High temperature-mediated stomatal opening involves cross talk with light signaling pathways.

Abstract

High temperature promotes guard cell expansion, which opens stomatal pores to facilitate leaf cooling. How the high-temperature signal is perceived and transmitted to regulate stomatal aperture is, however, unknown. Here, we used a reverse-genetics approach to understand high temperature-mediated stomatal opening in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Our findings reveal that high temperature-induced guard cell movement requires components involved in blue light-mediated stomatal opening, suggesting cross talk between light and temperature signaling pathways. The molecular players involved include phototropin photoreceptors, plasma membrane H+-ATPases, and multiple members of the 14-3-3 protein family. We further show that phototropin-deficient mutants display impaired rosette evapotranspiration and leaf cooling at high temperatures. Blocking the interaction of 14-3-3 proteins with their client proteins severely impairs high temperature-induced stomatal opening but has no effect on the induction of heat-sensitive guard cell transcripts, supporting the existence of an additional intracellular high-temperature response pathway in plants.

Plants experience constant fluctuations in temperature and are increasingly exposed to global heatwaves (Perkins et al., 2012). Despite the importance of temperature for plant growth and development, the molecular mechanisms controlling temperature perception in angiosperms have only recently started to emerge. High temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation has been attributed, in part, to accelerated reversion of the plant photoreceptor phytochrome B (phyB) to its inactive Pr form during long nights and at low light levels (Jung et al., 2016; Legris et al., 2016). PhyB inactivation elevates the abundance of the bHLH transcription factor PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR4 (PIF4), driving auxin biosynthesis and stem elongation (Koini et al., 2009; Franklin et al., 2011; Jung et al., 2016). PIF4 additionally promotes the accumulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) transcript to accelerate flowering in short photoperiods (Kumar et al., 2012). High temperature-mediated up-regulation of FT and HEAT SHOCK PROTEIN70 (HSP70) transcripts involves eviction of the alternative histone, H2A.Z, from nucleosomes. Mutants deficient in the ACTIN-RELATED PROTEIN6 (ARP6) subunit of the SWR1 chromatin-remodeling complex are unable to insert H2A.Z into nucleosomes and therefore display a constitutive warm-temperature transcriptome (Kumar and Wigge, 2010). Induction of HSPs by heat shock in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) protoplasts has further been shown to involve the heat-activated calcium channel CYCLIC NUCLEOTIDE-GATED ION CHANNEL6 (CNGC6; Gao et al., 2012).

Elucidation of plant temperature signaling networks is confounded by the fact that commonly measured physiological outputs of temperature change (stem elongation and flowering time) can be temporally and spatially distant from the temperature perception event, requiring intercellular, intertissue, and interorgan signaling networks. To address this constraint, we have used the Arabidopsis guard cell as a single-cell model to study high temperature-regulated physiological and gene expression responses in parallel. Guard cells surround epidermal pores, termed stomata. They can adjust their turgor in response to environmental stimuli to regulate stomatal aperture, thereby controlling gas and water exchange between leaves at the atmosphere (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003). Stomatal opening is promoted by blue light and involves the phototropin photoreceptors and their downstream target BLUE LIGHT SIGNALING1 (BLUS1; Kinoshita et al., 2001; Takemiya et al., 2013). When grown in well-watered conditions at elevated temperature (28°C), Arabidopsis plants display increased transpiration and architectural adaptations to enhance evaporative cooling (Crawford et al., 2012; Bridge et al., 2013). Greater stomatal conductance has been observed in multiple species exposed to temperatures up to 40°C, although interpreting the effects of temperature on stomatal function in planta is confounded by the effects of temperature on vapor pressure deficit and photosynthesis (Urban et al., 2017). Stomatal aperture can be quantified in isolated epidermises via stomatal bioassays. This approach provides a single-cell system that offers unique advantages for studying thermosensory signaling; cells heat up uniformly, and complications arising from the interplay between increased temperature and humidity are removed. Epidermal strip bioassays have shown that temperatures between 30°C and 45°C drive stomatal opening in faba bean (Vicia faba; Rogers et al., 1979, 1980). Further analyses in protoplasts have shown that elevated temperature (36°C) increases the currents through hyperpolarization-activated K+ channels in guard cell membranes (Ilan et al., 1995). Molecular understanding of this process is limited, but stomatal opening in response to heat stress (38°C) has been shown to involve the production of reactive oxygen species by RESPIRATORY BURST OXIDASE PROTEIN D (RBOHD) in Arabidopsis (Devireddy et al., 2020). Furthermore, FT has been reported to promote stomatal opening (Kinoshita et al., 2011), providing a link between high temperature and stomatal aperture.

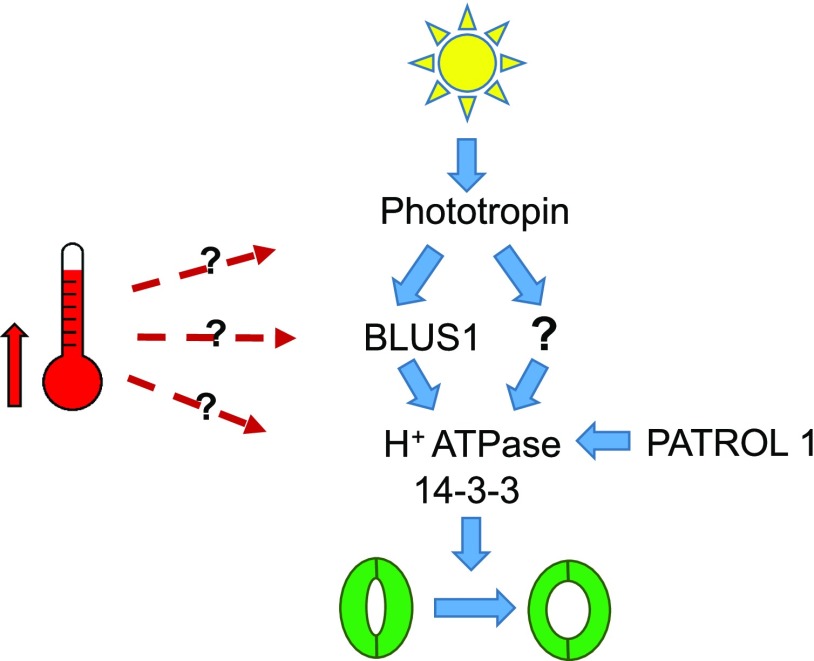

In this study, we report the existence of a high-temperature signaling pathway controlling Arabidopsis guard cell movement that requires phototropins and plasma membrane (PM) H+-ATPase activity for full stomatal opening, yet operates independently from known high-temperature signaling components. Perturbation of this pathway disrupts stomatal opening but not heat-induced transcript accumulation, suggesting either the existence of multiple thermosensing mechanisms or bifurcation of a thermosensory pathway upstream of PM H+-ATPase activation.

RESULTS

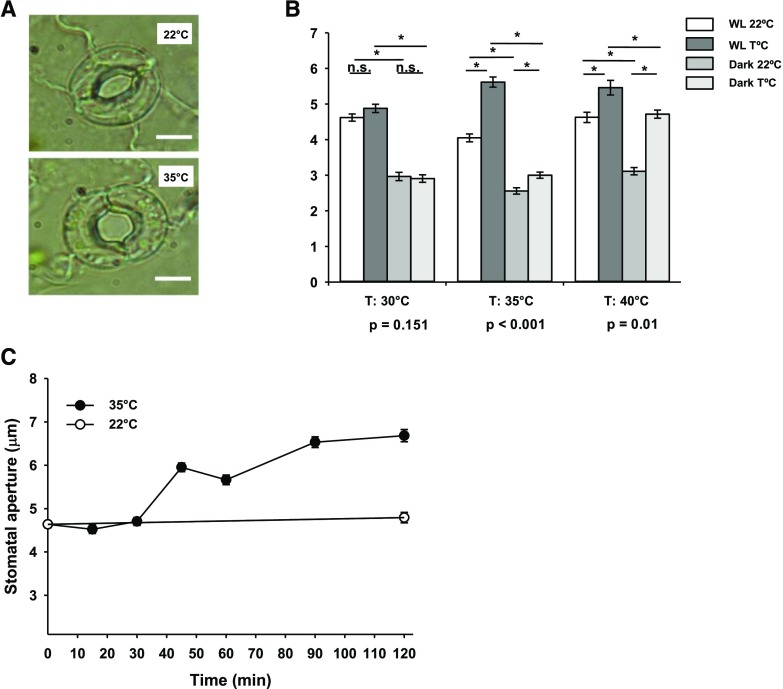

Isolated Guard Cells Respond to High Temperature in the Light and the Dark

Stomatal responses to high temperature were investigated using epidermal peel bioassays to ensure that temperature effects could be analyzed in isolation, without confounding alterations in humidity. High temperature-induced stomatal opening was clearly visible in isolated epidermal tissue containing viable guard cells (Fig. 1A). As the epidermis can no longer receive signals from the mesophyll layer and adjacent pavement cells are ruptured, guard cells must possess the necessary molecular machinery to perceive temperature changes. High temperature-mediated stomatal opening occurred in the light and the dark, with 35°C in the light resulting in the greatest response (Fig. 1B). High temperature-induced stomatal opening was observed in isolated barley (Hordeum vulgare) and Commelina communis epidermises at 40°C (Supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting conservation of this pathway in angiosperms. In Arabidopsis, 35°C treatment had no effect on guard cell viability, as identified by staining with fluorescein diacetate (Supplemental Fig. S2, A–G). Shifting peels from 35°C to 22°C led to statistically significant stomatal closure in the light and the dark, confirming that the response is reversible (Supplemental Fig. S2H). The rapidity of the response was demonstrated in time-course analyses, whereby significant stomatal opening was observed within 45 min (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Isolated Arabidopsis guard cells sense elevations in temperature. A, High temperature induces stomatal opening in isolated epidermal tissue. Representative images of guard cells treated at 22°C and 35°C are shown. Bars = 5 μm. B, Guard cells respond to a range of temperatures in white light and dark conditions. Stomatal bioassays were performed on isolated epidermises from fully expanded rosette leaves. Peels were incubated at 22°C for 2 h followed by incubation at 22°C, 30°C, 35°C, or 40°C for a further 2 h. WL, White light. Error bars indicate se. Asterisks indicate significant differences by Tukey’s posthoc test at P < 0.05 (n = 86–90, measured from three separate leaves, all from different plants). P values from a two-way ANOVA comparing stomatal aperture, with temperature and light as factors, are shown below graphs to highlight whether a significant interaction between light and response to temperature exists. n.s., Not significant. C, Changes in stomatal aperture in response to high temperature are statistically significant within 45 min (P < 0.01). Stomatal bioassays were performed on isolated epidermises maintained in white light. Peels were incubated at 22°C for 2 h before transfer to 35°C. Error bars indicate se (n = 60–90, measured from three separate leaves, all from different plants).

