Abstract

Context: Persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) experience significant challenges when they access primary care and community services.

Design: A provincial summit was held to direct research, education, and innovation for primary and community care for SCI.

Setting: Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Participants: Key stakeholders (N = 95) including persons with SCI and caregivers, clinicians from primary care, rehabilitation, and specialized care, researchers, advocacy groups, and policy makers.

Methods: A one-day facilitated meeting that included guest speakers, panel discussions and small group discussions was held to generate potential solutions to current issues related to SCI care and to foster collaborative relationships to advance care for SCI. Perspectives on SCI management were shared by primary care, neurosurgery, rehabilitation, and members of the SCI community

Outcome Measures: Discussions were focused on five domains: knowledge translation and dissemination, application of best practices, communication, research, and patient service accessibility.

Results: Summit participants identified issues and prioritized solutions to improve primary and community care including the creation of a network of key stakeholders to enable knowledge creation and dissemination; an online repository of SCI resources, integrated health records, and a clinical network for SCI care; development and implementation of strategies to improve care transitions across sectors; implementation of effective care models and improved access to services; and utilization of empowerment frameworks to support self-management.

Conclusions: This summit identified priorities for further collaborative efforts to advance SCI primary and community care and will inform the development of a provincial SCI strategy aimed at improving the system of care for SCI.

Keywords: Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Primary care, Community care, Summit proceedings, Quality improvement

Introduction

Persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) are less likely to receive the same level of basic primary care services as able-bodied persons; yet they are at greater risk for adverse events, and earlier onset of chronic conditions and complications.1,2 Identified care gaps for persons with SCI have been identified related to preventive care (cancer screening, immunizations), bladder and bowel regulation, skin issues, sexual problems, and pain.1–4 Similarly, despite the high prevalence of depression, anxiety and substance abuse among persons with SCI, psychological disorders are often under-recognized and under-treated.5–7 Many health issues experienced by persons with SCI could be improved with access to quality primary care.8 Community care for persons with SCI, including home-based attendant and nursing care, is limited, which often contributes to preventable secondary complications (e.g. skin, bladder and bowel issues).9–11 Persons with SCI are high users of health care services, and often use emergency and/or hospital services for conditions that could be managed in the community.2,8,12 Optimal primary care for persons with SCI requires innovative solutions involving collaborative relationships among persons with SCI, care providers across sectors and services, researchers, policy makers, funders and other key stakeholders.

In Canada a number of organizations are aimed at supporting research and enhancing quality of life for persons with SCI, including The Centre for Family Medicine (CFFM) Mobility Clinic, an interprofessional clinic with the objective to enhance primary care for persons with SCI through research, knowledge translation, and development of strategies to improve access to quality SCI care,13–16 the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, a non-profit organization aimed at preventing neurotrauma and facilitating the application of neurotrauma-related research into clinical practice, the Rick Hansen Institute, a non-profit organization aimed at increasing SCI research and improving the quality of life and care for persons with SCI, and SCI Ontario, a community-based agency providing advocacy, peer support and service navigation support. With interest in developing a provincial strategy to improve primary care and community care for those with SCI these groups came together to convene a one-day Primary Care and Community Care SCI Summit of key SCI stakeholders. This summit provided an opportunity to bring key partners together to foster relationships and strengthen collaborative efforts that will be paramount in developing a system of care that more adequately addresses the needs of persons with SCI.

This paper describes the summit proceedings, outcomes, and key themes identified at the summit and describes next steps toward the development of a provincial strategy for SCI care.

Methods

The summit was sponsored by and organized by working group members representing the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, the CFFM, Rick Hansen Institute, and SCI Ontario (Table 1). Working group members were responsible for planning the summit, articulating objectives and identifying summit panel members and participants. An agenda was developed by a professional facilitator to discuss current issues related to SCI care and potential solutions, taking into consideration the perspectives of experts in SCI care, consumers, and front-line health professionals, with an aim to:

Direct future research, education, and innovation in primary and community care for SCI consumers from the perspective of multiple stakeholders.

Shape the direction and implementation of health policy and SCI consumer care.

Further develop a community of practice and learning collaborative to advance primary and community care for SCI consumers.

