Abstract

Introduction

The orphan nuclear receptor 4A2 (NR4A2) has been extensively characterized in subcellular regions of the brain and is necessary for the function of dopaminergic neurons. The NR4A2 ligand, 1,1-bis (31-indoly1)-1-(p-chlorophenyl)methane (DIM-C-pPhCl) inhibits markers of neuroinflammation and degeneration in mouse models and in this study we investigated expression and function of NR4A2 in glioblastoma (GBM).

Methods

Established and patient-derived cell lines were used as models and the expression and functions of NR4A2 were determined by western blots and NR4A2 gene silencing by antisense oligonucleotides respectively. Effects of NR4A2 knockdown and DIM-C-pPhCl on cell growth, induction of apoptosis (Annexin V Staining) and migration/invasion (Boyden chamber and spheroid invasion assay) and transactivation of NR4A2-regulated reporter genes were determined. Tumor growth was investigated in athymic nude mice bearing U87-MG cells as xenografts.

Results

NR4A2 knockdown and DIM-C-pPhCl inhibited GBM cell and tumor growth, induced apoptosis and inhibited migration and invasion of GBM cells. DIM-C-pPhCl and related analogs also inhibited NR4A2-regulated transactivation (luciferase activity) confirming that DIM-C-pPhCl acts as an NR4A2 antagonist and blocks NR4A2-dependent pro-oncogenic responses in GBM.

Conclusion

We demonstrate for the first time that NR4A2 is pro-oncogenic in GBM and thus a potential druggable target for patients with tumors expressing this receptor. Moreover, our bis-indole-derived NR4A2 antagonists represent a novel class of anti-cancer agents with potential future clinical applications for treating GBM.

Keywords: NR4A2, glioblastoma, NR4A2 antagonist, growth inhibition

Introduction

The orphan nuclear receptor 4A (NR4A) family contains three receptors, NR4A1 (Nur77), NR4A2 (Nurr1), and NR4A3 (Nor1), which exhibit significant structural similarities in their ligand binding domains (LBDs) and DNA BDs, whereas their N-terminal (A/B) domains containing activation function 1 (AF1) are highly divergent [1–4]. The initial discovery of NR4A receptors was linked to their rapid induction by multiple stimuli in various tissues/cells and organs. These responses play important roles in coping with both exogenous and endogenous stressors and the tissue-specific expression and induction of NR4A receptors that contributes to their specificity [5,6]. NR4A receptors play a role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and in pathophysiology, including cancer and studies in knockout mouse models showed that combined loss of NR4A1 and NR4A3 resulted in development of acute myeloid leukemia in mice [7]. In contrast, there is increasing evidence that NR4A1 is over-expressed in most solid tumors and is a negative prognostic factor for lung, colon and breast cancer patients [8–11]. Ongoing studies in breast, kidney, colon, pancreatic and lung cancer and rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) cells show that NR4A1 plays an important role in cancer cell growth, survival and migration/invasion through regulation of genes that drive these responses [12–14]. The role of NR4A2 in cancer and the effects of synthetic NR4A2 ligands is not well-defined, although most existing data suggest that like NR4A1, NR4A2 is also pro-oncogenic in most cancer cell lines [15–26]. Moreover, in many of these tumors, NR4A2 is a negative prognostic factor for patient survival, and the overall functional profiles of NR4A2 and NR4A1 in the various types of cancer are similar including their inactivation of p53 [27–29].

NR4A2 has been extensively characterized in subcellular regions in the brain, and NR4A2−/− mice do not generate mid-brain dopaminergic neurons and die soon after birth [30–32]. Several laboratories have been investigating the role of NR4A2 in Parkinson’s disease [32–37] and in the loss of dopamine phenotype in mid-brain neurons of cocaine users [38]. Studies by Tjalkens and coworker [39–43] have demonstrated that the NR4A2 agonist 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-chlorophenyl) methane [DIM-C-pPhCl, CDIM12] crosses the blood-brain barrier and accumulates in the brain, and in vivo studies showed that DIM-C-pPhCl inhibited 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced loss of dopaminergic neurons and other markers of neurodegeneration [39,43].

The expression of NR4A receptors and the potential role of ligands for these receptors in glioblastomas and other neuronal tumors has not been investigated, although one study showed drug-induced expression of NR4A1 in a GBM cell line [44]. Therefore, we initially screened for NR4A expression in established GBM and 5 patient-derived GBM cell lines. Western blot analysis of cell lysates showed that 4 established cell lines expressed NR4A1, NR4A2 and NR4A3; in the patient-derived cells, there was variable expression of NR4A1 and NR4A3. In contrast NR4A2 was highly expressed in all patient-derived cell lines and thus serve as an ideal model for investigating the role of NR4A2 and the effects of NR4A2 ligands such as DIM-C-pPhCl in GBM. Our results demonstrate that NR4A2 is pro-oncogenic in glioblastoma and the NR4A2 ligands act as antagonists and thus represent a new class of chemotherapeutic agents for treating this deadly disease.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, Antibodies, and Reagents

1,1-Bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-chlorophenyl) methane [DIM-C-pPhCl (CDIM12)], 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(4-chloro-3-trifluoromethylphenyl) methane (3-CF3-4-Cl) and 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(4-bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl) methane (2-OH-4-Br) were synthesized in the laboratory of Dr. Stephen Safe, at Texas A&M University (College Station, Texas). Patient-derived xenografts from human gliomas (PDGs) cell lines 17008, 15037, 14104s, 14015s and 15049 were generated from fresh tumor specimens collected from newly-diagnosed patients with no prior chemo- or radiotherapy treatment. The Wayne State University Institutional Review Board approved the procedure and written and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Established human malignant glioma cell lines U87-MG, A172, T98G, and CCF-STTG1 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). PDG cells were maintained in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium)/Hams F-12 50/50 mix supplemented with L-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1X MEM non-essential amino acids, and 10 μg/ml gentamycin (Gibco, Dublin, Ireland). U87-MG, A172, T98G, and CCF-STTG1 were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2, and the solvent (dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) used in the experiments was ≤0.2%. DMEM, DMEM F-12 50/50 mix, FBS, formaldehyde, and trypsin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (cPARP,cat#9541T), cleaved caspase-8 (cat#9496T), cleaved caspase-7 (cat#9491T), Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (cat#4412s) and Anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (cat#4408s) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA); NR4A1 (cat#ab109180) antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); NR4A2(cat# sc-991), Ki67 (sc-23900) and NR4A3 (cat# sc-133840) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz (Santacruz, CA), and β-actin (cat# A5316) antibody from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Chemiluminescence reagents (Immobilon Western) for western blot imaging were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Apoptotic, Necrotic, and Healthy Cells Quantification Kit was purchased from Biotium (Hayward, CA), Invasion chambers (cat#354480) was purchased from Corning Inc (Corning, NY), and XTT cell viability kit was obtained from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA). Lipofectamine 2000 was purchased Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Luciferase reagent was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Antisense oligonucleotides 3 and 4 that are specific for NR4A2 were purchased from AUM Biotech (Philadelphia, PA). The siRNA complexes used in the study that were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich are as follows: siGL2–5′: CGU ACG CGG AAU ACU UCG A, siNR4A2 (SASI_Hs02_00341055): 5’-CCGAUUUCUUAACUCCAGA [dT][dT]-3’, 5’-UCUGGAGUUAAGAAAUCGG [dT][dT]-3’ and siNR4A3(SASI_Hs01_00091655): 5’-GUGCGAACCUGCGAGGGCU [dT][dT]-3’, 5’-AGCCCUCGCAGGUUCGCAC [dT][dT]-3’. Sequences for the antisense oligonucleotides against NR4A2 (AsO #3 and AsO #4) and the non-specific control (Ctl) are: NR4A2 #3 5’-TGTAGTAAACCGACCCGGAGT-3’, NR4A2 #4 5’- AAGATGAGTTTACCCTCCACT-3’, Scramble control 5’-TGACCCTATGCTGTTCCTATA-3’.

