Abstract

Background

The astrocytic phospholipase A2 (PLA2)-arachidonic acid (AA) pathway is crucial in understanding the reduction of cerebral blood flow (CBF) prior to cognitive deterioration. In complementary and alternative medicine, manual acupuncture (MA) is used as one of the most important therapies for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The beneficial effects of MA on CBF were reported in our previous study. However, the underlying molecular mechanism remains largely elusive.

Objective

To investigate the effect of MA on the astrocytic PLA2-AA pathway in SAMP8 mice hippocampi.

Methods

SAMP8 mice were divided into the SAMP8 control (Pc) group, the SAMP8 MA (Pm) group and the SAMP8 donepezil (Pd) group. SAMR1 mice were used as the SAMRl control (Rc) group. Mice in the Pd group were treated with donepezil hydrochloride at 0.65 μg/g. In the Pm group, MA was applied at Baihui (GV20) and Yintang (GV29) for 20 min. The above treatments were administered once a day for 26 consecutive days. The Morris water maze was applied to assess spatial learning and memory. Immunofluorescence staining, western blot and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry were used to investigate the expression of related proteins and measure the contents of the metabolic intermediates of the PLA2-AA pathway.

Results

Compared with that in the Rc group, the escape latency in the Pc group significantly increased (p < 0.01); whereas, the platform crossover number and percentage of time and swimming distance in the platform quadrant decreased (p < 0.01). The hippocampal expression of PLA2, cyclooxygenase-1, cytochrome P450 proteins 2C23 and the levels of AA, prostaglandin E2 and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids of the Pc group was drastically higher than that in the Rc group (p < 0.01). These changes were reversed by MA and donepezil (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05).

Conclusion

MA can effectively improve the learning and memory abilities of SAMP8 mice and has a negative regulatory effect on the PLA2-AA pathway. We propose that the increase of the arterial tone, which is induced by the inhibition of vasodilatory pathway, may be a reason for the beneficial effect of MA on CBF.

Keywords: manual acupuncture, Alzheimer’s disease, astrocyte, hippocampus, phospholipase A2, arachidonic acid, cerebral blood flow

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system, characterized by a progressive loss of memory and a cognitive impairment. The main clinical manifestations include memory disorders, aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, loss of discernment capacity, and personality and behavioral changes. As the most common cause of dementia, AD accounts for 60–70% of patients with dementia (Di Marco et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016) and is a highly prevalent disease, that has a high morbidity rate and high medical costs. Research shows that the global estimates of costs for dementia will be US $2.54 trillion in 2030 and US $9.12 trillion in 2050 (Jia et al., 2018). With the aging of population, the increasingly heavy financial and social burden imposed by AD, renders it a public health problem that require urgent solutions (Jones et al., 2017; Lane et al., 2018).

The pathogenesis of AD is thought to be a complex process associated with amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition, tau phosphorylation, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Among the pathological changes, cerebral vascular dysfunction plays an important role in AD early onset and development (Marchesi, 2011; Lourenco et al., 2017; Bennett et al., 2018). A series of imaging studies indicated that the cerebral blood flow (CBF) is significantly changed in AD patients (Okonkwo et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015; van de Haar et al., 2016). As the first step in AD development, a decrease in CBF occurs before the appearance of clinical symptoms, which suggests its potential inducing role of AD pathological changes, including the expression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and tau phosphorylation (Koike et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Salminen et al., 2017). These sustained CBF changes have been associated with cognitive impairment (Hanyu et al., 2010; Leeuwis et al., 2017; Nielsen et al., 2017), and are disease specific (Abdi et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013; Le Heron et al., 2014) that precede the other AD clinical symptoms (Hays et al., 2016). CBF reduction is a sensitive marker of AD early perfusion disorders (Lacalle-Aurioles et al., 2014). In particular, ischemia and anoxia, that are caused by a CBF decrease, can directly induce neuronal injury, synaptic dysfunction and promote Aβ accumulation by elevating the expression of the APP and reducing Aβ clearance. These events result in neural injuries and neurological disorders, that start the neurodegenerative process (Zlokovic, 2011; Sagare et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2016). This compelling evidence suggests that the abnormality of the cerebrovascular function is one of the basic pathological changes and the key point of AD pathogenesis (Jellinger, 2008; Kelleher and Soiza, 2013).

Additionally, neurovascular injuries and dysfunctions of their signaling networks play a pivotal role in CBF reduction (Kuchibhotla et al., 2009; Iadecola, 2013; Delekate et al., 2014). For instance, astrocytes are of crucial importance for the cerebral hemodynamic stability and regulation and are also an essential factor in neurovascular coupling (McCaslin et al., 2011; Tarantini et al., 2017). The neurotransmitter pathway, mediated by glutamate, can promote calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in astrocytes increased intracellular calcium (Attwell et al., 2010). Calcium fluxes initiate the phospholipase A2 (PLA2)-arachidonic acid (AA) pathway (Zonta et al., 2003). PLA2 plays a key part in CBF molecular mechanism by regulating the vascular pathway (He et al., 2012). When the intracellular PLA2 is activated, membrane phospholipids are hydrolyzed into AA (Yagami et al., 2014; Leslie, 2015), which can further transform into related metabolic intermediates under the action of related enzymes. Through the COX, CYP2C, and CYP2J pathways, AA can be further transformed into PGE2 and EETs (Spector, 2009; Powell and Rokach, 2015). The vasoactive substances PGE2 and EETs can activate the potassium channels in the vascular smooth muscle cells after release from astrocytes end foot, resulting in vasodilatation and CBF increase (Attwell et al., 2010; Howarth, 2014; Zhang H. et al., 2017). These neurovascular pathways are crucial in understanding the neuropathic cascades that precede cognitive deterioration and dementia development (de la Torre, 2010), and have therefore, the potential to become new therapeutic targets in AD treatment (Zlokovic, 2005; van Norden et al., 2012; Acosta et al., 2017).

As one of the most important therapies in complementary and alternative medicine, acupuncture plays an active role in the clinical efforts against AD. Acupuncture can noticeably improve cognitive function and the quality of life of AD patients, by providing reduced side effects and safety (Zhou et al., 2015, 2017; Jia et al., 2017). Acupuncture is effective in improving the sleep quality of elderly patients with dementia (Kwok et al., 2013; Simoncini et al., 2015). Studies have partially clarified the mechanisms by which acupuncture can prevent AD through anti-inflammatory (Ding et al., 2017), anti-oxidative (Sutalangka et al., 2013), and anti-apoptotic effects (Guo et al., 2015, 2016). Moreover, acupuncture can modulate the functional activity and connectivity of specific cognition-related areas of the brain in AD patients (Wang et al., 2012, 2014; Liang et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2018). However, the effect of manual acupuncture (MA) on CBF in AD therapy and the specifics of its molecular mechanisms are still not well known. Our previous study showed, for the first time, that MA can effectively enhance CBF in the prefrontal lobes and hippocampi of senescence-accelerated prone 8 (SAMP8) mice by MRI. We proposed that CBF increase could be an important mechanism of MA beneficial cognitive effects in AD (Ding et al., 2019). Considering that CBF plays a central role in AD pathogenesis and development, it is vital to determine how acupuncture can impact CBF regulation in an AD model. However, the underlying molecular mechanism remains largely elusive. This issue further limits our understanding of MA therapeutic mechanism in AD, and delays the optimization of an MA clinical protocol, since the reduction of CBF, is a sensitive marker to AD early perfusion disorders. Therefore, the moderating effect of MA on the underlying molecular mechanism of CBF regulation requires additional studies.

As an important in vivo model in senescence-accelerated proneness, SAMP8 mice present age-related cognitive deterioration (Griñan-Ferré et al., 2016; Akiguchi et al., 2017) and show pathological features similar to the mechanisms responsible for AD pathophysiology, such as oxidative stress, APP overexpression, Aβ deposition and tau phosphorylation (Li et al., 2013; Bayod et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2014). SAMP8 is a good animal model to investigate the fundamental mechanisms of age-related learning and memory deficits and is widely used for studying early neurodegenerative changes, associated with AD (Butterfield and Poon, 2005; Manich et al., 2011; Griñán-Ferré et al., 2018). This study assessed changes in SAMP8 mice hippocampal neurovascular pathway and compared them to the normal aging process in the control senescence-accelerated resistant 1 (SAMR1) mice (Takeda, 2009). Using the Morris water maze (MWM) test, immunofluorescence (IF) staining, western blot (WB), and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), we aimed at elucidating the effect of MA on the astrocytes PLA2-AA pathway. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study, that focused on the underlying mechanism of CBF response after MA treatment in AD. Our data greatly contribute to unraveling the scientific basis of MA in AD treatment and further identify the effectiveness of MA in improving cognitive ability.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Male SAMP8 and male SAMR1 mice were purchased from the Zhi Shan (Beijing) Academy of Medical Science and tested by Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences [Animal Lot: SCXK (Jing) 2014-0011]. Both types of mice weighed 30.0 ± 2.0 g and were 8 months old. The animals were housed in the Experimental Animal Center of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine at a controlled temperature (24 ± 2°C) and under a 12-h dark/light cycle, with sterile drinking water and a standard pellet diet available ad libitum. All mice were acclimatized to the environment for 7 days prior to experimentation. Efforts were made to minimize the number of animal uses and the suffering of the experimental animals.

