Abstract

Abstract

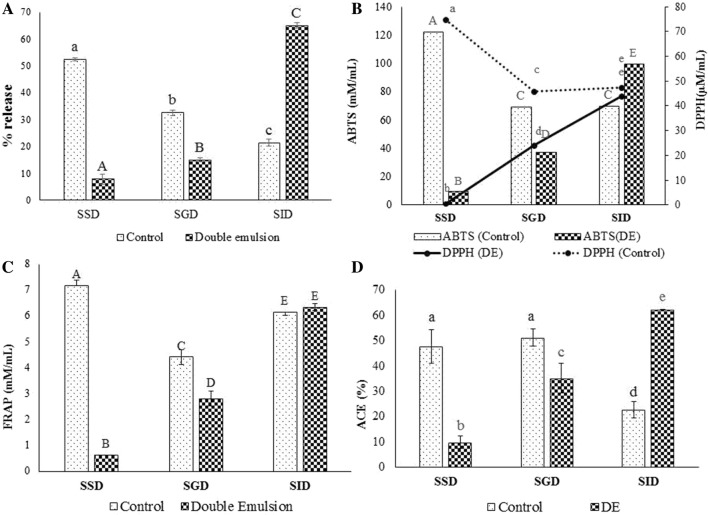

Controlled release of Emblicanin rich water soluble extract of Emblica officinalis (EEO) from the inner phase of water-in-oil-in-water type double emulsion (DE), during in vitro digestion and phagocytosis was investigated. It was observed that release of EEO (measured as total polyphenols and gallic acid by HPLC) from inner phase of DE was maximum during intestinal digestion followed by gastric and salivary digestion. Main reason was increased particle size of emulsion droplets and change in zeta potential by the action of digestive enzymes. ACE inhibitory activity and antioxidant activity [determined by ABTS (99.58 ± 7.24 mM/mL), DPPH (76.93 ± 0.93 µM/mL) and FRAP (6.34 ± 0.13 mM/mL)] was observed on the higher side in the intestinal digesta of EEO-encapsulated DE (EEODE) as compared to salivary and gastric digesta. However, reverse trend was observed in control sample (unencapsulated-EEO). Phagocytic activity of EEODE increased with increasing its concentration of 2–10 µL. These results indicated that the developed DE matrix was effective in protecting active components of EEO during harsh digestive conditions as evident by sustained/target release. This newly developed EEODE formulation can be used as functional ingredient in the preparation of different dairy and food based functional products.

Graphic abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-019-04171-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Emblica officinalis, Encapsulation, Polyphenols, Controlled release, Phagocytosis

Introduction

Herbal products are currently being investigated due to their numerous health benefits and their role in alternative therapies. Emblica officinalis belongs to the Euphorbiaceae family that possesses high antioxidant, anticancer, lipid-lowering, and anti-HIV potentials (Mandarika et al. 2014; Rajak et al. 2004; Rao et al. 2005). E. officinalis contains a range of polyphenols, especially hydrolysable tannins (10–12%) such as quercetin, emblicanin A, emblicanin B, punigluconin and pedunculagin responsible of numerous health benefits. It is well documented that flavonoids from E. officinalis are responsible for its antioxidant activity through mechanism related to angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition and modulation of oxidative stress (Actis-Goretta et al. 2006). These active components cannot be readily incorporated into food products because of their less stable nature. When any bioactive substance added directly to food products, there activity may be lost before reaching to the target site of action by the action of various gastric enzymes and change in the pH condition of digestion stages. Further, their direct addition may leads to undesirable changes in sensory, physico-chemical and textural characters of food products. Extensive research on development of suitable delivery matrices for supplementing herbal extracts into food products for their target delivery is under-way (Xu et al. 2018). Bioaccessibility of encapsulated ingredients largely depends on the hydrophilic stabilizer as it protects the active component in inner phase from degradation by the action of gastric enzyme and acidic environment (Aditya et al. 2015). Water-in-oil-in-water (W1/O/W2) double emulsion (DE) is formed by emulsifying a water-in-oil (W1/O) primary emulsion in outer aqueous phase (W2). Because of an additional protection layer (when compared to single emulsions), DE are currently highly explored as carrier systems for delivery of various functional ingredients (Matos et al. 2014). Several studies have proven the protective role of DE for the controlled release of single bioactive compounds such as anthocyanin, betalain, resveratrol, curcumin and catechin (Frank et al. 2012; Kaimainen et al. 2015; Xiao et al. 2017; Shaddel et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2018). However, research on release of herbal extracts mainly E. officinalis containing several active constituents with varying molecular weights (a complex bioactive mixture) from DE is scanty. In the current study, release of Emblicanin rich water soluble extract of E. officinalis (EEO) from DE during in vitro digestion was investigated. For the evaluation of DE stability during digestion, changes in the size of DE droplets, release of polyphenol from inner phase of DE, antioxidant and ACE inhibitory activities during digestion phase and phagocytosis was investigated.