Plasmid

The GAL4-Nurr1 (full length human NR4A2 DNA, amino acids 1–598) was constructed by inserting PCR-amplified each fragment into the BamHI/HindIII site of pM vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Similarly, the FLAG-tagged full-length Nurr1 (FLAG-Nurr1) was constructed by inserting PCR-amplified full-length Nurr1 fragment into the HindIII/BamHI site of p3XFLAG-CMV-10 expression vector (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously [43].

Transactivation and cell viability assay

Cells (8×104) per well were plated on 12-well plates in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 2.5% charcoal-stripped FBS and 0.22% sodium bicarbonate. After 24 hr growth, various amounts of DNA [i.e., UASx5-Luc (400 ng), GAL4-Nurr1 (40 ng) and β-gal (40 ng)] were cotransfected into each well by Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 5–6 hr of transfection, cells were treated with plating media (as above) containing either solvent (DMSO) or the indicated concentration of compounds for 24 hr. Cells were then lysed using a freeze–thaw protocol and 30 μL of cell extract was used for luciferase and β-gal assays. LumiCount (Packard, Meriden, CT) was used to quantify luciferase and β-gal activities. Luciferase activity values were normalized against corresponding β-gal activity values as well as protein concentrations determined by Lowry’s Method. Cells were treated for different time in 96-well plates and 25 μl of XTT solution was added to each well and incubated for 4 hr as outlined in the manufacturer’s instruction (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA). Absorbance was measured at wavelength of 450 nm in a 96 well plate reader after incubation for 4 hr in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Measurement of apoptosis (Annexin V staining)

Cancer cells were seeded at density of 1.5×105 per ml in 6 well plates and treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or compounds for 24 hr. Cells were then stained and analyzed by flow cytometry using the Dead cells apoptosis kit and Alexa Fluor 488 assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA).

Scratch and invasion assay

Cells (80% confluent) were maintained in six-well plates, a scratch was made using a sterile pipette tip and cell migration into the scratch was determined after 24 hr. The BD-Matrigel Invasion Chamber (24-transwell with 8 μm pore size polycarbonate membrane) was used in a modified Boyden chamber assay. The medium in the lower chamber contained the complete culture medium of GBM, which acts as a chemoattractant. PDG cells (5×104 cells/insert) in serum-free medium were plated into the upper chamber with or without various concentrations of compounds and incubated for 24 hr at 37°C, 5% CO2; the non-invading cells were removed from the upper surface of the membrane with a wet Q-tip/cotton swab. Formalin (10%) was used to fix the invading cells on the lower surface for 10 min followed by staining with hematoxylin and eosin Y solution (H&E). After washing and drying, the numbers of cells in five adjacent fields of view were counted.

Small interfering RNA interference assay

Cells (2×105 cells/well) were plated in six-well plates in the complete culture medium. After 24 hr, the cells were transfected with 100 nM of each siRNA duplex for 6 hr using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Anti-sense oligonucleotides targeting NR4A2 were used directly in to the 6 well plates to give a final concentration of 10μM. For siRNA mediated transfection, culture media was changed to the fresh medium containing 10% FBS whereas culture media was not changed for anti-sense oligonucleotides. Cells were transfected for 72 hours and then treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or different concentrations of the test compound.

Immunofluorescence and western blot analysis

15037, 14015s and U87-MG cells (1.0 × 105 per ml) were plated in complete culture media and treated with either DMSO or CDIM 12 for 24 hr or with siCt or siNR4A2 for 48 hours. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked and incubated overnight with Ki67 primary antibody. Cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with anti-mouse IgG Fab2 Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody for 2 hr at room temperature and analyzed using a Zeiss confocal fluorescence microscope. Whole cell lysates from treatment groups were analyzed by western blots essentially as described (8,9,14).

Three-dimensional (3D) tumor spheroid invasion assay

The cells were suspended in the complete medium (2×104 cells/ml). Spheroids were produced by seeding 200 μl of the cell suspension into a well of a 96-well round-bottomed ultra-low attachment culture plates. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator for 24 hr, 100 μl/well of growth medium from the spheroid plates was removed and 100 μl/well of Matrigel (Corning, #356234) was added on the bottom of each well. After incubation for 1 hr and compounds were added and then incubated for 3–5 days followed by fixation in 4% formaldehyde. Spheroid invasion was determined by measuring the cross-sectional areas of the spheroid center and the rim of invaded cells using Image J software.

Xenograft Study

Female athymic nu/nu mice (4–6 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Houston, TX). U87-MG cells (1×106 ) were harvested in 100 μl of DMEM and suspended in ice-cold Matrigel (1:1 ratio) and s.c. injected to either side of the flank area. After one-week mice were divided in to two group of 5 animals each. The first group received 100 μL of vehicle (corn oil), and second group of animals received an injection of 30 mg/kg/day of CDIM 12 in 100 μl volume of corn oil by i.p. for three weeks. All mice were weighed once a week over the course of treatment to monitor changes in body weight. After three weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed and tumor weights were determined. All animal studies were carried out according to the procedures approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s test were used to determine statistical significance between two groups. In order to confirm the reproducibility of the data, the experiments were performed at least three independent times and results were expressed as means ± SD. P-values less than 0.05, were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