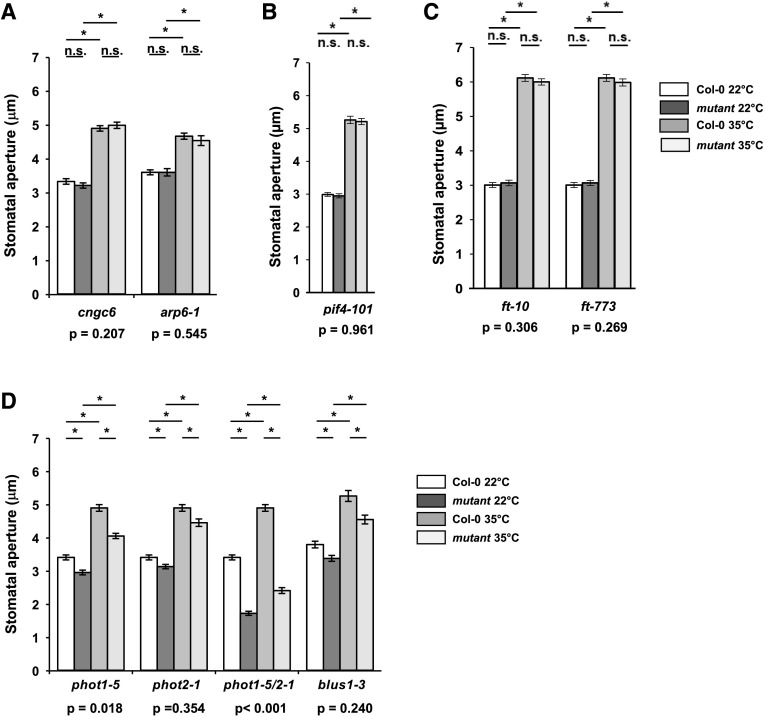

High Temperature-Mediated Stomatal Opening in Isolated Guard Cells Requires Phototropins and PM H+-ATPase Activity

The involvement of known high-temperature signaling components in high temperature-mediated stomatal opening was investigated via stomatal bioassays using the cngc, arp6, pif4, and ft null mutants (Fig. 2, A–C). We considered phyB to be an unlikely candidate for multiple reasons. PhyB is a weak positive regulator of stomatal opening (Wang et al., 2010), so inactivation of phyB at warm temperatures would promote stomatal closure rather than opening (Jung et al., 2016). Thermal reversion of phyB is additionally mostly effective in the dark and at low-light levels (Jung et al., 2016; Legris et al., 2016), whereas the opening of Arabidopsis stomata by 35°C treatment is maximally effective at high-light levels. All of the mutants tested had wild-type apertures at 35°C, suggesting that high temperature-mediated stomatal opening does not involve these known thermosensory mechanisms. Mutants deficient in FT displayed reduced stomatal apertures following transfer from the dark to (red + blue) light, consistent with previous studies (Supplemental Fig. S3; Kinoshita et al., 2011), but showed wild-type stomatal apertures when maintained in white light. The reported thermosensory activity of phototropin photoreceptors (Fujii et al., 2017) led us to additionally investigate the role of phototropins and their downstream target, BLUS1, in high temperature-mediated stomatal opening. Loss of phototropins and BLUS1 resulted in significantly reduced stomatal apertures at 22°C (Fig. 2D). This is consistent with the established roles of these proteins in blue light signaling (Kinoshita et al., 2001; Takemiya et al., 2013). Impaired stomatal opening was most severe in the phot1/2 mutant (Fig. 2D), confirming the redundant action of these photoreceptors (Kinoshita et al., 2001) and suggesting the existence of a phototropin-mediated, BLUS1-independent pathway controlling stomatal opening in plants maintained in white light. All blue light signaling mutants displayed a stomatal opening response to high temperature, but this was strongly impaired in phot1/phot2 mutants, where a significant interaction between genotype and temperature was recorded (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that a small amount of guard cell movement can occur in response to 35°C independently of phototropin, but complete stomatal opening requires phototropin activation. blus1-3 mutants displayed significantly smaller stomatal apertures than wild-type plants at 35°C, suggesting a partial involvement in this response.

Figure 2.

High temperature-induced stomatal opening in isolated guard cells requires phototropin but not components of high-temperature signaling pathways. A to C, Loss-of-function mutants of genes involved in high-temperature signaling have no impairment in stomatal opening at 35°C. D, Phototropins are required for stomatal opening in response to high temperature. Stomatal bioassays were performed on isolated epidermises from fully expanded rosette leaves exposed to white light. Peels were incubated at 22°C for 2 h followed by incubation at 22°C or 35°C for a further 2 h. Columbia-0 (Col-0) controls were carried out in parallel. Error bars indicate se. Asterisks indicate significant differences by Tukey’s posthoc test at P < 0.05 (n = 90, measured from three separate leaves, all from different plants). P values from a two-way ANOVA comparing stomatal apertures, with genotype and temperature as factors, are shown below graphs to highlight whether a significant interaction between genotype and response to temperature exists. n.s., Not significant.

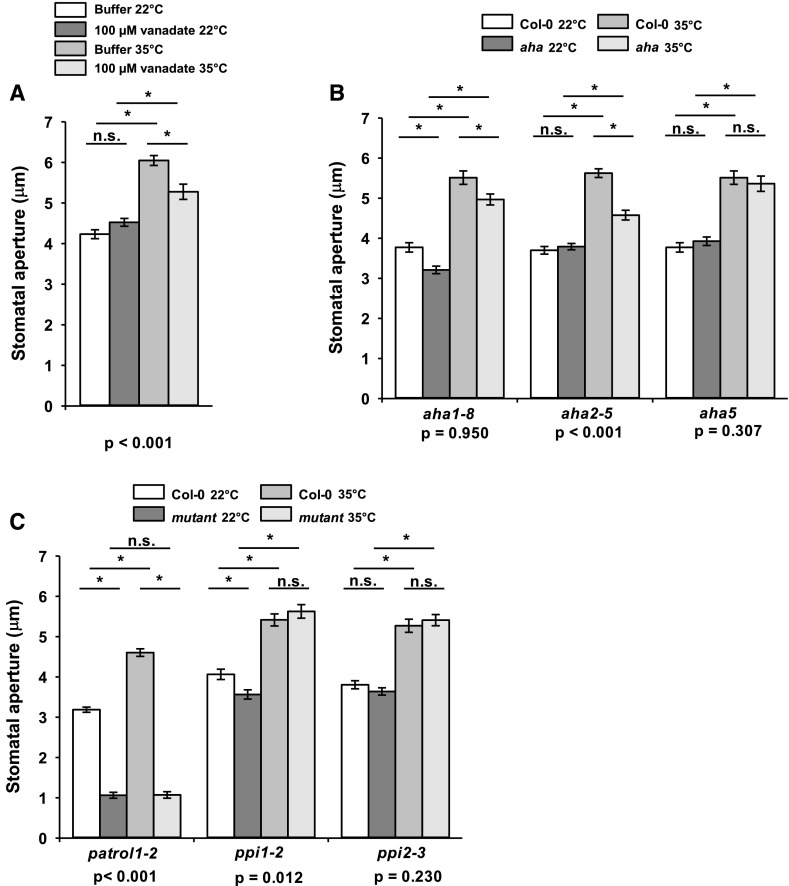

Influx of K+ and water into guard cells increases turgor, increasing stomatal aperture (Outlaw and Lowry, 1977; Kwak et al., 2001). A role for inward K+ channels in guard cell responses to high temperature has been reported (Ilan et al., 1995), so we decided to investigate potential upstream regulators. A requirement for the activation of inward K+ channels is the hyperpolarization of the PM through the activation of the PM H+-ATPase (Assmann et al., 1985; Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999; Roelfsema et al., 2001). Treatment of epidermal peels with the ATPase and phosphatase inhibitor sodium orthovanadate (Ueno et al., 2005; Kinoshita et al., 2011) resulted in reduced stomatal apertures at 35°C, suggesting a possible role for the PM H+-ATPase downstream of high-temperature perception (Fig. 3A), although the broad-spectrum activity of this compound required supporting data from reverse-genetics studies to substantiate this conclusion. There are 11 functional members of the PM H+-ATPase family in Arabidopsis (AHA1–AHA11), all of which are expressed in guard cells (Ueno et al., 2005). AHA1, AHA2, and AHA5 show the highest transcript accumulation in guard cell protoplasts (Ueno et al., 2005) and thus were selected for further analysis. Impairment in stomatal opening was detected in aha1-8 under both temperature regimes, suggesting that AHA1 mediates light-induced guard cell movement and that AHA1 function is required for complete stomatal opening under high temperatures (Fig. 3B). The aha1-6 allele displayed a similar phenotype to aha1-8 (Supplemental Fig. S4). By contrast, the two mutant alleles of aha2 (aha2-5 and aha2-4) displayed reduced stomatal apertures at 35°C but not at 22°C (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. S4). Together, these data suggest a specific role for AHA2 in high temperature-mediated stomatal opening. Wild-type stomatal opening phenotypes were observed in the aha5 mutant at both temperatures (Fig. 3B). The aha1aha2 double mutant is embryonic lethal and thus could not be investigated (Haruta et al., 2010). PROTON ATPASE TRANSLOCATION CONTROL1 (PATROL1) encodes a translocator protein that moves AHAs in and out of the PM and was found to be essential for stomatal opening in all conditions (Fig. 3C; Hashimoto-Sugimoto et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

High temperature-induced stomatal opening in isolated guard cells requires PM H+-ATPase activity. A, Treatment with the PM H+-ATPase inhibitor vanadate reduces high temperature-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis (Col-0). B, Mutants deficient in the PM H+-ATPases AHA1 and AHA2 display reduced stomatal opening at high temperature. C, PATROL1 is essential for stomatal opening. The PM H+-ATPase-interacting PPI1 and PPI2 proteins are not required for high temperature-mediated stomatal opening. Stomatal bioassays were performed on isolated epidermises from fully expanded rosette leaves, exposed to white light. Peels were incubated at 22°C for 2 h, followed by incubation at 22°C or 35°C for a further 2 h. For mutant analysis, Col-0 controls were carried out in parallel. Error bars indicate se. Asterisks indicate significant differences by Tukey’s posthoc test at P < 0.05 (n = 90, measured from three separate leaves, all from different plants). P values from a two-way ANOVA comparing stomatal apertures, with temperature and vanadate treatment (A) or genotype (B) as factors, are shown below graphs to highlight whether a significant interaction between each factor and response to temperature exists. n.s., Not significant.