Animal Grouping and Intervention

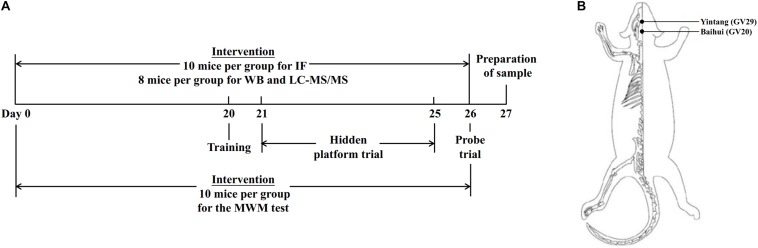

Eighty-four SAMP8 mice were divided into three groups (n = 28 per group): the SAMP8 control (Pc) group, the SAMP8 manual acupuncture (Pm) group and the SAMP8 donepezil (Pd) group. Twenty-eight SAMR1 mice were used as the control group (Rc). The timeline of the experimental design and the mouse applied acupoints locations are presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of experimental design and mouse acupoint locations. (A) The timeline of experimental design. (B) Illustrated diagram of GV29 and GV20 in the mouse. GV20 is at the midpoint between the auricular apices, and GV29 is located midway between the medial ends of the two eyebrows.

In the Pm group, the mice were immobilized in mouse bags. Disposable sterile acupuncture needles (0.25 mm × 13 mm) (Beijing Zhongyan Taihe Medicine Company, Ltd) were used. MA at Baihui (GV20) and Yintang (GV29) was applied for 20 min, with transverse puncturing at a depth of 2–3 mm. During the MA at GV20 and GV29, twirling manipulation was applied every 5 min for 15 s each time. Each needle was rotated bidirectionally within 90° at a speed of 180°/s. For the Pd group, donepezil hydrochloride tablets (Eisai China Inc, H20050978) were crushed and dissolved in distilled water and were delivered to mice by oral gavage at a dose of 0.65 μg/g (Geerts et al., 2005; Ding et al., 2017, 2019). The above treatments were administered once a day for 26 consecutive days, but no treatment was carried out in the Pc or Rc groups. The mice in the Rc, Pc, and Pd groups received the same 20 min restriction as the Pm group. The above intervention lasted throughout the Morris water maze test period.

The selection of the acupoints was based on findings from our previous studies; namely, the therapeutic principle of dredging DU meridian and lighting mind (Jiang et al., 2015, 2016, 2018; Cao et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2019). According to the traditional meridian theory, the DU meridian connects to the brain and is closely associated with all mental activities. Therefore, MA at GV20 and GV29, the important acupoints in the DU meridian, has a benign regulative effect on the DU meridian and is conducive to light mind, which is applicable for AD.

MWM Test

Ten mice in each group were selected randomly for the MWM test on day 21. To assess the ability of spatial learning and memory, the hidden platform trial and probe trial were conducted in order. The MWM we used in this study has been described previously (Ding et al., 2019).

Hidden Platform Trial

All mice used for the MWM test were made to carry out swim training for 1 min in the maze on day 20 of the intervention. On day 21, the hidden platform trial was performed. The platform was positioned in the middle of the SW quadrants. Mice were given a series of daily trials using a semirandom set of start locations. The four start locations were used with the restriction that one trial each day was from each of the four positions. Each mouse was released from one of four start locations and had 60 s to search for the hidden platform. At the end of each trial, the mouse was placed on the platform or allowed to stay there for 10 s. Four trials per day were performed for 5 consecutive days, with the visual cues kept constant. The escape latency was collected for subsequent analysis.

Probe Trial

To assess reference memory, the probe trial was conducted on day 26. The platform was removed, and each mouse was placed in the pool once for 60 s. The starting direction farthest from the platform quadrant was used in the hidden platform trial. The swimming distances in the maze were recorded, and the platform crossover number, swimming speed, and percentage of the time and swimming distance in the platform quadrant were analyzed using EthoVision (3.1.16, Noldus).

IF Staining

On day 27, 10 mice in each group were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (80 mg/kg body weight) and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2.5 h, and dehydrated by 20 and 30% sucrose for 24 h each. Frozen 5-μm sections were sliced by a freezing microtome (CM1900, Leica Corporation, Germany) at −20°C. The primary antibodies included the goat polyclonal GFAP antibody (1:100, Abcam, United States), the rabbit polyclonal PLA2 antibody (1:100, Abcam, United States), the rabbit monoclonal COX-1 antibody (1:100, Abcam, United States), and the rabbit polyclonal CYP2C23 antibody (1:100, USBio, United States). Donkey anti-goat IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200, Abcam, United States), and donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 594 (1:200, Abcam, United States) were used as corresponding secondary antibodies. The 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, Solarbio, China) was applied for counterstaining. For double immunohistochemical staining, the sections were washed in 0.1 M PBS (pH = 7.4) and blocked in 0.1 M PBS (pH = 7.4) containing 10% normal donkey serum and 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Next, the sections were treated with GFAP antibody and PLA2 antibody and incubated overnight at 4°C. After PBS washes, the sections were exposed to secondary antibodies for 2 h. Subsequently, the sections were washed with PBS and stained with DAPI for 5 min. After washing with PBS, the sections were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1200, Olympus Corporation, Japan). Double immunohistochemical staining using the same staining protocol was undertaken to examine the coexpression of GFAP and COX-1, GFAP and CYP2C23.

Identical exposure times and image settings were used for each experiment. For each specimen, six images of the hippocampus were captured at 100× magnification for quantification. All images were analyzed using ImageJ. The astrocytes in the hippocampus were defined based on GFAP and were outlined “freehand.” The mean optical density of the six images was calculated. The mean optical densities of PLA2, COX-1, and CYP2C23 in astrocytes of the hippocampus were compared in each group.

WB Analysis

On day 27, 8 mice in each group were euthanized by an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg body weight) to harvest their hippocampi. Right hippocampi were used for WB analysis. After homogenate and protein extraction, SDS-PAGE was performed with a 8% separating gel and a 5% stacking gel and transferred to a 0.45 μm PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked using 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20. The primary antibody (PLA2, 1:500, Abcam, United States; COX-1, 1:1000, Abcam, United States; CYP2C23, 1:1000, USBio, United States; beta-actin, 1:500, Bioss, United States) was added, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibody (goat polyclonal rabbit IgG antibody-HRP, 1:3000, Bioss, United States) was added before shaking and incubation at room temperature for 1 h. HRP-ECL luminous liquid was added, and X-ray film exposure was completed in a dark room following developing and fixing. After calibrating the control markers, the scanning and analysis were performed by Quantity One. All western blot bands were normalized with their corresponding β-actin expression (loading control), for the appropriate evaluation of protein expressions. The relative expression of PLA2, COX-1, and CYP2C23 was compared in each group.