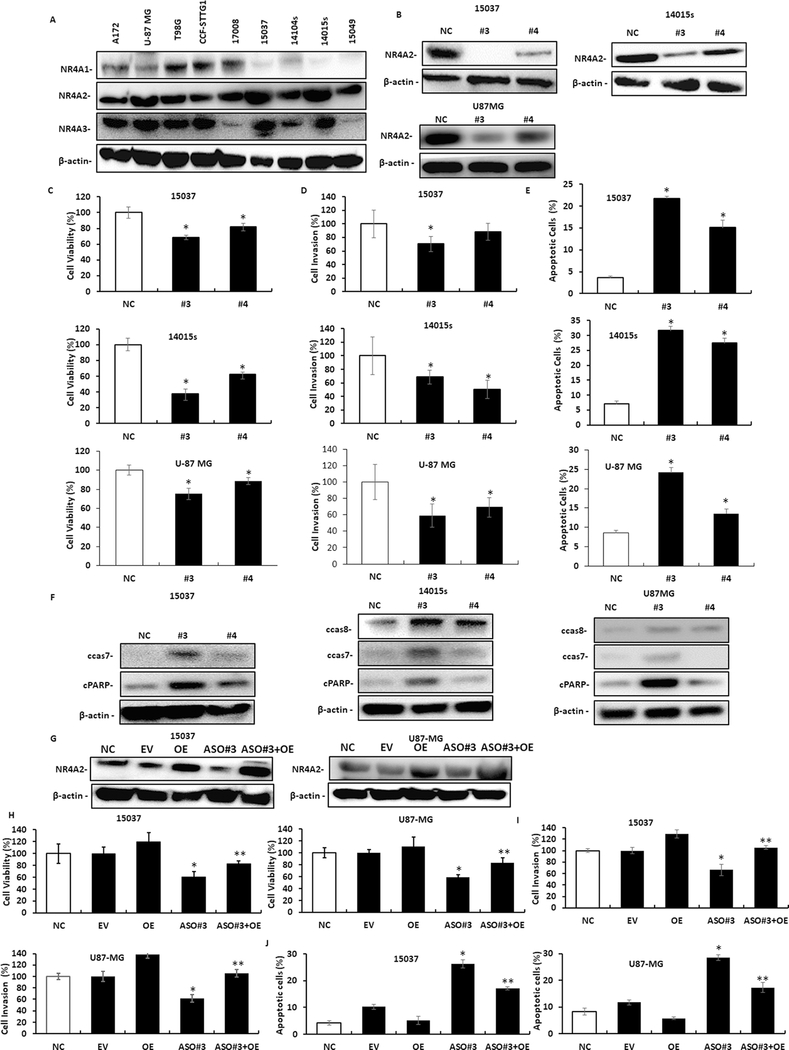

The expression of NR4A receptors in established glioblastoma cell lines (A172, U87-MG, U98G and CCF-STTG1) and patient-derived cells (17008, 15037, 14004s, 14015s and 15049) was determined by western blot analysis of whole cell lysates. NR4A2 was expressed in all cell lines and NR4A3 was expressed in most of the cell lines, whereas NR4A1 was detected primarily in the established cell lines and only in two of the patient-derived cell lines (Fig. 1A). Thus, the patient-derived cell lines are somewhat unique in their expression of NR4A2 in the absence of NR4A1. Initial studies showed that small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were less effective than antisense oligonucleotides (AsOs) for NR4A2 knockdown. In this study we have investigated the role of NR4A2 in U87-MG,15037 and 14015s cells by NR4A2 silencing using antisense oligonucleotides (#3 and #4) on cell proliferation, survival and invasion. Antisense oligonucleotides were effective in decreasing expression of NR4A2 in 15037, 14015s and U87-MG cells (Fig. 1B) and this was accompanied by decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 1C) and invasion using a Boyden chamber assay (Fig. 1D). Moreover, decreased expression of NR4A2 induced markers of apoptosis including induction of Annexin V staining (Fig. 1E) and cleavage of caspase 8, 7 and PARP (Fig. 1F) in 15037, 14015s and U87-MG cells (note: cleaved caspase 8 wasn’t detected in 15037 cells). We used 15037 and U87-MG cells as models and show that the effects of AsO#3 knockdown of NR4A2 on decreased cell proliferation and invasion, and induction of Annexin V can be rescued by overexpression of NR4A2 (OE) (Fig. 1G–1J). In addition, Supplemental Figures 1A and 1B summarizes the flow cytometry results for Annexin V staining and also microscopic images for the invasion assays illustrated in Figures 1E and 1D respectively.

Figure.1.

NR4A2 expression and functions in glioblastoma cells. A. NR4A receptor expression in established and patient-derived glioblastoma cell lines was determined by western blot analysis of whole cell lysates. Glioblastoma cells were transfected with antisense oligonucleotides targeting NR4A2 (#3 and #4) or a non-specific control (NC) and whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blots (B) and effects on cell proliferation (C) cell invasion (D) and Annexin V staining (E) were determined as outlined in the Materials and Methods. F. Cells were transfected with a non-specific control (NC) or oligonucleotides (#3 and #4) targeting NR4A2 and markers of apoptosis were determined by western blots of whole cell lysates. 15037 and U87-MG cells were transfected with empty vector, an NR4A2 expression plasmid (OE), AsO #3 and OE plus AsO #3 (combined) and effects on NR4A2 expression (G), cell viability (H), invasion (I) and apoptosis (J) (Annexin V staining) was determined as outlined in the Methods. Results (C-E, and H-J) are means ± SD for at least three determinations per treatment group and significant (P<0.05) effects [compared to control (NC, non-specific oligonucleotide)] are indicated (*). Caspase 8 cleavage was not observed in 15037 cells. In H, significant (p<0.05) reversal of the effects of NR4A2 knockdown is indicated (**).

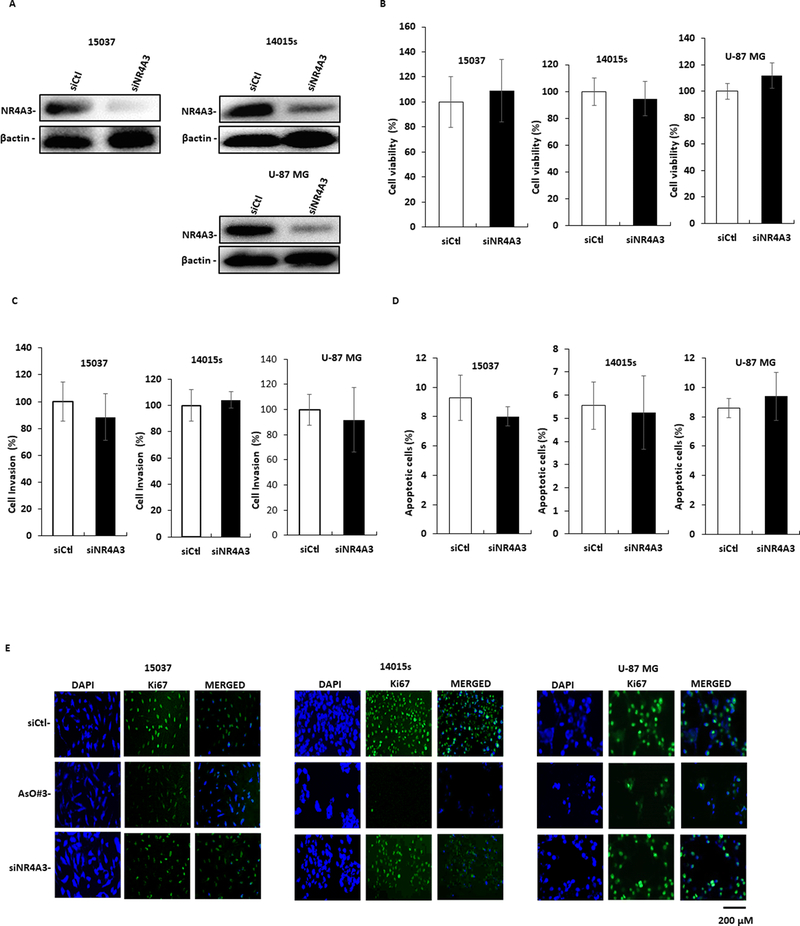

Since 15037, 14015s and U87-MG cells express NR4A3, we also investigated the effects of NR4A3 knockdown (Fig. 2A) by RNA interference (RNAi) on the phenotypic characteristics of the cell lines. Loss of NR4A3 had minimal effects on cell proliferation (Fig. 2B), invasion (Fig. 2C), or apoptosis (Fig. 2D); staining for the Ki67 proliferation marker (Fig. 2E) also demonstrated that the loss of NR4A3 had minimal effects on Ki67 staining. These results clearly demonstrate for the first time that NR4A2 is a pro-oncogenic factor in glioblastoma cells, whereas NR4A3 has minimal effects on their growth, survival and invasion. Supplemental Figures 1C and 1D summarizes the flow cytometry (Annexin V) and microscopic images (invasion) for the results in Figures 2C and 2D.

