Abstract

Phytomelatonin-rich (194.02 ± 2.45–205.80 ± 1.67 ng/g of dry mustard seeds) and erucic acid-lean (below 2%) extracts from an oilseed crop, (yellow and black mustard seeds) have been successfully obtained by ultrasonication-assisted-extraction in ethanol–water. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and liquid chromatography-mass spectrum analyses have confirmed the presence of phytomelatonin along with tocopherol, ascorbic acid, limonene and linalool in the extract. Field emission scanning electron micrographs confirmed the cavitational effects of sonication on mustard seed matrices. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy established the strong antioxidant activities (72.25–75.49%) of the extracts foregoing erroneous spectrophotometric result of pan assay interference compounds. A synergistic effect value of 1.13 (greater than unity) confirmed synergistic co-existence of the antioxidants in the extract. This study interestingly revealed that an antioxidant synergy could be obtained by classical reductionism. Acute oral toxicity of the extracts were found to be greater than 5000 mg/kg body weight of rats. The extracts are perfectly safe to be utilized as antioxidative food supplements.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-019-04161-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mustard seeds, Ultrasonication, CCRD, High melatonin low erucic acid, Antioxidant synergy

Introduction

Melatonin (5-methoxy-N-acetyltryptamine), the sleep hormone, performs a myriad of biochemical functions such as controls circadian rhythms, immuno-responsiveness, and sleep–wake process, to name a few (Bhattacharjee et al. 2016). This biotherapeutic molecule is also valued for its strong antioxidant activity (Arnao 2014) and possesses significant anti-cancer (Li et al. 2017), hypoglycaemic and hypercholesterolemic properties (Bhattacharjee and Ghosh 2016). In view of the strikingly beneficial effects of melatonin, this molecule has been chemically synthesised by Lerner et al. (1958) for formulation of commercial over the counter (OTC) drugs of melatonin, which are commonly used for treatment of sleeping disorders or jet lag. Besides, melatonin is also recommended for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease), heart disease and metabolic disorders (Feng et al. 2014).

However, its usage as a drug possesses restrictions on precise dose regulation, owing to its toxicity and side effects (Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz 2018a, b). Davies et al. (2005) reported that long-term (1 year) administration of melatonin drug (regularly at a dose of 75 mg/day) resulted in neurosensory and gastrointestinal disorders in normal healthy women. These side effects of synthetic melatonin have been attributed to limitations in process of purification of the same, since certain harmful chemical compounds (Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz 2018a), such as formaldehyde-melatonin, hydroxymelatonin isomer produced during chemical synthesis of melatonin are inseparable from the same. Therefore, usage of phytomelatonin (MT) as an alternative to synthetic melatonin in formulation of food or dietary supplements is the need of the day (Arnao 2014; Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz 2018b).

MT in the oilseeds has been widely reported in mustard seeds (129–660 ng/g of seeds, d.w.b) (Manchester et al. 2000; Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee 2017), almonds (39 ng/g seed, d.w.b), and sunflower seeds (29 ng/g seed, d.w.b), to name a few (Meng et al. 2017). It has been found that mustard seeds are the richest source of phytomelatonin among the other oilseeds. Oral administration of walnut (Reiter et al. 2005) and cherry-based nutraceutical beverage (rich sources of phytomelatonin) (Delgado et al. 2012) have reportedly enhanced plasma MT levels in the normal healthy rats and ringdoves and also raised their total antioxidant capacities in blood. However, there is only one report of Chakraborty et al. (2019), who have documented hypocholesterolemic efficacy of phytomelatonin in yellow mustard seed extract (at a dose of 550 mg/k.g./b.w for 21 days) in Wister albino rats. It is opined that mustard seeds being the richest source of phytomelatonin among the oilseeds could be used as an alternative of synthetic melatonin for formulation of phytomelatonin-rich food and therapeutic supplements.

According to Messina et al. (2001), ‘reductionism’ and ‘holism’ are two approaches, where ‘reductionism’ defines isolation of single molecule from the complex food matrix and ‘holism’ (or ‘food synergy’) refers to the consumption of whole food. Consumption of whole mustard seeds as a source of MT is impeded owing to their high erucic acid content (30–60%) which leads to occurrence of heart diseases (FSANZ 2003). Moreover, oral administration of the same is also restricted due to high Scoville heat unit (SHU) of 30,000 (unpublished data), which renders strong pungency to even cooked foods. Therefore it is necessary to extract MT from the mustard seeds for its effective utilization as a biotherapeutic.

According to Bission et al. (2016), parts of a plant as well as the extraction method play important roles in obtaining a therapeutically rich extract. Thus, choice of the extraction method is extremely important which would allow selective extraction of the bioactive principle. The ‘seeds’ being the richest source of MT in the mustard plant was therefore subjected to green extraction (using ethanol–water as solvent system) i.e., ‘reductionism’ (Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee 2017) to obtain an phytomelatonin-rich extract safe for end use as a food supplement. Since ultrasonication-assisted extraction (UAE) is a widely used extraction technology and has proved to be beneficial for selective extraction of biomolecules from plant matrices, this technology has been employed in our study to extract MT from mustard seeds. The UAE process parameters were optimized using central composite rotatable design (CCRD) and the effect of each parameter on the yields of MT has been studied using response surface methodology (RSM). The effects of sonication on the yield of MT have been investigated by field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) analysis.

Mustard seeds are also rich sources of several other antioxidants (namely, lutein, tocopherol, ascorbic acid, squalene, limonene and linalool to name a few) (USDA 2018) (Miyazawa and Kawata 2006). It is envisaged that high sonication energy would disrupt the oil glands in mustard seeds and the above compounds would be co-extracted with MT. These co-extracted antioxidants may impede the antioxidative function of MT, if they do not act in synergism. Moreover, Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI 2017) warns on high levels (more than 2%) of erucic acid and a no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) of 500 mg erucic acid/day has been recommended by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ 2003).