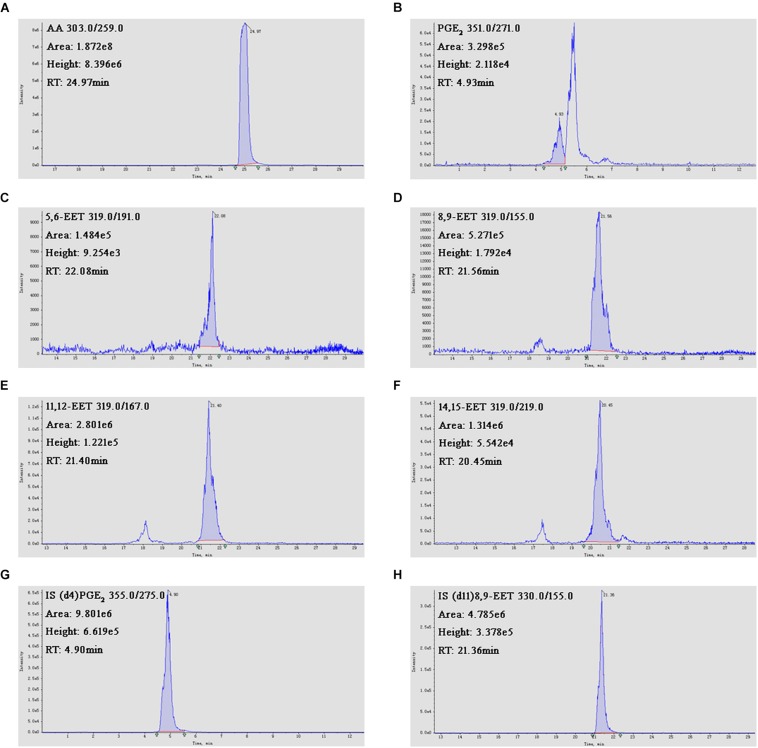

LC-MS/MS

On day 27, 8 mice in each group were euthanized by an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg body weight) to harvest their hippocampus. Left hippocampi were used for LC-MS/MS analysis. After being weighed, the tissues were homogenized with 500 μL of methanol (2% formic acid and 0.01 mol/L BHT) spiked with internal standards from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI, United States) (5 ng each of PGE2-d4 and 8,9-EET-d11). After centrifugation (12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C), the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. Water (700 μL) and ethyl acetate (1 mL) were added to the supernatant. The sample was mixed vigorously for 2 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 g. The upper organic phase was transferred to a new tube, and the water phase was extracted again. The organic phase was combined and then evaporated to dryness. The dried residue was dissolved in 100 μL of 30% acetonitrile. An ultraperformance liquid chromatograph (ACQUITY, Waters, United States) and hybrid triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (QTRAP 5500, AB Sciex, Foster City, CA, United States) were used. The quantitative method and conditions for LC-MS/MS were consistent with Zhang et al. (2015). All data were processed using MultiQuant v.2.1 (AB Sciex). The contents of AA, PGE2, 5,6-EET, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET, and 14,15-EET were compared between groups.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software, version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), and the data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used to analyze group differences in the hidden platform trial. A one-way ANOVA followed by the LSD multiple-range test was used to analyze group differences in the probe trial and during PLA2-AA pathway activation. For the non-normally distributed data or data with heterogeneous variance, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. The statistical significance was set to p < 0.05 and a high statistical significance was set to p < 0.01.

Results

Effect of MA on Spatial Learning and Memory

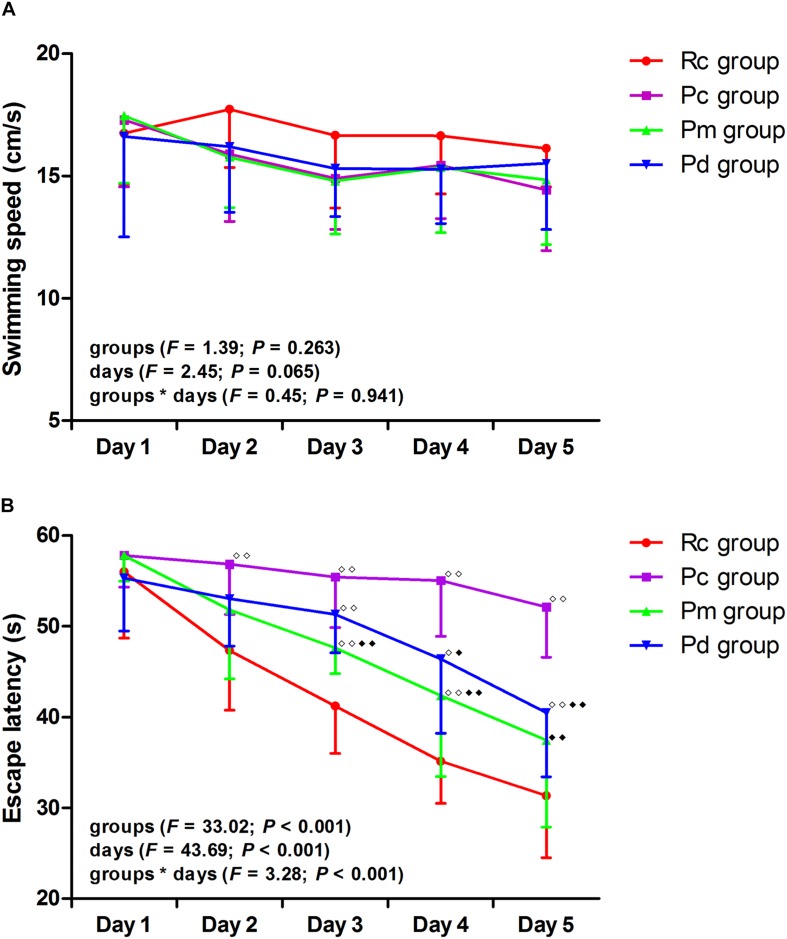

The results of the MWM test are presented in Figures 2, 3. In the hidden platform trial, there was no significant difference in the escape latency among groups on day 1. The escape latency of the Rc, Pm, and Pd groups gradually decreased, but the Pc group maintained a high value. From days 2–5, the escape latency was significantly higher in the Pc group than in the Rc group (p < 0.01). The escape latency in the Pm and Pd groups was drastically lower than in the Pc group on days 3–5 and days 4–5, respectively (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05). Compared with that in the Rc group, the escape latency in the Pm and Pd groups was significantly higher on days 3–4 and days 3–5, respectively (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05). In the probe trial, the platform crossover number and the percentage of time and swimming distance in the platform quadrant in the Pc group, were drastically lower than in the Rc group (p < 0.01). In the Pm and Pd groups, the platform crossover number and percentage of time and swimming distance in the platform quadrant, markedly increased compared with those in the Pc group (p < 0.01); whereas, the platform crossover number was still lower than those in the Rc group (p < 0.01). There were no significant group differences in the swimming speed in the hidden platform or probe trial.

FIGURE 2.

Results of the hidden platform trial in each group (n = 10, mean ± SD). (A,B) Comparison between the swimming speed and escape latency of all groups. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used. LSD-t was presented in Supplementary Table 1. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆P < 0.05 compared with the Rc group. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆P < 0.05 compared with the Pc group.

FIGURE 3.

Results of the probe trial in each group (n = 10, mean ± SD). (A–D) Comparison between the platform crossover numbers, the percentage of time and swimming distances in the SW quadrant, and the swimming speed of all groups. A one-way ANOVA followed by the LSD multiple-range test was used with an exception when comparing the platform crossover numbers, which was analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test. LSD-t and Chi-Square are presented in Supplementary Tables 2, 3. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆◆P < 0.01.

