Abstract

New findings on neural regulation of immunity are allowing the design of novel pharmacological strategies to control inflammation and nociception. Herein, we report that choline, a 7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChRs) agonist, prevents carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia without affecting inflammatory parameters (neutrophil migration or cytokine/chemokines production) or inducing sedation or even motor impairment. Choline also attenuates prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2)-induced hyperalgesia via α7nAChR activation and this anti-nociceptive effect was abrogated by administration of LNMMA (a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor), ODQ (an inhibitor of soluble guanylate cyclase; cGMP), and glibenclamide (an inhibitor of ATP-sensitive potassium channels). Furthermore, choline attenuates long-lasting Complete Freund’s Adjuvant and incision-induced hyperalgesia suggesting its therapeutic potential to treat pain in rheumatoid arthritis or post-operative recovery, respectively. Our results suggest that choline modulates inflammatory hyperalgesia by activating the nitric oxide/cGMP/ATP-sensitive potassium channels without interfering in inflammatory events, and could be used in persistent pain conditions.

Keywords: Hyperalgesia, Choline, Alpha 7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, Neuroimmunomodulation, Inflammation

1. Introduction

Inflammatory hyperalgesia is mainly triggered by the sensitization of primary sensory neurons (Verri et al., 2006). During inflammation/tissue damage, the production of inflammatory factors by leukocytes, such as cytokines [e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-1β] and chemokines [e.g., keratinocyte-derived chemokine (CXCL1/KC)], induce hyperalgesia by acting directly on nociceptive neurons (Cunha et al., 2005; Verri et al., 2006). Inflammatory hyperalgesia is usually treated with conventional drugs such as the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or corticosteroids (Ferreira, 1972). However, these drugs are associated with a broad range of side effects. An alternative strategy includes the use of opioids, which are specific blockers of nociception (Cunha et al., 2010; Ferreira et al., 1991). Again, these neuronal treatments have deleterious side effects inducing sedation or motor impairment, gastrointestinal dysfunction and addiction. There is a clinical need to identify novel therapeutic strategies for treating inflammatory hyperalgesia.

Studies have indicated that the activation of either central or peripheral cholinergic pathways attenuates nociception and may provide pharmacological advantages for treating hyperalgesia (Picciotto et al., 2000). Many of these studies focused on the specific cholinergic receptors in the nervous system, which control nociceptors, or in the receptors expressed in leukocytes modulating inflammation (Decker et al., 2001; Flores, 2000). Choline is a well-known precursor in the biosynthesis of acetylcholine that showed anti-nociceptive effects attenuating nociception in hot plate, formalin and tail-flick tests (Damaj et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2005). Mounting data indicate that choline can act as a selective agonist of alpha 7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChRs) (Albuquerque et al., 1997; Alkondon et al., 1997; Papke et al., 1996). Posterior studies have revealed that α7nAChRs are expressed in neuronal and non-neuronal cells regulating nociception and inflammatory responses (Damaj et al., 2000; Parrish et al., 2008; Vida et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2002, 2005). Despite these studies, the potential of choline to modulate inflammatory hyperalgesia is still under debate.

Here, we first studied in mice whether choline can prevent the hyperalgesia and inflammatory responses in carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia model. Next, we investigated the effect of choline in PGE2-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and whether this effect could be due to the activation of the nitric oxide (NO)-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP) pathway in primary nociceptive neurons. Finally, the therapeutic potential of choline to control nociception in persistent pain was investigated in long-lasting Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) - and incision-induced hyperalgesia.

2. Results

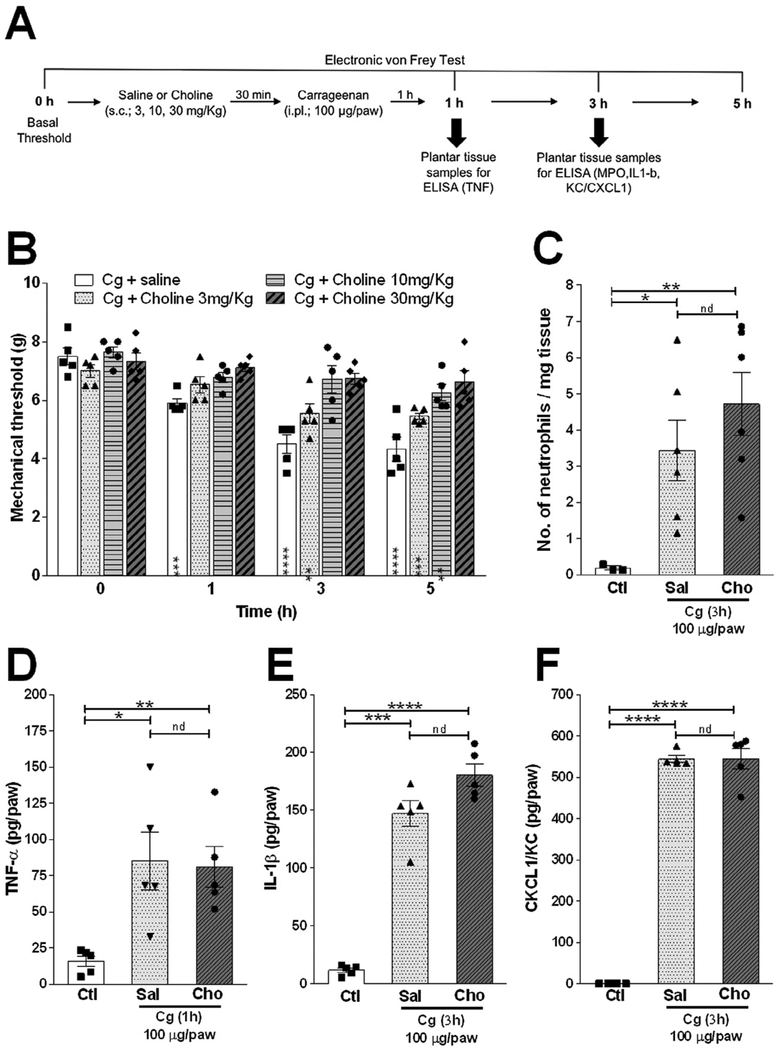

2.1. Choline inhibits carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia without affecting neutrophil migration or cytokine/chemokine production

