Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) show potential for treating cardiovascular diseases, but their therapeutic efficacy exhibits significant heterogeneity depending on the tissue of origin. This study sought to identify an optimal source of MSCs for cardiovascular disease therapy. We demonstrated that Nestin was a suitable marker for cardiac MSCs (Nes+cMSCs), which were identified by their self-renewal ability, tri-lineage differentiation potential, and expression of MSC markers. Furthermore, compared with bone marrow-derived MSCs (Nes+bmMSCs) or saline-treated myocardial infarction (MI) controls, intramyocardial injection of Nes+cMSCs significantly improved cardiac function and decreased infarct size after acute MI (AMI) through paracrine actions, rather than transdifferentiation into cardiac cells in infarcted heart. We further revealed that Nes+cMSC treatment notably reduced pan-macrophage infiltration while inducing macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype in ischemic myocardium. Interestingly, Periostin, which was highly expressed in Nes+cMSCs, could promote the polarization of M2-subtype macrophages, and knockdown or neutralization of Periostin remarkably reduced the therapeutic effects of Nes+cMSCs by decreasing M2 macrophages at lesion sites. Thus, the present work systemically shows that Nes+cMSCs have greater efficacy than do Nes+bmMSCs for cardiac healing after AMI, and that this occurs at least partly through Periostin-mediated M2 macrophage polarization.

Keywords: mesenchymal stromal cells, myocardial infarction, immunomodulation, Periostin, macrophage polarization

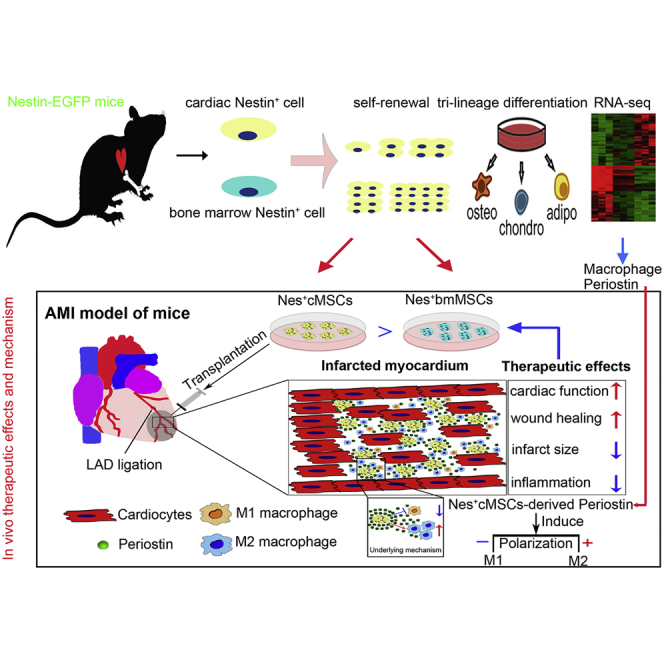

Graphical Abstract

The therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) shows significant heterogeneity depending on their tissue of origin. Liao and colleagues identify that Nestin+ cardiac MSCs have shown greater efficacy than Nestin+ bone marrow MSCs for cardiac healing post-acute myocardial infarction. This is partially caused by Nestin+ cMSCs-secreted Periostin inducing the macrophage polarization towards the anti-inflammatory M2 subtype.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide.1,2 The increasing prevalence and high mortality of heart disease means that it is critical that we continue to search for innovative treatments. Stem cell-based therapy is a rapidly growing alternative for regenerating the damaged myocardium and attenuating ischemic heart disease.3 However, the optimal source of cells for tissue repair of the human heart remains controversial. Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have shown therapeutic potency for treating CVDs and offer the benefits of easy isolation and expansion, homing potential, paracrine effects, and immunomodulatory activities.4 Preclinical and clinical data from animal models and humans have demonstrated that MSC therapy is safe for treating CVD,5, 6, 7, 8 but there is significant heterogeneity in terms of therapeutic efficacy.6,9,10 Therefore, we need to identify the best source of stem cells for cardioreparative therapy. A major hypothesis in the field of cell-based therapy is that different cell types from different tissue origins may have additive effects on tissue repair. Although originally identified in bone marrow,11 MSCs are broadly distributed in the perivascular niche of many organs, including the kidney, lung, tendon, and heart.12, 13, 14, 15 Tissue-resident MSCs are usually localized in a specific tissue microenvironment, where they are thought to help maintain tissue homeostasis.16 There are many similarities between bone marrow MSCs and MSC-like populations from other locations, but their absolute phenotypic and functional equivalence has not yet been established. Indeed, accumulating evidence suggests that tissue-resident MSCs are more suitable for their original tissue repair.17,18 Thus, it is interesting to question whether cardiac-resident MSCs (cMSCs) may offer distinct advantages over non-resident MSCs for the therapy of CVDs.

cMSCs are usually isolated via adhesion to plastic and characterized using a panel of cell surface markers and assessment of their osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation abilities.5,17,19 This yields a heterogeneous ensemble of progenitors and lineage-committed cells. Thus, we urgently need reliable and specific markers that may be used to characterize and define the biological characteristics of cMSCs and their subpopulations in vitro, and to study their identity and functions in vivo. Chong et al.20 characterized a population of multipotent MSC-like cells that reside in the heart and have a proepicardial origin.20 More recently, a subfamily of W8B2 antigen-positive cells obtained from adult human atrial appendages was shown to have MSC properties and secrete a variety of angiogenic, inflammatory, and chemotaxic cytokines.21 Although their gene and protein expression profiles suggest that these isolated cMSC subpopulations may have cardiovascular-associated features,19 no study has directly investigated whether cMSCs have more superior therapeutic potential than do bone marrow-derived MSCs (bmMSCs) for cardiac repair. Moreover, due to the lack of an accepted panel of markers for in vivo use, the exact nature and functions of cardiac-resident and non-resident MSCs remain poorly understood. Therefore, we need new and consistent ways to identify and functionally characterize pure populations of naive cMSCs.

Nestin is a class VI intermediate filament protein that was originally described in neural stem or progenitor cells during embryonic development.22 Nestin is also expressed in MSCs of various tissues, including bone marrow, kidney, testis, and tendon,15,23, 24, 25 suggesting that it could be used as a specific marker for isolating tissue-resident MSCs. Subpopulations of cardiac Nestin+ cells were previously identified and found to possess the intrinsic ability to differentiate to vascular,26 neuronal,27 or glial28 cells in both the normal developing myocardium and infarcted heart, indicating that they have stem cell characteristics.

In the present study, we demonstrate that Nestin can be used as a marker for identifying cardiac-resident MSCs, and show that Nes+cMSCs are more effective than Nes+bmMSCs for cardiac repair following acute myocardial infarction (AMI) through the paracrine action. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data and in vivo functional comparisons of efficacy and biological activity further reveal that Nes+cMSCs perform their reparative functions at least partly through the Periostin-mediated polarization of macrophages to the M2 subtype.

Results

Isolation and Characterization of Nestin+ Cells from the Heart and Bone Marrow of Transgenic Mice

The identity and functions of Nestin+ cells in bone marrow have been clearly defined.23,29,30 In this study, we focused on characterizing Nestin+ cells in the heart, where Nestin is expressed under both normal and pathological conditions.26,28 Using confocal microscopy, we systemically evaluated Nestin and GFP expression in the hearts of Nestin-GFP transgenic mice at different postnatal days. Consistent with previous findings,31 we observed GFP signal in the left/right ventricle and interventricular septum of the heart at postnatal days 1, 7, 30, and 90, with much higher expression noted on postnatal days 1 and 7 compared to days 30 and 90 (Figure S1A). Analysis of the mRNA expression levels of Nestin in whole mouse hearts confirmed these histological observations: the mRNA level of Nestin peaked at postnatal days 1 and 7, fell to less than 50% of the peak level by day 30, and was less than 25% of the peak level by day 90 (Figure S1B). We also examined the co-expression of Nestin and GFP in the mouse heart by immunofluorescence (IF) staining and found that GFP was largely co-localized with Nestin, which was stained by a specific antibody (Figure S1C). This indicates that GFP can serve as a surrogate for Nestin in our system.

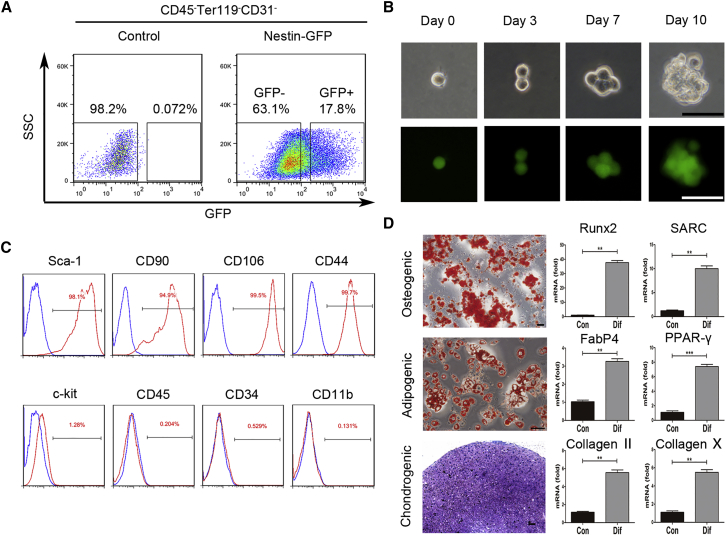

We isolated cardiac Nestin-GFP+ cells from 7-day-old mouse hearts using flow cytometric sorting. The CD45−Ter119−CD31−-gated population was approximately 16.90% ± 1.64% GFP-positive (CD45−Ter119−CD31− Nestin+) and 68.60% ± 5.96% GFP-negative (CD45−Ter119−CD31− Nestin−) (Figure 1A). After a 10-day culture in vitro, the isolated primary heart-derived Nestin+ cells yielded many clonal spheres, whereas the Nestin− cells did not, demonstrating that Nestin+ cells, but not Nestin− cells, have a strong proliferative capacity in vitro. In contrast, Nestin− cells did not proliferate for more than two passages and could not form floating spheres. Therefore, we focused on Nestin+ cells, investigating their characteristics in vitro and their therapeutic effects in vivo. Freshly isolated single Nestin+ cells subjected to a 10-day culture in 96-well plates could grow into suspended cell spheres that maintained their GFP fluorescence (Figure 1B), confirming the self-renewal capacity of the isolated cardiac Nestin+ cells. The isolated GFP+ cells co-expressed Nestin and GFP continuously, as identified by qPCR, IF staining, and western blotting with an anti-Nestin antibody (Figures S1D–S1F). After passage (P) 20, Nestin expression was gradually downregulated, with a concurrent decrease in GFP expression. Nestin has been used to label populations of stem/progenitor cells, such as self-renewing MSCs in bone marrow23,32 and tissue-resident MSCs in kidney.25 To confirm that cardiac Nestin+ cells represented cMSCs, we used flow cytometry to analyze the other MSC-related surface markers. As expected, the isolated cells were positive for Sca-1 (97.60% ± 1.82%), CD90 (95.33% ± 2.68%), CD106 (99.44% ± 0.38%), and CD44 (99.5% ± 0.34%), but almost negative for c-kit (1.32% ± 0.65%), CD45 (0.25% ± 0.12%), CD34 (0.44% ± 0.21%), and CD11b (0.28% ± 0.18%) (Figure 1C). Moreover, cardiac Nestin+ cells subjected to the relevant differentiation conditions for 2–3 weeks could differentiate into osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes, as identified by Alizarin red, Oil red O, and Toluidine blue staining, respectively (Figure 1D). The qPCR analysis further confirmed that the differentiated cells showed the appropriate expressions of Runx2 and SARC (osteogenesis-related genes), FabP4 and PPAR-γ (adipogenesis-related genes), or Collagen II and Collagen X (chondrogenesis-related genes) after differentiation culture, but not prior to differentiation (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Isolation and Characterization of Heart-Resident Nestin+ Cells from Nestin-GFP Reporter Mice