Materials and methods

EEO was purchased from M/s. Plantae Herbal Extract Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi (Table 1). Pectin (GENU® pectin type LM-5 CS; M/s. CP Kelco, Huber India Company, Mumbai, India), polyglycerolpolyricinoleate (PGPR) 90 (DuPont-Dansico India Private Limited) and rice bran oil (local supermarket, Karnal, India) were used in the emulsion preparation. All the chemicals used in the study viz. 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) ammonium salt (ABTS), 2,4,6-tripyridyl triazine (TPTZ), ammoinum iron (II) sulphate hexahydrate, 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)-1, hippuryl-His-Leu acetate salt (HHL) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, India. Analytical grade hippuric acid (HA), quinoline and benzene sulfonyl chloride (BSC) were purchased from M/s. Thermo Fischer Scientific, India. All other chemicals used were of analytical grade and purchased from standard chemical suppliers.

Table 1.

Certificate of analysis of Emblicanin rich Emblica Officinalis extract

| Emblica Officinalis dry extract (30%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch no.: ANAM 1185 | |||

| S. no. | Parameter | Specification | Results |

| 1. | Appearance | Brownish black colored dry powder | Brownish black colored dry powder |

| 2. | Odour and taste | Characteristic odour and sour taste | Complies |

| 3. | Identification by TLC | Positive | Positive |

| 4. | pH of 1% w/v aqueous solution | 3–7 | 4.86 |

| 5. | Loss on drying (at 105 C) | NMT 5.0% | 2.86% |

| 6. | Total ash (w/w) | NMT 15.0% | 4.32% |

| 7. | Solubility in water (w/v) | NMT 85.0% | 94.0% |

| 8. | Particle size | 100% through 60 mesh | 100% through 60 mesh |

| 9. | Solubility in 50% alcohol (w/v) | NLT 70.0% | 76.2% |

| 10. | Emblicanin | NLT 31.72% | 30.0% |

| 11. | Heavy metals | NMT 20 PPM | NMT 20PPM |

Preparation of EEO encapsulated DE (EEODE)

EEO was encapsulated in a DE as per the protocol described by Chaudhary (2017). DE consists of three phases such as inner water phase, middle oil phase and outer water phase. The primary emulsion was created by drop wise addition of 45 g (w/w) of W1-phase containing 50% (w/w) of EEO into 105 g of rice bran oil (containing 4% (w/w) PGPR) and homogenization was done at 20,000 rpm for 5 min using Ultra-Turrax T-25 homogenizer (IKA Laboratory Equipment Ltd, Germany). From this primary emulsion 45 g was added to the W2-phase (consisting of 105 g of RO water with 2% (w/w) pectin as outer phase emulsifier). The mixture was then homogenized at 12,000 rpm for 5 min to obtain stable EEODE. The stability of EEODE was evaluated on the basis of particle size distribution, sedimentation stability, viscosity, and zeta potential in one of the other research by the same author.

Simulated gastrointestinal digestion

In vitro digestion of DE was performed as per Herrero-Barbudo et al. (2009). The model describes a procedure to mimic the digestive process in the mouth, stomach (gastric digestion) and small intestine (duodenal digestion). Briefly, 15 g of sample was transferred to a conical flask, and a saliva solution (9 mL, pH 6.5) containing organic and inorganic components and α-amylase (700 μg/L) was added, followed by incubation in a shaking incubator (New Brunswick Scientific, India) at 37 °C and 95 rpm for 5 min. Gastric juice (13.5 mL) with organic and inorganic components viz. mucin (3 g/L gastric juice), bovine serum albumin (1 g/L), and pepsin (1 g/L) from porcine stomach were added to the conical flask. The pH was adjusted to 1.1 and the solution was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and 200 rpm. Duodenal juice (25 mL, organic plus inorganic components, containing 3 g/L porcine pancreatin) and bile solution (9 mL, containing 6 g/L bovine bile) were added to the flask. Detailed procedure and composition of digestion phases adopted for the in vitro digestion is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table 2 respectively. After in vitro digestion process, samples were collected for estimation of total polyphenols and gallic acid. Two different samples viz. EEODE and EEO added to DE without encapsulation were subjected to in vitro digestion. Samples were drawn after each digestion step i.e. salivary, gastric and intestinal digestion for analysis. The controlled release of EEO was calculated using the following formula given by Oomen et al. (2002):

Table 2.

Composition and concentration of the various synthetic juices of the in vitro digestion

| Solution | Saliva | Gastric juice | Duodenal juice | Bile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic solution |

10 mL KCl (89.6 g/L) 10 mL KSCN (20 g/L) 10 mL NaH2PO4 (88.8 g/L) 10 mL Na2HPO4 (57 g/L) 1.7 mL NaCl (175.3 g/L) 1.8 mL NaOH (40 g/L) |

15.7 mL NaCl (175.3 mg/L) 3.0 mL NaH2PO4 (88.8 mg/L) 9.2 mL KCl (89.6 g/L) 18 mL CaCl2. 2 H2O (22.2 mg/L) 10 mL NH4Cl (30.6 g/L) 8.3 mL HCl (37%) |

40 mL NaCl (175.3 mg/L) 10 mL NaHCO3 (84.7 mg/L) 10 mL KH2PO4 (8 g/L) 6.3 mL KCl (89.6 g/L) 10 mL MgCl2 (5 mg/L) 180 μL HCl (37%) |

30 mL NaCl (175.3 g/L) 68.3 mL NaHCO3 (84.7 g/L) 4.2 mL KCl (89.6 g/L) 200 μL HCl (37%) |

| Organic solution | 8 mL urea (25 g/L) |

10 mL glucose (65 g/L) 10 mL glucuronic acid (2 g/L) 3.4 mL urea (25 g/L) 10 mL glucosamine hydrochloride (33 g/L) |