PROTON PUMP INTERACTOR1 (PPI1) activates AHA1 (Morandini et al., 2002). We investigated high temperature-mediated stomatal opening in ppi1 and ppi2 mutants and detected only a mild stomatal opening defect for ppi1 at 22°C, consistent with a role for PPI1 in activating AHA1 in response to light (Fig. 3C; Morandini et al., 2002; Anzi et al., 2008).

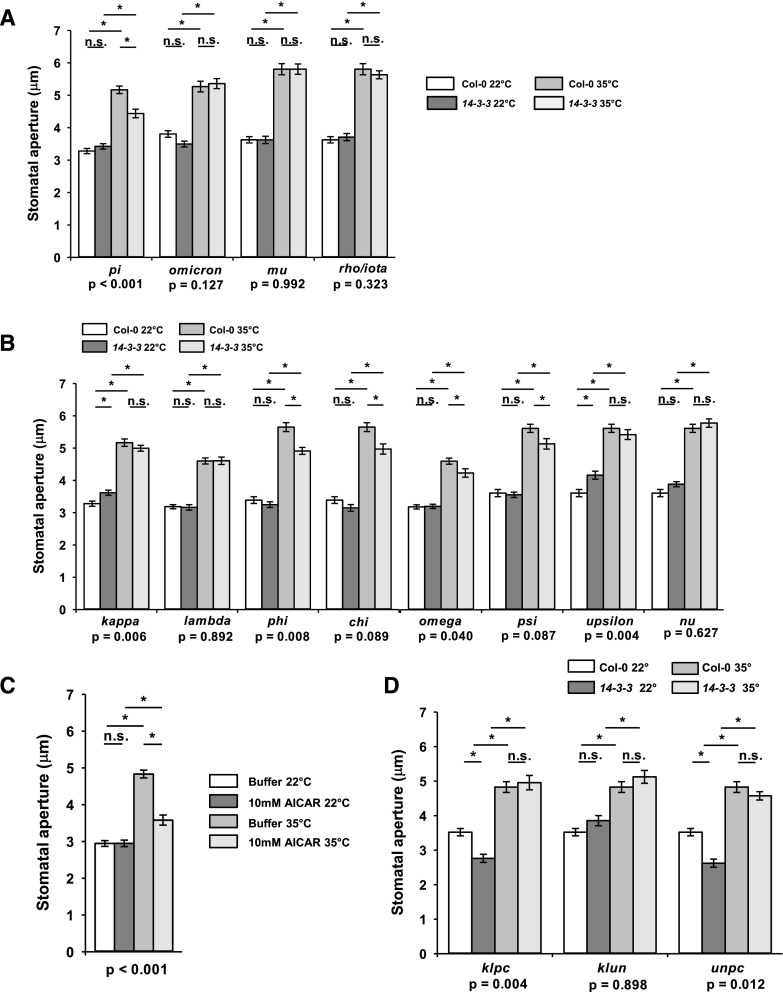

14-3-3 Proteins Mediate Stomatal Opening in Isolated Guard Cells in Response to High Temperature

One of the best-characterized mechanisms for the activation of the PM H+-ATPase involves interaction with a 14-3-3 protein. There are 13 members of the 14-3-3 protein family in Arabidopsis (Sehnke et al., 2002), all of which are expressed in guard cells according to the Arabidopsis eFP browser (Winter et al., 2007). We used 14-3-3 single mutants to systematically investigate whether these regulators participated in a high temperature-specific stomatal opening pathway. Five mutants (pi, phi, chi, omega, and psi) displayed significantly reduced stomatal apertures at 35°C, but not at 22°C, when compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4, A and B). These observations suggest that multiple members, particularly of the nonepsilon clade, share a role in high temperature-mediated guard cell movement. 14-3-3 epsilon was not included in this analysis because we were unable to generate a homozygous line. To further establish the importance of 14-3-3 proteins in high temperature-induced stomatal opening, we incubated wild-type epidermal peels with 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside (AICAR), which is a 5′-AMP mimetic successfully used in plants to inhibit the interaction of 14-3-3s with their client proteins (Toroser et al., 1998; Camoni et al., 2000; Paul et al., 2005; Lozano-Durán et al., 2014). This treatment blocked high temperature-mediated stomatal opening by ∼70% (Fig. 4C). Higher order mutants showed reduced stomatal apertures at 22°C in some combinations (klpc and unpc) but did not reveal any additive phenotypes at high temperature, suggesting the existence of complex interactions between 14-3-3 proteins (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Multiple members of the 14-3-3 family contribute to high temperature-induced stomatal opening. A, High temperature-induced stomatal opening in epsilon group mutants. B, High temperature-induced stomatal opening in nonepsilon group mutants. C, Disrupting the interaction of 14-3-3 proteins with their client proteins inhibits high temperature-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis (Col-0). D, 14-3-3 proteins are not functionally redundant, as quadruple 14-3-3 mutants do not display additive impairment in high temperature-induced stomatal opening (c, chi; k, kappa; l, lambda; n, nu; p, phi; u, upsilon). Stomatal bioassays were performed on isolated epidermises from fully expanded rosette leaves exposed to white light. Peels were incubated at 22°C for 2 h followed by incubation at 22°C or 35°C for a further 2 h. For mutant analysis, Col-0 controls were carried out in parallel. Error bars indicate se. Asterisks indicate significant differences by Tukey’s posthoc test at P < 0.05 (n = 90, measured from three separate leaves, all from different plants). P values from a two-way ANOVA comparing stomatal apertures, with temperature and genotype (A, B, and D) or AICAR treatment (C) as factors, are shown below graphs to highlight whether a significant interaction between each factor and response to temperature exists. n.s., Not significant.

Calcium Influx Does Not Drive High Temperature-Mediated Stomatal Opening in Isolated Guard Cells

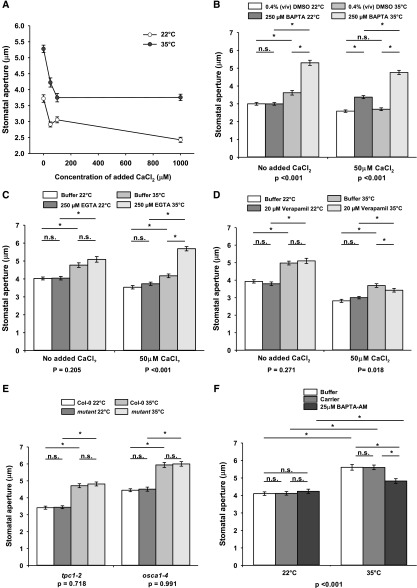

Calcium channels have an established role in heat sensing and thermotolerance in land plants (Saidi et al., 2009; Finka et al., 2012). Movement of calcium from the apoplast, however, promotes stomatal closure (De Silva et al., 1985). To establish whether high-temperature responses of guard cells involve Ca2+ signaling, epidermal peels were incubated with increasing calcium concentrations. Addition of 50 μm CaCl2 to the incubation buffer was sufficient to impair high temperature-induced stomatal opening, whereas treatment with 100 μm CaCl2 at 35°C resulted in the same absolute aperture values as untreated stomata at 22°C (Fig. 5A). Incubation of peels with chelating agents 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) and EGTA hindered the inhibition of stomatal opening by added extracellular calcium and allowed for much greater apertures to be achieved at 35°C than in the absence of BAPTA or EGTA (Fig. 5, B and C). Stomata subjected to added CaCl2 did not, however, open as expected in response to high temperature in the solvent control condition (Fig. 5B). We attribute this to the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 0.4% [v/v]), which can induce the formation of water pores on the PM (Notman et al., 2006), thus increasing dramatically the uptake of calcium. We further observed that calcium import leading to stomatal closure occurred through verapamil-insensitive channels at both temperatures (Fig. 5D). Collectively, the application of chelating agents and calcium channel blockers showed that influx of external calcium reduces stomatal aperture and therefore can be excluded as a high-temperature signal driving opening. In line with this conclusion, analyses of the inward-rectifying calcium channel mutants cngc6 and reduced hyperosmolality-induced [Ca2+]i increase1 (osca1-4) revealed no impairment of high temperature-mediated guard cell movement (Figs. 2A and 5E). Conversely, treatment with the membrane-permeable form of the calcium chelator BAPTA (BAPTA-AM; Young et al., 2006) inhibited high temperature-induced stomatal opening, suggesting a possible signaling role for intracellular calcium (Fig. 5F). The vacuolar membrane two-pore calcium channel mutant two-pore calcium channel1 (tpc1-2) retained wild-type stomatal apertures in response to high temperature, showing that TPC1 is not required for the response (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

High temperature-mediated stomatal opening in isolated guard cells is not mediated by import of extracellular calcium. A, Larger stomatal apertures are observed at 35°C in the presence and absence of calcium chloride. Extracellular calcium dose-response curves at 22°C and 35°C are shown. The experiment was performed in Col-0. The concentration of calcium with no added CaCl2 was estimated to be approximately 35 μm. B, Incubation with the calcium chelator BAPTA leads to increased stomatal apertures in response to high temperature. The experiment was performed in Col-0. C, Incubation with the divalent calcium chelator EGTA leads to increased stomatal apertures in response to high temperature. D, The effect of calcium on high temperature-induced stomatal opening is not mediated by verapamil-sensitive calcium channels. E, The calcium channels TPC1 and OSCA1 are not required for high temperature-induced stomatal opening. F, Treatment with the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM impairs stomatal opening in response to high temperature. Carrier, 0.1% (v/v) DMSO + 0.025% (v/v) Pluronic F-127. Stomatal bioassays were performed on isolated epidermises from fully expanded rosette leaves exposed to white light. Peels were incubated at 22°C for 2 h followed by incubation at 22°C or 35°C for a further 2 h. For mutant analysis, Col-0 controls were carried out in parallel. Error bars indicate se. Asterisks indicate significant differences by Tukey’s posthoc test at P < 0.05 (n = 90, measured from three separate leaves, all from different plants). P values from a two-way ANOVA comparing stomatal apertures, with temperature and pharmacological treatment (B–D and F) or genotype (E) treatment as factors, are shown below graphs to highlight whether a significant interaction between each factor and response to temperature exists. n.s., Not significant.