(A) Heart-derived CD45−Ter119−CD31− cells were flow cytometrically isolated from the hearts of 7-day-old Nestin-GFP transgenic mice, and Nestin+ and Nestin− subpopulations were divided based on GFP expression. Cells from 7-day-old non-transgenic C57BL/6 mice were isolated as a control. (B) Representative images showing the clonal sphere growth of single Nestin-GFP+ cells. Cells in the upper and lower columns were observed under bright-field and fluorescence field microscopy, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C) The expressions of cell surface markers on Nestin-GFP+ cells were detected by flow cytometry. (D) Representative stained images show that mouse heart-derived Nestin+ cells could differentiate into osteocytes (Alizarin red), adipocytes (Oil red O), and chondrocytes (toluidine blue); these findings were confirmed by qPCR analysis of the differentiation-associated genes Runx2 and SARC (osteogenesis), FabP4 and PPAR-γ (adipogenesis), and Collagen II and Collagen X (chondrogenesis). The “con” refers to undifferentiated Nestin+ cells, which represents Nestin+ cells that were cultured in the normal growth medium. Scale bars, 100 μm. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 5. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To compare the therapeutic potential of heart- and bone marrow-derived Nestin+ cells against AMI, we also isolated Nestin+ cells from the bone marrow of 7-day-old mice by flow cytometric sorting. The CD45−Ter119−CD31−-gated population comprised approximately 4.10% ± 0.45% GFP-positive cells (CD45−Ter119−CD31− Nestin+) (Figure S2A). The bone marrow Nestin+ cells also exhibited self-renewal capacity, had tri-lineage differentiation potential, and showed similar patterns of cell surface markers, positive for Sca-1 (92.10% ± 2.54%), CD90 (90.67% ± 3.48%), CD106 (87.79% ± 1.66%), and CD44 (99.58% ± 0.70%), but negative for c-kit (1.58% ± 0.35%), CD45 (1.85% ± 0.18%), CD34 (2.11% ± 0.96%), and CD11b (2.11% ± 0.15%) (Figures S2B–S2D). Similar to their cardiac counterparts, the primary bone marrow-derived Nestin+ cells, but not their Nestin− cells, yielded clonal spheres after a 10-day culture (Figure S2E), and bone marrow Nestin− cells could not propagate for more than two passages. The clonogenic efficiencies of these two type of Nestin+ cells at passage 2 were similar (21.3% ± 3.9% versus 19.4% ± 2.6%, p > 0.05), while no spheroid formation was detected from Nestin− cells (Figure S2F). Given the similarity in the MSC-like features of Nestin+ cells isolated from heart and bone marrow, we defined them as Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs, respectively.

Transcriptional Profiles of Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs

We compared the biological properties of the Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs by analyzing our RNA-seq data (Gene Expression Omnibus [GEO] database; GEO: GSE100064). Consistent with the results we obtained using flow cytometry, the two types of MSCs were similar in their expression levels of the MSC markers CD29, CD51, CD44, CD106, Sca-1, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα), differed with respect to their expression levels of the CD90, CD105, and CD166, and were negative for c-kit, CD45, CD31, and CD11b (Figure S3A). The Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs shared expression of 230 PluriNet genes (FPKM [fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads] > 1, approximately 77% of the dataset), and Pearson correlations of pairwise comparisons revealed that the r value was 0.941 (Figures S3B and S3C), indicating their stemness characteristics of the isolated cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that MSCs are very closely related with fibroblasts and pericytes in heart and bone marrow.33,34 Our RNA-seq data also showed that Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs consistently showed high-level expression of a suite of known fibroblast- and pericyte-related markers,35,36 such as fibroblast-related Col3a1, Col1a1, Col1a2, Vim, Flna, Ddr2, Pdgfra, and Thy1 (Figure S3D; the r value (Pearson correlation) is 0.816 [Figure S3E]), as well as pericyte-related Pdgfrb, Acta2, and Cspg4 (r = 0.840, Figures S3F and S3G). Our findings indicate that Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs share similar characteristics with fibroblasts and pericytes. In addition, some of above-mentioned fibroblast- and pericyte-related markers that were expressed by Nes+cMSCs were further verified by flow cytometry and IF staining (Figures S4A and S4B). Taken together, these results indicate that both Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs have shown the typical transcriptional characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells.

From the RNA-seq data, we found that Nes+cMSCs specifically expressed several cardiac transcription factors (TFs), including Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx2, and others (Figure S5A). To further confirm this observation, we detected cardiac TF expression at the protein level via western blot and IF staining. Compared to Nes+bmMSCs, Nes+cMSCs highly expressed Gata4, Mef2c and Tbx2 (Figures S5B and S5C). Taken together, Nes+cMSCs show cardiac-specific characteristics, indicating that cardiac-resident MSCs may offer distinct advantages over bone marrow MSCs for cardiac repair.

Nes+cMSCs Are More Effective Than Nes+bmMSCs for Cardiac Wound Healing following AMI

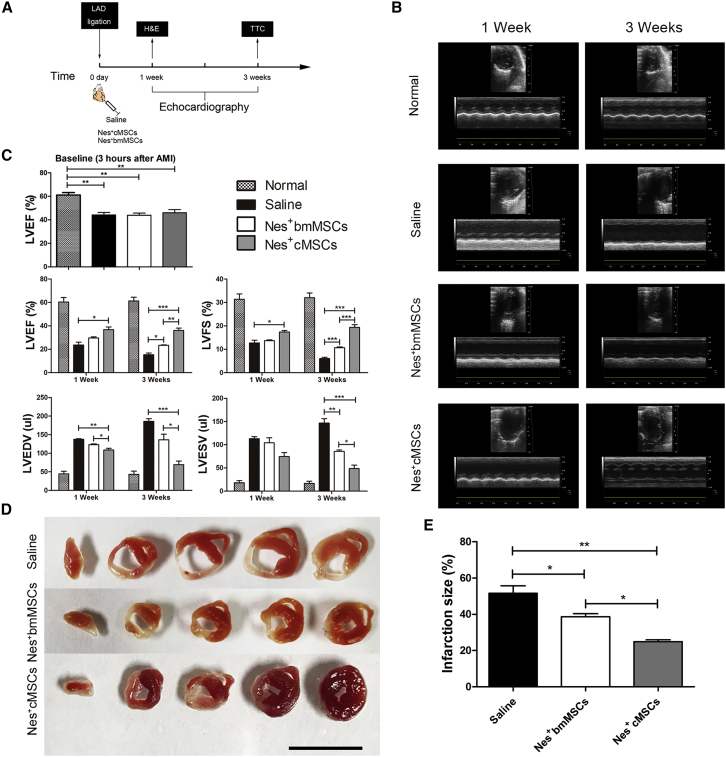

Intramyocardial injection of bone marrow-derived MSCs has been shown to be safe and effective in animal models, and preliminary clinical trials have demonstrated that such cells induce reverse remodeling and improve the regional contractility of scarred areas.6,37 In this study, we examined the therapeutic potential of Nes+cMSC implantation on cardiac repair after AMI. Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs were transplanted into the infarct border zone immediately after coronary artery occlusion injury in mice, and histological and echocardiographic analyses were performed at 1 and 3 weeks post-AMI (Figure 2A). Echocardiography indicated that the ligation of the coronary artery induced significant left ventricular dilatation and increased the left ventricular diameter at 1 and 3 weeks post-AMI in the saline group compared with the normal group, with the typical dilatation of the left ventricle seen at the latter time point. This dilatation of the left ventricle was significantly reduced in the Nes+bmMSC- and Nes+cMSC-treated groups, with increased improvement seen in the Nes+cMSCs group (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Therapeutic Effects of Nes+bmMSCs versus Nes+cMSCs on Myocardial Infarct Wound Healing and Cardiac Function

(A) Schematic of protocols used for model establishment and cardiac function analysis. At 0 day, the AMI model was generated by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. One minute later, the ischemic area was identified, and saline (vehicle-treated control) or Nestin+ cells (Nes+MSCs or Nes+cMSCs) were intramyocardially injected into the infarct border zone. Cardiac function, infarct degree, and inflammatory infiltration were analyzed by echocardiography, TTC staining, and H&E staining, respectively, at 1 and 3 weeks post-AMI. (B) Representative M-mode images from animals of the normal and AMI groups (treated with saline, Nes+bmMSCs, and Nes+cMSCs) at 1 and 3 weeks post-AMI. (C) Heart function was evaluated by echocardiography at 3 h (baseline), 1 week, and 3 weeks post-AMI, and LVEF, LVFS, LVEDV, and LVESV were measured. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 15–20 per group. (D) Five heart sections (1 mm thick) from each group were stained with 1% TTC for visualization of the infarct area (pale) and the viable myocardial area (brick red). Scale bar, 10 mm. (E) Comparison of the relative scar areas among the study groups. The ratio of the length of the infarct band to the total length of the LV was calculated. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 5. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume.