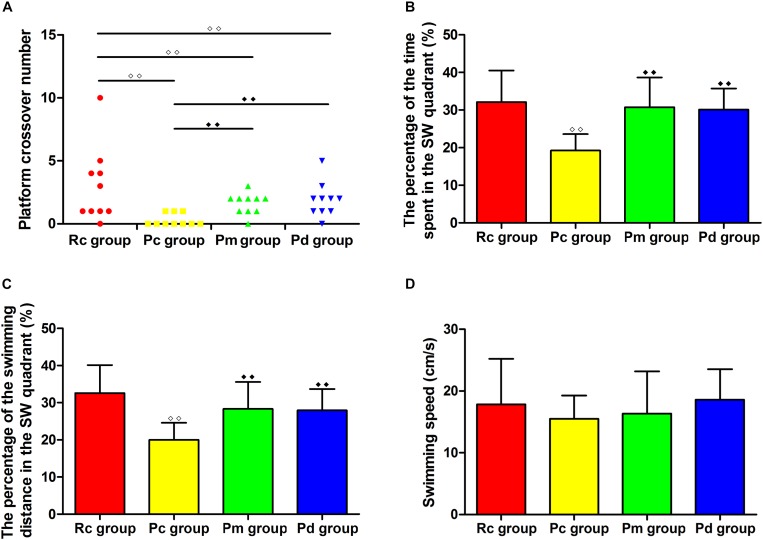

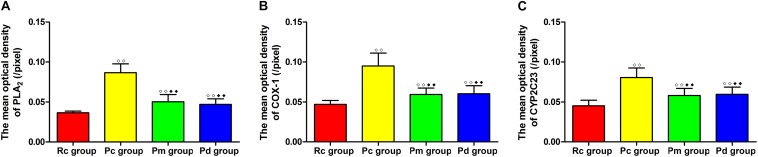

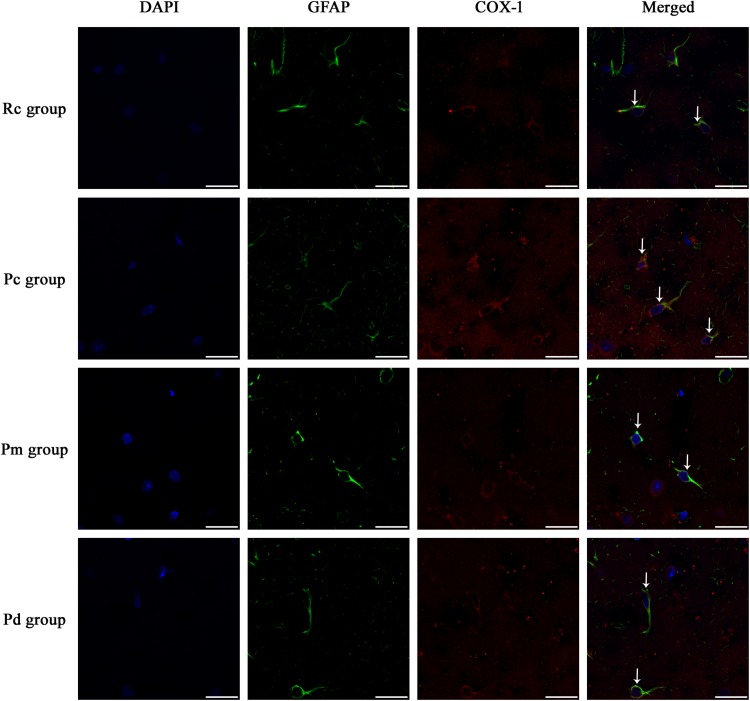

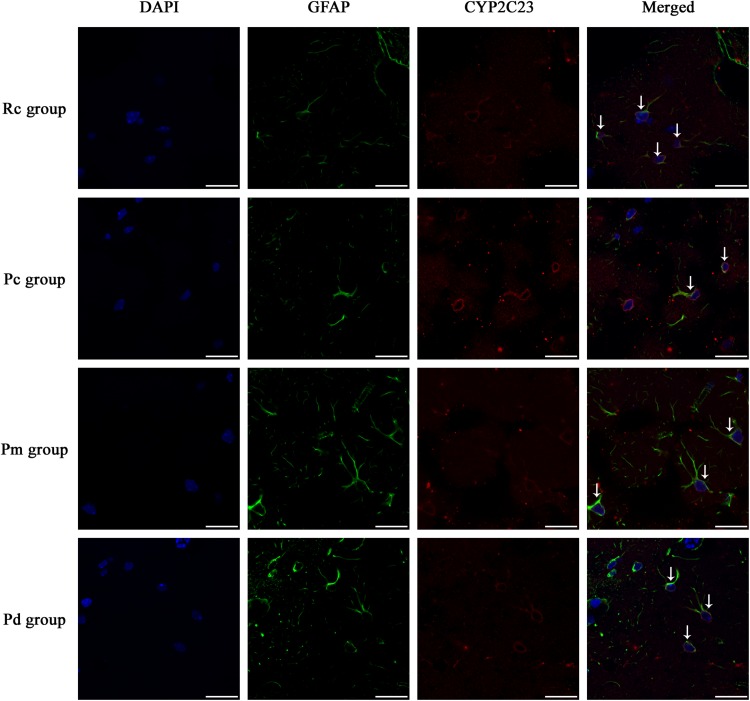

Effect of MA on the Coexpression of GFAP and PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the Hippocampus

IF staining and quantitative analysis of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the hippocampus are presented in Figures 4–7. The astrocytes were scattered in the hippocampus. GFAP was coexpressed with PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the cytoplasm and processes. The fluorescence intensity of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23, which were coexpressed with GFAP in the Pc group, was higher than that in the Rc group. Compared with that in the Pc group, there was a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the Pm and Pd groups. The quantitative analysis showed, that the mean optical density of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the Pc, Pm, and Pd groups, was significantly higher than that in the Rc group (p < 0.01). The mean optical density of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the Pm and Pd groups was markedly lower than that in the Pc group (p < 0.01).

FIGURE 4.

Representative images of IF staining of GFAP (green) and co-expressed PLA2 (red) in each group. GFAP is labeled with green fluorescence and the coexpressed PLA2 with red fluorescence. The nucleus is labeled with blue fluorescence. The astrocytes showed a polygonal nucleus. In the hippocampus, the positively stained cells are shown with white arrows. Scale bar is 20 μm.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of the expression of astrocytic PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the hippocampus between groups (n = 10, mean ± SD). (A–C) Comparison between the mean optical density of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 of all groups. A one-way ANOVA followed by LSD multiple-range test was used with an exception when comparing COX-1, which was analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test. LSD-t and Chi-Square are presented in Supplementary Tables 2, 4. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆◆P < 0.01.

FIGURE 5.

Representative images of IF staining of GFAP (green) and co-expressed COX-1 (red) in each group. GFAP is labeled with green fluorescence and the coexpressed COX-1 with red fluorescence. The nucleus is labeled with blue fluorescence. The astrocytes showed a polygonal nucleus. In the hippocampus, the positively stained cells are shown with white arrows. Scale bar is 20 μm.

FIGURE 6.

Representative images of IF staining of GFAP (green) and co-expressed CYP2C23 (red) in each group. GFAP is labeled with green fluorescence and the coexpressed CYP2C23 with red fluorescence. The nucleus is labeled with blue fluorescence. The astrocytes showed a polygonal nucleus. In the hippocampus, the positively stained cells are shown with white arrows. Scale bar is 20 μm.

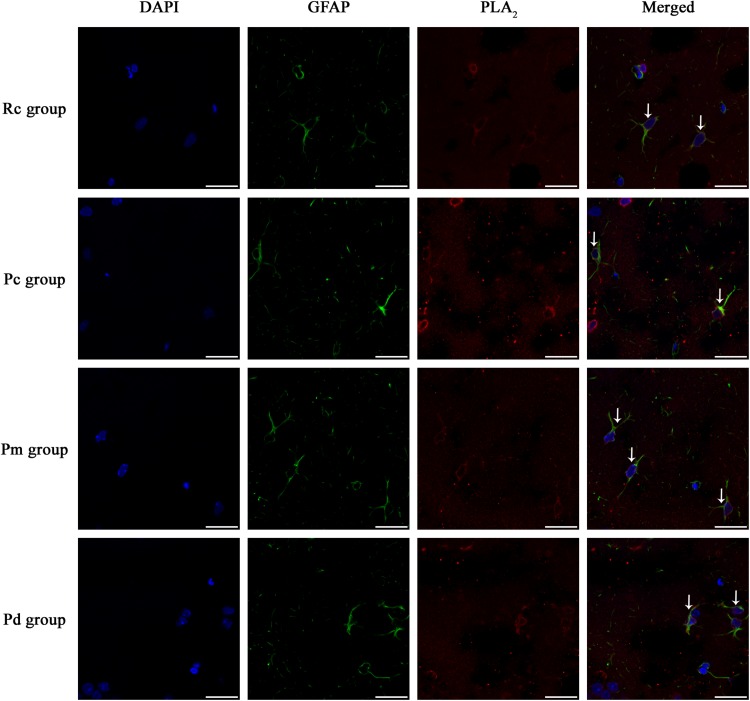

Effect of MA on the Relative Expression of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the Hippocampus

The western blotting results of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 protein expressions, in the hippocampus, are presented in Figure 8. The relative expression of PLA2, COX-1, and CYP2C23 in the Pc group was significantly higher than that in the Rc group (p < 0.01). Compared with that in the Pc group, the relative expression of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the Pm and Pd groups decreased drastically (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05). The relative expression of PLA2 in the Pm and Pd groups was higher than that in the Rc group (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05).

FIGURE 8.

WB results in each group. (A–C) Comparison between the relative expression of PLA2, COX-1 and CYP2C23 in the hippocampus (n = 8, mean ± SD). A one-way ANOVA followed by LSD multiple-range test was used with an exception when comparing PLA2, which was analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis test. LSD-t and Chi-Square are presented in Supplementary Tables 2, 5. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆P < 0.05 compared with the Rc group. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆P < 0.05 compared with the Pc group.

