Abstract

Glaucoma is a chronic, debilitating disease and a leading cause of global blindness. Despite treatment efforts, 10% of patients demonstrate loss of vision. In the US, > 80% of glaucoma cases are classified as open-angle glaucoma (OAG), with primary open-angle (POAG) being the most common. Although there has been tremendous innovation in the surgical treatment of glaucoma as of late, two clinical variants of OAG, normal-tension glaucoma (NTG) and severe POAG, are especially challenging for providers because patients with access to care and excellent treatment options may progress despite achieving a “target” intraocular pressure value. Additionally, recent research has highlighted the importance of nocturnal IOP control in avoiding glaucomatous disease progression. There remains an unmet need for new treatment options that can effectively treat NTG and severe POAG patients, irrespective of baseline IOP, while overcoming adherence limitations of current pharmacotherapies, demonstrating a robust safety profile, and more effectively controlling nocturnal IOP.

Funding The Rapid Service Fees were funded by the corresponding author, Tanner J. Ferguson, MD.

Keywords: Glaucoma treatment, Normal-tension glaucoma, OAG, Open-angle glaucoma, Pharmacotherapy, Surgical treatment of glaucoma

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The current treatment options for open-angle glaucoma are excellent but remain imperfect, and there remains an unmet need for novel treatments, particularly in normal-tension glaucoma. |

| Patients with adequate access to care and treatment still may progress to blindness despite achieving a “target” intraocular pressure. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Current first-line topical treatments do not sufficiently manage IOP throughout the night, a time in which there are meaningful IOP spikes that affect the progression of glaucoma. |

| The current range of available treatments have limitations, and novel treatments aimed at non-invasively and effectively controlling nocturnal IOP will provide a more comprehensive treatment approach. |

Introduction

Glaucoma is a chronic, progressive optic neuropathy, characterized by atrophy of the optic nerve and loss of retinal ganglion cells, resulting in progressive vision loss. Current estimates indicate that glaucoma affects > 80 million people worldwide, including over 3 million Americans [1]. Approximately 10% of glaucoma patients exhibit loss of vision even with treatment, with more than 120,000 cases of blindness attributable to the disease [1]. In terms of national economic impact, glaucoma accounts for over 10 million physician visits annually and is responsible for the majority of the $5.8 billion spent on treatment and management of optic nerve disorders [2].

More than 80% of glaucoma cases in the US—representing over 2.2 million patients in 2012 and projected to increase to over 7.3 million cases by 2050—are classified as open-angle glaucoma (OAG) [3]. In the US, primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form among the various OAG entities, which also may include normal-tension glaucoma (NTG) as a subgroup as well as secondary forms of the disease.

Today, treatment strategies for OAG, both pharmacologic and surgical, are aimed at lowering IOP, the primary modifiable risk factor associated with disease progression. Despite the wealth of available therapies, along with notable innovation in the surgical treatment of glaucoma, two variants of OAG—progressive POAG (despite achieving “target” IOPs) and NTG—continue to challenge clinical IOP reduction efforts. POAG, in its severe form, is characterized by significant visual field loss and increased likelihood of disease progression despite multiple medications, often combined with one or more laser or surgical procedures [4]. NTG, in contrast, is a common form of OAG characterized by the presence of glaucomatous optic nerve damage despite a measured IOP not exceeding 21 mmHg (considered the upper limit of statistically normal IOP). Prevalence studies estimate that approximately one-third of patients with OAG have IOP levels < 21 mmHg [5–7] in the US, with significantly higher prevalence in Asia [8]. NTG represents a particularly challenging subset of glaucoma to manage, as achieving IOP reduction targets is confounded in patients whose pretreatment IOP levels are not above clinically notable thresholds. Furthermore, it has been observed that acrophase of IOP typically occurs at night, and research suggests the nocturnal acrophase pattern of IOP may contribute to the progression of glaucoma [9, 10].

This article aims to provide an update on the current treatment options available for glaucoma, including severe POAG and NTG, and the need for additional treatment options capable of managing nocturnal IOP to mitigate disease progression. The authors’ observations are based on previously conducted and published studies, supplemented by the authors’ clinical and practical experience. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors (Table 1).

Table 1.

A brief comparison of current standard glaucoma therapies with mechanism, use, and adverse effects listed for each option

| Treatment | Mechanism of action | Use | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topical medications (e.g., beta-blockers, prostaglandin analogs, etc.) | Decrease aqueous production, increase uveoscleral outflow | First-line therapy for IOP lowering. Adjunctive treatment | Ocular irritation, preservative toxicity, allergy. Some systemic side effects, e.g. |

| Oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g., acetazolamide) | Decrease aqueous production | Short-term IOP lowering, prevention of postoperative IOP spikes, topical medications not effective | Tingling, GI disturbance, fatigue, allergy, diuresis, metabolic acidosis, metallic taste, potassium depletion |

