Abstract

Senna alata is a medicinal herb of Leguminosae family. It is distributed in the tropical and humid regions. The plant is traditionally used in the treatment of typhoid, diabetes, malaria, asthma, ringworms, tinea infections, scabies, blotch, herpes, and eczema. The review is aimed at unveiling the ethnobotanical description and pharmacological activities of S. alata. Different parts of the plant are reported in folk medicine as therapeutic substances for remediation of diverse diseases and infections. The extracts and isolated compounds displayed pronounced pharmacological activities. Display of antibacterial, antioxidant, antifungal, dermatophytic, anticancer, hepatoprotective, antilipogenic, anticonvulsant, antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, antimalarial, anthelmintic, and antiviral activities could be due to the array of secondary metabolites such as tannins, alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenes, anthraquinone, saponins, phenolics, cannabinoid alkaloids, 1,8-cineole, caryophyllene, limonene, α-selinene, β-caryophyllene, germacrene D, cinnamic acid, pyrazol-5-ol, methaqualone, isoquinoline, quinones, reducing sugars, steroids, and volatile oils present in different parts of the plant. The review divulges the ethnobotanical and pharmacological activities of the plant and also justifies the ethnomedical claims. The significant medicinal value of this plant necessitates a scientific adventure into the bioactive metabolites which constitute various extracts.

1. Introduction

The primary and safest therapeutic approach since prehistoric time is herbal medicine which has displayed significant role in primary health care development [1]. The World Health organization (WHO) appraised that 80% of inhabitants in developing countries basically rely on herbal medicines [2, 3]. Recently, it was discovered that one-third of the commonly used drugs are obtained from natural sources. This has led to the documentation of about 40,000–70,000 medicinal plant species with outstanding therapeutic potentials [4].

The scientific appraisal of the pharmacological activities of herbal plants revealed about 200,000 phytochemicals. These compounds contribute to the apparent medicinal activities displayed by plants and invariably justify the involvement of natural products in the development of novel drugs [5]. Despite these achievements, the use of herbal drugs was not universally accepted in contemporary medicine due to lack of scientific evidence and proper documentation. However, the significance of herbs in pharmacology has necessitated the provision of scientific facts on bioactive compounds and pharmacological assays of plants [6, 7].

Medicinal plants with immense biological applications have been viewed as the principal sources of therapeutic substances which could lead to novel therapeutic compounds. The search for these compounds from medicinal plants usually ends in the isolation of novel compounds and, eventually, drug developments [8]. Several medicinal plants with diverse interesting pharmacophore have been scientifically investigated, and one of these plants is Senna alata.

S. alata, also known as Cassia alata, is a widely distributed herb of the Leguminosae family. It is commonly known as candle bush, craw-craw plant, acapulo, ringworm bush, or ringworm plant. The plant is commonly found in Asia and Africa, and has many local names [9]. It has arrays of bioactive chemical compounds. Some of the reported chemical constituents are phenolics (rhein, chrysaphanol, kaempferol, aloeemodin, and glycosides), anthraquinones (alatinone and alatonal), fatty acids (oleic, palmitic, and linoleic acids), steroids, and terpenoids (sitosterol, stigmasterol, and campesterol) [10, 11]. These secondary metabolites are reported to display numerous biological activities [12–17].

The flower, root, leaves, seed, and bark displayed diverse biological activities [18–20]. These pharmacological activities include antimicrobial [21–23], antifungal [24], anticryptococcus [25], antibacterial [26, 27], antitumor [28], anti-inflammatory [29, 30], antidiabetic [31], antioxidant [18], wound healing [32], and antihelmintic activities [33]. In recent times, the outbreak of drug-resistant diseases has led to several health issues. In an attempt to resolve these issues, pharmacological research has been tailored towards the discovery of innovative, potent, and safe drugs from natural compounds. This review appraises the ethnobotanical and pharmacological activities of S. alata, thus justifying diverse traditional applications of the plant.

2. Review Methodology

Relevant documents were obtained from major scientific catalogues such as Pubmed, Google Scholar, EBSCO, SciFinder, Scopus, Medline, and Science Direct. Many publications sites were queried to procure information on ethnobotanical description and pharmacological activities of S. alata.

3. Ethnobotanical Description

3.1. Description and Classification

S. alata (L.) Roxb. is a flowering shrub of the Fabaceae family. It has the name “candle bush” owing to the framework of its inflorescences [34]. It is an annual and occasionally biannual herb, with an average height of 1 to 4 m, burgeoning in sunlit and humid zones. The leaves are oblong, with 5 to 14 leaflet sets, robust petioles (2 to 3 mm), caduceus bracts (2 × 3 by 1 × 2 cm), and dense flowers (20 × 50 by 3 × 4 cm). Zygomorphic flowers have bright yellow color with 7 stamens and a pubertal ovary. The fruit exists as a 10 to 16 × 1.5 cm tetragonal pod, thick, flattened wings, brown when ripe with many diamond-shaped brown seeds. It is propagated by seeds and dispersed to about 1,500 m above the sea level [35, 36].

Taxonomically, S. alata is classified as kingdom: Plantae; order: Fabales; family: Fabaceae; subfamily: Caesalpinioideae; tribe: Cassieae; subtribe: Cassiinae; genus: Senna; species: S. alata.

3.2. Geographical Distribution

S. alata is widely distributed in Ghana, Brazil, Australia, Egypt, India, Somalia, Sri Lanka, and all over Africa [37]. It is an ornamental plant native to the Amazon Rainforest [38]. Like other Senna species, it is cultivated in humid and tropic regions of Africa, Asia, West Indices, Mexico, Australia, South America, the Caribbean Islands, Polynesia, Hawaii, Melanesia, and different parts of India [39]. In Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, this shrub is widely dispersed and is cultivated for medicinal purposes [40].

3.3. Ethnobotanical Uses

In Ayurvedic, Sinhala, Chinese, and African traditional medicine, various parts of S. alata have shown diverse therapeutic activities in diseases control. In northern Nigeria, the stem, leaf, and root decoctions is used in treatment of wound, skin and respiratory tract infection, burns, diarrhoea, and constipation [41, 42]. Also, in the south-western regions, leaf decoction serves as an antidote to body and abdominal pain, stress, and toothache [43]. It also cures dermal infections, convulsion, and as purgative [44, 45]. In Egypt, the leaf decoction was observed to be used as a bowel stimulant to stimulate peristaltic shrinkages and decrease water absorption from the colon in attempt to prevent constipation [46]. In Cameroon, the stem, bark, and leaves were reported to be used as a remedy for gastroenteritis, hepatitis, ringworm, and dermal infections [47].