Table 1. Primary care and community care summit working group members.

| Working group member | Affiliation | Professional role(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Peter Athanasopoulos | Spinal Cord Injury Ontario | Manager, Public Policy & Government Relations |

| Kent Bassett-Spiers | Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation | Chief Executive Officer |

| Lindsay Donaldson, BA | Centre for Family Medicine | Research and Evaluation Coordinator |

| Jennifer Howcroft | Centre for Family Medicine | Peer Research Assistant (Caregiver Consumer Representative) |

| Jeremy Howcroft | Centre for Family Medicine | Peer Research Assistant (SCI Consumer Representative) |

| Tara Jeji, MD | Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation | Program Director, Spinal Cord Injury |

| Phalgun Joshi, PhD | Rick Hansen Institute | Managing Director, Program Operations & Support |

| Joseph Lee, MD | Centre for Family Medicine | Family Physician, Chair |

| Upender Mehan, MD | Centre for Family Medicine | Family Physician |

| James Milligan, MD | Centre for Family Medicine | Family Physician, Director, Mobility Clinic |

| Vanessa Noonan, PhD | Rick Hansen Institute | Director of Research and Best Practice Implementation |

| Matt Smith, MB, MSc | Centre for Family Medicine | Research Assistant |

SCI, spinal cord injury.

The summit was held on November 23, 2016, in Toronto, Ontario.

Summit participants

In total, 95 individuals participated in the summit (Table 2). The number of SCI consumers is underestimated as some persons with SCI were attending the summit as representatives of other groups (N = 2) and were counted as such. Participants were identified by working group members who were familiar with the various key stakeholder groups in the SCI field; working group members extended personal invitations to participants. Participants were selected strategically to represent all relevant key stakeholder groups across different organizations, healthcare institutions, and geographic locations across the province. The majority were from across Ontario, with several out-of-province participants (Alberta, British Columbia).

Table 2. Summit participants (N = 95).

| Stakeholder group | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary care (family physicians, family medicine residents, nurse practitioners) | 24 (25.3) |

| Rehabilitation and specialized care (physiatrists, surgeons) | 7 (7.4) |

| Primary and community care allied health professionals (occupational therapists, chiropractor) | 3 (3.2) |

| Rehabilitation allied health professionals (Educators, nurses, occupational and physical therapists) | 8 (8.4) |

| Researchers (professors, research assistants, coordinators) | 13 (13.7) |

| Consumers (persons with SCI, family caregivers) | 7 (7.4) |

| Consumer advocacy groups (SCI Ontario, other organizations) | 15 (15.8) |

| Health service administrators/ managers | 2 (2.1) |

| Policy makers (Local Health Integration Networks)a | 6 (6.3) |

| Organizations serving the SCI and health care community (Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, Rick Hansen Institute, ICORD, Health Quality Ontario, eHealth Centre of Excellence, Association of Family Health Teams Ontario) | 10 (10.5) |

ICORD, International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries; SCI, spinal cord Injury.

aIn Ontario, Local Health Integration Networks are responsible for health care planning and provision of home care services.