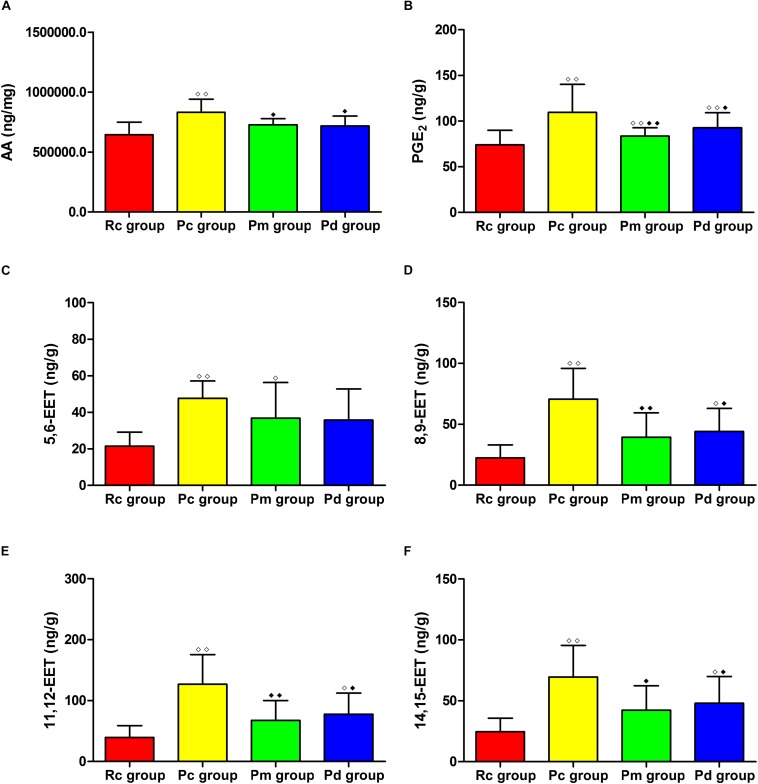

Effects of MA on the Contents of AA, PGE2 and EETs in the Hippocampus

The LC-MS/MS results of AA, PGE2 and EETs are presented in Figures 9, 10. Compared with those in the Rc group, the contents of AA, PGE2, 5,6-EET, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET in the Pc group significantly increased (p < 0.01). The contents of AA, PGE2, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET in the Pm and Pd group were markedly lower than those in the Pc group (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05). The contents of PGE2 and 5,6-EET in the Pm group and PGE2, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET in the Pd group, were drastically higher than those in the Rc group (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05).

FIGURE 9.

The LC-MS/MS results. (A–H) Chromatographs of AA, PGE2, 5,6-EET, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET, 14,15-EET, 8,9-EET-d11 and PGE2-d4.

FIGURE 10.

Comparison between the contents of AA, PGE2 and EETs between groups (n = 8, mean ± SD). (A–H) Comparison between the contents of AA, PLA2, 5,6-EET, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET in the hippocampus. A one-way ANOVA followed by LSD multiple-range test was used with an exception when comparing PGE2, which was analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis test. LSD-t and Chi-Square are presented in Supplementary Tables 2, 6. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆P < 0.05 compared with the Rc group. ◆◆P < 0.01, ◆P < 0.05 compared with the Pc group.

Discussion

The abnormality of the cerebrovascular function is one of the basic pathological changes and a key point in AD pathogenesis. Acupuncture plays an active role in the clinical efforts against AD and our previous study showed that MA can effectively enhance CBF in the prefrontal lobes and hippocampi of SAMP8 mice (Ding et al., 2019). However, the underlying molecular mechanism remains largely elusive. In this study, we aimed to elucidate the effect of MA on the astrocytes PLA2-AA pathway and on the cognitive ability of SAMP8 mice.

As a classic behavioral experiment, the MWM test has been widely used to evaluate spatial learning and memory. Our results showed that there were no significant differences in swimming speed among the groups in the hidden platform or probe trials, suggesting identical swimming ability. Swimming speed deviations from the norm on the behavioral test were excluded. In the Pc group, the behavioral results showed that the escape latency on days 2–5 of the hidden platform trial was significantly higher than in the Rc group (p < 0.01). The platform crossover number and the percentage of time and swimming distance in the platform quadrant were drastically decreased (p < 0.01). These results demonstrate that the mice in the Pc group suffered a marked decline in memory and learning abilities, which is in accordance with what is observed with AD pathological changes. Both MA and donepezil significantly increased the platform crossover number and percentage of time and swimming distance in the platform quadrant; while, decreasing the escape latency (p < 0.01). These observations indicate, that the equal effects of MA and donepezil, can effectively improve the learning and memory abilities of SAMP8 mice. It is worth noting that, in the hidden platform trial; while, the most notable difference in the escape latency between the Pc and Pm group occurred on day 3 (p < 0.01), similar changes appeared on day 4 for the Pd group (p < 0.05). Besides, the escape latency in the Pd group was still drastically higher than that of the Rc group on days 3–5 (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05). These results demonstrate, that MA tends to have a greater effect in improving SMAP8 mice spatial learning ability, in accordance with our previous study (Ding et al., 2019). In this study, the behavioral experiments using the MWM test further confirmed the effectiveness of MA in improving AD cognitive ability. Additionally, the results suggest, that the mechanism by which MA counteracts AD, is different from that of donepezil. We speculate, that this difference, is related to the multitarget nature of acupuncture (Cao et al., 2016), which manifests anti-inflammatory (Ding et al., 2017), anti-oxidative (Liu et al., 2013; Sutalangka et al., 2013), anti-apoptotic (Guo et al., 2015) and anti-Aβ effects (Wang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Zhang M. et al., 2017) in AD. These effects meet the need for a multimodal AD therapy (Ubhi and Masliah, 2013; Ibrahim and Gabr, 2019). Considering of the advantages of MA, such as safety and convenience, additional studies of MA effects on AD should be performed. In this study, the technical details, such as acupoints selection, manipulation and treatment arrangement, provide a valid reference for clinical researchers.

This study also shows the limitation of MA, as manifested in the significant differences in cognitive ability between Pm and Rc groups. SAMP8 mice present age-related deteriorations in behavior, physiology, neuropathology, and neurochemistry (Takeda, 2009). These mice exhibit Aβ deposition in the hippocampus, as early as 6 months, and that progresses with age. In contrast, this process does not start in SAMR1 mice until 15 months (Del Valle et al., 2010). Thus, we speculate that the limited beneficial effects of MA on cognitive ability were due to SAMP8 mice advanced age. Furthermore, our data suggest, that MA interventions, should be initiated at an early stage to better elucidate the characteristics of MA anti-AD effect. On the other hand, our results reconfirm, that for a chronic neurodegenerative disease with complex pathogenesis, such as AD, early intervention is of great significance for effective disease control and good prognosis, and which aligns with the common view on AD treatment (Khan, 2018).

In this study, COX-1, an astrocyte constitutive enzyme, that is closely associated with resting blood flow (Takano et al., 2006; Rosenegger et al., 2015) and CYP2C23, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of EETs (Capdevila et al., 2015), had significantly higher mean optical densities in the Pc group when compared to the Rc group (p < 0.01). These results were similar for the astrocytic PLA2 and the contents of AA, PGE2 and EETs, which were also significantly higher in the Pc group compared to those in the Rc group (p < 0.01). These findings were consistent with previous studies (Esposito et al., 2008; Sanchez-Mejia et al., 2008; Sanchez-Mejia and Mucke, 2010), that demonstrated an upregulation of the astrocytic PLA2-AA pathway in the hippocampus of the Pc group, which involved an increase in the expression of COX-1, CYP2C23 and the contents of PGE2 and EETs. The changes corresponded to a the neurovascular response to a lower CBF, that was caused by the deposition of Aβ in AD (Hamel, 2015; Kimbrough et al., 2015), and which also suggested an over activation of the PLA2-AA pathway in the Pc group. When combining these results with the previously reported lower CBF in SAMP8 mice compared to SAMR1 mice (Ding et al., 2019), the results show that the compensatory neurovascular response fails to enhance CBF, demonstrating a cerebral neurovascular dysfunction in SAMP8 mice. One possible reason for this failure is the structural and functional impairments of the cerebral microvasculature, that are induced by Aβ deposition, and which are important mechanisms for AD cerebrovascular damage (Dorr et al., 2012; Kimbrough et al., 2015; Sisante et al., 2019). The cerebral amyloid angiopathy, caused by the deposition of Aβ in the wall of cerebral blood vessels, not only destroys the cerebrovascular structure, but also impairs the neurovascular coupling (Lai et al., 2015; Giannoni et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2017; Hecht et al., 2018). Generally, the results suggest that under such circumstances, therapeutic strategies that attempt to enhance CBF through vasodilation, are less feasible. Therefore, early intervention and protection of the cerebral microvascular structure and function, as far as possible, are very important for delaying the pathological process and thus, support AD clinical treatment.