In India, Philippines, and China, S. alata's stem, bark, and leaf decoction were found to be effective in treating haemorrhoids, inguinal hernia, syphilis, intestinal parasitosis, and diabetes [48]. Currently, seeds and roots are used in regulating uterus disorder and worms [18, 49]. The leaves and flowers are typically used as antifungal agents and laxatives [35]. In China, the seeds are used in treating asthma and to improve visibility [50]. In Guatemela, Brazil, and Guinea, the whole plant is currently used in the treatment of flu and malaria [36]. The flower and leaves decoction was observed to be used in treatment of ringworms, scabies, blotch, eczema, scabies, and tine infections [11, 51]. The leaves are currently used in Sierra Leone to relieve abortion pain and facilitate baby delivery [51]. In west and east Africa, bark decoction is spread on cuts during tribal mark incision and tattoo making [52]. In China, India, Benin republic, Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo, the whole plant is used as a curative for Diabetes mellitus [34, 53]. Fresh leaves of the plant are used in the treatment of skin rashes, mycosis, and dermatitis [54]. From the traditional uses, the frequent use of S. alata leaves is more than that of roots, flowers, roots, and stem-bark owing to more active metabolites reported in the leaves. Besides its pharmacological activities, it is processed into capsule, pellet, and tea in Nigeria for preventing diseases and maintaining sound health.

3.4. Pharmacological Activities

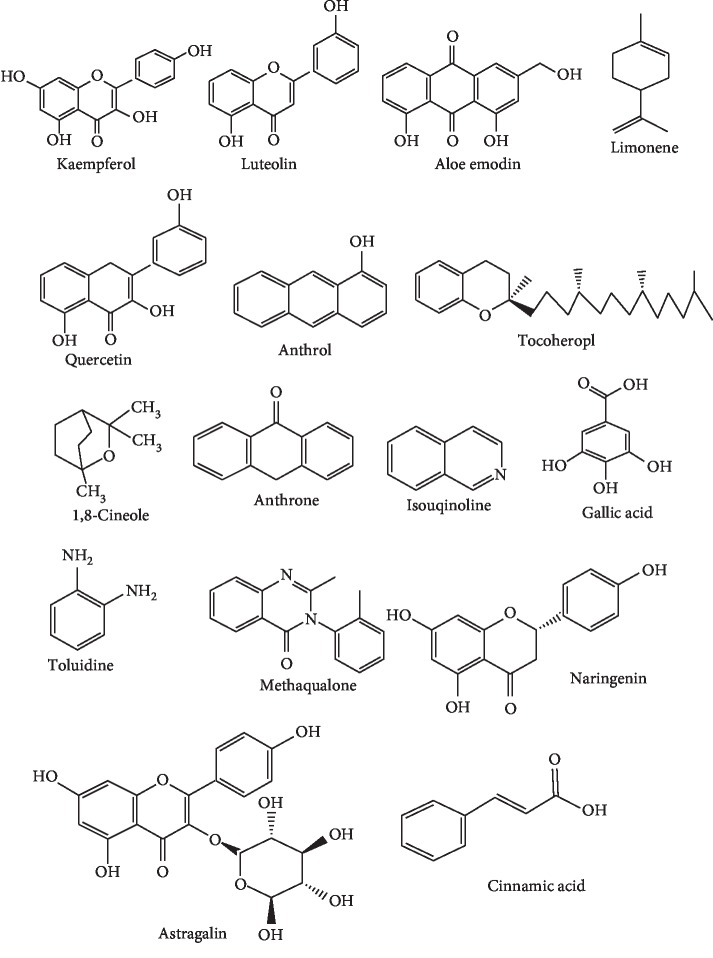

Medicinal plants belonging to the Fabaceae family have extensively been investigated for their pharmacological activities. Plants synthesised array of secondary metabolites which contribute to its therapeutic activities (Figure 1). Therapeutic appraisal of S. alata authenticates the ethnobiological claims and establishes the pharmacological activities (Table 1). There are many published articles connected to diverse therapeutic activities of S. alata which are mainly related to antibacterial, antidiabetic, antilipogenic, antifungal, antioxidant, dermatophytic, antihyperlipidemic, and anthelmintic activities among others. Few studies have also reported its antimalarial activities.

Figure 1.

Bioactive compounds with therapeutic potencies in S. alata.

Table 1.

Pharmacological activities of S. alata.

| Parts used | Country | Ethnomedicinal use | Solvent used | Pharmacological activity | Model used | Phytochemicals | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Leaves | Nigeria | Treatment of diarrhoea, upper respiratory tract infection, and to hasten labour | Aqueous | Abortifacient | Pregnant rats | Saponins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, cardenolides, dienolides, phenolics and alkaloids | [55] |

| (2) | Leaves | India | To manage diabetes | Ethanolic | Hepato-renal protective effects | Male albino Wistar rats | [56] | |

| (3) | Leaves | India | Treatment of allergy/asthma | Hydromethanolic | Antiallergic | Lipoxygenase (LOX) enzyme | Rhein and kaempferol | [7] |

| (4) | Leaves | Thailand | To manage diabetes and weight | Aqueous | Antilipogenic | High-fat diet-induced obese mice | [57] | |

| (5) | Leaves | India | Treatment of bacterial infections | Methanol | Antibacterial | Pathogenic bacterial strains | [58] | |

| (6) | Leaves | Cameroon | Treatment of gonorrhoea, gastrointestinal and skin diseases | Methanol | Antibacterial | Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Vibrio cholerae and Shigella flexneri | Kaempferol, luteolin and aloe-emodin | [59] |

| (7) | Leaves | India | To manage diabetes | Methanol | Antidiabetic | α-Glucosidase enzyme | Kaempferol 3-O-gentiobioside | [31] |

| (8) | Leaves | Thailand | Treatment of skin infections | Anthraquinone | Antifungal | STZ-induced diabetic rats | Anthraquinone | [60] |

| (9) | Leaves | Nigeria | To wash the uterus | Hexane | Anti-implantation, antigonadotropic, antiprogesteronic | Ovariectomized female rats | Alkaloids | [61] |

| (10) | Flower | Nigeria | Treatment of urinary tract infections and gonorrhoea | Methanol | Antibacterial | Bacterial strains | Steroids, anthraquinone glycosides, volatile oils and tannin | [62] |

| (11) | Flower | India | To treat scabies and ringworm | Aqueous | Antifungal | Aflatoxin producing and human pathogenic fungi | [63] | |

| (12) | Leaves and barks | Malaysia | To treat superficial fungal infections | Ethanol and water | Antimicrobial | Bacterial and fungal strains | [64] | |

| (13) | Leaves | Cameroon | Ethanol | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory | White blood cells | [30] | ||

| (14) | Leaves | India | Used as purgative expectorant, astringent, vermicide | Ethanol | Anticancer | Male Wistar rats | Alkaloid, flavonoids, saponins, tannins glycosides | [65] |

| (15) | Leaves | Indonesia | Treatment of malaria; antioxidant and antibacterial | Ethanol | Antiviral | DENV-2 and Huh 7it cells | Flavonoid | [66] |

| (16) | Petals | India | As an immune stimulant | Petroleum ether | Immunomodulatory | Garra rufa fish | Cardiac glycosides, phenols, anthraquinone, alkaloids | [67] |

| (17) | Root | Nigeria | As an abortifacient in women, for the termination of early pregnancy | Ethanol | Uterine smooth muscle | Male and female Albino mice | Alkaloids | [68] |