Agenda and process

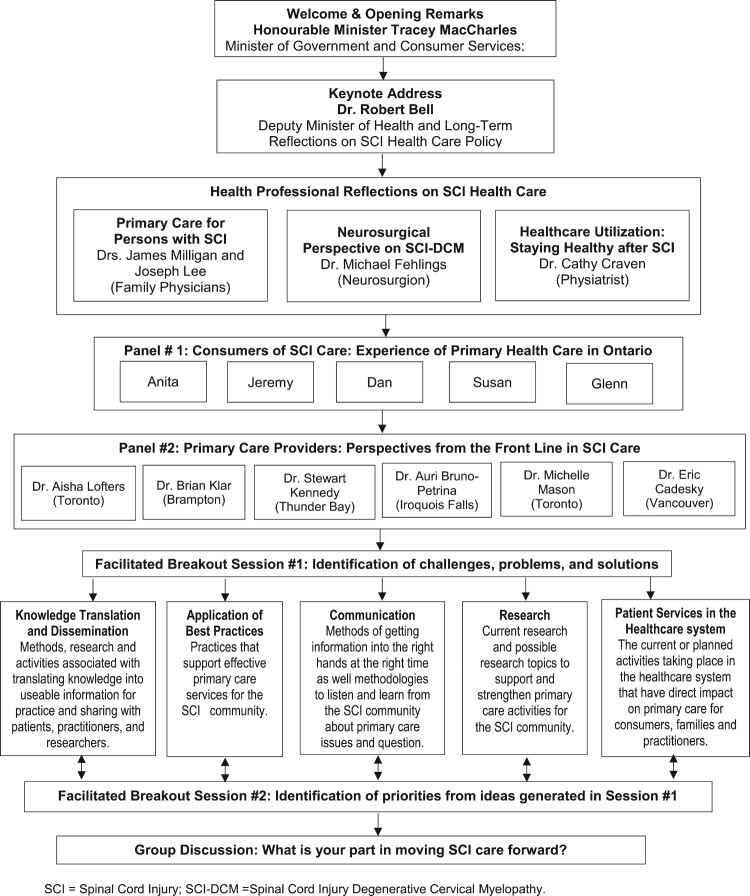

The morning agenda for the summit consisted of speakers setting the context and identifying strengths and key issues in primary care and community care (Figure 1). The afternoon agenda aimed to facilitate collaborative discussions towards solutions and directions forward. Breakout sessions were designed to generate a rich discussion on each of five domains: (1) knowledge translation and dissemination, (2) application of best practices, (3) communication among all stakeholders involved in SCI care, (4) research, and (5) patient services (accessibility and system issues). These domains were selected by the summit working group as being the most important areas of SCI care to address, as informed by the literature and a pre-work survey in which summit participants were asked to identify challenges associated with the care for SCI from their role perspective. These domains created a framework for participants to share what they knew from the literature, experience, and/or existing practices. The intent of the breakout discussions was to develop a preliminary list of issues and solutions related to each domain to subsequently inform the development of a strategy to improve the system of care for persons with SCI. Identified issues and solutions were rank ordered by priority (1 = top priority) to begin to identify priorities for moving forward.

Figure 1.

Meeting agenda and processes.

Participants were assigned to small groups (8 participants) to ensure representation from each key stakeholder group and to facilitate rich discussion. In the first breakout session, each group was assigned one of the five domains and were tasked with brainstorming answers to the question: “What are the emerging challenges for SCI and primary care for [specified domain]?” identifying at least 3–5 issues. A recorder and presenter was selected by each group to document and present on the discussion. After 30 min of discussion, each group was given an opportunity to review and synthesize the challenges they had identified, generating key themes as applicable. Following the identification of challenges, groups were then given 30 min to generate real, practical solutions for their identified issues, completing the following statement: “Given this challenge, we propose work should be done to … .[identified course of action].” Each group was then tasked with identifying the most important challenge and a priority solution as a call to action from the summit. Identified challenges and solutions were recorded on Post-It notes and each group posted their notes in a “Topic Bin” [a large sheet posted on a wall; one sheet per domain]; as each domain was covered by 2–3 table groups, the Topic Bin became the repository for all identified challenges and solutions.

A second facilitated breakout session was conducted with the full group of participants. Each small group reviewed with the larger group the top challenge and solution their group had identified. There was an opportunity for comments, questions, and discussion from the larger group. Following this group discussion, each small group was given an opportunity to reflect on and discuss further issues that arose in the larger group discussion on all five domains. Each small group was tasked with identifying the number one recommended solution for their specific domain, considering all of the challenges and solutions generated for that domain. In addition, participants were given an opportunity to review the Topic Bin for each domain and to identify their top priority solution. This provided participants an opportunity to provide input on priorities for all domains, not just the one their assigned to their small group. Following the summit, the facilitator prepared a report detailing the priorities that were documented for each domain. All presentations and discussions were audio and video-recorded.

Results

Consumer panel

A consumer panel of four individuals with SCI and a primary caregiver shared their experiences with accessing primary and community care. A number of common themes arose in this panel discussion; these themes are summarized with illustrative quotes in Table 3. Panel members spoke of the need for care that is client-centred and team-based, with an emphasis on supporting coordinated care and self-management. Community integration was described as challenged by restrictions on access to attendant services, which made access to health care, employment and social activities difficult. Rural areas were described as lacking specialists, resulting in reliance on family physicians who may lack expertise in SCI care to provide the majority of health care. Regional disparities exist in access to care and services, including caregiver respite and funding for specialized services and equipment, knowledgeable care providers, physical accessibility, and transportation services. These disparities can challenge and prevent health care access and contribute to or exacerbate existing health issues. Support from peers was identified as facilitating community reintegration and access to information about community services.

Table 3. Key themes generated from the consumer panel discussion.

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| Care for persons with SCI is fragmented, with minimal integration and coordination between care and service providers. | We need to look at building a system of service, trying to link hospital-based programs with community services so there is that continuum of care and people are followed and supported throughout their whole journey. [Consumer] |

| Accessing community-based care (home care services, attendant services) is extremely challenging | [Home care services] have restrictions in their hours of service, starting at 8am and going to I’m not sure when. But for someone who’s looking at integrating back into the community and trying to get back to work and trying to follow a 9-to-5 schedule it’s nearly impossible to be able to do that when you’re restricted to getting up at 8am in the morning. [Consumer] |

| There are geographic disparities in access to health and community services and funding for services and specialized equipment | We live two hours north of the city, so we are up in a very rural area, and I’m finding now that there are several challenges with living in a very small community north of the city. The services are extremely limited and we have very few services available to us for our daughter once she does come home … . Supportive housing in our area is almost non-existent. There is one facility which I understand, is in [smaller urban centre] but you’re looking at a 5- to 10-year wait list … .When comes to attendant care, services, OT, PT, the hours that are allocated to a patient in our area are very, very restrained. [Caregiver] |