Phototropins Promote Evapotranspiration and Leaf Cooling at High Temperature

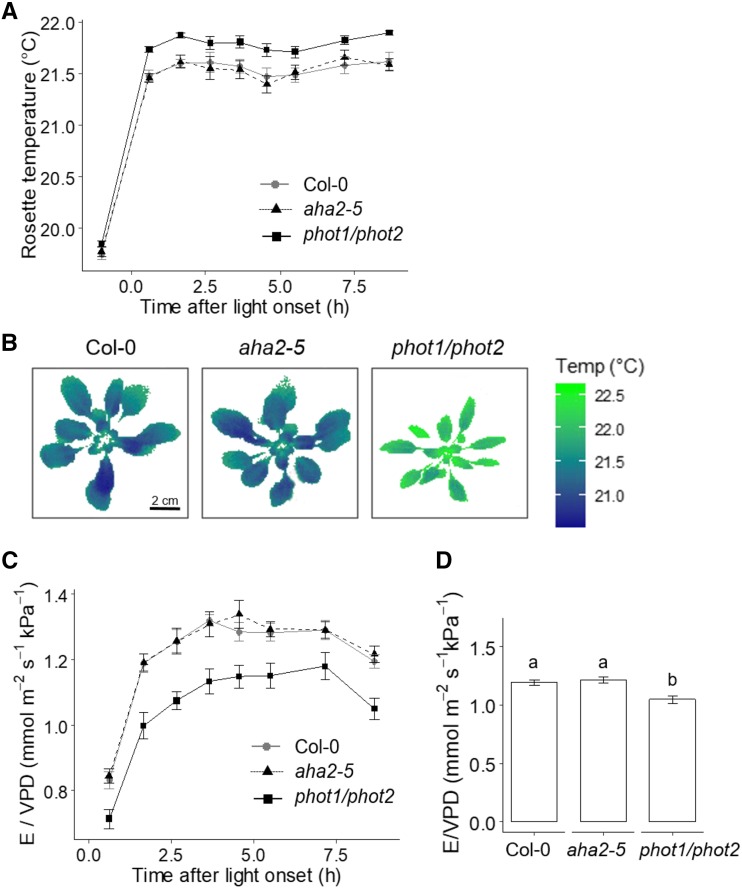

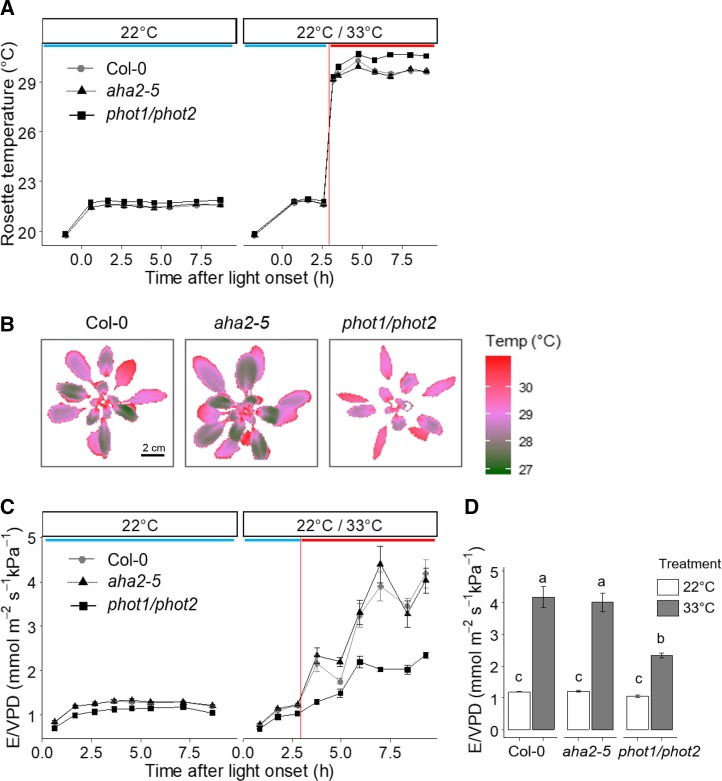

The involvement of phototropins and AHA2 in high temperature-mediated stomatal opening was further explored in planta, through gravimetric measurements of transpiration and thermal imaging. Wild-type, aha2-5, and phot1/phot2 rosettes were grown in a similar manner to plants used for epidermal strip bioassays for 4.5 weeks. Consistent with previous reports (Sakamoto and Briggs, 2002), phot1/phot2 mutants displayed severe leaf curling (Supplemental Fig. S5), which results in altered boundary layer conductance. We measured whole-plant transpiration, whole-plant temperature, and calculated rosette conductance as E/VPDleaf-air. On day 1 of the experiment, measurements were recorded at a constant temperature of 22°C. In contrast to aha2-5 mutants that resembled wild-type controls, phot1/phot2 plants displayed elevated rosette temperature (Fig. 6, A and B) and lower rosette conductance (Fig. 6, C and D). On day 2, the same protocol was repeated for 3 h postdawn to enable transpiration to stabilize. Half the plants were then transferred to identical light conditions at 33°C. This was the maximum temperature that could be used without generating a large change in air vapor pressure deficit (VPDair) between 22°C and high-temperature treatment. Transfer to 33°C resulted in a rapid increase in rosette temperature, which was maintained at approximately 29°C in wild-type and aha2-5 plants (Fig. 7, A and B). This elevation was accompanied by a large increase in rosette conductance (Fig. 7, C and D). In phot1/phot2 plants, rosette temperature reached higher values and the increase in rosette conductance was reduced when compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 7). No differences in stomatal density or index were recorded in aha5-2 or phot1/phot2 mutants (Supplemental Fig. S6), suggesting that phototropins contribute to high temperature-mediated stomatal opening in planta.

Figure 6.

Phototropins promote leaf cooling and rosette conductance at 22°C. A, Dynamics of rosette temperature in Col-0, aha2-5, and phot1/phot2 plants maintained at a photon irradiance of 150 µmol m−2 s−1 and a constant temperature of 22°C with a VPDair of 0.93 kPa. Error bars indicate se (n = 7). B, Thermal images of plants shown in A at 5 h following light onset. Bar = 2 cm for all images. C, Dynamics of rosette conductance (E/VPDleaf-air) in plants grown as in A. This was calculated from gravimetric whole-plant transpiration (E) measurements and VPDleaf-air. Error bars indicate se (n = 7). D, Average E/VPDleaf-air at 8.5 h after light onset. Error bars indicate se (n = 7). Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc test, and different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Phototropins promote leaf cooling and rosette conductance at high temperature. A, Dynamics of rosette temperature in Col-0, aha2-5, and phot1/phot2 plants maintained at a photon irradiance of 150 µmol m−2 s−1 and a constant temperature of 22°C with a VPDair of 0.93 kPa (left) and transferred at 3 h to 33°C with a VPDair = 1.2 kPa (right). Error bars indicate se (n = 7). B, Thermal images of plants shown in A at 5 h following light onset and 2 h after transfer to high temperature. Bar = 2 cm for all images. C, Dynamics of rosette conductance (E/VPDleaf-air) in plants grown as in A. This was calculated from gravimetric whole-plant transpiration (E) measurements and VPDleaf-air. Error bars indicate se (n = 7). D, Average E/VPDleaf-air 8.5 h after light onset. Error bars indicate se (n = 7). Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc test, and different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.01.

Stomatal Opening and Transcriptional Responses to High Temperature Are Not Mediated by a Linear Thermosensing Pathway in Guard Cells

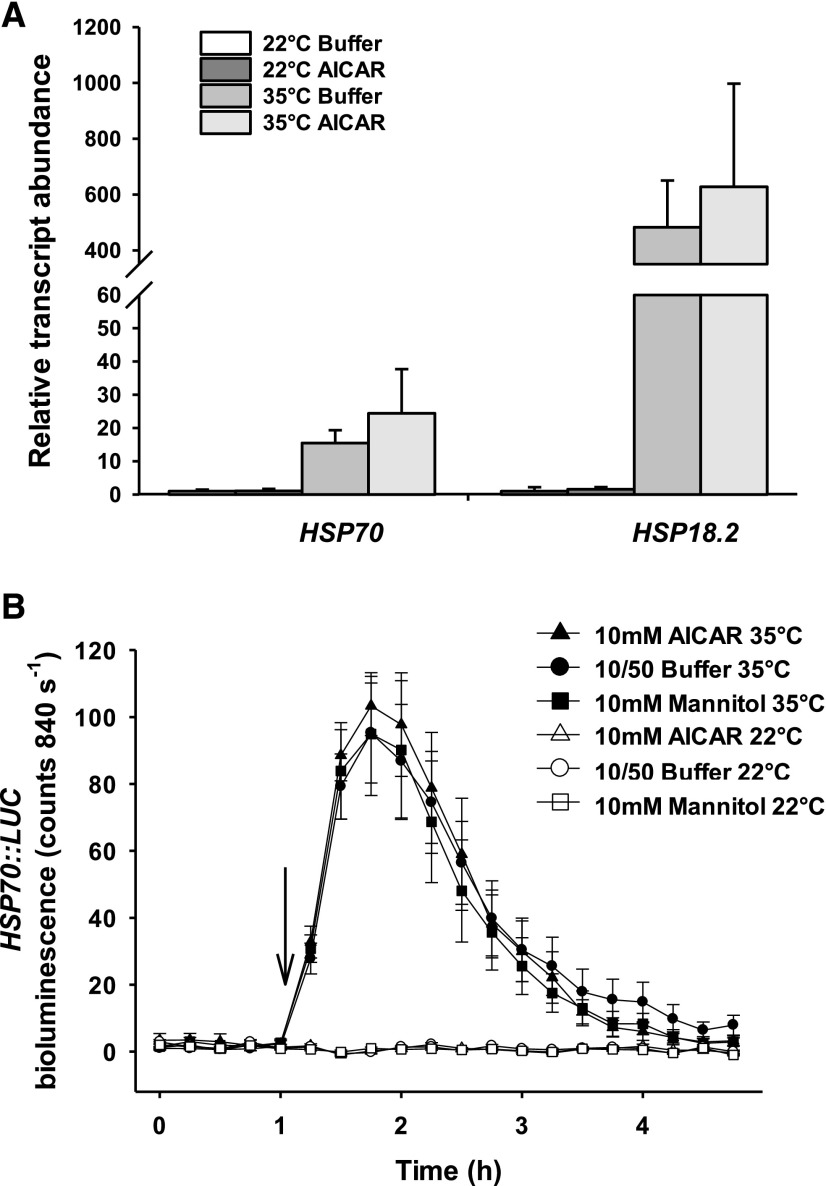

To explore signaling cross talk between different high-temperature responses, we analyzed the transcript abundance of high temperature-induced marker genes in isolated guard cells treated with AICAR. We hypothesized that if high temperature-mediated stomatal opening and transcription were controlled by a linear thermosensory pathway, then perturbation of this signaling cascade would impair both responses. The abundances of two high temperature-induced transcripts, namely HSP70 and HSP18.2, were measured in epidermal peels at 22°C and 35°C in the presence or absence of AICAR, a pharmacological inhibitor of the 14-3-3-PM H+-ATPase interaction and of high temperature-induced stomatal opening (Fig. 8A). Consistent with previous reports, the guard cell-specific transcripts GC1 and MYB60 (Yang et al., 2008) displayed higher relative transcript abundances in epidermal peels than in corresponding leaf tissue, demonstrating that the method used for RNA extraction resulted in guard cell-enriched samples (Supplemental Fig. S7A). Quantification of relative transcript abundance with two separate control genes showed that HSP70 and HSP18.2 transcripts accumulated in response to high temperature, even in the presence of AICAR (Fig. 8A; Supplemental Fig. S7B). Leaf disc transcript abundances displayed the same trends as the guard cell-enriched samples (Supplemental Fig. S7, C and D). HSP70 promoter activity was additionally recorded using transgenic lines expressing the HSP70::LUCIFERASE reporter (Kumar and Wigge, 2010). The HSP70 promoter had similar high-temperature responses in the presence or absence of AICAR, consistent with the transcript data (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Transcriptional induction of high temperature-regulated genes in guard cells is not inhibited by pharmacologically impairing 14-3-3-PM H+-ATPase interaction. A, Transcript abundance of HSP70 and HSP18.2 following AICAR and temperature treatments. Epidermal peels from fully expanded rosette leaves were incubated at 22°C for 2 h before incubation at 22°C or 35°C for 2 h. TIP41 was used as a control gene. Error bars indicate sd (n = 3). B, HSP70::LUC bioluminescence in detached leaf epidermises following AICAR and temperature treatments. The arrow denotes the temperature shift. An equimolar amount of mannitol was used as an additional osmotic control. Error bars indicate sd (n = 12).