Figure.2.

Expression and functions of NR4A3. Cells were transfected with oligonucleotides targeting NR4A3 by RNA interference and effects on NR4A3 expression (determined by western blots of whole cell lysates), (A), cell proliferation (B), cell invasion (C) and Annexin V staining (D) were determined as outlined in Materials and Methods. E. Cells were transfected with antisense NR4A2 oligonucleotide (AsO #3) or siNR4A3 and Ki67 staining was determining as outlined in the Materials and Methods. Results (B-D) are expressed as means ±SD at least three determinations per-treatment group and significant (P<0.05) differences with control/untreated groups are indicated (*). siCtl is a non-specific RNA used as a control for NR4A3 knockdown studies.

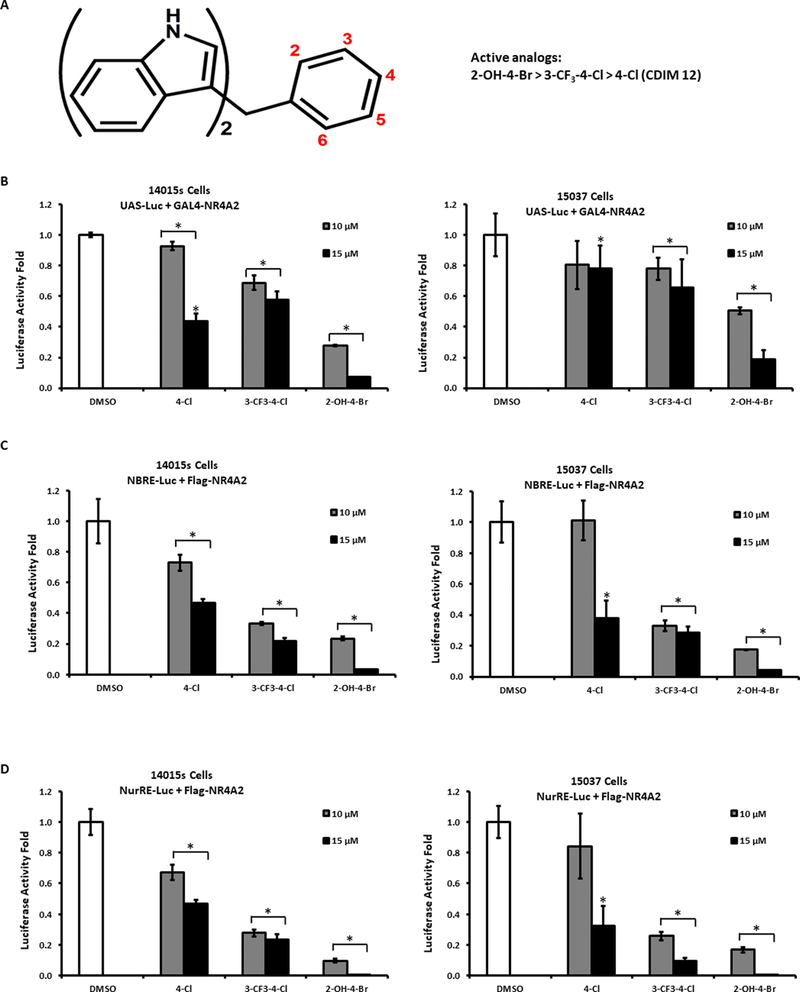

Previous studies identified a series of bis-indole-derived compounds (C-DIMs) that induce NR4A2-dependent transactivation in pancreatic cancer cells and 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-chlorophenyl)methane (DIM-C-pPhCl, 4-Cl) has been used as a prototypical NR4A2 ligand (Fig. 3A) [38–43]. Ongoing screening in pancreatic cancer cells identified 3 additional NR4A2 ligands, including 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(4-chloro-3-trifluoromethylphenyl)methane (3-CF3-4-Cl), 1,1-dimethyl-1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-hydroxyphenyl)methane (N-Me-4-OH), and 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(4-bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl)methane (2-OH-4-Br). These compounds induced NR4A2-dependent transactivation in Panc1 cells [43] (data not shown); however, in 14015s and 15037 glioblastoma cells transfected with a GAL4-NR4A2 chimera and a reporter plasmid containing GAL4 response elements (UAS5-luc), 10 and 15 μM 3-CF3-4-Cl and 2-OH-4-Br but not 4-Cl decreased transactivation (luciferase activity) (Fig. 3B). We also investigated ligand-dependent modulation of NR4A2-regulated gene expression using reported gene constructs containing an NGF1-B response element-luciferase construct (NBRE3-luc) (Fig. 3D) and a Nur-responsive element (NuRE3-luc) (Fig. 3C) which bind NR4A2 as a monomer and dimer, respectively. The 3 ligands also decreased NR4A2-dependent transactivation in these assays, suggesting that they act as NR4A2 inverse agonist/antagonist in glioblastoma cells.

Figure.3.

NR4A2 ligand dependent effects on transactivation. (A) Cells were treated with NR4A2 ligands. Cells were then transfected with UAS-Luc/GAL4-NR4A2 (B) NBRE-Luc/NR4A2 expression plasmid (40ng) (C) and NuRE-Luc/NR4A2 expression plasmid (40ng), (D) treated with bis-indole derived ligand and luciferase activity was determined as outlined in the Materials and Methods. Results are means ±SD for three replicate determinations for each treatment group and significant (P<0.05) effects (compared to DMSO control) are indicated (*).