| Many family physicians and other care providers are not familiar with health and management issues related to SCI | As a family, we do have a doctor in our area. But of course, our doctor, he has offered to continue to treat [daughter] when she returns home but he doesn’t have the specific training with spinal cord injury. He doesn’t have any of that expert or training that she’s definitely going to need. [Caregiver] |

| Physical barriers pose a challenge to accessing health care | I had to do some routine stuff, regular colonoscopy and things at the local hospital and I thought that would be really accessible but found out that yea, I can go into the change room that’s got an accessible door but I can’t get my wheelchair in there. And then I got into where I had to do an ultrasound and the room is not set up for transferring to a bed and so it had to be done in a chair. Another time we had a lift that they came in with but the bed was not conducive to having the lift slide underneath. So all these things you think the hospital care would have accessibility, but it’s not even close. [Consumer] |

| Lack of adequate transportation is major barrier to accessing health care | I could have just gone downtown, I could have gone to people I’ve accessed before at Lyndhurst, my specialist … because I was as sick as I was, I didn’t have the ability to travel on [Transportation services] or get there on my own. I didn’t have the money to take a $70 taxi both ways, $140 downtown to see my physiatrist, so I tried to stay local [within Greater Toronto Area] … . I didn’t think things were that much different. Boy was I surprised. [Consumer] |

| Peer and system navigation support is critical for community reintegration | It was very critical to know that there is so much that needs to be known about what’s available in the community. The resource there is, is not only the specialist but also the people that have injuries like yourself and you talk with them and they come across different things that no one has known about. The support in the community is critical. [Consumer] |

| There is limited respite for family caregivers | My dear wife has been my primary caregiver and that’s one of my big concerns too … . The bladder, which basically regulates our whole life, every 4–5 to 6 h, so she turns me in the middle of the night, has to get up and so I’m really concerned too about just the amount of care for the caregiver and that she has some breaks some time. We found that was not available in [Suburban region] … She’s been a real trooper … but I’ve got an exhausted caregiver. [Consumer] |

| Managing SCI is time and resource intensive, challenging community reintegration | Working with a spinal cord injury is really almost about having two full-time jobs. Your job and also taking care of your individual self and trying to stay at a level that is acceptable and navigable, in terms of being able to navigate for work. [Consumer] |

Family physician panel

A panel of six family physicians from urban and rural communities in Ontario and British Columbia shared their experiences with providing SCI care, and discussed strategies that enable them to optimize provision of care to persons with SCI. A number of common themes arose in this panel discussion (Table 4). Primary care providers (PCPs) were described as being well positioned to provide continuity of care and to be leaders in coordinating care across sectors and services, and can best do this within multidisciplinary teams with specialist collaboration and shared-care approaches. The low prevalence of SCI challenges physicians to remain updated on best practices. With minimal formal training in SCI, PCPs require other opportunities for capacity building such as mentoring opportunities, best practice guidelines for care, and better communication and coordination of care between specialists and PCPs. It was suggested that physical barriers to care may be overcome with greater access to virtual care, accessible by cell phone or computer via secured platforms; this would be particularly relevant in rural and remote areas. Provincial funding structures should ensure adequate remuneration (billing codes) to support physician use of technology-based services. Access to social supports and funding were described as important to enabling community care. PCP can be strong advocates to the government for optimal SCI care. Panel members noted the importance of physically accessible health care and acknowledged a lack of awareness of how significant a barrier to care this is. It was noted that current health information record systems are unable to accurately capture statistics and code services related to SCI; system improvements are needed to improve access to information that can inform practice change.

Table 4. Key themes generated from the primary care provider panel discussion, with illustrative quotes.

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| Primary care providers are well positioned to provide SCI care within shared care and team approaches | Continuity of care is so important, be it your primary care provider or your family health team, because it takes a team to take care of [persons with SCI]. A team that’s well coordinated, and we don’t have that in every aspect but when the patient does go into the hospital, it’s really good to have the family doctor as part of that team because he can actually help to guide that patient and the team of providers through the past 20 years of what this patient has been exposed since their SCI and all the individuals’ comorbidities. So I think that the team is very important and continuity of care is even more important, more critical. You need a team leader to provide that continuity of care and the family doctor is in the best position to be the team leader. |

| SCI is a complex condition to manage | That chart review really drove home for me was how complex our patients that we do provide care for are medically … Getting everybody that needs to be seen can be really challenging and the urgency that accompanies that with things like infections that need to be seen immediately or with skin issues that can turn in to pressure sores if you don’t get on top of them. |

| Primary care and home care providers receive minimal formal education in their training on SCI and require resource supports to optimally manage SCI |