| (18) | Leaves | Burkina Faso | Treatment of asthma-induced bronchospasm | Aqueous and ethanolic | Bronchorelaxant, genotoxic, and antigenotoxic | Male and female Wistar rats | [69] | |

| (19) | Leaves | Egypt | Treatment of skin tumour | Methanol | Antitumor | Human cancer cell lines (HepG2, MDA-MB-231, and Caco2) | Palmitic, linolenic, linoleic, stearic acid | [70] |

| (20) | Leaves | Thailand | Laxative | Methanol | Anti-inflammatory | Tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced oxidative stress in HaCaT cells | Rhein | [71] |

| (21) | Leaves, flower and fruit | Nigeria | Laxative and treatment of microbial infections | Methanol and ethanol | Antifungal and antibacterial | Clinical bacterial and fungal isolates | Flavonoids | [72] |

| (22) | Leaves | Thailand | In regulating glucose level in the blood | Aqueous | Antilipogenic | Male ICR mice | [73] | |

| (23) | Leaves | Cameroon | To cure fever | Aqueous and methanolic | Antiplasmodial | RPMI 1640 and albumax | [74] |

3.4.1. Antibacterial Activities

The antibacterial potentials of medicinal herbs are appraised using zone of inhibition (ZOI) or minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The in vivo antibacterial potential of S. alata was assessed against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), extended spectrum beta-lactamase, and carbapenemase-resistant. Enterobacteriaceae was isolated from infectious patients, via Mueller–Hinton broth via the microdilution technique. The extract showed significant activities at 512 mg/ml due to the flavonoids, quinones, tannins, sterols, alkaloids, and saponins analysed [75]. S. alata leaves collected from an Indian aboriginal tribe, displayed significant ZOI of 21 to 27 mm against clinical isolates of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, obtained from infected patients, when subjected to ASTs via Kirbye Bauer's disc diffusion assay (KBDD) [58].

Ciprofloxacin (30 μg/disc) and vacuum liquid chromatographic (VLC) fractions of S. alata methanolic extract were assessed against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus (Gram positive), Shigella boydii, Shigella dysenteriae, Pseudomonas aureus, Vibrio mimicus, Salmonella paratyphi, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Salmonella typhi, (Gram negative) using the disc diffusion assay. The fractions exhibited significant inhibitory activities against bacteria isolates at 100 µg/ml [76].

Bioactive compounds such as kaempferol, luteolin, and aloe emodin isolated from the methanolic leaves extract was assessed against MDR bacteria strains. Aloe emodin exhibited strong MIC activities (4 to 128 μg/ml). The marked activities could be linked to the anthraquinone and flavonoids compounds detected [59]. The antibacterial activity of chrysoeriol-7-O-(2″-O-beta-D-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-allopyranoside,3-O-gentiobioside, quercetin, naringenin, and rhamnetin-3-O-(2″-O-beta-D-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-allopyranoside isolated from chloroform, ethanol, petroleum ether, methanol, and aqueous leaves extract of S. alata, significantly inhibited the growth of B. subtilis, V. cholerae, Streptococcus sp., S. aureus, and E. coli. The extracts displayed pronounced activities which are in close proximity to penicillin, chloramphenicol, fluconazole, and ciprofloxacin [77].

Anthraquinone and flavonoid glycosides detected in S. alata extracts significantly inhibited the growth of E. coli and S. aureus with ZOI between 9.7 and 14.8 mm [22, 23]. The crude extracts and isolates obtained from purified fractions of S. alata flower extract (anthraquinone glycosides, steroids, tannins, and volatile oils) were assessed on selected bacteria isolates. Strong inhibitory activities were displayed at MIC of 500 mg/ml against the clinical isolates of S. faecalis, B. subtilis, S. aureus, Pseudomonas putida, and M. Luteus. At 500 mg/ml, ZOI of 10 to 25 mm was observed, with close proximity to the inhibitory activities displayed by streptomycin, penicillin, and methicillin [41]. The synergic effect of Eugenia uniflora and S. alata leaves was examined on clinical isolates of B. subtilis and S. aureus. The dried leaves were processed into a local antiseptic herbal soap and the antibacterial potential was assessed via hole-in-plate agar diffusion assay. The herbal soap significantly inhibited the growth of the tested organisms [78].

3.4.2. Antioxidant Activities

The antioxidant or scavenging activities is important in appraisal of therapeutic potential of medicinal herbs. Plants played significant role in protecting cell against oxidative stress caused by active free radicals [79]. The free radical scavenging potentials of plants are appraised by antibiotic sensitivity tests (ASTs); 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH); ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP); 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS); hydroxyl radical scavenging activity (HRSA), and metal ion chelating activity (MICA). The methanolic and n-hexane leaves extracts of S. alata were explored for their scavenging effects via DPPH assay. The methanolic extract displayed pronounced scavenging activities when compared to n-hexane extract. The methanolic extract was fractionated, leading to isolation of three major bioactive compounds (kaempferol, butylated hydroxytoluene, and emodin). The kaempferol fraction displayed pronounced scavenging activity than the butylated hydroxytoluene and emodin fractions [80]. Several bioactive compounds such as ascorbic acid, flavonoids, tocopherol, anthraquinone, and carotene assessed contributed to scavenging activities displayed [77].

Different parts of S. alata, significantly inhibited the action of free radicals causing oxidative stress [82]. The in vitro DPPH assay of ethyl acetate-DCM, methanol-DCM, and oil fractions of S. alata leaves was assessed using L-ascorbic acid as control. The radical scavenging activities measured at 517 nm significantly inhibited the free radicals at 500 g/ml. The concentration at 50% inhibition (IC50) of the fractions revealed activities of methanol-DCM (65.03%), ethyl acetate-DCM (62.33%), and oil fraction (64.10%). The strong scavenging activities could be due to polyphenol and flavonoid analysed [76].

3.4.3. Antifungal Activities

Several bioactive compounds isolated from S. alata exhibit strong in vitro and in vivo antifungal activities. The antifungal activities of cannabinoid alkaloid (4-butylamine 10-methyl-6-hydroxy cannabinoid dronabinol), 1,8-cineole, caryophyllene, limonene, α-selinene, β-caryophyllene, germacrene D, hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, hexadecanoic acid, (6Z)-7,11-dimethyl-3-methylidenedodeca-1,6,10-triene, octadecanoic acid methyl ester, cinnamic acid, 3,7-dimethylocta-1,6-diene, pyrazol-5-ol, flavonol and gallic acid, methaqualone, and isoquinoline have been explored [51,83–85].

Volatile oils extracted from S. alata flowers were assessed against standard strains and clinical isolates of Candida and Aspergillus species. The oils significantly inhibited the growth of the tested microbes [86]. The methanolic extract and purified n-hexane and ethanolic fractions of S. alata flower displayed strong inhibitory activities against A. Niger, C. utilis, G. candidum, A. brevipes, and Penicillium species with an MIC of 0.312 to 5 mg/ml. However, at different concentrations, the purified fractions exhibited prominent inhibitory activities than the methanolic extracts. Likewise, mycelia growth was significantly inhibited by the purified fractions, with a total suppression of sporulation for 96 h at 2 mg/ml, compared to less sporulation after 48 h for methanolic extracts [87].