Both MA and donepezil can reverse such changes and drastically downregulate PLA2, COX-1, CYP2C23 and the contents of AA, PGE2 and EETs in the hippocampus (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05). The PLA2-AA pathway and AA metabolism were at normal levels in the Pm and Pd groups. Aside from their different effects on EETs, there were no notable differences between the moderating effects of MA and donepezil on PLA2, AA downstream metabolic pathway and related proteins or metabolites between the Pm and Pd groups. Our results showed that the contents of 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET, and 14,15-EET in the Pd group significantly increased compared with those in the Rc group (p < 0.05). This change did not occur in the Pm group, indicating that the effect of MA on EETs has a better effectiveness. Compared with the Pc group, the Pm and Pd groups exhibited an inhibition of the vasodilatory pathways (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05). Based on our previous report on the beneficial effects of MA and donepezil on CBF, it is clear that MA enhances CBF through ‘abnormal’ vasoconstriction rather than typical vasodilatation, which is the regular mean for a normal physiological state. This result did not conform with previous studies that demonstrated an increased blood flow that was associated with blood flow velocity and vasodilatation (Stoner et al., 2004; Domoki et al., 2012). Since CBF is defined as the CBF velocity × cross-sectional area, the paradoxical relationship between the ‘abnormal’ vasoconstriction found in this study and the increase in CBF suggests that the regulation of the CBF velocity may be a reason for the beneficial effect of MA on CBF. In particular, the inhibition of the vasodilatory pathway may result in increasing the arterial tone, which eventually promotes the blood flow velocities. Our results also suggest that conduit arteries, which can dilate or constrict depending of the arterial tone, may be potential targets in the CBF regulation by MA, as arterioles tend to be responsible for the hemodynamic resistance. In summary, we speculate that changes of the arterial tone in conduit arteries, induced by the inhibition of the vasodilatory pathway, may be a reason for the beneficial effect of MA on CBF. It is noteworthy that this kind of vasoconstriction is an ‘abnormal’ intervention mode under the pathological status of AD.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the sample size in the behavioral test was small. Since a difference between MA and donepezil in improving cognitive ability was observed, further studies should clarify the characteristics of MA. Additionally, a behavioral test should be performed before the intervention to better explain the effect of MA. This study suggests that the benign effect of MA on CBF may be based on the increase in CBF velocity, induced by the changes of arterial tone. Second, the PLA2 activity and the access to its phospholipid substrate is increased by Ca2+ binding to its C2 domain and phosphorylation by the ERK/MAPK kinases (Sanchez-Mejia and Mucke, 2010). Therefore, the effect of MA on Ca2+, the phosphorylation of PLA2 and related kinases warrant further investigations. Besides, this study revealed that MA has a negative regulatory effect on the PLA2-AA pathway, and we speculate that the regulation of the CBF velocity may be a reason for the beneficial effect of MA on CBF. Combined with our previous study (Ding et al., 2019), the results suggest a benign regulatory effect of MA on the structure and function of cerebral vessels. Future studies should observe and further confirm the modulatory effect of MA on the morphology of cerebral vessels and hemodynamics through histological, biochemical and in vivo imaging techniques, such as two-photon microscopy (Song et al., 2017), transcranial Doppler ultrasound (Liu et al., 2013) and photoacoustic microscope (Ning et al., 2015). Finally, the limited effects of MA and donepezil on cognitive ability demonstrated that there is still potential for optimization. Earlier MA intervention, longer duration of MA and stronger doses of donepezil should be encouraged.

In summary, this study validated the authenticity and reliability of using MA to improve cognitive ability, with MA tending to have a greater effect in improving spatial learning ability in SMAP8 mice. Additionally, this study revealed the underlying mechanism of the beneficial effects of MA on CBF and found that MA has a negative regulatory effect on the PLA2-AA pathway, as reflected in its downregulation of PLA2, COX-1, CYP2C23, and the contents of AA, PGE2, and EETs in SAMP8 mice hippocampi. We propose that the changes of arterial tone, induced by the inhibition of vasodilatory pathway, might be a reason for the beneficial effect of MA on CBF. Further in vivo studies should be encouraged to observe and confirm the modulatory effect of MA on cerebral vessels and hemodynamics.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

All experimental procedures complied with the guidelines of the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by the National Institute of Health and the legislation of the People’s Republic of China for the use and care of laboratory animals. The experimental protocols were approved by the Medicine and Animal Ethics Committee of the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine.