4 mL urea (25 g/L) | 10 mL urea (25 g/L) |

| Add to mixture organic + inorganic solution |

145 mg α-amylase 15 mg uric acid 50 mg mucin |

1 g BSA 1 g pepsin 3 g mucin |

9 mL CaCl2. 2 H2O (22.2 g/L) 1 g BSA 3 g pancreatin |

10 mL CaCl2. 2 H2O (22.2 g/L) 1.8 g BSA 6 g bile |

| pH | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 1.07 ± 0.07 | 7.8 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 0.2 |

The inorganic and organic solutions were augmented to 500 mL with distilled water

Total polyphenols, antioxidant activity and ACE inhibitory activity

Total polyphenols from the digested samples were estimated by the procedure described by Koczka et al. (2018). Antioxidant activity of different samples was determined by DPPH (Middha et al. 2015), ABTS (Middha et al. 2015) and FRAP assay (Koczka et al. 2018).

For total polyphenols 0.1 mL of sample and 0.9 mL of distilled water add 2.5 mL of diluted Folin reagent followed by addition of 2 mL of 7.5% sodium carbonate and incubate for 40 min at room temperature, and then the absorbance was determined by spectrophotometer at 760 nm. Total polyphenol estimated from a standard curve of gallic acid.

The samples were prepared in different concentrations with 60% methanol (acidified with concentrated HCl 0.1%) for DPPH. To 0.1 mL of sample, 2.9 mL of 0.1 mmol DPPH (prepared in 80% methanol) was added and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in darkness. Standard solution of trolox was also prepared using 80% methanol. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using UV–Vis Spectrophotometer.

For ABTS method two stock solutions were prepared using 7.4 mmol ABTS+ and 2.6 mmol potassium persulfate. The working solution was then prepared by mixing the two stock solutions in equal quantities and allowing them to react for 12 h at room temperature in the dark. The solution was then diluted by mixing 1 mL ABTS+ solution to 60 mL methanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.7–0.8 at 734 nm, using the spectrophotometer. FRAP reagent was freshly prepared and mixed in the proportion of 10:1:1 (v:v:v) for A:B:C solutions. Ascorbic acid was used for the standard curve and the assay was carried out at 37 °C (pH 3.6) using 0.1 mL sample or standard solution along with 3.0 mL FRAP reagent. After 10 min incubation at room temperature, the absorbances were read at 593 nm.

ACE inhibitory activities of sample were estimated by the method given by Cushman and Cheung (1971). ACE inhibitor assay is based on the hydrolysis of the synthetic peptide hippuryl-histidyl-leucine (HHL) by ACE to HA and histidyl-leucine (HL). HA released is directly proportional to the ACE activity. In this screening method, the released hippuric acid from the substrate HHL became yellow in colour by mixing with pyridine and benzene sulfonyl chloride. The intensity of the colour was determined colorimetrically at absorbance 492 nm.

Zeta potential and particle size distribution (PSD) characterization

The zeta potential (ZP) of the DE was measured using Zetasizer Nano-ZS90 (Malvern Instrument Ltd., Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) to determine the stability of the emulsion. The emulsions were diluted 100 times with RO water (w/w) and the experiment was carried out at 25 °C temperature as per the method of Kumar (2011). The results were expressed in mV.

Particle size distribution was measured by dynamic light scattering using a Malvern Particle Size Analyser (Mastersizer v3.50, Malvern UK). The optical parameters selected were a dispersant refractive index of 1.33 and particle refractive index of 1.52. The results were reported as surface mean diameter (d32), volume mean diameter (d43), span value, size below which all particles contribute 10% population [Dv(10)], size below which all particles contribute 50% population [Dv(50)] and size below which all particles contribute 90% population [Dv(90)]. PSD based on volume density was recorded in graphical form and calculation was based on the Mie scattering theory. Sample was diluted to 1:100 for the testing.

Quantification of gallic acid by HPLC

Estimation of gallic acid was performed by HPLC–UV with Agilent 1100 series HPLC system (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany) with diode array detector (280 nm) and injection with 20 µL sample. Compounds were separated on a 4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5-µm pore size Zorbax SB RP-C18 column protected by a guard column containing the same packing. The mobile phase was a gradient prepared from 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid in HPLC-grade water (component A) and methanol (component B). Before use, the components were filtered through 0.45-µm nylon filters (Millipore). The flow rate was 1 mL min−1. Data were integrated by Shimadzu class VP series software and results were obtained by comparison with standards.

