of this review. The same investigators performed full-text screening and analysis. Study inclusion required incorporation of microvascular flow simulation and we excluded single-vessel phantom studies. In addition, references were scrutinised on cross-references. Observer differences were resolved by discussion.

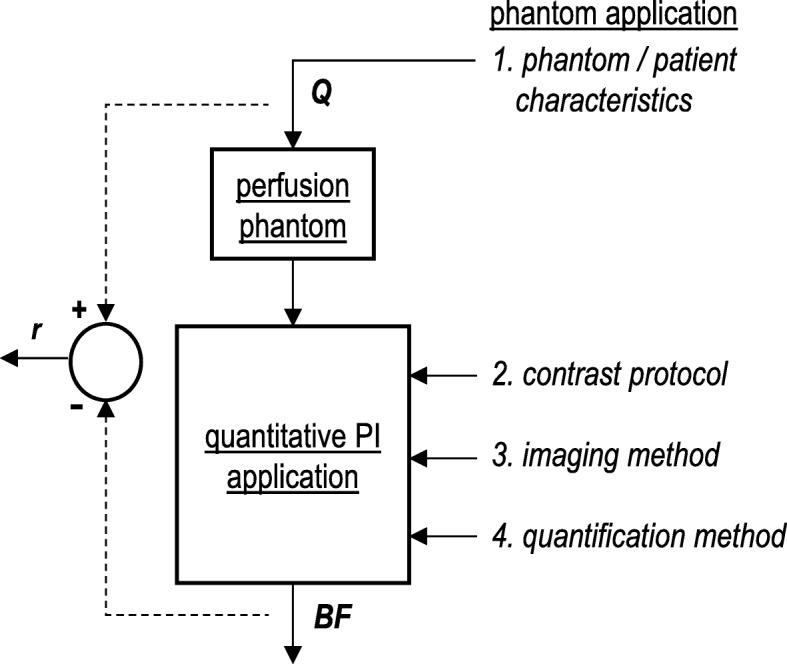

The perfusion phantom overview concerns three main aspects regarding ground truth evaluation of quantitative PI, as schematically depicted in Fig. 1. Details on perfusion phantom design, studied PI application and overall phantom application were extracted from each paper. We categorised phantom design features in terms of simulated anatomy, physiology, and pathology. Anatomy simulation lists information on the studied tissue type and surrounding tissue. Physiology simulation contains the used phantom configuration, the corresponding tissue-compartment model, the applied flow profile and range, and the simulation of motion (e.g., breathing and cardiac motion). Pathology simulation indicates the presence of perfusion deficit simulation.

Fig. 1.

System representation of ground truth validation process of quantitative perfusion imaging (PI). The diverse input variables that might affect quantitative perfusion outcomes are shown on the right. Q serves as an example input variable and refers to set phantom flow in mL/min. BF is accordingly the computed blood flow in mL/min (system output), and r is the residual between both. The latter can be translated into a measure of accuracy. The figure summarises the central topics of this review paper

Extracted parameters for the studied PI application encounters the used contrast protocol, imaging system, and BF model. We also listed the studied input and output variables for the diverse phantom applications. Input variables were categorised as follows: (1) phantom/patient characteristics; (2) contrast protocol, if applicable; (3) imaging method; and (4) flow quantification method (see Fig. 1). Output variables included the following perfusion measures: arterial input function; tissue response function; MTT; BV; and BF. If mentioned by the authors, we listed published results on phantom performance, which describes the relation between the “ground truth” flow measure and the obtained quantitative PI outcomes. Finally, we documented in which studies phantom data are compared with human, animal, or mathematical data, and which phantoms are commercially available.

Results

Phantom data assessment

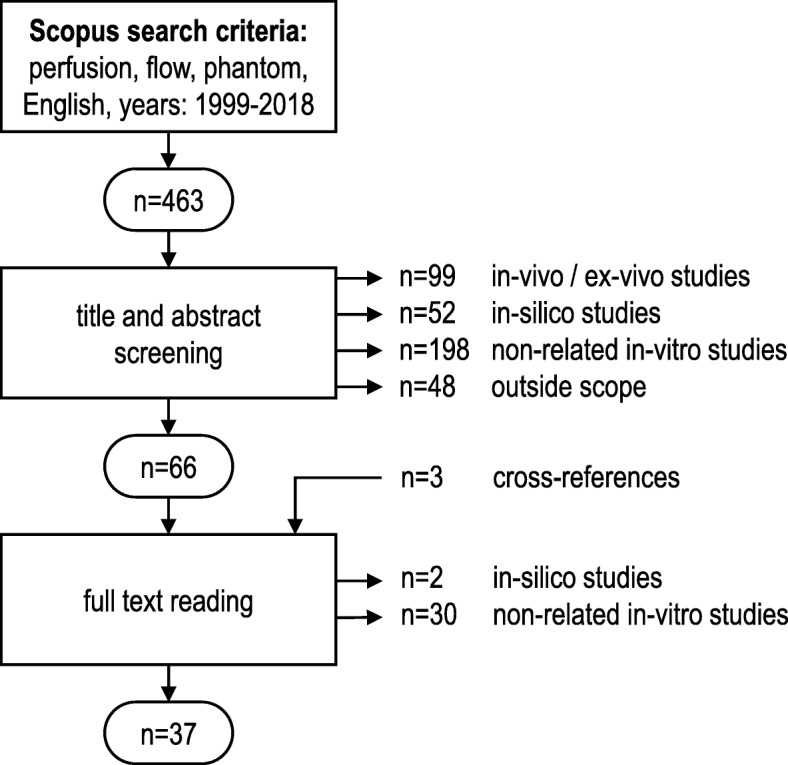

We have retrieved 463 articles using Scopus, of which 397 were rejected after abstract screening and another 32 after full-text reading. The search resulted in 37 accepted articles including cross-references (Fig. 2). Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4 summarise our main findings on phantom designs and applications in diverse PI domains.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of study selection process

Table 1.