We first analyzed the potential of choline to prevent carrageenan (Cg)-induced inflammatory hyperalgesia, an acute standard experimental model widely used for the searching of novel anti-hyperalgesic treatments. Subcutaneous treatment with choline (s.c.; 3–30 mg/kg) significantly reduced inflammatory hyperalgesia in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and B). The most consistent and significant effects of choline were observed at 10 and 30 mg/kg, and so we used these doses through this study. We next investigated whether choline modulates inflammatory hyperalgesia by inhibiting the inflammatory response in the paw tissue. Choline affected neither neutrophil recruitment nor the production of the nociceptive factors analyzed including TNF, IL-lβ, or KC/CXCL1 as compared to the control (vehicle-treated mice) (Fig. 1C–F). These results suggest that choline prevents inflammatory hyperalgesia without affecting neutrophil migration or chemokine/cytokine production.

Fig. 1.

Effect of choline on Cg-induced hyperalgesia is independent of chemokine/cytokines production and neutrophil migration. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental protocols. (B) Mice were pretreated with choline (s.c.; 3, 10 and 30 mg/kg) or vehicle 30 min before the intra-plantar injection of carrageenan (Cg; 100 μg/paw). The nociceptive responses were evaluated 1, 3 and 5 h after Cg or saline injection. (C-F) Mice were pretreated with choline (s.c.; 30 mg/kg) or vehicle 30 min before the intra-plantar injection of Cg or saline, and the plantar tissue were collected 1 or 3 h after Cg injection for the analysis of (C) neutrophil recruitment and (D) TNF, (E) IL1β, and (F) KC/CXCL1. Neutrophil recruitment and cytokines/chemokine levels were measured by MPO activity and ELISA assays, respectively. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05, * *p < 0.01 ***p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA (B) versus time 0 h, and Student’s t-test

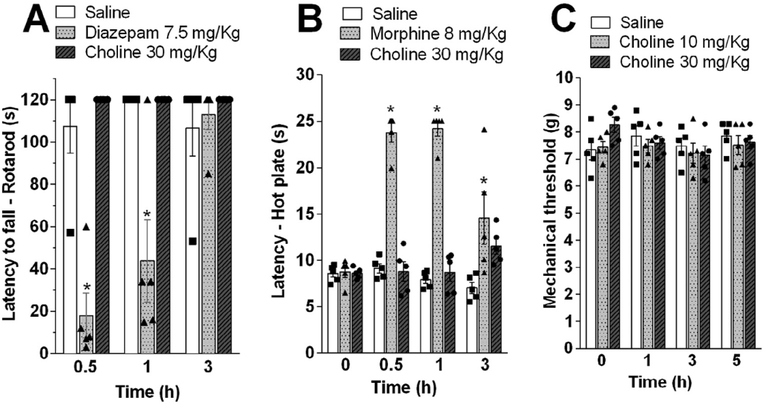

2.2. Choline attenuates nociception without inducing sedation or motor impairment

We next investigated whether choline may induce unspecific neuronal alterations while preventing nociception. We analyzed the effects of choline during the rota-rod test to evaluate whether choline may induce sedation or motor impairment (Lopes et al., 2013). Treatment with choline (s.c.; 30 mg/kg) did not induce motor impairment. These results indicated that, at the doses that produce antinociceptive effect, choline did not produce any signal of sedation or muscle-relaxation as observed with diazepam used as a positive control (Fig. 2A). We next analyzed whether choline modulates nociception through a central mechanism. The effects of choline on thermal nociception were evaluated with hot-plate test, an assay widely used to investigate supraspinally-organized mechanisms to a noxious stimulus. In fact, choline is a charged cation and cannot easily cross the blood–brain-barrier (Allen and Lockman, 2003). As a positive control, we used morphine (s.c.; 8 mg/kg), which causes a well reported increase in the thermal nociceptive threshold due to its central analgesic mechanism (Fig. 2B). By contrast, treatment with choline did not affect the thermal threshold of mice in the hot-plate test.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of sedative and central analgesic effects of choline. (A) Mice were pretreated with choline (s.c.; 30 mg/kg), diazepam (i.p.; 7.5 mg/kg) (positive control) or vehicle and subjected to Rota-rod test. (B) Mice were pretreated with choline (s.c.; 30 mg/kg), morphine (s.c.; 8 mg/kg) (positive control) or vehicle and subjected to Hot plate test. Sections were performed before and 0.5, 1, 3, and 5 h after treatments. Data are are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05 Two-way ANOVA versus saline group in each time point.

Finally, we also observed that choline did not induce any significant effect even used at high concentrations (10 and 30 mg/kg) in mechanical nociceptive threshold of naïve animals (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that choline does not affect nociception in physiological conditions but reduced pathological inflammatory pain. Furthermore, they indicate that choline specifically modulates nociception through a peripheral mechanism without inducing sedation or motor impairment.