Therefore chemical profiling of the UAE extracts (obtained at optimized conditions of UAE) have been conducted using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), gas chromatography (GC) and liquid-chromatography electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry (LC–ESI–MS) analyses to identify the antioxidants extracted and erucic acid. The in vitro antioxidative interactions (antagonism or synergism) among the co-extracted antioxidants have been evaluated in terms of synergism effect (SE). This study endeavours to test the following hypotheses: (a) whether a ‘phytomelatonin-rich, erucic acid-lean’ extract could be obtained from mustard seeds through ‘reductionism’ (using UAE) and (b) whether the interactions among the co-extracted antioxidants with MT were synergistic or antagonistic to permit safe end-use of the extract as a food supplement.

Materials and methods

Materials

Two different species of mustard seeds, namely brown mustard (BM) and yellow mustard (YM) seeds have been selected for this study since they are known to have low erucic acid contents. Fresh authenticated ‘Sarama’ variety of BM (Brassica juncea) seeds and ‘B9’ variety of YM (Brassica campestris) seeds were procured from the faculty center of ‘Integrated Rural Development and Management’, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University, Narendrapur, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Details of chemicals required for this study are provided in file S1.

Proximate analysis of raw materials

Proximate analysis has been conducted to analyse the effects of the proximate constituents on the yields of MT obtained by UAE. Whole seeds of YM and BM were ground by an electric grinder (HL 1618, M/s Philips, India) and the mean particle diameter (dp) was determined using the sieve analysis method by screening the mustard powder through a set of standard sieves (24, 28, 32, 35, 48, 60 and 65 Tyler meshes) in a sieve shaker (AS 200, M/s Retsch, Haan, Germany) in accordance with the method reported by Altuntas et al. (2005).

According to Setyaningsih et al. (2016), the amount of MT in any food matrix is directly proportional to its protein content. Therefore protein content in the above seeds was determined using standard AOAC (Kjeldahl) method (2006). The above seeds were also subjected to proximate analysis using standard American Spice Trade association (ASTA) Methods (1997) for moisture, ash, crude fat, crude fibre and total carbohydrate (by difference) contents.

Optimization of UAE conditions for obtaining phytomelatonin-rich extracts from BM and YM seeds

In UAE, the extraction process parameters such as batch size and sonication mode (continuous or by setting pulse duration) have been fixed through several preliminary trials. A batch size of minimum 5 g of ground mustard powder was required to allow reliable quantification of MT therein. Increase of batch size above 5 g had no effect on the yield of MT in the UAE extract. The preliminary trials also suggested the use of continuous mode of UAE for extraction of MT from mustard seeds, since setting different pulse duration (paused time) did not enhance yield of MT.

5 g mustard seed powder (in batches of different mean dp) and varying ratios of sample weight to solvent (ethanol:water::1:1, v/v) volume (Table S1) were homogenized in a 250 ml amber colored glass beaker using a homogenizer (T 50 digital Ultra-turrax®, M/s Ika, Staufen, Germany) at 500 rpm for 5 min and then subjected to UAE. In our study, probe sonicator (Labsonic M, M/s Sartorius, Melsungen, Germany) fitted with a titanium probe (3 mm tip diameter, 80 mm length and sonication capacity of 5–200 ml sample), having maximal power of 100 W and maximal frequency of 30 kHz was used for UAE. The UAE were performed in 150 ml amber colored glass vials maintaining 1 cm distance from the tip of the probe to the bottom of the extraction vial (to allow proper impingement of sound waves to the sample without touching the vial surface). The extraction vials were placed in ice bath and ice was replaced periodically to maintain the extraction temperature in the range of 1–8 °C.

Considering number of parameters and their levels, a 3-level CCRD design (34) of experiments was used to optimize the four UAE parameters—mean dp, sample weight to extracting solvent volume, ultrasonication frequency, and extraction time, to obtain an extract having the maximum yield of MT from mustard seeds (YM and BM). The design of experiment (DOE) matrix was obtained using the STATISTICA 8.0 software (Statsoft, Oklahoma, USA). The experimental domain of CCRD comprises of 18 runs (number of block = 1) including eight factorial points (coded as ± 1), eight axial or star points (coded as ± α) and two central points (coded as 0). The duplication of the central point was used to find the experimental error in the study. The details of CCRD design are presented in Table S1. The levels of each parameter i.e., mean dp (300, 425, 500 µm), ratio of sample weight to solvent volume (ratios of 1–5, 1–10, 1–15 w/v), ultrasonication frequency (21, 24, and 27 kHz) and extraction time (200, 400 and 600 s) were selected on the basis of yields of MT obtained from preliminary trials. Three independent extraction runs were conducted for a given set of extracting conditions with three independent batches of either species of mustard seeds.

Extracts thus obtained were centrifuged (C-24BL, M/s Remi, Mumbai, India) at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants collected were concentrated by rotary vacuum evaporator (M/s CCA 1110, Eyela corp., Koishikawa, Japan) at 50 mbar and 25 ± 2 °C (water bath temperature).

Purification of UAE extracts using solid phase extraction (SPE) and liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) methods

Presence of several co-extractants impeded identification and quantification of MT in the UAE extracts by HPLC and ELISA methods (data not shown). The extracts were therefore further purified adopting two strategies of LLE and SPE, in accordance with the reports of Reiter et al. (2005) and Chen et al. (2003), respectively, with few modifications (details provided in file S1). The purified extracts were subsequently diluted in methanol and MT was quantified by ELISA and HPLC analyses.

Estimation of MT in UAE extracts by enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses

ELISA and HPLC analyses were conducted to validate the yields of MT in the UAE extracts. MT in the extracts was quantified according to the method reported by Ansari et al. (2010), using ELISA kit specific for MT (M/s MP Biomedicals, LLC, Ohio, USA; with assay sensitivity of 3.0 pg/ml). For HPLC analyses, the extracts were diluted in HPLC grade methanol and then filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter. Amount of MT in the above filtrates was quantified using a JASCO MD 2015 plus HPLC system (Easton, US) in accordance with the method reported by Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee (2017).