Design and realisation of general perfusion phantoms in quantitative perfusion imaging (PI)

| Publication | Phantom design | PI application | Phantom application | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st author, year [reference] |

Configuration (see Fig. 3) |

Flow profile | Flow range | Motion simulation | Surrounding tissue simulation | Perfusion deficit simulation | Imaging modality | Contrast protocol | Blood flow model | Input variables | AIF | RF | MTT | BV | BF | Data comparison | Commercial |

| General phantoms | |||||||||||||||||

| Andersen, 2000 [9] | 1A | c | 0.015–0.57 C | MRI | FAIR | 1, 4 | x | x | |||||||||

| Brauweiler, 2012 [10] | 1A | p | 180 A | x | CT | x | 2, 3 | x | x | ||||||||

| Li, 2002 [11] | 1A, 2B | c | 500–1300 A | US | x | MBD | 1 | x | x | x | x | M | |||||

| Peladeau-Pigeon, 2013 [12] | 1B | c, p | 210–450 A | x | MRI, CT | x | MBD (Fick, modif. Toft) | 1–3 | x | x | x | M | x | ||||

| Driscoll, 2011 [13] | 1B | p | 150–270 A | x | CT | x | 1–3 | x | x | x | |||||||

| Kim, 2016 [14] | 2B | c | 0–2 A | x | US | 1, 3 | x | ||||||||||

| Anderson, 2011 [15] | 2B | c | 50 A | MRI | x | 1 | x | ||||||||||

| Meyer-Wiethe, 2005 [16] | 2B | c | 4.5–36 A | US | x | Replenishment | 1, 3, 4 | x | |||||||||

| Veltmann, 2002 [17] | 2B | c | 10–45 A | US | x | Replenishment | 1, 2 | x | x | ||||||||

| Kim, 2004 [18] | 2B, 3A | p | 0.09, 1.6–1.8 C | MRI | 1-TCM | 1, 3 | x | ||||||||||

| Lee, 2016 [19] | 3A | c | 0–3 A | MRI | DWI | 1 | x | ||||||||||

| Chai, 2002 [20] | 3A | c | 50–300 A | MRI | ASL | 1 | x | H | |||||||||

| Potdevin, 2004 [21] | 3A | p | 2.6–10.4 A | x | US | x | Replenishment | 1, 2 | x | x | M | ||||||

| Lucidarme, 2003 [22] | 2B | p | 100–400 A | US | x | Replenishment | 1 | x | A | ||||||||

c Continuous, p Pulsatile, A in mL/min, B in mL/min/g, C in cm/s, FAIR Flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery, MBD Model-based deconvolution, 1-TCM Single tissue compartment model, DWI Diffusion weighted imaging, ASL Arterial spin labelling, SVD Singular value decomposition, MSM Maximum slope model, 1 = Phantom/patient characteristics, 2 = Contrast protocol, 3 = Imaging method, 4 = Flow quantification method, AIF Arterial input function, RF Response function, MTT Mean transit time, BV Blood volume, BF Blood flow, H Human, A Animal, M Mathematical

Table 2.

Design and realisation of brain perfusion phantoms for quantitative perfusion imaging (PI)

| Publication | Phantom design | PI application | Phantom application | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st author, year [reference] |

Configuration (see Fig. 3) |

Flow profile | Flow range | Motion simulation | Surrounding tissue simulation | Perfusion deficit simulation | Imaging modality | Contrast protocol | Blood flow model | Input variables | AIF | RF | MTT | BV | BF | Data comparison | Commercial |

| Brain phantoms | |||||||||||||||||

| Boese, 2013 [23] | 1A | p | 800 A | x | CT | x | MBD | 1–3 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Hashimoto, 2018 [24] | 2A | c | 60 A | x | CT | x | SVD | 2, 3 | x | x | x | M | |||||

| Suzuki, 2017 [25] | 2A | c | 60 A | x | CT | x | SVD | 3 | x | x | x | x | x | M | |||

| Noguchi, 2007 [26] | 2A | c | 0–2.16 C | MRI | ASL | 1 | x | x | |||||||||

| Wang, 2010 [27] | 2B | c | 45–180 A | MRI | ASL | 1 | x | x | M, H | ||||||||

| Cangür, 2004 [28] | 2B | c | 1.8–21.6 A | x | US | x | 1 | x | |||||||||

| Klotz, 1999 [29] | 2B | c | 50–140 A | x | CT | x | MSM | 1 | x | x | x | H | |||||

| Claasse, 2001 [30] | 2B | p | 180–540 A | US | x | MBD | 1, 2 | x | x | A | |||||||

| Mathys, 2012 [31] | 3A | c | 200–600 A | x | CT | x | SVD, MSM | 1–4 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Ebrahimi, 2010 [32] | 3A | c | 012–1.2 A | MRI | x | SVD | 1 | x | x | x | x | x | M | ||||

| Ohno, 2017 [33] | 3B | p | 240–480 A | MRI | ASL | 1 | x | x | |||||||||

c Continuous, p Pulsatile, A in mL/min, B in mL/min/g, C in cm/s, FAIR Flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery, MBD Model-based deconvolution, 1-TCM Single tissue compartment model, DWI Diffusion weighted imaging, ASL Arterial spin labelling, SVD Singular value decomposition, MSM Maximum slope model, 1 = Phantom/patient characteristics, 2 = Contrast protocol, 3 = Imaging method, 4 = Flow quantification method, AIF Arterial input function, RF Response function, MTT Mean transit time, BV Blood volume, BF Blood flow, H Human, A Animal, M Mathematical

Table 3.