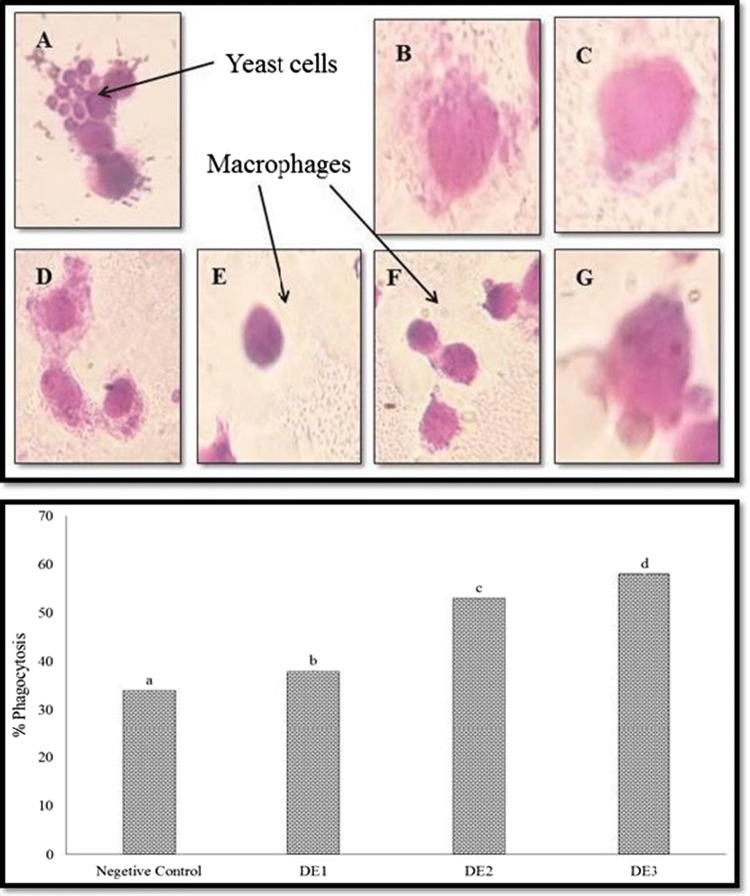

Phagocytic activity evaluation using mouse model

Macrophages were collected from the peritoneal fluid of healthy Swiss female albino mice (Small animal house, NDRI, Karnal) under hygienic conditions. For this ethical approval was granted by Institutional Ethical Animal Committee (IEAC), NDRI, Karnal for the study and CPCSEA guidelines were followed for handling the animals and performing different experiments as per IEAC recommendations. For this, animals were dissected by cervical dislocation and the abdominal skin was swabbed with alcohol (70%). The skin was carefully removed, leaving the peritoneum intact. To collect peritoneal fluid, 10 mL of Delbacco Modified Eagle Medium-Ham F12 (DMEM-F12) was injected into peritoneal cavity using 26G needle followed by gentle massaging of the abdomen. Peritoneal exudate (approximately 5 mL) was collected with 22G needle and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Phagocytosis was carried out according to the method of Hay and Westwood (2002). Briefly, cell pellets were dissolved in 1 mL DMEM-F12 medium and transferred into culture dish (35 mm) for incubation in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37 °C for 2 h to allow attachment of adherent cells. Non-adherent cells were removed by decantation. The adherent cells were washed two times with DMEM-F12 medium. The samples of DE in different concentrations (2, 5 and 10 µL) were then added to culture dish. DE samples devoid of EEO were treated as control in this experiment. The macrophages were incubated with yeast cells (108 cells/mL) for 1 h in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The medium was removed and the cells were washed twice gently with culture medium and incubated with 1 mL of tannic acid (1%) for one min at room temperature. The cells were again washed with culture medium, dried in air, and then stained for 5 min with May-Grunwald’s eosin methylene blue modified stain, freshly diluted with Giemsa buffer (1:2) and then again with Geimsa Solution (freshly diluted with buffer) for 15 min. The extra stain was removed by washing the cells with Giemsa buffer. The phagocytosis was observed at 1000× magnification under oil immersion and calculated by the formula as follows:

Statistical analysis

Experiments were carried out in duplicate/triplicate and values were expressed as mean ± SD. The results were analysed by one/two way ANOVA. IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software was used to determine the statistical significance among groups. Significant difference was accepted at p < 0.05.

Result and discussion

Controlled release of EEO during simulated digestion

In order to harness physiological benefits of EEO through maximum bioaccessibility, it’s release at the target site (intestine) is necessary for its maximum absorption and desirable effects. In the current investigation, the ability of developed DE matrix to protect EEO during harsh gastrointestinal digestion was studied. Initially digestion of DE starts from salivary digestion by various digestive enzymes (salivary amylase) and it experiences series of physicochemical and physiological changes in pH, ionic strength, and temperature. It was found that 7.83 ± 1.81% of EEO (measured as % total polyphenol) was released during the salivary digestion after 5 min incubation period (Fig. 1a). There was non-significant difference in release rate (p > 0.05) during salivary digestion, indicated a little change in the droplet size because the simulated oral fluid used in study did not contain significant amounts of surface active components that could displace or digest the outer phase emulsifier. The pH of saliva is around 5.5–7, and strongly negative charged emulsion did not flocculate as compared to weakly charged DE. ZP of EEO encapsulated DE was − 32.17 ± 1.17 mV and pectin present in outer phase of DE has negative charge, that does not leads to flocculation of DE during salivary digestion. But during simulated gastric digestion 14.95 ± 0.77% of total polyphenols were released from the DE after 1 h of incubation, proved that emulsion underwent some structural changes due to low pH (1–3) and action of enzyme gastric lipase. When digested EEODE was examined for ZP (supplementary Fig. S2) and particle size distribution (Fig. 2), decreased in ZP and slightly increased in droplet size was observed that attributed towards the flocculation due to coalescence of droplet. As digestion progressed, release rate of EEO increased and 65.00 ± 1.03% of total polyphenols release was noted after 2 h incubation during the intestinal digestion. The reason for this release of active component during enzymatic digestion was the structural changes of emulsion and release of inner water droplets to the exterior aqueous phase. This may be due to diffusion or coalescence of inner aqueous phase droplets leading to emulsion destabilization (Benichou et al. 2004; Appelqvist et al. 2007). Results of the current study indicated that release rate depend on the structural changes in DE due to action of gastric enzymes as confirmed by particle size distribution and ZP. Original DE exhibit strong negative charge indicated its stability due to electrostatic repulsion. During salivary digestion there is no significant change in ZP (− 29.72 mV), as pH of salivary digesta was around 6.6–6.8 and pectin in outer phase exhibit negative charge. But pH of gastric digestion reduced to 2 that ultimately decreased ZP (− 10.48 mV) resulting from damage of outer layer by digestive enzyme. This indicated that peptic enzyme could hydrolyse the outer layer of DE slightly, as pectin provide a steric barrier and does not allow peptic enzyme to act on the interfacial surface. This leads to aggregation of droplets but not to the higher extract. As digestion progressed ZP (− 58.93 mV) was increased more than undigested DE due to change in pH and ionic strength of solution, as well as due to adsorption of charged particles from the digestive juices onto the emulsifier coating.