DISCUSSION

When atmospheric relative humidity is not a restrictive factor, plants respond to high temperature by opening their stomata. This physiological response occurs under laboratory and field conditions in a number of species (Willmer and Mansfield, 1970; Rogers et al., 1979, 1980; Sadras et al., 2012; Mendes and Marenco, 2017; Urban et al., 2017). Despite the conservation of this response, little is known about how guard cells perceive and transduce temperature signals. Here, we show that high temperatures induce stomatal opening in Arabidopsis, barley, and C. communis (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1). We have further characterized the temperature range and kinetics of the Arabidopsis response (Fig. 1, B and C). Incubation of epidermal peels at 35°C led to a statistically significant increase in stomatal aperture without affecting tissue viability and was therefore chosen as the most appropriate treatment to study high-temperature signaling in isolated guard cells (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S2).

Mutants deficient in known thermosensory signaling components (cngc6, arp6, and ft) displayed wild-type apertures at 35°C, suggesting that these components are not required for high temperature-mediated stomatal opening (Fig. 2A). Intriguingly, and in contrast to studies using dark-to-(red + blue) light transfer, ft mutants maintained in white light displayed wild-type stomatal apertures at 22°C (Fig. 2C; Supplemental Fig. S3). It is therefore possible that FT functions predominantly to promote stomatal opening following a dark-to-light transfer. In this study, plants were grown in 10-h photoperiods. A striking reduction in FT transcript abundance has been recorded in guard cell protoplasts isolated from plants grown in short photoperiods compared with protoplasts extracted from plants grown in long photoperiods (Aoki et al., 2019). The similar stomatal apertures observed in the wild type and ft mutants under white light in this study might, therefore, be due to low FT levels in wild-type guard cells. Increased ambient temperature elevates auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seedlings via a process mediated by PIF4 (Franklin et al., 2011). Auxins have been shown to promote stomatal opening by limiting hydrogen peroxide production in guard cells (Dodd, 2003; Song et al., 2006). Mutants deficient in PIF4 displayed wild-type stomatal opening responses to elevated temperature, suggesting that auxin elevation is not a key regulatory mechanism underlying this response (Fig. 2A).

A thermosensory role for the phototropin blue light photoreceptors has been suggested following observations that the lifetime of photoactivated phototropin is temperature dependent in multiple species (Kodama et al., 2008; Nakasone et al., 2008; Fujii et al., 2017). Phototropins contain two light, oxygen, or voltage (LOV) domains at their photosensory N-terminal domain that bind FMN chromophores. In Marchantia polymorpha, the single MpPHOT photoreceptor has been shown to regulate cold-induced chloroplast movement, with low temperature prolonging the lifespan of the active LOV2 domain. Warmer temperatures cause the reversion of LOV2 to an inactive state, preventing the response (Fujii et al., 2017). As phototropins promote blue light-induced stomatal opening (Kinoshita et al., 2001), we hypothesized that they might function as thermosensors driving high temperature-mediated guard cell movement. Although a small, phototropin-independent response to high temperature was observed, complete stomatal opening required both phot1 and phot2 (Fig. 2D). This result was further supported by in planta data showing reduced evapotranspiration and leaf cooling in high temperature-treated phot1/phot2 mutants (Figs. 6 and 7). As warm temperatures have been shown to inactivate phototropin signaling in Marchantia spp. (Fujii et al., 2017), it is unclear how exposure to high temperature would lead to enhanced phototropin activity. The situation in Arabidopsis is, however, more complex, with the lifespan of LOV2 altered through interactions with other phototropin domains (Kasahara et al., 2002). Alternatively, high temperature may regulate signaling pathways downstream of phototropin rather than the activity of the photoreceptor itself (Fig. 9). The existence of an additional phototropin-independent pathway may explain why some high temperature-mediated stomatal opening can also be observed in the dark (Fig. 1B). It is possible that this response is mediated by RBOHD-mediated reactive oxygen species production (Devireddy et al., 2020).

Figure 9.

Possible sites of high-temperature signal integration during stomatal opening in white light. Stomatal opening in isolated guard cells following dark-to-blue light transfer involves phototropin-mediated phosphorylation of BLUS1, which then activates PM H+-ATPases. PATROL1 is required for AHA1 insertion into the PM. In prolonged white light, we observed a prominent role for phototropins and redundant interactions between H+-ATPases and 14-3-3 proteins in promoting stomatal opening. A partial role for BLUS1 was observed, suggesting the existence of a phototropin-mediated, BLUS1-independent pathway in these conditions. Complete stomatal opening in isolated guard cells at high temperature requires phototropins, PM H+-ATPase activity, and redundant activities of 14-3-3 proteins. A partial role for BLUS1 was identified. A requirement for phototropins in elevating stomatal conductance at high temperature was additionally observed in whole leaves. Some phototropin-independent increases in stomatal opening and rosette conductance at high temperature were also observed. High temperature may stimulate phototropin activity directly, phototropin signaling, or H+-ATPase activity. Increased H+-ATPase activity may result from enhanced 14-3-3 binding.

Blue light activates the PM H+-ATPase, causing PM hyperpolarization that in turn activates inward-rectifying K+ channels and stomatal opening (Shimazaki et al., 1986; Schroeder et al., 1987; Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999; Ueno et al., 2005). In fava bean, high temperature regulates the activity of inward- and outward-rectifying K+ channels, consistent with the induction of stomatal opening (Ilan et al., 1995). Here, we provide genetic evidence suggesting that AHA1 and AHA2 are required for a full stomatal opening response to high temperature in epidermal peels. An additional role for AHA1 in light-induced stomatal opening was also observed (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. S4). Consistent with our findings, AHA1 was recently reported to play a major role in blue light-induced stomatal opening, whereas aha2 and aha5 mutants showed no impairment of the response (Yamauchi et al., 2016). In addition to the C-terminal autoinhibitory domain, PM H+-ATPase pump activity is controlled by N-terminal domain variations, which may provide a mechanism for posttranslational regulation by different factors (Ekberg et al., 2010). Recruitment of AHA1, and possibly other AHA isoforms, to the PM in guard cells is mediated by the Munc13-like protein PATROL1 (Hashimoto-Sugimoto et al., 2013). We provide evidence that PATROL1 is essential for stomatal opening in response to high temperature, as is the case for fusicoccin, low CO2, and blue light (Fig. 3C; Hashimoto-Sugimoto et al., 2013).

To address how AHAs become activated in the high-temperature pathway, we investigated potential roles for AHA-regulating 14-3-3 proteins and the AHA-interacting proteins PPI. In response to blue light, 14-3-3 proteins, acting as dimers, bind to the autoinhibitory C-terminal region of the PM H+-ATPase and promote pumping (Jahn et al., 1997; Oecking et al., 1997; Wu et al., 1997; Emi et al., 2001). Genetic analyses of single and higher order 14-3-3 mutants revealed that they collectively contribute to high temperature-mediated stomatal opening with potentially antagonistic interactions between isoforms (Fig. 4). Isoform-specific redundancy and antagonism between 14-3-3 proteins has previously been reported in Arabidopsis root growth (van Kleeff et al., 2014). Of the 14 members present in Arabidopsis, 14-3-3 PHI and LAMBDA have been shown to be important for blue light-induced stomatal opening (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999; Ueno et al., 2005; Tseng et al., 2012). 14-3-3 isoforms of the nonepsilon group are more effective at activating the proton pump when compared with the epsilon group, a result that mirrors our data (Fig. 4; Pallucca et al., 2014). The C and N termini of each 14-3-3 isoform are highly specific, and members of the family demonstrate variation in binding affinity to the proton pump AHA2 (Rosenquist et al., 2000; Alsterfjord et al., 2004). Different family members may therefore activate the proton pump in response to environmental stimuli. Furthermore, 14-3-3 proteins can homodimerize and heterodimerize. Their subcellular localization depends on cell type and may be driven by client interactions, presenting multiple input points for environmental factors to exert their influence (Oecking et al., 1997; Wu et al., 1997; Paul et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2009).

Treatment with AICAR severely impaired high temperature-induced stomatal opening, highlighting the importance of 14-3-3 interactions in this response (Fig. 3A). It is interesting that AICAR treatment has also been shown to suppress pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered stomatal closure (Lozano-Durán et al., 2014), suggesting that the function of 14-3-3s is context dependent. 14-3-3 proteins have several clients in addition to the PM H+-ATPase, and it is possible that AICAR effects on high temperature-mediated stomatal opening may be related to other channels (Ichida et al., 1997; Sottocornola et al., 2006; Gobert et al., 2007; Latz et al., 2007). Further analysis is required to determine whether interaction of AHA2 with 14-3-3 proteins is enhanced at high temperature (Fig. 9). Despite clear evidence suggesting a role for AHA2 in high temperature-mediated stomatal opening in epidermal peels, aha2-5 mutants displayed wild-type levels of rosette conductance and leaf cooling at high temperature (Fig. 7). This discrepancy may result from the reduced sensitivity of in planta assays and redundancy between family members (e.g. AHA1) and/or the masking of AHA2 signaling in leaves resulting from signals from neighboring cells.