Design and realisation of general myocardial phantoms for quantitative perfusion imaging (PI)

| Publication | Phantom design | PI application | Phantom application | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st author, year [reference] |

Configuration (see Fig. 3) |

Flow profile | Flow range | Motion simulation | Surrounding tissue simulation | Perfusion deficit simulation | Imaging modality | Contrast protocol | Blood flow model | Input variables | AIF | RF | MTT | BV | BF | Data comparison | Commercial |

| Myocardial phantoms | |||||||||||||||||

| Zarinabad, 2014 [34] | 2A | c | 1–5 B | MRI | x | MBD (Fermi) | 1, 4 | x | x | x | M, H | ||||||

| Chiribiri 2013 [8] | 2A | c | 1–10 B | MRI | x | 1, 2 | x | x | |||||||||

| Zarinabad, 2012 [35] | 2A | c | 1–5 B | MRI | x | MBD (Fermi), SVD | 1, 3, 4 | x | x | x | M, H | ||||||

| O’Doherty, 2017 [36] | 2A | c | 3 B | PET,MRI | x | 1-TCM | 2, 3 | x | x | x | |||||||

| O’Doherty, 2017 [37] | 2A | c | 1–5 B | PET,MRI | x | 1-TCM | 1, 3 | x | x | x | |||||||

| Otton, 2013 [38] | 2A | c | 2–4 B | MR,CT | x | 1, 3 | x | x | |||||||||

| Ressner, 2006 [39] | 3A | c | 5–10 C | x | US | x | 1, 2 | x | x | H | |||||||

| Ziemer, 2015 [40] | 3A | p | 0.96–2.49 B | x | CT | x | MSM | 1, 4 | x | x | x | ||||||

c Continuous, p Pulsatile, A in mL/min, B in mL/min/g, C in cm/s, FAIR Flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery, MBD Model-based deconvolution, 1-TCM Single tissue compartment model, DWI Diffusion weighted imaging, ASL Arterial spin labelling, SVD Singular value decomposition, MSM Maximum slope model, 1 = Phantom/patient characteristics, 2 = Contrast protocol, 3 = Imaging method, 4 = Flow quantification method, AIF Arterial input function, RF Response function, MTT Mean transit time, BV Blood volume, BF Blood flow, H Human, A Animal, M Mathematical

Table 4.

Design and realisation of finger, liver, and tumour perfusion phantoms for quantitative perfusion imaging (PI)

| Publication | Phantom design | PI application | Phantom application | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st author, year [reference] |

Configuration (see Fig. 3) |

Flow profile | Flow range | Motion simulation | Surrounding tissue simulation | Perfusion deficit simulation | Imaging modality | Contrast protocol | Blood flow model | Input variables | AIF | RF | MTT | BV | BF | Data comparison | Commercial |

| Finger phantom | |||||||||||||||||

| Sakano, 2015 [41] | 2B | c | 6–30 A | US | x | 1, 3 | x | ||||||||||

| Liver phantoms | |||||||||||||||||

| Gauthier, 2011 [42] | 2B | c | 130 A | US | x | 3 | x | x | H | ||||||||

| Low, 2018 [43] | 3A | - | 20.5 A | CT | x | 1 | |||||||||||

| Tumour phantom | |||||||||||||||||

| Cho, 2012 [44] | 3A,3B | p | - | MRI | DWI | 1, 4 | x | ||||||||||

c Continuous, p Pulsatile, A in mL/min, B in mL/min/g, C in cm/s, FAIR Flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery, MBD Model-based deconvolution, 1-TCM Single tissue compartment model, DWI Diffusion weighted imaging, ASL Arterial spin labelling, SVD Singular value decomposition, MSM Maximum slope model, 1 = Phantom/patient characteristics, 2 = Contrast protocol, 3 = Imaging method, 4 = Flow quantification method, AIF Arterial input function, RF Response function, MTT Mean transit time, BV Blood volume, BF Blood flow, H Human, A Animal, M Mathematical