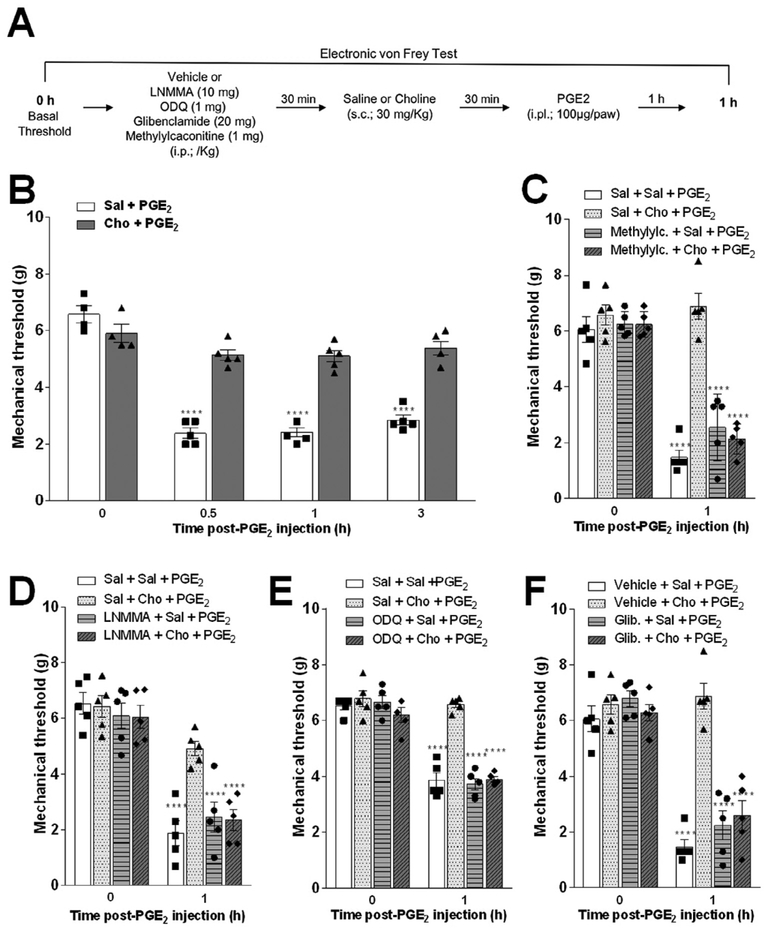

2.3. Choline inhibits PGE2-induced mechanical hyperalgesia by activating the α7nAChRs and NO/cGMP/K+ ATP-sensitive potassium channels

Since choline does not show anti-inflammatory activity, we next investigated whether the antinociceptive effect was due to a direct effect on sensory neurons. Given that the NO-cGMP-KATP channels play a critical role in controlling inflammatory hyperalgesia (Sachs et al., 2004), we reasoned that choline may prevent hyperalgesia by modulating these channels. In order to study this hypothesis, we analyzed whether specific inhibitors of these channels affect the potential of choline to prevent mechanical hyperalgesia induced by PGE2, the main mediator involved in the generation and maintenance of inflammatory pain (Fig. 3A). Treatment with choline reduced the mechanical hyperalgesia induced by intra-plantar (i.pl.) injection of PGE2 (100 μg/paw) (Fig. 3B). Next, we confirmed the specificity of choline on α7nAChRs by using methyllycaconitine, a known α7nAChR antagonist. The pre-treatment with methyllycaconitine abolishesd the anti-nociceptive potential of choline in PGE2-induced mechanical hyperalgesia (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of choline on PGE2-induced hyperalgesia depends on activation of alpha7 nicotinic receptors and NO-cGMP-ATP-sensitive K+ channels pathway. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental protocols. (B) Choline pretreatment prevented the mechanical hyperalgesia elicited by PGE2 (i.pl. 100 μg/ paw) injection 0.5, 1 and 3 h after its administration. Mice were pretreated 30 min with, (C) methyllycaconitine (i.p.; 1 mg/Kg), (D) LNMMA (i.p.; 10 mg/Kg), (E) ODQ (i.p.; 5 μmol/kg) or (F) glibenclamide (i.p.; 20 mg/Kg), (F) before of choline (s.c.; 30 mg/ kg) or vehicle administration. After an additional 30 min, mice received intra-plantar injection of PGE2 stimulus (B-E). Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–5). ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA versus time 0 h (before PGE2 injection) for each group.

The role of the NO-cGMP-KATP channel signaling pathway was analyzed by using standard inhibitors including NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (LNMMA) [intraperitoneal, (i.p.); a non-specific NO synthase inhibitor; 10 mg/kg], IH-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) (i.p.; an inhibitor of soluble guanylate cyclase, 5 μg/kg), or glibenclamide (i.p.; an inhibitor of ATP-sensitive potassium channels; 20 mg/kg) before the choline treatment. Pre-treatment with LNMMA, ODQ or glibenclamide completely abolished the potential of choline to prevent hyperalgesia (Fig. 3D–F). As control, the administration of LNMMA, ODQ or glibenclamide did not affect PGE2-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in the vehicle-treated mice. In summary, these results indicate that choline prevents hyperalgesia by activating the NO-cGMP-KATP channels.

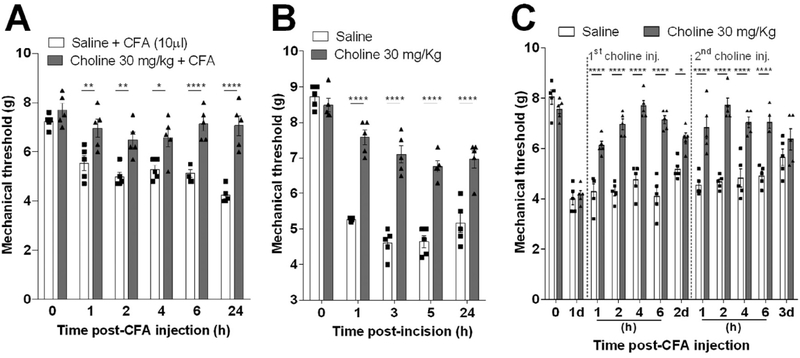

2.4. Choline attenuates long-lasting CFA- and incision-induced hyperalgesia

We next analyzed whether choline can attenuate pain in experimental models of persistent inflammatory mechanical hyperalgesia including long-lasting CFA- or plantar incision-induced inflammatory mechanical hyperalgesia. CFA is known to produce a fast onset and a long-lasting inflammation that elicits allodynia and hyperalgesia, both symptoms of chronic pain. Treatment with choline started 30 min before the CFA intra-plantar injection prevented mechanical hyperalgesia for over 24 h (Fig. 4A). Likewise, treatment with choline also attenuated mechanical hyperalgesia for over 24 h post-surgery in the plantar incision experimental model, a well-established model to study postoperative pain (Fig. 4B). From a more clinical perspective, we also analyzed whether the treatment with choline can be started after the induction of inflammatory hyperalgesia. Treatment with choline attenuates inflammatory hyperalgesia even when the treatment was started 1 or 2 days after the CFA challenge. It induced a robust antinociceptive effect from 1 until 6 h after as compared to vehicle-injected mice (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that the treatment with choline can be started in a clinical relevant time frame after the induction of inflammatory hyperalgesia.