The aqueous and ethanolic leaf and bark extracts of S. alata was assessed via disc diffusion assay against M. canis, C. albicans, and A. fumigatus. The bark extracts displayed prominent concentration-dependent susceptibility against C. albicans. On the contrary, the aqueous extract showed a strong ZOI of 12 and 16 mm, while ethanolic extracts exhibited 10 and 14 mm. However, tioconazole displayed strong inhibitory activities of 18 mm which are significantly higher than the extracts at equivalent concentration [64].

S. alata flowers and leaves collected from Ogbomoso, Southwest Nigeria, were examined in an attempt to justify the indigenous claims of its antifungal efficacy. In vitro antifungal activities of ethanolic and methanolic extracts were investigated using the disc diffusion approach. Ethanolic extracts showed pronounced inhibitory activities when compared to methanolic extracts. The IC50 value of the ethanolic extract was two folds higher than the methanolic extracts against the fungi isolates. The inhibitory activities displayed could be due to methaqualone, cinnamic acid, isoquinoline, and toluidine detected [71].

3.4.4. Dermatophytic Activities

Currently, the leaves, flowers, and bark of S. alata are used for treating various kinds of skin infections and diseases. In Thailand, the plant was mentioned as one of the 54 medicinal plants used for treating scabies, shingles, urticarial, itching, pityriasis versicolor, and ringworm [88]. The dermatophytic activities displayed by S. alata are linked to the bioactive compounds such as anthranols, anthrones, flavonoids, phenols, tannins, and anthracene derivatives [89]. Leaves decoction displayed strong inhibitory activities against S. pyogenes, S. aureus, K. pneurnoniae, E. coli, S. rnarcescens, P. cepacia, and P. aeruginosa [90, 91].

Cannabinoid alkaloid (4-butylamine 10-methyl-6-hydroxy cannabinoid dronabinol) and apigenin isolated from S. alata seeds were incorporated in a local antiseptic soap. The soap significantly hindered the spread of ringworms, eczemas, carbuncles, boils, infantile impetigo, and breast abscess [84]. The leaf, stem-bark, flower exudates, and ethanolic leaf extract examined against clinical isolates of T. jirrucosum, M. canis, T. mentagrophyte, E. jlorrcosum, B. dermatitidis, A. flavus, and C. albicans displayed strong inhibitory activities against the causative organisms [18,92–94].

3.4.5. Antilipogenic, Antidiabetic, and Antihyperlipidemic Activities

In Africa and Asia, S. alata leaves and flowers are currently used to regulate lipid absorption, obesity, and fat levels in blood serum. Aqueous leaf extract considerably reduced blood glucose levels, serum cholesterol, triglyceride, hepatic triglyceride, serum leptin, and insulin levels in Wistar mice [57].

Diabetes is a threat to man leading to stern socio-economic and high rate of mortality [95]. Herbal decoction of S. alata is commonly used in Caribbean [96], Africa [34], and India [97] for the treatment of diabetes. The marked α-glucosidase inhibitory effect and antidiabetic activities displayed by S. alata are linked to bioactive compounds such as astragalin and kaempferol-3-O-gentiobioside [31, 98]. Traditionally, the leaves decoction is used in regulation of sugar level in serum [99] and enhances the defence of hepato and renal organs to oxidative stress [56]. It also reduces fasting blood glucose and improves metabolic state via activation of PKB/Akt which helps regulate glucose uptake in the liver and muscles [100].

The antidiabetic potency of acarbose, n-butanol, and ethyl acetate fractions of methanolic S. alata leaf extract was assessed via inhibitory carbohydrate digestion mechanism. The antidiabetic drug (acarbose) significantly inhibits α-glucosidase with inhibitory concentration (IC50, 107.31 ± 12.31 µg/ml). n-Butanol and ethyl acetate fractions displayed inhibitory activities of IC50, 25.80 ± 2.01 µg/ml and IC50, 2.95 ± 0.47 µg/ml, respectively, due to kaempferol 3-O-gentiobioside analysed by HPLC and Combiflash chromatography [31, 83]. α-Amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory potential of acetone, hexane, and ethyl acetate leaf extracts of S. alata was assessed via Lineweaver–Burk plot. Acetone extract significantly inhibited α-amylase (IC50 = 6.41 mg/mL), while hexane displayed strong inhibition against α-glucosidase (IC50 = 0.85 mg/mL). n-Hexane substantially reduces (p < 0.05) postprandial blood glucose in sucrose-induced rats after 2 h of treatment [101].

The reduction in the oxidative stress in the aorta and heart of streptozotoc, hyperglycemic rats was investigated by DPPH free radical scavenging and antioxidant catalase assays. The aqueous leaf extract significantly reduced lipid peroxidation (MDA levels), blood glucose; however, it increases in the antioxidant catalase and DPPH free radical scavenging activity was observed. The reversal of oxidative stress induced by cardiac dysfunction in hyperglycemic condition justified the ethnobiological claim of the plant [102]. In a similar study, the S. alata leaf extract significantly reduces oxidative stress causing diabetes in treated mice. Prominent activities were observed in the kidney and liver. The activity resulted in critical changes in the urea, protein, creatinine, and uric acid level in the blood serum [56].

3.4.6. Antimalarial Activities

Malaria is a global threat contributing to serious sociocultural and health issues in humid and tropical regions [103, 104]. Chemotherapy reported the antimalarial activities of S. alata could be linked to quinones, alkaloids, and terpenes [105, 106]. Quinones isolated from S. alata significantly displayed in vitro antiplasmodial activity, against Plasmodium falciparum via the microdilution test of Desjardin [107]. Terpenes isolated from S. alata leaves displayed pronounce in vitro antiplasmodial assays against P. falciparum in ethylene glycol-water fractions. Significant activity was observed at concentration below 1 µg/ml [108]. The appraisal of aqueous leaf extract justifies the ethnomedical applications of S. alata as remedy for malaria and fever. The leaf extract considerably inhibited 3D7 strain of the P. falciparum parasite in Wistar mice [109].

3.4.7. Anthelmintic Activity

Traditionally, S. alata leaf and flower decoctions are used in treatment of intestinal worm infestation and stomach disorder. The anthelmintic potency of alcoholic leaves extract of S. alata and T. angustifolia at 10 to 100 mg/ml were assessed in clinical isolates of Ascardia galli and Pheretima posthuma by observing time of paralysis and point of death of the worms. The leaves extract significantly inhibit the worms (test organisms) more than piperazine citrate (standard anthelmintic drug) [110].

3.4.8. Antiviral Activities

S. alata is an indispensable bactericidal and fungicidal natural therapy. However, the justification of antiviral activities is not properly documented. The antiviral efficacy of n-hexane, ethyl acetate, butanol, and aqueous leaf extracts was assessed on dengue virus (DENV) obtained from an infected pregnant woman in Indonesia via focus assay. The extracts significantly inhibited DENV-2 with IC50 (<10 μg/ml), CC50 (645.8 μg/ml) and SI (64.5 μg/ml) [111].