| Hyperosmotic agents (e.g., mannitol) | Creation of osmotic gradient between blood and ocular fluids | Rapid lowering of IOP | Headache, back pain, seizures, diuresis, pulmonary edema, heart failure, cerebral hemorrhage |

| Laser trabeculoplasty (including argon and selective laser interventions) | Increased trabecular outflow | First line for IOP lowering or adjunctive to medications | Formation of peripheral anterior synechiae, corneal edema, hyphema, IOP spike, iritis, cyclodialysis cleft, Descemet tear |

| Trabecular micro-bypass | Creation of bypass pathway through trabecular meshwork | IOP lowering in patients undergoing cataract surgery who have mild-to-moderate open-angle glaucoma | Stent occlusion/malposition, hyphema, IOP spike, iritis, cyclodialysis cleft, Descemet tear |

| Trabecular ablation | Removal of strip of TM and inner wall of Schlemm canal | IOP lowering in adults or pediatric patients with open-angle glaucoma. Used standalone or with cataract surgery | Incomplete TM removal, wrong site ablation, damage to Schlemm canal, peripheral anterior synechiae, hyphema, IOP spike, iritis, cyclodialysis cleft, Descemet tear |

| Viscodilation of Schlemm’s canal (e.g., ab interno canaloplasty) | Dilation of Schlemm’s canal using a flexible catheter | IOP lowering in adults with open-angle glaucoma | Hyphema, IOP spike, iritis, cyclodialysis cleft, Descemet tear |

| Trabecular removal | TM removal with handheld blade | IOP lowering in open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension, standalone or in combination with cataract surgery | Hyphema, IOP spike, iritis, cyclodialysis cleft, Descemet tear |

| Trabeculotomy by internal approach | TM removal with flexible catheter | IOP lowering in open-angle glaucoma, standalone or in combination with cataract surgery | Hyphema, IOP spike, iritis, cyclodialysis cleft, Descemet tear |

| Cyclophotocoagulation (CPC) | Decrease aqueous production via destruction of ciliary body | Refractory glaucoma, open-angle or closed angle, pain relief due to IOP in blind eye | Pain, iritis, hypotony, phthisis bulbi, fibrin exudates, cystoid macular edema, sympathetic ophthalmia |

| Subconjunctival Stent | Soft implant shunts fluid from anterior chamber to subconjunctival space | Refractory glaucoma, failed previous surgical treatment, patients unresponsive to maximum tolerated medical therapy | Misplaced stent, hypotony, choroidal detachment, exposure of implant, bleb leak, blebitis |

| Glaucoma filtration surgery (e.g., trabeculectomy) | Creation of filtering bleb via sclerostomy | Moderate-to-severe progressive glaucoma, failed prior treatments, progression despite maximally tolerated medical therapy | Hypotony, IOP spike, hyphema, bleb leak, ptosis, hypotony maculopathy, blebitis, endophthalmitis, choroidal effusion, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, serous choroidal detachment |

| Glaucoma drainage devices (implants) | Aqueous humor diversion from anterior chamber to external reservoir | Moderate-to-severe progressive glaucoma, failed prior treatments, progression despite maximally tolerated medical therapy | Hypotony, valve malfunction, hyphema, scleral perforation, tube erosion, endophpthalmitis, corneal decompensation, strabismus, IOP spike, plate migration |

Current Patient Experience

Disease Progression

OAG, of which NTG may be a subgroup, is part of a group of pathologic entities marked by optic neuropathy, which can ultimately lead to permanent vision loss. Although the exact mechanism involved in the pathophysiology of glaucoma is not fully understood, clinical literature reveals that progression of the disease is clearly slowed by reducing the IOP, even in patients with NTG [11, 12]. Physiology of the ocular anatomy and fluid dynamics within the eye are key to understanding the fluctuations in intraocular pressure. Primary fluid drainage occurs through the trabecular meshwork into Schlemm’s canal, continuing into multiple venous channels and finally through the episcleral veins [13]. This pressure-dependent route is often dysfunctional in patients with POAG and NTG and coincides with increasing IOP and subsequent retinal ganglion cell axon damage as well as cupping of the optic nerve head [13, 14]. Given the link between IOP and these indicia of glaucomatous disease progression, it is notable that occurrences of increased IOP are concentrated during nighttime hours [10, 15].

Systemic nocturnal hypotension is another component to consider in the pathophysiology of glaucoma and a factor that may exacerbate the impact of nocturnal increases in IOP. The fall of blood pressure at night has long been established [16]. The relationship of blood pressure and intraocular pressure is described in terms of ocular perfusion pressure (OPP). In particular, diastolic OPP can be calculated as the difference between diastolic blood pressure and IOP. Alterations in diastolic OPP may therefore cause poor perfusion or even ischemia. Thus, reductions in blood pressure at night combined with the established increase in IOP could pose a meaningful risk to glaucomatous eyes.