Fig. 4.

Therapeutic effect of choline on chronic CFA and plantar incision-induced mechanical hyperalgesia. Choline (s.c.; 30 mg/Kg) pretreatment effect was assessed when injected 30 min before (A) CFA (i.pl.; 10 μL.) injection or (B) plantar incision model. The mechanical hyperalgesia development was evaluated from 0.5 to 24 h post-CFA injection. Moreover, (C) choline pharmacokinetics effect was evaluated by a single injection 1 and 2 days after CFA mechanical hyperalgesia induction. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ****p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA versus saline-group in each time-point.

3. Discussion

Choline is a well-known precursor in the biosynthesis of acetylcholine and has been studied as a natural occurring agonist of nAChR, mainly α7nAChRs, a key class of receptors connecting the nervous and the immune systems (Wang et al., 2002). These receptors are expressed in neuronal and non-neuronal cells and thus selective α7nAChR-agonists can be used in the modulation of inflammation and nociception (Albuquerque et al., 1997; Alkondon et al., 1997; Damaj et al., 2000; Papke et al., 1996; Parrish et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2005) One of these mechanisms is the “cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway”, in which the vagus nerve controls systemic inflammation in endotoxemic rats (Borovikova et al., 2000). In this circuit, the activation of vagus nerve releases acetylcholine in the mesenteric ganglia to bind to α7nAChRs activating the splenic nerve, which produces norepinephrine in the spleen (Vida et al., 2011). A high concentration of norepinephrine activates splenic T-lymphocytes to produce acetylcholine, which can bind to α7nAChRs expressed on macrophages and inhibit cytokine production (Rosas-Ballina et al., 2011, 2008; Wang et al., 2002). Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that nicotinic agonists inhibit selectively ATP-induced release of IL-lβ in monocytes via interaction of nAChR subunits α7, α9 and α10 suggesting innovative anti-inflammatory therapies without the induction of ionotropic functions of nAChRs (Zakrzewicz et al., 2017). The recent discovery of the neuronal regulation of inflammation via nAChRs is allowing the design of novel therapeutic strategies for inflammatory hyperalgesia. Recently, we reported that the interruption of vagal cholinergic signals increases articular hyperalgesia in arthritic mice (Kanashiro et al., 2016), while another study demonstrated that the treatment with choline prevents nociception in inflammatory pain (Wang et al., 2005). On the other hand, other studies demonstrated that choline showed antinociceptive but not anti-inflammatory effects (Rowley et al., 2010) and that induces α7nAChRs desensitization decreasing their responsiveness to acetylcholine in cultured hippocampal neurons (Alkondon et al., 1997; Papke et al., 1996). Together, these studies suggested that the mechanism(s) of choline in inflammatory hyperalgesia is still not clear.

The establishment of inflammatory hyperalgesia is usually a process divided in two phases. The first inflammatory phase includes the activation of immune cells, mainly neutrophils, to produce nociceptive cytokines/chemokines including TNF, IL-lβ, and KC/CXCCLI. These factors trigger the release of hyperalgesic mediators such as PGE2 that activates specific receptors on the membrane of primary nociceptive neurons (Cunha et al., 2008; Verri et al., 2006). The second phase of inflammatory hyperalgesia includes the sensitization of nociceptors leading to enhanced neuron excitability (Aley and Levine, 1999). Mainly, NSAIDs reduce inflammatory hyperalgesia indirectly by inhibiting the production of inflammatory factors (Ferreira, 1972) and/or preventing the sensitization of primary nociceptive neurons (Ferreira, 1972; Moncada et al., 1975). However, other analgesic drugs such as opioids act on the periphery by directly blocking nociceptors sensitization (Cunha et al., 2010; Duarte et al., 1992; Ferreira et al., 1991). These drugs inhibit PGE2-induced hyperalgesia suggesting that they might restore neuronal function (Alves et al., 2004; Cunha et al., 2010).

We first analyzed the potential of choline to control nociception in the carrageenan-induced hind paw hyperalgesia, a standard model characterized by the production of inflammatory mediators. However, the treatment with choline prevented inflammatory hyperalgesia in carrageenan model without affecting the inflammatory response by a mechanism independent of the “cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway”. In agreement with our results, the systemic treatment of choline showed analgesic effect in a murine model of postoperative pain by a mechanism independent on anti-inflammatory activity as evaluated by TNF production in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Rowley et al., 2010).

A previous study demonstrated that central activation of α7nAChRs with spinal and supra-spinal choline injection prevents nociception in acute thermal pain (Damaj et al., 2000). Herein, the systemic treatment with choline prevents nociception by restoring neuronal function after sensitization caused by PGE2 by a α7nAChRs-dependent mechanism without affecting the central nervous system because PGE2 directly sensitizes the terminals of primary nociceptive neurons and choline is a cationic molecule that does not cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (Allen and Lockman, 2003).