Phantom design

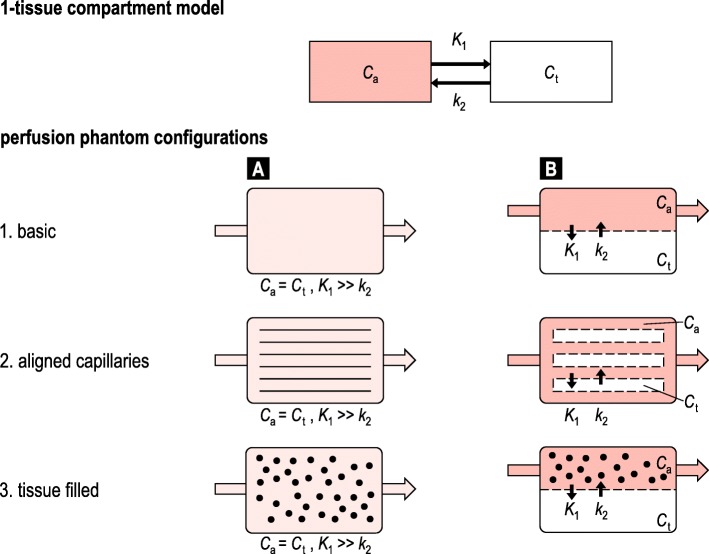

Anatomically, the phantoms simulate perfusion of various tissue types, including organ specific tissue (brain, n = 11 articles; myocardial, n = 8; liver, n = 2; tumour, n = 1; finger, n = 1) and non-specific tissue (n = 14). Several phantoms additionally mimic surrounding tissue (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4). All phantoms comprise a simplified “physiologic” model of perfusion that can be translated into a single tissue compartment model. Figure 3 schematically illustrates the basics of six distinguished phantom configurations, which specify three phantom types: basic (n = 6 articles); aligned capillaries (n = 22); and tissue filled (n = 12). The observed phantom designs simulate the microvasculature and tissue as one combined volume (n = 23 articles) or two physically separated volumes (n = 17) (e.g., via a semipermeable membrane). Note that papers can present more than one phantom, and phantom designs may slightly differ from the schematic representations.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the 1-tissue compartment model and six derived phantom configurations. A distinction is made between three phantom types: basic, aligned capillaries and tissue filled (black spheres). Moreover, the microvasculature and tissue can be simulated as one combined (a) or two separated volumes (b) (e.g., via a porous membrane). Cp and Ct represent the concentration of the compound of interest (is being imaged) in the simulated blood plasma and tissue, respectively. K1 and k2 comprise the two transfer coefficients. Formation of in- and outgoing flow (arrow) and compartment flow varies per individual phantom design

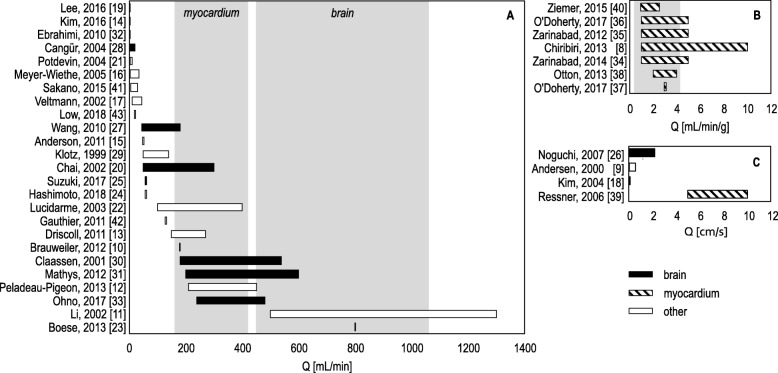

Basic phantoms generally consist of a single volume with ingoing and outgoing tubes, disregarding physiological simulation of microcirculation and tissue. In capillary phantoms, the microvasculature is simulated as a volume filled with unidirectional aligned hollow fibres or straws (e.g., a dialysis cartridge). The amount, diameter, and permeability of these fibres vary. Tissue-filled phantoms incorporate tissue-mimicking material inside the volume, which subsequently leads to formation of a “microvasculature”. Used materials include sponge [20, 21, 33, 44], (micro)beads [19, 31, 40], gel [18, 39], and printed microchannels [32, 43]. Remarkably, in most studies, fluid exchange between simulated microvasculature and tissue (i.e., transfer rates K1 and k2) was uncontrollable, except for the study performed by Ohno et al. [33]. In this study, the compliance of the capacitor space could be altered to control k2 to some extent. Low et al. [43] and Ebrahim et al. [32] have mathematically simulated the desired phantom flow configuration, before printing the microchannels. However, these models did not simulate fluid exchange between microvasculature and tissue. Continuous flow was applied in 26 phantom studies and pulsatile/peristaltic flow in 11 phantom studies. Flow settings vary per study and target organ and are presented in three different units (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4). In case of brain and myocardial perfusion phantom modelling, flow experiments do not always cover the whole physiological range (Fig. 4). In addition, we observed two phantom studies that incorporated clutter motion (i.e., small periodic motion), but no studies included breathing or cardiac motion (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4). Regional perfusion deficit simulation (pathology) was only executed by Boese et al. [23]. Several studies mimicked some sort of global perfusion deficits by reducing the total flow or perfusion rate.

Fig. 4.

Overview of used flow ranges and units in assessed perfusion phantom studies. (a) shows the studied flow ranges in mL/min, (b) in mL/min/g, and (c) in cm/s. The grey blocks represent physiological flow ranges for brain and myocardial tissue [45, 46]

Studied PI applications

Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4 depict 17 studies focusing on MRI, 11 on ultrasound imaging, 11 on CT, and 2 on PET; 4 studies presented a direct comparison of MRI with PET or CT. A contrast-enhanced protocol was used in 28 studies. The used BF model for perfusion quantification varies per imaging modality and contrast protocol.