MT has been successfully identified and quantified in both SPE and LLE-purified extracts. The purification scheme has been in Fig. S1. In LLE-purified extract, the amount of MT quantified by HPLC analysis was significantly (p < 0.05) different to those obtained by ELISA; whereas the above difference was insignificant (p > 0.05) in case of SPE-purified extract. The correlations between the amount of MT quantified by HPLC and that by ELISA method were ascertained for both SPE and LLE purified extracts. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) values were found to be in the range of 0.85–0.88 for SPE-purified extracts and 0.64–0.65 for LLE-purified extracts. Higher r value indicated that MT quantification was more reliable and unambiguous using SPE method. Therefore SPE was employed for purification of all UAE extracts and MT was then quantified by HPLC–PDA. The extracts of BM and YM seeds obtained at the optimized conditions of UAE, having highest amounts of MT (discussed later), were coded as BMbest and YMbest, respectively. The extracts were stored in amber color screw capped glass vials at − 20 °C in the dark, until further analyses. Occurrence of several peaks (discussed later) other than that of MT, could possibly have been due to co-extraction of other antioxidants and fatty acids of mustard seeds.

Analysis of effects of sonication on YM seed matrix by FE-SEM analysis

To evaluate the physical effects of cavitation during UAE on the YM seed matrix, the pre-extraction and post-extraction matrices were observed under light microscope (M/s Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and also under FE-SEM (details provided in file S1).

Evaluation of total phenolic contents and reducing power of the extracts

Total phenolic contents (Spanos and Wrolstad 1990) of the extracts were estimated using Folin-Ciocalteu’s method and expressed as mg GAE/g of mustard seeds. Reducing power of the extracts was determined from the BHT (Butylated Hydroxy Toluene) standard curve and expressed as mg BHT/g of mustard seeds (Oyaizu 1986).

Evaluation of antioxidant activities of BMbest and YMbest

Assays of ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) (Benzie and Strain 1999), DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging activities (Aiyegoro and Okoh 2010) and reducing power (Oyaizu 1986) of UAE extracts were conducted to evaluated the antioxidant activities of the extracts. However, the extract could have one or more Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) which may contribute to false positive absorbance (Bisson et al. 2016) in the spectrophotometric assay and therefore was further subjected to electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. EPR spectroscopy has been conducted in accordance with the method reported by Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee (2017).

Chemical profiling of BMbest and YMbest

FT-IR analysis

FT-IR analysis was performed to preliminarily identify the co-extracted compounds in the BMbest and YMbest in accordance with the method reported by Chakraborty et al. (2019). The spectrums of the additional peaks in the HPLC–PDA chromatogram were matched with available FT-IR spectrums (Spectrabase™ database), of the antioxidants namely lutein, tocopherol, ascorbic acid, squalene, limonene and linalool; and fatty acids such as oleic acid. Since the FT-IR spectrums indicated the presence of several antioxidant compounds and fatty acids in the extracts (discussed later), the extracts were subjected to fatty acid and antioxidant profiling by GC and LC–ESI–MS analyses, respectively.

Fatty acid profiling

The fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) of BMbest and YMbest were prepared and analysis of the FAME samples was conducted using Trace GC 700 system (M/s Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) equipped with a TR-1 capillary column (L × I.D. 30 m × 0.32 mm, 0.25 μm film thickness) and flame ionization detector (FID), in accordance with the method reported by Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee (2017) (details provided in file S1).

Assessment of toxicities of BMbest and YMbest

Heavy metal toxicity

Since titanium contamination in UAE extracts is a common phenomenon in probe sonication extraction, energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis of YMbest was performed (details provided in file S1).

Evaluation of acute oral toxicity in rat model

Evaluation of acute oral toxicity of BMbest and YMbest was conducted as per OECD guidelines 425 using the limit dose of 5000 mg/kg b.w in Wistar albino rats (OECD 2001) (details provided in file S1).

Assessment of quality of YMbest

Identification of co-extracted compounds in YMbest using LC–ESI–MS

YMbest possessing higher antioxidant potency than BMbest (discussed later) was subjected to LC–ESI–MS analysis for identification of co-extracted antioxidants therein. LC–ESI–MS analysis was conducted in according to the method reported by Halder et al. (2017), with few modifications (details provided in file S1). Identification of components of the extract was based on matching the mass spectra with the NIST 2007 library (2007) and literature reports (USDA 2018; Miyazawa and Kawata 2006).

Assessment of synergism by evaluation of SE values

The synergism among the co-extracted antioxidants was ascertained in accordance with the method reported by Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee (2018) by evaluating DPPH radical scavenging capacities of the antioxidants.

Determination of ultrasonic intensity and acoustic energy density utilized under optimised UAE conditions

The ultrasonic intensity and acoustic energy density utilized under optimised UAE conditions were evaluated using standard equations (Tiwari 2015) (details provided in file S1).

Statistical analyses

Yield of MT has been expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experimental runs. All the assays related to chemical profiling were performed in triplicate and results are also reported as mean ± SD of three values. Statistical analysis of the data was conducted by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), RSM and regression modeling. Significant differences between means were determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test. A p value of ≤ 0.05 was used to verify the significance of the tests. In the present study, STATISTICA 8.0 software (Statsoft, Oklahoma, USA) was used to test the experimental results.

Results and discussion

Optimization of UAE parameters on the basis of yields of MT

The optimized conditions of UAE that yielded highest amount of MT (for both YM and BM seeds) were: mean dp = 425 µm, 1:15 ration (g/ml) of sample weight (5 g dry weight) to solvent volume (viz. 75 ml extracting solvent), ultrasonication frequency of 30 kHz and extraction time of 400 s. The amounts of MT obtained at the said optimized conditions were 194.02 ± 2.45 and 205.80 ± 1.67 ng/g of dry BM and YM seeds, respectively (Table 1). It was found that at the above optimized conditions of UAE, yield of MT from YM seeds was significantly (p = 0.03) higher vis-à-vis that from BM seeds, which corroborated well with the amounts of protein and moisture present therein (Table S2).

Table 1.