Our group has demonstrated that drugs, such as NSAIDs, dipyrone, and morphine, reverse the already established hyperalgesia induced by PGE2 in rodent hind paws due to the activation of the NO-cGMP-KATP channel signaling pathway in peripheral afferent nociceptors (Cunha et al., 2010; Ferreira et al., 1991; Sachs et al., 2004; Tonussi and Ferreira, 1994). NO, a neuronal messenger in the central and peripheral nervous systems, is produced from L-arginine through three isoforms of NO synthase that has been involved in both inducing and preventing nociception (Cury et al., 2011). NO has been considered a common target for peripheral analgesics that directly block nociceptor sensitization. By contrast, the anti-nociceptive potential of NO is based on the formation of second messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), leading to the activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG), which phosphorylates and opens KATP channels. The activation of these channels leads to a neuron hyperpolarization by increasing K+ influx, and thereby improving nociception and restoring the normal nociceptor threshold (Cunha et al., 2010; Cury et al., 2011). Mechanistically, our present pharmacological data suggest that choline inhibits PGE2-induced hyperalgesia by triggering directly KATP currents in primary nociceptive neurons (Cunha et al., 2010; Distrutti et al., 2006), leading to the hyperpolarization of nociceptors (Cunha et al., 2010). We also demonstrated that the direct effect of choline upon PGE2-induced hyperalgesia is also dependent on α7nAChRs activation. Thus, the important question is whether these two molecular mechanisms are connected. Although we did not have a direct data, there is previous evidence that α7nAChRs are expressed in primary sensory neurons and that activation of these receptors leads to coupling to NO synthase activation and NO production (Haberberger et al., 2003). Nevertheless, we could not discard that different targets could be activated by choline to cause NO pathway activation. For instance, choline can also interact with α3β4nAChRs acting as a partial agonist (Alkondon et al., 1997; Papke et al., 1996). Choline can act in other targets such as muscarinic acetylcholine receptors to exert its biological activities (Damaj et al., 2000). Interestingly, it is important to mention that depending on the exposure time and concentration, choline provokes desensitization of α7nAChRs in neurons decreasing the responsiveness to acetylcholine (Alkondon et al., 1997; Papke et al., 1996). Therefore, further studies will be necessary to address these points.

In addition, we demonstrated that choline also reduces hyperalgesia in two experimental models of persistent pain even when the treatment was started several days after the challenge. Our results are in agreement with previous studies demonstrating the potential of choline to attenuate nociception in clinically relevant models of chronic inflammatory hyperalgesia including both CFA- and nerve incision-induced hyperalgesia (Colpaert, 1987; Ma and Woolf, 1996). CFA-induced hyperalgesia is a widely used experimental model to mimic hyperalgesia in inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (Colpaert, 1987). Arthritis is a debilitating autoimmune disease characterized by chronic joint pain affecting over 1% of the worldwide population. Due to its persistent inflammatory characteristic, paw CFA-induced hyperalgesia is often used to evaluate the pharmacokinetic profile of anti-nociceptive drugs. Our results show that pre-treatment with choline significantly prevents CFA-induced mechanical hyperalgesia. From a more clinical perspective, choline attenuates inflammatory hyperalgesia even when the treatment was started 1 or 2 days after the induction of CFA challenge. Consistent with our findings in chronic pain, recent studies indicate that activation of α7nAChRs by choline significantly attenuates hyperalgesia in osteoarthritis induced by monoiodoacetic acid injection in the rat knee joints (Lee, 2013). Also, α7nAChR-selective agonists can reverse CFA-induced reductions in paw withdrawal thresholds through a potential central mechanism (Medhurst et al., 2008). Moreover, other study showed that α7nAChR-KO mice are more susceptible to hyperalgesia and CFA-induced allodynia and that treatment with nicotine reverses the mechanical allodynia in chronic inflammation and in models of neuropathic pain (AISharari et al., 2013).

Finally, our study shows that treatment with choline prevents mice from plantar incision-induced mechanical hyperalgesia. This surgical traumatic procedure is an optimal model to study post-operative pain enhancing mice response to mechanical stimulus. Optimal pain relief is critical for post-operative recovery and studies have indicated that pain and hyperalgesia after an incision have unique characteristics. These studies suggest that peripheral sensitization, central sensitization, plasticity, and pre-emptive analgesia occur in postoperative pain and it is not responsive to spinal morphine, bupivacaine and excitatory amino acid receptors antagonists administration (Brennan et al., 1996; Zahn et al., 2002). Our results concur with a study showing a significantly slower postoperative recovery in α7nAChR-knockout mice (Rowley et al., 2010). Moreover, other studies have demonstrated the protective effect of α7nAChR agonists in neuropathies induced by traumatic and toxic (chemotherapy) insults. For example, the acute administration of the α7nAChR agonist PNU-282987 protected sciatic nerve fibers from demyelination and axonal damage reducing pain in a model of loose ligation of the sciatic nerve (Pacini et al., 2010). Finally, PNU-282987 also prevented the down-regulation of α7nAChR showing neuroprotective effects in dorsal root ganglia and peripheral nerves altering the glial activating in oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy (Di Cesare Mannelli et al., 2014).

In conclusion, these results in persistent inflammatory pain support the potential clinical use of choline in arthritis or postoperative hyperalgesia, showing the potential of choline to control inflammatory hyperalgesia in multiple models of pain. Treatment with choline attenuates nociception without affecting the immune responses, as other drugs already mentioned, but through other analgesic pathways as, for example, the activation of NO-cGMP-KATP channels. Given the effective potential of choline to control nociception in acute and persistent inflammatory hyperalgesia models, it is suggested that this non-addictive analgesic compound merits further preclinical and clinical investigation.

4. Material and methods

4.1. Animals

Male BALB/c mice weighing 18–22 g were housed in temperature-controlled rooms (22–25 °c) in the animal facility of the Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, and received water and food ad libitum. The study protocols followed the ethical guidelines of the Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo (São Paulo, Brazil). Animal care and handling procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) on the use of animals in pain research, and with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Ribeirao Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo (Process number: 148/2010).