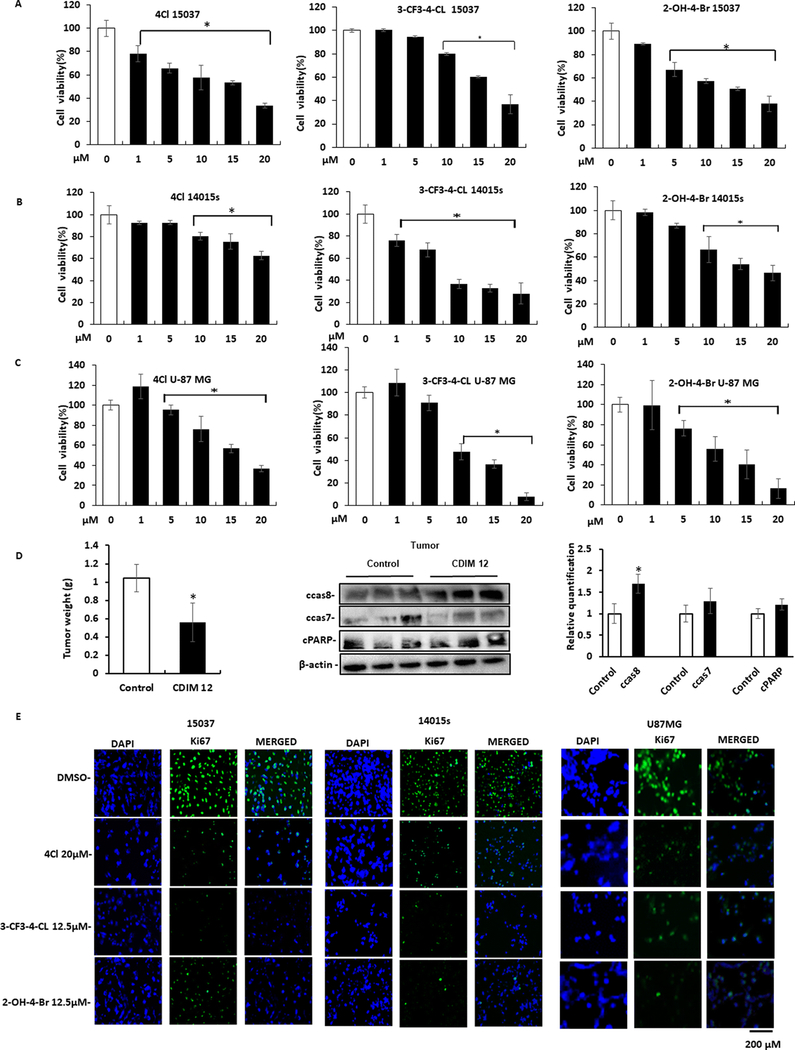

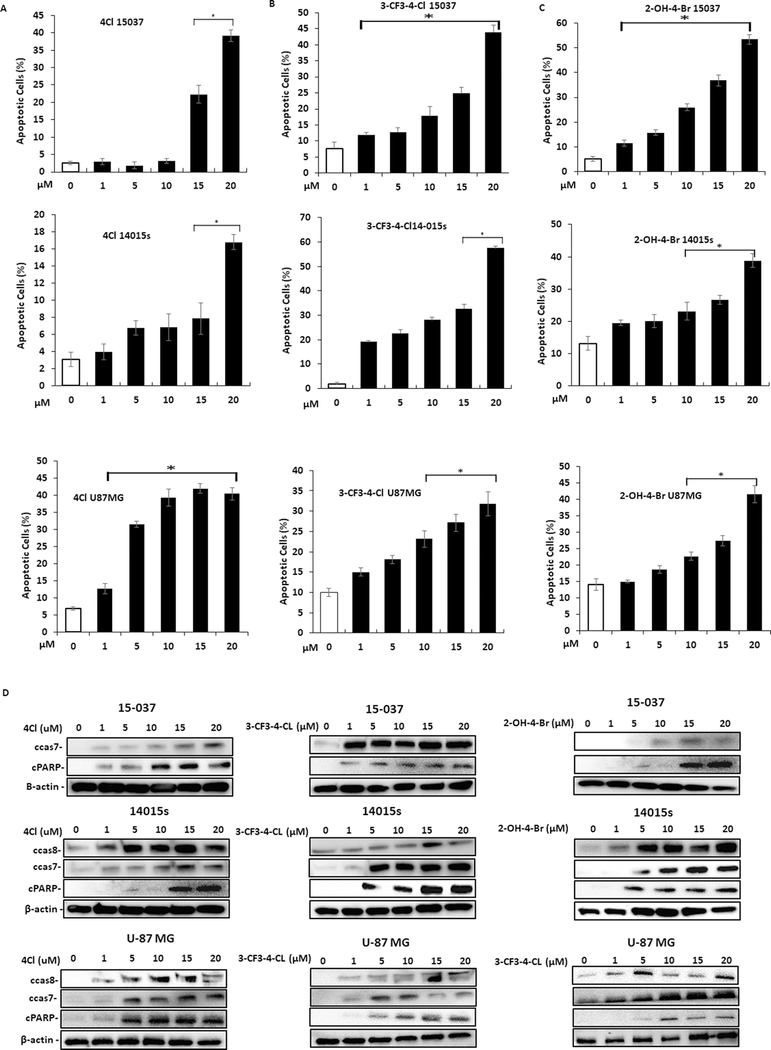

Treatment of 15037cells (Fig. 4A) with DIM-C-pPhCl (4Cl), 3-CF3-4-Cl, and 2-OH-4-Br respectively inhibited proliferation and treatment of 14015s (Fig. 4B) and U87-MG (Fig. 4C) cells with same set of compounds also inhibited cell proliferation. We also observed that 4-Cl (30 mg/kg/day) significantly decreased tumor weight in athymic nude mice bearing U87-MG tumor cells as a xenograft (Fig. 4D), and this was accompanied by significant upregulation of cleaved caspase 8 but not cleaved caspase 7 and cPARP in tumors from 4-Cl treated mice compared with vehicle controls. Treatment with 4-Cl for 24 hours decreased Ki67 (proliferation marker) in 15037, 14015s and U87-MG (Fig. 4E) cells. Thus, the NR4A2 ligands and NR4A2 knockdown (Fig. 1) were growth inhibitory, indicating that the C-DIMs are NR4A2 antagonists and this is consistent with their antagonist activities in the transactivation assays (Fig. 3); Treatment of glioblastoma cells with 4-Cl (Fig. 5A), 3-CF3-4-Cl (Fig. 5B) and 2-OH-4-Br (Fig.5C) induced Annexin V staining and cleaved caspase 7, 8 and PARP cleavage (Fig. 5D). These results were comparable to those observed after knockdown of NR4A2 (Fig. 1E and 1F) and the flow cytometry results for Annexin V staining are summarized in Supplemental Figures 2 and 3A.

Figure.4.

NR4A2 antagonist-induced responses. Treatment of 15037 cells (A), 14015s (B) and U87-MG (C) with different concentration of DIM-C-pPhCl (4Cl), 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(4- chloro-3 trifluoromethylphenyl) methane (3-CF3– 4-Cl) and 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(4- bromo-2-hydroxyphenyl) methane (2-OH-4Br) and effects on glioblastoma cell proliferation were determined as outlined in the Materials and Methods. D. Athymic nude mice bearing U87-MG cells as xenografts were treated with 4Cl (30 mg/kg/day) and effects on tumor weights and expression of apoptosis markers in tumor from control (corn oil) and 4Cl-treated mice were determined by western blot analysis of tumor lysates. Relative levels of various proteins in control versus 4Cl-treated mice were determined (normalized to β-actin). E. Glioblastoma cells were treated with different NR4A2 antagonists and Ki-67 staining was determined as outlined in the Materials and Methods. Results (A-C) are expressed as means ±SD for at least three replicates for each treatment group and significant (P<0.05) difference from untreated controls are indicated (*).

Figure.5.

NR4A2 antagonists induce apoptosis in glioblastoma cells. Glioblastoma cells were treated with different concentrations of 4Cl (A), 3-CF3–4-Cl (B) and 2-OH-4-Br (C) and effects on induction of Annexin V were determined as outlined in the Materials and Methods. D. Glioblastoma cells were treated with different concentrations of NR4A2 antagonists and whole cell lysates were analyzed for markers of apoptosis by western blots. Results (A-C) were expressed as means ±SD for at least three determinations per treatment group and significant (P<0.05) responses compared to untreated controls are indicated (*).