Phantom applications

Variables related to phantom/patient characteristics (n = 32), contrast protocol (n = 12), imaging method (n = 16), and quantification method (n = 7) were studied in relation to various quantitative perfusion measures (Table 1). Most papers describe the influence of flow settings on quantitative perfusion outcomes, followed by variation in contrast volume and acquisition protocol. Several studies compare outcomes to human/patient data (n = 7), animal data (n = 2), and mathematical simulations (n = 9) (Table 1). In addition, we have identified one commercially available perfusion phantom that is described by Driscoll et al. [13] and applied by Peladeau-Pigeon et al. [12]. The relation between the “ground truth” flow measure and quantitative PI outcomes is summarised in Table 5. Remarkable is the diversity in used measures of perfusion and comparison (e.g., absolute errors, correlations statistics).

Table 5.

Design and realisation of brain perfusion phantoms for quantitative perfusion imaging (PI)

| 1st author, year [reference] | Perfusion measure(s) | Phantom performance | Q |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct comparison with Q | |||

| Klotz, 1999 [29] | BF | r = 0.990 | 50–140 mL/min |

| Wang, 2010 [27] | BF | r > 0.834 | 45–180 mL/min |

| Mathys, 2012 [31] | BF | r = 0.995 | 200–600 mL/min |

| Peladeau-Pigeon, 2013 [12] | BF | r = 0.992 | 210–450 mL/min |

| Ohno, 2017 [33] | BF | r > 0.90 | 240–480 mL/min |

| Ziemer, 2015 [40] | BF | r = 0.98 | 0.96–2.49 mL/g/min |

| O’Doherty, 2017 [36] | BF | r = 0.99 | 1–5 mL/g/min |

| Andersen, 2000 [9] | BF |

ε ≈ 0.015 ± 0.03 cm/s ε ≈ 0.001 ± 0.03 cm/s |

0.015 ± 0.002 cm/s 0.570 ± 0.003 cm/s |

| Ressner, 2006 [39] | BF |

ε > 40% ε < 20% |

1–3 cm/s 5–7 cm/s |

| Zarinabad, 2012 [35] | BF |

ε = 0.007 ± 0.002 mL/g/min ε = 0.23 ± 0.26 ml/g/min |

0.5 mL/g/min 5 mL/g/min |

| Zarinabad, 2014 [34] | BF |

ε < 0.03 mL/g/min ε < 0.05 ml/g/min |

2.5–5 mL/g/min 1–2.5 mL/g/min |

| Suzuki, 2017 [25] | BF | ε ≈ 0.0589 ± 0.0108 mL/g/min | 0.1684 mL/g/min |

| Hashimoto, 2018 [24] | BF | ε ≈ 0.0446 ± 0.0130 mL/g/min | 0.1684 mL/g/min |

| Ebrahimi, 2019 [32] | BF | BF/Q > 0.6 | 0.12–1.2 mL/min |

| Indirect comparison with Q | |||

| Veltmann, 2002 [17] | rkin | r > 0.984, χ2 < 0.019 | 10–45 mL/min |

| Chai, 2002 [20] | ∆SI ratio | r = 0.995 | 50–300 mL/min |

| Cangür, 2004 [28] |

TTP PSI AUC PG FWHM |

r = -0.964 r = 0.683 r = 0.668 r = 0.907 r = -0.63 |

1.8–21.6 mL/min |

| Myer-Wiethe, 2005 [16] | ∆SI | r = 0.99 | 4.5–36 mL/min |

| Lee, 2016 [19] | fp | r > 0.838 | 1–3 mL/min |

| O’Doherty, 2017 [36] | SI |

r = 0.99 r = 0.99 |

1–5 mL/g/min (MRI) 1.2–5.1 mL/g/min (MRI vs PET) |

| Kim, 2016 [14] | AUC | Efficiency <50% | 0.1–2.0 mL/min |

| Claassen, 2001 [30] | AUC, PSI, MTT | No clear correlation with Q | |

Phantom performance is predominantly listed in correlation statistics (r, χ2) and absolute errors (ε). A distinction is made between direct and indirect comparison with a “ground truth” flow measure (Q), which consists of theoretical or experimental values. BF Blood flow, TTP Time to peak, MTT Mean transit time, AUC Area under the curve, (P)SI Peak signal intensity, fp Perfusion fraction, rkin Replenishment kinetics, FWHM Full width at half maximum, PG Positive gradient

Discussion

A systematic search of the literature (from 1999 to 2018) was performed on contemporary perfusion phantoms. Detailed information was provided on three main aspects for ground truth evaluation of quantitative PI applications. We have elaborated on thirty-seven phantom designs, whereby focusing on anatomy, physiology and pathology simulation. In addition, we have listed the imaging system, contrast protocol and BF model for the studied PI applications. Finally, we have documented for each phantom application the investigated input and output variables, data comparison efforts and commercial availability. Hence, this review presents as main result an overview on perfusion phantom approaches and emphasises on the choices and simplifications in phantom design and realisation.

Although perfusion phantom modelling involves various tissues and applies to divers PI applications, we observe similarities in overall phantom designs and configurations. These configurations can be categorised in three types (6/40 basic, 22/40 capillary, and 12/40 tissue filled) and two representations of microvasculature and tissue (23/40 as one combined and 17/40 as two separated compartments). Differences in these six phantom configurations are reflected in the resulting flow dynamics, e.g., how a contrast material is distributed and how long it stays inside the simulated organ tissue. None of the assessed phantoms could control inter-compartmental fluid exchange. Ideally, one would be able to fine-tune the exact flow dynamics in perfusion phantom modelling to achieve patient realistic (and contrast material specific) response function simulation. The required level of representativeness depends on the intended analyses, being closely related to the input parameters and boundary conditions of the BF model used. Since all assessed phantoms are limited to single tissue compartment models, phantom validation of higher order BF models should be performed with caution. It is generally important to verify whether assumptions in phantom modelling are justified for the intended phantom application. This also concerns decisions regarding motion, pulsatile flow and perfusion deficit simulation. For example, in myocardial perfusion modelling it could be relevant to incorporate respiratory and cardiac motion for certain analyses [47, 48], while for other tissues “motion” could be disregarded more easily.