4. Nutritional Constituents of S. alata

In appraisal of the therapeutic potentials of medicinal herbs, phytochemical, pharmacological, toxicological, and nutritional details are indispensable. In appraisal of the nutritional constituents of S. alata leaf, several nutrients assessed include moisture content (9.53 ± 0.06), carbohydrate (298.61 ± 0.40), crude lipid (47.73 ± 0.01), crude fibre (18.23 ± 0.13), and ash (15.73 ± 0.03). The nutritional contents analysed in flower revealed ash (7.00 ± 1.0), crude protein (13.14 ± 0.02), carbohydrate (57.04 ± 0.04), moisture (6.16 ± 0.14), and crude lipid (1.81 ± 0.09). It is observed that storage capacity, easy absorption of food, antimicrobial and anaesthetic properties are connected to the nutritional composition of herbs [112]. Several minerals such as potassium, iron, manganese, calcium, zinc, copper, and chromium have been assessed in S. alata. These mineral constituents help in formulation of herbal drugs and dietary supplements [113–115].

5. Toxicological Studies of S. alata

Lately, medicinal plants and herbal products have come under spotlight owing to health hazards connected to indiscriminate handling of herbs and herbal products. Several reports were published relating to the use of herbal drugs. Despite the risks ascribed to most medicinal and herbal products, the number of herbal users still increases. This initiates the appraisal of herbs in an attempt to establish their safety [116]. The S. alata leaf extract was appraised by oral administration of Wistar rats (10 g/kg weight). The acute and subacute effects were assessed in every 24 h for 14 days at different dosages (250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg). After 24 h, no significant variation was observed in the liver, urea, bicarbonate, creatinine, and kidney of the tested organisms and control [117]. Aqueous flower extract at doses of 100, 400, and 800 mg/kg was orally administered to ten Wistar rats for 28 days. No significant difference on histological sections of the lung, liver, kidney, heart, and kidney was observed during the postmortem analysis of the mice [118].

Different doses (1,000, 2,000, and 3,000 mg/kg body weight) of ethanolic leaf extract do not display any behavioural, biochemical, haematological, and histopathological variations in the tested Swiss albino mice and control after 15 days of oral administration [119]. Hydroethanolic leaf extract increased the body weight, blood level, liver homogenates, and serum index after proper monitoring of the administered rats every 48 h for 26 days. Haematological parameters assessed displayed dose-dependent response, however, no significant variation was observed in liver histopathology [120]. Alkaloids isolated from aqueous S. alata leaf extract significantly reduces alkaline phosphate, uric acid, globulin, liver and kidney body weight ratio, urea, phosphate ions, bilirubin, potassium ions, serum concentrations of albumin, creatinine, gamma glutamyl transferase, alanine transaminases, and aspartate in the liver and kidney of pregnant rats after periodic observation for 18 days. This led to variation in serum enzymes, excretory, and secretory functions of liver and kidney of the test organisms [61].

Documented toxicological appraisals of S. alata present positive information regarding its safety; however, there is need to authenticate these reports through in vitro and in vivo assessments on clinical isolate. Fresh and dried plant parts, low-dosage concentrations, test organisms of different age groups and effect on other vital organs such as brain, intestine, and bladder should be considered during toxicological appraisals of medicinal plant or products. Ethnobiological appraisals described that ulcer patients, pregnant women, and children under the age of two should avoid S. alata decoction. Also, studies should be focused on appraisals of recommended dosage, safest mode of administration, and reaction mechanisms of the metabolites in living organisms.

6. Limitation, Conclusion, and Future Prospects

Based on this review, further studies on S. alata have become evident. Most studies focused on lipid-soluble and volatile components; however, appraisals on metabolites prepared in hydrophilic medium are deficient. Most phytochemical studies of S. alata focused on leaves, stems, and flowers, though study on seeds and roots are lacking. Many therapeutic appraisals have been investigated in cell and animal experiments; still, there remain important tasks. These include secondary metabolites dictating the pharmacological activities are not well stated; relatively, few studies analytically appraised the mechanisms of action of secondary metabolites; systemic toxicological studies remain ambiguous. The phytochemical appraisals revealed there is a variation in some metabolites investigated due to geographical and climatic factors. This gives room for qualitative approach to authenticate the metabolites in this plant. The plant secondary metabolites contributed to the pronounced wound healing and antibacterial and antifungal activities [92, 121]. Industrially, the plant is a key ingredient in detergents (foaming and surface active agents), molluscicides and pesticides. Summarily, comprehensive ethnobiological and pharmacological activities of S. alata, limitations, and future prospects were explored which could present novel research directions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the Department of Physical Sciences, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences, Landmark University, Omu-Aran, Nigeria.

Abbreviations

- ZOI:

Zone of inhibition

- MIC:

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MDR:

Multidrug resistant

- ASTs:

Antibiotic sensitivity tests

- DPPH:

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- FRAP:

Ferric-reducing antioxidant power

- ABTS:

Chemiluminescence, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)

- HRSA:

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

- MICA:

Metal ion chelating activity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Oladeji O. S., Odelade K. A., Oloke J. K. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial investigation of Moringa oleifera leaf extracts. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development. 2019;12(1):79–84. doi: 10.1080/20421338.2019.1589082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Frontier of Pharmacology. 2013;4:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO (World Health Organization) Global Report on Diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verpoorte R. Forward. In: Mukherjee P. K., editor. Evidence-Based Validation of Herbal Medicine. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svahn S. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University; 2015. Analysis of secondary metabolites from Aspergillus fumigatus and Penicillium nalgiovense; p. p. 195. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Pharmacy. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balunas M. J., Kinghorn A. D. Drug discovery from medicinal plants. Life Sciences. 2005;78(5):431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh B., Nadkarni J. R., Vishwakarma R. A., Bharate S. B., Nivsarkar M., Anandjiwala S. The hydroalcoholic extract of Cassia alata (Linn.) leaves and its major compound rhein exhibits antiallergic activity via mast cell stabilization and lipoxygenase inhibition. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;141(1):469–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veeresham C. Natural products derived from plants as a source of drugs. Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technological Research. 2012;3(4):200–201. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.104709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A., Shukla R., Singh P., Prasad C. S., Prasad N. K. Assessment of Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil as a safe botanical preservative against post harvest fungal infestation of food commodities. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 2008;9(4):575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2007.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu A., Xu L., Zou Z., et al. Studies on chemical constituents from leaves of Cassia alata. China Journal of Chinese Matters on Medicine. 2009;34:861–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khare C. P. Indian Medicinal Plants: An Illustrated dictionary. London, UK: Springer Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang C. V., Felício A. C., Reis J. E. D. P., Guerra M. D. O., Peters V. M. Fetal toxicity of Solanum lycocarpum (Solanaceae) in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;81(2):265–269. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackland M., van de Waarsenburg S., Jones R. Synergistic antiproliferative action of the flavonols quercetin and kaempferol in cultured human cancer cell lines. In Vivo. 2004;19:69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi E. J., Ahn W. S. Kaempferol induced the apoptosis via cell cycle arrest in human breast cancer MDA-MB-453 cells. Nutrition Research and Practice. 2008;2(4):322–325. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2008.2.4.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandyopadhyay S., Romero J. R., Chattopadhyay N. Kaempferol and quercetin stimulate granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor secretion in human prostate cancer cells. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2008;287(1-2):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernand V. E., Losso J. N., Truax R. E., et al. Rhein inhibits angiogenesis and the viability of hormone-dependent and -independent cancer cells under normoxic or hypoxic conditions in vitro. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2011;192(3):220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aviello G., Rowland I., Gill C. I., et al. Anti-proliferative effect of rhein, an anthraquinone isolated from Cassia species, on Caco-2 human adenocarcinoma cells. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2009;14:2006–2014. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makinde A. A., Igoli J. O., TA’Ama L., et al. Antimicrobial activity of Cassia alata. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2007;6(13):1509–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarkang P. A., Agbor G. A., Armelle T. D., et al. Acute and chronic toxicity studies of the aqueous and ethanol leaf extracts of Carica papaya Linn in Wistar rats. Journal of Natural Product and Plant Resources. 2012;2(5):617–627. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aftab K., Ali M. D., Aijaz P., et al. Determination of different trace and essential element in lemon grass samples by X-ray flouresence spectroscopy technique. International Food Research Journal. 2011;18:265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villaseñor I. M., Canlas A. P., Pascua M., et al. Bioactivity studies on Cassia alata Linn. leaf extracts. Phytotherapy Research. 2002;16(1):93–96. doi: 10.1002/ptr.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan M. R., Kihara M., Omoloso A. D. Antimicrobial activity of Cassia alata. Fitoterapia. 2001;72(5):561–564. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somchit M. N., Reezal I., Nur I. E., Mutalib A. R. In vitro antimicrobial activity of ethanol and water extracts of Cassia alata. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;84(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donatus E. O., Fred U. N. Cannabinoid Dronabinol alkaloid with antimicrobial activity from Cassia alata Linn. Der Chemica Sinica. 2010;2(2):247–254. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranganathan S., Balajee S. A. Anti-cryptococcus activity of combination of extracts of Cassia alata and Ocimum sanctum. Mycoses. 2000;43(7-8):299–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2000.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otto R. B., Ameso S., Onegi B. Assessment of antibacterial activity of crude leaf and root extracts of Cassia alata against Neisseria gonorrhea. African Health Science. 2014;14:840–848. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaikwad S. Isolation and characterization of a substituted Anthraquinone: a bioactive compound from Cassia auriculata L. Industrial Journal of Advanced Plant Research. 2014;1(5):8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olarte E. I., Herrera A. A., Villasenor I. M., et al. Antioxidant activity of a new indole alkaloid from Cassia alata L. Philippine Agricultural Scientist. 2010;93(3):250–254. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manogaran M., Sulochana N. Anti-inflammatory activity of Cassia aauriculata. Science Life. 2004;24(2):65–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sagnia B., Fedeli D., Casetti R., et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of extracts from C. alata, E. indica, E. speciosa, C. papaya and P. fulva medicinal plants collected in Cameroon. PLoS One. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103999.e103999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varghese G. K., Bose L. V., Habtemariam S. Antidiabetic components of Cassia alata leaves: identification through α-glucosidase inhibition studies. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2013;51(3):345–349. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2012.729066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Midawa S. M., Ali B. D., Mshelia B. Z., et al. Cutaneous wound healing activity of the ethanolic extracts of the leaf of Senna alata L (Caesalpiniaceae) Journal of Biological Science and Bioconservation. 2010;2 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kundu S., Roy S., Lyndem L. M. Cassia alata L: potential role as anthelmintic agent against Hymenolepis diminuta. Parasitology Research. 2012;111(3):1187–1192. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abo K. A., Fred-Jaiyesimi A. A., Jaiyesimi A. E. A. Ethnobotanical studies of medicinal plants used in the management of diabetes mellitus in South Western Nigeria. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;115(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farnsworth N. R., Bunyapraphatsara N. Thai Medicinal Plants. Recommended for Primary Health Care System. Salaya, Thailand: Medicinal Plant Information Center, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mahidol University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennebelle T., Weniger B., Joseph H., Sahpaz S., Bailleul F. Senna alata. Fitoterapia. 2009;80(7):385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar V. R., Kumar S., Shashidhara S., et al. Comparison of the antioxidant capacity of an important hepatoprotective plants. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Drug Research. 2011;3:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oladeji O. S., Adelowo F. E., Ayodele D. T., Odelade K. A. Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Cymbopogon citratus: a review. Scientific African. 2019;6 doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00137.e00137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross I. A. Medicinal Plants of the World. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palanichamy S., Nagarajan S. Analgesic activity of Cassia alata leaf extract and kaempferol 3-o-sophoroside. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1990;29(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(90)90099-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adedayo O., Anderson W. A., Moo-Young M., Snieckus V., Patil P. A., Kolawole D. O. Phytochemistry and antibacterial activity of Senna alata flower. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2001;39(6):408–412. doi: 10.1076/phbi.39.6.408.5880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Mahmood A. M., Doughari J. H., Chanji F. J. In vitro antibacterial activities of crude extract of Nauclea latifolia and Daniella oliver. Scientific Research Essays. 