While I received absolutely no

training in helping people with spinal cord injuries formally in my

education. The learning curve is vertical … Guidelines for care [are needed] to help with that steep learning curve if you don’t have 90 patients and if you do have 2 patients, having comprehensive guidelines would make all the difference and better system wide communication and coordination between specialists and their primary care providers. |

| Technology has an important role in supporting SCI care | Our closest centre, if we have a traumatic spinal cord injury and a need a neurosurgeon is 300 km away in Sudbury. We can’t change that. However, in our organization with today’s technology I really think we should improve accessibility to OTN or e-health … when you need to see a specialist instead of taking 31/2 years to see someone to solve osteomyelitis, is there someone we can connect with through OTN to help with this? This is my wish list. |

| Social and financial determinants of health are significant in SCI | I have a couple of patients that I’m thinking of. One had a good insurance and really had a lot of things covered and I had another patient that ended up having nothing. The economics, social determinants of health and all those factors, I think that plays a big role. |

| Physicians have an important role in advocacy | Think about the kind of care that you want to receive. Think about the kind of care you want to provide and advocate for the changes that will truly make that possible. |

| Greater reflection is needed on accessibility of medical offices | A few months ago we had a patient come to our site to talk to the health care team about her challenges. She talked about from the point of phoning the office to leaving the office … She talked about having to check in. At our particular site we have these large glass partitions with a small hole you can talk into, which have been there since days of SARS. I kind of have to tip toe to shout into the hole. She talked about having to shout so that everyone could hear her and mentioning all her personal information to communicate with the front desk. And then having to go back to the waiting room where there is no real room for a wheelchair … This was all really eye opening for us. |

| Information system inadequacies make it difficult to obtain objective information about SCI care | The biggest gap I found was that we don’t have a good search model to find all the SCI patients. So we need a more rigorous IT network to help us search for different types of patients. We look for cardiovascular, heart failure, we can look at certain MIs but we don’t have a good search model to look at SCI. |

Afternoon breakout sessions: identification of issues and solutions

Identified issues and solutions for each domain are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Summary of the issues and solutions identified for each domain as identified in the Summit meeting.

| Domain – issues | Solutions |

| 1. Knowledge Translation and Dissemination | |

|

|

| 2. Application of Best Practices | |

|

|

| 3. Communication | |

|

|

| 4. Research | |

|

|

Knowledge translation and dissemination

Summit participants identified a number of issues related to SCI knowledge translation and dissemination: challenges finding good information on SCI primary care; difficulties meeting learning requirements with existing knowledge sources; limited awareness and use of clinical guidelines; and low patient volume and competing interests. Solutions to these issues focused on building capacity for SCI care by (1) Creating an enabling network of SCI stakeholders; and (2) Reconceptualizing the management of SCI knowledge to accommodate for low patient volumes and competing priorities. It was recommended that a network of SCI stakeholders, including clinicians across sectors and services, and researchers, be created that would plan strategically and in a coordinated manner to create and share knowledge and work collaboratively to improve SCI primary care. This network would coordinate and utilize expertise from existing knowledge mobilization groups. Strategies to manage knowledge needs for low volume health conditions included elevating interest in SCI by leveraging similar conditions (multiple sclerosis, stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), having links to SCI best practice guidelines integrated into electronic medical records (EMR), creating incentives for participating in SCI CME, providing access to specialists for timely consultation via e-consultation platforms, empowering consumers to bring new knowledge to care providers, and exploring opportunities for collaboration with specialists for education in primary care.

Application of best practices

Issues related to the application of SCI best practices included: limited knowledge regarding SCI among care providers, lack of standardized best practices related to primary care, and limited awareness of and access to resources and guidelines. Solutions to these issues focused on building capacity for SCI care by: (1) Fostering primary care knowledge empowerment (providing clinicians with the knowledge to facilitate practice improvement); and (2) Creating an online repository of SCI resources. Summit participants suggested that knowledge empowerment could be fostered through mentorship opportunities between primary care and rehabilitation specialists, use of clinical ‘champions’, the development of Communities of Practice (CoP) including care providers across health sectors to develop evidence-informed guidelines, inform interprofessional best practices, and to develop mechanisms to make knowledge more accessible, including integrating resources and tools into EMRs. An online repository of an SCI resource repository for primary care related was proposed to share and promote new knowledge and tools among PCPs.