4.2. Chemicals and drugs

Choline, prostaglandin (PGE)-2, complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), LNMMA, ODQ, glibenclamide, methyllylcaconitine, morphine chlorhydrate and diazepam were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Carrageenan was purchased from FMC Corp. (Philadelphia, PA, USA). The drugs were prepared as follows: glibenclamide was dissolved in 1% Tween 20 in saline, PGE2 was dissolved in 2% ethanol in saline, and choline, LNMMA, ODQ, methyllylcaconitine, and diazepam were dissolved in sterile saline. We prepared a choline solution of 6 mg/mL and then injected 100 uL per mouse weighting 20 g (30 mg/kg).

4.3. Inflammatory-induced hyperalgesia models

Carrageenan

In order to investigate the anti-nociceptive effects of choline on inflammatory hyperalgesia, we evaluated the dose-response effects of this drug against carrageenan (Cg)-induced acute mechanical hyperalgesia. The animals were pretreated (30 min before) subcutaneously with choline (s.c.; 3–30 mg/kg) or vehicle (saline) followed by intra-plantar (i.pl.) injection of Cg (100 μg/paw). Mechanical hyperalgesia was determined 3 h (which correspond to the maximal hyperalgesic response produced by Cg) using electronic von Frey (Fig. 1A).

Prostaglandin-E2

In attempting to verify whether choline was able to affect hyperalgesia produced by the direct acting mediator, its effect on PGE2-induced hyperalgesia was also evaluated using electronic von Frey. Moreover, to investigate the activation of NO-cyclic GMP-KATP channels by choline, mice were pretreated with LNMMA, ODQ or glibenclamide 30 min before the subcutaneous choline injection (s.c.; 30 mg/kg) or vehicle administration. After 60 min all groups received i.pl. injection of PGE2 (100 ng/paw). Mechanical hyperalgesia was evaluated 60 min after injection of PGE2 (Fig. 3A). This time point corresponds to the maximal hyperalgesia produced by PGE2 (Cunha et al., 2008). In all experiments, we used i.pl. injection of sterile saline as vehicle (control).

Complete Freund’s Adjuvant

To evaluate the effect of choline on long-lasting mechanical inflammatory hyperalgesia, Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) was injected first (10 μL/paw), after 24 h the animals were treated with choline (s.c.; 30 mg/kg), or vehicle and then mechanical hyperalgesia was evaluated at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 24 h post drugs treatment as described above.

Plantar incision

To assess whether choline had any effect in the mechanical hyperalgesia induced by postoperative incisional pain model, mice were anesthetized with 1.5 to 2% isoflurane inhalation. After the antiseptic procedure of the right hind paw with 10% povidone-iodine solution, a 5 mm longitudinal incision was made with a number 11 surgical blade through the skin and fascia of the plantar surface. The incision was started 2 mm from the proximal edge of the heel and extended toward the toes. The underlying muscle was elevated with a curved forceps, leaving the muscle origin and insertion intact. The skin was apposed with a single mattress suture of 6–0 silk on a G-1 needle (786G; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), and the wound was cleaned with 10% povidone-iodine solution once more. The suture was removed at the end of post-operative day 2. Control mice underwent a sham procedure that consisted of anesthesia, antiseptic preparation, and topical antibiotics without an incision (Pogatzki and Raja, 2003).

4.4. Evaluation of mechanical hyperalgesia

Mechanical hyperalgesia was tested by electronic von Frey test as previously reported (Cunha et al., 2004). Briefly, in a quiet room, mice were placed in acrylic cages (12 × 20 × 17 cm) with wire grid floors, 15–30 min before the start of the test. The test consisted of evoking a hind paw flexion reflex with a hand-held force transducer adapted with a 0.5-mm2 polypropylene tip for mice (Electronic von Frey; IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA, USA). A tilted mirror placed under the grid provided a clear view of the mice hind paw. The investigator was trained to apply the tip in between the five distal footpads with a gradual increase in pressure. The stimulus was automatically discontinued, and its intensity recorded when the paw was withdrawn. The end-point was characterized by the removal of the paw in a clear flinch response after paw withdrawal. The animals were tested before and after treatments. A different investigator performed each test, as was the case in the preparation of solutions and treatment of the animals. Behavioral tests were performed on animals in a randomized order in a blind fashion in which the person who performed the treatments was not the same as one who made the behavioral assessment. The results are expressed by the mechanical threshold (in grams, g).

4.5. Myeloperoxidase activity determination

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was utilized as an indirect marker of neutrophil recruitment into the plantar paw tissue, based on a kinetic-colorimetric assay described previously (Bradley et al., 1982). In brief, samples were collected in K2HPO4 buffer (50 mmol/L; pH 6.0) containing 0.5% hexadecyl trimethylammonium bromide and frozen at − 80 °c. In the day of the assay, the tissue was homogenized using a Polytron (PT3100) and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 4 min. In low pH, the MPO assay detects only the activity of neutrophils. To prepare the solution for the analysis, 5 μL of the supernatant was mixed with 200 μL of phosphate buffer (50 mmol/L; pH 6.0), containing O-dianisidine dihydrochloride (0.167 mg/mL) and hydrogen peroxide (0.0005%). The solution was analyzed by spectrophotometry at 450 nm (Spectra max, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale CA, USA) and the MPO activity was compared with a standard curve of neutrophils obtained from mice isolated from blood. The results were shown as number of neutrophils × 106/mg tissue.

4.6. Cytokines/Chemokine quantification

The paw tissue were triturated and homogenized in buffer containing protease inhibitors at different time points. The concentrations of the cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1 beta (IL-lβ), and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC/CXCL1) were determined as previously described by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The results are expressed as pg/paw of each cytokine.