The need for standardisation and validation of (quantitative) PI applications is widely recognised [49, 50]. Perfusion phantom studies contribute to this endeavour, since these studies enable direct comparison between imaging systems and protocols. We only observed one commercial perfusion phantom in our search result. We foresee an increased clinical impact when phantoms become validated and widely available. In our opinion, phantom validation efforts are sometimes reported insufficiently and ambiguously. The concept of phantom validation can be difficult, since it is application-dependent and prone to subjectivity. The latter becomes apparent in the use of the words “considered”, “reasonable”, and “acceptable” (by whom, to whom, according to which criteria?) [51]. We therefore suggest to use Sargent’s theory on model verification and validation [52]. Van Meurs’ interpretation of this theory, including a practical checklist, is also applicable to physical, biomedical models (in adjusted form) [51]. For example, according to the checklist, investigators should verify whether the applied flow range covers the full physiological range. Our results (see Fig. 4) show great diversity in measured flow ranges. In addition, investigators are advised to consult physiologists and clinicians along the process, and compare findings with clinical data. In nine studies, phantom data are indeed compared with human or animal perfusion data (see Table 1).

When analysing phantom results, we noticed that investigators use different measures to evaluate quantitative PI outcomes, which hampers comparability (see Table 5). Some investigators express the relation between quantitative PI outcomes and the “ground truth” flow in correlation statistics or plots and others in absolute errors. Due to the diversity in outcome measures, applied flow ranges, and amount of measurements carried out, interpretation of these results should be handled with caution. A uniform, unambiguous measure to evaluate both phantom validity and the accuracy and precision of quantitative PI outcomes is desired.

This study has limitations. Our search was limited to articles published between 1999 and 2018, yet we are aware that the development and use of perfusion phantoms date further back. Contemporary studies build on these designs, which makes it relevant to elaborate on perfusion phantom experiments in advanced PI systems. Furthermore, we have decided to leave out detailed information on phantom design and fabrication (e.g., material choices and dimensions), since this information can be found in the appropriate references. Besides, phantom manufacturing is highly subject to change. We expect to see more three-dimensional printed perfusion phantoms in the coming years [43, 53, 54].

In conclusion, this systematic review provided insights into contemporary perfusion phantom approaches, which can be used for ground truth evaluation of quantitative PI applications. It is desirable to indicate an unambiguous measure for phantom validity. Furthermore, investigators in the field are recommended to perform measurements in the full physiological flow range, consult physiologists and clinicians along the process, and compare findings with clinical data. In this way, one can verify and validate whether made choices and simplifications in perfusion phantom modelling are justified for the intended application, hence increasing clinical impact.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with Willem van Meurs, PhD, regarding phantom modelling and validation.

Abbreviations

- BF

Blood flow

- BV

Blood volume

- CT

Computed tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MTT

Mean transit time

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PI

Perfusion imaging

- Q

“Ground truth” flow measure

Authors’ contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the design of this review paper. MEK has performed the systematic search, accompanied by MJWG in the paper selection process. MEK and CHS contributed to the interpretation of data. Finally, all authors have drafted the work and substantively revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

All authors declare not to have any financial or other relationships that could be seen as a competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marije E. Kamphuis, Email: m.e.kamphuis@utwente.nl

Marcel J. W. Greuter, Email: m.j.w.greuter@umcg.nl

Riemer H. J. A. Slart, Email: r.h.j.a.slart@umcg.nl

Cornelis H. Slump, Email: c.h.slump@utwente.nl

References

- 1.Barbier EL, Lamalle L, Decorps M. Methodology of brain perfusion imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:496–520. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eck BL, Muzic RF, Levi J, et al. The role of acquisition and quantification methods in myocardial blood flow estimability for myocardial perfusion imaging CT. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:185011. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aadab6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bengel FM. Leaving relativity behind. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;8:749–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sviri GE, Britz GW, Lewis DH, Newell DW, Zaaroor M, Cohen W. Dynamic perfusion computed tomography in the diagnosis of cerebral vasospasm. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:319–324. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000222819.18834.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morton G, Chiribiri A, Ishida M, et al. Quantification of absolute myocardial perfusion in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1546–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slomka P, Xu Y, Berman D, Germano G. Quantitative analysis of perfusion studies: strengths and pitfalls. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;71:3831–3840. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burrell S, MacDonald A (2006) Artifacts and pitfalls in myocardial perfusion imaging artifacts and pitfalls in myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med Technol 34:193–212 [PubMed]