Our quantitative echocardiographic results (Figure 2C) showed that the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at baseline was indistinguishable among saline and different treatment groups 3 hours post-AMI, indicating a uniform degree of initial injury. At 3 weeks post-AMI, the LVEF and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS) of mice in the saline group were significantly reduced compared with those of the non-infarcted normal group (15.33% ± 2.05% versus 61.33% ± 4.50%, respectively, for LVEF; 6.00% ± 0.82% versus 32.00% ± 2.94%, respectively, for LVFS). Mice treated with Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs exhibited dramatic increases in LVEF (36.00% ± 2.94% and 23.33% ± 0.47%, respectively) and LVFS (19.33% ± 1.70% and 10.67% ± 0.47%, respectively) in comparison with the saline group. The left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) of mice in the two MSC-treated groups were clearly reduced at 3 weeks post-AMI, compared with the saline group. Importantly, the Nes+cMSCs group showed greater recoveries of LVEF, LVFS, LVEDV, and LVESV at 1 and 3 weeks post-AMI, compared to the Nes+bmMSCs group (Figure 2C).

Infarcted myocardium was identified using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining of heart sections obtained at 3 weeks post-AMI. Similar to the results of our echocardiographic analysis, we found that the infarct size was significantly smaller in the Nes+cMSCs group than in the saline group (24.87% ± 1.50% versus 51.58% ± 5.96%, respectively), and that this improvement was greater than that seen in the Nes+bmMSCs group (24.87% ± 1.50% versus 38.72% ± 2.35%, respectively; Figures 2D and 2E).

To further evaluate the translational potential of Nes+cMSCs toward a therapeutic paradigm, we tried to isolate these cells from 3-month-old adult mice. Compared with those of the 7-day-old mice, the percentages of GFP+ cells in CD45−Ter119−CD31− population were relatively lower (approximately 1.80% ± 0.12% in heart and 0.51% ± 0.13% in bone marrow, Figure S6A). These cells can proliferate continuously and show multipotency, similar to their neonatal counterparts (Figures S6B and S6C). The in vivo transplantation experiments demonstrated the adult Nes+cMSCs also significantly improved cardiac function and attenuated left ventricular remodeling at 3 weeks post-MI, compared with the adult Nes+bmMSC- or saline-treated MI controls (Figure S6D).

Taken together, these results suggest that Nes+cMSC treatment has greater potential than does Nes+bmMSC treatment for promoting heart function and reducing infarct size post-AMI.

Transplantation of Nes+cMSCs Suppresses the Inflammatory Response by Reducing the Number of Pan-Macrophages within the Ischemic Myocardium

For tracing the fate of the transplanted cells, Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding EF-1alpha promoter-driven RFP (red fluorescent protein), because Nestin expression was significantly downregulated, and along with that GFP expression also diminished after cell differentiation.23,38 Approximately 20% of the total RFP+ transplanted cells were located in the injured area at 1 week post-AMI, and this level decreased with time, whereas very few (about 1.7%) transplanted cells were found at 6 weeks post-AMI (Figures S7A–S7C). Given that the transplanted Nes+cMSCs have not shown any evidence for transdifferentiating into cardiomyocytes (Figure S7D), we used immunohistochemistry to analyze the peri-infarct microvasculature at 14 days post-injection and found a higher density of capillaries and arterioles in Nes+cMSC-transplanted groups with respect to the Nes+bmMSC-transplanted group (p < 0.05; Figure S7E). We also observed the superior effect of Nes+cMSCs versus Nes+bmMSCs on promoting the proliferation of endogenous cardiomyocytes in peri-infarcted ventricles and protecting the ischemic cardiomyocytes from death in the infarct border zone 2 weeks post-AMI (Figure S7F). Using the H2O2-induced cardiomyocyte cell line H9c2 apoptosis model, we observed that co-culturing with Nes+cMSCs in the transwell system significantly increased the proliferation and cell survival of the cardiomyocyte group, compared to the Nes+bmMSC group (Figure S7G). Moreover, RNA-seq data also showed that Nes+cMSCs express more abundant angiogenesis- (Figure S7H), proliferation- (Figure S7I), and anti-apoptosis-related genes (Figure S7J) than do Nes+bmMSCs. Both of these results indicate that MSCs have the multifactorial and multidimensional mechanisms of paracrine action for cardiac repair.39

However, the above results focused on the medium or long-term effects of Nes+cMSCs; the early events (within 1 week) after AMI are less well characterized. The myocardial healing response includes the inflammatory phase and the reparative phase. Accumulating evidence indicates that the inflammatory reaction mediated by neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and lymphocytes clears the wound of dead cells and debris, thereby providing key signals to activate the reparative cascades. Alternatively, an exaggerated inflammatory reaction in the early phase after AMI may evoke adverse remodeling.40,41

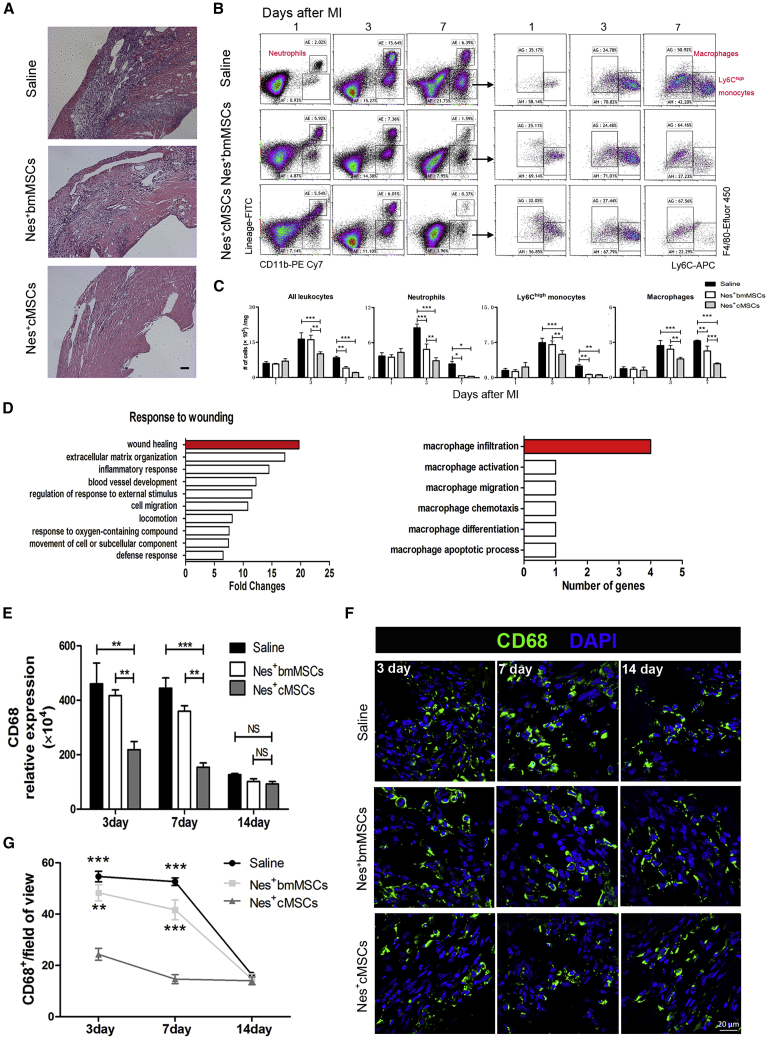

Therefore, we investigated whether Nes+cMSCs participate in cardiac repair through rapidly and effectively dampening excessive immune response during the early inflammation stage. Our histological analysis indicated that numerous inflammatory cells infiltrated the ischemic myocardium in the saline group (this was partially rescued in the Nes+bmMSC group) and that Nes+cMSC transplantation significantly decreased this infiltration and improved the integrity of the myocardial structure (Figure 3A). Moreover, flow cytometry revealed that the accumulation of neutrophils, macrophages, and Ly-6Chigh monocytes was attenuated in the infarcted hearts of Nes+cMSC-treated mice at 3 and 7 days after AMI, compared to those of the saline and Nes+bmMSC groups. Furthermore, we found that the proportions of macrophages decreased the most among these inflammatory cells at 3 and 7 days post-AMI (Figures 3B and 3C). To better understand how Nes+cMSC treatment promotes cardiac wound healing more effectively than does Nes+bmMSC therapy, we analyzed the RNA-seq data and found 46 secretory protein-encoding genes that were more highly expressed in Nes+cMSCs (FPKM more than 20 and more than 1.5-fold change) compared with Nes+bmMSCs during the response to wounding. Notably, Nes+cMSCs were highly enriched (∼20-fold) in genes related to wound healing, most of which were relevant to macrophage infiltration (Figure 3D). Given that macrophages are key mediators of the inflammatory response and are responsible for initiating/inhibiting inflammation as early as 1 week post-AMI,7,42,43 we further examined macrophage infiltration via qPCR and IF staining analyses for 2 weeks after AMI. Compared with the saline and Nes+bmMSC groups, Nes+cMSC treatment significantly reduced the high-level mRNA expression of CD68 (a marker of total macrophages) in the infarct area at 3 and 7 days post-AMI; in contrast, no obvious difference was seen at 14 days post-AMI, when CD68 was expressed at a low level in all samples (Figure 3E). Similarly, IF staining analysis indicated that the number of CD68+ macrophages in the infarcted area was largely reduced in the Nes+cMSC-treated group at days 3 and 7 post-AMI, but not at day 14 post-AMI (Figures 3F and 3G). Taken together, these data indicate that transplantation of Nes+cMSCs, but not Nes+bmMSCs, significantly reduces the total number of macrophages infiltrating the injured heart tissue during the first week after AMI.

Figure 3.