Fig. 1.

Release and bioactive properties of E. officinalis extract (encapsulated and free forms) during in vitro digestion a Release of polyphenols. b ABTS and DPPH activity of digested mixture. c FRAP activity of digested mixture. d ACE inhibitory activity of digested mixture (Control EEODE not subjected to digestion; SSD simulated salivary digestion, SGD simulated gastric digestion, SID simulated intestinal digestion; DPPH 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, ABTS 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) ammonium salt, ACE angiotensin converting enzyme). Note: All the values given were Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3); a, b, c, d, e—Means with different superscripts differ significantly (p < 0.05); A, B, C, D, E—Means with different superscript differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

Particle size analysis of EEODE during various digestion phases. (Control EEODE not subjected to digestion, SSD simulated salivary digestion, SGD simulated gastric digestion, Sid Simulated intestinal digestion)

The PSD reveals that initially 50% of population lies below the size [Dv(50)] of 61.40 µm, but during salivary digestion there was no significant change observed in the PSD. However, in gastric digestion Dv(50) size increased up to 102.72 µm, that could be the reason for the release of polyphenol during this stage. On further examination of intestinal digesta, droplets size tremendously increased to 474.11 µm, probably due to aggregation of DE droplets. DE experiences loss of small droplets in alkaline environment due to the action of pancreatic/lipase enzyme and incorporation of lipid digestion products within the mixed micelles. Action of these enzymes results in loss of small droplet due to aggregation and displaces the emulsifier from the continuous phase also confirm by confocal microscopy images (Supplementary Fig. S3). Prolonged incubation time, hydrolysis of oil phase and inner water phase could also be attributed to this type of observation. Andrade et al. (2018) advocated that factors such as chemical composition of artificial digestive fluid; type of encapsulation method, wall material or physicochemical properties of inner aqueous phase affect the release rate of encapsulant. During the digestion of control sample highest amount of polyphenols were determined in salivary digesta (52.37 ± 5.75%) and least amount of polyphenols were detected in intestinal digesta, because EEO was not encapsulate in DE in control sample. This results are in agreement with the studies reported that increase of droplet size during digestion was due to aggregation and maximum release rate was observed in intestinal digesta (Xu et al. 2018; Kaimainen et al. 2015).

As stated above, structural changes undergone by polyphenols during digestion depends on the composition of the digestion mixture. Digestion is complex processes that involve action of enzymes such as amylase, lipase, protease, bile salts and particular pH conditions. All these factors effect molecular size, basic structure, degree of polymerization or glycosylation, solubility and conjugation behaviour of polyphenols which in turn govern the bioaccessibility of functional ingredients to produce desirable health effects. Since, no protective coating is given to control sample, during salivary digestion most of the hydrolysable polyphenol released into the medium and hence detected in the assay. However, during the phase of gastric and intestinal digestion polyphenols from control sample might have undergone structural changes due to chemical reaction and thus lesser amount was detected in the assay. Gao and Hu (2010) reported that harsh environment of gastrointestinal tract could impede the decomposition of phenolics due to varied pH conditions that effects the stability of different polyphenols differently. Large molecular weight polyphenols are unstable in the intestinal digestion due to alkaline conditions moreover their bioaccessibility is reduced due to iso-transformation of polyphenols by the gut microflora (Jiao et al. 2018). These results indicated that the DE matrix employed provided a protective coating to EEO during simulated digestion process and helped in sustained and targeted release at target site. Several studies indeed report an increase of the droplet size during the digestion, usually due to aggregation of the droplets (Frank et al. 2012; Xiao et al. 2017), but the extent depend on type and amount of the emulsifier used or the initial droplet size of the emulsion.

Gallic acid was also estimated in the digested mixture at different stages by HPLC (Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table 3). The standard gallic acid and blank was also run before the analysis. After intestinal digestion, 0.72 mg/mL of gallic acid was detected in the digesta of EEODE measure using HPLC, while in saliva and gastric digestion mixtures it was not detected. It is evident from these results that the release rate of gallic acid from DE was maximum in the intestine. However, in control sample, maximum gallic acid was found in salivary digesta (0.74 mg/mL) and least amount in intestinal digesta. These results again indicated that DE effectively protected the bioactives release during harsh digestion process and facilitated release at target site i.e. intestine. Non-encapsulated EEO might have degraded during its passage through digestion process; hence, least amount of gallic acid was detected in intestinal digesta of control sample. This decrease was mainly due to instability of phenolics at high pH under the intestinal environment (Soriano Sancho et al. 2014). Polyphenol profile of E. officinalis has a great structural diversity. Saura-calixto et al. (2007) demonstrate that pH and digestive enzymes action are most important factors affecting the hydrolysis of tannin (polyphenols) in the gut.