Yields of MT from UAE extracts of BM and YM seeds

| No of runs | Extraction time (s) | Ultrasonication frequency (kHz) | Particle diameter of mustard seeds (µm) | Volume of extracting solvent (ml) | Yield of MT from brown mustard seeds (ng/g of dry seeds)a | Yield of MT from yellow mustard seeds (ng/g of dry seeds)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factorial points | ||||||

| 1 | 600.00 | 27.00 | 500.00 | 50.00 | 187.17 ± 2.94a | 180.61 ± 1.36a |

| 2 | 600.00 | 27.00 | 300.00 | 50.00 | 185.70 ± 1.11b | 184.32 ± 2.32b |

| 3 | 600.00 | 21.00 | 500.00 | 100.00 | 186.79 ± 0.99c | 185.55 ± 1.21c |

| 4 | 200.00 | 27.00 | 300.00 | 100.00 | 188.12 ± 1.21d | 176.30 ± 0.99d |

| 5 | 600.00 | 21.00 | 300.00 | 100.00 | 184.44 ± 1.43e | 176.54 ± 1.68d |

| 6 | 200.00 | 21.00 | 500.00 | 50.00 | 176.86 ± 1.04f | 167.04 ± 2.28e |

| 7 | 200.00 | 27.00 | 500.00 | 100.00 | 192.37 ± 1.12 | 195.06 ± 3.89f |

| 8 | 200.00 | 21.00 | 300.00 | 50.00 | 173.21 ± 2.21h | 179.26 ± 1.21b |

| Axial points | ||||||

| 9 | 63.64 | 24.00 | 425.00 | 75.00 | 180.85 ± 1.56i | 185.56 ± 2.21c |

| 10 | 736.36 | 24.00 | 425.00 | 75.00 | 186.06 ± 1.66b | 189.63 ± 1.56g |

| 11 | 400.00 | 18.95 | 425.00 | 75.00 | 176.90 ± 1.25j | 172.47 ± 1.65h |

| 12# | 400.00 | 29.05 | 425.00 | 75.00 | 193.88 ± 1.99k | 198.85 ± 2.13i |

| 13 | 400.00 | 24.00 | 252.62 | 75.00 | 183.47 ± 1.33l | 185.56 ± 1.219 |

| 14 | 400.00 | 24.00 | 597.38 | 75.00 | 189.01 ± 1.52m | 187.78 ± 2.21j |

| 15 | 400.00 | 24.00 | 425.00 | 32.96 | 186.54 ± 2.66db | 187.04 ± 1.97j |

| 16 | 400.00 | 24.00 | 425.00 | 117.04 | 191.48 ± 3.33n | 185.19 ± 0.98c |

| Center points | ||||||

| 17 | 400.00 | 24.00 | 425.00 | 75.00 | 191.10 ± 0.47n | 196.67 ± 0.21k |

| 18 | 400.00 | 24.00 | 425.00 | 75.00 | 190.77 ± 0.99n | 197.04 ± 0.37k |

Different letters in a row indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level; #Since the optimized conditions of UAE as predicted by RSM analysis was slightly different to those obtained at experimental conditions, MT extraction were conducted with five independent batches of BM and YM seeds, at the predicted conditions. The yields of MT were found to be 194.02 ± 2.45 and 205.80 ± 1.67 ng/g of dry BM and YM seeds, respectively, with % RSDs of 1.45% and 2.66% respectively

aYields of MT from YM and BM seeds are mean ± SD of three independent extractions of each species of mustard seeds

According to Setyaningsih et al. (2016), MT being an tryptophan derivative, amount of the same in a food matrix is directly proportional to its protein content. Moreover, Jime´nez et al. (2007), have reported higher yield of UAE extract of virgin olive oil from high moisture (> 50%) containing olives compared to is low-moisture counterpart (< 50%). Similarly, YM seeds, having higher protein (23.45 ± 1.20% d.w.b in YM via-à-vis 21.92 ± 1.00% d.w.b in BM) and moisture (9.47 ± 0.05% d.w.b in YM via-à-vis 3.51 ± 0.01% d.w.b in BM) contents than BM seeds (Table S2), yielded greater amount of MT in its UAE extract in agreement with the above findings. Therefore, it was suggested that difference in the MT contents between the two species of mustard seeds, investigated in our study, could be due to their differences in protein and/or moisture contents.

Generation of response curves and regression modeling

The effects of extraction time (X1), ultrasonication frequency (X2), particle size (X3), and ratio of sample weight to solvent volume (X4) on the extraction yields of MT are shown in Fig. 1a (for BM seeds) and Fig. 1b (for YM seeds). Regression modeling was used for characterization of the response surfaces. The second order polynomial equation that fitted our experimental variables is given below (Eq. 1).

| 1 |

where Y (Eq. 1) represents the experimental response i.e., yield of MT from BM (Eq. 2) and yield of MT from YM (Eq. 3), B0, Bi, Bii, and Bij are constants and regression coefficients of the model; Xi and Xj are two independent variables in coded forms. The expanded models include linear, quadratic and cross-product terms as shown below (with intercept):

| 2 |

| 3 |

Both equations (Eq. 2 for BM seeds and Eq. 3 for YM seeds) explained the effects of X1, X2, X3, X4 on the response of Y (yield of MT). The significance of the investigated factors and their interactions were also examined. The yields of MT (Table 1) from BM and YM seeds were found to be significantly dependent (p = 0.00) on the above extraction process parameters, in both linear and quadratic forms. For BM seeds, the two-level interaction factors which have no significant effect on the yields of MT were: X1X3 (p = 0.50) and X2X4 (p = 0.84); whereas, the two-level interaction factors without any significant effect for YM seeds were X2 X3 (p = 0.82) and X2X4 (p = 0.55).

Fig. 1.

Response surfaces indicating yields of MT from a BM seeds, b YM seeds, as a function of seed mean dp (300, 425, 500 µm), ratio of sample weight to solvent volume (ratios of 1–5, 1–10, 1–15 w/v), ultrasonication frequency (21, 24, and 27 kHz) and extraction time (200, 400 and 600 s)

Two-way ANOVA of the models (Table S3) showed good F values (Fisher’s variance ratio) (24.52–1267.26 for BM seeds and 20.92–756.63 for YM seeds), indicating interactions among the variables to be significant. To check for the adequacy of the above regression models and violations of the basic assumptions of the same, a ‘residual analyses’ was performed with the experimental data in accordance with the method of Montgomery (2001a). Examination of the residuals showed them to be ‘structure less’, i.e., having no obvious pattern, which proved the adequacy of the models. The plots of predicted yields (ng/g of dry seeds) of MT from BM and YM seeds with the observed yields of the same (ng/g of dry seeds), showed very close fits (Fig. S2). Thus statistically significant multiple regression relationships (R2 = 0.99 for yield of MT from BM; R2 = 0.98 for yield of MT from YM) among the independent variables and the responding variables were established. The complete quadratic models showed very good fit.