- 8.Chiribiri A, Schuster A, Ishida M, et al. Perfusion phantom: an efficient and reproducible method to simulate myocardial first-pass perfusion measurements with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:698–707. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.K. Andersen Irene, Sidaros Karam, Gesmara Henrik, Rostrup Egill, Larsson Henrik B.W. A model system for perfusion quantification using FAIR. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2000;18(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(00)00136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brauweiler R, Eisa F, Hupfer M, Nowak T, Kolditz D, Kalender WA. Development and evaluation of a phantom for dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging. Invest Radiol. 2012;47:462–467. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318250a72c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li P-C, Yeh C-K, Wang S-W. Time-intensity-based volumetric flow measurements: an in vitro study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:349–358. doi: 10.1016/S0301-5629(01)00516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peladeau-Pigeon M, Coolens C. Computational fluid dynamics modelling of perfusion measurements in dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography: development, validation and clinical applications. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2013;58(17):6111–6131. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/17/6111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driscoll B., Keller H., Coolens C. Development of a dynamic flow imaging phantom for dynamic contrast-enhanced CT. Medical Physics. 2011;38(8):4866–4880. doi: 10.1118/1.3615058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim M, Abbey CK, Insana MF. Efficiency of U.S. tissue perfusion estimators. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2016;63:1131–1139. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2016.2571979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson JR, Ackerman JJH, Garbow JR. Semipermeable hollow fiber phantoms for development and validation of perfusion-sensitive MR methods and signal models. Concepts Magn Reson Part B Magn Reson Eng. 2011;39B:149–158. doi: 10.1002/cmr.b.20202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer-Wiethe K, Cangür H, Seidel G. Comparison of different mathematical models to analyze diminution kinetics of ultrasound contrast enhancement in a flow phantom. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veltmann C, Lohmaier S, Schlosser T, et al. On the design of a capillary flow phantom for the evaluation of ultrasound contrast agents at very low flow velocities. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:625–634. doi: 10.1016/S0301-5629(02)00499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim EJ, Kim DH, Lee SH, Huh YM, Song HT, Suh JS. Simultaneous acquisition of perfusion and permeability from corrected relaxation rates with dynamic susceptibility contrast dual gradient echo. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Cheong H, Song J-A, et al. Perfusion assessment using intravoxel incoherent motion-based analysis of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 2016;51:520–528. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chai JW, Chen JH, Kao YH, et al. Spoiled gradient-echo as an arterial spin tagging technique for quick evaluation of local perfusion. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:51–59. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potdevin TC, Fowlkes JB, Moskalik AP, Carson PL. Analysis of refill curve shape in ultrasound contrast agent studies. Med Phys. 2004;31:623–632. doi: 10.1118/1.1649534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucidarme O, Franchi-abella S, Correas J, Bridal SL, Kurtisovski E. Blood flow quantification with contrast-enhanced US : “Entrance in the Section” phenomenon — phantom and rabbit study. Radiology. 2003;228:473–479. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282020699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boese A, Gugel S, Serowy S, et al. Performance evaluation of a C-Arm CT perfusion phantom. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2012;8:799–807. doi: 10.1007/s11548-012-0804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto H, Suzuki K, Okaniwa E, Iimura H, Abe K, Sakai S. The effect of scan interval and bolus length on the quantitative accuracy of cerebral computed tomography perfusion analysis using a hollow-fiber phantom. Radiol Phys Technol. 2017;11:13–19. doi: 10.1007/s12194-017-0427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki Kazufumi, Hashimoto Hiroyuki, Okaniwa Eiji, Iimura Hiroshi, Suzaki Shingo, Abe Kayoko, Sakai Shuji. Quantitative accuracy of computed tomography perfusion under low-dose conditions, measured using a hollow-fiber phantom. Japanese Journal of Radiology. 2017;35(7):373–380. doi: 10.1007/s11604-017-0642-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noguchi T, Yshiura T, Hiwatashi A, et al. Quantitative perfusion imaging with pulsed arterial spin labeling: a phantom study. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2007;6:91–97. doi: 10.2463/mrms.6.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Kim SE, Dibella EVR, Parker DL. Flow measurement in MRI using arterial spin labeling with cumulative readout pulses - theory and validation. Med Phys. 2010;37:5801–5810. doi: 10.1118/1.3501881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cangür H, Meyer-Wiethe K, Seidel G. Comparison of Flow Parameters to Analyse Bolus Kinetics of Ultrasound Contrast Enhancement in a Capillary Flow Model. Ultraschall in der Medizin - European Journal of Ultrasound. 2004;25(06):418–421. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klotz E, König M. Perfusion measurements of the brain: using dynamic CT for the quantitative assessment of cerebral ischemia in acute stroke. Eur J Radiol. 1999;30:170–184. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(99)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claassen L, Seidel G, Algermissen C. Quantification of flow rates using harmonic grey-scale imaging and an ultrasound contrast agent: an in vitro and in vivo study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27:83–88. doi: 10.1016/S0301-5629(00)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathys Christian, Rybacki Konrad, Wittsack Hans-Jörg, Lanzman Rotem Shlomo, Miese Falk Roland, Macht Stephan, Eicker Sven, zu Hörste Gerd Meyer, Antoch Gerald, Turowski Bernd. A Phantom Approach to Interscanner Comparability of Computed Tomographic Brain Perfusion Parameters. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 2012;36(6):732–738. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31826801df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebrahimi B, Swanson SD, Chupp TE. A microfabricated phantom for quantitative MR perfusion measurements: validation of singular value decomposition deconvolution method. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010;57:2730–2736. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2055866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohno Naoki, Miyati Tosiaki, Chigusa Tomohiro, Usui Hikari, Ishida Shota, Hiramatsu Yuki, Kobayashi Satoshi, Gabata Toshifumi, Alperin Noam. Technical Note: Development of a cranial phantom for assessing perfusion, diffusion, and biomechanics. Medical Physics. 2017;44(5):1646–1654. doi: 10.1002/mp.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zarinabad N, Hautvast GLTF, Sammut E, et al. Effects of tracer arrival time on the accuracy of high-resolution (Voxel-wise) myocardial perfusion maps from contrast-enhanced first-pass perfusion magnetic resonance. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2014;61:2499–2506. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2322937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarinabad N, Chiribiri A, Hautvast GLTF, et al. Voxel-wise quantification of myocardial perfusion by cardiac magnetic resonance. Feasibility and Methods Comparison. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:1994–2004. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Doherty J, Chalampalakis Z, Schleyer P, Nazir MS, Chiribiri A, Marsden PK. The effect of high count rates on cardiac perfusion quantification in a simultaneous PET-MR system using a cardiac perfusion phantom. EJNMMI Phys. 2017;4:31. doi: 10.1186/s40658-017-0199-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Doherty J, Sammut E, Schleyer P, et al. Feasibility of simultaneous PET-MR perfusion using a novel cardiac perfusion phantom. Eur J Hybrid Imaging. 2017;1:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s41824-017-0008-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otton J, Morton G, Schuster A, et al. A direct comparison of the sensitivity of CT and MR cardiac perfusion using a myocardial perfusion phantom. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2013;7:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ressner M, Brodin LA, Jansson T, Hoff L, Ask P, Janerot-Sjoberg B. Effects of ultrasound contrast agents on doppler tissue velocity estimation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziemer BP, Hubbard L, Lipinski J, Molloi S. Dynamic CT perfusion measurement in a cardiac phantom. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;31:1451–1459. doi: 10.1007/s10554-015-0700-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakano Ryosuke, Kamishima Tamotsu, Nishida Mutsumi, Horie Tatsunori. Power Doppler signal calibration between ultrasound machines by use of a capillary-flow phantom for pannus vascularity in rheumatoid finger joints: a basic study. Radiological Physics and Technology. 2014;8(1):120–124. doi: 10.1007/s12194-014-0299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gauthier TP, Averkiou MA, Leen ELS. Perfusion quantification using dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound: the impact of dynamic range and gain on time-intensity curves. Ultrasonics. 2011;51:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Low Linda, Ramadan Sherif, Coolens Catherine, Naguib Hani E. 3D printing complex lattice structures for permeable liver phantom fabrication. Bioprinting. 2018;10:e00025. doi: 10.1016/j.bprint.2018.e00025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho GY, Kim S, Jensen JH, Storey P, Sodickson DK, Sigmund EE. A versatile flow phantom for intravoxel incoherent motion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1710–1720. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murthy Venkatesh L., Bateman Timothy M., Beanlands Rob S., Berman Daniel S., Borges-Neto Salvador, Chareonthaitawee Panithaya, Cerqueira Manuel D., deKemp Robert A., DePuey E. Gordon, Dilsizian Vasken, Dorbala Sharmila, Ficaro Edward P., Garcia Ernest V., Gewirtz Henry, Heller Gary V., Lewin Howard C., Malhotra Saurabh, Mann April, Ruddy Terrence D., Schindler Thomas H., Schwartz Ronald G., Slomka Piotr J., Soman Prem, Di Carli Marcelo F. Clinical Quantification of Myocardial Blood Flow Using PET: Joint Position Paper of the SNMMI Cardiovascular Council and the ASNC. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2017;59(2):273–293. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.201368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown RP, Delp MD, Lindstedt SL, Rhomberg LR, Beliles RP. Physiological parameter values for physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Toxicol Ind Health. 1997;13:407–484. doi: 10.1177/074823379701300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chrysanthou-Baustert I, Polycarpou I, Demetriadou O, et al. Characterization of attenuation and respiratory motion artifacts and their influence on SPECT MP image evaluation using a dynamic phantom assembly with variable cardiac defects. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:698–707. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0378-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fieseler Michael, Kugel Harald, Gigengack Fabian, Kösters Thomas, Büther Florian, Quick Harald H., Faber Cornelius, Jiang Xiaoyi, Schäfers Klaus P. A dynamic thorax phantom for the assessment of cardiac and respiratory motion correction in PET/MRI: A preliminary evaluation. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 2013;702:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2012.09.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leiva-Salinas C, Hom J, Warach S, Wintermark M. Stroke Imaging Research Roadmap. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2012;21:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miles K. A., Lee T.-Y., Goh V., Klotz E., Cuenod C., Bisdas S., Groves A. M., Hayball M. P., Alonzi R., Brunner T. Current status and guidelines for the assessment of tumour vascular support with dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography. European Radiology. 2012;22(7):1430–1441. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patterson Duane L. Modeling and simulation in biomedical engineering: applications in cardiorespiratory physiology [book reviews] IEEE Pulse. 2014;5(1):82–82. doi: 10.1109/MPUL.2013.2289532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sargent RG (2010) Verification and validation of simulation models. Proc 2010 Winter Simul Conf 166–183. 10.1109/WSC.2007.4419595

- 53.Wang K, Ho C, Zhang C, Wang B. A review on the 3D printing of functional structures for medical phantoms and regenerated tissue and organ applications. Engineering. 2017;3:653–662. doi: 10.1016/J.ENG.2017.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood RP, Khobragade P, Ying L et al (2015) Initial testing of a 3D printed perfusion phantom using digital subtraction angiography. Proc SPIE 9417, Medical Imaging 2015: Biomedical Applications in Molecular, Structural, and Functional Imaging, 94170V. 10.1117/12.2081471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.