2003;31(3):102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benjamin T. V., Lamikanra A. Investigation of Cassia alata, a plant used in Nigeria in the treatment of skin diseases. Quarterly Journal of Crude Drug Research. 2008;19(2-3):93–96. doi: 10.3109/13880208109070583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oguntoye S. O., Owoyale J. A., Olatunji G. A. Antifungal and antibacterial activities of an alcoholic extract of S. alata leaves. Journal of Applied Science and Environmental Management. 2005;9(3):105–107. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogunti E. O., Elujobi A. A. Laxative activity of Cassia alata. Fitoterapia. 1993;64(5):437–439. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leung L., Riutta T., Kotecha J., Rosser W. Chronic constipation: an evidence-based review. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2011;24(4):436–451. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.04.100272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Day R. A., Underwood A. L. Quantitative Analysis. 5th. London, UK: Prentice-Hall Publication; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Igoli J. O., Ogaji O. G., Tor-Anyiin T. A., et al. Traditional medicinal practices among the Igede people of Nigeria (part II) African Journal of Traditional Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005;2(2):134–152. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v2i2.31112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selvi V., Isaivani V., Karpagam S. Studies on antimicrobial activities from flower extract of Cassia alata Linn. International Journal of Current Science. 2012;2:299–303. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chauhan K. N., Patel M. B., Valera H. R., et al. Hepatoprotective activity of flowers of Cassia auriculata R. against paracetamol induced liver injury. Journal of Natural Remedies. 2009;9:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oladeji S. O., Adelowo F. E., Odelade K. A. Mass spectroscopic and phytochemical screening of phenolic compounds in the leaf extract of Senna alata (L.) Roxb. (Fabales: Fabaceae) Brazilian Journal of Biological Sciences. 2016;3(5):209–219. doi: 10.21472/bjbs.030519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dalziel J. M. Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa. London, UK: Crown Agents for Overseas Governments; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woradulayapinij W., Soonthornchareonnon N., Wiwat C. In vitro HIV type 1 reverse transcriptase inhibitory activities of Thai medicinal plants and Canna indica L. rhizomes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;101(1–3):84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ajibesin K. K., Ekpo B. A., Bala D. N., Essien E. E., Adesanya S. A. Ethnobotanical survey of Akwa ibom state of Nigeria. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;115(3):387–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yakubu M. T., Adeshina A. O., Oladiji A. T., et al. Abortifacient potential of aqueous extract of S. alata leaves in rats. Journal of Reproduction and Contraception. 2010;21(3):163–177. doi: 10.1016/s1001-7844(10)60025-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugumar M., Victor D., Dossb A., et al. Hepato-renal protective effects of hydroethanolic extract of S. alata on enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant systems in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Integrative Medicine Research. 2016;5:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naowaboot J., Somparn N., Saentaweesuk S., et al. Umbelliferone improves an impaired glucose and lipid metabolism in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic rats. Phytotherapy Research. 2015;29:1388–1395. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swain S. S., Padhy R. N. In vitro antibacterial efficacy of plants used by an Indian aboriginal tribe against pathogenic bacteria isolated from clinical samples. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2015;10(4):379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2015.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tatsimo S. J. N., Tamokou J.-d.-D., Tsague V. T., et al. Antibacterial-guided isolation of constituents from Senna alata leaves with a particular reference against multi-drug-resistant Vibrio cholerae and Shigella flexneri. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences. 2017;11(1):46–53. doi: 10.4314/ijbcs.v11i1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wuthi-udomlert M., Kupittayanant P., Gritsanapan W. In vitro evaluation of antifungal activity of anthraquinone derivatives of S. alata. Journal of Health Research. 2010;24(3):117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yakubu M. T., Musa I. F. Effects of post-coital administration of alkaloids from S. alata (Linn. Roxb) leaves on some fetal and maternal outcomes of pregnant rats. Journal of Reproduction and Infertility. 2012;13(4):211–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abubacker M. N., Ramanathan R., Kumar T. S. In vitro antifungal activity of Cassia alata Linn flower extract. Natural Products Radiance. 2008;7(1):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kudatarkar N. M., Nayak Y. K. Pharmacological screening of Cassia alata leaves on colorectal cancer. Colorectal Cancer. 2018;4(1):p. 2. doi: 10.21767/2471-9943.100049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Somchit M. N., Mutalib A. R. Tropical medicine. Plants. 2003;2(2):179–182. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marissa A., Muhammad H., Franciscus D., et al. Antiviral effect of sub fraction Cassia alata leaves extract to dengue virus serotype-2 strain new guinea C in human cell line huh-7 it-1. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2017;101 doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/101/1/012004.012004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jayasree R., Prathiba R., Sangavi S. Immunomodulatory effect of Cassia alata petals in Garra rufa (doctor fish) Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2016;9(1):215–218. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adedoyin T. A., Joshua I. O., Ofem O. E., et al. Effects of Cassia alata root extract on smooth muscle activity. British Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2015;5(6):406–418. doi: 10.9734/bjpr/2015/14457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ouédraogo M., Da F., Fabré A., et al. Evaluation of the bronchorelaxant, genotoxic, and antigenotoxic effects of Cassia alata L. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:11. doi: 10.1155/2013/162651.162651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mohammed M. M., El-Souda S. S., El-Hallouty S. M., et al. Antiviral and cytotoxic activities of anthraquinones isolated from Cassia roxburghii Linn. leaves. Herba Polonica. 2013;59(4):33–44. doi: 10.2478/hepo-2013-0022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wadkhien K., Chinpaisal C., Satiraphan M., et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of rhein and crude extracts from Cassia alata L. in HaCaT cells. Science, Engineering and Health Studies. 2018;12(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adelowo F., Oladeji O. An overview of the phytochemical analysis of bioactive compounds in S. alata. American Chemical and Biochemical Engineering. 2017;2(1):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Naowaboot J., Piyabhan P. S. alata leaf extract restores insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Clinical Phytoscience. 2016;2:p. 18. doi: 10.1186/s40816-016-0035-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Josué W. P., Nadia N. A., Claire K. M., et al. In Vitro sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates to methanolic and aqueous extracts of Cassia alata (Fabaceae) Alternative Integrative Medicine. 2014;3:p. 2. doi: 10.4172/2327-5162.1000159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trease G. E., Evans W. C. Phenols and phenolic glycosides. In: Trease G. E., Evans W. C., editors. Pharmacognosy. London, UK: Biliere Tindall; 1996. pp. 832–833. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wikaningtyas P., Sukandar E. Y. The antibacterial activity of selected plants towards resistant bacteria isolated from clinical specimens. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2016;6(1):16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2015.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saha B. K., Bhuiyan M. N., Mazumder K., et al. Hypoglycemic activity of Lagerstroemia speciose L. extract on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat: underlying mechanism of action. Bangladesh Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;4(2):79–83. doi: 10.3329/bjp.v4i2.1539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chatterjee S., Dutta S. An Overview on the ethnophytopathological studies of Cassia alata-an important medicinal plant and the effect of VAM on its growth and productivity. International Journal of Research on Botany. 2012;2(4):13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oyedele O. A., Ezekiel C. N., Sulyok M., et al. Mycotoxin risk assessment for consumers of groundnut in domestic markets in Nigeria. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2017;251:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu Y. Z., Huang S. H., Tan B. K., et al. Antioxidants in Chinese herbal medicines: a biochemical perspective. Natural Products Representation. 2004;21:478–489. doi: 10.1039/b304821g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Panichayupakaranant P., Kaewsuwan S. Bioassay-guided isolation of the antioxidant constituent from Cassia alata L. leaves. Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology. 2004;26(1):103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chatterjee S., Chatterhee S., Dey K., et al. Study of antioxidant activity and immune stimulating potency of the ethnomedicinal plant, Cassia alata (L.) Roxb. Medical Aromatic Plants. 2013;2(4):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sarkar B., Khodre S., Patel P., et al. HPLC analysis and antioxidant potential of plant extract of Cassia alata. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology. 2014;4(1):4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tcheghebe O. T., Tala V. R., Tatong F. N., et al. Ethnobotanical uses, phytochemical and pharmacological profiles, and toxicity of Cassia alata L. an overview. Landmark Research Journal of Medicine and Medical Science. 2017;4(2):16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Okwu D. E., Nnamdi F. U. Cannabinoid dronabinol alkaloid with antimicrobial activity from Cassia alata Linn. Der Chemica Sinica. 2011;2(2):247–254. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ogunwande I. A., Flamini G., Cioni P. L., et al. Aromatic plants growing in Nigeria: essential oil constituents of Cassia alata (Linn.) roxb. And Helianthus annuus L. Records of Natural Products. 2010;4(4):211–217. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Essien E. E., Walker T. M., Ogunwande I. A., et al. Volatile constituents, antimicrobial and cytotoxicity potentials of three Senna species from Nigeria. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants. 2011;14(6):722–730. doi: 10.1080/0972060x.2011.10643995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adedayo O., Anderson W. A., Moo-Young M. Antifungal properties of some components of S. alata flower. Pharmaceutical Biology. 1999;37(5):369–374. doi: 10.1076/phbi.37.5.369.6061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Neamsuvan O. A survey of herbal formulas for skin diseases from Thailand’s three southern border provinces. Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2015;5(4):190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2015.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ramstad E. Modern Pharmacognosy. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown S. H. S. alata, The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Gainesville, FL, USA: University of Florida; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Benjamin T. V., Lamikanra A. Investigation of Cassia alata, a plant used in Nigeria in the treatment of skin diseases. Quarterly Journal of Crude Drug Research. 1981;19(2-3):93–96. doi: 10.3109/13880208109070583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sule W. F., Okonko I. O., Joseph T. A., et al. In vitro antifungal activity of S. alata Linn. crude leaf extract. Research Journal of Biological Science. 2010;5(3):275–284. doi: 10.3923/rjbsci.2010.275.284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ali-Emmanuel N., Moudachirou M., Akakpo J. A., et al. Treatment of bovine dermatophilosis with Senna alata, Lantana camara and Mitracarpus scaber leaf extracts. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;86:167–217. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sule W. F., Okonkwo I. O., Omo-Ogun S., et al. Phytochemical properties and in vitro antifungal activity of Senna alata Linn. crude stem bark extract. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5(2):176–183. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ezuruike U. F., Prieto J. M. The use of plants in the traditional management of diabetes in Nigeria: pharmacological and toxicological considerations. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;155(2):857–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Girón L. M., Freire V., Alonzo A., et al. Ethnobotanical survey of the medicinal flora used by the caribs of guatemala. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1991;34(2-3):173–187. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90035-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Khan M. H., Yadava P. S. Antidiabetic plants used in Thoubal district Nanipur. Northeast India. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 2010;9:510–514. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Adelusi T. A., Oboh G., Ayodele J. A., et al. Avocado pear fruits and leaves aqueous extracts inhibit alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase and SNP induced lipid peroxidation–an insight into mechanisms involve in the management of type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Applied Natural Science. 2014;3(5):21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Palanichamy S., Nagarajan S., Devasagayam M. Effect of Cassia alata leaf extract on hyperglycemic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1988;22:81–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lima C. R., Vasconcelos C. F., Costa-Silva J. H., et al. Anti-diabetic activity of extract from Persea americana mill leaf via the activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;141:517–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kazeem M. I., Azeez G., Ashafa O. Effect of S. alata (L) Roxb (Fabaceae) leaf extracts on alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase and postprandial hyperglycemia in rats. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2015;14(10):1843–1848. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v14i10.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reezal I., Somchif M. N., Abdul R. M. In vitro antifungal properties of Cassia alata. Proceedings of the Regional Symposium on Environment and Natural Resources; April 2002; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Hotel Renaissance Kuala Lumpur; pp. 654–659. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Singh R., Kaur N., Kishore L., et al. Management of diabetic complications: a chemical constituents based approach. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;150:51–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.WHO. World Malaria Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Federici S., Quaratino R., Papale D., et al. Sistema Informatico delleTavole Alsometriche d’Italia, DiSAFRi. Viterbo, Italy: Università Degli Studi Della Tuscia; 2001. http://gaia.agraria.unitus.it. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fowler R. E., Billingsley P. F., Pudney M., et al. Inhibitory action of the antimalarial compound atovaquone (566C80) against Plasmodium berghei ANKA in mosquito, Anopheles stphensi. Parasitology. 1994;108(4):383–388. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000075922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kayembe J. S., Taba K. M., Ntumba K., et al. In vitro anti-malarial activity of 20 quinones isolated from four plants used by traditional healers in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2010;4(11):991–994. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kayembe J. S., Taba K. M., Ntumba K., et al. In vitro antimalarial activity of eleven terpenes isolated from Ocimum gratissimum and Cassia alata leaves screening of their binding affinity with Haemin. Journal of Plant Studies. 2012;1(2):168–172. doi: 10.5539/jps.v1n2p168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vigbedor B. Y., Osafo A. S., Ben A. G., et al. In vitro antimalarial activity of the ethanol extracts of Afzelia africana and Cassia alata commonly used as herbal remedies for malaria in Ghana. International Journal of Novel Research in Life Science. 2015;2(6):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Anbu J., Anita M., Sathiya R., et al. In Vitro Anthelmintic activity of leaf ethanolic extract of Cassia alata and Typha angustifolia. MSRUAS-SASTech Journal. 2013;14(2):41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Angelina A., Hanafi M., Suyatna F., et al. Antiviral effect of sub fraction Cassia alata leaves extract to dengue virus Serotype-2 strain new guinea C in human cell line Huh-7 it-1. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2017;101 doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/101/1/012004.012004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Owoyale J. A., Olatunji G. A., Oguntoye S. O. Antifungal and antibacterial activities of an alcoholic extract of S. alata leaves. Journal of Applied Science and Environment. 2005;9(3):105–107. doi: 10.4314/jasem.v9i3.17362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gilani A. H., Rahman A. U. Trends in ethnopharmacology. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;100:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Essiett U. A., Bassey I. E. Comparative phytochemical screening and nutritional potentials of the flowers (petals) of S. alata (l) roxb, Senna hirsuta (l.) Irwin and barneby, and Senna obtusifolia (l.) Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2013;3(8):097–101. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Abdulwaliyu I., Arekemase S. O., Bala S., et al. Nutritional properties of S. alata Linn leaf and flower. International Journal of Modern Biological Medicine. 2013;4(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Grollman A. P., Marcus D. M. Global hazards of herbal remedies: lessons from Aristolochia. EMBO Representation. 2016;17:619–625. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ugbogu A. E., Okezie E., Uche-Ikonne C., et al. Toxicity evaluation of the aqueous stem extracts of S. alata in wistar rats. American Journal of Biomedical Research. 2016;4(4):80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Igbe I., Osaze E. Toxicity profile of aqueous extract of Cassia alata flower in wistar rats. Journal of Pharmacy and Bioresources. 2016;13(2):92–102. doi: 10.4314/jpb.v13i2.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roy S., Ukil B., Lyndem L. M. Acute and sub-acute toxicity studies on the effect of S. alata in swiss albino mice. Cogent Biology. 2016;2(1):p. 127. doi: 10.1080/23312025.2016.1272166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rezaei A., Farzadfard A., Amirahmadi A., Alemi M., Khademi M. Diabetes mellitus and its management with medicinal plants: a perspective based on Iranian research. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;175:567–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Onwuliri F. C. Antimicrobial studies of the extracts of Acalypha wllkesiana L. on microorganisms associated with wound and skin infections. West African Journal of Biological Science. 2004;15:15–19. [Google Scholar]