Communication

Related to communication, summit participants identified issues related to lack of patient advocacy and empowerment, lack of collaboration and integration between stakeholders, and lack of infrastructure to support communication and collaboration among care providers (remuneration, collaboration mechanisms). Solutions to these issues focused on improving SCI care by: (1) Creating integrated health records; (2) Using technology to access care providers; (3) Building a network of providers for SCI care; and (4) Advocating for equitable compensation to support care. Patient access to an integrated health record was suggested as an opportunity for patients to share health information between care providers who might otherwise not have access to this information and facilitate patients’ ability to advocate for needed care. Timely access to care for persons with SCI could be improved, particularly for those in rural areas, with the use of technological platforms such as e-consultation and Personal Computer Videoconferencing (PCVC). Building a provider network with system care pathways to guide patient flow between primary care, community care and specialist care could improve access to the right care at the right time. Advocacy efforts are needed to ensure adequate remuneration for communication between care providers and the provision of complex care.

Research

Summit participants identified issues related to conducting SCI research in primary care related to limited funding, limited attention to non-traumatic SCI, limited access to information, and inability to coordinate research. Proposed solutions to these issues focused on improving SCI research in primary care by: (1) Aligning research funding to care; (2) Promoting research on non-traumatic SCI as a priority; and (3) Improving the availability of data on SCI in primary care. Capacity for research in SCI could be expanded by advocating for funding to support knowledge creation related to key SCI care issues, particularly those contributing to high health service utilization such as urinary tract infections. Research on SCI care could be promoted by piloting a postgraduate fellowship in family medicine focused on research related to physical disabilities. Creating a value proposition to highlight the impact of research on SCI care (economic, system impacts) would serve to support advocacy efforts to secure more research funding, as would expanding the research efforts to include other conditions with similar characteristics. Increasing awareness among PCPs about the identification of non-traumatic SCI and promoting research collaborations with specialists would support efforts to conduct more research on this condition. Improving access to information on SCI in primary care for research purposes could be facilitated by improved coding of SCI in EMR software and other large databases.

Patient service accessibility and system issues

Issues identified related to service accessibility and system issues focused on: the lack of a clear model of primary care for SCI and care inequities across geographical regions.

Proposed solutions to these issues focused on improving care by: (1) Advocacy for effective models of care for SCI across the care continuum and improved access to community services; (2) Developing and implementing strategies to improve care transitions across sectors; and (3) Utilizing self-management and patient empowerment frameworks. It was noted that transforming the system of care for persons with SCI will require all key stakeholder groups to lobby for more effective and efficient models of care across all health sectors. Process mapping of services within regions and sub-regions would serve to identify existing gaps in health care and services to support advocacy efforts. Further expansion of existing models of care that have demonstrated effectiveness, such as the CFFM Mobility Clinic model of care, should be explored. Improved transitions across health sectors require the development of strategies to ensure coordinated and continued access to health care and services such as designated SCI system navigator roles, improved information sharing and communication between all care providers, and use of technology to expand virtual outreach and reduce geographic equities. Use of patient empowerment frameworks to support self-management was proposed as one strategy to improve access to care for persons with SCI.

Discussion

This paper describes the processes, findings and recommendations of a one-day provincial summit on primary and community care for individuals with SCI. Building on expert presentations and panel discussions, summit participants identified the existing care issues and possible solutions to improve and transform care for persons with SCI. Priority issues identified are consistent with those documented in the literature, particularly as related to the limited community services impacting community integration,17 limited clinician access to SCI guidelines and tools,13 limited use of technology to support communication between family physicians and specialists,18 limited care integration and coordination across sectors,19 and lack of infrastructure support for SCI care.20 Similarly, there is some evidence to support the implementation of proposed solutions such as the establishment of key stakeholder networks21 and CoPs22 to advance research and care, use of electronic platforms to improve collaboration and communication,23 development of clinical support tools integrated into EMR software,24 and use of patient empowerment frameworks to support self-management.25,26 These solutions are well aligned with the Patients First: Action Plan for Health Care – Ontario’s plan for changing and improving Ontario’s health system, emphasizing the role of patients at the centre of the system, focusing foremost on their needs.27

There are several limitations to the delivery of this Summit. The Summit focused on broad topics and issues related to health care service delivery for a person with SCI with limited attention paid to the social determinants of health (housing, employment, relationships).28 Similarly, limited attention was paid to the specific health conditions associated with SCI (e.g. mental health, bowel and bladder dysfunction, spasticity). As such, absent from the list of participants were care providers that specialize in the provision of care for specific conditions, such as mental health counsellors, psychologists, and psychiatrists who manage mental health issues in persons with SCI. Although there were representatives from other provinces in attendance, the Summit was focused on health care delivery in Ontario and outcomes may not be applicable to other jurisdictions.