Transplantation of Nes+cMSCs, but Not Nes+bmMSCs, Significantly Suppresses Inflammation and Reduces the Total Number of CD68+ Macrophages within the Infarcted Area after AMI

(A) Histopathologic analysis (H&E staining) of samples obtained from the saline, Nes+bmMSC, and Nes+cMSC groups at 7 days post-AMI; n = 4 per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Representative flow dot plots of MI tissue cell suspensions obtained from each group at 1, 3, and 7 days after MI. (C) Flow cytometry-based quantification of the indicated cells in the hearts of each group at 1, 3, and 7 days after MI; n = 5 per group from at least two independent experiments. (D) Gene Ontology of genes that responded to wounding (normalized with respect to the level of GAPDH); the top hits included many genes related to wound healing, among which we observed enrichment for genes involved in macrophage infiltration. (E) The mRNA levels of CD68 (a marker of total macrophages) in the infarcted areas at 3, 7, and 14 days post-AMI were analyzed; n = 4. (F and G) CD68+ macrophages in the infarcted regions at 3, 7, and 14 days post-AMI were determined under fluorescence microscopy (F) and calculated from eight random fields of view for each experiment using a double-blind method (G). Green indicates CD68+ macrophages, and blue indicates nuclei. Scale bar, 20 μm. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 4. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

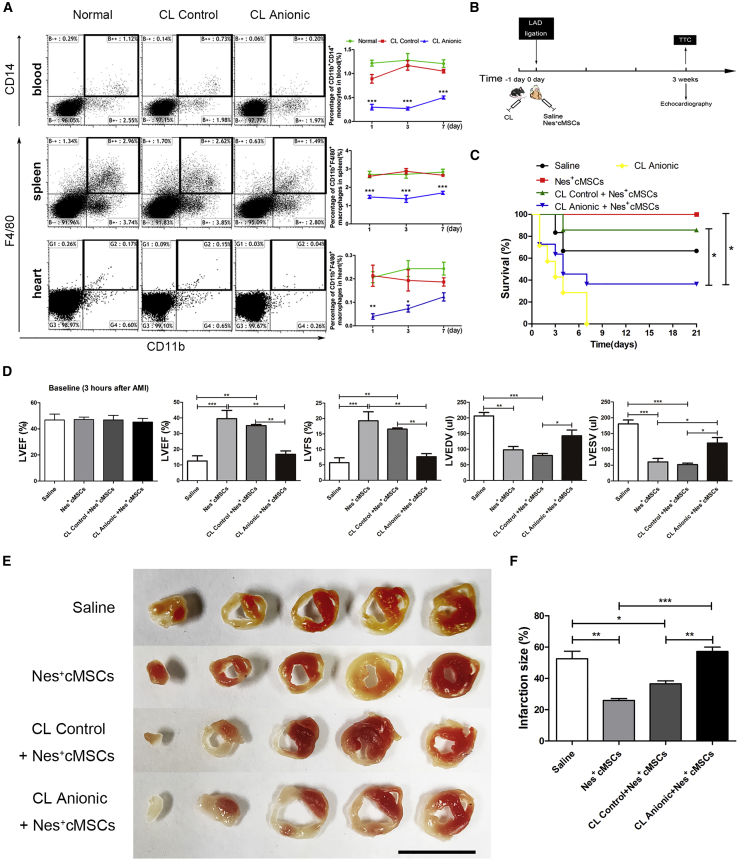

The Cardioprotective Effect of Nes+cMSC Therapy Is Reduced by Systemic Depletion of Macrophages

To further confirm the role of macrophages mediating the cardioprotective effect of Nes+cMSC transplantation, we administered anionic clodronate liposomes (CL Anionic) or control clodronate liposomes (CL Control) through the tail veins of mice to deplete them of monocytes/macrophages. Analysis of monocytes/macrophages in spleen and blood within 1 week after administration showed that CL Control did not obviously change the percentage of CD11b+CD14+ monocytes in blood or CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages in spleen, compared with the normal control group, but that CL Anionic significantly reduced these percentages at 1, 3, and 7 days after CL administration (Figure 4A). We also investigated their capacity to deplete resident macrophages in heart, and found that CL Anionic treatment could significantly deplete the CD11b+F4/80+ resident macrophages in heart at 1 and 3 days (Figure 4A). Taken together, these results strongly demonstrate that CL Anionic could effectively deplete various monocyte/macrophage populations in the blood, spleen, and heart within 1 week. Accordingly, we used CL Anionic to deplete macrophages in vivo for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 4.

The Depletion of Macrophages by Intravenous Injection of Clodronate Liposomes (CLs) Attenuates the Functional Recovery of the Heart Post-AMI after Nes+cMSC Treatment

(A) The percentages of CD11b+CD14+ monocytes in blood and CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages in spleen and heart were analyzed by flow cytometry at 1, 3, and 7 days after CL injection. (B) Schematic of the strategies used for the systemic depletion of macrophages, AMI model establishment, and cardiac function analysis. One day before establishment of the AMI model (−1 day), mice were systematically depleted of macrophages using anionic clodronate liposomes. At 0 day, the AMI model was generated by permanent ligation of the LAD coronary artery. One minute later, the ischemic area was identified and saline (vehicle-treated control) or Nes+cMSCs were intramyocardially injected into the infarct border zone. Cardiac function and the degree of infarct were analyzed by echocardiography and TTC staining, respectively, at 3 weeks post-AMI. (C) The survival rate of mice was analyzed after macrophage depletion and Nes+cMSC treatment; n = 15–30. (D) Heart function was evaluated by echocardiography at 3 h (baseline) and 3 weeks post-AMI, and LVEF, LVFS, LVEDV, and LVESV were measured; n = 10–15. (E and F) Five heart sections (1 mm thick) from the various groups were stained with 1% TTC for visualization of the infarct area (pale) and viable myocardial area (brick red). Scale bar, 10 mm (E). Comparison of the relative scar areas among the study groups. The ratio of the length of the infarct band to the total length of the LV was calculated; n = 5 (F). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. CL Control, clodronate-free liposomes (negative control); CL Anionic, clodronate-containing liposomes.

We tested the therapeutic effect of Nes+cMSCs in mice subjected to macrophage depletion (the experimental scheme is depicted in Figure 4B). The mortality of mice was monitored daily in each group (from 0 to 21 days). Mortality was highest in macrophage-depleted MI mice treated with Nes+cMSCs (CL Anionic+Nes+cMSCs, 63.64%). In the CL Control+Nes+cMSCs group, which experienced less macrophage depletion, the mortality was significantly reduced to 14.29%. Infarcted MI mice with intact macrophages (i.e., those not subjected to clodronate liposome treatment) with and without Nes+cMSC transplantation experienced lower mortality (0% and 33.33%, respectively; Figure 4C). Our echocardiographic analysis showed that Nes+cMSC treatment did not restore heart function after macrophage depletion (CL Anionic+Nes+cMSC group); similar to the saline-treated group, such mice exhibited significantly lower LVEF and LVFS values and higher LVEDV and LVESV values (Figure 4D). Notably, the Nes+cMSC and CL Control+Nes+cMSC groups exhibited significantly better functional recovery than did the saline-treated group at 3 weeks post-AMI (Figure 4D). Consistent with these findings, TTC staining indicated that the CL Anionic+Nes+cMSC group exhibited impeded healing of wounded heart tissues and larger infarct sizes in the left ventricle, compared with the CL Control+Nes+cMSC group (the ratio of infarct area to the total length of LV were 57.27% ± 3.84% versus 36.55% ± 2.69%, respectively; Figures 4E and 4F).

Taken together, these results indicate that macrophages play a critical role in the myocardial wound healing of mice treated with Nes+cMSCs, and that depletion of macrophages impedes the favorable effects of Nes+cMSCs in mice.

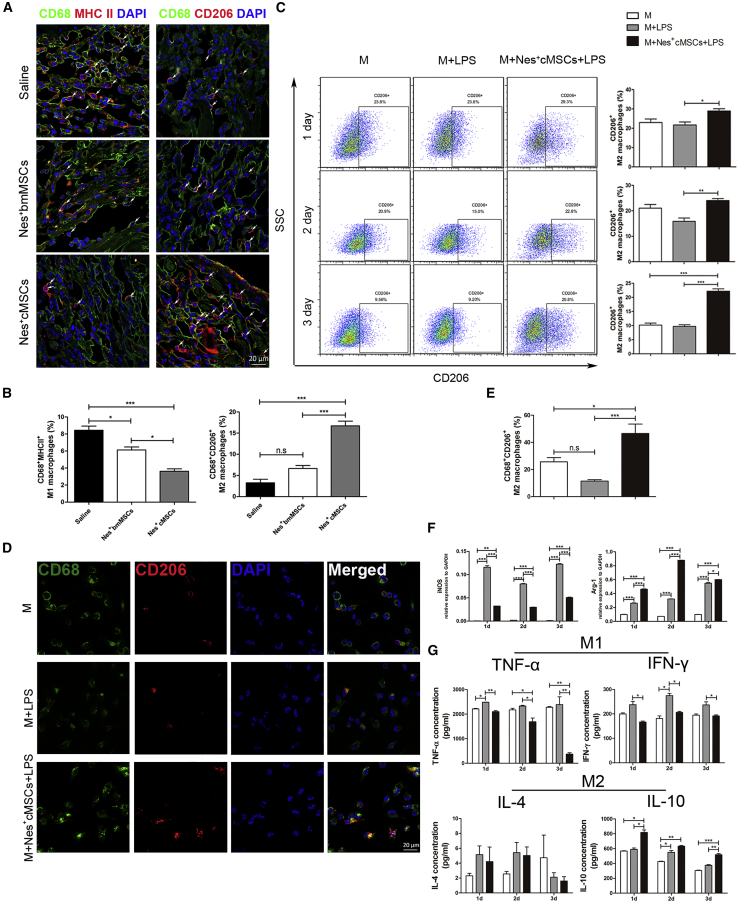

Nes+cMSCs Increase the Proportion of M2 Macrophages In Vivo after AMI and Regulate Their Polarization In Vitro

Since Nes+cMSC transplantation exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing the number of pan-macrophages within the ischemic heart (Figures 3E–3G), and the phenotypic modulation of macrophages is critical for tissue repair post-AMI,7,44 we then analyze the macrophage subsets (CD68+major histocompatibility complex class II [MHCII]+ M1 macrophages and CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages) present in the infarcted myocardium of the various mouse groups. We observed that Nes+cMSC treatment largely reduced the percentage of CD68+MHCII+ M1 macrophages while dramatically increasing those of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages in the infarct zone, whereas Nes+bmMSC treatment decreased the percentage of M1 macrophages but failed to obviously increase that of M2 macrophages (Figures 5A and 5B). To further investigate whether Nes+cMSCs might modulate the polarization of macrophages in vitro, we co-cultured Nes+cMSCs and macrophages in a transwell system. Macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity following Brewer thioglycolate stimulation, which yields less red blood cell contamination and a higher purity/yield of macrophages.45 We analyzed the percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages by flow cytometry after 1, 2, and 3 days of co-culture. The percentages of M2 macrophages were higher at all time points in the Nes+cMSC co-cultures versus mono-cultured macrophages (Figure 5C). Additionally, compared with Nes+bmMSCs, Nes+cMSCs showed a superior effect in inducing the polarization of M2 macrophages in vitro (Figure S8). IF staining showed that CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages were 4-fold more abundant in Nes+cMSC co-cultures than in the M+LPS (lipopolysaccharide) group (46.60% ± 9.77% versus 11.54% ± 1.91%, respectively; Figures 5D and 5E). We further used qPCR analysis to confirm the mRNA expression levels of markers for M1 (inducible NO synthase [iNOS]) and M2 (arginase-1 [Arg-1]) macrophages. Compared to the M+LPS group, the M+Nes+cMSCs+LPS group exhibited a marked decrease in iNOS expression, whereas Arg-1 was increased at 1, 2, and 3 days of co-culture (Figure 5F). M1 macrophages can produce numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α and interferon [IFN]-γ), and M2 macrophages can secrete many cytokines (e.g., interleukin [IL]-4 and IL-10) that critically inhibit inflammatory responses.46 Consistent with this, our analyses of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in vitro revealed that the concentrations of TNF-α and IFN-γ were significantly reduced when LPS-stimulated macrophages were co-cultured with Nes+cMSCs. Moreover, Nes+cMSC treatment significantly increased the level of IL-10 but did not significantly alter that of IL-4 (Figure 5G). Taken together, these findings suggest that Nes+cMSC treatment may increase the proportion of M2 macrophages as early as 1 week post-AMI by inducing the polarization of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, and that this may inhibit the pro-inflammatory response in the infarcted myocardium.