4.7. Rota-rod test

To exclude possible nonspecific muscle relaxant or sedative effects of choline, animals were treated with vehicle, choline (s.c.; 30 mg/kg) or diazepam (i.p.; 7.5 mg/kg) and submitted to a motor performance using the rota-rod test 1.5, 3.5, and 5.5 h after the treatments. The rota-rod apparatus consists of a bar with a diameter of 2.5 cm, subdivided into six compartments by disks 25 cm in diameter (Ugo Basile, model 7600). The bar rotated at a constant speed of 22 rotations per min. The animals were selected 24 h previously by eliminating those mice that did not remain on the bar for two consecutive periods of 120 s. The cutoff time used was 120 s.

4.8. Hot plate test

In order to exclude possible central mechanism effect of choline, mice treated with vehicle, choline (s.c.; 30 mg/kg) or morphine (s.c; 8 mg/kg) and placed in a 10 cm wide glass cylinder on a hot plate (IITC Life Science, Inc., Woodland Hills, CA, USA) maintained at 55 °c. Two control latencies at least 10 min apart were determined for each mouse. The typical latency (reaction time) was 5–9 s. The latency was also evaluated 1.5, 3.5, and 5.5 h after test compound administration. The reaction time was scored when the animal jumped or licked its paws.

4.9. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of 4–5 animals per group. Differences between the experimental groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and individual comparisons were subsequently made with Tukey’s post hoc test. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare the groups when the hypernociceptive responses were measured at different times after the stimulus injection using GraphPad Prism Software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Choline inhibits carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia but not inflammatory events.

Choline inhibits PGE-2 induced hyperalgesia via NO/cGMP/ATP K + channels pathway.

Choline attenuates long-lasting CFA- and incision-induced hyperalgesia.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; grants 13/08216-2, 12/23846-0, 11/20343-4, and 10/16823-8) and from National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; 118636/2017-0).

Abbreviations

- α7nAChR

alpha 7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CFA

complete Freund’s Adjuvant

- Cg

carrageenan

- KC/CXCL1

keratinocyte-derived chemokine

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- IL-lβ

interleukin-lβ

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.pl.