In both POAG and NTG, significant retinal ganglion cell death occurs prior to the appearance of visual field abnormalities and long before patients perceive any functional vision loss [17]. In advance of visual acuity or visual field deficits, however, the magnitude of retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) damage can be quantified using optical coherence tomography (OCT). The extent of damage to the RNFL correlates with visual function and manifests as visual field depression on perimetric testing [18, 19]. Accurately and reliably tracking visual field loss or RNFL loss over time through repeat testing is the only acceptable method of monitoring glaucoma progression. Unfortunately, glaucoma evaluations, especially visual field testing, are time consuming and arduous for providers and patients, with repeated measurements required to accurately assess declining visual function [20, 21].

Treatment Options

To date, the only approved treatments for POAG are IOP-lowering pharmacotherapies, surgeries, or a combination thereof [22, 23]. Despite the emergence of new surgical and medical options, current therapies remain imperfect, and novel treatment options are desired. Although lowering IOP is the primary goal of all OAG therapies (along with delaying the accompanying visual field declines), currently a subset of NTG patients exists whose IOP is not sufficiently reduced with available therapies, resulting in a differentially vulnerable patient population.

As a first-line therapy, physicians most frequently prescribe topical ophthalmic drops. Currently prescribed classes of topical medications include alpha-adrenergic agonists (e.g., brimonidine tartrate), beta-blockers (e.g., timolol and betaxolol), carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g., brinzolamide and dorzolamide), prostaglandins (e.g., latanoprost, bimatoprost, and travoprost), and first-in-class therapies (e.g., lanoprostene bunod and netarsudil) [24–26]. Comparatively, pharmacotherapies are favored as the initial intervention because of their clinical efficacy and less severe risk profiles relative to surgery.

Approved pharmacotherapies target IOP reduction by reducing aqueous humor production, increasing aqueous humor outflow, or a combination of these two mechanisms. While pharmacotherapy offers the least invasive form of glaucoma management, patients may still experience adverse events that can reduce quality of life or compromise health outcomes [27]. Known glaucoma pharmacotherapy adverse events include, but are not limited to, ocular surface disease, hyperemia, bronchospasm, dysrhythmia, and rarely death [27–29]. Regrettably, these adverse events occur in a large percentage of treated cases, with symptoms such as irritation reported in up to 40% of medicated patients [30].

While these topical medications have some benefit, individual trials and meta-analyses of clinical studies suggest that glaucoma drug efficacy is highest during waking hours, with limited or no IOP control across nocturnal hours [31]. Additionally, given the chronic, progressive course of the disease, patients typically sustain daily pharmacotherapy treatment for life, with treatment intensity increasing based on progression of disease. Concurrently, escalating utilization requirements make drug prices a key economic barrier to treatment adherence. In a survey of patients at two US-based glaucoma clinics, 40% of non-adherent patients cited drug costs as a barrier to compliance [32]. These same patients also cited forgetfulness, difficulty with self-administration, and skepticism about glaucoma’s blinding effects as barriers to pharmacotherapy adherence. Medication non-adherence is a widespread issue in this patient population, even with intensive education, exposing patients to increased risk of disease progression and future healthcare resource use [33]. Pharmacoepidemiology reveals that noncompliance to pharmacotherapy among POAG patients—reported at rates exceeding 60%—is as high or higher than those observed with other chronic medications and are further exacerbated by a variety of medical, psychologic, and social factors [33–35].

Patients unable or unlikely to achieve IOP control using pharmacotherapies often transition to more interventional treatments, including laser. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) is the least invasive surgery and the most frequently performed laser surgery procedure for treating POAG, employing low-energy laser beams to microscopically modify the trabecular meshwork™ and improve aqueous drainage [20]. In addition to avoiding adherence and cost issues associated with daily pharmacotherapy, research suggests that patients who initiate treatment with laser procedures show improved IOP lowering [36–38]. Data indicate, however, that laser procedures targeting the TM have limited duration and repeatability, particularly with ALT (argon laser trabeculoplasty), as SLT can be repeated. Regrettably, it is also not as effective in NTG patients, with up to 13% of patients requiring subsequent surgical reintervention in published trials [36, 39].

The efficacy of laser treatment for glaucoma is known to diminish over time, with anywhere between one-fifth and one-third of patients requiring at least one additional glaucoma medication in the 12 months following laser treatment [39–41]. One-, 3-, and 5-year success rates with the procedure are estimated to be around 62%, 50%, and, 32%, respectively, showing a decrease in response rate over time [37].

For the patients with progressive disease despite laser surgery and/or pharmacotherapy, traditional surgical treatment may be required. The most common of these options is trabeculectomy, a procedure to allow an alternate aqueous fluid drainage pathway into a designated space under the conjunctiva (called a bleb), from which it is released into the circulatory system. Of the treatment options currently available, trabeculectomy has been demonstrated to be the most durable surgical intervention intended to lower long-term IOP [42]. However, as the most invasive form of glaucoma treatment, trabeculectomy is linked to the greatest incidence of adverse events, both minor and serious. Large randomized trials suggest that 37–50% of patients who undergo trabeculectomy experience events such as persistent hypotony or loss of vision, resulting in surgical failure [43, 44]. Tube shunts demonstrate a comparable efficacy and risk profile [45].