Figure 5.

Treatment with Nes+cMSCs, but Not Nes+bmMSCs, Largely Increases the Proportion of M2 Macrophages in the Infarcted Myocardium In Vivo and Regulates the Polarization of M2 Macrophages In Vitro

(A and B) CD68+MHC II+ M1 macrophages and CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages were detected in the infarcted areas at 7 days post-AMI under fluorescence microscopy (A), and the percentages of CD68+MHC II+ M1 macrophages and CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages in CD68+ total macrophages were calculated using a double-blind method (B). Scale bar, 20 μm; n = 5. (C) The percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages was analyzed by flow cytometry after macrophages were co-cultured for 1, 2, and 3 days with or without Nes+cMSCs; n = 4. (D and E) CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages were detected by immunofluorescence (IF) staining after 3 days of co-culture with or without Nes+cMSCs. Green indicates CD68+ macrophages, red indicates CD206+ M2 macrophages, and blue indicates nuclei (D). Scale bar, 20 μm. The percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages was analyzed (E); n = 5. (F) The mRNA expressions of key macrophage differentiation-related enzymes (iNOS and Arg-1) were analyzed after 3 days of co-culture with or without Nes+cMSCs; n = 3. (G) The secretion levels of M1 macrophage-produced pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IFN-γ) and M2 macrophage-secreted anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10) in supernatants after 3 days of co-culture with or without Nes+cMSCs, as examined by ELISA. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 5. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant. LPS was used to activate macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype.

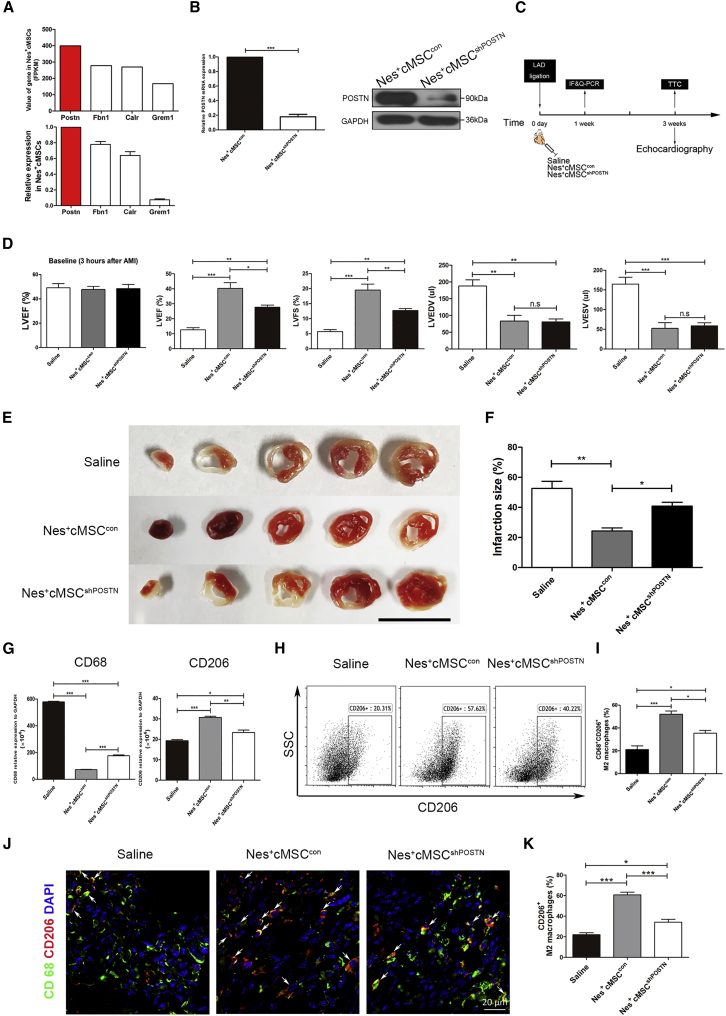

Downregulation of POSTN in Nes+cMSCs Impedes Cardiac Repair In Vivo by Decreasing M2 Macrophages in the Infarcted Myocardium

To elucidate the potential candidates participating in the Nes+cMSC-mediated macrophage polarization, we analyzed the RNA-seq data related to macrophage infiltration and function (Figure 3D). Among them, POSTN (which encodes Periostin) had the highest expression in Nes+cMSCs (FPKM > 350), as confirmed by qPCR (Figure 6A). Conversely, Nes+bmMSCs showed much lower expression of POSTN than that of Nes+cMSCs (Figures S9A–S9C). POSTN is secreted by glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) and reportedly plays an important role in recruiting M2 tumor-associated macrophages.47 Thus, we next tested whether Nes+cMSC-secreted POSTN contributes to the ability of these cells to polarize M2 macrophages in vitro and in vivo. We first used RNA interference to knock down POSTN expression in Nes+cMSCs. qPCR and western blot analyses showed that the mRNA and protein levels of POSTN were largely reduced in the Nes+cMSCshPOSTN group compared with the Nes+cMSCcon group (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Knockdown of POSTN Impedes the Ability of Nes+cMSCs to Promote Cardiac Function Recovery by Reducing the Recruitment of M2 Macrophages to the Infarcted Site

(A) From among the 46 genes found to be upregulated in Nes+cMSCs, the FPKM values of four predicted to be associated with macrophage infiltration are shown, as are the results of our qPCR-based analysis of the relative mRNA expression levels of paracrine factors in Nes+cMSCs. (B) The efficiency of the shRNA-mediated downregulation of POSTN was assessed at the mRNA and protein levels. The mRNA expression of POSTN in the Nes+cMSCcon group was regarded as 1. (C) Schematic of the protocol used for AMI model establishment and cardiac function analysis. At 0 day, the AMI model was generated by permanent ligation of the LAD coronary artery. One minute later, the ischemic area was identified and saline (vehicle-treated control), Nes+cMSCcon, or Nes+cMSCshPOSTN was intramyocardially injected into the infarct border zone. Cardiac function and infarct degree were analyzed by echocardiography and TTC staining, respectively, at 3 weeks post-AMI. The mRNA and protein levels of M2 macrophage markers in infarcted areas were analyzed by qPCR (for mRNA), flow cytometry, and immunofluorescence (IF) staining (for proteins) at 1 week post-AMI. (D) Heart functions were evaluated by echocardiography at 3 h (baseline) and 3 weeks post-AMI, and LVEF, LVFS, LVEDV, and LVESV were measured; n = 15–20. (E and F) Five heart sections (1 mm thick) from each group were stained with 1% TTC for visualization of the infarct area (pale) and the viable myocardial area (brick red). Scale bar, 10 mm (E). Comparison of the relative scar areas among the study groups. The ratio of the length of the infarct band to the total length of the LV was calculated; n = 5. (F). (G) The CD68 and CD206 expression levels of M2 macrophages in the infarct areas at 7 days post-AMI were analyzed at the mRNA level; n = 5. (H and I) The CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages in the infarcted areas at 7 days post-AMI were analyzed by flow cytometry (H), and the percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages was calculated (n = 5) (I). (J and K) The CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages in the infarcted areas at 7 days post-AMI were determined under fluorescence microscopy (J). Scale bar, 20 μm. The percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages was calculated using a double-blind method (K). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 5. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. n.s., not significant; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

To investigate whether POSTN knockdown could alter the therapeutic effect of Nes+cMSCs in the AMI model, we injected saline, Nes+cMSCcon, or Nes+cMSCshPOSTN into the infarct border zone after left anterior descending (LAD) ligation. Flow cytometry, IF staining, and qPCR were used to analyze the macrophage subpopulations at 1 week post-AMI, and cardiac function and heart infarct sizes were evaluated at 3 weeks post-AMI (Figure 6C). Echocardiography showed that Nes+cMSCcon treatment significantly increased LVEF and LVFS and decreased LVEDV and LVESV at 3 weeks post-AMI, compared with the saline group; moreover, LVEF and LVFS were clearly lower in Nes+cMSCshPOSTN mice compared to Nes+cMSCcon mice (Figure 6D). The infarct size at 3 weeks post-AMI was significantly larger in the Nes+cMSCshPOSTN group compared to the Nes+cMSCcon group (Figures 6E and 6F). With respect to the macrophage subpopulations, qPCR revealed that the Nes+cMSCshPOSTN group exhibited markedly higher mRNA expression of CD68 and lower mRNA expression of CD206 in infarcted myocardium, compared to the Nes+cMSCcon group (Figure 6G). Moreover, flow cytometric analysis and IF staining also showed that, when compared to the Nes+cMSCcon group, the Nes+cMSCshPOSTN group had a significantly smaller percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages in the infarcted area (Figures 6H–6K).

To ascertain whether Nes+cMSC-secreted Periostin has a direct effect in rescuing MI mice, we injected a Periostin-neutralizing antibody (referred to as Ab in the figures) into the myocardium along with Nes+cMSCs transplantation after AMI. The expression of Periostin in myocardium was analyzed by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining and ELISA at 1, 3, and 7 days post-AMI. The results showed higher expression of Periostin in the Nes+cMSC-treated group and decreasing clearly in the Ab-treated group (Figures S10A and S10B). Mortality was highest in Periostin-depleted MI mice with Nes+cMSC transplantation (Nes+cMSCs+Ab group, 60.00%), whereas infarcted MI mice of the Nes+cMSCs group almost always survived (Figure S10C). LVEF and LVFS of MI mice in the Nes+cMSCs+Ab group were significantly reduced compared with those of the Nes+cMSCs group at 3 weeks post-AMI (Figure S10D). Infarct size was significantly smaller in the Nes+cMSC group than in the Nes+cMSCs+Ab group (Figures S10E and S10F). Finally, the percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages in the infarcted zone was reduced after Ab treatment (Figures S10G and S10H). These data indicate that Nes+cMSC-derived Periostin is an important factor in the stem cell-driven cardioreparative function.