Table 3.

Detail observation of HPLC

| Digestion stage | Sample | RT (min) | Compound name | Area | Height | Concentration (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated salivary digestion | Control | 7.097 | Gallic acid | 9209.05 | 1190.11 | 0.7385 |

| Double emulsion | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Simulated gastric digestion | Control | 7.187 | Gallic acid | 5671.60 | 731.06 | 0.4085 |

| Double emulsion | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Simulated intestinal digestion | Control | 7.039 | Gallic acid | 114.81 | 9.94 | 0.0096 |

| Double emulsion | 7.085 | Gallic acid | 9856.75 | 1238.1 | 0.7211 |

Antioxidant and ACE inhibitory activity

Antioxidant activity of the digested mixture was estimated to evaluate the fate of bioactive molecules after each step of digestion. It was observed that DE successfully protected the antioxidant activities of E. officinalis in the simulated gastro-intestinal environment (Fig. 1b, c). The antioxidant activity of salivary digesta of EEODE as indicated by ABTS (mM/mL), DPPH (µM/mL) and FRAP (mM/mL) values of 9.40 ± 0.78, 0.66 ± 0.23 and 0.63 ± 0.00, respectively was least when compared to its gastric and intestinal counterparts. The respective values during the simulated gastric digestion were 36.96 ± 0.20, 41.88 ± 0.23 and 2.81 ± 0.28 and during intestinal digestion were 99.58 ± 7.24, 76.93 ± 0.93 and 6.34 ± 0.13, respectively. These results indicated that maximum antioxidant molecules were released during intestinal digestion. As EEO was encapsulated in inner phase of DE and emulsion remain intact during the salivary digestion but start releasing some of the polyphenols into the gastric and most of the phenolic in the intestinal digestion. These results are in agreement with the polyphenols release from EEODE reported in the previous section. Chiang et al. (2012) reported that a strong positive correlation exists between the total polyphenol and antioxidant activity of plant extracts. In another study, Tazliazucchi et al. (2010) reported that antioxidant activity increased during the intestinal digestion of grape polyphenols. The workers attributed this to deprotonation of the hydroxyl moieties of the phenolic compounds thus led to higher antioxidant activity. It must be highlighted that despite of highly surface active enzymes, salt and varied pH conditions, EEODE proved to be an efficient medium for the delivering of E. officinalis polyphenols that enhance the antioxidant activity in the intestinal digesta. This may be due to the improved protection offered by double emulsification process to the phenolics.

This trend was reverse for control sample, where maximum antioxidant activity was observed after simulated salivary digestion i.e. 122.29 ± 0.59 mM/mL (ABTS), 74.96 ± 1.39 µM/mL (DPPH) and 7.18 ± 1.39 mM/mL (FRAP), respectively. The antioxidant activity of the control sample decreased after gastric digestion when compared to salivary digestion and was least after intestinal digestion. It can be interpreted that antioxidant activity of EEO decreased due to lack of suitable protective matrix during digestion process. The reason for decrease in antioxidant activity in non-encapsulated EEO may be due to the interaction of polyphenols with gastric enzymes that leads to the formation of protein-polyphenols complex and reduces their bioaccessibility while such type of interaction is inhibited in the encapsulated sample (Betz et al. 2012). Also, presence of oil and emulsifiers in encapsulation matrix might have influenced the antioxidant capacity by affecting the partition coefficient of antioxidants between water and oil phase (Uekusa et al. 2008). The current observations were in agreement with those of Green et al. (2007), who observed that stability of DE increased due to emulsifiers used in the middle and outer phase. Emulsifiers might have protected the coating matrix/carrier from degradation in the acidic environment as well as from the action of pepsin during digestion process (van Aken et al. 2011).

ACE inhibitory activity of EEODE and control samples followed a similar trend as in the case of antioxidant activity. For EEODE, maximum ACE inhibitory activity was observed in the intestinal digesta (62.19 ± 0.00%), whereas for control, the maximum activity was in the salivary digesta (22.66 ± 3.31%) (Fig. 1d). These observations confirmed that the DE structure was intact during the salivary digestion, resulting in minimum release of active contents and hence lower ACE inhibitory activity. During gastric digestion DE underwent structural extension and some droplets might have collapsed due to enzymatic action, leading to release of inner aqueous phase. It was evident by increased ACE inhibitory activity that the majority of inner aqueous droplets collapsed during the intestinal digestion and leached into the outer aqueous resulted in maximum ACE inhibitory activity of digested samples.