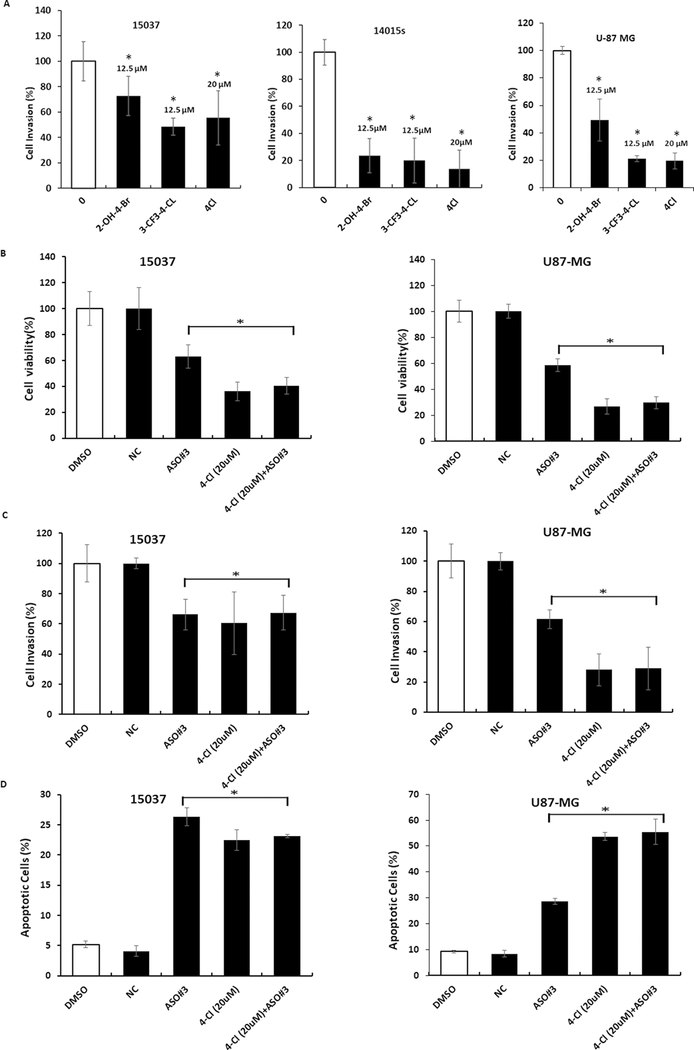

The potency of the various ligands in terms of growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis was ligand-, cell type-, and response-dependent with the most obvious difference in the fold induction of Annexin V in 15037 (high) vs. 14015s (low) cells, and this was due, in part, to the relatively higher expression of Annexin V in untreated 14015s cells. The NR4A2 antagonists also inhibited invasion of 15037 and 14015s cells in a Boyden chamber assay where the latter cell line appeared to be more sensitive, and 4Cl-mediated inhibition of cell invasion required higher concentrations compared to 3-CF3-4-Cl or 2-OH-4-Br (Fig. 6A). Thus, the NR4A2 ligands and NR4A2 knockdown by antisense oligonucleotides gave similar responses in terms of cell proliferation, invasion and apoptosis, and we further investigated effects of these treatments in combination using 15037 and U87-MG cells. Results illustrated in Figures 6B–6D show that 4-Cl and AsO #3 alone decrease growth, induce Annexin V staining and inhibit invasion and the magnitude of their effects is dependent on the response and cell context. However, the magnitude of the combined effects (4-Cl plus AsO #3) was not greater that individual treatment response (maximal) and this supports a prime role for NR4A2 in mediating the effects of 4-Cl and AsO #3 in glioblastoma cells. Supplemental Figure 4 illustrates the flow cytometry (Annexin V staining) and microscopic images (invasion assay) for the combination (Fig. 6C–6D) and overexpression (Fig. 1G) experiments.

Figure.6.

NR4A2 antagonists inhibit glioblastoma migration/invasion and combination treatment. Cells were treated with 12.5μM (3-CF3–4-Cl and 2-OH-4-Br) or 20 μM (CDIM 12) and effects of glioblastoma cell invasion (A) in Boyden Chamber assay were determined. 15037 and U87-MG cells were transfected with AsO #3, treated 20 μM 4-Cl or AsO #3 plus 4-Cl and effects on cell proliferation (B), invasion (C) and Annexin V staining (D) were determined as outlined in the Methods. All treatments were significantly (p<0.05) different from control cells, however, the combination treatment (4-Cl plus AsO #3) did not significantly enhance the response.

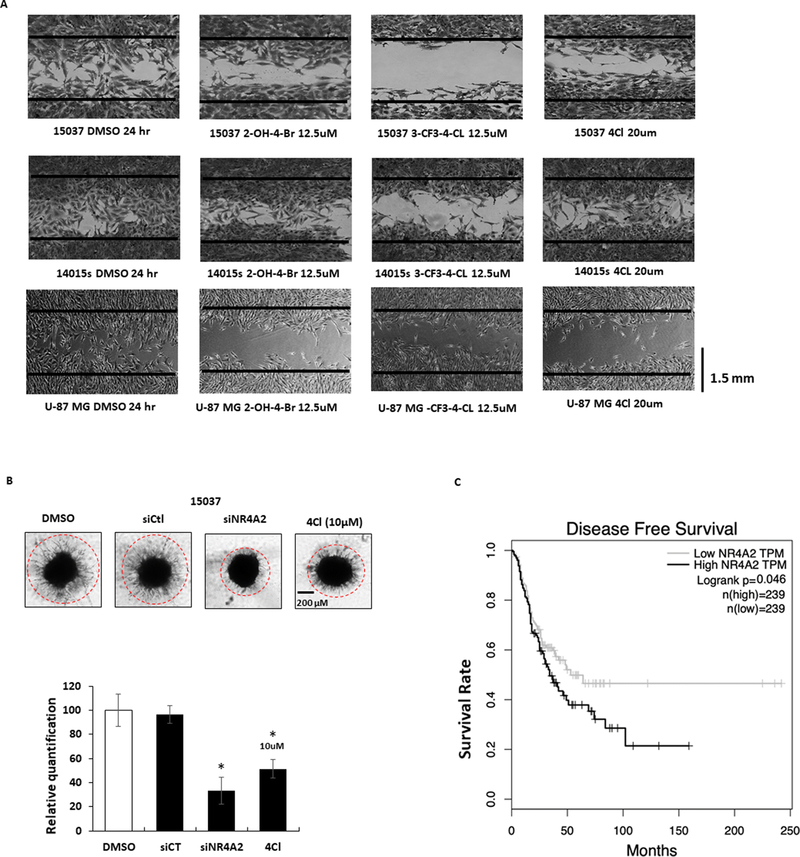

We also investigated the effects of NR4A2 ligands in scratch assays in 15037 and 14015s cells where 20 μM DIM-C-pPhCl only slightly inhibited migration whereas lower concentrations (12.5μM) of 2-OH-4-Br and 3-CF3-4-Cl inhibited migration with the latter compound being the most potent inhibitor (Fig.7A). Microscopic images illustrating the compound induced changes in invasion (Fig. 6A) are illustrated in Supplementary Figures S3B –S3D. We also observed that knockdown of NR4A2 or treatment with 10 μM 4Cl inhibited tumor spheroid invasion using 15037 cells compared to DMSO (solvent control) or cells transfected with a control oligonucleotide (siCt) (Fig.7B). We also examined the mRNA expression data available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) research network for high and low expression of NR4A2 in human GBM and LGG tumors by using Kaplan-Meier analysis; the differences in disease free survival in high expression of NR4A2 was significantly shorter than Low expression group [45,46] (Fig. 7C). These results demonstrate that NR4A2 is a growth promoting, survival and pro-invasion gene in glioblastoma, and C-DIM/NR4A2 ligands act as NR4A2 antagonists and represent a novel chemotherapeutic approach for treatment of this disease.