Taken together, our findings indicate that knockdown and neutralization of Periostin in Nes+cMSCs impedes cardiac function and wound healing after AMI by decreasing M2 macrophages in the infarcted heart.

POSTN Knockdown in Nes+cMSCs Inhibits M2 Macrophage Polarization In Vitro

To investigate whether POSTN knockdown altered the balance of macrophage subtypes in vitro, we performed co-culture experiments. Flow cytometry showed that POSTN knockdown gradually reduced the percentages of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages over time in the co-culture system, and that these changes were stronger in the M+Nes+cMSCshPOSTN+LPS group than in the M+Nes+cMSCcon+LPS group (Figures S11A and S11B). IF staining showed that the percentages of CD68+MHCII+ M1 macrophages were significantly higher in the M+Nes+cMSCshPOSTN+LPS groups compared with the M+Nes+cMSCcon+LPS group, whereas the percentages of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages were markedly reduced in the POSTN-deficient groups (Figures S11C and S11D).

Discussion

In summary, this study provides new insights into the optimal cell source for cardiac repair using cardiac-resident MSCs. We show that cardiac Nestin+ cells exhibit properties of MSCs, including self-renewal capacity, clonogenicity, and multipotency. We further demonstrate that Nes+cMSCs are more effective than Nes+bmMSCs for cardiac repair, indicating that cardiac-resident MSCs offer distinct advantages over non-resident MSCs for treating AMI. Mechanistically, Nes+cMSCs perform their reparative functions partly through the Periostin-mediated polarization of macrophages to the M2 subtype.

The paracrine and immunomodulation properties of MSCs have been verified to contribute to the beneficial actions on myocardial remodeling and function. Preclinical studies from animal models and clinical trials also demonstrated that MSC therapy was safe for treating CVD. However, their efficacy remains controversial, limiting the clinical application of this therapy.48 One of the significant challenges is the identification of the best source of MSCs for cardiac repair. It is conceivable that MSCs derived from a specific organ or tissue may exhibit biased functional potential,17,49 indicating that cardiac MSCs may be an excellent candidate of cell therapy for cardiac damage.50,51 Unfortunately, because there is no specific marker to identify MSCs, whether cardiac MSCs are therapeutically superior to other tissue-derived MSCs for cardiac repair has not been completely clarified. In this study, we prospectively isolated Nestin+ cells from heart or bone marrow based on the GFP fluorescence intensity of Nestin-GFP mice, and identified Nes+cMSCs showed similarities in morphology, cell surface antigen profile, self-renewal, tri-lineage differentiation potential, and transcriptome with Nes+bmMSCs. These results may not only verify that Nestin is a specific marker for prospectively isolating tissue-resident MSCs, but they also provide a new approach to directly compare the therapeutic potential of MSCs derived from various sources.

Also, note that Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs are remarkably similar to the expression of a suite of known fibroblast (i.e., Col3a1, Col1a1, Col1a2, Vim, Flna, Ddr2, Pdgfra, and Thy1) and pericyte markers (i.e., Pdgfrb, Acta2, and Cspg4) (Figures S3D and S3F). Because previous studies have reported that MSCs show a broad overlap with fibroblasts both in vitro and in vivo,52,53 it is difficult to discriminate between fibroblasts and mesenchymal cells of cardiac and bone marrow origin based on the phenotype or transcription profiles. Therefore, we defined these cells as “mesenchymal stromal cells.” However, the origin of Nestin+ cells from various tissues remains unknown and will require lineage-tracing studies to resolve this issue.

Previous studies have identified the existence of cardiac MSCs.20,21 However, only very few experiments have directly compared the cardioreparative functions between cardiac MSCs and other tissue MSC populations.19 In this study, we herein provide the first experimental evidence showing that Nes+cMSCs are more effective than Nes+bmMSCs for cardiac repair following AMI, as shown by higher LVEF and LVFS, lower LVEDV and LVESV, and reduction of the heart infarct size (Figure 2), suggesting that cardiac MSCs may represent a more suitable cell source for cardiac repair because of their cardiovascular-associated features. More importantly, compared with the Nes+bmMSC group, Nes+cMSC transplantation showed higher myocardial vascular density, a greater number of proliferating cardiomyocytes, and fewer apoptotic ischemic cardiomyocytes in the infarct border zone, indicating their superior angiogenic and antiapoptotic properties. Given that the transplanted Nes+cMSCs have not shown any evidence of differentiating into cardiomyocytes (Figure S7D), the paracrine activity of MSCs may participate in the beneficial actions on myocardial remodeling through promoting angiogenesis and stimulation of prosurvival pathways.21,54 Our RNA-seq data also confirmed that Nes+cMSCs express more abundant proangiogenic (Grem1, Vegfa), prosurvival (Igf1, Ptn), and anti-apoptotic genes (Grem1, IL6) than do Nes+bmMSCs.

Myocardial infarction triggers pro-inflammatory cascades that are essential for cardiac repair, but an exaggerated inflammatory reaction also evokes adverse post-infarction remodeling and heart failure.55 In the early phase (within 1 week) after AMI, macrophages are the major population of immune cells, which peak during the first week post-AMI, and they persist through all stages of the repair response.44 Through this process, macrophages remove the dead cells, but at the same time they stimulate local inflammation by secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, effective approaches to balance a sufficient immune response to clear the wound of dead cells and debris, while not damaging self, are key to more effective treatment and better prognosis. MSCs exert a broad spectrum of immunoregulatory effects, and previous studies demonstrate that MSCs reduce macrophages and promote M2 macrophage polarization post-AMI, indicating that macrophages may be involved in the cardioprotective effect of transplanted MSCs in MI.7,56 The present study shows that Nes+cMSC treatment significantly attenuated neutrophil, Ly-6Clow macrophage, and Ly-6Chigh monocyte accumulation in the infarct heart at 3 and 7 days after MI, compared to saline and Nes+bmMSC groups. Macrophages were decreased most significantly among these inflammatory cells at both time points (Figure 3B), and depletion of macrophages impedes the favorable effects of Nes+cMSCs therapy after MI (Figure 4). These results are in line with the recent reports7 and verify that macrophages play a critical role in the myocardial wound healing of mice treated with Nes+cMSCs. Experimental studies have described dynamic changes in macrophage phenotype in the infarcted heart, which suggests a transition from early infiltration with pro-inflammatory M1 cells to the late predominance of reparative M2 macrophages.57, 58, 59 Herein, we found that Nes+cMSC treatment could strongly inhibit the inflammatory response by reducing the number of CD68+ pan-macrophages in the infarct region post-AMI, and that the percentage of CD68+CD206+ M2 macrophages was significantly increased in the infarcted myocardium of the Nes+cMSC group.

In view of the possible mechanisms involved in macrophage polarization by MSCs, there is a need to determine which pathways participate in the modulation process. Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-4 and IL-13 are key factors in inducing monocytes to differentiate to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages in vitro.60,61 Moreover, alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages) can also be induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β.62,63 However, after checking the RNA-seq data, we found that these ligands were scarcely expressed by Nes+cMSCs (the FPKM values of IL-4, IL-13, GM-CSF, and TGF-β2 were 0.025, 0, 0.019, and 2.88, respectively). Therefore, the polarization of M2 macrophages might be induced via other factors. In our study, we screened for candidate factors by analyzing the RNA-seq data related to macrophage infiltration and function (Figure 3D) and identified that POSTN had the highest expression in Nes+cMSCs (FPKM > 350) (Figure 6A). POSTN (which encodes Periostin, and was originally called OSF-2) is a member of the Fasciclin family and is a disulfide-linked cell adhesion protein.64 POSTN is also a secreted extracellular matrix protein that was originally identified in mesenchymal-lineage cells (osteoblasts, osteoblast-derived cells, and cells of the periodontal ligament and periosteum), and it has been associated with the differentiation of mesenchyme in the developing heart.65 Moreover, POSTN is involved in various aspects of tumorigenic processes.66 Zhou et al.47 previously reported that POSTN secreted by GSCs could recruit M2 type TAMs through integrin αVβ3 signaling to support glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) growth, but they not claim whether POSTN modulates the polarization of macrophages. Importantly, our results show for the first time that Nes+cMSC-secreted POSTN contributes to M2 macrophage polarization and promotes cardiac tissue wound healing (Figure 6). Additionally, the depletion of POSTN in the infarcted myocardium by injection of corresponding neutralizing antibody significantly attenuated the survival rate and cardiac function of MI mice, as well as reduced the M2 subtype polarization of macrophages in vivo (Figure S10). Also, note that the much lower expression of POSTN in the Nes+bmMSCs than that in Nes+cMSCs also provides the evidence to explain the difference of therapeutic effects between these two groups (Figures S9A–S9C). In this study, we uncovered a new function by demonstrating that Periostin regulates the M2 polarization of macrophages in our system. Although Oka et al.67 reported the fibrogenic actions of Periostin following MI, they also reported the cardiac protective function of Postn in the same paper. Mice lacking the gene encoding Pn (Postn) were more prone to ventricular rupture in the first 10 days after MI, and inducible overexpression of Pn in the heart protected mice from rupture.67 In addition, Kühn et al.68 demonstrated that Periostin induces proliferation of differentiated cardiomyocytes and promotes cardiac repair through improving ventricular remodeling and myocardial function, reducing fibrosis and infarct size, and increasing angiogenesis. Both of these results indicate that Periostin may have a distinct role at different stages of myocardial remodeling; thus, targeting Periostin-mediated macrophage polarization at specific time points could further improve wound healing and functional outcome. The myocardial healing response after MI can be divided into three sequential overlapping phases: (1) the inflammatory phase, (2) the proliferative phase, and (3) the maturation phase. In the early phase (within 1 week), Periostin may play the cardiac healing function through mediating M2 macrophage polarization and reducing the inflammatory burden in the post-infarct myocardium; during the proliferative phase, it might participate in cardiac fibrosis, and in scar formation during the maturation phase.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was designed to investigate the properties of cardiac-resident Nestin+ MSCs in Nestin-GFP transgenic mice, as well as their therapeutic role in cardiac repair after AMI, when compared with non-resident Nestin+bmMSCs. These objectives were addressed by (1) isolating the Nestin-GFP+ cells from heart and bone marrow of mice using flow cytometry, and analyzing the property of the two Nestin+ types of cells by the RNA-seq method; (2) evaluating the treatment effects of Nes+cMSC and Nes+bmMSC transplantation on heart repair by analyzing echocardiography and calculating infarction size; (3) elucidating the underlying mechanisms in vivo and in vitro using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) interference that are specific to the POSTN gene; and (4) demonstrating the Nes+cMSC-derived POSTN-mediated M2 macrophage polarization in wound healing after AMI. In all experiments, animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups, and researchers were blinded during treatment and data collection. Group and sample sizes for each experiment are indicated in each figure legend. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes for in vitro experiments.