External calcium antagonizes high temperature-induced stomatal opening (Fig. 5A), which may result from the reversible inhibition of PM H+-ATPase activity (Kinoshita et al., 1995). Pharmacological evidence has suggested a role for intracellular calcium stores in blue light-induced stomatal opening (Shimazaki et al., 1992). In addition, low CO2 produces more [Ca2+]cyt transients compared with elevated CO2 and also increases stomatal apertures (Young et al., 2006). Both stomatal movements in response to CO2 and [Ca2+]cyt transients were inhibited by BAPTA-AM treatment (Young et al., 2006). In our study, BAPTA-AM treatment reduced high temperature-mediated stomatal opening, supporting a role for intracellular calcium (Fig. 5D), although the existence and source of [Ca2+]cyt transients at high temperature remain to be identified. Increased calcium concentration in the micromolar region promotes the association of 14-3-3 proteins with PM H+-ATPases (Manak and Ferl, 2007). Conversely, millimolar concentrations of calcium inhibit the dimerization of the 14-3-3 protein family member PSI and its interaction with client proteins (Abarca et al., 1999). It is therefore possible that local changes in calcium concentration may regulate the function of 14-3-3 proteins during high temperature-induced stomatal opening.

Although AICAR inhibited high temperature-induced guard cell movement, it did not affect the accumulation of heat-responsive transcripts (Fig. 8; Supplemental Fig. S7). This is in agreement with a study demonstrating that PECTIN METHYLESTERASE34 is required for acquired thermotolerance and stomatal movements but is not required for the induction of heat shock genes or the accumulation of heat shock proteins (Huang et al., 2017). CNGC6 facilitates the expression of heat shock proteins during acquired thermotolerance (Gao et al., 2012), but loss of this channel protein does not impair high temperature-induced stomatal opening (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, chromatin remodeling mediated by ARP6 is involved in high temperature-mediated transcription, yet arp6 mutant stomata opened fully in response to high temperature (Fig. 2A; Kumar and Wigge, 2010). These data suggest either the existence of discrete thermosensing mechanisms in different cellular compartments of guard cells or the divergence of a single thermosensory pathway upstream of 14-3-3-PM H+-ATPase interaction.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that Arabidopsis guard cells integrate light and temperature information to control stomatal aperture. The point at which these signals converge has yet to be elucidated but may involve direct stimulation of phototropin, amplification of phototropin signaling, and/or enhancement of AHA activity, possibly through enhanced 14-3-3 binding (Fig. 9). This study also establishes the Arabidopsis guard cell as a tractable system for studying intracellular thermosensing in angiosperms. Future work in this area is essential to facilitate crop production and biodiversity management in a warming climate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plant material is described in Supplemental Table S1. SALK and SAIL lines were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre and were tested for homozygosity with genomic DNA PCR. For previously uncharacterized lines, exact insertion points were determined by sequencing and transcript levels were quantified by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Seeds were sterilized with chlorine gas according to the protocol of Lindsey et al. (2017) and germinated on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium plates (0.22% [w/v] Murashige and Skoog salts, 1% [w/v] Suc, and 0.6% [w/v] agar, pH 5.8). Seedlings were transplanted to a 3:1 mixture of compost (all-purpose growing medium; Sinclair) and sand (horticultural silver sand; Melcourt) and were grown under a 10-h photoperiod in controlled-environment chambers (microclima; Snijders) irradiated by fluorescent tubes at 150 μmol m−2 s−1. Chambers were set to 22°C during the day, 20°C during the night, and 70% relative humidity.

Genotyping

To verify the genotype of T-DNA mutants, a 10-mm-diameter leaf disc was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 5-mm stainless-steel beads using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen). Ground samples were resuspended with 400 μL of extraction buffer (200 mm Tris Cl, pH 7.5, 250 mm NaCl, 25 mm EDTA, and 0.5% [w/v] SDS), centrifuged at 15,000g for 1 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. An equal volume of ice-cold isopropanol was added, and DNA was left to precipitate on ice for 30 min. Samples were centrifuged at 15,000g for 7 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of deionized water. One microliter of isolate was used as the template in a 25-μL PCR with DreamTaq polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel. In the case of previously uncharacterized insertions, PCR products using the T-DNA primer were isolated using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) and sequenced. Primer sequences used for genotyping are provided in Supplemental Tables 2A and 2B.

Epidermal Peel Bioassays

Plants at 4.5 to 6 weeks old were used for epidermal bioassays. Abaxial epidermal peels were isolated from fully expanded rosette leaves. An incision was performed near the leaf base, between the leaf edge and the midvein. Tissue was pulled from the incision site toward the leaf tip. Peels were trimmed with Vannas scissors to produce segments from the middle of the lamina blade. To prevent stomatal opening during sample preparation, peels were kept in 10/0 buffer (10 mm MES, pH 6.15). Unless specified, peels from three leaves per genotype, per condition, derived from different plants, were removed and incubated in 10/50 buffer (10 mm MES and 50 mm KCl, pH 6.15) at 22°C for 2 h, illuminated with white light (100 μmol m−2 s−1) or kept in the dark. These were then transferred to fresh 10/50 buffer prewarmed to the desired temperature and incubated for a further 2 h, unless different time points are specified, under the same light regime. For analyses of ft mutant responses to blue light, peels from dark-adapted plants were either maintained in the dark (±10 µm fusicoccin) or transferred at dawn to a mixture of blue light (λmax 470 nm, 10 μmol m−2 s−1) + red light (λmax 660 nm, 50 μmol m−2 s−1) provided by light-emitting diodes. Following treatments, peels were transferred to microscope slides and immediately covered with a cover slip before imaging. Unless otherwise specified, apertures for 10 stomata per peel were measured with an Olympus BX50 microscope attached to a Moticam 580 camera (Motic). No more than three neighboring stomata and no stomata near the edge of peels were measured. Each experiment was performed independently three times, and data presented are the pooled values. Chemical stock solutions used for pharmacological treatments during bioassays were made up with either 10/50 buffer (100 mm AICAR [Santa Cruz Biotechnology], 1 m CaCl2, and 20 mm verapamil hydrochloride [Santa Cruz Biotechnology]), water (250 mm EGTA [pH adjusted to 8 with KOH] and 10 mm sodium orthovanadate [pH adjusted to 10 with HCl]), ethanol (10 µm fusicoccin [Santa Cruz Biotechnology]), or DMSO (62.5 mm BAPTA [Santa Cruz Biotechnology] and 25 mm BAPTA-AM [Santa Cruz Biotechnology]). Chemicals made up with water, ethanol, or DMSO were diluted with 10/50 buffer to the final working concentrations. Chemical treatments were added to the fresh 10/50 buffer used during the second incubation with the exception of BAPTA-AM, which included an additional loading step as described previously (Young et al., 2006).

Viability Staining

To evaluate guard cell viability, epidermal peels were stained with fluorescein diacetate immediately after temperature incubations. Peels were transferred to fresh 10/50 buffer containing 0.001 (w/v) fluorescein diacetate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1% [w/v] stock solution in acetone) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Peels were briefly washed with 10/50 buffer to remove excess dye, and fluorescence was imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope equipped with an XBO 75 fluorescent lamp and a GFP filter. Volocity software (Perkin-Elmer) was used to analyze the images.

Gravimetric Analysis of Transpiration and Thermal Imaging

In all experiments, plants were maintained at 150 µmol m−2 s−1. From germination to the end of the experiment, each pot was weighed daily and watered at a target weight to maintain soil water content at 0.65 g water g−1 dry soil, previously determined as a well-watered level nonlimiting for growth and corresponding to 80% of field capacity (Rymaszewski et al., 2018). Gravimetric transpiration measurements were undertaken 4.5 weeks after sowing, during 2 consecutive days on seven plants per genotype. Pots were sealed with a double layer of Parafilm to prevent water evaporation from the soil. On day 1, all plants were maintained at 22°C and relative humidity at 65%, resulting in a constant VPDair of approximately 0.93 kPa. Each pot was weighed with 10−3 g accuracy (Precisa balances XB; Precisa) every hour, starting 1.5 h before light onset. Weight losses between measurements were used to calculate transpiration rate on a leaf area basis (E), using the total rosette area on the same day for each plant. Each weight measurement was coupled to an individual thermal-infrared image of each plant, taken from above (FLIR E60 Thermal Imaging Camera; FLIR Systems). Reflected temperature was measured with a multidirectional mirror and processed using Thermimage R (Tattersall, 2019). Plant pixels were separated from the image background using temperature thresholds, and the plant temperature was calculated as the average temperature of plant pixels. On day 2, the same plants were measured following the same protocol (hourly weighing and thermal imaging) in the same conditions, starting 1.5 h before light onset. Three hours after light onset, when transpiration was stabilized, plants were transferred to a second cabinet adjusted to 33°C and 75% relative humidity, yielding a VPDair of approximately 1.2 kPa (as close as possible to the VPDair in the control cabinet). Hourly weighing and thermal imaging were then performed for a further 6 h. Measurements of air temperature, air relative humidity, and leaf temperature were used to calculate the leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficit (VPDleaf-air). E/VPDleaf-air was then calculated for each plant at each time point as an estimate of total rosette conductance according to the diffusion equation of water vapor in the air.

Determination of Rosette Area

Daily estimates of projected rosette area were calculated for each plant using images taken from above every 2 d and analyzed with Ilastik software, version 1.21.7 (Sommer et al., 2011). Total pixels corresponding to plants were extracted from background using a random forest classification method based on color and texture and later converted to millimeters. Total rosette area was measured 4.5 weeks after sowing by dissecting the plants and was compared with projected rosette area on the same day to determine genotype-dependent coefficients for the ratio of total versus projected rosette area.

Stomatal Density

Plants were grown in the control conditions described above for transpiration analyses. Five weeks after sowing, impressions of the abaxial surface of two mature rosette leaves from seven plants per genotype were made with dental resin (President Jet Light Body; Coltène/Whaledent). Clear nail varnish was applied to the set impression after removal from the leaf. The varnish impressions were viewed on an Olympus BX51 inverted microscope, fitted with an Olympus DP70 camera, and analyzed with ImageJ software version 1.43U (National Institutes of Health). Stomata were counted within a 0.3-mm2 area near the middle of the leaf. Where possible, two measurements were recorded per leaf. Stomatal density was calculated as the number of stomata per mm2. Stomatal index (S.I.) was calculated as follows: S.I. = [(number of stomata)/(number of other epidermal cells + number of stomata)] × 100. A minimum of five leaves were analyzed per genotype.