As a follow-up to the summit, a call-to-action event was hosted by SCI Ontario on January 26, 2017; this in-person event (98 registrants) was accessible by live-stream webcast (174 registrants) and by videoconference from eight sites across the province (99 participants). This event served as an opportunity to review key issues and solutions discussed at the summit and to share with constituents plans for developing with a strategy for improving care for persons with SCI. Underscoring work towards the development of this strategy was the need to: continue to work with consumers to understand their needs, continue to work with partners to leverage opportunities, develop an action plan for presentation to the Ontario Government, and work with Local Health Integration Networks on the implementation of the Patients First Act29 as it relates to persons with SCI. This call-to-action event is just one example of efforts aimed at developing strategies to improve health care for persons with SCI. Other efforts have been undertaken to develop strategies to improve SCI knowledge translation,30 neuropathic pain management,31 and to develop SCI-related research priorities.32,33

As a result of the summit and subsequent call-to-action event, the following points were identified as key to understanding the care received by people with SCI: 1. Impacts of the current system of care for persons with SCI, namely the disparity in care between people with SCI and able-bodied peers resulting in a lower level of care for those with an SCI and increased likelihood of experiencing SCI-related complications (e.g. pressure injuries, bladder infections); and 2. Barriers to healthcare for persons with SCI, including insufficient information sharing between persons with SCI and their physicians, physical and environmental barriers preventing access to healthcare, attitudinal barriers preventing healthcare providers from caring for persons with SCI, and insufficient system-wide sharing of healthcare information sharing, resources and funding. Furthermore, three key goals emerged when considering the solutions developed for the five breakout session topics: 1. Increased accessible services for people with spinal cord injuries, regardless of home location, including access to family physicians, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and nurses; 2. Increased access to and expanded scope of care for attendant services in the community; and 3. Increased engagement of persons with SCI to ensure their continued involvement in improving SCI healthcare.

In March 2017, several summit working group members met with government representatives to share findings from the summit and call-to-action event and to further dialogue between key SCI stakeholder groups to advance research, care and innovation in primary and community care for persons with SCI. The CFFM Mobility Clinic continues to pursue efforts to improve primary care for persons with SCI, acting on solutions prioritized at the summit, such as the development of point-of-practice tools integrated into EMR,34 development of a repository for information, guidelines and tools specific to SCI primary care, development of case-based learning modules covering key issues related to SCI care including: preventative health, autonomic dysreflexia, neurogenic bowel and bladder, pain, pressure ulcers, sexual health and spasticity, expansion of Mobility Clinic care model to other sites, and the development of partnerships for ongoing research.

Conclusions

The Primary Care and Community Care SCI Summit brought together various key stakeholder groups to better understand the experiences of persons with SCI and the clinicians who care for them, to explore and develop quality improvement solutions for SCI care. This summit resulted in a common vision amongst varied stakeholders to improve health care for persons with SCI, strengthened partnerships, and fostered a commitment to consumer participation in the improvement of SCI health care.

Disclaimer statements

M. Smith and L. Donaldson are employees of the Centre for Family Medicine; P. Athanasopoulos is an employee of Spinal Cord Injury Ontario; K. Bassett-Spiers and Dr. T. Jeji are employees of the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; Dr. P. Joshi and Dr. V. Noonan are employees of the Rick Hansen Institute.

Funding This summit was supported by the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation (Grant #991) and the Centre for Family Medicine Family Health Team, Rick Hansen Institute, and Spinal Cord Injury Ontario.

Conflicts of interest The authors, J. Milligan, J. Lee, J. Howcroft, J. W. Howcroft and U. Mehan, declared no conflicts of interest.

ORCID

Jennifer W. Howcroft http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6055-9357