Mice

Homozygous Nestin-GFP transgenic mice of the C57BL/6 genetic background were as previously reported.24,25 C57BL/6 wild-type mice were purchased from the Animal Center at the Medical Laboratory of Guangdong Province, China. All mice used for in vivo studies were 12-week-old male C57BL/6 mice, and mice were randomly allocated to each group. Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility, and all animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Sun Yat-sen University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation and Culture of Mouse Heart- and Bone Marrow-Derived Nestin+ Cells

The hearts of 7-day-old Nestin-GFP and C57BL/6 mice (blank control) were harvested and incubated with 5 mL of Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) digestive solution including type II collagenase (300 U/mL; Gibco) and DNase I (100 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich). The tissues were homogenized and incubated at 37°C for 30 min, with shaking performed every 10 min. The resulting cell suspensions were passed through a 40-μm cell strainer to prepare a single-cell suspension. GFP+ cells were sorted using flow cytometry (Influx, BD) and cultured in a 2:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 (1:1) and Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) (Gibco) containing 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Peprotech), 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (Peprotech), 1% N2 (Invitrogen), 2% B27 (Invitrogen), 4 ng/mL Cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1; Peprotech), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), 1% l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), and 100 IU/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Mouse bone marrow-derived Nestin+ cells were isolated from 7-day-old Nestin-GFP mice by flow cytometric sorting and cultured in growth medium, as reported previously.23 Both heart- and bone marrow-derived Nestin+ cells were thereafter cultured in ultra-low adherence dishes (Corning) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 water-jacketed incubator to form many clonal spheres. These cells were propagated every 3 days, and cells from similar passages were used in all assays.

Clonal Sphere Formation Assay

Clonal sphere formation was assessed using our previously reported method.24 Briefly, sorted single-cell suspensions of Nestin-GFP+ cells were diluted to a density of 500 cells/mL, and 2 μL/well of the diluted cell suspension was plated to an ultra-low-attachment 96-well plate (Corning) in 150 μL/well of complete medium. Wells containing only one cell were marked and observed daily. After 10 days in culture, we scored for single cells that had generated spheres >50 μm in diameter.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Flow cytometric sorting was performed with an Influx apparatus (BD), while flow cytometric analyses were performed with Influx or Gallios (Beckman Coulter) flow cytometers. Data were analyzed with FlowJo7.5 software (Tree Star) or Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter). The following anti-mouse antibodies were used: CD44-phycoerythrin (PE) (IM7), CD106-Alexa Fluor 647 (429), Sca-1-allophycocyanin (APC) (D7), c-Kit-APC-eFluor 780 (2B8), CD90-PE (30-H12), CD45-PE-Cyanine7 (30-F11), CD34-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (RAM34), CD68-PE (FA-11), CD11b-PE-Cyanine7 (M1/70), CD14-PE (Sa2-8), F4/80-eFluor 450 (BM8), hematopoietic lineage cocktail-FITC (17A2, RA3-6B2, M1/70, TER-119, RB6-8C5), PDGFRα-APC (APA5), PDGFRβ-APC (APB5, all from eBioscience), Ly-6C-APC (AL-21, BD), and CD206-APC (C068C2, BioLegend). For EdU (5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine) and TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) analyses, the Click-iT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 647 flow cytometry assay kit and Click-iT TUNEL Alexa Fluor 647 imaging assay kit were used (Invitrogen).

Cell Differentiation Ability In Vitro

For osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation, Nestin+ cells were cultured in the relevant differentiation media for 2–3 weeks and analyzed by staining with alizarin red, oil red O, and toluidine blue staining, respectively, as previously described.69 The expression levels of lineage-specific genes (SARC and Runx2 for osteogenesis, FabP4 and PPAR-γ for adipogenesis, and CollagenII and CollagenX for chondrogenesis) were analyzed by qPCR. The following primers were used: SPARC, forward, 5′-TTGGCGAGTTTGAGAAGGTATG-3′, reverse, 5′-GGGAATTCAGTCAGCTCGGA-3′; Runx2, forward, 5′-CGTGGCCTTCAAGGTTGTA-3′, reverse, 5′-GCCCACAAATCTCAGATCGT-3′; FabP4, forward, 5′-AATCACCGCAGACGACA-3′, reverse, 5′-GTGGAAGTCACGCCTTTC-3′; PPAR-γ, forward, 5′-CTGACCCAATGGTTGCT-3′, reverse, 5′-CAGACTCGGCACTCAATG-3′; CollagenII, forward 5′-AGTACCTTGAGACAGCACGAC-3′, reverse, 5′-AGTCTCCGCTCTTCCACTCG-3′; CollagenX, forward, 5′-CAGCAGCATTACGACCCAAG-3′, reverse, 5′-CCTGAGAAGGACGAGTGGAC-3′.

IF Staining

For IF staining, cultured cells and heart tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and dehydrated with 30% sucrose. After fixation, the hearts were cut into 5-μm sections. The cultured cell and heart tissue sections were blocked for 40 min with normal goat serum, incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution), under protection from light at room temperature for 1 h. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-Nestin (1:200), anti-CD206 (1:1,000), anti-major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) (1:100), anti-NG2 (1:200), anti-fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP1) (1:200), anti-CD31 (1:20), anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (1:200), anti-α-actinin (1:100, all from Abcam), and anti-CD68 (1:100, AbD Serotec).

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells and heart tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using a RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). The generated cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR with SYBR Green reagent (Roche) using the following mouse primers: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), forward, 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′, reverse, 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′; Nestin, forward, 5′-AGGAGAAGCAGGGTCTACAGAG-3′, reverse, 5′-AGTTCTCAGCCTCCAGCAGAGT-3′; GFP, forward, 5′-AGGACGACGGCAACTACAAGCD-3′, reverse, 5′-AAGTTCACCTTGATGCCGTTC-3′; CD68, forward, 5′-ATGGACAGCTTACCTTTGGATTCA-3′, reverse, 5′-TGCCTGTGGGAAGGACACAT-3′; CD206, forward, 5′-TCTTTGCCTTTCCCAGTCTCC-3′, reverse, 5′-TGACACCCAGCGGAATTTC-3′; iNOS, forward, 5′-GAGACAGGGAAGTCTGAAGCAC-3′, reverse, 5′-CCAGCAGTAGTTGCTCCTCTTC-3′; Arg-1, forward, 5′-CATTGGCTTGCGAGACGTAGAC-3′, reverse, 5′-GCTGAAGGTCTCTTCCATCACC-3′; Periostin, forward, 5′-CAGCAAACCACTTTCACCGACC-3′, reverse, 5′-AGAAGGCGTTGGTCCATGCTCA-3′; Fbn1, forward, 5′-GCTGTGAATGCGACATGGGCTT-3′, reverse, 5′-TCTCACACTCGCAACGGAAGAG-3′; Calr, forward, 5′-AAAGGACCCTGATGCTGCCAAG-3′, reverse, 5′-TCAGGGATGTGCTCTGGCTTGT-3′; Grem1, forward, 5′-AGGTGCTTGAGTCCAGCCAAGA-3′, reverse, 5′-TCCTCGTGGATGGTCTGCTTCA-3′. The relative mRNA abundances were calculated using the ΔCt or ΔΔCt methods, and the gene expression levels were normalized with respect to those of GAPDH.

Western Blot Analysis

Total proteins were extracted from Nes+cMSCs, and the protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of proteins were separated by 8% sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS/T) containing 5% nonfat dry milk and analyzed using antibodies specific to Periostin (1:2,000, R&D Systems), GFP (1:1,000, Abcam), and Nestin (1:1,000, Abcam).

RNA-Seq of Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs

To examine the biological properties of the Nes+cMSCs and Nes+bmMSCs, we performed RNA-seq. RNA was prepared from cultured fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-purified MSCs (passage 5), sequencing libraries were constructed and sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina), and the sequenced fragments were mapped to the mouse reference genome and assembled using the CLC Main Workbench (QIAGEN). The median expression level of each reconstructed mRNA was estimated by calculating FPKM. The genes related to angiogenesis, proliferation, and anti-apoptosis were derived from the Gene Ontology (GO) database. Genes with a FPKM value more than 1 were enrolled into the analysis. The heatmaps of these genes were performed with R package.

RFP Vector Construction

To generate entry vectors, we used PCR to flank the human EF1α promoter and human RFP gene with attB4/B1r and attB1/B2 sites, respectively. The promoter-containing PCR product was cloned into pDONR P4-P1r (Invitrogen) utilizing the BP recombination method (Gateway) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The att-flanked RFP fragment was cloned into pDONR 221 (Invitrogen) using the same method. The resulting vectors, termed pUp-EF1α and pDown-RFP, respectively, were next recombined into the pDest-puro vector utilizing the LR recombination reaction protocol described in the instructions provided with the LR kit (Gateway), which included the addition of a clonase enzyme mix (Invitrogen). The final lentiviral expression vector was designated pLV/puro-EF1α-RFP (EF1α-RFP).