Figure.7.

NR4A2 ligands inhibit migration/invasion and prognostic significance of NR4A2 in globlastoma. A. Effects of NR4A2 ligands as inhibitors of migration were determined in a scratch assay as outlined in the Materials and Methods. B. Effects of NR4A2 ligands as inhibition of cell migration in a tumor spheroid invasion assay in 15037 cells were also determined as outlined in Materials and Methods (note 14015s and U87-MG cells did not exhibit invasion in this assay). C. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) research network for GBM and LGG database was used for expression of NR4A2 mRNA and correlated with patient’s disease-free survival by using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank tests.

Discussion

In 2018, it is estimated that 23,880 new cases of cancer of the brain and nervous system will be diagnosed and 16,380 deaths will occur from these diseases [47]. GBM is the most frequently diagnosed malignant brain tumor, and global incidence of this disease varies from 0.59–3.69 per 100,000 [48]. A diagnosis of GBM in an adult is devastating since patient survival times are in the range of 12–15 months and the 3-year survival of patients after diagnosis is in the 3–5% range. Primary de novo GBMs constitute approximately 90% of all cases and occur in elderly patients, whereas secondary GBMs are mainly diagnosed in younger patients [49].

Glioblastoma is a complex disease which involves multiple genetic alterations including mutations of several genes, resulting in a highly aggressive disease which is difficult to treat. The current standard-of-care for newly-diagnosed glioblastoma patients, include surgery, adjuvant radiotherapy and the drug temozolomide (TMZ; an alkylating agent), and these treatment regimens have had limited success [49,50]. The most troubling biological characteristics of high-grade glioma cells are their propensity and capacity to invade into the normal surrounding brain tissue, thereby evading the surgeon’s knife as well as the radiation delivered to the surgical resection margin. This reservoir of infiltrating tumor cells form a subpopulation of glioma stem cells that become a major source of tumor recurrence/progression, and they are typically resistant to chemoradiation, and are frequently the cause of eventual patient mortality.

The orphan nuclear receptor NR4A2 plays an important role in neuronal function (30–37), and our previous studies show that 4Cl and some related C-DIM compounds cross the blood-brain barrier and inhibit NR4A2-dependent inflammatory responses in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease [38–42]. Results of initial studies in established and patient-derived glioblastoma cell lines demonstrate expression of NR4A1, NR4A2 and NR4A3 in these cells and the patient-derived cells primarily expressed NR4A2/NR4A3 with relatively low levels of NR4A1 (Fig.1A). The differential expression of these orphan receptor in patient-derived cells afforded us the opportunity to investigate the function of NR4A2 and the potential for targeting this receptor as a novel approach for treating GBM patients.

We initially used a gene knockdown approach for determining the functions of NR4A2 in patient-derived 14015s, 15037 and U87-MG glioblastoma cells. The results indicated that loss of NR4A2 resulted in inhibition of growth, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of invasion. The effects of NR4A2 knockdown were in contrast to results obtained after knockdown of NR4A3 which had minimal effects on cell growth, survival and migration (Fig.2). Thus, NR4A2 clearly exhibits pro-oncogenic activity and is a negative prognostic factor in GBM (Fig. 7C) and these results were consistent with previous reports on the pro-oncogenic activities of NR4A2 in other cancer cell lines (15–26).

Previous studies have characterized 4Cl as an NR4A2 ligand that is effective as an anti-inflammatory drug for treating some NR4A2-regulated pathways in models of Parkinson’s disease and this is due, in part, to neuronal uptake of this compound [38–42]. In transactivation studies in pancreatic cancer cells, 4Cl activated NR4A2-dependent transactivation [43], whereas 4Cl and two additional C-DIM analogs inhibited NR4A2-dependent transactivation in glioblastoma cells (Fig. 3) and this was consistent with their inhibition of NR4A2-regulated pro-oncogenic-like activities. Thus, in terms of NR4A2-dependent transactivation, 4Cl and related compounds are selective receptor modulators that exhibit cell type-specific agonist (pancreatic cancer) and antagonist (GBM) activities, and this has previously been observed for C-DIMs that interact with NR4A1 [12,13].

These results confirm the pro-oncogenic activity of NR4A2 in glioblastoma cells and show that NR4A2 ligands such as the C-DIMs that act as antagonists represent a novel approach for treating GBM. Current studies are focused on investigating and identifying NR4A2-regulated genes/pathways in glioblastoma and also developing more potent NR4A2 antagonists for future clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

NR4A2 is expressed in established and patient-derived glioblastoma cells

NR4A2 is a pro-oncogenic factor

NR4A2 antagonists block NR4A2-mediated oncogenesis

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [P30-ES023512 (SS), R01ES025713 (SS), R01-CA202697 (SS), and T32-ES026568 (KK)], Texas A&M AgriLife Research (SS), the Sid Kyle Chair Endowment (SS), and the Karmanos Cancer Institute (SM).