Analysis of the response surfaces

From the test statistics of the regression models discussed above, it was observed that all the extraction parameters had significant effect on yields of MT from BM and YM seeds. To determine the optimal processing conditions of extraction of MT from BM seeds, the optimal values of X1, X2, X3 and X4, the first partial derivatives of the regression equation was conducted with respect to X1, X2, X3 and X4 and set to zero. The second order regression equations were converted into matrix forms as has been described by Montgomery (2001b) and Ge et al. (2002). The points thus obtained are known as the stationary points: X1S, X2S, X3S, X4S (X1S = 366.13 s, X2S = 28.59 kHz; X3S = 477.58 µm, X4S = 107.44 ml for BM seeds and X1S = 209.83 s, X2S = 28.50 kHz; X3S = 443.40 µm, X4S = 65.96 ml for YM seeds). The yields of MT from BM and YM seeds predicted at these stationary points were 195.59 and 202.98 ng/g of dry BM and YM seeds, respectively, in agreement with those obtained under similar experimental conditions (194.02 ± 2.45 and 205.80 ± 1.67 ng/g of dry BM and YM seeds, respectively).

Characterization of the response surfaces

A response curve is characterized by determining whether the stationary point obtained above is a point of maximum response, minimum response or a saddle point. For this purpose, regression equations were transformed to their canonical forms and the eigen values were determined in accordance with the method described by Montgomery (2001a). Since the eigen values obtained for yields of MT from both BM (− 0.000027, − 0.0001132, − 0.000796 and − 0.193574) and YM (− 0.000032, − 0.000183, − 0.006953 and − 0.473818) seeds were negative, XS for either case was a point of maxima.

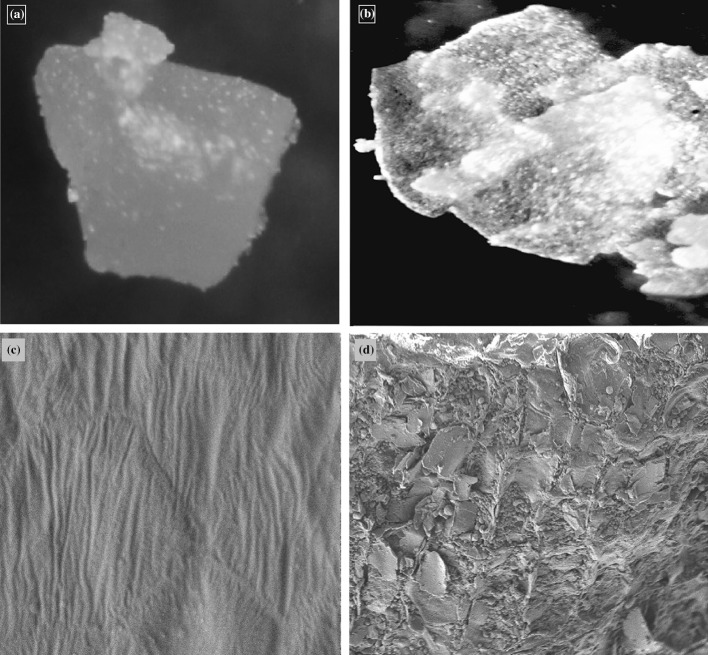

Evaluation of physical effects of cavitation on YM seed matrix by microscopic and FE-SEM image analyses

Microscopic and FE-SEM images of pre-extraction and post-extraction YM seed particles (Fig. 2) revealed regular, intact, smooth surfaces of the pre-extraction seed matrix of YM seeds, whereas several micro-fractures and crevices are prominent on the surfaces of their post sonication counterparts. A similar effect of ultrasonication has also been reported by Jadav et al. (2016) during extraction of oil from date seeds. Therefore, it is evident that sonication had successfully disrupted the cell walls of mustard seed matrix, and facilitated permeation of ethanol-water into the seed matrix which in turn aided extraction of antioxidants, specifically MT from the same.

Fig. 2.

Microscopic and FE-SEM images (400X magnification) of the surface of a yellow mustard seed particle; a, c pre-extraction matrix, b, d post extraction matrix

Total phenolic contents, reducing power and antioxidant activities of the extracts

Total phenolic contents, reducing power and antioxidant activities (by DPPH and FRAP) of BMbest and YMbest are presented in Table 2. The extracts exhibited good reducing power (34.84 ± 1.70–47.16 ± 2.21 mg BHT/g of dry BM and YM seeds, respectively); however the total phenolic contents were (1.73 ± 0.11 mg of GAE/g of dry BM seeds and 2.75 ± 0.13 mg of GAE/g of dry YM seeds) not that appreciable. The IC50 values of 2.29 ± 0.10 mg/ml for BMbest and 0.91 ± 0.01 mg/ml for YMbest revealed that either extract has strong antioxidant activity (obtained by spectrophotometric method). EPR spectroscopy of the BMbest and YMbest also showed 72.25 ± 2.01% and 75.49 ± 3.01% DPPH radical scavenging activities, respectively (Fig. S3). The DPPH radical scavenging activities obtained by EPR spectroscopy corroborated well with the spectrophotometric results. The above results suggested that the antioxidant activity of YMbest was significantly (p = 0.035) higher than that of BMbest. This difference between the antioxidant potencies of the YMbest and BMbest is possibly due to the difference between their MT contents (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

IC50 value of DPPH radical scavenging activity, FRAP, total phenolic content and reducing power of BMbest and YMbest

| Name of extracts | IC50 value of DPPH radical scavenging activity (mg/ml)a | FRAP (mmol FeSO4 equivalent/g of dry mustard seeds)a | Total phenolic content (mg of GAE/g of dry mustard seeds)a | Reducing power (mg of BHT/g of dry mustard seeds)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMbest | 2.29 ± 0.10a | 77.66 ± 3.54a | 1.73 ± 0.11a | 47.16 ± 2.21a |

| YMbest | 0.91 ± 0.01b | 75.14 ± 2.62b | 2.75 ± 0.13b | 34.84 ± 1.70b |

Different letters in a column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level

aIC50 of DPPH radical scavenging, FRAP, total phenolic content and reducing power are mean ± SD of three independent extraction of three batches of brown and yellow mustard seeds

Chemical profiling of YMbest and BMbest

FT-IR analyses of YMbest and BMbest

The FT-IR spectra of YMbest and BMbest were analysed using the wavenumbers reported by Dyer (2012). The transmission (%T) peaks of the antioxidant compounds in the extracts were exactly similar to those present in an extract obtained by conventional solvent (ethanol:water::1:1, v/v) extraction in shake flask (unpublished data), suggesting that no biochemical changes occurred during UAE. The FT-IR analysis affirmed that the extraction of MT from YM seeds occurred solely due to cavitation effects of sonication.