The past decade has seen the development of micro-invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) as options offering a safer means of IOP reduction relative to trabeculectomy [46]. Almost all MIGS procedures avoid disruption of the sclera and/or conjunctiva, along with major complications related to trabeculectomy and the formation of a filtering bleb. MIGS procedures primarily target four approaches to IOP reduction, including increased trabecular outflow, increased uveoscleral outflow, increased subconjunctival outflow, and decreased aqueous production. MIGS procedures carry a superior safety profile compared with traditional surgery but are less effective at lowering IOP and reducing medication burden [47–49]. In addition, while MIGS offer a safer alternative to surgery for patients with mild-to-moderate disease who are intolerant to pharmacotherapy, such procedures still have attendant risks of adverse events such as infection and hypotony, often necessitating additional device-related interventions or surgery [50, 51]. Studies also demonstrate that MIGS procedures are more effective in patients with higher baseline IOP. Accordingly, patients with lower baseline IOP, as in normal-tension glaucoma, are predisposed to smaller IOP reductions following MIGS procedures, with these results potentially insufficient to mitigate disease progression [52, 53].

Although many therapeutic options for OAG exist, even patients with access to excellent care and cutting-edge treatments still progress to blindness. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that patients with apparently well-controlled IOP exhibit glaucomatous disease progression, primarily due to the unpredictability of treatment outcomes [54]. An ideal therapy would provide safe, non-invasive, and effective IOP lowering for all baseline IOP levels, work effectively overnight (when IOP spikes occur), and provide a favorable adherence profile.

Clinical Considerations for Normal Tension and Severe Glaucoma

Because the importance of IOP in the development and progression of glaucoma is well established, pressure-lowering therapies remain the foundation of treatment options. However, IOP is not a static process. Rather, it fluctuates throughout the day in a circadian rhythm. As a result, relying on diurnal (during the day) office measurements of IOP to dictate treatment decisions fails to account for a patient’s complete clinical profile. Several studies have investigated 24-h IOP patterns with important results informing optimal glaucoma management.

Mosaed et al. examined 24-h IOP data for young healthy, older healthy, and untreated older glaucoma populations, measuring IOP every 2 h with a pneumatonometer [55]. The investigators identified a nocturnal increase in IOP in all three populations, even when participants were kept in the supine position for the 24-h period. This same study identified that this nocturnal spike was further exaggerated when patients were permitted to keep the habitual position (upright/seated during the day, supine at night). These results were consistent with previous studies reporting the effects of aging and position on IOP over 24 h [56]. Specifically, Mansouri et al. also reported that posture has a significant effect, with an approximate 5 mmHg increase in IOP in supine position regardless of age; notably, even when controlling for supine positioning, an approximate nocturnal increase of 3 mmHg in IOP was observed [57].

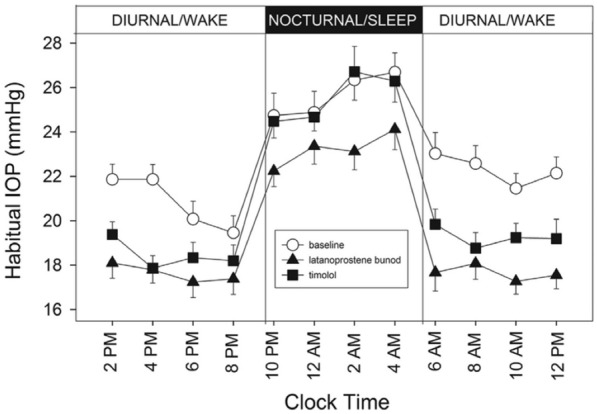

These observed changes demonstrate that, especially for those with glaucoma, peak IOP, or acrophase, occurs nocturnally. Figure 1 shows this pattern. A study by Liu et al. comparing the IOP-lowering ability over 24 h of two glaucoma medications in patients with open-angle glaucoma also demonstrated that peak IOP measurements occurred at night [58]. Numerous additional studies have identified the same phenomenon in both normal and glaucomatous patients [59, 60]. However, a prior study by Renard et al. studying the 24-h pattern of IOP in eyes with NTG demonstrated both a nocturnal and diurnal acrophase. Additional studies [61, 62] have reported both patterns in normal-tension glaucoma, highlighting the phenotypic variance between eyes with NTG and POAG and the need for individualized, targeted treatment approaches. Moreover, findings that the diurnal IOP profile is not predictive of nocturnal acrophase in POAG or NTG further emphasize the importance of 24-h IOP reduction as a critical component of optimal glaucoma management approach.

Fig. 1.