Cite Sources of Support (if applicable): This research received federal grant and University funding as indicated under funding.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wansa KD et al. (2002) The activation function-1 domain of Nur77/NR4A1 mediates trans-activation, cell specificity, and coactivator recruitment. The Journal of biological chemistry 277 (36):33001–33011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203572200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giguere V (1999) Orphan nuclear receptors: From gene to function. Endocr Rev 20 (5):689–725. doi:Doi 10.1210/Er.20.5.689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wansa KD et al. (2003) The AF-1 domain of the orphan nuclear receptor NOR-1 mediates trans-activation, coactivator recruitment, and activation by the purine anti-metabolite 6-mercaptopurine. The Journal of biological chemistry 278 (27):24776–24790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300088200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z et al. (2003) Structure and function of Nurr1 identifies a class of ligand-independent nuclear receptors. Nature 423 (6939):555–560. doi: 10.1038/nature01645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell MA, Muscat GE (2006) The NR4A subgroup: immediate early response genes with pleiotropic physiological roles. Nuclear receptor signaling 4:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearen MA, Muscat GE (2010) Minireview: Nuclear hormone receptor 4A signaling: implications for metabolic disease. Mol Endocrinol 24 (10):1891–1903. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullican SE et al. (2007) Abrogation of nuclear receptors Nr4a3 and Nr4a1 leads to development of acute myeloid leukemia. Nature medicine 13 (6):730–735. doi: 10.1038/nm1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SO et al. (2014) The orphan nuclear receptor NR4A1 (Nur77) regulates oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic cancer cells. Molecular cancer research : MCR 12 (4):527–538. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SO et al. (2012) The nuclear receptor TR3 regulates mTORC1 signaling in lung cancer cells expressing wild-type p53. Oncogene 31 (27):3265–3276. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu H et al. (2011) Regulation of Nur77 expression by beta-catenin and its mitogenic effect in colon cancer cells. The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 25 (1):192–205. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-166462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou F et al. (2014) Nuclear receptor NR4A1 promotes breast cancer invasion and metastasis by activating TGF-beta signalling. Nature communications 5:3388. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safe S et al. (2016) Nuclear receptor 4A (NR4A) family - orphans no more. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 157:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safe S et al. (2014) Minireview: role of orphan nuclear receptors in cancer and potential as drug targets. Mol Endocrinol 28 (2):157–172. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedrick E, Safe S (2017) Transforming Growth Factor beta/NR4A1-Inducible Breast Cancer Cell Migration and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Is p38alpha (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 14) Dependent. Mol Cell Biol 37 (18). doi: 10.1128/MCB.00306-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ke N et al. (2004) Nuclear hormone receptor NR4A2 is involved in cell transformation and apoptosis. Cancer research 64 (22):8208–8212. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun L et al. (2016) Notch Signaling Activation in Cervical Cancer Cells Induces Cell Growth Arrest with the Involvement of the Nuclear Receptor NR4A2. J Cancer 7 (11):1388–1395. doi: 10.7150/jca.15274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komiya T et al. (2010) Enhanced activity of the CREB co-activator Crtc1 in LKB1 null lung cancer. Oncogene 29 (11):1672–1680. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Tai HH (2009) Activation of thromboxane A(2) receptors induces orphan nuclear receptor Nurr1 expression and stimulates cell proliferation in human lung cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 30 (9):1606–1613. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J et al. (2013) Orphan nuclear receptor nurr1 as a potential novel marker for progression in human prostate cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 14 (3):2023–2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llopis S et al. (2013) Dichotomous roles for the orphan nuclear receptor NURR1 in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 13:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Y et al. (2013) Expression of orphan nuclear receptor NR4A2 in gastric cancer cells confers chemoresistance and predicts an unfavorable postoperative survival of gastric cancer patients with chemotherapy. Cancer 119 (19):3436–3445. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu B et al. (2017) Activated Notch signaling augments cell growth in hepatocellular carcinoma via up-regulating the nuclear receptor NR4A2. Oncotarget 8 (14):23289–23302. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inamoto T et al. (2008) 1,1-Bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-chlorophenyl)methane activates the orphan nuclear receptor Nurr1 and inhibits bladder cancer growth. Molecular cancer therapeutics 7 (12):3825–3833. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han Y et al. (2013) Nuclear orphan receptor NR4A2 confers chemoresistance and predicts unfavorable prognosis of colorectal carcinoma patients who received postoperative chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer 49 (16):3420–3430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han YF, Cao GW (2012) Role of nuclear receptor NR4A2 in gastrointestinal inflammation and cancers. World J Gastroenterol 18 (47):6865–6873. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.6865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beard JA et al. (2015) The interplay of NR4A receptors and the oncogene-tumor suppressor networks in cancer. Cell Signal 27 (2):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao BX et al. (2006) p53 mediates the negative regulation of MDM2 by orphan receptor TR3. The EMBO journal 25 (24):5703–5715. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang T et al. (2009) NGFI-B nuclear orphan receptor Nurr1 interacts with p53 and suppresses its transcriptional activity. Molecular cancer research : MCR 7 (8):1408–1415. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beard JA et al. (2016) The orphan nuclear receptor NR4A2 is part of a p53-microRNA-34 network. Sci Rep 6:25108. doi: 10.1038/srep25108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zetterstrom RH et al. (1996) Cellular expression of the immediate early transcription factors Nurr1 and NGFI-B suggests a gene regulatory role in several brain regions including the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 41 (1–2):111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zetterstrom RH et al. (1997) Dopamine neuron agenesis in Nurr1-deficient mice. Science 276 (5310):248–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saucedo-Cardenas O et al. (1998) Nurr1 is essential for the induction of the dopaminergic phenotype and the survival of ventral mesencephalic late dopaminergic precursor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 (7):4013–4018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadkhodaei B et al. (2009) Nurr1 is required for maintenance of maturing and adult midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 29 (50):15923–15932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3910-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kadkhodaei B et al. (2013) Transcription factor Nurr1 maintains fiber integrity and nuclear-encoded mitochondrial gene expression in dopamine neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (6):2360–2365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221077110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decressac M et al. (2012) alpha-Synuclein-induced down-regulation of Nurr1 disrupts GDNF signaling in nigral dopamine neurons. Sci Transl Med 4 (163):163ra156. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Decressac M et al. (2013) NURR1 in Parkinson disease--from pathogenesis to therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Neurol 9 (11):629–636. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volakakis N et al. (2015) Nurr1 and Retinoid X Receptor Ligands Stimulate Ret Signaling in Dopamine Neurons and Can Alleviate alpha-Synuclein Disrupted Gene Expression. J Neurosci 35 (42):14370–14385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1155-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Miranda BR et al. (2013) Neuroprotective efficacy and pharmacokinetic behavior of novel anti-inflammatory para-phenyl substituted diindolylmethanes in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 345 (1):125–138. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Miranda BR et al. (2015) Novel para-phenyl substituted diindolylmethanes protect against MPTP neurotoxicity and suppress glial activation in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Toxicol Sci 143 (2):360–373. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Miranda BR et al. (2015) The Nurr1 activator 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-chlorophenyl)methane blocks inflammatory gene expression in BV-2 microglial cells by inhibiting nuclear factor kB. Mol Pharmacol 87 (6):1021–1034. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.095398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammond SL et al. (2015) A novel synthetic activator of Nurr1 induces dopaminergic gene expression and protects against 6-hydroxydopamine neurotoxicity in vitro. Neurosci Lett 607:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammond SL et al. (2018) The Nurr1 ligand,1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(p-chlorophenyl)methane, modulates glial reactivity and is neuroprotective in MPTP-induced parkinsonism. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.246389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X et al. (2012) Structure-dependent activation of NR4A2 (Nurr1) by 1,1-bis(3’-indolyl)-1-(aromatic)methane analogs in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochemical pharmacology 83 (10):1445–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang LF et al. (2011) Overexpression of the orphan receptor Nur77 and its translocation induced by PCH4 may inhibit malignant glioma cell growth and induce cell apoptosis. J Surg Oncol 103 (5):442–450. doi: 10.1002/jso.21809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N et al. (2015) Comprehensive, Integrative Genomic Analysis of Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas. N Engl J Med 372 (26):2481–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brennan CW et al. (2013) The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155 (2):462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegel RL et al. (2018) Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 68 (1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ostrom QT et al. (2015) Epidemiology of gliomas In: Raizer J, Parsa A (eds) Current Understanding and Treatment of Gliomas. 1st edn. edn. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, pp 1–14 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearson JRD, Regad T (2017) Targeting cellular pathways in glioblastoma multiforme. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2:17040. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alexander BM, Cloughesy TF (2017) Adult Glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 35 (21):2402–2409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.