The functional groups and bonds present in YMbest are presented in Table 3. FT-IR spectra indicated the presence of C=C (1463.8 cm−1), methoxy group (2854.55 cm−1) and 5 membered ring C–C multiple bond stretching (1744.12 cm−1) in the extracts, which confirmed the presence of MT in YMbest and BMbest. Peaks in the range of 3008 (unsaturated double bonds, =CH, cis bonds) and 1654 (–C=C–, cis bonds) suggested the presence of fatty acids in the extracts. The FT-IR spectrums of standard oleic acid, limonene and tocopherol also suggested their presence in the extracts. Moreover, the absoprtion bands of YMbestand BMbest also indicated the presence of few aromatic compounds (722.04 cm−1) and alkene groups (1417.76 cm−1 and 2854.55 cm−1) in YMbest and BMbest. The above findings concluded that several antioxidants and fatty acids have been co-extracted during UAE along with MT.

Table 3.

FT-IR analyses: Absorption bands of YMbest

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Associated vibrations of bonds in YMabest |

|---|---|

| 3472.01 | Alcohols and phenols (intramolecular H bond) |

| 3007.45 | Amines (imines; = N–H, one band) |

| 2854.55 | Aldehydes (C–H stretching vibrations two bands) or methoxy group |

| 2087.75 | Unsaturated nitrogen compounds (isocyanides) |

| 1744.12 | 5 membered ring C–C multiple bond streching or ester stretching vibration |

| 1652.00 | C–C multiple bond stretching |

| 1463.80 | Alkane, CH2 |

| 1417.76 | Alkene |

| 1377.27 | Alkane |

| 1238.54 | C=S stretching vibration |

| 1163.13, 1100.03 | Sulphur compounds |

| 758.22 | Aromatic substitution type five adjacent H atoms |

aFT-IR spectra of YMbest analyzed in accordance with Dyer (2012)

Fatty acid profiles of BMbest and YMbest

From the FAME-GC analysis of the UAE extracts, erucic acid contents of BMbest and YMbest were 0.66 ± 0.52 and 0.84 ± 0.08 g/100 g of total fatty acids, respectively. The erucic acid contents in the said extracts were below 2% of total fatty acid contents, which affirmed safety of these extracts for human consumption. The ratios of ω6–ω3 obtained for BMbest and YMbest were 0.50 ± 0.02 and 0.42 ± 0.02, respectively (Table 4). It was found that the ratios were below the desirable range, i.e., from 1 to 4 (Sen 2012), which are not likely to have any adverse health consequences in human.

Table 4.

Major fatty acids in the BMbest and YMbest

| Fatty acid carbon no | Major fatty acids | BMbest (g/100 g of fatty acid)a | YMbest (g/100 g of fatty acid)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| C8:0 | Caprylic acid | 6.95 ± 0.10 | 12.31 ± 0.52 |

| C10:0 | Capric acid | 12.31 ± 0.95 | 17.06 ± 1.44 |

| C16:1 | Palmitoleic acid | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| C18:1 | Oleic acid | 0.22 ± 0.31 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| C18:2 | Linoleic acid | 0.61 ± 0.88 | 1.48 ± 0.08 |

| C18:3 | Linolenic acid | 1.22 ± 0.74 | 3.53 ± 0.28 |

| C20:1 | Cis-11-Eicosenoic acid | 1.30 ± 0.52 | 1.42 ± 0.09 |

| C22:1 | Erucic acid | 0.66 ± 0.52 | 0.84 ± 0.18 |

| ω6/ω3 | – | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.02 |

Different letters in a column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level

aFatty acid contents of BMbest and YMbest are mean ± SD of three independent extractions of three batches of BM and YM seeds

Toxicity and safety of BMbest and YMbest

EDX analyses of BMbest and YMbest revealed that the extracts are free from any heavy metal contaminant, especially from the titanium probe of the ultrasonicator. Moreover, the acute oral toxicity of the extracts were found to be more that 5000 mg/kg b.w. of rats, which confirmed the extracts to be non-toxic. Thus, the extracts per se are ‘safe’ for consumption as a food supplement.

Quality of YMbest

LC–ESI–MS (Fig. S4) analysis successfully identified the co-extracted compounds in YMbest. In the mass spectrum of YMbest, peaks of fatty acids (namely oleic acid, erucic acid, and linoleic acid) were also found along with the peaks of major antioxidants such as tocopherol, ascorbic acid, limonene and linalool. The fatty acids identified in the extracts were similar to those obtained by FAME-GC-FID analysis.

By synergism study, a good synergistic co-existence (SE value = 1.13, i.e., greater than unity) of the above antioxidants was found in YMbest. Antioxidant activity of linalool was found to be negligible, tocopherol being the major antioxidant followed by ascorbic acid and MT.

Ultrasonic intensity and acoustic energy density utilized under optimised UAE conditions

Acoustic energy below 1 W/cm2 is considered as low-intensity sonication region and those between 10 and 1000 W/cm2 are considered as high-intensity sonication region (Tiwari 2015). In our study, the ultrasonic intensity of 47.88 W/cm2 was applied at the optimized extraction conditions of UAE, indicating high-intensity acoustic energy utilization during UAE extraction of MT from mustard seeds. This high intensity sonication energy had generated high cavitation energy in the extraction medium (Tiwari 2015), which possibly easily disrupted the hard seed coats of mustard seeds and therefore allowed enhanced solvent penetration across the cell walls.