In vitro phagocytosis activity

Phagocytosis is the internalization of pathogens by macrophages which is the first step of defence against infection. Macrophages recognize invading foreign bodies and this immune system is central to cell mediated and humoral immunity, as there no antibodies involved (Cavaillon 1994). Activation of phagocytosis results in enhancement of the innate immune response that strengthens the immunostimulatory potential and infection fighting properties (Li et al. 2005). The results obtained in our study indicated that phagocytic activity of mice macrophages increased after being treated with EEODE (Fig. 3). Changes were observed in the phagocytosis activity when the concentration of EEODE was varied (2–10 µL). At the lowest concentration used in the study i.e. 2 µL, EEODE did not shown any significant (p > 0.05) difference in phagocytic activity when compared to negative control. Phagocytic activity increased significantly (p < 0.05) with increase in concentration of EEODE (5 µL and 10 µL). Figure 3 shows the initiation of phagocytosis i.e. small yeast cells attached to the surface of macrophages and engulfment of yeast cells by macrophages. Clear zone observed in Fig. 3f indicated the complete engulfment of yeast cells. These results are in agreement with the findings of Madaan et al. (2015) who observed significant increase in phagocytosis in dose dependent manner when Dabur Chyawanprash (an Ayurvedic preparation containing 90% E. officinalis) was added to mouse cell lines at concentration of 0.1–500 µg/mL. After 24 h of treatment with Chyawanprash, engulfment of pre-labeled zymosan particles, resulting in enhanced clearance of pathogens in body. Results indicated that EEODE has a immense potential to fight against common infections with the help of macrophages.

Fig. 3.

Engulfment of yeast cells by macrophages during phagocytosis process (above) (A—Negative control; B and C—samples added with 2 µL EEODE; D and E—samples added with 5 µL EEODE, F and G—samples added with 10 µL EEODE); Phagocytosis index of the control and encapsulated samples (DE1—samples added with 2 µL EEODE, DE2—samples added with 5 µL EEODE; DE3—samples added with 10 µL EEODE). Note: All the values given were Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3); a, b, c, d—Means with different superscript within the bars differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Conclusion

Results obtained in current study indicated that DE protected the activity of EEO during harsh digestion conditions and facilitated sustained and targeted delivery. Phagocytosis activity confirmed the immunomodulatory property of EEO encapsulated in the DE. Thus EEODE can be used as functional ingredient and incorporated into different dairy and food products. However, research on absorption of released bioactive molecules in intestine and their toxicity is essential to establish the beneficial effects of encapsulation. Also, physiological benefits of EEODE and its control sample should be validated through animal and clinical studies to realize beneficial effects of encapsulation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the research Grant (MoFPI/SERB/057/2015) provided by Science and Engineering Research Board, Ministry of Food Processing Industries, Government of India to conduct this research. Also, first author is thankful to Director, ICAR-NDRI for providing Senior Research Fellowship and necessary facilities to carry out this work.

Abbreviations

- EEO

Emblicanin rich water soluble extract of Emblica officinalis

- DE

Double emulsion

- EEODE

Emblicanin rich water soluble extract of Emblica officinalis encapsulated double emulsion

- ACE

Angiotensin converting enzyme

- W1

Inner aqueous phase

- W1/O

Water-in-oil

- W2

Outer aqueous phase

- PGPR

Polyglycerolpolyricinoleate

- DPPH

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- ABTS

2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) ammonium salt

- TPTZ

2,4,6-Tripyridyl triazine

- Trolox

Ammoinum iron (II) sulphate hexahydrate, 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid

- HHL

Hippuryl-His-Leu acetate salt

- HA

Analytical grade hippuric acid

- BSC

Benzene sulfonyl chloride

- ZP

Zeta potential

- PSD

Particle size distribution

- DMEM

Delbacco modified Eagle medium-Ham

- SSD

Simulated salivary digestion

- SGD

Simulated gastric digestion

- SID

Simulated intestinal digestion

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Neha Chaudhary, Email: gemini.nehachaudhary@gmail.com.

Latha Sabikhi, Email: lsabikhi@gmail.com.

Shaik Abdul Hussain, Email: abdulndri2006@gmail.com.

References

- Actis-Goretta L, Ottaviani JI, Fraga CG. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme activity by flavanol-rich foods. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(1):229–234. doi: 10.1021/jf052263o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aditya NP, Aditya S, Yand H, Kim HW, Park SO, Ko S. Co-delivery of hydrophobic curcumin and hydrophilic catechin by a water-in-oil-in-water double emulsion. Food Chem. 2015;173:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade J, Wright AJ, Corredig M. In vitro digestion behavior of water-in-oil-in-water emulsions with gelled oil-water inner phases. Food Res Int. 2018;105:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelqvist IAM, Golding M, Vreeker R, Zuidam NJ. Emulsions as delivery systems in foods. In: Lakkis JM, editor. Encapsulation and controlled release technologies in food systems. Iowa: Blackwell Publishing Professional; 2007. pp. 41–81. [Google Scholar]

- Benichou A, Aserin A, Garti N. Double emulsions stabilized with hybrids of natural polymers for entrapment and slow release of active matters. Adv Colloid Int Sci. 2004;108:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz M, Steiner B, Schantz M, Oidtmann J, Mäder K, Richling E, Kulozik U. Antioxidant capacity of bilberry extract microencapsulated in whey protein hydrogels. Food Res Int. 2012;47(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaillon JM. Cytokines and macrophages. Biomed Pharmacol J. 1994;48:445–453. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N (2017) Evaluation of dairy protein based double emulsion for the encapsulation of cardioprotective herbal extract. Ph.D. in Dairy technology thesis submitted to the ICAR-National dairy research institute, Karnal, Haryana, India