References

- 1.Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Siebens H.. Mobility impairments and use of screening and preventive services. Am J Public Health 2000;90(6):955–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.6.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McColl MA, Aiken A, McColl A, Sajaubara B, Smith K.. Primary care of people with spinal cord injury. Scoping review. Can Fam Physician 2012;58(11):1207–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Loo MA, Post MW, Bloemen JH, van Asbeck, FW.. Care needs of persons with long-term spinal cord injury living at home in the Netherlands. Spinal Cord 2010;48(5):423–28. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnelly C, McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass, C, O’Brien P, Savic G, et al. Utilization, access and satisfaction with primary care among people with spinal cord injuries: a comparison of three countries. Spinal Cord 2007;45(1):25–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB.. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Tate DG, Wilson CS, Temkin N, et al. Depression after spinal cord injury: comorbidities, mental health service use, and adequacy of treatment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92(3):352–59. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Õsteräker AL, Levi R.. Indicators of psychological distress in postacute spinal cord injured individuals. Spinal Cord 2005;43(4):223–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guilcher S, Craven BC, Calzavara A, McColl MA, Jaglal S.. Is the emergency department an appropriate subsitute for primary care for persons with traumatic spinal cord injury? Spinal Cord 2012;51(3):202–8. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaidyanathan S, Soni BM, Mansour P, Glass CA, Singh G, Bingley J, et al. Community-care waiting list for persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2001;39(11):584–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloemen-Vrencken JH, de Witte LP, Post MW.. Follow-up care for persons with spinal cord injury living in the community: a systematic review of interventions and their evaluation. Spinal Cord 2005;43(8):462–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guilcher SJ, Craven BC, Lemieux-Charles L, Casciaro T, McColl MA, Jaglal SB.. Secondary health conditions and spinal cord injury: an uphill battle in the journey of care. Disabil Rehabil 2013;35(11):894–906. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.721048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guilcher SJT, Munce SEP, Couris CM, FUng K, Craven BC, Verrier M, et al. Health care utilization in non-traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Spinal Cord 2010;48(11):45–50. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMillan C, Lee J, Milligan J, Hillier LM, Bauman C.. Physician perspectives on care of individuals with severe mobility impairments in primary care in Southwestern Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community 2016;24(4):463–72. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J, Milligan J, Hillier LM, McMillan C.. Evaluation of a primary care-based Mobility Clinic: improving health care for individuals with mobility impairments in Ontario, Canada. Int J Disabil Community Rehabil 2014;13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milligan J, Lee J.. Enhancing primary care for persons with spinal cord injury: more than improving physical accessibility. J Spinal Cord Med 2015(5):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Milligan J, Hillier LM, McMillan C.. Enhancing care for individuals with mobility impairments: Lessons learned in the implementation of a primary care-based Mobility Clinic. Healthc Q 2013;16(2):49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boschen KA, Tonack M, Gargaro J.. Long-term adjustment and community reintegration following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res 2003;26(3):127–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keely E, Liddy C, Afkham A.. Utilization, benefits, and impact of an e-consultation service across diverse specialties and primary care providers. Telemed J E Health 2013;19(10):733–38. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroll T, Neri MT.. Experiences with care co-ordination among people with cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2003;25(19):1106–14. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000152002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McColl MA. Structural determinants of access to health care for people with disabilities. In: McColl MA, Jongbloed L, (eds.) Disabilities and social policy in Canada. 2nd ed. Toronto, ON: Captus University Publications; 2006. p. 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McInnes E, Haines M, Dominello A, Kalucy D, Jammali-Blasi A, Middleton S, et al. What are the reasons for clinical network success? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:497. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1096-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lathlean J, leMay A.. Communities of practice: An opportunity for interagency working. J Clin Nurs 2002;11(3):394–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liddy C, Rowan MS, Afkham A, Maranger J, Kelly E.. Building access to specialist care through e-consultation. Open Med 2013;7(1):e1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fowler SA, Yaeger LH, Yu F, Doerhoff, D, Schoening P, Kelly B.. Electronic health record: integrating evidence-based information at the point of clinical decision making. J Med Libr Assoc 2014;102(1):52–55. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.102.1.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umar A, Mundy D.. Re-thinking models of patient empowerment. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015;209:175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aujoulat I, d'Hoore W, Deccache A.. Patient empowerment in theory and practice: polysemy or cacophony? Patient Educ Couns 2007;66(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care . 2015. Patient’s First Action Plan for Health Care. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/ms/ecfa/healthy_change/docs/rep_patientsfirst.pdf.

- 28.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74234-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legislative Assembly of Ontario . Bill 41, Patients First Act. 2016. Available from: http://www.ontla.on.ca/web/bills/bills_detail.do?locale=en&Intranet=&BillID=4215

- 30.Fehlings MG, Cheng CL, Chan E, Thorogood NP, Noonan V, Anh H, et al. Using evidence To inform practice and policy To enhance the quality of care for persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2017;34:2934–40. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loh E, Guy SD, Craven BC, Guilcher S, Hayes KC, Jeji T, et al. Advancing research and clinical care in the management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: Key findings from a Canadian summit. Can J Pain 2018;1:183–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bragge P, Piccenna L, Middleton J, Williams S, Creaseu G, Dunlop S, et al. Developing a spinal cord injury research strategy using a structured process of evidence review and stakeholder dialogue. part II: Background to a research strategy. Spinal Cord 2015;53:721–28. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hitzig SL, Hunter JP, Ballantyne EC, Katz J, Rapson L, Craven BC, et al. Outcomes and reflections on a consensus-building workshop for developing a spinal cord injury-related chronic pain research agenda. J Spinal Cord Med 2017;40:258–67. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2015.1136115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milligan J, Lee J, Hillier LM, Slonim K, Craven C.. Improving primary care for persons with spinal cord injury: development of a toolkit to guide care. J Spinal Cord Med 2018;May 7:1–10 [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]