Nocturnal IOP acrophase, as measured in patients with ocular hypertension or early POAG (n = 21); from Liu et al. [52] (reprinted under Creative Commons license)

While these patterns are compelling, their relevance to glaucoma management and a current unmet clinical management need becomes clearer when looking at their impact on disease progression. De Moraes et al. monitored IOP over 24 h and confirmed the previously established pattern of peak IOP at night but also found that the mean peak ratio and fluctuation were the best predictors of visual field change and fast progression [10]. An additional study by Tojo et al. further showed that the range of IOP fluctuations was larger at night in eyes with NTG, despite there being no significant difference in mean IOP between the two groups [63]. These studies confirm that nocturnal IOP variance, and corresponding control, plays a critical role in patients’ glaucoma outcomes, a finding that has been further supported in analyses of IOP variability recorded in large population trials, including the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS) and the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS) [64].

As previously mentioned, other factors such as OPP may have a meaningful role in the pathogenesis of glaucoma and contribute to disease progression. The impact of ocular perfusion, particularly at night, on glaucoma progression has been a topic of keen interest in the field and may be particularly important in patients with low-normal IOP. Numerous population-based studies have provided evidence establishing an association between low OPP and disease progression. Numerous population-based studies have provided evidence establishing an association between low OPP and disease progression [65, 66]. Kwon et al., utilizing 24-h IOP and ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring in the habitual position in NTG patients, found that “over dippers” (those with ≥ 20% nocturnal BP reduction) had the highest rate of visual field progression as well as significantly greater frequency of optic disc hemorrhage [67]. Additionally, these studies reported that this vulnerable (“over dipper”) patient population had significantly greater mean ocular perfusion pressure variability, correlating to glaucomatous visual field progression. This association between perfusion pressure and glaucoma is reinforced by other recent publications reporting a nearly 5 × greater chance of glaucoma development in patients with low diastolic perfusion pressure and demonstrating associations between lower mean ocular perfusion pressure and increased risk of glaucoma progression [68, 69]. In addition, a follow-up study by Kwon et al. also postulated that the decrease in nocturnal blood pressure—specifically observable dips in diastolic BP—is a key independent risk factor for progressive visual field loss in glaucoma [70]. Unsurprisingly, blood pressure decrease at night may be augmented by oral anti-hypertensive therapies, whose administration has also been connected with progressive visual field deterioration [71]. The association of low perfusion pressure and glaucoma progression further highlights the importance of controlling nocturnal IOP at night when POAG and NTG patients may be most susceptible to glaucomatous damage [72]. Although the association of OPP and OAG progression has been demonstrated by meaningful studies, new randomized trials aimed at identifying modifiable systemic risk factors would be valuable for further understanding of the pathophysiology of glaucoma.

In addition to aggregated clinical evidence linking nocturnal variability in the aforementioned physiologic factors to glaucoma progression, recent work also connects disordered sleep states to glaucoma. Boland and colleagues evaluated National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey sleep data from 6784 American adults and concluded that respondents reporting disordered sleep—including sleep durations ≤ 3 h or ≥ 10 h per night—had a three-fold increased risk of disc defined glaucoma or visual field deficits [73]. This finding further complements the premise of increased vulnerability during overnight periods and the corresponding need for novel treatment options capable of effectively controlling nocturnal IOP.

Despite the growing body of evidence indicating that nocturnal increases in IOP play a significant role in glaucoma and its progression, it appears that current therapies do not sufficiently manage IOP throughout the night. Prior studies have demonstrated that commonly prescribed glaucoma pharmacotherapies such as beta-blockers (e.g., timolol) and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g., dorzolamide) do not provide adequate control of nocturnal IOP [74]. Work by Liu et al. investigated the nocturnal effects of timolol or latanoprost compared with no treatment in glaucoma patients and found that, though both drugs were effective at lowering IOP during the daytime period, timolol did not reduce IOP at night compared with no medication. Furthermore, both the latanoprost and timolol groups still demonstrated a nocturnal IOP peak, indicating reduced nighttime efficacy [75]. Similarly, Liu separately found that when either timolol or brinzolamide was added to patients already on latanoprost monotherapy, the timolol group did not show a reduction in nocturnal IOP [76]. While the brinzolamide add-on did show some IOP-lowering at night compared with latanoprost alone, it was < 2 mmHg and the nocturnal peak exacerbated by supine position at night persisted. Liu also showed that brimonidine monotherapy did not lower IOP during the nocturnal period [77]. In addition to being less efficacious at night, beta-blocker drops have been associated with a significantly greater percentage drop in nocturnal diastolic blood pressure and increased glaucoma progression in patients with normal-tension glaucoma [78]. The recently approved novel latanoprostene bunod demonstrated superior nocturnal IOP-lowering effects compared with timolol but it remains unclear whether the IOP reduction is clinically significant [58].

While 24-h IOP monitoring is a relatively new emergence in the research of glaucoma, the existing body of literature indicates that there are meaningful increases in IOP occurring at night that affect the progression of glaucoma and are not sufficiently being treated using current options.