Bioluminescence Imaging

Epidermal peels were incubated in 10/50 buffer containing 5 mm luciferin (d-luciferin potassium salt; Melford) at 22°C for 2 h in the dark. A black 96-well cell culture plate was loaded with 350 μL of 10/50 buffer and 5 mm luciferin per well, and the chemical treatments were randomly distributed along the plate. Peels were transferred so that each peel occupied one well, and bioluminescence was measured with a Photek HRPCS intensified CCD camera system (Photek) equipped with Peltier temperature control. Peels were imaged for 1 h at 22°C and then for another 4 h and 45 min either at 22°C or 35°C. A clear plastic cover was used to minimize evaporation. Images were captured every 15 min, with 14-min integration time. Acquisition and image analysis were performed with the IMAGE32 software (Photek).

RNA Extraction

For characterization of mutant lines, 30 10-d-old seedlings (∼100 mg of tissue) were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 3-mm tungsten carbide beads using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen). RNA from ground samples was then extracted using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were treated with DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) to remove residual DNA. For analyses of HSP transcripts, RNA was extracted from isolated epidermises (to enrich samples in guard cell transcripts) and leaf discs, both derived from fully expanded rosette leaves. Each epidermis sample consisted of 20 abaxial epidermal peels, with each peel approximately corresponding to half the surface area of the leaf blade. Peels were kept in 10/0 buffer during sample preparation and were then processed similarly to a stomatal bioassay. Following treatment, peels were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Leaf controls consisted of four 5-mm-diameter leaf discs and were treated as described above. Frozen samples were homogenized at 4°C with 400-μL glass beads (glass beads, acid washed, 425–600 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) and 350 μL of buffer RULT (Qiagen) containing 1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen). Homogenization treatment comprised five cycles of 1 min of homogenization at 30 Hz followed by 1 min of rest on ice. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy UCP Micro Kit (Qiagen).

Transcript Abundance

Isolated RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and reverse transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed with 2× Brilliant III SYBR Green QPCR (Agilent Technologies). Data were collected and analyzed using the MxPro software (Agilent Technologies). Three biological and three technical repeats were performed for each sample, and relative transcript abundance was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Biological repeats refer to an independent experiment, using different tissue samples. Primer sequences for RT-qPCR experiments are provided in Supplemental Table S3.

Statistical Analyses

SigmaPlot v13 (Systat Software), IBM-SPSS-Statistic23 (IBM), and R (R Core Team, 2013) were used to analyze quantitative data.

Accession Numbers

Accession numbers are as follows: 14-3-3 CHI (At4g09000), 14-3-3 KAPPA (At5g65430), 14-3-3 LAMBDA (At5g10450), 14-3-3 MU (At2g42590), 14-3-3 NU (At3g02520), 14-3-3 OMEGA (At1g78300), 14-3-3 OMICRON (At1g34760), 14-3-3 PHI (At1g35160), 14-3-3 PI (At1g78220), 14-3-3 PSI (At5g38480), 14-3-3 RHO/IOTA (At1g26480), 14-3-3 UPSILON (At5g16050), AHA1 (At2g18960), AHA2 (At4g30190), AHA5 (At2g24520), ARP6 (AT3G33520), BLUS1 (At4g14480), CNGC6 (At2g23980), FT (At1g65480), GC1 (At1g22690), HSP18.2 (AT5G59720), HSP70 (At3g12580), MYB60 (At1g08810), OSCA1 (At4g04340), PATROL1 (At5g06970), PHOT1 (AT3G45780), PHOT2 (At5g58140), PIF4 (At2g43010), PP2AA3 (At1g13320), PPI1 (At4g27500), PPI2 (At3g15340), and TPC1 (At4g03560).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Barley and C. communis guard cells sense temperature in the light and the dark.

Supplemental Figure S2. Stomata remain viable after treatment at 35°C.

Supplemental Figure S3. ft mutants display impaired stomatal opening responses when transferred from dark to light.

Supplemental Figure S4. High temperature-induced stomatal opening in isolated guard cells requires PM H+-ATPase activity (additional mutant alleles for AHA1 and AHA2).

Supplemental Figure S5. Morphology of Col-0, aha2-5, and phot1/phot2 mutants under experimental treatments.

Supplemental Figure S6. aha-5 and phot1/phot2 mutants do not display altered stomatal density or index.

Supplemental Figure S7. Transcriptional induction of high temperature-regulated genes is not inhibited by pharmacologically impairing 14-3-3-PM H+-ATPase interaction.

Supplemental Table S1. Mutant lines.

Supplemental Table S2A. Primers used for genotyping: T-DNA spanning.

Supplemental Table S2B. Primers used for genotyping: T-DNA specific.

Supplemental Table S3. Primers used for RT-qPCR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Phil Wigge (University of Potsdam), Christian Fankhauser (University of Lausanne), and Dr. Bert de Boer (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) for the donation of seed. We also thank Dr. Llorenç Cabrera-Bosquet (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique Montpellier) for help with thermal image analysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Leverhulme Trust (grant no. RPG-2014-178), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant nos. BB/L01369X/1 and BB/N001168/1), and a Marie Curie Fellowship from the European Research Council (MSCA-IF H2020) to A.C.-L.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Abarca D, Madueño F, Martínez-Zapater JM, Salinas J (1999) Dimerization of Arabidopsis 14-3-3 proteins: Structural requirements within the N-terminal domain and effect of calcium. FEBS Lett 462: 377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsterfjord M, Sehnke PC, Arkell A, Larsson H, Svennelid F, Rosenquist M, Ferl RJ, Sommarin M, Larsson C (2004) Plasma membrane H+-ATPase and 14-3-3 isoforms of Arabidopsis leaves: Evidence for isoform specificity in the 14-3-3/H+-ATPase interaction. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 1202–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzi C, Pelucchi P, Vazzola V, Murgia I, Gomarasca S, Piccoli MB, Morandini P (2008) The proton pump interactor (Ppi) gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana: Expression pattern of Ppi1 and characterisation of knockout mutants for Ppi1 and 2. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 10: 237–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki S, Toh S, Nakamichi N, Hayashi Y, Wang Y, Suzuki T, Tsuji H, Kinoshita T (2019) Regulation of stomatal opening and histone modification by photoperiod in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep 9: 10054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM, Simoncini L, Schroeder JI (1985) Blue light activates electrogenic ion pumping in guard cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 318: 285–287 [Google Scholar]

- Bridge LJ, Franklin KA, Homer ME (2013) Impact of plant shoot architecture on leaf cooling: A coupled heat and mass transfer model. J R Soc Interface 10: 20130326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoni L, Iori V, Marra M, Aducci P (2000) Phosphorylation-dependent interaction between plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase and 14-3-3 proteins. J Biol Chem 275: 9919–9923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang IF, Curran A, Woolsey R, Quilici D, Cushman JC, Mittler R, Harmon A, Harper JF (2009) Proteomic profiling of tandem affinity purified 14-3-3 protein complexes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proteomics 9: 2967–2985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AJ, McLachlan DH, Hetherington AM, Franklin KA (2012) High temperature exposure increases plant cooling capacity. Curr Biol 22: R396–R397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva DLR, Hetherington AM, Mansfield TA (1985) Synergism between calcium ions and abscisic acid in preventing stomatal opening. New Phytol 100: 473–482 [Google Scholar]

- Devireddy AR, Arbogast J, Mittler R (2020) Coordinated and rapid whole-plant systemic stomatal responses. New Phytol 225: 21–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd IC. (2003) Hormonal interactions and stomatal responses. J Plant Growth Regul 22: 32–46 [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg K, Palmgren MG, Veierskov B, Buch-Pedersen MJ (2010) A novel mechanism of P-type ATPase autoinhibition involving both termini of the protein. J Biol Chem 285: 7344–7350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emi T, Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2001) Specific binding of vf14-3-3a isoform to the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in response to blue light and fusicoccin in guard cells of broad bean. Plant Physiol 125: 1115–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finka A, Cuendet AFH, Maathuis FJM, Saidi Y, Goloubinoff P (2012) Plasma membrane cyclic nucleotide gated calcium channels control land plant thermal sensing and acquired thermotolerance. Plant Cell 24: 3333–3348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA, Lee SH, Patel D, Kumar SV, Spartz AK, Gu C, Ye S, Yu P, Breen G, Cohen JD, et al. (2011) Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 (PIF4) regulates auxin biosynthesis at high temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 20231–20235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Tanaka H, Konno N, Ogasawara Y, Hamashima N, Tamura S, Hasegawa S, Hayasaki Y, Okajima K, Kodama Y (2017) Phototropin perceives temperature based on the lifetime of its photoactivated state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: 9206–9211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Han X, Wu J, Zheng S, Shang Z, Sun D, Zhou R, Li B (2012) A heat-activated calcium-permeable channel—Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel 6—is involved in heat shock responses. Plant J 70: 1056–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert A, Isayenkov S, Voelker C, Czempinski K, Maathuis FJM (2007) The two-pore channel TPK1 gene encodes the vacuolar K+ conductance and plays a role in K+ homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 10726–10731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M, Burch HL, Nelson RB, Barrett-Wilt G, Kline KG, Mohsin SB, Young JC, Otegui MS, Sussman MR (2010) Molecular characterization of mutant Arabidopsis plants with reduced plasma membrane proton pump activity. J Biol Chem 285: 17918–17929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto-Sugimoto M, Higaki T, Yaeno T, Nagami A, Irie M, Fujimi M, Miyamoto M, Akita K, Negi J, Shirasu K, et al. (2013) A Munc13-like protein in Arabidopsis mediates H+-ATPase translocation that is essential for stomatal responses. Nat Commun 4: 2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington AM, Woodward FI (2003) The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 424: 901–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YC, Wu HC, Wang YD, Liu CH, Lin CC, Luo DL, Jinn TL (2017) PECTIN METHYLESTERASE34 contributes to heat tolerance through its role in promoting stomatal movement. Plant Physiol 174: 748–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida AM, Pei ZM, Baizabal-Aguirre VM, Turner KJ, Schroeder JI (1997) Expression of a Cs+-resistant guard cell K+ channel confers Cs+-resistant, light-induced stomatal opening in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 9: 1843–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilan N, Moran N, Schwartz A (1995) The role of potassium channels in the temperature control of stomatal aperture. Plant Physiol 108: 1161–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn T, Fuglsang AT, Olsson A, Brüntrup IM, Collinge DB, Volkmann D, Sommarin M, Palmgren MG, Larsson C (1997) The 14-3-3 protein interacts directly with the C-terminal region of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Cell 9: 1805–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JH, Domijan M, Klose C, Biswas S, Ezer D, Gao M, Khattak AK, Box MS, Charoensawan V, Cortijo S, et al. (2016) Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis. Science 354: 886–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M, Swartz TE, Olney MA, Onodera A, Mochizuki N, Fukuzawa H, Asamizu E, Tabata S, Kanegae H, Takano M, et al. (2002) Photochemical properties of the flavin mononucleotide-binding domains of the phototropins from Arabidopsis, rice, and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 129: 762–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Doi M, Suetsugu N, Kagawa T, Wada M, Shimazaki K (2001) Phot1 and phot2 mediate blue light regulation of stomatal opening. Nature 414: 656–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Nishimura M, Shimazaki K (1995) Cytosolic concentration of Ca2+ regulates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cells of fava bean. Plant Cell 7: 1333–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Ono N, Hayashi Y, Morimoto S, Nakamura S, Soda M, Kato Y, Ohnishi M, Nakano T, Inoue S, et al. (2011) FLOWERING LOCUS T regulates stomatal opening. Curr Biol 21: 1232–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (1999) Blue light activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation of the C-terminus in stomatal guard cells. EMBO J 18: 5548–5558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama Y, Tsuboi H, Kagawa T, Wada M (2008) Low temperature-induced chloroplast relocation mediated by a blue light receptor, phototropin 2, in fern gametophytes. J Plant Res 121: 441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koini MA, Alvey L, Allen T, Tilley CA, Harberd NP, Whitelam GC, Franklin KA (2009) High temperature-mediated adaptations in plant architecture require the bHLH transcription factor PIF4. Curr Biol 19: 408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SV, Lucyshyn D, Jaeger KE, Alós E, Alvey E, Harberd NP, Wigge PA (2012) Transcription factor PIF4 controls the thermosensory activation of flowering. Nature 484: 242–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SV, Wigge PA (2010) H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes mediate the thermosensory response in Arabidopsis. Cell 140: 136–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JM, Murata Y, Baizabal-Aguirre VM, Merrill J, Wang M, Kemper A, Hawke SD, Tallman G, Schroeder JI (2001) Dominant negative guard cell K+ channel mutants reduce inward-rectifying K+ currents and light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 127: 473–485 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz A, Becker D, Hekman M, Müller T, Beyhl D, Marten I, Eing C, Fischer A, Dunkel M, Bertl A, et al. (2007) TPK1, a Ca2+-regulated Arabidopsis vacuole two-pore K+ channel is activated by 14-3-3 proteins. Plant J 52: 449–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legris M, Klose C, Burgie ES, Rojas CCR, Neme M, Hiltbrunner A, Wigge PA, Schäfer E, Vierstra RD, Casal JJ (2016) Phytochrome B integrates light and temperature signals in Arabidopsis. Science 354: 897–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey BE III, Rivero L, Calhoun CS, Grotewold E, Brkljacic J (2017) Standardized method for high-throughput sterilization of Arabidopsis seeds. J Vis Exp 128: 56587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Durán R, Bourdais G, He SY, Robatzek S (2014) The bacterial effector HopM1 suppresses PAMP-triggered oxidative burst and stomatal immunity. New Phytol 202: 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manak MS, Ferl RJ (2007) Divalent cation effects on interactions between multiple Arabidopsis 14-3-3 isoforms and phosphopeptide targets. Biochemistry 46: 1055–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes KR, Marenco RA (2017) Stomatal opening in response to the simultaneous increase in vapor pressure deficit and temperature over a 24-h period under constant light in a tropical rainforest of the central Amazon. Theor Exp Plant Physiol 29: 187–194 [Google Scholar]