The energy density required at the optimized extraction conditions of UAE was 0.62 W/cm3, which is similar (0.26 W/cm3) to that reported by Upadhyay et al. (2015), who have extracted flavonoids and phenolic compounds from dried leaves of Ocimum tenuiflorum by UAE. Although, high intensity sonication was employed in our study, the energy consumption was meagre, possibly due to the use of high polar solvents viz. ethanol and water (1:1, v/v) as extracting solvents which are reportedly known to increase acoustic cavitation in extraction media (Hemwimol et al. 2006). Moreover, use of these solvents reduced loss of ultrasonic power during UAE, which is a common phenomenon when organic solvents are used. Therefore, this study demonstrates promising use of UAE technology as a low energy consuming extraction procedure for extraction of the biotherapeutic molecule i.e., MT from mustard seed and possibility of easy scale up to commercial level.

Antioxidant synergy in YMbest by reductionism

In this study, the green extraction method of UAE has delivered a ‘phytomelatonin-rich and erucic acid-lean’ extract from yellow mustard seeds. Although reductionism through UAE and rigorous optimization of process variables was conducted using statistical design models and analytical tools, chemical profiling and SE value revealed a synergistic consortium of antioxidants in the extract and not selectively MT as a single antioxidant. Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee (2017) have extracted MT (660.72 ± 41.05 ng/g of dry mustard seeds) from yellow mustard seeds using SC-CO2 extraction technology. Post-extraction purification of the SC-CO2 extract of YM seeds (same species investigated for UAE extraction) has been conducted adopting the SPE method described in the present study by our research group. It has been found that the amount of MT (314.63 ± 0.05 ng/g of dry mustard seeds) in the purified SC-CO2 extract of yellow mustard seeds (unpublished data) was higher vis-à-vis that in the UAE extract of YM seeds (205.80 ng/g of dry mustard seeds). This is due to the higher selectivity of SC-CO2 extraction technology compared to UAE (Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee 2017).

However, the antioxidant activity of UAE extract in terms of DPPH radical scavenging activity (0.91 ± 0.01) was found to be higher compared to that obtained in the SC-CO2 extract (2.86 ± 1.29 mg/mL) (Chakraborty and Bhattacharjee 2017). In the UAE extract, the synergistic presence of MT with other antioxidants such as tocopherol, limonene and linalool conferred strong antioxidant activity to the same. Thus UAE technology could be successfully employed in obtaining phytomelatonin-rich extracts of BM and YM seeds having strong antioxidant synergy therein. The methodology developed in this study could be safely extrapolated to extraction of ‘a synergistic consortium of antioxidants’ from similar food matrices. The extracts of BM and YM seeds could be utilized as proactive ‘food supplements’.

Conclusion

This is the first study that established reductionism as a successful approach to obtain a synergistic consortium of antioxidants from mustard seeds. The ‘phytomelatonin-rich and erucic acid-lean’ extracts obtained from the above oilseeds (BM and YM seeds) by UAE could be considered as novel ‘green’ food supplements. While BMbest could be valued for its characteristic mild pungency and for its low erucic acid content, the YMbest could serve as a safe (low erucic acid) source of antioxidants, chiefly MT. The present investigation would enhance the usage of phytomelatonin through natural-product based drugs as healthy alternatives of synthetic melatonin.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to University Grant Commission (UGC), New Delhi, India [Ref.No: 1440/(NET-JUNE 2013)] for financial support. Authors are grateful to the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (Kolkata, India) for providing us the set up for EDX, FE-SEM, FT-IR analyses and TAAB Biostudy (Kolkata, India) for their assistance in LC–ESI–MS analysis. Authors also hereby acknowledge M/s Keva Flavours Pvt Ltd., Mumbai, India for gifting us the pure standards of limonene and linalool and Department of Physiology, Nutrition and Microbiology, Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College, Midnapore, India for conducting acute oral toxicity study of UAE extracts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aiyegoro OA, Okoh AI. Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro antioxidant activities of the aqueous extract of Helichrysum longifolium. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:2–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altuntas E, Özgoz E, Taser ÖF. Some physical properties of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graceum L.) J Food Eng. 2005;71:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American spice Trade association (ASTA) Official analytical methods of the american spice trade association. 4. Washington, DC: American Spice trade association Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari M, Rafiee K, Yasa N, Vardasbi S, Naimi SM, Nowrouzi A. Measurement of melatonin in alcoholic and hot water extracts of Tanacetum parthenium, Tripleurospermum disciforme and Viola odorata. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2010;18:73–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnao MB. Phytomelatonin: discovery, content, and role in plants. Adv Bot. 2014;2014:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2014/815769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnao MB, Hernández-Ruiz J. Phytomelatonin, natural melatonin from plants as a novel dietary supplement: sources, activities and world market. J Funct Foods. 2018;48:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.06.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnao MB, Hernández-Ruiz J. Phytomelatonin versus synthetic melatonin in cancer treatments. Biomed Res Clin Pract. 2018;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) (2006) Official methods of analysis of AOAC international, 18th edn, Washington, DC

- Benzie FF, Strain JJ. Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay: direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee P, Ghosh PK. Role of dietary serotonin and melatonin in human nutrition. In: Ravishankar GA, Ramakrishna A, editors. Serotonin and melatonin their functional role in plants, food, phytomedicine, and human health. 1. Florida: CRC Press; 2016. pp. 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee P, Ghosh PK, Vernekar M, Singhal RS. Role of dietary serotonin and melatonin in human nutrition. In: Ravishankar GA, Ramakrishna A, editors. Serotonin and melatonin: their functional role in plants, food, phytomedicine, and human health. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016. pp. 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. SpectraBase™. http://spectrabase.com/. Accessed 8 Sept 2018