intra-plantar

- LNMMA

NG monomethyl-L-arginine

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NF-κB

factor nuclear kappa B

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- NO

nitric oxide

- ODQ

IH-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-l-one

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Albuquerque EX, Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Castro NG, Schrattenholz A, Barbosa CT, Bonfante-Cabarcas R, Aracava Y, Eisenberg HM, Maelicke A, 1997. Properties of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: pharmacological characterization and modulation of synaptic function. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut 280, 1117–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aley KO, Levine JD, 1999. Role of protein kinase A in the maintenance of inflammatory pain. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci 19, 2181–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Cortes WS, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX, 1997. Choline is a selective agonist of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rat brain neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci 9, 2734–2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DD, Lockman PR, 2003. The blood-brain barrier choline transporter as a brain drug delivery vector. Life Sci. 73, 1609–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlSharari SD, Freitas K, Damaj MI, 2013. Functional role of alpha7 nicotinic receptor in chronic neuropathic and inflammatory pain: Studies in transgenic mice. Biochem. Pharmacol 86, 1201–1207. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves DP, Tatsuo MAF, Leite R, Duarte IDG, 2004. Diclofenac-induced peripheral antinociception is associated with ATP-sensitive K+ channels activation. Life Sci. 74, 2577–2591. https://doi.org/l0.10l6/j.lfs.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR., Wang H, Abumrad N, Eaton JW, Tracey KJ, 2000. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature 405, 458–462. 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley PP, Priebat DA, Christensen RD, Rothstein G, 1982. Measurement of cutaneous inflammation: estimation of neutrophil content with an enzyme marker. J. Investigat. Dermatol 78, 206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF, 1996. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain 64, 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC, 1987. Evidence that adjuvant arthritis in the rat is associated with chronic pain. Pain 28, 201–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha TM, Roman-Campos D, Dias QM, Schivo IR, Domingues AC, Sachs D, Chiavegatto S, Teixeira MM, Hothersall J.s., Cruz J.s., Cunha FQ, Ferreira s.H., 2010. Morphine peripheral analgesia depends on activation of the P13K /AKT/nNOS/NO/KATP signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 107, 4442–4447. 10.1073/pnas.0914733107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha TM, Verri WA, Schivo IR, Napimoga MH, Parada CA, Poole S, Teixeira MM, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ, 2008. Crucial role of neutrophils in the development of mechanical inflammatory hypernociception. J. Leukoc. Biol 83, 824–832. 10.1189/j1b.0907654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha TM, Verri WA, Silva J.s., Poole S, Cunha FQ, Ferreira, s.H., 2005. A cascade of cytokines mediates mechanical inflammatory hypernociception in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. sci 102, 1755–1760. 10.1073/pnas.0409225102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha TM, Verri w.A., Vivancos GG, Moreira IF, Reis S, Parada CA, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH, 2004. An electronic pressure-meter nociception paw test for mice. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research =. Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas 37, 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cury Y, Picolo G, Gutierrez VP, Ferreira SH, 2011. Pain and analgesia: The dual effect of nitric oxide in the nociceptive system. Nitric Oxide 25, 243–254. 10.1016/j.niox.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI, Meyer EM, Martin BR, 2000. The antinociceptive effects of alpha7 nicotinic agonists in an acute pain model. Neuropharmacology 39, 2785–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MW, Meyer MD, Sullivan JP, 2001. The therapeutic potential of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists for pain control. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 10, 1819–1830. 10.1517/13543784.10.10.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cesare Mannelli L, Pacini A, Matera C, Zanardelli M, Mello T, De Amici M, Dallanoce C, Ghelardini C, 2014. Involvement of α7 nAChR subtype in rat oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: effects of selective activation. Neuropharmacology 79, 37–48. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distrutti E, Sediari L, Mencarelli A, Renga B, Orlandi S, Antonelli E, Roviezzo F, Morelli A, Cirino G, Wallace JL, Fiorucci S, 2006. Evidence that hydrogen sulfide exerts antinociceptive effects in the gastrointestinal tract by activating KATP channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut 316, 325–335. 10.1124/jpet.105.091595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte ID, dos Santos IR, Lorenzetti BB, Ferreira SH, 1992. Analgesia by direct antagonism of nociceptor sensitization involves the arginine-nitric oxide-cGMP pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol 217, 225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SH, 1972. Prostaglandins, aspirin-like drugs and analgesia. Nature: New biology 240, 200–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SH, Duarte ID, Lorenzetti BB, 1991. The molecular mechanism of action of peripheral morphine analgesia: stimulation of the cGMP system via nitric oxide release. Eur. J. Pharmacol 201, 121–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CM, 2000. The promise and pitfalls of a nicotinic cholinergic approach to pain management. Pain 88, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberberger RV, Henrich M, Lips KS, Kummer W, 2003. Nicotinic receptor alpha 7-subunits are coupled to the stimulation of nitric oxide synthase in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Histochem. Cell Biol 120, 173–181. 10.1007/s00418-003-0550-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanashiro A, Talbot J, Peres R.s., Pinto LG, Bassi G.s., Cunha TM, Cunha FQ, 2016. Neutrophil recruitment and articular hyperalgesia in antigen-induced arthritis are modulated by the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol 119, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.llll/bcpt.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, 2013. Choline, an alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, alleviates hyperalgesia in a rat osteoarthritis model. Neurosci. Lett 548, 291–295. 10.1016/j.neu1et.2013.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes SC, da Silva AVL, Arruda BR, Morais T.c., Rios JB, Trevisan MTS, Rao VS, Santos FA, 2013. Peripheral antinociceptive action of mangiferin in mouse models of experimental pain: role of endogenous opioids, K(ATP)-channels and adenosine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behavior 110, 19–26. 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QP, Woolf CJ, 1996. Progressive tactile hypersensitivity: an inflammation-induced incremental increase in the excitability of the spinal cord. Pain 67, 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst SJ, Hatcher JP, Hille CJ, Bingham S, Clayton NM, Billinton A, Chessell IP, 2008. Activation of the alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor reverses complete freund adjuvant-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in the rat via a central site of action. J. Pain: Off. J. Am. Pain Soc 9, 580–587. 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.01.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Ferreira SH, Vane JR, 1975. Inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis as the mechanism of analgesia of aspirin-like drugs in the dog knee joint. Eur. J. Pharmacol 31, 250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacini A, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Bonaccini L, Ronzoni S, Bartolini A, Ghelardini C, 2010. Protective effect of alpha7 nAChR: behavioural and morphological features on neuropathy. Pain 150, 542–549. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Bencherif M, Lippiello P, 1996. An evaluation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation by quaternary nitrogen compounds indicates that choline is selective for the alpha 7 subtype. Neurosci. Lett 213, 201–204. 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish W, Rosas-Ballina M, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani M, Ochani K, Yang L-H, Hudson L, Lin X, Patel N, Johnson SM, Chavan S, Goldstein RS, Czura CJ, Miller EJ, Al-Abed Y, Tracey KJ, Pavlov VA, 2008. Modulation of TNF release by choline requires alpha7 subunit nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated signaling. Mol. Med 14, 1 10.2119/2008-00079.Parrish. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Caldarone BJ, King SL, Zachariou V, 2000. Nicotinic receptors in the brain. Links between molecular biology and behavior. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publicat. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol 22, 451–465. 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogatzki EM, Raja SN, 2003. A mouse model of incisional pain. Anesthesiology 99, 1023–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Parrish WR, Ochani K, Harris YT, Huston JM, Chavan S, Tracey KJ, 2008. Splenic nerve is required for cholinergic antiin-flammatory pathway control of TNF in endotoxemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 105, 11008–11013. 10.1073/pnas.0803237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Pavlov VA, Andersson U, Chavan S, Mak TW, Tracey KJ, 2011. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 334, 98–101. 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley TJ, McKinstry A, Greenidge E, Smith W, Flood P, 2010. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of choline in a mouse model of postoperative pain. Br. J. Anaesthesia 105, 201–207. 10.1093/bja/aeq113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs D, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH, 2004. Peripheral analgesic blockade of hypernociception: Activation of arginine/NO/cGMP/protein kinase G/ATP-sensitive K + channel pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 101, 3680–3685. https://doi.org/l0.1073/pnas.0308382101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonussi CR, Ferreira SH, 1994. Mechanism of diclofenac analgesia: direct blockade of inflammatory sensitization. Eur. J. Pharmacol 251, 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verri WA, Cunha TM, Parada CA, Poole S, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH, 2006. Hypernociceptive role of cytokines and chemokines: Targets for analgesic drug development? Pharmacol. Ther 112, 116–138. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida G, Peña G, Deitch EA, Ulloa L, 2011. α7-Cholinergic Receptor Mediates Vagal Induction of Splenic Norepinephrine. J. Immunol 186, 4340–4346. 10.4049/jimmun01.1003722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, Li JH, Wang H, Yang H, Ulloa L, Al-Abed Y, Czura c.J., Tracey KJ, 2002. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor a7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature 421, 384–388. 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Su D-M, Wang R-H, Liu Y, Wang H, 2005. Antinociceptive effects of choline against acute and inflammatory pain. Neuroscience 132, 49–56. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn PK, Pogatzki EM, Brennan TJ, 2002. Mechanisms for pain caused by incisions. Regional Anesth. Pain Med 27, 514–516. 10.1053/rapm.2002.35155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewicz A, Richter K, Agné A, Wilker S, Siebers K, Fink B, Krasteva-Christ G, Althaus M, Padberg W, Hone AJ, McIntosh JM, Grau V, 2017. Canonical and novel non-canonical cholinergic agonists inhibit ATP-induced release of monocytic interleukin-lβ via different combinations of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits α7, α9 and αl0. Front. Cell. Neurosci 11 10.3389/fncel.2017.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]