Conclusions

Despite best efforts from researchers and clinicians, patients with NTG and severe POAG often face progressive, permanent vision loss. The current range of available glaucoma treatments has established limitations. Topical medications are associated with adverse effects including potential ocular surface disease, hyperemia, and poor patient adherence. Filtering procedures such as trabeculectomy have increased risk of complications and vision loss, and long-term studies reveal that one-third to one-half of patients may not exhibit IOP control after 5 years [79, 80]. Conversely, recent advances in MIGS procedures show promise for controlling IOP in certain patients with POAG, but have limited effectiveness in lowering IOP for patients presenting with lower baseline IOP [81, 82]. Furthermore, these therapies are not currently approved to treat severe glaucoma.

Diurnal IOP variation has been well established. Recent studies have elucidated the importance of nocturnal IOP elevation and risk of progression. At night IOP increases, ocular perfusion decreases, and topical medications have less efficacy. An unmet need exists for independent or adjunctive interventions that effectively and safely reduce nocturnal IOP, as this control appears crucial to preventing progressive vision loss in both severe POAG and NTG patients. Additionally, a need exists for treatments that can effectively lower IOP in patients with NTG, especially given the potential for disease progression. The next iteration in viable therapies for POAG and NTG lies in demonstrably effective, safe, and minimally or non-invasive interventions focused on nocturnal IOP control. These new treatment options will complement existing standards of care to provide a more comprehensive approach in preventing glaucoma-related blindness.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study has no formal funding or sponsorship. The Rapid Service Fees were funded by Tanner J. Ferguson, MD, the corresponding author.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Dr. Arsham Sheybani is a consultant for Allergan. Dr. Thomas Samuelson is a consultant for Ivantis, Alcon Surgical, MicroOptix, Santen, and Allergan. Dr. Malik Kahook is a consultant for Allergan, Alcon, and New World Medical. Dr. Ike Ahmed is a consultant for the following: Aquues, Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Alcon, Allergan, ArcSCan, Bausch & Lomb, Beaver Visitec, Camras Vision, Carl Zeiss Meditec, CorNeat Vision, Ellex, Elutimed, Equinox, Genentech, Glaukos, Gore, Iantech, InjectSense, Iridex, iStar Medical, Ivantis, Johnson & Johnson Vision, KeloTec, Layer Bio, Leica Microsystem, MicroOptx, New World Medical, Omega Ophthalmics, Polyactivia, Sanoculis, Santen, Science Based Health, Sight Sciences, Stroma, True Vision, Vizzario, Akorn, Beyeonics, ELT Sight, MST Surgical, Ocular Instruments, Ocular Therapeutics, and Vialase. Dr. Tanner J. Ferguson is a consultant for Glaukos, Equinox. Drs. Daniel Bettis, Rachel Scott, Delaney Kent, J. David Stephens, and Leon Herndon have no relevant financial disclosures.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.10075304.