AMI, Cell Transplantation, Macrophage Depletion, and Functional Evaluation

The mouse model of AMI was generated by permanent ligation of the LAD coronary artery, and the surgical procedures were performed on C57BL/6 wild-type mice of similar sex (male), age (11–12 weeks), and weight (25–30 g). In brief, with minimal manipulation of the fat pad surrounding the heart, the LAD component of the left coronary artery could easily be visualized. A 10/0 Prolene suture was passed under the LAD at 1 mm distal to left atrial appendage, immediately after bifurcation of the major left coronary artery. One minute later, occlusion was confirmed by the change of color (becoming pale and of similar size) of the anterior wall of the LV, and 15 μL of cell suspension containing 3 × 105 Nestin+ cells (Nes+cMSCs or Nes+bmMSCs) or saline (vehicle-treated control) was intramyocardially injected into the infarct border zone at three different sites (final volume, 5 μL per site) via micromanipulator-guided injection.70

To determine the role of macrophage subsets in wound repair after Nestin+ cell therapy, we depleted macrophages by intravenously injecting mice with anionic clodronate liposomes (CLs; FormuMax Scientific) or liposomes (negative control).7 To achieve efficient macrophage depletion with low mortality, we injected CLs 24 h prior to AMI at the dose of 0.05 mL per 10 g of body weight, according to the previously described protocol.7,56

To examine cardiac function, conventional echocardiography was performed at 3 h (baseline), 1 week, and 3 weeks post-AMI using a mouse echocardiography system (Vevo 2100 imaging system; VisualSonics) equipped with a 30-MHz phased transducer. To examine inflammatory cell infiltration, mouse hearts were harvested at 1 and 3 weeks post-AMI, fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). To analyze the infarct size, the heart was excised and cut into five 1-mm-thick transverse slices, and each slice was incubated in a 1% solution of TTC at 37°C for 15 min for visualization of the infarct area (pale) and viable myocardial area (brick red). The ratio of the length of the infarct band to the total length of the LV was calculated.71

Mouse Macrophage Isolation and Differentiation

Macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity of mice according to a previously described protocol.45 Briefly, peritoneal macrophages were elicited by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 2 mL of 3% sterile Brewer thioglycollate medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Four days later, peritoneal exudate cells were harvested by flushing with 5 mL of ice-cold PBS (containing 3% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) using a 23G needle. The obtained cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 and plated in 12-well flat-bottom plates at 2 × 106 cells/well. After 2 h of culture at 37°C, non-adherent cells were removed by three gentle washes with warm PBS. The adherent cells, which were mainly macrophages, were analyzed by IF staining and flow cytometric analysis for CD68 expression.

Co-culture of Nes+cMSCs and Macrophages

Nes+cMSCs and macrophages were suspended in RPMI 1640. The macrophages were plated to a 12-well plate (2 × 106 cells/well) and incubated for 2 h, the non-adherent cells were removed, and 1 mL of RPMI 1640 was added to each well. A 0.4-μm transwell apparatus (Millipore) was placed within each well and loaded with 2 × 105 Nes+cMSCs. Mono-cultured macrophages were used as a control. The cells were cultured overnight, treated with or without 1 μg/mL LPS for activation, and then incubated. After 1, 2, and 3 days of incubation, macrophages were harvested, incubated with macrophage-relevant primary antibodies (i.e., anti-CD68 and anti-CD206), and analyzed by flow cytometry. For qPCR analysis, total RNA was collected and the genes encoding macrophage markers (iNOS and Arg-1) were analyzed. The secretion of cytokines to the supernatant was analyzed with ELISA (BMS607/3, BMS606, BMS613, and BMS614/2 for TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10, respectively; all from eBioscience). For IF staining, adherent macrophages were stained using markers of total macrophages (CD68), M1 macrophages (MHC II), and M2 macrophages (CD206).

Construction of the Lentivector for RNA Silencing

The utilized shRNA targeting POSTN was designed in-house and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The sequence is as follows: forward, 5′-TGCGGAGTCACTAATATCCTGAACTTCCTGTCATTCAGGATATTAGTGACTCCGTTTTTTC-3′, reverse, 5′-TCGAGAAAAAACGGAGTCACTAATATCCTGAATGACAGGAAGTTCAGATATTAGTGACTCCGCA-3′. The lentiviral vector, LentiLox 3.7 (pLL3.7), was used to generate long-term interference in mouse MSCs. An insert-free vector was used as a negative control (designated “con”).

Statistical Analysis

All results represent at least three independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± SEM. All statistical comparisons were made using a two-tailed Student’s t test (between two groups) or one-way ANOVA (for multi-group comparisons). p < 0.05 was considered significant. Analysis and graphing were performed using Prism software (v5.01, GraphPad).

Author Contributions

Y.L., G.L., M.H.J., and A.P.X designed the experiments. Y.L., G.L., X.Z., X.C., D.X., S.Z., D.L., Z.Z., J.L., B.W., W.L., Y.C., and Z.C. performed the experiments and prepared the figures. W.H. analyzed the data of RNA-seq. Y.L., M.H.J., and A.P.X. supervised direction of the project and interpretation of data and wrote the manuscript. C.P. and M.W. provided valuable comments. G.D. performed the mouse model of AMI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Stem Cell and Translational Research (2018YFA0107200, 2017YFA0103403, and 2017YFA0103802); the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA16010103 and XDA16020701); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730005, 31771616, 81770290, 81700484, 81802402, and 81971372); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2017A030310234 ); the Key Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2016B030229002, 2017B020231001, 2019B020234001, 2019B020236002 and 2019B020235002); the Key Scientific and Technological Program of Guangzhou City (201604020158, 201803040011, and 201704020223); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (18ykpy39, 19ykpy158, 19ykyjs55, 19ykyjs56, and 19ykyjs60); the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M633251); and by the Clinical Innovation Research Program of Guangzhou Regenerative Medicine and Health Guangdong Laboratory (2018GZR0301003).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.01.011.

Contributor Information

Xinxin Chen, Email: zingerchen@126.com.

Mei Hua Jiang, Email: jiangmh2@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Andy Peng Xiang, Email: xiangp@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D., Adams R.J., Brown T.M., Carnethon M., Dai S., De Simone G., Ferguson T.B., Ford E., Furie K., Gillespie C., American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:948–954. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okwuosa I.S., Lewsey S.C., Adesiyun T., Blumenthal R.S., Yancy C.W. Worldwide disparities in cardiovascular disease: challenges and solutions. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;202:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh H., Ito H., Sano S. Challenges to success in heart failure: cardiac cell therapies in patients with heart diseases. J. Cardiol. 2016;68:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams A.R., Hare J.M. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ. Res. 2011;109:923–940. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson S., Trial J., Soeller C., Entman M.L. Cardiac mesenchymal stem cells contribute to scar formation after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;91:99–107. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hare J.M., Fishman J.E., Gerstenblith G., DiFede Velazquez D.L., Zambrano J.P., Suncion V.Y., Tracy M., Ghersin E., Johnston P.V., Brinker J.A. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2369–2379. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Mordechai T., Holbova R., Landa-Rouben N., Harel-Adar T., Feinberg M.S., Abd Elrahman I., Blum G., Epstein F.H., Silman Z., Cohen S., Leor J. Macrophage subpopulations are essential for infarct repair with and without stem cell therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:1890–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams A.R., Hatzistergos K.E., Addicott B., McCall F., Carvalho D., Suncion V., Morales A.R., Da Silva J., Sussman M.A., Heldman A.W., Hare J.M. Enhanced effect of combining human cardiac stem cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to reduce infarct size and to restore cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2013;127:213–223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.131110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen P.K., Rhee J.W., Wu J.C. Adult stem cell therapy and heart failure, 2000 to 2016: a systematic review. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:831–841. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh A., Singh A., Sen D. Mesenchymal stem cells in cardiac regeneration: a detailed progress report of the last 6 years (2010–2015) Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016;7:82. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0341-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caplan A.I. Mesenchymal stem cells. J. Orthop. Res. 1991;9:641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J., Park H.C., Addabbo F., Ni J., Pelger E., Li H., Plotkin M., Goligorsky M.S. Kidney-derived mesenchymal stem cells contribute to vasculogenesis, angiogenesis and endothelial repair. Kidney Int. 2008;74:879–889. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman A.M., Paxson J.A., Mazan M.R., Davis A.M., Tyagi S., Murthy S., Ingenito E.P. Lung-derived mesenchymal stromal cell post-transplantation survival, persistence, paracrine expression, and repair of elastase-injured lung. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1779–1792. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Månsson-Broberg A., Rodin S., Bulatovic I., Ibarra C., Löfling M., Genead R., Wärdell E., Felldin U., Granath C., Alici E. Wnt/β-catenin stimulation and laminins support cardiovascular cell progenitor expansion from human fetal cardiac mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;6:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin Z., Hu J.J., Yang L., Zheng Z.F., An C.R., Wu B.B., Zhang C., Shen W.L., Liu H.H., Chen J.L. Single-cell analysis reveals a nestin+ tendon stem/progenitor cell population with strong tenogenic potentiality. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600874. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kfoury Y., Scadden D.T. Mesenchymal cell contributions to the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:239–253. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelekanos R.A., Li J., Gongora M., Chandrakanthan V., Scown J., Suhaimi N., Brooke G., Christensen M.E., Doan T., Rice A.M. Comprehensive transcriptome and immunophenotype analysis of renal and cardiac MSC-like populations supports strong congruence with bone marrow MSC despite maintenance of distinct identities. Stem Cell Res. (Amst.) 2012;8:58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramani B., Subbannagounder S., Palanivel S., Ramanathanpullai C., Sivalingam S., Yakub A., SadanandaRao M., Seenichamy A., Pandurangan A.K., Tan J.J., Ramasamy R. Generation and characterization of human cardiac resident and non-resident mesenchymal stem cell. Cytotechnology. 2016;68:2061–2073. doi: 10.1007/s10616-016-9946-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossini A., Frati C., Lagrasta C., Graiani G., Scopece A., Cavalli S., Musso E., Baccarin M., Di Segni M., Fagnoni F. Human cardiac and bone marrow stromal cells exhibit distinctive properties related to their origin. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;89:650–660. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong J.J., Chandrakanthan V., Xaymardan M., Asli N.S., Li J., Ahmed I., Heffernan C., Menon M.K., Scarlett C.J., Rashidianfar A. Adult cardiac-resident MSC-like stem cells with a proepicardial origin. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y., Sivakumaran P., Newcomb A.E., Hernandez D., Harris N., Khanabdali R., Liu G.S., Kelly D.J., Pébay A., Hewitt A.W. Cardiac repair with a novel population of mesenchymal stem cells resident in the human heart. Stem Cells. 2015;33:3100–3113. doi: 10.1002/stem.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cattaneo E., McKay R. Proliferation and differentiation of neuronal stem cells regulated by nerve growth factor. Nature. 1990;347:762–765. doi: 10.1038/347762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Méndez-Ferrer S., Michurina T.V., Ferraro F., Mazloom A.R., Macarthur B.D., Lira S.A., Scadden D.T., Ma’ayan A., Enikolopov G.N., Frenette P.S. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]