- Bisson J, McAlpine JB, Friesen JB, Chen SN, Graham J, Pauli GF. Can invalid bioactives undermine natural product-based drug discovery? J Med Chem. 2016;59:1671–1690. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Bhattacharjee P. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of melatonin from Brassica campestris: in vitro antioxidant, hypocholesterolemic and hypoglycaemic activities of the extracts. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2017;8:2486–2495. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Bhattacharjee P. Design of lemon–mustard nutraceutical beverages based on synergism among antioxidants and in vitro antioxidative, hypoglycaemic and hypocholesterolemic activities: characterization and shelf life studies. J Food Meas Charact. 2018;12:2110–2120. doi: 10.1007/s11694-018-9826-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Paul K, Mallick P, Pradhan S, Das K, Chakrabarti S, Nandi DK, Bhattacharjee P. Consortia of bioactives in supercritical carbon dioxide extracts of mustard and small cardamom seeds lower serum cholesterol levels in rats: new leads for hypocholesterolemic supplements from spices. J Nut Sci. 2019;8:1–15. doi: 10.1017/jns.2018.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Huo Y, Tan DX, Liang Z, Zhang W, Zhang Y. Melatonin in chinese medicinal herbs. Life Sci. 2003;73:19–26. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(03)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E, Greenacre D, Lookwood GB. Adverse effects and toxicity of neutraceuticals. In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, editors. Reviews in food and nutrition toxicity, vol 3. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 183–184. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado J, del Terrón M, Garrido M, Barriga C, Paredes SD, Espino J, Rodríguez AB. Systemic inflammatory load in young and old ringdoves is modulated by consumption of a jerte valley cherry-based product. J Med Food. 2012;15:707–712. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer JR. Applications of absorption spectroscopy of organic compounds. 1. Delhi: PHI Learning; 2012. pp. 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Wang M, Zhao Y, Han P, Dai Y. Melatonin from different fruit sources, functional roles, and analytical methods. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2014;37:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) (2017) The Gazette of India, Extraordinary (part III—Sec. 4), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Notification, New Delhi. https://www.fssai.gov.in/home/fss-legislation/notifications/gazette-notification.html. Accessed 14 July 2018

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) (2003) Erucic acid in food: a toxicological review and risk assessment, Technical report series no. 21. https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/documents/Erucic%20acid%20monograph.pdf. Accessed 3 Mar 2018

- Ge Y, Ni Y, Yan H, Chen Y, Cai T. Optimization of the supercritical fluid extraction of natural vitamin E from wheat germ using response surface methodology. J Food Sci. 2002;67:239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb11391.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halder D, Dan S, Pal M, Biswas E, Chatterjee N, Sarkar P, Halder U, Pal TK. LC–MS/MS assay for quantitation of enalapril and enalaprilat in plasma for bioequivalence study in Indian subjects. Future Sci OA. 2017;3:FSO165. doi: 10.4155/fsoa-2016-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemwimol S, Pavasant P, Shotipruk A. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of anthraquinones from roots of Morinda citrifolia. Ultrason Sonochem. 2006;13:543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav AJ, Holkar CR, Goswami AD, Pandit AB, Pinjari DV. Acoustic cavitation as a novel approach for extraction of oil from waste date seeds. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;4:4256–4263. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jime´nez A, Beltra´n G, Uceda M. High-power ultrasound in olive paste pretreatment effect on process yield and virgin olive oil characteristics. Ultrason Sonochem. 2007;14:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner AB, Case JD, Takahashi Y, Lee TH, Mori W. Isolation of melatonin, the pineal gland factor that lightens melanocyteS1. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:2587–2587. doi: 10.1021/ja01543a060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li S, Zhou Y, Meng X, Zhang JJ, Xu DP, Li HB. Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39896–39921. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina M, Lampe JW, Birt DF, Appel LJ, Pivonka E, Berry B, Pivonka E, Berry B, Acob DR. Reductionism and the narrowing nutrition perspective: Time for reevaluation and emphasis on food synergy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:1416–1419. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00342-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchester LC, Tan DX, Reiter RJ, Park W, Monis K, Qi W. High levels of melatonin in the seeds of edible plants: possible function in germ tissue protection. Life Sci. 2000;67:3023–3029. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Li Y, Li S, Zhou Y, Gan RY, Xu DP, Li HB. Dietary sources and bioactivities of melatonin. Nutrients. 2017;9:1–64. doi: 10.3390/nu9040367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa M, Kawata J. Identification of the main aroma compounds in dried seeds of Brassica hirta. J Nat Med. 2006;60:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s11418-005-0009-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery DC. Response surface methods and other approaches to process optimization, design and analysis of experiments. New York: Wiley; 2001. p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery DC. Experiments with a single factor: the analysis of variance, design and analysis of experiments. New York: Wiley; 2001. pp. 427–430. [Google Scholar]

- NIST standard reference database number 69; Linstrom P, Mallard WG (eds) National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA. http://webbook.nist.gov/. Accessed 13 Aug 2018

- Oyaizu M. Studies on products of BMing reaction: antioxidative activities of products of BMing reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nut. 1986;44:307–315. doi: 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ, Manchester LC, Tan DX. Melatonin in walnuts: influence on levels of melatonin and total antioxidant capacity of blood. Nutrition. 2005;21:920–924. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen DP (2012) Fats and oils in health and nutrition. Oil Technology Association of India. News Letters, Eastern region, November 2011–June 2012, pp 19–23. http://www.otai.org/newsLetter/ez/newsLetter_Ez_Nov%202011_June_2012.pdf. Accessed 18 Mar 2018

- Setyaningsih W, Duros E, Palma M, Barroso CG. Optimization of the ultrasound-assisted extraction of melatonin from red rice (Oryza sativa) grains through a response surface methodology. Appl Acoust. 2016;103:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.apacoust.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spanos GA, Wrolstad RE. Influence of processing and storage on the phenolic composition of Thompson seedless grape juice. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38:1565–1571. doi: 10.1021/jf00097a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 425 (2001) Organization of economic co-operation and development guidelines 1–26. http://www.oecd.org/chemicalsafety/risk-assessment/1948378.pdf/ Accessed 26 June 2017

- Tiwari B. Ultrasound: a clean, green extraction technology trends in analytical chemistry. Ultrason Sonochem. 2015;71:100–109. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA) (2018) National nutrient database for standard reference legacy release. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show?n1=%7BQv%3D1%7D&fg=&fgcd=&man=&lfacet=&count=&max=25&sort=c&qlookup=&offset=475&format=Full&new=&rptfrm=nl&ndbno=02024&nutrient1=301&nutrient2=&nutrient3=&subset=0&totCount=8038&measureby=g. Accessed 5 Aug 2018

- Upadhyay R, Nachiappan G, Mishra HN. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of flavonoids and phenolic compounds from Ocimum tenuiflorum leaves. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2015;24:1951–1958. doi: 10.1007/s10068-015-0257-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.