Author Contributions

ND: experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. HT and SW: data collection. JJ and ZL: experimental design. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Yanli Zhang, Tsinghua University, and Dr. Yanhui Li, Peking University Health Science Center, for their support regarding the confocal laser scanning microscope and LC-MS/MS respectively.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81804178 and 81473774).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2019.01354/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdi H., Williams L. J., Beaton D., Posamentier M. T., Harris T. S., Krishnan A., et al. (2012). Analysis of regional cerebral blood flow data to discriminate among Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and elderly controls: a multi-block barycentric discriminant analysis (MUBADA) methodology. J. Alzheimers Dis. 31 S189–S201. 10.3233/JAD-2012-112111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta C., Anderson H. D., Anderson C. M. (2017). Astrocyte dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 95 2430–2447. 10.1002/jnr.24075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiguchi I., Pallàs M., Budka H., Akiyama H., Ueno M., Han J., et al. (2017). SAMP8 mice as a neuropathological model of accelerated brain aging and dementia: Toshio Takeda’s legacy and future directions. Neuropathology 37 293–305. 10.1111/neup.12373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D., Buchan A. M., Charpak S., Lauritzen M., Macvicar B. A., Newman E. A. (2010). Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 468 232–243. 10.1038/nature09613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayod S., Felice P., Andrés P., Rosa P., Camins A., Pallàs M., et al. (2014). Downregulation of canonical Wnt signaling in hippocampus of SAMP8 mice. Neurobiol. Aging 36 720–729. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. E., Robbins A. B., Hu M., Cao X., Betensky R. A., Clark T., et al. (2018). Tau induces blood vessel abnormalities and angiogenesis-related gene expression in P301L transgenic mice and human Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 E1289–E1298. 10.1073/pnas.1710329115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield D. A., Poon H. F. (2005). The senescence-accelerated prone mouse (SAMP8): a model of age-related cognitive decline with relevance to alterations of the gene expression and protein abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 40 774–783. 10.1016/j.exger.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Tang Y., Li Y., Gao K., Shi X., Li Z. (2017). Behavioral changes and hippocampus glucose metabolism in APP/PS1 transgenic mice via electro-acupuncture at governor vessel acupoints. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:5. 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Zhang L. W., Wang J., Du S. Q., Xiao L. Y., Tu J. F., et al. (2016). Mechanisms of acupuncture effect on Alzheimer’s disease in animal- based researches. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 16 574–578. 10.2174/1568026615666150813144942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila J. H., Wang W., Falck J. R. (2015). Arachidonic acid monooxygenase: genetic and biochemical approaches to physiological/pathophysiological relevance. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 120 40–49. 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Homma A., Mok V. C., Krishnamoorthy E., Alladi S., Meguro K., et al. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease with cerebrovascular disease: current status in the Asia-Pacific region. J. Intern. Med. 280 359–374. 10.1111/joim.12495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X. R., Zhou W. X., Zhang Y. X. (2014). The behavioral, pathological and therapeutic features of the senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 strain as an Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Ageing Res. Rev. 13 13–37. 10.1016/j.arr.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre J. C. (2010). Vascular risk factor detection and control may prevent Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 9 218–225. 10.1016/j.arr.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle J., Duran-Vilaregut J., Manich G., Casadesús G., Smith M. A., Camins A., et al. (2010). Early amyloid accumulation in the hippocampus of SAMP8 mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 19 1303–1315. 10.3233/JAD-2010-1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delekate A., Füchtemeier M., Schumacher T., Ulbrich C., Foddis M., Petzold G. C. (2014). Metabotropic P2Y1 receptor signalling mediates astrocytic hyperactivity in vivo in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nat. Commun. 5:5422. 10.1038/ncomms6422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco L. Y., Venneri A., Farkas E., Evans P. C., Marzo A., Frangi A. F. (2015). Vascular dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease–A review of endothelium-mediated mechanisms and ensuing vicious circles. Neurobiol. Dis. 82 593–606. 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N., Jiang J., Lu M., Hu J., Xu Y., Liu X., et al. (2017). Manual acupuncture suppresses the expression of proinflammatory proteins associated with the NLRP3 inflammasome in the hippocampus of SAMP8 mice. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2017:3435891. 10.1155/2017/3435891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N., Jiang J., Xu A., Tang Y., Li Z. (2019). Manual acupuncture regulates behavior and cerebral blood flow in the SAMP8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 13:37. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domoki F., Zölei D., Oláh O., Tóth-Szuki V., Hopp B., Bari F., et al. (2012). Evaluation of laser-speckle contrast image analysis techniques in the cortical microcirculation of piglets. Microvasc. Res. 83 311–317. 10.1016/j.mvr.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr A., Sahota B., Chinta L. V., Brown M. E., Lai A. Y., Ma K., et al. (2012). Amyloid-β-dependent compromise of microvascular structure and function in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 135 3039–3050. 10.1093/brain/aws243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G., Giovacchini G., Liow J. S., Bhattacharjee A. K., Greenstein D., Schapiro M., et al. (2008). Imaging neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease with radiolabeled arachidonic acid and PET. J. Nucl. Med. 49 1414–1421. 10.2967/jnumed.107.049619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Z., Zhang J. J., Liu H., Wu G. Y., Xiong L., Shu M. (2013). Regional cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reactivity in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia assessed by arterial spinlabeling magnetic resonance imaging. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 10 49–53. 10.2174/1567202611310010007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts H., Guillaumat P. O., Grantham C., Bode W., Anciaux K., Sachak S. (2005). Brain levels and acetylcholinesterase inhibition with galantamine and donepezil in rats, mice, and rabbits. Brain Res. 1033 186–193. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoni P., Arango-Lievano M., Neves I. D., Rousset M. C., Baranger K., Rivera S., et al. (2016). Cerebrovascular pathology during the progression of experimental Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 88 107–117. 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griñán-Ferré C., Corpas R., Puigoriol-Illamola D., Palomera-Ávalos V., Sanfeliu C., Pallàs M. (2018). Understanding epigenetics in the neurodegeneration of Alzheimer’s disease: SAMP8 mouse model. J. Alzheimers Dis. 62 943–963. 10.3233/JAD-170664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griñan-Ferré C., Puigoriol-Illamola D., Palomera-Ávalos V., Pérez-Cáceres D., Companys-Alemany J., Camins A., et al. (2016). Environmental enrichment modified epigenetic mechanisms in SAMP8 mouse hippocampus by reducing oxidative stress and inflammaging and achieving neuroprotection. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8:241. 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. D., Tian J. X., Zhu J., Li L., Sun K., Shao S. J., et al. (2015). Electroacupuncture suppressed neuronal apoptosis and improved cognitive impairment in the AD model rats possibly via downregulation of notch signaling pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015:393569. 10.1155/2015/393569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. D., Zhu J., Tian J., Shao S. J., Xu Y. W., Mou F. F., et al. (2016). Electroacupuncture improves memory and protects neurons by regulation of the autophagy pathway in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acupunct. Med. 34 449–456. 10.1136/acupmed-2015-010894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel E. (2015). Cerebral circulation: function and dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 65 317–324. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanyu H., Sato T., Hirao K., Kanetaka H., Iwamoto T., Koizumi K. (2010). The progression of cognitive deterioration and regional cerebral blood flow patterns in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal SPECT study. J. Neurol. Sci. 290 96–101. 10.1016/j.jns.2009.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays C. C., Zlatar Z. Z., Wierenga C. E. (2016). The utility of cerebral blood flow as a biomarker of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 36 167–179. 10.1007/s10571-015-0261-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Linden D. J., Sapirstein A. (2012). Astrocyte inositol triphosphate receptor type 2 and cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha regulate arteriole responses in mouse neocortical brain slices. PLoS One 7:e42194. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht M., Kramer L. M., von Arnim C., Otto M., Thal D. R. (2018). Capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s disease association with allocortical/hippocampal microinfarcts and cognitive decline. Acta Neuropathol. 135 681–694. 10.1007/s00401-018-1834-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth C. (2014). The contribution of astrocytes to the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Front. Neurosci. 8:103. 10.3389/fnins.2014.00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. (2013). The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 80 844–866. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M. M., Gabr M. T. (2019). Multitarget therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 14 437–440. 10.4103/1673-5374.245463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger K. A. (2008). Morphologic diagnosis of “vascular dementia” - a critical update. J. Neurol. Sci. 270 1–12. 10.1016/j.jns.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Wei C., Chen S., Li F., Tang Y., Qin W., et al. (2018). The cost of Alzheimer’s disease in China and re-estimation of costs worldwide. Alzheimers Dement. 14 483–491. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y., Zhang X., Yu J., Han J., Yu T., Shi J., et al. (2017). Acupuncture for patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 17:556. 10.1186/s12906-017-2064-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Ding N., Wang K., Li Z. (2018). Electroacupuncture could influence the expression of IL-1β and NLRP3 inflammasome in hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018:8296824. 10.1155/2018/8296824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Gao K., Zhou Y., Xu A., Shi S., Liu G., et al. (2015). Electroacupuncture treatment improves learning-memory ability and brain glucose metabolism in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease using Morris water maze and micro-PET. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015:142129. 10.1155/2015/142129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Liu G., Shi S., Li Z. (2016). Musical electroacupuncture may be a better choice than electroacupuncture in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Plast. 2016:3131586. 10.1155/2016/3131586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. W., Lebrec J., Kahle-Wrobleski K., Dell’Agnello G., Bruno G., Vellas B., et al. (2017). Disease progression in mild dementia due to Alzheimer disease in an 18-month observational study (GERAS): the impact on costs and caregiver outcomes. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra 7 87–100. 10.1159/000461577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher R. J., Soiza R. L. (2013). Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in the development of Alzheimer’s disease: is Alzheimer’s a vascular disorder. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 3 197–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan T. K. (2018). An algorithm for preclinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 12:275. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough I. F., Robel S., Roberson E. D., Sontheimer H. (2015). Vascular amyloidosis impairs the gliovascular unit in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 138 3716–3733. 10.1093/brain/awv327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M. A., Green K. N., Blurton-Jones M., Laferla F. M. (2010). Oligemic hypoperfusion differentially affects Tau and amyloid-β. Am. J. Pathol. 177 300–310. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla K. V., Lattarulo C. R., Hyman B. T., Bacskai B. J. (2009). Synchronous hyperactivity and intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes in Alzheimer mice. Science 323 1211–1215. 10.1126/science.1169096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok T., Leung P. C., Wing Y. K., Ip I., Wong B., Ho D. W., et al. (2013). The effectiveness of acupuncture on the sleep quality of elderly with dementia: a within-subjects trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 8 923–929. 