- Chiang CJ, Kadouh H, Zhou K. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of gooseberry as affected by invitro digestion. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2012;51:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman DW, Cheung HS. Spectrophotometric assay and properties of the angiotensin-converting enzyme of rabbit lung. Biochem Pharmacol J. 1971;20(7):1637–1648. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(71)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank K, Walz E, Graf V, Greiner R, Kohler K, Schuchmann HP. Stability of anthocyanin-rich W/O/W emulsions designed for intestinal release in gastrointestinal environment. J Food Sci. 2012;77(12):51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Hu M. Bioavailability challenges associated with development of anticancer phenolics. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2010;10(6):550–567. doi: 10.2174/138955710791384081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RJ, Murphy AS, Schulz B, Watkins BA, Ferruzzi MG. Common tea formulations modulate in vitro digestive recovery of green tea catechins. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(9):1152–1162. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay FC, Westwood OMR (2002) Phagocytosis, complement and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity, 4th Edn. In: Practical immunology. Blackwell Science, London, pp 203–206

- Herrero-Barbudo MC, Granado-Lorencio F, Blanco-Navarro I, Perez-Sarcristan B, Olmedilla-Alonso B. Applicability of an in vitro model to assess the bioaccessibility of vitamin A and E from fortified commercial milk. Int Dairy J. 2009;19(1):64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2008.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X, Li B, Zhang Q, Gao N, Zhang X, Meng X. Effect of in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion on the stability and antioxidant activity of blueberry polyphenols and their cellular antioxidant activity towards HepG2 cells. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2018;53:61–71. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaimainen M, Marze S, Järvenpää E, Anton M, Huopalahti R. Encapsulation of betalain into w/o/w double emulsion and release during in vitro intestinal lipid digestion. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2015;60:899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koczka N, Banyai ES, Ombodi A. Total polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity of rosehips of some Rosa species. Medicines (Basel) 2018;5(3):84. doi: 10.3390/medicines5030084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AD (2011) Evaluation of selected matrix material for developing emulsion based delivery system for Pueraria tuberose/Vidarikand extract. M.Tech. thesis in Dairy Technology submitted to ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute (Deemed University), Karnal, Haryana, India

- Li Y, Qu X, Yang H, Kang L, Xu Y, Bai B, Song W. Bifidobacteria DNA induces murine macrophages activation in vitro. Cell Mol Immunol. 2005;6:473–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madaan A, Kanjilal S, Gupta A, Sastry JLN, Verma R, Singh AT, Jaggi M. Evaluation of immunostimulatory activity of Chyawanprash using in vitro assays. Indian J Exp Biol. 2015;53:158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandarika J, Krishna NR, Saidule C. Effect of Emblica officinalis fruit extraction gluconeogenesis in Allaxon induced diabetic mice. J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 2014;6(4):921–924. [Google Scholar]

- Matos M, Gutiérrez G, Coca J, Pazos C. Preparation of water-in-oil-in-water (W1/O/W2) double emulsions containing resveratrol. Colloids Surf A. 2014;442:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.05.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Middha SK, Goyal AK, Lokesh P, Yardi V, Mojamdar L, Keni DS, Babu D, Usha T. Toxicological evaluation of Emblica officinalis fruit extract and its antiinflammatroy and free radical scavenging properties. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11:S427–S433. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.168982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomen AG, Hack A, Minekus M, Zeijdner E, Cornelis C, Schoeters G, Verstraete W, Van de Wiele T, Wragg J, Rompelberg CJ, Sips AJ. Comparison of five in vitro digestion models to study the bioaccessibility of soil contaminants. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36(15):3326–3334. doi: 10.1021/es010204v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajak S, Banerjee SK, Sood S, Dinda AK, Gupta YK, Gupta SK, Maulik SK. Emblica officinalis causes myocardial adaptation and protects against oxidative stress in ischemic-reperfusion injury in rats. Phytother Res. 2004;18(1):54–60. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao TP, Sakaguchi N, Juneja LR, Wado E, Yokozaroa T. Amla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn.) extracts reduced oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Med Food. 2005;8:362–368. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura-Calixto F, Serrano J, Goni I. Intake and bioaccessibility of total polyphenols in a whole diet. Food Chem. 2007;101:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaddel R, Hesari J, Azadmard-Damirchi S, Hamishehkar H, Fathi-Achachlouei B, Huang Q. Double emulsion followed by complex coacervation as a promising method for protection of black raspberry anthocyanins. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;77:803–816. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano Sancho RA, Pavan V, Pastor GM. Effect of in vitro digestion on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of common bean seed coats. Food Res Int. 2014;76:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.11.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tazliazucchi D, Verzelloni E, Bertolini D, Conte A. Invitro bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity of grape polyphenols. Food Chem. 2010;120:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.10.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uekusa Y, Takeshita Y, Ishii T, Nakayama T. Partition coefficients of polyphenols for phosphatidylcholine investigated by HPLC with an immobilized artificial membrane column. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:3289–3292. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Aken GA, Bomhof E, Zoet FD, Verbeek M, Oosterveld A. Differences in in vitro gastric behaviour between homogenized milk and emulsions stabilised by Tween 80, whey protein, or whey protein and caseinate. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25(4):781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Lu X, Huang Q. Double emulsion derived from kafirin nanoparticles stabilized Pickering emulsion: fabrication, microstructure, stability and in vitro digestion profile. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;62:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Yang Y, Xue SJ, Shi J, Lim LT, Forney C, Xu G, Bamba SB. Effect of In-vitro digestion on water in oil in water emulsions containing anthocyanin from grape skin powder. Molecules. 2018;23:2808. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.