- Morandini P, Valera M, Albumi C, Bonza MC, Giacometti S, Ravera G, Murgia I, Soave C, De Michelis MI (2002) A novel interaction partner for the C-terminus of Arabidopsis thaliana plasma membrane H+-ATPase (AHA1 isoform): Site and mechanism of action on H+-ATPase activity differ from those of 14-3-3 proteins. Plant J 31: 487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone Y, Eitoku T, Zikihara K, Matsuoka D, Tokutomi S, Terazima M (2008) Stability of dimer and domain-domain interaction of Arabidopsis phototropin 1 LOV2. J Mol Biol 383: 904–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notman R, Noro M, O’Malley B, Anwar J (2006) Molecular basis for dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) action on lipid membranes. J Am Chem Soc 128: 13982–13983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oecking C, Piotrowski M, Hagemeier J, Hagemann K (1997) Topology and target interaction of the fusicoccin-binding 14-3-3 homologs of Commelina communis. Plant J 12: 441–453 [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw WH, Lowry OH (1977) Organic acid and potassium accumulation in guard cells during stomatal opening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74: 4434–4438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallucca R, Visconti S, Camoni L, Cesareni G, Melino S, Panni S, Torreri P, Aducci P (2014) Specificity of ε and non-ε isoforms of Arabidopsis 14-3-3 proteins towards the H+-ATPase and other targets. PLoS ONE 9: e90764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AL, Sehnke PC, Ferl RJ (2005) Isoform-specific subcellular localization among 14-3-3 proteins in Arabidopsis seems to be driven by client interactions. Mol Biol Cell 16: 1735–1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins SE, Alexander LV, Nairn JR (2012) Increasing frequency, intensity and duration of observed global heatwaves and warm spells. Geophys Res Lett 39: 1–5 [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema MRG, Steinmeyer R, Staal M, Hedrich R (2001) Single guard cell recordings in intact plants: Light-induced hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane. Plant J 26: 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C, Sharpe PJH, Powell RD (1980) Dark opening of stomates of Vicia faba in CO2-free air: Effect of temperature on stomatal aperture and potassium accumulation. Plant Physiol 65: 1036–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CA, Powell RD, Sharpe PJ (1979) Relationship of temperature to stomatal aperture and potassium accumulation in guard cells of Vicia faba. Plant Physiol 63: 388–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist M, Sehnke P, Ferl RJ, Sommarin M, Larsson C (2000) Evolution of the 14-3-3 protein family: Does the large number of isoforms in multicellular organisms reflect functional specificity? J Mol Evol 51: 446–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rymaszewski W, Dauzat M, Bédiée A, Rolland G, Luchaire N, Granier C, Hennig J, Vile D (2018) Measurement of Arabidopsis thaliana plant traits using the PHENOPSIS phenotyping platform. Bio Protoc 8: e2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadras VO, Montoro A, Moran MA, Aphalo PJ (2012) Elevated temperature altered the reaction norms of stomatal conductance in field-grown grapevine. Agric Meteorol 165: 35–42 [Google Scholar]

- Saidi Y, Finka A, Muriset M, Bromberg Z, Weiss YG, Maathuis FJM, Goloubinoff P (2009) The heat shock response in moss plants is regulated by specific calcium-permeable channels in the plasma membrane. Plant Cell 21: 2829–2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K, Briggs WR (2002) Cellular and subcellular localization of phototropin 1. Plant Cell 14: 1723–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Raschke K, Neher E (1987) Voltage dependence of K channels in guard-cell protoplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 4108–4112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehnke PC, DeLille JM, Ferl RJ (2002) Consummating signal transduction: the role of 14-3-3 proteins in the completion of signal-induced transitions in protein activity. Plant Cell 14(Suppl): S339–S354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Iino M, Zeiger E (1986) Blue light-dependent proton extrusion by guard-cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 319: 324–326 [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Kinoshita T, Nishimura M (1992) Involvement of calmodulin and calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase in blue light-dependent H pumping by guard cell protoplasts from Vicia faba L. Plant Physiol 99: 1416–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Strähle C, Köthe U, Hamprecht FA (2011) Ilastik: Interactive learning and segmentation toolkit. Proceedings of the Eighth IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Piscataway, NJ, pp. 230–233 [Google Scholar]

- Song XG, She XP, He JM, Huang C, Song TS (2006) Cytokinin- and auxin-induced stomatal opening involves a decrease in levels of hydrogen peroxide in guard cells of Vicia faba. Funct Plant Biol 33: 573–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottocornola B, Visconti S, Orsi S, Gazzarrini S, Giacometti S, Olivari C, Camoni L, Aducci P, Marra M, Abenavoli A, et al. (2006) The potassium channel KAT1 is activated by plant and animal 14-3-3 proteins. J Biol Chem 281: 35735–35741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya A, Sugiyama N, Fujimoto H, Tsutsumi T, Yamauchi S, Hiyama A, Tada Y, Christie JM, Shimazaki K (2013) Phosphorylation of BLUS1 kinase by phototropins is a primary step in stomatal opening. Nat Commun 4: 2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tattersall GJ. (2019) Thermimage: Thermal image analysis. R package version 3.2.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Thermimage (Accessed May 25, 2019)

- Toroser D, Athwal GS, Huber SC (1998) Site-specific regulatory interaction between spinach leaf sucrose-phosphate synthase and 14-3-3 proteins. FEBS Lett 435: 110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng TS, Whippo C, Hangarter RP, Briggs WR (2012) The role of a 14-3-3 protein in stomatal opening mediated by PHOT2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 1114–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K, Kinoshita T, Inoue S, Emi T, Shimazaki K (2005) Biochemical characterization of plasma membrane H+-ATPase activation in guard cell protoplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana in response to blue light. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 955–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J, Ingwers MW, McGuire MA, Teskey RO (2017) Increase in leaf temperature opens stomata and decouples net photosynthesis from stomatal conductance in Pinus taeda and Populus deltoides × nigra. J Exp Bot 68: 1757–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kleeff PJ, Jaspert N, Li KW, Rauch S, Oecking C, de Boer AH (2014) Higher order Arabidopsis 14-3-3 mutants show 14-3-3 involvement in primary root growth both under control and abiotic stress conditions. J Exp Bot 65: 5877–5888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FF, Lian HL, Kang CY, Yang HQ (2010) Phytochrome B is involved in mediating red light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant 3: 246–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmer CM, Mansfield TA (1970) Effects of some metabolic inhibitors and temperature on ion-stimulated stomatal opening in detached epidermis. New Phytol 69: 983–992 [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Vinegar B, Nahal H, Ammar R, Wilson GV, Provart NJ (2007) An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS ONE 2: e718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Lu G, Sehnke P, Ferl RJ (1997) The heterologous interactions among plant 14-3-3 proteins and identification of regions that are important for dimerization. Arch Biochem Biophys 339: 2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi S, Takemiya A, Sakamoto T, Kurata T, Tsutsumi T, Kinoshita T, Shimazaki K (2016) The plasma membrane H+-ATPase AHA1 plays a major role in stomatal opening in response to blue light. Plant Physiol 171: 2731–2743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Costa A, Leonhardt N, Siegel RS, Schroeder JI (2008) Isolation of a strong Arabidopsis guard cell promoter and its potential as a research tool. Plant Methods 4: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JJ, Mehta S, Israelsson M, Godoski J, Grill E, Schroeder JI (2006) CO2 signaling in guard cells: Calcium sensitivity response modulation, a Ca2+-independent phase, and CO2 insensitivity of the gca2 mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7506–7511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]