Change history

12/22/2021

The license text was incorrectly structured. The article has been corrected.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittenborn JS, Zhang X, Feagan CW, et al. The economic burden of vision loss and eye disorders among the United States population younger than 40 years. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(9):1728–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vajaranant TS, Wu S, Torres M, Varma R. The changing face of primary open-angle glaucoma in the United States: demographic and geographic changes from 2011 to 2050. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(2):303–314.e303. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao HL, Kumar AU, Babu JG, Senthil S, Garudadri CS. Relationship between severity of visual field loss at presentation and rate of visual field progression in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(2):249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, et al. Relationship between intraocular pressure and primary open angle glaucoma among white and black Americans. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(8):1090–1095. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080080050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dielemans I, Vingerling JR, Wolfs RC, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, de Jong PT. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in a population-based study in The Netherlands. The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(11):1851–1855. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo K, Healey PR. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(10):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KE, Park KH. Update on the prevalence, etiology, diagnosis, and monitoring of normal-tension glaucoma. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2016;5(1):23–31. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agnifili L, Mastropasqua R, Frezzotti P, et al. Circadian intraocular pressure patterns in healthy subjects, primary open angle and normal tension glaucoma patients with a contact lens sensor. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(1):e14–e21. doi: 10.1111/aos.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Moraes CG, Jasien JV, Simon-Zoula S, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Visual field change and 24-hour IOP-related profile with a contact lens sensor in treated glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(4):744–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obstbaum SA, Cioffi GA, Krieglstein GK, et al. Gold standard medical therapy for glaucoma: defining the criteria identifying measures for an evidence-based analysis. Clin Ther. 2004;26(12):2102–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.clintera.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boland MV, Ervin A-M, Friedman DS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of treatments for open-angle glaucoma: a systematic review for the US preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):271–279. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu M, Lin C, Weinreb RN, Lai G, Chiu V, Leung CKS. Risk of visual field progression in glaucoma patients with progressive retinal nerve fiber layer thinning: a 5-year prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH, Alward WLM. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1113–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon Y, Lee JY, Jeong DW, Kim S, Han S, Kook MS. Relationship between nocturnal intraocular pressure elevation and diurnal intraocular pressure level in normal-tension glaucoma patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(9):5271–5279. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staessen JA, Bieniaszewski L, O’Brien E. Nocturnal blood pressure fall on ambulatory monitoring in a large international database. The “Ad Hoc’ Working Group. Hypertension. 1997;29(1 Pt 1):30–39. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.29.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Öhnell H, Heijl A, Brenner L, Anderson H, Bengtsson B. Structural and functional progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1173–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leske MC, Hyman L, Hussein M, Heijl A, Bengtsson B. Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. The effectiveness of intraocular pressure reduction in the treatment of normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(5):625–626. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, Levin LA. Detection and measurement of clinically meaningful visual field progression in clinical trials for glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;56:107–147. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Öhnell H, Heijl A, Anderson H, Bengtsson B. Detection of glaucoma progression by perimetry and optic disc photography at different stages of the disease: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(3):281–287. doi: 10.1111/aos.13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7 The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conlon R, Saheb H, Ahmed IIK. Glaucoma treatment trends: a review. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52(1):114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1901–1911. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonas JB, Aung T, Bourne RR, Bron AM, Ritch R, Panda-Jonas S. Glaucoma. Lancet. 2017;390(10108):2183–2193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue K. Managing adverse effects of glaucoma medications. Clin Ophthalmol (Auckland, NZ). 2014;8:903–913. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S44708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahook MY, Serle JB, Mah FS, et al. Long-term safety and ocular hypotensive efficacy evaluation of netarsudil ophthalmic solution: rho kinase elevated IOP treatment trial (ROCKET-2) Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;200:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanner E, Tsai JC. Glaucoma medications: use and safety in the elderly population. Drugs Aging. 2006;23(4):321–332. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuman JS. Short- and long-term safety of glaucoma drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2002;1(2):181–194. doi: 10.1517/14740338.1.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pisella PJ, Pouliquen P, Baudouin C. Prevalence of ocular symptoms and signs with preserved and preservative free glaucoma medication. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(4):418–423. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman-Casey PA, Robin AL, Blachley T, et al. The most common barriers to glaucoma medication adherence: a cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(7):1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart WC, Konstas AGP, Nelson LA, Kruft B. Meta-analysis of 24-hour intraocular pressure studies evaluating the efficacy of glaucoma medicines. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1117–1122.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiscella R, Caplan E, Kamble P, Bunniran S, Uribe C, Chandwani H. The effect of an educational intervention on adherence to intraocular pressure-lowering medications in a large cohort of older adults with glaucoma. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(12):1284–1294. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2018.17465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai JC. A comprehensive perspective on patient adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11 Suppl):S30–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz GF, Quigley HA. Adherence and persistence with glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53 Suppl1(6):S57–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crawley L, Zamir SM, Cordeiro MF, Guo L. Clinical options for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure. Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2012;4:43–64. doi: 10.4137/OED.S4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel V, El Hawy E, Waisbourd M, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients initially responsive to selective laser trabeculoplasty. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015;8(5):960–964. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2015.05.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1505–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32213-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garg A, Vickerstaff V, Nathwani N, et al. Primary selective laser trabeculoplasty for open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension: clinical outcomes, predictors of success, and safety from the laser in glaucoma and ocular hypertension trial. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(9):1238–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bettis DI, Whitehead JJ, Farhi P, Zabriskie NA. Intraocular pressure spike and corneal decompensation following selective laser trabeculoplasty in patients with exfoliation glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(4):e433–e437. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutnik C, Crichton A, Ford B, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus argon laser trabeculoplasty in glaucoma patients treated previously with 360 selective laser trabeculoplasty: a randomized, single-blind. Equivalence Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(2):223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rulli E, Biagioli E, Riva I, et al. Efficacy and safety of trabeculectomy vs nonpenetrating surgical procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(12):1573–1582. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, et al. Treatment outcomes in the tube versus trabeculectomy (TVT) study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):789–803.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayyala RS, Chaudhry AL, Okogbaa CB, Zurakowski D. Comparison of surgical outcomes between canaloplasty and trabeculectomy at 12 months’ follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2427–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gedde SJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, et al. Postoperative complications in the tube versus trabeculectomy (TVT) study during five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):804–814.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen J, Gedde SJ. New developments in tube shunt surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30(2):125–131. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saheb H, Ahmed I. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery: current perspectives and future directions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Francis BA, Singh K, Lin SC, et al. Novel glaucoma procedures: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(7):1466–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shah M, Law G, Ahmed IIK. Glaucoma and cataract surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27(1):51–57. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah M. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery—an interventional glaucoma revolution. Eye Vis (Lond). 2019;6(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s40662-019-0154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lavia C, Dallorto L, Maule M, Ceccarelli M, Fea AM. Minimally-invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) for open angle glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agrawal P, Bradshaw SE. Systematic literature review of clinical and economic outcomes of micro-invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) in primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmol Ther. 2018;7(1):49–73. doi: 10.1007/s40123-018-0131-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown RH, Gibson Z, Le Z, Lynch MG. Intraocular pressure reduction after cataract surgery with implantation of a trabecular microbypass device. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(6):1318–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferguson TJ, Berdahl JP, Schweitzer JA, Sudhagoni RG. Clinical evaluation of a trabecular microbypass stent with phacoemulsification in patients with open-angle glaucoma and cataract. Clin Ophthalmol (Auckland, NZ). 2016;10:1767–1773. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S114306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(4):487–497. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(98)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mosaed S, Liu JHK, Weinreb RN. Correlation between office and peak nocturnal intraocular pressures in healthy subjects and glaucoma patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(2):320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jorge J, Ramoa-Marques R, Lourenço A, et al. IOP variations in the sitting and supine positions. J Glaucoma. 2010;19(9):609–612. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181ca7ca5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu JHK, Mansouri K, Weinreb RN. Estimation of 24-hour intraocular pressure peak timing and variation using a contact lens sensor. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu JHK, Slight JR, Vittitow JL, Scassellati Sforzolini B, Weinreb RN. Efficacy of latanoprostene bunod 0.024% compared with timolol 0.5% in lowering intraocular pressure over 24 hours. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;169:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee AC, Mosaed S, Weinreb RN, Kripke DF, Liu JHK. Effect of laser trabeculoplasty on nocturnal intraocular pressure in medically treated glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(4):666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hara T, Hara T, Tsuru T. Increase of peak intraocular pressure during sleep in reproduced diurnal changes by posture. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(2):165–168. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okada K, Tsumamoto Y, Yamasaki M, Takamatsu M, Mishima HK. The negative correlation between age and intraocular pressures measured nyctohemerally in elderly normal-tension glaucoma patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241(1):19–23. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Costagliola C, Parmeggiani F, Virgili G, et al. Circadian changes of intraocular pressure and ocular perfusion pressure after timolol or latanoprost in Caucasians with normal-tension glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246(3):389–396. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0704-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tojo N, Abe S, Ishida M, Yagou T, Hayashi A. The fluctuation of intraocular pressure measured by a contact lens sensor in normal-tension glaucoma patients and nonglaucoma subjects. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(3):195–200. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heijl A, Bengtsson B, Chauhan BC, et al. A comparison of visual field progression criteria of 3 major glaucoma trials in early manifest glaucoma trial patients. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(9):1557–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leske MC, Wu S-Y, Hennis A, Honkanen R, Nemesure B, BESs Study Group Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hulsman CAA, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, Witteman JCM, de Jong PTVM. Blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and open-angle glaucoma: the Rotterdam study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(6):805–812. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwon J, Lee J, Choi J, Jeong D, Kook MS. Association between nocturnal blood pressure dips and optic disc hemorrhage in patients with normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;176:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Müskens RPHM, de Voogd S, Wolfs RCW, et al. Systemic antihypertensive medication and incident open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2221–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, Greenfield DS, et al. Risk factors for visual field progression in the low-pressure glaucoma treatment study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(4):702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kwon J, Jo YH, Jeong D, Shon K, Kook MS. Baseline systolic versus diastolic blood pressure dip and subsequent visual field progression in normal-tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(7):967–979. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB, Podhajsky P, Alward WL. Nocturnal arterial hypotension and its role in optic nerve head and ocular ischemic disorders. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117(5):603–624. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, Bernardi P, Morbio R, Varotto A. Vascular risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma: the Egna-Neumarkt Study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(7):1287–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qiu M, Ramulu PY, Boland MV. Association between sleep parameters and glaucoma in the United States population: national health and nutrition examination survey. J Glaucoma. 2019;28(2):97–104. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Orzalesi N, Rossetti L, Invernizzi T, Bottoli A, Autelitano A. Effect of timolol, latanoprost, and dorzolamide on circadian IOP in glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(9):2566–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu JHK, Kripke DF, Weinreb RN. Comparison of the nocturnal effects of once-daily timolol and latanoprost on intraocular pressure. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(3):389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu JHK, Medeiros FA, Slight JR, Weinreb RN. Comparing diurnal and nocturnal effects of brinzolamide and timolol on intraocular pressure in patients receiving latanoprost monotherapy. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu JHK, Medeiros FA, Slight JR, Weinreb RN. Diurnal and nocturnal effects of brimonidine monotherapy on intraocular pressure. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(11):2075–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky P, Zimmerman MB. Beta-blocker eyedrops and nocturnal arterial hypotension. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(3):301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nouri-Mahdavi K, Brigatti L, Weitzman M, Caprioli J. Outcomes of trabeculectomy for primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(12):1760–1769. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30796-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, et al. Three-year follow-up of the tube versus trabeculectomy study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5):670–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guedes RAP, Gravina DM, Lake JC, Guedes VMP, Chaoubah A. Intermediate results of istent or istent inject implantation combined with cataract surgery in a real-world setting: a longitudinal retrospective study. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(1):87–100. doi: 10.1007/s40123-019-0166-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ferguson TJ, Ibach M, Schweitzer J, et al. Trabecular microbypass stent implantation in pseudophakic eyes with open-angle glaucoma: long-term results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.