10.2147/CIA.S45611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacalle-Aurioles M., Mateos-Pérez J. M., Guzmán-De-Villoria J. A., Olazarán J., Cruz-Orduña I., Alemán-Gómez Y., et al. (2014). Cerebral blood flow is an earlier indicator of perfusion abnormalities than cerebral blood volume in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 34 654–659. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A. Y., Dorr A., Thomason L. A., Koletar M. M., Sled J. G., Stefanovic B., et al. (2015). Venular degeneration leads to vascular dysfunction in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 138 1046–1058. 10.1093/brain/awv023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane C. A., Hardy J., Schott J. M. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 25 59–70. 10.1111/ene.13439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Heron C. J., Wright S. L., Melzer T. R., Myall D. J., MacAskill M. R., Livingston L., et al. (2014). Comparing cerebral perfusion in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia an ASL-MRI study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 34 964–970. 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeuwis A. E., Benedictus M. R., Kuijer J. P. A., Binnewijzend M. A. A., Hooghiemstra A. M., Verfaillie S. C. J., et al. (2017). Lower cerebral blood flow is associated with impairment in multiple cognitive domains in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 13 531–540. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie C. C. (2015). Cytosolic phospholipase A2: physiological function and role in disease. J. Lipid. Res. 56 1386–1402. 10.1194/jlr.R057588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Cheng H., Zhang X., Shang X., Xie H., Zhang X., et al. (2013). Hippocampal neuron loss is correlated with cognitive deficits in SAMP8 mice. Neurol. Sci. 34 963–969. 10.1007/s10072-012-1173-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P., Wang Z., Qian T., Li K. (2014). Acupuncture stimulation of Taichong (Liv3) and Hegu (LI4) modulates the default mode network activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 29 739–748. 10.1177/1533317514536600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhu Y. S., Hill C., Armstrong K., Tarumi T., Hodics T., et al. (2013). Cerebral autoregulation of blood velocity and volumetric flow during steady-state changes in arterial pressure. Hypertension 62 973–979. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Zhuo P., Li L., Jin H., Lin B., Zhang Y., et al. (2017). Activation of brain glucose metabolism ameliorating cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 transgenic mice by electroacupuncture. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 112 174–190. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zeng X., Wang Z., Zhang N., Fan D., Yuan H. (2015). Different post label delay cerebral blood flow measurements in patients with Alzheimer’s disease using 3D arterial spin labeling. Magn. Reson. Imaging 33 1019–1025. 10.1016/j.mri.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco C. F., Ledo A., Barbosa R. M., Laranjinha J. (2017). Neurovascular uncoupling in the triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease: impaired cerebral blood flow response to neuronal-derived nitric oxide signaling. Exp. Neurol. 291 36–43. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manich G., Mercader C., del Valle J., Duran-Vilaregut J., Camins A., Pallàs M., et al. (2011). Characterization of amyloid-β granules in the hippocampus of SAMP8 mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 25 535–546. 10.3233/JAD-2011-101713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi V. (2011). Alzheimer’s dementia begins as a disease of small blood vessels, damaged by oxidative-induced inflammation and dysregulated amyloid metabolism: implications for early detection and therapy. FASEB J. 25 5–13. 10.1096/fj.11-0102ufm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaslin A. F., Chen B. R., Radosevich A. J., Cauli B., Hillman E. M. (2011). In vivo 3D morphology of astrocyte-vasculature interactions in the somatosensory cortex: implications for neurovascular coupling. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31 795–806. 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A. R., Sweeney M. D., Sagare A. P., Zlokovic B. V. (2016). Neurovascular dysfunction and neurodegeneration in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1862 887–900. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R. B., Egefjord L., Angleys H., Mouridsen K., Gejl M., Møller A., et al. (2017). Capillary dysfunction is associated with symptom severity and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 13 1143–1153. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning B., Kennedy M. J., Dixon A. J., Sun N., Cao R., Soetikno B. T., et al. (2015). Simultaneous photoacoustic microscopy of microvascular anatomy, oxygen saturation, and blood flow. Opt. Lett. 40 910–913. 10.1364/OL.40.000910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo O. C., Xu G., Oh J. M., Dowling N. M., Carlsson C. M., Gallagher C. L., et al. (2014). Cerebral blood flow is diminished in asymptomatic middle-aged adults with maternal history of Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb. Cortex 24 978–988. 10.1093/cercor/bhs381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell W. S., Rokach J. (2015). Biosynthesis, biological effects, and receptors of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and oxoeicosatetraenoic acids (oxo-ETEs) derived from arachidonic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851 340–355. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenegger D. G., Tran C. H., Wamsteeker C. J., Gordon G. R. (2015). Tonic local brain blood flow control by astrocytes independent of phasic neurovascular coupling. J. Neurosci. 35 13463–13474. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1780-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagare A. P., Bell R. D., Zlokovic B. V. (2012). Neurovascular dysfunction and faulty amyloid β-peptide clearance in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a011452. 10.1101/cshperspect.a011452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A., Kauppinen A., Kaarniranta K. (2017). Hypoxia/ischemia activate processing of Amyloid Precursor Protein: impact of vascular dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 140 536–549. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Mejia R. O., Mucke L. (2010). Phospholipase A2 and arachidonic acid in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801 784–790. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Mejia R. O., Newman J. W., Toh S., Yu G. Q., Zhou Y., Halabisky B., et al. (2008). Phospholipase A2 reduction ameliorates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 11 1311–1318. 10.1038/nn.2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini M., Gatti A., Quirico P. E., Balla S., Capellero B., Obialero R., et al. (2015). Acupressure in insomnia and other sleep disorders in elderly institutionalized patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 27 37–42. 10.1007/s40520-014-0244-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisante J. V., Vidoni E. D., Kirkendoll K., Ward J., Liu Y., Kwapiszeski S., et al. (2019). Blunted cerebrovascular response is associated with elevated beta-amyloid. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39 89–96. 10.1177/0271678X17732449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Nan D., He Q., Yang L., Guo H. (2017). Astrocyte activation and capillary remodeling in modified bilateral common carotid artery occlusion mice. Microcirculation 24:e12366. 10.1111/micc.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector A. A. (2009). Arachidonic acid cytochrome P450 epoxygenase pathway. J. Lipid Res. 50 S52–S56. 10.1194/jlr.R800038-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner L., Sabatier M., Edge K., McCully K. (2004). Relationship between blood velocity and conduit artery diameter and the effects of smoking on vascular responsiveness. J. Appl. Physiol. 96 2139–2145. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01107.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutalangka C., Wattanathorn J., Muchimapura S., Thukham-Mee W., Wannanon P., Tong-un T. (2013). Laser acupuncture improves memory impairment in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 6 247–251. 10.1016/j.jams.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T., Tian G. F., Peng W., Lou N., Libionka W., Han X., et al. (2006). Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat. Neurosci. 9 260–267. 10.1038/nn1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T. (2009). Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM) with special references to neurodegeneration models, SAMP8 and SAMP10 mice. Neurochem. Res. 34 639–659. 10.1007/s11064-009-9922-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantini S., Tran C. H. T., Gordon G. R., Ungvari Z., Csiszar A. (2017). Impaired neurovascular coupling in aging and Alzheimer’s disease: contribution of astrocyte dysfunction and endothelial impairment to cognitive decline. Exp. Gerontol. 94 52–58. 10.1016/j.exger.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubhi K., Masliah E. (2013). Alzheimer’s disease: recent advances and future perspectives. J. Alzheimers Dis. 33 185–194. 10.3233/JAD-2012-129028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Haar H. J., Jansen J. F. A., van Osch M. J. P., van Buchem M. A., Muller M., Wong S. M., et al. (2016). Neurovascular unit impairment in early Alzheimer’s disease measured with magnetic resonance imaging. Neurobiol. Aging 45 190–196. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Norden A. G., van Dijk E. J., de Laat K. F., Scheltens P., Olderikkert M. G., de Leeuw F. E. (2012). Dementia: Alzheimer pathology and vascular factors: from mutually exclusive to interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1822 340–349. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Miao Y., Abulizi J., Li F., Mo Y., Xue W., et al. (2016). Improvement of electroacupuncture on APP/PS1 transgenic mice in spatial learning and memory probably due to expression of Aβ and LRP1 in hippocampus. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016:7603975. 10.1155/2016/7603975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Xing A., Xu C., Cai Q., Liu H., Li L. (2010). Cerebrovascular hypoperfusion induces spatial memory impairment, synaptic changes, and amyloid-β oligomerization in rats. J. Alzheimers Dis. 21 813–822. 10.3233/JAD-2010-100216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Liang P., Zhao Z., Han Y., Song H., Xu J., et al. (2014). Acupuncture modulates resting state hippocampal functional connectivity in Alzheimer disease. PLoS One 9:e91160. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Nie B., Li D., Zhao Z., Han Y., Song H., et al. (2012). Effect of acupuncture in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease a functional MRI study. PLoS One 7:e42730. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami T., Yamamoto Y., Koma H. (2014). The role of secretory phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system and neurological diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 49 863–876. 10.1007/s12035-013-8565-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Liu C. Y., Wong K. P., Huang S. C., Mack W. J., Jann K., et al. (2017). Regional association of pCASL-MRI with FDG-PET and PiB-PET in people at risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 17 751–760. 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Falck J. R., Roman R. J., Harder D. R., Koehler R. C., Yang Z. J. (2017). Upregulation of 20-HETE synthetic cytochrome P450 isoforms by oxygen-glucose deprivation in cortical neurons. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 37 1279–1286. 10.1007/s10571-017-0462-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Xv G. H., Wang W. X., Meng D. J., Ji Y. (2017). Electroacupuncture improves cognitive deficits and activates PPAR-γ in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acupunct. Med. 35 44–51. 10.1136/acupmed-2015-010972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Yang N., Ai D., Zhu Y. (2015). Systematic metabolomic analysis of eicosanoids after omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation by a highly specific liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry-based method. J. Proteome Res. 14 1843–1853. 10.1021/pr501200u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W., Su Z., Liu X., Zhang H., Han Y., Song H., et al. (2018). Modulation of functional activity and connectivity by acupuncture in patients with Alzheimer disease as measured by resting-state fMRI. PLoS One 13:e196933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Peng W., Xu M., Li W., Liu Z. (2015). The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for patients with Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 94:e933. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Dong L., He Y., Xiao H. (2017). Acupuncture plus herbal medicine for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Chin. Med. 45 1327–1344. 10.1142/S0192415X17500732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic B. V. (2005). Neurovascular mechanisms of Alzheimer’s neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 28 202–208. 10.1016/j.tins.2005.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic B. V. (2011). Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 723–738. 10.1038/nrn3114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonta M., Angulo M. C., Gobbo S., Rosengarten B., Hossmann K. A., Pozzan T., et al. (2003). Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat. Neurosci. 6 43–50. 10.1038/nn980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.